Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that is the most common cause of dementia in the elderly, is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, as well as a progressive loss of synapses and neurons in the brain. The major pertinacious component of amyloid plaques is Aβ, a variably sized peptide derived from the integral membrane protein amyloid precursor protein (APP). The Aβ region of APP locates partly within its ecto- and trans-membrane domains. APP is cleaved by three proteases, designated as α-, β-, and γ-secretases. Processing by β- and γ-secretase cleaves the N- and C-terminal ends of the Aβ region, respectively, releasing Aβ, whereas α-secretase cleaves within the Aβ sequence, releasing soluble APPα (sAPPα). The γ-secretase cleaves at several adjacent sites to yield Aβ species containing 39–43 amino acid residues. Both α- and β-cleavage sites of human wild-type APP are located in APP672–699 region (ectodomain of β-C-terminal fragment, ED-β-CTF or ED-C99). Therefore, the amino acid residues within or near this region are definitely pivotal for human wild-type APP function and processing. Here, we report that one ED-C99-specific monoclonal antibody (mAbED-C99) blocks human wild-type APP endocytosis and shifts its processing from α- to β-cleavage, as evidenced by elevated accumulation of cell surface full-length APP and β-CTF together with reduced sAPPα and α-CTF levels. Moreover, mAbED-C99 enhances the interactions of APP with cholesterol. Consistently, intracerebroventricular injection of mAbED-C99 to human wild-type APP transgenic mice markedly increases membrane-associated β-CTF. All these findings suggest that APP672–699 region is critical for human wild-type APP processing and may provide new clues for the pathogenesis of sporadic AD.

Abnormal functioning and/or processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP), a type I membrane protein, has a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD).1, 2, 3 APP is cleaved by three proteases, designated as α-, β-, and γ-secretases (Supplementary Figure S1). The major fraction (>90%) of wild-type APP is proteolyzed by α-secretase that cleaves wild-type APP between residues APP687 and APP688 within the amyloid-β (Aβ) sequence, releasing soluble APPα (sAPPα) and α-C-terminal fragment (α-CTF, C83). Only a minority (<10%) of all wild-type APP molecules undergo β-cleavage at the β-cleavage site (between residues APP671 and APP672) generating sAPPβ and β-CTF (C99), the latter of which is subsequently processed by γ-secretase complex to generate a mixture of Aβ peptides primarily 40 or 42 residues in length (Aβ1-40/42).4, 5 The β-secretase cleaves APP in addition at a β′-site (between residues APP681 and APP682) to generate C89 that is further processed by γ-secretase to produce truncated Aβ11–40/42 species.6

Both α- and β-cleavage sites of wild-type APP are located in APP672–699 region (the ectodomain of β-CTF, ED-β-CTF, or ED-C99; Supplementary Figure S1). Therefore, the amino acid residues within or near this region are definitely pivotal for wild-type APP function and processing. Previous studies have identified that mutation in ED-C99 region can affect the physiological processing of APP and contribute to pathological features of familial AD (fAD). For example, Swedish APP carrying APP670/671 mutation (KM→NL) is cleaved by β-secretase over 50-fold more efficiently than wild-type APP.7 APP673 mutation (A→V) and APP693 mutation (E→G) can enhance Aβ production and accelerate formation of amyloid fibrils.8, 9, 10 APP682 mutation (E→K) blocks APP β′-site and shifts cleavage to β-site, thus increasing Aβ1–40/42 production.6 Although sporadic AD (sAD), the more common type of AD comprising 90 to 95% of all AD cases, lacks mutations in the APP gene, region-specific protein modifications within the ED-C99 region may affect wild-type APP processing similarly to APP gene mutations. For example, phosphorylation of ED-C99 at the threonine 687 (of APP770 isoform, or corresponding threonine 668 of APP751 isoform; Supplementary Figure S1) facilitates APP processing by γ-secretase.11 Therefore, the elucidation of potential influences of region-specific modifications, induced by either endogenous or exogenous molecules, on wild-type APP processing would be especially critical for clarifying the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of sAD.

To confirm this hypothesis, we used one mouse monoclonal antibody specifically recognizing ED-C99 (mAbED-C99) with its epitope at APP674–679 (Supplementary Figure S1). The influences of mAbED-C99 binding on human wild-type APP processing were evaluated in vitro using Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing human wild-type APP (CHO/APPwt cells) and cortical neurons derived from human wild-type APP transgenic (TgAPPwt) mice. The in vitro effects of ED-C99 binding with mAbED-C99 on wild-type APP processing were further evaluated and confirmed in vivo using TgAPPwt mice and 5 × FAD transgenic mice (Tg6799 line).

Results

Specific binding of mAbED-C99 inhibits α- but promotes β-cleavage of human wild-type APP

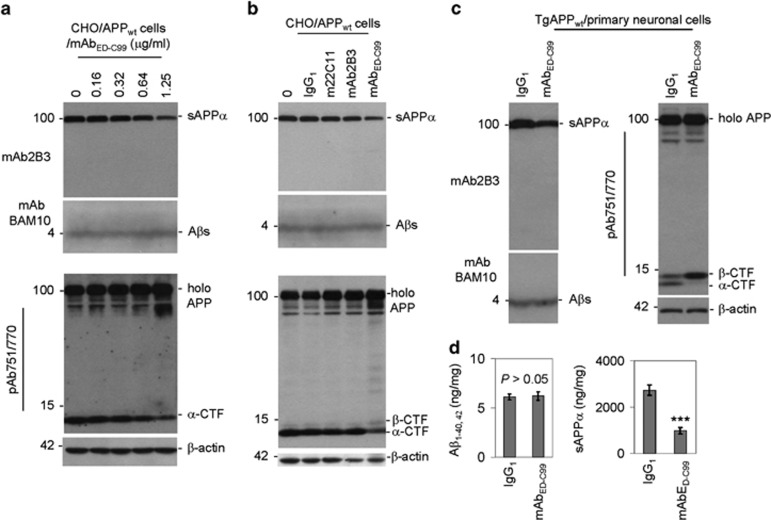

Western blotting (WB) analysis demonstrated that, compared with IgG1 isotype, 2 h treatment of CHO/APPwt cells with mAbED-C99 dose-dependently inhibits APP α-cleavage, as evidenced by the markedly decreased sAPPα and α-CTF levels (Figure 1a). In contrast, neither mAb22C11 (anti-APP66–81 antibody) nor mAb2B3 (sAPPα-specific antibody) inhibited the α-cleavage of APP (Figure 1b). Most notably, mAbED-C99 shifted APP processing from α- to β-cleavage, as indicated by decreased sAPP-α and α-CTF levels in combination with clearly elevated β-CTF level (Figure 1b). However, mAbED-C99 did not increase Aβ production, as assessed using mAbBAM10 (recognizes Aβ1–12; Figures 1a and b, middle panels).

Figure 1.

Treatment with mouse monoclonal-specific anti-ED-C99 antibody (mAbED-C99) markedly inhibits α-cleavage but promotes β-cleavage of human wild-type APP. (a) Human wild-type APP stably transfected CHO (CHO/APPwt) cells were plated in 24-well plates at 5 × 105/well and treated with mAbED-C99 at 0–1.25 μg/ml as indicated. (b) CHO/APPwt cells were treated with mAbED-C99, mAb22C11 (m22C11, recognizes APP66–81), or mAb2B3 (specifically and structurally recognizes sAPPα, but not full-length APP) antibodies, or isotype IgG1 control at 1.25 μg/ml. Immediately after 2 h treatment, cell supernatants were collected for western blotting (WB) analysis of sAPPα (using mAb2B3, upper panels) and Aβ secretion (using a monoclonal Aβ1–12 antibody BAM10, mAbBAM10, middle panels); cell lysates were prepared for WB analysis of APP processing products (using a polyclonal anti-C-terminal APP751/770 antibody, pAb751/770) and β-actin (internal control, lower panels). (c) Primary neuronal cells were cultured from cortical tissues of 1-day-old TgAPPwt mouse pups and seeded into 24-well-plates at 2 × 105/well for 18 h. These primary neuronal cells were treated with mAbED-C99 or IgG1 isotype control at 1.25 μg/ml for 2 h and then cell cultured media were collected for WB analysis of sAPPα (left upper panel) and secreted Aβ (left lower panel) levels as indicated; cell lysates were prepared for WB analysis of full-length APP (holo APP), APP-CTFs (right upper panel), and β-actin (right lower panel). These WB data are representative of four independent experiments with similar results. (d) In addition, the cell culture media were collected from the separated primary cortical neuronal cells following 8 h treatment with mAbED-C99 or IgG1 isotype control at 1.25 μg/ml for Aβ1-40/42 and sAPPα-ELISA. The results were presented as ng of Aβ40/42 or sAPPα per mg of total intracellular proteins (mean±S.D.; ***P<0.001). These ELISA data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results

Consistent with these findings in CHO/APPwt cells, 2 h treatment of primary cultured cortical neurons derived from TgAPPwt mice with mAbED-C99 dramatically inhibited α-cleavage but enhanced β-cleavage of APP, as indicated by decreased levels of sAPPα and α-CTF as well as markedly increased β-CTF generation, compared with IgG1-treated control cells (Figure 1c). In addition, sAPPα levels were also significantly decreased with mAbED-C99 treatment (Figure 1d, right panel). However, as seen with CHO/APPwt cells, mAbED-C99 did not significantly alter Aβ1–40/42 productions (Figure 1c, left lower panel) and their levels (Figure 1d, left panel). Altogether, these results indicate that specific binding of mAbED-C99 to the ectodomain of β-CTF (ED-C99) reduces α-secretase processing while increasing β-secretase processing of APP.

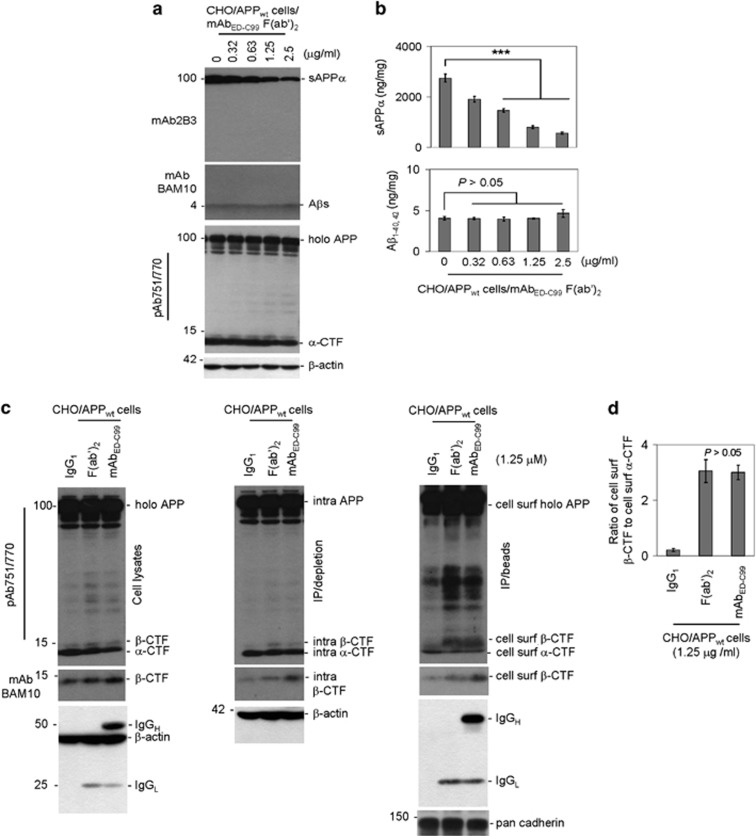

F(ab′)2 fragment of mAbED-C99 sufficiently inhibits α- but promotes β-cleavage of human wild-type APP

In living cells, the Fc fragment of antibody binds nonspecifically to cell surface Fc receptors. In order to determine whether nonspecific binding of mAbED-C99 to the cell surface Fc receptors is necessary to inhibit APP α-processing, we generated the F(ab′)2 fragment of mAbED-C99 that lacks the Fc fragment. Consistent with the results obtained with mAbED-C99, 2 h treatment of CHO/APPwt cells with mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment dose-dependently reduced sAPPα expression (Figure 2a, top panel) and its levels (Figure 2b, upper panel), while leaving secreted Aβ1–40/42 abundances (Figure 2a, middle panel) and their levels (Figure 2b, lower panel) unaltered at the doses examined. Treatment with mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment also slightly reduced secreted α-CTF levels (Figure 2a, lower panel), further supporting that specific binding of mAbED-C99 to the extracellular domain of β-CTF reduces α-cleavage of human wild-type APP. Moreover, mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment also dramatically enhanced cell surface β-CTF levels (Figure 2c, right panel) as well as WB band density ratio of cell surface β-CTF to cell surface α-CTF in CHO/APPwt cells (Figure 2d). The increased level of β-CTF is further confirmed using mAbBAM10 that is specific for β-CTF but not α-CTF (Figure 2c, middle panels).

Figure 2.

The mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment binding sufficiently enhances human wild-type APP β-cleavage. CHO/APPwt cells were treated with F(ab′)2 fragment of mAbED-C99 at 0–2.5 μg/ml. (a) Immediately following 2 h treatment, cell supernatants were collected for WB analysis of sAPPα (using mAb2B3, upper panel), Aβ secretion (using mAbBAM10, middle panel), and APP processing (using pAb751/770, lower panel). (b) The secreted sAPPα and Aβ40/42 levels were analyzed by ELISA and presented as ng of Aβ1–40/42 or sAPPα per mg of total intracellular proteins (mean±S.D.; ***P<0.001). (c) CHO/APPwt cells were treated with mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment, mAbED-C99, or isotype control IgG1 at 1.25 μg/ml for 2 h, washed three times with PBS containing CaCl2 and MgSO4 (PBS-CM), and then cell lysate portions of these cells were directly subjected to WB analysis using pAb751/770 or mAbBAM10 (left panels). The remaining cells were biotinylated with Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin dissolved in ice-cold borate buffer, quenched with NH4Cl-PBS-CM, and lysed. These cells lysates were then immunoprecipitated using Neutravidin beads. The intracellular (intra) proteins obtained by IP/Neutravidin depletion (middle panels) and the cell surface (cell surf) proteins obtained by IP/Neutravidin precipitation (right panels) were subjected to WB analysis using pAb751/770 and mAbBAM10. (d) For WB quantitative analysis, the band density ratio of cell surface β-CTF to cell surface α-CTF was analyzed and presented as mean±S.D. As indicated, there is no statistically significant difference between mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment and whole mAbED-C99 treatments (P>0.05). The data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results

Most importantly, the monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody clearly detected not only β-actin but also IgG1 heavy and light chains in the whole mAbED-C99-treated condition. In contrast, we only observed IgG1 light chain in the mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment-treated condition, confirming the purity of the prepared F(ab′)2 fragment. We did not observe IgG1 heavy and light chains in the IgG1-treated condition, suggesting that both mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment and whole mAbED-C99 can specifically bind to membrane-associated full-length human wild-type APP, whereas control IgG1 cannot (Figure 2c, lower panels).

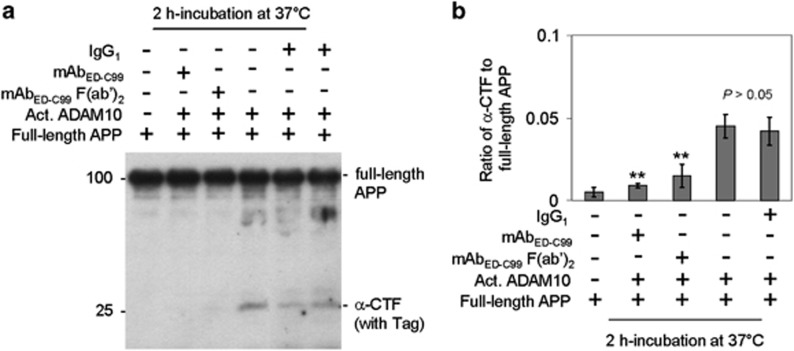

Specific binding of mAbED-C99 or its F(ab′)2 fragment directly inhibits ADAM10-mediated α-cleavage of human wild-type APP

We hypothesized that the decreased sAPPα and α-CTF levels elicited by mAbED-C99 or its F(ab′)2 fragment might be because of the direct inhibition of ADAM10-mediated α-cleavage of human wild-type APP. As expected, compared with IgG1-treated control, WB analysis showed that both whole mAbED-C99 and F(ab′)2 fragment significantly reduced WB band density ratio of α-CTF to full-length human wild-type APP, after incubation of full-length recombinant human wild-type APP protein with active ADAM10 in a cell-free system (Figure 3). These results clearly suggest that the binding of mAbED-C99 or its F(ab')2 fragment to ED-C99 blocks ADAM10 from proteolysing human wild-type APP at α-cleavage sites.

Figure 3.

The mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment and mAbED-C99 significantly block ADAM10-mediated α-cleavage of recombinant human wild-type APP protein. (a) Purified recombinant human wild-type full-length APP protein with Tags (C-terminal MYC/DDK; 260 ng) was incubated with IgG1 isotype control, mAbED-C99, or mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment (each at 1 μg) in the presence or absence of activated ADAM10 (Act. ADAM10; 1 unit) in a total volume of 50 μl justified with a buffer. Immediately following 1 h incubation at 37°C, the resulting incubation products were directly subjected to WB analysis using pAb751/770. (b) For WB quantitative analysis, band density ratio of α-CTF to full-length APP was analyzed and presented as mean±S.D. (**P<0.005). The WB result is representative of three independent experiments with similar results

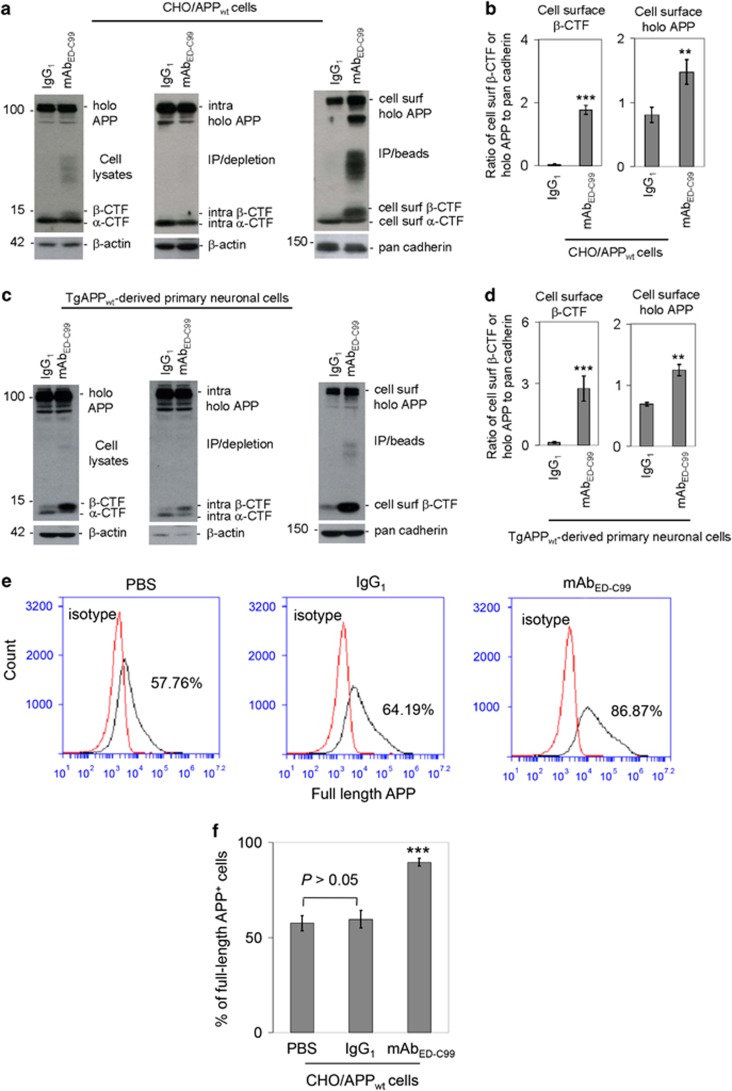

Specific binding of mAbED-C99 reduces APP endocytosis while increasing cell surface β-CTF

After reaching cell surface via secretory pathway, the matured human wild-type APP molecules could either be predominantly proteolyzed by α-secretases or rapidly endocytosed into the early endosomes through endocytosis pathway and then metabolized by β- and γ-secretases to generate Aβ.12, 13 As mABED-C99 did not alter levels of Aβ, we hypothesized that specific binding to ED-C99 may reduce APP endocytosis. In order to confirm whether mAbED-C99 binding to APP672–699 region could modulate human wild-type APP endocytosis, we further assessed the impacts of mAbED-C99 on full-length APP accumulations on the cell surface using the cell surface biotinylation technique.14 As compared with IgG1 isotype control, WB analysis of biotinylated proteins revealed that 2 h treatment of CHO/APPwt cells with mAbED-C99 markedly increased cell surface full-length APP level (Figure 4a, right panel) as well as significantly enhanced WB band density ratio of cell surface full-length APP to pan cadherin (Figure 4b, right panel). In parallel with these findings in CHO/APPwt cells, 2 h treatment of primary cultured cortical cells derived from TgAPPwt mice with mAbED-C99 also significantly increased cell surface full-length APP level (Figure 4c, right panel) as well as significantly increased WB band density ratio of cell surface full-length APP to pan cadherin (Figure 4d, right panel). The accumulation of cell surface APP was confirmed by flow cytometry that revealed that 2 h treatment of CHO/APPwt cells with mAbED-C99 led to a significant higher percentage of APP-positive cells when compared with IgG1 isotype control (Figures 4e and f). These results suggest that specific antibody binding to ED-C99 indeed reduces APP endocytosis. Interestingly, mAbED-C99 also dramatically enhanced cell surface β-CTF levels (Figures 4a and c, right panels) as well as significantly increased WB band density ratio of β-CTF to pan cadherin (Figures 4b and d, left panels) in both CHO/APPwt cells and primary cultured cortical cells derived from TgAPPwt mice. The markedly increased cell surface β-CTF level in both cell types following treatment with mAbED-C99 were further confirmed by mAbBAM10, an antibody specifically recognizing β-CTF but not α-CTF (Supplementary Figure S2). Taken together, these findings suggest that the specific bindings of mAbED-C99 to APP672–699 region inhibits human wild-type APP α-cleavage, while also blocking human wild-type APP endocytosis and promoting its β-cleavage and/or cell surface accumulation of β-CTF.

Figure 4.

Cell surface β-CTF and full-length APP are increased following treatment with mAbED-C99. (a) CHO/APPwt cells in 24-well plates (5 × 105/well) were treated with mAbED-C99 or IgG1 isotype control at 1.25 μg/ml for 2 h, washed three times with PBS-CM, and then cell lysate portions of these cells were directly subjected to WB analysis using pAb751/770 (left panels). The remaining cells were biotinylated with Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin, quenched with NH4Cl-PBS-CM, lysed, and immunoprecipitated (IP) using Neutravidin beads. The intracellular proteins obtained by IP/Neutravidin depletion (middle panels) and the cell surface (cell surf) proteins obtained by IP/Neutravidin precipitation (right panels) were subjected to WB analysis using pAb751/770. As shown below each panel, as an internal control, β-actin was analyzed for cell lysates and intracellular (intra) proteins and pan cadherin was analyzed for total cell surface proteins. (b) For WB quantitative analysis, band density ratios of cell surface β-CTF or full-length APP to pan cadherin were analyzed and presented as mean±S.D. (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001). The WB data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results. (c) Primary neuronal cells were cultured from cortical tissues of 1-day-old TgAPPwt mouse pups and replated in 24-well plate at 2 × 105/well overnight. These primary neuronal cells were treated with mAbED-C99 or IgG1 isotype control at 1.25 μg/ml for 2 h, washed three times with PBS-CM and then cell lysates were directly subjected to WB analysis using pAb751/770 (left panels). The remaining cells were biotinylated, immunoprecipitated with Neutravidin beads, and then subjected to isolation of intracellular and cell surface proteins. The intracellular proteins obtained by IP/Neutravidin depletion (middle panels) and the cell surface (cell surf) proteins obtained by IP/Neutravidin isolation (right panels) were subjected to WB analysis using pAb751/770. (d) For WB quantitative analysis, band density ratios of cell surface β-CTF or holo APP to pan cadherin were analyzed and presented as mean±S.D. (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001). These WB data are representative of two independent experiments with similar results. (e) Flow cytometry analysis of cell surface APP utilizing a rabbit anti-N-terminal APP antibody. (f) Percentage of full-length APP-positive cells are presented as mean±S.D. (***P<0.001)

Specific mAbED-C99 binding enhances the colocalization of human wild-type APP with cholesterol

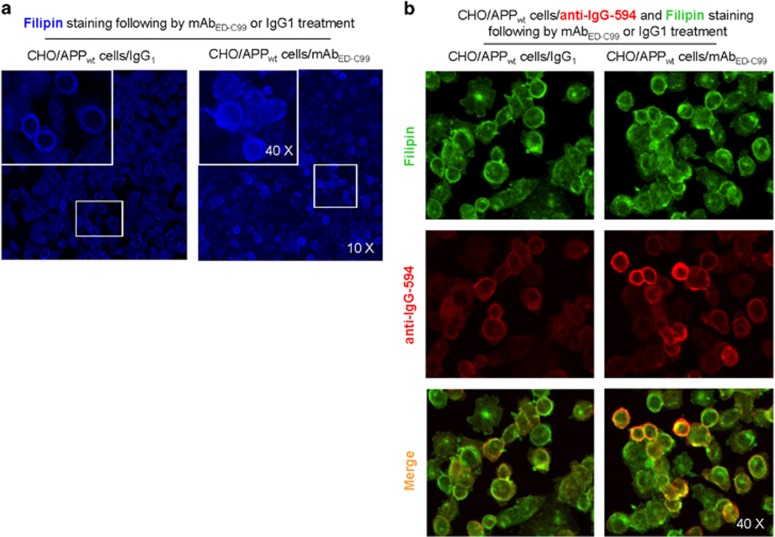

As growing evidence have suggested that cholesterol is of particular importance in regulating APP processing,15, 16, 17 favoring β-cleavage and amyloidogenic processing, we further determined colocalization of human wild-type APP with cholesterol in CHO/APPwt cells following 2 h mAbED-C99 treatment. Although 2 h treatment with mAbED-C99 increased the cholesterol level on both cellular and subcellular plasma membranes (as indicated by dispersed fillipin staining, Figure 5a), this enhanced human wild-type APP with cholesterol colocalization was primarily observed on cell surface but rarely in intracellular compartments (Supplementary Figure S3), indicating that the mAbED-C99-induced human wild-type APP with cholesterol colocalization is cell surface specific. In addition, merged image of cholesterol staining with fillipin (green) and rabbit anti-APP-C-terminal antibody labeling with anti-IgG-594 (red) revealed a higher colocalization of human wild-type APP with cholesterol in mAbED-C99-treated CHO/APPwt cells compared with IgG1 isotype-treated control cells (Figure 5b). This cell surface colocalization of APP with cholesterol may further reduce APP α-cleavage and favor β-cleavage and cell surface β-CTF accumulation.

Figure 5.

Colocalization of human wild-type APP with cholesterol in CHO/APPwt cells after mAbED-C99 treatment. (a) CHO/APPwt cells were plated to 8-well slide chamber and then, after overnight incubation, the cells were treated with mAbED-C99 or IgG1 isotype control for 2 h. These cells were stained by Filipin in strict accordance with the manufacturer's instructions of the cholesterol assay kit. (b) After Filipin staining and washing, some of these cells were permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 for 5 min, washed, and stained with rabbit anti-APP-C-terminal antibody overnight at 4°C. Alexa Fluor 594 Donkey anti-rabbit IgG was used to detect APP signals. Confocal images were taken by Olympus fluoview FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope (Tokyo, Japan)

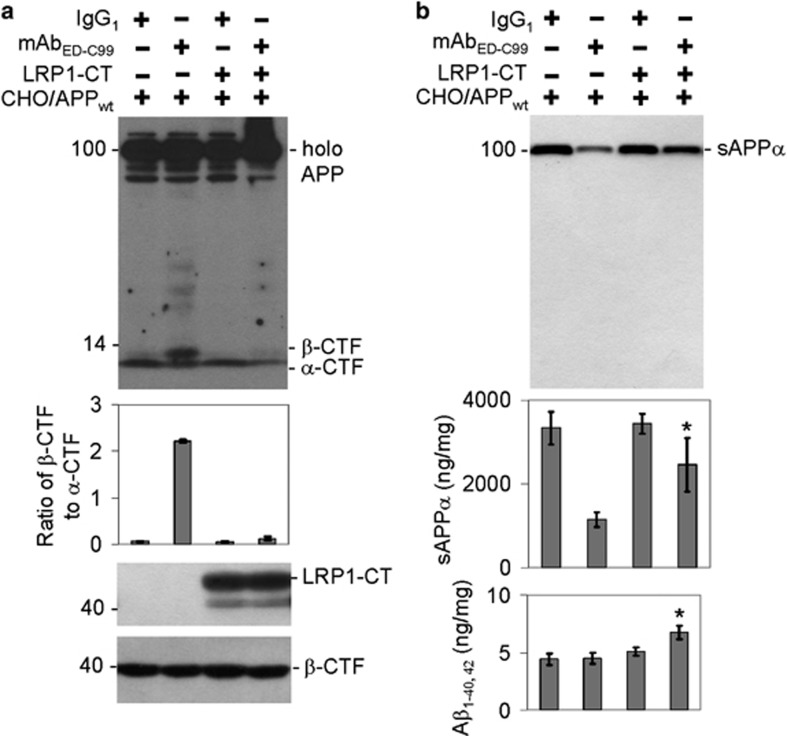

LRP1-CT overexpression reverses mAbED-C99-mediated cell surface accumulation of β-CTF

APP endocytosis is known to be mediated by binding to the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1). To further confirm that mAbED-C99 reduces APP endocytosis while enhancing cell membrane β-CTF accumulation, CHO/APPwt cells overexpressing the cytoplasmic tail of LRP1 (LRP1-CT) were exposed with mAbED-C99 for 2 h. Both WB and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analyses clearly suggested that although 2 h treatment of CHO/APPwt cells with mAbED-C99 promoted cell surface β-CTF accumulation as compared with IgG1 treatment (Figure 6a, upper panel, lanes 1 and 2), this change was dramatically reversed by overexpressed LRP1-CT (Figure 6a, upper panel, lanes 3 and 4). Surprisingly, LRP1-CT overexpression also significantly but partially reversed the mAbED-C99-mediated decrease of the secreted sAPPα abundances in the conditioned media (Figure 6b, upper panel, lanes 3 and 4) as well as its levels (Figure 6b, middle panel). Most interestingly, the secreted Aβ1–40/42 levels in the conditioned media were significantly elevated in CHO/APPwt/LRP1-CT cells following the reversed inhibition of APP endocytosis (Figure 6b, lower panel).

Figure 6.

Overexpressing LRP1-CT markedly restores human wild-type APP endocytosis in CHO/APPwt/LRP1-CT cells. CHO/APPwt/LRP1-CT or CHO/APPwt cells were treated with mAbED-C99 for 2 h. (a) Full-length APP and α/β-CTFs were examined by WB analysis. (b) The secreted sAPPα and Aβ1–40/42 levels in conditioned media were measured by WB analysis and ELISA. The band ratio of β-CTF to α-CTF and sAPPα ELISA results (ng of sAPPα per mg of total proteins) are presented as mean±S.D. These data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (*P<0.05)

mAbED-C99 promotes β-cleavage of human wild-type APP in vivo

Eight-month-old TgAPPwt female mice were treated with mAbED-C99 or isotype IgG1 as negative control via intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection. At 24 h after treatment, we found that WB band ratio of membrane-bound β-CTF to total APP in the mAbED-C99-treated group was significantly higher than that in the IgG1-treated control group (Figure 7a, middle panels, and Figure 7b, upper panel). Most interestingly, consistent with our in vitro data, mAbED-C99 did not alter the levels of Aβ species (Figure 7a, lower panels). Aβ ELISA analysis of brain homogenates also confirmed that Aβ1–40/42 species were not significantly changed in the mAbED-C99-treated group compared with IgG1 control group (Figure 7b, lower panel). In addition, 8-month-old 5 × FAD female transgenic mice (Tg6799 line) were treated with mAbED-C99 or isotype IgG1 as negative control via i.c.v. injection. At 24 h after treatment, we found that immunohistochemical staining also disclosed comparable amount of β-amyloid plaques in retrosplenial cortex (RSC), entorhinal cortex (EC), and hippocampus (H) regions of 5 × FAD transgenic mouse brains (Supplementary Figure S4).

Figure 7.

The mAbED-C99 promotes APP β-secretase processing in vivo. TgAPPwt female mice at 8 months of age were treated with mAbED-C99 or control IgG1 at 5 μg/mouse by intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection and killed 24 h after the treatment (n=6). (a) Cytosolic- (left panels) and membrane-associated proteins (right panels) prepared from mouse brain homogenates were subjected to WB analysis for APP processing. (b) For WB quantitative analysis, band density ratio of membrane-associated β-CTF to membrane-associated total APP was analyzed (upper panel). Aβ40/42 was also analyzed by ELISA (lower panel, n=6). The results are presented as pg of Aβ40/42 per mg of total intercellular proteins (mean±S.D.; ***P<0.001)

Discussion

Mutations in APP gene cause early onset of autosomal-dominant AD.3, 18, 19, 20 Relative to their wild-type homologs, the English (APP677 H→R) and Tottori (APP678 D→N) substitutions accelerate the kinetics of Aβ secondary structure change from statistical coil→α/β→β and produce oligomer size distributions skewed to higher order that are more toxic to cultured neuronal cells than wild-type oligomers.21 The Icelandic APP673 mutation (A→V) affects APP processing, resulting in enhanced Aβ production (quantity) and formation of amyloid fibrils in vitro (quality).8 In contrast, alternative APP673 mutation (A→T) results in an ∼40% reduction in the formation of amyloidogenic peptides and therefore protects against AD and cognitive decline in the elderly.22 Thus, these pathogenic mutations located in the APP672 to APP699 region of APP ectodomain (also named ED-C99) encompassing APP α- and β-cleavage sites can alter β-cleavage and Aβ-related AD pathology. However, unlike autosomal-dominant fAD, sAD patients generally lack mutations of APP gene. Therefore, the mechanisms underlying pathogenesis of sAD are still far from clarification. Here, we hypothesized that modifications (either physical or functional interactions) of regions close to APP α- and β-cleavage sites by either endogenous or exogenous molecules may yield similar impacts on human wild-type APP processing to what is observed with APP mutations.

Cell surface α-cleavage is the predominant processing pathway for human wild-type APP. In the present study, we found that the specific binding of the APP ED-C99 region with mAbED-C99 dose-dependently blocks α- but promotes β-cleavage of human wild-type APP (Figure 1). These effects were further confirmed by another specific antibody, 4G8, recognizing the ED-C99 domain (with epitope at APP688–695, data not shown). In contrast, N-terminal APP antibody 22C11 (epitope of APP66–81) or sAPPα-specific antibody mAb2B3 (epitope of APP672–688, absence of affinity to full-length APP) showed no effect on human wild-type APP processing. This lack of impact of mAb22C11 and mAb2B3 further indicates that the effect of mAbED-C99 on human wild-type APP processing is region specific. In addition, these modulations on human wild-type APP α/β-cleavage induced by mAbED-C99 can be recapitulated by using the F(ab′)2 fragment of mAbED-C99 (Figure 2). As F(ab′)2 lacks the nonspecific Fc binding subunit, these results confirm that mAbED-C99-induced modification of APP processing is ED-C99 region specific. Our present study further reveals that this α-cleavage inhibiting activity is due, in part, to the direct physical blocking of ADAM10 (Figure 3).

Previous studies have suggested that intracellular trafficking is pivotal for human wild-type APP proteolysis.12, 13 In contrast, non-amyloidogenic processing occurs mainly at the cell surface, where α-secretases are present. Amyloidogenic processing involves transit through the endocytic organelles, where APP encounters β- and γ-secretases.13, 15 In our present study, mAbED-C99 enhanced cell surface APP accumulation, which was confirmed by both WB and flow cytometry analyses, indicating that ED-C99 binding reduces the APP endocytic pathway. Blockage of human wild-type APP α-cleavage by mAbED-C99 may consequently lead to an elevated β-cleavage that has been confirmed by dramatically increased β-CTF. This suggests that ED-C99 may bind and trap APP in the membrane (or endosomes in the process of fusing with the plasma membrane), making the proteolytic sites for ADAM10 inaccessible, and thus shifting the proteolysis of APP in the plasma membrane or endosomes to β-secretase cleavage.

This proposed blockage of human wild-type APP α-cleavage by mAbED-C99 may consequently lead to an elevated β-cleavage that has been confirmed by the dramatically increased β-CTF levels on the cell surface (Figure 4). Our findings suggest that this elevated β-cleavage can be because of the cell surface APP with cholesterol colocalization (Figure 5). Indeed, growing evidence has demonstrated that cholesterol is of particular importance in regulating α- and β-cleavage of APP.15, 16, 17 Cholesterol can bind to APP696–699, an N-loop structure at the end of the ED-C99 region, thereby inhibiting α-cleavage while favoring β-cleavage of APP. In contrast to β-secretase, previous studies have indicated that γ-secretase cleavage of C99 appears to occur primarily in rafts located in the endosomes.12, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 Thus, the specific binding of mAbED-C99 to APP inhibits APP α-cleavage and endocytosis, thereby locking APP on the cell surface to be cleaved by β-secretase while functionally blocking γ-secretase from producing Aβ. This would explain how the mAbED-C99 promoted cell surface β-CTF accumulation with a concordant rise in Aβ protein levels.

In addition to cholesterol, it has also been shown that LRP1 plays a crucial role in APP processing.30, 31, 32 Multiple APP processing steps may be modulated by LRP1, most of which can be attributed to its ability to bind and endocytose APP via its LRP1-CT domain. In the absence of LRP1, APP internalization rates are reduced by ∼50%, while cell surface APP and APP-CTFs accumulate.32 In order to verify the possibility that mAbED-C99 alters APP processing by reducing endocytosis, CHO/APPwt/LRP1-CT cells were treated with mAbED-C99. Our results demonstrated a market restoration of the inhibited endocytosis, as shown by the decreased cell surface β-CTF level (Figure 6a) and increased Aβ levels (Figure 6b). Surprisingly, the reduction of sAPPα by mAbED-C99 was attenuated by LRP1-CT overexpression (Figure 6b), suggesting that LRP1 may block the mAbED-C99 binding on APP672–699 region and subsequently release APP from mAbED-C99-mediated inhibition of α-secretase.

To confirm whether the promotion of cell surface β-CTF accumulation induced by binding of mAbED-C99 to ED-C99 in vitro could be repeated in vivo, TgAPPwt mice at 8 months of age were treated (i.c.v.) with mAbED-C99 or IgG1 as negative control. We found that mAbED-C99 treatment significantly increased cell surface β-CTF, as indicated by elevated ratio of β-CTF/total APP (Figure 7b). Similar to our in vitro study, mAbED-C99 treatment also yielded no significant changes of Aβ production compared with the IgG1 control. Although the amyloid cascade hypothesis is potentially viable in cases of genetic mutation-caused autosomal-dominant fAD, accumulating evidence suggests that it may not apply in the vast majority of patients with late-onset sAD lacking mutations of APP/presenilin genes.

These works suggest several possibilities in terms of defining a possible etiology and treatment target for both fAD and sAD. First, Aβ-related plaques is one relatively common finding in the non-demented elderly. In fact, recent studies have demonstrated that accumulation of β-CTF may have direct deleterious effects on cognitive function. For example, inhibition of β-site amyloid cleaving enzyme (BACE) rescued synaptic/memory deficits in a mouse model of familial Danish dementia.33 However, γ-secretase inhibition worsened memory deficits in these mice that correlated with increased levels of APP α/β-CTFs in synaptic fractions of the hippocampus.34 In another report, prolonged (8 days) treatment with γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) produced no positive effects on memory deficits of older Swedish APP transgenic mice, but induced cognitive deficits in young Swedish APP transgenic mice or wild-type mice.35 Indeed, a recent phase III clinical trial with the GSI Semagacestat was halted because it worsened clinical measures of cognition and the ability to perform activities of daily living. These results suggest that β-CTF rather than Aβ may be more directly responsible for causing cognitive impairment associated with AD and that GSIs may worsen cognitive impairment by enhancing the accumulation of β-CTF. Our results also point to a need to identify, epidemiologically, the presence or absence of mAbED-C99-like antibodies or proteins that may increase with age and correlate with onset of AD-like signs and symptoms. In addition, this work suggests that such an antibody or protein could reduce α-secretase function and thus generation of sAPPα, a peptide that is neuroprotective.36, 37, 38

In summary, the present study verifies our hypothesis that ED-C99 region (APP672–699) is critical for human wild-type APP processing. Specific binding of this region will direct inhibit APP α-secretase activity and reduce APP endocytosis, thereby enhancing cell surface β-CTF accumulation. These effects may have deleterious effects of cognition, and this should be further explored in future studies. Modifications (physical of functional interactions) of this region with either exogenous or endogenous molecules will affect human wild-type APP processing, potentially enhancing or ameliorating the development of AD (Supplementary Figure S5).

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

Sterile and low-endotoxin antibodies were used, including anti-C-terminal human sAPPα-specific antibody 2B3 (mAb2B3; IBL, Minneapolis, MN, USA), APP66–81 antibody 22C11 (m22C11; Roche, Basel, Switzerland), specific monoclonal ED-C99 antibody (mAbED-C99, 6E10; Covance, Emeryville, CA, USA), APP C-terminal antibody pAb751/770 (EMD Biosciences, La Jolla, CA, USA), specific monoclonal antibody BAM10 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), β-actin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-pan cadherin antibody (AbCam, Cambridge, MA, USA). The sAPPα-specific 2B3 antibody was further characterized in our in vitro and in vivo systems, indicating that this antibody recognizes neither Aβ nor full-length APP. The mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment was generated using F(ab′)2 preparation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell culture and treatment

CHO cells engineered to express wild-type human APP (CHO/APPwt) were kindly provided by Dr. Steanie Hahn and Dr. Sascha Weggen (University of Heinrich Heine, Düsseldorf, Germany). Plasmid PLHCX-LRP1-CT was a generous gift from Dr. David Kang (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA). LRP1-CT was subcloned to PCDNA vector by PCR and restrict enzyme HindIII and NotI digestion. The primers were used as follows: forward 5′-AGCTCGTTTAGTGAACCGTCAGATC-3′ and reverse 5′-ATGCGGCCGCTCATGCCAAGGGGTCCCCTATC-3′. Stable cell lines were generated by transfection of PCDNA-LRP1-CT to CHO/APPwt cells and single colony was picked up after G418 administration. These cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin.39 For TgAPPwt mouse-derived cortical neurons, cerebral cortices isolated from 1-day-old TgAPPwt mice were mechanically dissociated in trypsin (0.25%) individually after incubation for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were collected after centrifugation at 1200 × g, suspended in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10% horse serum, uridine (33.6 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), and fluorodeoxyuridine (13.6 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) and seeded in 24-well collagen-coated culture plates at 2.5 × 105 cells per well. After reaching confluence (∼70–80%), cells were treated with mAbED-C99 at 0–1.25 μg/ml for 2 h. In additional experiments, cells were treated with mAb22C11 or mAb2B3 or mAbED-C99 F(ab′)2 fragment at 1.25 μg/ml.

Transgenic APPwt mice and i.c.v. injection

Transgenic wild-type B6.Cg-Tg (PDGFB-APP) 5Lms/J strain (TgAPPwt) female mice and 5 × FAD transgenic female mice (Tg6799 line) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All mice were housed and maintained in the Animal Facility of College of Medicine at University of South Florida. At 8 months of age, both mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (chamber induction at 4–5% isoflurane, intubation and maintenance at 1–2%). After reflexes were checked to ensure that mice were unconscious, they were positioned on a stereotaxic frame (Stoelting Lab Standard, Wood Dale, IL, USA) with ear-bars positioned and jaws fixed to a biting plate. The ED-C99-specific antibody mAbED-C99 and isotype control IgG1 were dissolved in sterile distilled water at a concentration of 1 μg/μl. mAbED-C99 and control IgG1 (5 μl) were injected into the left lateral ventricle with a microsyringe at a rate of 1 μl/min with the coordinates (bregma: −0.6 mm anterior/posterior, +1.2 mm medial/lateral, and −3.0 mm dorsal/ventral) according to our previous methods.36, 40 The needle was left in place for 5 min after injection before being withdrawn. At 24 h after i.c.v. injections, animals were killed with isofluorane and brain tissues were collected. All dissected brain tissues were rapidly frozen for analysis. All experiments involving mice were performed in compliance with the US Department of Health and Human Services Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and in accordance with the guidelines of the University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell surface biotinylation

Confluent cell cultures in dishes were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-CM. Cells were biotinylated with 0.5 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-LC Biotin dissolved in ice-cold borate buffer for 30 min at 4°C. Biotin was changed twice during the 30-min incubation period. Biotinylation was quenched with three 50 mM NH4Cl-PBS-CM washes followed by two PBS washes. Cells were harvested and lysed in NP-40 buffer and protein concentration was determined via BCA. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated using Neutravidinagarose beads overnight at 4°C. Proteins were eluted from the Neutravidinagarose beads by heating at 95°C for 10 min.

WB analysis

Briefly, for WB analysis, cultured cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer. Proteins were separated using 10% gel, transferred to 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and visualized using standard immunoblotting protocol. All antibodies were diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk. Blots were developed using the Luminol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and densitometric analysis was performed as described previously, using a Fluor-S MultiImager with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).40, 41

Flow cytometry analysis

CHO/APPwt cells were plated in six-well plate and treated overnight with mAbED-C99 or IgG1 isotype control. The cells were then detached by trypsin, stained with mAbED-C99 and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) for 30 min on ice, washed with Flow buffer, and analyzed by Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer (Rochester, MN, USA).

Filipin staining

After treatment, the cells were fixed and Filipin staining was performed following the manufacturer's instructions of the cholesterol assay kit (AbCam).

ELISA

Total Aβ species, including Aβ40/42, in cell conditioned media and brain homogenates were detected by Aβ1–40/42 ELISA kits (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sAPPα level in cell conditioned media was determined using sAPPα ELISA kit (IBL). Aβ and sAPPα levels are represented as ng/mg of total cellular protein.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±S.D. of n independent experiments. Comparison between two groups was performed by Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Stefanie Hahn and Dr. Sascha Weggen (University of Heinrich Heine, Düsseldorf, Germany) for generously gifting the CHO/APPwt cells. This work was supported by the NIH/NIA (R01AG032432 and R42AG031586 to J Tan) and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81200987).

Author contributions

SL performed the experiments, assisted in the design of the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; HH and J Tian performed IB, IP and IH analyses, and ELISA, and contributed to data analysis; JD performed i.c.v., IB and ELISA experiments and helped with technical issues; BG, DO, YW, DS, AS, and PRS assisted in the design of the study, manuscript composition, and editing; TM supervised IH technical issues and contributed to the IH experiment, data analysis, and the manuscript editing; J Tan designed and supervised the study, analyzed the data, and assisted in the composition and editing of the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the final version of the manuscript.

Glossary

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ADAM10

a disintegrin and a metalloproteinase 10

- BACE

β-site amyloid cleaving enzyme

- CHO/APPwt cells

Chinese hamster ovary cells stably transfected with human wild-type APP

- CTF

C-terminal fragments

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- EC

entorhinal cortex

- ED-β-CTF

ectodomain of β-C-terminal fragment

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- fAD

familial AD

- GSI

γ-secretase inhibitor

- H

hippocampus

- TgAPPwt

human wild-type APP transgenic

- i.c.v.

intracerebroventricular

- LRP1

low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1

- LRP1-CT

cytoplasmic tail of LRP1

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RSC

retrosplenial cortex

- sAD

sporadic AD

- sAPPα

soluble APPα

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- WB

western blotting

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by A Verkhratsky

Supplementary Material

References

- Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2004;430:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Aβ and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunan J, Small DH. Regulation of APP cleavage by α-, β- and γ-secretases. FEBS Lett. 2000;483:6–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Brouwers N, Benilova I, Vandersteen A, Mercken M, Van Laere K, et al. Amyloid precursor protein mutation E682K at the alternative β-secretase cleavage β'-site increases Aβ generation. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3:291–302. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasselli AG, Qahwash I, Emmons TL, Lu Y, Leone JW, Lull JM, et al. Employing a superior BACE1 cleavage sequence to probe cellular APP processing. J Neurochem. 2003;84:1006–1017. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fede G, Catania M, Morbin M, Rossi G, Suardi S, Mazzoleni G, et al. A recessive mutation in the APP gene with dominant-negative effect on amyloidogenesis. Science. 2009;323:1473–1477. doi: 10.1126/science.1168979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsberth C, Westlind-Danielsson A, Eckman CB, Condron MM, Axelman K, Forsell C, et al. The ‘Arctic' APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer's disease by enhanced Aβ protofibril formation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:887–893. doi: 10.1038/nn0901-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson DJ, Selkoe DJ, Teplow DB. Effects of the amyloid precursor protein Glu693-Gln ‘Dutch' mutation on the production and stability of amyloid β-protein. Biochem J. 1999;340:703–709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingtdeux V, Hamdane M, Gompel M, Bégard S, Drobecq H, Ghestem A, et al. Phosphorylation of amyloid precursor carboxy-terminal fragments enhances their processing by a γ-secretase-dependent mechanism. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:625–637. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinakaran G, Koo EH. Amyloid precursor protein trafficking, processing, and function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29615–29619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy RW, Cheng Z, Schekman R. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) traffics from the cell surface via endosomes for amyloid β (Aβ) production in the trans-Golgi network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2077–E2082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208635109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron E, Heilig C, Schweitzer A, Nadella N, Jaeger S, Martin AM, et al. LRP1 modulates APP trafficking along early compartments of the secretory pathway. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquer C, Devauges V, Cossec JC, Liot G, Lécart S, Saudou F, et al. Local cholesterol increase triggers amyloid precursor protein-Bace1 clustering in lipid rafts and rapid endocytosis. FASEB J. 2011;25:1295–1305. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-168633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojro E, Gimpl G, Lammich S, Marz W, Fahrenholz F. Low cholesterol stimulates the nonamyloidogenic pathway by its effect on the α-secretase ADAM 10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5815–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081612998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehehalt R, Keller P, Haass C, Thiele C, Simons K. Amyloidogenic processing of the Alzheimer β-amyloid precursor protein depends on lipid rafts. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:113–123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe C, Esselens C, Kumar-Singh S, Craessaerts K, Serneels S, Checler F, et al. Pathogenic APP mutations near the γ-secretase cleavage site differentially affect Aβ secretion and APP C-terminal fragment stability. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1665–1671. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers N, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C. Molecular genetics of Alzheimer's disease: an update. Ann Med. 2008;40:562–583. doi: 10.1080/07853890802186905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilquet V, De Strooper B. Amyloid-β precursor protein processing in neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Effects of the English (H6R) and Tottori (D7N) familial Alzheimer disease mutations on amyloid β-protein assembly and toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23186–23197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.086496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, Bjornsson S, et al. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer's disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature. 2012;488:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardia-Laguarta C, Coma M, Pera M, Clarimon J, Sereno L, Agullo JM, et al. Mild cholesterol depletion reduces amyloid-β production by impairing APP trafficking to the cell surface. J Neurochem. 2009;110:220–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzolo MP, Bu G. Lipoprotein receptors and cholesterol in APP trafficking and proteolytic processing, implications for Alzheimer's disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H, Callaghan D, Jones A, Walker DG, Lue LF, Beach TG, et al. Cholesterol retention in Alzheimer's brain is responsible for high β- and γ-secretase activities and Aβ production. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:422–437. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur JY, Welander H, Behbahani H, Aoki M, Franberg J, Winblad B, et al. Active γ-secretase is localized to detergent-resistant membranes in human brain. FEBS J. 2008;275:1174–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrivel KS, Cheng H, Lin W, Sakurai T, Li T, Nukina N, et al. Association of γ-secretase with lipid rafts in post-Golgi and endosome membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44945–44954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407986200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahrle S, Das P, Nyborg AC, McLendon C, Shoji M, Kawarabayashi T, et al. Cholesterol-dependent γ-secretase activity in buoyant cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9:11–23. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Yao PJ. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis and Alzheimer's disease: an update. Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8:147–149. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulery PG, Beers J, Mikhailenko I, Tanzi RE, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, et al. Modulation of β-amyloid precursor protein processing by the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). Evidence that LRP contributes to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7410–7415. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arelin K, Kinoshita A, Whelan CM, Irizarry MC, Rebeck GW, Strickland DK, et al. LRP and senile plaques in Alzheimer's disease: colocalization with apolipoprotein E and with activated astrocytes. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;104:38–46. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzik CU, Busse T, Merriam DE, Weggen S, Koo EH. The cytoplasmic domain of the LDL receptor-related protein regulates multiple steps in APP processing. EMBO J. 2002;21:5691–5700. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayeu R, Matsuda S, Arancio O, D'Adamio L. β- but not γ-secretase proteolysis of APP causes synaptic and memory deficits in a mouse model of dementia. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:171–179. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayeu R, D'Adamio L. Inhibition of γ-secretase worsens memory deficits in a genetically congruous mouse model of Danish dementia. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani Y, Yarimizu J, Saita K, Uchino H, Akashiba H, Shitaka Y, et al. Differential effects between γ-secretase inhibitors and modulators on cognitive function in amyloid precursor protein-transgenic and nontransgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2037–2050. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4264-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obregon D, Hou H, Deng J, Giunta B, Tian J, Darlington D, et al. Soluble amyloid precursor protein-α modulates β-secretase activity and amyloid-β generation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:777. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Furukawa K. Signaling events regulating the neurodevelopmental triad. Glutamate and secreted forms of β-amyloid precursor protein as examples. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1998;5:337–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Gary DS, Chan SL, Duan W. Perturbed endoplasmic reticulum function, synaptic apoptosis and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Soc Symp. 2001;67:151–162. doi: 10.1042/bss0670151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn S, Brüning T, Ness J, Czirr E, Baches S, Gijsen H, et al. Presenilin-1 but not amyloid precursor protein mutations present in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease attenuate the response of cultured cells to γ-secretase modulators regardless of their potency and structure. J Neurochem. 2011;116:385–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Hou H, Giunta B, Mori T, Wang YJ, Fernandez F, et al. Autoreactive-Aβ antibodies promote APP β-secretase processing. J Neurochem. 2012;120:732–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezai-Zadeh K, Shytle D, Sun N, Mori T, Hou H, Jeanniton D, et al. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modulates amyloid precursor protein cleavage and reduces cerebral amyloidosis in Alzheimer transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8807–8814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1521-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.