Abstract

Background

Pinus sylvestris, P. mugo, P. uliginosa and P. uncinata are closely related but phenotypically and ecologically very distinct European pine species providing an excellent study system for analysis of the genetic basis of adaptive variation and speciation. For comparative genomic analysis of the species, transcriptome sequence was generated for 17 samples collected across the European distribution range using Illumina paired-end sequencing technology.

Results

De novo transcriptome assembly of a reference sample of P. sylvestris contained 40968 unigenes, of which fewer than 0.5% were identified as putative retrotransposon sequences. Based on gene annotation approaches, 19659 contigs were identified and assigned to unique genes covering a broad range of gene ontology categories. About 80% of the reads from each sample were successfully mapped to the reference transcriptome of P. sylvestris. Single nucleotide polymorphisms were identified in 22041-24096 of the unigenes providing a set of ~220-262 k SNPs identified for each species. Very similar levels of nucleotide polymorphism were observed across species (π=0.0044-0.0053) and highest pairwise nucleotide divergence (0.006) was found between P. mugo and P. sylvestris at a common set of unigenes.

Conclusions

The study provides whole transcriptome sequence and a large set of SNPs to advance population and association genetic studies in pines. Our study demonstrates that transcriptome sequencing can be a very useful approach for development of novel genomic resources in species with large and complex genomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1401-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Whole transcriptome sequencing, Ontology, SNPs, Nucleotide divergence, Species complex

Background

Forest trees constitute over 80% of terrestrial biomass and harbour more than 50% of terrestrial biodiversity providing wood material and fundamental ecosystem services for humans including preservation of biodiversity, carbon cycling, climate regulation and preservation of water quality and soils [1,2]. Understanding the genomic basis of adaptation and architecture of complex phenotypic traits is needed for development of diagnostic tools for the conservation, restoration and management of natural populations and for genetic improvement programmes [2]. Understanding plant adaptation is also one of the main interests of evolutionary biology. So far however, knowledge of the mutations, genes and biochemical pathways involved in species evolution and underlying phenotypic and adaptive variation remain scarce mostly due to a lack of efficient methods for accessing the polymorphisms at the whole genome scale. Recent advances in cost-effective, high-throughput sequencing technologies provide new tools for development of genomic resources with huge potential for downstream applications in virtually any species. In particular, these Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) methods provide a unique opportunity to advance studies of non-model plants, including economically important trees with complex genomes such as conifers [3-5].

Here, we focus on a group of four closely related European pines: Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and the three taxa comprising the P. mugo complex including P. mugo Turra (dwarf mountain pine), P. uncinata Ramond (mountain pine) and P. uliginosa Neumann (peat-bog pine). These species differ from each other in phenotype, total population size, geographical distribution and ecology, in particular for traits related to dehydrative stress and temperature [6-8]. Pinus sylvestris is one of the most ecologically and economically important forest tree species in the world and has the largest distribution of all pines, being found from western Scotland to eastern Siberia and from Turkey and Spain north to the Arctic Circle. It is locally adapted to environmental conditions related to photoperiod and temperature and shows clinal latitudinal variation in timing of bud set and cold hardiness [9]. Pinus mugo is a high-altitude polycormic European pine of up to a few meters in height, which forms shrub populations above the tree line in the mountainous regions of central and southeastern Europe. Pinus uncinata and P. uliginosa are trees of up to 20 m height; the former is a forest forming component in the high mountains of Western Europe, the latter is adapted to peatbogs in lowland areas of Central Europe.

Despite clear morphological and ecological differentiation, analysis of nuclear genes showed that the species share a similar genetic background, indicating recent divergence [10]. However, despite significant inter- and intra-specific gene flow during historical range shifts, local adaptation to highly contrasting environments has occurred [10,11]. The species are not completely reproductively isolated, can occur and hybridize in sympatry and have the same number of chromosomes (2n = 24). Considering their genetic similarity, but distinctive phenotypes (tree/shrub), geographical ranges (widespread/restricted) and ecology (generalist/specialist) the species comprise a promising system for study of the genomic basis of adaptation and the genetic architecture of phenotypic traits. Taking advantage of the system for comparative studies requires development of a comprehensive array of genomic resources and methods addressing variation at the whole genome scale.

For large and complex genomes, transcriptome sequencing is an attractive alternative to whole genome sequencing, and yields a comparatively high content of functional information from coding regions. By constructing a comparative analysis within a phylogenetic framework we aimed to develop genomic resources relevant to molecular evolution in the genes and gene complexes underlying inter- and intra-specific variation in this important group of tree species.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of the transcript sequence

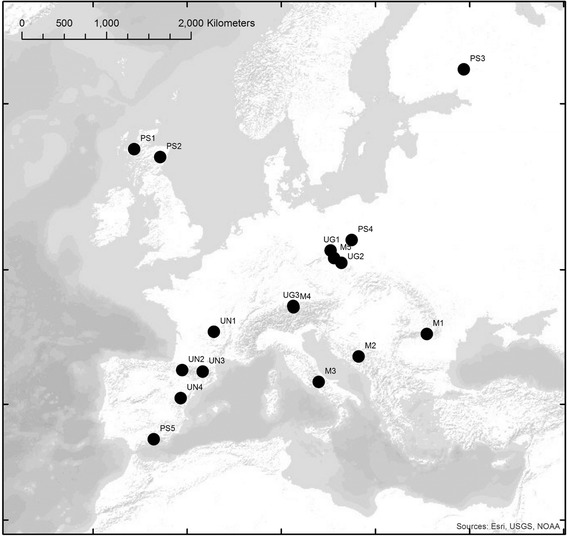

Comparative studies of closely related species can advance our understanding of the genetic architecture of adaptive traits. For many species these studies have been seriously limited by a lack of genomic resources from which to develop genetic markers for topics such as species divergence, adaptation and demographic processes in natural populations. In our study we applied Illumina sequencing for successful de novo transcriptome characterisation and development of new genomic resources in a complex of four pine species from across the species distribution range in Europe (Figure 1, Table 1). From each insert of the cDNA library, 2 × 100 bp independent reads can be obtained using Illumina paired-end sequencing technology. Our results show that this highly cost and time efficient technology is a very useful and reliable tool for transcriptome characterization, gene discovery and marker development, even for species with large and complex genomes. Sequencing of the reference Scots pine sample (2_GT_31) used for de novo transcriptome assembly produced a total of 258,401,512 raw 100 bp sequencing reads. Raw assembly of the reads produced over 151,932 contigs greater than 100 bp that contained over 119 × 106 bp (Table 2). After a series of filtering steps including searches for ORF sequences those contigs were aligned into 40968 unigenes. Retrotransposons comprise a substantial proportion of most plant genomes and they can be transcriptionally active. However, we found less than 0.5% of the unigenes contained such sequences, which is lower than has been found in other plants and pine species. For instance, in the Pinus contorta transcriptome, about 6% of contigs represented retrotransposon-like sequences [12]. The low number of retrotransposon sequences may also result from our strict filtering criteria, in which many low quality sequences were discarded before alignment. In our dataset, 170 contigs were identified as putative retrotransposon sequences and they were discarded providing a final set of 40798 high quality unigenes (with mean length of ~1500 bp) and a total reference transcriptome of 61,246,267 bp (Table 2, Additional file 1).

Figure 1.

Locations of the populations of the four pine species sampled for the study. Populations labelled PS - P. sylvestris, M - P. mugo, UN - P. uncinata, UG - P. uliginosa.

Table 1.

Plant material used for transcriptome sequencing

| Species | Acronym | Sample ID | Population | Latitude N | Longitude E | Altitude (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. sylvestris | ||||||

| PS1 | 1_SD_30 | Scotland, Shieldaig | 57°30′35″ | −5°38′24″ | 81 | |

| PS2 | 2_GT_31 | Scotland, Glen Tanar | 57°2′60″ | −2°51′36″ | 334 | |

| PS3 | 3_Punk_39 | Finland, Punkaharju | 61°45′33″ | 29°23′21″ | 80 | |

| PS4 | 4_Jar_43 | Poland, Jarocin | 51°58′20″ | 17°28′40″ | 120 | |

| PS5 | 5_Trev_37 | Spain, Trevenque | 37°05′47″ | 3°32′51″ | 1170 | |

| P. mugo | ||||||

| M1 | 6_SC_5 | Romania, Southern Carpathians, Busteni | 45°25′55″ | 25°27′06″ | 2070 | |

| M2 | 7_BH_9 | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bjelasnica Mts | 43°45′00″ | 18°13′08″ | 2120 | |

| M3 | 8_Abr_16 | Italy, Abruzzi, La Maiella | 41°46′20″ | 13°58′30″ | 2200 | |

| M4 | 9_Alps_12 | Austria, Karwendel Mts., Scharnitz | 47°22′42″ | 11°17′45″ | 1400 | |

| M5 | 10_Sdt_1 | Poland, Sudety Mts, Śląskie Kamienie | 50°46′35″ | 15°36′08″ | 1400 | |

| P. uncinata | ||||||

| UN1 | 11_CC_28 | France, Col de la Croix de Morand | 45°35′58″ | 2°50′44″ | 1200 | |

| UN2 | 12_LaT_23 | Spain, Pyrenees, La Trapa | 0°32′12″ | 42°41′19″ | 1720 | |

| UN3 | 13_VdR_17 | Andorra, Eastern Pyrenees, Vall de Ransol | 42°35′02″ | 1°38′21″ | 2025 | |

| UN4 | 14_Val_24 | Spain, Sierra de Gudar | 40°28′49″ | -0°41′51″ | 2000 | |

| P. uliginosa | ||||||

| UG1 | 15_Weg_57 | Poland, Low Silesian Pinewood, Węgliniec | 51°17′50″ | 15°14′20″ | 190 | |

| UG2 | 16_Bat_59 | Poland, Wielkie Torfowisko Batorowskie reserve | 50°27′32″ | 16°23′01″ | 750 | |

| UG3 | 17_Mit_58 | Germany, Mittenwald | 47°28′50″ | 11°16′27″ | 856 |

Table 2.

Statistics for de novo transcriptome assembly of the reference sample (2_GT_31)

| Assembly metric | Raw assembly generated from Trinity | Unigene set |

|---|---|---|

| Max contig length | 16652 | 16652 |

| Num contigs >100 | 151932 | 40798 |

| Total bases in contigs >100 | 119849194 | 61246267 |

| N50 for contigs >100 | 1555 | 2118 |

| Contigs >100 in N50 | 22593 | 9640 |

| GC contigs >100 | 41.8 | 42.5 |

| nonATGC in contigs >100 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean length for contigs >100 | 788.8 | 1501.2 |

N50 - the contig length for which the collection of all contigs of equal or longer length produces half the bases of the contigs.

Non ATGC - non ATGC bases (such as Ns).

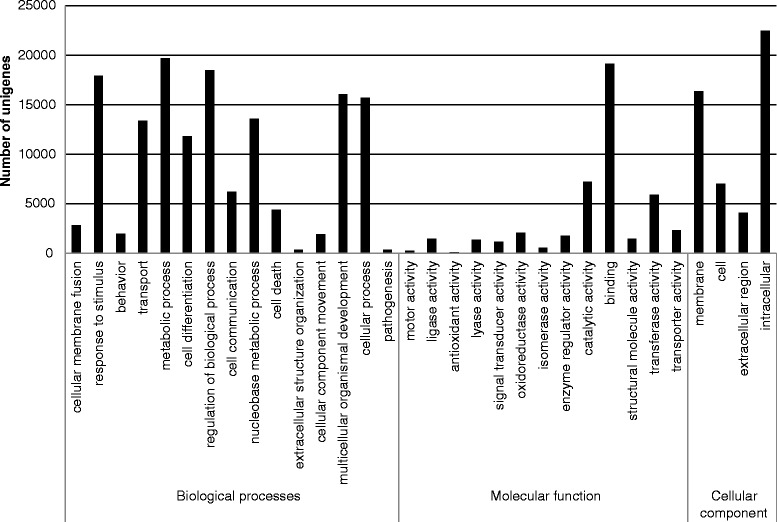

Lack of a reference genome prevented us from estimating the number of genes and transcript coverage for the focal species. However, 48% of the unigenes matched known proteins, providing large set of target genes representing various metabolic pathways. The functions of unigenes covered a broad range of gene ontology categories that were assigned to 19659 unique genes with BLAST matches to known proteins. There were a total of 13653 gene ontology terms associated with those genes. Based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway 12387 unigenes (~30%) had significant matches in the database and were assigned to 304 pathways. 9529 of the unigenes that had enzyme commission (EC) numbers were assigned to 2130 enzyme pathways. Based on biological processes the most numerous contigs were classified as related to metabolism (19727) and regulation of biological processes (18483). The function of about 43% of the unigenes was related to binding activity. About 78% of all unigenes were classified as intracellular or membrane components (Figure 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). The number of assigned contigs was similar to studies in P. contorta, when about 17000 unique genes were found across 63657 contigs developed using a 454 GS XLR70 Titanium pyrosequencer [12]. From the published gene numbers for Pinus taeda (~50,000 genes [3]) and other conifer species [4,5] we estimate that we have identified around half of the total number of Scots pine genes. Considering that the focal species are known to be highly diverged for adaptive traits, polymorphisms in the genes belonging to metabolic and regulation pathways are likely to be particularly useful for searching for the genetic basis of quantitative trait variation and local adaptation.

Figure 2.

Gene ontology classification of the unigenes.

Marker development

The focal pine species are evolutionarily closely related [10,13] but differ in ecology, geographical distribution and population size. Therefore, they form a very attractive model for studies of the genetic basis of local adaptation and speciation. So far, genetic studies of the species (mostly Pinus sylvestris) have focused on assessments of quantitative trait variation and underlying QTLs [14], genetic structure, demography and selection [15-18]. These studies were mostly based on microsatellite loci and/or sequence variation at candidate genes and consequently their conclusions were limited by the low number and resolution of markers or genomic regions. Several QTLs for phenology and polymorphism due to natural selection at a few candidate genes related to stress response were found for Scots pine [14,16,17]. Recent studies have also provided nucleotide polymorphism information for P. mugo based on amplicon sequencing and candidate gene studies [6,19]. However, no genomic resources currently exist for this group of pine species to address fundamental questions about the genetic basis of adaptation and divergence. Our study makes a large proportion of the functional variation in coding regions of the genome available for downstream research with the use of high throughput genotyping platforms. In our dataset, the 16 samples of the four pine species sequenced in lower depth produced a total of ~714 × 106 reads with their number varying between 30–69 × 106 per sample (Table 3). The vast majority of all reads for each sample (about 80%) were successfully mapped to the reference transcriptome sequence of the Scottish Pinus sylvestris sample from Glen Tanar (2_GT_31 sample). Compared to the reference, from ~64 × 103 (P. sylvestris from Finland) to ~148 × 103 SNPs (P. uliginosa from Germany) were called for each sample (Table 3). SNPs were found in 54-59% of all unigenes including 22041 unigenes with SNPs identified for P. sylvestris, 24096 for P. mugo, 22416 for P. uncinata and 22710 for P. uliginosa. Filtering of all available SNPs from merged contigs across the species that were at least 50 bp apart from each other provided a set of 259,087 SNPs (Additional file 1). The availability of cost and time efficient genotyping methods for SNPs using next-generation sequencing platforms will certainly advance comparative genomic and population genetic studies of these species. The resources could also be useful in breeding and silviculture, through marker-assisted and genomic selection approaches [20], for genetic improvement of phenotypic traits of economic and ecological importance, especially in Scots pine.

Table 3.

Mapping statistics of the samples to the reference transcriptome sequence (2_GT_31)

| Sample ID | Species | Total reads | Mapped reads | % Mapped reads | % Duplicate reads | % Mapped reads as proper pairs | Number of SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1_SD_30 | P. sylvestris | 31116472 | 26922787 | 86.52 | 26.36 | 84.14 | 67817 |

| 2_GT_31 | P. sylvestris | 258401512 | 229042493 | 88.64 | 43.22 | 85.34 | 81519 |

| 3_Punk_39 | P. sylvestris | 37849782 | 31980676 | 84.49 | 34.37 | 80.21 | 63874 |

| 4_Jar_43 | P. sylvestris | 38970706 | 31951845 | 81.99 | 19.34 | 79.47 | 94021 |

| 5_Trev_37 | P. sylvestris | 45140044 | 38150182 | 84.52 | 19.44 | 81.73 | 95814 |

| 6_SC_5 | P. mugo | 43752078 | 35804512 | 81.83 | 24.08 | 78.50 | 116762 |

| 7_BH_9 | P. mugo | 32600000 | 26565484 | 81.49 | 26.23 | 78.40 | 103818 |

| 8_Abr_16 | P. mugo | 40104880 | 33111153 | 82.56 | 29.18 | 78.19 | 100602 |

| 9_Alps_12 | P. mugo | 52934684 | 43411825 | 82.01 | 23.36 | 78.67 | 130942 |

| 10_Sdt_1 | P. mugo | 69248828 | 57560565 | 83.12 | 28.02 | 80.03 | 138989 |

| 11_CC_28 | P. uncinata | 34805254 | 28627271 | 82.25 | 16.74 | 79.34 | 102037 |

| 12_LaT_23 | P. uncinata | 30291214 | 24678075 | 81.47 | 36.80 | 78.06 | 87181 |

| 13_VdR_17 | P. uncinata | 45834740 | 36942040 | 80.60 | 18.27 | 77.85 | 118800 |

| 14_Val_24 | P. uncinata | 48550644 | 39819426 | 82.02 | 21.98 | 79.12 | 115050 |

| 15_Weg_57 | P. uliginosa | 52718596 | 42948249 | 81.47 | 18.33 | 78.55 | 127068 |

| 16_Bat_59 | P. uliginosa | 40729720 | 33913094 | 83.26 | 21.04 | 80.38 | 116297 |

| 17_Mit_58 | P. uliginosa | 69457322 | 57212028 | 82.37 | 22.07 | 79.37 | 147646 |

| Merged | All | 976529136 | 817402576 | 83.70 | 26.12 | 80.58 | 164104 |

Sample ID with reference to Table 1.

Nucleotide polymorphism and genetic relationships between species

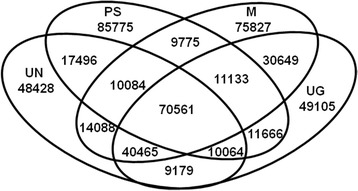

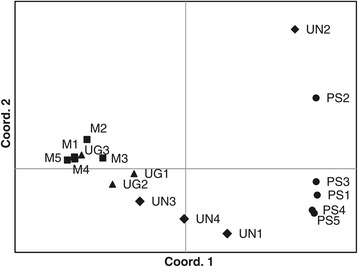

The samples from which transcriptome data were generated were collected across broad environmental gradients, throughout the species distribution range. Despite clear differences in range and total population sizes, we observed very similar levels of nucleotide polymorphism in each species. Comparing among species, and across the whole transcriptome, most SNPs were found in P. mugo (~295 × 103) relative to the reference. This species showed much greater similarity to the other two taxa from the P. mugo complex than to P. sylvestris, as evident from the higher proportion of common (~144-163 × 103) and lower proportion of unique SNPs (~93-145 × 103) between the P. mugo complex taxa as compared to P. sylvestris (~65-69 × 103 and ~190-230 × 103, respectively) (Table 4, Figure 3). All four species showed similar levels of nucleotide polymorphism (πtot = 0.0044-0.0053) and an excess of low frequency variation (D = ~ −0.2) (Table 5). Our estimates of total nucleotide polymorphism were very similar to estimates obtained from much smaller candidate gene datasets [6,16-18]. In our study nearly half of the transcriptome sequences were monomorphic across species. Overall, the species showed a high level of genetic similarity marked by similar proportions of reads from different species that mapped to the reference Scots pine transcriptome and many shared SNPs segregating between species. Our study provides evidence for closer genetic relationships between P. mugo and P. uliginosa as compared to P. sylvestris (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Pinus uncinata also showed a closer relationship to the taxa from the P. mugo complex (Figure 4, Additional file 1: Table S2) except for one outlier sample from Spain that showed closer genetic similarity to P. sylvestris. This individual may represent an admixed genotype of both species as cryptic hybrids between P. uncinata and P. sylvestris were described in Spain in morphological and molecular studies [11]. No significant genetic differentiation (p < 0.05) was found between P. mugo and P. uncinata vs. P. uliginosa (Table 6). Our results are in line with previous evolutionary assessments in these species that showed high genetic identity between the taxa from the P. mugo complex and outgroup Scots pine. The close genetic similarity between taxa (especially in the P. mugo complex) but high divergence makes them a very promising system for comparative genomic studies. Searches for loci of high divergence against the genetic background of the focal taxa will help to identify regions under selection, which have played a role in adaptation and speciation.

Table 4.

Common and unique SNPs in pair-wise comparisons between species

| Whole transcriptome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMMON SNPs | ||||

| P. sylv. | P. mugo | P. uncin. | P. ulig. | |

| P. sylvestris | 119387 | |||

| P. mugo | 65646 | 294958 | ||

| P. uncinata | 69345 | 149679 | 246367 | |

| P. uliginosa | 65390 | 162769 | 144422 | 255447 |

| UNIQUE SNPs (in reference to the species in each column) | ||||

| P. sylvestris | 229312 | 189735 | 190084 | |

| P. mugo | 53728 | 109363 | 92675 | |

| P. uncinata | 50042 | 145279 | 111026 | |

| P. uliginosa | 53997 | 132189 | 114644 | |

Total number of SNPs within each species is marked in bold.

Figure 3.

Shared and unique SNPs in pairwise comparisons between P. sylvestris (S), P. mugo (M), P. uncinata (UN) and P. uliginosa (UG). SNPs total: P. sylvestris (225544), P. mugo (262582), P. uncinata (220365), P. uliginosa (232822).

Table 5.

Nucleotide variation at 676 merged nuclear ( n DNA) contigs in the pine species

| Species | N | L | SNPs | Sing. | π tot | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. sylvestris | 5 | 1364676 | 12920 | 8674 | 0.0044 | −0.243 |

| P. mugo | 5 | 1364676 | 13129 | 8710 | 0.0045 | −0.221 |

| P. uncinata | 4 | 1364676 | 13420 | 10374 | 0.0053 | −0.169 |

| P. uliginosa | 3 | 1364676 | 9581 | 9581 | 0.0047 | - |

| Total/Aver. | 17 | 1364676 | 27929 | 12181 | 0.0047 | −0.211 |

Figure 4.

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on pairwise nucleotide difference matrix at 676 contigs (>1.3Mbp, 27929 SNPs) showing genetic relationships between P. sylvestris (●), P. mugo (■), P. uncinata (♦) and P. uliginosa (▲) samples.

Table 6.

Pairwise Fst between species at 27929 SNPs identified at 676 merged nuclear ( n DNA) contigs

| P. sylvestris | P. mugo | P. uncinata | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P. mugo | 0.257** | ||

| P. uncinata | 0.142* | 0.121* | |

| P. uliginosa | 0.212* | 0.030 | 0.075 |

Significance level: * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Conclusions

We provide a reference transcriptome sequence for Scots pine, a conifer tree species of great ecological and economic importance in the world. We annotated the transcriptome in reference to many genes and metabolic pathways described in open access databases.

Putting our study in a phylogenetic framework we provide novel genomic resources comprising a publicly-available database of SNP markers for a set of four closely related pine species. Information about nucleotide polymorphism in coding regions will facilitate genotyping, population genetic and association studies to better understand the genetic basis of plant adaptation and speciation.

Our study shows the largest genetic divergence between P. mugo and P. sylvestris. Despite large differences in distribution range and total population size, all species showed very similar patterns of nucleotide polymorphism.

Our results demonstrate the high relevance of Illumina technology for de novo assembly, transcriptome characterization and marker discovery in a species with large and complex genomes, which lack draft genome sequence information.

Methods

Plant material and RNA extraction

Needles of the four pine species were collected from two year old seedlings grown in a glasshouse at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Edinburgh, UK. The seedlings were obtained from seeds collected in seventeen populations of the species (five for each of P. sylvestris and P. mugo, four for P. uncinata and three for P. uliginosa) from across the species distribution range and environmental gradients in Europe (Table 1, Figure 1). After sampling, the needles were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with a pestle and mortar. Total RNA for generation of transcript sequence was extracted from 100 mg of the needle powder using Spectrum™ Plant Total RNA Kit (Sigma) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and quality was assessed with the use of a Qubit® Fluorometer (Life Technologies). A total of 10 μg of input RNA for each sample was used for normalized cDNA library preparation.

cDNA library construction and sequencing

Template cDNA libraries for each sample were prepared using TruSeq™ RNA Sample Preparation Kits (Illumina). The poly‐A containing mRNA molecules were purified in two steps from 10 μg of total RNA using poly‐T oligo‐attached magnetic beads. During the second elution of the poly‐A RNA, the RNA was fragmented to 120-210 bp inserts (by incubation of the samples at 94°C for 8 minutes) and primed for cDNA synthesis. The cleaved RNA fragments primed with random hexamers were reverse transcribed into first strand cDNA followed by DNA Polymerase I second strand cDNA synthesis and RNase H treatment. Ampure XP beads were used to separate the double strand cDNA from the 2nd strand reaction mix. The synthesized cDNA was subjected to end-repair to convert the overhangs resulting from fragmentation into blunt ends. These repaired cDNA fragments were adenylated at 3′ ends to prevent them from ligating to one another during the adapter ligation reaction. Paired-end adapters were ligated to the ends of these double strand cDNA preparing them for hybridization onto a flow cell. DNA fragments that had adapter molecules on both ends were enriched by PCR to amplify the amount of DNA in the final cDNA library. Normalization of cDNA was conducted to increase the chance of discovering genes of low expression level. Quality control of the sample libraries and quantification of the DNA templates was conducted using Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer using Agilent DNA1000 chip. The cDNA libraries were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform at Edinburgh Genomics, the University of Edinburgh, Scotland according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Sequencing was conducted to generate 100 base paired-end reads for all samples including the Scots pine sample (2_GT_31, Scotland, Glen Tanar) used as a reference. Raw data for all samples were deposited in European Nucleotide Archive [ENA accession number: PRJEB6877].

Reference transcriptome assembly and gene annotation

Prior to assembly, filtering of the raw reads for the reference sample 2_GT_31 was carried out to increase the quality of data and eliminate any sequencing errors. Reads with adapter contamination, potential contaminant, and poor-quality reads with ambiguous sequences “N” were discarded. Reads were de novo assembled into contigs using Trinity (version r2012-06-08) [21]. We got 151932 potential transcripts as an output. In order to reduce the redundancy in this dataset, only transcripts with ORFs were retained, and highly similar sequences were clustered (similarity level of >95%) using CD-HIT [22]. A final set of 40968 clustered transcripts was BLASTx scanned for the presence of known retrotransposons and repetitive elements known to be present in conifer genome. Several search approaches were used including queries of known retrotransposon sequences in plants (IFG7, GYMNY, PtIFG7, Ta1-3, PpRT1) and searches for terms associated with retroelements such as copia, gypsy, gag, retrotransposon, integrase, retroelement, reverse transcriptase [23-25]. Using the above approaches 170 contigs were identified that may represent transcriptionally active retroelements. They were excluded from final reference transcriptome sequences of 40798 contigs. Annotation of the clustered transcripts based on the functional category was conducted using Annot8r based on BLAST similarity searches against annotated subsets of EMBL UniProt protein sequence and functional information database using an E-value threshold of 10−5 [26]. BLASTx search was conducted against the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway with an E-value cutoff of <10−5 to annotate the genes to known proteins and to look at the networks of molecular functions and interactions of the unigenes. Gene Ontology (GO) classification of the unigenes based on BLAST matches to known proteins was conducted based on biological processes, molecular function and cellular component.

Alignment, SNP calling and filtering

The set of 40798 transcripts (2_GT_31) was used as reference for mapping reads for the 16 other samples. Alignment was performed using BWA (version 0.6.1) [27]. Duplicates were marked using Picard [28]. To eliminate errors due to indel misalignment, local realignment was conducted using GATK [29]. SNPs were called for each sample and species as compared to the reference using Samtools (version samtools-0.1.18) [28]. A set of SNPs identified across all samples was filtered to look for those suitable for genotyping platforms such as Illumina with a minimum spacing between SNPs of 50 base-pairs (bp) flanking nucleotides on either side of a SNP.

Nucleotide polymorphisms and divergence

Polymorphism and divergence were quantified within and among species to provide information about the overall pattern of nucleotide variation in the samples. The number of shared and unique SNPs was calculated based on calls from pairwise comparisons between each species. A subset of contigs were selected that were common to, and polymorphic in, all samples relative to the reference. Fasta files for each contig were produced using vcf-tools [30] and concatenated into a single sequence for each sample. In total 1,364,676 bp of DNA was aligned across 676 contigs. Basic statistics including number of polymorphic sites, nucleotide diversity (measured as the average number of nucleotide differences per site (π) between two sequences [31]) and divergence between species were estimated using DnaSP v.5 [33]. Relationships between samples were assessed using Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) based on a pairwise genetic distance matrix (number of base differences per sequence) between samples, and using the UPGMA method based on the number of substitutions per site from averaging over all sequence pairs between groups using the Tamura-Nei model [34]. Polymorphism at the common set of 676 merged nuclear contigs was used to evaluate the genetic differentiation in pairwise comparisons between species. Significance was estimated by 1000 permutations of the samples between species using Arlequin v.3.5 [35]. The outlier Pinus uncinata sample (UN2), defined based on PCoA analysis, was excluded from divergence estimates in UPGMA and the species genetic differentiation analysis.

Supporting data

The datasets supporting the results of this article are freely available through the NERC’s Environmental Information Data Centre, as follows:

-

The sequence of 40798 transcripts of the reference Scots pine sample (2_GT_31):

Filename: Reference_PS2_trinity.fasta; URL: http://doi.org/10.5285/b6900166-ded6-4f7a-8734-484b6f77b2f1

-

SNP files for each sample with reference to Scots pine transcriptome sequence (2_GT_31):

Filenames: PS1_SNPs.vcf; PS2_SNPs.vcf; PS3_SNPs.vcf; PS4_SNPs.vcf; PS5_SNPs.vcf; M1_SNPs.vcf;

M2_SNPs.vcf; M3_SNPs.vcf; M4_SNPs.vcf; M5_SNPs.vcf; UN1_SNPs.vcf; UN2_SNPs.vcf;

UN3_SNPs.vcf; UN4_SNPs.vcf; UG1_SNPs.vcf; UG2_SNPs.vcf; UG3_SNPs.vcf;

URL: http://doi.org/10.5285/b6900166-ded6-4f7a-8734-484b6f77b2f1

Acknowledgments

The cDNA library preparation and Illumina sequencing was carried out at Edinburgh Genomics, the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. The research was financially supported by NERC (grant nr. NE/H003959/1). WW acknowledges financial support from Polish National Science Centre (DEC-2012/05/E/NZ9/03476).

Additional file

Gene ontology classification of the unigenes based on biological processes, molecular function and cellular component. Table S2. Pairwise nucleotide divergence between species. Figure S1. Relationships between species based on pairwise genetic distance at 676 unigenes (27929 SNPs). Outlier P. uncinata sample (UN2) was excluded from the analysis.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WW & SC designed and planned the research; WW performed RNA extraction, contributed to data analysis and wrote the manuscript; UT analysed the data; AP contributed to data analysis; all authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for content, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Witold Wachowiak, Email: witcho@ceh.ac.uk.

Urmi Trivedi, Email: urmi.trivedi@ed.ac.uk.

Annika Perry, Email: annt@ceh.ac.uk.

Stephen Cavers, Email: scav@ceh.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Bonan GB. Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science. 2008;320(5882):1444–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1155121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neale DB, Kremer A. Forest tree genomics: growing resources and applications. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(2):111–22. doi: 10.1038/nrg2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neale D, Wegrzyn J, Stevens K, Zimin A, Puiu D, Crepeau M, et al. Decoding the massive genome of loblolly pine using haploid DNA and novel assembly strategies. Genome Biol. 2014;15(3):R59. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birol I, Raymond A, Jackman S, Pleasance S, Coope R, Taylor G, et al. Assembling the 20 Gb white spruce (Picea glauca) genome from whole-genome shotgun sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1492–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nystedt B, Street NR, Wetterbom A, Zuccolo A, Lin Y-C, Scofield DG, et al. The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. Nature. 2013;497(7451):579–84. doi: 10.1038/nature12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wachowiak W, Boratyńska K, Cavers S. Geographical patterns of nucleotide diversity and population differentiation in three closely related European pine species in the Pinus mugo complex. Bot J Linn Soc. 2013;172(2):225–38. doi: 10.1111/boj.12049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joosen R, Lammers M, Balk P, Bronnum P, Konings M, Perks M, et al. Correlating gene expression to physiological parameters and environmental conditions during cold acclimation of Pinus sylvestris, identification of molecular markers using cDNA microarrays. Tree Physiol. 2006;26:1297–313. doi: 10.1093/treephys/26.10.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boratyńska K, Boratyński A. Taxonomic differences among closely related pines Pinus sylvestris, P. mugo, P. uncinata, P. rotundata and P. uliginosa as revealed in needle sclerenchyma cells. Flora. 2007;202(7):555–69. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2006.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karhu A, Hurme P, Karjalainen M, Karvonen P, Kärkkäinen K, Neale D, et al. Do molecular markers reflect patterns of differentiation in adaptive traits of conifers? Theor Appl Genet. 1996;93(1–2):215–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00225748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wachowiak W, Palme AE, Savolainen O. Speciation history of three closely related pines Pinus mugo (T.), P. uliginosa (N.) and P. sylvestris (L.) Mol Ecol. 2011;20(8):1729–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jasińska AK, Wachowiak W, Muchewicz E, Boratyńska K, Montserrat JM, Boratyński A. Cryptic hybrids between Pinus uncinata and P. sylvestris. Bot J Linn Soc. 2010;163(4):473–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8339.2010.01065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parchman T, Geist K, Grahnen J, Benkman C, Buerkle CA. Transcriptome sequencing in an ecologically important tree species: assembly, annotation, and marker discovery. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1):180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grotkopp E, Rejmanek M, Sanderson MJ, Rost TL. Evolution of genome size in pines (Pinus) and its life-history correlates: Supertree analyses. Evolution. 2004;58(8):1705–29. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hurme P, Sillanpaa MJ, Arjas E, Repo T, Savolainen O. Genetic basis of climatic adaptation in Scots pine by Bayesian quantitative trait locus analysis. Genetics. 2000;156(3):1309–22. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.3.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyhäjärvi T, Garcia-Gil MR, Knürr T, Mikkonen M, Wachowiak W, Savolainen O. Demographic history has influenced nucleotide diversity in European Pinus sylvestris populations. Genetics. 2007;177(3):1713–24. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.077099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wachowiak W, Balk P, Savolainen O. Search for nucleotide diversity patterns of local adaptation in dehydrins and other cold-related candidate genes in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2009;5(1):117–32. doi: 10.1007/s11295-008-0188-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kujala S, Savolainen O. Sequence variation patterns along a latitudinal cline in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris): signs of clinal adaptation? Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2012;8(6):1451–67. doi: 10.1007/s11295-012-0532-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wachowiak W, Salmela MJ, Ennos RA, Iason G, Cavers S. High genetic diversity at the extreme range edge: nucleotide variation at nuclear loci in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) in Scotland. Heredity. 2010;106:775–87. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosca E, Eckert AJ, Di Pierro EA, Rocchini D, La Porta N, Belletti P, et al. The geographical and environmental determinants of genetic diversity for four alpine conifers of the European Alps. Mol Ecol. 2012;21(22):5530–45. doi: 10.1111/mec.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zapata-Valenzuela J, Isik F, Maltecca C, Wegrzyn J, Neale D, McKeand S, et al. SNP markers trace familial linkages in a cloned population of Pinus taeda-prospects for genomic selection. Tree Genetics & Genomes. 2012;8:1307–18. doi: 10.1007/s11295-012-0516-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protocols. 2013;8(8):1494–512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(23):3150–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morse AM, Peterson DG, Islam-Faridi MN, Smith KE, Magbanua Z, Garcia SA, Kubisiak TL, Amerson HV, Carlson JE, Nelson CD et al.: Evolution of Genome Size and Complexity in Pinus. PLoS ONE 2009, 4(2). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Rocheta M, Cordeiro J, Oliveira M, Miguel C. PpRT1: the first complete gypsy-like retrotransposon isolated in Pinus pinaster. Planta. 2007;225(3):551–62. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovach A, Wegrzyn JL, Parra G, Holt C, Bruening GE, Loopstra CA, et al. The Pinus taeda genome is characterized by diverse and highly diverged repetitive sequences. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1):420. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmid R, Blaxter M. annot8r: GO, EC and KEGG annotation of EST datasets. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(15):2156–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nei M. Molecular evolutionary genetics. New York: Columbia University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–95. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10(3):564–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]