Abstract

As an intracellular Ca2+ release channel at the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, the ubiquitous inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptor (InsP3R) plays a crucial role in the generation, propagation and regulation of intracellular Ca2+ signals that regulate numerous physiological and pathophysiological processes. This review provides a concise account of the fundamental single-channel properties of the InsP3R channel: its conductance properties and its regulation by InsP3 and Ca2+, its physiological ligands, studied using nuclear patch clamp electrophysiology.

Keywords: Intracellular calcium; inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; ion channel; calcium signal; patch clamp electrophysiology; endoplasmic reticulum

1. Introduction

The ubiquitously expressed inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) receptor (InsP3R) is mostly localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane [1], where it functions as an ion channel to release Ca2+ stored in the ER lumen (Ca2+ER) into the cytoplasm to raise the cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) when it is activated by its physiological ligand, InsP3, generated in the cytoplasm as part of a signal cascade resulting from activation of specific plasma membrane receptors by various extracellular stimuli [2]. InsP3R thus plays a crucial role in the generation, propagation and regulation of cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Ca2+i) signals that regulate numerous physiological and pathophysiological processes. It is therefore not surprising that it has been the subject of intense study ever since its identification [3]. Many aspects of the InsP3R channel have been extensively reviewed recently, including its molecular structure [4–7] and its regulation by phosphorylation [8], redox reagents [9, 10] and ATP [8]. Thus, this short review will focus on the more fundamental properties of the single InsP3R channel: its ion conductance properties and its regulation by its physiological ligands—InsP3 and Ca2+, especially those reported since our previous reviews of single InsP3R channel properties [11, 12].

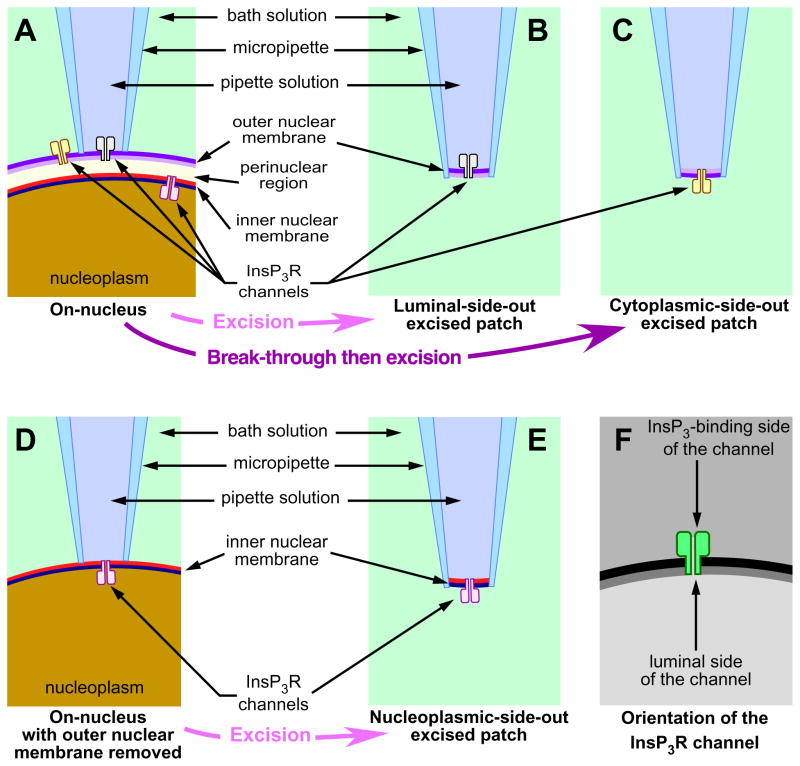

Studies of individual InsP3R channels began with the reconstitution of isolated and purified functional InsP3R channels in artificial planar lipid bilayers [13], which allows the reconstituted channel(s) to be studied with known and rigorously controlled ionic and ligand conditions on both its cytoplasmic and luminal sides [14]. Because of the intracellular localization of the InsP3R, application of patch clamp electrophysiology to investigate behaviors of the InsP3R channel in a more native membrane environment was not feasible until isolated nuclei were used as surrogate for the ER [15, 16] because of the continuity of the outer nuclear membrane with the ER [17]. Since isolated nuclei with intact outer nuclear membranes can be obtained with high success rates [18], nuclear patch clamping in the “on-nucleus” configuration (Fig. 1A) preserves the protein environment on the luminal side of the recorded InsP3R channel(s) while maintaining rigorous control of ligand and ionic conditions on both sides of the channel(s) [19]. Combining rapid perfusion techniques with nuclear patch clamping in luminal-side-out (lum-out) (Fig. 1B) or cytoplasmic-side-out (cyto-out) (Fig. 1C) configurations allows rapid (~ ms), repeated (tens of times in one experiment) and reversible exchange of the bath solution to study dynamic responses of InsP3R channel activity to abrupt changes in InsP3 and Ca2+ concentrations on either side of the channel, as well as to compare the gating and conductance properties of the same channels in the same isolated membrane patches under different ionic environments [19]. Performing nuclear patch clamping on an isolated nucleus with its outer nuclear membrane stripped by chemical treatment [20, 21] (Fig. 1D) can achieve the nucleoplasmic-side-out (nucleo-out) configuration (Fig. 1E) to study InsP3R localized to the inner nuclear membrane [20, 22].

Fig. 1. Different configurations for nuclear patch clamping experiments.

Schematic diagrams illustrating the orientation of InsP3R channels in nuclear membrane patches in various configurations of nuclear patch-clamp experiments. (A) On-nucleus configuration with outer nuclear membrane intact, (B) excised luminal-side-out configuration, (C) excised cytoplasmic-side-out configuration, (D) on-nucleus configuration with outer nuclear membrane removed, (E) excised nucleoplasmic-side-out configuration. (F) Diagram showing how the two aspects of the InsP3R channel are represented in this figure. Figure modified from [19].

Single-channel properties of the InsP3R channel have also been studied by applying whole-cell patch clamp techniques to chicken lymphocyte DT40 cells [23–29], in which InsP3R channels are localized to the plasma membrane at very low density (< 5 channels/cell) [24]. However, the lipid and protein environments around these InsP3R channels in the plasma membrane are different from those around the ER channels, and conductance and ligand regulation of InsP3R channels in the two locations were significantly different [19]. Strictly speaking, InsP3R channels localized to the plasma membrane are acting as plasma membrane Ca2+ entry channels rather than intracellular Ca2+ release channels [23].

Ca2+ signals generated by InsP3R channels located in the ER near the plasma membrane in intact mammalian cells can also be studied using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy [30]. By using a fast [Ca2+] indicator dye and loading Ca2+ buffer (EGTA) into cells to rapidly sequester Ca2+ released by active InsP3R channels, spatial and temporal resolution of observed Ca2+ signals were sufficiently improved so that Ca2+ release by single InsP3R channels can be imaged. With such “optical patch-clamping”, many individual channels can be monitored in their native environment in intact cells, thereby preserving the interaction between an active InsP3R channel with neighboring channels mediated by Ca2+ released by the active channel. However, to date, the temporal resolution and signal-to-noise ratio of electrophysiological patch clamping are still substantially superior to those of optical patch clamping. Thus, optical and electrophysiological patch clamping are mutually complimentary techniques to study InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ signals.

Another factor besides the intracellular location of the InsP3R that complicates the study of InsP3R channels is the primary amino acid sequence diversity of the channels. Vertebrates have three isoforms of InsP3R: types 1 (InsP3R-1), 2 (InsP3R-2) and 3 (InsP3R-3) that are encoded by three separate genes and are ~ 60–80% homologous. Invertebrates have only one InsP3R that is most closely related to InsP3R-1. Alternate splicing further enhances diversity of InsP3R. InsP3R-1 has three major splice regions (S1, S2 and S3), and a few minor ones. Mammalian neuronal cells express the S2+ variant while other peripheral cells express mainly the S2− form. InsP3R-2 has at least one splice region. The invertebrate InsP3R also has multiple splice variants. Given that most vertebrate cells express multiple InsP3R isoforms in various levels, and InsP3R can form homo- and heterotetrameric channels, the diversity at the InsP3R channel level can be impressive indeed (see [11] and references therein).

To avoid possible complications arising from heterotetrameric channels, initial studies of InsP3R channel used cells or tissues that were known to express predominantly one InsP3R isoform [31], like cerebellum [32] for InsP3R-1 S2+, Xenopus oocytes [15, 16] for InsP3R-1 S2− [33], ventricular cardiac myocytes [34] for InsP3R-2, RIN-5F insolinoma cells [35] for InsP3R-3, and insect Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 cells [36] for invertebrate InsP3R. Nevertheless, the possibility that these cells may express different splice variants of the same InsP3R isoforms cannot be ruled out. To address that concern, recombinant InsP3R were over-expressed in cells determined to have low expression levels of endogenous InsP3R, like Xenopus oocytes [37], COS-1 [38], COS-7 [39] and Sf9 cells [40]. However, all of those cells still express endogenous InsP3R that can oligomerize with the recombinant InsP3R to form contaminating heterotetrameric channels. A mutant cell line (DT40-3KO) derived from a chicken B cell line was finally generated with all three endogenous InsP3R genes disrupted [41]. To date, it is still the only cell line available that has truly no endogenous InsP3R background. This cell line has been used to generate cells stably expressing a single recombinant InsP3R isoform (mutant or wild type) for single-channel studies of homotetrameric channels [42].

2. Conduction properties of InsP3R

The conduction properties of a channel are one kind of information about protein ion channels that can only be obtained through single-channel studies. Such data in sufficient quantity can be used to inform the modeling of the structure of the channel pore [43, 44]. Practically, conduction characteristics, especially the channel conductance, are used to confirm the identity of the channel observed, especially in nuclear patch clamp experiments in on-nucleus or lum-out configurations, for which verifying the InsP3 dependence of the observed channels by changing [InsP3] in the cytoplasmic (pipette) solution is difficult.

2.1. Monovalent cation conductance

The most relevant channel conductance value is that observed when the channel is in physiological ionic conditions: symmetric [K+] of ~140 mM. This was not measured in planar lipid bilayer experiments [45, 46], probably due to the presence of contaminating channels in the reconstituted preparation. In nuclear patch clamp experiments in the absence of divalent cations, InsP3R channels have linear, ohmic current-voltage (I–V) relation over a broad range of applied voltages (± 60 mV). Conductance values given below were measured for InsP3R channels in outer nuclear membrane in symmetric 140 mM KCl unless stated otherwise.

The endogenous InsP3R-1 S2− channel in Xenopus oocytes has a conductance of 370 ± 5 pS [47]. The endogenous rat InsP3R-1 S2+ channel in the inner nuclear membrane of Purkinje neurons has a conductance of 356 ± 4 pS in 150 mM KCl [20]. Comparable conductance values of 366 ± 5 pS and 378 ± 11 pS (in 150 mM KCl) were observed for endogenous rat InsP3R-1 S2+ channels in the inner nuclear membrane of CA1 pyramidal neurons and dentate gyrus granule neurons, respectively [22]. The endogenous InsP3R-1 S2+ channel in mouse embryonic cortical neurons has a conductance of 375 pS [48]. Recombinant rat InsP3R-1 S2− and S2+ channels expressed in COS-7 cells have conductance values of 389 ± 5 pS and 369 ± 6 pS, respectively [39]. Recombinant rat InsP3R-1 S2+ channel expressed in DT40-3KO cells exhibits a conductance of 373 ± 2 pS [49].

A conductance of 375 ± 5 pS was observed for recombinant InsP3R-2 channel expressed in DT40-3KO cells [50], identical to that for InsP3R-1 S2+ channel measured by the same lab [49].

A conductance of 358 ± 8 pS was observed for InsP3R channels in Xenopus oocytes with low expression levels of endogenous InsP3R-1 injected with recombinant rat InsP3R-3 cRNA [37]

These conductance values measured by different labs from endogenous and recombinant channels of different InsP3R isoforms in multiple cell types were in remarkable agreement, suggesting that the high degree of sequence homology in the pore-forming regions (the pore helix, the selectivity filter together with transmembrane helices 5 and 6) among the three vertebrate InsP3R isoforms [51] plays a crucial role in determining the channel conductance.

However, the picture is not so simple. Our lab that recorded the conductance of InsP3R-3 channel expressed by cRNA injection in Xenopus oocytes also reported a significantly bigger conductance of 545 ± 7 pS for recombinant rat InsP3R-3 channel expressed in DT40-3KO cells [52]. Furthermore, another lab consistently reported two significantly lower conductance values of ~ 200 pS and ~ 120 pS for both recombinant rat InsP3R-1 S2+ [23, 53] and rat InsP3R-3 channels [54, 55] expressed in DT40-3KO cells. It was unlikely that the lower conductance values arose from substates occasionally observed in InsP3R channels [15, 52] since channels in the same nuclear membrane patches always exhibited the same conductance, and transitions from one conductance to another were never observed in single-channel membrane patches [54]. Other labs studying the same homotetrameric InsP3R channels in the same DT40-3KO system have not reported such dual conductance values for the same kind of InsP3R channel, and there is as yet no satisfactory explanation for the phenomenon.

Interestingly, a similar low conductance of ~ 200 pS was observed by two different labs using whole-cell patch clamping for plasma membrane-localized InsP3R channels formed by endogenous chicken InsP3R in wild-type DT40 cells [23]; and recombinant rat InsP3R-1 S2+ [23, 25], rat InsP3R-1 S2− [27] and mouse InsP3R-2 [26] expressed in DT40-3KO cells.

These diverse conductance values for InsP3R channels suggest that besides the primary sequence of the pore-forming regions of the InsP3R, other factors, like the membrane environment around the channel, can also substantially affect the conductance of InsP3R channels.

The conductance of 475 pS [48] for endogenous InsP3R channels in human B lymphoblasts [48] is probably that of a heterotetrameric InsP3R channel since it is different from any of the conductance values reported for homotetrameric channels.

The invertebrate InsP3R is most closely related to InsP3R-1 in its sequence. Endogenous invertebrate InsP3R from Sf9 cells has a conductance of 477 ± 3 pS [36]. It is not sure if the similarity of this conductance value to that of the lymphoblast channel is coincidence or not.

2.2. Channel conductance in the presence of divalent cations

Localized to the ER membrane, InsP3R channels are exposed to symmetric ~ mM Mg2+ and [Ca2+] of a few hundred μM on their luminal side. In such ionic conditions, the I-V relation of the channel becomes nonlinear with significantly lower slope conductance values [15, 20, 22, 37, 47, 52]. This indicates that divalent cations are permeant ion blockers of the InsP3R channels due to the presence of high affinity divalent cation binding site(s) in the channel pore. Although divalent cations can pass through the channel pore, they bind strongly to some site(s) in the pore and interfere with the flow of K+ through the channel.

For InsP3R-3 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells, divalent cations can only block the InsP3R channel partially and Mg2+ blocks the channel to the same extent whether it is on the cytoplasmic side or luminal side of the channel, suggesting that the channel has one unique saturable divalent cation binding site in the ion permeation pathway that is equally accessible from either side of the channel. This site has a substantially higher affinity for Ca2+ over Mg2+ since the half-maximal blocking concentration for Mg2+ is about twice that for Ca2+. However, at saturating concentrations, both Ca2+ and Mg2+ block the channel to the same extent [52].

Permeability ratios of various ions through different InsP3R channels can be evaluated from reversal potentials measured in asymmetric ionic conditions using the general Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation [52] (tabulated in Table 1). The permeability sequence of PCa > PBa > PMg > PK > PCl is generally preserved for all InsP3R channels in nuclear envelope studied. The ratios show that even though the InsP3R is a Ca2+-release channel, it is relatively non-selective for Ca2+ compared with plasma membrane Ca2+ channels. For a cation channel, it even has rather high permeability for Cl−. The high permeability of InsP3R channels for K+ and Cl− suggests that Ca2+ efflux from the ER lumen through an open InsP3R channel to the cytoplasm during an InsP3-induced Ca2+ release event can be sufficiently balanced by countercurrents of K+ and Cl−through the same open channel to maintain electrical neutrality of the ER lumen [56].

Table 1.

Permeability ratios of InsP3R channels in nuclear envelope

| InsP3R channel | Permeability ratios

|

references | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCa | PBa | PMg | PK | PCl | ||||||

| Xenopus InsP3R-1a | 7.6 | : | 4.3 | : | 3.2 | : | 1 | : | 0.23 | [11] |

| Rat InsP3R-1a | 6.6 | : | 6.5 | : | 1 | [22] | ||||

| Sf9 InsP3Ra | 10 | : | 6.8 | : | 1 | : | 0.22 | [36] | ||

| Rat InsP3R-1b | 4.3 | : | 1 | : | 0.07 | [39] | ||||

| Rat InsP3R-3b | 15.2 | : | 11.8 | : | 10.2 | : | 1 | : | 0.27 | [52] |

endogenous channels

recombinant channels

2.3. Unitary Ca2+ current through the InsP3R channel in physiological ionic conditions

Since the fluxes of Ca2+ and K+ through the InsP3R channel are not independent, the magnitude of the Ca2+ flux through the channel under physiological ionic conditions cannot be evaluated using the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation and must be determined experimentally. Despite the large K+ conductance of InsP3R channels, the relatively low Ca2+ permeability of the channels and the low (~ 0.5 mM) [Ca2+] gradient across the ER membrane suggest that the Ca2+ current driven through a single open InsP3R channel by the ER [Ca2+] gradient (unitary Ca2+ current) is probably < 200 fA. Such signals are less than the noise (instrumental and thermal) observed in nuclear patch clamp experiments.

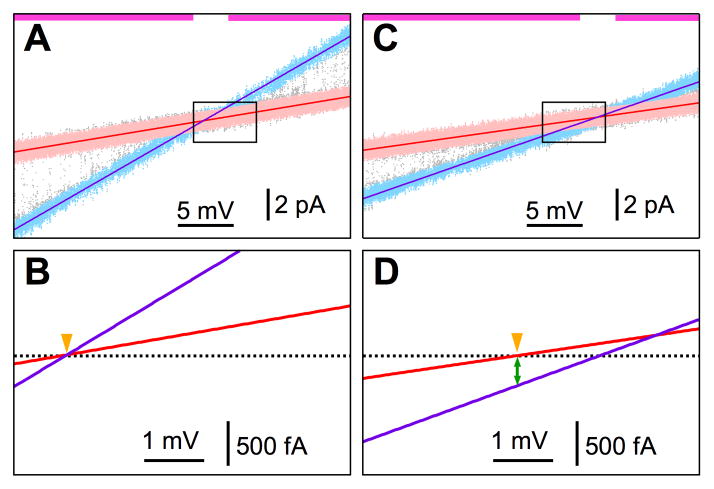

To overcome this obstacle to measure iCa [52], instead of trying to measure the unitary Ca2+ current (iCa) driven by a physiological [Ca2+] gradient at constant zero applied voltage (Vapp), a voltage ramp was applied so that for part of the ramp (magenta bars at top of Fig. 2A and C), the open channel current (Iopen, blue data points in Fig. 2A and C) could be clearly distinguished from the closed channel leak current (Iclosed, pink data points in Fig. 2A and C). Iopen and Iclosed data points were manually selected and linear fitted (purple and red lines in Fig. 2). To measure iCa with high accuracy, any offset voltage in the instrument must be compensated precisely. This was done for each experiment by applying rapid perfusion techniques to excised lum-out outer nuclear membrane patches. With 140 mM KCl and no Ca2+ in both the pipette and bath solutions, no current would pass through the non-selective leak or the open Ca2+-selective InsP3R channel when there was no electrical potential gradient across the isolated nuclear membrane. Therefore the intersection of the lines fitted to Iopen and Iclosed (indicated by orange arrowhead in Fig. 2B) marked the zero current level for that experiment (black dotted line in Fig. 2B). When the bath solution was changed to one containing physiological levels of free Ca2+ on the luminal side of the channel (Ca2+ER) besides 140 mM KCl, the non-selective Iclosed should still be zero when there was no electrical potential gradient across the membrane (orange arrowhead in Fig. 2D). The current passing through the open InsP3R channel at that point was therefore iCa (green double arrow in Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. Measurement of unitary Ca2+ current through a type 3 InsP3R channel in physiological ionic conditions.

(A) Linear fits (purple and red lines) to selected open-channel current (Iopen) and closed-channel leak current (Iclosed) vs. Vapp data (blue and pink points, respectively) from a single-channel nuclear patch clamp experiment in excised lum-out configuration under symmetric ionic conditions with pipette and perfusion solutions containing 140 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, and 3 μM free [Ca2+]. Pipette solution contained 2 μM InsP3. (B) Fitted Iopen-Vapp and Iclosed-Vapp lines in I-Vapp region marked by the black rectangle in (a). Zero-current level (black dotted line) established at the intersection of the I-Vapp fits at Vapp = 0 (marked by orange arrowhead). (C) Linear fits to Iopen and Iclosed data from Vapp ramps recorded for the same membrane patch under asymmetric ionic conditions with perfusion solution containing 2 mM CaCl2. Color and symbol conventions, I and Vapp ranges are the same as in (a). (D) Fitted I–V lines in the same I–V region and with the same zero-current level as (b). Vapp = 0 (marked by orange arrowhead) at the intersection of the Iclosed-Vapp line and zero-current level. Unitary Ca2+ current is Iopen at Vapp = 0 (marked by green double arrow). Figure modified from [52].

For homotetrameric InsP3R-3 expressed in DT40-3KO cells, iCa is linearly related to the free Ca2+ concentration gradient across the InsP3R channel for physiological levels of free [Ca2+] in the ER lumen ([Ca2+]ER), with a slope of 0.30 ± 0.02 pA/mM. The linear relation is not surprising since in the absence of electrical potential gradient, the [Ca2+] gradient across the ER membrane provides the only driving force to move Ca2+ across the channel. Interestingly, the magnitude of iCa is not affected by physiological levels of free [Mg2+] or free [Cl−] [52]. This may be due to the greater affinity for Ca2+ over Mg2+ of the divalent cation-binding site in the channel pore.

For a non-depleted ER Ca2+ store with [Ca2+]ER ~ 0.5 mM, iCa ~ 0.15 pA [52]. This agrees reasonably well with estimation of Ca2+ flux (~ 0.1 pA) observed for individual InsP3R channels in intact cells by optical patch clamping [30]. This is a substantial Ca2+ flux that can raise the [Ca2+]i in the vicinity of an open InsP3R channel to produce positive feed-through regulation of the gating properties of the open channel itself ([57] and section 3.3 below). Furthermore, Ca2+ flux through a single InsP3R channel sufficiently activated by InsP3 can recruit neighboring InsP3R channels in a cluster through calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) into coordinated opening [58, 59] to generate elementary Ca2+ release events (puffs) [60].

3. Steady-state regulation of InsP3R channel by InsP3 and Ca2+i

3.1. Regulation of InsP3R channel gating by Ca2+i

The biphasic regulation of InsP3R channel activity (open probability, Po) by Ca2+i was the first regulatory mechanism for the channel explored after discovery of its activation by InsP3 [32]. Even in saturating levels of [InsP3] (see below), InsP3R Po is very low at resting (~ 50 nM) [Ca2+]i. Channel Po increases as [Ca2+]i is raised, up to a maximum activating [Ca2+]i. Beyond a minimum inhibitory [Ca2+]i, increases in [Ca2+]i reduce channel Po (Fig. 3A). The biphasic regulation by Ca2+i suggests that the InsP3R has at least two functional cytoplasmic Ca2+-binding sites: a high-affinity activating one and a low-affinity inhibitory one. If the Ca2+ affinity of the activating site is substantially higher than that of the inhibitory site, then the activating site can be saturated at some [Ca2+]i before the inhibitory site starts to bind Ca2+ appreciably, and the Ca2+-dependence curve of the channel has a plateau region between the maximum activating [Ca2+]i and the minimum inhibitory [Ca2+]i. If the Ca2+ affinity of the activating site is similar to or lower than that of the inhibitory site, then Ca2+ binding to the inhibitory site can occur even at [Ca2+]i that is sub-saturating for the activating site, then the maximum activating [Ca2+]i and the minimum inhibitory [Ca2+]i coincide, and the Ca2+-dependence curve has a distinct peak.

Fig. 3. Ligand dependencies of gating of homotetrameric recombinant InsP3R channels of various isoforms expressed in DT40-3KO cells.

(A) Typical single-channel on-nucleus patch-clamp current traces of InsP3R-3 channels in sub-optimal (190 nM), optimal (2μM) and inhibitory (23 μM) [Ca2+]i in the presence of saturating (10 μM) [InsP3]. Vapp = –40 mV. Arrow indicates closed channel baseline current level for these and all subsequent current traces. (B–D) [Ca2+]i-dependencies of mean channel Po in various [InsP3] and [ATP4−] as tabulated, for rat InsP3R-1, mouse InsP3R-2 and rat InsP3R-3 channels, respectively. Curves are fitted to mean Po data points using the empirical biphasic Hill equation with 5 parameters [11]. Data in (b) and (c) are from [50]. (a) and (d) are modified from [57].

This regulation has been studied for both endogenous and recombinant channels of all three InsP3R isoforms in many different cell types using both reconstitution into artificial lipid bilayer and nuclear patch clamping techniques. A remarkably wide variety of Ca2+ dependencies were observed, with both plateau- and peak-shaped dependence curves [11, 12]. In particular, the same recombinant InsP3R channel expressed in different cell types can display very different Ca2+ dependencies even when studied with the same nuclear patch clamping technique. Rat InsP3R-3 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells [57] are more than ten-fold less sensitive to Ca2+ activation than those expressed in Xenopus oocytes [61]. Rat InsP3R-1 S2+ channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells [50] are activated significantly more abruptly within a narrower range of [Ca2+]i (more cooperatively) than those expressed in COS-7 cells [39]. This suggests that Ca2+ regulation of InsP3R channel activity can be quite labile, affected by various cytoplasmic factors and conditions besides the primary sequence of the channels, thereby allowing the magnitude and even the nature of the InsP3R-mediated intracellular Ca2+ signals to be delicately tuned by multiple regulatory factors besides the primary InsP3R ligands. The inhibitory site of the endogenous Xenopus InsP3R-1 can even be rendered completely insensitive to Ca2+ irreversibly by temporary exposure to non-physiological low [Ca2+]i (< 10 nM) [62]. Such environmental disruption of the inhibitory Ca2+ site is probably the reason behind reports of lack of Ca2+ inhibition for some InsP3R channels [34, 35, 46].

Another known factor that modifies Ca2+ sensitivities of InsP3R is ATP4−, which allosterically enhances the sensitivity to Ca2+ activation of endogenous Xenopus InsP3R-1 channel [11], recombinant rat InsP3R-3 channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes [63], and recombinant InsP3R-1 channel expressed in DT40-3KO cells [50]. In recombinant InsP3R-1 [50] and InsP3R-3 [11] channels, ATP4− also increases the sensitivity of the InsP3R channels to Ca2+ inhibition, thus left-shifting the Ca2+-dependence curve. In contrast, ATP4− does not affect the sensitivities of recombinant mouse InsP3R-2 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells to Ca2+ activation or inhibition [50]. Besides sensitivity to Ca2+ regulation, ATP4− also modifies the cooperativity of Ca2+ activation of InsP3R channels, but does not affect the cooperativity of their inhibition by Ca2+ [50, 63]. It is somewhat paradoxical that ATP4− reduces the cooperativity of Ca2+ activation of rat InsP3R-1 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells [50] and rat InsP3R-3 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes [11] in a similar way, but does not affect the Ca2+ activation cooperativity of native InsP3R-1 channels in Xenopus oocytes [11].

To control for various factors that affect Ca2+ regulation of InsP3R channels, recombinant channels in DT40-3KO cells expressing the three isoforms individually should be studied under the same conditions (especially [ATP4−]) using the same experimental method. Although these experiments have been done [50, 57], [ATP4−] used in those experiments were not the same, complicating comparisons of Ca2+ regulation of homotetrameric channels of different InsP3R isoforms. Fortunately, Ca2+ regulation of InsP3R-2 channel is not sensitive to [ATP4−] [50] so it can be used as the reference to be compared with the channels of the other isoforms (Fig. 3B–D). In saturating [InsP3] (see below), InsP3R-3 channels are over 10-fold less sensitive to Ca2+ activation than InsP3R-2, and about 4-fold less sensitive to Ca2+ inhibition (Fig. 3C and D). Ca2+ activation of InsP3R-3 is also significantly less cooperative than that of InsP3R-2. Cooperativity of Ca2+ inhibition is similar for the two isoforms. In 5 mM ATP4−, sensitivities to both Ca2+ activation and inhibition are similar for InsP3R-2 and InsP3R-1, but both Ca2+ activation and inhibition of InsP3R-2 are more cooperative than those of InsP3R-1 (Fig. 3B and C). In low 0.1 mM ATP4−, InsP3R-1 channel is about 4-fold less sensitive to Ca2+ activation and nearly 15-fold less sensitive to Ca2+ inhibition than InsP3R-2. However, Ca2+ activation of InsP3R-1 channel is substantially more cooperative than that of InsP3R-2, whereas its Ca2+ inhibition remains less cooperative than that of InsP3R-2.

3.2. InsP3 regulation of InsP3R channel gating

InsP3 is the natural ligand of InsP3R channels [2] that activates the channel saturably. Three different forms of InsP3 modulation of InsP3R channel gating have been reported.

The first form reported is through tuning the sensitivity of the channel to Ca2+ inhibition. This has been observed in endogenous InsP3R-1 S2− channels in Xenopus oocytes, endogenous Sf9 InsP3R, recombinant rat InsP3R-3 expressed in Xenopus oocytes [11] and DT40-3KO cells [57] studied using nuclear patch clamping (Fig. 3D), as well as in endogenous rat InsP3R-1 channels reconstituted into lipid bilayers [64]. Even at saturating 10 μM InsP3 (found to be saturating in all nuclear patch clamp studies of InsP3R channels), Ca2+ at high enough concentrations still inhibits InsP3R channels. When [InsP3] is reduced to sub-saturating levels, reduction of [InsP3] increases the sensitivity of the channel to Ca2+ inhibition, thereby decreasing the range of [Ca2+]i within which InsP3R channel activity can be observed. At low enough [InsP3], the channel becomes more sensitive to Ca2+ inhibition than Ca2+ activation, and the channel starts to be inhibited before it is fully activated so the maximum channel Po is decreased [11, 57]. In this kind of InsP3 regulation, only the sensitivity of the channel to Ca2+ inhibition is modulated. The sensitivity of the channel to Ca2+ activation and the levels of cooperativity of the activation and inhibition are not affected [11, 57].

Another form of InsP3 regulation of InsP3R channel Po is by changing the maximum channel activity level. This was first reported for endogenous InsP3R-1 S2+ channels in the inner nuclear membrane of rat Purkinje neurons [20], and was also observed in recombinant rat InsP3R-1 and mouse InsP3R-2 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells [50] (Fig. 3B and C). For these channels, as [InsP3] increases through the sub-saturating range, the maximum channel activity level is increased without altering the sensitivity or cooperativity of Ca2+ activation and inhibition. Thus the shape of the Ca2+ dependence curve remains essentially unchanged.

In the above mentioned forms of InsP3 and Ca2+ regulation of InsP3R channel activity, changes in channel Po were brought about mainly by changes in the mean duration of channel closings (tc), which can vary over several orders of magnitude in response to changes in [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i, while the mean duration of channel openings (to) remain relatively unaffected by ligand concentrations[36, 50, 57, 61, 65]. This suggests that once an InsP3R channel opens, it will stay open for a stereotypical period of time (to), during which it remains insensitive to changes in [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i, before it closes. This can limit the extent of the negative feed-through effect of the Ca2+ fluxing through an open InsP3R channel to terminate elementary Ca2+ release events.

The last form of InsP3 regulation of InsP3R channel Po is a complex and indirect one. A study of recombinant rat InsP3R-3 and InsP3R-1 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells using nuclear patch clamp techniques [54, 55] reported that exposure to InsP3 induces rapid clustering of InsP3R channels that are normally randomly distributed in the outer nuclear membrane without association with other InsP3R channels. This clustering alters the gating behavior of the channels. Clustered channels have lower sensitivity to InsP3 activation. In saturating [InsP3] but sub-optimal [Ca2+]i, the clustered channels gate independently with identical kinetics, but with Po half that of lone channels. Furthermore, the reduction in channel Po is mainly due to reduction in channel to. In contrast, under optimal ligand conditions (saturating [InsP3] and optimal [Ca2+]i), clustered channels gate with the same overall Po as lone channels, but exhibit coupled gating, i.e., in membrane patches with two active channels, the probabilities that the channels were both open or both closed are higher than predicted for two identical and independent channels. This regulation is controversial. Nuclear patch clamp studies in multiple systems, including recombinant InsP3R-3 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells, have demonstrated that InsP3R channels in the outer nuclear membrane form clusters before exposure to InsP3 [36, 37, 66, 67]. A study of InsP3R-mediated elementary Ca2+ release events (Ca2+ puffs) in intact cells by TIRF microscopy revealed that those events arise from InsP3R channel clusters established before exposure to InsP3, and that the size of the channel clusters does not increase after exposure to InsP3 [68]. Moreover, single-molecule tracking of InsP3R revealed no short-term change in the motility or clustering pattern of InsP3R following activation of the InsP3-Ca2+ signaling pathway [69]. Importantly, channel gating analyses revealed no statistical difference between channel Po in single- and multi-channel records obtained under sub-optimal ligand conditions, and no significant coupled gating behavior in two-channel records obtained under optimal or suboptimal ligand conditions for endogenous channels in Xenopus oocytes and Sf9 cells, and recombinant rat InsP3R-3 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes and DT40-3KO cells [67]. Thus, whether InsP3-induced rapid clustering of InsP3R channels that leads to modification of channel gating is a real or universal phenomenon is very much open to question.

Now that homotetrameric channels of the three InsP3R isoforms have been studied in the same cell system (DT40-3KO), the sensitivity of those channels to InsP3 activation can be compared properly. Comparing the values of the half-maximal [InsP3] (EC50) is complicated by the fact that those InsP3R channels whose sensitivity to Ca2+ inhibition is tuned by [InsP3], like the homotetrameric recombinant InsP3R-3 channel expressed in DT40-3KO cells (Fig. 3D), have different EC50 at different [Ca2+]i. Low [InsP3] (< 1 μM) is sufficient to activate the channel at low [Ca2+]i (< 1 μM), but a much higher [InsP3] (3–10 μM) is required to activate the channel at high [Ca2+]i (> 10 μM) (Fig. 3D). It is much simpler to compare the maximum Po that can be observed at the same sub-saturating [InsP3] for those channels, as suggested in [50]. In 1 μM (sub-saturating) InsP3, the maximum observed Po are 0.27, 0.51 and 0.17 for InsP3R-1, InsP3R-2 and InsP3R-3 channels, respectively. Thus, the InsP3 sensitivity sequence is InsP3R-2 > InsP3R-1 > InsP3R-3, which agrees with the sequence reported for InsP3-binding affinities of the channels [70].

Like the sensitivity of the channels to [Ca2+]i regulation, sensitivity of InsP3R channels to InsP3 activation is affected by factors other than the sequence of the InsP3R. Although recombinant InsP3R-3 channel has the lowest InsP3 sensitivity among the three isoforms expressed in DT40-3KO cells, the same recombinant channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes has a maximum Po of 0.77 in 33 nM InsP3 [61], indicating a much higher InsP3 sensitivity than any of the InsP3R channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells. In fact, the native InsP3R-1 channel in Xenopus oocytes has a similar InsP3 sensitivity with maximum Po of 0.77 in 33 nM InsP3, suggesting that the unknown factor(s) in Xenopus oocytes that enhances the InsP3 sensitivity of InsP3R channels is the dominant effect on channel InsP3 sensitivity.

3.3. Regulation of InsP3R channel gating by [Ca2+]ER

Whereas regulations of InsP3R channel activities by [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i have been well studied, effects of [Ca2+]ER on InsP3R channels remain controversial. In a recent study [57], the rapid perfusion technique was applied in nuclear patch clamp experiments to examine the behaviors of the same InsP3R channels in the same isolated nuclear membrane patches in different [Ca2+]ER. When [Ca2+]ER was switched from 70 nM, a level at which no Ca2+ flux was driven through the InsP3R channel from the luminal side, to 0.3–1.1 mM, levels that generate significant Ca2+ flux, activities of the InsP3R channels were indeed modified (Fig. 4A). However, the nature (activating or inhibitory) and magnitude of the modulation depended not only on [Ca2+]ER (Fig. 4A vs. B), but also on cytoplasmic conditions, including [InsP3] (Fig. 4B vs. C), [Ca2+]i (Fig. 4B vs. D) and Ca2+ buffering capacity (Fig. 4C vs. E). Inhibition and activation of InsP3R channel by [Ca2+]ER were even completely abrogated by strong Ca2+ buffering on the cytoplasmic side together with Vapp that opposed the [Ca2+] gradient to reduce the Ca2+ flux through the channel (Fig. 4F and G).

Fig. 4. Effects of [Ca2+]ER on the gating of homotetrameric InsP3R-3 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells.

Typical current traces from nuclear patch clamp experiments in lum-out configuration under experimental conditions ([InsP3], [Ca2+]i, concentrations of Ca2+ chelator in pipette solutions solution and Vapp) tabulated at top. Color bars at top indicate changes in [Ca2+]ER achieved by rapid perfusion techniques. Blue bars at bottom mark the part of the current traces used to evaluate the channel Po tabulated below. Figures are modified from [57]. For (G), Vapp should be +70 mM.

Taken together, these observations indicate that Ca2+ in the ER lumen modifies InsP3R channel Po not by direct binding to some regulatory site(s) on the luminal side of the InsP3R channel, but by a feed-through effect. Ca2+ driven by high [Ca2+]ER through the open InsP3R channel raises concentration of [Ca2+]i in the vicinity of the channel and binds to the cytoplasmic activating and inhibitory Ca2+ sites to modulate the channel activity [57].

3.4. Graded recruitment of InsP3R channels by favorable ligand conditions

The amount of Ca2+ flux (J) through a patch of ER membrane depends on three factors: the unitary Ca2+ current passing through an open InsP3R channel (iCa), the activity level of the InsP3R channels (Po), and the total number of active channels in the membrane patch (NA). All three factors can be individually measured using nuclear patch clamp electrophysiology. Specifically, NA in an isolated membrane patch is taken to be the maximum number of open-channel current levels observed. To avoid undercounting NA, and therefore overestimating Po, only current records that lasted long enough to ensure a high degree of accuracy (>95% confidence) in determining NA were used for NA and Po evaluation [36, 71]. By counting NA in tens of membrane patches for each of a dozen different combinations of [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i in a nuclear patch clamp study of the endogenous Sf9 InsP3R channel, it was demonstrated that on average, NA observed in the presence of favorable ligand conditions (optimal [Ca2+]i, saturating [InsP3] or both) was significantly higher than that observed in sub-optimal or inhibitory [Ca2+]i, or sub-saturating [InsP3] [36]. However, in that study, it was not certain whether factors other than ligand concentrations that can affect NA, like the tip size of the patch clamp microelectrodes used and the topology of the membrane patch isolated at the tip of the microelectrodes, were sufficiently controlled. Modulation of NA by ligand concentrations was more convincingly demonstrated in a later study that counted NA observed in the same isolated nuclear membrane patch when its cytoplasmic side was exposed to various ligand concentrations. This was done by performing rapid perfusion exchange of the bath solution in nuclear patch clamp experiments in the cyto-out configuration [71]. NA increased incrementally as [Ca2+]i was increased from resting through sub-optimal to optimal levels in saturating [InsP3]. Similarly, more channels were active in saturating [InsP3] than in sub-saturating [InsP3] in the same membrane patch. This was observed for the endogenous InsP3R channels in Sf9 cells, which have only one InsP3R gene. More important, this was also observed for homotetrameric recombinant InsP3R-3 channels expressed in DT40-3KO cells, suggesting that even a homogeneous population of InsP3R channels can exhibit heterogeneous sensitivity to Ca2+i and InsP3 activation. Graded recruitment of InsP3R channel by ligands was completely abrogated by treatment with reducing reagents and restored by treatment with oxidizing reagents, suggesting that the heterogeneous ligand sensitivity is regulated largely by post-transcriptional redox modulation of the channels.

In a population of InsP3R channels with heterogeneous sensitivities to ligands, those channels with higher ligand sensitivity may act as “hot spots” to initiate fundamental Ca2+-release events (blips) [72] as [InsP3] starts to rise in response to extracellular stimuli. The rise in [Ca2+]i not only enhances the activities of the InsP3R channels that are already activated, but also recruits more InsP3R channels with lower [Ca2+]i sensitivities to further amplify the magnitude of the Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release to propagate the Ca2+ signal. Thus, graded recruitment of InsP3R channels with favorable ligand conditions can be an important mechanism in both the generation and propagation of intracellular Ca2+ signals.

3.5. Ligand regulation of modal gating behaviors of InsP3R channels

In some experimental systems for nuclear patch clamping, like the native Sf9 InsP3R and recombinant InsP3R expressed in DT40-3KO cells, the activity of individual InsP3R channels can be stably recorded for extensive periods (tens of minutes) [71, 73]. Examination of such long single-channel records of Sf9 InsP3R revealed that even under constant ligand conditions ([InsP3] and [Ca2+]i), channels exhibited relatively occasional (one to two orders of magnitude less frequent than channel gating), spontaneous and abrupt transitions among three distinct gating patterns (modes) (Fig. 5A): a low-activity (L) mode with long channel closings and brief channel openings (Po = 0.007), an intermediate (I) mode with rapid channel gating kinetics (Po = 0.24), and a high-activity (H) mode with prolonged bursts of channel activity (Po = 0.85)[73]. These modes were observed under all ligand conditions and remarkably, channel gating kinetics within a mode were not significantly altered by [Ca2+]i and [InsP3] (Fig. 5B). Thus, the graded dependencies of InsP3R channel Po on [Ca2+]i and [InsP3] of various InsP3R channels (Fig. 3B–D) is mostly the result of continuous shifting of the relative probabilities of the channel being in these modes, especially the L and H modes (Fig. 5C) as the ligand concentrations vary. Interestingly, only the mean duration of the H mode was significantly affected by ligand concentrations, while those of the L and I modes remained within a narrow range for the [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i examined. The ligand independence of the long mean duration of the L mode (〈τL〉) suggests that once a channel enters the L mode, it becomes insensitive to [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i, and will remain in the L mode with very low for a stereotypical long duration ~〈τL〉. This may be one of the mechanisms to terminate an InsP3R-mediated Ca2+ release event (puff), especially when the local cytoplasmic ligand conditions are not optimal so the channels have high probability of entering the L mode.

Fig. 5. Modal gating behaviors of endogenous insect Sf9 InsP3R.

(A) Black traces are baseline-subtracted current records obtained in saturating 10 μM InsP3, with sub-optimal (100 nM), optimal (1 μM) and inhibitory (89 μM) [Ca2+]i, as tabulated. Blue and purple traces are idealized gating records before and after burst analysis, respectively, derived from the corresponding current records. Color bars at bottom indicate the gating mode the InsP3R channel was in during the shown records (red, orange and green for L, I and H modes, respectively). (B) Channel open probability in each of the three modes (PoM), (C) probability of the channel being in each of the three modes (πM), and (D) mean durations 〈τM〉 of each of the three modes observed are plotted against the ligand concentrations in which they were observed. Note the non-linear y-axis used in (B) to better show the low PoL values for the L mode, and the logarithmic scale used in (D). In (B-D), the top x-axis labels indicate the cytoplasmic free calcium concentrations, the bottom labels indicate the cytoplasmic InsP3 concentrations. Figure modified from [12] and [73].

Subsequently, such modal behaviors have also been observed for endogenous InsP3R channels from human lymphoblasts, mouse embryonic fibroblasts and mouse primary embryonic cortical neurons [48]. In these channels, modal switching is not only the major mechanism for physiological ligand regulation of InsP3R channel activities, but is also the mechanism behind the pathogenic dysregulation of InsP3R channel by familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked mutant presenilins. Interaction between the mutant presenilins and InsP3R channels greatly increases the propensity of InsP3R channels being in the H mode, thereby causing exaggerated Ca2+ release through those channels [48].

Recently, modal gating was observed in recombinant rat InsP3R-1 S2+ and mouse InsP3R-2 expressed in DT40-3KO cells [50]. Both channels exhibit two gating modes: a “park” mode in which the channels only open briefly and very occasionally (Po < 0.01) and a “drive” mode with bursting channel activities (Po = 0.64) [74]. Within a mode, channel gating kinetics are practically the same in all [Ca2+]i, [InsP3] and [ATP4−]. In InsP3R-1 channel, more favorable [Ca2+]i both prolongs the drive mode duration and shortens the park mode duration; more favorable [InsP3] mainly shortens the park mode duration and lengthens the drive mode to a smaller extent; and increase in [ATP4−] shifts the effects of [Ca2+]i on the modal durations towards lower [Ca2+]i levels. Ligand regulation of model behaviors of InsP3R-2 channel is more complicated. In saturating [InsP3], [ATP4−] does not affect durations of the modes and favorable [Ca2+]i lengthens drive mode duration and shortens park mode duration as in InsP3R-1. At low [InsP3] and saturating [ATP4−], more favorable [Ca2+]i only shorten the park mode duration but do not change the drive mode duration. When both [InsP3] and [ATP4−] are low, the channel has low Po with long park mode duration and short drive mode duration over most [Ca2+]i; and drive mode duration is further reduced and park mode duration is further lengthened at extreme [Ca2+]i. The insensitivity of the mean duration of the L/park mode to ligand conditions observed in the insect Sf9 InsP3R channel was not observed in the mammalian homotetrameric InsP3R-1 or InsP3R-2 channels. The durations of both the park and drive modes are affected by [InsP3], [Ca2+]i and [ATP4−] in most ligand conditions. Thus, unlike the case for Sf9 InsP3R channels, modal gating kinetics probably does not play a significant role in the termination of InsP3R-mediated intracellular Ca2+ release events involving these channels.

Because of the consistency of the Po of the InsP3R channel within a gating mode over a broad range of ligand conditions (Fig. 5B and [50]), modal gating behavior of the InsP3R channels offers a way to greatly simplify the modeling of Ca2+ release through these channels. The gating kinetics (opening and closing) of the channels within a mode can be ignored. An InsP3R channel in one gating mode can be considered as a channel in a conductance substate with Ca2+ conductance of (iCa)(PoM), where PoM is the Po of the channel in that gating mode. The kinetics of the transition of the channel among the conductance substates is the kinetics of the modal transitions of the channel, which is significantly slower than the gating kinetics of the channel and therefore simpler to simulate.

3.6. Ligand regulations of heterotetrameric InsP3R channels of known isoform composition

Although most cell types examined express, at various levels, multiple isoforms of InsP3R [31, 75], which can form heterotetrameric channels [11], there has been no experimental technique to study the properties of individual heterotetrameric InsP3R channels with known isoform composition until recently. The exciting technological break-through of expressing concatenated InsP3R dimers in DT40-3KO cells to form properly localized and functional InsP3R channels enables the study of the properties of heterotetrameric InsP3R channels of a specific isoform composition [76]. In the pioneering study, on-nucleus patch clamp experiments demonstrated that the conductance of InsP3R channels formed by concatenated InsP3R-1:InsP3R-1 (R1R1) dimers is identical to that of homotetrameric InsP3R-1 channels. Furthermore, the gating and modal behaviors, and their regulation by [InsP3] and [ATP4−] at 200 nM [Ca2+]i of channels formed by R1R1 dimers resembled those of homotetrameric InsP3R-1 channels, and those of channels formed by concatenated R2R2 dimers resembled those of homotetrameric InsP3R-2 channels. Remarkably, those single-channel properties of channels formed by concatenated R1R2 dimers were indistinguishable from those of homotetrameric InsP3R-2 channels, suggesting that InsP3R-2 dominates over InsP3R-1 in determining the gating properties of a heterotetrameric channel formed by the two. Characterizing the conductance and gating properties of heterotetrameric InsP3R channels with known isoform composition can provide valuable insights into the physiological reasons behind the sequence diversity of the channel and the intricate regulation of the expression levels of InsP3R with different sequences [11].

4. Dynamic responses of InsP3R channel to rapid changes in ligand concentrations

Although studying InsP3R gating properties in constant [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i has provided much insight into ligand regulation of InsP3R channels, [Ca2+]i, and to a lesser extent [InsP3], change dynamically during Ca2+ signaling events. Therefore, to get a better understanding of how InsP3R channels function and contribute to intracellular Ca2+ signaling, it is essential to study the behaviors of InsP3R channels under non-steady ligand conditions.

The kinetic responses of single Sf9 InsP3R channels to abrupt changes in ligand concentrations were examined with millisecond resolution by applying rapid perfusion techniques to cyto-out nuclear membrane patches [77]. This study provided the first and, to date, the only measurements of the lag times of InsP3 activation and deactivation (Fig. 6A and B), Ca2+ activation and deactivation (Fig. 6C and D), activation and deactivation by simultaneous changes in [Ca2+]i and [InsP3] (Fig. 6E and F), Ca2+ inhibition and recovery from inhibition (Fig. 6G and I), and the durations of fundamental single-channel Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release events (Fig. 6J). While the majority of [Ca2+]i jumps from < 10 nM to 300 μM in 10 μM InsP3 activated Ca2+ release bursts (Fig. 6J), a non-trivial fraction of the jumps failed to activate any burst due to Ca2+ binding to the inhibitory sites of the channel before the activating sites got occupied. This showed that Ca2+ binding to those sites are non-sequential. Similarly, in some of the [Ca2+]i drops from 300 μM to < 10 nM, the channel recovered from Ca2+ inhibition before Ca2+ unbound from its activating site, generating a brief burst of channel activity (Fig. 6K), showing Ca2+ unbinding from the activating and inhibitory sites are also non-sequential. The study also clearly demonstrated the absence of long-term adaptation [78] behaviors in InsP3R channels following changes in [InsP3] or [Ca2+]i (Fig. 6L and M, respectively). The surprisingly long times InsP3R channels took to recovery from Ca2+ inhibition (Fig. 6I) suggest that this may contribute significantly to the refractory interval between consecutive Ca2+ release from the same site in the ER [79]. The lag times for channel activation by [InsP3] jumps from 0 to 100 μM were only modestly shorter than those for [InsP3] jumps from 0 to 10 μM (Fig. 6H vs. A), indicating that InsP3 binding to the channel, and the subsequent conformation changes that lead to the channel arriving at its open conformation(s) both contribute significantly to the InsP3 activation lag times. In contrast, the lag times for channel activation by [Ca2+]i jumps from < 10 nM to 300 μM were substantially shorter than those for [Ca2+]i jumps from < 10 nM to 2 μM (Fig. 6J vs. C), suggesting that Ca2+ binding to the channel is the major contribution to the Ca2+ activation lag times. Furthermore, the study revealed an unexpected cooperativity between Ca2+ and InsP3 modulation of the channel: in the absence of InsP3, Ca2+ binding to an InsP3R channel stabilizes it in a closed conformation so that a jump in [InsP3] in the constant presence of high (2 μM) [Ca2+]i takes significantly longer to activate the channel than when [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i are increased simultaneously (Fig. 6A vs. E). On the other hand, in the presence of InsP3, Ca2+ binding to an InsP3R channel stabilizes it in an open conformation so that decreases in [InsP3] in the constant presence of 2 μM [Ca2+]i take longer to deactivate the channel than when both [InsP3] and [Ca2+]i are dropped simultaneously (Fig. 6B vs. F). The mean duration of the L mode of the Sf9 channel (Fig. 5D) is substantially longer than the lag times of activation of the channel by abrupt jumps in [InsP3] (Fig. 6A), or in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 6C), or in both [Ca2+]i and [InsP3] (Fig. 6E). This suggests that the channel has a complex kinetic gating scheme with the channel in distinct closed kinetic states depending on the occupancies of its activating Ca2+ and InsP3 binding sites. These different closed kinetic states are connected to different open kinetic states, as described in [80]. Thus, when the channel is activated by jumps in [InsP3] or [Ca2+]i, it is exiting from closed kinetic states that are different from the closed kinetic state(s) involved when the channel transits from the L to the I or H modes, with different transition kinetics.

Fig. 6. Dynamic responses of endogenous insect Sf9 InsP3R to abrupt changes in [Ca2+]i and [InsP3] observed in cyto-out nuclear patch clamp experiments.

Color bars at top indicate changes in [Ca2+]i and [InsP3] achieved by rapid exchange of bath solutions. Times when such exchanges occurred were marked by changes in closed-channel current levels due to difference in [KCl] (100 mM vs. 70 mM) in the bath solutions used. Gray bars at bottom indicate the lag times between ligand concentration switches and the resulting changes in InsP3R channel gating behaviors. Two arrows indicate the closed-channel current levels before and after the bath solution switches for each current traces. In (J), the dark gray bar indicates the Ca2+ activation lag time and the light gray bar indicates the Ca2+ inhibition lag time. Note that a different time scale is used for (L) and (M). Figure modified from [77].

5. Moving forward

The InsP3R channel is unusual in that even its fundamental properties: single-channel conductance and regulation by InsP3 and Ca2+, are apparently very mutable. Not only are the sensitivities and degrees of cooperativity of ligand regulation different among channels of different isoforms, but also the ways InsP3 regulates those different channels are fundamentally different. Even the conductance and the sensitivity to InsP3 activation of the same recombinant homotetrameric channel expressed in different cells can be radically different. Therefore due caution should be exercised when attempting to extrapolate single InsP3R channel properties observed in one experimental system to another system. It is advisable to characterize the basic properties: conductance and [Ca2+]i and [InsP3] dependencies, of InsP3R channels in a new experimental system, using buffer solutions with commonly used physiological compositions (140–150 mM KCl, 0.5 mM ATP4− and pH 7.3) for easier comparison with previous studies.

The recent development of the capability of expressing concatenated InsP3R dimers to form functional InsP3R channels in DT40-3KO cells [76] offers the opportunity to study heterotetrameric InsP3R channels with known isoform compositions. That study also demonstrated that concatenated InsP3R tetramers could also be expressed in DT40-3KO cells, though in significantly lower levels than concatenated dimers. If the expression of concatenated tetramers can be enhanced, then properties of channels formed by all three InsP3R isoforms, like R1R2R3R1, and channels with asymmetric isoform compositions, like R1R1R1R2, can be studied and compared with properties of native InsP3R channels in various cells to shed light on the physiological significance of the molecular diversity of the InsP3R.

Many computational kinetic models have been developed over the years to account for the observed InsP3 and Ca2+i regulation of single InsP3R channel gating ([81] and references therein). These kinetic models were then used to simulate the generation and propagation of more complex intracellular Ca2+ signals (blips, puffs and waves) by organized clusters of InsP3R channels [72]. Even though recent experiments demonstrated that modulation of modal switching is the main mechanism for steady-state ligand regulation of InsP3R channel activities [50, 73], only a few models have been developed to account for InsP3R modal behaviors [74, 80]. Furthermore, the roles of modal behaviors in the dynamic responses of InsP3R channel to changes in [InsP3] and more importantly [Ca2+]i have barely been investigated [80]. Much work needs to be done to develop kinetic models that can adequately describe the complex gating behaviors of single InsP3R channels to enable proper simulation of organized gating of multiple InsP3 channels to generate local and global Ca2+ release events.

Highlights.

InsP3R single-channel properties studied by nuclear patch clamping are reviewed

We examine InsP3R K+ conductance and unitary Ca2+ current in physiological solutions

Steady-state Ca2+ and InsP3 dependencies of channels of various isoforms are compared

Ligand-regulated modal gating and graded recruitment of InsP3R channels are examined

Responses of InsP3R channels to abrupt ligand concentration changes are presented

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants MH059937 to J.K. Foskett and GM065830 to D.-O.D. Mak.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Putney JW, Jr, Bird GS. The inositol phosphate-calcium signaling system in nonexcitable cells. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:610–631. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-5-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 1993;361:315–325. doi: 10.1038/361315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Streb H, Irvine RF, Berridge MJ, Schulz I. Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983;306:67–69. doi: 10.1038/306067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedorenko OA, Popugaeva E, Enomoto M, Stathopulos PB, Ikura M, Bezprozvanny I. Intracellular calcium channels: Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;739C:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.10.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludtke SJ, Serysheva II. Single-particle cryo-EM of calcium release channels: structural validation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boehning DF. Molecular architecture of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor pore. Curr Top Membr. 2010;66C:191–207. doi: 10.1016/S1063-5823(10)66009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor CW, Tovey SC, Rossi AM, Lopez Sanjurjo CI, Prole DL, Rahman T. Structural organization of signalling to and from IP3 receptors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42:63–70. doi: 10.1042/BST20130205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betzenhauser MJ, Yule DI. Regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors by phosphorylation and adenine nucleotides. Curr Top Membr. 2010;66C:273–298. doi: 10.1016/S1063-5823(10)66012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paula-Lima AC, Adasme T, Hidalgo C. Contribution of Ca Release Channels to Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity and Spatial Memory: Potential Redox Modulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014 doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph SK. Role of thiols in the structure and function of inositol trisphosphate receptors. Curr Top Membr. 2010;66C:299–322. doi: 10.1016/S1063-5823(10)66013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foskett JK, White C, Cheung KH, Mak D-OD. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:593–658. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foskett JK, Mak D-OD. Regulation of IP3R channel gating by Ca2+ and Ca2+ binding proteins. In: Serysheva II, editor. Curr Top Membr Vol 66: Structure-Function of Ca2+ release channels. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 235–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehrlich BE, Watras J. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate activates a channel from smooth muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Nature. 1988;336:583–586. doi: 10.1038/336583a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montal M, Mueller P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mak D-OD, Foskett JK. Single-channel inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor currents revealed by patch clamp of isolated Xenopus oocyte nuclei. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29375–29378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stehno-Bittel L, Luckhoff A, Clapham DE. Calcium release from the nucleus by InsP3 receptor channels. Neuron. 1995;14:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dingwall C, Laskey R. The nuclear membrane. Science. 1992;258:942–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1439805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicotera P, McConkey DJ, Jones DP, Orrenius S. ATP stimulates Ca2+ uptake and increases the free Ca2+ concentration in isolated rat liver nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:453–457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mak DO, Vais H, Cheung KH, Foskett JK. Patch-clamp electrophysiology of intracellular Ca2+ channels. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2013;2013:787–797. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top066217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchenko SM, Yarotskyy VV, Kovalenko TN, Kostyuk PG, Thomas RC. Spontaneously active and InsP3-activated ion channels in cell nuclei from rat cerebellar Purkinje and granule neurones. J Physiol. 2005;565:897–910. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mak DO, Vais H, Cheung KH, Foskett JK. Isolating nuclei from cultured cells for patch-clamp electrophysiology of intracellular Ca2+ channels. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2013;2013:880–884. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot073056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedorenko OA, Marchenko SM. Ion channels of the nuclear membrane of hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus. 2014;24:869–876. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellis O, Dedos SG, Tovey SC, Taufiq Ur R, Dubel SJ, Taylor CW. Ca2+ entry through plasma membrane IP3 receptors. Science. 2006;313:229–233. doi: 10.1126/science.1125203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dellis O, Rossi AM, Dedos SG, Taylor CW. Counting functional inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors into the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:751–755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schug ZT, da Fonseca PC, Bhanumathy CD, Wagner L, 2nd, Zhang X, Bailey B, et al. Molecular characterization of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor pore-forming segment. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2939–2948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Betzenhauser MJ, Wagner LE, 2nd, Iwai M, Michikawa T, Mikoshiba K, Yule DI. ATP modulation of Ca2+ release by type-2 and type-3 inositol (1, 4, 5)-triphosphate receptors. Differing ATP sensitivities and molecular determinants of action. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21579–21587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801680200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner LE, 2nd, Joseph SK, Yule DI. Regulation of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channel activity by protein kinase A phosphorylation. J Physiol. 2008;586:3577–3596. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.152314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gin E, Falcke M, Wagner LE, 2nd, Yule DI, Sneyd J. A kinetic model of the inositol trisphosphate receptor based on single-channel data. Biophys J. 2009;96:4053–4062. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betzenhauser MJ, Fike JL, Wagner LE, 2nd, Yule DI. Protein kinase A increases type-2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor activity by phosphorylation of serine 937. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25116–25125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith IF, Parker I. Imaging the quantal substructure of single IP3R channel activity during Ca2+ puffs in intact mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6404–6409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810799106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor CW, Genazzani AA, Morris SA. Expression of inositol trisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium. 1999;26:237–251. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE. Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature. 1991;351:751–754. doi: 10.1038/351751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parys JB, Sernett SW, DeLisle S, Snyder PM, Welsh MJ, Campbell KP. Isolation, characterization, and localization of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor protein in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18776–18782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos-Franco J, Fill M, Mignery GA. Isoform-specific function of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channels. Biophys J. 1998;75:834–839. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77572-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagar RE, Burgstahler AD, Nathanson MH, Ehrlich BE. Type III InsP3 receptor channel stays open in the presence of increased calcium. Nature. 1998;396:81–84. doi: 10.1038/23954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ionescu L, Cheung KH, Vais H, Mak D-OD, White C, Foskett JK. Graded recruitment and inactivation of single InsP3 receptor Ca2+-release channels: implications for quantal Ca2+ release. J Physiol. 2006;573:645–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mak D-OD, McBride S, Raghuram V, Yue Y, Joseph SK, Foskett JK. Single-channel properties in endoplasmic reticulum membrane of recombinant type 3 inositol trisphosphate receptor. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:241–256. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.3.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramos-Franco J, Caenepeel S, Fill M, Mignery G. Single channel function of recombinant type-1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor ligand binding domain splice variants. Biophys J. 1998;75:2783–2793. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77721-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boehning D, Joseph SK, Mak D-OD, Foskett JK. Single-channel recordings of recombinant inositol trisphosphate receptors in mammalian nuclear envelope. Biophys J. 2001;81:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(01)75685-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang TS, Tu H, Wang Z, Bezprozvanny I. Modulation of type 1 inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor function by protein kinase A and protein phosphatase 1α. J Neurosci. 2003;23:403–415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00403.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugawara H, Kurosaki M, Takata M, Kurosaki T. Genetic evidence for involvement of type 1, type 2 and type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in signal transduction through the B-cell antigen receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16:3078–3088. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mak D-OD, White C, Ionescu L, Foskett JK. Nuclear patch clamp electrophysiology of inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. In: Putney JW Jr, editor. Calcium Signaling. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. pp. 203–229. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen DP, Xu LEB, Meissner G. Calcium ion permeation through the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) of cardiac muscle. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:9139–9145. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gillespie D. Energetics of divalent selectivity in a calcium channel: the ryanodine receptor case study. Biophys J. 2008;94:1169–1184. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.116798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bezprozvanny I, Ehrlich BE. Inositol (1,4,5)-trisphosphate (InsP3)-gated Ca channels from cerebellum: conduction properties for divalent cations and regulation by intraluminal calcium. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:821–856. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.5.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perez PJ, Ramos-Franco J, Fill M, Mignery GA. Identification and functional reconstitution of the type 2 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor from ventricular cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23961–23969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mak D-OD, Foskett JK. Effects of divalent cations on single-channel conduction properties of Xenopus IP3 receptor. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C179–188. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.1.C179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheung KH, Mei L, Mak D-OD, Hayashi I, Iwatsubo T, Kang DE, et al. Gain-of-function enhancement of IP3 receptor modal gating by familial Alzheimer’s disease-linked presenilin mutants in human cells and mouse neurons. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra22. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Betzenhauser MJ, Wagner LE, 2nd, Park HS, Yule DI. ATP regulation of type-1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor activity does not require walker A-type ATP-binding motifs. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16156–16163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner LE, Yule DI. Differential regulation of the InsP3 receptor type-1 and -2 single channel properties by InsP3,Ca2+ and ATP. J Physiol. 2012;590:3245–3259. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.228320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yule DI, Betzenhauser MJ, Joseph SK. Linking structure to function: Recent lessons from inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor mutagenesis. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vais H, Foskett JK, Mak D-OD. Unitary Ca2+ current through recombinant type 3 InsP3 receptor channels under physiological ionic conditions. J Gen Physiol. 2010;136:687–700. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossi AM, Riley AM, Tovey SC, Rahman T, Dellis O, Taylor EJ, et al. Synthetic partial agonists reveal key steps in IP3 receptor activation. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman T, Taylor CW. Dynamic regulation of IP3 receptor clustering and activity by IP3. Channels (Austin) 2009;3:226–232. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.4.9247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rahman T, Skupin A, Falcke M, Taylor CW. Clustering of InsP3 receptors by InsP3 retunes their regulation by InsP3 and Ca2+ Nature. 2009;458:655–659. doi: 10.1038/nature07763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gillespie D, Fill M. Intracellular calcium release channels mediate their own countercurrent: the ryanodine receptor case study. Biophys J. 2008;95:3706–3714. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vais H, Foskett JK, Ullah G, Pearson JE, Mak D-OD. Permeant calcium ion feed-through regulation of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor channel gating. J Gen Physiol. 2012;140:697–716. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rudiger S, Nagaiah C, Warnecke G, Shuai JW. Calcium domains around single and clustered IP3 receptors and their modulation by buffers. Biophys J. 2010;99:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shuai J, Pearson JE, Parker I. Modeling Ca2+ feedback on a single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and its modulation by Ca2+ buffers. Biophys J. 2008;95:3738–3752. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.137182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berridge MJ. Elementary and global aspects of calcium signalling. J Physiol. 1997;499:291–306. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mak D-OD, McBride S, Foskett JK. Regulation by Ca2+ and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) of single recombinant type 3 InsP3 receptor channels. Ca2+ activation uniquely distinguishes types 1 and 3 InsP3 receptors. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:435–446. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.5.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mak D-OD, McBride SM, Petrenko NB, Foskett JK. Novel regulation of calcium inhibition of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor calcium-release channel. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:569–581. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mak D-OD, McBride S, Foskett JK. ATP regulation of recombinant type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor gating. J Gen Physiol. 2001;117:447–456. doi: 10.1085/jgp.117.5.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaftan EJ, Ehrlich BE, Watras J. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) and calcium interact to increase the dynamic range of InsP3 receptor-dependent calcium signaling. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:529–538. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.5.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mak D-OD, McBride S, Foskett JK. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate activation of inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ channel by ligand tuning of Ca2+ inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15821–15825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mak D-OD, Foskett JK. Single-channel kinetics, inactivation, and spatial distribution of inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptors in Xenopus oocyte nucleus. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:571–587. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.5.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vais H, Foskett JK, Mak D-OD. InsP3R channel gating altered by clustering? Nature. 2011;478:E1–2. doi: 10.1038/nature10493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith IF, Wiltgen SM, Shuai J, Parker I. Ca2+ puffs originate from preestablished stable clusters of inositol trisphosphate receptors. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra77. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith IF, Swaminathan D, Dickinson GD, Parker I. Single-molecule tracking of inositol trisphosphate receptors reveals different motilities and distributions. Biophys J. 2014;107:834–845. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Iwai M, Michikawa T, Bosanac I, Ikura M, Mikoshiba K. Molecular basis of the isoform-specific ligand-binding affinity of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12755–12764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vais H, Siebert AP, Ma Z, Fernandez-Mongil M, Foskett JK, Mak D-OD. Redox-regulated heterogeneous thresholds for ligand recruitment among InsP3R Ca2+ release channels. Biophys J. 2010;99:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lipp P, Niggli E. A hierarchical concept of cellular and subcellular Ca2+-signalling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1996;65:265–296. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(96)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ionescu L, White C, Cheung KH, Shuai J, Parker I, Pearson JE, et al. Mode switching is the major mechanism of ligand regulation of InsP3 receptor calcium release channels. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:631–645. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Siekmann I, Wagner LE, 2nd, Yule D, Crampin EJ, Sneyd J. A Kinetic Model for Type I and II IP3R Accounting for Mode Changes. Biophys J. 2012;103:658–668. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wojcikiewicz RJ. Type I, II, and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are unequally susceptible to down-regulation and are expressed in markedly different proportions in different cell types. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11678–11683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alzayady KJ, Wagner LE, 2nd, Chandrasekhar R, Monteagudo A, Godiska R, Tall GG, et al. Functional inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors assembled from concatenated homo-and heteromeric subunits. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:29772–29784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.502203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mak D-OD, Pearson JE, Loong KPC, Datta S, Fernández-Mongil M, Foskett JK. Rapid ligand-regulated gating kinetics of single inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:1044–1051. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Muallem S, Pandol SJ, Beeker TG. Hormone-evoked calcium release from intracellular stores is a quantal process. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ilyin V, Parker I. Role of cytosolic Ca2+ in inhibition of InsP3-evoked Ca2+ release in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1994;477:503–509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]