HHIP1 acts as a secreted Hedgehog antagonist whose association with heparan sulfate–containing basement membranes regulates Hedgehog ligand distribution.

Abstract

Vertebrate Hedgehog (HH) signaling is controlled by several ligand-binding antagonists including Patched-1 (PTCH1), PTCH2, and HH-interacting protein 1 (HHIP1), whose collective action is essential for proper HH pathway activity. However, the molecular mechanisms used by these inhibitors remain poorly understood. In this paper, we investigated the mechanisms underlying HHIP1 antagonism of HH signaling. Strikingly, we found evidence that HHIP1 non–cell-autonomously inhibits HH-dependent neural progenitor patterning and proliferation. Furthermore, this non–cell-autonomous antagonism of HH signaling results from the secretion of HHIP1 that is modulated by cell type–specific interactions with heparan sulfate (HS). These interactions are mediated by an HS-binding motif in the cysteine-rich domain of HHIP1 that is required for its localization to the neuroepithelial basement membrane (BM) to effectively antagonize HH pathway function. Our data also suggest that endogenous, secreted HHIP1 localization to HS-containing BMs regulates HH ligand distribution. Overall, the secreted activity of HHIP1 represents a novel mechanism to regulate HH ligand localization and function during embryogenesis.

Introduction

Hedgehog (HH) signaling is indispensable for embryogenesis (McMahon et al., 2003). Secreted HH ligands act over long distances to produce distinct cellular responses, depending on both the concentration and duration of HH ligand exposure (Martí et al., 1995; Ericson et al., 1997; McMahon et al., 2003; Dessaud et al., 2007). HH pathway activity is tightly controlled by complex feedback mechanisms involving a diverse array of cell surface–associated ligand-binding proteins, including the HH co-receptors GAS1, CDON, and BOC and the HH pathway antagonists Patched-1 (PTCH1), PTCH2, and HH-interacting protein-1 (HHIP1; Jeong and McMahon, 2005; Tenzen et al., 2006; Beachy et al., 2010; Allen et al., 2011; Holtz et al., 2013). These molecules constitute a complex feedback network that controls the magnitude and range of HH signaling (Chen and Struhl, 1996; Milenkovic et al., 1999; Jeong and McMahon, 2005; Tenzen et al., 2006; Allen et al., 2007; Holtz et al., 2013).

The canonical HH receptor Patched (PTC in Drosophila melanogaster; PTCH1 in vertebrates) is a direct transcriptional HH pathway target (Forbes et al., 1993; Alexandre et al., 1996; Goodrich et al., 1996; Ågren et al., 2004; Vokes et al., 2007). In Drosophila, PTC accumulation at the cell surface binds and sequesters HH ligands, limiting signaling in cells distal to the HH source (Chen and Struhl, 1996). In vertebrates, HH-dependent patterning requires not only PTCH1, but two additional, vertebrate-specific feedback antagonists: the PTCH1 homologue, PTCH2, and HHIP1 (Motoyama et al., 1998; Carpenter et al., 1998; Chuang and McMahon, 1999; Koudijs et al., 2005, 2008). PTCH1 and PTCH2 act redundantly in multiple cells and tissues, including the developing skin (Adolphe et al., 2014; Alfaro et al., 2014). However, HH-dependent ventral neural patterning is severely disrupted after the combined removal of PTCH2, HHIP1, and PTCH1 feedback inhibition (Milenkovic et al., 1999; Jeong and McMahon, 2005; Holtz et al., 2013). These data suggest that PTCH1, PTCH2, and HHIP1 play overlapping and essential roles to limit HH ligand signaling during embryonic development.

Although PTCH2 and HHIP1 perform overlapping functions with PTCH1 in the developing nervous system, they exhibit distinct requirements in different tissues. For example, Ptch2−/− mice are viable and fertile, yet aged adult males develop significant alopecia and epidermal hyperplasia (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2006). Additionally, Hhip1−/− mice die at birth as a result of severe defects in lung branching morphogenesis that results from unrestrained HH pathway activity in the developing lung mesenchyme (Chuang et al., 2003). Despite Ptch1 and Ptch2 expression in the embryonic lung (Bellusci et al., 1997b; Pepicelli et al., 1998), these molecules fail to compensate for the absence of HHIP1 as occurs during ventral neural patterning. Moreover, Hhip1−/− embryos display developmental defects in the pancreas, spleen, and duodenum (Kawahira et al., 2003). These observations argue that PTCH2 and HHIP1 are not simply redundant with PTCH1 but that they perform distinct functions to fulfill essential, tissue-specific roles within the vertebrate lineage. However, the mechanisms that account for these nonredundant activities, especially with regard to HHIP1, remain largely unknown.

Hhip1 is a direct transcriptional HH pathway target that encodes for a cell surface–associated protein, which binds all three mammalian HH ligands with high affinity (Chuang and McMahon, 1999; Pathi et al., 2001; Vokes et al., 2007; Bishop et al., 2009; Bosanac et al., 2009). HHIP1 possesses several conserved functional domains including an N-terminal cysteine-rich domain (CRD), a six-bladed β-propeller region, two membrane-proximal EGF repeats, and a C-terminal hydrophobic motif (Chuang and McMahon, 1999). Crystallographic studies identified the β-propeller domain of HHIP1 as the HH ligand–binding domain (Bishop et al., 2009; Bosanac et al., 2009). HHIP1 is proposed to act as a membrane-bound competitive inhibitor of HH signaling (Chuang and McMahon, 1999; Bishop et al., 2009); however, both PTCH1 and PTCH2 share this activity. Thus, the molecular features that distinguish HHIP1 from PTCH1 and PTCH2 have yet to be discerned.

Here, we investigate the molecular mechanisms of HHIP1 function in HH pathway inhibition. Strikingly, we find that, in contrast to PTCH1 and PTCH2, HHIP1 uniquely induces non–cell-autonomous inhibition of HH-dependent neural progenitor patterning and proliferation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that HHIP1 secretion underlies these long-range effects. Using biochemical approaches, we define HHIP1 as a secreted HH antagonist that is retained at the cell surface through cell type–specific interactions between heparan sulfate (HS) and the N-terminal CRD of HHIP1. Importantly, we show that HS binding promotes long-range HH pathway inhibition by localizing HHIP1 to the neuroepithelial basement membrane (BM). Finally, we demonstrate that endogenous HHIP1 is a secreted protein whose association with HS-containing BMs regulates HH ligand distribution. Overall, these data redefine HHIP1 as a secreted, HS-binding HH pathway antagonist that utilizes a novel and distinct mechanism to restrict HH ligand function.

Results

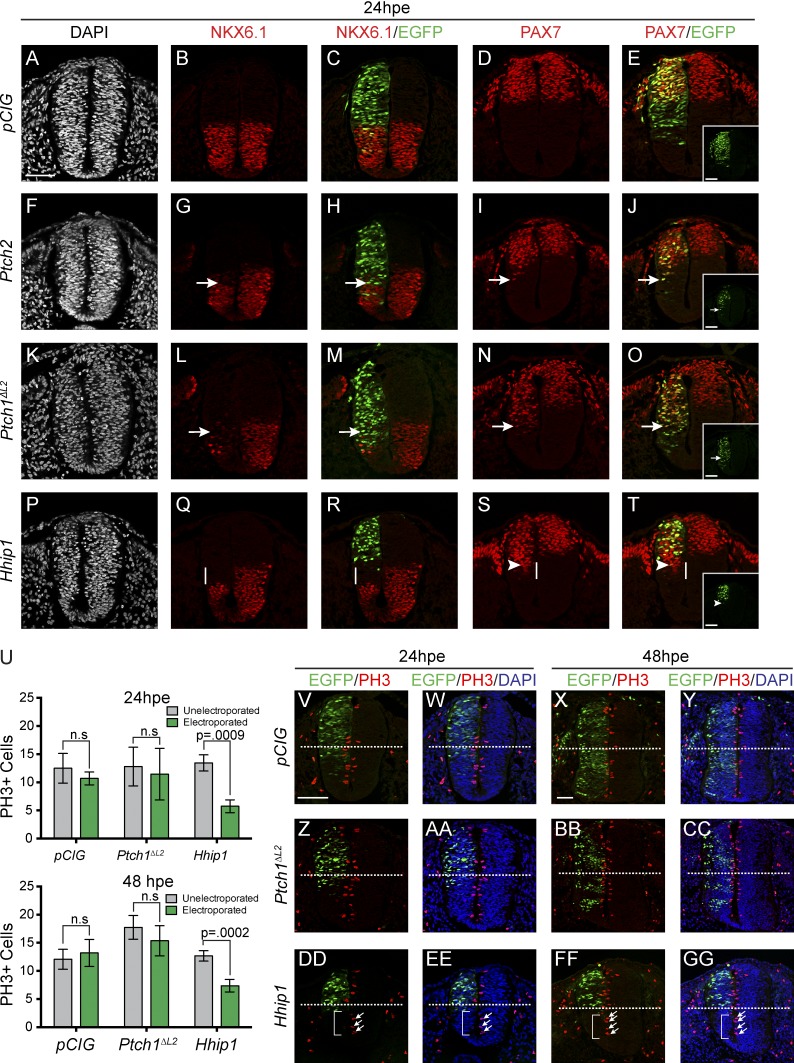

HHIP1 non–cell-autonomously inhibits HH-dependent neural progenitor specification

To interrogate PTCH1-, PTCH2- and HHIP1-mediated antagonism of HH signal transduction, we used a gain-of-function approach in the developing chicken neural tube to investigate their effects on HH-dependent ventral neural patterning (Fig. 1). Nuclear EGFP expression from a bicistronic IRES-EGFPNLS construct (pCIG) labels electroporated cells, providing spatial resolution when analyzing the effects of a given protein on HH-dependent neural patterning. Expression of EGFP alone (pCIG) does not affect neural patterning as assessed by antibody detection of the positive HH target NKX6.1 and the negative HH target PAX7 (Fig. 1, A–E) in embryos collected 24 h postelectroporation (24 hpe). Similar to previous results, electroporation of Ptch2 or Ptch1ΔL2, a ligand-insensitive construct that functions as a constitute repressor (Briscoe et al., 2001), results in cell-autonomous loss of NKX6.1 (Fig. 1, F–H and K–M, arrows) and ectopic PAX7 expression (Fig. 1, I, J, N, and O, arrows), indicative of reduced HH signaling (Holtz et al., 2013). Hhip1 electroporation also represses NKX6.1 expression in ventral progenitors (Fig. 1, P–R) and induces ectopic PAX7 expression (Fig. 1, S and T) at 24 hpe. Strikingly, these effects arise non–cell autonomously; most ventral progenitors that lose NKX6.1 expression are not EGFP+ (Fig. 1, P–R, white lines). Additionally, many ectopic PAX7+ cells do not coexpress EGFP and are found ventral to the EGFP+, HHIP1-expressing cells (Fig. 1, S and T, arrowheads). This contrasts with the strictly cell-autonomous inhibition produced by PTCH2 and PTCH1ΔL2 expression (Fig. 1, A–O).

Figure 1.

Ectopic HHIP1 expression non–cell-autonomously inhibits neural progenitor patterning and proliferation. (A–T and V–GG) Embryonic chicken neural tubes electroporated at Hamburger-Hamilton stage 11–13 with pCIG (A–E and V–Y), mPtch2-pCIG (F–J), mPtch1ΔL2-pCIG (K–O and Z–CC), or mHhip1-pCIG (P–T and DD–GG) and dissected 24 h postelectroporation (hpe; A–T, V, W, Z, AA, DD, and EE) or 48 hpe (X, Y, BB, CC, FF, and GG). Transverse sections from the wing axial level were stained with antibodies directed against NKX6.1 (B, C, G, H, L, M, Q, and R), PAX7 (D, E, I, J, N, O, S, and T), and phospho–histone H3 (PH3; V–GG). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (gray [A, F, K, and P] or blue [W, Y, AA, CC, EE, and GG]). (C, E, H, J, M, O, R, T, and V–GG) Nuclear EGFP expression labels electroporated cells. Arrows indicate repression of NKX6.1 expression (G, H, L, and M) or ectopic PAX7 expression (I, J, N, and O). (E, J, O, and T) Insets show individual green channels. White lines highlight non–cell-autonomous NKX6.1 repression (Q and R) and ectopic PAX7 expression (S and T). (S and T) Arrowheads demarcate the ventral most electroporated cell. (V–GG) Dotted lines bisect the neural tube into dorsal and ventral halves. (DD–GG) Arrows highlight PH3+ cells on the unelectroporated side of the neural tube, whereas brackets denote the lack of PH3+ cells resulting from HHIP1 expression. (U) Quantitation of total PH3+ cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P-values determined by two-tailed Student’s t test. Bars, 50 µm.

Analysis of neural patterning at 48 hpe indicates that both PTCH2 and PTCH1ΔL2 cell-autonomously repress NKX6.1 (Fig. S1, F–H and K–M, arrows) and induce ventral expansion of PAX7 (Fig. S1, I, J, N, and O). In contrast, Hhip1 electroporation causes a significant growth defect that is most evident in the ventral neural tube, leading to a significant reduction in the number of ventral, but not dorsal progenitors compared with Ptch2- and Ptch1ΔL2-electroporated embryos (Fig. S1, P–R [brackets], U, and V). Thus, HHIP1 antagonizes both HH-dependent neural patterning and ventral neural tube growth in a non–cell-autonomous manner.

HHIP1 inhibits neural progenitor proliferation in a non–cell-autonomous manner

To determine the cause of this HHIP1-mediated growth defect, we examined apoptosis and proliferation in neural progenitors, processes that are regulated by HH signaling (Charrier et al., 2001; Thibert et al., 2003; Cayuso et al., 2006; Saade et al., 2013). Although both PTCH1ΔL2 and HHIP1 expression transiently induce apoptosis to similar extents at 24 hpe (Fig. S2, E, F, I, and J), Hhip1 electroporation significantly reduces the number of mitotic, phospho–histone H3+ (PH3+) cells on the electroporated side of the neural tube at both 24 hpe and 48 hpe compared with pCIG and Ptch1ΔL2 (Fig. 1, U and V–GG). Strikingly, although most HHIP1-electroporated cells are found in the dorsal neural tube, we observe the greatest reduction in proliferation ventrally (Fig. 1, DD–GG, brackets; and quantified in Fig. S2, M and N). Thus, HHIP1 expression inhibits both neural progenitor patterning and proliferation in a non–cell-autonomous manner.

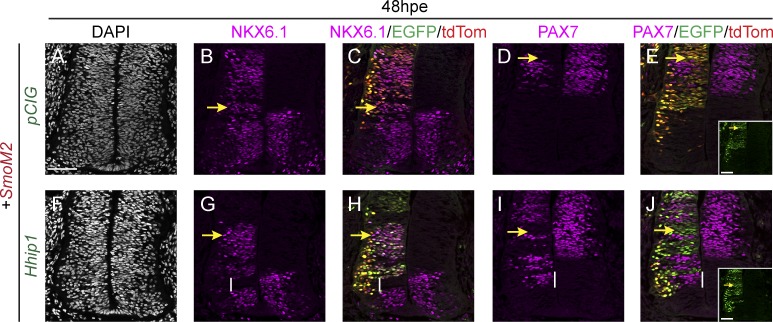

Cell-autonomous activation of HH signaling does not block the non–cell-autonomous effects of HHIP1

To further investigate the non–cell-autonomous effects of HHIP1 expression, we coelectroporated Hhip1 with a constitutively active Smo construct, SmoM2 (Xie et al., 1998). Because SMOM2 is downstream and refractory to HHIP1 inhibition, we reasoned that this would rescue any cell-autonomous HH inhibition caused by HHIP1 (Holtz et al., 2013). Indeed, SmoM2 electroporation cell autonomously induces ectopic NKX6.1+ cells (Fig. 2, B and C, yellow arrows) and represses PAX7 expression (Fig. 2, D and E, yellow arrows) at 48 hpe.

Figure 2.

HHIP1 non–cell-autonomously inhibits HH-dependent neural patterning when coexpressed with SMOM2. (A–J) Immunofluorescent analysis of neural patterning in chicken embryos electroporated at stage 11–13 with SmoM2-pCIT (A–J) and coelectroporated with either pCIG (A–E) or mHhip1-pCIG (F–J). Transverse sections collected at the wing axial level were stained with NKX6.1 (B, C, G, and H) and PAX7 (D, E, I, and J). (A and F) DAPI stains nuclei (gray). (C, E, H, and J) Electroporated cells are labeled with nuclear EGFP and tdTomato (tdTom). (E and J) Insets show individual green channels (EGFP). Yellow arrows denote ectopic NKX6.1 expression (B, C, G, and H) or repression of PAX7 (D, E, I, and J) resulting from SMOM2 expression. Vertical lines denote non–cell-autonomous inhibition of NKX6.1 expression (G and H) or ectopic PAX7 expression (I and J). Bars, 50 µm.

Coelectroporation of Hhip1 with SmoM2 also induces ectopic NKX6.1 and represses PAX7 expression (Fig. 2, G–J, yellow arrows), indicating cell-autonomous rescue of HHIP1 inhibition. However, we also detected a significant, non–cell-autonomous loss of NKX6.1 and a ventral expansion of PAX7 expression in the ventral neural tube at 24 and 48 hpe (Fig. 2, G–J; and Fig. S3, A–E, white lines), which does not occur in embryos coelectroporated with Ptch2 and SmoM2 (Fig. S3, P–T). These data support the notion that HHIP1 non–cell-autonomously inhibits HH signaling in the chicken neural tube.

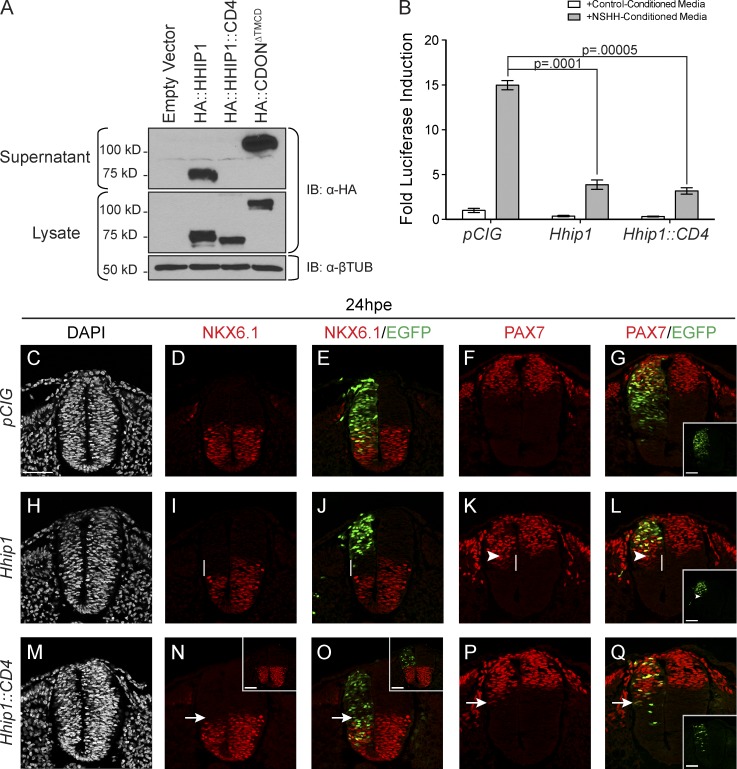

HHIP1 is a secreted protein

To determine how HHIP1 expression produces non–cell-autonomous effects, we investigated whether HHIP1 functions as a secreted HH antagonist. Previous studies using COS-7 cells classified HHIP1 as a type I transmembrane protein with a C-terminal 22–amino acid transmembrane domain (Chuang and McMahon, 1999). However, a subsequent study identified the presence of overexpressed HHIP1 in cell supernatants (Coulombe et al., 2004). Surprisingly, we observed significant accumulation of N-terminally HA-tagged HHIP1 (HA::HHIP1) in supernatants when expressed in HH-responsive NIH/3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, an HHIP1 chimera in which the putative C-terminal membrane anchor is replaced with the transmembrane domain from the CD4 protein (HA::HHIP1::CD4) is not secreted (Fig. 3 A; Maddon et al., 1985). Thus, the CD4 transmembrane domain is sufficient to anchor HHIP1 to the cell surface. As a positive control, we also detected secreted CDON protein (HA::CDONΔTMCD) in NIH/3T3 cell supernatants (Fig. 3 A). These data suggest that HHIP1 can be secreted from cells.

Figure 3.

HHIP1 secretion mediates its non–cell-autonomous effects in the developing neural tube. (A) Western blot analysis of cell lysates (bottom) and supernatants (top) collected from NIH/3T3 fibroblasts expressing HA-tagged HHIP1 proteins and probed with an anti-HA antibody. HA::CDONΔTMCD is included as a secreted protein control. Anti–β-tubulin (βTUB) is used as a loading control. (B) HH-responsive luciferase reporter activity measured in NIH/3T3 cells stimulated with either control-conditioned media or NSHH-conditioned media and transfected with the indicated constructs. Data are presented as means ± SEM. P-values are determined by two-tailed Student’s t tests. (C–Q) Neural patterning analysis of chicken embryos electroporated at stage 11–13 with pCIG (C–G), mHhip1-pCIG (H–L), and mHhip1::CD4-pCIG (M–Q) and collected at 24 hpe. Embryos were sectioned at the wing axial level and stained with antibodies against NKX6.1 (D, E, I, J, N, and O) and PAX7 (F, G, K, L, P, and Q). DAPI staining detects nuclei (gray; C, H, and M). (E, G, J, L, O, and Q) Electroporated cells are labeled with nuclear EGFP. (G, L, and Q) Insets show individual green channels. White lines highlight non–cell-autonomous NKX6.1 repression (I and J) and ectopic PAX7 expression (K and L). (K and L) Arrowheads demarcate the ventral most electroporated cell. Arrows indicate cell-autonomous inhibition of NKX6.1 expression (N and O) and ectopic PAX7 expression (P and Q) resulting from mHHIP1::CD4 expression. (N and O) Insets in represent embryos with dorsally restricted HHIP1::CD4 expression. Bars, 50 µm.

Membrane anchoring abrogates the non–cell-autonomous effects of HHIP1

To test whether the non–cell-autonomous effects of HHIP1 in the neural tube result from HHIP1 secretion, we compared the activity of secreted HHIP1 protein, and membrane-tethered HHIP1::CD4. Importantly, HHIP1 and HHIP1::CD4 function equivalently to antagonize HH-mediated pathway activation in NIH/3T3 cells (Fig. 3 B); thus, membrane anchoring of HHIP1 does not compromise its cell-autonomous inhibitory activity.

We next analyzed neural patterning in embryos electroporated with either Hhip1 or Hhip1::CD4 at 24 hpe. HHIP1 non–cell-autonomously inhibits NKX6.1 and induces ectopic PAX7 expression at 24 hpe (Fig. 3, I–L, white lines). In contrast, HHIP1::CD4 antagonizes NKX6.1 and induces PAX7 expression exclusively in a cell-autonomous manner at 24 hpe (Fig. 3, N–Q, arrows). At 48 hpe, the most prominent effect of HHIP1 expression is a significant growth defect in the ventral neural tube; however, membrane anchoring of HHIP1 partially rescues the growth of ventral neural progenitors at 48 hpe based on gross tissue morphology (Fig. S4, G and L) and quantitation of PH3+ cells at 24 hpe (Fig. S4 A). Furthermore, HHIP1::CD4 cell-autonomously inhibits expression of the high-level HH target, NKX2.2 (Fig. S4, M and N, arrows) and induces persistent ectopic expression of PAX7 at 48 hpe (Fig. S4, O and P, arrows), demonstrating effective antagonism of HH signaling. Overall, these data suggest that the non–cell-autonomous effects of HHIP1 on both patterning and proliferation of neural progenitors arise from HHIP1 secretion.

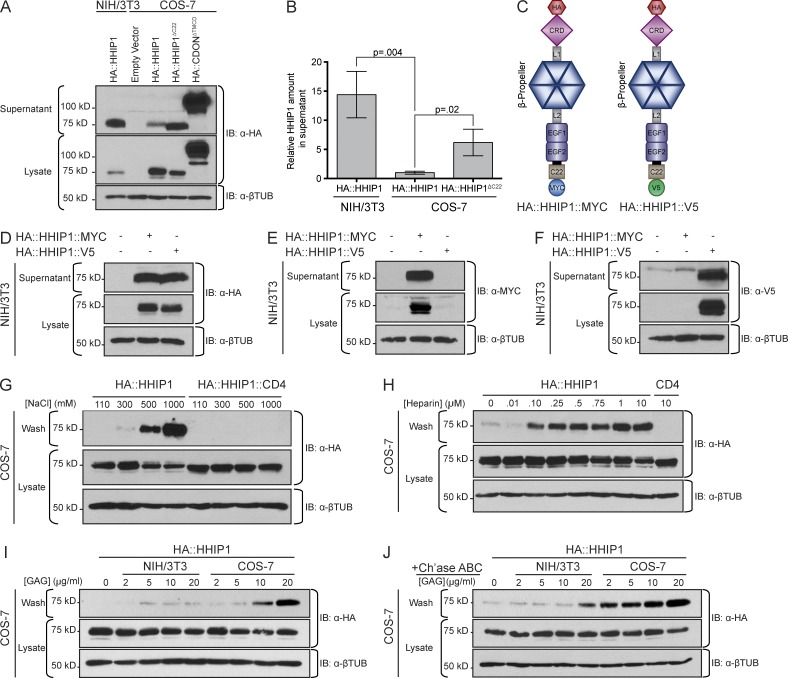

HHIP1 associates with the cell surface through cell type–specific interactions with HS

To resolve our data demonstrating HHIP1 secretion in NIH/3T3 cells with previously published data showing cellular retention of HHIP1 in COS-7 cells (Chuang and McMahon, 1999), we directly compared HA::HHIP1 secretion from NIH/3T3 and COS-7 cells. HA::HHIP1 robustly accumulates in NIH/3T3 cell supernatants (Fig. 4 A). However, HA::HHIP1 secretion is significantly reduced in supernatants collected from COS-7 cells, despite increased HA::HHIP1 expression (Fig. 4, A and B). In fact, in some instances, we failed to detect significant HA::HHIP1 secretion from COS-7 cells (see Fig. 6 F). Consistent with a previous study, an HHIP1 protein lacking the putative C-terminal 22–amino acid membrane-spanning helix, HA::HHIP1ΔC22, accumulates in COS-7 cell supernatants (Fig. 4, A and B; Chuang and McMahon, 1999). Importantly, COS-7 cells are not generally defective in protein secretion based on the robust secretion of HA::CDONΔTMCD (Fig. 4 A). Overall, these data suggest that the balance between membrane retention and release of HHIP1 depends on the cellular context.

Figure 4.

HHIP1 is retained at the cell surface through interactions with HS. (A) Western blot analysis of cell lysates (bottom) and supernatants (top) collected from NIH/3T3 and COS-7 cells expressing HA-tagged HHIP1 protein. HA::CDONΔTMCD is included as a secreted protein control. (B) Quantitation of HHIP1 secretion from NIH/3T3 and COS-7 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P-values determined by two-tailed Student’s t test. (C) Schematic of dual-tagged HHIP1 constructs. (D–F) Immunoblot detection of dual-tagged HHIP1 constructs in supernatants (top) and lysates (bottom) collected from NIH/3T3 cells and probed with anti-HA (D), anti-MYC (E), and anti-V5 (F) antibodies. (G) COS-7 cells expressing HA::HHIP1 were washed for 20 min with solutions containing increasing NaCl concentrations. Both the washes (top) and cell lysates (bottom) were assayed by Western blot analysis for HHIP1 expression. (H) As in G, except using washes containing increasing Heparin concentrations. (I and J) As in G and H, except using washes containing GAGs isolated from NIH/3T3 and COS-7 cells pre (I)- and post (J)-Chondroitinase ABC (Ch’ase ABC) treatment. (A and D–J, bottom) Anti–β-tubulin (βTUB) is used as a loading control. IB, immunoblot.

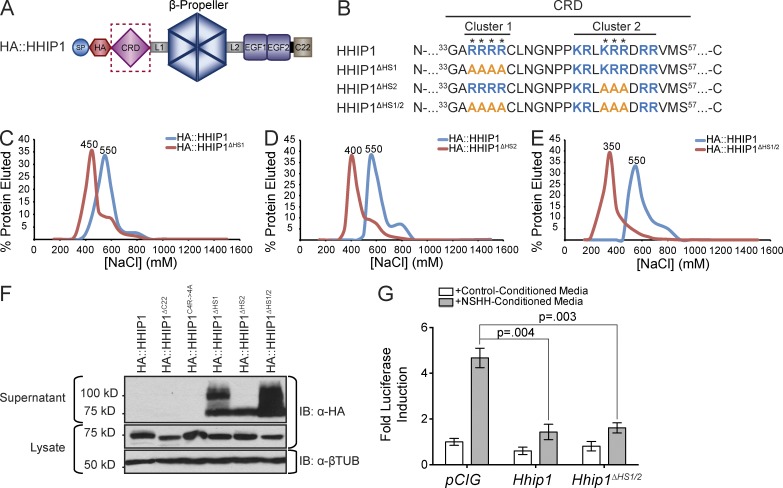

Figure 6.

Identification of specific residues that mediate HS binding and cell surface retention of HHIP1. (A) Cartoon depiction of HA::HHIP1. (B) Sequence analysis identifies two clusters of basic residues (blue) in the CRD that were mutagenized to alanines (orange) to generate HA::HHIP1ΔHS1, HA::HHIP1ΔHS2, and HA::HHIP1ΔHS1/2. (C–E) Heparin binding of HA::HHIP1 (C–E), HA::HHIP1ΔHS1 (C), HA::HHIP1ΔHS2 (D), and HA::HHIP1ΔHS1/2 (E) was assessed by heparin-agarose chromatography. NaCl elution peaks (in millimolars) are indicated above each curve. Representative data are presented from at least three replicates per construct. (F) Immunoblot analysis of COS-7 cell lysates (bottom) and supernatants (top) expressing HA-tagged HHIP1 HS-binding mutants. Of note, in addition to the expected 75-kD HHIP1 band, we also observe the presence of a 100-kD form in some of the HS-binding mutants. IB, immunoblot; βTUB, β-tubulin. (G) HH-responsive luciferase reporter activity measured from NIH/3T3 cells stimulated with either control-conditioned media or NSHH-conditioned media and transfected with the indicated constructs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P-value is determined by two-tailed Student’s t test.

To test whether HHIP1 was proteolytically cleaved in NIH/3T3 cells, we generated dual-tagged HHIP1 constructs that possess an N-terminal HA tag and either a C-terminal MYC or V5 epitope (Fig. 4 C). Both HA::HHIP1::MYC and HA::HHIP1::V5 accumulate in NIH/3T3 cell supernatants as full-length proteins based on Western blot detection of HA and MYC/V5 (Fig. 4, D–F), demonstrating that proteolytic cleavage of HHIP1 is not a requirement for secretion. HHIP1 has also been implicated as a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (PI; GPI)-anchored protein (Bosanac et al., 2009); however, PI-PLC treatment fails to release HA::HHIP1 or HA::HHIP1::CD4 from the cell surface of COS-7 cells, whereas a GPI-anchored version of the HH coreceptor CDON (HA::CDON::GPI), is effectively released from the cell surface by PI-PLC treatment (Fig. S5 A).

To examine whether HHIP1 is retained at the cell surface through ionic interactions, we treated COS-7 cells expressing HA::HHIP1 with buffers possessing increasing NaCl concentrations. Surprisingly, we detected HA::HHIP1 release from COS-7 cells with as little as 300 mM NaCl, which increases substantially after incubation with 500 mM NaCl (Fig. 4 G). As a control, HA::HHIP1::CD4 remains associated with the cell pellet at all NaCl concentrations tested (Fig. 4 G). These data are consistent with HHIP1 being anchored to the cell surface through intermolecular interactions.

To identify the binding partner responsible for membrane retention of HHIP1, we first sought to determine whether HHIP1 is retained at the cell surface through interactions with HS, an abundant glycosaminoglycan (GAG) that has been implicated in multiple aspects of HH signal transduction (Perrimon and Bernfield, 2000; Lin, 2004; Häcker et al., 2005). First, we attempted to disrupt HHIP1 retention at the cell surface in COS-7 cells using heparin, a structural analogue of HS (Esko and Lindahl, 2001). Incubation with as little as 100 nM heparin effectively competes HA::HHIP1 from the cell surface of COS-7 cells, whereas HA::HHIP1::CD4 is refractory to competition with ≤10 µM heparin (Fig. 4 H). This effect is specific to heparin as we only achieved minimal HHIP1 release with a 1000-fold excess of chondroitin sulfate A or a 100-fold excess of dermatan sulfate (Fig. S5, B and C).

To determine whether HHIP1 membrane retention is affected by cell type–specific modifications in HS composition, which vary between cell types and over developmental time, we isolated HS from both NIH/3T3 and COS-7 cells to perform cell surface competition assays (Esko and Lindahl, 2001; Rubin et al., 2002; Allen and Rapraeger, 2003). Because COS-7 cells largely retain HHIP1, we reasoned that COS-7 HS would preferentially bind and thus more effectively compete HHIP1 from the cell surface than HS isolated from NIH/3T3 cells. As expected, COS-7 GAGs more effectively compete HHIP1 from the cell surface than NIH/3T3 GAGs (Fig. 4 I). After enriching for HS by Chondroitinase ABC treatment, we observed HHIP1 release with as little as 2 µg/ml of COS-7 HS, which is more effective than a 10-fold excess of NIH/3T3 HS (Fig. 4 J). Collectively, these data suggest that HHIP1 is retained at the cell surface through cell type–specific interactions with HS.

HHIP1 binds to HS through basic amino acids in the N-terminal CRD

To determine the HS-binding motif in HHIP1, we initially focused on the HHIP1 C terminus, which was previously implicated in HHIP1 surface retention (Fig. 4 A; Chuang and McMahon, 1999). Molecular modeling of the C-terminal 30 amino acids identifies a putative HS binding site comprised of four arginine residues (R671, R673, R674, and R678; Fig. 5, A and B). Interestingly, this analysis also revealed that the C-terminal helix is amphipathic and is thus unlikely to form a transmembrane domain (Fig. 5 A).

Figure 5.

HHIP1 directly binds to HS through the N-terminal CRD. (A) Representative structural model of the HHIP1 C-terminal 30 residues shown as ribbons (left) and electrostatic potential (right). Four N-terminal arginines are highlighted (dotted circle). Electrostatic potential is calculated from −10 kbT/ec (red, acidic) to 10 kbT/ec (blue, basic). Selected residues are depicted in stick representation. (B, top) Cartoon depiction of HA::HHIP1. (bottom) Sequence analysis identifies a cluster of basic residues (blue) in the C-terminal 30 amino acids that were mutagenized to alanines (orange) to generate HHIP1C4R-4A. SP, signal peptide. (C–E) Heparin-agarose chromatography was used to measure heparin-binding affinities for HA::HHIP1 (C–E), HA::HHIP1ΔC30 (C) HA::HHIP1C4R->4A (D), and HA::HHIP1ΔCRD (E). NaCl concentrations (in millimolars) corresponding to elution peaks are indicated above each curve. The data shown are representative experiments from at least three replicates for each construct. (F–I) Representative SPR binding experiments demonstrating direct interactions between HHIP1(18–670) (F and H) or HHIP1(212–670) (F and H) with Heparin (F and G) and HS (H and I). (C–I) Cartoon depictions of each construct are presented above each dataset. Each SPR analysis is a representative experiment from at least three replicates per condition. (J) Representative model of the HHIP1 CRD. (left) Ribbon representation in rainbow coloring from blue (N terminus) to red (C terminus). Potential disulphide bridges are shown in Roman numerals. (right) Electrostatic potential from −10 kbT/ec (red, acidic) to 10 kbT/ec (blue, basic). The dotted box highlights the amino acids represented in K. (K) Close-up view of the potential HHIP1-CRD HS binding site shown in stick representation in atomic coloring (cyan, carbon; blue, nitrogen; red, oxygen; yellow, sulfur).

We performed heparin-agarose chromatography to investigate HHIP1–HS interactions. HA::HHIP1 binds to heparin-agarose with a peak elution of 550 mM NaCl (Fig. 5 C). Deletion of the C-terminal 30 amino acids (HHIP1ΔC30), containing the potential HS-binding motif, shifts the elution peak to 450 mM NaCl, indicating reduced heparin binding (Fig. 5 C). However, site-directed mutagenesis of the four arginines to alanines (HA::HHIP1C4R→4A) does not affect heparin binding (Fig. 5 D). Additionally, replacing the C terminus with a heterologous transmembrane domain (HA::HHIP1::CD4) restores heparin binding (Fig. S5 D). These data suggest that additional motifs are required for HS-binding and surface retention.

The EGF domains and the β-propeller region are largely dispensable for heparin binding (Fig. S5, E and F). However, deletion of the N-terminal CRD of HHIP1 (HA::HHIP1ΔCRD) shifts the elution peak to 400 mM NaCl (Fig. 5 E). Importantly, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments confirm a direct interaction between purified HHIP1 with heparin (Kd = 100 nM) that is reduced 50-fold upon deletion of the N-terminal CRD (Kd = 5,000 nM; Fig. 5, F and G). Similar results are observed with SPR analysis of HHIP1 and HS interactions (Fig. 5, H and I). Additionally, the purified HHIP1 CRD directly binds both heparin and HS (Fig. S5, G and H). Molecular modeling of the CRD domain reveals a positively charged region at the surface (Fig. 5 J), including a potential HS binding site comprised of several basic arginine and lysine residues (Fig. 5 K). Based on this model, we investigated two clusters of basic amino acids that comprise the putative HS-binding moiety (Fig. 6, A and B). Mutation of four arginines to alanines in the first basic cluster (HA::HHIP1ΔHS1) shifts the heparin elution peak to 450 mM NaCl (Fig. 6 C). Additionally, replacing the central KRR motif of cluster 2 with alanine residues (HA::HHIP1ΔHS2) weakens heparin binding and produces an elution peak of 400 mM NaCl (Fig. 6 D). A double mutant construct, HA::HHIP1ΔHS1/2, (Fig. 6 B), elutes at a peak of 350 mM NaCl (Fig. 6 E), suggesting that these two motifs cooperate to bind HS. Strikingly, HA::HHIP1ΔHS1, HA::HHIP1ΔHS2, and HA::HHIP1ΔHS1/2 proteins accumulate in COS-7 cell supernatants (Fig. 6 F). Collectively, these data suggest that HHIP1 is retained at the cell surface through interactions between HS and basic amino acids present within the HHIP1-CRD.

HHIP1 interactions with HS promote BM localization and HH pathway antagonism in the chicken neural tube

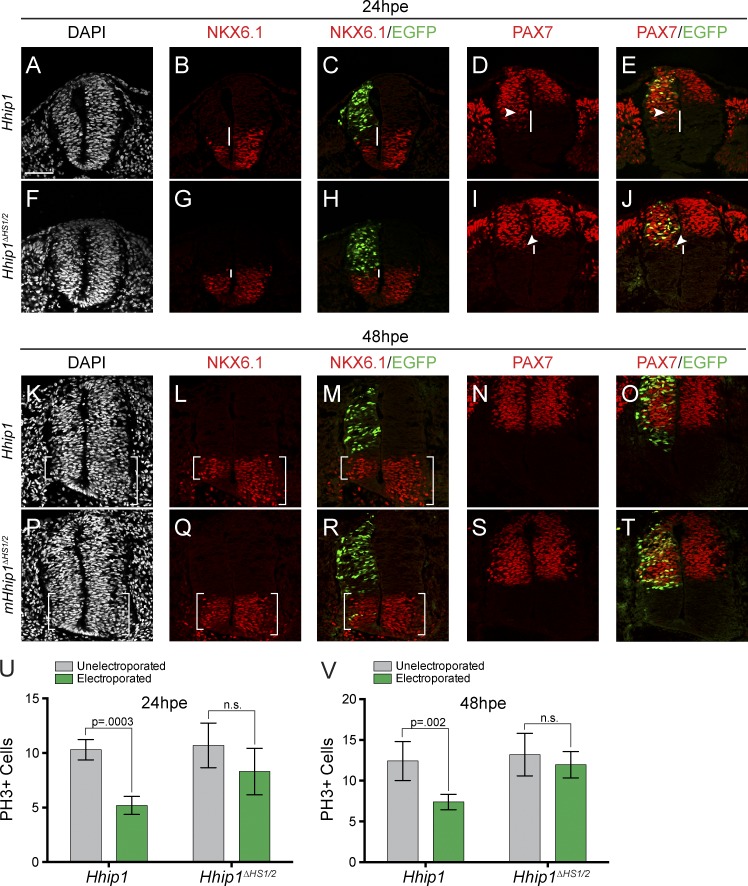

To determine the functional role of the HHIP1–HS interaction, we assessed signaling in NIH/3T3 cells. HHIP1ΔHS1/2 antagonizes Sonic HH (SHH)–mediated pathway activity in NIH/3T3 cells equivalently to wild-type HHIP1 (Fig. 6 G). Surprisingly, HHIP1ΔHS1/2 expression in the developing chicken neural tube produces limited non–cell-autonomous inhibition of SHH signaling (Fig. 7, G–J, white lines). Additionally, at 48 hpe, HHIP1ΔHS1/2 expression does not alter ventral neural tube growth as assessed by DAPI staining and the size of the NKX6.1+ domain (Fig. 7, P–R). HHIP1ΔHS1/2 does induce cell death similar to HHIP1 (Fig. S5, I–N) but does not affect neural progenitor proliferation at 24 and 48 hpe (Fig. 7, U and V).

Figure 7.

HHIP1–HS interaction promotes long-range inhibition of HH-dependent patterning and proliferation. (A–T) Hamburger–Hamilton stage 11–13 chicken embryos electroporated with mHhip1-pCIG (A–E and K–O) and mHhip1ΔHS1/2-pCIG (F–J and P–T) were collected at 24 hpe (A–J) and 48 hpe (K–T), sectioned at the wing axial level, and immunostained with antibodies raised against NKX6.1 (B, C, G, H, L, M, Q, and R) and PAX7 (D, E, I, J, N, O, S, and T). (C, E, H, J, M, O, R, and T) Electroporated cells express nuclear EGFP. (A, F, K, and P) DAPI stains nuclei (gray). White lines indicate non–cell-autonomous repression of NKX6.1 expression (B, C, G, and H) and ectopic expansion of PAX7 (D, E, I, and J). (D, E, I, and J) White arrowheads demarcate the ventral most electroporated cell. Brackets in K–M and P–R denote the size of the NKX6.1+ domain. (U and V) Quantitation of PH3+ cells in embryos electroporated with the indicated constructs and collected at 24 hpe (U) and 48 hpe (V). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P-values determined by Student’s two-tailed t test. Bar, 50 µm.

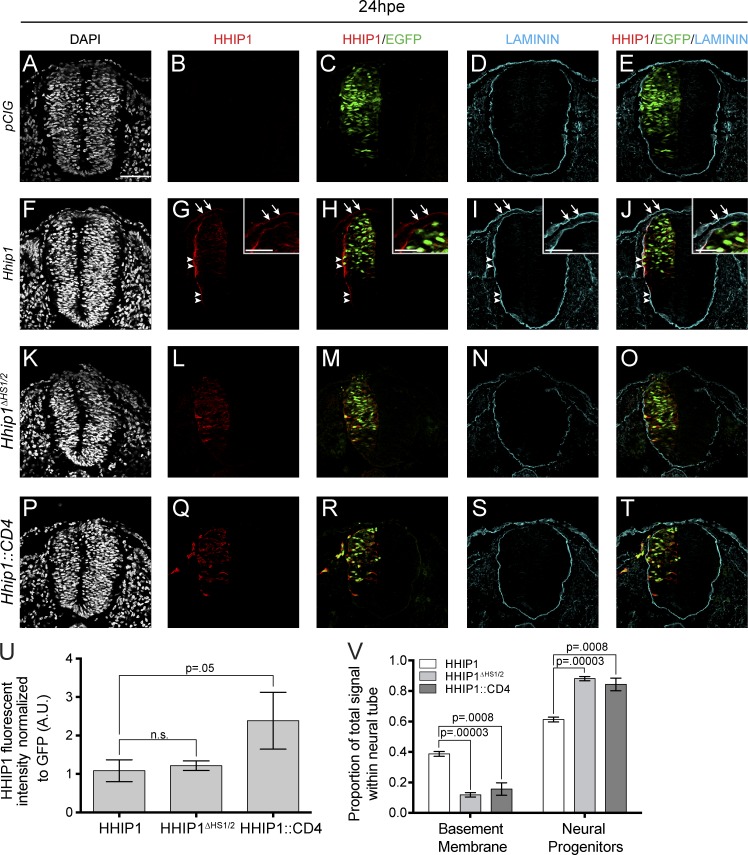

Because HHIP1 and HHIP1ΔHS1/2 function equivalently in cell-based assays, we reasoned that HS binding might control the tissue localization of HHIP1 in the neural tube to promote long-range HH inhibition. Toward this end, we stained embryos electroporated with Hhip1 and Hhip1ΔHS1/2 with an anti-HHIP1 antibody that does not detect the endogenous chicken HHIP1 protein (Fig. 8, A–E). Intriguingly, HHIP1 protein primarily localizes to the basal side of the neuroepithelium when expressed in the chicken neural tube and colocalizes with the BM component Laminin (Fig. 8, F–J, arrowheads). We also observe colocalization between HHIP1 and Laminin in the surface ectoderm (Fig. 8, F–J, arrows and insets). Strikingly, HHIP1ΔHS1/2 fails to localize to the basal side of the epithelium and surface ectoderm and remains associated with electroporated cells (Fig. 8, K–O), similar to the localization of membrane-anchored HHIP1::CD4 (Fig. 8, P–T). Quantitation of these data demonstrates that although HHIP1 and HHIP1ΔHS1/2 are expressed at equal levels, HHIP1ΔHS1/2 is significantly less enriched in the BM compared with HHIP1 (Fig. 8, U and V). Collectively, these data indicate that HS binding mediates HHIP1 localization to the neural tube BM and is required to promote long-range inhibition of HH signaling.

Figure 8.

HS binding is required to localize HHIP1 to the neuroepithelial BM. (A–T) Immunofluorescent detection of HHIP1 (B, C, E, G, H, J, L, M, O, Q, R, and T) and Laminin (D, E, I, J, N, O, S, and T) in embryos electroporated with pCIG (A–E), mHhip1-pCIG (F–J), mHhip1ΔHS1/2-pCIG (K–O), and mHhip1::CD4-pCIG (P–T) and isolated 24 hpe. (A, F, K, and P) DAPI stains nuclei (gray). (C, E, H, J, M, O, R, and T) Nuclear EGFP labels electroporated cells. (G–J) Note HHIP1 colocalization with Laminin in the neural tube (arrowheads) and surface ectoderm (arrows, insets). (U) Quantitation of HHIP1 fluorescent intensity normalized to GFP expression. A.U., arbitrary unit. (V) Data in U binned into signal measured within the BM or neural progenitors. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. P-values determined by Student’s two-tailed t test. Bars: (A) 50 µm; (G, H, I, and J, insets) 25 µm.

Endogenous HHIP1 protein is secreted and associates with the BM in the developing neuroepithelium

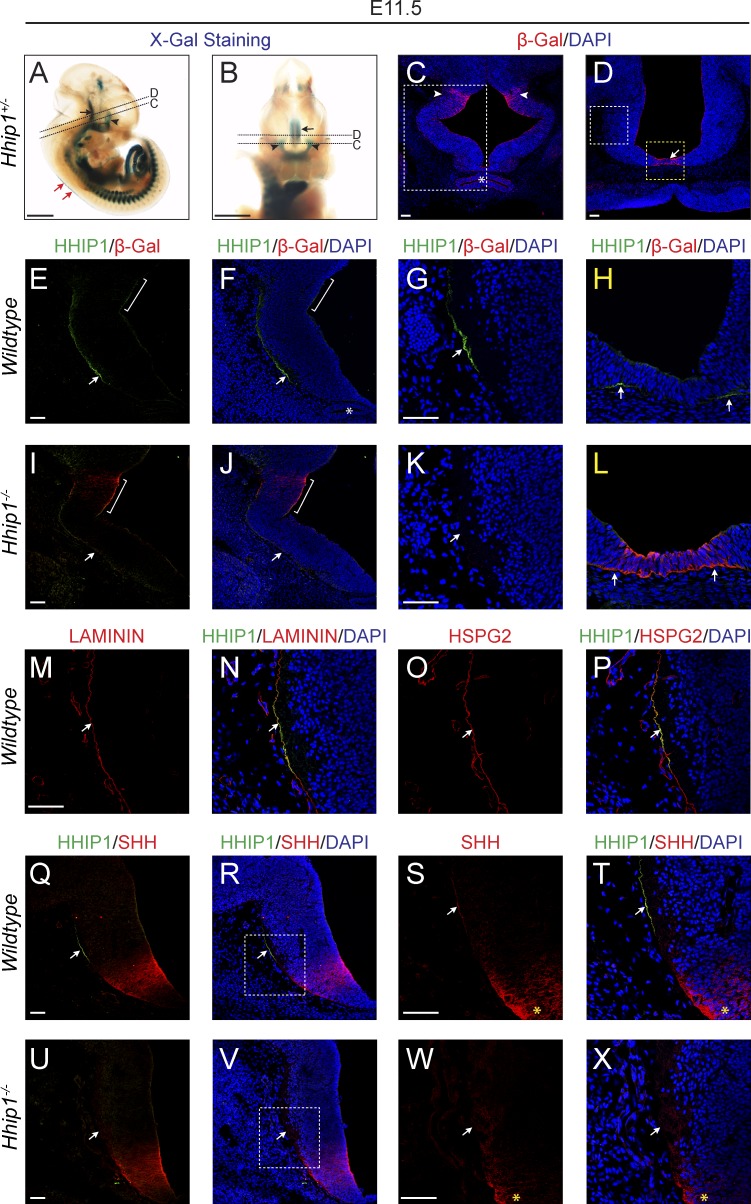

We next sought to determine the localization of endogenous HHIP1 protein in the neural tube. Using whole-mount X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) staining of Hhip1+/− embryos, which express a lacZ reporter from the endogenous Hhip1 locus, we detect significant expression in the roof plate of the developing spinal cord (Fig. 9 A, red arrows), consistent with previously published data in Xenopus laevis (Cornesse et al., 2005). Unfortunately, we did not detect HHIP1 protein at this axial level (unpublished data). However, we also detected Hhip1 expression in the developing diencephalon, (Fig. 9, A and B, arrows and arrowheads; Chuang et al., 2003). HH signaling plays a critical role in the growth and patterning of the developing midbrain, and mutations in the HH pathway produce diencephalic defects in humans (Ericson et al., 1995; Dale et al., 1997; Treier et al., 2001; Ishibashi and McMahon, 2002; Roessler et al., 2003; Szabó et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2012). At the level of Rathke’s pouch, Hhip1 is expressed in more dorsal regions of the diencephalon (Fig. 9, A–C, arrowheads) and at the midline caudal to the developing pituitary (Fig. 9, A, B, and D, arrows). In wild-type embryos, HHIP1 protein is not readily observed within the neuroepithelium of the dorsal diencephalon but instead accumulates basally at a significant distance from its site of production (Fig. 9, E–H, arrows). Importantly, HHIP1 signal is not detected in Hhip1−/− embryos, confirming antibody specificity (Fig. 9, I–L). Consistent with our analysis in the chicken neural tube, endogenous HHIP1 protein colocalizes with Laminin in the BM (Fig. 9, M and N, arrows). Strikingly, we also observe an association between HHIP1 and the HS-decorated BM protein, Perlecan (HS proteoglycan 2 [HSPG2]; Fig. 9, O and P, arrows). Importantly, HHIP1 does not associate with axonal projections as assessed by labeling with TUJ1 (Fig. S5, O–Q, arrows).

Figure 9.

Endogenous HHIP1 protein is secreted and accumulates in the BM of the developing diencephalon. (A and B) Whole-mount X-Gal staining of E11.5 Hhip1+/− mouse embryos. (C–X) Immunofluorescent detection of β-Galactosidase (β-Gal; C–L), HHIP1 (E–X), Laminin (M and N), HSPG2 (O and P), and SHH (Q–X) in E11.5 Hhip1+/+ (E–H, M–P, and Q–T), Hhip1+/− (C and D), and Hhip1−/− (I–L and U–X) mouse embryos sectioned at the axial level of the diencephalon. (C, D, F–H, J–L, N, P, R, T, V, and X) DAPI reveals nuclei (blue). (A, B, and D) Arrows indicate Hhip1 expression in the ventral diencephalon. (A–C) Arrowheads demarcate HHIP1 production in more dorsal regions of the diencephalon. (A and B) Dashed lines represent axial level of images depicted in C and D. Red arrows in A show the spinal cord roof plate. (C) White box corresponds to area analyzed in panels E, F, I, and J. (D) White box demonstrates region presented in G, K, M–P, and Q–X. (D) Yellow box denotes area analyzed in H and L. (C, F, and J) Asterisks demarcates Rathke’s pouch. (E, F, I, and J) Brackets highlight area of HHIP1 production. (E–H, M–P, and Q–T) Arrows depict the presence of HHIP1 protein in the neuroepithelial BM that colocalizes with Laminin (M and N), HSPG2 (O and P), and SHH (Q–T). (L and U–X) HHIP1 protein signal is absent in Hhip1−/− embryos (arrows). Note the accumulation of SHH in the neuroepithelial BM (arrows, S and T) that is absent in Hhip1−/− embryos (W and X). (R and V) White boxes demonstrate area of higher magnification presented in S, T, W, and X. (S, T, W, and X) Yellow asterisks highlight region of SHH production. A commercial HHIP1 antibody (R&D Systems) was used in E–P, whereas a newly developed HHIP1 antibody was used in Q–X. Bars: (A and B) 1 mm; (C–E, G, I, K, M, Q, S, U, and W) 50 µm.

To validate the distribution of secreted HHIP1 protein, we generated a novel HHIP1 antibody. Notably, this reagent also specifically detects HHIP1 protein in the neuroepithelial BM near the source of SHH ligand production in the ventral diencephalon (Fig. 9, Q–X, arrows). Interestingly, we observed accumulation of SHH ligand within the BM at a distance from the SHH source that colocalizes with HHIP1 in discrete puncta (Fig. 9, S and T; and Fig. S5, R–U, arrows). Strikingly, this accumulation of SHH is lost in Hhip1−/− embryos, demonstrating that HHIP1 can interact with and affect the distribution of SHH ligand in the neuroepithelial BM (Fig. 9, W and X; and Fig. S5, V–Y, arrows). Collectively, these data demonstrate that endogenous HHIP1 protein is secreted and associates with HS-containing BM of the developing neuroepithelium.

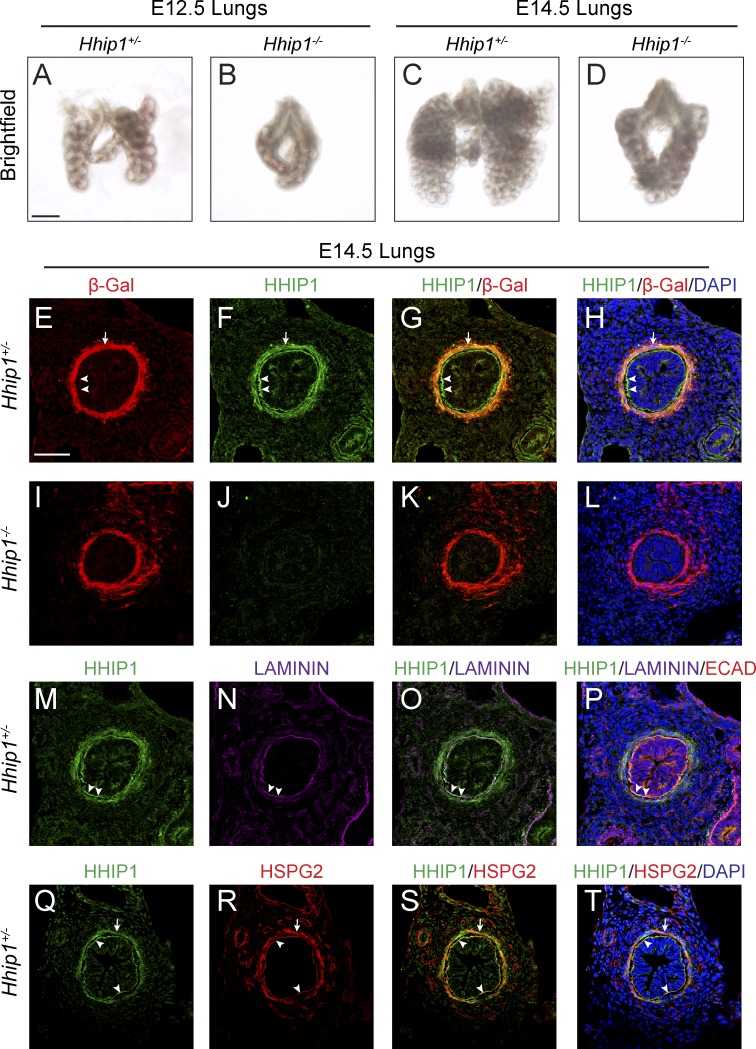

Endogenous HHIP1 is produced and secreted by lung mesenchymal fibroblasts

To determine whether endogenous HHIP1 protein is secreted and associates with BM outside of the neuroepithelium, we investigated HHIP1 distribution in the developing lung, where HHIP1 is critical for branching morphogenesis (Chuang et al., 2003). Hhip1−/− lungs collected at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) and E14.5 possess only two rudimentary lung lobes instead of the normal five and largely fail to undergo secondary branching morphogenesis (Fig. 10, A–D; Chuang et al., 2003). Consistent with a previous study, Hhip1 is exclusively expressed by mesenchymal fibroblasts proximal to the lung epithelium but is excluded from the epithelium itself as determined by β-Galactosidase (β-Gal) expression in Hhip1+/− lungs (Fig. 10, E–H, arrows; Chuang et al., 2003). HHIP1 protein colocalizes with β-Gal in the lung mesenchyme; however, we also detect HHIP1 protein on the basal side of epithelial cells that does not colocalize with β-Gal (Fig. 10 E–H, arrowheads). This signal is specific for HHIP1 as it is absent in Hhip1−/− embryos (Fig. 10, I–L). The epithelial HHIP1 protein staining colocalizes with the BM markers Laminin and Perlecan (Fig. 10, M–T, arrowheads). Interestingly, HHIP1 is only detected in regions where Perlecan is present (Fig. 10, Q–T, arrows). Collectively, these data indicate that endogenous HHIP1 protein is produced and secreted by lung mesenchymal fibroblasts and accumulates in the HS-containing BM of the lung epithelium.

Figure 10.

Endogenous HHIP1 protein is secreted and accumulates in the epithelial BM in the embryonic lung. (A–D) Whole-mount images of E12.5 (A and B) and E14.5 (C and D) mouse lungs isolated from Hhip1+/− (A and C) and Hhip1−/− (B and D) embryos. (E–T) Immunofluorescent detection of β-Galactosidase (β-Gal; E, G–I, K, and L), HHIP1 (F–H, J–L, M, O–Q, S, and T), Laminin (N–P), E-Cadherin (ECAD; P), and HSPG2 (R–T) in sections isolated from E14.5 Hhip1+/− (E–H and M–T) and Hhip1−/− (I–L) lungs. (H, L, P, and T) DAPI staining reveals nuclei (blue). Arrows demonstrate overlap between HHIP1 and β-Gal (E–H) or HSPG2 (Q–T) protein expression in the lung mesenchyme. (E–H and M–T) Arrowheads highlight HHIP1 protein staining in the epithelial BM. A commercial HHIP1 antibody (R&D Systems) was used in E–P, whereas a newly developed HHIP1 antibody was used in Q–T. Bars: (A) 500 µm; (E) 50 µm.

Discussion

Evidence for HHIP1 as a secreted antagonist of vertebrate HH signaling

Secreted, ligand-binding antagonists are common components of morphogen signaling pathways, including Noggin and Chordin in the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway (Smith and Harland, 1992; Smith et al., 1993; Piccolo et al., 1996; Zimmerman et al., 1996); Lefty inhibition of Nodal signaling (Meno et al., 1996; Chen and Shen, 2004); WIF-1 and a large family of secreted frizzled receptors that function as WNT pathway antagonists (Leyns et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1997; Hsieh et al., 1999; Cruciat and Niehrs, 2013); and Cerberus, which binds to and antagonizes the activity of BMP, Nodal, and WNT ligands (Bouwmeester et al., 1996; Piccolo et al., 1999). Thus, it is surprising that the ligand-binding HH pathway antagonists described to date act exclusively as membrane bound inhibitors (Marigo et al., 1996; Stone et al., 1996; Carpenter et al., 1998; Chuang and McMahon, 1999). Here, we present functional and biochemical evidence to redefine HHIP1, previously thought to be a transmembrane-anchored protein, as a secreted antagonist of vertebrate HH signaling. Importantly, this is supported by a recent, complementary study demonstrating that HHIP1 acts as a secreted HH pathway inhibitor (Kwong et al., 2014).

HS regulation of HH pathway activity

HS regulates the activity of numerous key developmental signaling pathways including, FGF, WNT, BMP, and HH (Yan and Lin, 2009). After genetic studies in flies that identified a role for HS in the trafficking of HH ligands (Bellaiche et al., 1998; The et al., 1999), subsequent work demonstrated multiple and complex roles for HS in HH ligand trafficking, proteolytic processing and release of HH ligands, and HH signal transduction (Rubin et al., 2002; Gallet et al., 2003; Desbordes and Sanson, 2003; Lum et al., 2003; Han et al., 2004; Dierker et al., 2009; Ohlig et al., 2012). To this point studies have been restricted to direct interactions of HH ligands with HS (Whalen et al., 2013), which affects neural progenitor proliferation in flies (Park et al., 2003) and mice (Rubin et al., 2002; Chan et al., 2009; Witt et al., 2013) as well as oligodendrocyte specification in the developing spinal cord (Danesin et al., 2006; Touahri et al., 2012; Al Oustah et al., 2014).

Our study identifies a novel role for HS in HH signaling through its interactions with HHIP1. Furthermore, our data suggest that HS acts to regulate the extracellular distribution of HHIP1 as mutagenesis of the HS binding site stimulates significant release of HHIP1 from the cell surface. Importantly, and counterintuitively, interference of HHIP1–HS interactions limits long-range inhibition of HH signaling in the chicken neural tube. Interactions with HS are not required for HHIP1 activity in cell culture; instead, we find that HS binding is required to localize HHIP1 to the BM of the neuroepithelium to promote long-range inhibition of HH signaling. This role for HS in regulating the tissue distribution of HHIP1 is consistent with previous studies in Drosophila, in which disruption of HS biosynthesis prevents the distribution of HH ligands away from their source of production in the wing imaginal disc and in the developing embryo (Bellaiche et al., 1998; The et al., 1999). Our data suggest that HS regulates both HHIP1 and HH ligand diffusion within a target field. Alternatively, HS may stabilize and concentrate HHIP1 in the BM to reach the threshold levels required for effective antagonism (Lin, 2004).

HHIP1 interacts with HS with high affinity compared with the SHH ligand (HHIP1 Kd = 622 nM vs. SHH Kd = 14.5 µM; Whalen et al., 2013). The weaker SHH-HS affinity is consistent with a “rolling” interaction that promotes the establishment of the HH morphogen gradient. The strong HHIP1–HS interaction indicates that HHIP1 is likely to become fixed within an HS-rich environment, consistent with our observation of endogenous HHIP1 sequestration of SHH ligand within the neuroepithelial BM. However, the diversity of HS across cell types and tissues suggests that these interactions will vary in a tissue- and context-specific manner. Importantly, the role of HS in regulating HH-dependent signaling in vertebrates must now be considered in the context of effects on both HH ligand and HHIP1 distribution within a tissue.

Secreted HHIP1 association with HS-containing BM in multiple organs during embryogenesis

In exploring the molecular properties of HHIP1, we determined the extracellular distribution of endogenous, secreted HHIP1 protein within the BM of the developing neuroepithelium and lung. The functional route used by HH ligands during vertebrate tissue development is largely unexplored. In Drosophila, both apical and basal gradients of HH ligand produce distinct functional consequences in receiving cells (Ayers et al., 2010, 2012). In vertebrates, HH ligands have been visualized in the neuroepithelial BM by antibody detection (Gritli-Linde et al., 2001; Allen et al., 2007) and by using a Shh::GFP fusion knock-in allele (Chamberlain et al., 2008). The presence of HHIP1 within this tissue compartment and the redistribution of SHH observed in Hhip1−/− embryos implicate the BM as one functional route used by HH ligands to distribute within the neural tube. Notably, the roof plate expression of Hhip1 in the spinal cord is analogous to notochord expression of the BMP antagonists Noggin, Chordin, and Follistatin (McMahon et al., 1998; Liem et al., 2000), consistent with a role for secreted antagonists in the regulation of morphogen function during neural patterning.

In addition to the neuroepithelium, we also observed HHIP1 accumulation in the BM of the developing lung endoderm. This suggests that HHIP1 localization to the BM is a general strategy to antagonize HH pathway activity during embryogenesis. Notably, in both cases, HHIP1 distributes toward the source of HH ligand production. The strong HHIP1–HH ligand interaction in addition to the unique HS-rich environment of the BM may provide the driving forces for the tissue distribution of HHIP1.

Interestingly, the unique requirement for HHIP1 during lung development compared with PTCH1/2 may reflect the need for a secreted HH antagonist to orchestrate lung branching morphogenesis (Chuang et al., 2003). In the embryonic lung, epithelial-derived HH ligands traverse the BM to signal to the underlying mesenchyme, resulting in repression of Fgf10 expression, a key mediator of epithelial outgrowth (Bellusci et al., 1997a; Litingtung et al., 1998; Min et al., 1998; Pepicelli et al., 1998; Sekine et al., 1999; Chuang et al., 2003). Paradoxically, Fgf10 expression is maintained within the mesenchyme adjacent to the sites of highest Shh expression at growing bud tips as a result of the induction of Hhip1 expression (Bitgood and McMahon, 1995; Urase et al., 1996; Bellusci et al., 1997b; Chuang et al., 2003). HHIP1 protein localization within the lung BM may restrict SHH ligand exit from the epithelial compartment, thus preserving Fgf10 expression in the adjacent mesenchyme, providing a molecular mechanism to explain the unique genetic requirement for Hhip1 in lung branching morphogenesis.

These data also have implications for understanding human lung diseases, as HHIP1 has also been implicated in a wide variety of human lung pathologies including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, and lung cancer; thus, HH pathway inhibition by secreted HHIP1 might also have significant implications for the regulation of HH signaling in adult tissues and in human lung pathologies (Pillai et al., 2009; Van Durme et al., 2010; Young et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2012; Castaldi et al., 2014).

Materials and methods

Chicken in ovo neural tube electroporations

Electroporations were performed as previously described (Tenzen et al., 2006; Holtz et al., 2013). In brief, 1.0 µg/µl DNA mixed with 50 ng/µl Fast green was injected into Hamburger–Hamilton stage 11–13 embryos. Embryos were dissected 24 and 48 hpe, fixed in 4% PFA, and processed for immunofluorescent analysis. Electroporated cells were marked by constructs expressing either nuclear-localized EGFP (pCIG) or tdTomato (pCIT). mPtch2, mPtch1ΔL2, and all mHhip1 constructs were cloned into pCIG. SmoM2 cDNA (Xie et al., 1998) was cloned into pCIT. The pCIG and pCIT vectors drive construct expression using the chicken β-actin promoter in addition to a cytomegalovirus enhancer. An internal ribosome entry site sequence directs translation of EGFP (pCIG) or tdTomato (pCIT) from the bicistronic transcript. For coelectroporations, each construct was injected at a concentration of 0.5 µg/µl. PH3+ cells were quantified from three or more sections isolated from at least four separate embryos per condition.

HHIP1 constructs

All Hhip1 constructs were derived from a full-length mouse Hhip1 cDNA (provided by P.-T. Chuang, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA). Hhip1ΔC22 encodes for a protein that lacks aa A679–V700 of full-length HHIP1, whereas HHIP1::CD4 replaced these resides with aa V394–C417 of the mouse CD4 protein (Maddon et al., 1985). An N-terminal HA tag (YPYDVPDYA) was inserted between residues F25 and G26 preceded by a residual ClaI site. For the dual-tagged Hhip1 constructs, C-terminal MYC (EQKLISEEDL) and V5 (GKPIPNPLLGLDST) tags were added after a flexible linker (GSG) to enhance visualization by Western blot analysis. Hhip1 deletion constructs and HS-binding mutants were generated using the QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies).

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescent analysis of neural patterning was performed at the wing bud axial level at both 24 and 48 hpe (Holtz et al., 2013). The following antibodies were used: mouse IgG1 anti-NKX6.1 (1:20; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB]), mouse IgG1 anti-PAX7 (1:20; DSHB), rabbit IgG anti–cleaved caspase-3 (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit IgG anti-phospho–Histone H3 (1:1,000; EMD Millipore), mouse IgG2b anti-NKX2.2 (1:20; DSHB), goat IgG anti-HHIP1 (1:200; R&D Systems), rabbit IgG anti-Laminin (1:500; Abcam), rabbit IgG anti–β-Gal (1:5,000; MP Biomedicals), rabbit IgG, mouse IgG1 anti-SHH (1:20, DSHB), rat IgG anti-HSPG2 (1:500; EMD Millipore), and mouse IgG anti–E-Cadherin (1:500; BD). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI (1:30,000; Molecular Probes). Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (1:500; Molecular Probes) were used to detect protein localization, including Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti–goat IgG, Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti–rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti–mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti–mouse IgG1, Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti–rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti–mouse IgG, Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti–rabbit IgG, Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti–rat IgG, Alexa Fluor 594 chicken anti–goat IgG, Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti–mouse IgG1, Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti–rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor 680 donkey anti–rabbit IgG. Slides were mounted in Shandon Immu-Mount (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were captured on an upright confocal microscope (SP5 X; Leica) at room temperature using the LAS AF software (Leica). Leica 63× (type: HC Plan Apochromat CS2; NA 1.2) and 25× (type: HCX IRAPO L; NA 0.95) water immersion objectives were used. Fluorescent intensities were quantified using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) from data isolated under identical imaging conditions. Two sections from at least three embryos were analyzed in each condition. Total HHIP1 fluorescent intensity was normalized to GFP fluorescence to control for electroporation efficiency. Direct comparisons of endogenous HHIP1 protein stains between Hhip1+/+, Hhip1+/−, and Hhip1−/− embryos were collected under identical imaging conditions. NKX6.1, PAX7, and NKX2.2 antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the Department of Biological Sciences, The University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA).

Whole-mount X-Gal staining

Mouse embryos were dissected and fixed (1% formaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 0.02% NP-40) for 1 h at room temperature and then washed in PBS with 0.02% NP-40. Embryos were then stained overnight using a 1 mg/ml X-Gal substrate (Gold Biotechnology) in a PBS solution containing 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.02% NP-40. Embryos were washed in PBS and postfixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Embryos were cleared in a PBS/80% glycerol solution and imaged at room temperature on a stereoscopic microscope (SMZ1500; Nikon) using a Nikon objective (type: HR Plan Apochromat; NA 0.13) with a camera (Digital Sight DS-Ri1; Nikon). Images were acquired using the NIS Elements software (Nikon).

Luciferase assays

Luciferase reporter assays to read out HH pathway activity were performed as previously described using the ptcΔ136-GL3 luciferase reporter (Nybakken et al., 2005; Holtz et al., 2013). This reporter drives firefly luciferase expression using sequences from the D. melanogaster Ptc promoter, including three consensus cubitus interruptus/GLI-Kruppel family member binding sites (nucleotides −758 to −602 from the Ptc transcription start site) in addition to nucleotides −136 to 130 from the Ptc transcription start site. In brief, NIH/3T3 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates and transfected 16–24 h later with a ptcΔ136-GL3 luciferase reporter construct (Chen et al., 1999; Nybakken et al., 2005), pSV-β-Gal (Promega), and either empty vector or experimental constructs. After 48 h, cells were placed in low serum media in addition to either control- or N-terminal SHH (NSHH)–conditioned medium. Luciferase activity (Luciferase Assay System kit; Promega) was read 48 h later and normalized to β-Gal activity (BetaFluor β-Gal Assay kit; EMD Millipore). Data were expressed as fold induction relative to control-treated cells.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed according to standard methods. In brief, cells were lysed 48 h after transfection in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 5 mM EDTA) containing Complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche), centrifuged at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride and probed with the following antibodies: mouse IgG1 anti-HA (1:1,000; Covance), rabbit IgG anti-MYC (1:5,000; Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.), and rabbit IgG anti-V5 (1:1,000; Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.). Cell supernatants and washes from HHIP1 cell surface competition experiments were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 5 min at room temperature before SDS-PAGE. NaCl washes from cell surface competition experiments underwent buffer exchange into radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and washes from GAG competition experiments were concentrated fourfold before SDS-PAGE using Nanosep 30K Omega columns (PALL Life Sciences). Western blot intensities were quantified using ImageJ.

GAG isolation

GAG preparations were performed as previously described (Karlsson and Björnsson, 2001; Allen and Rapraeger, 2003). COS-7 and NIH/3T3 cells were grown to confluency, washed with PBS, and incubated with 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA for 30 min at 37°C. Cell–trypsin mixtures were boiled for 30 min and centrifuged at 1,500 g for 5 min at room temperature. Supernatants were isolated, and proteins were precipitated in 6% TCA for 1 h on ice. Proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. GAGs were precipitated from the remaining supernatant by overnight incubation with 5 vol ethanol at −20°C and pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. GAG pellets were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and GAGs were quantified by Alcian blue precipitation (Karlsson and Björnsson, 2001). To enrich for HS, GAGs were incubated with 0.25 U Chondroitinase ABC (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 37°C followed by Alcian blue quantitation.

Heparin-agarose chromatography

COS-7 cells expressing HA-tagged Hhip1 constructs were lysed in column buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM EDTA) with 1% NP-40 containing complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Columns were loaded with 2 ml heparin-agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) and equilibrated with 10 ml of column buffer. Lysates were diluted 1:25 in column buffer and loaded onto the column. The column was washed with 10 ml of column buffer, and HHIP1 proteins were eluted in a step gradient (4 ml per elution) of column buffer possessing increasing concentrations of NaCl. Eluates were assayed for the presence of HA-tagged HHIP1 protein by dot blot analysis. The intensity of each dot was quantified using ImageJ software and plotted as the relative amount of signal compared with the total intensity measured for all elutions.

Molecular modeling and structural analysis

Models of the C-terminal 30 residues (residues 671–700) and the N-terminal 196 residues (residues 18–213) of human HHIP1, respectively, were generated using the full-chain protein structure prediction server Robetta with the default RosettaCM (Rosetta comparative modeling) protocol (Raman et al., 2009). Electrostatic potentials were calculated with APBS (Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver; Baker et al., 2001), and structure representations were drawn with PYMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.7.0.3; Schrödinger, LLC).

Expression and purification of HHIP1 constructs

Human HHIP1 constructs (UniProt ID: Q96QV1) consisting of the N-terminal domain (HHIPN; 39–209), β-propeller and EGF repeats (217–670; Bishop et al., 2009), and ΔC-helix full length (18–670) were fused C terminally with either a hexa-histidine or a BirA recognition sequence and cloned into the pHLsec vector (Aricescu et al., 2006). Expression was performed by transient transfection in HEK-293T cells (using a semiautomated procedure; Zhao et al., 2011) in the presence of the class I α-mannosidase inhibitor kifunensine (Chang et al., 2007). 3–4 d after transfection, conditioned medium was harvested, and buffer was exchanged into PBS and purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography using TALON beads (Takara Bio Inc.). Proteins were then further purified using size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 16/60 column; GE Healthcare) in a buffer of 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl.

Hhip1 antibody generation

Rabbits were immunized against human HHIP1 protein (aa 212–670) that was purified as described in the previous section. Injections, animal husbandry, and serum production was performed at the Pocono Rabbit Farm & Laboratory (Canadensis, PA) using the 70-d antibody production package. Polyclonal HHIP1 antibodies were purified from serum using protein A agarose chromatography.

HHIP1-GAG SPR binding experiments

SPR experiments were performed using a Biacore T200 machine (GE Healthcare) in 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, and 0.05% (vol/vol) polysorbate 20, at 25°C. Proteins were buffer exchanged into running buffer, and concentrations were calculated from the absorbance at 280 nm using molar extinction coefficient values. Heparin (Iduron; mean molecular weight > 9,000 D) and HS from porcine mucosa (Iduron) were biotinylated using EZ-link Biotin-LC-Hydrazide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as described previously (Malinauskas et al., 2011) Biotinylated GAGs were immobilized upon a CM5 sensor chip to which 3,000 RU of streptavidin were coupled via primary amines. After each binding experiment, the chip was regenerated with 1.5 M NaCl at 30 µl/min for 120 s. HHIP1 proteins were injected at a flow rate of 5 µl/min for binding experiments. The signal from experimental flow cells was processed and corrected by subtraction of a blank and reference signal from a blank flow cell. In all experiments, the experimental trace returned to baseline after each regeneration. All data were analyzed using Scrubber2 (BioLogic Software) and Prism Version 6.04 (GraphPad Software). Best-fit binding curves were calculated using nonlinear curve fitting of a one-site–total binding model (Y = Bmax · X/(Kd + X) + NS · X + Background, where X is analyte concentration, and the amount of nonspecific binding is assumed to be proportional to the concentration of analyte, hence NS is the slope of nonspecific binding). The background value was constrained to zero, as the data had been previously referenced. Bmax and Kd values reported are determined for the specific binding component only.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows neural patterning analysis of electroporated chicken embryos at 48 hpe. Fig. S2 analyzes apoptosis induction and quantification of dorsal versus ventral proliferation by HHIP1 and PTCH1ΔL2 expression. Fig. S3 shows additional coelectroporations with SmoM2. Fig. S4 contains quantitation of proliferation and neural patterning analysis at 48 hpe in Hhip1::CD4 electroporated embryos. Fig. S5 shows PI-PLC treatment of HHIP1; cell surface competition experiments with chondroitin sulfate A and dermatan sulfate; further heparin agarose chromatography and SPR analysis of HHIP1 constructs; analysis of apoptosis in Hhip1ΔHS1/2 electroporated embryos; and immunofluorescent colocalization of HHIP1 with TUJ1 and SHH. Table S1 summarizes the number of embryos analyzed for the chicken electroporation experiments. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201411024/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Allen laboratory for productive discussions throughout the course of this study. We also thank Yevgeniya A. Mironova, Katherine T. Baldwin, Briana R. Dye, and Jason R. Spence for expert technical assistance and experimental advice. Confocal microscopy was performed in the Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory at the University of Michigan.

A.M. Holtz was supported by the University of Michigan Medical Scientist Training Program training grant (T32 GM007863), the Cellular and Molecular Biology Training grant (T32 GM007315), and a National Institutes of Health predoctoral fellowship (1F31 NS081806). B.L. Allen is supported by a Research Team Grant from the University of Michigan Center for Organogenesis, a Scientist Development grant (11SDG638000) from the American Heart Association, and funding from the National Institutes of Health (R21 CA167122 and R01 DC014428). C. Siebold is supported by Cancer Research UK.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- β-Gal

- β-galactosidase

- BM

- basement membrane

- BMP

- bone morphogenetic protein

- CRD

- cysteine-rich domain

- GAG

- glycosaminoglycan

- GPI

- glycosyl-PI

- HH

- Hedgehog

- HHIP1

- HH-interacting protein-1

- hpe

- hours postelectroporation

- HS

- heparan sulfate

- HSPG2

- HS proteoglycan 2

- NSHH

- N-terminal SHH

- PI

- phosphatidylinositol

- PTCH1

- Patched-1

- SHH

- Sonic HH

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

References

- Adolphe C., Nieuwenhuis E., Villani R., Li Z.J., Kaur P., Hui C.-C., and Wainwright B.J.. 2014. Patched 1 and patched 2 redundancy has a key role in regulating epidermal differentiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134:1981–1990. 10.1038/jid.2014.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ågren M., Kogerman P., Kleman M.I., Wessling M., and Toftgård R.. 2004. Expression of the PTCH1 tumor suppressor gene is regulated by alternative promoters and a single functional Gli-binding site. Gene. 330:101–114. 10.1016/j.gene.2004.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre C., Jacinto A., and Ingham P.W.. 1996. Transcriptional activation of hedgehog target genes in Drosophila is mediated directly by the cubitus interruptus protein, a member of the GLI family of zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 10:2003–2013. 10.1101/gad.10.16.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro A.C., Roberts B., Kwong L., Bijlsma M.F., and Roelink H.. 2014. Ptch2 mediates the Shh response in Ptch1-/- cells. Development. 141:3331–3339. 10.1242/dev.110056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen B.L., and Rapraeger A.C.. 2003. Spatial and temporal expression of heparan sulfate in mouse development regulates FGF and FGF receptor assembly. J. Cell Biol. 163:637–648. 10.1083/jcb.200307053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen B.L., Tenzen T., and McMahon A.P.. 2007. The Hedgehog-binding proteins Gas1 and Cdo cooperate to positively regulate Shh signaling during mouse development. Genes Dev. 21:1244–1257. 10.1101/gad.1543607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen B.L., Song J.Y., Izzi L., Althaus I.W., Kang J.-S., Charron F., Krauss R.S., and McMahon A.P.. 2011. Overlapping roles and collective requirement for the coreceptors GAS1, CDO, and BOC in SHH pathway function. Dev. Cell. 20:775–787. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Oustah A., Danesin C., Khouri-Farah N., Farreny M.-A., Escalas N., Cochard P., Glise B., and Soula C.. 2014. Dynamics of sonic hedgehog signaling in the ventral spinal cord are controlled by intrinsic changes in source cells requiring sulfatase 1. Development. 141:1392–1403. 10.1242/dev.101717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aricescu A.R., Lu W., and Jones E.Y.. 2006. A time- and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62:1243–1250. 10.1107/S0907444906029799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers K.L., Gallet A., Staccini-Lavenant L., and Thérond P.P.. 2010. The long-range activity of Hedgehog is regulated in the apical extracellular space by the glypican Dally and the hydrolase Notum. Dev. Cell. 18:605–620. 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers K.L., Mteirek R., Cervantes A., Lavenant-Staccini L., Thérond P.P., and Gallet A.. 2012. Dally and Notum regulate the switch between low and high level Hedgehog pathway signalling. Development. 139:3168–3179. 10.1242/dev.078402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker N.A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M.J., and McCammon J.A.. 2001. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:10037–10041. 10.1073/pnas.181342398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beachy P.A., Hymowitz S.G., Lazarus R.A., Leahy D.J., and Siebold C.. 2010. Interactions between Hedgehog proteins and their binding partners come into view. Genes Dev. 24:2001–2012. 10.1101/gad.1951710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellaiche Y., The I., and Perrimon N.. 1998. Tout-velu is a Drosophila homologue of the putative tumour suppressor EXT-1 and is needed for Hh diffusion. Nature. 394:85–88. 10.1038/27932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellusci S., Grindley J., Emoto H., Itoh N., and Hogan B.L.. 1997a Fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) and branching morphogenesis in the embryonic mouse lung. Development. 124:4867–4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellusci S., Furuta Y., Rush M.G., Henderson R., Winnier G., and Hogan B.L.. 1997b Involvement of Sonic hedgehog (Shh) in mouse embryonic lung growth and morphogenesis. Development. 124:53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop B., Aricescu A.R., Harlos K., O’Callaghan C.A., Jones E.Y., and Siebold C.. 2009. Structural insights into hedgehog ligand sequestration by the human hedgehog-interacting protein HHIP. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:698–703. 10.1038/nsmb.1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitgood M.J., and McMahon A.P.. 1995. Hedgehog and Bmp genes are coexpressed at many diverse sites of cell-cell interaction in the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 172:126–138. 10.1006/dbio.1995.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosanac I., Maun H.R., Scales S.J., Wen X., Lingel A., Bazan J.F., de Sauvage F.J., Hymowitz S.G., and Lazarus R.A.. 2009. The structure of SHH in complex with HHIP reveals a recognition role for the Shh pseudo active site in signaling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16:691–697. 10.1038/nsmb.1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester T., Kim S., Sasai Y., Lu B., and De Robertis E.M.. 1996. Cerberus is a head-inducing secreted factor expressed in the anterior endoderm of Spemann’s organizer. Nature. 382:595–601. 10.1038/382595a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J., Chen Y., Jessell T.M., and Struhl G.. 2001. A hedgehog-insensitive form of patched provides evidence for direct long-range morphogen activity of sonic hedgehog in the neural tube. Mol. Cell. 7:1279–1291. 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00271-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter D., Stone D.M., Brush J., Ryan A., Armanini M., Frantz G., Rosenthal A., and de Sauvage F.J.. 1998. Characterization of two patched receptors for the vertebrate hedgehog protein family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:13630–13634. 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaldi P.J., Cho M.H., San José Estépar R., McDonald M.-L.N., Laird N., Beaty T.H., Washko G., Crapo J.D., and Silverman E.K.. COPDGene Investigators . 2014. Genome-wide association identifies regulatory Loci associated with distinct local histogram emphysema patterns. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190:399–409. 10.1164/rccm.201403-0569OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayuso J., Ulloa F., Cox B., Briscoe J., and Martí E.. 2006. The Sonic hedgehog pathway independently controls the patterning, proliferation and survival of neuroepithelial cells by regulating Gli activity. Development. 133:517–528. 10.1242/dev.02228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain C.E., Jeong J., Guo C., Allen B.L., and McMahon A.P.. 2008. Notochord-derived Shh concentrates in close association with the apically positioned basal body in neural target cells and forms a dynamic gradient during neural patterning. Development. 135:1097–1106. 10.1242/dev.013086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.A., Balasubramanian S., Witt R.M., Nazemi K.J., Choi Y., Pazyra-Murphy M.F., Walsh C.O., Thompson M., and Segal R.A.. 2009. Proteoglycan interactions with Sonic Hedgehog specify mitogenic responses. Nat. Neurosci. 12:409–417. 10.1038/nn.2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang V.T., Crispin M., Aricescu A.R., Harvey D.J., Nettleship J.E., Fennelly J.A., Yu C., Boles K.S., Evans E.J., Stuart D.I., et al. . 2007. Glycoprotein structural genomics: solving the glycosylation problem. Structure. 15:267–273. 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier J.B., Lapointe F., Le Douarin N.M., and Teillet M.A.. 2001. Anti-apoptotic role of Sonic hedgehog protein at the early stages of nervous system organogenesis. Development. 128:4011–4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., and Shen M.M.. 2004. Two modes by which Lefty proteins inhibit nodal signaling. Curr. Biol. 14:618–624. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., and Struhl G.. 1996. Dual roles for patched in sequestering and transducing Hedgehog. Cell. 87:553–563. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81374-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.H., von Kessler D.P., Park W., Wang B., Ma Y., and Beachy P.A.. 1999. Nuclear trafficking of Cubitus interruptus in the transcriptional regulation of Hedgehog target gene expression. Cell. 98:305–316. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81960-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang P.T., and McMahon A.P.. 1999. Vertebrate Hedgehog signalling modulated by induction of a Hedgehog-binding protein. Nature. 397:617–621. 10.1038/17611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang P.T., Kawcak T., and McMahon A.P.. 2003. Feedback control of mammalian Hedgehog signaling by the Hedgehog-binding protein, Hip1, modulates Fgf signaling during branching morphogenesis of the lung. Genes Dev. 17:342–347. 10.1101/gad.1026303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornesse Y., Pieler T., and Hollemann T.. 2005. Olfactory and lens placode formation is controlled by the hedgehog-interacting protein (Xhip) in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 277:296–315. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulombe J., Traiffort E., Loulier K., Faure H., and Ruat M.. 2004. Hedgehog interacting protein in the mature brain: membrane-associated and soluble forms. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 25:323–333. 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruciat C.-M., and Niehrs C.. 2013. Secreted and transmembrane wnt inhibitors and activators. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a015081 10.1101/cshperspect.a015081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale J.K., Vesque C., Lints T.J., Sampath T.K., Furley A., Dodd J., and Placzek M.. 1997. Cooperation of BMP7 and SHH in the induction of forebrain ventral midline cells by prechordal mesoderm. Cell. 90:257–269. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80334-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesin C., Agius E., Escalas N., Ai X., Emerson C., Cochard P., and Soula C.. 2006. Ventral neural progenitors switch toward an oligodendroglial fate in response to increased Sonic hedgehog (Shh) activity: involvement of Sulfatase 1 in modulating Shh signaling in the ventral spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 26:5037–5048. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0715-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desbordes S.C., and Sanson B.. 2003. The glypican Dally-like is required for Hedgehog signalling in the embryonic epidermis of Drosophila . Development. 130:6245–6255. 10.1242/dev.00874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessaud E., Yang L.L., Hill K., Cox B., Ulloa F., Ribeiro A., Mynett A., Novitch B.G., and Briscoe J.. 2007. Interpretation of the sonic hedgehog morphogen gradient by a temporal adaptation mechanism. Nature. 450:717–720. 10.1038/nature06347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker T., Dreier R., Petersen A., Bordych C., and Grobe K.. 2009. Heparan sulfate-modulated, metalloprotease-mediated sonic hedgehog release from producing cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284:8013–8022. 10.1074/jbc.M806838200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J., Muhr J., Placzek M., Lints T., Jessell T.M., and Edlund T.. 1995. Sonic hedgehog induces the differentiation of ventral forebrain neurons: a common signal for ventral patterning within the neural tube. Cell. 81:747–756. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90536-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson J., Rashbass P., Schedl A., Brenner-Morton S., Kawakami A., van Heyningen V., Jessell T.M., and Briscoe J.. 1997. Pax6 controls progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in response to graded Shh signaling. Cell. 90:169–180. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80323-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esko J.D., and Lindahl U.. 2001. Molecular diversity of heparan sulfate. J. Clin. Invest. 108:169–173. 10.1172/JCI200113530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes A.J., Nakano Y., Taylor A.M., and Ingham P.W.. 1993. Genetic analysis of hedgehog signalling in the Drosophila embryo. Dev. Suppl. 115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallet A., Rodriguez R., Ruel L., and Therond P.P.. 2003. Cholesterol modification of hedgehog is required for trafficking and movement, revealing an asymmetric cellular response to hedgehog. Dev. Cell. 4:191–204. 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00031-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich L.V., Johnson R.L., Milenkovic L., McMahon J.A., and Scott M.P.. 1996. Conservation of the hedgehog/patched signaling pathway from flies to mice: induction of a mouse patched gene by Hedgehog. Genes Dev. 10:301–312. 10.1101/gad.10.3.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritli-Linde A., Lewis P., McMahon A.P., and Linde A.. 2001. The whereabouts of a morphogen: direct evidence for short- and graded long-range activity of hedgehog signaling peptides. Dev. Biol. 236:364–386. 10.1006/dbio.2001.0336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häcker U., Nybakken K., and Perrimon N.. 2005. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans: the sweet side of development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6:530–541. 10.1038/nrm1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Belenkaya T.Y., Wang B., and Lin X.. 2004. Drosophila glypicans control the cell-to-cell movement of Hedgehog by a dynamin-independent process. Development. 131:601–611. 10.1242/dev.00958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz A.M., Peterson K.A., Nishi Y., Morin S., Song J.Y., Charron F., McMahon A.P., and Allen B.L.. 2013. Essential role for ligand-dependent feedback antagonism of vertebrate hedgehog signaling by PTCH1, PTCH2 and HHIP1 during neural patterning. Development. 140:3423–3434. 10.1242/dev.095083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh J.C., Kodjabachian L., Rebbert M.L., Rattner A., Smallwood P.M., Samos C.H., Nusse R., Dawid I.B., and Nathans J.. 1999. A new secreted protein that binds to Wnt proteins and inhibits their activities. Nature. 398:431–436. 10.1038/18899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi M., and McMahon A.P.. 2002. A sonic hedgehog-dependent signaling relay regulates growth of diencephalic and mesencephalic primordia in the early mouse embryo. Development. 129:4807–4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J., and McMahon A.P.. 2005. Growth and pattern of the mammalian neural tube are governed by partially overlapping feedback activities of the hedgehog antagonists patched 1 and Hhip1. Development. 132:143–154. 10.1242/dev.01566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M., and Björnsson S.. 2001. Quantitation of proteoglycans in biological fluids using Alcian blue. Methods Mol. Biol. 171:159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahira H., Ma N.H., Tzanakakis E.S., McMahon A.P., Chuang P.-T., and Hebrok M.. 2003. Combined activities of hedgehog signaling inhibitors regulate pancreas development. Development. 130:4871–4879. 10.1242/dev.00653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]