Abstract

Background

The common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) is a small, New World primate that is used extensively in biomedical and behavioral research. This short-lived primate, with its small body size, ease of handling, and docile temperament, has emerged as a valuable model for aging and neurodegenerative research.

A growing body of research has indicated exercise, aerobic exercise especially, imparts beneficial effects to normal aging. Understanding the mechanisms underlying these positive effects of exercise, and the degree to which exercise has neurotherapeutic effects, is an important research focus. Thus, developing techniques to engage marmosets in aerobic exercise would have great advantages.

New method

Here we describe the marmoset exercise ball (MEB) paradigm: a safe (for both experimenter and subjects), novel and effective means to engage marmosets in aerobic exercise. We trained young adult male marmosets to run on treadmills for 30 min a day, 3 days a week.

Results

Our training procedures allowed us to engage male marmosets in this aerobic exercise within 4 weeks, and subjects maintained this frequency of exercise for 3 months.

Comparison with existing methods

To our knowledge, this is the first described method to engage marmosets in aerobic exercise. A major advantage of this exercise paradigm is that while it was technically forced exercise, it did not appear to induce stress in the marmosets.

Conclusions

These techniques should be useful to researchers wishing to address physiological responses of exercise in a marmoset model.

Keywords: Marmoset (Callithrix jacchus), Exercise, Aging research, Primate Models

1. Introduction

The common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) is a small (300–500 g), non-endangered New World primate that is used extensively in biomedical and behavioral research (Mansfield, 2003). Marmosets display important similarities to humans in physiology, neuroanatomy, reproduction, development, cognition, and social complexity. In the neurosciences, marmosets are especially valuable models of neurological diseases including Parkinson's disease (induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and multiple sclerosis (induced by recombinant human myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, rhMOG), and spontaneous neurodegenerative changes such as reduced neurogenesis, β -amyloid deposition in the cerebral cortex, and loss of calbindin D28k binding (Tardif et al, 2011).

In comparison with Old World primate species commonly used in biomedical research, such as rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), marmosets are smaller, easier to handle, have a low zoonotic risk, and are less costly to maintain. While we are in an era of decreased funding for biomedical research, the convergence of technological advances and increase in numbers of individuals suffering from neurological disease necessitates the utilization of a safer, more cost effective animal model that is phylogenetically closer to humans than rodents.

Exercise affects nearly every organ and tissue in the body, and is associated with an impressive range of health benefits. Exercise activates a variety of molecular and cellular processes that promote brain plasticity (Chapman et al., 2013), including enhanced angiogenesis (Al-Jarrah et al., 2010), increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Raichlen and Polk, 2013), promotion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Gibbons et al, 2014), increased neurogenesis in the striatum and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) (Tajiri et al., 2010; Steiner et al, 2006), and increased antiinflammatory responses (Cadet et al., 2003). Additionally, aerobic exercise has a neuroprotective effect against volume loss of the hippocampus, and may buffer cognitive impairment associated with aging (Erickson et al, 2011) and Alzheimer disease pathology in older adults (particularly women) with mild cognitive impairment (Baker et al., 2010). Understanding the mechanisms underlying these positive effects of exercise is an important research focus; yet many of these studies cannot be readily undertaken in humans. Most of the current research demonstrating these changes in the central nervous system has been conducted in rodents. While rodents are valuable models in biomedical research, they do not always accurately model human behavioral and biological response largely due to their 96 million years of phylogenetic distance from humans (Phillips et al, 2014; Nei et al., 2001) in contrast with marmosets that diverged from our lineage 53 million years after rodents (Steiper and Young, 2006). Therefore, the development of exercise paradigms for marmosets could greatly improve our understanding of the effects of exercise on brain and behavior, particularly in both aging and disease models.

Several paradigms for exercising macaques (Macaca spp.) can be found; those involving aerobic exercise have adapted either treadmill running or a rodent exercise wheel. Robertshaw et al. (1973) utilized an open treadmill for exercising primates. However, their technique required up to 8 months of training and could only be used on relatively tame monkeys. Others have adapted a rodent exercise wheel to primates (Curran et al, 1972; Sherry and Constable, 1992). Using this technique these researchers were able to train monkeys to exercise within 4 weeks. However, getting a monkey into and out of the exercise wheel safely, especially if it was not permanently placed in the animal's cage, appears difficult. Williams et al. (2001) and Rhyu et al. (2010) trained macaques to run on a treadmill, which was covered by a Plexiglas box with numerous air holes to allow for ventilation. Other experimenters have incorporated resistance training, where macaques which were accustomed to a primate chair were trained to strenuously exercise on a specially-designed “rowing” machine (Gisolfi et al., 1978; Myers et al, 1977). Given their small size and ecological niche as a prey species for carnivores, reptiles and raptors, one might think that captive marmosets would not adapt well to new routines and display signs of stress and anxiety. However, with the use of positive reinforcement techniques, marmosets can be trained to cooperate with several common laboratory procedures (McKinley et al., 2003). Developing a standardized and reliable technique for engaging marmosets in aerobic exercise that minimizes stress could have extensive applications in the research community. Here we describe the marmoset exercise ball (MEB) paradigm: a safe (for both experimenter and subjects), novel and effective means to engage marmosets in aerobic exercise.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

We tested 12 research naïve male marmosets [M age = 2.25 years, SD = 0.65 years; M weight at beginning of study = 410.9 g, SE = 28.7 g, range 303–578 g] housed at the Southwest National Primate Research Center, Texas Biomedical Research Institute, San Antonio, TX. During data collection for this project, the subjects were singly housed, due to the inability to house individuals with compatible partners. Steps were taken to minimize the effects of single housing and included (a) placement of all subjects in the same room, thereby allowing individuals visual, auditory and olfactory contact with others; (b) nest boxes in each cage to allow the individual to remove himself from view; and (c) extensive mesh and other surfaces on and within each cage, to provide surfaces for vertical clinging and other loco motor activities. Room temperatures ranged between 76 and 84 °F (set point of 80 °F), with a 12 h light-dark cycle with lights off at 19:00. Fresh food was available ad libitum; the base diet consisted of a purified diet (Harlan Teklad TD130059 PWD) and Mazuri diet (AVP Callitrichid 5LK6). Animals also received small amounts of fresh fruits, seeds or dairy products daily as enrichment. Dietary, nutritional and husbandry specifics for these subjects followed those outlined in Layne and Power (2003). This research was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Texas Biomedical Research Institute and abided by all applicable U.S. Federal laws governing research with nonhuman primates.

2.2.Procedure

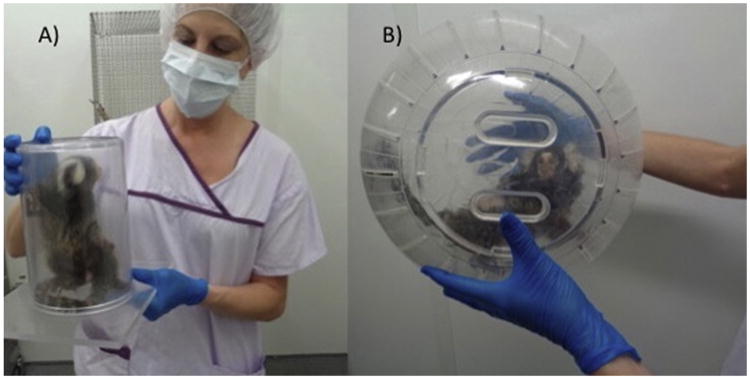

In order to reduce the stress of handling, 4 weeks were spent habituating the marmosets to the experimenters and to generalized laboratory procedures, including capture into a container for weighing and transport; and general familiarity with the exercise ball. A 15.24 cm diameter plastic cylinder (17.78 cm in height) was used to capture the subject. Holes were drilled into the bottom of the cylinder to provide ventilation. Standard operant conditioning principles were used to habituate the subject to the cylinder, and then to the capture process. A plexiglass sheet was placed over the cylinder opening once the subject was captured to prevent escape (see Fig. 1a). Subjects readily habituated to this process; most individuals willingly entered the capture container after a few weeks of training. Once secure in the cylinder, the marmoset was weighed on a scale. Subjects were captured and weighed daily. Weight of the subject was used as an indicator of stress.

Fig. 1.

(a) A marmoset securely contained in the clear plastic capture container. (b) A marmoset in the exercise ball, ready to engage in treadmill running. The backs of subjects were shaved in order to facilitate viewing of the identification tattoo.

Subjects were then transferred from the capture container into a large (31.75 cm diameter), transparent rodent exercise ball (Lee's Aquarium Giant Kritter Krawler, PetCo.com; see Fig. 1b). As being in a ball, wherein movement was dependent upon the subject, was a new and potentially stressful experience, we allowed subjects to habituate to the ball in their home room. They were allowed to move the ball across the floor for 1–3 min. We repeated this process daily for 5 days, allowing the subject to acclimate to the exercise ball and its movement. Subjects received a preferred food reward after each session.

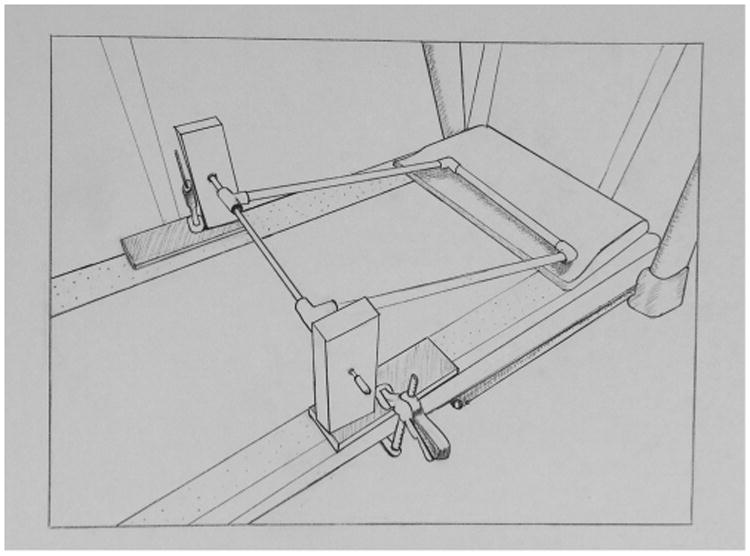

Subjects were transported to another room in the exercise ball for the exercise session. We used a standard human treadmill (NordicTrak Treadmill C600 2.6 CHP). Speeds were adjustable from 0.5 to 10 mph with increments of 0.1 mph; the running surface could be inclined to 10% though it was kept at a 0% grade. A simple rectangular frame, constructed of PVC, was secured to the treadmill therein ensuring the exercise ball remained on the treadmill during operation (see Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the rectangular frame, constructed of PVC, that was secured to the treadmill to secure the exercise ball on the treadmill during operation. Illustration by M. Karen Hambright.

Fig. 3.

Still image of marmoset in exercise ball on treadmill. On the online version this is an approximate 90s video showing a marmoset running on the treadmill

Subjects were next placed on the treadmill, starting off at the lowest speed (0.5 mph). The treadmill training protocol was designed to train the marmoset to run faster and longer over a period of time. The speed of the treadmill and time spent on the treadmill were gradually increased, beginning with 0.5 mph and 5 min, to a maximum speed of 1.0 mph and 5 min. Speed was increased over sessions by increments of 0.1 mph, until the target speed of 1.0 mph was attained. The maximum speed was selected based upon two factors. First, this speed is just below the average walking speed recorded by Schmitt (2003). Second, at this speed the subjects were able to maintain a consistent locomotion pattern without overt behavioral distress.

Subjects were observed while on the treadmill to monitor for signs of exhaustion or anxiety such as distress vocalizations. At the end of the exercise session, the subject was returned to its home cage directly from the exercise ball and given preferred foods. Subjects were observed after returning to their cage; their behavior was similar prior to testing. No signs of distress, anxiety or exhaustion were apparent. The treadmill and exercise ball were cleaned with a mild solution of disinfectant and water.

We spent 4 weeks habituating the marmosets to these procedures and training them to run on the treadmill in the MEB for 5 min. Table 1 illustrates the timeline for the above-described acclimation period.

Table 1.

Timeline for training subjects to the MEB (marmoset exercise ball) paradigm.

| Milestone | Days needed to move to next step | Behavioral criterion | Time per animal, per day (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Habituation to experimenter | 7 | Subject would take treats directly from the experimenter, not move away when cage door opened and hand entered | 15–25 |

| Habituation to cylinder | 16 | Subject would sit in corner or remain on perch, calmly wait for cylinder to envelop him | 10–20 |

| Habituation to the ball | 5 | Subject moved in the exercise ball, at their own speed, for,3 full minutes | 1–3 |

After the 4 week acclimation period the 12 marmosets were randomly assigned to two groups. Six marmosets engaged in treadmill running 3 days per week for 3 months; six marmosets received no further exercise training. For those subjects that engaged in treadmill running, once they had completed a session at 1.0 mph for 5 min, the duration was increased 5 min a session until reaching the maximum 30 min. Each subject was carefully monitored to ensure the animal was not undergoing physiological or psychological stress (labored breathing, dragging of hind limbs, etc.). In the absence of such signs, the duration was gradually increased to 30 min.

3. Results

All subjects responded to exercise acclimation in a similar fashion. All six subjects who were in the treadmill running condition were able to achieve the maximum speed and duration within 2 weeks of training (following acclimation to the exercise ball). After an additional 2 weeks of treadmill running at 1.0 mph and 30 min duration, the speed was increased to 1.2 mph over a two-day period. While it is possible that the subjects could have reached higher speeds, or a longer duration, we did not want to exercise them to exhaustion. To illustrate the exercise set-up, a video component is available and accompanies the electronic version of this manuscript. To access this video component, simply click on the image visible below (online version only).

Overall, subjects tolerated the procedure. One subject vomited in the exercise ball during the initial acclimation process (while still in the home room). This subject was immediately returned to its cage, and monitored for signs of illness and anxiety. This subject was given one day off from being placed in the exercise ball, during which time he exhibited no further signs of illness or distress. The subject was placed in the exercise ball for acclimation two days later; he showed no signs of anxiety or distress and did not vomit again. One subject in the treadmill running group died during week 11 of the study, for reasons not related to exercise.

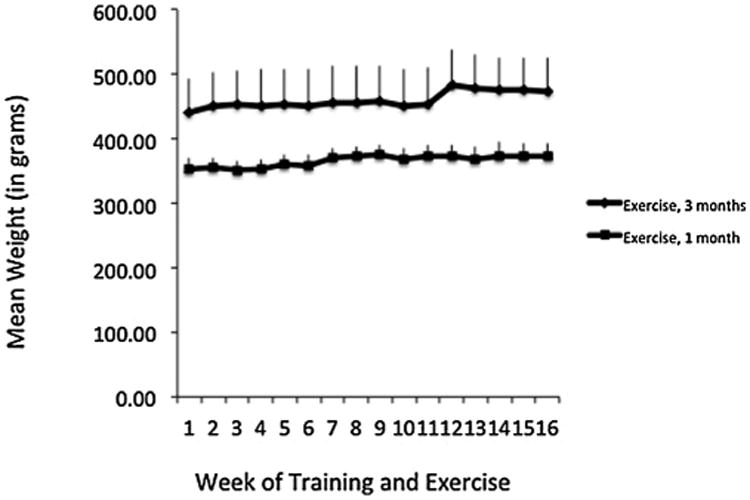

Weight data across the training period provide important information as to the stress of the subjects during this training period. We performed a mixed-model ANOVA, with exercise condition as the between-subjects variable and weight (weekly average) as the within-subjects variable. Alpha was set at P = 0.05. While subjects in the exercise group had a higher mean weight throughout the study than the marmosets that did not continue to exercise after the acclimation period, individual weights in that group also showed a large range (303–578 g). Thus, weights did not differ significantly throughout the study between the treadmill running group and those marmosets that did not continue to exercise after the acclimation period (F (1,9) = 1.92, p = 0.199).

As can be seen in Fig. 4, mean weights did not decrease in either group throughout the study.

Fig. 4.

Mean weights of marmosets throughout the acclimation (weeks 1–4) and exercise (weeks 5–16) sessions. While subjects in the exercise group had a higher mean weight throughout the study than the marmosets that did not continue to exercise after the acclimation period, individual weights in that group also showed a large range (303–578 g).

In fact, there was a significant interaction between exercise group and week, such that those subjects that exercised for 3 months showed a slight, though significant weight gain throughout the experiment (F(15,135) = 1.79, p < 0.05; partial eta2 = 0.17).

Defecation rates provide an additional indicator of stress; defecation rates were consistently low throughout exercise acclimation and treadmill running. Two subjects defecated in the exercise ball on the first day of exercise acclimation, and one subject defecated once during treadmill running. No other defecations occurred while in the exercise ball.

4. Discussion

We successfully trained 12 male marmosets to the MEB for treadmill running. The entire process – from training subjects to enter a clear plastic capture container to running at speeds of 1.2 mph for 30 min duration – was accomplished with daily sessions (including weekends) in 4 weeks. Furthermore, marmosets were able to maintain this rate of exercise for 3 days per week for 3 months. Our use of positive reinforcement techniques to train the marmosets to this procedure provided a safe environment for both marmoset and experimenter. Alternative procedures, such as putting a harness on the marmoset and tethering him to the treadmill for exercise, could potentially be unsafe particularly when putting the marmoset in a harness which increases handling time and increases biting risk.

Schmitt (2003) studying the kinematics and kinetics of walking gaits in the common marmoset, reported marmosets rarely walk, preferring to bound or gallop. Analyzing walking gaits, he concluded marmosets engage in a small range of speed, and travel at average speed of 0.66 m/s (±0.19), approximately 1.48 miles per hour. In the present study, marmosets engaged in both walking and bounding while in the exercise ball. After training, speeds ranged from 0.8 to 1.2 mph, which is below the average speed reported by Schmitt (2003). The goal of the present study was to have marmosets engage moderate-intensity exercise for an extended duration. We did not run the marmosets to exhaustion or induce stress with high speeds—both commonly used techniques in rodent exercise studies (American Physiological Society, 2006).

A major advantage of this exercise paradigm is that while it is technically forced exercise, it did not appear to induce stress in the marmosets. This is based on the observed stability (and slight increase) in bodyweight over the course of the study, and subjective behavioral observations before, during and after exercise. Additionally, defecation while in the exercise ball was minimal; marmosets are particularly susceptible to diarrhea and loose stool during environmental challenges (Morin, 1985). While we did not measure lean/fat mass, the fact that only those marmosets that engaged in treadmill running for 3 months showed significant weight gain suggests that it was due to an increase in lean mass associated with exercise. While the weight gain could be due to an increase in appetite post-exercise, evidence indicates that in both model animals and humans, energy intake (eating more) does increase somewhat after exercise but that it does not overcompensate for the calories burned while exercising (King, 1999).

All current forced exercise paradigms have an inherent tradeoff between the advantage of having complete control over the subjects' exercise routine and the disadvantage of inducing stress, which yield increased glucocorticoid levels, as well as decreased neurotrophin expression and overall health (Klaren et al, 2014). While it has yet to be determined whether or not this paradigm significantly alters glucocorticoid levels from baseline, our observations thus far suggest that this novel forced exercise method may provide the advantages of exercise routine without the traditionally concomitant activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. However, future research needs to incorporate behavioral and physiological measures to confirm that this method does not produce significant stress.

The main potential limitation with exercise training and testing is time, as this process is labor intensive. We worked with each marmoset 5 days/week, for one month, habituating and training to the capture and exercise paradigms. Maintaining the exercise then occurred 3 days each week for 3 months. We believe that the gradual acclimation to the experimental procedures, including capture training, habituation to the exercise ball, and gradual increase in running speed and duration—was essential to the success of the paradigm. Furthermore, the habituation and training occurred over a condensed time period, with consistent staff and procedures throughout. Thus, the procedures became quite routine and further minimized potential stress for the marmosets. We should note that only male marmosets were used in this study; female marmosets might respond differently to these procedures. While we acknowledge this procedure requires a significant time investment (though less than some others), we argue that the time invested is well worth the gains of this safe, highly controlled, minimally stressful paradigm for those interested in conducting exercise physiology studies in marmoset models.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) are valuable models in neuroscience research.

We report a reliable technique for engaging marmosets in aerobic exercise.

Marmosets ran on treadmills for 30 min a day, 3 days a week for 3 months.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Pilot Research Program at the Southwest National Primate Research Center (NIH grant P51 OD011133) to KAP. We thank the animal care staff, particularly Theresa Valverde and Donna Layne.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.03.023.

References

- Al-Jarrah M, Jamous M, Al Zailaey K, Bweir SO. Endurance exercise training promotes angiogenesis in the brain of chronic/progressive mouse model of Parkinson's disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2010;26:369–73. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2010-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Physiological Society. Resource book for the design of animal exercise protocols. American Physiological Society; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, Green PS, Wilkinson CW, McTiernan A, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on ild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:71–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadet P, Zhu W, Mantione K, Rymer M, Dardik I, Reisman S, et al. Cyclic exercise induces anti-inflammatory signal molecule increases in the plasma of Parkinson's patients. Int J Mol Med. 2003;12:485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman SB, Aslan S, Spence JS, DeFina LF, Keebler MW, Didehbani N, et al. Shorter term aerobic exercise improves brain, cognition, and cardiovascular fitness in aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00075. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2013.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Curran CR, Wiegel WR, Stevens DN. Design and operation of an exercise device for subhuman primates (TN-72-1) Bethesda, MD: Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. PNAS. 2011;108(7):3017–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons TE, Pence BD, Petr G, Ossyra JM, Mach HC, Battacharya TK, et al. Voluntary wheel-running, but not a diet containing (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and beta-alanine, improves learning, memory and hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. Behav Brain Res. 2014;272:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisolfi CV, Mora F, Nattermann R, Myers RD. New apparatus for exercising a monkey seated in a primate chair. J Appl Physiol. 1978;44(1):129–32. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King NA. What processes are involved in the appetite response to moderate increases in exercise-induced energy expenditure? Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58(1):107–13. doi: 10.1079/pns19990015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaren RE, Motl RW, Woods JA, Miller SD. Effects of exercise in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (an animal model of multiple sclerosis) J Neuroimmunol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.06.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/jjneuroim.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Layne DG, Power RA. Husbandry, handling, and nutrition for marmosets. Comp Med. 2003;53:351–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield K. Marmoset models commonly used in biomedical research. Comp Med. 2003;53(4):383–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley J, Buchanan-Smith HM, Bassett L, Morris K. Training common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) to cooperate during routine laboratory procedures: ease of training and time investment. J Appl Anim Welfare Sci. 2003;6:209–20. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0603_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin M. Colony management problems encountered in using marmosets and tamarins in biomedical research. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30(12):14S–6S. doi: 10.1007/BF01296966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers RD, Gisolfi CV, Mora F. Role of brain Ca2+ in central control of body temperature during exercise in the monkey. J Appl Physiol. 1977;43:689–94. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.43.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M, Xu P, Glazko G. Estimation of divergence times from multiprotein sequences for a few mammalian species and several distantly related organisms. PNAS. 2001;98(5):2497–502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051611498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips KA, Bales KL, Capitanio JC, Conley A, Czoty P, 't Hart BA, et al. Why primate models matter. Am J Primatol. 2014;76:801–27. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichlen DA, Polk JD. Linking brains and brawn: exercise and the evolution of human neurobiology. Proc R Soc London, Ser B: Biol Sci. 2013;280:20122250. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhyu IJ, Bytheway JA, Kohler SJ, Lange H, Lee KJ, Boklewski J, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise training on cognitive function and cortical vascularity in monkeys. NeuroScience. 2010;167(4):1239–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertshaw DC, Taylor CR, Mazzia LM. Sweating in primates: secretion by adrenal medulla during exercise. Am J Physiol. 1973;224:678–81. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.3.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D. Evolutionary implications of the unusual walking mechanics of the common marmoset (C. jacchus) Am J Phys Anthropol. 2003;122:28–37. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry CJ, Constable SH. An automated exercise wheel for primates. Behavior Res Methods, Instrum Comput. 1992;24:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B, Winter C, Hosman K, Siebert E, Kempermann G, Petrus DS, et al. Enriched environment induces cellular plasticity in the adult substantia nigra and improves motor behavior function in the 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2006;199(2):291–300. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiper ME, Young NM. Primate molecular divergence dates. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;41:384–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajiri N, Yasuhara T, Shingo T, Kondo A, Yuan W, Kadota T, et al. Exercise exerts neuroprotective effects on Parkinson's disease model of rats. Brain Res. 2010;1310:200–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif SD, Mansfield KG, Ratnam R, Ross CN, Ziegler TE. The marmoset as a model of aging and age-related diseases. ILARJ. 2011;52(1):54–65. doi: 10.1093/ilar.52.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NI, Helmreich DL, Parfitt DB, Caston-Balderrama A, Cameron JL. Evidence for a causal role of low energy availability in the induction of menstrual cycle disturbances during strenuous exercise training. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(11):5184–93. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.11.8024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.