Abstract

Though the steps of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 virion maturation are well documented, the mechanisms regulating the proteolysis of the Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol polyproteins by the HIV-1 protease (PR) remain obscure. One proposed mechanism argues that the maturation intermediate p15NC must interact with RNA for efficient cleavage by the PR. We investigated this phenomenon and found processing of multiple substrates by the HIV-1 PR was enhanced in the presence of RNA. The acceleration of proteolysis occurred independently from the substrate's ability to interact with nucleic acid, indicating that a direct interaction between substrate and RNA is not necessary for enhancement. Gel-shift assays demonstrated the HIV-1 PR is capable of interacting with nucleic acids, suggesting RNA accelerates processing reactions by interacting with the PR rather than the substrate. All HIV-1 PRs examined have this ability; however, the HIV-2 PR does not interact with RNA, and does not exhibit enhanced catalytic activity in the presence of RNA. No specific sequence or structure was required in the RNA for a productive interaction with the HIV-1 PR, which appears to be principally, though not exclusively, driven by electrostatic forces. For a peptide substrate, RNA increased the kinetic efficiency of the HIV-1 PR by an order of magnitude, affecting both the turnover rate (kcat) and substrate affinity (Km). These results suggest an allosteric binding site exists on the HIV-1 PR, and that HIV-1 PR activity during maturation could be regulated in part by the juxtaposition of the enzyme with virion-packaged RNA.

Keywords: Gag, Maturation, p15NC, Protease, Allosteric Binding Site

Graphical abstract

Introduction

For the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 to spread from cell-to-cell the virus must assemble a particle capable of leaving its host cell without re-infecting the same cell. HIV-1 accomplishes this by constructing the virion as a rigid [1], non-infectious entity [2], and then later converting the particle into a mature, infectious form [3]. The timing of this transfiguration is critical for viral infectivity since prematurely initiating [4, 5] or slowing the kinetics of maturation by reducing the number of active HIV-1 protease (PR) molecules [6-8] both disrupt the production of infectious viruses. This, therefore, requires the virus to employ regulatory mechanisms that manage the assembly, release, and maturation steps of the virus lifecycle. Many of these mechanisms concern the activity of the HIV-1 PR.

During assembly HIV-1 particles consist of two structural polyproteins, Gag and GagPro-Pol. Both share the same first four domains – matrix (MA), capsid (CA), spacer peptide 1 (SP1), and nucleocapsid (NC) – but differ in having either a second spacer peptide (SP2) and a domain called p6 (in Gag) or a transframe domain and monomers of the viral enzymes PR, reverse transcriptase, and integrase (in Gag-Pro-Pol). The mass assembly of these proteins on the plasma membrane triggers the budding process, which is completed with the help of the host endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery [9]. It is then, concurrent to or immediately after budding, that the HIV-1 PR activates to begin the maturation step of the lifecycle [3].

The HIV-1 PR is a dimer of two identical subunits [10-12], necessitating an interaction between a pair of Gag-Pro-Pol molecules to create the active site of the enzyme. The low stability of this interaction [13, 14] and accompanying poor catalytic activity [14, 15] restrict PR activation to budding or budded virions, where a high local concentration of Gag-Pro-Pol provides conditions that favor dimerization. The embedded PR overcomes its limited functionality through a series of intramolecular cleavage events that free the N termini of the monomers [14, 16-19], thereby producing a much more stable enzyme capable of completing intermolecular cleavage events [17, 20, 21]. The mature enzyme then proceeds to cleave the remaining structural polyproteins in a step-wise process that must go to near completion [22-24]. Even modest under-processing at most sites can result in a non-infectious virus particle [6-8, 25-27].

Additional regulatory mechanisms exist to control the order and rate of Gag and GagPro-Pol processing. Principally, the cleavage rate is regulated at the level of the processing site amino acid sequence. Each site has a unique sequence, with no obvious pattern connecting them [28]. Instead, all the sites can occupy a conformation that fits into the conserved shape, i.e. substrate envelope, recognized by the HIV-1 PR [29, 30]. The ability of each site to fill that space therefore defines a key determinant of processing order and rate. For instance, the two processing sites that are cleaved last, CA/SP1 and NC/SP2, are the most dynamic sites, suggesting they frequently shift in and out of conformations that do not mimic the substrate envelope [29]. This structural plasticity makes them more difficult to cleave. Secondarily, the rate of cleavage for the CA/SP1, SP2/p6, and SP1/NC processing sites also may exhibit some dependence on contextual determinants [31-33].

A role for RNA as a cofactor has also been suggested. Maturation generates an intermediate called p15NC, which is comprised of the NC, SP2, and p6 domains of Gag. The next step of processing requires cleavage at the SP2/p6 site, but this does not readily occur in the absence of RNA when examined in vitro [34-36]. In the presence of RNA, (or select DNA oligonucleotides), the rate of processing by the HIV-1 PR dramatically increases. In contrast, the cleavage rate of a truncated MA/CA substrate remained unaffected after the removal of RNA from the reaction system [35]. Since p15NC contains the principal viral RNA-binding protein, a mechanism was proposed in which an interaction between RNA and p15NC induces a conformational change in the protein that exposes a buried cleavage site, and/or stabilizes the conformation of the SP2/p6 site to make it a more suitable substrate [35]. In agreement with this hypothesis, the SP2/p6 site is one of the more dynamic cleavage sites, behind only CA/SP1 and NC/SP2 [29]. Given the close proximity of the SP1/NC site to the RNA-binding domains, such a mechanism might also affect SP1/NC processing. Consistent with this, a 30-mer single-stranded DNA molecule was recently shown to increase the rate of SP1/NC processing within a truncated Gag polyprotein [31].

In an effort to study RNA-dependent processing, we established a two-substrate proteolysis system in which cleavage of the p15NC protein by the PR could be measured in tandem to the rate of cleavage of an internal control protein that was purportedly unaffected by nucleic acid. Contrary to prior results, we found both substrates exhibited an increased processing rate in the presence of RNA. Additional single-substrate assays with globular and peptide substrates demonstrated that RNA enhances processing in a substrate-independent manner. This led us to hypothesize that the critical interaction occurs between RNA and the HIV-1 PR, an interaction substantiated with a gel-shift assay. Examination of a panel of HIV-1 PRs demonstrated that this enzyme-RNA interaction is conserved across multiple subtypes, as well as in patient-derived drug-resistant enzymes. In contrast, the HIV-2 PR does not interact with RNA, and does not cleave its substrates more efficiently with RNA present. The interaction between the HIV-1 PR and RNA is primarily electrostatic in nature, although sequence and structural determinants within the polyanion may also play a role. Use of a tethered dimer of the HIV-1 PR revealed RNA-enhanced cleavage does not result from increased dimer stability. While the exact mechanism of enhancement has not yet been identified, we did determine that RNA affects both the Km and kcat. These findings support the existence of an allosteric binding site on the HIV-1 PR, and raise the possibility that PR activity during assembly could be regulated in part by the juxtaposition of the PR and virion-packaged RNA.

Results

Multiple substrates of the HIV-1 PR exhibit an enhanced rate of proteolysis in the presence of RNA

We first documented a two-substrate protease assay where the rate of p15NC processing could be measured relative to an internal control protein. To demonstrate that we could independently measure multiple substrates in a single reaction, we performed a time-course experiment with two substrates containing the canonical MA/CA cleavage site. One substrate consisted of the entirety of the MA and CA domains (MA/CA); the other substrate had a GST-tag fused to the N terminus of MA and a CA region truncated at amino acid 145 [32] (GMCΔ). This truncation occurred between the N- and C-terminal domains of CA, which exist as two separate domains [37, 38], ostensibly leaving the conformation of the MA/CA cleavage site unaffected. In addition, these N- and C-terminal changes allowed the two forms of MA/CA to migrate to different positions in a polyacrylamide gel in both the uncleaved and the cleaved states (Figure 1a). As we have observed previously [26], both substrates were processed in parallel and at nearly identical rates (Figure 1a and 1b). Thus, the two-substrate system enables the direct comparison of relative rates of cleavage by the HIV-1 protease using pairs of protein substrates. For this analysis we have relied on coomassie staining of the proteins and the disappearance of substrate over time to provide flexibility in the types of proteins that can be analyzed.

Figure 1.

Concomitant processing of multiple substrates by the HIV-1 protease. (a) A reaction mixture containing the MA/CA (solid triangle) and GMCΔ (open triangle) substrates in equimolar amounts was incubated at 30°C, pH 6.5 for 1 hour prior to the addition of the HIV-1 PR. Reactions were run for 10 minutes with the intermittent removal of aliquots that were immediately mixed with SDS to halt the reaction. Reaction substrates and products were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained by coomassie. MA/CA products are indicated with solid, reversed triangles; GMCΔ products with open, reversed triangles. (b) MA/CA (circle) and GMCΔ (square) bands were quantified with imaging software and graphed as substrate remaining versus time. (c) Reactions containing MA/CA (solid triangle) and p15NC (open triangle) in a molar ratio of 1:4 were performed as in Figure 1a, +/- 150 nM of a heteropolymeric 532-nucleotide RNA derived from the p15NC region of the HIV-1 NL4-3 genome. (d) Quantification of MA/CA (black circle) and p15NC (grey square) two-substrate assays. Dashed lines show reactions without RNA; reactions with RNA are represented with solid lines. All errors bars represent the standard deviation resulting from three independent experiments.

We sought to determine whether we could observe RNA-dependent rate enhancement of p15NC cleavage by substituting p15NC into the reaction system for the GMCΔ protein. Due to the poor staining profile of p15NC, its final concentration in the reaction was four-fold higher than that of the MA/CA substrate. In the absence of RNA (Figure 1c, left panel), cleavage of both MA/CA and p15NC was observed. Additional reactions performed with or without nuclease pre-treatment were indistinguishable (data not shown), affirming that these reactions were devoid of RNA. The percent substrate remaining was quantified by densitometry and plotted as a function of time (Figure 1d, dashed lines). Product formation for MA/CA was easily observable, however we could not unequivocally identify the products of p15NC cleavage. One stained poorly, and the other product ran to the same location on the gel as a contaminant remaining after protein purification. To confirm the 25% drop in p15NC band intensity we observed was in fact processing of the p15NC substrate by the HIV-1 PR, we performed the reaction in the absence of PR and found that there was no observable change in either substrate (data not shown), suggesting the decrease in p15NC band intensity was due to PR cleavage. Thus, in this system, the MA/CA protein was processed approximately 2.5-fold faster than p15NC in the absence of RNA.

When we performed the two-substrate reaction in the presence of long, heteropolymeric RNA, a 532-base transcript derived from the p15NC region of the HIV-1 genome, we found the rate of substrate disappearance accelerated for both substrates (Figure 1c and 1d). This result contradicts previously published work that found MA/CA cleavage unaffected by the presence of nucleic acid [31, 35]. Nonetheless, we consistently observed a 15-fold increase in the rate of p15NC cleavage in concert with an 8-fold increase in the rate of MA/CA processing. Our results argue that substrates that do not contain NC can also exhibit an enhanced rate of cleavage in the presence of RNA.

RNA-dependent rate enhancement is a substrate-independent phenomenon

In order to confirm that RNA-dependent enhancement of MA/CA cleavage occurs independently of p15NC, we performed single-substrate proteolysis assays in the presence and absence of RNA. In our single-substrate assays, the MA/CA protein was labeled with the Lumio Green Reagent after mutagenesis of the Cyclophilin A loop in CA to create a fluor binding site [26]. This label binds with high specificity and in a one-to-one molar ratio with the substrate, allowing specific and more sensitive detection of the substrate and the CA product compared to the coomassie stain (Figure 2a). As a result, we could reliably determine the percent product formed (Intensity of CA band × 100% ÷ total fluorescence intensity of all bands in the lane), greatly increasing the accuracy of our data collection. Unfortunately, the label could not be used with the p15NC substrate because the zinc-finger domains in p15NC also bind to the Lumio Green Reagent. With this assay, we could accurately determine changes in the MA/CA cleavage rate of up to 40-fold. However, when comparing the no-RNA to plus-RNA reactions, we detected a fold enhancement beyond that value. Therefore, we only estimate the rate of MA/CA cleavage as 80- to 90-fold faster in the presence of RNA (Figure 2b). The magnitude by which MA/CA cleavage was accelerated in single substrate assays was considerably greater than in the two-substrate assay. Several explanations likely account for this discrepancy: the increased sensitivity of the fluorescence-based assay allowed more precise determination of reaction progress while under near steady-state conditions; the potential presence of multiple RNA-binding proteins in the two-substrate assay meant there was competition for RNA, which limited the effect; and, owing to an inability to purify p15NC to high concentrations, the ionic strength of the two-substrate assay was likely higher than anticipated due to a substantially larger contribution of protein storage buffer to the reaction mixture. Notably, raising the ionic strength of the reaction by increasing the salt concentration drastically reduces the magnitude of the RNA-enhancement effect [39], even in single-substrate MA/CA assays (see below).

Figure 2.

RNA accelerates processing independent of the ability of MA/CA to bind nucleic acid. (a) MA/CA proteins were tagged with the Lumio Green Reagent via mutation of the Cyclophilin A binding loop in CA to include a CCPGCC motif. Single-substrate MA/CA proteolysis assays were visualized by coomassie (left) and fluorescence (right). Only CA-containing reactant and product species are present in the fluorescence stain. (b) Reaction progress curves for single-substrate MA/CA (black) and MA/CA-AAA (grey) proteolysis reactions performed in the absence (dashed lines) and presence (solid lines) of RNA. (c) and (d) Binding reactions containing 100 ng (2 μM) of the single-stranded DNA molecule ODN17 and steadily increasing amounts (from 0 μM in lane 1 to 12 μM in lane 9) of MA/CA (c) or MA/CA-AAA (d) were electrophoresed in a 6% polyacrylamide gel under native conditions. Gels were stained with SYBR Gold (left panel) to visualize nucleic acid species. The gels were then washed and restained with SYPRO Ruby (central panel) to view protein. The intensity of each nucleic acid species relative to the respective band in the no-protein reaction (lane 1) was determined by densitometry and plotted as a function of protein:ODN17 concentration (right panel). All errors bars represent the standard deviation resulting from three independent experiments.

Since MA/CA also exhibited RNA-dependent enhancement, we considered the possibility that this effect resulted from an interaction between MA/CA and RNA. MA contains a highly basic region on the globular head of the protein capable of binding nucleic acid [40-44]. Because the RNA species used in prior experiments was a 532-base transcript derived from the p15NC region of the HIV-1 genome, it was poorly suited for use in a gel-shift assay. To identify a surrogate nucleic acid, we tested the ability of two short ssDNA oligonucleotides, N5 (21 bases) and ODN17 (17 bases), to accelerate MA/CA processing. Both molecules had previously been reported to enhance p15NC processing similarly to RNA, although not as potently [34, 36]. In agreement with previous reports, both N5 and ODN17 increased the rate of processing, but to a much lower degree than RNA (Supplementary Figure 1).

Using ODN17, we performed a gel-shift assay to determine the ability of MA/CA to bind to nucleic acid. Under native conditions, ODN17 runs as two species (Figure 2c, left panel); presumably, the lower species corresponds to single-stranded molecules, while the upper band may represent a G-quadruplex structure that ODN17 has the potential to form [34, 45]. In concert with the addition of increasing amounts of MA/CA to the binding reactions, (from 0 μM in lane 1 to 12 μM in lane 9), both the upper and lower bands progressively diminished (Figure 2c, right panel), and a new band appeared toward the top of the gel. The new band overlaps with where the MA/CA protein runs (Figure 2c, center panel), signifying that the MA/CA protein interacts with nucleic acid.

Addressing the question of whether this interaction was required for the enhanced rate of MA/CA processing, we replaced the lysines in the K26KQYK30 sequence of MA with alanines to generate the mutant protein MA/CA-AAA. In a previous report, mutating these lysines disrupted the residual RNA-binding ability of Gag molecules whose NC domain had been deleted [43]. Consistent with those results, MA/CA-AAA was severely attenuated in its ability to interact with ODN17 (Figure 2d). If an interaction between MA/CA and nucleic acid was responsible for its increased cleavage rate, then we should have found enhanced processing of MA/CA-AAA to be considerably reduced or nonexistent. However, RNA-dependent enhancement of MA/CA-AAA processing still occurred, and at a nearly identical magnitude (Figure 2b, gray lines). These results suggest that RNA-dependent enhancement is independent of the substrate.

In order to confirm the lack of requirement for an interaction between substrate and RNA, we performed proteolysis assays utilizing a 12-amino acid peptide as the substrate. The HIV Protease Substrate 1 (Sigma) is a fluorogenic substrate too small to interact with RNA and simultaneously be cleaved by the HIV-1 PR; conveniently, this peptide also contains the same cleavage site sequence as the MA/CA protein. Adding RNA to the peptide proteolysis reaction still accelerated the rate of the reaction, though only by 20-fold (Figure 3). Differences in reaction conditions for the peptide (i.e. pH), and/or the absence of contextual determinants could account for the reduced magnitude of the effect relative to the globular MA/CA substrate. Nonetheless, the results of the peptide assay show that the increased reaction rate observed upon addition of RNA is independent of the substrate.

Figure 3.

The addition of RNA to a reaction accelerates processing of a peptide substrate. A commercially available 12-amino acid peptide substrate was utilized as a substrate for the HIV-1 PR. Processing of the peptide substrate was monitored by an increase in fluorescence resulting from the separation of a fluorophore from a quencher placed on opposing ends of the peptide. Reactions were run at 30°C, pH 4.8, and performed in the absence (grey) or presence (black) of long, heteropolymeric RNA. All errors bars represent the standard deviation resulting from three independent experiments.

The HIV-1 PR can directly interact with nucleic acid

Since an interaction between RNA and substrate is not the mechanism driving RNA-dependent enhancement, we hypothesized that an interaction was occurring between RNA and the HIV-1 PR. We again used ODN17 as a surrogate for RNA-binding, and performed gel-shift assays utilizing the HIV-1 PR as the protein in each binding reaction. Similar to the wild-type MA/CA protein, adding progressively more PR resulted in the disappearance of the upper oligonucleotide band (Figure 4, left panel). In this case the fluorescence intensity of the lower band remained relatively unchanged regardless of the amount of PR present in the binding reaction. Under native conditions, the HIV-1 PR does not enter the gel, likely because of its basic profile (HIV-1 PR has an isoelectric point of 9.1), so there is no overt overlapping band in both stains. Nonetheless, we infer the presence of a PR-ODN17 complex from the selective loss of the upper oligonucleotide band and a low level of fluorescence in the wells of the central lanes of both SYBR gold and SYPRO ruby stains. The fluorescence may disappear from the latter wells because the addition of more HIV-1 PR increases the net charge of the PR-ODN17 complexes so that the complexes flow into the running buffer rather than remain in the well. From this, we conclude that the HIV-1 PR can directly interact with nucleic acids.

Figure 4.

The HIV-1 PR can directly interact with nucleic acid. Binding reactions containing 100 ng of ODN17 (2 μM) and steadily increasing amounts (from 0 μM in lane 1 to 12 μM in lane 9) of the HIV-1 PR were electrophoresed in a 6% polyacrylamide gel under native conditions. As previously, gels were stained with SYBR Gold (top left) to visualize the nucleic acid species followed by SYPRO Ruby (top right) for visualization of protein. The relative intensity of each nucleic acid species was determined by densitometry and plotted as a function of protein:ODN17 concentration (bottom). The HIV-1 PR does not enter the gel under native conditions because of its high isoelectric point (pI = 9.1). Complexes can be inferred from the low level fluorescence present in the wells of the central lanes and the selective depletion of the upper nucleic acid species. All errors bars represent the standard deviation resulting from three independent experiments.

RNA accelerates processing by HIV-1 PRs from multiple subtypes and from drug resistant variants, but not processing by HIV-2 PR

Given that we had only shown a single variant of a subtype B HIV-1 PR was capable of interacting with RNA to enhance its activity, we expanded our data set to include HIV-1 PRs of subtype C and CRF01_AE, as well as an HIV-2 PR (Supplementary Table 1). We also tested several patient-derived, drug-resistant subtype B PRs to determine whether the effect is maintained after significant changes to the amino acid sequence (19-26 substitutions from the PR of the SF2 isolate of HIV-1 subtype B used in the prior experiments). All three wild-type HIV-1 PRs exhibited a 100-fold or greater increase in the rate they processed the MA/CA protein in the presence of RNA relative to their respective no-RNA controls (Figure 5). The drug-resistant HIV-1 subtype B PRs likewise demonstrated enhanced catalytic activity in the presence of RNA, although there was considerably more variability in the magnitude of the effect for these enzymes. Despite the variability in magnitude, VSL23, the PR whose activity was least accelerated, still cleaved MA/CA 30-fold more quickly. The only enzyme entirely unaffected by the presence of RNA was the HIV-2 PR. For this latter assay the cleavage site of MA/CA was adapted to reflect the canonical site for HIV-2, allowing the substrate to be efficiently cleaved by the enzyme (data not shown). Consistent with these results, we found that the HIV-2 PR did not interact with nucleic acid in a gel-shift assay (Supplementary Figure 2; note the HIV-2 PR with its lower isoelectric point of 5.3 enters the gel). Both the PR-dependent variability in the magnitude of the effect, and the lack of enhancement for the HIV-2 PR further demonstrated that RNA-dependent enhancement results from an interaction between RNA and the HIV-1 PR rather than with the substrate.

Figure 5.

The rate of processing by multiple HIV-1 PRs, but not the HIV-2 PR, increases in the presence of RNA. The rate of MA/CA processing by HIV-1 PRs from three different subtypes and an HIV-2 PR were evaluated in the presence and absence of RNA. The MA/CA protein substrate for the HIV-2 PR was mutated at the processing site to better reflect the canonical HIV-2 MA/CA processing site. Five highly mutated drug-resistant HIV-1 subtype B PRs (SLK19, KY26, ATA21, VEG23, and VSL23) were also examined. Reactions were performed with the globular MA/CA substrate under standard conditions with the exception of PR concentration, which was adjusted on an enzyme-to-enzyme basis to achieve 10% cleavage over the course of the reaction in the absence of RNA. SLK19, KY26, and ATA21 required up to 4-fold higher concentrations; VEG23 and VSL23 were more severely attenuated, and required a 20-fold higher concentration of enzyme. Results are reported as the magnitude difference in acceleration of the RNA-plus reaction relative to each enzyme's respective no-RNA control. All errors bars represent the standard deviation resulting from three independent experiments.

Long, heteropolymeric RNA is the most effective enhancer of HIV-1 PR activity, but small ssDNA molecules and tRNA are still functional enhancers

Whereas MA/CA interacted with both the upper and lower ODN17 bands in the gel-shift assay, the HIV-1 PR demonstrated a selective interaction with only the upper ODN17 species. Additionally, ODN17 and N5 were considerably less potent enhancers than p15 RNA, requiring much higher concentrations to be effective in our earlier assays. These data raised the possibility that a specific interaction might occur between enzyme and nucleic acid, which was fulfilled much more capably by some component of the p15 RNA transcript used in our assays. To determine whether p15 RNA contains some specific feature required for an interaction between the HIV-1 PR and nucleic acid, we generated dose-response curves for multiple different RNA transcripts, yeast tRNA, and the N5 and ODN17 single-stranded DNA molecules. All long (>400 bases), heteropolymeric RNAs accelerated the reaction equivalently (Figure 6a), including transcripts that were not derived from the HIV-1 genome (data not shown). The long RNAs also had very similar EC50 values (Table 1) that were even closer to identical when adjusted for length (EC50/nt). Even though N5 and ODN17 were roughly one-tenth as effective as long heteropolymeric RNA in the magnitude of the enhancement effect, both still accelerated MA/CA processing by about 10-fold. Though the EC50s of N5 and ODN17 were in the μM range, the EC50/nt were reasonably similar to those of long heteropolymeric RNA. Yeast tRNA grouped with the single-stranded DNA molecules regarding the magnitude of enhancement, but the EC50 value was nearer the RNA transcripts. Thus tRNA had the lowest EC50/nt, but this value was still only two-fold lower than most other nucleic acids. We conclude that long, heteropolymeric RNAs are the most potent enhancers of HIV-1 PR activity, but because all six nucleic acids tested had very similar EC50/nt, the amount of nucleic acid, rather than a specific sequence or structure, appears to be the critical determinant. However, this does not yet address why long heteropolymeric RNA was 10-fold more potent in the magnitude of enhancing HIV-1 PR activity than the other nucleic acids (i.e. 100-fold vs 10-fold enhancement), nor does it explain the selective binding of the oligonucleotides observed in the gel-shift assay.

Figure 6.

Multiple nucleic acid species can enhance HIV-1 PR activity, though potencies vary. (a) Dose response curves were generated for several long heteropolymeric RNAs, yeast tRNA, and the single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides N5 and ODN17. Reactions were performed under standard conditions using the MA/CA protein as the substrate. (b) 100 ng of the indicated single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides were electrophoresed in a 6% polyacrylamide gel under nondenaturing conditions, and then visualized with SYBR gold. The dashed white line distinguishes single-stranded species from oligomeric species. (c) Each single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide was supplied at a final concentration of 10 μM in MA/CA processing reactions and evaluated for its ability to improve HIV-1 PR function. Results are reported as the magnitude of acceleration relative to MA/CA processing in the absence of nucleic acid. All errors bars represent the standard deviation resulting from three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Length and efficacy of polyanions as enhancers of HIV-1 PR activity.

| Length (nt) | Max. Fold Acceleration | EC50 (nM) | EC50/nt (nt × 10ˆ18/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACA RNA | 1248 | 95 | 17 | 13 |

| p15 RNA | 532 | 92 | 38 | 12 |

| PR RNA | 436 | 82 | 43 | 11 |

| Yeast tRNA | 76-90 | 8.0 | 108-124 | 5.7 – 6.7 |

| N5 | 21 | 12 | 3229 | 41 |

| ODN17 | 17 | 7.3 | 1148 | 12 |

|

| ||||

| Heparin | --- | 30 | 175-195 | --- |

|

| ||||

| Poly(dA) | 49 | < 2 | --- | --- |

| Poly(dC) | 49 | 21 | 569 | 17 |

| Poly(dG) | 49 | 15 | 506 | 15 |

| Poly(dT) | 49 | 18 | 635 | 19 |

As a means of further investigating the apparent selectivity of the HIV-1 PR for the larger ODN17 species, as well as the discrepancy in the magnitude of the effect between long RNA transcripts and single-stranded DNA molecules, we increased our catalogue of oligonucleotides and tested each for their ability to enhance PR activity. Figure 6b and 6c contain the results from a selection of these molecules, all of which are between 17 and 21 nucleotides in length (Supplementary Table 2). Of the twelve molecules shown, six of them (ODN17, N5, N5cgmut, N10, G6A6C6, G6A12) enhanced the rate of the reaction by at least 5-fold (Figure 6c); the other six were ineffective even at concentrations exceeding 10 μM. Among the single-stranded DNA molecules capable of enhancing the reaction, all but the C-rich N10 molecule formed slower migrating species when electrophoresed through a 6% polyacrylamide gel (Figure 6b). However, we cannot definitively state whether N10 did or did not form a secondary species because the SYBR gold stain is much less effective at staining C-rich oligonucleotides (e.g. Figure 6b, C6A12), and C-rich nucleic acids are capable of forming higher order multimeric species [46]. With the possible exception of N10, these results are in accordance with the gel-shift assay where only the larger nucleic acid species interacted with the HIV-1 PR.

We also noticed a direct correlation between the migration distance in the gel, where observable, and the magnitude of the enhancer effect (Figure 6b and 6c). Preheating aliquots of the oligonucleotides before use confirmed the importance of these multimeric and/or structured species – only those whose slower migrating species remained after heating retained their enhancer activity (Supplementary Figure 3) – and also strengthened the correlation between migration pattern and effect magnitude. G6A6C6 lost one of its two larger species after heating, with the remaining band migrating to a position similar to the species present in the unheated N5 aliquots. The magnitude by which the heated G6A6C6 preparation enhanced HIV-1 PR activity resembled that of unheated N5, highlighting the proposed relationship. These data suggest that the interaction between the HIV-1 PR and nucleic acid is primarily electrostatic in nature, requiring a polyanion of some particular size or conformation rather than a specific sequence. Also, the potency of an enhancer's effect may be determined by the size and/or conformation of the molecule.

The interaction between the HIV-1 PR and nucleic acid is principally electrostatic, but additional factors affect the magnitude of enhancement

If the HIV-1 PR-RNA interaction is primarily electrostatic in nature, then a non-nucleic acid polyanion should be sufficient to enhance the enzyme's catalytic activity. To test this, we utilized heparin as the polyanion in single-substrate proteolysis assays and generated a dose-response curve (Figure 7a). As expected, heparin enhanced proteolysis, accelerating the rate of the reaction by up to 30-fold. This value put heparin squarely between long, heteropolymeric RNA and the short single-stranded DNA molecules in effectiveness. With the expected size of commercially produced heparin molecules to be 17-19 kDa, an equivalently sized molecule of RNA would be approximately 53-60 nucleotides. As this size fits between the HIV-1 RNA transcripts and the single-stranded DNA molecules, the magnitude of the effect remains consistent with the proposed relationship between size and effectiveness of the polyanion. We also tested a polycation spermine (Sigma) in our system, but it had no effect on HIV-1 or HIV-2 PR activity at all concentrations examined (data not shown). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that its ineffectiveness was the result of the small size of individual spermine molecules.

Figure 7.

A specific nucleic acid sequence or structure is not required for enhancement. Dose-response curves were generated under standard assay conditions for (a) heparin, and (b) deoxynucleotide homopolymers. Reactions were performed with the globular MA/CA substrate under standard conditions.

If an electrostatic interaction were sufficient, we hypothesized that homopolymers of each deoxynucleotide should be equally effective at accelerating the rate of proteolysis. We generated dose response curves for 49-mers of poly(dA), poly(dC), and poly(dT), (Figure 7b). Owing to synthesis constraints, the poly(dG) molecule contained an adenosine every seventh base (Supplementary Table 1). We found that only three of the four nucleic acid homopolymers accelerated the rate of MA/CA cleavage, with poly(dA) incapable of enhancing the rate of the reaction by any significant amount under the conditions tested. The three other oligonucleotides yielded similar results in both the magnitude of their effect and their EC50 values (Table 1). Furthermore, the 15-20-fold rate enhancement observed was also consistent with the predicted result based upon the size of the molecules. The observation that poly(dA) was ineffective indicates that while a polyanion is necessary, it is not sufficient for enhancing proteolysis.

Additionally, if the PR-RNA interaction is electrostatic in nature, the pH and ionic strength of the reaction mixture should have considerable influence over the enhancer effect. The intracellular ionic strength of mammalian cells is approximately 0.15 M, which is similar to the conditions of our single-substrate assays. Increasing the ionic strength to 0.2 M by adding NaCl to the reaction buffer reduced the magnitude of the effect to only a 10-fold enhancement. In reactions with an ionic strength of 0.5 M or higher, RNA had no effect on the rate of proteolysis (Supplementary Figure 4A). Though the pH at the site of virus assembly, budding, and maturation has not yet been formally determined, the cytosolic pH of lymphocytes is known to be approximately 7.2 [47]. When we performed assays at pH 7.2, select shorter nucleic acids, including tRNA and G6A6C6, still accelerated MA/CA processing albeit to a very limited degree; the remaining 17-21 single-stranded DNA molecules became ineffective (data not shown). Long heteropolymeric RNA was also still effective, but similarly to raising the ionic strength, the magnitude of the effect decreased to approximately eightfold enhancement (Supplementary Figure 4b).

RNA-dependent enhancement is not the result of a change in HIV-1 PR monomer-dimer equilibrium

We attempted to discern the mechanism by which RNA and other polyanions enhance HIV-1 PR catalytic activity. As the HIV-1 PR is a non-tethered dimer, its monomeric and dimeric forms exist in a state of equilibrium [48]. We hypothesized that RNA may shift the equilibrium by stabilizing or promoting the dimeric form of the PR, effectively increasing the number of active PR molecules in the reaction. Accordingly, tethering the dimer together should abrogate the RNA-enhancement phenotype. We generated an HIV-1 PR dimer where the C terminus of one monomer is tethered to the N terminus of the second monomer by a flexible five amino acid linker. After controlling for the number of active sites present in the proteolysis reactions, we generated a dose-response curve for the tethered dimer with p15 RNA as the enhancer (Figure 8). Compared to the control, no differences were observed between the tethered dimer and wild type PRs. RNA accelerated the rate of both reactions by more than 80-fold, and with similar EC50 values (36 nM for wild type, 35 nM for the tethered dimer). Therefore, RNA-dependent enhancement does not result from promoting dimeric interactions between HIV-1 PR monomers.

Figure 8.

RNA acts on the dimeric form of the HIV-1 PR to accelerate MA/CA processing. Dose response curves were created to compare the ability of RNA to enhance the activity of the monomeric HIV-1 PR (circle) and a tethered dimer of the HIV-1 PR (square). Reactions were performed with the globular MA/CA substrate under standard conditions except that the concentration of the tethered PR dimer was reduced to reflect its pre-existing dimerized state.

The HIV-1 PR-RNA interaction lowers the Km and increases the Vmax of the proteolysis reaction

In order to determine the effect of RNA on the enzymatic parameters of the PR, we used the fluorogenic peptide substrate to generate Michaelis-Menten plots and determined the effect of RNA on Km and Vmax. In the presence of RNA, Km decreased by almost 4-fold, while Vmax increased by 3-fold (Figure 9 and Table 2). The lower Km indicates that RNA increases the affinity of the HIV-1 PR for its substrates, while the higher Vmax demonstrates that RNA also increases the rate of the catalysis step. Using Vmax as a surrogate for kcat we calculated the relative specificity constant (kcat/Km) for the enzyme with and without RNA present finding that RNA increases the relative kcat/Km for the peptide reaction by an order of magnitude (Table 2). Thus the HIV-1 PR is 10-fold more efficient at cleaving the peptide substrate when interacting with RNA.

Figure 9.

Both the affinity of the HIV-1 PR for a peptide substrate and reaction turnover number increase in the presence of RNA. Peptide proteolysis reactions were prepared where the concentration of peptide was varied from 3 to 40 μM. Reaction progress curves were generated for each reaction. The initial velocity of each reaction was determined from the reaction progress curves and plotted as a function of peptide concentration in the absence (square) or presence (circle) of 400 nM long heteropolymeric RNA. At higher peptide concentrations, substrate began outcompeting the HIV-1 PR for binding to the RNA, resulting in reduced initial velocity values. These data points (27 μM and above) were excluded from the plus-RNA curve in the calculation of Km and Vmax. Each point on the curve was calculated twice, with each calculation the result of reactions run in triplicate (i.e. six total reactions per point). Error bars represent the difference in the pair of calculated initial velocity measurements.

Table 2.

Enzymatic parameters of the HIV-1 PR for processing of a peptide substrate.

| Km (μM) | Vmax (RLU/min) | Relative kcat/Km | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without RNA | 13.6 | 282,000 | 1× |

| With RNA | 3.6 | 784,000 | 10.5× |

There were two other notable features of the plots. First, once the peptide substrate concentration reached 25 μM, the initial velocity of the reactions containing RNA began to decline, eventually converging with the minus-RNA curve. The peptide concentration where this reduction began changed depending upon the amount of RNA present in the reaction (data not shown), suggesting that the reduction in effect happened because the substrate was outcompeting the PR for binding to the RNA at these high concentrations. These data points were excluded for the determination of Km and Vmax in the presence of RNA. Second, despite the HIV-1 PR having only a single active site, the Hill coefficient was equal to 1.9 for the minus-RNA plot. The hill coefficient for the plus-RNA curve was calculated to be 1.9 as well; however, because of the low Km, the rapid loss of steady-state conditions at low starting peptide concentrations, and background levels of fluorescence, we did not have enough data points below the Km to show this with confidence. We did attempt to gather more data by lowering the PR concentration, and in those experiments still found a value for the Hill coefficient to be greater than one (data not shown), suggesting the Hill coefficient is greater than one irrespective of whether RNA is present. We cannot explain this result, though sigmoidal Michaelis-Menten curves can be observed in the absence of cooperativity [49].

Discussion

Converting a nascent HIV-1 particle into a mature infectious virion requires the viral PR to cleave the Gag and Gag-Pro-Pol polyproteins in a precise order [22-24]. Given the complexity of this process, numerous regulatory mechanisms exist to direct the PR towards specific processing sites at various phases of maturation. These determinants of cleavage include processing site amino acid sequence [28-30], the local structural context [20, 31-33], and cofactors such as RNA or DNA [31, 34-36]. An effect of RNA or other nucleic acids on processing rate has previously been reported only for cleavage sites nearby NC [31, 34-36], yet we found RNA accelerated the cleavage of substrates completely independent from NC. Moreover, accelerated processing of the MA/CA-AAA and peptide substrates indicated a substrate-RNA interaction was not required. We hypothesized that an enzyme-RNA interaction could enhance PR activity, and found the HIV-1 PR capable of interacting with nucleic acid in a gel-shift assay. The HIV-2 PR lacked this ability, and did not cleave its substrate more efficiently in the presence of RNA, providing corollary evidence. Interactions between the HIV-1 PR and RNA are primarily electrostatic in nature rather than sequence specific, though some additional prerequisites for the polyanion may exist. Mechanistically, RNA both increases the affinity of the HIV-1 PR for its substrates, and accelerates reaction turnover.

Proteolysis reactions that included RNA progressed more rapidly than those without RNA for every substrate tested for cleavage by an HIV-1 PR. This finding is in contrast with the original report, which found the rate of only p15NC processing changed in the presence of RNA [35]. Experimental differences could have contributed to overlooking RNA as a general enhancer. In the previous work, most of the assays were limited to the single substrate p15NC, and RNA needed to be removed from the reactions rather than added as a supplement. This carries the inherent risk that some RNA may have remained in the RNA-free reactions. Very low concentrations of long heteropolymeric RNA were sufficient to achieve enhancement (Figure 6), so RNA removal would have needed to be exhaustive. Our two-substrate procedure improved upon these limitations by ensuring the reaction conditions were exactly the same for both p15NC and MA/CA substrates, and by precisely controlling the amount of RNA added to the reaction. We also suspect differences in substrates may have impacted the previous results. Though our MA/CA contained the whole of CA, an unusual truncation of CA within the N-terminal domain (at amino acid 78) was employed previously. This truncation may have contributed by altering the fold of the MA/CA protein in such a way that it affected its ability to serve as a substrate. Thus, our results are consistent with most of the experiments that identified RNA as an effector of p15NC processing. However, our interpretation of these results is very different in that we find the enhancing effect to require an interaction between RNA and the PR rather than RNA and the substrate.

A more recent publication found the rate of SP1/NC processing increased in the presence of a single-stranded DNA molecule [31]. The authors attributed this result to an increased accessibility of the SP1/NC processing site after NC bound the target nucleic acid molecule. Importantly, enhanced SP1/NC processing occurred in the absence of accelerated MA/CA or CA/SP1 cleavage. Such a result would argue in favor of RNA selectively enhancing cleavage of the sites nearby NC. There are several significant differences between this study and ours. In order to prevent aggregation of their substrate, the reactions were performed under high salt conditions (300 mM NaCl). We (Supplementary Figure 4a) and others [39] have demonstrated that nucleic acid-dependent enhancement of PR activity is tempered by increasing the ionic strength of the reaction. Also, they used a much higher substrate concentration and a different form of substrate, which could also affect cleavage site accessibility. Finally, though we did not directly examine the possibility of site-to-site variability in effect, we note that a modest difference in the magnitude of RNA-dependent enhancement was observed for p15NC and MA/CA in the two-substrate assay. While we have shown a robust effect of RNA on HIV-1 PR activity, it is clear that understanding, and untangling, the effect of RNA on PR and on substrate requires further exploration.

The ability of the HIV-1 PR to bind nucleic acid and have this interaction regulate its catalytic efficiency is not without precedent. Three other viral proteases have been identified that use RNA or DNA as a regulator. The human adenovirus proteinase (AVP) exhibits extremely poor functionality on its own, requiring an 11-amino acid peptide and a non-specific interaction with DNA or other polyanions to achieve its maximal activity [50-52]. Prototype foamy virus (PFV) PR utilizes a specific sequence in the PFV genome to facilitate its dimerization and activation [53]. In addition, the hepatitis C virus nonstructural 3 protein contains a serine protease domain (NS3Pro) that can directly bind nucleic acid [54, 55]. In contrast to the AVP, PFV PR, and HIV-1 PR, this interaction negatively regulates NS3Pro activity [55]. Thus, enzymes from very different virus families have been identified that can use nucleic acid as an interacting partner.

In addition to our own work, an interaction between HIV-1 PR and RNA has been suggested by one other study [39], though this report used extremely low ionic strength and low pH conditions. These conditions may have promoted artificial interactions, since they found both polyanions and polycations to be capable of accelerating HIV-1 PR activity; in contrast, we found polycations to be ineffective (data not shown). One additional difference in our results concerns poly(rA), which was reported to enhance PR activity, but we also found ineffective as poly(dA). A possible explanation could be that poly(dA) [56] and poly(rA) [57, 58] exist in different structural states at acidic versus neutral pH. Regardless, we demonstrate a functional interaction between the HIV-1 PR and heteropolymeric RNA can occur in environments with ionic strength and pH conditions likely to be encountered in vivo.

Whether a productive interaction between the HIV-1 PR and RNA actually occurs in vivo remains unknown, however. While acknowledging that in vitro experiments cannot recreate the complex environment within an actual virus particle, in our assays with p15NC the NC-to-PR dimer ratio was 130:1 and the NC-to-nucleotide ratio was 1:8; the latter ratio is noteworthy because the footprint of NC is one molecule per eight nucleotides [59, 60]. Thus, in the presence of enough NC to entirely coat the available RNA, and in substrate-to-enzyme conditions that exceed the ratio of NC-to-PR dimer in virus particles (between 20:1 and 40:1), RNA-dependent enhancement was observed. These results would support the possibility that the interaction can occur in vivo. On the other hand, the enhancement effect was reduced when the reaction pH was raised from 6.5 to 7.2 (Supplementary Figure 4B), implying the effect might be much more limited than what we observed in our reactions. Despite this potential reduced significance, an important role for the interaction cannot yet be ruled out because the pH at the site of virion biogenesis remains undetermined. Of note, the pH optimum for globular substrates appears to be slightly below neutral [32]. Altogether, the currently available information is insufficient for determining whether the interaction between the HIV-1 PR and RNA has a biological role.

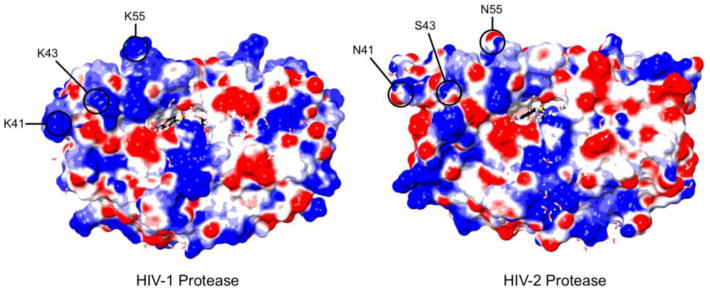

The HIV-2 PR was the sole enzyme examined that failed to process its substrate more efficiently in the presence of RNA, and failed to interact with nucleic acid in the gel-shift assay. The HIV-1 and HIV-2 PRs have very similar structures [61-63], so the lack of interaction is probably not structural. The more likely explanation is that the negative charge of the HIV-2 PR (pI = 5.3) prevents electrostatic interactions with RNA. Visualizing the electrostatic potential of the HIV-1 PR and the HIV-2 PR reveals that the HIV-2 PR has fewer positively charged regions on its surface, especially in the flap regions, which would minimize potential interaction sites for polyanions such as RNA (Figure 10). Though the HIV-2 PR was the exception among the enzymes we examined, it is not the only retroviral PR with a low isoelectric point. Comparing the isoelectric points of 31 primate lentiviruses, a majority of the HIV and SIV strains resembled the HIV-1 Group M PRs, but a sizeable minority had neutral or acidic PRs (Supplementary Table 3). Orthoretrovirus PRs in general also demonstrate variability in charge, though our limited comparison does not rule out the potential for conservation within specific genera (Supplementary Table 4). Regardless, the absence of charge conservation among primate lentiviruses implies a functional interaction in vivo is not required in all settings, and adds further weight to the argument against a biological role for the interaction between the HIV-1 PR and RNA. That the HIV-1 and HIV-2 PRs have similar catalytic properties with peptides in the absence of RNA [64-66] also supports this interpretation. Nonetheless, this information is still insufficient for determining whether an interaction between the HIV-1 PR and RNA actually occurs in vivo, as RNA could regulate Gag processing in different ways for different retroviruses.

Figure 10.

Electrostatic potential of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 PRs. Positively charged regions on the surface of the HIV-1 PR (left, PDB: 1T3R) and HIV-2 PR (right, PDB: 3EBZ) are shown in blue; negatively charged regions are shown in red. Both structures were generated in the presence of darunavir [63, 84]. The flap region of the HIV-1 PR appears to have a basic profile, while the flaps of the HIV-2 PR are of a mixed composition. Highlighted are three amino acid positions (41, 43 [71], and 55 [71, 74]) involved in binding interactions with putative non-active site inhibitors of the HIV-1 PR, which carry a positive charge in the HIV-1 PR but not the HIV-2 PR.

All long, heteropolymeric RNAs were equally effective as enhancers, suggesting all the RNAs contained a critical sequence and/or structure, or that neither were required. Because no small molecule was equally potent to the long RNAs, yet some could still enhance PR activity, a sequence requirement is unlikely. Most of the short DNA molecules that improved PR function were G-rich, suggesting a G-quadruplex structure could have been necessary. However, the successful enhancement of proteolysis by poly(dC), poly(dT), and heparin makes it unlikely a specific structure is required. Poly(dC) and poly(dT) also accelerated processing to an equivalent extent as poly(dG), implying no nucleotide was preferred either. This leaves electrostatic interactions as the primary means of interaction between enzyme and nucleic acid.

Though an electrostatic attraction appears to be the key requirement, additional determinants also exist that modulate the effectiveness of the interaction. Since the magnitude of enhancement plateaued at lower levels despite higher concentrations of smaller polyanions, simply saturating the binding sites on the HIV-1 PR is not sufficient for achieving a maximum magnitude of the effect. Consequently, the size or length of the polyanion must also be important. Poly(dA) and yeast tRNA point to one other additional requirement, as they were exceptions to this conclusion. Both of these nucleic acids are more rigid than other transcripts: tRNA due to base pairing and base modifications [67], and poly(dA) due to strong base-stacking interactions [68, 69]. This suggests that the polyanion must have flexibility to serve as an efficient cofactor, in addition to being of sufficient length.

RNA enhances the catalytic activity of PFV PR by promoting its dimerization [53], so we considered this possibility for the mechanism of HIV-1 PR enhancement. Since, the concentration of HIV-1 PR was 100 nM in our reactions, which is well above the Kd of 6.8 nM determined for similar conditions of pH, ionic strength, and temperature [48], and the estimated half-life of an HIV-1 PR dimer is approximately 30 minutes [48], most of the PR was dimeric throughout the assay regardless of the availability of RNA. Therefore, acceleration by RNA was likely occurring with already intact PR dimers. The tethered dimer, which does not dissociate like the wild-type PR [70], confirms this conclusion because we saw a nearly identical effect of RNA on tethered dimer activity. Additionally, for a particle with a diameter of 120 nm and 120-240 Gag-Pro-Pol molecules, the concentration of the monomeric PR is 220-440 μM, well above the dissociation constant of the PR even while embedded in Gag-Pro-Pol (∼680 nM) [14]. The monomer-dimer equilibrium should therefore heavily favor the dimeric species in virus particles. Although we have not examined an independent effect on dimerization of the PR, the ability of RNA to enhance PR activity appears unlikely to be the related to dimerization.

RNA increased both the affinity of the HIV-1 PR for a peptide substrate (Km) and its molecular activity (kcat), collectively increasing the catalytic efficiency of the HIV-1 PR by an order of magnitude for the peptide reaction. Considering RNA affected peptide proteolysis less than cleavage of the globular MA/CA protein, the change in the specificity constant for reactions with the globular substrates would likely be even more substantial. These data do not, however, illuminate the precise mechanistic explanation for RNA-dependent enhancement. As there is a direct interaction, and it does not interfere with substrate binding, RNA more likely interacts with a secondary binding site(s) on the PR. The consistent inferiority in effectiveness of short nucleic acids compared to long heteropolymeric RNA regardless of concentration additionally implies that the polyanion must affect the PR in some way beyond simply saturating the binding site(s) on the PR. Putative allosteric sites have been identified within the flap/hinge region of the PR by means of small molecules [71-73] and existing PR inhibitors [63, 74]. As the flaps seem to have key roles in both substrate binding and catalysis [75, 76], it is possible to speculate that RNA interacts with the PR flaps to facilitate the many conformational rearrangements this highly dynamic region must undergo [77-80]. Of note, the flap regions of the HIV-1 PR (residues 37-61) contain a trio of basic amino acids (R/K41, K43 [71], and K55 [71, 74]) that are uncharged in the HIV-2 PR (Figure 10), and these same residues were identified as a key part of at least some binding interactions.

In summary, we have found that the HIV-1 PR interacts directly with nucleic acid, and this interaction drives the accelerated rate of processing observed for p15NC and other substrates. No specific RNA sequence or structure is necessary for it to serve as an enhancer, but larger and more flexible polyanions are more effective. Though the exact mechanism by which RNA improves the catalytic efficiency of the HIV-1 PR remains undetermined, the net effect on the enzyme is both an increase in substrate-binding affinity and an increase in turnover rate. These data suggest an allosteric binding site may exist on the HIV-1 PR, and argue in favor of viral genomic RNA being an additional regulator of HIV-1 PR activity during virion maturation.

Materials and Methods

Constructs

The MA/CA and p15NC regions were amplified by PCR from the pBARK plasmid, which contains the entirety of the gag and pro genes from NL4-3. Primers were designed to add a 6×His tag to the N terminus of each protein, a termination codon at the C terminus, and flanking NdeI sites. Following digestion with NdeI, the PCR products were cloned into pET-30b (Novagen) to create pET-p15 and pET-MA/CAxTC. The pET-MA/CAxTC plasmid underwent an additional round of mutagenesis to introduce a tetracysteine motif (CCPGCC) in the Cyclophilin A binding loop (His87-Ala92) of CA and create pET-MA/CA. Two additional plasmids coding for the alternative MA/CA substrates, MA/CA-AAA and HIV-2 MA/CA, are derived from pETMA/CA. For pET-MA/CAaaa, the nucleic acid sequence was altered to change MA amino acids K26KQYK30 to A26AQYA30. In the pET-MA/CA-HIV2 construct, the coding sequence for the cleavage site was altered from SQNY/PIVQ to the canonical HIV-2 MA/CA sequence of GGNY/PVQQ. The pET-GMCΔ construct was created as previously described [32]. The PR region was also amplified out of pBARK and cloned into pET-30b, but without the addition of the 6×-His tag and termination codon, creating pET-PR.

Nucleic Acids

All long heteropolymeric RNAs were generated by in vitro transcription. The pET-MA/CA, pET-p15NC, and pET-PR plasmids were linearized with EcoRV, and purified with the Qiagen PCR purification kit. The MEGAscript T7 high yield transcription kit (Ambion) was utilized to generate RNA from the linearized DNA according to manufacturer's instructions. RNA was purified from the reactions with the Qiagen RNeasy kit and stored short-term in nuclease-free water at -20°C. All short single-stranded DNA molecules were ordered from Sigma-Aldrich, and resuspended in nuclease-free water. Nucleic acid concentrations were determined with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

Expression and Purification of Globular HIV-1 PR Substrates

Escherichia coli BL21 DE3 lysogens (Novagen) were transformed with plasmids coding for the p15NC, MA/CA, MA/CA-AAA, HIV-2 MA/CA, or GMCΔ proteins. Starter cultures were grown overnight in 2×YT media, and then used to inoculate MagicMedia (Invitrogen) for protein production. Expression cultures were grown for 8 hours at 37°C and 225 rpm, before pelleting by centrifugation and freezing overnight at -80°C. Pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (TBS pH 7.5, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and lysed by sonication. Cellular debris was collected by centrifugation, and the resulting supernatant was applied to Ni-NTA Superflow columns (Qiagen) for purification of the His-tagged proteins by affinity chromatography. Purified proteins were concentrated using Vivaspin Concentrators (GE Healthcare), and underwent buffer exchange into storage buffer (20 mM sodium acetate, 140 mM sodium chloride, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, pH 6.5). Sample pH was confirmed using a micro-pH electrode (Thermo Scientific). Purified protein samples were tested for residual nucleic acid with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), and the levels were found to be negligible.

HIV-1 Proteases

Purified HIV-1 proteases were produced as described previously [32, 81]. Oligonucleotides for the heavily mutated variants were designed and purchased. Briefly, HIV-1 protease variants were expressed from a pXC35 Escherichia coli plasmid vector. The cell pellets were lysed and the protease was retrieved from inclusion bodies with 100% glacial acetic acid. The protease was separated from higher molecular weight proteins by size-exclusion chromatography on a Sephadex G-75 column. The purified protein was refolded by rapid dilution into a 10-fold volume of 0.05 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 5.5, containing 10% glycerol, 5% ethylene glycol, and 5 mM dithiothreitol (refolding buffer). The tethered dimer gene construct coded for two copies of the HIV-1 monomer linked by the nucleotide sequence that codes for Gly-Gly-Ser-Ser-Gly with unique nucleotide sequences for each monomer [82, 83]. The HIV-2 PR [64] was a generous gift from Dr. John M. Louis (NIH). The theoretical isoelectric points of the viral proteases were calculated using the online ExPASy pI/MW tool.

Two-substrate Proteolysis Reactions

Two-substrate proteolysis reactions were run in proteolysis buffer (50 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM NaMES, 100 mM Tris, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.5). Reactions were 150 μl in volume and pre-incubated at 30°C for 1 hour before addition of the enzyme. The pre-incubation step was included for consistency, although the its primary role was to allow fluor binding in reactions that included the Lumio Green Reagent (Invitrogen). In the MA/CA and GMCΔ reactions, both substrates began the reaction at concentrations of 2.5 μM. In the MA/CA and p15NC reactions, the initial concentration of MA/CA was 2.5 μM, while the concentration of p15NC was raised to 10 μM due to its poor staining profile in the subsequent analysis. The HIV-1 PR was used at a concentration of 150 nM in the two substrate assays. RNA was also 150 nM when present. Reaction pH was confirmed as 6.5 using a micro-pH electrode (Thermo Scientific) after the final time point had been collected, and was unaffected by the presence of RNA. To collect time points, 12 μl aliquots were removed from the reactions at the indicated times and added directly to SDS to quench the reaction. The zero minute time point was removed immediately prior to the addition of enzyme. Where applicable, RNA was pre-mixed into the reaction 5 minutes prior to the removal of the zero minute time point. The quenched aliquots were loaded directly into a precast 16% Tris-Glycine gel (Invitrogen), and the substrates and products were then separated by SDS-PAGE at 100V for 2.5 hours before staining with SimplyBlue Safestain (Invitrogen). Band intensities were quantified with molecular imaging software (Carestream), and results were reported as the percent substrate remaining.

Single-substrate Proteolysis Reactions

All presented single-substrate proteolysis reactions with globular proteins were run in the proteolysis buffer. For the indicated reactions, the ionic strength was raised to 0.2 M and 0.5 M by the addition of sodium chloride to a final concentration of 50 mM and 350 mM, respectively. Select reactions for data not shown were performed in intracellular buffer (76.6 mM monopotassium phosphate, 60 mM potassium hydroxide, 12 mM sodium bicarbonate, 2.4 mM potassium chloride, 0.8 mM magnesium chloride, pH 7.2). Reaction pH was confirmed after collection of the final time point by a micropH electrode (Thermo Scientific). The final concentrations of MA/CA, MA/CA-AAA, and HIV-2 MA/CA were 2 μM. Reaction mixtures additionally included the Lumio Green Reagent (Invitrogen) to a final concentration of 2.5 μM, and were pre-incubated at 30°C for one hour prior to initiating proteolysis. The concentration of RNA, where not directly stated, was 150 nM. Heparin and spermine were acquired from Sigma. The HIV-1 and HIV-2 PRs were used at a concentration of 100 nM in the single-substrate assays. The tethered dimer of the HIV-1 PR was used at a concentration of 45 nM, an amount with activity equivalent to the monomeric PR in the absence of RNA. The concentrations of the remaining enzymes were adjusted so that approximately 10% of MA/CA was processed in the absence of RNA after ten minutes. Most of the other enzymes were used at concentrations similar to the HIV-1 PR (75-400 nM); VEG23 and VSL23 required concentrations of 2 μM, however. Time points were collected, quenched, and electrophoresed as for the two-substrate assays. The fluorescently labeled proteins were imaged with a Typhoon 9000 (GE Healthcare/Amersham Biosciences), and quantified by ImageQuant TL (GE Healthcare) software. Results were reported as the percent product formed. The initial rate of the reaction was determined using only the data points collected where the reaction was ≤10% complete, or was estimated based on the first non-zero data point collected.

Peptide Proteolysis Reactions

Peptide proteolysis reactions were run in the peptide buffer (100 mM sodium chloride, 30 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.8). The peptide utilized was HIV Protease Substrate 1 (Sigma), a 12-amino acid long peptide containing the canonical HIV-1 MA/CA cleavage site. Substrate master mixes and the PR master mix were aliquoted into separate wells of a 96-well half-area plate (Costar) and pre-incubated in the 30°C reaction chamber for five minutes, during which time the background level of fluorescence was determined. A multi-channel pipet was used to simultaneously mix the HIV-1 PR into the substrate mixtures to a final concentration of 100 nM. Reactions were followed in real-time on an Envision MultiLabel Reader (PerkinElmer) for 10 minutes with time points collected every 20 seconds. When included in the reaction, the concentration of RNA was 400 nM. Reaction rates were calculated using the data points from only the first 10% of cleavage for each substrate concentration. To determine when 10% cleavage had occurred for each reaction, a standard curve was generated from 50 μM reactions that had been run to completion and diluted to various concentrations. The values were linear from background to the upper limit of detection, a range of 0.25 μM to 7 μM. All values necessary to follow the first 10% of each reaction fell within this range (0.3 μM – 4 μM).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays and Native DNA gels

Binding reactions were 10 μl in size and contained 100 ng of ODN17 (final concentration of ∼2 μM). Protein was added to a set of reactions incrementally such that their concentration increased from 0 μM to 12 μM. Where the mixture of nucleic acid and protein was insufficient to reach full volume, storage buffer was used. The pH of the binding reactions was confirmed to be 6.5 by a micropH electrode. After five minutes at room temperature, 1 μl of High-Density TBE Sample Buffer (Novex) was added. Samples were then loaded into a precast 6% DNA retardation gel (Invitrogen), and electrophoresed at 100V for 35 minutes. Gels were stained with SYBR gold (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions, and viewed with molecular imaging software (Carestream). After three five-minute washes with deionized water, the gels were stained for protein with Sypro Ruby (Invitrogen), also according to manufacturer's instructions. Results were reported as percent band intensity.

Native DNA gels were prepared similarly to the gel-shift assays, but nuclease free water was used in place of storage buffer. Additionally, no protein was present in any sample, and gels were only stained with SYBR gold. Where applicable, aliquots of the stock solutions were heated to 90°C for 10 minutes, then cooled rapidly by centrifugation prior to dilution. Diluting the samples before heating results in a lower retention of the higher molecular weight species.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

The mechanisms regulating HIV-1 protease (PR) activity are poorly understood.

RNA accelerates cleavage of multiple substrates, regardless of RNA-binding ability.

The HIV-1 PR can interact with nucleic acid to increase its catalytic efficiency.

The interaction is primarily electrostatic, but size/structural determinants exist.

Interactions between the HIV-1 PR and RNA could affect PR activity in the virion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John M. Louis for providing the HIV-2 Protease, and Dr. Charles Carter for many helpful discussions. We also thank Dr. Nancy Cheng for assistance with the protease substrate assay. M.P. is supported, in part, by NIH Training Grant T32 AI07001. This work was supported by the NIH grant P01 GM109767. In addition, CAS, EAN and DAR were supported by NIH grant R01 GM65347, and DAR was also supported by R01 GM065347-12S1 and F31 GM111101.

Abbreviations

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- PR

protease

- AVP

adenovirus proteinase

- PFV

prototype foamy virus

- NS3pro

non-structural protein 3 serine protease

- MA

matrix

- CA

capsid

- NC

nucleocapsid

- SP1/2

spacer peptide 1/2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kol N, Shi Y, Tsvitov M, Barlam D, Shneck RZ, Kay MS, et al. A stiffness switch in human immunodeficiency virus. Biophys J. 2007;92:1777–83. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohl NE, Emini EA, Schleif WA, Davis LJ, Heimbach JC, Dixon RA, et al. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4686–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaplan AH, Manchester M, Swanstrom R. The activity of the protease of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is initiated at the membrane of infected cells before the release of viral proteins and is required for release to occur with maximum efficiency. J Virol. 1994;68:6782–6786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6782-6786.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krausslich HG. Human immunodeficiency virus proteinase dimer as component of the viral polyprotein prevents particle assembly and viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3213–3217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J, Morrow CD. Overexpression of the gag-pol precursor from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral genomes results in efficient proteolytic processing in the absence of virion production. J Virol. 1991;65:5111–5117. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.5111-5117.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaplan AH, Zack JA, Knigge M, Paul DA, Kempf DJ, Norbeck DW, et al. Partial inhibition of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease results in aberrant virus assembly and the formation of noninfectious particles. J Virol. 1993;67:4050–4055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4050-4055.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore MD, Fu W, Soheilian F, Nagashima K, Ptak RG, Pathak VK, et al. Suboptimal inhibition of protease activity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effects on virion morphogenesis and RNA maturation. Virology. 2008;379:152–60. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller B, Anders M, Akiyama H, Welsch S, Glass B, Nikovics K, et al. HIV-1 Gag processing intermediates trans-dominantly interfere with HIV-1 infectivity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29692–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.027144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bieniasz PD. The cell biology of HIV-1 virion genesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:550–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller M, Schneider J, Sathyanarayana BK, Toth MV, Marshall GR, Clawson L, et al. Structure of complex of synthetic HIV-1 protease with a substrate-based inhibitor at 2.3 Å resolution. Science. 1989;246:1149–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.2686029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Navia MA, Fitzgerald PMD, McKeever BM, Leu C, Heimbach JC, Herber WK, et al. Three-dimensional structure of aspartyl protease from human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1. Nature. 1989;337:615–620. doi: 10.1038/337615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearl LH, Taylor WR. A structural model for retroviral proteases. Nature. 1987;329:351–354. doi: 10.1038/329351a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agniswamy J, Sayer JM, Weber IT, Louis JM. Terminal interface conformations modulate dimer stability prior to amino terminal autoprocessing of HIV-1 protease. Biochemistry. 2012;51:1041–50. doi: 10.1021/bi201809s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louis JM, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Autoprocessing of HIV-1 protease is tightly coupled to protein folding. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:868–875. doi: 10.1038/12327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang C, Louis JM, Aniana A, Suh JY, Clore GM. Visualizing transient events in amino-terminal autoprocessing of HIV-1 protease. Nature. 2008;455:693–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindhofer H, von der Helm K, Nitschko H. In vivo processing of Pr160gag-pol from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) in acutely infected, cultured human T-lymphocytes. Virology. 1995;214:624–627. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louis JM, Wondrak EM, Kimmel AR, Wingfield PT, Nashed NT. Proteolytic processing of HIV-1 protease precursor, kinetics and mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23437–23442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettit SC, Everitt LE, Choudhury S, Dunn BM, Kaplan AH. Initial cleavage of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 GagPol precursor by its activated protease occurs by an intramolecular mechanism. J Virol. 2004;78:8477–85. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8477-8485.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sluis-Cremer N, Arion D, Abram ME, Parniak MA. Proteolytic processing of an HIV-1 pol polyprotein precursor: insights into the mechanism of reverse transcriptase p66/p51 heterodimer formation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1836–47. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettit SC, Clemente JC, Jeung JA, Dunn BM, Kaplan AH. Ordered processing of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 GagPol precursor is influenced by the context of the embedded viral protease. J Virol. 2005;79:10601–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10601-10607.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wondrak EM, Louis JM. Influence of flanking sequences on the dimer stability of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12957–12962. doi: 10.1021/bi960984y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erickson-Viitanen S, Manfredi J, Viitanen P, Tribe DE, Tritch R, Hutchison CA, III, et al. Cleavage of HIV-1 gag polyprotein synthesized in vitro: sequential cleavage by the viral protease. AIDS Res Hum Retrov. 1989;5:577–591. doi: 10.1089/aid.1989.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettit SC, Moody MD, Wehbie RS, Kaplan AH, Nantermet PV, Klein CA, et al. The p2 domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag regulates sequential proteolytic processing and is required to produce fully infectious virions. J Virol. 1994;68:8017–8027. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8017-8027.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiegers K, Rutter G, Kottler H, Tessmer U, Hohenberg H, Krausslich HG. Sequential steps in human immunodeficiency virus particle maturation revealed by alterations of individual gag polyprotein cleavage sites. J Virol. 1998;72:2846–2854. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2846-2854.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Checkley MA, Luttge BG, Soheilian F, Nagashima K, Freed EO. The capsid-spacer peptide 1 Gag processing intermediate is a dominant-negative inhibitor of HIV-1 maturation. Virology. 2010;400:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SK, Harris J, Swanstrom R. A strongly transdominant mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene defines an Achilles heel in the virus life cycle. J Virol. 2009;83:8536–43. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00317-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rulli SJ, Jr, Muriaux D, Nagashima K, Mirro J, Oshima M, Baumann JG, et al. Mutant murine leukemia virus Gag proteins lacking proline at the N-terminus of the capsid domain block infectivity in virions containing wild-type Gag. Virology. 2006;347:364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pettit SC, Simsic J, Loeb DD, Everitt LE, Hutchison CA, III, Swanstrom R. Analysis of retroviral protease cleavage sites reveals two types of cleavage sites and the structural requirements of the P1 amino acid. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14539–14547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozen A, Haliloglu T, Schiffer CA. Dynamics of preferential substrate recognition in HIV-1 protease: redefining the substrate envelope. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:726–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer CA. Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes. Structure. 2002;10:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deshmukh L, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. Conformation and dynamics of the Gag polyprotein of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 studied by NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501985112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]