Abstract

Objective

General practitioners can record patients’ presenting symptoms by using a code or free text. We compared breathlessness and wheeze symptom codes and free text recorded prior to diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease (IHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma.

Design

A case–control study.

Setting

11 general practices in North Staffordshire, UK, contributing to the Consultations in Primary Care Archive consultation database.

Participants

Cases with an incident diagnosis of IHD, COPD or asthma in 2010 were matched to controls (four per case) with no such diagnosis. All prior consultations with codes for breathlessness or wheeze symptoms between 2004 and 2010 were identified. Free text of cases and controls were also searched for mention of these symptoms.

Results

592 cases were identified, 194 (33%) with IHD, 182 (31%) with COPD and 216 (37%) with asthma. 148 (25%) cases and 125 (5%) controls had a prior coded consultation for breathlessness. Prevalence of a prior coded symptom of breathlessness or wheeze was 30% in cases, 6% in controls. Median time from first coded symptom to diagnosis among cases was 57 weeks. After adding symptoms recorded in text, prevalence rose to 62% in cases and 25% in controls. Median time from first recorded symptom increased to 144 weeks. The associations between diagnosis of cases and prior symptom codes was strong IHD relative risk ratio (RRR) 3.21 (2.15 to 4.79); COPD RRR 9.56 (6.74 to 13.60); asthma RRR 10.30 (7.17 to 14.90).

Conclusions

There is an association between IHD, COPD and asthma diagnosis and earlier consultation for respiratory symptoms. Symptoms are often noted in free text by GPs long before they are coded. Free text searching may aid investigation of early presentation of long-term conditions using GP databases, and may be an important direction for future research.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Previous studies have mainly focussed on the time taken between first recording of symptoms and diagnosis of several cancers. This novel study investigates the time taken from the recording of respiratory symptoms as code or as free text to diagnosis.

General practitioner (GP) database research typically focuses on coded information rather than consultation text. However, searching for symptom codes only identified less than half of those with a GP record of prior respiratory symptoms in patients newly diagnosed with ischaemic heart disease (IHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma.

Time from first recorded symptom to date of diagnosis may be substantially shorter when the search of databases is restricted to symptom codes than when expanded to include text entries as well.

However, associations between previous respiratory symptoms and diagnosis were weaker when the analysis included text search as well as symptom codes.

Introduction

Research into potential benefits and costs of early intervention in people with long-term conditions will be helped by identifying such patients as early as possible in the course of their condition. General practice typically provides the first point of access to non-emergency UK care; more than 95% of the population is registered with a general practitioner (GP) to provide such care, and this setting, therefore, provides an important arena for investigating prognosis and healthcare among patients who first consult in the early stages of long-term conditions. Recent examples of such studies have been provided by research into the early presenting symptoms of cancer.1 2

GPs, however, may not necessarily diagnose or label people with a long-term condition at these first consultations. First, because it may not be obvious that the illness represents the presenting symptom of a long-term condition rather than a short-term or self-limiting problem; second, because the presenting symptoms may represent a range of future possible long-term conditions; and third, because there may be no obvious advantage to diagnosis at this early stage and so the GP may prefer to label or record the problem initially as a symptom.

This range of options is reflected in the fact that GPs in the UK can record symptoms or diagnoses or both in the medical records, and can do so by using free text entries or by allocating codes or by doing both. There is evidence that GPs may choose to code symptoms, rather than to simply note them in the text, if there is only one presenting problem to record, or if the symptom is regarded as more serious or a higher priority than other presenting problems.1 2 For researchers using computerised general practice databases, coded symptoms and diagnoses are generally straightforward to identify, once the relevant codes have been determined. Information in the consultation free text is harder to extract, electronically or manually, but may represent the first recorded manifestation of a disease.

In this paper, we use the example of symptoms of breathlessness and wheeze recorded in primary care consultations to compare free text entries with coded symptom information as potential measures of early presentation of future long-term conditions, namely ischaemic heart disease (IHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma.

Breathlessness and wheeze are common presentations in primary care. The symptoms are frequent early manifestations of COPD and asthma.3–10 However, these respiratory diseases may not be recognised or labelled as such.9–12 Breathlessness and wheeze are also presenting symptoms of heart failure.13 14 Men with breathlessness, for example, are at twofold higher risk of future major IHD events than men without breathlessness.15 16 Persons with both IHD and COPD have more breathlessness, sputum, wheeze and cough than those with COPD alone.16 Such symptoms may, however, also be manifestations of short-term or self-limiting illness such as upper respiratory tract infection. Hence, we have also investigated prior breathlessness and wheeze in matched controls who do not have IHD, COPD or asthma.

Methods and analysis

We performed a case–control study using the Consultations in Primary Care Archive (CiPCA), a database which contains all recorded consultation data from a subset of general practices in North Staffordshire, UK. We have previously published evidence of completeness of this information.17 CiPCA practices code morbidity using a standard dictionary of codes (Read codes). The Read code system is structured into symptom, diagnostic and process of care chapters. For example, diagnostic codes may be found in Chapter H representing ‘Respiratory System Diseases’. Symptoms when coded may be recorded under Chapter 1, ‘History/Symptoms’ or Chapter R, ‘Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions’. The code lists used for this study are available from (http://www.keele.ac.uk/mrr).

Quality of morbidity coding by CiPCA practices is assessed annually within a feedback and training programme.17 Doctors and nurses are required to enter at least one code per consultation. CiPCA contains the first 220 characters of free text entered at the consultation; there are no standard requirements for free text use in CiPCA practices. Eleven practices continuously contributed to CiPCA from 2004 to 2010. The total registered practice populations in these practices was 94 565 in 2010.

Cases were defined as all patients aged 18 years and over who, in 2010, received a coded consultation for IHD, COPD or asthma, and had no prior consultation coded as such during 2004–2009, and who had been registered with their practice from at least 2004. Controls were selected from patients who had at least one consultation in 2010, but no coded consultations for IHD, COPD or asthma either in 2010 or from 2004 to 2009 inclusive, and who were registered with their practice throughout the period. For each case, potential controls were frequency matched by age, gender and practice, and a sample of four controls per case then randomly selected.

Exposure was defined as prior symptoms of breathlessness and/or wheeze recorded in free text and/or coded as symptoms in the consultation database. Regardless of the free text entry of the consultation, the GP can input a Read code for either a symptom or diagnosis. At least one code (symptom or diagnostic) is required to be recorded by the CiPCA doctors at each consultation. Multiple symptoms can be entered in the text with no corresponding code (symptom or diagnosis) necessarily relating to those text-noted symptoms.

To establish exposure status, the search for prior consultations relating to breathlessness and wheeze was conducted for both cases and controls in two phases:

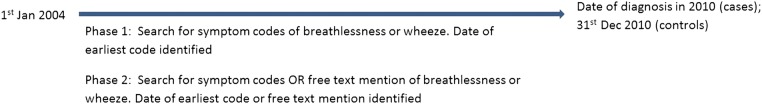

Phase 1: identification of primary care consultations coded with the symptoms ‘breathlessness’ or ‘wheeze’ between 1 January 2004 and the date of diagnosis in 2010 (cases), or 31 December 2010 (controls) as shown in figure 1.

Phase 2: for the same time period, electronic searches of the free text of consultations to identify those entries which included words starting with ‘breathless*’, ‘wheez*’, ‘sob*’ (short of breath), ‘dyspn*’ (dyspnoea). Texts were excluded where these words were preceded by ‘no’ or ‘not’. A GP researcher (RAH) manually searched all identified texts plus additional texts which included words starting with ‘breath*’ to ensure they indicated breathlessness or wheeze symptoms. Another researcher (KPJ) double-checked all identified texts.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Analysis

The main case–control analyses focused on associations between diagnosis and prior symptoms. Association between a prior coded symptom of breathlessness or wheeze (exposure status, from phase 1 and the outcome of later diagnosis (IHD, COPD or asthma) was assessed using multinomial multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age and gender, and reported as relative risk ratios (RRR) with 95% CIs with the controls as the reference group. Symptoms identified through searching of text were then added (phase 2), and the analysis repeated to assess the association between at least one prior recorded symptom (coded or in text) and later diagnosis.

Restricting analysis to cases only, median times between first coded symptom and diagnosis, and between first recorded symptom (text or code, whichever came first) and diagnosis, were determined for each of the three diagnostic groups (IHD, COPD, asthma). Analysis used STATA V.12.

Results

A total of 592 cases (194 with IHD, 182 COPD, 216 asthma) were identified and 2368 matched controls selected. Patients with asthma were younger than other cases (mean age 46.2, SD 17.20); IHD cases were the oldest (mean age 68.5, SD 12.95, table 1). Fewer women than men had IHD (41%), but more women had COPD and asthma (58% and 63%, respectively, table 1). The corresponding controls had similar characteristics reflecting the matched design. There were 224 cases (38%) and 1776 controls (75%) with no prior history of consultations about breathlessness or wheeze recorded as either symptom codes or text (table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (age and gender) of participants

| Case groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | All cases | IHD | COPD | Asthma | |

| N | 2368 | 592 | 194 | 182 | 216 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.7 (18.03) | 58.8 (18.13) | 68.5 (12.95) | 63.3 (15.30) | 46.2 (17.20) |

| Female, n (%) | 1284 (54) | 321 (54) | 79 (41) | 106 (58) | 136 (63) |

Three patients were in multiple case groups. These were put in most ‘severe’ category (in order IHD, COPD, asthma).

COPD, chronic obstructive airways disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease.

Table 2.

Identification of prior breathlessness and wheeze symptoms by (1) code alone or (2) by code or textual information

| Case groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | All cases | IHD | COPD | Asthma | |

| N | 2368 | 592 | 194 | 182 | 216 |

| Prior breathlessness, code, n (%) | 125 (5) | 148 (25) | 38 (20) | 62 (34) | 48 (22) |

| Prior breathlessness, code or text, n (%) | 473 (20) | 311 (53) | 94 (48) | 111 (61) | 106 (49) |

| Prior wheeze, code, n (%) | 17 (<1) | 39 (7) | 2 (1) | 10 (5) | 27 (13) |

| Prior wheeze, code or text, n (%) | 238 (10) | 202 (34) | 31 (16) | 68 (37) | 103 (48) |

| Prior breathlessness or wheeze code, n (%) | 141 (6) | 178 (30) | 39 (20) | 71 (39) | 68 (31) |

| Prior breathlessness or wheeze code or text, n (%) | 592 (25) | 368 (62) | 99 (51) | 125 (69) | 144 (67) |

COPD, chronic obstructive airways disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease.

Using symptom codes alone, 178 cases (30%) had a previous record of breathlessness or wheeze (table 2) compared with 6% of controls. Adding text search to this symptom code extraction, there were 368 cases in total with a prior recorded breathlessness or wheeze symptom (62%) compared with 25% of controls.

In the multivariable analysis, a prior coded symptom of breathlessness or wheeze was associated with each of the three case groups when compared with controls, stronger for COPD and asthma (COPD RRR 9.56, 95% CI 6.74 to 13.60; asthma RRR 10.30, 95% CI 7.17 to 14.90) than for IHD (RRR 3.21, 95% CI 2.15 to 4.79) (table 3). The associations between prior symptoms and future diagnosis were weaker when symptoms recorded in the text were included (COPD RRR 6.32, 95% CI 4.54 to 8.80; asthma RRR 7.86, 95% CI 5.73 to 10.80; IHD RRR 2.78, 95% CI 2.05 to 3.78).

Table 3.

Association of prior breathlessness or wheeze symptom with diagnosis of IHD, COPD and asthma

| Case groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (n=2368) | All cases (n=592) | IHD (n=194) | COPD (n=182) | Asthma (n=216) | |

| Phase 1 (code alone) | |||||

| n (%) | |||||

| Without breathlessness or wheeze code | 2227 (94) | 414 (70) | 155 (80) | 111 (61) | 148 (69) |

| With breathlessness or wheeze code | 141 (6) | 178 (30) | 39 (20) | 71 (39) | 68 (31) |

| RRR (95% CI), age and gender adjusted | |||||

| With vs without breathlessness or wheeze code | 1.00 | 7.02 (5.48 to 9.00) | 3.21 (2.15 to 4.79) | 9.56 (6.74 to 13.60) | 10.30 (7.17 to 14.90) |

| Phase 2 (code or textual information) | |||||

| n (%) | |||||

| Without breathlessness/wheeze code or text | 1776 (75) | 224 (38) | 95 (49) | 57 (31) | 72 (33) |

| With breathlessness/wheeze code or text | 592 (25) | 368 (62) | 99 (51) | 125 (69) | 144 (67) |

| RRR (95% CI), age and gender adjusted | |||||

| With vs without breathlessness/wheeze code or text | 1.00 | 5.14 (4.24 to 6.25) | 2.78 (2.05 to 3.78) | 6.32 (4.54 to 8.80) | 7.86 (5.73 to 10.80) |

COPD, chronic obstructive airways disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; RRR, relative risk ratios.

Among the 178 cases with prior symptom codes, the median times from first coded symptom to diagnosis were 44 weeks (COPD), 92 weeks (asthma) and 47 weeks (IHD) (table 4). When this group was expanded to include those with text symptoms (n=368), median time between first recorded breathlessness or wheeze symptom (text or code, whichever came first) and subsequent diagnosis, was 141–149 weeks.

Table 4.

Time in weeks before diagnosis of first recorded breathless or wheeze symptom according to different searching scenarios (code alone vs code or text)

| Median (IQR) time from 1st breathless/wheeze code to diagnosis In weeks (phase 1) |

Median (IQR) time from earliest of 1st breathless/wheeze code or mention in text to diagnosis In weeks (phase 2) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Among (A) cases with code and (B) cases with code or mention in text | |||

| All with code | All with code or mention in text | ||

| IHD (n=39) | 47 (8, 188) | IHD (n=99) | 141 (42, 249) |

| COPD (n=71) | 44 (9, 139) | COPD (n=125) | 149 (44, 275) |

| Asthma (n=68) | 92 (19, 204) | Asthma (n=144) | 142 (32, 252) |

| All cases (n=178) | 57 (11, 169) | All cases (n=368) | 144 (38, 260) |

| Among cases with both code and text mention of symptoms | |||

| All with code AND mention in text | All with code AND mention in text | ||

| IHD (n=31) | 62 (14, 189) | IHD (n=31) | 208 (86, 274) |

| COPD (n=48) | 61 (12, 151) | COPD (n=48) | 185 (95, 276) |

| Asthma (n=50) | 164 (70, 234) | Asthma (n=50) | 240 (168, 312) |

| All cases (n=129) | 91 (21, 216) | All cases (n=129) | 213 (110, 284) |

COPD, chronic obstructive airways disease; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; RRR, relative risk ratios.

In order to investigate whether GPs select different types of patients for recording symptoms in text or by code, we analysed the subgroup of all cases with a record of prior symptoms of breathlessness or wheeze, both coded and recorded in text. Among COPD cases in this subgroup, median time to date of diagnosis from earliest mention of symptoms in either code or text was 185 weeks (table 4), and from first coded symptom only it was 61 weeks; corresponding median times for IHD were 208 and 62 weeks; and for asthma 240 and 164 weeks.

Discussion

This case–control study of patients with IHD, COPD and asthma highlights the frequency of breathlessness or wheeze symptoms presented to primary care prior to diagnosis of a long-term condition and recorded as either Read codes or free text. GP database research typically focuses on coded information rather than the consultation text. In our study, searching for symptom codes identified less than half of those with a GP record of prior symptoms in a group of patients newly diagnosed with IHD, COPD or asthma. Median time from first recorded symptom to date of first diagnosis among cases was substantially shorter when the search was restricted to symptom codes than when expanded to include text entries as well. The differences were just as pronounced in the subgroup of patients who had both text entries and codes for symptoms recorded in their medical notes.

However, the associations between previous symptoms and diagnosis were weaker when the analysis included text search as well as symptom codes, indicating that proportionately fewer persons with initial symptoms recorded in the text went on to develop IHD, COPD or asthma compared with persons whose first symptom presentation was coded.

Comparison with existing literature

Our overall finding that symptom codes can predate diagnosis in IHD, COPD and asthma has also been found in studies of cancer.2 18 19 Neal found the time from symptom code to diagnosis varied widely between different cancers, from 26 weeks for breast cancer to 156 weeks for myeloma, while in ovarian cancer, Tate found that symptom codes were first recorded a median of 19 weeks prior to the first use of a diagnostic code.1 2

The finding that the prevalence of previous symptoms increases when text entries are included as well as symptom codes also reflects work in cancer. Koeling, analysing the same consultations for ovarian cancer in the General Practice Research Database as Tate, found that symptom codes alone identified 35–70% of symptoms in the 12 months preceding diagnosis, but this figure was 77–98% when the symptom code search was combined with a text search using an algorithm to extract strings of words or word fragments based on the words used in the symptom code.19 This compares with the increase from 30% to 62% in identification of cases when text searching for breathlessness or wheeze was added to symptom codes in the current study of respiratory and cardiac diseases reported here.

Computerised data extraction of information from free text has been used previously. These techniques include searching for keywords and for word fragments (such as ‘ovar’ or ‘ov’ for ovarian cancer), similar to the technique used in our study.18 20 Positive and negative symptoms are not differentiated by this type of computer search, for example, between ‘has’ or ‘has no’ breathlessness. Natural Language Processing (NLP) has been used to develop algorithms to deal with grammatical problems.19 21 Computerised extraction of data from free text is limited by the cost of obtaining anonymised data as well as dealing with negation around keywords, abbreviations, misspellings and acronyms.19 20 22 NLP has been developing for over 30 years, but the difficulties in developing a system that can recognise syntax, semantics and domain knowledge in free text are many and complex.23 Voorham extracted numeric clinical data concerning diabetes care embedded in general practice electronic health records as free text, and developed a computerised extraction system triggered by numerical values and incorporating nearby names and units which label the measurement.24

The example chosen for our study drew on the recognition that breathlessness and wheeze are common symptoms of COPD and asthma. Freeman in studying past and present smokers in UK primary care found that the best questions to differentiate persons with and without COPD were breathlessness on exertion and wheeze.25 Ohar, using self-report symptoms at a workplace-based assessment in the USA, found that 75% of those with a diagnosis of airways obstruction had prior breathlessness.26 This compares with the figures in our study, where breathlessness and wheeze were recorded (code or text) prior to diagnosis in 62% of patients with a future diagnosis of IHD, COPD or asthma.

Limitations of the study

This study was not designed to address the question of the best way to identify all earliest symptom consultations among patients who are subsequently diagnosed with IHD, COPD or asthma. There may be other early symptoms and presentations of these conditions, such as chest pain or cough. Our case–control design could not estimate the predictive value of symptoms of breathlessness for future diagnosis. Although controls had a much lower prevalence of prior symptoms than cases, people without IHD, COPD and asthma are more numerous in the general population than people with these diagnoses. A prevalence of 25% of controls who had symptoms when text and codes are both included indicates that the discrimination of who does and does not go on to a diagnosis based on symptoms alone is likely to be limited. Despite this, symptoms were associated with future diagnosis, often a long time later, and so there is potential for future prospective research to establish the prognostic usefulness of the initial presentation of these symptoms.

It is possible that the GP diagnosed the condition prior to the first coded mention in the records, and that interrogation of free text may indicate an earlier date of diagnosis.18 19 Nevertheless, this does further emphasise the importance of considering the use of free text in investigation of early presentation of long-term conditions using GP databases. Alternative definitions of morbidity than recorded diagnosis codes using relevant prescriptions and managements are possible, and further research could explore whether GPs were managing patients optimally despite a lack of formal recorded diagnosis.

All practices providing data to the CiPCA database use the Read code system, a widely used system by GPs in the UK. There may be variation in extent of symptom coding between practices and also between databases of healthcare information depending on coding system used (eg, Read codes or International Classification of Diseases codes) and guidance given on recording.27

One possible limitation was the localised nature of the CiPCA database. It has been used, for example, in studies of gout, dementia and frequent consulters, and provided comparable musculoskeletal prevalence figures to national UK and international databases.28–31 North Staffordshire is a deprived area, but the participating practices were socially and economically diverse. GPs in the practices undergo some training in morbidity recording, but while encouraged to use diagnostic codes, symptom codes may also be used.

Our study spanned 7 years, and patients may have had symptom or diagnostic codes before this. CiPCA allows only examination of the first 220 characters of the consultation text; however, mention of breathlessness or wheeze later in the consultation text would only increase the disparity between coded symptoms alone and consultations using coded or text-recorded symptoms.

Implications for practice and research

Our investigation has not addressed the question of whether it would be clinically useful to identify those who are going on to develop chronic lung or heart disease at the point when they first present with symptoms. The GP is likely to be working with a range of possible future trajectories when using symptoms and symptom codes because, as illustrated by the proportion of controls who have a history of breathlessness and wheeze, these symptoms do not necessarily presage future chronic lung or heart disease. Furthermore, the GPs may well be providing optimal care of patients with these symptoms in relation to the likelihood of different future outcomes. However, our study does highlight the opportunity provided by general practice and general practice databases for prognostic and intervention research into the effectiveness and usefulness of early intervention, given the strong associations we have observed between first symptoms and later diagnoses and the long-time intervals between them. Our study suggests that a combination of symptom codes and text records would provide the optimal sample for such studies by ensuring that the highest proportion possible of all those who present with such symptoms will be included. However, the weaker association of symptoms with a future diagnosis when including text-recorded symptoms suggests, it is possible that those with purely textual information have less serious symptoms.32 Other information from prospective studies will be needed to discriminate between those who will and will not develop long-term conditions.

Diagnostic and symptom codes in GP electronic health records form a ready source of data for research, but much useful information exists in the free text which is harder to extract. Studies of earliest presenting symptoms in national databases are challenging because manual free text searching on a large scale is difficult. However, this would improve if GPs were to code symptoms more readily when unable or not wishing to make a diagnosis. With expanding investment in research resources, technological barriers to textual analyses are likely to be solved.

Conclusion

This study shows that symptoms of breathlessness and wheeze in general practice patients were often recorded as free text or symptom codes by the GP 3 years before diagnosis of IHD, COPD or asthma was coded and recorded. Using only symptom codes as the source of this information identified fewer patients with symptoms, but who were closer in time to getting a chronic disease diagnosis, than was achieved by a search that included both text and codes. Primary care can provide an arena for research into the usefulness of early identification of long-term conditions such as COPD, including investigation of whether it can guide more effective healthcare, and improve long-term outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The Keele GP Research Partnership and the Informatics team at the Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre. The work in this paper was informed and supported by KJ's and PC's membership of the UK Medical Research Council's Prognosis Research (PROGRESS) partnership.

Footnotes

Contributors: RAH, KPJ and PC were involved in the initial conception of the research question and wrote the paper. RAH was involved extensively with all the background research. YC extracted the data from the database and performed the statistical analysis.

Funding: CiPCA was funded by the North Staffordshire Primary Care Research. Consortium and Keele University's Research Institute for Primary Care and Health Sciences.

Disclaimer: RH is a NIHR Academic Clinical Lecturer in General Practice. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the North Staffordshire Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Tate AR, Martin AGR, Murray-Thomas T et al. Determining the date of diagnosis—is it a simple matter? The impact of different approaches to dating diagnosis on estimates of delayed care for ovarian cancer in UK primary care. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2288-9-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neal RD, Din NU, Hamilton W et al. Comparison of cancer diagnostic intervals before and after implementation of NICE guidelines: analysis of data from the UK General Practice Research Database. Br J Cancer 2014;110:584–92. 10.1038/bjc.2013.791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broekhuizen BDL, Sachs A, Janssen K et al. Does a decision aid help physicians to detect chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e674–9. 10.3399/bjgp11X601398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albers M, Schermer T, Heijdra Y et al. Predictive value of lung function below the normal range and respiratory symptoms for progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2008;63:201–7. 10.1136/thx.2006.068007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medbo A, Melbe H. What role may symptoms play in the diagnosis of airflow limitation? Scand J Prim Health Care 2008;26:92–8. 10.1080/02813430802028938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL et al. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States. Arch Int Med 2000;160:1683–9. 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherman CB, Xu X, Speizer FE et al. Longitudinal lung function decline in subjects with respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:855–9. 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krzyzanowski M, Camilli AF, Lebowitz MD et al. Relationship between pulmonary function and changes in chronic respiratory symptoms. Chest 1990;98:62–70. 10.1378/chest.98.1.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kable S, Henry R, Sanson-Fisher R et al. Childhood asthma: can computers aid detection in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51:112–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prins VW, van den Nieuwenhof L, van den Hoogen H et al. The natural history of asthma in a primary care cohort. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:110–15. 10.1370/afm.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soriano JB, Maier WC, Egger P et al. Recent trends in physician diagnosed COPD in women and men in the UK. Thorax 2000;55:789–94. 10.1136/thorax.55.9.789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Casaburi R et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation executive summary. Chest 2007;131:1S–3S. 10.1378/chest.07-0892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raphael C, Briscoe C, Davies J et al. Limitations of the New York Heart Association functional classification system and self-reported walking distances in chronic heart failure. Heart 2007;93:476–82. 10.1136/hrt.2006.089656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson RDS, Gibbs CR, Lip GYH. ABC of Heart failure: clinical features and complications. BMJ 2000;320:236–9. 10.1136/bmj.320.7229.236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feary JR, Rodrgues LC, Smith CJ et al. Prevalence of major comorbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke a comprehensive analysis using data from primary care. Thorax 2010;65:956–62. 10.1136/thx.2009.128082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook DG, Shaper AG. Breathlessness, lung function and the risk of heart attack. Eur Heart J 1988;9:1215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porcheret M, Hughes R, Evans D et al. Data quality of general practice electronic health records: the impact of a program of assessments, feedback, and training. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:78–86. 10.1197/jamia.M1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tate AR, Martin AGR, Ali A et al. Using free text information to explore how and when GPs code a diagnosis of ovarian cancer: an observational study using primary care records of patients with ovarian cancer. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koeling R, Tate AR, Caroll JA. Automatically estimating the incidence of symptoms recorded in GP free text notes. Glasgow, UK: MIXHS'11, 2011:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford E, Nicholson A, Koeling R et al. Optimising the use of electronic health records to estimate the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in primary care: what information is hidden in free text? BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:105 10.1186/1471-2288-13-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah AD, Martinez C, Hemingway H. The freetext matching algorithm: a computer program to extract diagnoses and causes of death from unstructured text in electronic health records. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:88, 1–13 10.1186/1472-6947-12-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Shah AD, Tate AR et al. Extracting diagnoses, and investigation results from unstructured text in electronic health records by semi-supervised machine learning. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e30412 10.1371/journal.pone.0030412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman C, Hripcsack G. Natural language processing and its future in medicine. Acad Med 1999;8:890–5. 10.1097/00001888-199908000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voorham J, Denig P. Computerized extraction of information on the quality of diabetes care from free text in electronic patient records of general practitioners. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:349–54. 10.1197/jamia.M2128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman D, Nordyke RJ, Isonaka S. Questions for COPD diagnostic screening in a primary care setting. Respir Med 2005;99:1311–18. 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohar J, Sadeghnejad A, Meyers D et al. Do symptoms predict COPD in smokers? Chest 2010;6:1345–53. 10.1378/chest.09-2681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan K, Clarke AM, Symmons DPM et al. Measuring disease prevalence: a comparison of musculoskeletal disease using four general practice consultation databases. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:7–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roddy E, Mallen CD, Hider SL et al. Prescription and comorbidity screening following consultation for acute gout in primary care. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;1:105–11. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burton C, Campbell P, Jordan K et al. The association of anxiety and depression with future dementia diagnosis: a case-control study in primary care. Fam Pract 2013;1:25–30. 10.1093/fampra/cms044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster A, Jordan K, Croft P. Is frequent attendance in primary care disease-specific? Fam Pract 2006;4:444–52. 10.1093/fampra/cml019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan KP, Jöud A, Bergknut C et al., International comparisons of the consultation prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions using population-based healthcare data from England and Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;1:212–18. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price S, Shephard E, Stapley S et al. Non-visible vs visible haematuria and bladder cancer risk: a primary care electronic record study. BJGP 2014;64:e584–9. 10.3399/bjgp14X681409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]