Abstract

Traditional therapies for type 1 diabetes (T1D) involve insulin replacement or islet/pancreas transplantation and have numerous limitations. Our previous work demonstrated the ability of embryonic brown adipose tissue (BAT) transplants to establish normoglycemia without insulin in chemically induced models of insulin-deficient diabetes. The current study sought to extend the technique to an autoimmune-mediated T1D model and document the underlying mechanisms. In nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice, BAT transplants result in complete reversal of T1D associated with rapid and long-lasting euglycemia. In addition, BAT transplants placed prior to the onset of diabetes on NOD mice can prevent or significantly delay the onset of diabetes. As with streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic models, euglycemia is independent of insulin and strongly correlates with decrease of inflammation and increase of adipokines. Plasma insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) is the first hormone to increase following BAT transplants. Adipose tissue of transplant recipients consistently express IGF-I compared with little or no expression in controls, and plasma IGF-I levels show a direct negative correlation with glucose, glucagon, and inflammatory cytokines. Adipogenic and anti-inflammatory properties of IGF-I may stimulate regeneration of new healthy white adipose tissue, which in turn secretes hypoglycemic adipokines that substitute for insulin. IGF-I can also directly decrease blood glucose through activating insulin receptor. These data demonstrate the potential for insulin-independent reversal of autoimmune-induced T1D with BAT transplants and implicate IGF-I as a likely mediator in the resulting equilibrium.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, brown adipose tissue, insulin independent, transplantation, insulin-like growth factor I

type 1 diabetes (T1D) is characterized by autoimmune-mediated destruction of pancreatic β-cells, resulting in absolute deficiency of insulin and loss of glycemic control. Treatments for T1D, despite having been refined over many years, are geared mainly toward replacing insulin, which involves numerous risks and limitations. Direct insulin replacement via daily injections or insulin pump does not cure the disease and requires life-long repeated administration. In addition to the inconvenience, direct insulin therapy requires careful monitoring of dosage and blood glucose levels and can lead to potentially fatal hypoglycemic episodes. Pancreas transplantation, the only available treatment with a good chance of long-term insulin independence, requires invasive surgery and life-long immunosuppressive therapy. Islet transplantation, although less invasive, is limited by the availability of donor tissue and the need for immunosuppression, and patients often return to insulin dependence in the long term. Thus, the need for better therapies remains.

A major goal in treating T1D is to reestablish normal glucose homeostasis. For almost a century this has been accomplished by insulin treatment, but recent work in rodents has shown that euglycemia can be achieved in the absence of insulin, notably through the use of leptin (36, 69, 74). We demonstrated another alternative for restoring euglycemia in diabetic mice independent of insulin (26–28). Brown adipose tissue (BAT) transplants placed in the subcutaneous space of streptozotocin (STZ)-diabetic mice result in weight gain, replenishment of subcutaneous white adipose tissue (WAT), return to euglycemia, and reversal of clinical diabetes with no contribution from insulin (27). Glucose homeostasis appears to be achieved by a chronic equilibrium of alternative hormones arising from newly formed subcutaneous WAT. The present study was aimed at extending the technique to mouse models of autoimmune diabetes more closely related to human T1D and documenting the mechanisms of insulin-independent glycemic regulation brought about by BAT transplants.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

BAT transplants were performed as described previously (27) in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice or STZ-induced diabetic C57BL/6 mice. Although most of the experiments were performed on NOD recipients, a few were repeated on C57BL/6 recipients for comparison purposes. Donor adipose tissue came from gestational age E15–E18 C57BL/6 embryos. Weight was recorded, and nonfasting blood samples were collected before and at regular intervals after BAT transplants (i.e., every week for the 1st month following transplant and every month thereafter) compared with normal nondiabetic control mice and untreated diabetic control mice with or without sham surgery. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests were performed before and after BAT transplants. Metabolic parameters such as blood glucose, insulin, adiponectin, leptin, glucagon, and IGF-I and plasma inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) were measured from transplant and control groups at regular intervals. BAT transplant mice were euthanized at different time points after 3 mo, and tissues were collected postmortem. Pancreata were tested for insulin content by immunohistochemistry and radioimmunoassay (RIA), and WAT was examined for signs of inflammation by immunohistochemistry. In a separate set of NOD mice, glucose uptake by peripheral tissues in the presence and absence of BAT transplants was monitored with glucose clamp studies.

Animals.

Recipients of the curative BAT transplants were female NOD mice (stock no. 001976; Jackson Laboratories) or STZ-treated C57BL/6 males (Harlan) at 4–6 mo of age. Recipients of preventive BAT transplants were female NOD mice at 8–10 wk of age. Donor embryonic BAT was obtained from C57BL/6 embryos at gestational age E15–E18. Parents were purchased from Harlan and maintained in the Vanderbilt Animal Care Facility. Animals were fed standard laboratory chow and cared for according to the guidelines of the Vanderbilt Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which approved our study.

Isolation of donor tissue.

Pregnant females were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine (110:10 mg/kg ip). A bilateral subcostal incision was made and extended by a midline transverse incision to expose the abdominal cavity. Uterine horns were exposed one at a time. Starting near the ovary, a longitudinal incision was made along the uterine horn. Embryos were removed quickly and placed in sterile, ice-cold Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). The mouse was immediately euthanized by cervical dislocation. The embryos were rapidly dissected with Dumont forceps, and the embryonic BAT from the interscapular region was removed and placed in sterile, ice-cold HBSS and transplanted into recipients as quickly as possible.

Transplantation.

Freshly isolated embryonic BAT was transplanted into diabetic recipients underneath the skin of the dorsal body surface. Through a small (1–2 mm) incision, a subcutaneous pocket was made by blunt dissection using a blunt-ended microspatula. Donor tissue was introduced into the pocket with Dumont forceps and pushed in with a blunt-ended microspatula. The incision was closed by gentle pressure with hemostats without sutures. Four to six lobules of embryonic BAT were introduced into each recipient. Surgeries were performed under general anesthesia with ketamine-xylazine (110:10 mg/kg ip), and postoperative analgesia is provided with 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 sc ketoprofen as necessary.

Metabolic parameters.

NOD mice with fasting blood glucose levels >200 mg/dl were selected as curative transplant candidates, whereas preventive transplants were performed on normoglycemic NOD mice prior to onset of diabetes. The possibility of spontaneous return to euglycemia was controlled by monitoring plasma insulin levels and pancreatic insulin content postmortem. Only those mice that showed progressively declining plasma insulin levels and drastically low pancreatic insulin content were included in the study. Blood samples were collected from a tail nick under isoflurane-oxygen anesthesia for measurement of glucose, insulin, and other hormones. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests were performed before and after transplant. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests involved blood collection from 6-h-fasted mice prior to (0 min) and 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after ip injection of sterile glucose (2 g/kg body wt; Sigma) under isoflurane-oxygen anesthesia. Basal nonfasting blood samples were also collected before transplant at weekly intervals after transplant for the first month and at monthly intervals thereafter. Plasma samples were analyzed for insulin, adiponectin, leptin, glucagon, and IGF-I, as well as the proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and MCP-1, with Luminex assays at the Vanderbilt Hormone Assay Core.

Postmortem tissue collection.

Nonfasted mice were euthanized at different time points between 3 and 9 mo after transplantation, and adipose tissue and pancreas were harvested for histology and insulin measurements. The whole pancreas and the WAT from the subcutaneous space of the dorsal body surface were collected from BAT transplant groups as well as normal and diabetic control groups. Pancreata were washed in PBS, blotted to remove moisture, weighed, and placed in acid ethanol for extraction of insulin. For histological analysis, tissues were preserved in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

Pancreatic insulin content.

Pancreata were homogenized in acid-ethanol and placed on a shaker at 4°C for 48 h. Tissue extracts were centrifuged for 30 min at 4°C at 2,500 rpm, and supernatants were collected and analyzed for insulin with radioimmunoassay.

Histology.

Histological sections of pancreata were immunostained for insulin and glucagon, and adipose tissue sections were immunostained for IGF-I. To verify the inflammatory status of adipose tissue, histological sections were immunostained for the general macrophage marker F4/80 and M2 macrophage marker CD206. Immunohistochemistry was done in pancreata from four mice in the transplant group and two in each control group. Fifteen to 20 sections from each mouse were examined before it was concluded that there was no detectable insulin staining in the transplant group.

Glucose clamp studies.

One-day hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps were performed at the Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (MMPC), using established protocols (3, 6, 35, 44, 59). Briefly, NOD successful transplant recipients and untreated diabetic controls were outfitted with carotid and jugular catheters for blood sampling and administration of compounds and allowed to recover for 1 wk. During the clamp, [3H]glucose was infused throughout the experiment, and a bolus of 2-[14C]deoxyglucose was administered at 120 min. Blood samples were collected every 10 min for measurement of blood glucose levels and endogenous glucose production. Tissues were collected postmortem for assessment of glucose uptake by peripheral tissues. Since NOD mice tend to develop diabetes after 12 wk, it was not possible to set up an age-matched normal nondiabetic control group for the confirmed successful transplants whose age is >6 mo. Therefore, we used untreated diabetic controls of similar age as controls and stabilized glucose at the diabetic level during the clamps. Mice from the same batch were divided into transplant and control groups; transplants were placed soon after they developed diabetes with blood glucose >200 mg/dl, and transplant success was confirmed by blood glucose going below 150 mg/dl within 2 wk posttransplant and being maintained for ≥2 wk. Successful transplant recipients were sent to the MMPC 2–3 wk posttransplant, and clamps were performed 1–2 wk thereafter. The untreated control mice were sent to MMPC 2–3 wk after developing diabetes, and clamps were performed 1–2 wk thereafter.

Animal numbers and success rates.

Out of 90 NOD mice involved in the study, 26 were removed due to death during anesthesia or soon after recovery. Out of a total of 30 that received curative BAT transplants, 16 recovered from diabetes (successful transplants), whereas 14 did not (failed transplants), providing a 53% success rate. The initial set of curative BAT transplants included 20 mice, of which 10 were cured and 10 failed. Measurements of blood glucose and hormone levels over time were obtained from this first batch of transplants compared with failed transplants and untreated diabetic controls. Based on the results, we decided to perform glucose clamp studies, for which purpose a second set of 10 BAT transplants was done. This batch yielded six successful and four failed transplants. The second set of six successful transplants was sent to the MMPC for glucose clamp studies ∼2–3 wk posttransplant so that their blood parameters over time could not be recorded. Thus, although 16 of 30 curative transplants were successful, blood glucose and hormone measurements are available only for the first set of 10. The successful transplants achieved euglycemia within 2 wk of transplant and remained euglycemic until euthanasia at different end points ranging from 3 to 9 mo.

As described in the previous study, STZ-diabetic recipients of BAT transplants show a 70% success rate on average. In the current study, a total of 12 STZ-induced diabetic mice received transplants; nine of those recovered from diabetes and three did not, providing a 75% success rate. Of the 12 NOD mice that received preemptive transplants, one was removed due to persistently high insulin levels. Onset of diabetes was prevented or delayed in nine recipients. Out of 12 NOD mice who received sham surgeries, two were removed due to persistently high insulin levels.

The largest amount of perisurgery mortality was among the untreated diabetic control group involved in the glucose clamp study. The placement of carotid and jugular catheters is a relatively invasive procedure with an expected mortality rate of 50% in general. In the glucose clamp study, our BAT transplant recipients showed a 50% mortality rate, as expected (3 of 6), whereas the untreated diabetic control group had a 76% mortality rate (10 of 13). Of the rest, five mice died under anesthesia before BAT transplants could be placed, two more died within 1 day from surgery, and another five mice from the untreated diabetic group died before any blood parameters could be collected.

Statistical analysis.

Values are expressed as means ± SE. Specified groups in each experiment were compared using Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Around 12 wk of age, NOD female mice develop spontaneous diabetes with rapid progression, and if untreated they die within 2 mo from the onset of diabetes. Curative BAT transplants resulted in the rapid and complete reversal of diabetes in 53% of the recipients (16 of 30). Whereas the success rate was lower than that generally observed with STZ-diabetic mice (70%), reversal of diabetes occurred much faster in NOD mice, and glucose tolerance was restored to normal.

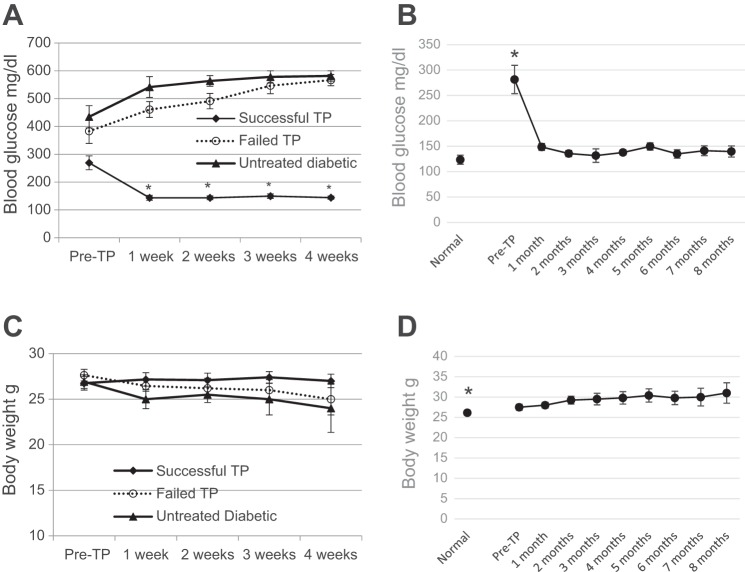

Diabetic NOD mice have basal nonfasting blood glucose >200 mg/dl, which quickly rises to >600 mg/dl within weeks. Successful BAT transplants are defined as those diabetic mice whose basal blood glucose levels decrease and stay below 150 mg/dl at any time following transplant. The successful transplant group showed rapid reversal of diabetes and marked improvement of glucose homeostasis (Fig. 1). These mice became euglycemic within 1 wk after receiving a BAT transplant and remained euglycemic until planned euthanasia at time points ranging from 3 to 8 mo (Fig. 1, A and B). This is in stark contrast to untreated diabetic control mice, which became severely hyperglycemic and had to be euthanized within 1–2 mo from the onset of diabetes (Fig. 1A). Thus, although the success rate is less, the quality of success is better with the NOD model than we observed previously with STZ-diabetic C57BL/6 mice. The severe weight loss associated with T1D is also reversed by BAT transplants. Similarly to the STZ-diabetic mice, as reported before (27), transplant recipients progressively gain weight and sometimes exceed the weight of their normal counterparts (Fig. 1D). The NOD control group included in Fig. 1D could not be age matched to the transplant recipients because most NOD mice develop diabetes after at 4 mo of age. However, it is noteworthy that the average body weight of the successful NOD transplant recipients at the 8-mo time point (31.8 ± 1.5) is significantly different from normal female C57Bl/6 mice of equivalent age (27.375 ± 0.7).

Fig. 1.

Brown adipose tissue (BAT) transplants (TP) restore glucose homeostasis and body weight in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. A: nonfasting blood glucose levels before and at weekly intervals following BAT TP compared with untreated diabetic controls. Successful TP recipients (●) achieve and maintain euglycemia within 1 wk from TP, whereas diabetic controls (▲) and failed TP (○) become progressively hyperglycemic; n = 10. *P < 0.005 when the successful TP group is compared with other groups at corresponding time points or with their own pre-TP values. B: nonfasting blood glucose levels at monthly intervals in the successful TP group compared with normal nondiabetic controls; n = 10 at ≤2 mo, n = 8 at 3–6 mo, and n = 6 beyond 7 mo in the TP group; n = 8 in the control group; *P < 0.005 when pre-TP time point is compared with each post-TP time point or with normal control. C: body weight before and at weekly intervals following BAT TP compared with untreated diabetic controls. Successful TP recipients maintain pre-TP weight, whereas diabetic controls and failed TP progressively lose weight; n = 10. There was no significant difference between groups. D: body weight at monthly intervals in the successful TP group compared with normal nondiabetic controls; n = 10 at ≤2 mo, n = 8 at 3–6 mo, and n = 6 beyond 7 mo in the TP group; n = 8 in the control group. *P < 0.05 when post-TP values are compared with normal control or 5- and 8-mo time points are compared with pre-TP condition.

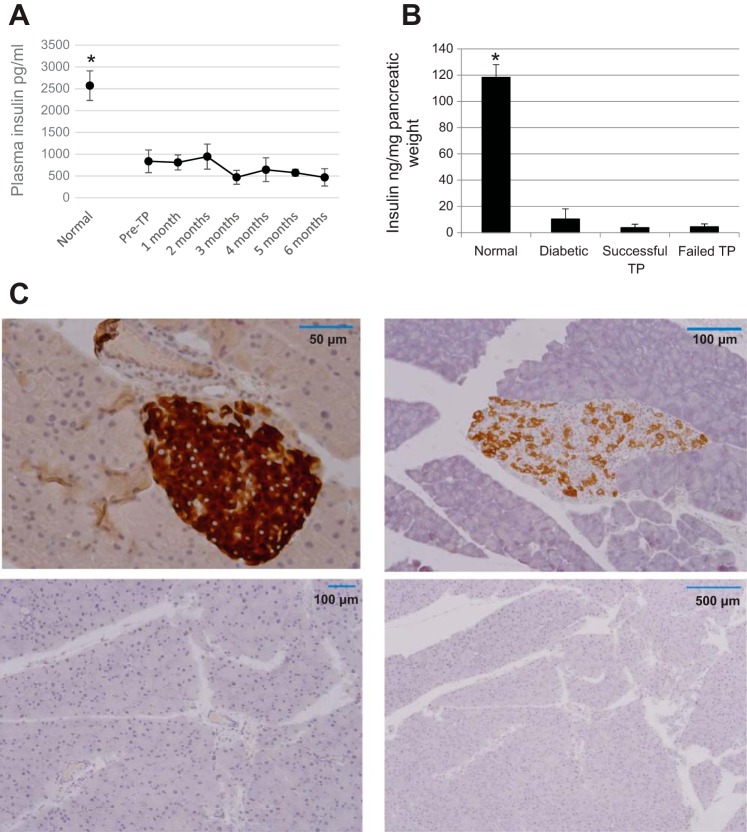

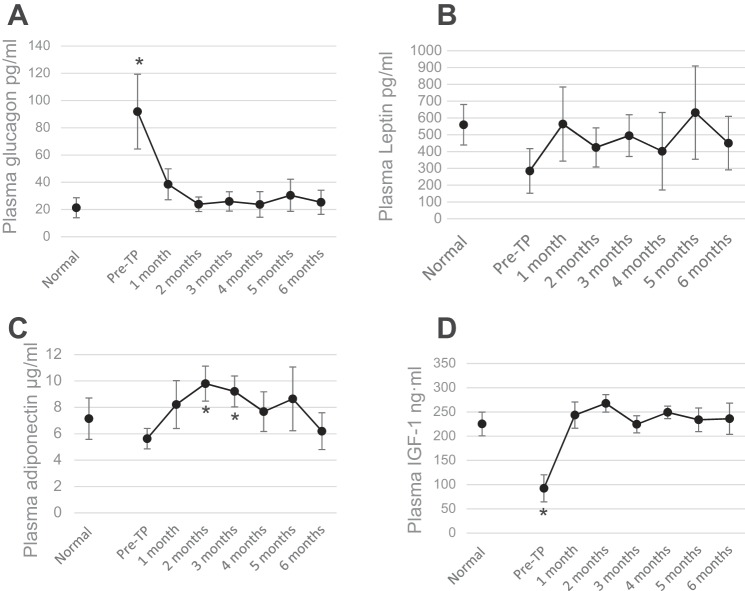

These results are independent of insulin, as indicated by drastically low levels of plasma insulin and nearly undetectable pancreatic insulin content postmortem (Fig. 2, A and B). Pancreatic sections in diabetic control mice have little immunostaining for insulin, whereas successful transplant recipients who remained euglycemic for 6 mo show none at all (Fig. 2C). As reported previously with STZ-diabetic models, there is strong suppression of glucagon and a progressive increase in plasma levels of IGF-I (Fig. 3). The steepest changes in both hormones occur during the first month posttransplant, during which time diabetes is reversed and euglycemia is established. Unlike with the STZ model, adiponectin did not show a strong and persistent increase in the NOD mice, and leptin did not show any significant increase.

Fig. 2.

Effects of BAT TP are independent of insulin. A: plasma insulin levels at monthly intervals in the successful TP group compared with normal nondiabetic controls; n = 8. *P < 0.01 when any time point in the TP group is compared with normal control. B: pancreatic insulin content postmortem in each group; n = 6. *P < 0.005 when each group is compared with normal nondiabetic controls. C: pancreatic sections immunostained for insulin (brown). Top left: normal nondiabetic control; top right: untreated diabetic control; bottom left: 6 mo post-TP; bottom right: larger area of same at lower magnification. Insulin staining is deficient in diabetic control and absent in the TP.

Fig. 3.

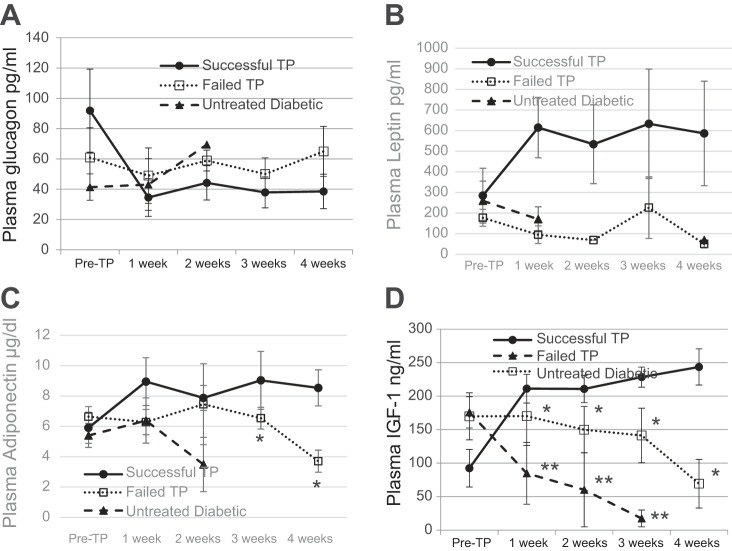

BAT TP are followed by progressive increases of plasma adipokines and suppression of glucagon. Plasma levels of glucagon (A), leptin (B), adiponectin (C), and IGF-I (D) before and at monthly intervals following TP compared with normal nondiabetic control group; n = 8. *P < 0.05 when pre-TP condition is compared with all other conditions (for glucagon and IGF-I) and when pretransplant condition is compared with 2- and 3-mo time points post-TP (for adiponectin).

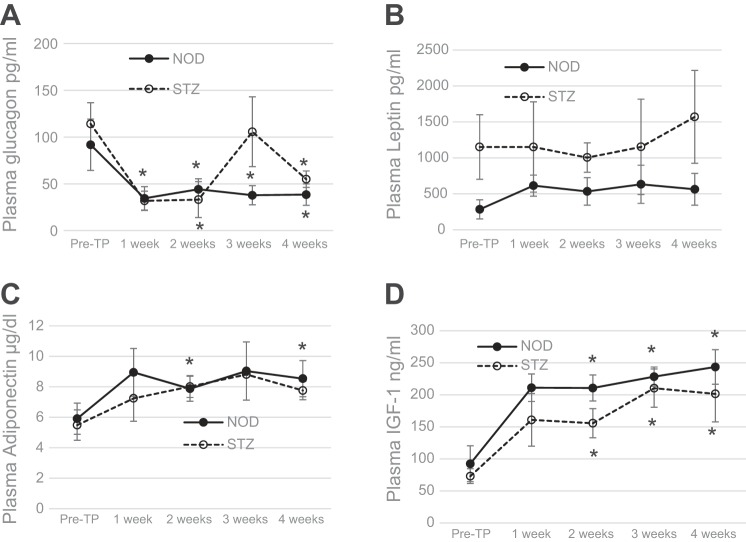

T1D is characterized by severe loss of subcutaneous WAT as well as inflammation of what little WAT that remains. Recovery from diabetes following BAT transplants is associated with decrease in inflammation and robust replenishment of WAT (27). Although NOD mice show immediate improvement in blood glucose, significant recovery of body weight occurs only after 4 wk posttransplant (Fig. 1), whereas in STZ-diabetic mice both improvements take 2–4 wk (27). Thus it is likely that stimuli from the BAT transplants trigger changes in the surrounding tissue that lead to adipogenesis, weight gain, secretion of beneficial adipokines, decreased inflammation, and improved glucose homeostasis. To determine which factor(s) is responsible for these functions in the early stages following transplant, we monitored the plasma levels of adipokines in the first 4 wk following BAT transplant. During this early period, plasma leptin shows no significant increase, plasma adiponectin shows a small but significant increase only in NOD mice, and plasma IGF-I shows a large and significant increase in both the NOD and STZ-treated groups (Fig. 4). The increase in IGF-I is sharp and progressive, in stark contrast to the untreated diabetic controls and failed transplants, and continues to increase in the following months (Figs. 3 and 5). Several studies show that metabolic disease is associated with decrease in IGF-I levels, whereas the underlying mechanisms are not yet known (54).

Fig. 4.

BAT transplants are followed by early increases in plasma adipokines and suppression of glucagon. Plasma levels of glucagon, leptin, adiponectin, and IGF-I during the first 4 wk post-TP. ●, NOD; ○, streptozotocoin (STZ)-treated C57BL/6 mice; n = 6 for NOD, n = 4 for STZ. *P < 0.05 when pretransplant condition is compared with 2, 3, and 4 wk post-TP in both groups (IGF-I), when pretransplant condition is compared with 2 and 4 wk post-TP in the NOD group (adiponectin), and when pretransplant condition is compared with each post-TP time point in the NOD group and 1- and 2-wk time points in the STZ group (glucagon).

Fig. 5.

Plasma adipokine levels in successful TP recipients in the first 4 wk post-TP compared with untreated diabetic control and failed TP groups; n = 6. *P < 0.05 when weeks 3 and 4 are compared between successful and failed TP (adiponectin) and when all time points post-TP are compared between successful and failed TP (IGF-I); **P < 0.01 when all time points post-TP are compared between successful TP and untreated diabetic controls.

The suppression of glucagon in the months following transplant is consistent in both NOD and STZ-diabetic mice (Fig. 3) (27). In Fig. 5, some values for the untreated diabetic group are missing due to inadequate sample volume and limitations of Luminex assays.

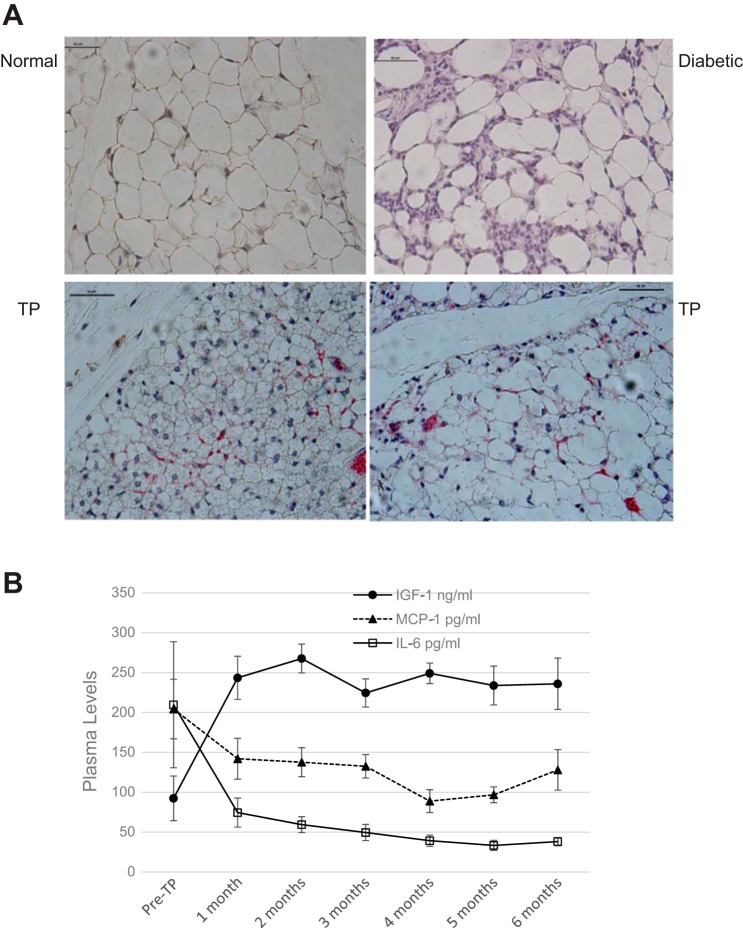

Recovery from diabetes is associated with replenishment of subcutaneous WAT and marked decrease in inflammation. As described previously, adipose tissue from diabetic mice shows signs of inflammation, including large adipocytes, disruption of cell membranes, and increased expression of inflammatory markers such as TNFα and IL-6 (27). These signs are absent in the adipose tissue of BAT transplant recipients who are euglycemic. As recent studies show, residential M2 macrophages are a more specific indicator of decrease in adipose tissue inflammation (16, 18). Subcutaneous WAT of transplant recipients shows increased amounts of residential M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages that are almost undetectable in normal and diabetic controls (Fig. 6). T1D is also characterized by inflammation of endogenous BAT with excessive macrophage infiltration and shrinkage of adipose tissue, which is reversed following BAT transplant (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

BAT transplants are associated with decrease in adipose tissue inflammation. A: sections of subcutaneous adipose tissue from NOD mice stained with F4/80 (brown) for all macrophages and CD206 (red) for M2 macrophages. Scale bars, 60 μm. Top left: normal control; top right: diabetic control; bottom right and bottom left: successful TP characterized by smaller adipocytes overall, BAT morphology in many adipocytes, and increased staining for CD206. B: increase in plasma IGF-I levels correlates with the decrease in proinflammatory cytokines. Plasma levels of IGF-I (●), IL-6 (□), and monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1; ▲) before and at monthly intervals following BAT transplants; n = 8. P < 0.05 when the pre-TP values for each factor are compared with corresponding post-TP values.

T1D is associated with generalized systemic inflammation as well, as indicated by increased plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and MCP-1. Following BAT transplant in both STZ-diabetic and NOD models, plasma inflammatory markers progressively decrease with time, in direct negative correlation with the progressive increase in IGF-I (Fig. 6). Thus it is likely that the adipogenic and anti-inflammatory properties of IGF-I enable the early decrease in inflammation and proliferation of WAT, which in turn would secrete other beneficial adipokines that collectively compensate for the function of insulin. The untreated diabetic group and the failed transplant group were severely hyperglycemic by 4 wk and either died or had to be euthanized soon after. Therefore, monthly values for inflammatory markers could not be collected for these groups. As with glucagon, the values for IL-6 and MCP-1 in the first 4 wk showed no significant difference between the three groups.

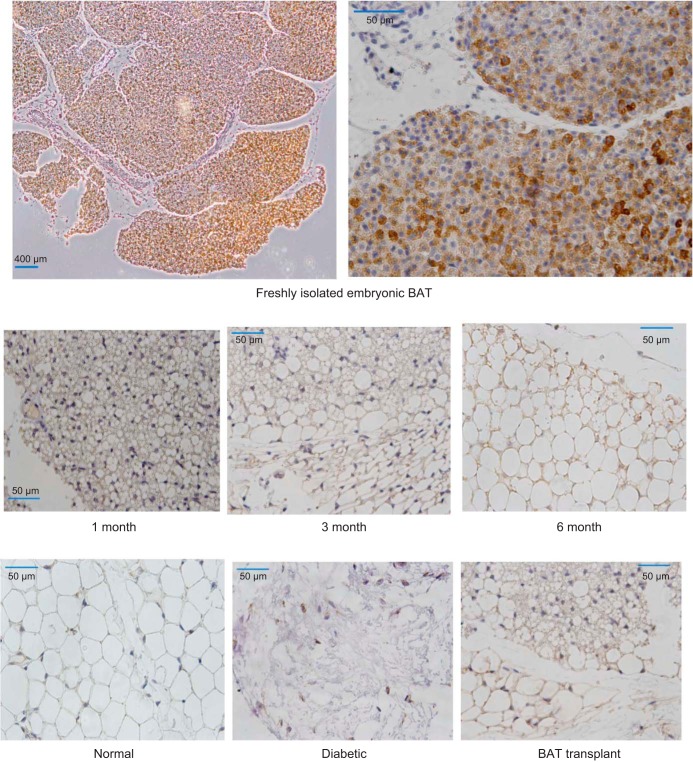

The initial source of IGF-I may be the transplanted embryonic BAT, since freshly isolated BAT shows abundant expression of IGF-I (Fig. 7, top). However, both the transplanted BAT as well as the new WAT in the region surrounding transplant continue to express IGF-I for several months posttransplant (Fig. 7, middle). Such expression of IGF-I appears to be unique to transplant recipients, as the WAT in normal and diabetic controls expresses little or no IGF-I (Fig. 7, bottom).

Fig. 7.

Expression of IGF-I (diaminobenzidine staining; brown) in different tissue sections. Top: freshly isolated embryonic BAT. Middle: adipose tissue in the BAT TP area at different time points from STZ-diabetic mice that became euglycemic following TP, showing consistent expression of IGF-I. Bottom: adipose tissue of normal and diabetic controls compared with 3-mo TP. IGF-I expression is evident only in the TP recipient.

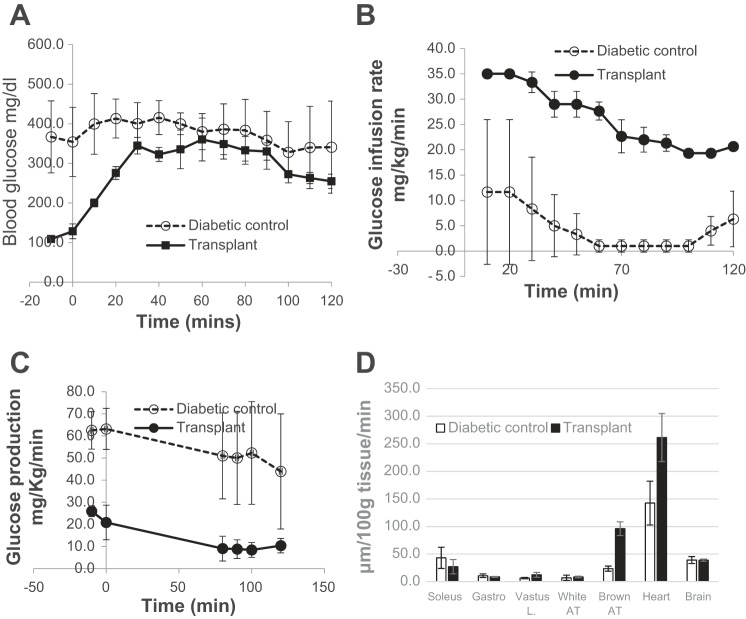

As indicated by the significantly greater glucose infusion rates required during euglycemic clamp, BAT transplant recipients exhibit more efficient glucose handling (Fig. 8). Their endogenous glucose production was low, as were basal glucose levels. Glucose is taken up not only by the liver but also by muscle (vastus lateralis), brown adipose tissue, and heart (Fig. 8), confirming the findings of recent studies on adult BAT transplant (62).

Fig. 8.

Glucose uptake and metabolism are more efficient in BAT TP recipients. Hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps performed on NOD successful TP recipients and untreated diabetic controls. Glucose infusion rate (B) is significantly higher in the TP group compared with diabetic control group, whereas blood glucose (A) and endogenous glucose production (C) are significantly lower. D: glucose uptake by peripheral tissues. In the TP group, glucose uptake by the heart and BAT were significantly higher than in the control group, whereas the other tissues showed no difference; n = 3. A: P < 0.03 from −20 to 40 min. B: P < 0.0001 for all time points. C: P < 0.01 from −20 to 0 min, P < 0.08 from 80 to 120 min. D: P < 0.0001 for BAT, P < 0.07 for heart.

Fourteen of 30 transplants (47%) failed to reverse diabetes. The failed transplant mice became progressively hyperglycemic, similar to the untreated diabetic control groups, and had to be euthanized within 6 wk. A comparison of their blood parameters with the successful transplant group showed an early decline of plasma leptin, adiponectin, and IGF-I levels (Fig. 5), confirming the importance of these hormones in insulin-independent glucose regulation. There was no correlation between transplant success and the amount of BAT transplanted (which was roughly similar for each recipient) or the gestational age of donor tissue (E15–E18). A factor that appeared to influence the outcome was the time between the isolation of donor tissue and transplantation into the recipient. Each pregnancy would yield donor tissue for two to three transplants. Freshly isolated embryonic BAT was placed in ice-cold HBSS and transplanted into each recipient as soon as possible. In our experience, the first recipient from each set (who received the transplant within 10 min of isolation) was more likely to recover from diabetes than the second or third recipients, who received tissue within 15–20 min from isolation.

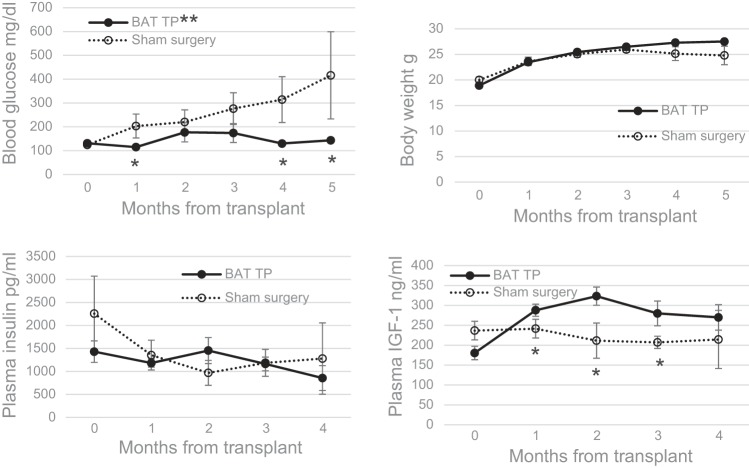

To determine the ability of BAT transplants to prevent or delay the onset of diabetes, transplants were performed on normoglycemic NOD female mice at 7–10 wk of age prior to onset of diabetes. This group of preventive BAT transplant recipients was compared with an age-matched control group that received sham surgeries at 7–10 wk of age. Three of 24 mice were removed from the study due to persistently high plasma insulin levels, and only those NOD mice showing progressively declining plasma insulin and drastically low pancreatic insulin content postmortem were included in the study. All mice in the control group who received sham surgeries became diabetic soon after 12 wk of age, as is typical of NOD mice, and showed progressive hyperglycemia (Fig. 9). Of the 11 recipients of preventive BAT transplants, five remained euglycemic beyond 6 mo, two became diabetic around the same time as the sham surgery group, and four became diabetic after 3 mo posttransplant, considerably later than the sham surgery group. There were significant differences when the mean blood glucose values of the transplant group were compared with those of the sham surgery group as well as when several corresponding time points were compared between the two groups. (Fig. 9) Other hormones showed progressive changes similar to those observed in curative transplants, although the increases in plasma leptin and adiponectin were not significant. IGF-I levels showed a progressive and significant increase, in contrast to low or decreasing levels in the control group (Fig. 9). The decline of IGF-I in the sham sugery group was not as pronounced as in the untreated diabetic controls or failed transplants observed earlier (Fig. 5), likely because the sham surgery group was in the beginning stages of diabetes.

Fig. 9.

BAT TP prevent the onset of diabetes in NOD mice. TP were performed on normoglycemic NOD female mice at 7–10 wk of age prior to onset of diabetes. Blood parameters were compared with a control group that received sham surgeries at 7–10 wk of age. Blood glucose (A), body weight (B), plasma insulin (C), and plasma IGF-I (D) before and at monthly intervals following BAT TP compared with sham surgery group; n = 11 for BAT TP group, n = 10 for sham surgery group. *P < 0.05 when blood glucose values are compared between groups at 1-, 4-, and 5-mo time points and when plasma IGF-I values are compared at 1–3 mo; **P < 0.02 when the mean glucose values in the BAT TP group over time are compared with those of the sham surgery group.

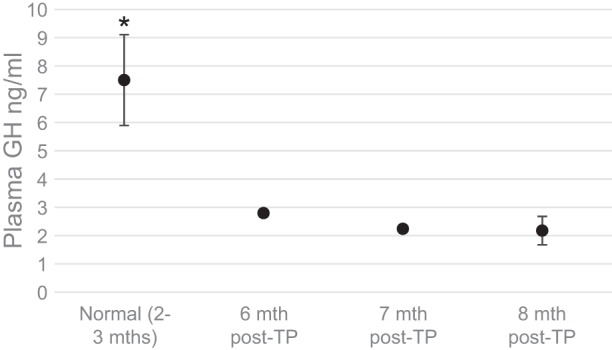

To determine whether the increase in IGF-I was mediated through the GH-IGF-I axis, we compared plasma growth hormone (GH) levels of the remaining NOD transplant recipients at 8–9 mo of age with 2- to 3-mo-old normal nondiabetic NOD mice (Fig. 10). The average GH level in younger mice was significantly greater (7.5 ± 1.6 ng/ml) compared with the transplant recipients, who were older by several months (2.4 ± 0.18 ng/ml). It is noteworthy that the predictable decline of GH with age was observed in the transplant group despite the increase in IGF-I. The GH levels in the transplant group also showed a progressive decline over the 3 mo tested, although this decrease was small and not significant. According to these preliminary results, the increase in IGF-I occurs independent of the GH axis. This conclusion is supported by the observations in a recent study in humans where diet-induced correction of type 2 diabetes (T2D) was associated with increased IGF-I without an increase in GH (20).

Fig. 10.

Plasma growth hormone (GH) levels in NOD transplant recipients compared with normal controls. GH levels in preventive BAT TP recipients euglycemic at 6, 7, and 8 mo post-TP (n = 3) were compared with normal nondiabetic control mice at 8–12 wk of age (n = 8). *P < 0.05 when each transplant group is compared with normal controls. ●, plasma GH level for each condition denoted in the x-axis.

DISCUSSION

The current data confirm the results of our previous work and establish the feasibility of reversing and preventing autoimmune T1D independent of insulin. As previous studies show, chemically induced models of insulin-deficient diabetes retain some ability to regenerate β-cells (25, 73). Thus, even with drastically low plasma insulin levels and pancreatic insulin content, as reported in our earlier studies (26–28), the possibility of some contribution from insulin could not be discounted. The autoimmune-induced NOD mouse model helps minimize the possible contribution from insulin. NOD mice show severe and irreversible insulitis resulting in absolute deficiency of insulin. Plasma insulin levels in NOD mice progressively decrease, and pancreatic insulin postmortem is undetectable in both failed and successful transplants, which is in stark contrast to nondiabetic control animals (Fig. 2). Average plasma insulin levels in transplant recipients (857.71 ± 89.23) are not significantly different from those of untreated diabetic controls (956.46 ± 284.02), whereas glucose uptake and utilization are remarkably more efficient, as demonstrated in the glucose clamp studies (Fig. 8). Thus the reversal of diabetes and long-lasting euglycemia in NOD mice following BAT transplants cannot be attributed to residual insulin alone. An increase in insulin sensitivity may still play a role in addition to insulin-independent mechanisms, considering that BAT transplant recipients show increased glucose uptake in the heart and decreased hepatic glucose output (Fig. 8). Since early placement of BAT transplants can prevent or delay the onset of diabetes, it is likely that the autoimmune response is decreased by the BAT transplant, as evidenced by consistent suppression of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and MCP-1.

As reported previously with STZ-diabetic models, it appears that a chronic equilibrium of alternate hormones originating from adipose tissue replaces the function of insulin. The STZ model shows progressively increasing leptin and adiponectin levels, increases that are particularly pronounced at 6 mo posttransplant (27). In the NOD model the increase in adiponectin was not very pronounced, whereas leptin showed no significant change. (Figs. 3 and 4). Both models showed a significant increase in IGF-I and suppression of glucagon. IGF-I levels start out below 100 ng/ml in both models and increase to 200–250 ng/ml. This increase happens rapidly in the NOD model, with a steep increase during the first month, and slowly and progressively in the STZ model (data not shown). Thus it appears that a combination of endogenous hormones are important for both models, where adiponectin and leptin are predominant in the STZ model and IGF-I is predominant in the NOD model.

Inflammation is an innate characteristic of T1D, as it is with other metabolic disease such as obesity, insulin resistance, and T2D (2, 5, 11, 13, 40, 43, 60, 64). Recovery from metabolic disease is associated with decreased inflammation, both systemic and in adipose tissue (17, 37, 52, 55, 57, 58, 67, 78). Insulin-independent reversal of T1D following BAT transplants follows a similar pattern, resulting in a progressive decrease in inflammation both systemically and in adipose tissue (26–28). Important changes include suppression of glucagon, progressive decrease of proinflammatory cytokines, replenishment of healthy adipose tissue, and progressive increases in plasma adiponectin, leptin, and IGF-I. Among the earliest changes following BAT transplant placement is a sharp increase in IGF-I, which continues to stay elevated in direct negative correlation with glucagon and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and MCP-1 (Fig. 6) (28). As the literature shows, IGF-I has strong adipogenic and anti-inflammatory properties (21, 24, 30, 32, 66, 70, 75, 80), as does adiponectin (14, 47, 63, 68), whereas leptin is known to be proinflammatory and adipolytic (7, 14, 47). IL-6, another cytokine known to have proinflammmatory and adipolytic properties (34, 40, 42), was also consistently decreased following BAT transplants. Considering the net increase in body weight observed in all mouse strains following BAT transplants (Fig. 2) (27), adiponectin and IGF-I are likely to exert stronger effects on the overall equilibrium. Other reported benefits of IGF-I include repair of damaged tissue, inhibition of apoptosis, improved wound healing, angiogenesis, and cell proliferation (4, 12, 21, 30, 32, 39, 66, 70, 75), all of which are important in the regeneration of healthy adipose tissue in T1D.

IGF-I is abundantly expressed in freshly isolated embryonic BAT. Once the transplant is placed in the subcutaneous tissue, both the BAT transplant and the WAT near the transplant continue to express IGF-I for months, in contrast to normal and diabetic controls, which express little or none (Fig. 7). A possible result of this early increase in IGF-I is the characteristic weight gain and replenishment of WAT that occurs 1 mo posttransplant, accompanied by the progressive decrease in proinflammatory cytokines that shows a direct negative correlation to IGF-I levels (Fig. 6). The importance of IGF-I is further implicated by the fact that failed transplants show a progressive decrease in IGF-I (Fig. 5), and one successful transplant mouse that reverted to diabetes at 8 mo showed a sudden concomitant drop in IGF-I along with marked increases in glucagon, IL-6, and MCP-1 (data not shown). Thus IGF-I appears to be critical in establishing and maintaining metabolic homeostasis in the absence of insulin. Unlike the observations in recent studies with adult BAT transplants (81), our embryonic BAT transplants could not be distinguished after the first month posttransplant with either the naked eye or microscopy. Possible reasons are the small size of the embryonic BAT and the likelihood that it blends into newly formed subcutaneous WAT in the surrounding region.

In addition to decreasing inflammation and stimulating regeneration of new WAT, IGF-I may also contribute to glucose homeostasis through insulin-independent glucose uptake into peripheral tissues via GLUT1 and GLUT3 glucose transporters (9, 15, 82) as well as direct activation of the insulin receptor. There is considerable structural similarity between the receptors for insulin and IGF-I (29, 38). As shown previously, acute inhibition of insulin receptor partially impairs glucose tolerance in BAT transplant recipients, indicating a direct action of IGF-I in glucose metabolism (27). Recent studies show that metabolic disease is associated with subnormal IGF-I levels and that diet-induced reversal of T2D is accompanied by an increase in IGF-I levels (20, 54).

Given the aforementioned beneficial effects of IGF-I, it is a reasonable speculation that exogenous administration of IGF-I may mimic the effects of BAT transplants. However, human studies with recombinant IGF-I treatment, although beneficial in alleviating diabetes and insulin resistance, require supraphysiological doses that carry many harmful side effects (1, 8, 50, 51, 53, 65). Also, reversal of diabetes was not complete or permanent, and concomitant insulin therapy is required in addition to IGF-I. A recent study on NOD mice demonstrates that administration of the adenovirus vector-mediated IGF-I gene showed no significant reduction in insulitis, blood glucose, or body weight (77). Another study where recombinant human IGF-I was administered to T2D mice shows some decrease in blood glucose through decreased hepatic gluconeogenesis but no improvement in insulin sensitivity or glucose tolerance (49). Based on these data, it appears that monotherapy with IGF-I would not be adequate to reproduce the results of BAT transplants, which may exert their effects through a combination of embryonic factors in addition to IGF-I. Our current data indicate IGF-I plays a major role in this equilibrium, whereas all other factors involved are as yet unidentified. Our future directions include identifying such factors using mass spectrometry on media conditioned with freshly isolated BAT and verifying the importance of IGF-I by transplanting donor BAT from an IGF-I knockout model.

The importance of BAT in metabolic homeostasis has been reported in a number of studies that consistently demonstrate the ability of BAT to improve glucose homeostasis and energy expenditure and decrease obesity (10, 22, 23, 56, 61, 62, 71, 76). Recent studies show promise in adult BAT transplants in alleviating T2D and obesity. Glucose tolerance in diet-induced obese mice is significantly improved through transplantation of inguinal fat pads from healthy donors into the subcutaneous space of recipient mice (62). High-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice were reversed by visceral or subcutaneous transplantation of healthy adult BAT in addition to improvements in glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, and fat mass (81). Mechanisms include increased glucose uptake into peripheral tissues, increased sympathetic activity, and elevated levels of BAT-derived signaling molecules such as fibrobast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and IL-6.

An apparent difference in our findings is the weight gain following BAT transplants, as opposed to the widely known antiobesity effects of BAT. It should be noted, however, that BAT transplants lead to a healthy weight in the T1D recipients rather than obesity. Metabolic disease leads to unhealthy adipose tissue, the quantity of which tends to be sparse in T1D while abundant in obesity or T2D. BAT seems to convert unhealthy fat back to a healthy state in both situations. Stanford et al. (62) demonstrated a beneficial role for BAT-derived IL-6, where BAT transplants from IL-6 knockout donors failed to improve glucose homeostasis or reduce obesity in T2D recipients. In contrast we observed a progressive decrease in plasma IL-6 in T1D recipients who became euglycemic following BAT transplants, whereas untreated diabetic controls or failed transplants had high levels of IL-6. It is noteworthy, however, that the plasma levels of IL-6 in the successful transplant recipients observed by Stanford et al. (62) were similar to ours (20–50 pg/ml), whereas the diabetic controls in each study were drastically different. T1D controls with or without sham surgery in our study showed higher levels of plasma IL-6, whereas T2D controls in the previous study (sham, bead, or WAT) showed lower levels of plasma IL-6. Thus, it is possible that a function of BAT is to normalize plasma IL-6 levels. It is also possible that embryonic BAT transplants may act differently from the adult BAT transplants used in the Stanford et al. (62) study. Adult BAT transplants have been unsuccessful in reversing T1D in our hands, indicating that correction of T1D requires a specific factor(s) derived from embryonic tissue.

Although the current data demonstrate the ability of BAT transplants to correct autoimmune diabetes without insulin, the success rates were less than reported previously (27) with STZ-diabetic models. Decrease in inflammation and regeneration of adipose tissue are critical processes in insulin-independent reversal of T1D requiring specific embryonic factors originating from the BAT transplant. It seems likely that failed transplants did not generate adequate amounts of anti-inflammatory and adipogenic factors to regenerate and maintain healthy adipose tissue. Plasma levels of IGF-I, adiponectin, and leptin in the failed transplant group showed a progressive decline, in sharp contrast to the successful transplants (Fig. 5). There may be other embryonic factors as yet unidentified that are also critical in tissue repair and regeneration and exerting the adipogenic and anti-inflammatory effects along with IGF-I. It is noteworthy that embryonic BAT only from C57BL/6 donors but not from NOD donors was successful in reversing T1D in NOD mice. Considering the innate widespread inflammation present in NOD mice, it is likely that their embryonic tissue lacks the critical factors present in C57BL6 embryos necessary to stimulate the healing processes. Future directions include identifying such factors and using exogenous administration of those factors to enable adult adipose tissue transplants to behave in a manner similar to embryonic BAT and correct diabetes. A likely candidate is FGF21, which is known to possess adipogenic and anti-inflammatory properties and is expressed in BAT and embryonic tissue. Other possible alternatives to embryonic BAT include BAT-derived stem cell lines, which have shown some success in reversing T1D in preliminary studies.

Although specific factors such as IGF-I and adiponectin are critical in insulin-independent reversal of T1D, safe and effective maintenance of glucose homeostasis requires a combination of endogenously generated hormones. Monotherapy with exogenous IGF-I, adiponectin, or leptin has been shown to be effective in reversing diabetes to varying degrees (1, 8, 14, 19, 31, 33, 36, 41, 45–51, 53, 65, 69, 74). However, correction of diabetes was only partial in many of these instances, and monotherapy with any single hormone carries potentially dangerous adverse effects, as with insulin. In addition, there may be other important contributors to metabolic regulation originating from healthy adipose tissue that are as yet unidentified. Once the success rates of this technique are optimized and suitable alternatives to embryonic tissue are established, insulin-independent reversal of diabetes using adipose tissue can become a realistic option.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Iacocca Family Foundation and the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. Microscopy was supported by the Vanderbilt Cell Imaging Shared Resource (CA-68485, DK-58404, and DK-020593), glucose clamp studies were performed by the Vanderbilt Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (DK-059637), hormone measurements were performed in the Diabetes Center Hormone Assay Core Laboratory (DK-020593), and tissue was processed by the Translational Pathology Shared Resource.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.C.G. and D.W.P. conception and design of research; S.C.G. performed experiments; S.C.G. analyzed data; S.C.G. and D.W.P. interpreted results of experiments; S.C.G. prepared figures; S.C.G. drafted manuscript; S.C.G. and D.W.P. edited and revised manuscript; S.C.G. and D.W.P. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acerini CL, Patton CM, Savage MO, Kernell A, Westphal O, Dunger DB. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of human recombinant insulin-like growth factor I plus intensive insulin therapy in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lancet 350: 1199–1204, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Attie AD, Scherer PE. Adipocyte metabolism and obesity. J Lipid Res 50 Suppl: S395–S399, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. Considerations in the design of hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamps in the conscious mouse. Diabetes 55: 390–397, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aydin F, Kaya A, Karapinar L, Kumbaraci M, Imerci A, Karapinar H, Karakuzu C, Incesu M. IGF-1 Increases with Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy and Promotes Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J Diabetes Res 2013: 567834, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Review Circ Res 96: 939–949, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berglund ED, Li CY, Poffenberger G, Ayala JE, Fueger PT, Willis SE, Jewell MM, Powers AC, Wasserman DH. Glucose metabolism in vivo in four commonly used inbred mouse strains. Diabetes 57: 1790–1799, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlton ED, Demas GE, French SS. Leptin, a neuroendocrine mediator of immune responses, inflammation, and sickness behaviors. Horm Behav 62: 272–279, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemmons DR. Metabolic actions of insulin-like growth factor-I in normal physiology and diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 41: 425–443, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copland JA, Pardini AW, Wood TG, Yin D, Green A, Bodenburg YH, Urban RJ, Stuart CA. IGF-1 controls GLUT3 expression in muscle via the transcriptional factor Sp1. Biochim Biophys Acta 1769: 631–640, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cypess AM, Kahn CR. Brown fat as a therapy for obesity and diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 17: 143–149, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan BB, Schmidt MI. The epidemiology of low-grade chronic systemic inflammation and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 8: 7–17, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emmerson E, Campbell L, Davies FC, Ross NL, Ashcroft GS, Krust A, Chambon P, Hardman MJ. Insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes wound healing in estrogen-deprived mice: new insights into cutaneous IGF-1R/ERα cross talk. J Invest Dermatol 132: 2838–2848, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erbağci AB, Tarakçioğlu M, Coşkun Y, Sivasli E, Sibel Namiduru E. Mediators of inflammation in children with type I diabetes mellitus: cytokines in type I diabetic children. Clin Biochem 34: 645–650, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falcão-Pires I, Castro-Chaves P, Miranda-Silva D, Lourenço AP, Leite-Moreira AF. Physiological, pathological and potential therapeutic roles of adipokines. Drug Discov Today 17: 880–889, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fladeby C, Skar R, Serck-Hanssen G. Distinct regulation of glucose transport and GLUT1/GLUT3 transporters by glucose deprivation and IGF-I in chromaffin cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1593: 201–208, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer-Posovszky P, Wang QA, Asterholm IW, Rutkowski JM, Scherer PE. Targeted deletion of adipocytes by apoptosis leads to adipose tissue recruitment of alternatively activated M2 macrophages. Endocrinology 152: 3074–3081, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher G, Hyatt TC, Hunter GR, Oster RA, Desmond RA, Gower BA. Markers of inflammation and fat distribution following weight loss in African-American and white women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20: 715–720, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujisaka S, Usui I, Bukhari A, Ikutani M, Oya T, Kanatani Y, Tsuneyama K, Nagai Y, Takatsu K, Urakaze M, Kobayashi M, Tobe K. Regulatory mechanisms for adipose tissue M1 and M2 macrophages in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 58: 2574–2582, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukushima M, Hattori Y, Tsukada H, Koga K, Kajiwara E, Kawano K, Kobayashi T, Kamata K, Maitani Y. Adiponectin gene therapy of streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice using hydrodynamic injection. J Gene Med 9: 976–985, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ. Effect of a high-protein diet on ghrelin, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factor-I and binding proteins 1 and 3 in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 60: 1300–1311, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh MC, Gorantla V, Makena PS, Luellen C, Sinclair SE, Schwingshackl A, Waters CM. Insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates differentiation of ATII cells to ATI-like cells through activation of Wnt5a. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L222–L228, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginter E, Simko V. Brown fat tissue - a potential target to combat obesity. Bratisl Lek Listy 113: 52–56, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gómez-Hernández A, Otero YF, de las Heras N, Escribano O, Cachofeiro V, Lahera V, Benito M. Brown fat lipoatrophy and increased visceral adiposity through a concerted adipocytokines overexpression induces vascular insulin resistance and dysfunction. Endocrinology 153: 1242–1255, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grohmann M, Sabin M, Holly J, Shield J, Crowne E, Stewart C. Characterization of differentiated subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue from children: the influences of TNF-alpha and IGF-I. J Lipid Res 46: 93–103, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman EJ, Lee DD, Tao J, Wilson RA, Park SY, Bell GI, Chong AS. Glycemic control promotes pancreatic beta-cell regeneration in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. PLoS One 5: e8749, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunawardana SC. Adipose tissue, hormones and treatment of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 12: 542–550, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gunawardana SC, Piston DW. Reversal of type 1 diabetes in mice by brown adipose tissue transplant. Diabetes 61: 674–682, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunawardana SC, Piston DW. Insulin-independent reversal of type-1 diabetes with brown adipose tissue transplants: Involvement of IGF-1 (Abstract). International Pancreas and Islet Transplant Association, 14th World Congress 244, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen BF, Glendorf T, Hegelund AC, Lundby A, Lützen A, Slaaby R, Stidsen CE. Molecular characterisation of long-acting insulin analogues in comparison with human insulin, IGF-1 and insulin X10. PLoS One 7: e34274, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holly J, Sabin M, Perks C, Shield J. Adipogenesis and IGF-1. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 4: 43–50, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu X, She M, Hou H, Li Q, Shen Q, Luo Y, Yin W. Adiponectin decreases plasma glucose and improves insulin sensitivity in diabetic swine. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 39: 131–136, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin E, Kim JM, Kim SW. Priming of mononuclear cells with a combination of growth factors enhances wound healing via high angiogenic and engraftment capabilities. J Cell Mol Med 17: 1644–1651, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandasamy AD, Sung MM, Boisvenue JJ, Barr AJ, Dyck JR. Adiponectin gene therapy ameliorates high-fat, high-sucrose diet-induced metabolic perturbations in mice. Nutr Diabetes 2: e45, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S, Jin Y, Choi Y, Park T. Resveratrol exerts anti-obesity effects via mechanisms involving down-regulation of adipogenic and inflammatory processes in mice. Biochem Pharmacol 81: 1343–1351, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraegen EW, Jenkins AB, Storlien LH, Chisholm DJ. Tracer studies of in vivo insulin action and glucose metabolism in individual peripheral tissues. Horm Metab Res Suppl 24: 41–48, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kruger AJ, Yang C, Lipson KL, Pino SC, Leif JH, Hogan CM, Whalen BJ, Guberski DL, Lee Y, Unger RH, Greiner DL, Rossini AA, Bortell R. Leptin treatment confers clinical benefit at multiple stages of virally induced type 1 diabetes in BB rats. Autoimmunity 44: 137–148, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee H, Lee IS, Choue R. Obesity, inflammation and diet. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 16: 143–152, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LeRoith D, Yakar S. Mechanisms of disease: metabolic effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3: 302–310, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Shelat H, Geng YJ. IGF-1 prevents oxidative stress induced-apoptosis in induced pluripotent stem cells which is mediated by microRNA-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 426: 615–619, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L, Wu LL. Adiponectin and interleukin-6 in inflammation-associated disease. Vitam Horm 90: 375–395, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma Y, Liu D. Hydrodynamic delivery of adiponectin and adiponectin receptor 2 gene blocks high-fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Gene Ther 20: 846–852, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathis D. Immunological goings-on in visceral adipose tissue. Cell Metab 17: 851–859, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirza S, Hossain M, Mathews C, Martinez P, Pino P, Gay JL, Rentfro A, McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP. Type 2-diabetes is associated with elevated levels of TNF-alpha, IL-6 and adiponectin and low levels of leptin in a population of Mexican Americans: a cross-sectional study. Cytokine 57: 136–142, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muniyappa R, Lee S, Chen H, Quon MJ. Current approaches for assessing insulin sensitivity and resistance in vivo: advantages, limitations, and appropriate usage. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E15–E26, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nan MH, Park JS, Myung CS. Construction of adiponectin-encoding plasmid DNA and gene therapy of non-obese type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Drug Target 18: 67–77, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naito M, Fujikura J, Ebihara K, Miyanaga F, Yokoi H, Kusakabe T, Yamamoto Y, Son C, Mukoyama M, Hosoda K, Nakao K. Therapeutic impact of leptin on diabetes, diabetic complications, and longevity in insulin-deficient diabetic mice. Diabetes 60: 2265–2273, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 85–97, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park S, Kim DS, Kwon DY, Yang HJ. Long-term central infusion of adiponectin improves energy and glucose homeostasis by decreasing fat storage and suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis without changing food intake. J Neuroendocrinol 23: 687–698, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pennisi P, Gavrilova O, Setser-Portas J, Jou W, Santopietro S, Clemmons D, Yakar S, LeRoith D. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I treatment inhibits gluconeogenesis in a transgenic mouse model of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinology 147: 2619–2630, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quattrin T, Thrailkill K, Baker L, Litton J, Dwigun K, Rearson M, Poppenheimer M, Giltinan D, Gesundheit N, Martha P Jr. Dual hormonal replacement with insulin and recombinant human insulin like growth factor I in IDDM. Effects on glycemic control, IGF-I levels, and safety profile. Diabetes Care 20: 374–380, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Quattrin T, Thrailkill K, Baker L, Kuntze J, Compton P, Martha P; rhIGF-I in IDDM Study Group. Improvement of HbA1c without increased hypoglycemia in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus treated with recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin. rhIGF-I in IDDM Study Group. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 14: 267–277, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raghow R. Bariatric surgery-mediated weight loss and its metabolic consequences for type-2 diabetes. World J Diabetes 4: 47–50, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Regan FM, Williams RM, McDonald A, Umpleby AM, Acerini CL, O'Rahilly S, Hovorka R, Semple RK, Dunger DB. Treatment with recombinant human insulin-like growth factor (rhIGF)-I/rhIGF binding protein-3 complex improves metabolic control in subjects with severe insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 2113–2122, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ren J, Anversa P. The insulin-like growth factor I system: physiological and pathophysiological implication in cardiovascular diseases associated with metabolic syndrome. Biochem Pharmacol 93: 409–417, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rolland C, Hession M, Broom I. Effect of weight loss on adipokine levels in obese patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 4: 315–323, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roman S, Agil A, Peran M, Alvaro-Galue E, Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Fernández-Vázquez G, Marchal JA. Brown adipose tissue and novel therapeutic approaches to treat metabolic disorders. Transl Res 165: 464–479, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santos J, Salgado P, Santos C, Mendes P, Saavedra J, Baldaque P, Monteiro L, Costa E. Effect of bariatric surgery on weight loss, inflammation, iron metabolism, and lipid profile. Scand J Surg 103: 21–25, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneck AS, Iannelli A, Patouraux S, Rousseau D, Bonnafous S, Bailly-Maitre B, Le Thuc O, Rovere C, Panaia-Ferrari P, Anty R, Tran A, Gual P, Gugenheim J. Effects of sleeve gastrectomy in high fat diet-induced obese mice: respective role of reduced caloric intake, white adipose tissue inflammation and changes in adipose tissue and ectopic fat depots. Surg Endosc 28: 592–602, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saccà L, Orofino G, Petrone A, Vigorito C. Differential roles of splanchnic and peripheral tissues in the pathogenesis of impaired glucose tolerance. J Clin Invest 73: 1683–1687, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shelbaya S, Amer H, Seddik S, Allah AA, Sabry IM, Mohamed T, El Mosely M. Study of the role of interleukin-6 and highly sensitive C-reactive protein in diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetic patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 16: 176–182, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Skarulis MC, Celi FS, Mueller E, Zemskova M, Malek R, Hugendubler L, Cochran C, Solomon J, Chen C, Gorden P. Thyroid hormone induced brown adipose tissue and amelioration of diabetes in a patient with extreme insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 256–262, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stanford KI, Middelbeek RJ, Townsend KL, An D, Nygaard EB, Hitchcox KM, Markan KR, Nakano K, Hirshman MF, Tseng YH, Goodyear LJ. Brown adipose tissue regulates glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Invest 123: 215–223, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tao C, Sifuentes A, Holland WL. Regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis by adiponectin: effects on hepatocytes, pancreatic β cells and adipocytes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 28: 43–58, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taube A, Schlich R, Sell H, Eckardt K, Eckel J. Inflammation and metabolic dysfunction: links to cardiovascular diseases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302: H2148–H2165, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thrailkill KM, Quattrin T, Baker L, Kuntze JE, Compton PG, Martha PM Jr. Cotherapy with recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I and insulin improves glycemic control in type 1 diabetes. RhIGF-I in IDDM Study Group. Diabetes Care 22: 585–592, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vivar R, Humeres C, Varela M, Ayala P, Guzmán N, Olmedo I, Catalán M, Boza P, Muñoz C, Díaz Araya G. Cardiac fibroblast death by ischemia/reperfusion is partially inhibited by IGF-1 through both PI3K/Akt and MEK-ERK pathways. Exp Mol Pathol 93: 1–7, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Viardot A, Lord RV, Samaras K. The effects of weight loss and gastric banding on the innate and adaptive immune system in type 2 diabetes and prediabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 2845–2850, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wanders D, Graff EC, White BD, Judd RL. Niacin increases adiponectin and decreases adipose tissue inflammation in high fat diet-fed mice. PLoS One 8: e71285, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang MY, Chen L, Clark GO, Lee Y, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva OR, Wenner BR, Bain JR, Charron MJ, Newgard CB, Unger RH. Leptin therapy in insulin-deficient type I diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 4813–4819, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang XQ, Lee S, Wilson H, Seeger M, Iordanov H, Gatla N, Whittington A, Bach D, Lu JY, Paller AS. Ganglioside GM3 depletion reverses impaired wound healing in diabetic mice by activating IGF-1 and insulin receptors. J Invest Dermatol 134: 1446–1455, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu C, Cheng W, Sun Y, Dang Y, Gong F, Zhu H, Li N, Li F, Zhu Z. Activating brown adipose tissue for weight loss and lowering of blood glucose levels: a microPET study using obese and diabetic model mice. PLoS One 9: e113742, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang B, Zhou L, Peng B, Sun Z, Dai Y, Zheng J. In vitro comparative evaluation of recombinant growth factors for tissue engineering of bladder in patients with neurogenic bladder. J Surg Res 186: 63–72, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yin D, Tao J, Lee DD, Shen J, Hara M, Lopez J, Kuznetsov A, Philipson LH, Chong AS. Recovery of islet beta-cell function in streptozotocin- induced diabetic mice: an indirect role for the spleen. Diabetes 55: 3256–3263, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yu X, Park BH, Wang MY, Wang ZV, Unger RH. Making insulin-deficient type 1 diabetic rodents thrive without insulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 14070–14075, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu X, Xing C, Pan Y, Ma H, Zhang J, Li W. IGF-1 alleviates ox-LDL-induced inflammation via reducing HMGB1 release in HAECs. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 44: 746–751, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zafrir B. Brown adipose tissue: research milestones of a potential player in human energy balance and obesity. Horm Metab Res 45: 774–785, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang L, Chen Y, Li C, Lin X, Cheng X, Li T. Protective effects of combined intervention with adenovirus vector mediated IL-10 and IGF-1 genes on endogenous islet β cells in nonobese diabetes mice with onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One 9: e92616, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang H, Wang Y, Zhang J, Potter BJ, Sowers JR, Zhang C. Bariatric surgery reduces visceral adipose inflammation and improves endothelial function in type 2 diabetic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2063–2069, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang CC, Zhou JS, Hu JG, Wang X, Zhou XS, Sun BA, Shao C, Lin Q. Effects of IGF-1 on IL-1β-induced apoptosis in rabbit nucleus pulposus cells in vitro. Mol Med Rep 7: 441–444, 2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhao P, Deng Y, Gu P, Wang Y, Zhou H, Hu Y, Chen P, Fan X. Insulin-like growth factor 1 promotes the proliferation and adipogenesis of orbital adipose-derived stromal cells in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. Exp Eye Res 107: 65–73, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhu Z, Spicer EG, Gavini CK, Goudjo-Ako AJ, Novak CM, Shi H. Enhanced sympathetic activity in mice with brown adipose tissue transplantation (transBATation). Physiol Behav 125C: 21–29, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zoidis E, Ghirlanda-Keller C, Schmid C. Stimulation of glucose transport in osteoblastic cells by parathyroid hormone and insulin-like growth factor I. Mol Cell Biochem 348: 33–42, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]