Abstract

Cough is a reflex that serves to protect the airways. Excessive or chronic coughing is a major health issue that is poorly controlled by current therapeutics. Significant effort has been made to understand the mechanisms underlying the cough reflex. The focus of this review is the evidence supporting the role of specific airway sensory nerve (afferent) populations in the initiation and modulation of the cough reflex in health and disease.

Introduction

Cough is an airway reflex in guinea pigs and larger mammals that serves to expel unwanted matter from the airways. Stimuli induce cough by activating afferent (sensory) nerves innervating the airways. These signals are transmitted centrally via the vagus nerve, where they synapse with networks in the brainstem (e.g. nucleus tractus solitarius (nTS)). Such networks coordinate the activation of motor output (e.g. phrenic, intercostal and recurrent laryngeal nerves (RLN)) and the ultimate expression of cough. The focus of this review will be the afferent nerves involved in cough: their characterization, activation and function.

Key to the understanding of afferents involved in cough is the use of specific stimuli to evoke cough experimentally. In anesthetized animals cough is evoked by mechanical stimulation (i.e. punctate) of the larynx, trachea and main bronchi [1, 2]. This cough rapidly adapts to continued pressure, although repeated stimulation will evoke further coughs. Application of water and critic acid to these airways also evokes cough in anesthetized animals [3–5]. Interestingly, cough can be evoked by many other stimuli in conscious animals (but not in anesthetized animals). Thus inhalation of irritants such as bradykinin, capsaicin, cinnamaldehyde and acrolein evokes cough [1, 6–, 10, 11*], as can bronchoconstricting agents [12–14]. Regardless of which receptors are involved, afferent activation depends on the gating of membrane ion channels at the airway afferent terminal. This leads to nerve depolarization (graded potential), which triggers the activation of voltage-gated sodium channels (NaV) and the initiation of action potentials, that conduct towards the brainstem [15, 16*].

Afferent innervation of the larynx, trachea, bronchi and intrapulmonary airways is largely supplied by the vagus nerve and its branches (e.g. RLN and superior laryngeal nerve (SLN)). The vagal ganglia comprises of the nodose and jugular ganglia, whose afferent neurons arise from distinct embryological sources (placodes and neural crest, respectively) [17]. Such differences manifest themselves in differential protein expression and functionality [18, 19]. Airway afferents are not homogenous and numerous subtypes have been determined. Details of these subtypes can be found elsewhere [5, 15, 20, 21], here we will focus on two important groups: the nodose Aδ fibers innervating the extrapulmonary airways and the vagal C fibers innervating throughout the airways. Both groups can be considered ‘nociceptive’ – afferents that do not respond to eupneic breathing and other ‘normal’ events, but which respond specifically to stimuli that can be considered noxious (or potentially noxious) [22].

Nodose Aδ activation

Highly arborized nerve terminals are found innervating the smooth muscle layer of the extrapulmonary airways [2, 23]. These are the peripheral terminals of myelinated afferents originating exclusively from the nodose ganglion. Electrophysiological recordings indicate conduction velocities of approximately 5m/s (Aδ fibers) [24, 25]. These afferents are exquisitely sensitive to punctate mechanical force, but not stretch. Acidic solutions, hypotonic and hypertonic solutions also activate extrapulmonary nodose Aδ fiber terminals [24, 26]. Responses to continued punctate force or acidic solutions rapidly ceases (adaptation) [27]. Aδ fibers in healthy animals are completely insensitive to bradykinin and capsaicin (selective agonist of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1)) [1, 24], due to a lack of TRPV1 expression [28**].

Nodose Aδ fibers innervating the trachea and larynx are carried by the RLN branch of the vagus [24]. Bilateral transection of the RLN interrupts Aδ fiber signaling [2, 24] and cough evoked in anesthetized guinea pigs by stimulation of the trachea [1, 2, 29]. SLN transection had no effect on Aδ fiber signaling/cough. Recently, a more specific approach has indicated the contribution of nodose Aδ fibers to cough [30**]. NaV1.7, a vagal voltage-gated sodium channel, has been shown to be critical for action potential discharge in vagal afferents innervating the airways [31]. Using in vivo adeno-associated virus (AAV) delivery specifically to nodose neurons (jugular was not transfected) of shRNA targeted against NaV1.7, the overall electrical activity of nodose afferents was significantly reduced (jugular afferents were not reduced) [30**]. In these studies punctate stimulation (under anesthesia) of the trachea evoked 11 ± 3 coughs in control guinea pigs but only 2 ± 1 coughs in nodose NaV1.7 knockdown guinea pigs. Breathing rates were not different between the groups.

The receptors responsible for Aδ fiber activation have not been definitively determined. Acid activates both TRPV1 and a family of proteins termed the Acid-Sensing Ion Channels (ASIC) in sensory neurons. However, TRPV1 is not expressed in Aδ fibers and selective TRPV1 inhibitors have no effect on acid-induced Aδ fiber activation [26]. The mRNA for multiple ASICs have been found in nodose neurons [32*], but specific studies in airway afferents are lacking. Numerous candidates have been proposed for mediating mechanical-induced sensory nerve activation including EnaC, TRPV4, TRPA1, and Piezo [15, 33–36], but so far no definitive determinations have been made.

Characterizations of Aδ fiber terminals and their nodose soma suggest that these neurons represent a biochemically distinct neuronal subset [24, 37]. These neurons express neurofilament, neuronal nitric oxide synthase and vGlut1 and vGlut2 (transport glutamate into excitatory vesicles) but do not express substance P, CGRP or somatostatin (nociceptor neuropeptides). Interestingly, these fibers express the α3 subunit of the Na-K-ATPase pump, which is not found elsewhere within the trachea [2, 37]. Ouabain, at concentrations that preferentially block α3 subunit, inhibited the activation of tracheal Aδ fibers and inhibited cough evoked by tracheal stimulation in anesthetized guinea pigs [2]. Ouabain had no effect on basal breathing rates or on citric acid-induced apneas, suggesting a selective inhibition of tracheal Aδ fiber afferents.

Vagal C fiber activation

The vast majority of airway afferents are unmyelinated and conduct action potentials at 0.3–1.5 m/s (C fibers) [18, 38, 39]. C fibers terminate in unstructured endings throughout the mucosa and submucosa of the airways [2, 23, 40]. C fibers are polymodal sensors of noxious stimuli [18, 41–43], due to their characteristic expression of specific receptors for noxious stimuli. The hallmark of C fiber nociceptive afferents is sensitivity to capsaicin due to the expression of TRPV1 in nociceptors [44]. Capsaicin activates airway C fibers [18, 24, 38, 42, 43], and this is abolished by selective TRPV1 inhibitors and in TRPV1−/− mice [45–47]. Capsaicin does not evoke cough in anesthetized animals, although it does evoke apnea [1, 48–50]. In conscious animals capsaicin evokes cough that is reduced by TRPV1 inhibitors [7, 30**, 51–53]. Similar data are observed in humans, where capsaicin produces cough bouts and urge-to-cough sensations [6, 11].

TRPV1 itself is a polymodal receptor that is activated by heat and extracellular acidity [44]. Airway C fibers are activated by acid, in a manner that is partially inhibited by TRPV1 inhibition/knockout [26, 47]. Consistent with these findings, TRPV1 inhibitors reduce citric acid-induced cough in conscious guinea pigs [51, 54, 55]. The other mechanism(s) underlying acid-induced activation of airway C fibers is probably mediated by ASIC channels [32*, 56].

TRP ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) is commonly co-expressed with TRPV1. TRPA1 is activated by a host of noxious stimuli including cinnamaldehyde, allyl isothiocyanate (AITC, pungent ingredient of wasabi), H2O2ozone, cigarette smoke, dehydrated prostaglandins and products of lipid peroxidation and nitration [57–64]. This disparate group of substances all activate airway C fibers, in a manner than is abolished by inhibition or genetic knockout of TRPA1 [61, 64, 65]. Point mutation studies of TRPA1 suggest that a covalent modification of key intracellular cysteines by electrophilic moieties underlies much TRPA1’s activation by these activators [66, 67]. TRPA1 agonists evoke cough in conscious guinea pigs and humans, which is blocked by TRPA1 inhibitors [8, 9, 11, 30**, 68**].

TRPV1 and TRPA1 are also thought to contribute to nociceptor activation by GPCR ligands downstream of second messenger signaling [58, 69–71]. Bradykinin activates airway C fibers [18, 72], which is partially inhibited by TRPV1 inhibition/knockout [47, 73]. Other studies in dissociated nociceptive neurons suggest a role for TRPA1 in bradykinin-mediated responses [71, 74**]. In conscious animals bradykinin evokes cough [1, 75*], which is reduced by both TRPA1 and TRPV1 inhibitors [74**].

Both the nodose and the jugular vagal ganglia project C fibers to the airways [18, 24]. Jugular and nodose C fibers originate from different embryological sources [17], resulting in differential protein expression and function [18, 19, 24, 68**, 76, 77]. Nodose C fibers rarely express neuropeptides such as substance P and are activated by multiple stimuli including capsaicin, AITC, bradykinin, citric acid, α,β-methylene ATP (P2X2/3), adenosine (A1 and A2A) and 2-methyl 5HT (5HT3). Whereas jugular C fibers frequently express neuropeptides such as substance P and have a more limited range of stimuli sensitivity including capsaicin, AITC, bradykinin and citric acid. Jugular C fibers are not activated by α,β-methylene ATP, adenosine and 2-methyl 5HT due to a lack of specific receptor expression. Similarities in ligand sensitivity profiles [18, 38] suggest that afferent C fiber terminals accessible to stimulants injected into the pulmonary circulation (“pulmonary C fibers”) originate in the nodose ganglia. Whereas C fibers activated by stimulants injected into the bronchial/systemic circulation (“bronchial C fibers”) originate in the jugular ganglia.

Exposure of conscious guinea pigs to nebulized nodose C fiber-specific stimuli (e.g. ATP) failed to evoke cough [1, 30**]. This suggests that cough evoked by bradykinin, capsaicin or AITC is dependent solely on the activation of jugular C fibers. Such a hypothesis is supported by evidence that abolishing electrical activity using shRNA targeted to NaV1.7 in nodose nerves has no effect on capsaicin-induced cough. Given that cough is abolished with either bilateral vagotomy or with complete shRNA knockdown of NaV1.7 throughout the vagal ganglia [1, 31], it is reasonable to conclude that jugular C fibers are critical to cough triggered by C fiber stimulants.

Excitability changes in cough afferents

The transduction of graded potentials into action potential frequency depends on the electrical excitability of the afferent. In general, reducing K+ channel function and increasing NaV function will increase excitability [16, 78], whereas reducing NaV function and activating K+ channels may dampen airway afferent excitability [30**, 31, 79, 80**]. These changes in excitability are typically non-specific, i.e. they are independent of the ‘activating’ stimulus that produces the initial graded depolarization. Numerous inflammatory mediators, such as histamine, bradykinin and prostaglandins, have been shown to acutely increase nociceptor excitability [81–90]. Similarly, such mediators have been shown to increase the sensitivity of the cough reflex [83, 91–94]. Allergic inflammation has been shown to increase the sensitivity of Aδ fiber to punctate stimuli [25], although the mediators responsible for this effect are not known.

Cough afferent interactions

Central networks and mechanisms that regulate cough are beyond the scope of this review [95*, 96, 97*, 98, 99], but it is clear that cough mediated by nodose Aδ fibers and jugular C fibers are differentially sensitive to anesthesia, thus suggesting major differences. Nevertheless, activation of airway jugular C fibers (with capsaicin or bradykinin) augments Aδ fiber-mediated cough in anesthetized animals [50, 100]. This effect was mimicked by microinjection of capsaicin or substance P into the commissural nTS (airway C fiber central terminals) and prevented by microinjection of neurokinin antagonists [50, 101]. Esophageal C fibers also synapse in this area of the nTS and it is possible that activation of these nociceptors in the esophagus (e.g. acid) [102] may sensitize cough reflexes in similar ways [103].

Lung slowly adapting receptors are activated by mechanical forces during eupneic breathing and also by sustained positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). The role of these myelinated stretch receptors in modulating cough in anesthetized animals is perhaps species-specific: activity in SAR is permissive for cough in rabbits [104], inhibitory for cough in guinea pigs [3, 101] and has no effect on cough in humans [105].

Inhalation of nodose C fiber-specific stimulants (e.g. ATP) does not evoke cough in conscious animals. Indeed, it is thought that activation of pulmonary/nodose C fibers may inhibit cough elicited from the extrapulmonary airways in anesthetized animals [49](Y. L. Chou and B. J. Canning, unpublished observations).

Nasal inflammation has been shown to augment cough reflexes from the lower airways [106–108]. The nasal airways are innervated by trigeminal afferents, many of which are nociceptive (express TRPV1 and TRPA1) [60, 109–111]. Activation of nasal nociceptors with capsaicin or histamine failed to evoke cough [4, 5], but instead augmented cough sensitivity to vagal afferent stimulation [4, 112, 113]. Similar studies, however, with nasal TRPA1 agonists did not augment cough [114*]. Nasally-mediated cough augmentation was inhibited by intranasal treatment with the local anesthetic mesocain [113]. Convergence of capsaicin-sensitive trigeminal afferents with brainstem cough networks is suggested by c-fos staining in the nTS following intranasal capsaicin challenge [115].

TRP melastin 8 (TRPM8) is a menthol-sensitive cold receptor on a subpopulation of unmyelinated sensory neurons [116]. TRPM8 is found in both TRPV1+ and TRPV1-vagal and trigeminal neurons [111, 117**]. Nasal stimulation of TRPM8 with menthol, icilin or cold air profoundly decreased Aδ fiber-mediated cough in anesthetized guinea pigs [117**, 118*], whereas TRPM8 stimulation in the trachea had no effect on cough sensitivity.

Afferent plasticity

Neural protein expression is not static, and inflammation/disease-induced changes in specific protein expression in cough afferents could have significant effects on cough. In particular neurotrophins, which are produced within the airways are sites of inflammation and infection [119], are critical controllers of neuronal gene expression [120, 121]. De novo expression of neuropeptide substance P and CGRP in large diameter tracheal nodose neurons (presumed Aδ fibers) were observed following allergic inflammation [122], infection with sendai virus [123] and nerve growth factor (NGF)-beta injections into the tracheal wall [124]. Given that substance P released from jugular C fibers in the nTS augments Aδ fiber-mediated cough, it is reasonable to hypothesize that neuropeptides released centrally by the Aδ fiber itself may also increase cough reflexes. In addition, de novo expression of the capsaicin receptor TRPV1 caused by allergic inflammation has been observed in myelinated airway afferents [125], including tracheal-specific nodose neurons [28**].

Afferent sensitivity to neurotrophins is determined by expression of specific tropomyosin-receptor kinase (Trk) receptors [126]: TrkA (activated by NGF), TrkB (activated by brain-derived neurotrophin factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin 4 (NT-4)) and TrkC (activated by NT-3). A recent study demonstrated that jugular C fibers preferentially expressed TrkA and nodose Aδ fibers preferentially expressed TrkB [127]. As such it would be predicted that BDNF would have a greater impact on protein expression in nodose Aδ fibers than NGF. Indeed, BDNF evoked substantial de novo TRPV1 expression in these nerves, whereas the effect of NGF was not significant [28**]. NGF-mediated neuropeptide expression in nodose neurons is consistent with the limited expression of TrkA in this population. TRPV1 expression was also induced by glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [28**], which activates a family of receptors that are extensively expressed in airway afferents [127]. It is possible that de novo expression of TRPV1 (and perhaps other “C fiber” receptors) in the Aδ fiber population indicates a switch of this fiber type to a more polymodal afferent. Thus it is plausible that Aδ fibers (which stimulate cough even under anesthesia) in certain disease states could be activated by airway inflammation and inhaled irritants, thus potentiating cough.

Concluding Remarks

Anatomical, electrophysiological and pharmacological studies of multiple mammalian species indicate that there are two main afferent pathways that initiate cough: nodose Aδ fibers in the extrapulmonary airways and airway jugular C fibers. Nodose Aδ fibers respond to a limited range of stimuli that are consistent with a fundamental requirement to protect the airway from aspiration. Whereas jugular C fibers are adapted to respond to a host of stimuli associated with inflammation, infection and inhalation of irritants/pollutants. There is significant evidence that many airway afferent pathways interact within CNS networks to modulate cough (both positively and negatively). Furthermore, inflammation has been shown to produce both acute increases in afferent excitability and neuroplastic changes in afferent phenotype. Thus the tendency to cough in disease is likely modulated by a complex interaction of these many factors.

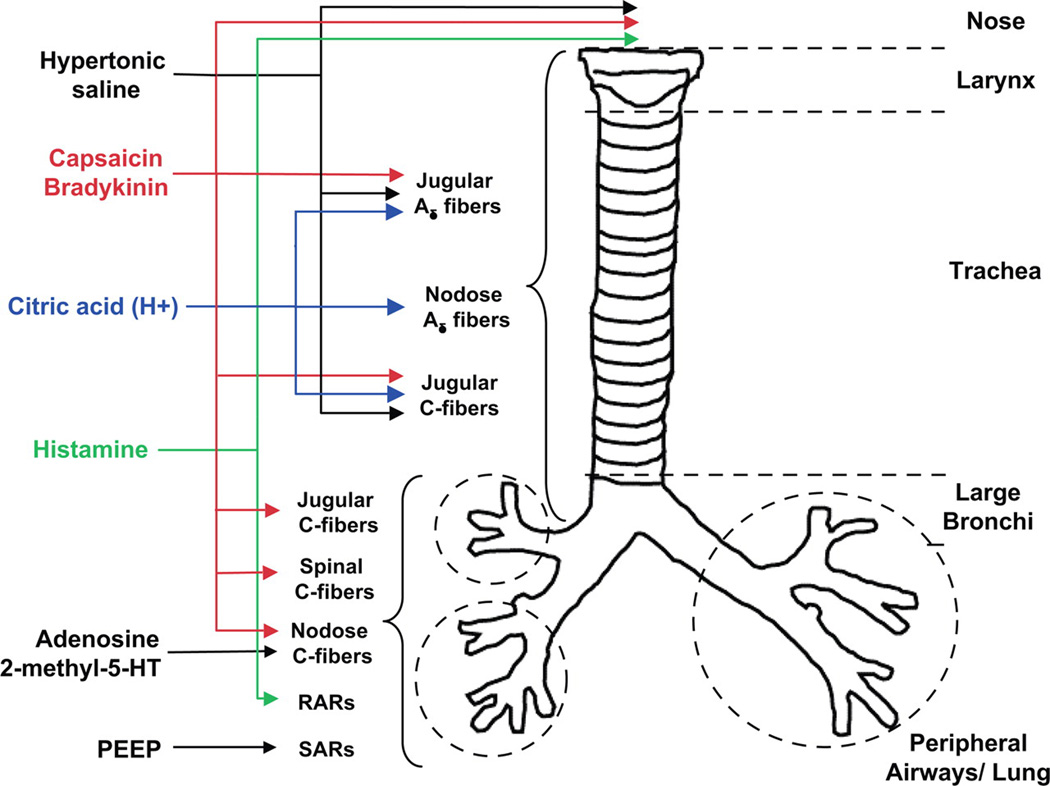

Figure 1.

The distribution and responsiveness of airway afferent subtypes in the guinea pig. RARs, rapidly adapting receptors; SARs, slowly adapting receptors. Taken from [5].

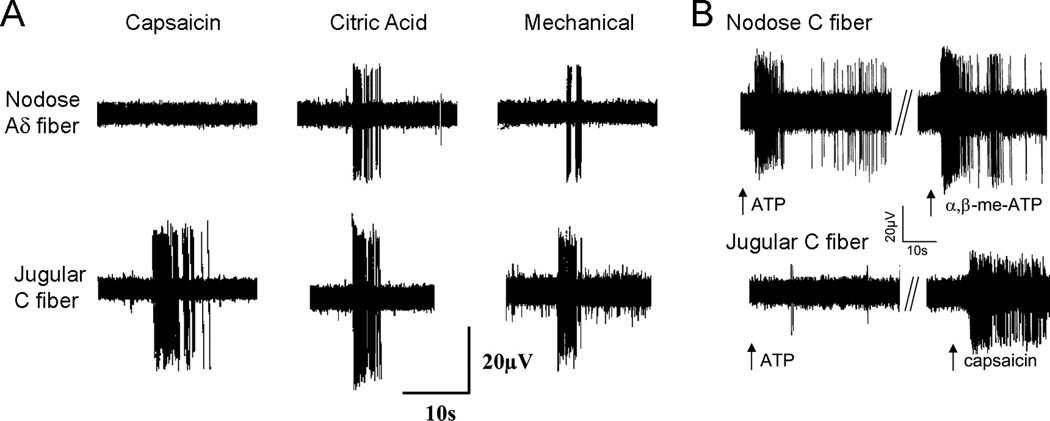

Figure 2.

Airway afferent subtypes have distinct sensitivities to various stimuli. A, representative recordings from tracheal afferents originating in the nodose ganglia (Aδ fiber) and jugular ganglia (C fiber) of guinea pigs. Responses to capsaicin (1µM), 0.1M citric acid and von Frey fiber punctate mechanical force are shown. Adapted from [1]. B, representative recordings from afferents originating in the nodose ganglia (C fiber) and jugular ganglia (C fiber) innervating the guinea pig lung. Responses to ATP (30µM), α,β-methylene ATP (30µM) and capsaicin (0.3µM) are shown. Adapted from [18].

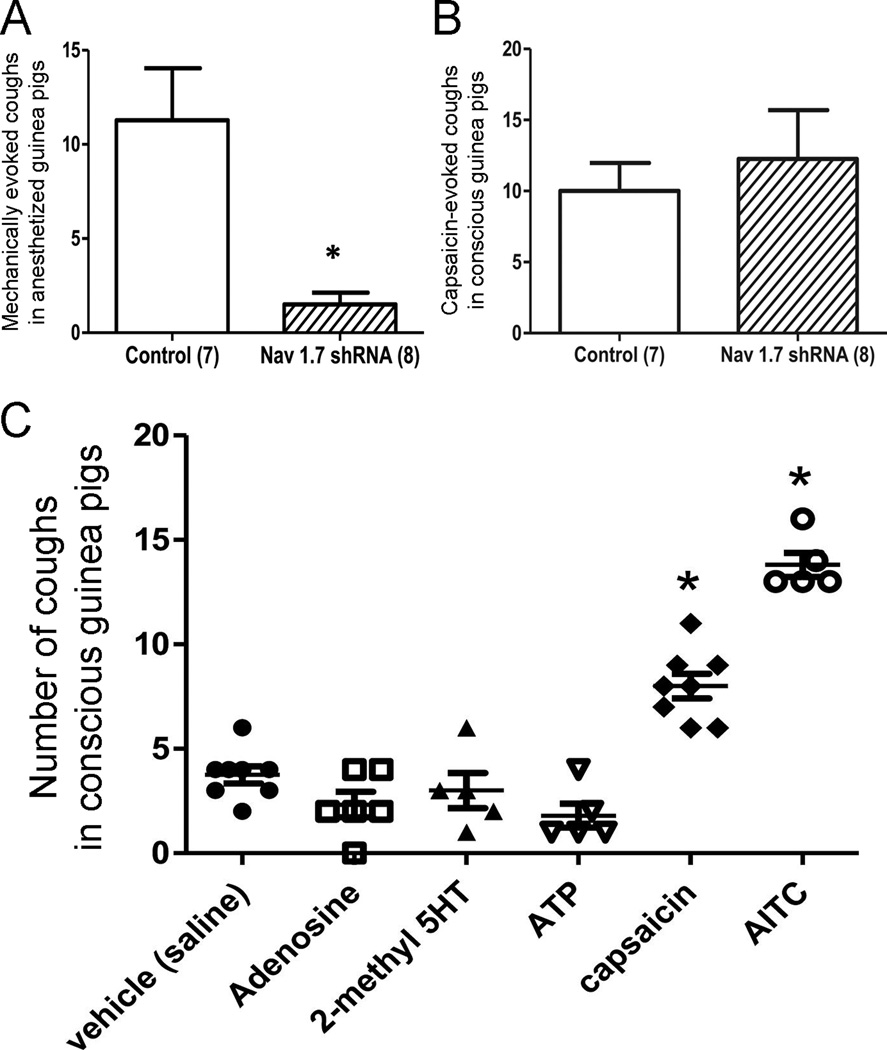

Figure 3.

Distinct afferent subtypes mediate cough. A and B, the effect of in vivo knockdown of NaV1.7 in nodose neurons on (A) the cough evoked by punctate mechanical stimulation of the trachea in anesthetized guinea pigs, and (B) the cough evoked by inhalation of nebulized capsaicin (10µM) in conscious animals. The number of animals in each group is denoted in parentheses. C, Coughs evoked by various C fiber stimuli in conscious guinea pigs: saline (n=8), adenosine (10mM, n=6), 2-methyl-5HT (5mM, n=5), ATP (10mM, n=5), capsaicin (3µM, n=8) and AITC (10mM, n=5). Adapted from [30].

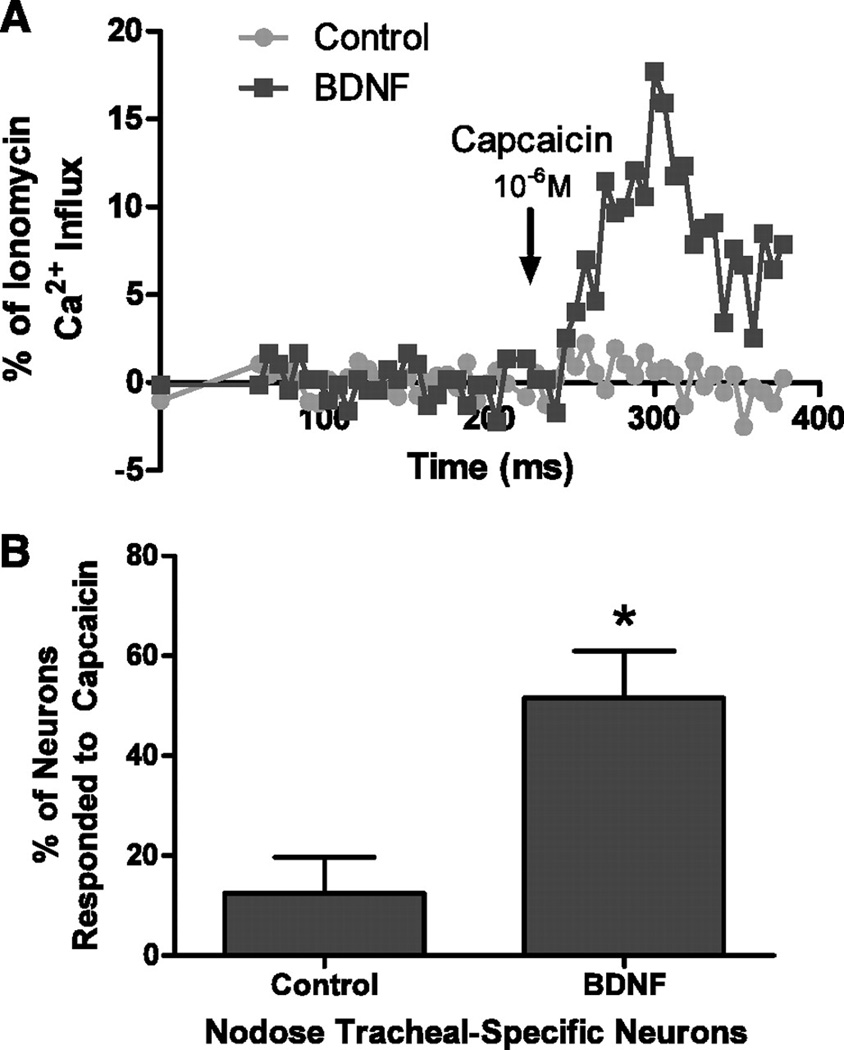

Figure 4.

Capsaicin-induced calcium responses in tracheal-specific nodose neurons in control and BDNF-treated guinea pigs. A: representative example of the Ca2+ responses, as measured by fura-2, in a tracheal-specific nodose neuron isolated from guinea pigs 2 wk following treatment with Matrigel alone (control, gray line) or treated with Matrigel containing 200 ng/ml BDNF (black line). Capsaicin (1µM) was applied for 60 s (black arrow). B: percentage of tracheal-specific nodose neurons from control animals (n = 4 ganglia) and BDNF-treated animals (n = 4 ganglia) that responded to capsaicin. Taken from [28].

Highlights.

Distinct airway afferent subtypes have distinct activation profiles

Cough is evoked by stimulation of extrapulmonary Aδ fibers in anesthetized animals

Cough is evoked by stimulation of jugular C fibers in conscious animals

Central interactions of multiple afferent pathways modulate the cough reflex

Inflammatory mediators alter afferent excitability and protein expression

Acknowledgements

Work in our laboratory is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI, Bethesda, USA): R01HL119802.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Nothing Declared

References

- 1.Canning BJ, Mazzone SB, Meeker SN, Mori N, Reynolds SM, Undem BJ. Identification of the tracheal and laryngeal afferent neurones mediating cough in anaesthetized guinea-pigs. J Physiol. 2004;557:543–558. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.057885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzone SB, Reynolds SM, Mori N, Kollarik M, Farmer DG, Myers AC, Canning BJ. Selective expression of a sodium pump isozyme by cough receptors and evidence for its essential role in regulating cough. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13662–13671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4354-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canning BJ, Farmer DG, Mori N. Mechanistic studies of acid-evoked coughing in anesthetized guinea pigs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R454–R463. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00862.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plevkova J, Kollarik M, Brozmanova M, Revallo M, Varechova S, Tatar M. Modulation of experimentally-induced cough by stimulation of nasal mucosa in cats and guinea pigs. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;142:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou YL, Scarupa MD, Mori N, Canning BJ. Differential effects of airway afferent nerve subtypes on cough and respiration in anesthetized guinea pigs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1572–R1584. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90382.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsberg K, Karlsson JA, Theodorsson E, Lundberg JM, Persson CG. Cough and bronchoconstriction mediated by capsaicinsensitive sensory neurons in the guinea-pig. Pulm Pharmacol. 1988;1:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(88)90008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laude EA, Higgins KS, Morice AH. A comparative study of the effects of citric acid, capsaicin and resiniferatoxin on the cough challenge in guinea-pig and man. Pulm Pharmacol. 1993;6:171–175. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1993.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birrell MA, Belvisi MG, Grace M, Sadofsky L, Faruqi S, Hele DJ, Maher SA, Freund-Michel V, Morice AH. TRPA1 Agonists Evoke Coughing in Guinea-pig and Human Volunteers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1042–1047. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0665OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andre E, Gatti R, Trevisani M, Preti D, Baraldi PG, Patacchini R, Geppetti P. Transient receptor potential ankyrin receptor 1 is a novel target for pro-tussive agents. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:1621–1628. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatasamy R, McKenzie A, Page CP, Walker MJ, Spina D. Use of within-group designs to test anti-tussive drugs in conscious guinea-pigs. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2010;61:157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanezaki M, Ebihara S, Gui P, Ebihara T, Kohzuki M. Effect of cigarette smoking on cough reflex induced by TRPV1 and TRPA1 stimulations. Respir Med. 2012;106:406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.12.007. This study determined the sensitivity of cough (2 coughs, or 5 coughs) and urge-to-cough sensations following the inhalation of capsaicin (TRPV1 agonist) and cinnamaldehyde (TRPA1) agonist. Smokers were shown to require higher amounts of capsaicin to evoke cough compared to never-smokers, although urge-to-cough sensitivity was unaffected. No differences were observed for cinnamaldehyde-induced cough responses.

- 12.Sekizawa K, Ebihara T, Sasaki H. Role of substance P in cough during bronchoconstriction in awake guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:815–821. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.3.7533603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolser DC, DeGennaro FC, O'Reilly S, Hey JA, Chapman RW. Pharmacological studies of allergic cough in the guinea pig. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;277:159–164. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00076-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohkura N, Fujimura M, Hara J, Ohsawa M, Kamei J, Nakao S. Bronchoconstriction-triggered cough in conscious guinea pigs. Exp Lung Res. 2009;35:296–306. doi: 10.1080/01902140802668831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr MJ, Undem BJ. Bronchopulmonary afferent nerves. Respirology. 2003;8:291–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Undem BJ, Taylor-Clark T. Mechanisms underlying the neuronal-based symptoms of allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1521–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.027. An up-to-date review of the multiple mechanisms by which mast cell mediators cause activation, increased excitability and phenotypic changes in afferent and autonomic nerves.

- 17.Baker CV, Bronner-Fraser M. Establishing neuronal identity in vertebrate neurogenic placodes. Development. 2000;127:3045–3056. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Undem BJ, Chuaychoo B, Lee MG, Weinreich D, Myers AC, Kollarik M. Subtypes of vagal afferent C-fibres in guinea-pig lungs. J Physiol. 2004;556:905–917. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.060079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nassenstein C, Taylor-Clark TE, Myers AC, Ru F, Nandigama R, Bettner W, Undem BJ. Phenotypic distinctions between neural crest and placodal derived vagal C-fibres in mouse lungs. J Physiol. 2010;588:4769–4783. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.195339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC. Pulmonary reflexes: neural mechanisms of pulmonary defense. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:69–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canning BJ. Reflex regulation of airway smooth muscle tone. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:971–985. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00313.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherrington C. The integrative action of the nervous system. New Haven: 1906. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kollarik M, Carr MJ, Ru F, Ring CJ, Hart VJ, Murdock P, Myers AC, Muroi Y, Undem BJ. Transgene expression and effective gene silencing in vagal afferent neurons in vivo using recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. J Physiol. 2010;588:4303–4315. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricco MM, Kummer W, Biglari B, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Interganglionic segregation of distinct vagal afferent fibre phenotypes in guinea-pig airways. J Physiol. 1996;496 ( Pt 2):521–530. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riccio MM, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Immunomodulation of afferent neurons in guinea-pig isolated airway. J Physiol. 1996;491 ( Pt 2):499–509. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kollarik M, Undem BJ. Mechanisms of acid-induced activation of airway afferent nerve fibres in guinea-pig. J Physiol. 2002;543:591–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAlexander MA, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Adaptation of guinea-pig vagal airway afferent neurones to mechanical stimulation. J Physiol. 1999;521 Pt 1:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lieu TM, Myers AC, Meeker S, Undem BJ. TRPV1 induction in airway vagal low-threshold mechanosensory neurons by allergen challenge and neurotrophic factors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L941–L948. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00366.2011. This study demonstrates de novo expression of TRPV1 in nodose Ad fiber neurons innervating the trachea following allergen challenge. Identical phenotypic switching was observed with treatment with BDNF and GDNF, but not NGF, indicating the importance of specific neurotrophin receptors on nodose neurons. Such plasticity has important repercussions for the presentation of cough in disease states.

- 29.Tsubone H, Sant'Ambrogio G, Anderson JW, Orani GP. Laryngeal afferent activity and reflexes in the guinea pig. Respir Physiol. 1991;86:215–231. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(91)90082-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muroi Y, Ru F, Chou YL, Carr MJ, Undem BJ, Canning BJ. Selective inhibition of vagal afferent nerve pathways regulating cough using Nav 1.7 shRNA silencing in guinea pig nodose ganglia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R1017–R1023. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00028.2013. This study shows that the knockdown of NaV 1.7 in nodose neurons eliminates cough elicited from the guinea pig trachea under anesthesia. Furthermore, this study shows nodose neurons are not required for cough elicited by capsaicin in awake animals and that stimuli that selectively activate nodose C fibers fail to evoke cough in awake animals. Thus this important study clarifies the distinctive roles of nodose Ad fibers and jugular C-fibers in cough.

- 31.Muroi Y, Ru F, Kollarik M, Canning BJ, Hughes SA, Walsh S, Sigg M, Carr MJ, Undem BJ. Selective Silencing of NaV1.7 Decreases Excitability and Conduction in Vagal Sensory Neurons. J Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.215384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dusenkova S, Ru F, Surdenikova L, Nassenstein C, Hatok J, Dusenka R, Banovcin P, Jr, Kliment J, Tatar M, Kollarik M. The expression profile of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) subunits ASIC1a, ASIC1b, ASIC2a, ASIC2b, and ASIC3 in the esophageal vagal afferent nerve subtypes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G922–G930. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00129.2014. This is the first study to identify using single cell RT-PCR the various ASIC subunits expressed by vagal neurons. Although the focus is on esophageal afferents, such data is suggestive of receptors responsible for acid-induced activation of cough afferents.

- 33.Kwan KY, Allchorne AJ, Vollrath MA, Christensen AP, Zhang DS, Woolf CJ, Corey DP. TRPA1 Contributes to Cold, Mechanical, and Chemical Nociception but Is Not Essential for Hair-Cell Transduction. Neuron. 2006;50:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carr MJ, Gover TD, Weinreich D, Undem BJ. Inhibition of mechanical activation of guinea-pig airway afferent neurons by amiloride analogues. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:1255–1262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor-Clark T, Undem BJ. Transduction mechanisms in airway sensory nerves. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:950–959. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00222.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coste B, Mathur J, Schmidt M, Earley TJ, Ranade S, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzone SB, McGovern AE. Immunohistochemical characterization of nodose cough receptor neurons projecting to the trachea of guinea pigs. Cough. 2008;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleridge JC, Coleridge HM. Afferent vagal C fibre innervation of the lungs and airways and its functional significance. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;99:1–110. doi: 10.1007/BFb0027715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee LY. Respiratory sensations evoked by activation of bronchopulmonary C-fibers. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunter DD, Undem BJ. Identification and substance P content of vagal afferent neurons innervating the epithelium of the guinea pig trachea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1943–1948. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.6.9808078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC. Impulse activity in afferent vagal C-fibres with endings in the intrapulmonary airways of dogs. Respir Physiol. 1977;29:125–142. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(77)90086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho CY, Gu Q, Lin YS, Lee LY. Sensitivity of vagal afferent endings to chemical irritants in the rat lung. Respir Physiol. 2001;127:113–124. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kollarik M, Dinh QT, Fischer A, Undem BJ. Capsaicin-sensitive and -insensitive vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres in the mouse. J Physiol. 2003;551:869–879. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee LY, Lundberg JM. Capsazepine abolishes pulmonary chemoreflexes induced by capsaicin in anesthetized rats. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1848–1855. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.5.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Undem BJ, Kollarik M. Characterization of the vanilloid receptor 1 antagonist iodo-resiniferatoxin on the afferent and efferent function of vagal sensory C-fibers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:716–722. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.039727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kollarik M, Undem BJ. Activation of bronchopulmonary vagal afferent nerves with bradykinin, acid and vanilloid receptor agonists in wild-type and TRPV1−/− mice. J Physiol. 2004;555:115–123. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.054890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Green JF, Schmidt ND, Schultz HD, Roberts AM, Coleridge HM, Coleridge JC. Pulmonary C-fibers evoke both apnea and tachypnea of pulmonary chemoreflex. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1984;57:562–567. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.2.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tatar M, Webber SE, Widdicombe JG. Lung C-fibre receptor activation and defensive reflexes in anaesthetized cats. J Physiol. 1988;402:411–420. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mazzone SB, Mori N, Canning BJ. Synergistic interactions between airway afferent nerve subtypes regulating the cough reflex in guinea-pigs. J Physiol. 2005;569:559–573. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.093153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lalloo UG, Fox AJ, Belvisi MG, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Capsazepine inhibits cough induced by capsaicin and citric acid but not by hypertonic saline in guinea pigs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1995;79:1082–1087. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.4.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trevisani M, Milan A, Gatti R, Zanasi A, Harrison S, Fontana G, Morice AH, Geppetti P. Antitussive activity of iodo-resiniferatoxin in guinea pigs. Thorax. 2004;59:769–772. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.012930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka M, Maruyama K. Mechanisms of capsaicin- and citric-acid-induced cough reflexes in guinea pigs. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;99:77–82. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj05014x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lou YP, Karlsson JA, Franco-Cereceda A, Lundberg JM. Selectivity of ruthenium red in inhibiting bronchoconstriction and CGRP release induced by afferent C-fibre activation in the guinea-pig lung. Acta Physiol Scand. 1991;142:191–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leung SY, Niimi A, Williams AS, Nath P, Blanc FX, Dinh QT, Chung KF. Inhibition of citric acid- and capsaicin-induced cough by novel TRPV-1 antagonist, V112220, in guinea-pig. Cough. 2007;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gu Q, Lee LY. Characterization of acid signaling in rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L58–L65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00517.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jordt SE, Bautista DM, Chuang HH, McKemy DD, Zygmunt PM, Hogestatt ED, Meng ID, Julius D. Mustard oils and cannabinoids excite sensory nerve fibres through the TRP channel ANKTM1. Nature. 2004;427:260–265. doi: 10.1038/nature02282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bandell M, Story GM, Hwang SW, Viswanath V, Eid SR, Petrus MJ, Earley TJ, Patapoutian A. Noxious cold ion channel TRPA1 is activated by pungent compounds and bradykinin. Neuron. 2004;41:849–857. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andersson DA, Gentry C, Moss S, Bevan S. Transient receptor potential A1 is a sensory receptor for multiple products of oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2485–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor-Clark TE, Undem BJ, Macglashan DW, Jr, Ghatta S, Carr MJ, McAlexander MA. Prostaglandin-Induced Activation of Nociceptive Neurons via Direct Interaction with Transient Receptor Potential A1 (TRPA1) Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:274–281. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taylor-Clark TE, McAlexander MA, Nassenstein C, Sheardown SA, Wilson S, Thornton J, Carr MJ, Undem BJ. Relative contributions of TRPA1 and TRPV1 channels in the activation of vagal bronchopulmonary C-fibres by the endogenous autacoid 4-oxononenal. J Physiol. 2008;586:3447–3459. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andre E, Campi B, Materazzi S, Trevisani M, Amadesi S, Massi D, Creminon C, Vaksman N, Nassini R, Civelli M, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced neurogenic inflammation is mediated by alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes and the TRPA1 receptor in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2574–2582. doi: 10.1172/JCI34886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor-Clark TE, Ghatta S, Bettner W, Undem BJ. Nitrooleic acid, an endogenous product of nitrative stress, activates nociceptive sensory nerves via the direct activation of TRPA1. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:820–829. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.054445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor-Clark TE, Undem BJ. Ozone activates airway nerves via the selective stimulation of TRPA1 ion channels. J Physiol. 2010;588:423–433. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nassenstein C, Kwong K, Taylor-Clark T, Kollarik M, Macglashan DM, Braun A, Undem BJ. Expression and function of the ion channel TRPA1 in vagal afferent nerves innervating mouse lungs. J Physiol. 2008;586:1595–1604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.148379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hinman A, Chuang HH, Bautista DM, Julius D. TRP channel activation by reversible covalent modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19564–19568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609598103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Macpherson LJ, Dubin AE, Evans MJ, Marr F, Schultz PG, Cravatt BF, Patapoutian A. Noxious compounds activate TRPA1 ion channels through covalent modification of cysteines. Nature. 2007;445:541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature05544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Brozmanova M, Mazurova L, Ru F, Tatar M, Kollarik M. Comparison of TRPA1-versus TRPV1-mediated cough in guinea pigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;689:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.05.048. This is the first study to definitively confirm that airway jugular C fibers are activated by TRPA1 agonsts but trachea nodose Ad fibers are insensitive to TRPA1 agonists. Furthermore this paper shows that while AITC-evoked cough was mediated entirely by TRPA1 receptors, cinnamaldehyde-evoked cough was mediated by both TRPA1 and TRPV1 receptors.

- 69.Chuang HH, Prescott ED, Kong H, Shields S, Jordt SE, Basbaum AI, Chao MV, Julius D. Bradykinin and nerve growth factor release the capsaicin receptor from PtdIns(4,5)P2-mediated inhibition. Nature. 2001;411:957–962. doi: 10.1038/35082088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shin J, Cho H, Hwang SW, Jung J, Shin CY, Lee SY, Kim SH, Lee MG, Choi YH, Kim J, et al. Bradykinin-12-lipoxygenase-VR1 signaling pathway for inflammatory hyperalgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10150–10155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152002699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bautista DM, Jordt SE, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, Read AJ, Poblete J, Yamoah EN, Basbaum AI, Julius D. TRPA1 Mediates the Inflammatory Actions of Environmental Irritants and Proalgesic Agents. Cell. 2006;124:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kajekar R, Proud D, Myers AC, Meeker SN, Undem BJ. Characterization of vagal afferent subtypes stimulated by bradykinin in guinea pig trachea. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:682–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carr MJ, Kollarik M, Meeker SN, Undem BJ. A role for TRPV1 in bradykinin-induced excitation of vagal airway afferent nerve terminals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1275–1279. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Grace M, Birrell MA, Dubuis E, Maher SA, Belvisi MG. Transient receptor potential channels mediate the tussive response to prostaglandin E2 and bradykinin. Thorax. 2012;67:891–900. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201443. This study shows dose-dependent TRP channel inhibition of cough evoked by capsaicin (TRPV1) and acrolein (TRPA1). Furthermore, bradykinin- and PGE2-evoked cough is reduced by selective TRP channel inhibition, suggesting a role of these channels in cough afferent activation by inflammatory GPCR.

- 75. Smith JA, Hilton EC, Saulsberry L, Canning BJ. Antitussive effects of memantine in guinea pigs. Chest. 2012;141:996–1002. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0554. This paper demonstrates that cough evoked in concious guinea pigs by either citric acid or bradykinin is inhibited by memantine in a dose-dependent manner. Significant antitussive activity was observed without sedation. Pharmacological studies suggest that antitussive effect of memantine is via inhibition of NMDA receptors, rather than via inhibition of serotonin or acetylcholine receptors.

- 76.Chuaychoo B, Lee MG, Kollarik M, Undem BJ. Effect of 5-hydroxytryptamine on vagal C-fiber subtypes in guinea pig lungs. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2005;18:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chuaychoo B, Lee MG, Kollarik M, Pullmann R, Jr, Undem BJ. Evidence for both adenosine A1 and A2A receptors activating single vagal sensory C-fibres in guinea pig lungs. J Physiol. 2006;575:481–490. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.109371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Duchen MR. Effects of metabolic inhibition on the membrane properties of isolated mouse primary sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1990;424:387–409. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fox AJ, Barnes PJ, Venkatesan P, Belvisi MG. Activation of large conductance potassium channels inhibits the afferent and efferent function of airway sensory nerves in the guinea pig. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:513–519. doi: 10.1172/JCI119187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Dubuis E, Wortley MA, Grace MS, Maher SA, Adcock JJ, Birrell MA, Belvisi MG. Theophylline inhibits the cough reflex through a novel mechanism of action. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1588–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.017. This extensive paper shows that cough evoked in concious guinea pigs by either citric acid or capsaicin is inhibited by theophylline in a dose-dependent manner. Theophylline is shown to reduce airway afferent activity evoked by a series of nociceptive stimuli. Patch clamp recordings suggest theophylline increases calcium-activated potassium currents in nociceptive jugular neurons, resulting in hyperpolarization and decreased excitability.

- 81.Greene R, Fowler J, MacGlashan D, Jr, Weinreich D. IgE-challenged human lung mast cells excite vagal sensory neurons in vitro. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2249–2253. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.5.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Undem BJ, Myers AC, Weinreich D. Antigen-induced modulation of autonomic and sensory neurons in vitro. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1991;94:319–324. doi: 10.1159/000235394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fox AJ, Lalloo UG, Belvisi MG, Bernareggi M, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. Bradykinin-evoked sensitization of airway sensory nerves: a mechanism for ACE-inhibitor cough. Nat Med. 1996;2:814–817. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jafri MS, Moore KA, Taylor GE, Weinreich D. Histamine H1 receptor activation blocks two classes of potassium current, IK(rest) and IAHP, to excite ferret vagal afferents. J Physiol. 1997;503 ( Pt 3):533–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.533bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee LY, Morton RF. Histamine enhances vagal pulmonary C-fiber responses to capsaicin and lung inflation. Respir Physiol. 1993;93:83–96. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(93)90070-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cordoba-Rodriguez R, Moore KA, Kao JP, Weinreich D. Calcium regulation of a slow post-spike hyperpolarization in vagal afferent neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7650–7657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oh EJ, Weinreich D. Bradykinin decreases K(+) and increases Cl(−) conductances in vagal afferent neurones of the guinea pig. J Physiol. 2004;558:513–526. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.066381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kwong K, Lee LY. Prostaglandin E2 potentiates a TTX-resistant sodium current in rat capsaicin-sensitive vagal pulmonary sensory neurones. J Physiol. 2005;564:437–450. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gu Q, Lee LY. Hypersensitivity of pulmonary chemosensitive neurons induced by activation of protease-activated receptor-2 in rats. J Physiol. 2006;574:867–876. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang G, Lin RL, Wiggers ME, Lee LY. Sensitizing effects of chronic exposure and acute inhalation of ovalbumin aerosol on pulmonary C fibers in rats. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:128–138. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01367.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Choudry NB, Fuller RW, Pride NB. Sensitivity of the human cough reflex: effect of inflammatory mediators prostaglandin E2, bradykinin, and histamine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:137–141. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stone R, Barnes PJ, Fuller RW. Contrasting effects of prostaglandins E2 and F2 alpha on sensitivity of the human cough reflex. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1992;73:649–653. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Takahama K, Araki T, Fuchikami J, Kohjimoto Y, Miyata T. Studies on the magnitude and the mechanism of cough potentiation by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in guinea-pigs: involvement of bradykinin in the potentiation. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1996;48:1027–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1996.tb05895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kamei J, Takahashi Y. Involvement of ionotropic purinergic receptors in the histamine-induced enhancement of the cough reflex sensitivity in guinea pigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;547:160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Farrell MJ, Cole LJ, Chiapoco D, Egan GF, Mazzone SB. Neural correlates coding stimulus level and perception of capsaicin-evoked urge-to-cough in humans. Neuroimage. 2012;61:1324–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.030. This paper uses functional magnetic resonance imaging of the human brain to determine areas of the CNS that are active during capsaicin inhalation challenges. This study demonstrates dose-dependent activity evoked by capsaicin in insula and mid cingulate cortex which correlated with urge-to-cough ratings, as well as significant activity in respiratory-related regions of the brainstem (dorsal pons and lateral medulla).

- 96.Canning BJ. Central regulation of the cough reflex: therapeutic implications. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2009;22:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. O'Connor R, Segers LS, Morris KF, Nuding SC, Pitts T, Bolser DC, Davenport PW, Lindsey BG. A joint computational respiratory neural network-biomechanical model for breathing and airway defensive behaviors. Front Physiol. 2012;3:264. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00264. This paper establishes a model of the CNS networks that control the co-ordination of breathing and cough, with special emphasis on the contribution of peripheral afferents from the lungs, airways and respiratory muscles derived from data collected by previously published human studies.

- 98.Bolser DC, Gestreau C, Morris KF, Davenport PW, Pitts TE. Central neural circuits for coordination of swallowing, breathing, and coughing: predictions from computational modeling and simulation. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2013;46:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Narula M, McGovern AE, Yang SK, Farrell MJ, Mazzone SB. Afferent neural pathways mediating cough in animals and humans. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:S712–S719. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.03.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.El-Hashim AZ, Amine SA. The role of substance P and bradykinin in the cough reflex and bronchoconstriction in guinea-pigs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;513:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Canning BJ, Mori N. An essential component to brainstem cough gating identified in anesthetized guinea pigs. Faseb J. 2010;24:3916–3926. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-151068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yu S, Undem BJ, Kollarik M. Vagal afferent nerves with nociceptive properties in guinea-pig oesophagus. J Physiol. 2005;563:831–842. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kollarik M, Brozmanova M. Cough and gastroesophageal reflux: Insights from animal models. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hanacek J, Davies A, Widdicombe JG. Influence of lung stretch receptors on the cough reflex in rabbits. Respiration. 1984;45:161–168. doi: 10.1159/000194614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nishino T, Sugimori K, Hiraga K, Hond Y. Influence of CPAP on reflex responses to tracheal irritation in anesthetized humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1989;67:954–958. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.3.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Brozmanova M, Calkovsky V, Plevkova J, Bartos V, Plank L, Tatar M. Early and late allergic phase related cough response in sensitized guinea pigs with experimental allergic rhinitis. Physiol Res. 2006;55:577–584. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Plevkova J, Varechova S, Brozmanova M, Tatar M. Testing of cough reflex sensitivity in children suffering from allergic rhinitis and common cold. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57 Suppl 4:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Brozmanova M, Plevkova J, Tatar M, Kollarik M. Cough reflex sensitivity is increased in the guinea pig model of allergic rhinitis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59 Suppl 6:153–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Taylor-Clark TE, Kollarik M, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Undem BJ. Nasal sensory nerve populations responding to histamine and capsaicin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:1282–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sekizawa SI, Tsubone H. Nasal receptors responding to noxious chemical irritants. Respir Physiol. 1994;96:37–48. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Damann N, Rothermel M, Klupp BG, Mettenleiter TC, Hatt H, Wetzel CH. Chemosensory properties of murine nasal and cutaneous trigeminal neurons identified by viral tracing. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Plevkova J, Brozmanova M, Pecova R, Tatar M. Effects of intranasal histamine on the cough reflex in subjects with allergic rhinitis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;56 Suppl 4:185–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Plevkova J, Antosiewicz J, Varechova S, Poliacek I, Jakus J, Tatar M, Pokorski M. Convergence of nasal and tracheal neural pathways in modulating the cough response in guinea pigs. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60:89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Biringerova Z, Gavliakova S, Brozmanova M, Tatar M, Hanuskova E, Poliacek I, Plevkova J. The effects of nasal irritant induced responses on breathing and cough in anaesthetized and conscious animal models. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;189:588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2013.08.003. This study shows that nasal challenge with TRPA1 agonist AITC reduces cough responses to citric acid (in both anesthetized and awake guinea pigs). This effect was abolished by a selective TRPA1 inhibitor. Nasal AITC caused bradypnea as expected. It is known that afferent expression of TRPA1 largely co-incides with TRPV1, but capsaicin (TRPV1 agonist) delivered to the nose augments cough reflexes. This paper indicates unexpected complexity in nasal afferent-mediated modulation of cough.

- 115.Plevkova J, Poliacek I, Antosiewicz J, Adamkov M, Jakus J, Svirlochova K, Tatar M. Intranasal TRPV1 agonist capsaicin challenge and its effect on c-fos expression in the guinea pig brainstem. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2010;173:11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Peier AM, Moqrich A, Hergarden AC, Reeve AJ, Andersson DA, Story GM, Earley TJ, Dragoni I, McIntyre P, Bevan S, et al. A TRP channel that senses cold stimuli and menthol. Cell. 2002;108:705–715. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Plevkova J, Kollarik M, Poliacek I, Brozmanova M, Surdenikova L, Tatar M, Mori N, Canning BJ. The role of trigeminal nasal TRPM8-expressing afferent neurons in the antitussive effects of menthol. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;115:268–274. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01144.2012. This paper investigates the antitussive effect of menthol (TRPM8 agonist) in cough evoked by citric acid in both consious and anesthetized guinea pigs. Cough sensitivity was reduced by oral menthol, nasal menthol and nasal cold air but unaffected by menthol instilled into the trachea. Single cell RT-PCR of nasal trigeminal neurons suggest approximately 25% express TRPM8 but not TRPV1, suggesting a plausible afferent subtype responsible for the antitussive effect of menthol.

- 118. Buday T, Brozmanova M, Biringerova Z, Gavliakova S, Poliacek I, Calkovsky V, Shetthalli MV, Plevkova J. Modulation of cough response by sensory inputs from the nose - role of trigeminal TRPA1 versus TRPM8 channels. Cough. 2012;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-8-11. This paper studied the effect of nasal challenge of TRPA1 and TRPM8 agonists on cough evoked by capsaicin inhalation in healthy human subjects. Despite causing significant negative sensations, nasal TRPA1 agonists failed to alter capsaicin-evoked cough. Nasal TRPM8 agonists signifcantly reduced capsaicin-evoked cough.

- 119.Bonini S, Lambiase A, Angelucci F, Magrini L, Manni L, Aloe L. Circulating nerve growth factor levels are increased in humans with allergic diseases and asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10955–10960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fischer A, McGregor GP, Saria A, Philippin B, Kummer W. Induction of tachykinin gene and peptide expression in guinea pig nodose primary afferent neurons by allergic airway inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2284–2291. doi: 10.1172/JCI119039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bonini S, Lambiase A, Levi-Schaffer F, Aloe L. Nerve growth factor: an important molecule in allergic inflammation and tissue remodelling. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;118:159–162. doi: 10.1159/000024055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Myers AC, Kajekar R, Undem BJ. Allergic inflammation-induced neuropeptide production in rapidly adapting afferent nerves in guinea pig airways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282:L775–L781. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00353.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Carr MJ, Hunter DD, Jacoby DB, Undem BJ. Expression of tachykinins in nonnociceptive vagal afferent neurons during respiratory viral infection in guinea pigs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1071–1075. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.8.2108065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hunter DD, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Nerve growth factor-induced phenotypic switch in guinea pig airway sensory neurons. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1985–1990. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9908051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang G, Lin RL, Wiggers M, Snow DM, Lee LY. Altered expression of TRPV1 and sensitivity to capsaicin in pulmonary myelinated afferents following chronic airway inflammation in the rat. J Physiol. 2008;586:5771–5786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.161042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zweifel LS, Kuruvilla R, Ginty DD. Functions and mechanisms of retrograde neurotrophin signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:615–625. doi: 10.1038/nrn1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lieu T, Kollarik M, Myers AC, Undem BJ. Neurotrophin and GDNF family ligand receptor expression in vagal sensory nerve subtypes innervating the adult guinea pig respiratory tract. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L790–L798. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00449.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]