Abstract

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a common, very painful, and often long-lasting complication of herpes zoster which is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated. It mainly affects the elderly, many of whom are already treated for comorbidities with a variety of systemic medications and are thus at high risk of drug–drug interactions. An efficacious and safe treatment with a low interaction potential is therefore of high importance. This review focuses on the safety and tolerability of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster, a topical analgesic indicated for the treatment of PHN. The available literature (up to June 2014) was searched for publications containing safety data regarding the use of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in PHN treatment; unpublished clinical safety data were also included in this review. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster demonstrated good short- and long-term tolerability with low systemic uptake (3 ± 2%) and minimal risk for systemic adverse drug reactions (ADRs). ADRs related to topical lidocaine treatment were mainly application site reactions of mild to moderate intensity. The treatment discontinuation rate was generally below 5% of patients. In one trial, the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster was better tolerated than systemic treatment with pregabalin. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster provides a safe alternative to systemic medications for PHN treatment, including long-term pain treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s40122-015-0034-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 5% Lidocaine medicated plaster, Clinical safety, Postherpetic neuralgia, Tolerability, Topical analgesics

Introduction

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is the most common complication of herpes zoster [1]. Transition from acute herpes zoster to PHN occurs when pain persists 3 months or more; definitions, however, vary from as short as 1 month to as long as 6 months after lesion crusting. PHN pain may be spontaneous or stimulus evoked, constant or intermittent, and with qualities such as burning, throbbing, aching, shooting, or stabbing [1, 2]. Allodynia is common and often considered the most distressing and debilitating component of the disease [3]. PHN has a substantial detrimental effect on all aspects of patients’ quality of life [4, 5]. The condition remains underdiagnosed and often undertreated, particularly in primary care [6]. Incidence of PHN markedly increases with age [7–10].

The topical analgesic 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (Versatis®, Grünenthal GmbH, Aachen, Germany) is recommended for localized peripheral neuropathic pain [11–13] and first line especially in frail and elderly patients when there are concerns regarding side effects or safety of other treatments [13]. It is registered in the USA (as Lidoderm®, Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA, USA) and in many European, Latin American, and Middle Eastern countries. The plaster is approved in approximately 50 countries worldwide for the symptomatic relief of neuropathic pain associated with previous herpes zoster infection and additionally in nine of these countries for localized neuropathic pain treatment. Since the first marketing authorization in 1999 until June 2014, it is estimated that the lidocaine plaster has been prescribed to approximately 20 million patients [14].

The analgesic efficacy of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in PHN treatment was demonstrated in several randomized clinical studies [15–19]. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster is the only PHN treatment with available safety and efficacy clinical data on long-term treatment up to 4 years [20, 21]. Moreover, effectiveness, tolerability, and patient satisfaction were documented for up to 7 years of daily plaster use [22]. A recent publication comprehensively reviews the efficacy of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in pain management [23]. No analysis of pooled data on adverse drug reactions (ADRs), discontinuation data, comparison with systemic medication, and safety in certain higher-risk patient populations has been published so far. This review focuses on this clinical safety and tolerability profile of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster.

Methods

A PubMed literature search was conducted for the time period from 1960 to last update on June 26, 2014 to identify studies reporting the occurrence of adverse events (AEs)/ADRs and other safety issues pertaining to the use of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in PHN treatment. Using the keyword combinations “lidocaine (lignocaine) and pain and postherpetic neuralgia and topical, not gel, not lotion, not cream, not spray”, “lidocaine (lignocaine) and pain and postherpetic neuralgia and plaster”, and “lidocaine (lignocaine) and pain and postherpetic neuralgia and patch” the search retrieved 160 publications (including duplicates). Screening of the abstracts identified 18 original publications reporting on safety. However, in eleven of these publications, the study populations also included patients with pain diagnoses other than PHN, and safety was not documented separately for different diagnoses. To stay within the PHN indication, these publications outside of the labeled indication were excluded. As it was intended to describe the tolerability and safety of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster, it was decided to focus on the occurrence of ADRs and to exclude publications only reporting AEs. Overall, 6 publications remained [16, 18–21, 24]. Additionally, articles regarding pharmacological aspects, previous pharmacokinetic and safety reviews, PHN/5% lidocaine medicated plaster reviews, case reports relating to safety issues, the Summary of Product Characteristics of the lidocaine medicated plaster [25], and unpublished clinical safety data from Grünenthal GmbH were perused for this review.

This review is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Pharmacological Profile

Pharmacodynamic Properties

The plaster consists of a 10 cm × 14 cm hydrogel adhesive containing 700 mg of lidocaine (5% w/w) [25]. A daily application of up to three plasters (depending on the size of the painful skin area) to undamaged skin for a maximum of 12 h with plaster-free intervals of at least 12 h is recommended. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster is placed directly on the affected area of pain [26].

The hydrogel plaster itself provides an immediate cooling and soothing perception, while giving physical protection to the hypersensitive area of the skin [15, 17]. The active compound lidocaine is thought to act as a local analgesic by selective but only partial inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels of damaged or dysfunctional unmyelinated C fibers and small myelinated Aδ fibers [27]. This pharmacological action is thought to stabilize the neuronal membrane potential on Aδ and C fibers resulting in a reduction of ectopic discharges [17, 27–29]. Besides reductions in pain intensity, the plaster was also shown to reduce the painful surface area [30]. A positive effect on allodynia and hyperalgesia was also observed [31, 32]. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster does not cause local anesthesia [32].

Pharmacokinetic Properties

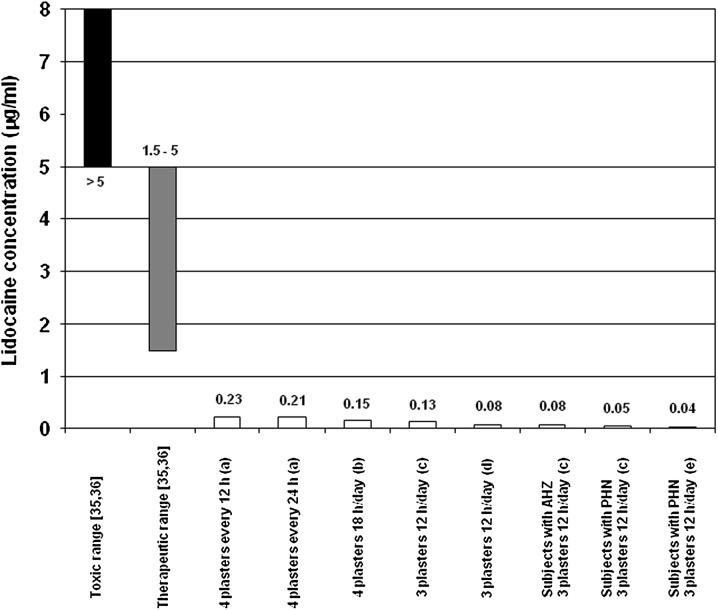

Following plaster application lidocaine is continuously released at the application site; only approximately 3 ± 2% of the applied lidocaine enters systemic circulation [33]. Steady-state plasma concentrations are reached within 4 days with no tendency for lidocaine accumulation [25]. Pharmacokinetic studies and a population kinetics analysis of clinical efficacy studies observed that mean maximum lidocaine plasma concentrations were below 0.3 µg/ml using up to four plasters in healthy volunteers and up to three plasters in patients with acute herpes zoster or PHN (Fig. 1) including extended dosing regimens (four plasters simultaneously, application for 18 h, continuous 72 h application with plaster changes every 24 h [28, 34]). When more than three plasters were applied and an extended application time was used, increases in area under the curve and maximum serum concentration relative to the investigations using three plasters were documented [28, 34]. However, the observed absorption remained low, that is, well below the minimum effective plasma concentrations during therapy of cardiac arrhythmias and well below the toxic range for lidocaine (Fig. 1). Lidocaine plasma concentrations even remained below 0.5 µg/ml after 4 months of treatment with ten 5% lidocaine medicated plasters daily to ease neuropathic pain in one cancer patient [37].

Fig. 1.

Comparison of lidocaine plasma/serum concentrations after topical application of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (open/white bars) in healthy volunteers and patients with AHZ or PHN to plasma concentrations associated with the therapeutic systemic administration (grey bar) and toxic range for cardiac arrhythmias (black bar). Trials with various 5% lidocaine medicated plaster treatment regimes and populations: a 4 plasters administered every 12 h (twice daily) or 24 h for 3 consecutive days to healthy volunteers [28]; b 4 plasters administered for 18 h/day for 3 consecutive days to healthy volunteers [34]; c 3 plasters administered for 12 h/day for 3 consecutive days to healthy volunteers (Grünenthal, data on file); c 3 plasters administered for 12 h for 1 day to patients with AHZ and to patients with PHN (Grünenthal, data on file); d 3 plasters administered for 12 h/day for 5 consecutive days to healthy volunteers (Grünenthal, data on file); e 3 plasters administered for up to 12 h/day for 1 year to patients with PHN (mean maximum serum concentration value; Grünenthal, data on file). AHZ acute herpes zoster, PHN postherpetic neuralgia

Although the absorption of lidocaine from the skin is generally low, the plaster must be used with caution in patients receiving Class I antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g., tocainide, mexiletine) and other local anesthetics, because the risk of additive systemic effects cannot be excluded [25]. No drug interaction studies have been carried out; however, as systemic absorption is only approximately 3%, clinically relevant pharmacokinetic interactions with other medications are unlikely. In addition, no clinically relevant interactions have been observed in clinical studies with the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster [25].

Absorbed lidocaine is rapidly and extensively metabolized in the liver, mainly by N-dealkylation to monoethylglycinexylidide and glycinexylidide, which are less active than the parent compound and present only in low concentrations [25]. Lidocaine and its metabolites are primarily eliminated by the kidneys; less than 10% is excreted unchanged [25]. The elimination half-life of lidocaine after plaster application in healthy volunteers is 7.6 h [25].

Adverse Drug Reactions

In the initial trials, AEs were collected using a pre-specified special symptom checklist to inquire about untoward local anesthetic or dermatological effects and systemic adverse reactions typical for local anesthetics, whereas in the larger phase 3 trials with the majority of patients AEs were collected following the spontaneous reporting concept during scheduled visits. AEs were encoded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) preferred term with respective system organ classes, and frequencies were analyzed descriptively.

For all AEs (i.e., serious and non-serious), the causal relation to the investigational medicinal product (IMP) [38] was evaluated by the investigator, whereas for serious AEs (SAEs) an additional causality assessment was performed by the sponsor. An AE was considered as an ADR, if either the investigator or the sponsor or both considered the AE to be at least possibly related to the administration of the IMP.

In the first double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose trial, a list of pre-specified symptoms were each rated on an intensity scale before start and at end of treatment [39, 40]. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster treatment did not cause any score increases compared to placebo.

Pooled Analysis

In 2007, four clinical efficacy and safety trials were pooled to assess the safety profile of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster. This analysis has so far not been published. Overall, 502 patients (56.4% female) with a mean age of 73.1 ± 8.3 years who had applied at least one 5% lidocaine medicated plaster were included. The majority of patients (82.5%) were over 65 years of age. Mean PHN duration was 3.0 ± 4.2 years. As described above, the first double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-dose trial [39, 40] differed from the remaining three studies [16, 18, 20]. To avoid a bias regarding the spectrum of reported AE terms this trial was excluded from the analysis. Summary information about the included studies is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary information of the clinical postherpetic neuralgia studies included in the integrated safety analysis of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster

| Trial: | Pivotal phase 3 trial [16] in the United States | Pivotal phase 3 trial [18] in Europe | Long-term open-label trial [20] in Europe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | Enriched enrolment, two centers, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over | Enriched enrolment, multicenter | Open-label, multicenter | |

| Open-label, active run-in phase | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase | |||

| Patients exposed to lidocaine plaster, n | 32 | 265 | 36 | 249a |

| Mean ± SD age, years | 77.3 ± 7.1 | 72.6 ± 8.4 | 70.8 ± 9.1 | 72.4 ± 8.6 |

| Female, % | 56 | 57 | 53 | 56 |

| Mean ± SD duration of PHN, years | 7.3b | 3.1 ± 4.8 (n = 257) | 3.6 ± 4.0 | 2.6 ± 3.0 (n = 196) |

| Plasters applied, n | Up to 3 plasters, 12 h daily | Up to 3 plasters, 12 h daily | Up to 3 plasters, 12 h daily | Up to 3 plasters, 12 h daily |

| Treatment duration | Up to 2 weeks | Up to 8 weeks | Up to 2 weeks | Up to 12 months |

| Average exposure to plaster per patient, hc | 139 | 498d | 3043 | |

a152 patients from the pivotal European trial [18] and 97 newly recruited patients

bSD not available

cManual calculation by dividing total duration of exposure to plasters by number of patients exposed to plaster

dFor the entire study phase. PHN Postherpetic neuralgia, SD Standard deviation

Overall, 394 patients were included in this analysis of whom 78 (19.8%) experienced 131 ADRs. None of the ADRs were serious according to the sponsor’s criteria. The most commonly affected system organ classes were “general disorders and administration site conditions” (47 patients/11.9%), followed by skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (23/5.8%), nervous system disorders (9/2.3%), and gastrointestinal disorders (3/0.8%). In the majority of patients with ADRs (65/78; 83%), ADRs were related to the skin with application site erythema and application site pruritus most frequently reported (Table 2).

Table 2.

Integrated safety analysis: adverse drug reactions related to the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster involving the skin

| Study population | 394 (100%) |

| Patients with adverse drug reactions related to the skin | 65 (16.5%) |

| Application site erythema | 15 (3.8%) |

| Application site pruritus | 11 (2.8%) |

| Erythema | 10 (2.5%) |

| Application site pain | 8 (2.0%) |

| Application site irritation | 7 (1.8%) |

| Rash | 7 (1.8%) |

| Application site dermatitis | 6 (1.5%) |

| Application site hypersensitivity | 5 (1.3%) |

| Pruritus | 5 (1.3%) |

| Pain of skin | 2 (0.5%) |

| Application site anesthesia | 1 (0.3%) |

| Application site excoriation | 1 (0.3%) |

| Application site hyperesthesia | 1 (0.3%) |

| Application site inflammation | 1 (0.3%) |

| Application site edema | 1 (0.3%) |

| Application site pustules | 1 (0.3%) |

| Application site vesicles | 1 (0.3%) |

| Dermatitis | 1 (0.3%) |

| Dermatitis allergic | 1 (0.3%) |

| Skin discoloration | 1 (0.3%) |

| Skin irritation | 1 (0.3%) |

| Skin lesion | 1 (0.3%) |

| Urticaria | 1 (0.3%) |

| Urticaria localized | 1 (0.3%) |

Data are number of patients (%)

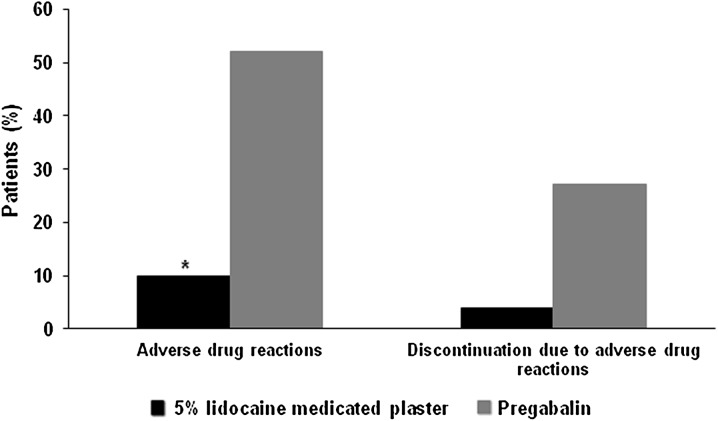

Comparison to Systemic Medication

The safety profile of the topical 5% lidocaine medicated plaster was directly compared to the systemic pain medication pregabalin in one open-label randomized non-inferiority study [17]. The PHN safety subset included 50 patients under 5% lidocaine medicated plaster treatment and 48 patients receiving pregabalin [19]. Mean age of the study population was 64.9 ± 11.8 years with a PHN duration of 3.0 ± 4.8 years. Fifty-five percent of the patients were male. These data were comparable between the groups. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster was significantly better tolerated than pregabalin during the 4-week comparative phase (P < 0.0001, exploratory). Five ADRs occurred in five (10%) patients treated with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster and included three mild or moderate application site reactions (erythema, paresthesia, and rash), a furuncle, and a mental disorder due to a general medical condition. The latter was an SAE, which was assessed to be possibly related to treatment by the investigator. The outcome was documented as resolved for 3 ADRs (60%) and resolving for 2 ADRs (40%). In contrast, 82 ADRs in 25 patients were reported for the pregabalin group (Fig. 2), mainly consisting of dizziness (9 patients/18.8%), fatigue (8/16.7%), somnolence (3/6.3%), and headache (3/6.3%). Twenty-two of these ADRs were of severe intensity. Nine of the 82 ADRs (11%) were reported as not resolved, resolved with sequelae, or had an unknown outcome. Two patients in the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster group (4%) and 13 receiving pregabalin (27.1%) discontinued treatment prematurely (Fig. 2). These ADRs were application site rash and mental disorder due to a general medical condition for the lidocaine plaster; main reasons for pregabalin discontinuation were fatigue (3 patients), dizziness (2), and somnolence (2).

Fig. 2.

Adverse drug reactions during 4-week treatment with the topical 5% lidocaine medicated plaster or systemic pregabalin [19]. *P < 0.0001 (exploratory) compared to pregabalin

Twenty-five patients receiving the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster and 14 pregabalin-treated patients had experienced sufficient pain relief during the 4-week comparative phase to continue treatment with their allocated medication in monotherapy for another 8 weeks. During this time, two patients in the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster group reported application site rash, application site erythema, and erythema and three patients under pregabalin reported dizziness and headache. All ADRs related to 5% lidocaine medicated plaster resolved; one pregabalin-related ADR of dizziness was not resolved. One patient in each treatment group withdrew prematurely due to an ADR (erythema for the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster, headache for pregabalin).

Long-term Treatment

In 2009, a prospective, open-label, multicenter, phase III, large-scale 12-month study investigated efficacy, safety, and patient satisfaction with the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in PHN treatment [20]. After completion of the main trial period, a total of 102 patients continued treatment with the plaster, and safety data are available for the complete treatment duration of more than 5 years [21]. The study population was predominantly elderly (mean age 71.3 ± 9.2 years) with a higher proportion of females (63.7%) and had been suffering from PHN for 2.6 ± 3.0 years. Patients applied a mean of 1.8 ± 0.6 plasters/day for up to 12 h daily.

Over the more than 5 years of treatment, the ADR incidence was low: 19 patients (18.6%) had 30 AEs that were considered by the investigators as probably/likely related (n = 13) or possibly related (n = 17) to 5% lidocaine medicated plaster treatment. None of these ADRs were serious. They were mainly application site reactions (14 patients) including hypersensitivity (4), erythema (3), irritation (3), pruritus (3), rash (2), and skin reaction (1) and resolved without further treatment after removal of the plaster. Investigators also classified dysgeusia, myalgia, hypoglycemia, unilateral deafness, tinnitus, tachycardia, paresthesia, pruritus, rash, skin irritation, and urticaria (all single cases) as possible ADRs. Only three patients (2.9%) discontinued the study prematurely, all due to drug-related application site hypersensitivities. Table 3 compares the safety data of this long-term trial to other pivotal open-label PHN trials.

Table 3.

Safety profile of open-label administration of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster for treatment of postherpetic neuralgia

| Any patient with | Pivotal phase 3 trial [18] | Phase 3 long-term trial | Phase 3 non-inferiority trial [19] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run-in period | Main period [20] | Extension [21] | Comparative phase | Lidocaine pick-up arm | ||

| Renally impaireda | Switchb | |||||

| N = 265 | N = 249 | N = 102 | N = 50 | N = 30 | N = 12 | |

| ADRc | 34 (12.8%) | 31 (12.4%) | 10 (9.8%) | 5 (10%) | 9 (30%) | 2 (16.7%) |

| Discontinuation due to an ADR | 11 (4.2%) | 11 (4.4%) | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (13.3%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Serious ADR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Discontinuation due to a serious ADR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

Data are number of patients (%)

aPatients with a creatinine clearance ≥30 ml/min and ≤60 ml/min at study entry; includes 3 patients erroneously receiving pregabalin in addition to 5% lidocaine medicated plaster

bSwitched from pregabalin arm during the comparative phase due to tolerability problems

cConsidered at least possibly related to 5% lidocaine medicated plaster treatment. ADR Drug-related adverse event/adverse drug reaction

Telephone follow-up interviews and a mailed survey also reported a good safety profile for the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in individual patients treated for PHN for up to 5 years [41] and 7 years [22], respectively.

Overall, the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster was well tolerated during long-term PHN treatment.

Further Open-Label Data

A prospective, multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized study on the effectiveness of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster regarding pain relief and improvement of quality of life in 332 patients with PHN (mean age 71 years, 60% female) observed localized rash as the most common ADR (12% of patients) [24]. ADRs related to the following system organ classes were reported: skin/subcutaneous disorders (40 patients/12%), nervous disorders (19/6%), general disorders and administration site conditions (16/5%), gastrointestinal disorders (5/2%), eye disorders (3/1%), immune system disorders (3/1%), psychiatric disorders (2/<1%), cardiac disorders, musculoskeletal, connective tissue and bone disorders, vascular disorders, ear and labyrinth disorders, and injury and poisoning (all 1/<1%). No serious systemic ADRs were reported.

In accordance with the clinical data, post-marketing experience of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster found application site reactions such as rash, pain, erythema, pruritus, skin irritation, and vesicles, the most commonly reported ADRs. Open wound, hypersensitivity, and anaphylactic reaction have been observed, but their occurrence was very rare (<1/10,000) [25].

Discontinuation of Treatment due to ADRs

For most studies, the rate of premature discontinuation due to ADRs was under 5% with the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster (Table 3) and markedly lower than with pregabalin (Fig. 2). A higher rate was observed in a subgroup of a trial with pregabalin as comparator which included patients with renal impairment (Table 3).

Safety in Special Patient Populations

This section summarizes the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster use in special patient populations investigated in clinical studies. Further clinical particulars are provided in the summary of product characteristics of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster [25]. The safety and efficacy of 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in children with PHN below 18 years have not been studied.

Elderly Patients

As the incidence of PHN increases with age [7–10], the majority of study patients were elderly with mean age ranging from 64.9 ± 11.8 to 77.3 ± 7.1 years in the studies reviewed here. Study results therefore generally apply to elderly patients.

Pharmacokinetic data showed a general trend for lidocaine absorption to decrease with increasing age (additional data from [33], on file). The amount of lidocaine reaching systemic circulation thus appears to be even lower in elderly patients.

Patients with Renal Impairment

Studies specifically investigating efficacy and safety of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in renally impaired patients have not been carried out. However, the active comparator study [19] contained a 5% lidocaine medicated plaster pick-up arm for patients with renal impairment (creatinine clearance ≥30 ml/min and ≤60 ml/min at study entry). Nine of the 30 renally impaired patients (30%) experienced a total of 20 ADRs (Table 3), of which 19 resolved by the end of the trial. Most were mild or moderate application site reactions. No serious ADRs were reported. Four patients (13.3%) discontinued prematurely due to skin-related ADRs.

The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster can be used without dose adjustments in patients with mild or moderate renal impairment, but should be used with caution in patients with severe renal dysfunction [25].

Patients with Hepatic Impairment

Studies specifically investigating efficacy and safety of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in patients with PHN with hepatic dysfunction have not been carried out. Dose adjustments are not required in patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment, but the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster should be used with caution in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction [25].

Cognitive Function

Cognitive integrity in elderly patients with PHN (mean age 72 ± 8 years) was maintained by treatment with the lidocaine plaster, whereas patients on systemic medication (in particular antidepressants) were significantly impaired in vigilance, decision making, and semantic memory [42]. Both treatment groups were compared to healthy volunteers matched by age and gender. The authors concluded that the cognitive impairment associated with pain and antidepressants might be reversed by topical pain treatment.

Discussion

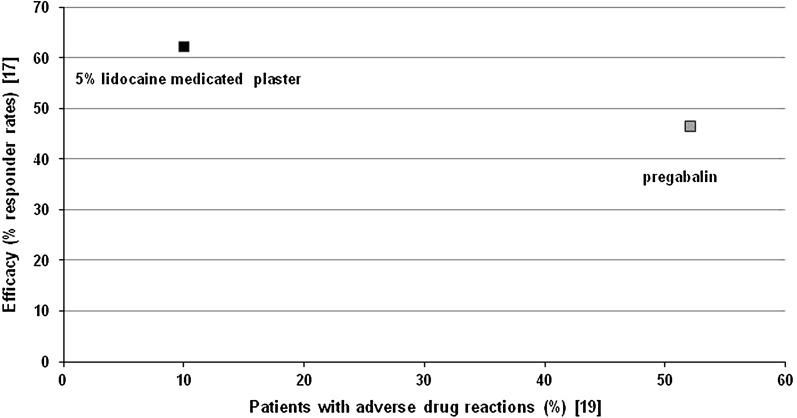

The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster is easy to use and, in contrast to systemic medications, does not require titration. The treatment was generally well tolerated by patients suffering from PHN. Most ADRs were of mild to moderate intensity, and treatment discontinuation due to ADRs was rare. The locally acting analgesic has a very low systemic exposure with maximum plasma concentrations well below cardiac therapy levels and potentially toxic concentrations, and without leading to lidocaine accumulation [28, 33, 34]. The risk of systemic ADRs and pharmacokinetic interaction with concomitant medications is therefore low, which allows for a good safety profile, during both short-term and long-term treatments. One trial of a direct comparison with the systemic analgesic pregabalin [19] points toward comparable efficacy of the two treatments in PHN pain relief, with a numerically lower ADR incidence with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster treatment (Fig. 3). This is in line with a current review on PHN treatment in medically complicated patients highlighting that topical therapies are a valuable treatment alternative or complementary treatment to systemic therapies in this patient group owing to comorbid disease states and pharmacokinetic drug interactions [43]. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster thus combines proven efficacy with an excellent safety profile in the treatment of PHN, thereby improving quality of life of the patients [17, 19, 24]. Treatment with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster improved quality of life as measured by EuroQol-5 dimension quality of life index (EQ-5D) health state to a greater extent than systemic treatment such as pregabalin [17]. With proven efficacy and a very limited potential for systemic side effects and interactions with other medications, 5% lidocaine medicated plaster might improve patients’ compliance to therapy. A recent analysis of a cross-sectional survey involving primary care physicians and pain specialists suggests higher health-related quality of life and low pain levels for treatment-compliant patients [44]. The study found a higher compliance and a better quality of life in patients receiving the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster compared to patients under systemic treatment. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster is a suitable first-line treatment as well as an alternative for patients unable to tolerate pregabalin [19]. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster is a good alternative in special risk groups, including elderly patients or patients with renal impairment. Moreover, owing to its lack of systemic ADRs, 5% lidocaine medicated plaster is a suitable treatment for car drivers or machine operators.

Fig. 3.

Efficacy/tolerability mapping on the basis of one prospective randomized controlled trial directly comparing the topical 5% lidocaine medicated plaster and systemic pregabalin in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia [17, 19]. Responder rates were defined as a reduction in pain intensity of at least 2 points or an absolute value of 4 or less on the 11-point numerical rating scale over the previous 3 days after 4 weeks of treatment

As expected for a topical medication, the most frequently reported ADRs to the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster were administration site reactions. Most application site reactions were of mild to moderate intensity and often resolved without further treatment after removal of the plaster. They were also mainly responsible for premature treatment discontinuations which occurred rarely (under 5% of patients).

Headache, nausea, dizziness, dysgeusia, and somnolence were occasionally reported. They are known central nervous system reactions which often occur in the general population and in particular in multimorbid elderly patients on concomitant medications. Dizziness is a frequent ADR with lidocaine systemically administered as a local anesthetic [45], and can be encountered when used as an antiarrhythmic agent [46]. However, lidocaine plasma concentrations following plaster application are about 1/10 of the concentration required for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias [47]; a causal relationship to plaster administration thus seems unlikely. Single cases of myalgia, hypoglycemia, unilateral deafness, tinnitus, tachycardia, and urticaria which were observed under long-term 5% lidocaine medicated plaster treatment were classified by investigators as possibly drug-related, according to Sabatowski et al. [21] probably because they are known ADRs for systemically administered lidocaine. However, as discussed before, when administering lidocaine via the topical-acting medicated plaster, the low systemic availability of lidocaine renders a causal relationship unlikely.

PHN incidence rates markedly increase with age [7–10] and many elderly patients experience substantial long-standing debilitating pain, dysfunction, and poor quality of life [4, 47]. Comorbidities, polypharmacy and thus possible drug–drug interactions with an increased risk of ADRs and noncompliance are the challenges of successful pain treatment in the elderly. Pharmacological PHN treatment is often suboptimal and levels of treatment dissatisfaction are high [48]. The majority of PHN patients in the reviewed studies were elderly with a mean age range from 64.9 ± 11.8 to 77.3 ± 7.1 years. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster showed a good safety profile with a low incidence of ADRs which, combined with efficient pain relief [23], provides an excellent benefit/risk ratio for the medication in this elderly patient population. Another particular concern in the elderly is an impairment of cognitive abilities by chronic pain which has been shown in several publications [49, 50]. Treatment with the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster maintained cognitive integrity in elderly patients with PHN, whereas systemic treatment, in particular with antidepressants, had a deleterious effect on several domains of cognition [42]. This finding adds to the good safety profile of the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster and renders it a valuable treatment option.

Conclusions

The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster demonstrated good short- and long-term tolerability with a minimal risk for systemic ADRs. The 5% lidocaine medicated plaster was better tolerated than systemic treatment with pregabalin in one trial. Mild to moderate application site reactions were the most frequent ADRs related to topical lidocaine treatment in a predominantly elderly population with PHN. Combined with efficient pain relief, the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster provides a safe treatment alternative to systemic medications for PHN treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance for the preparation of the manuscript was provided by Elke Grosselindemann and Birgit Brett. This assistance and the article processing charges were supported by Grünenthal GmbH, Aachen, Germany. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

MLN received honorarium for lectures and service on advisory boards from Grünenthal GmbH, Astellas und Mundipharma. CM received travel support, education support and honorarium from Grünenthal, Pfizer, Astellas, Napp and Servier. IB is an employee of Grünenthal GmbH. DS is an employee of Grünenthal GmbH. CD received honorarium, travel support and education workshop support from Grünenthal, Astellas, Mundipharma and Teva France.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This review is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Johnson RW, McElhaney J. Postherpetic neuralgia in the elderly. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1386–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dworkin RH, Gnann JW, Oaklander AL, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of pain associated with herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Pain. 2008;9(Suppl. 1):S37–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RW, Wasner G, Saddier P, et al. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. Optimizing management in the elderly patient. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:991–1006. doi: 10.2165/0002512-200825120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson RW, Bouhassira D, Kassianos G, et al. The impact of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia on quality-of-life. BMC Med. 2010;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lukas K, Edte A, Bertrand I. The impact of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia on quality of life: patient-reported outcomes in six European countries. J Public Health. 2012;20:441–451. doi: 10.1007/s10389-011-0481-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nalamachu S, Morley-Forster P. Diagnosing and managing postherpetic neuralgia. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:863–869. doi: 10.1007/s40266-012-0014-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, et al. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1341–1349. doi: 10.4065/82.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gauthier A, Breuer J, Carrington D, et al. Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in the United Kingdom. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:38–47. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gialloreti LE, Merito M, Pezzotti P, et al. Epidemiology and economic burden of herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in Italy: a retrospective, population-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cebrián-Cuenca AM, Díez-Domingo J, San-Martín-Rodríguez M, et al. Epidemiology and cost of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia among patients treated in primary care centres in the valencian community of Spain. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:302. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(Suppl):S3–S14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, et al. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:1113-e88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Boesl I, Koenig S. More than 20 million patients used 5% lidocaine medicated plaster: an update on its safety profile. PainWeek. 2014. http://conference.painweek.org/media/mediafile_attachments/04/724-painweek2014acceptedabstracts.pdf. Accessed Mar 24, 2015.

- 15.Rowbotham MC, Davies PS, Verkempinck C, et al. Lidocaine patch: double-blind controlled study of a new treatment method for post-herpetic neuralgia. Pain. 1996;65:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galer BS, Rowbotham MC, Perander J, et al. Topical lidocaine patch relieves postherpetic neuralgia more effectively than a vehicle topical patch: results of an enriched enrollment study. Pain. 1999;80:533–538. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baron R, Mayoral V, Leijon G, et al. 5% lidocaine medicated plaster versus pregabalin in post-herpetic neuralgia and diabetic polyneuropathy: an open-label, non-inferiority two-stage RCT study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1663–1676. doi: 10.1185/03007990903047880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binder A, Bruxelle J, Rogers P, et al. Topical 5% lidocaine (lignocaine) medicated plaster treatment for post-herpetic neuralgia: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational efficacy and safety trial. Clin Drug Investig. 2009;29:393–408. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200929060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehm S, Binder A, Baron R. Post-herpetic neuralgia: 5% lidocaine medicated plaster, pregabalin, or a combination of both? A randomized, open, clinical effectiveness study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1607–1619. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.483675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hans G, Sabatowski R, Binder A, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a 5% lidocaine medicated plaster for the topical treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia: results of a long-term study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1295–1305. doi: 10.1185/03007990902901368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabatowski R, Hans G, Tacken I, et al. Safety and efficacy outcomes of long-term treatment up to 4 years with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in patients with post-herpetic neuralgia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:1337–1346. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.707977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galer BS, Gammaitoni AR. More than 7 years of consistent neuropathic pain relief in geriatric patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:628. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.5.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mick G, Correa-Illanes G. Topical pain management with the 5% lidocaine medicated plaster—a review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:937–951. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.690339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz NP, Gammaitoni AR, Davis MW, et al. Lidocaine patch 5% reduces pain intensity and interference with quality of life in patients with postherpetic neuralgia: an effectiveness trial. Pain Med. 2002;3:324–332. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Electronic Medicines Compendium. Versatis 5% medicated plaster. Summary of product characteristics. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/19291/SPC/Versatis+5++Medicated+Plaster/. Accessed Feb 2014.

- 26.Nalamachu S, Wieman M, Bednarek L, et al. Influence of anatomic location of lidocaine patch 5% on effectiveness and tolerability for postherpetic neuralgia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:551–557. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S42643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krumova EK, Zeller M, Westermann A, et al. Lidocaine patch (5%) produces a selective, but incomplete block of Aδ and C fibers. Pain. 2012;153:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gammaitoni AR, Alvarez NA, Galer BS. Pharmacokinetics and safety of continuously applied lidocaine patches 5% Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59:2215–2220. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.22.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baliki MN, Geha PY, Jabakhanji R, et al. A preliminary fMRI study of analgesic treatment in chronic back pain and knee osteoarthritis. Mol Pain. 2008;4:47. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Correa-Illanes G, Calderón W, Roa R, et al. Treatment of localized post-traumatic neuropathic pain in scars with 5% lidocaine medicated plaster. Local Reg Anesth. 2010;3:77–83. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S13082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasner G, Kleinert A, Binder A, et al. Postherpetic neuralgia: topical lidocaine is effective in nociceptor-deprived skin. J Neurol. 2005;252:677–686. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0717-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustorff B, Hauer D, Thaler J, et al. Antihyperalgesic efficacy of 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in capsaicin and sunburn pain models—two randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover trials in healthy volunteers. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:2781–2790. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.601868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell BJ, Rowbotham M, Davies PS, et al. Systemic absorption of topical lidocaine in normal volunteers, patients with post-herpetic neuralgia, and patients with acute herpes zoster. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91:1343–1350. doi: 10.1002/jps.10133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gammaitoni AR, Davis MW. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of lidocaine patch 5% with extended dosing. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:236–240. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benowitz NL, Meister W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lignocaine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1978;3:177–201. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197803030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jürgens G, Graudal NA, Kampmann JP. Therapeutic drug monitoring of antiarrhythmic drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:647–663. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilhelm IR, Griessinger N, Koppert W, et al. High doses of topically applied lidocaine in a cancer patient. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;30:203–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000;356:1255–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02799-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowbotham MC, Davies PS, Galer BS. Multicenter, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial of long-term use of lidocaine patches for postherpetic neuralgia. In: Abstracts of the 8th World congress of the International Association for the Study of Pain (Vancouver BC, Canada, August 17–22). 1996; 274, abstract 184.

- 40.Galer BS. Advances in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: the topical lidocaine patch. Today’s Ther Trends. 2000;18:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilhelm IR, Tzabazis A, Likar R, et al. Long-term treatment of neuropathic pain with a 5% lidocaine medicated plaster. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:169–173. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328330e989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pickering G, Pereira B, Clère F, et al. Cognitive function in older patients with postherpetic neuralgia. Pain Pract. 2014;14:E1–E7. doi: 10.1111/papr.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruckenthal P, Barkin RL. Options for treating postherpetic neuralgia in the medically complicated patient. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2013;9:329–340. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S47138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Hara J, Obradovic M, Liedgens H, et al. Relationship between compliance and patient reported outcomes (PROS) in post herpetic neuralgia with insight into lidocaine medicated plaster (LMP) use. In: Abstract 170 of the 8th Congress of the European Federation of IASP Chapters (EFIC), 9–12 October 2013, Florence. European Pain Federation EFIC; 2013.

- 45.Tremont-Lukats IW, Challapalli V, McNicol ED, et al. Systemic administration of local anesthetics to relieve neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1738–1749. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000186348.86792.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anderson JL. Current understanding of lidocaine as an antiarrhythmic agent: a review. Clin Ther. 1984;6:125–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gammaitoni AR, Alvarez NA, Galer BS. Safety and tolerability of the lidocaine patch 5%, a targeted peripheral analgesic: a review of the literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:111–117. doi: 10.1177/0091270002239817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oster G, Harding G, Dukes E, et al. Pain, medication use, and health-related quality of life in older persons with postherpetic neuralgia: results from a population-based survey. J Pain. 2005;6:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eccleston C, Crombez G, Aldrich S, et al. Attention and somatic awareness in chronic pain. Pain. 1997;72:209–215. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seminowicz DA, Davis KD. A re-examination of pain-cognition interactions: implications for neuroimaging. Pain. 2007;130:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.