Abstract

Background

Varying degrees of cortical amyloid deposition are reported in the setting of Parkinsonism with cognitive impairment. We performed a systematic review to estimate the prevalence of Alzheimer disease (AD) range cortical amyloid deposition amongst patients with Parkinson disease with dementia (PDD), Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). We included amyloid PET imaging studies using Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB).

Methods

We searched the databases Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science for articles pertaining to amyloid imaging in Parkinsonism and impaired cognition. We identified 11 articles using PiB imaging to quantify cortical amyloid. We used the metan module in Stata, version 11.0, to calculate point prevalence estimates of patients with “PiB-positive” studies, ie patients showing AD range cortical Aβ-amyloid deposition. Heterogeneity was assessed. A scatterplot was used to assess publication bias.

Results

Overall pooled prevalence of “PiB-positive” studies across all three entities along the spectrum of Parkinson disease and impaired cognition (specifically PDD, PD-MCI and DLB) was 0.41 (95% CI 0.24-0.57). Prevalence of “PiB-positive” studies was 0.68 (95% CI 0.55-0.82) in the DLB group, 0.34 (95% CI 0.13-0.56) in the PDD group and 0.05 (95% CI -0.07-0.17) in the PD-MCI group.

Conclusion

There is substantial variability in the prevalence of “PiB-positive” studies in subjects with Parkinsonism and cognitive impairment. Higher prevalence of PiB positive studies was encountered among subjects with DLB as opposed to subjects with PDD.

PD-MCI subjects showed overall lower prevalence of PiB positive studies than reported findings in non-PD related MCI.

Keywords: Parkinson disease, PDD, DLB, MCI, Systematic Review

Introduction

Parkinson Disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder and is characterized by progressive motor and cognitive impairments. The risk of developing dementia in the setting of PD is 2 to 6 times higher than in the general population, corresponding to lifetime risk estimates of 30-80%[1, 2].

Parkinson Disease with Dementia (PDD) is related closely to Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). DLB is the second most common neurodegenerative dementia accounting for up to 20% of dementia cases [3, 4]. The key similarity between PDD and DLB is the requirement for synucleinopathy in characteristic regional depositions in the context of dementia. Distinction between the two entities is based currently upon the “one-year rule”, with subjects presenting with dementia before or within one year of developing parkinsonism classified as DLB and those developing dementia more than one year after PD diagnosis classified as PDD[5]. Although it was hoped that the PDD-DLB clinical classification would improve diagnostic homogeneity and highlight distinctions between the two syndromes, subsequent studies have shown substantial overlap of PDD and DLB phenotypes in a number of clinical and neuropathologic investigations [6-9].

Recently developed molecular imaging approaches permit the detection of pathological accumulations of Aβ-amyloid plaques [10]. Amyloid plaques are demonstrated commonly in both PDD and DLB on neuropathologic examinations [6, 8, 11, 12]. A number of amyloid PET imaging studies have been performed in the setting of PD, PDD and DLB [13-23]. Although there is a wide range of amyloid deposition and relatively few subjects in most individual studies, there is an overall impression that higher levels of neocortical amyloid deposition (similar to those encountered in the setting of Alzheimer disease [AD]) are more frequent in DLB than PDD. Potentially more interesting is the impression that higher levels of amyloid deposition are less frequent in PD with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) compared to frequencies reported in cognitively normal elderly subjects [16, 19, 21, 23]. Delineating the frequency of AD-range amyloid deposition in patients with parkinsonism and cognitive impairment, specifically in the context of individual clinical subtypes (ie PDD, DLB and PD-MCI) is a prerequisite for understanding the role of amyloid in the multisystem neurodegeneration of PD. Prior amyloid imaging studies of PD and DLB are largely smaller series with relatively heterogeneous subject populations and varying imaging methods.

To help delineate important questions for future research, we undertook a systematic review – meta-analysis of prior amyloid imaging studies of DLB, PPD, and PD-MCI. Because of the relatively small number of aggregate subjects and varying methods of imaging data analysis (see below), we selected high (AD-range) levels of neocortical amyloid deposition as the most robust endpoint for comparing amyloid deposition in the DLB, PDD, and PD-MCI groups.

The specific objective purpose of this systematic review is to estimate the frequency of “amyloid positive” subjects amongst patients with DLB, PDD and PD with MCI. We define “amyloid positive” as exhibiting AD-range cortical amyloid deposition on brain PET imaging performed with Pittsburgh compound B (PiB)[hence the term “PiB-positive” also used] with thresholds determined by the individual laboratories where each study was performed.

Methods

Information Sources/Study Search Strategy

In February 2013, we systematically searched Ovid MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science for articles pertaining to amyloid imaging in Parkinson Disease Dementia. MeSH and EMTREE vocabularies were used whenever possible, along with keyword variations of the imaging and disease terms. The initial search was run in Ovid Medline and then translated to the other databases (See supplementary material for the complete Ovid MEDLINE strategy). In all searches, non-English studies were excluded from the results, but no other limits or restrictions were applied. The combined yield of all searches was 938 citations, of which 509 were identified as duplicates in Endnote X5 (Thomson Reuters). The resulting set of 429 unique citations were exported into Excel and distributed to the lead author for screening.

Study Selection

We included a study if it satisfied the following criteria: human studies using PiB for amyloid brain PET imaging in subjects with PDD and/or PD-MCI and/or DLB, >3 subjects/disease category, and subject mean ages included in the provided data. Studies involving duplicated data were identified and the larger dataset only was included.

Data Collection and Extraction

Two reviewers (M.P., B.R.F.) independently evaluated each abstract for inclusion. Next, we obtained full publications for further assessment and data extraction. The same reviewers independently reviewed each article and reached a final consensus for inclusion. These reviewers abstracted the information from the eligible articles: author, journal, year or publication, number of subjects, demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects as well as the method of PiB PET image classification into positive vs negative (based on volume of distribution [DV] or based on standard uptake values [SUV] measurements). Numbers of “PiB-positive” vs “PiB-negative” subjects per clinical classification group were the main outcome of interest extracted from the included studies.

Assessment of Methodologic Quality

Two reviewers (M.P., B.R.F.) independently assessed the quality of each study according to the QUADAS criteria [24]. These criteria assessed that there was adequacy of index test description, adequacy of reference standard likely to correctly classify disease, adequacy of reference standard test description, blinded interpretations of index tests, absence of differential verification bias, absence of incorporation bias, absence of partial verification bias, whether a representative spectrum of diseased patients will receive the test in practice, whether selection criteria were clearly described, if there was a short period between index and reference tests and whether uninterpretable results were reported. Each of these criteria were scores as “yes”, “no” or “unclear”. All studies classified subjects as having DLB based on the revised consensus criteria [5]. In 5/6 studies which included PDD subjects, diagnosis of PDD was based on the relative timing of dementia and Parkinsonism. Diagnosis of PD in these subjects was based on the UKPDS brain bank criteria[25] in 4 of the studies and on criteria proposed by Larsen et al [26] in one study [17]. Diagnosis of dementia was based on DSM-IV criteria [27] in these 5 studies. In 1/6 studies including PDD subjects, neuropsychological testing outcomes were used to determine the presence of dementia [23] in the presence of PD. Determination of PD-MCI was more variable and based on neuropsychological testing outcomes. Representative disease spectrum was also determined on the basis of included range of neuropsychological testing outcomes. Any disagreements in abstracted results between the reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Statistical Analysis

We used the metan module in Stata, version 11.0, to calculate the frequency estimates of PiB positive studies among the PDD, PD-MCI and DLB groups using random effects modeling. The 95% confidence intervals for these were also calculated. Data were intrinsically weighed by using individual study variances.

Assessment of Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed using the quantity I2 as defined by I2 = 100% × (Q-df)/Q where I2 is a measure of consistency across studies, Q is the Cochran's heterogeneity statistic and df is the degrees of freedom. Higgins et al propose describing I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% as low, moderate and high between trial heterogeneity [28]. We obtained the I2 values as output of the metan program.

Testing for Publication Bias

A scatterplot of the estimated point prevalence versus the corresponding study's standard error measurement was used to assess publication/small sample bias. The scatterplot should have a symmetric distribution when publication bias is not present. A linear regression of the point prevalence of PiB positive subjects versus standard error measurement was also used for publication bias assessment, with P < 0.05 indicating significant asymmetry.

Results

Study Selection

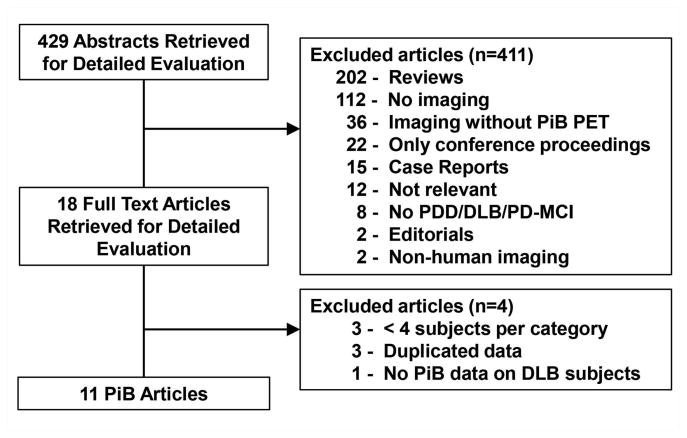

Numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility and included in the review, with reasons for exclusion at each stage is given in Figure 1. The search yielded 429 literature citations for potential inclusion. We excluded a total of 389 studies because they were review-based articles, did not include imaging, did not specifically include PiB imaging, did not include subjects with DLB or PDD, did not include human subjects or were case reports. Of the 40 studies that fulfilled criteria only 18 were full-length publications; rest of the studies were reported in abstracts included in conference proceedings. One of the 18 studies did not include PiB data on DLB patients, one of the studies only included one DLB subject, one study only included 3 PDD subjects and one study included 3 DLB subjects. Three additional studies were excluded based on overlapping data with the included studies. A total of 11 studies were included in the analysis.

Figure 1. Flowchart illustrates the selection of studies.

PiB = Pittsburgh compound B, PET = positron emission tomography, PDD = Parkinson disease with dementia, DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies, PD-MCI = Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment.

Study Characteristics

The 11 included studies involved 74 subjects diagnosed with PDD, 99 subjects with DLB and 60 subjects with PD and mild cognitive impairment. The studies were published between 2007 and 2013 (Table 1). Three studies were performed in Europe, 6 in North America 1 in Asia and 1 in Australia. Six studies determined “PiB-positive” vs “PiB-negative” status based on measures of DV. Five studies determined “PiB-positive/negative” status based on SUV measurements of the radiotracer uptake.

Table 1.

Individual Study Characteristics.

| Study Number | Author | Year | Origin | Age of Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Burke | 2011 | USA | DLB: 72 (54-90) |

| 2 | Edison | 2008 | UK | DLB: 72 (62-80) |

| PDD: 69 (56-80) | ||||

| PD-MCI: 68 (58-73) | ||||

| 3 | Foster | 2010 | USA | DLB: 71 |

| PDD: 75 | ||||

| PD-MCI: 73 | ||||

| 4 | Gomperts | 2012 | USA | DLB: 72 |

| PDD: 73 | ||||

| PD-MCI: 69 | ||||

| 5 | Gomperts | 2013 | USA | PD-MCI: 67 |

| 6 | Jokinnen | 2010 | Finland | PDD: 72 (56-79) |

| 7 | Kantarci | 2012 | USA | DLB: 73 (60-87) |

| 8 | Maetzler | 2009 | Germany | DLB: 69 (62-75) |

| PDD: 70 (62-80) | ||||

| 9 | Petrou | 2012 | USA | PDD: 70 (60-84) |

| PD-MCI: 70 (60-84) | ||||

| 10 | Rowe | 2007 | Australia | DLB: 72 (63-81) |

| 11 | Shimada | 2013 | Japan | DLB: 73 |

Abbreviations: UK = United Kingdom; USA = United States of America. PDD = Parkinson disease with dementia, DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies, PD-MCI = Parkinson Disease with mild cognitive impairment

Point Prevalence Estimates

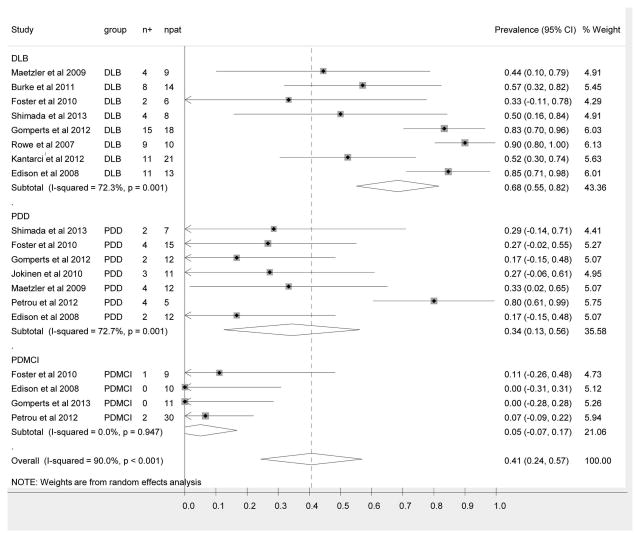

Figure 2 shows the forest plot of the point prevalence values. The overall pooled prevalence of “PiB-positive” studies in the setting of Parkinson disease and cognitive impairment is 0.41 (95% CI (0.24-0.57). The pooled prevalence of “PiB-positive” scans among the DLB group is 0.68 (95% CI 0.55-0.82). The pooled prevalence of “PiB- positive” scans among the PDD group is 0.34 (95% CI 0.13-0.56). The pooled prevalence of PiB positive scans among the PD-MCI group is 0.05 (95% CI -0.07-0.17).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of point prevalence of PiB positive studies among the three entities encompassed by parkinsonism and cognitive impairment, specifically PDD, DLB and PD-MCI. The center point represents the estimated point prevalence for the respective study and the horizontal line, the 95% confidence interval for the respective study. The vertical broken line represents the pooled point prevalence and the boundaries of the hollow diamond represents the 95% CI of the pooled results. PDD = Parkinson disease with dementia, DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies, PD-MCI = Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment, n+ = number of subjects positive for amyloid, npat = total number of patients in each study.

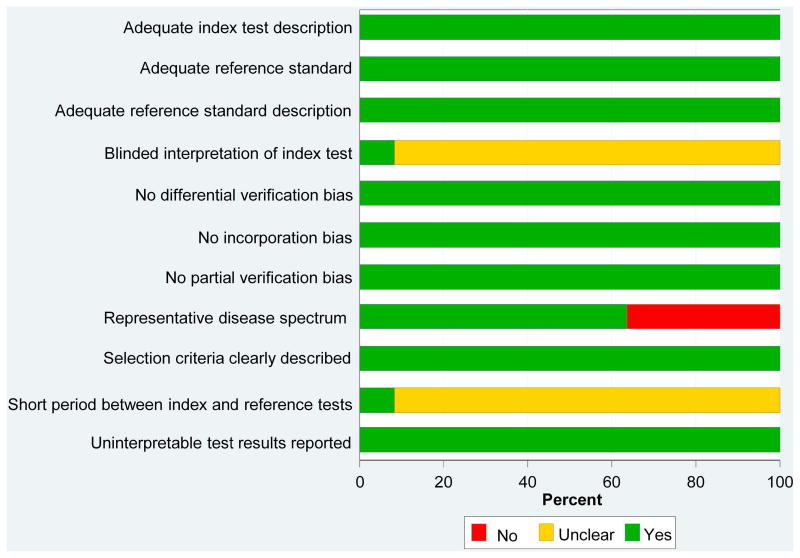

Assessment of Methodological Quality

Study quality scores ranged from 7 to 10 of a possible score of 11 (Figure 3). Overall, study quality scores were high. Almost 40% of the studies do not include a representative disease spectrum in terms of disease severity, with most demented subjects only having mild disease. This likely reflects the difficulties in performing imaging studies in patients with moderate and severe dementia. The vast majority of studies did not explicitly state whether the interpretation of the index test was blinded or whether there was a short period of time between the reference and the index testing.

Figure 3.

Study Quality Scores. Graph illustrates study quality based on QUADAS criteria, expressed as a percent of studies meeting each criterion.

Assessment of Heterogeneity

The point prevalence estimates for the 11 studies demonstrated a high level of heterogeneity using the mixed model analysis (I2 = 90%; P < 0.001). The subanalyses of the point prevalence for the DLB and PDD subgroups demonstrated a much higher level of heterogeneity (I2 = 72%; P < 0.001 and I2 = 73%; P < 0.001 respectively) compared to the PD-MCI subgroup (I2 = 0%; P = 0.95).These findings highlight the heterogeneity in these clinical syndromes, especially as the diseases evolve beyond the initial MCI stage.

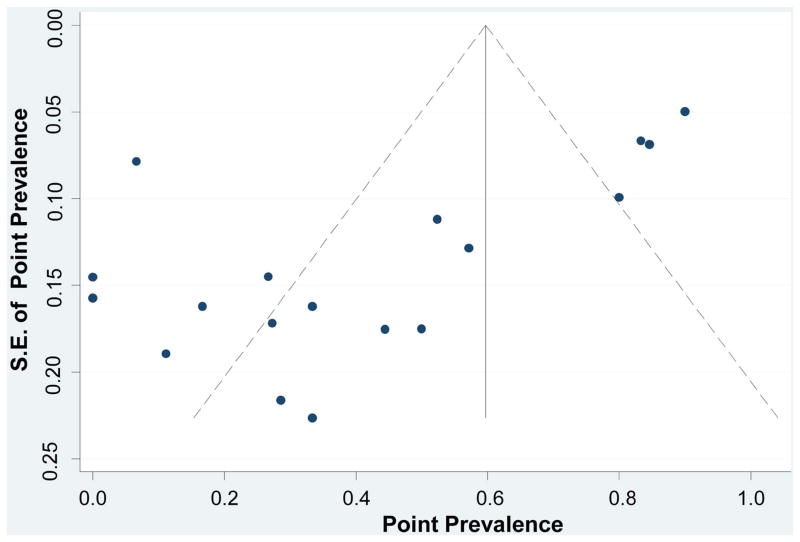

Publication Bias

As seen in the scatterplot (Figure 4), there was an asymmetric distribution of the data with a tendency of the studies with a lower standard of error to have higher point prevalence. Regression analysis demonstrated a significant publication bias (bias coefficient = -4.82; P < 0.001). Again, the findings indicate the significant heterogeneity of the investigated diseases and associated effects of small samples on estimates of the frequency of AD-range amyloidopathy.

Figure 4.

Assessing Publication Bias. The funnel plot horizontal axis expresses treatment effect, in this instance, measured by point prevalence. The vertical axis expresses study size, as measured by standard error (S.E.). Studies with larger standard errors have a wider confidence interval (CI) due to smaller sample size. The graphed vertical line represents the point prevalence and the dashed lines represent the 95% confidence limits for the expected distribution for published studies. The points represent the observed distribution of the published studies. Visual inspection of the plot demonstrates the presence of publication bias, with many studies outside the 95% confidence limits.

Discussion

Relative timing and severity of cognitive impairment in the setting of Parkinsonism is currently used to assign the diagnoses of PD-MCI, PDD and DLB. Despite the acknowledged central role of amyloid plaques in AD and a general impression that amyloid deposition is an important contributor to cognitive impairments in synucleinopathies, there are relatively few in-vivo imaging studies of Aβ-amyloid deposition in dementias associated with synucleinopathy. Therefore, our systematic review of the existing, smaller studies in this setting is pertinent. Our results indicate substantial variability in AD range cortical amyloid deposition, as determined by PiB PET imaging positivity among patients with Parkinsonism and cognitive impairment classified clinically as PDD, PD-MCI and DLB. To frame the potential significance of this analysis, a brief summary of the relationship of Aβ-amyloid deposition in the more common setting of AD follows.

Moderate to high levels of Aβ-amyloid plaque density are required for pathologic diagnosis of AD [29]. Recent in vivo imaging studies of fibrillary amyloid deposition with PiB and related tracers confirm that high percentages of clinically diagnosed probable AD patients are amyloid positive [30]. The minor fractions that are amyloid negative are probably due to clinical mis-classification of frontotemporal dementias or of pure DLB as probable AD [13], with the intriguing and recently described phenomenon of Suspected Non-Amyloid Pathology (SNAP) an additional potential contributor [31]. Comparative amyloid imaging and pathological confirmatory studies support for the most part the image based classification of individual subject amyloid status [32, 33]. The necessary role of high level cortical amyloid deposition in AD (cascade hypothesis) is supported by the frequency of PiB-positive findings in MCI without PD and the significant although lower frequency of PiB positivity in asymptomatic normal elderly subjects [34-37]. Recent study of monogenic AD indicates onset of amyloid deposition more than a decade before symptomatic cognitive deficits, supporting the concept that initial amyloid deposition predates significant neurodegeneration and symptom onset [38]. Similarly, recent imaging data suggests that cortical amyloid deposition plateaus at high levels prior to onset of cognitive impairment in AD [39]. Against this background, our findings in synucleinopathy subjects are significantly divergent.

Not surprisingly, and consistent with pathologic studies, a significant fraction of DLB and PDD subjects had sub-threshold amyloid levels, indicating the neurodegeneration secondary to synucleinopathy is driving cognitive decline in these individuals. Second, there are substantial differences in PiB positive prevalence among PDD and DLB subjects, with minimal overlap in the 95% confidence intervals. There was an overall lower frequency of PiB positive in PDD than DLB subjects. A plausible explanation for this observation is a cumulative effect of 2 major pathologies; the majority of previously asymptomatic subjects with high neocortical amyloid burden and significant synucleinopathy will present with dementia and therefore be classified as having DLB (or AD if parkinsonism is not yet clinically evident). This “classification” bias inherent to the one-year rule of relative timing of dementia and parkinsonism could explain the differential rates of PiB positive studies among different diagnostic groups. Frequency of amyloidopathy in PDD/DLB may be related to patient age as well as disease duration. For example, the Sydney Multicenter Study of PD showed that longer duration of disease us increasingly accompanied by co-morbid AD pathology, especially after 5 years[40].

We find a low frequency of PiB-positivity in PD-MCI compared not only with DLB and PDD but also as compared with reports in non-PD associated MCI. Furthermore, the mean prevalence of amyloid positivity in PD-MCI is lower than mean values reported in cognitively normal elderly controls, although there is overlap in confidence intervals with those reported in series of normal elderly with no diagnosis of neurologic disease. High neocortical amyloid deposition in MCI and normal elderly controls is inferred to be part of sequential cascade leading to AD with the presence of high amyloid deposition on PET imaging associated with high increase of risk for ultimate progression to AD. One possible explanation of this marked discrepancy is a strong form of the selection phenomenon suggested above to account for the differential frequency of high neocortical amyloid deposition in PDD versus DLB. Another intriguing possibility is that the PD brain is less hospitable to the generation of fibrillar amyloid. Recent data suggests that changes in neurotransmitter systems influences amyloid precursor protein metabolism significantly [41, 42].

Our study has limitations. None of the reviewed reports utilized the true gold standard for PDD/DLB, - autopsy. There was variability in the degree of cognitive impairment of subjects between reports and PD-MCI, in particular, is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome with variable definitions. Patients with severe dementia were not included in the majority of studies, presumably due to inability to cooperate with the imaging protocol. Furthermore, the age distribution, with mean ages of around 70 years is not fully representative of the PD population as a whole. It is important to note that given expected age associated increases in amyloid deposition, interrogating amyloidopathy at younger ages within the disease spectrum may limit confounding age effects and provide more insight into the role of amyloid deposition in synucleinopathy associated cognitive impairments. Classification of dementia may be based on varying degrees of prospective/retrospective data in different centers. ApoE status which is known to affect amyloid deposition was not reported in a most of these studies and therefore was not part of the analysis [43]. All studies reviewed came from tertiary referral centers and subject recruitment is subject to referral biases. There is definite heterogeneity in the PiB imaging and image processing protocols across different laboratories, reflecting technical imaging preferences and practices. Our analysis is based on the presence of AD-range cortical Aβ-amyloid deposition, as this was the criterion used to classify subjects as “PiB positive” and reported in the collection of studies summarized in this systematic review. Our pragmatic approach of accepting each laboratory's classification of PiB imaging studies into “positive” or “negative” based on lab-specific determination of this categorical outcome attempts to moderate these technical differences between facilities, but is associated with inherent limitations. One of the limitations of bridging differences between laboratories via a categorical approach to cortical amyloid quantification analysis is the inability to assess the significance of cortical amyloid levels below the AD-range. Such an endeavor would involve treating cortical amyloid as a continuous variable which is not possible given the differences between imaging and post-processing parameters and associated reported outcomes. Although PiB PET has a finite detection threshold and cases with amyloid plaques at biopsy or autopsy occupying less than 2 % of the microscopic field are classed as PiB negative, this is unlikely to confound our analysis based on AD range cortical amyloid deposition.

Levels of Aβ-amyloid deposition below AD-range thresholds may have clinical salience in Lewy body diseases, where a multisystem neurodegenerative process takes place. Our own data suggests a significant correlation between lower than AD-range levels of neocortical Aβ-amyloid deposition and cognitive function in PD patients at risk for dementia [23]. Further supporting this notion of an “amplified” effect on cognition of low levels of cortical amyloid in the setting of a synucleinopathy are the neuropathologic findings by Compta et al [11] suggesting that the combination of cortical amyloid deposits and presence of cortical Lewy bodies may be the best predictor of cognitive decline in Parkinson disease patients. Our group has also shown that neocortical Aβ-amyloid deposition and cholinergic degeneration are independent predictors of impaired cognition in the setting of Parkinson disease. This further supports the idea of a lower symptomatic threshold for effects of amyloidopathy than the levels defined in the AD population – a concept consistent with the selection effects raised above.

The studies reviewed contained relatively small numbers of subjects, constraining the analytic power of our review and explaining the significant publication/small sample size bias. We aggregated he results of the relatively small numbers of subjects from individual amyloid imaging studies to provide a more robust quantitative estimate of the prevalence of amyloid deposition in these subject groups. Our analysis suggests substantial variability in AD-range cortical Aβ-amyloid deposition across the entire spectrum of patients with synucleinopathy and impaired cognition. Establishing the prevalence and understanding the role of amyloidopathy in parkinsonian patients with cognitive impairment is important as emerging targeted amyloid related interventions may be applicable to these patient populations. This analysis exposes the need for prospective, systematic, larger studies employing uniform recruitment, clinical and imaging characterization protocols and concurrent evaluation of vulnerable neuronal populations in synucleinopathies to clarify the roles of amyloidopathy in synucleinopathy related cognitive impairments. Analysis of early PD and PD-MCI populations may be particularly interesting as confirmation of lower cortical amyloid deposition in these populations may be provide clues into the modulation of amyloid precursor protein metabolism and deposition in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by USPHS P50NS091856 (University of Michigan Morris K. Udall Center of Excellent for Parkinson's Disease Research).

Footnotes

Relevant Disclosures: Dr. Petrou has research support from the Radiological Society of North America.

Dr. Dwamena has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Foerster has no relevant disclosures.

Mr. MacEachern has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Bohnen has research support from the NIH, Department of Veteran Affairs and the Michael J.Fox Foundation.

Dr. Muller has support from the NIH, Department of Veteran Affairs and the Michael J.Fox Foundation.

Dr. Albin serves on the editorial boards of Neurology, Experimental Neurology, and Neurobiology of Disease. He receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health, and the Michael J.Fox Foundation. Dr. Albin serves on the Data Safety and Monitoring Board of the PRIDE-HD trial.

Dr. Frey has research support from the NIH, GE Healthcare and AVID Radiopharmaceuticals (Eli Lilly subsidiary). Dr. Frey also serves as a consultant to AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, MIMVista Inc., Bayer-Schering and GE healthcare. He also holds equity (common stock) in GE, Bristol-Myers, Merck and Novo-Nordisk.

Author contributions: Dr. Petrou: Study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation; manuscript preparation.

Dr. Dwamena: Data analysis and interpretation.

Dr. Foerster: Acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Mr. MacEachern : Acquisition of data(database search).

Dr. Bohnen: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Dr. Muller: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Dr. Albin: Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Dr. Frey: Study concept and design; analysis and interpretation; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Full Disclosures: Dr. Petrou has research support from the NIH, the Radiological Society of North America, the Department of Veteran Affairs and Pfizer Inc..

Dr. Dwamena has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Foerster has research support from the NIH, the Department of Veteran Affairs and the A.Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute.

Mr. MacEachern has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Bohnen has research support from the NIH, Department of Veteran Affairs and the Michael J.Fox Foundation.

Dr. Muller has support from the NIH, Department of Veteran Affairs and the Michael J.Fox Foundation.

Dr. Albin received compensation for expert witness testimony in litigation regarding dopamine agonist induced impulse control disorders. Dr. Albin serves on the editorial boards of Neurology, Experimental Neurology, and Neurobiology of Disease. He receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health, CHDI, Michael J.Fox Foundation and the Department of Veteran Affairs. Dr. Albin served on the Data Safety and Monitoring Boards of the TV820-CNS-20002 trial.

Dr. Frey has research support from the NIH, GE Healthcare and AVID Radiopharmaceuticals (Eli Lilly subsidiary). Dr. Frey also serves as a consultant to AVID Radiopharmaceuticals, MIMVista Inc., Bayer-Schering and GE healthcare. He also holds equity (common stock) in GE, Bristol-Myers, Merck and Novo-Nordisk.

Supplementary material 1: Terms Used for the Ovid MEDLINE Search

References

- 1.Halliday G, et al. The progression of pathology in longitudinally followed patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115(4):409–15. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarsland D, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of dementia in Parkinson disease: an 8-year prospective study. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(3):387–92. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boot B. The incidence and prevalence of dementia with Lewy bodies is underestimated. Psychol Med. 2013;43(12):2687–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vann Jones SA, O'Brien JT. The prevalence and incidence of dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review of population and clinical studies. Psychol Med. 2014;44(4):673–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKeith IG, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jellinger KA. Significance of brain lesions in Parkinson disease dementia and Lewy body dementia. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2009;24:114–25. doi: 10.1159/000197890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippa CF, et al. DLB and PDD boundary issues: diagnosis, treatment, molecular pathology, and biomarkers. Neurology. 2007;68(11):812–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256715.13907.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halliday GM, et al. Neuropathology underlying clinical variability in patients with synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122(2):187–204. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0852-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuboi Y, Uchikado H, Dickson DW. Neuropathology of Parkinson's disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies with reference to striatal pathology. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(Suppl 3):S221–4. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(08)70005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klunk WE, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer's disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Compta Y, et al. Lewy- and Alzheimer-type pathologies in Parkinson's disease dementia: which is more important? Brain. 2011;134(Pt 5):1493–505. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalaitzakis ME, et al. Striatal beta-amyloid deposition in Parkinson disease with dementia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67(2):155–61. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31816362aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke JF, et al. Assessment of mild dementia with amyloid and dopamine terminal positron emission tomography. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 6):1647–57. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kantarci K, et al. Multimodality imaging characteristics of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(9):2091–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maetzler W, et al. Cortical PIB binding in Lewy body disease is associated with Alzheimer-like characteristics. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34(1):107–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster ER, et al. Amyloid imaging of Lewy body-associated disorders. Mov Disord. 2010;25(15):2516–23. doi: 10.1002/mds.23393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada H, et al. beta-Amyloid in Lewy body disease is related to Alzheimer's disease-like atrophy. Mov Disord. 2013;28(2):169–75. doi: 10.1002/mds.25286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomperts SN, et al. Brain amyloid and cognition in Lewy body diseases. Mov Disord. 2012;27(8):965–73. doi: 10.1002/mds.25048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomperts SN, et al. Amyloid is linked to cognitive decline in patients with Parkinson disease without dementia. Neurology. 2013;80(1):85–91. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827b1a07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe CC, et al. Imaging beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2007;68(20):1718–25. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261919.22630.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edison P, et al. Amyloid load in Parkinson's disease dementia and Lewy body dementia measured with [11C]PIB positron emission tomography. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(12):1331–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.127878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jokinen P, et al. [(11)C]PIB-, [(18)F]FDG-PET and MRI imaging in patients with Parkinson's disease with and without dementia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16(10):666–70. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrou M, et al. Abeta-amyloid deposition in patients with Parkinson disease at risk for development of dementia. Neurology. 2012;79(11):1161–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182698d4a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiting P, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes AJ, et al. A clinicopathologic study of 100 cases of Parkinson's disease. Arch Neurol. 1993;50(2):140–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540020018011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen JP, Dupont E, Tandberg E. Clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. Proposal of diagnostic subgroups classified at different levels of confidence. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;89(4):242–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV-TR. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. p. xii.p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khachaturian ZS. Diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 1985;42(11):1097–105. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060100083029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villemagne VL, et al. Amyloid imaging with (18)F-florbetaben in Alzheimer disease and other dementias. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(8):1210–7. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.089730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jack CR, Jr, et al. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):765–75. doi: 10.1002/ana.22628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolk DA, et al. Association between in vivo fluorine 18-labeled flutemetamol amyloid positron emission tomography imaging and in vivo cerebral cortical histopathology. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(11):1398–403. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sojkova J, et al. In vivo fibrillar beta-amyloid detected using [11C]PiB positron emission tomography and neuropathologic assessment in older adults. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):232–40. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mintun MA, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(3):446–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000228230.26044.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mielke MM, et al. Indicators of amyloid burden in a population-based study of cognitively normal elderly. Neurology. 2012;79(15):1570–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826e2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morris JC, et al. APOE predicts amyloid-beta but not tau Alzheimer pathology in cognitively normal aging. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(1):122–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowe CC, et al. Amyloid imaging results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(8):1275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleisher AS, et al. Florbetapir PET analysis of amyloid-beta deposition in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease kindred: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(12):1057–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jack CR, Jr, et al. Age-specific population frequencies of cerebral beta-amyloidosis and neurodegeneration among people with normal cognitive function aged 50-89 years: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(10):997–1005. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70194-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hely MA, et al. The Sydney multicenter study of Parkinson's disease: the inevitability of dementia at 20 years. Mov Disord. 2008;23(6):837–44. doi: 10.1002/mds.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cirrito JR, et al. Serotonin signaling is associated with lower amyloid-beta levels and plaques in transgenic mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(36):14968–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107411108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kotagal V, et al. Cerebral amyloid deposition and serotoninergic innervation in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(12):1628–31. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheinin NM, et al. Cortical 11C-PIB uptake is associated with age, APOE genotype, and gender in “healthy aging”. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(1):193–202. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.