Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association between living near dense traffic and lung function in a cohort of adults from a single urban region.

Design

Cross-sectional results from a cohort study.

Setting

The adult-onset asthma and exhaled nitric oxide (ADONIX) cohort, sampled during 2001–2008 in Gothenburg, Sweden. Exposure was expressed as the distance from participants’ residential address to the nearest road with dense traffic (>10 000 vehicles per day) or very dense traffic (>30 000 vehicles per day). The exposure categories were: low (>500 m; reference), medium (75–500 m) or high (<75 m).

Participants

The source population was a population-based cohort of adults (n=6153). The study population included 5441 participants of European descent with good quality spirometry and information about all outcomes and covariates.

Outcome measures

Forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) were measured at a clinical examination. The association with exposure was examined using linear regression adjusting for age, gender, body mass index, smoking status and education in all participants and stratified by sex, smoking status and respiratory health status.

Results

We identified a significant dose–response trend between exposure category and FEV1 (p=0.03) and borderline significant trend for FVC (p=0.06) after adjusting for covariates. High exposure was associated with lower FEV1 (−1.0%, 95% CI −2.5% to 0.5%) and lower FVC (−0.9%, 95% CI −2.2% to 0.4%). The effect appeared to be stronger in women. In highly exposed individuals with current asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, FVC was lower (−4.5%, 95% CI −8.8% to −0.1%).

Conclusions

High traffic exposure at the residential address was associated with lower than predicted FEV1 and FVC lung function compared with living further away in a large general population cohort. There were particular effects on women and individuals with obstructive disease.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

All participants underwent clinical examination and spirometry in a single clinical setting using standardised methods.

The study population was sampled from the general population with a wide age range in a single urban region.

Exposure categories were based on residence and traffic data.

Participation rates were not high; women and higher educated may be overrepresented.

Background

Vehicular traffic is a major contributor to air pollution in urban areas, and the emissions contain a plethora of substances, including nitrogen oxides and fine particles, which have acute negative effects on respiratory health.1 2 There is less evidence for the long-term effects of air pollution on respiratory health, including effects on lung function.3 Some studies have shown traffic-related air pollution associated with attenuated lung development in children, specifically forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) between ages 10 and 18,4 and modelled traffic exposure during the first year of life was associated with lower FEV1 at age 8.5

In adults, there are some studies showing that exposure to traffic pollution is related to reductions in lung function.6–10 However, none of the previous studies concern adults from a random population sample living within a single urban region.

In the earlier studies of long-term effects, crude exposure assessment with low spatial resolution contributed to exposure misclassification. Long-term individual exposure is influenced by a number of factors, including regional and nearby pollution sources,11 and is modified by individual factors, for example, occupational and lifestyle exposures.4

Geographic metrics are straightforward methods for classifying exposure as they increase the spatial resolution and reduce exposure misclassification compared to emission models or ground level measurements. The levels of pollutants from vehicle exhaust decay to near-background level as the distance to a road increases beyond some hundreds of metres from the site of generation.12 When studying a mixture of substances such as vehicle emissions, a general exposure indicator such as the distance to a large road may be more useful than models of specific pollutants, as this approach has been used in a number of studies.13–16

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between residential proximity to dense and very dense traffic and lung function in adults within a single coherent urban region, using cross-sectional data from a large population-based cohort.

Materials and methods

The study population was based on the adult-onset asthma and exhaled nitric oxide (ADONIX) cohort, which consists of a random sample of adults (25–75 years old) in Gothenburg. In total, 14 554 participants were invited to a clinical examination with spirometry, anthropometric measurements and a clinical examination. Information about age, respiratory health, residence, asthma status, smoking history and level of education was collected as described by Olin et al.17 Spirometry was performed with a dry wedge spirometer (Vitalograph; Buckingham, UK) except in 164 participants who were measured using EasyOne, and percentages of predicted values of lung function variables (FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC ratio) were calculated.18

Variable definitions

Age was reported in whole years, and body mass index (BMI) as kg/m2. Smoking was coded into three categories: never, former and current smokers, where former smokers were those who had stopped smoking at least a year ago. Obstructive lung disease was defined as reporting asthma in the previous 12 months, or fulfilling criteria for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as assessed from spirometry without a reversibility test according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease criteria19 in a regular spirometry test without reversibility testing. Education level was reported in one of six categories (primary, upper primary, vocational, high school, university equivalent or other) and used as an indicator of socioeconomic status.

Residential traffic exposure

Modelled values of NO2 and NOx were only available for some of the study participants (60% and 77%); instead, the distance from the participants’ home address to the nearest densely trafficked road was used as a measure of exposure to traffic pollution (the distance to road with 10 000 cars and modelled 2006 values of NO2 and NOx have a correlation coefficient of −0.57 and −0.53 respectively). All participants’ residential addresses at the time of examination were geocoded, and the distance from each address to the nearest road with more than 10 000 vehicles per day (‘dense traffic’) and more than 30 000 vehicles per day (‘very dense traffic’) as an annual average for the year 2004 was calculated by the Gothenburg municipality office.

The distances to the nearest road were coded into three categories: closer than 75 m (high exposure), between 75 and 500 m (medium exposure), and 500 m or more (low exposure). The cut-offs were chosen based on prior data regarding the dispersion of air pollutants after they are emitted from the source,12 that is, an almost exponential increase in the proximity of a road, as well as the distribution of the data and available literature.20–23 The study population was then classified into these three exposure categories in combination with the density of road traffic (either 10 000 or 30 000 vehicles per day). Analyses were performed separately for the two levels of traffic density.

Stratified analyses were performed for subgroups based on gender, smoking status and respiratory health status (healthy vs self-reported current asthma or COPD assessed from spirometry).

Statistical methods

After excluding participants with missing data, we explored the association between categories of exposure and FVC and FEV1, with linear regression using the low exposure category as reference. Initially, the outcomes were regressed on exposure and each potential confounding variable individually. Variables which were statistically significantly associated with at least one of the outcomes and also changed the estimated effect by 10% were included in the final models. For the main analysis, both unadjusted results and results adjusted for age, gender, BMI, education and smoking status are presented. The data were analysed stratified by gender, smoking status and respiratory health status. The percentage of lorry traffic was added to the model in a sensitivity analysis.

The results are reported as change in percent predicted FEV1 or FVC, with a 95% CI. We report p for trend, which was obtained through transforming the exposure categories to linear variables with values 0, 1 and 2 for each category, and including them in the same models instead of the category indicator variables. Results were considered statistically significant at the 0.05 level. R V.2.14.1 and STATA were used for all analyses.

Results

In total, 6686 participants were clinically examined once during 2001–2003 or 2005–2008, as previously described.18 The participation rate for the whole cohort was 46%. Of the total 6686 individuals in the cohort, 5441 participants (81%) lived within the greater Gothenburg area, had data available on all covariates, were of European descent and could be included in the analysis. The skewness of the distribution of % predicted FVC was −0.123, rather symmetric. The skewness of % predicted FEV1 was −0.483, within the range of being approximately symmetric.

In all, 363 participants were highly exposed to dense traffic (<75 m), 2668 had medium exposure (75–500 m) and 2410 had low exposure (>500 m). Demographic characteristics were similar among the participants regardless of exposure category, except for university education which was more common in the high exposure group (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants by dense traffic exposure category (distance to the nearest road with more than 10 000 vehicles per day).

| Dense traffic exposure |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (>500 m) | Medium (75–500 m) | High (<75 m) | |

| All participants (n=5441) | n=2410 | n=2668 | n=363 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age, years | 51.8 (11.0) | 51.5 (11.6) | 50.1 (12.4) |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 26.2 (4.0) | 26.0 (4.1) | 26.2 (4.5) |

| Lung function | |||

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 96.9 (13.8) | 96.2 (13.5) | 96.0 (13.6) |

| FVC (% predicted) | 98.5 (12.5) | 98.2 (12.2) | 97.7 (12.9) |

| Per cent | Per cent | Per cent | |

| Sex (% women) | 52.2 | 54.4 | 54.5 |

| Smoking history | |||

| Never smoked (n=2509) | 47.2 | 45.6 | 43.0 |

| Former smoker (n=2023) | 37.0 | 37.5 | 36.4 |

| Current smoker (n=909) | 15.9 | 16.9 | 20.7 |

| Highest formal education | |||

| Primary education (n=664) | 13.1 | 11.7 | 9.9 |

| Upper primary education (n=184) | 3.7 | 3.4 | 1.4 |

| Vocational school (n=404) | 7.6 | 7.5 | 5.5 |

| High school (n=1254) | 24.3 | 22.3 | 19.8 |

| University (n=2048) | 34.1 | 39.5 | 50.4 |

| Other education (n=887) | 17.1 | 15.5 | 15.7 |

| Obstructive pulmonary disease* (n=533) | 9.0 | 10.3 | 10.7 |

*Reported current asthma or fulfils criteria for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in regular spirometry test without reversibility testing.

BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

The crude effect estimate suggested a 1% reduction in predicted FEV1 and FVC among people living within 75 m of a densely trafficked road in comparison to those living more than 500 m away from a similar traffic flow (table 2). The associations followed a dose–response relationship with a near-significant trend for FEV1. In the adjusted analysis, the associations were strengthened with the medium exposure category estimate for FEV1 becoming statistically significant, and the dose–response trend significant for FEV1 and near-significant for FVC (table 2).

Table 2.

Lung function change in those exposed to dense traffic (>10 000 vehicles per day) versus reference (>500 m)

| Outcome | n | Unadjusted models | p for trend | Adjusted* models | p for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic exposure | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |||

| FEV1 | |||||

| >500 m | 2441 | – | – | ||

| 75–500 m | 2688 | −0.66 (−1.41 to 0.09) | −0.80 (−1.53 to −0.07) | ||

| <75 m | 367 | −0.93 (−2.44 to 0.57) | 0.065 | −1.01 (−2.47 to 0.45) | 0.027 |

| FVC | |||||

| >500 m | 2441 | – | – | ||

| 75–500 m | 2688 | −0.37 (−1.05 to 0.32) | −0.57 (−1.23 to 0.10) | ||

| <75 m | 367 | −0.80 (−2.16 to 0.58) | 0.167 | −0.91 (−2.24 to 0.42) | 0.058 |

*Adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, education and smoking status.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Among the covariates, current smoking, BMI, age and male gender were significantly associated with a lower percentage of predicted values for FEV1 and FVC. Former smoking was significantly associated with a lower FEV1. University education, however, was associated with a higher FEV1.

The estimated reduction in FEV1 associated with living close to a road with >30 000 vehicles per day was somewhat greater than for those living close to a road with >10 000 vehicles per day, and the dose–response trend was slightly stronger (table 3).

Table 3.

Lung function change in those exposed to dense traffic (>30 000 vehicles per day) versus reference (>500 m)

| Outcome | n | Unadjusted model | p for trend | Adjusted* model | p for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic exposure | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | |||

| FEV1 | |||||

| >500 m | 4382 | – | – | ||

| 75–500 m | 1020 | −0.87 (−1.80 to 0.06) | −1.06 (−1.97 to −0.16) | ||

| <75 m | 39 | −1.31 (−5.61 to 2.99) | 0.057 | −2.23 (−6.40 to 1.94) | 0.012 |

| FVC | |||||

| >500 m | 4382 | – | – | ||

| 75–500 m | 1020 | −0.86 (−1.705 to −0.01) | −1.11 (−1.94 to −0.39) | ||

| <75 m | 39 | 1.23 (−2.69 to 5.14) | 0.111 | 0.33 (−3.47 to 4.12) | 0.018 |

*Adjusted for age, gender, BMI, education and smoking status.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Adding the percentage of lorry (heavy) traffic to the model did not improve the fit, and neither was it a significant predictor (results not shown).

Stratifying the analysis by gender, we found that associations between exposure and predicted FEV1 and FVC were stronger in women, although this analysis had less statistical power. For FVC, there was a significant negative association for the medium exposure category and a significant dose–response trend; for FEV1, the dose–response trend did not reach statistical significance (table 4).

Table 4.

Lung function change in women and men exposed to dense traffic (>10 000 vehicles per day) versus reference (>500 m)

| Outcome | n | Women | p for trend | n | Men | p for trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traffic exposure | % (95% CI) | % (95% CI) | ||||

| FEV1 | ||||||

| >500 m | 1257 | – | 1153 | – | ||

| 75–500 m | 1451 | −0.82 (−1.83 to 0.19) | 1217 | −0.74 (−1.79 to −0.31) | ||

| <75 m | 198 | −1.21 (−3.23 to 0.80) | 0.083 | 165 | −0.85 (−2.98 to 1.28) | 0.169 |

| FVC | ||||||

| >500 m | 1257 | – | 1153 | – | ||

| 75–500 m | 1451 | −0.97 (−1.90 to −0.04) | 1217 | −0.09 (−1.03 to 0.86) | ||

| <75 m | 198 | −1.76 (−3.61 to 0.09) | 0.014 | 165 | 0.07 (−1.84 to 1.99) | 0.950 |

Estimates are adjusted for age, BMI, education and smoking status.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

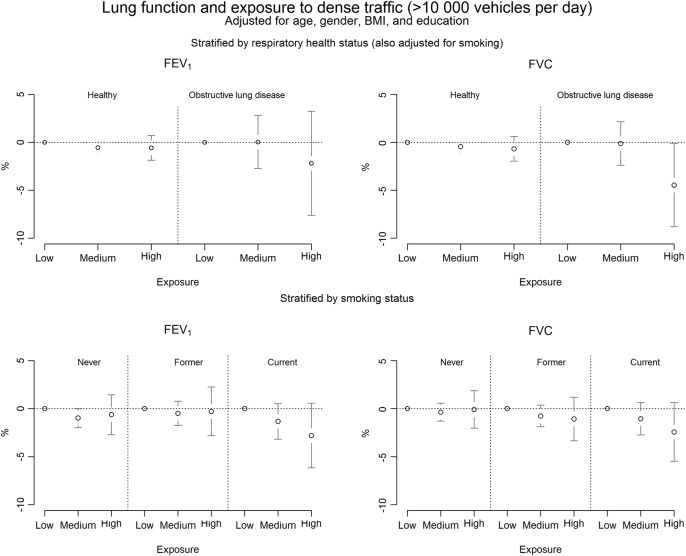

Stratifying the data by respiratory health status, we found that high exposure in individuals with obstructive lung disease was associated with significantly lower FVC (−4.5%, 95% CI −8.8% to −0.1%). FEV1 was also lower, but did not reach statistical significance (−2.2% (95% CI −7.6% to 3.2%) (figure 1 and online supplementary table S1). In current smokers with high exposure, FEV1 was lower (−2.8%, 95% CI −6.2% to 0.6%), but the result was not significant (figure 1 and online supplementary table S2).

Figure 1.

Lung function outcomes and exposure to dense traffic in healthy individuals and in individuals with obstructive pulmonary disease adjusted for age, gender, BMI and education (asthma and COPD) (top) and in never, former and current smokers (bottom). BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

In the sensitivity analysis, including the percentage of traffic larger than cars (highest percentage was 8) into the model did not improve the fit, and nor was it a significant predictor of lung function.

Discussion

In this study of adults from a single metropolitan area, we found an association between living close to densely trafficked roads and having a lower than predicted FEV1 and FVC. The associations were stronger after adjusting for covariates, and they followed a dose–response trend, indicating that high exposure to traffic was more detrimental than medium exposure. The estimated effects of living close to a road with very dense traffic flows (more than 30 000 vehicles per day) were generally higher, but less consistent, indicating that a dose response could be present, but that the relatively few people exposed to high levels of very dense traffic compromised the statistical power. Though we cannot exclude bias due to unmeasured factors, or the role of chance, the observed association was most likely due to traffic exposure from large roads near the residence. There were more current smokers in the high and medium exposure areas, but there were also more people with a university education. The adjusted analyses had more significant associations and yielded higher estimates and a higher explanatory power (R2 was <0.001 in the unadjusted models, and 0.064 in the adjusted models).

The effect sizes found in the current study are on par with those found in other studies. For example, Kan et al14 found that women living closer than 150 m from a road with 10 000 vehicles had, on average, a 15.7 mL lower FEV1 and 24.2 mL lower FVC than those living further away. Converting our results from percentage predicted to mL, women in our study with medium or high exposure had, on average, a 29.7 and 43.8 mL lower FEV1, and a 35.1 and 63.7 mL lower FVC, respectively. Forbes et al24 reported that a 10 µg/m3 increase in NO2 in the area was associated with a 22 mL reduction in mean FEV1 (0.7% of the population mean). In our study, 10 µg/m3 corresponds roughly to the difference between high and low exposure in our data, making the result similar to ours (table 2). In a cross-sectional study of the nationwide National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES, data collected between 1971 and 1975), decreases in FEV1 and FVC were found with increasing levels of modelled total suspended particulates at the participants’ residence.7 In a cross-sectional analysis of the Swiss Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults (SAPALDIA), community-level concentration of all pollution types was inversely associated with FVC, whereas a decrease in FEV1 was only associated with traffic pollutants.8 In a follow-up of the same cohort, declining particulate matter (PM10) exposure over 12 years was associated with less attenuated age-related deterioration in mean FEV1 compared to having more constant exposure.9 Other studies have found indications of susceptible groups when looking at modelled levels of ozone, and exposure to high levels of PM10 in relation to FEV1, showing only significant associations among men with a family history of respiratory disease.10 The association between exposure and decreases in FEV1 and FVC averages were stronger in women than in men. A possible explanation for this observation is that the exposure assessment based on residential address could be more accurate in women, as women tend to have lower labour market participation and are therefore more often at home.25 It could also be due to unmeasured confounders related to differences in occupational exposures and lifestyle factors. However, several studies suggest women to be more susceptible to adverse respiratory health effects (mortality, symptoms, lower FEV1 or FVC) from exposure to air pollution,3 or other exposures,26 although other studies found that men were more susceptible.10 24

Other studies have shown associations between traffic proximity and respiratory health. Living near a large road was associated with increased risk of developing asthma in a prospective cohort study.13 In a multicentre study, living near dense traffic was associated with a lower FEV1 and FVC in women, while in men only age-adjusted means of FEV1 were lowered to near significance.14 In a multicity study, women living near dense traffic had a lower mean FEV1 and FVC and increased risk of COPD.15 However, other studies found no associations between living near a road with dense traffic and FEV1 or other measures of respiratory morbidity.16 In individuals with obstructive lung disease, high exposure to dense traffic was associated with airway restriction, with a significantly lower FVC than for the low-exposed individuals in the same group. Interestingly, the effect estimate for medium exposure was very near the reference (figure 1). However, these results barely reached statistical significance, possibly due to the low number of participants in the highest exposed groups. The lower than predicted FVC indicates a restrictive effect on pulmonary function, which is more associated with obesity, systemic and metabolic morbidities and mortality,27 which is generally increased in COPD. In our analyses, we found that age was a negative predictor of lung function, although using a predicted value should have accounted for this. Other studies have found air pollution effects in elderly participants,24 and in the subgroup analysis we found that the association between age and lung function was only significant in those with obstructive lung disease. This finding supports that the observed association between age and age-adjusted lung function could be explained by age-related accumulation of comorbidities, which could also be associated with exposure to traffic pollution. A general deterioration in health could also increase susceptibility to exposure to air pollution, which could contribute to accelerated lung function decline. The composition of vehicles has been found to influence the impact of air pollution on respiratory health in children,28 and lorry traffic within 50 m has been shown to predict indoor air pollution,29 but estimates for this variable were near the null.

Our study has some limitations; we used distance to the nearest road to estimate traffic exposure at the current address, as modelled values of NO2 and NOx were only available for 73% of the study population. However, distance to road also has advantages as an exposure indicator for the complex traffic-related air pollution mix, and there is good correlation (Pearson) between the modelled values and the absolute distance to the nearest road with (correlation coefficient −0.51 for NO2, and −0.47 for NOx; p values >0.001). The cut-offs at 75 and 500 m from roads were selected based on previous studies about distribution of pollutants near large roads, but the literature holds a large span of options for cut-offs.7 14–16 The crude measure of distance to road is significantly associated with lung function in the adjusted models (not shown), but the resulting coefficients are very small. We had no information about how long the participants had lived at their current address. Older people tend to have lived longer in the same place,30 and exposure assessment based on the residence may also improve as people age and leave the workforce, as people spend more time in their homes. However, misclassifications of exposure are most likely to bias the results towards the null. The most relevant traffic data available (from 2004) predate the index date of some participants by as much as 3 years. However, comparing 2004 traffic data with 1997 traffic data, only 2.3% of participants changed exposure category. From 2004 to 2010, 3.1% of participants changed exposure category, a precision we consider acceptable and which is unlikely to bias our results appreciably. Education was used as a measure of socioeconomic status, but unfortunately no information about income or occupation was available, which could have improved the measure. Education is usually a better marker of socioeconomic status in men than in women.31

It is a strength of the study that data were collected at one centre, and the fact that the population came from a large cohort sampled from the same area increases the likelihood that the observed effects were due to the traffic exposure rather than regional confounding. However, the low participation rate is a concern. A non-participation analysis of the data gathered in 2001–2003 showed that women, the elderly and the university educated were more likely to participate.32 If non-participation was selective in such a way that those who live close to the main traffic areas and also suffer from a respiratory illness were more likely to participate, our effect estimates could be exaggerated. However, the social stratification of the cohort is expected and is particular to this area, where the high exposed study group had the highest proportion of highly educated people, opposite to many other urban areas. Most results adhere to a dose–response pattern showing increasing effects with increasing exposure which further indicates that differences were related by the exposure rather than bias from exposure to other unmeasured confounders.

In conclusion, in this study of a large cohort in a single metropolitan area, high residential exposure to dense traffic was associated with reductions in percentage of the predicted FEV1 and FVC. In those with obstructive lung diseases, the association of FVC with high exposure was particularly strong. This is potentially an important finding, but it should be verified in other studies before being incorporated into official advice for this patient group.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Wass for help with the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: HKC was involved in statistical analyses, interpretation of the results and drafting of the article; FN and A-CO was involved in development of the research questions, designed and coordinated the study, interpretation of results and preparation of the manuscript; KT and AL was involved in interpretation of results and preparation of the manuscript; J-LK was involved in statistical assistance and data preparation, interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript; LM was involved in development of the research questions, interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS), grants 2001–0263, 2003–0139, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation grant 20050561 and the Swedish Research Council Formas (grant 2008–1203).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Västra Götaland Region ethical review board

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data from the ADONIX study exist and are held by the communicating author.

References

- 1.Dominici F, Peng RD, Bell ML et al. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA 2006;295:1127–34. 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trenga CA, Sullivan JH, Schildcrout JS et al. Effect of particulate air pollution on lung function in adult and pediatric subjects in a Seattle panel study. Chest 2006;129:1614–22. 10.1378/chest.129.6.1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clougherty JE. A growing role for gender analysis in air pollution epidemiology. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:167–76. 10.1289/ehp.0900994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gauderman WJ, Vora H, McConnell R et al. Effect of exposure to traffic on lung development from 10 to 18 years of age: a cohort study. Lancet 2007;369:571–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60037-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz ES, Gruzieva O, Bellander T et al. Traffic-related air pollution and lung function in children at 8 years of age: a birth cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:1286–91. 10.1164/rccm.201206-1045OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Götschi T, Heinrich J, Sunyer J et al. Long-term effects of ambient air pollution on lung function: a review. Epidemiology 2008;19:690–701. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318181650f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chestnut LG, Schwartz J, Savitz DA et al. Pulmonary function and ambient particulate matter: epidemiological evidence from NHANES I. Arch Environ Health J 1991;46:135–44. 10.1080/00039896.1991.9937440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ackermann-Liebrich U, Leuenberger P, Schwartz J et al. Lung function and long term exposure to air pollutants in Switzerland. Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults (SAPALDIA) Team. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:122–9. 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downs SH, Schindler C, Liu L-JS et al. Reduced exposure to PM10 and attenuated age-related decline in lung function. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2338–47. 10.1056/NEJMoa073625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbey DE, Burchette RJ, Knutsen SF et al. Long-term particulate and other air pollutants and lung function in nonsmokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:289–98. 10.1164/ajrccm.158.1.9710101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Künzli N. Effects of near-road and regional air pollution: the challenge of separation. Thorax 2014;69:503–4. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO regional office for Europe. Review of evidence on health aspects of air pollution—REVIHAAP Project Technical Report. Copenhagen: WHO, 2013:67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Modig L, Torén K, Janson C et al. Vehicle exhaust outside the home and onset of asthma among adults. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1261–7. 10.1183/09031936.00101108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kan H, Heiss G, Rose KM et al. Traffic exposure and lung function in adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Thorax 2007;62:873–9. 10.1136/thx.2006.073015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schikowski T, Sugiri D, Ranft U et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and living close to busy roads are associated with COPD in women. Respir Res 2005;6:152 10.1186/1465-9921-6-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pujades-Rodríguez M, Lewis S, Mckeever T et al. Effect of living close to a main road on asthma, allergy, lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:679–84. 10.1136/oem.2008.043885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olin A-C, Rosengren A, Thelle DS et al. Height, age, and atopy are associated with fraction of exhaled nitric oxide in a large adult general population sample. Chest 2006;130:1319–25. 10.1378/chest.130.5.1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brisman J, Kim J-L, Olin A-C et al. A physiologically based model for spirometric reference equations in adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2014. Published Online First: 1 Oct 2004. 10.1111/cpf.12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.2010. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. GOLD—Spirometry Guide [Internet]. [cited 25 November 2013] http://www.goldcopd.org/other-resources-gold-spirometry-guide.html.

- 20.Heinrich J, Thiering E, Rzehak P et al. Long-term exposure to NO2 and PM10 and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a prospective cohort of women. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:179–86. 10.1136/oemed-2012-100876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose N, Cowie C, Gillett R et al. Weighted road density: a simple way of assigning traffic-related air pollution exposure. Atmos Environ 2009;43:5009–14. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2009.06.049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franklin M, Vora H, Avol E et al. Predictors of intra-community variation in air quality. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012;22:135–47. 10.1038/jes.2011.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pleijel H, Pihl Karlsson G, Binsell Gerdin E. On the logarithmic relationship between NO2 concentration and the distance from a highroad. Sci Total Environ 2004;332:261–4. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forbes LJL, Kapetanakis V, Rudnicka AR et al. Chronic exposure to outdoor air pollution and lung function in adults. Thorax 2009;64:657–63. 10.1136/thx.2008.109389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statistics Sweden. Women and men in Sweden—Facts and figures 2014. Stockholm, Sweden: Statistics Sweden; 2014; p. 104, Report No.: 13. http://www.scb.se/Statistik/_Publikationer/LE0201_2013B14_BR_X10BR1401ENG.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prescott E, Bjerg AM, Andersen PK et al. Gender difference in smoking effects on lung function and risk of hospitalization for COPD: results from a Danish longitudinal population study. Eur Respir J 1997;10:822–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Venker C et al. Morbidity and mortality associated with the restrictive spirometric pattern: a longitudinal study. Thorax 2010;65:499–504. 10.1136/thx.2009.126052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunekreef B, Stewart AW, Anderson HR et al. Self-reported truck traffic on the street of residence and symptoms of asthma and allergic disease: a global relationship in ISAAC phase 3. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:1791–8. 10.1289/ehp.0800467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baxter LK, Clougherty JE, Paciorek CJ et al. Predicting residential indoor concentrations of nitrogen dioxide, fine particulate matter, and elemental carbon using questionnaire and geographic information system based data. Atmos Environ 2007;41:6561–71. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Statistics Sweden. [Swedes move on average 11 times]. Statistiska centralbyrån Nr. 2012:96 [Internet]. Statistics Sweden. [cited 24 July 2013] 2012. http://www.scb.se/sv_/Hitta-statistik/Artiklar/Svensken-flyttar-i-snitt-elva-ganger/

- 31.Prescott E, Vestbo J. Socioeconomic status and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:737–41. 10.1136/thx.54.8.737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strandhagen E, Berg C, Lissner L et al. Selection bias in a population survey with registry linkage: potential effect on socioeconomic gradient in cardiovascular risk. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:163–72. 10.1007/s10654-010-9427-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]