Abstract

The discovery of the B-form structure of DNA by Watson and Crick led to an explosion of research on nucleic acids in the fields of biochemistry, biophysics, and genetics. Powerful techniques were developed to reveal a myriad of different structural conformations that change B-DNA as it is transcribed, replicated, and recombined and as sister chromosomes are moved into new daughter cell compartments during cell division. This article links the original discoveries of superhelical structure and molecular topology to non-B form DNA structure and contemporary biochemical and biophysical techniques. The emphasis is on the power of plasmids for studying DNA structure and function. The conditions that trigger the formation of alternative DNA structures such as left-handed Z-DNA, inter- and intra-molecular triplexes, triple-stranded DNA, and linked catenanes and hemicatenanes are explained. The DNA dynamics and topological issues are detailed for stalled replication forks and for torsional and structural changes on DNA in front of and behind a transcription complex and a replisome. The complex and interconnected roles of topoisomerases and abundant small nucleoid association proteins are explained. And methods are described for comparing in vivo and in vitro reactions to probe and understand the temporal pathways of DNA and chromosome chemistry that occur inside living cells.

DNA topology is a critical factor in essentially all in vivo chromosomal processes, including DNA replication, RNA transcription, homologous recombination, site-specific recombination, DNA repair, and integration of the abundant and mechanistically distinct forms of transposable elements. Plasmids can be invaluable tools to define the dynamic mechanisms of proteins that shape DNA, organize chromosome structure, and channel chromosome movement inside living cells. The advantages of plasmids include their ease of isolation and the ability to quantitatively measure DNA knots, DNA catenation, hemicatenation between two DNA molecules, and positive or negative supercoils in purified DNA populations. Under ideal conditions, in vitro and in vivo results can be compared to define the complex mechanism of enzymes that move along and change DNA chemistry in living cells. Many techniques that can be easily done with plasmids are not feasible for the massive chromosome that carries most of the genetic information in Escherichia coli or Salmonella typhimurium. Whereas a large fraction of contemporary chromosomal “philosophy” is based on extrapolation of results from small plasmids such as pBR322 to the 4.6-Mb bacterial chromosome, the comparison is not always valid. One aim of this article is to explain how results derived from small plasmids can be misleading for understanding and interpreting the DNA structure of the large bacterial chromosome.

TOPOLOGY OF CIRCULAR DNA

Three levels of discrimination are needed to specify the topological state of double-stranded circular DNA. For the first and second levels one considers DNA as a simple curve that coincides with the DNA axis. The fist level describes the topology of an isolated closed curve that corresponds to an unknotted circle or to a knot of a particular type. If we have many DNA molecules, part of them can form topological links with others, and the second level specifies types of these links. An infinite number of different types of knots and links exist. Some simple examples are shown in Fig. 1. The third level of the description specifies links formed by complementary strands of the double helix. This component of DNA topology will be a major subject in this review.

FIGURE 1.

The simplest knots (a) and catenanes (b). DNA molecules are capable of adopting these and many more complex topological states. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f1

Supercoiling, Linking Number, and Linking Number Difference

In the initial studies of plasmid DNA structure, two predominant types of circular DNA molecules were isolated from cells. These types were designated as form I and form II. The more compact form I turned into form II when a single-stranded break was introduced into one chain of the double helix. Studies by Vinograd (1) connected the compactness of form I to negative super-coiling. Form I is also called the closed circular form since each strand that makes up the DNA molecule is closed on itself. A diagrammatic view of a model of closed circular DNA is presented in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of closed circular DNA. The linking number, Lk, of the complementary strands is 18. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f2

The strands of the double helix in closed circular DNA are linked. The quantitative description of this characteristic is called the linking number (Lk), which may be determined in the following way. One of the strands defines the edge of an imaginary surface (any such surface gives the same result). Lk is the algebraic (i.e., sign-dependent) number of intersections between the other strand and this spanning surface. By convention, the Lk of a closed circular DNA formed by a right-handed double helix is positive. Lk depends only on the topological state of the strands and hence is maintained through all conformational changes that occur in the absence of strand breakage.

Quantitatively, the linking number is close to N/γ, where N is the number of base pairs in the molecule and γ is the number of base pairs per double-helix turn in linear DNA under given conditions. However, these values are not equal, and the difference between Lk and N/γ (which is also denoted as Lk0) defines most of the properties of closed circular DNA. A parameter that specifies this difference is called the linking number difference, ΔLk, and is defined as

| ð1Þ |

There are two inferences to be made from the above definition.

The value of ΔLk is not invariant; it depends on solution conditions that determine γ. Even though γ itself changes only slightly according to variable ambient conditions of temperature and ionic strength, such changes can substantially alter ΔLk because the right-hand part of equation 1 is a difference between two large quantities.

The value of LK is by definition an integer, whereas N/γ is not an integer. Hence ΔLk is not an integer either. However, the values of ΔLk for a closed circular DNA with a particular sequence can differ by an integer only. This follows from the fact that, whatever the prescribed conditions, all changes in ΔLk can only be due to changes in Lk, since the value of N/γ is the same for all molecules. (Of course, any change of Lk would involve a temporary violation of the integrity of a double-helix strand.) Molecules with the same chemical structure that differ only with respect to Lk are defined as topoisomers.

It is convenient to use the value of superhelical density, σ, which is ΔLk normalized for Lk0:

| ð2Þ |

Whenever ΔLk ≠ 0, closed circular DNA is said to be supercoiled. Clearly, the entire double helix is stressed in a supercoiled condition. This stress can either lead to a change in the actual number of base pairs per helix turn in closed circular DNA or cause regular spatial deformation of the helix axis. The axis of the double helix then forms a helix of a higher order (Fig. 3). It is this deformation of the helix axis in closed circular DNA that gave rise to the term “superhelicity” or “super-coiling” (1). Circular DNA extracted from cells turns out to be always (or nearly always) negatively super-coiled and has a σ between −0.03 and −0.09, but typically is near the middle of this range (2).

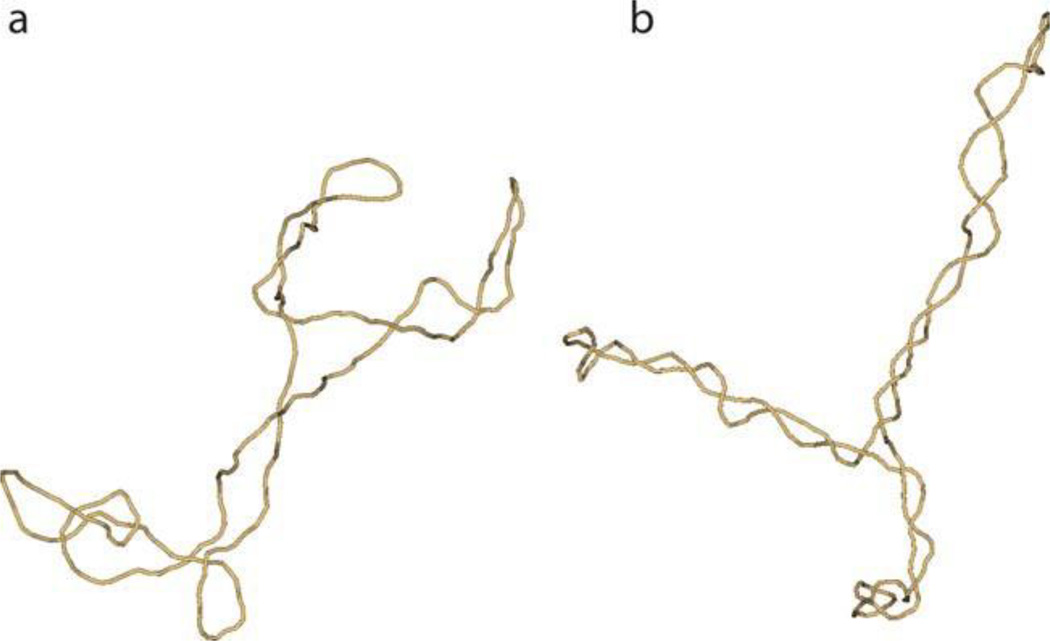

FIGURE 3.

Typical simulated conformations of supercoiled DNA 4.4 kb in length. The conformations correspond to a DNA superhelix density of (a) −0.030 and (b) −0.060. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f3

Twist and Writhe

Supercoiling can be created in two ways: by deforming the molecular axis or by altering the twist of the double helix. This can be demonstrated in a simple experiment involving a rubber hose or flexible tubing. Take a length of hose and connect the ends by inserting a short rod into each end to join the ends of the hose; this is equivalent to a relaxed form of DNA. If one turns the hose several times around the rod axis, the hose will change into a helical band. By drawing longitudinal stripes on the hose prior to the experiment, one can see that reciprocal twisting of the ends causes torsional deformation of the hose. There is a quantitative relationship between the twist around the DNA axis and its deformation and Lk of the complementary strands of the double helix. The first mathematical treatment of the problem was presented by Calugareanu (3), who described the geometrical and topological properties of a closed ribbon. White (4) proved the theorem in its current form. Later, Fuller showed that the theorem applies to the analysis of circular DNA (5).

According to the theorem, the Lk of the edges of the ribbon is the sum of two values. One is the twist of the ribbon, Tw, and the second was a new concept, writhe Wr. Thus,

| ð3Þ |

Tw is a measure of the number of times one of the edges of the ribbon spins about its axis. The Tw of the entire ribbon is the sum of the Tw of its parts. The value of Wr is defined by the spatial course of the ribbon axis; i.e., it is a characteristic of a single closed curve, unlike Lk and Tw, which are properties of a closed ribbon. Thus, Lk can be represented as a sum of two values that characterize the available degrees of freedom: the twist around the ribbon axis and the deformation of this axis. To apply the theorem to circular DNA, the two strands of the double helix are considered as edges of a ribbon. Wr describes a curve’s net right-handed or left-handed asymmetry, i.e., its chirality, and is equal to zero for a planar curve (5). Unlike Lk, which can only be an integer, a curve’s Wr can have any value. This value changes continuously with the curve’s deformation that does not involve the intersection of segments. A curve’s Wr does not change with a change in the curve’s scale and depends solely on its shape. However, when a curve is deformed so that one of its parts passes through another, the writhe changes by 2 (or −2 for the opposite direction of the pass) (5). This property helped reveal the reaction mechanism of DNA gyrase (6).

Measuring Conformations of Supercoiled DNA

The critical result of the theory is that Lk can be structurally distributed in two ways: as a torsional deformation of the double helix and as a deformation of the DNA axis. Equation 3 states that any change in the twist of the double helix results in deformation of the helix axis, giving rise to a specific writhe. As the first to make a theoretical analysis of the shape of supercoiled DNA, Fuller (5) concluded that an interwound superhelix was favored over a simple solenoid superhelix from an energetic point of view. All available experimental and theoretical data indicate that supercoiled DNA adopts interwound conformations (7).

Electron microscopy (EM) is the most straightforward way to study conformations of supercoiled DNA. This method has been used extensively since the discovery of DNA supercoiling (1). The compact inter-wound supercoiled DNA form has been confirmed in numerous EM studies (8–10). It became clear, however, that labile DNA conformations can change during sample preparation for EM (7). A serious problem for interpreting EM results is the unspecified ionic conditions on the grid (11). Independent solution studies were required to confirm conclusions about these flexible objects (9, 12, 13).

Experimental solution methods, such as hydrodynamic and optical measurements, do not give direct, model-independent information about the three-dimensional structure of supercoiled DNA. These methods do, however, measure structure-dependent features of supercoiled DNA in a well-defined solution. Solution methods combined with computer simulation of supercoiled molecules were very productive in supercoiling studies (14, 15). The strategy involves calculating measurable properties of supercoiled DNA using a model of the double helix and comparing simulated results with experimental data. Simulated and actual conformations were in excellent agreement. Thus, computations can predict properties of the supercoiled molecules that are hard to measure directly. Fig. 3 shows simulated conformations of supercoiled molecules for two different values of σ: −0.03, which is close to the physiological level of unrestrained supercoiling (see below), and −0.06, which is close to the shape of plasmid DNAs stripped of all bound proteins. For DNA molecules with more than 2,500 base pairs, both computational and experimental data indicate that in “physiological” ionic conditions about three fourths of ΔLk is realized as bending deformation (Wr) and one fourth is realized as torsional deformation (Tw) (7).

Electrophoretic Separation of DNA Molecules with Different Topology

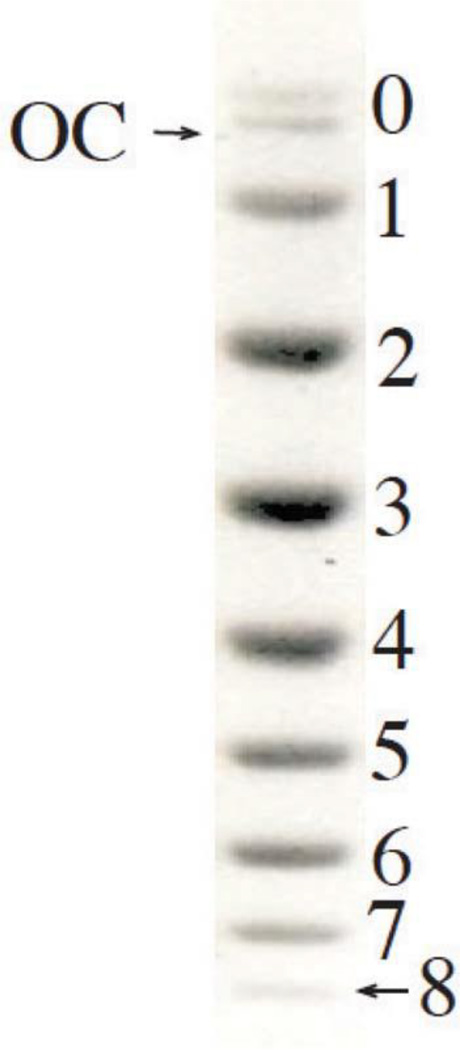

DNA molecules of a few thousand base pairs in length adopt many conformations in solution. However, exchange between conformations occurs in milliseconds, and during gel electrophoresis one observes the average mobility of any molecule. These average values depend on the topology of circular DNA, and thus a mixture of molecules with different Lk can be separated by gel electrophoresis. Such separations proved to be very powerful in studying DNA properties. Keller (16) was the first to separate topoisomers with different values of ΔLk in closed circular DNA. Since the values of ΔLk in any mixture of DNA topoisomers can differ only by an integer, under appropriate experimental conditions, molecules with different ΔLk form separate bands in the electrophoretic pattern (Fig. 4). If a DNA sample contains all possible topoisomers with ΔLk from 0 to some limiting value, and they are all well resolved with respect to mobility, one can find the value of ΔLk corresponding to each band simply by band counting. The band that corresponds to ΔLk ≈ 0 (ΔLk is not an integer) can be identified through a comparison with the band for the nicked circular form. One should bear in mind the fact that topoisomer mobility is determined by the absolute value of ΔLk only, so the presence of topoisomers with both negative and positive ΔLk can make interpreting the electrophoresis profile difficult. Also, the mobility of topoisomers approaches a limiting value when |ΔLk| increases, so a special method is required to separate topoisomers beyond this limit of resolution (16).

FIGURE 4.

Electrophoretic separation of topoisomers of pUC19 DNA. The mixture of topoisomers covering the range of ΔLk from 0 to −8 was electrophoresed from a single well in 1% agarose that was run from top to bottom. The topoisomer with ΔLk = 0 has the lowest mobility: it moves slightly slower than the open circular form (OC). The value of (−ΔLk) for each topoisomer is shown. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f4

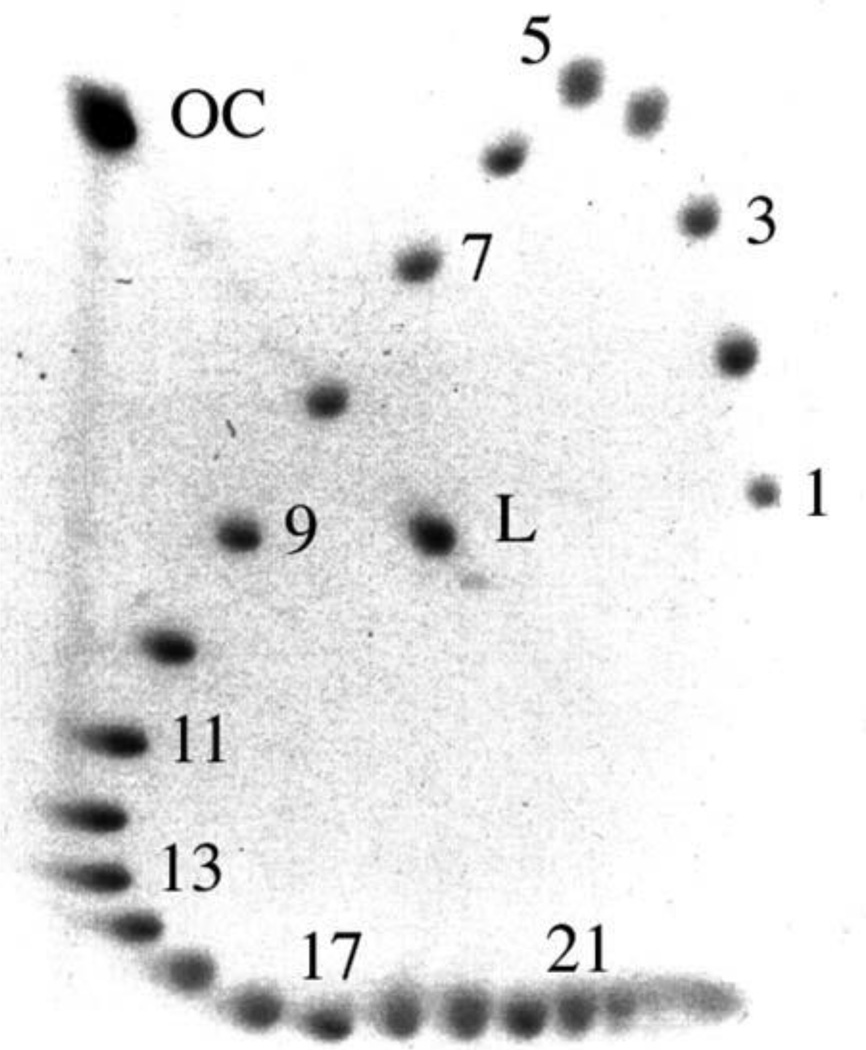

An elegant way to overcome the shortcoming of one-dimensional analysis is two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (17). A mixture of DNA topoisomers is loaded into a well at the top-left corner of a slab gel and electrophoresed along the left side of the gel. The bands corresponding to topoisomers with large ΔLk values merge into one spot. Then the gel is transferred to a buffer containing the intercalating ligand chloroquine and electrophoresed in the second horizontal direction (Fig. 5). This effectively shifts the value of ΔLk by a significant positive increment. As a result, the topoisomers with opposite values of ΔLk are well separated by the electrophoresis in the second direction. Also, the topoisomers with large negative ΔLk, which had identical mobility in the first direction, move with lower but different speed in the second direction. The number of topoisomers that can be resolved almost doubles in two-dimensional electrophoresis. See references 18 and 19 for applications of the electrophoretic separations of topoisomers.

FIGURE 5.

Separation of pUC19 DNA topoisomers by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Topoisomers 1 to 4 are positively supercoiled; the rest have negative supercoiling. After electrophoresis in the first direction, from top to bottom, the gel was saturated with ligand intercalating into the double helix. Upon electrophoresis from left to right in the second direction, the 2nd and 13th topoisomers turned out to migrate near the relaxed position in the second dimension. The spot in the top-left corner corresponds to the open circular form (OC); the spot near the middle of the gel corresponds to linear DNA (L). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f5

Knots and links of different types formed by circular DNA molecules can also be separated by electrophoresis (Fig. 6). The method requires special calibration, because it is impossible to say in advance what position a particular topological structure must occupy relative to the unknotted circular DNA form. A large body of experimental results on the mobility of various topological structures has been accumulated (20, 21). To separate knotted and linked molecules by gel electrophoresis, the DNAs must have single-strand breaks, because otherwise mobility will also depend on the linking number of the complementary strands.

FIGURE 6.

High-resolution gel electrophoresis of knotted forms of plasmid DNA that was run from left to right. Knot types are described in Fig. 1 (see reference 21). Reproduced from the Journal of Molecular Biology with permission from Elsevier. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f6

ENZYMES OF DNA TOPOLOGY

In enteric bacteria, four distinct topoisomerases are able to change the linking status of plasmid DNA molecules. When a DNA molecule is isolated from the cell, it is frozen in a particular topological state. However, plasmid populations exist in dynamic equilibrium inside the cell, and they can rapidly change topological structure (22). The known enzymes (DNA topoisomerases) that alter linking number include Topo I, DNA gyrase, Topo III, and Topo IV. DNA gyrase and Topo IV are related enzymes that break both strands of DNA simultaneously and are classified as type II enzymes. Topo I and Topo III are type I enzymes that break one strand at a time.

Topo I (also called ω protein) removes negative supercoils from covalently closed DNA and is an essential enzyme in E. coli (23, 24). Topo I conserves the energy of the DNA phosphodiester bond during the strand passage in a covalent phosphotyrosine linkage (25). The conserved tyrosine residue and the phosphotyrosine intermediate are also found in Topo III and both type II topoisomerases, with the essential tyrosine being on the GyrA subunit of gyrase and the ParC subunit of Topo IV. This mechanism of breaking and rejoining DNA strands is also found in many site-specific recombinases, which use either tyrosine or serine as a high-energy phosphoprotein link to DNA. Many enzymes including Hin, Gin, Tn3 Res, and XerC/D function as site-specific topoisomerases when a plasmid contains their cognate DNA recombination sequences (26–29).

DNA gyrase (Topo II) is a tetrameric protein made up of two GyrA and two GyrB subunits (30, 31). Gyrase is unique among all known topoisomerases for its ability to utilize the energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis to introduce negative supercoils into relaxed covalently closed DNA. The ATP binding domain is contained within the GyrB protein, and the drug novobiocin acts as a competitive inhibitor of ATP binding. Most of the DNA-binding site is formed by the GyrA subunit, and the potent antibiotics nalidixic acid and related fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin stabilize the covalent enzyme-DNA intermediate (30, 32). Such stabilized complexes lead to DNA breakage by either denaturation or by interactions with DNA replication machinery (33).

Topo III, the second type I enzyme discovered in E. coli, is not essential for cell viability, although it has important roles in normal DNA replication (34). Topo III can decatenate plasmids in the act of replication, and this enzyme requires a single-stranded region for it to separate replicating molecules. Topo III mutants accumulate small chromosomal deletions at positions where short repeats occur along the DNA sequence (35). This enzyme is conserved in eukaryotes, and a similar deletion phenotype is observed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (36, 37). The discontinuously synthesized strand may provide the single-stranded substrate that is required for Topo III to function as a decatenase, and the enzyme can also disentangle hemicatenanes (see below).

Topo IV was the third topoisomerase found to be essential for cell viability in E. coli and S. typhimurium (38, 39). Topo IV is closely related to gyrase in subunit structure and catalytic mechanism. Topo IV controls the segregation of bacterial plasmids and the bacterial chromosome at the end of replication by completely unlinking and unknotting the replication products. Topo IV is a heteromeric tetramer made up of two ParE proteins, which have an ATP binding site, and two ParC subunits, which fashion most of the DNA binding site and include the essential tyrosine. Like gyrase, Topo IV is inhibited by both novobiocin and by fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Topo IV requires ATP to catalyze all strand-passing reactions, and it removes positive supercoils at a much higher rate than negative ones (40). Mutant strains have been constructed that allow the selective inhibition of either gyrase or Topo IV (41, 42). Topo IV provides the primary unknotting activity of the cell, as well as being the major decatenase, which explains its essential nature.

DYNAMIC TOPOLOGICAL EQUILIBRIUM

In vivo, the average value of σ has been determined for a relatively small number of large and small plasmids using a gel electrophoretic technique. Whereas results vary with growth conditions and genetic background (see Table 1) (43, 44), σ in actively growing wild type (WT) cells falls within a relatively narrow range of values from −0.05 to −0.07. In vitro, DNA gyrase can supercoil a small circular plasmid up to a much higher level of σ of −0.10. What controls gyrase-driven supercoiling inside cells?

TABLE 1.

Constrained and unconstrained supercoiling in E. coli K12-derived strainsa

|

E. coli Strain |

Relevant mutations |

−σ (Total) | −σD | −σC | % −σD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB 101 | WT | 0.065 | 0.024 | 0.041 | 37 |

| JTT1 | WT | 0.056 | 0.024 | 0.032 | 43 |

| RS2 | top10 | 0.072 | 0.030 | 0.042 | 42 |

| SD-7 | top10 gyrB | 0.052 | 0.021 | 0.031 | 39 |

Data from Jaworski et al. (86).

The homeostatic supercoiling model of Menzel and Gellert (45) was developed to explain how bacteria maintain a relatively constant supercoiling level over a broad range of physiological conditions. This model was inspired by observing that transcriptional regulation of Topo I and gyrase responds to negative super-coiling in reciprocal ways. Expression of gyrB and gyrA genes increases when chromosomal DNA loses negative supercoiling. One example is a culture of bacterial cells treated with novobiocin, a compound that inhibits the binding of ATP to the GyrB subunit. Such cells increase expression of both gyrase subunits. Conversely, expression of the topA gene, which encodes Topo I, increases under conditions of elevated supercoiling. The homeostatic model posits that this expression pattern, combined with the opposing catalytic activities of the two enzymes, leads to an equilibrium where gyrase-induced negative supercoiling is balanced by Topo I-driven relaxation of negative supercoils. Important to the model is the fact that Topo I only removes super-coils from molecules with high levels of negative super-coiling, due to its requirement for an unpaired region of DNA, which is promoted by negative supercoiling.

The Sternglanz lab generated an isogenic set of three E. coli strains that illustrate a basic pattern (23). Strain JTT1, with a full complement of WT topoisomerases, produces plasmids with an average σ of −0.056 (Table 1). Strain RS2 carries the top10 allele, which makes a defective TopA protein and has increased plasmid supercoiling of σ equal to −0.072. Strain SD-7 is a double mutant with the top10 mutation plus a gyrB266 mutation, and its plasmids have an average σ of −0.052. The discovery of Topo III and Topo IV revealed that topological equilibrium is actually more complex than the Menzel and Gellert model predicted. Tests of all four enzymes indicate that Topo III does not normally contribute to the in vivo topology of plasmid DNA (46, 47), but Topo IV does (46, 48). However, overexpression of Topo III can suppress mutations in Topo I (49), so Topo III levels may determine how significantly it contributes to topological balance. Topo IV can remove negative supercoils from plasmid DNA in vivo, and topological balance inside living cells involves at least DNA gyrase, Topo I, and Topo IV (46–48). Both gyrase and Topo IV require ATP for their reactions, and they are influenced by the cellular ATP/ADP ratios (50, 51).

Whereas this homeostatic control model has been shown to work for many species of bacteria, experiments designed to modulate protein levels in vivo have shown that the average supercoiling level is not very sensitive to changes in the abundance of Topo I or gyrase. For example, increasing or decreasing E. coli Topo I or gyrase by 10% changes the average supercoil density by only 1.5% (52), which is below the detection limit of many techniques. Since there are 500 molecules of gyrase per cell, changing the protein concentration by 30 to 40% takes time, and when cells are shifted to new growth conditions, supercoiling is altered significantly within a minute or two. Why does supercoil density change rapidly?

In 1987, Liu and Wang (53) proposed a model for RNA transcription in which the DNA rotates around its axis during transcription rather than polymerases rotating around the flexible DNA template. Their model anticipated that this would create twin domains in which (−) supercoiling of DNA occurs upstream of the promoter, and (+) supercoiling is generated downstream from the transcription terminator. The twin domain effect was confirmed in E. coli using plasmids (54) and was confirmed in the bacterial chromosome of WT strains of Salmonella by measuring the supercoil density upstream and downstream of the highly transcribed rrnG ribosomal operon (55). In addition to causing a supercoil differential on opposing sides of highly transcribed genes, RNA polymerase creates a barrier to supercoil diffusion in the chromosome across the transcribed track (55–57). Mutant studies revealed that WT Topo I and gyrase both turn over processively at rates of 5 supercoils/sec at 30°, which is tuned to a rate of RNA polymerase elongation (50 nucleotides/sec at 30°) for E. coli and Salmonella (48). Moreover, growth rates, transcription rates, and average supercoil density levels vary significantly among different species of bacteria (48, 58–60).

SUPERCOIL-SENSITIVE DNA STRUCTURE

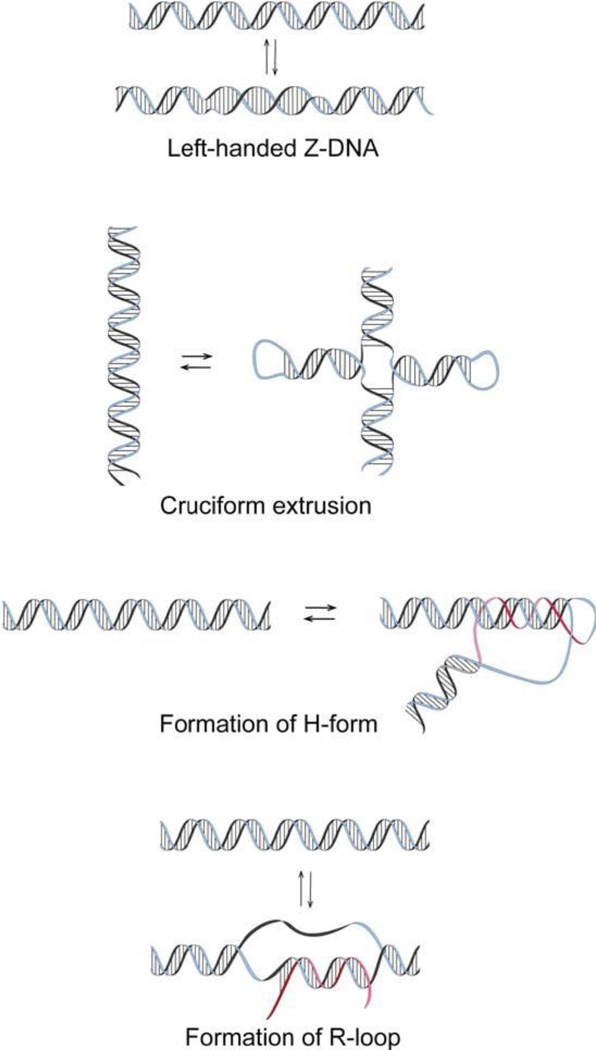

Negative supercoiling is associated with significant free energy that is stored in DNA. Negative supercoiling influences DNA structure, and like a spring, the free energy of supercoiling increases as a square of superhelix density (7, 61). Several unusual DNA conformations can be stabilized with negative supercoiling; well-characterized examples include left-handed Z-DNA, cruciforms, intramolecular triplexes or H-form DNA, and intermolecular triplexes or R-loops (Fig. 7). Each of these four alternative DNA conformations has a specific sequence requirement. Z-DNA is perhaps the best-characterized alternative DNA structure. Sequences adopting the left-handed conformation usually involve simple dinucleotide repeats of either dC-dG, or dT-dG. The equilibrium between right- and left-handed conformations depends on two things: (i) the level of negative superhelicity and (ii) the dCG or dTG repeat length. The longer the repeat length, the lower the supercoiling energy necessary to stabilize the left-handed conformation in plasmid DNA. A general quantitative description of the Z form formation in DNA has been obtained (62).

FIGURE 7.

Alternative DNA structures that are stabilized by negative supercoiling. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f7

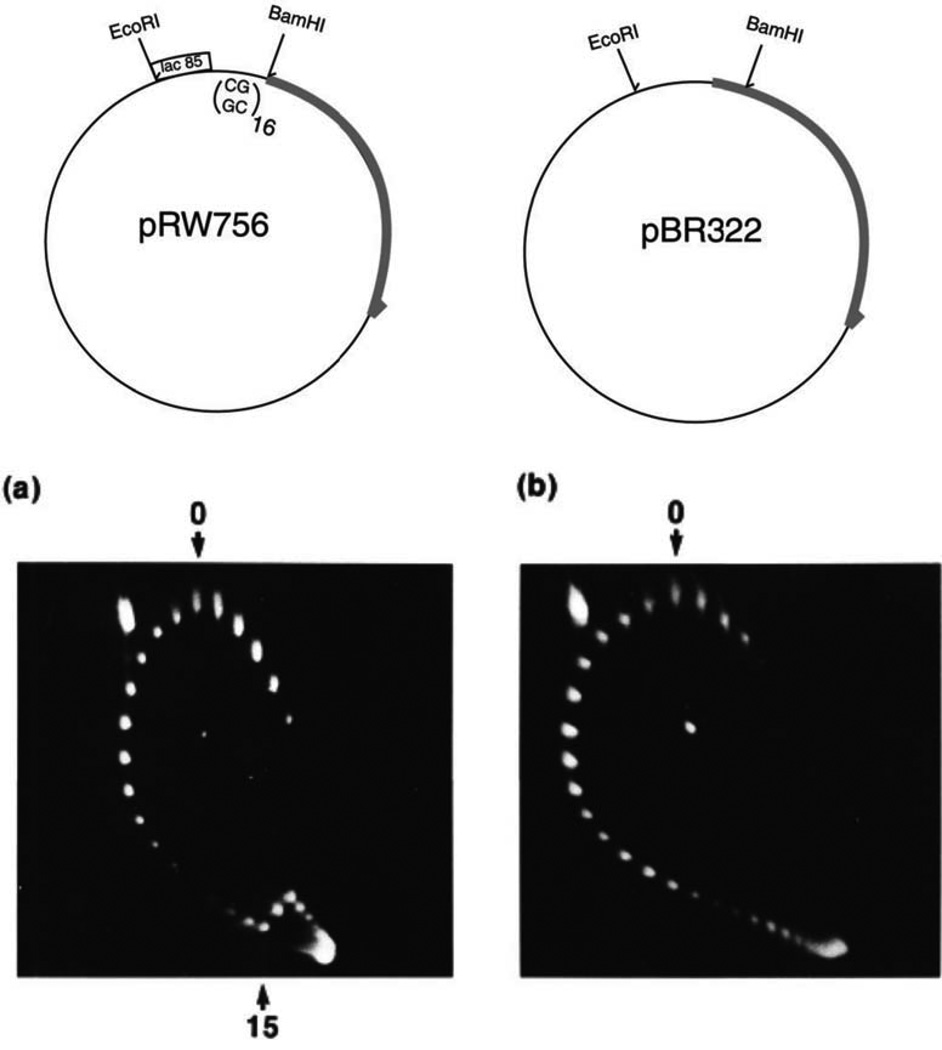

An example of a two-dimensional gel that illustrates Z-DNA formation is shown in Fig. 8. Panel A illustrates a series of topoisomers of plasmid pRW756 carrying a tract of repeating (dC-dG)16 (63). At topoisomer number 15 (Fig. 8A) a break appears in the pattern. The break reflects the critical energy required for adopting a left-handed conformation of the 32-bp dC-dG insert. At this point, the plasmid mobility in the second dimension shifts backward because negative superhelicity is released from plasmids that change the conformation of the insert to the left-handed form. The control plasmid lacking the 32-bp dC-dG insert behaves as a continuous series of spots with increasing negative supercoiling (Fig. 8B). Plasmids with different repeat lengths have been engineered to monitor supercoiling torsional strength in vivo (64, 65).

FIGURE 8.

Two-dimensional gel showing the transition from B- to left-handed Z-DNA in plasmid DNA. This research was originally published in Kang DS, Wells RD. 1985. B-Z DNA junctions contain few, if any, nonpaired bases at physiological superhelical densities. J Biol Chem 260:7783-7790. © the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f8

Cruciforms can form in supercoiled DNA at positions where perfect or near perfect inverted repeat sequences occur. Two general mechanisms promote cruciform extrusion. First, supercoiled plasmids can adopt the cruciform conformation when sufficient supercoiling energy is present to destabilize the Watson-Crick structure at the tip of the hairpin (66). The simplest sequence that forms a cruciform structure is a long run of the dinucleotide repeat dA-dT. The sequence (dA-dT)34 forms cruciforms with an unpaired adenine and thymine at the loop center in E. coli (67, 68). The second mechanism is coupled to DNA replication. As DNA becomes unwound at the replication fork, there is a potential for single-strand annealing. When a cruciform appears, it is a substrate for enzymes that stimulate Holiday branch migration, such as RuvAB, and it is also a substrate for Holiday-resolving enzymes: SbcC, SbcD, RuvB, and RuvC. These enzymes make long palindromes unstable in E. coli (69–72).

Intramolecular triplex DNA (H-DNA) may form at sequences containing long stretches of polypurine-polypyrimidine (73). In the H-form, half of either the purine- or pyrimidine-rich strand becomes unpaired, and its complement becomes triple stranded by forming Hoogsteen base pairs with purines in the major groove of the Watson-Crick base-paired segment (see Fig. 7). H-form DNA can be detected in vivo, but only under unusual circumstances (74). Intermolecular complexes can be formed with either RNA (75), which occasionally happens naturally (see below), during Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) reactions that cleave DNA (76), or with single-stranded oligonucleotides, which is useful for modifying gene expression patterns in vivo (77).

Another interesting case involves changes in super-coil density that modulates the efficiency of a plasmid recombination mechanism. Trigueros et al. (78) discovered that the multi-drug resistance plasmid pJHCMW1 contains a novel Xer recombination site (mwr) that converts dimeric or multimeric plasmids to the monomeric form. Other plasmids are known to contain a Xer site called cer, which works efficiently over a broad range of supercoil density. However, the mwr recombination efficiency was significantly lower when cells were grown under high-osmolarity conditions compared to low-osmolarity medium; the difference reflects a novel property of the mwr site that causes it to work better at high levels of DNA supercoiling that are achieved in low-osmolarity conditions. Many site-specific recombination reactions have been characterized, and some rely on negative supercoiling to achieve a functional synapse of directly repeated sites before strand exchanges. The Tn3/γδ resolution system is an example of a system with stringent requirements for supercoiling that spans a recombination efficiency of two orders of magnitude (79). This system has been developed so that one can pair a number of different mutant resolvases with a battery of supercoil sensors to efficiently and easily measure bacterial chromosome supercoil levels at many different sites in vivo (48, 55, 80, 81).

CONSTRAINED AND UNCONSTRAINED PLASMID TOPOLOGY IN VIVO

Circular plasmids such as the SV40 virus in human cells and pBR322 in bacterial cells have equivalent supercoil densities after the DNA is purified, but the basis of supercoiling is different in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. SV40 supercoils (82) are created by nucleosomes that bind DNA and wind almost two left-handed turns of DNA around every histone octomer (83). In E. coli, supercoiling is introduced by gyrase, a unique bacterial enzyme that catalytically introduces unrestrained supercoils in an ATP-dependent reaction.

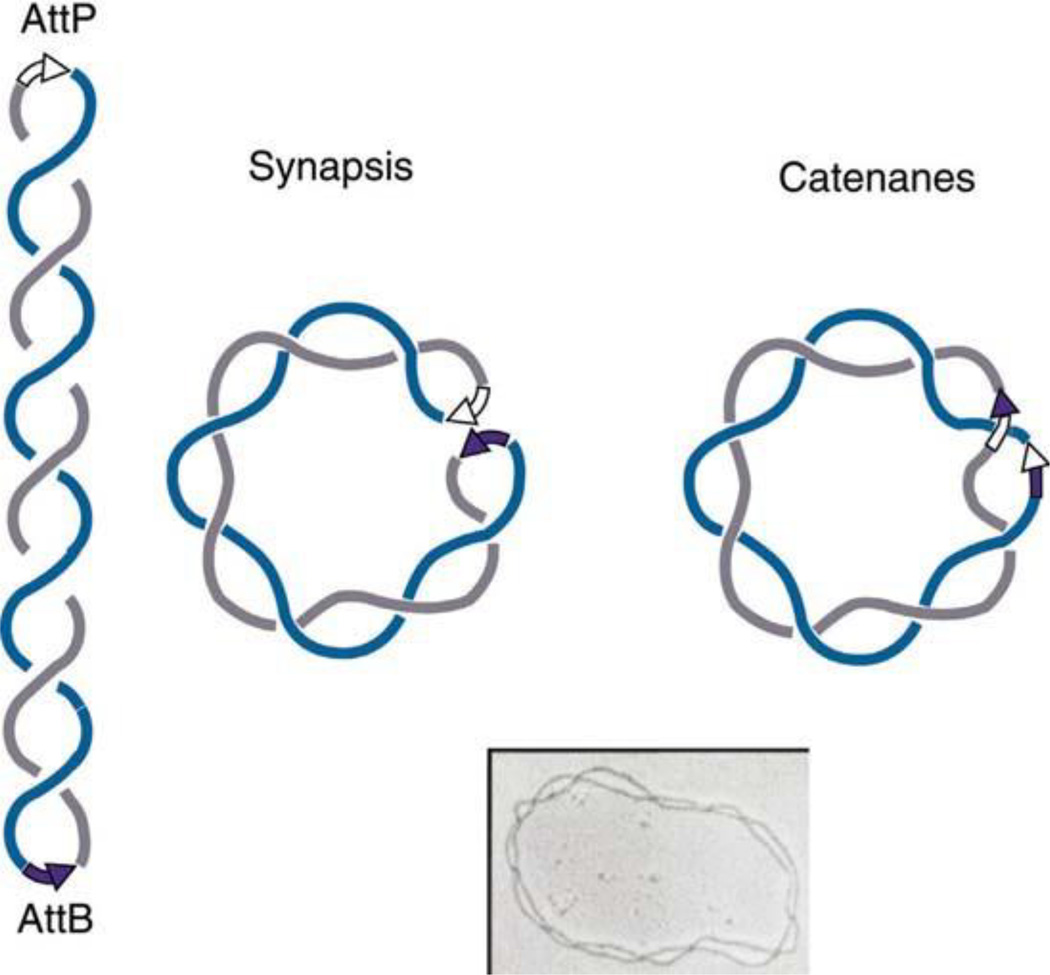

A variety of studies show that in E. coli only half of plasmid and chromosomal supercoiling is unconstrained and diffusible in vivo, suggesting the possible existence of histone-like proteins in bacteria. In one of the first experiments, Pettijohn and Pfenninger (84) created single-strand breaks in the F plasmid using γ-irradiation and allowed the breaks to heal while DNA gyrase was inhibited with novobiocin to block supercoiling. They measured the F plasmid supercoiling levels with two different methods and showed that about half the supercoils were retained in the absence of gyrase activity. Because single-strand breaks allow DNA to relax to the energy minimum, these studies strongly suggested that half of bacterial supercoiling is constrained in vivo. This finding by the Pettijohn lab has been confirmed numerous times, and the interpretation was made clearer with a clever site-specific recombination experiment by Bliska and Cozzarelli (85). Using a plasmid substrate containing the attB and attP recombination sites of phage λ, Bliska characterized intramolecular recombination catalyzed by the Int protein. If supercoiling exists in a freely diffusible interwound conformation, recombination between inverted sites should trap these supercoils as catenane links between the recombinant circles (Fig. 9). By calibrating the reaction in vitro and then carrying assays in vivo, they demonstrated that approximately half of the plasmid topology existed as interwound supercoils inside living cells (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Conversion of interwound negative supercoils into catenanes linked by site-specific recombination. EM reprinted from Spergler SJ, Stasiak A, Cozzarelli NR. 1985. The stereo-structure of knots and catenanes produced by phage lambda integrative recombination: implications for mechanism and DNA structure. Cell 42:325-334 with permission from Elsevier. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f9

Jaworski et al. (86) refined the estimate of constrained supercoiling by using plasmids with different segment lengths able to adopt the left-handed conformation (Table 1). Z-DNA conformation in vivo can be detected using several assays, including chemical reactivity of B-Z junction bases to osmium tetroxide (OsO4) (87), the left-handed inhibition of EcoRI-dependent methylation (88), and by changes in the linking number of plasmids after DNA switches to a left-handed conformation (89). Independent estimates confirmed these results by analysis of increased A-T sensitivity to chemical modification (67) and by cruciform formation (68).

PROTEINS THAT CONSTRAIN TOPOLOGY IN E.COLI

What constrains half of a cell’s topological structure inside a living cell? A number of abundant chromosome-bound proteins can constrain DNA topology (Table 2). In the section below, we provide snapshots of the most well-understood chromosome-associated proteins and a “back of the envelope” accounting of their potential contribution to constrained structure in vivo in E coli. Assumptions about individual proteins are given in each section. Assumptions about the bacterium are as follows: for the model, we used the supercoiling values reported for strain JTT1 in Table 1. E. coli has a 4,639-kbp genome equivalent (GE) (90). Assuming 10.5-bp helical turns in B-form DNA, one GE will have an Lk value of 440,000 under physiological conditions. Extrapolating plasmid measures of supercoiling to the large E. coli chromosome, JTT1 (σ = 0.059) would have a ΔLk value of 24,500 per GE. For cells growing exponentially in rich medium, the average cell contains partially replicated copies of DNA amounting to 3 GE (91, 92). The total cell ΔLk would be 73,800, with unrestrained ΔLk equal to 31,000 and restrained ΔLk equal to 42,100. There are two problems with this accounting. First, nobody has measured all of the critical parameters of a specific protein’s abundance and supercoil densities in the same E. coli strain under a uniform set of growth conditions. Second, attempts to experimentally confirm the calculation using mutants are frustrated by the facts that transcription contributes to supercoiling (see below) and that the group of proteins listed in Table 2 are all involved in regulating transcription in complex and interwoven ways (93). Elimination of one protein can be compensated for by changes in the expression patterns of other proteins, which makes it difficult to prove that any single protein accounts for a specific fraction of chromosome behavior in a WT cell. Nonetheless, making an educated estimate of this number from a growing body of data focused on specific DNA-protein complexes is a useful exercise (93, 94).

TABLE 2.

Nucleoid-associated proteinsa

| Protein | Mol./cell in exponential phaseb |

% σ Total | %σc | Mol./cell in stationary phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNAP | 3,000 | 5 | 8 | |

| HU | 30,000 | 16 | 30 | 15,000 |

| IHF | 6,000 | 0–3 | 0–6 | 27,500 |

| FIS | 30,000 | 9 | 15 | 1,000 |

| H-NS | 10,000 | 1.6 | 3 | 7,500 |

| STPA | 12,500 | 2 | 4 | 5,000 |

| DPS | 500 | ? | ? | 10,000 |

Constrained supercoiling estimates for the most abundant chromosome-associated protein in E. coli.

Mol., molecules.

RNA polymerase is a pentameric protein made up of the proteins (α2 ββ'ω) with a molecular mass of about 400 kDa. It is structurally conserved from bacteria to humans. About 3,000 molecules of RNA polymerase are present in E coli cells growing exponentially in rich medium, and two thirds of these enzymes are engaged in transcription. One consequence of transcription is that each RNA polymerase molecule influences DNA writhe and unwinds a short segment of the DNA template, which results in a ΔLk of +1.7 supercoils per RNA polymerase (95). On a 5-kb plasmid, 3 transcribing polymerases constrain 5 negative supercoils, irrespective of any torsional effects, and induction of transcription can add 6 or more polymerases, producing a shift of 10 polymerase-constrained supercoils (22).

HU protein is a heterodimer composed of HupA and HupB protomers (94). Both subunits are related to each other and to the subunits of IHF (described below). All three dimers (A2, AB, and B2) bind double-stranded DNA, single-stranded DNA, and RNA (96). The double-stranded DNA binding site for HU-DNA complexes spans 36 bp. DNA-co-crystals and modeling experiments suggest that, like IHF, the HU protein bends DNA by >150° (93, 94). In vivo cross-linking experiments show that the predominant form of HU is AB, but A2 and B2 homodimers can be detected in the early exponential phase (97, 98). In exponential phase cells growing in Luria broth, HU is estimated to be present at about 30,000 molecules per cell (99). Of all the known small nucleoid-associated proteins, HU is clearly responsible for the largest effect on plasmid supercoiling (100, 101).

HU constrains supercoils in vitro and, like nucleosomes, it can produce supercoiled plasmid DNA when incubated with either supercoiled or relaxed circular plasmid DNA plus an enzyme like the calf thymus Topo I enzyme, which removes either positive or negative supercoils (see above). At the optimum supercoiling ratio of protein and DNA, 2.5 AB HU dimers constrain one supercoil (102). Assuming this number reflects the conditions in a living cell, HU would account for 12,000 supercoils, or about 16% of total ΔLk and 40% of constrained topology. HU also promotes the circular ligation of DNA fragments shorter than the persistence length (103).

Strains carrying hupAB deletions show a slow growth phenotype (101) and are sensitive to γ- and UV-radiation (104). Analysis of plasmid DNA supercoiling in hupAB mutants of both E. coli and S. typhimurium agrees with the above calculation; the mutant exhibits a 15% loss of plasmid supercoiling and a broadening of the topoisomer distribution (101). Although it has never been measured using a torsion-sensitive assay (see below), the simplest explanation is that hupAB mutants lose primarily constrained supercoil structure.

Integration host factor (IHF) is a heterodimer encoded by two genes that are independently regulated: ihfA (himA) and ihfB (hip). IHF is closely related to HU in sequence and structure (93). IHF has a DNA binding site of 36 bp, and one can think of this protein as sequence-specific and less abundant HU. The consensus for IHF binding is a 13-bp sequence, WATCAANNNNTTR, and IHF recognizes this site by interactions in the minor groove of DNA (105). When added alone to plasmid DNA, IHF does not show significant supercoiling activity in the Topo I assays. However, IHF dramatically bends DNA by 150° at its high-affinity sites and makes a structure that is optimally located at the end of a super-coiled loop (106–109). Bending by IHF is implicated in many genetic systems, as mutant strains show expression changes in about 100 E. coli genes (110). In the presence of HU, IHF can bind DNA that does not contain a consensus site, and single-molecule studies demonstrate that IHF has a large compaction effect in single-molecule experiments (111). Although the ability of IHF to induce supercoiling has not been reported, in Table 1, based on IHF abundance, we indicate a constrained supercoiling effect of between 0 and 6% of constrained supercoiling, with the upper limit set for IHF nonspecific supercoiling that would approach HU (1 supercoil per 2.5 dimers).

FIS (factor for inversion stimulation) is a homo-dimer encoded by the fis gene. FIS binding sites are complex; reports range from a footprint of 21 to 27 bp, with a consensus sequence of GNtYAaWWWtTRaNC (93). FIS is most abundant in cells growing exponentially in rich medium, with estimates ranging from 30,000 to 60,000 copies/cell (99, 112). FIS is capable of supercoiling DNA weakly in the Topo I supercoiling assay of relaxed plasmid DNA in vitro. FIS has several well-characterized roles in enhancing loop-dependent reactions that include phase inversion in S. typhimurium pilus type, G-inversion of the tail fiber of bacteriophage Mu, and upstream promotor (UP)-element stimulation of transcription of growth rate–regulated genes such as rrn P1 (113). Bending angles for specific FIS-DNA complexes are reported from 45 to 90°. Assuming FIS forms a DNA interaction that averages a 75° turn, or half the supercoiling potential of HU and IHF, 30,000 copies of FIS could account for 15% of constrained in vivo supercoiling. Single-molecule studies suggest that clusters of FIS might organize DNA segments into supercoiling domain barriers (114), although this has not been observed in vivo.

Histone-like nucleoid structuring (H-NS) protein is a homo-dimeric protein that, like HU, is able to bind double-stranded and single-stranded DNA as well as RNA (93). A high percentage of the protein exists as homodimers (115, 116), although higher oligomeric species are also found in solution (117–119). In log phase, estimates of H-NS concentrations vary from 10 to 20,000 molecules/cell (99). On double-stranded DNA, an H-NS homodimer is estimated to bind approximately 10 bp (120). Thus, unlike HU and IHF, which require 2 to 3 dimers to supercoil DNA, a much higher cooperative interaction is most likely necessary for H-NS to supercoil the DNA. H-NS binds preferentially to A/T-rich sequences and has the ability to supercoil DNA in the Topo I assay (121–123). H-NS is thought to regulate about 100 E. coli genes either directly or indirectly (123–125). It also is an element that enforces silencing of multiple operons including the bgl operon of E. coli (126), the proU operon of Salmonella and E. coli (120, 127), and bacteriophage Mu (128). Many of the genes regulated by HNS are related to starvation and stress responses (129). H-NS can spread along DNA sequences from a single high-affinity site (120, 130–133). In addition to forming homo-multimers, H-NS forms heteromeric complexes with a related protein, StpA (see below) (123, 134). Although H-NS has been proposed to be a regulator of DNA supercoiling, the collective analysis of plasmid supercoiling in hns strains shows no clear trend. Some plasmid data show increased supercoiling, some show decreased supercoiling, and some show no change (128, 135–140). This may be a case where plasmids mislead the interpretation of chromosome supercoiling (see below). Atomic force microscopy images show that unlike HU, IHF, and Fis, which make solenoidal structures, H-NS directly stabilizes an interwound form of DNA (141), and its ability to stabilize supercoils may depend on specific DNA sequences. A recent crystallographic structure shows that two-domain interactive bridging accounts for H-NS-dependent negative supercoiling (142). Molecular dynamics simulations indicate how nonspecific bridging interactions would drive molecular aggregation (143). Super-resolution fluorescent imaging of H-NS shows that H-NS forms novel clusters near the nucleoid center, which is different from all other nucleoid proteins (144). There is also evidence that ionic conditions may modulate the stability of H-NS structures (145–147). The sole study of chromosomal supercoiling using psoralen cross-linking concluded that hns mutants have slightly increased unconstrained supercoiling (148). However, this effect might be caused by the increased transcription around the genome that is observed in H-NS deletions. Assuming that 10,000 copies of H-NS can coat 20,000 bp of interwound DNA at a σ of −0.06, it could account for 3% of in vivo constrained supercoiling.

StpA (stpA 25,000 molecules/cell) was discovered as an E. coli gene that was involved in the splicing of a bacteriophage protein. Sequence analysis showed it to be closely related to H-NS (134), and subsequent studies demonstrated that these proteins share extensive structural similarity and form heterodimers. The significance of the homo- and hetero-dimeric species remains to be demonstrated, but cross talk seems likely. Nonetheless, several hns phenotypes are not altered in stpA strains, but others are. Like H-NS, the double-stranded DNA binding site is 10 bp, and like H-NS, homomeric ensembles of StpA spread along DNA as filaments that block access to the DNA (149). Slightly more abundant than H-NS, StpA could account for 4% of constrained supercoiling.

VARIATION OF CONSTRAINED AND UNCONSTRAINED SUPERCOILING IN VIVO

The ability to distinguish between constrained and unconstrained supercoiling is often necessary to fully explain topological changes that can be measured in plasmid DNA. Torsional strain (diffusible supercoiling) can be estimated using psoralen cross-linking in both plasmids and the bacterial chromosomes (84, 148, 150). Three cases illustrate the usefulness of understanding both constrained and unconstrained topology: (i) the importance of σD levels in biological control of closely related strains and species of bacteria, (ii) sequence-dependent topology of RNA-DNA triplexes, and (ii) topA’s critical role in controlling RNA-loop initiation.

Case 1

Although plasmid supercoil measurements have been performed using several E. coli strains and related bacterial species, experiments that discriminate between the fractional distribution of free interwound supercoils and constrained supercoils are rare. Z-DNA and cruciforms provide one method to perform such analyses. Plasmids are available in which different lengths of dG-dC are cloned at the same position in a pBR322-derived backbone, and the energy needed to adopt the left-handed form has been calibrated in vitro (89). By transforming bacterial strains with a panel of such plasmids, one can measure both the torsional strain, reported by the repeat length needed to adopt left-handed conformation, and the linkage state of the parental plasmid. Jaworski et al. (86) showed that both constrained and unconstrained supercoiling vary independently (Table 1). For example, torsional strain decreased in the presence of a mutation in gyrB and increased in a topA strain (Table 2). However, different E. coli strains (HB101 and JTT1) with a WT complement of topoisomerases and nucleoid binding proteins (see above) produced a significantly different balance of these two supercoiling states (37 and 43% −σD, respectively). E. coli generates more unconstrained supercoil tension than the closely related Gram-negative organisms. S. typhimurium, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Morganella all showed a significantly lower fraction of unconstrained supercoiling than E. coli (58, 86), which explains the different phenotypes for the topA genes in E. coli compared to S. typhimurium (23, 151–154). In addition, the phenotype of many nucleoid-associated proteins are different between Salmonella and E. coli (58). For example, deletion of the bacterial condensin (MukB) is tolerated in E. coli but is lethal under identical conditions in Salmonella. Also, deletions of SeqA are sick in E. coli but healthy in Salmonella, and specific mutations in GyrA and GyrB have significantly different effects in the two species. The phenotypes can be explained by the different supercoiling densities of the two species: Salmonella is 15% lower than E. coli (σ = 0.059 and −0.069, respectively) (58).

Case 2

DNA topology is sometimes influenced by unexpected factors. One example is the formation of an R-loop in plasmid DNA. An R-loop unwinds the Watson Crick helix and creates +σC. The subsequent release of RNA by alkali lysis leads to a compensating increase in (−) ΔLk. Early on, the R-loop effect was misinterpreted to be diffusible hyper-σD. R-loop formation occurs during transcription as the RNA polymerase opens a single-strand bubble in the Watson Crick double helix as it moves along DNA. Normally, polymerase rewinds Watson Crick strands back together, and the RNA transcript and rewound DNA exit through separate channels, but the displaced DNA strand is accessible (155). Under circumstances where the complementary strands do not rewind, RNA can remain hydrogen-bonded to the template in an R-loop. The earliest example of an RNA-plasmid heteroduplex involved the initiation of DNA replication in ColE-1 and its derivatives that include pBR322 and the pUC plasmids. Two RNA molecules regulate R-loop formation. RNAI is a 600-bp transcript that primes DNA synthesis, and RNAII is a regulatory RNA that controls the efficiency of the initiation process by binding to RNAI (156). Interactions between the 5′ end of the RNAI and the transcribing RNA polymerase cause the 3′ end to form an R-loop that initiates DNA replication. To form the RNA loop, a sequence at the 5′ end of RNAI interacts with the displaced DNA strand as RNA polymerase transcribes the plasmid ori region. When the 5′ end of RNAI and the displaced DNA strand interact, a stable RNA hetero-duplex is produced at the origin (157). RnaseH and DNA PolI process the RNA-DNA complex to prime DNA replication.

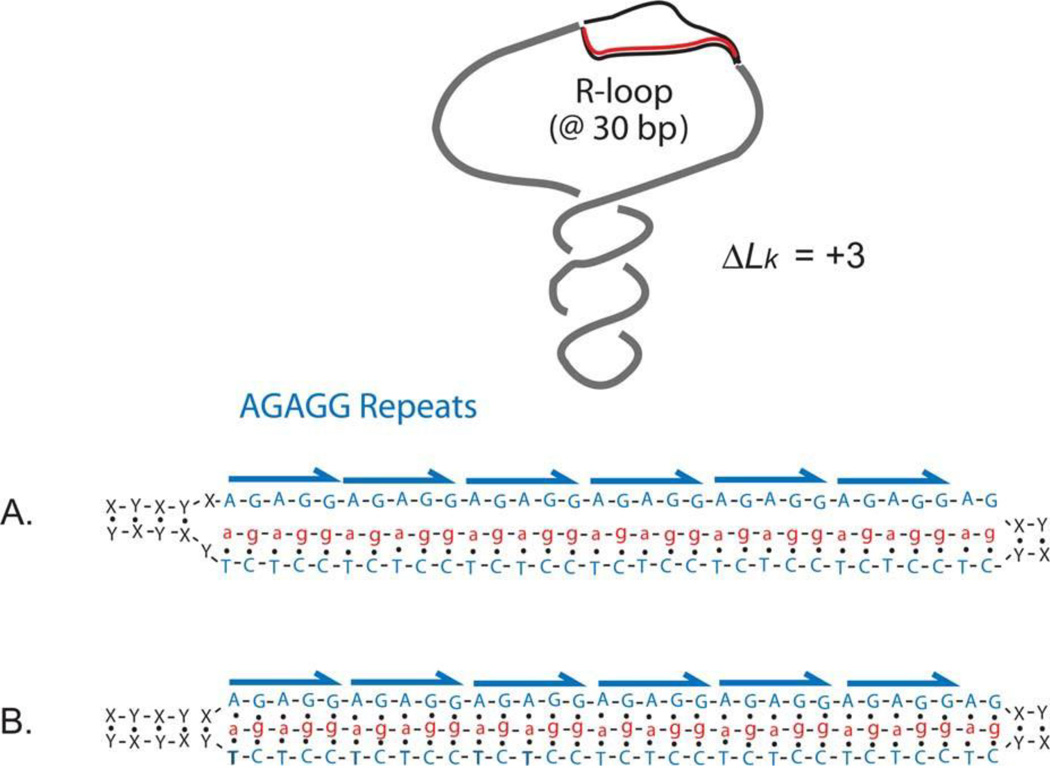

When stable RNA-DNA structures arise, they can generate confusing data. One example is the chicken IgA immunoglobulin switch region. The switch region encodes the repeating 140-bp sequence (AGGAG)28 that plays a functional role in switching immunoglobulin isotypes (158). When a plasmid containing this insert is transcribed by either E. coli or T7 polymerase (in vitro or in vivo) in the same direction as occurs in a chicken cell, the product is a remarkably stable 140-bp RNA-DNA hybrid that withstands melting temperatures up to 98° (159). The defined structure of the RNA-DNA complex remains unproven, but the most likely conformation is the typical R-loop (Fig. 10A), with a less likely possibility being the intermolecular triplex (Fig. 10B). If relaxed DNA is used as the template for transcription in vitro, the plasmid migrates near the position of a +12 topoisomer. Once this is formed in vivo, gyrase adds 12 additional (−) supercoils, and most popular kits for isolating plasmids exploit alkaline lysis, which removes the R-loop RNA, adding 12 more (−) supercoils to yield a hyper-negative plasmid. Unless the researchers know that there was a stable R-loop RNA formed in the plasmid, they can wrongly conclude that the plasmid existed under high negative supercoiling tension in vivo (see reference 160). Another R-loop-inducing system is found for DNA triplet repeat sequences that expand and contract in the human genome and are often associated with neurologic diseases such as fragile X syndrome, Friedrich’s ataxia, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (161). Long stretches of the triplet repeat sequence of CTG.CAG can trigger R-loop formation during active transcription in E. coli (162). The suggested mechanism is shown in Fig. 11. During transcription the CTG.CAG repeats can form hairpin loops on the nontemplate strand of DNA. This secondary structure impedes the rewinding of the non-template and transcribed strand, initiating an R-loop that can extend throughout the total length of the repeat sequence (163).

FIGURE 10.

Alternative RNA-DNA structures that contribute to constrained supercoiling in a plasmid containing a fragment of the chicken IgA immunoglobulin switch region during transcription. The R-loop structure shown in (A) results in a displaced strand of DNA that constrains a ΔLk of about +1 for every 10 bp of RNA/DNA hybrid. (B) shows the structure of an intermolecular triplex in which Hoogsteen base pairing occurs in the major groove of the DNA strand (see reference 159). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f10

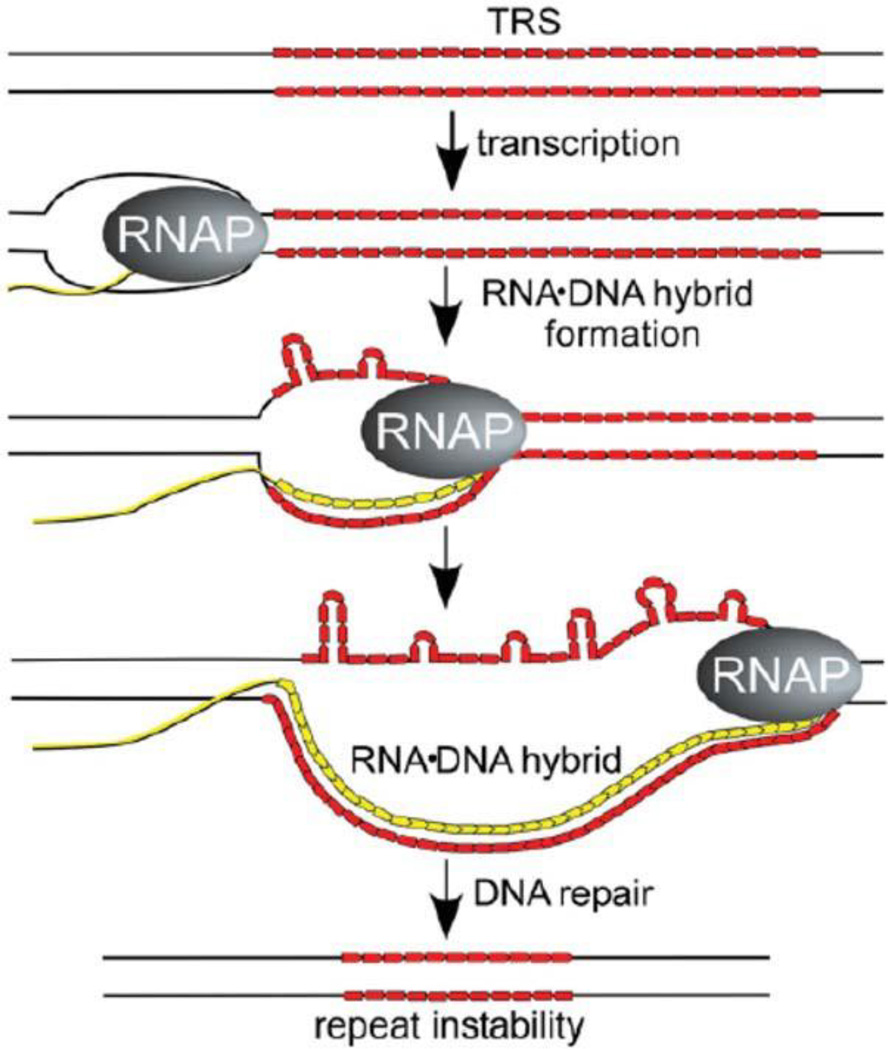

FIGURE 11.

Proposed mechanism for stable RNA-DNA hybrids that can stimulate repeat instability. Transcription of DNA regions containing CG-rich trinucleotide repeats (red) favors formation of stable RNA-DNA hybrids. The displaced nontemplate DNA strand can adopt non-B DNA structures, such as CTG or CAG hairpins. The unpaired regions of the nontemplate strand are reactive to bisulfite modification. Reprinted from reference 162 with permission from the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f11

Case 3

Hyper-negative topology in plasmids isolated from topA mutants was initially considered to be an example of very high diffusible supercoiling. Pruss and Drlica discovered that plasmids like pBR322, which encode a membrane-bound tetracycline export pump, exhibited a hyper-negatively supercoiled phenotype in strains that lack a fully functional topA gene (164). Subsequent work demonstrated that this effect was due, in part, to association of the plasmid with secretion machinery that led to membrane insertion of the Tet protein while it was being transcribed. The hyper-supercoiling phenotype was not restricted to Tet and could be demonstrated for several proteins that were either cotranscriptionally inserted into the membrane or cotranscriptionally exported to the periplasm or outer membrane (165). Essential for the assay was the presence of a topA mutation, which encodes the protein that normally removes negative supercoils. The explanation was that torsional effects on plasmid DNA are mediated by membrane anchoring in the absence of full relaxing power of Top I. During transcription, gyrase replenished negative supercoils downstream of the transcription terminator, creating a super-abundance of negative supercoils (54, 166). An important factor in resolving the true mechanism came from a plasmid with a Z-DNA-forming segment. From the known transition point of this plasmid, the researchers expected the plasmid to exist in the Z-DNA in vivo. However, there was no sign of left-handed DNA, which suggested that the additional supercoils were constrained in vivo (160). Drolet later proved that hyper-negative supercoiling under these conditions was caused by plasmid R-loops (167, 168). Consistent with this theme is the observation that overexpression of RnaseH ameliorates the hyper-supercoiled phenotype of a topA mutant in E. coli (168).

Another protein that is important in controlling RNA-DNA interactions during transcription is the Rho protein, which exerts its effect by terminating transcription complexes that are not followed by translating ribosomes (169). The fact that topA is critical for preventing R-loop formation in plasmids suggests that this is an essential role for the protein, and the free unconstrained supercoil level of E. coli may require more TopA activity than other bacteria with lower unconstrained superhelix densities (see above). R-loop formation is most easily observed in plasmids, but this phenomenon occurs in large chromosomes as well.

DNA REPLICATION: REVERSIBLE FORKS, CATENANES, HEMICATENANES, AND KNOTS

Plasmids have been used in the dissection of many complex steps in DNA replication. The mechanism that initiates a round of replication was worked out first for the unidirectional ColE-1 origin (169), and plasmids containing the origin of phage λ and E. coli oriC sequences served as model substrates for establishing bidirectional replication in vitro (170, 171). When the genetic elements of the ter/Tus system were discovered, plasmids were used to study the mechanism of inducing a sequence-directed replication pause in vitro and in vivo (172). Plasmids continue to be useful in dissecting important stages of DNA replication. Three examples illustrate the power of plasmids for studies of DNA repair and topological reactions that occur in front of, or behind, a replisome (Fig. 12).

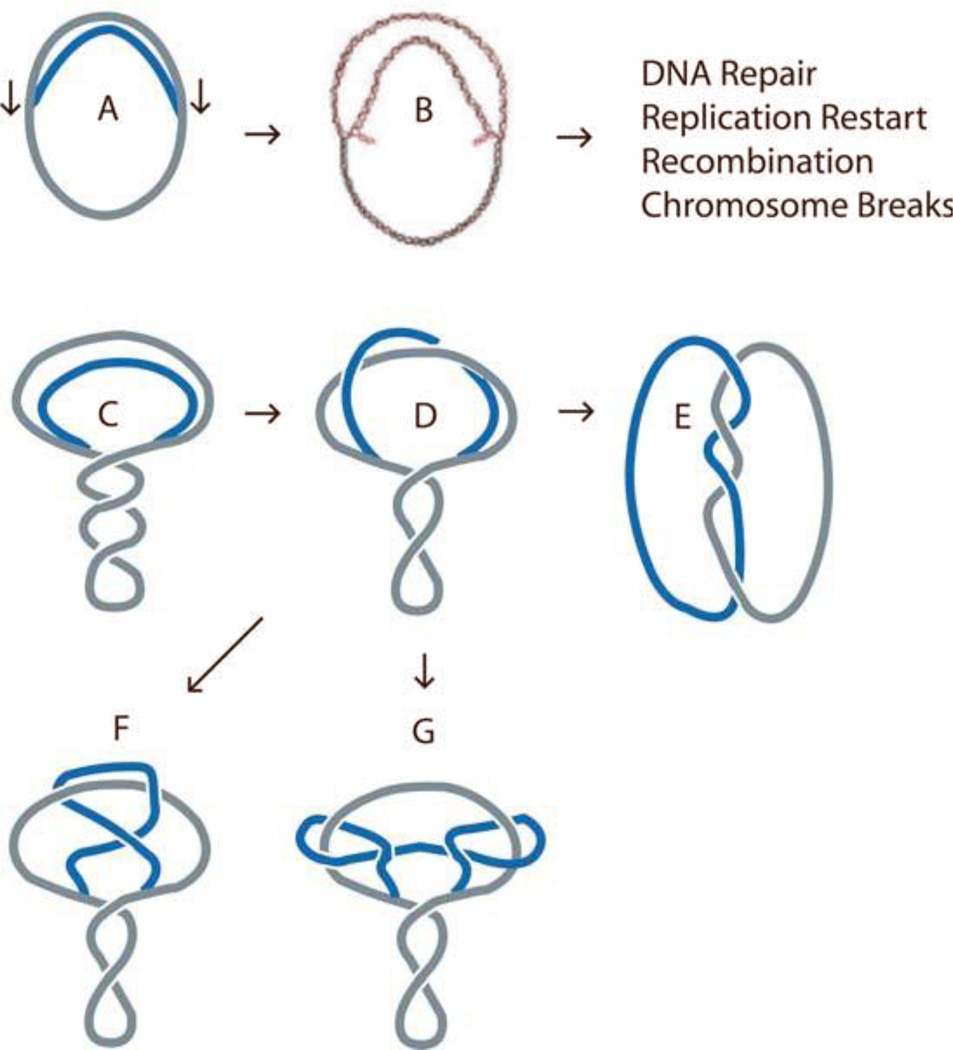

FIGURE 12.

Replication intermediates identified in plasmid replication systems. (A) Replication initiated at a unique position leads to dual forms that move toward the terminus of replication. (B) Introduction of positive supercoils leads to replication fork reversal and formation of a four-way junction. (C) Negative supercoiling, which is generated by gyrase ahead of the fork, can be converted into precatenanes (D), which become catenanes (E) upon completion of DNA synthesis. (F, G) Topoisomerase activity in the replicated region can lead to complex knots. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f12

Fork Reversal

As DNA elongation proceeds from an initiation site, the machinery that carries out synthesis works in a semi-discontinuous pattern. The E. coli DnaB helicase unwinds the double helix, and on one side of the fork, DNA replication extends processively in the 5′ to 3′ direction. The opposite side of the fork is synthesized in a discontinuous mode that requires multiple reinitiation events and short replication tracks called Okazaki fragments. However, these two patterns are coordinated within the replisome, and if an impediment to DNA synthesis is encountered on either template strand, DNA replication machinery slows down or comes to a halt. DNA damage caused by chemical nucleotide modification is one example of a blocking lesion that can occur in DNA, and even under ideal conditions, chemical base damage is encountered in nearly every round of replication (173). Some DNA damage can be bypassed, but most damage must be repaired. Repairing DNA damage requires replication forks to sense damage and respond to different types of damage in a sophisticated way. About 40 years ago a model was proposed to explain how damage on the template for continuous synthesis could be bypassed after fork reversal (174) (Fig. 13). Branch migration at the fork can pair the two nascent strands, which forms a structure that can prime and carry out repair synthesis that will breach the block caused by a damaged nucleotide. Reversing the branch migration product, which can be carried out by a number of enzymes (175), allows fork movement to restart and bypasses damage with high-fidelity polymerases (175). The original damage can then be repaired by excision repair enzymes post-synthesis.

FIGURE 13.

Model of replication repair. Strand displacement and branch migration create an alternative replication template allowing replication to bypass a lesion (X). Reproduced from reference 174 with permission from Elsevier. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f13

Although the model was conceived in eukaryotic cells, evidence supports the role of fork reversal in vitro and in vivo in bacteria as well. Using a bidirectional replication system in a specialized plasmid that carries oriC and two ter sites to pause replication forks at specific points in a plasmid, Postow et al. demonstrated that fork reversal could be easily induced by incubating paused replication intermediates with ethidium bromide (176). The explanation for this result is that positive super-coiling induced by the intercalation of ethidium caused fork branch migration that generated a four-way junction. These structures were called chicken feet (177). Positive supercoiling might be generated ahead of a replication fork, but the question of whether reversed forks exist in vivo remained unanswered. Experiments by Courcelle et al. (178) provided physical evidence for reversed forks in E. coli. PBR322-containing cells were treated with controlled doses of DNA damage, which was followed by plasmid extraction and analysis by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Structures at the predicted position of reversed forks appeared as a cone above the normal two-dimensional plasmid profile (Fig. 14). The appearance and disappearance of these reverse forks closely followed a genetic repair response, which is strong evidence that fork reversal and repair do occur in vivo.

FIGURE 14.

Replication fork reversal in vivo (see Fig. 12). Reprinted from reference 178 with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f14

Catenanes and Hemicatenanes

Plasmids are powerful tools for studying DNA segregation. Replication intermediates are substrates for topoisomerases and repair enzymes, but what happens immediately after replication remains unclear (179, 180). The newly replicated chromosome segment (behind the forks) cannot be supercoiled because the nascent strands contain nicks that provide swivel points. Negative supercoiling introduced by DNA gyrase can exist in the unreplicated portion of the molecule (Fig. 12C) because the parental template strands provide a topologically closed system (181, 182). If the forks are not constrained by proteins or cotranslational attachment to the cytoplasmic membrane, negative supercoils may diffuse across the forks and exist as a mix of supercoils and links between the replicated daughter segments of the chromosomes (Fig. 12D).

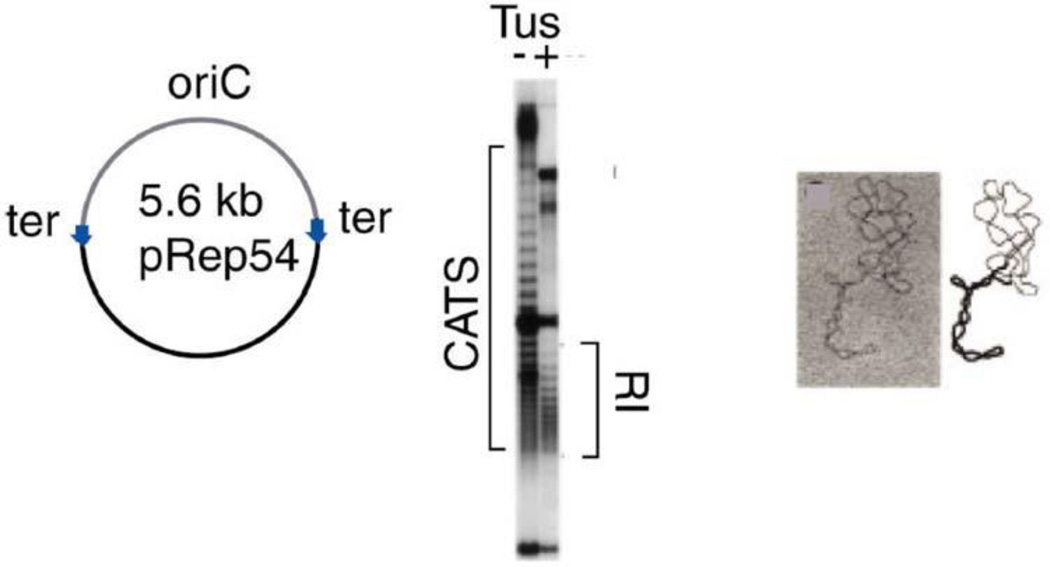

Peter et al. analyzed the structure of replication intermediates accumulated by Tus-arrested replicating plasmids in vitro and in vivo (182). In the absence of a fork-blocking Tus/ter complex, replication produced catenated dimers (Fig. 15). When Tus/ter complexes were present, the daughter DNA segments were wound around each other, and linking was roughly evenly distributed between left-handed negative supercoils in the unreplicated segment of the molecule and left-handed links between daughter segments (Fig. 12C – D). These links can become catenane links between fully replicated daughter molecules at the completion of DNA synthesis (Fig. 12D – E); they are often called precatenanes. High-resolution gels indicated that 80% of neighboring plasmid topoisomers differed by two nodes rather than one (Fig. 15, center). This suggests that a type II topoisomerase(s) works behind forks since type I enzymes would generate distributions separated equally by steps of one (182) (Fig. 15). How (or whether) this type of strand movement occurs within a replicating bacterial chromosome remains an important question to be addressed.

FIGURE 15.

Resolution of catenane (CATS) and precatenane links (RI) in plasmid DNA (see Fig. 12). Reprinted from reference 182 with permission from Elsevier. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f15

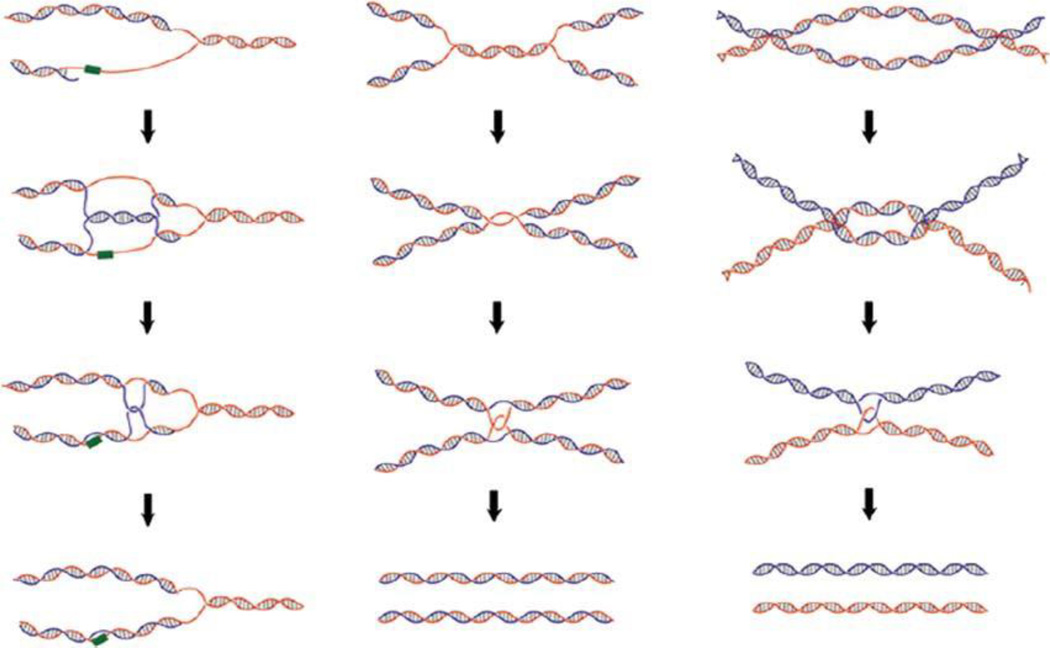

Hemicatenanes represent the condition where two DNA duplexes are joined through a single-stranded interlock rather than the catenane discussed above that joins two DNA circles with linkages involving both strands of DNA. Hemicatenanes can occur and be stable between two linear DNA molecules, while catenanes separate when one circle becomes linearized. Historically, hemicatenanes have been observed but have been hard to study because they were hard to make. Recently, purification of the NeqTop3 enzyme from the hyperthermophilic archaeum, Nanoarchaeum equitans, has solved the problem (183). This thermophile encodes a type IA topoisomerase that works at 80°. At the high temperature and at high enzyme levels, NeqTop3 generates complex hemicatenane networks by binding and linking DNA at A-T rich regions that become unpaired by transient breathing. The enzyme removes negative supercoils from supercoiled DNA with the same enzyme mechanism as E. coli Top I and Top III, but at low enzyme concentrations NeqTop3 will dissolve the hemicatenated DNA that it makes at high enzyme levels. Three examples of situations where hemicatenanes form and are important in vivo (Fig. 16) include a replication fork blocked on the discontinuously synthesized strand (left), the point at which converging replication forks meet during bidirectional chromosome replication, and the final disposition of a double-Holiday junction in which branch points move together to result in a single hemicatenane linkage.

FIGURE 16.

Schematic models for generating hemicatenanes during DNA replication. Three pathways to yield hemicatenane structures are shown. (Left) Lagging strand synthesis encounters a damage site, and the pairing of the lagging strand with the complementary leading strand can produce a pseudo-double Holliday structure. Dissolution of the pseudo-double Holliday structure leads to hemicatenanes and allows replication to bypass the damage site. (Center) Convergence of two replication forks at the final stage of replication can lead to either a single-strand catenane or hemicatenane conjoining two replicated duplexes. Both single-strand catenanes and hemicatenanes can be resolved by a type IA topoisomerase, allowing the segregation of the daughter chromosomes. (Right). Convergent branch migration of a double Holliday junction can generate a hemicatenane. Reproduced from reference 183 with permission from the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f16

Knotted Bubbles

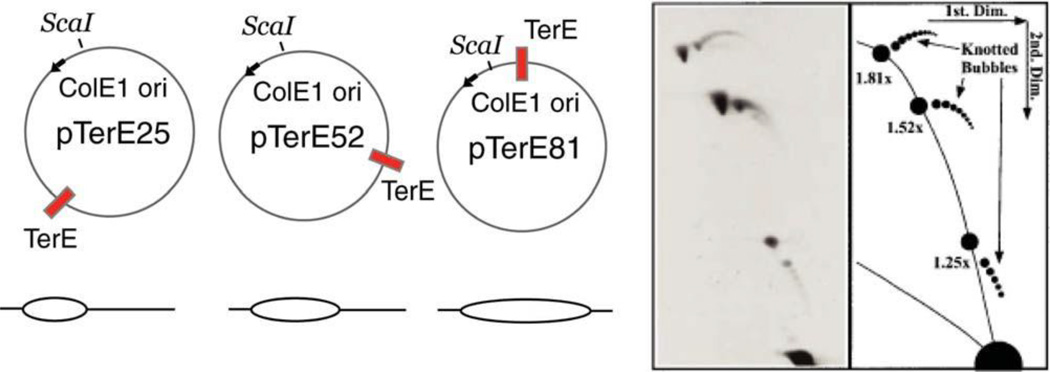

In the region behind the fork, topoisomerases can act to either remove precatenane links (see above), which would be equivalent to removing supercoils, or topoisomerases can introduce simple and complex knots in the precatenane portions of the plasmids (Fig. 12F, G ). Recent work provides evidence for topoisomerase-mediated knots in the replicated precatenane portion of molecules in vivo. As in the studies by Peter mentioned above, Olavarrieta et al. exploited plasmids designed to arrest replication forks, with different segments of the plasmid represented by a replicated sector (184). A high-resolution two-dimensional gel analysis resolved mixtures of three plasmids: pTerE25, pTerE52, and pTerE81 (Fig. 17). Knotted bubbles provided a strong argument that a type II topoisomerase (Topo IV) must have been at work behind forks either during replication or while the forks were stalled at the Tus/ter complexes. It is not known whether the blocked replication forks, which are necessary for accumulating these populations, create intermediates that do not reflect structures occurring during unimpeded fork movement. Nonetheless, the experiments demonstrate the impressive ability of two-dimensional gels to analyze a wide range of biochemical functions in DNA metabolism.

FIGURE 17.

Knotting of replication bubbles in vivo. Reprinted from reference 184 with permission from Wiley. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PLAS-0036-2014.f17

Plasmid Data Can Obscure Conditions in a Bacterial Chromosome

Because supercoiling density in the chromosome is difficult to measure, investigators often rely on plasmids to gauge chromosomal supercoil levels and to interpret the effects of mutant enzymes or structural protein mutations on DNA structure. However, plasmids can mislead as well as inform. In addition to the R-loop issues discussed above, there are scenarios where one can make erroneous conclusions from plasmid data. One example is the practice of reporting chromosomal supercoiling density from the plasmid population. If the distribution is normal, that is a good sign, and the mean chromosomal situation may mirror the plasmid average. But when a broad distribution of plasmid topoisomers is seen, the common practice is to report the value of the center of plasmid distribution as the chromosomal supercoil density mean. The problem is that a broad or biphasic supercoil distribution is often a sign of a heterogeneous cell population (i.e., some fraction in a dramatically different physiological state than the normal WT). Sick or dying cells can have relaxed plasmids because of a low pool of ATP or a low ATP/ADP ratio, while healthy cells generate normal densities. Heterogeneous ensembles often mean that there are essentially no chromosomes in the population with a supercoil density indicated by the center of the plasmid distribution.

A second example comes from experiments in a novel gyrase mutant (gyrB652TS). This mutation has a temperature-sensitive (TS) phenotype, but the GyrB652 enzyme does not lose activity at the restrictive temperature of 42°C. The gyrB652 mutation produces an enzyme with a low catalytic turnover number relative to WT at all temperatures from 30°C to 42°C (185). GyrB652 strains stop growing at high temperatures because the supercoiling rate cannot keep up with the pace of (+) supercoiling generated by RNA transcription, which obeys the Q10 rule. The rule states that chemical reaction rates double for every increase of 10°C (see reference 48). In cultures of Salmonella growing at 30°C, a GyrB652 culture loses 95% of the normal σD, even at the permissive temperature of 30°C (σD = 0.005). Band-counting analysis of pUC19 DNA isolated from this mutant grown at either 30° or 42°C showed a σD of 0.030. The explanation is that, given time, GyrB655 gyrase will supercoil DNA up near the WT limit because pUC19 has no strong promoters, and negative supercoils generated by transcription cancel out by diffusing around the circle (54). We completely missed the large impact of this gyrase mutation on chromosomal supercoiling by assuming that pUC19 was a good model for the chromosome. Even when plasmids have a strong promoter, the most significant topological effect of transcription is the constrained 1.7 supercoil/RNAP on the DNA (186).

CONCLUSION

The postgenomic scientific world is witnessing a dramatic shift from a strong interest in basic science to correlation science, with a theory that computer-assisted analysis of complex and sometimes questionable data is the future of modern medicine. Molecular structure/function studies of the biochemical processes that underpin major diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and emerging genetic, viral, and microbial infections, are disappearing from funding portfolios at the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. In the past year principal investigators dropped out of the NIH support portfolio, which is a record bad year. The teaching of basic science is also being cut, as medical schools join a stampede to cash in on “translational science,” which is advertised to be the proven method for speeding discoveries from basic science to the bedside. This article’s historical perspective is intended to illustrate the amazing nuance of DNA structure and function and to provide examples of powerful basic methods that have been developed to understand enzyme mechanics and measure the quantitative topological properties of DNA. As such, it is dedicated to those who chose to work on the difficult basic science front lines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Work in the laboratory of N.P.H. has been supported by NIH grant GM33143 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Work in the laboratory of A.V.V. has also been supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: We declare no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vinograd J, Lebowitz J, Radloff R, Watson R, Laipis P. The twisted circular form of polyoma viral DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;53:1104–1111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.53.5.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer WR, Crick FHC, White JH. Supercoiled DNA. Sci Am. 1980;243:100–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calugareanu G. Sur las classes d’isotopie des noeuds tridimensionnels et leurs invariants. Czech Math J. 1961;11:588–625. [Google Scholar]

- 4.White JH. Self-linking and the Gauss integral in higher dimensions. Am J Math. 1969;91:693–728. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuller FB. The writhing number of a space curve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:815–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown PO, Cozzarelli NR. A sign inversion mechanism for enzymatic supercoiling of DNA. Science. 1979;206:1081–1083. doi: 10.1126/science.227059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vologodskii AV, Cozzarelli NR. Conformational and thermodynamic properties of supercoiled DNA. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1994;23:609–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.23.060194.003141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laundon CH, Griffith JD. Curved helix segments can uniquely orient the topology of supertwisted DNA. Cell. 1988;52:545–549. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adrian M, Wahli W, Stasiak AZ, Stasiak A, Dubochet J. Direct visualization of supercoiled DNA molecules in solution. EMBO J. 1990;9:4551–4554. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boles TC, White JH, Cozzarelli NR. Structure of plectonemically supercoiled DNA. J Mol Biol. 1990;213:931–951. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vologodskii A, Cozzarelli NR. Supercoiling, knotting, looping and other large-scale conformational properties of DNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1994;4:372–375. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bednar J, Furrer P, Stasiak A, Dubochet J, Egelman EH, Bates AD. The twist, writhe and overall shape of supercoiled DNA change during counterion-induced transition from a loosely to a tightly inter-wound superhelix. Possible implications for DNA structure in vivo . J Mol Biol. 1994;235:825–847. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyubchenko YL, Shlyakhtenko LS. Visualization of supercoiled DNA with atomic force microscopy in situ . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:496–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rybenkov VV, Vologodskii AV, Cozzarelli NR. The effect of ionic conditions on the conformations of supercoiled DNA. I. Sedimentation analysis. J Mol Biol. 1997;267:299–311. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vologodskii AV, Levene SD, Klenin KV, Frank-Kamenetskii M, Cozzarelli NR. Conformational and thermodynamic properties of supercoiled DNA. J Mol Biol. 1992;227:1224–1243. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90533-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keller W. Determination of the number of superhelical turns in simian virus 40 DNA by gel electrophoresis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:4876–4880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.12.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C-H, Mizusawa H, Kakefuda T. Unwinding of double-stranded DNA helix by dehydration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:2838–2842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JC. Circular DNA. In: Semlyen JA, editor. Cyclic Polymers. Essex, England: Elsevier; 1986. pp. 225–260. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vologodskii A. Circular DNA. Mol Biol. 1998;35:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasserman SA, Cozzarelli NR. Biochemical topology: application to DNA recombination and replication. Science. 1986;232:951–960. doi: 10.1126/science.3010458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vologodskii AV, Crisona NJ, Laurie B, Pieranski P, Katritch V, Dubochet J, Stasiak A. Sedimentation and electrophoretic migration of DNA knots and catenanes. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:1–3. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook DN, Ma D, Pon NG, Hearst JE. Dynamics of DNA supercoiling by transcription in Escherichia coli . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10603–10607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiNardo S, Voelkel KA, Sternglanz R, Reynolds AE, Wright A. Escherichia coli DNA topoisomerase I mutants have compensatory mutations in DNA gyrase genes. Cell. 1982;31:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang JC. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:635–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart L, Redinbo MR, Qiu X, Hol WGJ, Champoux JJ. A model for the mechanism of human topoisomerase I. Science. 1998;279:1534–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krasnow MA, Cozzarelli NR. Site-specific relaxation and recombination by the Tn3 resolvase: recognition of the DNA path between oriented res sites. Cell. 1983;32:1313–1324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson RC, Bruist MF. Intermediates in hin-mediated DNA inversion: a role for Fis and the recombinational enhancer in the strand exchange reaction. EMBO J. 1989;8:1581–1590. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]