Abstract

The DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 maintains DNA methylation patterns and genomic stability in several in vitro cell systems. Ablation of Dnmt1 in mouse embryos causes death at the post-gastrulation stage; however, the functions of Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in organogenesis remain unclear. Here, we report that Dnmt1 is crucial during perinatal intestinal development. Loss of Dnmt1 in intervillus progenitor cells causes global hypomethylation, DNA damage, premature differentiation, apoptosis and, consequently, loss of nascent villi. We further confirm the crucial role of Dnmt1 during crypt development using the in vitro organoid culture system, and illustrate a clear differential requirement for Dnmt1 in immature versus mature organoids. These results demonstrate an essential role for Dnmt1 in maintaining genomic stability during intestinal development and the establishment of intestinal crypts.

KEY WORDS: DNA damage response, DNA methylation, Intestinal epithelial development

Summary: Ablation of Dnmt1 in the mouse developing intestine leads to hypomethylation, DNA damage, premature differentiation and apoptosis. In intestinal organoid cultures, Dnmt1 is required for crypt formation.

INTRODUCTION

DNA methyltransferase 1 (Dnmt1) maintains DNA methylation following DNA replication, but little is known about its requirement for organ development. Previous studies of mice with global deletion of Dnmt1 failed to define the contribution of maintenance methylation during organogenesis because Dnmt1 null mice die shortly after gastrulation, at approximately embryonic day (E) 9.5 (Li et al., 1992). With the advent of Cre-loxP recombination technology and tissue-specific gene ablation, the role of Dnmt1 in organ development can now be addressed. For example, Dnmt1 has been ablated during neuronal development and shown to be essential for the survival of fetal mitotic neuroblasts (Fan et al., 2001). Dnmt1-ablated neuroblasts are 95% hypomethylated, and mice die just after birth due to respiratory defects, demonstrating a clear role for Dnmt1 in organ development and cellular differentiation (Fan et al., 2001). In the fetal pancreas, deletion of Dnmt1 causes a decrease in differentiated pancreatic cells with a concomitant increase in p53 levels, cell cycle arrest and progenitor cell apoptosis. However, this phenotype is dependent on direct binding of the Dnmt1 protein to the p53 (Trp53) locus, and was suggested to be caused by a DNA methylation-independent effect of Dnmt1 (Georgia et al., 2013). Thus, it remains unclear whether and how Dnmt1 and maintenance DNA methylation control different organs during development.

The intestinal epithelium is an especially tractable system for the study of stem cell maintenance and cellular differentiation. Important differences between the neonatal and adult intestinal epithelium led us to investigate the role of Dnmt1 during fetal gut development. Previous work had shown that Dnmt1 controls cellular differentiation in the mature intestinal epithelium, but is dispensable for organ maintenance and organismal survival in adult mice (Sheaffer et al., 2014). However, the intestinal stem cell niche does not develop until ∼1 week after birth in mice. During fetal gut development, proliferative progenitor cells become progressively restricted to the intervillus epithelium. Following birth, the proliferative intervillus regions invaginate into the underlying mesenchyme to form intestinal crypts. As a result, there is no defined stem cell population in the late fetal and perinatal intestinal epithelium. Furthermore, the mitotic index of intestinal epithelial progenitors is highest during the late embryonic and postnatal period, during which time the rate of cell production must dramatically exceed the rate of cell extrusion at the villus tip to allow for rapid villus growth (Al-Nafussi and Wright, 1982; Itzkovitz et al., 2012). This higher rate of cell turnover might indicate a distinct requirement for maintenance DNA methylation, as any delay in cell division would be expected to impair organ development.

Prior studies have failed to provide a clear explanation as to why loss of DNA methylation during organ development, such as in the brain, causes cell death (Fan et al., 2001). Rescue of the cell death phenotype in Dnmt1-deficient cultured fibroblasts via inactivation of Trp53 strongly suggests that the p53 pathway is partially responsible (Jackson-Grusby et al., 2001). In vitro studies of colorectal cancer (CRC) cell lines demonstrate that loss of DNA methylation results in genomic instability, DNA damage and mitotic arrest (Chen et al., 2007). Indeed, hypomethylation leads to increased mutation rates and reduced genomic stability (Chen et al., 1998), and in human CRC patients aberrant DNA methylation correlates with microsatellite instability (Ahuja et al., 1997). Therefore, we set out to determine whether loss of Dnmt1 causes genomic instability and intestinal development failure in the developing gut.

Using cell type-specific gene ablation, we discovered that Dnmt1 is essential for the maintenance of epithelial proliferation and nascent crypt development in the perinatal period. Without maintenance DNA methylation, the rapidly growing epithelium displays increased double-strand breakage, activation of the DNA damage response, and loss of progenitor cells due to both premature differentiation and apoptosis. We validate these results utilizing in vitro organoid cultures, demonstrating that Dnmt1 is required to establish organoids from the perinatal intestinal epithelium but is not essential for the maintenance of mature organoids derived from adult intestinal crypts. These data provide novel evidence for the role of DNA methylation in maintaining genomic stability during the development of highly proliferative tissues.

RESULTS

Dnmt1 is expressed in the proliferative zone of the embryonic and adult intestinal epithelium

To begin our study of the requirement for Dnmt1 in intestinal epithelial development, we first characterized the localization of Dnmt1 protein at different fetal and postnatal stages in the mouse. At E16.5, E18.5 and on postnatal day (P) 0, Dnmt1 protein was restricted to the proliferative intervillus regions, while in the adult intestinal epithelium Dnmt1 was localized to the proliferative crypt zone, as previously reported (supplementary material Fig. S1) (Sheaffer et al., 2014). Furthermore, prior RNA-Seq analysis of isolated cell populations from the adult intestinal epithelium confirms that crypt-based columnar intestinal stem cells (ISCs) express Dnmt1, whereas differentiated villus cells contain little to no Dnmt1 mRNA (Sheaffer et al., 2014).

Dnmt1 ablation causes decreased proliferation and genome hypomethylation in the perinatal intestinal epithelium

To investigate the function of Dnmt1 during murine gut development, we employed Cre-loxP recombination technology to specifically ablate Dnmt1 in the intestinal epithelium. The VillinCre transgene has been shown to cause activation of a Cre-dependent lacZ reporter as early as E12.5 (Madison et al., 2002), but analysis of late gestation Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre E18.5 embryos revealed highly mosaic ablation of Dnmt1 (supplementary material Fig. S2A-C) and no phenotypic effects were observed at this stage (data not shown). The mosaicism can be explained by the fact that the efficacy of Cre-mediated gene ablation varies depending on the design of the loxP-flanked target allele and its localization in chromatin (Baubonis and Sauer, 1993; Long and Rossi, 2009). Because Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutants were born at the expected Mendelian ratios, we set out to determine the potential requirement for Dnmt1 in the perinatal period.

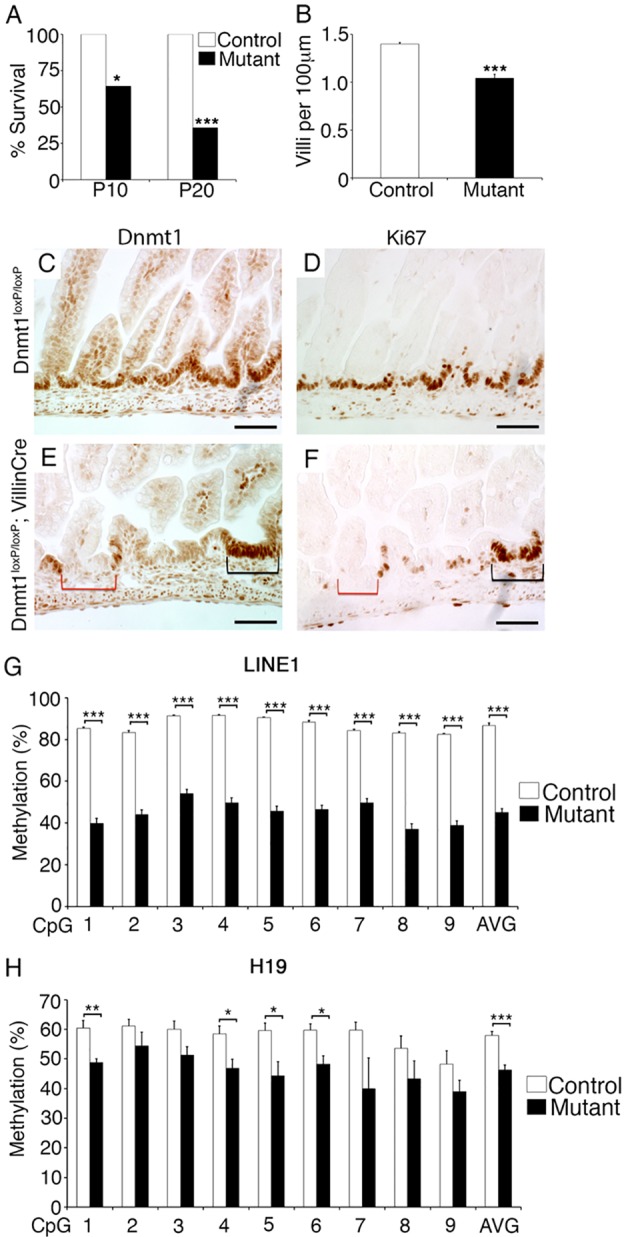

The majority of Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mice died within the first weeks of life, with only ∼35% surviving to weaning (Fig. 1A). The variable expressivity of the mutant phenotype is explained by the mosaicism of gene ablation in Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mice. In the first week of life, mutant mice often became runted and failed to compete with healthy littermates for maternal resources. We thus confined our analyses to P0 Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mice. Staining of mutant P0 intestine revealed that Dnmt1 protein was absent from 40-60% of progenitor cells (Fig. 1C,E; supplementary material Fig. S3A-C). Quantification of the villi present in the mutant neonatal intestinal epithelium showed a 25% decrease in villus number compared with littermate controls (Fig. 1B); the length of the villi, largely reflecting areas in which Dnmt1 had not been deleted, remained similar across genotypes (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Ablation of Dnmt1 in the developing intestinal epithelium causes reduced proliferation and DNA hypomethylation. (A) Only 35% of Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mouse mutants survive to P20 (n=14). (B) P0 mutants have significantly fewer villi than littermate controls (n=4). (C-F) Dnmt1 (C,E) and Ki67 (D,F) protein immunohistochemistry. P0 mutants display mosaic Dnmt1 ablation compared with controls (C,E). Absence of Dnmt1 (E, red bracket) corresponds to loss of proliferation in mutant progenitors as assessed by Ki67 staining of an adjacent section (F, red bracket). Dnmt1+ progenitors show similar proliferation in mutants (E,F, black brackets) compared with controls (D). (G) LINE1 repeat DNA methylation levels as assessed by bisulfite sequencing (n=4). Decreased LINE1 methylation indicates global demethylation in Dnmt1 mutant progenitor cells as compared with controls. (H) H19 ICR DNA methylation levels are decreased in Dnmt1 mutant progenitor cells relative to controls (n=4). Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-tailed Student's t-test. Scale bars: 50 μm.

To evaluate the possibility that the de novo DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b might compensate for Dnmt1 deficiency during gut development, we determined mRNA expression and protein localization of these two enzymes in Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre neonatal mutants and Dnmt1loxP/loxP littermate controls. The Dnmt1-deficient intestine did not display increased mRNA expression or altered localization of either de novo methyltransferase (supplementary material Fig. S3D-I). Thus, there is no compensatory upregulation of expression of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b in the Dnmt1-deficient gut epithelium.

The intestinal epithelium of surviving adult Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutants was predominantly Dnmt1+, indicating that ‘escaper cells’ that avoided Cre-mediated excision had repopulated the intestinal epithelium in its entirety (supplementary material Fig. S2D,E). The fact that the epithelium of surviving Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mice is made up primarily of Cre-escaper cells, despite the fact that the Villin promoter is active throughout adulthood, demonstrates that Dnmt1-deficient progenitor cells are at a severe disadvantage compared with Dnmt1+ Cre-escaper cells.

To investigate the possible causes for the observed postnatal lethality in Dnmt1-deficient mice, we first assessed epithelial cell proliferation. In control Dnmt1loxP/loxP littermates, all Dnmt1+ cells are Ki67+; we defined these proliferative areas in the intervillus regions of the neonatal intestine as the progenitor zone (Fig. 1C,D; supplementary material Fig. S4A,B). The Dnmt1-ablated epithelium displayed a striking reduction in the number of replicating cells as indicated by Ki67 staining, with many intervillus regions completely lacking proliferative cells (Fig. 1E,F; supplementary material Fig. S4C,D). Regions of the gut that retained Dnmt1 expression due to inefficient Cre-mediated gene ablation maintained epithelial proliferation, as expected (Fig. 1E,F). Furthermore, co-staining of Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutants and littermate controls demonstrated the substantial overlap of Dnmt1 and Ki67 protein localization (supplementary material Fig. S4). These results suggest that Dnmt1 is necessary to maintain the proliferation of epithelial progenitors during early postnatal intestinal development.

Next, we determined whether ablation of Dnmt1 resulted in loss of global DNA methylation in progenitor cells. The mosaicism of the Dnmt1 mutants precluded mechanistic analysis in bulk tissue extracts. To overcome this limitation, we isolated Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutant and Dnmt1loxP/+ control jejunal progenitor cells by laser capture microdissection (LCM). We stained serial sections for Ki67 to identify Dnmt1-ablated and Dnmt1+ areas corresponding to non-proliferative and proliferative progenitor zones, respectively, and used the adjacent serial sections for LCM. We isolated ∼10,000 cells per biological replicate for DNA methylation analysis (n=4 per group). LINE1 repetitive elements comprise 18% of the mouse genome (Waterston et al., 2002) and are a representative measure of genome-wide DNA methylation (Lane et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2004). Bisulfite sequencing of LINE1 elements demonstrated global demethylation of the mutant genome, exceeding 50% for several CpGs, confirming a dramatic loss of maintenance methylation (Fig. 1G). To further probe the DNA methylation status of mutant cells, we also bisulfite sequenced the imprinting control region (ICR) of the H19 locus. The H19 ICR is methylated on the paternal allele, meaning that H19 is only expressed from the maternally inherited copy (Tremblay et al., 1995). Targeted bisulfite sequencing demonstrated a consistent reduction of DNA methylation at the H19 ICR locus in mutants as compared with controls (Fig. 1H). These data are still likely to underestimate the degree of methylation loss, as even the most careful LCM resulted in the capture of 10% Dnmt1+ cells from mutant tissues, as indicated by our RNA-Seq analysis (see below; supplementary material Fig. S5B). Overall, these bisulfite sequencing results indicate a genome-wide reduction in DNA methylation.

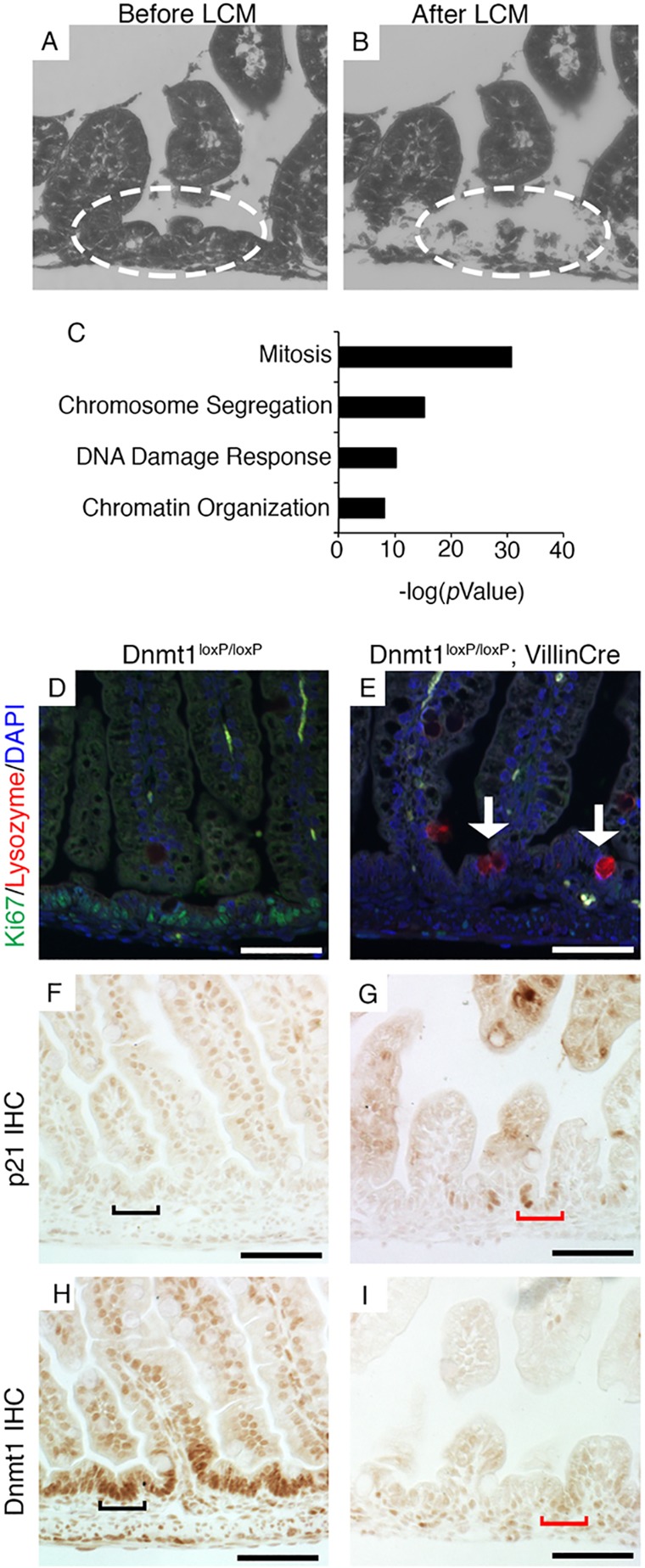

To determine the changes that Dnmt1 ablation causes in gene expression, we isolated Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutant and Dnmt1loxP/+ control progenitor cells using infrared (IR) laser capture (Fig. 2A,B). We isolated ∼10,000 cells from the proximal jejunum of each biological replicate and performed RNA-Seq to investigate the global transcriptome of intervillus progenitor cells. By combining the transcriptome data with our immunostaining analysis we were able to correlate gene expression changes with protein expression and localization alterations in the Dnmt1-ablated intestinal epithelium.

Fig. 2.

RNA-Seq analysis reveals decreased expression of crucial cell-cycle regulators in Dnmt1-deficient progenitor cells. (A,B) Collection of intervillus regions (encircled) before (A) and after (B) LCM. (C) DAVID GO analysis of genes with transcripts that are downregulated in P0 Dnmt1-deficient epithelial cells as determined by RNA-Seq. (D,E) Co-staining for Ki67 (green) and lysozyme (red) in control and Dnmt1 mutant intestine. A fraction of non-replicating Dnmt1– cells exhibits increased lysozyme protein levels (E, arrows), a marker for Paneth cell differentiation, relative to controls (D). (F,G) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showing that in controls p21 protein is confined to differentiated cells in the villus; in Dnmt1 mutants, expression is strikingly increased in intervillus regions (black bracket in F versus red bracket in G). (H,I) Dnmt1 immunohistochemistry on serial sections confirms Dnmt1 ablation in cells indicated by red brackets in G,I. Scale bars: 50 μm.

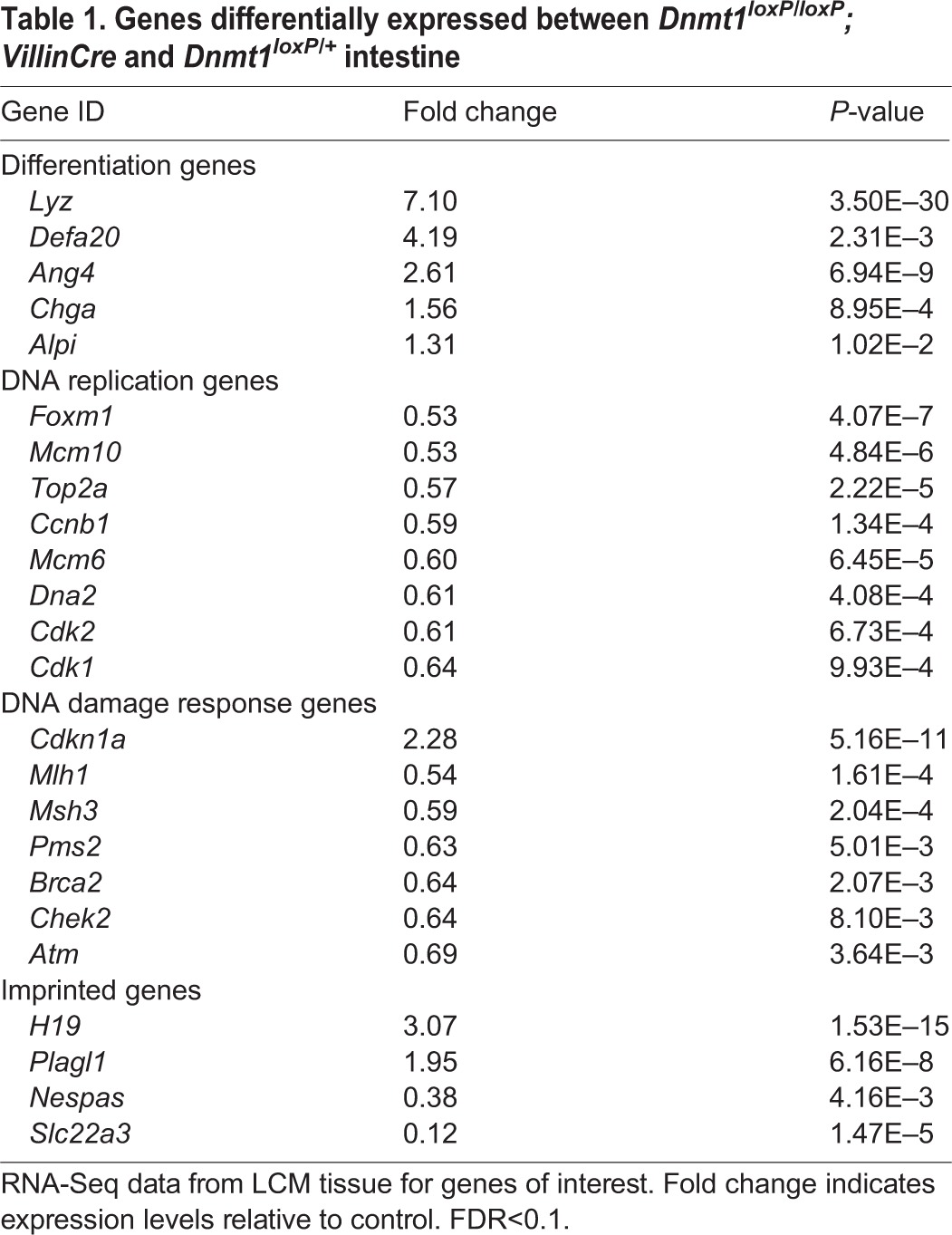

We found that Dnmt1 expression was reduced by ∼90% in our mutant samples, with the remaining Dnmt1 transcripts stemming from contaminating mesenchymal or Cre-escaper cells, as indicated by RNA-Seq analysis of Dnmt1 exon 5, which is excised upon Cre activation (Jackson-Grusby et al., 2001) (supplementary material Fig. S5B). By contrast, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b mRNA levels were unaffected, in agreement with our previous observations (supplementary material Fig. S5A). Several imprinted genes, including H19, were misregulated in mutant cells (Table 1), as expected. DAVID gene ontology (GO) analysis (Ashburner et al., 2000) did not define any specific terms for upregulated genes in our mutants, although we found increased expression of several differentiation-related genes (Table 1, Fig. 2C).

Table 1.

Genes differentially expressed between Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre and Dnmt1loxP/+ intestine

Partial induction of differentiation markers in Dnmt1-deficient progenitor zones

To test the possibility of premature differentiation of progenitor cells, we combined our RNA-Seq results with immunostaining for markers of differentiated cells present in the neonatal intestine, including enterocytes, goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells. These experiments did not reveal consistent differences in goblet cell differentiation and localization compared with age-matched controls (supplementary material Fig. S6M-P). There were small but statistically significant increases in alkaline phosphatase (Alpi) and chromogranin A (Chga) expression in mutant progenitors as determined by RNA-Seq (Table 1). However, the vast majority of mutant intervillus progenitor cells were neither Alpi+ nor Chga+ (supplementary material Fig. S6A-H), suggesting that premature differentiation is not the predominant cause of the Dnmt1 mutant phenotype.

Lysozyme+ Paneth cells do not appear in the normal mouse intestinal epithelium until crypt maturation begins at ∼P10, and drastically increase in number from P14 to P24 during crypt fission (Bry et al., 1994). Interestingly, lysozyme 1 and 2 (Lyz) expression was found to be markedly increased by RNA-Seq, immunofluorescent staining and qRT-PCR in Dnmt1-ablated intestinal progenitors relative to controls (Table 1, Fig. 2D,E; supplementary material Fig. S6I-L and Fig. S5C). Further analysis of RNA-Seq data showed that mutant progenitors exhibit increased expression of several Paneth cell-related genes, including Ang4, Defa20 and Pla2g2a (Table 1) (Bevins and Salzman, 2011). Thus, it appears that a fraction of mutant progenitors halt the cell cycle and prematurely differentiate into Paneth cells. However, our staining clearly indicates that only a small fraction of mutant progenitors are differentiated (Fig. 2D,E; supplementary material Fig. S6I-L), suggesting that other pathways, such as apoptosis, might also be activated. It is important to note that the perinatal progenitor zone is not a homogeneous stem cell population; indeed, there might be subpopulations of different progenitor cell types that are leading to the variable phenotypes we observe.

Dnmt1-ablated progenitor cells exhibit altered mRNA expression and DNA methylation of cell cycle and DNA damage response genes

GO analysis of downregulated genes indicated significant enrichment for the GO terms ‘cell division’, ‘DNA replication’ and ‘DNA damage response’ (Fig. 2C). A subset of these misexpressed genes, including Atm, Chek2, p21 (p21CIP1/WAF1 or Cdkn1a) and Mlh1, were confirmed in three independent LCM samples by qRT-PCR (supplementary material Fig. S5C,D). These results demonstrate that loss of Dnmt1 causes decreased expression of DNA damage response and cell cycle-related genes. Dnmt1 is known to play a crucial role in genomic stability, as ablation of Dnmt1 in cell lines can result in mitotic defects and G2/M arrest (Chen et al., 2007) or DNA replication errors and activation of the G1/S checkpoint (Knox et al., 2000; Unterberger et al., 2006). Additionally, loss of Dnmt1 in murine embryonic stem cells increases mitotic mutation rates (Chen et al., 1998), further pointing to the necessity of Dnmt1 in maintaining genomic integrity.

Our RNA-Seq data showed increased expression of the p53 target p21, which has an established role in activating the G1/S and G2/M phase checkpoints and inducing cellular senescence (Table 1; supplementary material Fig. S5D) (Bunz et al., 1998; Deng et al., 1995). p21 is often increased in response to DNA damage, and inhibits the transcription of many genes involved in cell cycle progression, leading to cell cycle arrest (Chang et al., 2000). Furthermore, p21 has been shown to be upregulated in response to loss of Dnmt1 in CRC cell lines (Chen et al., 2007), and several studies suggest that p21 expression is controlled by DNA methylation (Allan et al., 2000; Brenner et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2003). Immunostaining confirmed an increase in p21 protein levels in the Dnmt1-ablated intervillus epithelium compared with control progenitor cells, whereas p21 levels in postmitotic villus cells were comparable between the two genotypes (Fig. 2F-I). Taken together, our transcriptome and immunostaining analyses suggest that Dnmt1-deficient cells undergo cell cycle arrest.

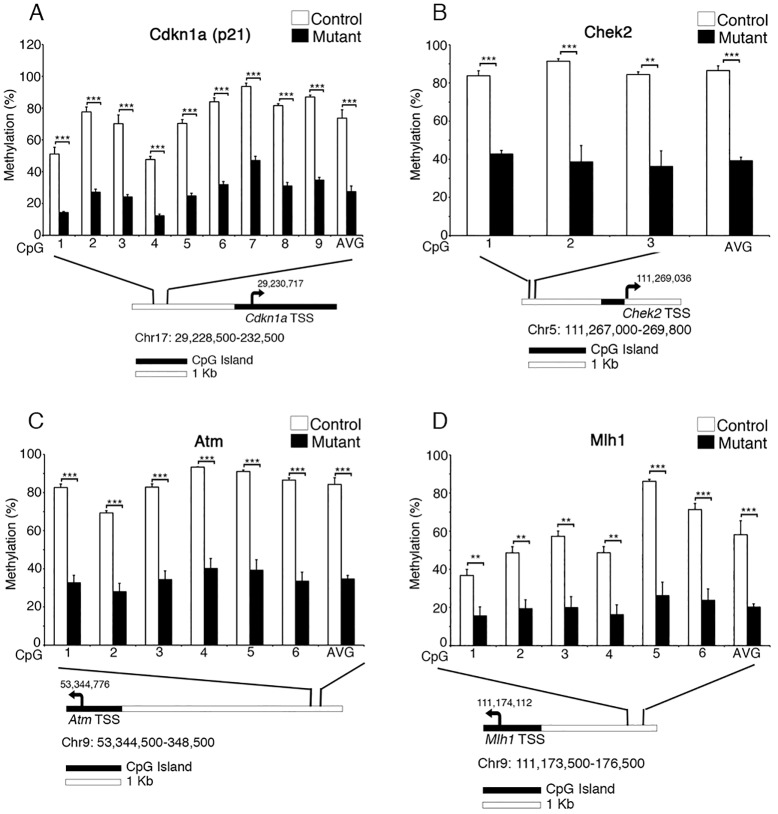

To further interrogate the extent of hypomethylation and the mechanism underlying the Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutant phenotype, we performed LCM and targeted bisulfite sequencing near the promoter regions of Atm, Chek2, p21 and Mlh1. We examined the methylation near the transcription start site (TSS) of these genes, but due to the presence of CpG islands in the proximal promoters of all four genes the baseline methylation levels in controls were only 0-5% (data not shown). Next, we analyzed low-density CpG clusters in putative regulatory regions 2-4 kb upstream of each TSS, and found that in all four cases the regions analyzed were significantly demethylated in the Dnmt1-deficient gut epithelium compared with the control (Fig. 3). The drastic loss of DNA methylation correlated with either increased or decreased mRNA levels, depending on the gene (Table 1; supplementary material Fig. S5C,D), suggesting that the upstream regulatory elements that we analyzed might function as enhancer (p21) or silencer (Chek2, Atm, Mlh1) regions (Jones and Takai, 2001).

Fig. 3.

Key DNA damage response genes are significantly demethylated in Dnmt1-ablated perinatal intestinal epithelial progenitors. Targeted bisulfite sequencing analysis of DNA damage response genes demonstrates significant demethylation upstream of p21 (Cdkn1a) (A), Chek2 (B), Atm (C) and Mlh1 (D) in P0 Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutants as compared with littermate controls. Beneath each bar chart is a diagram indicating the position of the transcription start site (TSS, arrow) and CpG islands relative to the regions sequenced. Each region is ∼2-4 kb upstream of the TSS. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-tailed Student's t-test.

Dnmt1 ablation results in increased DNA damage and apoptosis in the progenitor zone

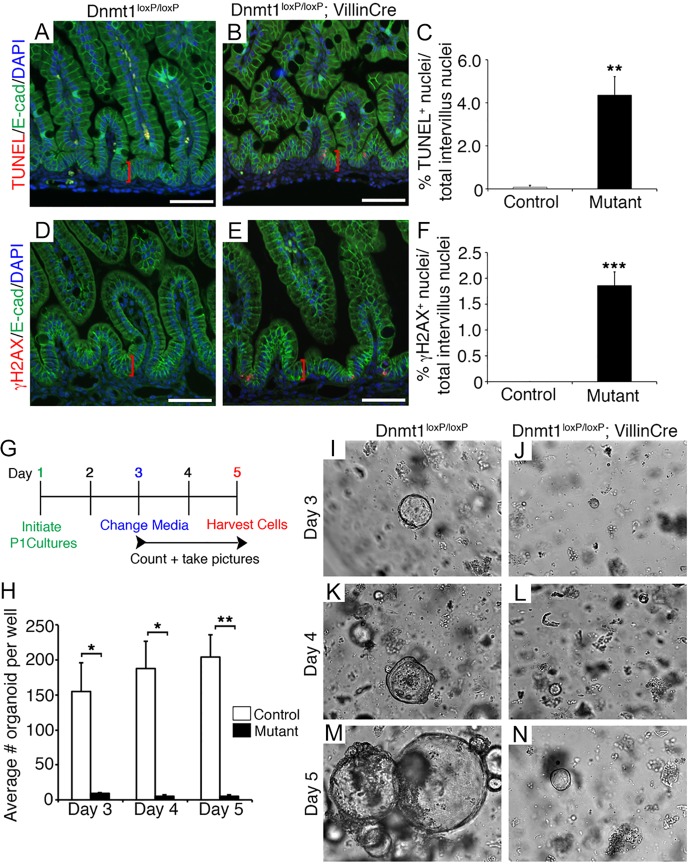

Given the activation of apoptosis reported in other models following loss of Dnmt1 (Chen et al., 2007; Jackson-Grusby et al., 2001; Li et al., 1992), we investigated the levels of apoptosis and DNA damage in mutant intestinal progenitors. In control progenitor regions, as expected, there were no apoptotic cells, as dying epithelial cells are normally confined to the villus tip (Fig. 4A) (Hall et al., 1994). Surprisingly, we found a significant number of apoptotic progenitor cells in mutant tissue (Fig. 4B), increased more than 50-fold relative to littermate controls (Fig. 4C). To evaluate if increased apoptosis was confined to Dnmt1-deficient, non-replicating intervillus cells, we co-stained to confirm loss of Ki67 in TUNEL+ areas (supplementary material Fig. S7A-F). These data demonstrate that ablation of Dnmt1 not only blocks proliferation, but also induces cell death in the progenitor compartment of the perinatal intestine. The variability in the amount of cells undergoing apoptosis at any one point in time reflects the stochastic cell death observed in the global Dnmt1 mutant embryos (Jackson-Grusby et al., 2001; Li et al., 1992), but might also be due to the action of Cre in progenitor cells at different points during development.

Fig. 4.

Ablation of Dnmt1 in the immature intestine results in loss of progenitor cells via apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. (A,B) TUNEL staining (red) demonstrates increased levels of apoptosis in P0 Dnmt1 mutant progenitor cells (A) as compared with the control (B). (C) TUNEL+ intervillus nuclei within 20 µm of the epithelial base (red brackets in A,B) were quantified in Dnmt1 mutants and littermate controls (n≥5). (D,E) Dnmt1 mutant progenitors (E) have increased DNA double-strand breaks compared with controls (D), as determined by γH2AX staining (red). (F) Quantification of γH2AX+ cell number as performed for TUNEL+ cells (n=4) within 20 µm of the epithelial base (red brackets in D,E). (A,B,D,E) E-cadherin immunostaining (green) to outline the epithelium and DAPI staining (blue) of nuclei. (G) Experimental scheme for P1 Dnmt1loxP/loxP (n=3) and Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre (n=2) intestinal organoid cultures. (H) Average number of organoids per well during the timecourse of the experiment. Organoids were grown in triplicate for each biological replicate. (I-N) Live phase-contrast imaging of Dnmt1loxP/loxP control and Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutant organoids on each day of culture. Surviving mutant organoids on day 5 persisted as very small cysts (N), whereas controls were considerably larger and exhibited budding activity (M). Phase-contrast images were all captured at 10× magnification. Error bars indicate s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-tailed (C,F) or one-tailed (H) Student's t-test. Scale bars: 50 μm.

We considered the possibility that apoptosis of Dnmt1-deficient progenitors might be the result of activation of the DNA damage response. Hypomethylation causes genomic instability and increased mutation rates, which can lead to activation of cell cycle checkpoints and the DNA damage response (Chen et al., 1998, 2007; Loughery et al., 2011). In addition, our own data demonstrate increased p21 levels in Dnmt1 mutant intervillus cells (Fig. 2F,G), which indicates cell cycle arrest. To assess activation of the DNA damage response in our mutants directly, we stained for γH2AX foci, which accumulate at double-strand DNA breaks (Fig. 4D,E; supplementary material Fig. S7G-L). We found a more than 1000-fold increase in γH2AX foci (P<0.001) in the mutant intervillus intestinal epithelium relative to littermate controls (Fig. 4F; compare red brackets in Fig. 4D with 4E). These results indicate that loss of Dnmt1 causes increased DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and subsequent cell death.

Adult Dnmt1-ablated crypt cells maintain methylation of DNA damage response genes

Given the opposing phenotypes that we describe above for the neonatal intestine versus that observed in mice with Dnmt1 ablation in the adult gut epithelium (Sheaffer et al., 2014), we also analyzed DNA methylation in the adult crypt epithelium. Global methylation of repetitive LINE1 elements and the imprinted H19 locus is reduced in adult mice with intestinal epithelial-specific Dnmt1 ablation to about the same extent as that seen in the perinatal ablation model described here (compare supplementary material Fig. S8A,B with Fig. 1G,H). Strikingly, however, p21 and Chek2 are not demethylated in the adult Dnmt1 ablation model (supplementary material Fig. S8C,D) and Atm is only significantly demethylated when comparing the entire gene region relative to control crypt epithelium (supplementary material Fig. S8E). Mlh1 is demethylated to a greater extent than the other genes analyzed (supplementary material Fig. S8F), indicating that Mlh1 is particularly sensitive to loss of Dnmt1. These results demonstrate that loss of Dnmt1 in the adult epithelium is not equivalent to the loss of Dnmt1 in the neonatal epithelium. We postulate that the differing requirement for Dnmt1 maintenance DNA methylation between the adult crypt compartment and the intervillus regions of the neonatal gut might be related to the more than 2-fold higher fractional proliferation rate of the latter compared with the former (supplementary material Fig. S9) (Itzkovitz et al., 2012). We next sought to determine the differential requirement for Dnmt1 in developing versus mature intestinal epithelial crypts in an in vitro organoid culture system.

Dnmt1 is required for establishing organoids in vitro

To demonstrate that Dnmt1 is required for organoid crypt culture from perinatal intestine, we employed EDTA disassociation to isolate intestinal epithelia from P1 Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutants and Dnmt1loxP/loxP littermate controls (Fig. 4G). We grew these perinatal organoid cultures in Matrigel with the ‘ENR’ (EGF, noggin, R-spondin) growth factor cocktail, allowing us to observe the development and maintenance of the perinatal intestinal epithelium in real time (Sato et al., 2009). We counted the number of organoids per well on days 3-5 of culture, and observed very few organoids (<10 per well) established from the Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre intestinal epithelium as compared with the robust establishment of organoids (>150 per well) from control gut (Fig. 4H). On day 4, we observed nascent buds in the control Dnmt1loxP/loxP organoids (Fig. 4K), but little sustained growth from the Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre organoids (Fig. 4L). By day 5, it was apparent that no healthy budding organoids were produced from the Dnmt1 mutant intestine, in contrast to the littermate controls (Fig. 4H,M,N). These results strongly support our in vivo data showing that Dnmt1 is essential to maintain perinatal intestinal progenitor cells.

To further probe the mechanism underlying the difference between the neonatal and adult Dnmt1 ablation phenotypes, we employed Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCreERT2 (Sheaffer et al., 2014) mice for in vitro organoid experiments. The VillinCreERT2 transgene allows temporal control of Dnmt1 ablation via the addition of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) to cells in culture. We hypothesized that Dnmt1 might be necessary for establishing the crypt compartment in neonatal mice but is not required for the maintenance and survival of mature crypts in adult mice. To test this hypothesis, we isolated crypts from adult Dnmt1loxP/loxP and Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCreERT2 mice and ablated Dnmt1 at two different time points during organoid growth. In one set of experiments, we added 4OHT during the first 2 days of culture, when organoids are growing but have not yet established buds and crypt structures (Sato et al., 2009) (supplementary material Fig. S10A). For the second set of experiments, we added 4OHT on days 5-7 of culture, after organoids had established proper crypt hierarchy in budding outgrowths (Sato et al., 2009) (supplementary material Fig. S11A).

In the ‘early’ experiments, in which Dnmt1 had been acutely ablated by addition of 4OHT, Dnmt1-deficient organoids failed to grow beyond small cyst-like structures, whereas control organoids began to exhibit buds by day 4 (supplementary material Fig. S10B-E). Dnmt1 immunostaining confirmed loss of the enzyme in 4OHT-treated VillinCreERT2+ organoids (supplementary material Fig. S10I). Addition of EdU to the medium 2 h prior to cell harvest allowed analysis of the replication rate. There were almost no EdU+ cells in the 4OHT-treated Dnmt1-ablated organoids, in contrast to controls in which replicating cells were abundant (supplementary material Fig. S10J-M). TUNEL staining demonstrated an increase in the frequency of TUNEL+ apoptotic nuclei in surviving Dnmt1-ablated organoids as compared with controls (supplementary material Fig. S10N-Q). Overall, the loss of Dnmt1 during the establishment of organoid cultures parallels the phenotype seen in the perinatal Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre mutant intestine, strongly suggesting a unique role for Dnmt1 in crypt development.

In stark contrast, the addition of 4OHT on days 5-7 of organoid culture, after large, multi-crypt organoids had formed, had little effect on the growth and replication of mature organoids (supplementary material Fig. S11B-E,J-M). We confirmed loss of Dnmt1 in 4OHT-treated VillinCreERT2+ organoids by immunohistochemistry (supplementary material Fig. S11F-I). Additionally, TUNEL staining demonstrated no increase in the apoptosis rate in the 4OHT-treated Dnmt1-ablated mature organoids (supplementary material Fig. S11N-Q). These results support our hypothesis that Dnmt1 performs unique functions in the developing intestinal epithelium, and plays a role in the establishment but not maintenance of crypts postnatally.

DISCUSSION

Taken together, our RNA-Seq, immunostaining and organoid data reveal a crucial role for Dnmt1 in maintaining DNA methylation patterns, genomic stability and progenitor cell status during intestinal development in vivo. We observed significant genome-wide DNA demethylation by targeted bisulfite sequencing of the LINE1 locus and the H19 ICR (Fig. 1G,H). Our RNA-Seq and immunostaining data demonstrate that Dnmt1-deficient progenitors express decreased levels of genes essential for mitosis and chromosome segregation (Table 1, Fig. 2C) and have increased rates of double-strand breaks (Fig. 4D-F). An increased rate of double-strand breaks during S phase of the cell cycle activates the G1/S checkpoint, mediated by p53 and p21. Indeed, increased p21 expression in the Dnmt1-deficient epithelium indicates that this checkpoint is active in mutant cells (Fig. 4G,H; supplementary material Fig. S5D). However, downstream targets of the DNA damage response pathway, including Atm, Chek2 and Mlh1, exhibit decreased expression by RNA-Seq (Table 1; supplementary material Fig. S5C), suggesting that Dnmt1-deficient intestinal progenitor cells are unable to activate the normal response to accumulated DNA damage. As a result, these Dnmt1-deficient progenitors undergo apoptosis, which leads to global loss of the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 4A-C). These findings are supported by previous studies implicating a requirement for Dnmt1 in DNA replication (Knox et al., 2000), the DNA damage response (Loughery et al., 2011; Mortusewicz et al., 2005; Unterberger et al., 2006) and cell cycle arrest (Chen et al., 2007).

Our results demonstrate an essential role for Dnmt1 in maintaining epithelial genomic integrity during perinatal intestinal development. Interestingly, when we ablated Dnmt1 in the adult intestinal epithelium using a tamoxifen-inducible VillinCreERT2 transgene, we did not observe a requirement for Dnmt1 in crypt cell survival, despite demethylation at the LINE1 locus (supplementary material Fig. S8A) (Sheaffer et al., 2014). These opposing phenotypes raise several questions. It is possible that, in the adult intestinal epithelium, loss of Dnmt1 protein is compensated by the de novo methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. More likely, the unique requirement for Dnmt1 in newborn mice is due to the significantly increased replication rate of neonatal progenitors compared with adult crypt cells (Itzkovitz et al., 2012). As shown in supplementary material Fig. S9, the neonatal intestinal epithelium displays twice the fractional proliferation rate than that of adult mice. Thus, we hypothesize that as the neonatal Dnmt1-ablated cells divide their DNA methylation levels are rapidly reduced, and Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b do not compensate for this loss. The high rate of proliferation in the neonatal intestine also distinguishes these findings concerning the developing intestine from studies of neuroblasts (Fan et al., 2001) or embryonic pancreas (Georgia et al., 2013).

Another possibility to explain the diverging phenotypes of adult and neonatal intestinal Dnmt1 ablation is that DNA methylation might not be crucial for cell survival and function in the mature crypt architecture. This explanation is supported by our organoid culture experiments (Fig. 4G-N; supplementary material Figs S10 and S11). The perinatal Dnmt1-deficient intestine fails to successfully produce organoids, in contrast to littermate controls (Fig. 4G-N). To test the differing requirements for Dnmt1 during organoid crypt development and maintenance, we used the inducible Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCreERT2 system (Sheaffer et al., 2014). When Dnmt1 was ablated before budding structures appear, organoids failed to thrive and eventually died (supplementary material Fig. S10). However, ablation of Dnmt1 after organoid buds and the ISC niche are established had little effect on the maintenance of replicating progenitors (supplementary material Fig. S11).

Several recently published studies analyze the differences between fetal progenitors and adult ISCs (Fordham et al., 2013; Mustata et al., 2013). Fordham and colleagues report that intestinal progenitor cell maturation correlates with increased Wnt signaling. In their study, Lgr5+ cells isolated from neonatal intestine produced budding organoids, with high expression of adult stem cell markers. Lgr5– cells isolated from the same neonatal tissue formed fetal enterospheres (FENs), which expressed low levels of Wnt factors and ISC markers and did not display budding activity. Our results strongly support the notion that adult and perinatal intestinal progenitors are not equivalent populations and have differential requirements for cell maintenance.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated an important role for Dnmt1 in establishing intestinal epithelial crypts following birth. We suggest that Dnmt1 is essential during the first few weeks of life to maintain genomic methylation patterns during this period of intense cellular proliferation and villus growth, and to prevent genome alterations that lead to progenitor cell death. Future research in this field should focus on the varying requirements for DNA methylation during development, particularly in supporting genomic stability and proliferation during organ development, in contrast to those necessary in adulthood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Dnmt1lox/lox mice were kindly provided by Rudolf Jaenisch (Jackson-Grusby et al., 2001), VillinCreERT2 mice by Sylvia Robine (El Marjou et al., 2004) and VillinCre mice from The Jackson Laboratory (Madison et al., 2002). Genotyping was performed by PCR analysis. For 2-h EdU analysis, we intraperitoneally injected 0.1 mg EdU (Invitrogen) for P0 mice and 1 mg EdU for 3-month-old adult mice. All procedures involving mice were conducted in accordance with approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols.

Histology, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Intestines were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was used to assess the global morphology of intestinal epithelial specimens. For all antibody staining, slides were dewaxed and antigen retrieval was performed using the 2100 Antigen-Retriever and R-Buffer A (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Standard immunohistochemistry staining was performed for Dnmt1 (Santa Cruz, 20701) and Ki67 (BD Pharmingen, 550609). p21 immunohistochemistry (BD Pharmingen, 556430) was performed as described previously (van de Wetering et al., 2002). Standard immunofluorescence procedures were performed with the following antibodies: Chga (Immunostar, 20085), Ki67 (BD Pharmingen, 550609), Dnmt3a (Santa Cruz, 20703), Dnmt3b (Imgenex, 184A), E-cadherin (BD Transduction Laboratories, 610181), lysozyme (Dako, A0099), Mucin2 (Santa Cruz, 15334) and γH2AX (Cell Signaling, 2577L). Co-staining was accomplished by sequential IHC and IF staining. Alkaline phosphatase staining was performed using NBT and BCIP (Boehringer). An immunofluorescent TUNEL assay (Roche) was used to assess apoptosis. For cell replication analysis, we used the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 555 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen). All microscopy was performed on a Nikon Eclipse 80i. For further details of staining procedures, including antibody dilutions, see the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Cell counting

For villi quantification, H&E-stained tissue sections were scanned at 10× using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices). Per biological replicate, villi were counted for ≥20 mm tissue, measured using ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012). For TUNEL and γH2AX quantification, 500 intervillus cells were counted at 20× for each biological replicate. Intervillus cells were defined as 20 μm from the base of the intestinal epithelium.

For EdU quantification, we harvested jejunum from five Dnmt1loxP/loxP 3-month-old adult mice and three litters of Dnmt1loxP/loxP P0 mice (four mice per litter). We defined the crypt-villus subunit as the epithelium lying between the peaks of two adjacent villi that share the same crypt. We counted the total number of EdU+ nuclei per crypt/intervillus region, and divided this number by the total number of nuclei per crypt-villus subunit. Per adult sample, we counted ∼8 crypt-villus subunits; per P0 sample, we counted ∼25 crypt-intervillus subunits.

Laser capture microdissection, RNA-Seq and mRNA expression analysis

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) was performed from unstained sections of paraffin-embedded, methacarn-fixed proximal jejunum for three controls and two mutants, as described previously (Miyoshi et al., 2012). Details of the identification of mutant versus non-mutant intervillus cells are provided in the supplementary Materials and Methods. Captured cells were collected onto CapSure HS LCM Caps (Applied Biosystems) and total cellular RNA was extracted using the PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems). RNA concentration and quality were assessed on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Total RNA isolated by LCM (2.3-33.3 ng per sample) was amplified using the Ovation RNA-Seq System V2 (NuGEN). 300 ng of each sonicated cDNA sample was used for RNA-Seq library preparation. cDNA sequencing libraries were completed using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs), Illumina multiplexing adaptors, and the NEBNext ChIP-Seq DNA Sample Prep Reagent Set 1 Kit (New England Biolabs). Single-read sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (100 bp reads).

Reads (a minimum of 25 million per sample, ∼80% unique mapped reads) were aligned to the mouse reference genome (NCBI build 37, mm9) using TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2012). TopHat was run with the University of California at Santa Cruz refFlat annotation file (GTF format) and the ‘–no-novel-juncs’ option to map reads only in the reference annotation. Cutdiff was used to calculate gene expression levels (Trapnell et al., 2012). mRNA levels were expressed in reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM). GO analysis was performed using DAVID (Ashburner et al., 2000). Cutdiff results were filtered by false discovery rate (FDR)<0.1 and separated into two categories: upregulated genes and downregulated genes. DAVID functional annotation analysis was performed separately for each gene set.

LCM, bisulfite conversion and Illumina MiSeq

In parallel experiments, DNA was isolated from mutant (n=4) and control (n=4) proximal jejunum using a Leica LMD7000 laser microdissection microscope and the Arcturus PicoPure DNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems). LCM-isolated DNA was bisulfite converted and purified using the Epitect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen). Template DNA was amplified using the HiFi HotStart Uracil+ ReadyMix PCR Kit (Kapa Biosystems). The LINE1 and H19 PCR assays were described previously (Lane et al., 2003; Samuel et al., 2009). Additional primer sets were designed using PyroMark software (Qiagen) and are listed in supplementary material Table S1. Adult Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCreERT2 mutant and Dnmt1loxP/loxP control crypt DNA were kindly provided by Sheaffer et al. (2014).

Sequencing libraries were made using the Ovation SP Ultralow Library System and Mondrian SP+ Workstation (NuGEN). Libraries were pooled at 8 nM and sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq Sequencer (MiSeq v2 Reagent Kit, 300 cycles paired-end). Converted sequence was aligned to the mouse genome (NCBI build 37, mm9) using BS Seeker (Chen et al., 2010).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from proximal jejunum of whole neonatal intestine using the Trizol RNA isolation protocol (Invitrogen). qRT-PCR was performed as described previously (Gupta et al., 2007). Primer sets are listed in supplementary material Table S2.

For confirmation of RNA-Seq results, proximal jejunal RNA samples were collected by LCM using the LMD7000 as described above. Approximately 10,000 cells were collected per sample. RNA was isolated and cDNA amplified using the protocols described for the RNA-Seq libraries. SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Agilent) was used in all qPCR reactions, and the fold change was calculated relative to the geometric mean of five reference genes (Tbp, Actb, Rplp0, Polr2b and B2m) using the ΔCT method as described previously (Vandesompele et al., 2002). Primer sets are provided in supplementary material Table S2.

Organoid culture

For neonatal Dnmt1loxP/loxP (n=3) and Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCre (n=2) organoid culture, duodenum and jejunum were opened longitudinally in cold PBS, cut into 10 mm pieces, and incubated in EDTA. Vigorous pipetting released the epithelia from the tissue, and cells were embedded in Matrigel (BD Biosciences) for cell culture as described previously (Sato et al., 2009). All organoids were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cell medium (Advanced DMEM/F12, Invitrogen) was supplemented with GlutaMax (1×), Hepes (10 mM), Pen/Strep (1×), N2 (1×), B27 (1×) (all Invitrogen) and N-acetylcysteine (1.25 mM; Sigma). The following growth factors were added to media: mouse EGF (50 ng/ml; Invitrogen), mouse noggin (100 ng/ml; Peprotech) and human R-spondin (1 μg/ml; Peprotech). For the first 2 days of neonatal organoid growth, cultures were also supplemented with Y-27632 (10 μM; Sigma) and CHIR-99021 (3 μM; Biovision). The medium was changed every other day.

Crypts were isolated from jejunum of 3-month-old Dnmt1loxP/loxP; VillinCreERT2 (n=4) and Dnmt1loxP/loxP (n=2) mice for organoid culture as described previously (Sato et al., 2009). The following growth factors were added to media: mouse EGF, mouse noggin, human R-spondin and CHIR-99021, as above. The medium was changed every other day. For VillinCreERT2 induction, 4OHT (Sigma, H7904) was added to organoid media at a final concentration of 100 nm (Sato et al., 2009). After 48 h, the 4OHT medium was removed and fresh medium was added to each well. At 100 nm, 4OHT was not detrimental to Dnmt1loxP/loxP control organoids at either time point (supplementary material Figs S10 and S11).

Two hours prior to organoid harvest, EdU (Invitrogen) was added to each well (10 µm). Organoids were harvested using cold PBS and were fixed in 4% PFA for 1 h at 4°C. Organoid pellets were suspended in agarose, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned for immunohistochemistry.

Data access

All RNA-Seq data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) under accession number GSE67363.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Marisa Bartolomei for helpful comments; Olga Smirnova, Joe Grubb and Shilpa Rao for RNA-Seq assistance; Dr Chris Krapp for the LINE1 methylation assay; Dr Kelli VanDussen for Arcturus PixCell IIe LCM training and assistance; and Dr John Seykora and Dr Stephen Prouty for Leica LCM training. We acknowledge the support of Dr Adam Bedenbaugh and the Morphology Core of the Penn Center for the Study of Digestive and Liver Diseases [grant P30-DK050306].

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants [R37-DK053839] to K.H.K. and a University of Pennsylvania Developmental Biology Training Grant [T32-HD07516] to E.N.E. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Author contributions

E.N.E. and K.H.K. planned experiments and prepared the manuscript. E.N.E. and K.L.S. performed experiments. J.S. analyzed RNA-Seq and bisulfite sequencing data. T.S.S. provided use of the Arcturus PixCell IIe LCM microscope. All authors have read, commented on and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.117341/-/DC1

References

- Ahuja N., Mohan A. L., Li Q., Stolker J. M., Herman J. G., Hamilton S. R., Baylin S. B. and Issa J. P. (1997). Association between CpG island methylation and microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 57, 3370-3374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan L. A., Duhig T., Read M. and Fried M. (2000). The p21(WAF1/CIP1) promoter is methylated in Rat-1 cells: stable restoration of p53-dependent p21(WAF1/CIP1) expression after transfection of a genomic clone containing the p21(WAF1/CIP1) gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1291-1298. 10.1128/MCB.20.4.1291-1298.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Nafussi A. I. and Wright N. A. (1982). Cell kinetics in the mouse small intestine during immediate postnatal life. Virchows Arch. B Cell Pathol. Incl. Mol. Pathol. 40, 51-62. 10.1007/BF02932850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J. M., Davis A. P., Dolinski K., Dwight S. S., Eppig J. T. et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25-29. 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baubonis W. and Sauer B. (1993). Genomic targeting with purified Cre recombinase. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2025-2029. 10.1093/nar/21.9.2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins C. L. and Salzman N. H. (2011). Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 356-368. 10.1038/nrmicro2546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner C., Deplus R., Didelot C., Loriot A., Viré E., De Smet C., Gutierrez A., Danovi D., Bernard D., Boon T. et al. (2005). Myc represses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferase corepressor. EMBO J. 24, 336-346. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bry L., Falk P., Huttner K., Ouellette A., Midtvedt T. and Gordon J. I. (1994). Paneth cell differentiation in the developing intestine of normal and transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 10335-10339. 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunz F., Dutriaux A., Lengauer C., Waldman T., Zhou S., Brown J. P., Sedivy J. M., Kinzler K. W. and Vogelstein B. (1998). Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science 282, 1497-1501. 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang B.-D., Watanabe K., Broude E. V., Fang J., Poole J. C., Kalinichenko T. V. and Roninson I. B. (2000). Effects of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 on cellular gene expression: implications for carcinogenesis, senescence, and age-related diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4291-4296. 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. Z., Pettersson U., Beard C., Jackson-Grusby L. and Jaenisch R. (1998). DNA hypomethylation leads to elevated mutation rates. Nature 395, 89-93. 10.1038/25779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Hevi S., Gay F., Tsujimoto N., He T., Zhang B., Ueda Y. and Li E. (2007). Complete inactivation of DNMT1 leads to mitotic catastrophe in human cancer cells. Nat. Genet. 39, 391-396. 10.1038/ng1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P.-Y., Cokus S. J. and Pellegrini M. (2010). BS Seeker: precise mapping for bisulfite sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 203 10.1186/1471-2105-11-203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng C., Zhang P., Harper J. W., Elledge S. J. and Leder P. (1995). Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell 82, 675-684. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R., Domrachev M. and Lash A. E. (2002). Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 207-210. 10.1093/nar/30.1.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marjou F., Janssen K.-P., Chang B. H.-J., Li M., Hindie V., Chan L., Louvard D., Chambon P., Metzger D. and Robine S. (2004). Tissue-specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis 39, 186-193. 10.1002/gene.20042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G., Beard C., Chen R. Z., Csankovszki G., Sun Y., Siniaia M., Biniszkiewicz D., Bates B., Lee P. P., Kuhn R. et al. (2001). DNA hypomethylation perturbs the function and survival of CNS neurons in postnatal animals. J. Neurosci. 21, 788-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordham R. P., Yui S., Hannan N. R. F., Soendergaard C., Madgwick A., Schweiger P. J., Nielsen O. H., Vallier L., Pedersen R. A., Nakamura T. et al. (2013). Transplantation of expanded fetal intestinal progenitors contributes to colon regeneration after injury. Cell Stem Cell 13, 734-744. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgia S., Kanji M. and Bhushan A. (2013). DNMT1 represses p53 to maintain progenitor cell survival during pancreatic organogenesis. Genes Dev. 27, 372-377. 10.1101/gad.207001.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. K., Gao N., Gorski R. K., White P., Hardy O. T., Rafiq K., Brestelli J. E., Chen G., Stoeckert C. J. and Kaestner K. H. (2007). Expansion of adult beta-cell mass in response to increased metabolic demand is dependent on HNF-4alpha. Genes Dev. 21, 756-769. 10.1101/gad.1535507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall P. A., Coates P. J., Ansari B. and Hopwood D. (1994). Regulation of cell number in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract: the importance of apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 107, 3569-3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzkovitz S., Blat I. C., Jacks T., Clevers H. and van Oudenaarden A. (2012). Optimality in the development of intestinal crypts. Cell 148, 608-619. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Grusby L., Beard C., Possemato R., Tudor M., Fambrough D., Csankovszki G., Dausman J., Lee P., Wilson C., Lander E. et al. (2001). Loss of genomic methylation causes p53-dependent apoptosis and epigenetic deregulation. Nat. Genet. 27, 31-39. 10.1038/83730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P. A. and Takai D. (2001). The role of DNA methylation in mammalian epigenetics. Science 293, 1068-1070. 10.1126/science.1063852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J. D., Araujo F. D., Bigey P., Slack A. D., Price G. B., Zannis-Hadjopoulos M. and Szyf M. (2000). Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase inhibits DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 17986-17990. 10.1074/jbc.C900894199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N., Dean W., Erhardt S., Hajkova P., Surani A., Walter J. and Reik W. (2003). Resistance of IAPs to methylation reprogramming may provide a mechanism for epigenetic inheritance in the mouse. Genesis 35, 88-93. 10.1002/gene.10168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E., Bestor T. H. and Jaenisch R. (1992). Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell 69, 915-926. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long M. A. and Rossi F. M. V. (2009). Silencing inhibits Cre-mediated recombination of the Z/AP and Z/EG reporters in adult cells. PLoS ONE 4, e5435 10.1371/journal.pone.0005435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughery J. E. P., Dunne P. D., O'Neill K. M., Meehan R. R., McDaid J. R. and Walsh C. P. (2011). DNMT1 deficiency triggers mismatch repair defects in human cells through depletion of repair protein levels in a process involving the DNA damage response. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 3241-3255. 10.1093/hmg/ddr236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison B. B., Dunbar L., Qiao X. T., Braunstein K., Braunstein E. and Gumucio D. L. (2002). Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33275-33283. 10.1074/jbc.M204935200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi H., Ajima R., Luo C. T., Yamaguchi T. P. and Stappenbeck T. S. (2012). Wnt5a potentiates TGF-β signaling to promote colonic crypt regeneration after tissue injury. Science 338, 108-113. 10.1126/science.1223821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortusewicz O., Schermelleh L., Walter J., Cardoso M. C. and Leonhardt H. (2005). Recruitment of DNA methyltransferase I to DNA repair sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8905-8909. 10.1073/pnas.0501034102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustata R. C., Vasile G., Fernandez-Vallone V., Strollo S., Lefort A., Libert F., Monteyne D., Pérez-Morga D., Vassart G. and Garcia M.-I. (2013). Identification of Lgr5-independent spheroid-generating progenitors of the mouse fetal intestinal epithelium. Cell Rep. 5, 421-432. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel M. S., Suzuki H., Buchert M., Putoczki T. L., Tebbutt N. C., Lundgren-May T., Christou A., Inglese M., Toyota M., Heath J. K. et al. (2009). Elevated Dnmt3a activity promotes polyposis in Apc(Min) mice by relaxing extracellular restraints on Wnt signaling. Gastroenterology 137, 902-913.e11. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T., Vries R. G., Snippert H. J., van de Wetering M., Barker N., Stange D. E., van Es J. H., Abo A., Kujala P., Peters P. J. et al. (2009). Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature 459, 262-265. 10.1038/nature07935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C. A., Rasband W. S. and Eliceiri K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671-675. 10.1038/nmeth.2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheaffer K. L., Kim R., Aoki R., Elliott E. N., Schug J., Burger L., Schübeler D. and Kaestner K. H. (2014). DNA methylation is required for the control of stem cell differentiation in the small intestine. Genes Dev. 28, 652-664. 10.1101/gad.230318.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D. R., Pimentel H., Salzberg S. L., Rinn J. L. and Pachter L. (2012). Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7, 562-578. 10.1038/nprot.2012.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay K. D., Saam J. R., Ingram R. S., Tilghman S. M. and Bartolomei M. S. (1995). A paternal-specific methylation imprint marks the alleles of the mouse H19 gene. Nat. Genet. 9, 407-413. 10.1038/ng0495-407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterberger A., Andrews S. D., Weaver I. C. G. and Szyf M. (2006). DNA methyltransferase 1 knockdown activates a replication stress checkpoint. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 7575-7586. 10.1128/MCB.01887-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wetering M., Sancho E., Verweij C., de Lau W., Oving I., Hurlstone A., van der Horn K., Batlle E., Coudreuse D., Haramis A.-P. et al. (2002). The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell 111, 241-250. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01014-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A. and Speleman F. (2002). Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3, research0034-research0034.11. 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterston R. H., Lindblad-Toh K., Birney E., Rogers J., Abril J. F., Agarwal P., Agarwala R., Ainscough R., Alexandersson M., An P. et al. (2002). Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520-562. 10.1038/nature01262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A. S., Estécio M. R. H., Doshi K., Kondo Y., Tajara E. H. and Issa J.-P. J. (2004). A simple method for estimating global DNA methylation using bisulfite PCR of repetitive DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, e38 10.1093/nar/gnh032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W.-G., Srinivasan K., Dai Z., Duan W., Druhan L. J., Ding H., Yee L., Villalona-Calero M. A., Plass C. and Otterson G. A. (2003). Methylation of adjacent CpG sites affects Sp1/Sp3 binding and activity in the p21(Cip1) promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 4056-4065. 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4056-4065.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.