Abstract

New strategies for the prevention or treatment of infections are required. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effects of antimicrobial peptides and bacteriocins isolated from Lactobacillus plantarum on growth and biofilm formation of three common pathogenic microbes. The antibacterial properties of the antimicrobial peptide Tet213 and bacteriocins were tested by the disc diffusion method. Tet213 and bacteriocins showed inhibitory effects on biofilm formation for the three organisms, as observed by fluorescence microscopy. Furthermore, Tet213 and the bacteriocins all showed antimicrobial activity against the three bacterial species, with Tet213 having a greater inhibitory effect on S. aureus than the bacteriocins (P < 0.05), while the bacteriocins showed stronger antimicrobial activity against S. sanguis (P < 0.05).

Keywords: Antimicrobial activity, antimicrobial peptide, bacteriocin, biofilm

Introduction

For many years traditional antibiotics have played an important role in the treatment of infections [1]. However, the extensive use of these “traditional antibiotics” has created significant problems [2]. Many currently used antibiotics are no longer effective at inhibiting or killing certain pathogens. More and more research has focused on the development of new classes of antibiotics, such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) or other new compounds with novel mechanisms of action or spectrum of activity [3,4]. These new antibiotics may hold promise for treating refractory infections and inflammation [5].

Lactobacilli are known for their production of antimicrobial compounds, including bacteriocins and bacteriocin like peptides [6,7]. Most of the bacteriocins produced by Lactobacillus species are small, thermally stable proteins, known as type II bacteriocins [8]. These compounds can induce rupture of the cell membrane, causing leakage of cell contents and playing a role in sterilization [9]. Bacteriocins isolated from Lactobacillus species have also been reported to have significant antibacterial effects on common clinical pathogens in vitro [10,11]. However, a comparison of the antibacterial effects of both AMPs and bacteriocins has been rarely reported.

The objective of this study was to compare the antibacterial effect of an antimicrobial peptide (Tet-213) and bacteriocins isolated from Lactobacillus plantarum on Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus sanguis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the comparison of the antibacterial effect of an antimicrobial peptide and bacteriocins isolated from Lactobacillus plantarum on three kinds of pathogenic bacteria.

Materials and methods

Strains and culture conditions

Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014 was purchased from ATCC. The three strains used for the experiments were P. aeruginosa ATCC 90271, S. sanguis ATCC10556 and S. aureus ATCC 25923. The three strains were incubated on Columbia sheep blood agar (BioMérieux, France) at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions (6% CO2) for 24 h. The in vitro experiments were performed in Brian Heart Infusion (BHI) broth and Brian Heart Infusion agar (Oxoid, UK).

Peptides

Tet-213 (amino acid sequence: KRWW KWWRRC) was synthesized by Shanghai Apeptide Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China) (~94% purity by HPLC).

Production of culture supernatants

Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014 was grown in MRS broth at 37°C for 24 h. Supernatants were harvested by centrifugation (7000 g for 10 min), adjusted to pH 6.5, treated with catalase (5 mg/ml), to eliminate the inhibitory activity due to hydrogen peroxide, and filtered through a 0.22 µm pore size filter (Millipore, USA).

Isolation of bacteriocins

The bacteriocins from Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 8014 was isolated according to the methods by Lash et al [12]. In brief, 100 ml culture supernatants of L. plantarum were precipitated using 60 g ammonium sulfate. The crude precipitate was centrifuged for 20 min at 10,000 × g at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4. The resuspended pellet was concentrated by using an Amicon Ultra-4 Centrifugal Filter device (Millipore, USA) with a molecular weight (MW) cut-off of 10 kDa [13] to a final volume of 0.5 ml at 4°C and then the final suspension was concentrated by freeze-drying [14] and stored at 4°C.

Antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activity of Tet-213 and bacteriocins were tested by the agar disc diffusion method on BHI agar according to the guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) [15]. The test strains P. aeruginosa ATCC 90271, S. sanguis ATCC10556 and S. aureus ATCC 25923 used in this study were the fully sequenced strains. The following antibiotics were tested: Tet213 30 μg, bacteriocin 30 μg, ceftazidime 30 μg. Disks were incubated for 24 h at 35°C. Inhibition zone diameters for antimicrobial peptide and bacteriocin were noted and compared.

Inhibitory effects of the test compounds on biofilm formation in the three test strains

Biofilm formation was conducted according to previously published methods [16]. In detail, the S. aureus, S. sanguis and P. aeruginosa cultures were incubated in BHI broth and grown under microaerophilic conditions for 24 h at 37°C. The cells were washed three times with PBS and then adjusted with PBS to 0.5 McFarland standard (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) by using a Densicheck (BioMérieux, France) [17]. Individual Petri dishes were filled with 10 ml of BHI broth, and a sterile coverslip (18 mm diameter) was added to each dish. 100 µl of individual bacterial suspensions were mixed with 500 µl of antimicrobial peptide or bacteriocin suspensions (100 µg/ml) in the dishes. PBS was used as a control. All Petri dishes were incubated under microaerophilic conditions at 37°C for 24 h.

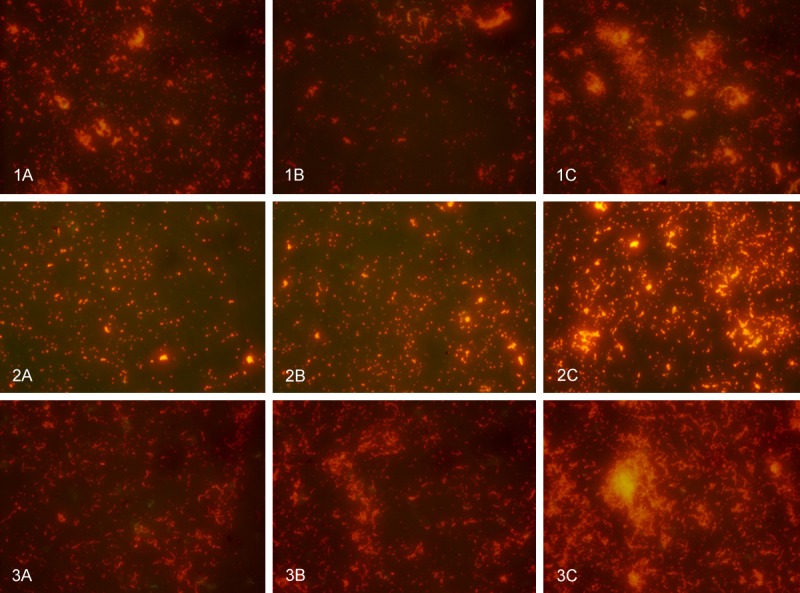

After 24 h of biofilm formation, each coverslip was washed with 10 ml of PBS to remove unattached cells. After fixation with 1% formaldehyde, each coverslip was stained with a 0.01% acridine orange solution [18] (Sigma, USA) and then observed with a Nikon 80i microscope (using the green fluorescence channel). Image analysis was conducted by Image-Pro Plus 4.5 software (Media Cybernetics, USA) [19].

Statistics

All tests were performed in triplicate. SPSS 14.0 software for Windows was used for data analysis. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed first, and then data comparisons were performed with paired t-test.

Results

Antimicrobial activity

Results for the antimicrobial activity of Tet213 and bacteriocins in the disc diffusion assay are shown in Table 1. Tet213 and the bacteriocins all showed greater antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and S. sanguis compared with the control (P < 0.05). For S. aureus, Tet213 showed a greater inhibitory effect compared with the bacteriocins (P < 0.05) while the bacteriocins showed stronger antimicrobial activity against S. sanguis (P < 0.05). Both Tet213 and the bacteriocins showed no significant inhibitory effect on the growth of P. aeruginosa (P > 0.05). The inhibition zone tests are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Tet213 and bacteriocin zone diameters from S. aureus, S. sanguis and P. aeruginosa using a 30 µg disk read at 24 h of incubation (means ± SD)

| Bacterial species | P. aeruginosa | S. aureus | S. sanguis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tet213 | 12.5 ± 3.1a | 11.7 ± 1.1a,b | 17.5 ± 3.5a,b |

| Bacteriocin | 17.5 ± 2.9a | 18.5 ± 4.4a | 10.3 ± 1.7a |

| Tinidazole (control) | 7.9 ± 1.9 | 7.6 ± 2.4 | 8.7 ± 1.6 |

means P < 0.05 compared with bacteriocin;

means P < 0.05 compared with control.

Figure 1.

Response of Tet213 and bacteriocin with disks containing 30 mg of Tet213 (1) and 30 mg of bacteriocin (2) and 30 mg of ceftazidime (C). A: P. aeruginosa, B: S. aureus and C: S. sanguis.

Inhibitory effects on biofilm formation

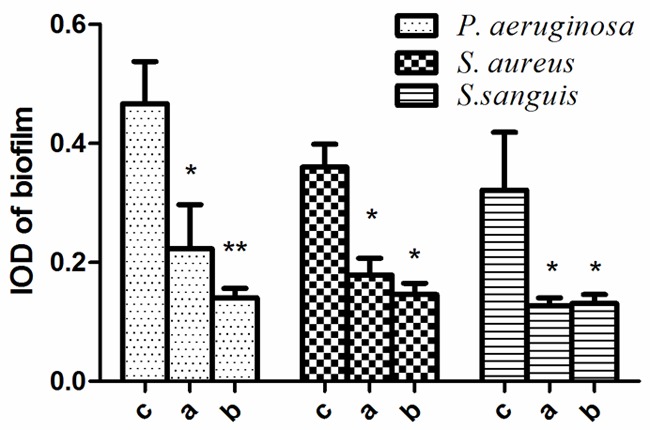

Individually, Tet213 and the bacteriocins showed strong inhibitory effects on biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and S. sanguis (P < 0.05, Figure 2), but there was no significant difference in biofilm formation of these strains, when the effects of Tet213 and the bacteriocins were compared (P > 0.05) (Figure 1). Fluorescent images of these biofilms are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

The integrated optical density (IOD) of P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and S. sanguis grown in the presence of Tet213 and bacteriocins. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. A: Antimicrobial peptide; B: Bacteriocins; C: Control.

Figure 3.

The effect of antimicrobial peptide and bacteriocin on P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and S. sanguis biofilm formation (stained with acridine orange): (1) P. aeruginosa, (2) S. aureus, (3) S. sanguis, A: Antimicrobial peptide; B: Bacteriocins; C: Control.

Discussion

AMPs have a wide antimicrobial spectrum, including activity against many multi-drug resistant bacteria [20]. Furthermore, resistance does not developed during bacterial killing, making these compounds attractive candidates for drug development [21,22]. Our results showed that Tet213 had strong antibacterial activity against P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and S. sanguis, which agree closely with previous experimental results [23-25].

AMPs and bacteriocins from lactobacilli are known to be more active against Gram-positive than Gram-negative bacteria [26]. Our results, however, showed that there was no obvious difference in antibacterial activity against the three strains. Bacteriocins isolated from Lactobacillus species usually have a broad antimicrobial spectrum [27] and can inhibit common pathogenic bacteria that are responsible for food spoilage or human diseases. S. aureus can cause suppurative infections, and also can produce enterotoxins, which result in food poisoning [28]. P. aeruginosa can cause wound infections after surgery [29] and is especially likely to develop resistance [30]. S. sanguis causes endocarditis [31], an infection where bacterial biofilms play a prominent role and are often responsible for treatment failure [32]. Our research shows that Tet213 and bacteriocins all have good inhibitory effects on biofilm formation, which indicates that Tet213 and bacteriocins may be effective in treating the above mentioned diseases. In this study, there was little difference in the antimicrobial activity between Tet213 and bacteriocins, while differences in inhibitory effects of these compounds on biofilm formation were not obvious. However, our studies were based on a small number of test strains and in future experiments, we will utilise a larger panel of experimental bacteria.

In conclusion, an antimicrobial peptide and bacteriocins isolated from Lactobacillus plantarum were able to inhibit the growth and biofilm formation of S. aureus, S. sanguis and P. aeruginosa. Their antibacterial activity against S. aureus, S. sanguis and P. aeruginosa is slightly different, suggesting that these compounds may be one promising way to control infectious diseases.

Acknowledgements

This research is financially supported by Project of Changzhou Applied Basic Research Guidance (Grant No. CY20119010) and Project of Scientific Research of Nanjing medical university (Grant No. 2011NJMU082).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Sang Y, Blecha F. Antimicrobial peptides and bacteriocins: alternatives to traditional antibiotics. Anim Health Res Rev. 2008;9:227–235. doi: 10.1017/S1466252308001497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Timurkaynak F, Can F, Azap ÖK, Demirbilek M, Arslan H, Karaman SÖ. In vitro activities of non-traditional antimicrobials alone or in combination against multidrug-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from intensive care units. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;27:224–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright GD. Antibiotics: a new hope. Chem Biol. 2012;19:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piddock LJ. The crisis of no new antibiotics-what is the way forward? Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:249–253. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spellberg B, Bartlett JG, Gilbert DN. The future of antibiotics and resistance. Zasloff Michael. 2013;368:299–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Todorov SD, Rachman C, Fourrier A, Dicks LM, Van Reenen CA, Prévost H, Dousset X. Characterization of a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus sakei R1333 isolated from smoked salmon. Anaerobe. 2011;17:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messaoudi S, Manai M, Kergourlay G, Prévost H, Connil N, Chobert JM, Dousset X. Lactobacillus salivarius: Bacteriocin and probiotic activity. Food Microbiol. 2013;36:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corr SC, Li Y, Riedel CU, O’Toole PW, Hill C, Gahan CG. Bacteriocin production as a mechanism for the antiinfective activity of Lactobacillus salivarius UCC118. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7617–7621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700440104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garneau S, Martin NI, Vederas JC. Two-peptide bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. Biochimie. 2002;84:577–592. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todorov S, Dicks L. Lactobacillus plantarum isolated from molasses produces bacteriocins active against Gram-negative bacteria. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2005;36:318–326. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svetoch EA, Eruslanov BV, Levchuk VP, Perelygin VV, Mitsevich EV, Mitsevich IP, Stepanshin J, Dyatlov I, Seal BS, Stern NJ. Isolation of Lactobacillus salivarius 1077 (NRRL B-50053) and characterization of its bacteriocin and spectra of antimicrobial activity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2749–54. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02481-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lash BW, Mysliwiec TH, Gourama H. Detection and partial characterization of a broad-range bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum(ATCC 8014) Food Microbiol. 2005;22:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christopher AB, Arndt A, Cugini C, Davey ME. A streptococcal effector protein that inhibits Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm development. Microbiol (Reading Engl) 2010;156:3469–3477. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042671-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardiner G, O’sullivan E, Kelly J, Auty M, Fitzgerald G, Collins J, Ross R, Stanton C. Comparative survival rates of human-derived probioticlactobacillus paracasei and l. salivariusstrains during heat treatment and spray drying. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2605–2612. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2605-2612.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewus CB, Kaiser A, Montville TJ. Inhibition of food-borne bacterial pathogens by bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria isolated from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1683–1688. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.6.1683-1688.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.You J, Xue X, Cao L, Lu X, Wang J, Zhang L, Zhou S. Inhibition of Vibrio biofilm formation by a marine actinomycete strain A66. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:1137–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin X, Chen X, Chen Y, Jiang W, Chen H. The effect of five probiotic lactobacilli strains on the growth and biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans. Oral Dis. 2015;21:e128–34. doi: 10.1111/odi.12257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zacheus OM, Iivanainen EK, Nissinen TK, Lehtola MJ, Martikainen PJ. Bacterial biofilm formation on polyvinyl chloride, polyethylene and stainless steel exposed to ozonated water. Water Res. 2000;34:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton J, Greenberg E. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Severina E, Severin A, Tomasz A. Antibacterial efficacy of nisin against multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. J Anti Chemothe. 1998;41:341–347. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassan M, Kjos M, Nes I, Diep D, Lotfipour F. Natural antimicrobial peptides from bacteria: characteristics and potential applications to fight against antibiotic resistance. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:723–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wimley WC, Hristova K. Antimicrobial peptides: successes, challenges and unanswered questions. J Membr Biol. 2011;239:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9343-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra NN, McKinnell J, Yeaman MR, Rubio A, Nast CC, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Bayer AS. In vitro cross-resistance to daptomycin and host defense cationic antimicrobial peptides in clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:4012–4018. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00223-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Z, Vasil AI, Gera L, Vasil ML, Hodges RS. Rational design of α-helical antimicrobial peptides to target Gram-negative pathogens, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: utilization of charge, ‘specificity determinants,’ total hydrophobicity, hydrophobe type and location as design parameters to improve the therapeutic ratio. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2011;77:225–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Takada H, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity. 1999;11:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chateau N, Castellanos I, Deschamps A. Distribution of pathogen inhibition in the Lactobacillus isolates of a commercial probiotic consortium. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb02993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simova E, Beshkova D, Dimitrov ZP. Characterization and antimicrobial spectrum of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria isolated from traditional Bulgarian dairy products. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;106:692–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Loir Y, Baron F, Gautier M. Staphylococcus aureus and food poisoning. Genet Mol Res. 2003;2:63–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tosh PK, Disbot M, Duffy JM, Boom ML, Heseltine G, Srinivasan A, Gould CV, Berríos-Torres SI. Outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa surgical site infections after arthroscopic procedures: Texas, 2009. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:1179–1186. doi: 10.1086/662712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riera E, Cabot G, Mulet X, García-Castillo M, del Campo R, Juan C, Cantón R, Oliver A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa carbapenem resistance mechanisms in Spain: impact on the activity of imipenem, meropenem and doripenem. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2022–2027. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowrance J, Baddour L, Simpson W. The role of fibronectin binding in the rat model of experimental endocarditis caused by Streptococcus sanguis. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:7. doi: 10.1172/JCI114717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otto M. Staphylococcal infections: mechanisms of biofilm maturation and detachment as critical determinants of pathogenicity*. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:175–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042711-140023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]