Abstract

The spatial regulation of protein translation is an efficient way to create functional and structural asymmetries in cells. Recent research has furthered our understanding of how individual cells spatially organize protein synthesis, by applying innovative technology to characterize the relationship between mRNAs and their regulatory proteins, single-mRNA trafficking dynamics, physiological effects of abrogating mRNA localization in vivo and for endogenous mRNA labelling. The implementation of new imaging technologies has yielded valuable information on mRNA localization, for example, by observing single molecules in tissues. The emerging movements and localization patterns of mRNAs in morphologically distinct unicellular organisms and in neurons have illuminated shared and specialized mechanisms of mRNA localization, and this information is complemented by transgenic and biochemical techniques that reveal the biological consequences of mRNA mislocalization.

Introduction

Spatial segregation of protein synthesis in cells involves the positioning of mRNAs according to where their protein products are required, and results in local or compartmentalized gene expression. This asymmetrical distribution of mRNA, termed mRNA localization, can be more thermodynamically efficient than transporting proteins because fewer mRNA molecules need to be mobilized. It is also possible that spatially controlling translation offers finer control of local protein activity1 as opposed to preventing ectopic activity by other means. Furthermore, proteins synthesized locally are structurally and functionally distinct from transported proteins: they are more likely to contain domains that promote protein–protein interactions, and are subject to tighter regulation of expression and to more post-translational modifications than proteins that are not translated locally1.

mRNA localization can occur during specific stages in development, and distinguish cell and tissue phenotypes, activities and communication. Recent advances in single-molecule RNA imaging in live cells and whole organisms, as well as advances in genome-wide analyses of RNA–protein interactions, have improved our understanding of how mRNA localization to subcellular regions is regulated and accomplished on the single-molecule level. Early visualization experiments of asymmetric mRNA distribution in model systems — such as ascidian eggs2, fibroblasts3, Xenopus laevis oocytes4, Drosophila melanogaster embryos5, Saccharomyces cerevisiae6 and neurons7 revealed that dynamic cellular and subcellular mRNA localization is a conserved phenomenon. More recently, it was shown that during D. melanogaster development up to 70% of mRNAs are expressed in distinct spatial patterns8. Similarly, half of the neuronal mRNA species in the rat hippocampus are enriched in axons and dendrites compared with the cell body (the soma)9. Early work uncovered fundamental regulatory mechanisms underlying mRNA localization such as the importance of the cytoskeleton10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and of conservedcis-acting sequences15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Identification of mRNA elements responsible for localization preceded the determination of the RNA-binding proteins (RBPs)22, 23, 24 and molecular motors that mediate transport on the cytoskeleton25. More recently, model systems such as fibroblasts, neurons, budding yeast, D. melanogaster oocytes and embryos, and X. laevisoocytes have been used to investigate the kinetics and regulation of mRNA movement and localization26, as well as the role of mRNA localization in many aspects of life, such as cell migration, development, neural signalling and disease.

In this Review, we first provide an overview of these cutting-edge techniques, followed by a discussion of the mRNA properties, protein complexes and the cellular mechanisms that mediate mRNA localization. We then discuss how the visualization of mRNAs has yielded valuable information on the dynamic behaviour of mRNAs and their transport partners in various cellular processes, with a particular emphasis on mRNA cytoplasmic localization in the unicellular organism S. cerevisiae and in neurons.

Visualizing the message

Optical techniques have been frequently used to investigate how mRNA localization is accomplished and to identify the factors involved. Below, we discuss methods that are particularly useful for investigating mRNA distribution and dynamics, and highlight discoveries that were made using these approaches.

In situ hybridization techniques

In situ hybridization (ISH) is a method by which labelled, short nucleic acid probes are hybridized to RNA or DNA in fixed cells or tissues. ISH with biotinylated or radioactive probes enabled the first visualization of asymmetrically distributed poly(A), histone and actin mRNAs in muscle cells27 and ascidian eggs2. The technical variables of ISH were quantitatively optimized three decades ago28. However, the technique has since improved owing to technological advances, which allowed the development of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The synthesis of fluorescent probes has become exponentially cheaper and more commercially available, fluorescent labels have become brighter, and image detection has become more sensitive, allowing the detection of single mRNAs. In single-molecule FISH(smFISH), multiple fluorescent probes are hybridized to a single mRNA, which enables single-molecule detection without the need for sophisticated imaging instrumentation29, 30. Currently, smFISH is easily achievable and has been developed to be rapid31, multiplexed32, 33, automated and even high throughput34 (Fig. 1; see Supplementary information S1, S2 (figure, table)). Many alternative FISH protocols have been developed for detecting mRNAs, and these mostly differ by the type of probe used (see Supplementary information S2 (table)). To complement mRNA visualization by FISH, computational tools that analyse FISH data in an unbiased manner can provide quantitative insights into mRNA localization (Box 1).

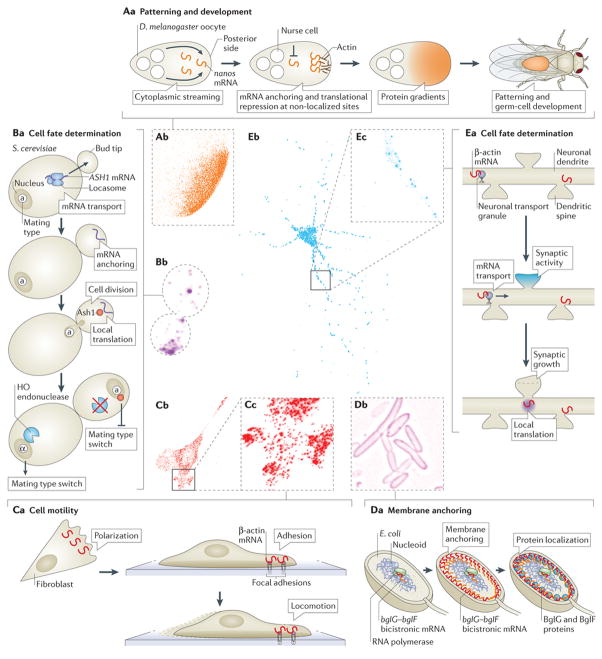

Figure 1. Visualizing and understanding mRNA localization in different model systems.

Aa | mRNA localization in oocytes and embryos can be essential for future patterning and development. In Drosophila melanogaster oocytes, cytoplasmic streaming from the nurse cells at the anterior drives nanos mRNA to the posterior, where it is anchored57 and translated, whereas mRNAs not present at the posterior are repressed to prevent translation173 (see Box 2 for a discussion on another mechanism contributing to the localized translation of nanos mRNA).Ab | Single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) of nanos mRNA localization in a 1-hour-old D. melanogaster embryo is shown. Ba | mRNA localization has an important role in cell fate determination during cell division. For example, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ASH1 mRNA, which encodes a transcription inhibitor, is transported to the bud tip by the locasome, a protein complex consisting of several RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and a myosin motor. Local translation at the bud tip inhibits the transcription of the homothallic switching (HO) endonuclease, which is required for mating type switch, thus preventing mating type switching in the daughter cell. Bb | smFISH of ASH1 mRNA in S. cerevisiae is shown. Ca | mRNA localization and local translation in fibroblasts have been shown to be important for proper cell migration and motility. For example, β-actin mRNA localization to the cell edge is correlated with cell polarization, and β-actin mRNA localization to focal adhesions is crucial for proper cell migration49. Cb | smFISH of β-actin mRNA in a cultured mouse embryonic fibroblast is shown. Cc | Enlarged image of dashed box in part Cb is shown. Da | In Escherichia coli, the bicistronic bglF–bglG transcript localizes to the plasma membrane in a translation-independent manner. This leads to the localization of BglF and BglG to the membrane. If bglG is transcribed as a monocistronic mRNA, it will localize to the poles (Fig. 4B) where, under certain conditions, the BglG protein will also be localized. Db | Image shows membrane-localized MS2–GFP-tagged endogenous bglF mRNA in E. coli. Ea | In neurons, mRNA localization to synapses is thought to be crucial for synapse development and plasticity. mRNAs, such as β-actin, are transported in dendrites, and synaptic activity is proposed to cause mRNAs to localize at stimulated synapses. The local translation of β-actin is proposed to cause morphological and functional alterations of synapses. Eb | smFISH of β-actin mRNA in a cultured mouse hippocampal neuron is shown. Ec | Enlarged image of dashed box in part Eb is shown. Each side of the dashed boxes of parts Ab, Cc and Ecrepresents 20 μm. Image in part Ab courtesy of T. Trcek and R. Lehmann, New York University School of Medicine, USA. Image in part Bb courtesy of T. Trcek. Image in part Db courtesy of O. Amster-Choder, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

Box 1. Quantitative analysis tools of mRNA localization.

The advent of the visualization of single mRNA molecules in individual cells necessitated the unbiased quantification of their abundance, distribution and movement in a variety of cell types. The following are some quantitative tools for analysing single mRNA molecules in cells.

Analysis of fluorescence in situ hybridization spots

Many laboratories specializing in single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) write their own analysis tools, some of which are based on IDL154, 155 or MATLAB53, 156 programs. Most programs use two-dimensional Gaussian fitting of candidate spots to obtain a sub-diffraction localization of single mRNAs156. The freeware FISH-quant can automatically analyse both cytoplasmic (single) mRNAs and nascent transcripts at transcription sites in three dimensions156. With smFISH, it is not always straightforward to prove that one is imaging the signal of a single mRNA, especially as multiple probes are used for their detection. To this end, the intensity distribution of FISH spots analysed with two- or three-dimensional Gaussian fitting should exhibit a single Gaussian distributed peak. In some cases, the number of probes bound to a single mRNA may be calculated by dividing FISH spot intensity by the intensity of a single FISH probe29, 62.

Analysis of mRNA localization

The visual determination of the extent of mRNA localization in a cell is essential for studying mRNA localization qualitatively; however, these studies typically lack a quantitative element so they are subject to human bias. To automate the quantification of mRNA localization, an unbiased analytical method was developed to objectively quantify cell polarization based on the distribution of the β-actin mRNA157.

Single-particle tracking

Tracking single mRNAs in live cells has been instrumental for gathering information on the mechanisms of mRNA localization26. Many of the principles of single-molecule identification and detection used for analysing FISH data (which are obtained from fixed cells) apply to live-cell imaging, although deteriorated signal-to-noise ratio, rapidly moving particles and temporary particle disappearance are some of the many challenges of tracking molecules in live cells. Tracking algorithms use various computational methods to link particles between successive frames158, 159. Many tracking tools are freely available160, and a popular one is u-track159. An exhaustive comparison of the tracking methods used by 14 different research groups was recently published161.

mRNA imaging in live cells

Much has been gained from FISH studies on how mRNAs are localized in cells; however, dynamic information on mRNA movements was lacking. To overcome this limitation, earlier as well as more recent studies have taken advantage of the binding of RBPs to specific mRNAs, by expressing GFP–RBP chimaeras as a way to indirectly follow mRNA dynamics35, 36, 37. A substantial advancement in mRNA imaging was the use of direct fluorescent tagging of mRNAs using the MS2 bacteriophage system. In this method, the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein (MCP) binds to a unique RNA hairpin sequence (MS2-binding site (MBS)) that can be cloned into the mRNA of choice38, 39. Multimerization of the MBS stem–loops and co-expression of MCP fused to a fluorescent protein (MCP–FP) enables time-lapse imaging of mRNA kinetics and localization in live cells (Fig. 2A).

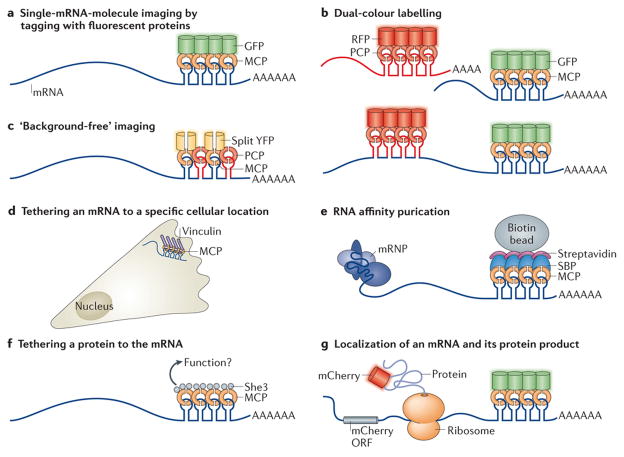

Figure 2. Traditional and novel uses of MS2-like systems to investigate mRNA biology.

a | Localization of single mRNA molecules can be studied by tagging with fluorescent proteins. The fusion of a stem–loop-binding protein, for example, the phage MS2 coat protein (MCP), to a fluorescent protein such as GFP allows single-molecule mRNA imaging38, 39. b | In dual-colour labelling, two mRNAs (top) or two different parts of the same mRNA (usually the 3′ and the 5′; bottom) aretagged by different stem–loop–RNA-binding protein (RBP)–fluorescent protein systems, thereby allowing the imaging of two different mRNAs in the same cell or the analysis of RNA dynamics, such as transcription, nuclear export and degradation43. c | A ‘background-free’ system is shown. To reduce background fluorescence, two different stem–loop species (for example, those of the MS2 and PP7 phage systems) bound to their respective RBPs — MCP and PP7 coat protein (PCP) — are used. Each RBP is fused to one half of a split yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), which by itself does not fluoresce. Only when both MCP and PCP are bound to the mRNA are the two halves close enough to become a functional YFP45. d | The tethering of an mRNA to a specific cellular location or structure (for example, focal adhesions) is carried out by fusing MCP to a protein (in this case, vinculin) with specific subcellular localization that anchors the mRNA to a specific cellular compartment, body or organelle49. e | In RNA affinity purification, an RBP such as MCP is fused to a unique epitope — for example, streptavidin-binding protein (SBP) — which mediates the affinity purification of the RNA (along with mRNA – protein (mRNP) complexes that might bind to it) using streptavidin and biotin beads149. f | A specific protein can be tethered to an mRNA through RBPs. The protein in question, which is thought to affect the mRNA or its associated proteins (for example, the transporter She3), is fused to MCP, which tethers it to the mRNA and allows the analysis of this direct interaction50. g | Simultaneous localization of the mRNA and its protein product can also be studied. By fusing the gene to the mCherry (a red fluorescent protein) open reading frame (ORF) and cloning MS2-binding sites (MBSs) into its 3′ untranslated region (UTR), the mRNA can be visualized by MCP – GFP binding and the protein by mCherry fluorescence51. See Supplementary information S2 (table) for more information.

Homologous systems using cognate hairpin–coat proteins were developed (see Supplementary information S2 (table)). The U1A mRNA labelling system, which is limited to non-mammalian cells, uses the RNA–protein couplet of the human U1A protein, a component of the spliceosomal U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (U1 snRNP), and a specific RNA hairpin40. Similarly, the phage PP7 coat protein (PCP) and its cognate RNA hairpin were cloned41, as was the λ-phage N-protein–boxB system42, allowing live-cell imaging of two mRNA species simultaneously42, 43(Fig. 2B). There are ongoing improvements in coat protein labelling of mRNA secondary structures. For instance, as MCP dimerization is a prerequisite for binding to the MBS, expression of a genetically dimerized version of MCP increases mRNA binding efficiency44. Furthermore, the use of a bimolecular fluorescence complementation system — whereby different coat proteins are fused to a split fluorescent protein such that only the binding to mRNA stem–loops will form a competent fluorescent protein — results in ‘background-free’ imaging45 (Fig. 2C). To complement these live mRNA imaging methods, computational particle-tracking tools (Box 1) are used to analyse mRNA movements in the cell.

Other techniques use exogenous fluorescent dyes to label RNAs in live cells. These dyes bind either to a dedicated protein (for example, a SNAP tag46) fused to a coat protein or directly to RNA aptamers (such as Spinach and RNA-Mango47, 48). These dyes can be brighter and more photostable than fluorescent proteins. However, delivery of non-genetically encoded labels may be more detrimental to the cell and may introduce background fluorescence. Furthermore, some of the RNA aptamers may not be suitable for single-molecule imaging (see Supplementary information S2 (table)).

In addition to labelling for imaging purposes, the interactions of coat proteins with mRNAs are used to alter intracellular mRNA localization. MCP fusions to various cellular components have enabled the artificial localization of mRNAs to subcellular sites to rescue mRNA localization defects49 (Fig. 2D). Other uses of MS2–MCP-like systems include the affinity purification of RNAs (Fig. 2E), tethering proteins to the mRNA50 (Fig. 2F) and the simultaneous localization of mRNAs and their protein products51 (Fig. 2G).

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

Imaging single mRNA molecules has brought with it a need to acquire absolute measurements of the concentration, movement, interactions and specific composition of a single mRNA – protein (mRNP) complex. One method to do this is fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), a powerful technique to directly measure diffusion, concentration and molecular interactions of single molecules in vitro and in vivo. This technique measures the fluctuations in fluorescence intensity of fluorescently labelled molecules, which result from their diffusion through a sub-femtolitre observation volume. Fluctuation analysis has allowed the measurement of subcellular, local diffusion properties and local concentrations of MCP-labelled endogenous mRNAs44, transcription factors and mRNA production rates52. Furthermore, brightness and diffusion measurements can reveal mRNA aggregation or dimerization, and dual-colour imaging of a single mRNA in conjunction with fluorescently labelled RBPs allows investigators to precisely quantify the association of the two species through fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy (FCCS).

Transgenic organisms for mRNA imaging

Transgenically modifying mRNAs to enable their fluorescent labelling circumvents many challenges of expressing exogenous mRNA tags and supports physiological mRNA metabolism. The development of genetically encoded systems to tag endogenous mRNAs was initially used in yeast, which is highly amenable to genetic manipulations. Transgenic model systems of higher complexity have allowed the visualization of endogenous mRNA localization in primary cells53, oocytes54, 55, 56, embryos57, tissue slices58 and even whole animals58. MS2 stem–loops and fluorescent coat proteins expressed in transgenic D. melanogaster have increased our understanding of the localization mechanisms of endogenous nanos57, bicoid56 oskar54 and gurken55 mRNAs. The first mammalian transgenic animal for imaging mRNA in living tissue was a mouse with MBS inserted into the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of the β-actin mRNA, which allows its imaging in every cell of the animal53. Subsequently, a transgenic mouse expressing MCP fused to GFP was crossed with the β-actin–MBS mouse, bypassing the need to deliver MCP and enabling global fluorescent labelling of the endogenous β-actin mRNA for direct imaging in cells and in tissues58. The advent of CRISPR–Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat–CRISPR-associated protein 9) tools for carrying out genetic modifications will expedite the generation of transgenic animals for the imaging of endogenous mRNAs59. However, as many mRNPs contain only a single mRNA29,60, 61, 62, 63, 64, contesting tissue autofluorescence in certain circumstances may require brighter labels for in vivo mRNA imaging of single molecules.

Cellular mechanisms of RNA localization

Overcoming entropy to maintain asymmetry in cellular mRNA distribution requires the orchestration of many mRNA adaptors and regulators. The transport, translation, protection from degradation and anchoring of mRNAs are all determined by RBPs. In turn, the interaction of RBPs with mRNAs is determined by the localization elements in the mRNAs that operate like subcellular localization ‘zip codes’ (Box 2; reviewed in Refs 65, 66) or, in certain instances, by the gene promoter67. To spatially restrict translation, mRNA distribution must be accompanied by translational repression while the mRNA is in transit (reviewed in Ref. 68). Interestingly, many RBPs simultaneously maintain translational repression while coordinating mRNA trafficking (reviewed in Ref. 69).

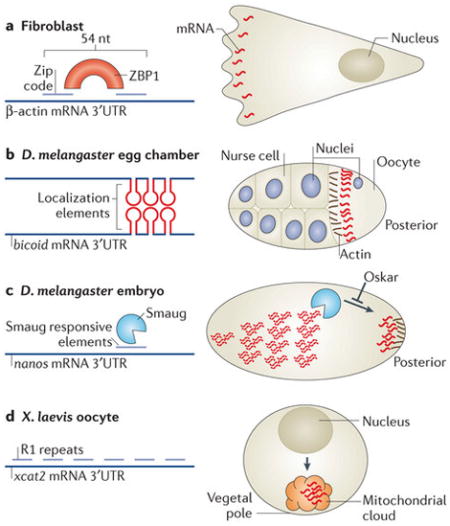

Box 2. Cis-acting elements that control mRNA localization.

Short sequences in mRNAs can act in cis to control mRNA localization by one or more of the following mechanisms.

Promoting active and directed transport

The β-actin mRNA ‘zip code’ is a 54-nucleotide (nt) sequence in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) that contains a bipartite motif, which is recognized by the RNA-binding protein (RBP) zipcode-binding protein 1 (ZBP1)70 (see the figure, part a). Binding of ZBP1 to the mRNA is necessary and sufficient to localize it to the leading edge of fibroblasts in a cytoskeleton- and motor-dependent manner162, 163 (see the figure, part a) and to neuronal dendrites164. The 3′UTR of the Drosophila melanogaster bicoid mRNA contains several 50-nt sequences termed bicoid localization elements, which form stem–loop structures that form intermolecular interactions (see the figure, part b). The dimerization of the stem–loops and association of the double-stranded RNA with the RBP Staufen are required for the active transport of bicoid mRNA along microtubules at late oogenesis and for its anchoring to the anterior pole23, 165, 166, 167. In yeast, the ASH1 mRNA contains four localization sequences, three in the coding region and one in the 3′UTR. These sequences are required for the association with the locasome and for active transport by the myosin motor Myo4 (Fig. 1B).

Mediating local stability

The mRNA for heat shock protein 83 (hsp83) localizes to the posterior pole plasm of D. melanogaster embryos. This is accomplished by extensive degradation of this mRNA throughout the cytoplasm, except at the pole plasm. Elements at the hsp83 3′UTR were identified as responsible for this protection168. The D. melanogaster nanos mRNA is localized to the posterior pole of the embryo by several mechanisms (Fig. 1A; see below), including through the local stabilization of the transcript by Oskar, which prevents the degradation factor Smaug from binding Smaug-responsive elements in the 3′UTR of nanos mRNA169 (see the figure, part c).

Entrapment and anchoring of diffusing mRNAs

At late D. melanogaster oogenesis, the main mechanism for nanos mRNA localization is diffusion and entrapment when strong cytoplasmic flows move it throughout the oocyte so it can encounter a localized, actin-based anchor at the posterior pole57 (Fig. 1A). This localization is mediated by multiple RBPs, which associate with cis-elements at the nanos mRNA 3′UTR170, 171. During early oogenesis in Xenopus laevis oocytes, xcat2 and xdaz1 mRNAs are localized at the vegetal pole in an assembly of mitochondria and entrapped mRNA (called the mitochondrial cloud). Through a microtubule-independent mechanism, the mitochondrial cloud containing the mRNA migrates to the vegetal pole by diffusion (see figure, part d). The 3′UTR of xcat2 contains six repeats of a short motif, UGCAC (named R1). Point mutations in the second, third or fourth repeats resulted in reduced xcat2 localization to the mitochondrial cloud. However, the insertion of R1 motifs to the 3′UTR of another mRNA, vg1, did not result in its localization to the mitochondrial cloud. Thus, R1 motifs are required but not sufficient for correct mitochondrial cloud localization172.

mRNA–protein complexes form granules

mRNAs and proteins are organized in cellular units of diverse composition, structure, size and function, all of which are loosely termed RNA granules. To understand how mRNA localization is regulated, emphasis should be placed on the characterization of the specific composition, size and diversity of granules of unique mRNAs. There are many well-understood examples of mRNA–RBP interactions studied outside their cellular context; however, the higher-order structure and make-up of mRNP complexes and granules in vivo are still poorly understood. Sequence binding specificity of any mRNA–RBP pair can be defined down to the nucleotide level, paving the way for identifying other putative mRNAs bound by similar RBPs70. As a single type of RBP may have hundreds of mRNA targets70, 71, 72,73, we may assume that perhaps at least dozens of RBPs and RNA regulatory proteins interact with a single mRNA at any given time; for example, gurken mRNA is known to be bound and regulated by a number of RBPs74, 75. Similarly, β-actin mRNA has so far been shown to interact with at least 10 RBPs24, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, although the direct role of some of them in its localization remains to be determined.

Biochemical affinity purification and identification approaches have been instrumental in identifying scores of proteins that are components of various RNA granules83, 84, 85, but these do not indicate how diverse the composition of individual granules can be. The direct comparison of the proteins associated with the RBPs Staufen2 and Barentsz in RNA granules showed that they only have a 30% overlap, and that their RNA-binding profiles are also enriched with unique mRNAs85. This illustrates the potential extent to which granules with diverse mRNA compositions are composed of unique protein components. Interestingly, the assembly of proteins into granules is emerging as a special characteristic of RBPs, and is facilitated and modified by certain RBP motifs86, 87. Thus, when studying how RBPs affect mRNA localization, the combinatorial effect of many RBPs on a single mRNA may make it difficult to parse out their individual roles. Conversely, the large number of potential mRNA targets of an individual RBP may obstruct interpretations of how RBPs affect cell physiology through the loss of mRNA localization.

Omnia mea mecum porto: All that is mine, I carry with me

mRNAs often travel as single entities in cells29, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 and often exhibit distinct localization patterns8. This individualistic behaviour may confound our understanding of how cells accomplish the localization of multiple mRNAs. Unbiased screens in hippocampal brain tissue and D. melanogaster embryos identified thousands of localized mRNAs8, 9; conversely, only 600–800 mammalian RBPs have been recognized so far (Refs 88, 89; see the RBP database), raising intriguing questions about the mechanisms of differential and unique localization of multiple mRNAs. As individual RBPs may have tens to hundreds of mRNA targets70, 71, 72, 73 and a single mRNA may bind to many proteins, it is possible that mRNAs contain unique combinations of sequence elements that dictate their protein associations and thus their subcellular localization (Box 2; reviewed in Refs65, 66), as well as their metabolism and function. Consistent with this, the stoichiometry of mRNA and RBPs in cells seems to be carefully regulated, as the overexpression of RBPs may exaggerate mRNA localization patterns88, 89. Studies investigating mRNA movements in live cells have shown that RBPs bias the stochastic nature of mRNA diffusion and transport, resulting in asymmetric intracellular mRNA distribution26. Below, we discuss examples of the biases RBPs introduce to mRNA behaviour to alter their spatial distribution.

Transport of mRNAs by motor proteins

Active, motor-based locomotion of mRNAs along the cytoskeleton can swiftly transport them throughout the cell (Fig. 3). In fact, an mRNA transported by a molecular motor moving at 1.5 μm per second can transverse the same distance 60 times faster than by diffusion60. The motor proteins myosin V, which transports vesicles along actin filaments, as well as certain members of the kinesin and the cytoplasmic dynein families, which transport cargo along microtubules (mostly in the plus-end and minus-end directions, respectively), all have important roles in actively transporting mRNAs in various biological systems (reviewed in Ref. 90). Motored transport of mRNAs is emerging as a complex process that requires the orchestration of many proteins (reviewed in Ref. 91).

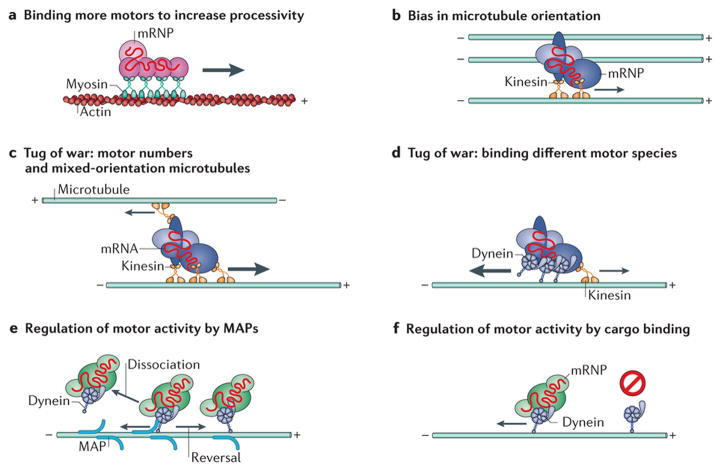

Figure 3. Cellular determinants of motored mRNA transport.

Owing to the bidirectional orientation of microtubules in most cell types and to the unidirectional movement of each molecular motor along them, the directional movement of mRNA in cells may seem disorganized when observed. Nevertheless, several cellular mechanisms of biased motored mRNA transport have recently been identified. a | To increase the processivity of directed mRNA transport, some mRNAs bind to multiple motors. For example, each ASH1 mRNA molecule has four localization elements, which mediate the binding of four She3 RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and, in turn, the binding of four myosins92. b |Local biases in the orientation of microtubules have been shown to cause a bias in mRNA transport, allowing mRNA localization54, 94, 176. c | In the case of mixed-orientation microtubules, mRNAs bound to multiple motors may experience a ‘tug of war’ and will be transported in the direction of the strongest combined motor force. d | Alternatively, mRNAs bound by different types of molecular motors, which move in opposite directions, may also undergo a tug of war and will be transported in the direction of the stronger force exerted. e | Microtubule-associated proteins (MAP) have been shown to alter the dissociation rates of motors from microtubules and to cause a motor to change direction when moving along a microtubule, presumably by behaving as an obstacle93, 95. f | The binding of cargoes to motors has been shown to alter their binding and motility on microtubules98, in addition to increasing their processivity along microtubules96, 97. mRNP, mRNA – protein.

Although it is known that certain RBPs are necessary for active transport-dependant mRNA localization, few have been shown to interact directly with motor proteins. Transported mRNAs are likely to bind to complexes of RBPs, motors and adaptor proteins. As mRNAs can be transported by multiple motor proteins, multiple RBPs must coordinate their binding and function during the localization process61. Indeed, the number of localization elements on a single mRNA linearly correlates with the number of motors that bind to it92 (Fig. 3a). The increased likelihood of mRNA binding to motors through the inclusion of localization elements and through elevated RBP binding is known to increase the processivity, or run length, of single mRNAs61 and RBP particles37 along the cytoskeleton (Fig. 3a). Thus, binding to RBPs can improve mRNA transport by increasing the net distance the mRNA travels.

Interestingly, removing a localization element or mutating a regulatory RBP does not necessarily prevent net mRNA translocation; however, on average the paths of active transport are shorter and the probability of a transported mRNA reversing in direction increases37, 60, 61, 91. It has been observed that the lacZ mRNA cloned from Escherichia coli and expressed in mammalian cells, which has no known localization elements, exhibits low levels of active transport60. Similarly, the localized S. cerevisiae ASH1 mRNA (see below) retains a low probability of associating with a myosin motor when stripped of its zip code92. The movement of mRNAs devoid of localization elements suggests that there is an intrinsic mechanism for the interaction of mRNAs with molecular motors. Therefore, active transport may allow homogenous intracellular mRNA distribution60, 93. These studies imply that active transport is not inherently biased, signifying that the attachment to a motor alone will not localize mRNAs. Therefore, delivering mRNAs to subcellular compartments would require additional mechanisms to regulate the directionality of active mRNA transit.

As microtubules and actin filaments are polarized, directional specificity may be regulated by the differential binding of RBPs and motor proteins to mRNAs. For example, mRNAs localized to the apical cytoplasm in D. melanogaster syncytial blastoderms have been shown to be biased towards minus end-directed movement on microtubules owing to the specific binding of Bicaudal D and Egalitarian proteins, which themselves bind to dynein89. Similarly, the presence of a localization signal in specific mRNAs increases their processivity and transport towards minus ends of microtubules owing to the increased association with dynein61. In other cases, the polarity of the microtubules itself is distributed nonrandomly within the cell. For example, the localization of oskar mRNA to the posterior of D. melanogaster oocytes is the result of a kinesin-based active transport with a slight bias in the posterior direction owing to biased microtubule polarity54, 176. Likewise, the distribution of mRNAs to the vegetal cortex of X. laevis oocytes is accomplished by the enrichment of microtubules oriented with their plus ends positioned at the vegetal cortex94(Fig. 3b).

In many of the aforementioned cases, single mRNAs or RNPs are seen to travel in a bidirectional manner, indicating a simultaneous binding of both kinesin and dynein, which typically traffic to opposite ends of microtubules. Synchronizing multiple motors that exert opposing forces on a single RNP to enable directional travel towards a destination is a complex, regulated process. Simply considering the types and numbers of motors bound to an RNP and the net force of multiple motors pulling in opposite directions should determine the net directionality of mRNA transport (Fig. 3c,d). However, the binding of a motor to an RNP may not linearly contribute to its active transport, as the binding affinity of motor proteins to the cytoskeleton and their motor activity are subjected to regulated modification (reviewed in Ref. 95). For example, microtubule-associated proteins can regulate motor dynamics either by altering their microtubule binding and dissociation kinetics or by altering the motility properties of motors, such as increasing reversals in direction, presumably by acting as obstacles93, 95 (Fig. 3e). In other cases, adaptor proteins96,97 and RBP cargoes98, 99 have been shown to activate or alter motor activity (Fig. 3f). It is also intriguing that a single mRNA species may be subject to different mechanisms of transport in different cell types; for example, β-actin mRNA in glia cells is largely diffusive, whereas in neuronal dendrites β-actin and ARC mRNAs are static or motored58, 62, 100, 101 (see Supplementary information S3 (movie)). Although it is tempting to assume that altered mRNA behaviour is the result of disparate RBP expression, enigmatically the same regulatory proteins that localize nanos mRNA to the posterior pole of D. melanogaster embryos through diffusion and entrapment (Box 2) have a role in mediating its dynein-dependant transport in larval neurons102.

mRNA anchoring

In certain cases, mRNA localization may be brought about partially or entirely by spatially selective mRNA capturing or anchoring. Many examples of actin-dependent anchoring of mRNAs have been observed. In fibroblasts, β-actin mRNA is linked to actin filaments via the translational machinery103. vg1 (also known as dvr1) mRNA localization in X. laevisoocytes depends on microtubule-based transport and actin-based anchoring at the vegetal cortex12. Actin-dependent anchoring of nanos and oskar mRNAs was shown to occur in the posterior of D. melanogaster oocytes57, 104 (Box 2; Fig. 1A). Similarly, anterior localization ofbicoid mRNA in D. melanogaster oocytes depends on active transport of the mRNA followed by actin-dependent anchoring56 (Box 2).

In addition to the actin cytoskeleton, in D. melanogaster motors themselves were shown to dock mRNAs after transporting them. For example, dynein converts from functioning as an active motor to behaving as an anchor during the localization of fushi tarazu mRNA in blastoderms105. In yeast, ASH1 mRNA is anchored at the bud tip following its transport along the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 1B). Although the mechanism of anchoring is not fully known, it requires specific secondary structures along the open reading frame (ORF) and the active translation of the carboxy-terminal region106. In neurons, ARC mRNA (which encodes activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein) is found anchored underneath individual dendritic spines, or synaptic contacts101, raising intriguing possibilities of synapse-specific modification of transmission properties through local translation.

Localization in unicellular organisms

Asymmetrical cell organization is not restricted to cells of multicellular organisms: both unicellular eukaryotes and bacteria exhibit asymmetries107, 108, such as uneven distribution of intracellular organelles or protein complexes, cellular extensions and asymmetric cell division. mRNA localization has been shown to have an important role in generating and maintaining many of these asymmetries in unicellular organisms.

mRNA localization in yeast

In budding yeast, cell division is asymmetrical, such that the daughter cell buds from the mother cell and has a different mating type. mRNA localization is known to play a crucial part in this process, and the dynamics of mRNA localization have been well characterized in this system. The inaugural use of the MS2 system was to study ASH1mRNA in haploid yeast cells to investigate its localization during asymmetrical cell division38, 39. During cell division, ASH1 mRNA and other mRNA species, proteins and organelles are transported to and anchored at the bud tip. Ash1 is a DNA-binding protein that represses the transcription of the homothallic switching (HO) endonuclease in the daughter cell nucleus, thereby inhibiting mating type switching. Localization of ASH1 mRNA to the bud tip during anaphase causes Ash1 repression of HO expression in the daughter cell but not in the mother cell6, 109, 110,111, thus inhibiting mating type switching exclusively in the daughter cell (Fig. 1B). FISH and live imaging experiments determined the exact timing at and mechanism by which the ASH1 mRNA is delivered to the bud tip6, 38, 39, and identified both cis and trans factors that are required for its localization (reviewed in Refs 112, 113, 114). Briefly, the RBP She2 recruits ASH1 mRNA to a myosin motor protein (Myo4) via an adaptor protein (She3). This complex, termed the locasome38, 39, transports the mRNA along the actin cytoskeleton to the bud tip111. The assembly of a functional locasome complex is likely to occur in the nucleus and requires the nuclear pore protein Nup60 (Ref. 115). Once in the cytoplasm, the RBPs Khd1 (also known as Hek2) and Puf6 repress the translation of ASH1 mRNA until it reaches the bud tip116, 117. Puf6 is co-transcriptionally recruited to ASH1 mRNA, as well as to five other bud-tip localized mRNAs, by She2 and another nuclear RBP, Loc1 (Ref. 118). Puf6 inhibits translation by binding to eukaryotic initiation factor 5B (eIF5B), which prevents ribosome subunit binding to the mRNA. At the bud tip, the membrane-associated casein kinase Yck1 phosphorylates Puf6 and Khd1 exclusively, leading to the release of eIF5B and enabling translation119.

In a recent study, which used ASH1 mRNA as a model for mRNA transport, increasing the number of ASH1 localization elements on single ASH1 mRNA molecules resulted in a linear increase in the frequency and processivity of its transport, and this represents an important demonstration of how motor cooperativity is used to enhance mRNA localization92 (Fig. 3a). Interestingly, the absence of an mRNP cargo abolishes motor protein motility, demonstrating cargo-dependent regulation of motor activity98 (Fig. 3f). More recently, an in vitro study of ASH1–motor complex assembly showed that the She2–She3 complex was required for motor movement but that the mRNA cargo itself was dispensable99.

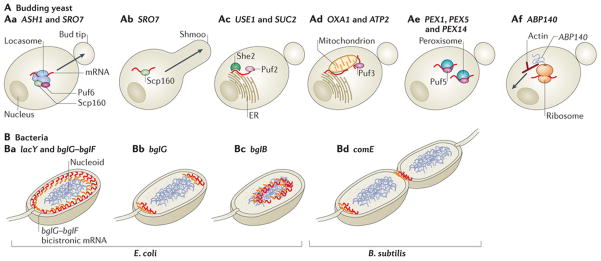

Tagging endogenous mRNAs in yeast with the MS2 system has also helped to determine the localization of peroxisomal120 and mitochondrial121, 122 mRNAs, mRNAs encoding secreted or membrane proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)123, and of the ABP140 mRNA (which encodes an AdoMet-dependent tRNA methyltransferase) to the distal pole of mother cells124(Fig. 4A). It has also been used to study the dynamic movement of mRNAs into processing bodies (P-bodies)67, 125. In addition, other bud-tip localized mRNAs have been identified using various imaging methods126, 127, 128, overall demonstrating the widespread occurrence of mRNA localization in these spherical organisms. Interestingly, SRO7 mRNA, which encodes an effector of the Rab GTPase Sec4, localizes to at least two distinct locations under different conditions. In proliferating cells, it is transported to the bud tip in a She2–She3–Scp160-dependent manner. However, in haploid cells arrested in G1 owing to exposure to mating pheromones, SRO7 mRNA is transported to pheromone-induced polarized membrane extensions (known as shmoos) through G-protein-coupled receptor signal transduction, which depends on the ligand-activated RBP Scp160, but not on She2–She3 (Ref. 129) (Fig. 4A). Thus, the SRO7 mRNA can be transported by different mechanisms, depending on its destination and on physiological signals.

Figure 4. mRNA localization in unicellular organisms.

A | In budding yeast, the ASH1 and SRO7 mRNAs are transported to the bud tip by the locasome (which comprises Myo4, She3 and She2), Scp160 and Puf6 (part Aa). Following pheromone chemotaxis, SRO7 mRNA is transported to the shmoo tip by Scp160 but not by the locasome (part Ab). mRNAs encoding membrane or secreted proteins (such as USE1 and SUC2) are localized to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), in a Puf2- and She2-dependent manner (part Ac), whereas the OXA1 and ATP2 mRNAs, which encode mitochondrial proteins, are targeted to mitochondria or to the mitochondrion–ER interface in a Puf3-dependent manner (part Ad). Some mRNAs encoding peroxisomal proteins (for example, PEX1, PEX5 and PEX14) are localized to peroxisomes in a Puf5-dependent manner (part Ae). The ABP140 mRNA, which encodes AdoMet-dependent tRNA methyltransferase, is transported to the far pole of the mother cell by direct binding of the amino terminus of its nascent protein product, Abp140, to actin filaments. The retrograde movement of actin drives ABP140 mRNA to the far pole in a motor-independent manner (part Af). B | In bacteria, the Escherichia coli lacY and bglG–bglF mRNAs, which encode transmembrane proteins, localize to the plasma membrane (part Ba). bglG transcribed as a monocistronic mRNA localizes to the cell poles (part Bb), whereas bglB transcribed alone is cytoplasmic (part Bc). In Bacillus subtilis, the comE transcript, which is an operon that encodes factors for horizontal gene transfer, is localized to the nascent septum that separates daughter cells, and to cell poles174 (part Bd).

mRNA localization in bacteria

Subcellular targeting of mRNAs was thought to occur only in eukaryotes. Electron micrographs showing polysomes attached to bacterial chromosomes130 led to the assumption that all bacterial mRNAs are co-transcriptionally translated and that subcellular targeting was limited to proteins. This view was challenged when mRNA imaging revealed that bacterial mRNAs are localized to specific subcellular sites in a translation-independent manner131. The lacY mRNA, which encodes the membrane-bound lactose permease, and the bicistronic bglG–bglF or polycistronic bglG–bglF–bglB mRNAs, which encode proteins necessary for aryl-β-glucoside metabolism, localize to the cell membrane, the site of their corresponding protein products131 (Figs 1d,4B).

Interestingly, the signal for bglG–bglF–bglB mRNA localization to the membrane was found to be in the sequence encoding the first two transmembrane helices of bglF. This is in contrast to many eukaryotic mRNAs, which carry their zip codes in the 3′UTR. This sequence is uracil-rich, similar to various transmembrane proteins in other kingdoms132, which suggests the existence of an ancient membrane-targeting mechanism for mRNAs that encode transmembrane proteins. ThebglF membrane-targeting sequence is dominant over the targeting sequences in the other genes in this polycistronic transcript, as bglB mRNA alone is cytoplasmic and bglG mRNA localizes to the poles (Fig. 4B). Deciphering the bacterial localization zip codes and their underlying mechanisms of localization is a future challenge.

mRNA localization in neurons

Morphologically and functionally distinct from unicellular organisms and somatic cells of multicellular organisms, the shape and function of the neuronal cell provide an intuitive justification for the occurrence of mRNA localization to distal subcellular regions. For example, local translation at synapses is thought to underlie persistent changes in neuronal transmission, which are crucial to learning and memory133. In the past 3 decades, FISH and sequencing technologies have identified >2,000 mRNAs that are present in the dendritic and axonal portion of neurons9, 134, 135, highlighting the vastness of the dendritic and axonal transcriptome.

Motored mRNA transport in neurons

Neuronal axons and dendrites, collectively known as neurites, provide long, linear tracks for studying mechanisms of motored (active) mRNA transport. Intuitively, motored transport should play an important part in mRNA movement along long neurites. Indeed, kinesin isolated from brain tissue interacts with many RBPs, as well as with theCAMK2A (which encodes calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II subunit-α) andARC mRNAs83. More recently, kinesin was shown to interact with thousands of RNAs, which constitute about 2–5% of the total neuronal transcriptome isolated from the sea hare Aplysia californica136; this is comparable to the number of mRNAs present in the extra-somatic region in the mouse hippocampus9, demonstrating the widespread use of active transport for mRNA localization in neurons.

Live observations of RNA movement in neurons carried out with the RNA dye SYTO14 showed that RNA material (probably mostly ribosomal) moved in a directional manner in dendrites, revealing microtubule-dependent RNA motility137. The measured motored transport rates of 0.1 μm per second were 20 times faster than the anticipated rate of 0.5 mm per day, which was calculated from the average speed at which radioactively pulsed RNA migrated into dendrites138. These two measurements are in fact in agreement, as on average RNA migrates slowly into neurites, and only a subset of individual RNAs would be actively moving at the rapid speed measured in the later study. Rapid mRNA transport in conjunction with low transport probability was recently confirmed to be the case for β-actin mRNA53, 58, 62. These comprehensive measurements of single, endogenous β-actin mRNA kinetics showed that only 10% of the mRNA molecules were actively transported at any given time with a mean speed of 1.3 μm per second58, although the range of instantaneous rates of β-actin mRNA transport have been shown to be 0.5–5 μm per second53. The motored RNA population migrated in both directions in dendrites, and the distance travelled was longer in the anterograde direction, raising the possibility that biased directionality in actively transported mRNAs leads to mRNA localization into distal regions in neurons137. Live imaging of mRNA in neurons largely suggests that actively transported mRNAs travel further in a single trip than mRNAs in other cells38, 39, 58, 60 (Fig. 5). How this behaviour is unique to neurons is likely to be a subject of future research.

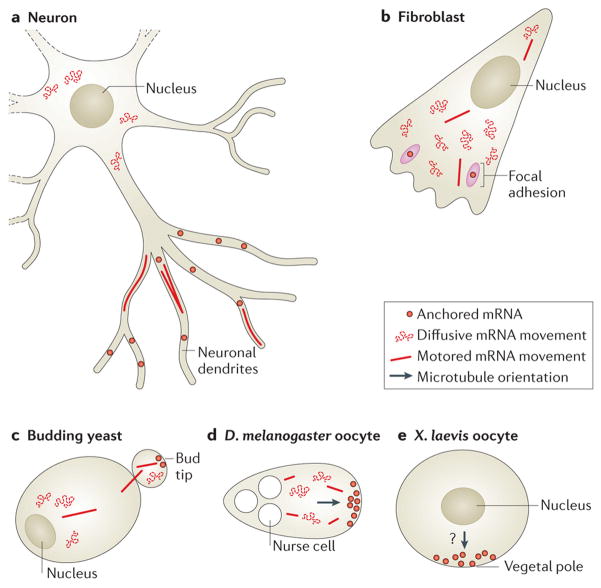

Figure 5. Different types of mRNA movements depend on subcellular location and on cell type.

a | Different types of mRNA movements can be observed in neurons, including diffusive movement; active, motored transport; and stalling or anchoring of mRNAs. Whereas around the nucleus, mRNAs encoding β-actin seem to move in a diffusive manner, in dendrites β-actin and ARC mRNAs seem to be largely stalled or corralled, and 10% of dendritic mRNAs are seen to undergo active transport on microtubules58, 62, 100, 101. b | In fibroblasts, most β-actin mRNAs are diffusing. A small percentage is transported along microtubules, and some mRNAs dwell near focal adhesions49, 58. c | In budding yeast, ASH1 mRNAs are mostly diffusive. The localization of the ASH1 mRNA is accomplished through myosin-mediated transport to the bud tip, where the mRNA is anchored38, 39, 175.d | oskar mRNAs in Drosophila melanogaster oocytes move around mostly in a diffusive manner. A small percentage can be seen moving along the cytoskeleton for brief lengths54. At the posterior, oskar mRNAs are anchored. e | vg1 mRNAs in Xenopus laevis oocytes localize to the vegetal cortex owing to a bias in the placement of the plus ends of microtubules94. This localization depends on two forms of kinesin, although the precise dynamics of vg1 mRNA movement are unclear.

The actively transported population of mRNAs in neurons has been repeatedly reported to exhibit long, processive, oscillatory movements in neurites58, 100, 137, 139. The existence of these oscillating mRNAs, which switch between anterograde and retrograde active transport, raises many questions of how such seemingly random movements result in proper mRNA localization. Single RBPs may direct this oscillatory behaviour; for example, the RBP fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) is associated with both kinesin and dynein in D. melanogaster, reiterating that a single moving mRNA particle may be simultaneously associated with different motors140 (Fig. 3d). Consistent with its role in recruiting motor proteins to mRNAs83, 140, increasing FMRP expression in flies also results in increased processivity and frequency of actively transported mRNAs141. In addition to its role in mRNA transport, FMRP has a key role in translational repression of localized mRNAs in neurons72, similar to many RBPs that that maintain dual functions to achieve local gene expression68.

Long-term maintenance of mRNAs in neurons

Although much interest has been directed towards actively transported mRNAs, non-motile mRNAs are of interest, as they may be specifically positioned near synapses. Local translation could deliver proteins to stimulated synapses to drive or maintain synaptic plasticity133. The number of synaptic sites on dendrites is likely to outnumber the abundance of single mRNAs, as shown to be the case for the abundant β-actin mRNA62. However, a subset of synapses seem to maintain mRNAs at the base of their dendritic spine, as shown for ARC mRNA101. Therefore, signalling cascades downstream of synaptic activity may instruct mRNAs to halt at synapses where local translation is needed (Fig. 1e). The ‘sushi belt model’ has been put forth to link observations of bidirectional active transportation of mRNA in neurites and the presence of static mRNAs at synapses142. In this model, a fraction of mRNAs is constantly in flux, moving up and down dendrites and waiting for cues to halt or be captured at a synapse.

As the contribution of local translation to synaptic plasticity is consistent with local activity, localized dendritic mRNAs may be translationally repressed much of the time. This may be accomplished through mRNA containment in neuronal RNA granules containing translationally repressed mRNAs, ribosomes and translation factors143. smFISH of endogenous β-actin mRNA in neurons suggested that mRNAs are released from RNA granules for approximately 15 minutes following synaptic stimulation and are subsequently repackaged into them, indicating that certain mRNAs may undergo multiple rounds of translation and repression based on the activity of neighbouring synapses62 (Fig. 1e).

Functional importance of neuronal local translation

Although there is an abundance of evidence showing that synaptic plasticity depends on local protein synthesis133, evidence on the direct role of local translation of specific mRNAs in synaptic plasticity is scarce. It is technically challenging to experimentally manipulate local translation of a specific mRNA without affecting its somatic or global translation. However, one experimental paradigm used for demonstrating the functional effects of mRNA localization is the removal of localization elements from mRNAs. The 3′UTR ofCAMK2A mRNA mediates mRNA localization into dendrites144, and removal of the 3′UTR in transgenic mice resulted in 85% loss of dendritic CAMKIIα, accompanied by deficits inlong-term potentiation and memory formation145. An analogous study used a conditional deletion of the axonal targeting region of the 3′UTR of importin β1 mRNA, the ncoded protein of which is known to have a role in altering gene expression during axonal injury. This deletion reduced axonal importin β1 levels and perturbed axonal repair following injury, which is consistent with the notion that locally synthesized proteins have a role in axonal modification and repair146. A third study found that the loss of localization of the mRNA encoding lamin B results in reduced membrane potential, an elongated morphology of axonal mitochondria and, ultimately, axonal degradation147. These studies showed functional outcomes of partially or entirely removing the 3′UTR of certain mRNAs. It would be interesting to study how finer mutations or shorter deletions — specific to the mRNA localization sequences — which are now feasible using genome engineering by CRISPR–Cas9 (Ref. 59), or how altering mRNA localization by artificial tethering (Fig. 2D), will alter brain functionality.

Comparing mRNA transport in spheres and trees

How are mRNA localization regulatory mechanisms similar or different in the morphologically distinct neurons and unicellular organisms? Neuronal protrusions can be hundreds of micrometres long, whereas yeast may be only 10 μm long. Yeast cells use myosin and the actin cytoskeleton, whereas neurons mainly use kinesin, dynein and microtubules, to transport mRNAs. The reasons for this are unclear, although differences in cytoskeletal organization and motor processivity are likely to have a role. Remarkably, live imaging of different zip code-containing mRNAs in various organisms has consistently shown that 10–20% of mRNA molecules undergo active transport in neurons, D. melanogaster oocytes and COS cells54, 56, 58, 60, although this percentage is smaller in fibroblasts58 (Fig. 5). An obvious difference in active transport between these systems is the run length of motored mRNAs, which is clearly regulated differently (Fig. 5). By and large, in most cells observed, mRNA localization resembles a random walk punctuated with bouts of active transport and, in some cases, ending with anchoring at a destination. Tight translational repression of mRNAs for long periods of time in neurons is reminiscent of the sequestration of maternal mRNAs in oocytes, both of which are known to be relieved by intracellular calcium influx56, 62. The observation that many mRNA species localize to specific organelles in yeast (Fig. 4) prompts questions of whether this also occurs in neurons or other cells. Future work will increase our knowledge of how these processes may have evolved and how they are regulated to ensure cell specificity.

Looking forward

It is becoming evident that mRNA localization has a crucial role in regulating the expression of many proteins, from bacteria to mammals. New technologies for visualizing RNA now enable subcellular, single-molecule analysis of gene expression. For example, FISH sequencing (FISSEQ)148 (see Supplementary information S2 (table)) of RNA can provide information on the localization of numerous mRNAs, including splice variants and even single-nucleotide polymorphisms (for example, RNA editing products). Enhanced imaging technologies will certainly reveal more information pertaining to mRNA localization kinetics and variability.

Many questions remain regarding how mRNA localization is regulated by RBPs, and future research will reveal more complexity than we currently imagine. The full protein content of a single RNP or granule in situ is unknown, and there is little information on how many proteins simultaneously exert their effect on a single mRNA. Using innovative systems such as RNA purification and identification (RaPID)149, which combines the utility of MS2-like systems with affinity purification (Fig. 2E), will enable biochemical analysis of specific RNP complexes, thus providing insights into their assembly on transported mRNAs. Single-molecule imaging of RNA–protein interactions in situ could be used to analyse RNP content, as well as subcellular localization in live cells.

Recent evidence of the colocalization of the β-actin mRNA with ribosomes in dendrites shed new light on its translation location and dynamics62. However, more direct methods are needed to detect mRNA translation. The FlAsH and ReAsH biarsenical dyes, which bind to tetracysteine motifs in engineered proteins, were used to identify sites of local translation in live cells150. Fluorescent non-canonical amino acid tagging (FUNCAT)151 or single-molecule visualization of fluorescent protein production and maturation152 can be used to assess local translation dynamics. The mp-TAG system that was developed in yeast51 can provide information on the localization of the mRNA and its protein product (Fig. 2G). Organic dye labelling of proteins such as HaloTag153 may improve imaging sensitivity and provide further information on the localization and kinetics of protein synthesis.

One key question is the functional importance of the localization of an mRNA (Fig. 1). Traditionally, mutating the zip code or RBPs involved in localization was used to study the effects of mRNA mislocalization. By using MS2-like systems to tether the mRNA to a different transport protein or to a specific location (Fig. 2D,F), it is now possible to redirect the localization of endogenous mRNAs and study the biological consequences. Combining the information on mRNA localization with that of local translation will improve our understanding of how cells are polarized and how organelles are formed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to T. Trcek, R. Lehmann and O. Amster-Choder for contributing their images for Figure 1. The authors also thank E. Tutucci, Y. J. Yoon, S. Preibisch and B. Wu for comments on the manuscript. R.H.S. is funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants NIH/NIGMS 2R01GM057071, NIH/NIBIB 5R01EB013571 and NIH/NINDS 9R01NS083085. G.H. is funded by the Gruss Lipper postdoctoral fellowship (EGL charitable foundation) (Albert Einstein College of Medicine), Dean of faculty fellowship (Weizmann Institute of Science (WIS)) and Clore postdoctoral fellowship (WIS).

Glossary

- Single-molecule FISH

(smFISH). A fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) technique that uses multiple unique short probes against a single mRNA, which greatly increases signal-to-noise ratio and enables detection of single mRNA molecules

- SNAP tag

A protein fusion tag derived from the human enzyme O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase. The protein can covalently bind to a synthetic chemical ligand that can be labelled with a fluorescent dye

- Aptamers

Short nucleic acid sequences with unique folding properties that can bind to a specific target molecule and be used for fluorescent tagging

- Myosin

A family of actin-based, ATP-dependent motor proteins

- Kinesin

A class of molecular motors that use ATP to move along microtubule filaments and that transport many cellular components. There are 14 subtypes in the kinesin superfamily, most of which transport cargo to the plus ends of microtubules

- Dynein

A motor protein family that uses ATP to transport cargo along microtubules, typically towards their minus ends. Axonemal dynein has roles in cilia and flagella, whereas cytoplasmic dynein transports mRNAs, among other cargos

- Syncytial blastoderms

A specific stage of Drosophila spp. embryogenesis during which the embryo becomes a single multinucleated cell

- Vegetal cortex

The lower pole on the animal vegetal axis of oocytes where the yolk resides

- Bud tip

The point opposite to the bud neck (which connects the bud to the mother cell) in budding yeast

- Mating type

The budding yeast has two mating types, a and α. Mating of a and α haploid cells produces a diploid cell that can later undergo meiosis to form spores. Haploid cells can switch mating types

- Processing bodies

(P-bodies). Cytoplasmic granules that contain mRNA-degrading proteins, full-length mRNAs and mRNA fragments. Their function is unclear but is related to mRNA degradation

- Synaptic plasticity

Changes in the strength of synaptic transmission in response to changes in synaptic activity, possibly during learning and memory formation

- Long-term potentiation

Long-lasting increase in the efficacy of synaptic transmission between two neurons owing to enhanced neuronal signalling or activity

- HaloTag

A protein fusion tag derived from the enzyme DhaA from Rhodococcus rhodochrous. The protein can covalently bind to a synthetic chemical ligand that can be labelled with a fluorescent dye

Biographies

Adina R. Buxbaum recently completed her doctorate in Robert H. Singer’s laboratory at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA. She is interested in mRNA trafficking and localization mechanisms in neurons and the effects of local translation in neurons on synaptic plasticity. Her thesis work investigated how the detection of single β-actin mRNAs could offer insights into their translation status using novel single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH) techniques.

Gal Haimovich was a post-doctorate fellow in Robert H. Singer’s laboratory at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA. He recently moved to Jeffery Gerst’s laboratory at the Weizmann Institute of Science (WIS), Rehovot, Israel. In his Ph.D. research he discovered that cytoplasmic mRNA decay factors directly affect transcription. He is currently investigating cell-to-cell transfer of mRNAs. He is a recipient of the Gruss Lipper family postdoctoral fellowship, the WIS Dean of faculty fellowship and Clore fellowship. Gal writes a blog on fluorescent microscopy.

Gal Haimovich’s blog.

Robert H. Singer is a co-chair and professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, USA, where he has been working for 18 years. His career has been focused on the cell biology of RNA, as well as its isolation, detection, expression and translation. A patented in situ hybridization technique developed in his laboratory for detecting RNA in morphologically preserved cells revealed that mRNA can localize in specific cellular compartments. His laboratory has been instrumental in developing rapid and sensitive microscopy techniques that can study single molecules of RNA in living cells, as well as in devising methods to track them through their life cycle. This technology has implications for understanding the role of RNA in disease processes such as cancer metastasis and cognitive impairment. He holds 12 patents on his work.

Robert H. Singer’s homepage.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Adina R. Buxbaum, Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, New York 10461, USA.. Gruss Lipper Biophotonics Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, New York 10461, USA

Gal Haimovich, Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, New York 10461, USA. Gruss Lipper Biophotonics Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, New York 10461, USA.

Robert H. Singer, Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, New York 10461, USA. Gruss Lipper Biophotonics Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, New York 10461, USA. Dominick P. Purpura Department of Neuroscience, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1300 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, New York 10461, USA

References

- 1.Weatheritt RJ, Gibson TJ, Babu MM. Asymmetric mRNA localization contributes to fidelity and sensitivity of spatially localized systems. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:833–839. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeffery WR, Tomlinson CR, Brodeur RD. Localization of actin messenger RNA during early ascidian development. Dev Biol. 1983;99:408–417. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawrence JB, Singer RH. Intracellular localization of messenger RNAs for cytoskeletal proteins. Cell. 1986;45:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melton DA. Translocation of a localized maternal mRNA to the vegetal pole of Xenopusoocytes. Nature. 1987;328:80–82. doi: 10.1038/328080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berleth T, et al. The role of localization of bicoid RNA in organizing the anterior pattern of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1988;7:1749–1756. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long RM, et al. Mating type switching in yeast controlled by asymmetric localization ofASH1 mRNA. Science. 1997;277:383–387. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.383. This is the first demonstration of mRNA localization in yeast. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garner CC, Tucker RP, Matus A. Selective localization of messenger RNA for cytoskeletal protein MAP2 in dendrites. Nature. 1988;336:674–677. doi: 10.1038/336674a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lecuyer E, et al. Global analysis of mRNA localization reveals a prominent role in organizing cellular architecture and function. Cell. 2007;131:174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cajigas IJ, et al. The local transcriptome in the synaptic neuropil revealed by deep sequencing and high-resolution imaging. Neuron. 2012;74:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeffery WR. The spatial distribution of maternal mRNA isdetermined by a cortical cytoskeletal domain in Chaetopterus eggs. Dev Biol. 1985;110:217–229. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pondel MD, King ML. Localized maternal mRNA related to transforming growth factor β mRNA is concentrated in a cytokeratin-enriched fraction from Xenopus oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7612–7616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yisraeli JK, Sokol S, Melton DA. A two-step modelfor the localization of maternal mRNA in Xenopus oocytes: involvement of microtubules and microfilaments in the translocation and anchoring of Vg1 mRNA. Development. 1990;108:289–298. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundell CL, Singer RH. Requirement of microfilaments in sorting of actin messenger RNA. Science. 1991;253:1275–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.1891715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Litman P, Barg J, Ginzburg I. Microtubules are involved in the localization of tau mRNA in primary neuronal cell cultures. Neuron. 1994;13:1463–1474. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macdonald PM, Struhl G. Cis-acting sequences responsible for anterior localization ofbicoid mRNA in Drosophila embryos. Nature. 1988;336:595–598. doi: 10.1038/336595a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yisraeli JK, Melton DA. The material mRNAVg1 is correctly localized following injection into Xenopus oocytes. Nature. 1988;336:592–595. doi: 10.1038/336592a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald PM. bicoid mRNA localization signal: phylogenetic conservation of function and RNA secondary structure. Development. 1990;110:161–171. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mowry KL, Melton DA. Vegetal messenger RNA localization directed by a 340-nt RNA sequence element in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1992;255:991–994. doi: 10.1126/science.1546297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gavis ER, Lehmann R. Localization ofnanos RNA controls embryonic polarity. Cell. 1992;71:301–313. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90358-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Litman P, Behar L, Elisha Z, Yisraeli JK, Ginzburg I. Exogenous tau RNA is localized in oocytes: possible evidence for evolutionary conservation of localization mechanisms. Dev Biol. 1996;176:86–94. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.9992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kislauskis EH, Li Z, Singer RH, Taneja KL. Isoform-specific 3′-untranslated sequences sort α-cardiac and β-cytoplasmic actin messenger RNAs to different cytoplasmic compartments. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:165–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz SP, Aisenthal L, Elisha Z, Oberman F, Yisraeli JKA. 69-kDa RNA-binding protein from Xenopus oocytes recognizes a common motif in two vegetally localized maternal mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11895–11899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrandon D, Elphick L, Nusslein-Volhard C, St Johnston D. Staufen protein associates with the 3′UTR of bicoid mRNA to form particles that move in a microtubule-dependent manner. Cell. 1994;79:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross AF, Oleynikov Y, Kislauskis EH, Taneja KL, Singer RH. Characterization of a β-actin mRNA zipcode-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2158–2165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robb DL, Heasman J, Raats J, Wylie C. A kinesin-like protein is required for germ plasm aggregation in Xenopus. Cell. 1996;87:823–831. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81990-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eliscovich C, Buxbaum AR, Katz ZB, Singer RH. mRNA on the move: the road to its biological destiny. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20361–20368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.452094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer RH, Ward DC. Actin gene expression visualized in chicken muscle tissue culture by using in situ hybridization with a biotinated nucleotide analog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:7331–7335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence JB, Singer RH. Quantitative analysis of in situ hybridization methods for the detection of actin gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:1777–1799. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.5.1777. This study reports the first optimization of FISH. The authors quantified β-actin mRNA in fibroblast by counting and normalizing autoradiography granules. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Femino AM, Fay FS, Fogarty K, Singer RH. Visualization of single RNA transcripts in situ. Science. 1998;280:585–590. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.585. This is the first demonstration of single-molecule FISH in cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raj A, van den Bogaard P, Rifkin SA, van Oudenaarden A, Tyagi S. Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nature Methods. 2008;5:877–879. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaffer SM, Wu MT, Levesque MJ, Raj A. Turbo FISH: a method for rapid single molecule RNA FISH. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e75120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levsky JM, Shenoy SM, Pezo RC, Singer RH. Single-cell gene expression profiling. Science. 2002;297:836–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1072241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jakt LM, Moriwaki S, Nishikawa S. A continuum of transcriptional identities visualized by combinatorial fluorescent in situ hybridization. Development. 2013;140:216–225. doi: 10.1242/dev.086975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Battich N, Stoeger T, Pelkmans L. Image-based transcriptomics in thousands of single human cells at single-molecule resolution. Nature Methods. 2013;10:1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang SX, Hazelrigg T. Implications for Bcd messenger-RNA localization from spatial-distribution of Exu protein in Drosophila oogenesis. Nature. 1994;369:400–403. doi: 10.1038/369400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohrmann M, et al. Microtubule-dependent recruitment of Staufen–green fluorescent protein into large RNA-containing granules and subsequent dendritic transport in living hippocampal neurons. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2945–2953. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.9.2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alami NH, et al. Axonal transport of TDP-43 mRNA granules is impaired by ALS-causing mutations. Neuron. 2014;81:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.018. This is a demonstration of altered RBP-dependent granule transport in neurons in the absence of the neuronal RBP TDP-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertrand E, et al. Localization of ASH1 mRNA particles in living yeast. Mol Cell. 1998;2:437–445. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80143-4. This is the first use of an MS2 system to follow mRNA localization in live cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beach DL, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Localization and anchoring of mRNA in budding yeast. Curr Biol. 1999;9:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brodsky AS, Silver PA. Identifying proteins that affect mRNA localization in living cells. Methods. 2002;26:151–155. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao JA, Patskovsky Y, Almo SC, Singer RH. Structural basis for the coevolution of a viral RNA–protein complex. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:103–105. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lange S, et al. Simultaneous transport of different localized mRNA species revealed by live-cell imaging. Traffic. 2008;9:1256–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hocine S, Raymond P, Zenklusen D, Chao JA, Singer RH. Single-molecule analysis of gene expression using two-color RNA labeling in live yeast. Nature Methods. 2013;10:119–121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu B, Chao JA, Singer RH. Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy enables quantitative imaging of single mRNAs in living cells. Biophys J. 2012;102:2936–2944. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu B, Chen J, Singer RH. Background free imaging of single mRNAs in live cells using split fluorescent proteins. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3615. doi: 10.1038/srep03615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrocci TJ, Hoskins AA. Imaging of RNAs in live cells with spectrally diverse small molecule fluorophores. Analyst. 2014;139:44–47. doi: 10.1039/c3an01550e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dolgosheina EV, et al. RNA mango aptamer-fluorophore: a bright, high-affinity complex for RNA labeling and tracking. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:2412–2420. doi: 10.1021/cb500499x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paige JS, Wu KY, Jaffrey SR. RNA mimics of green fluorescent protein. Science. 2011;333:642–646. doi: 10.1126/science.1207339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz ZB, et al. β-actin mRNA compartmentalization enhances focal adhesion stability and directs cell migration. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1885–1890. doi: 10.1101/gad.190413.112. Forced mRNA localization at focal adhesions demonstrates how altered mRNA localization affects cell motility. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Long RM, Gu W, Lorimer E, Singer RH, Chartrand P. She2p is a novel RNA-binding protein that recruits the Myo4p–She3p complex to ASH1 mRNA. EMBO J. 2000;19:6592–6601. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haim-Vilmovsky L, Gadir N, Herbst RH, Gerst JE. A genomic integration method for the simultaneous visualization of endogenous mRNAs and their translation products in living yeast. RNA. 2011;17:2249–2255. doi: 10.1261/rna.029637.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larson DR, Zenklusen D, Wu B, Chao JA, Singer RH. Real-time observation of transcription initiation and elongation on an endogenous yeast gene. Science. 2011;332:475–478. doi: 10.1126/science.1202142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lionnet T, et al. A transgenic mouse for in vivo detection of endogenous labeled mRNA. Nature Methods. 2011;8:165–170. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimyanin VL, et al. In vivo Imaging of oskar mRNA transport reveals the mechanism of posterior localization. Cell. 2008;134:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.053. Single-molecule imaging of an endogenous mRNA reveals a slight bias in active transport that leads to localization to the oocyte posterior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaramillo AM, Weil TT, Goodhouse J, Gavis ER, Schupbach T. The dynamics of fluorescently labeled endogenous gurken mRNA in Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:887–894. doi: 10.1242/jcs.019091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weil TT, Parton R, Davis I, Gavis ER. Changes in bicoid mRNA anchoring highlight conserved mechanisms during the oocyte-to-embryo transition. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Forrest KM, Gavis ER. Live imaging of endogenous RNA reveals a diffusion and entrapment mechanism for nanos mRNA localization in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park HY, et al. Visualization of dynamics of single endogenous mRNA labeled in live mouse. Science. 2014;343:422–424. doi: 10.1126/science.1239200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]