Abstract

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) are implicated in signal transduction, inflammation, neurodegenerative disorders, and normal aging. Net ROS release by isolated brain mitochondria derived from a mixture of neurons and glia is readily quantified using fluorescent dyes. Measuring intracellular ROS in intact neurons or glia and assigning the origin to mitochondria are far more difficult. In recent years, the protonmotive force crucial to mitochondrial function has been exploited to target a variety of compounds to the highly negative mitochondrial matrix using the lipophilic triphenylphosphonium cation (TPP+) as a “delivery” conjugate. Among these, MitoSOX Red, also called mito-hydroethidine or mitodihydroethidium, is prevalently used for mitochondrial ROS estimation. Although the TPP+ moiety of MitoSOX enables the many-fold accumulation of ROS-sensitive hydroethidine in the mitochondrial matrix, the membrane potential sensitivity conferred by TPP+ creates a daunting set of challenges not often considered in the application of this dye. This chapter provides recommendations and cautionary notes on the use of potentiometric fluorescent indicators for the approximation of mitochondrial ROS in live neurons, with principles that can be extrapolated to non-neuronal cell types. It is concluded that mitochondrial membrane potential changes render accurate estimation of mitochondrial ROS using MitoSOX difficult to impossible. Consequently, knowledge of mitochondrial membrane potential is essential to the application of potentiometric fluorophores for the measurement of intramitochondrial ROS.

Keywords: MitoSOX, hydroethidine, dihydroethidium, triphenylphosphonium, superoxide, membrane potential, ROS, Seahorse, respiration, uncoupling

1. Introduction

Central to mitochondrial function is the coupling of an electrochemical proton gradient to ATP synthesis (Mitchell, 1961). This gradient is created via a series of electron transfer reactions though complex molecular proton pumps (Nicholls and Ferguson, 2013). The four-electron reduction of oxygen to form water at cytochrome c oxidase, complex IV, is the final step in this process. Premature, one-electron reduction of oxygen to form superoxide occurs at various sites within mitochondria, primarily within the electron transport chain and tricarboxylic acid cycle enzymes in the matrix (Andreyev et al., 2005). The half-life of superoxide in cells is extremely short. Superoxide is converted to membrane permeable hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2 or MnSOD) in the mitochondrial matrix or by SOD1 (Cu/Zn SOD) in the mitochondrial intermembrane space or cytoplasm (Weisiger and Fridovich, 1973; McCord and Fridovich, 1969). H2O2 acts as a second messenger in signal transduction, e.g. by inactivating tyrosine phosphatase enzymes by sulfhydryl oxidation (Hecht and Zick, 1992; Denu and Tanner, 1998; Kamata et al., 2005). However, it also forms more reactive, toxic oxygen byproducts such as hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction (Winterbourn, 1995). In addition, superoxide reacts with nitric oxide to form the damaging reactive nitrogen species peroxynitrite (Huie and Padmaja, 1993; Zielonka et al., 2010). Mitochondrial lipid peroxidation, DNA damage, and protein oxidation are all deleterious effects of excess ROS production that are thought to contribute to neurodegeneration (Barnham et al., 2004).

Numerous techniques for measuring ROS in cells have been developed, with varying degrees of selectivity for specific reactive oxygen species. These can be grouped into several broad categories that include the monitoring of cell permeable ROS-sensitive fluorophores, the monitoring of genetically encoded ROS-sensitive fluorescent proteins, the detection of probe oxidation products by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and the measurement of ROS-sensitive endogenous enzyme activities. The first approach is amenable to live cells and allows for multiparameter imaging experiments using additional fluorophores, e.g. intracellular calcium dyes (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007).

One of the most widely used probes for evaluating changes in intracellular ROS is hydroethidine, also called dihydroethidium. Oxidation of hydroethidine by superoxide gives rise to a specific fluorescent oxidation product, 2-hydroxyethidium (Zhao et al., 2005). The reaction of hydroethidine with other molecules, including oxidation by ROS other than superoxide, yields fluorescent ethidium as well as additional, non-fluorescent byproducts such as ethidium dimers (Zhao et al., 2005; Zielonka and Kalyanaraman, 2010). The fluorescence of 2-hydroethidium is enhanced 10–20-fold by DNA whereas the increase of ethidium fluorescence in the presence of nucleic acids is higher (~20–40-fold) (Zhao et al., 2005; Olmsted, III and Kearns, 1977; Zhao et al., 2003; LePecq and Paoletti, 1967). Unfortunately, the oxidation products 2-hydroxyethidium and ethidium display a red, largely overlapping fluorescence emission spectrum (Zhao et al., 2005). As a consequence, although some excitation wavelengths, e.g. 396–408 nm, are more selective for 2-hydroxyethidium vs. ethidium (Robinson et al., 2006), the red fluorescence detected in cells is a measure of total hydroethidine oxidation due to superoxide, ROS, and other reactions (Zielonka and Kalyanaraman, 2010). HPLC must be used to quantify the superoxide-specific 2-hydroethidium oxidation product if a true index of superoxide levels is desired (Zielonka and Kalyanaraman, 2010).

Mito-hydroethidine, known commercially as MitoSOX Red, is simply hydroethidine conjugated to triphenylphosphonium cation (Robinson et al., 2006). Mitochondrial selectivity is conferred entirely by electrochemical potential; positively charged MitoSOX redistributes across the plasma and mitochondrial membranes according to its Nernst potential. When mitochondria are depolarized, e.g. in response to opening of the large non-selective permeability transition pore in the inner membrane (Kowaltowski et al., 2001), preferential mitochondrial accumulation of MitoSOX relative to the cytoplasm does not occur. Because interest in the measurement of mitochondrial ROS is most often associated with investigation of pathophysiology, this is a very important point; regardless of whether the red fluorescence detected in cells is a specific measure of superoxide or other ROS, the intracellular MitoSOX fluorescent signal cannot be attributed to ROS of mitochondrial origin if mitochondria are depolarized. Unfortunately, in the literature, intracellular MitoSOX fluorescence has been extensively quantified by flow cytometry (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2007). In the absence of parallel microscopy experiments, quantification of MitoSOX fluorescence by this method renders analysis of its subcellular distribution—and its consequent validity as a mitochondrial ROS probe under the experimental conditions employed—impossible to determine.

2. ROS Detection Using MitoSOX—Subcellular Localization and Fluorescence Yield

ROS detection by MitoSOX is in principle similar to ROS detection by hydroethidine. Mito-hydroethidine is oxidized by superoxide to mito-2-hydroxyethidium and by other ROS to mito-ethidium (Robinson et al., 2006; Zielonka and Kalyanaraman, 2010). The positively charged oxidation products are retained by polarized mitochondria and exhibit red fluorescence upon interaction with mitochondrial DNA. In addition to oxidation by ROS, photo-oxidation of MitoSOX causes formation of mito-ethidium (Zielonka et al., 2006). As a consequence, light exposure during imaging should be minimized. We recommend using the lowest concentration of MitoSOX amenable to imaging without excessive laser intensity. For primary rat cerebellar granule, hippocampal, or cortical neurons this is 0.1–0.2 μM MitoSOX. However, prior to using MitoSOX it is critical to independently optimize the MitoSOX concentration for a given cell type and experimental conditions.

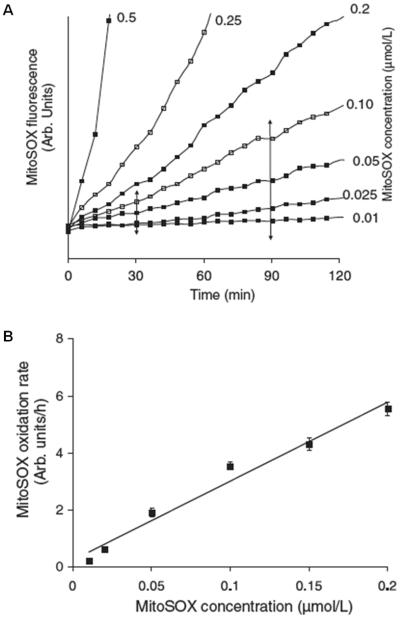

Because the fluorescence yield of oxidized MitoSOX is influenced by nucleic acid association, MitoSOX loading should not exceed the binding capacity of mitochondrial DNA. Directly measuring MitoSOX-mitochondrial DNA binding in cells is difficult. However, an indirect way to test whether mitochondrial DNA binding capacity is exceeded is by quantifying accumulated MitoSOX fluorescence as a function of its loading concentration (Fig. 1A). MitoSOX fluorescence increases in cerebellar granule neurons as a linear function of its added concentration over the range of 0.01–0.2 μM (Fig. 1B). Because MitoSOX fluorescence increases linearly without converging to a common point, it is unlikely that fluorescence enhancement by mitochondrial DNA is saturated within this concentration range. However, this does not exclude the possibility that a fraction of oxidized MitoSOX products does not associate with mitochondrial DNA (discussed further below).

Fig. 1. Establishing a linear MitoSOX concentration range.

A. Cerebellar granule neurons were loaded with 0.01–0.5 μM MitoSOX and imaged for 120 minutes. B. A linear fit of the rate of fluorescence change between 30 and 90 minutes (see A) plotted against MitoSOX concentration. MitoSOX fluorescence is expressed in arbitrary (arb.) units. Note that although throughout this chapter we often refer to hydroethidine or MitoSOX fluorescence for the sake of convenience, it should be understood that we refer to the fluorescent oxidized products rather than the compounds themselves. This figure is adapted from Fig. 4 of (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007).

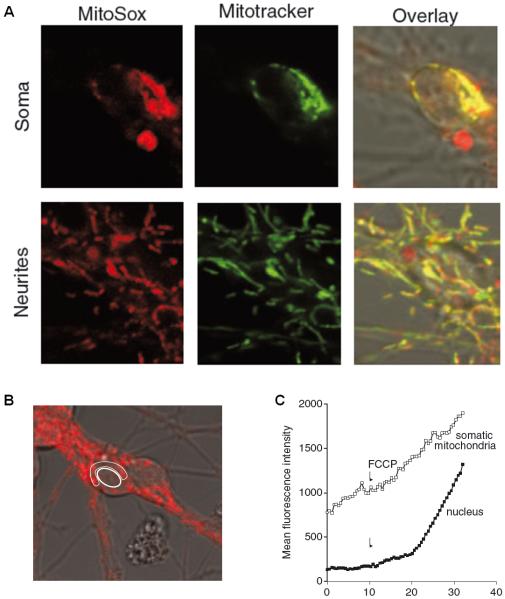

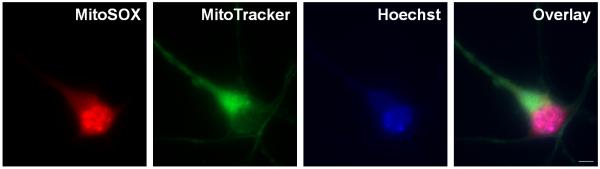

Since MitoSOX is a potentiometric fluorescent indicator, another crucial optimization step is to confirm that the probe localizes to mitochondria under the experimental conditions employed. This is readily accomplished by using a membrane potential-insensitive mitochondrially targeted dye to visualize mitochondria in live cells and testing for co-localization. The mitochondrial localization of MitoSOX is demonstrated in Fig. 2A. Primary rat cerebellar granule neurons were simultaneously loaded with MitoSOX (200 nM) and the mitochondrially targeted dye MitoTracker Green (100 nM). After a 30 minute incubation period to allow for accumulation of fluorescent oxidized MitoSOX products, MitoSOX-derived intracellular red fluorescence exhibits a similar pattern of fluorescence to MitoTracker Green (Fig. 2A, overlay).

Fig. 2. Subcellular MitoSOX localization and the effect of uncoupling.

A. Soma and neurites of cerebellular granule neurons equilibrated with 0.2 μM MitoSOX and 0.1 μM MitoTracker Green. B. Regions of interest encompassing somatic mitochondria and a cerebellar granule neuron nucleus from a single cell. C. Fluorescence intensity over time before and after FCCP addition for the regions of interest delineated in B. Panel A is adapted from Fig. 5 of (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007) and panels B and C are adapted from Fig. 9 of the same article.

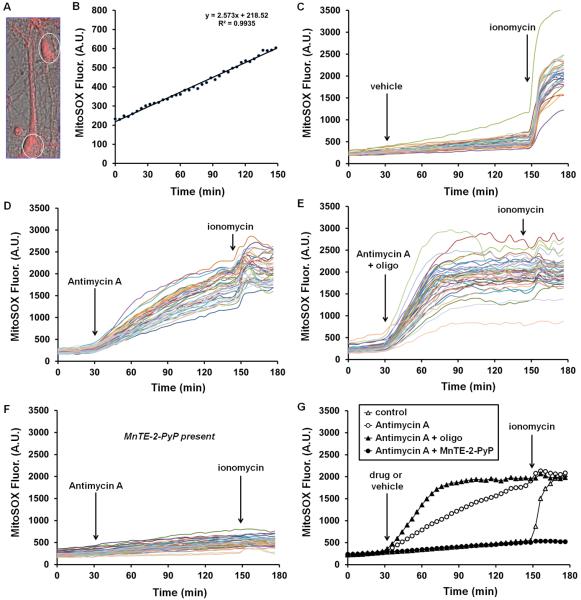

To capture MitoSOX oxidation rates within single cells, fluorescence over time in designated regions of interest corresponding to neuronal somas is quantified (Fig. 3A). In the absence of stimulation, the rate of MitoSOX fluorescence accumulation is linear for at least 2.5 hours (Fig. 3B). If high magnification is used, it is possible to subdivide a soma and quantify somatic and nuclear fluorescence. A progressive, non-linear increase in MitoSOX fluorescence is noted in the nuclei of cerebellar granule neurons upon complete mitochondrial depolarization by the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (Fig. 2B, C). The non-linear fluorescence increase could be due to an enhanced rate of MitoSOX oxidation following exposure to cytoplasmic ROS, increased fluorescence of oxidized products due to increased nucleic acid availability (e.g. nuclear DNA), or a combination of the two. Evidence from hydroethidine imaging experiments suggests that increased nucleic acid availability may be the underlying explanation (Budd et al., 1997). Although hydroethidine is neutral, the oxidized fluorescent products ethidium and 2-hydroethidium have a positive charge (Zielonka and Kalyanaraman, 2010). Consequently, the fluorescent products are accumulated by mitochondria, similar to MitoSOX, but redistribute to the nucleus upon mitochondrial depolarization. A non-linear increase in whole cell hydroethidine fluorescence following loss of mitochondrial potential was noted in cerebellar granule neurons (Budd et al., 1997). This was concentration-dependent and attributed to increased DNA accessibility by hydroethidine products (Budd et al., 1997). The same could hold true for MitoSOX, as redistribution out of the mitochondria bestows the oxidation products with increased accessibility to RNA/DNA and the associated fluorescence enhancement due to nucleic acid intercalation.

Fig. 3. The accumulation of fluorescent MitoSOX products in neurons is enhanced by the complex III inhibitor antimycin A, further enhanced by treatments that depolarize mitochondria, and inhibited by the superoxide dismutase mimetic MnTE-2-PyP.

In A, MitoSOX fluorescence is overlaid on a 63X phase contrast image of primary neurons loaded with 200 nM MitoSOX. White ovals denote typical regions of interest corresponding to cell bodies that were used for quantification of fluorescence over time. In B, the linear accumulation of intracellular fluorescent MitoSOX oxidation products in a single cell soma over a 2.5 hour time course is plotted. C–F depict the accumulation of intracellular MitoSOX oxidation products in response to C, vehicle (ethanol), D, antimycin A (1 μM), E, antimycin A (1 μM) plus oligomycin (oligo 5 μg/ml), and F, antimycin A (1 μM) in cells pre-incubated with MnTE-2-PyP (50 μM). Each trace corresponds to an individual cell and represents fluorescence over time quantified in a region of interest corresponding to the cell soma. In G, the average responses of the cells imaged in C–F are plotted. Control, antimycin A, antimycin A plus oligomycin, and antimycin A plus MnTE-2-PyP traces are averages of 30, 41, 38, and 36 cells, respectively. Results are representative of three independent experiments using primary neurons prepared on different days. A.U. refers to arbitrary units.

Unfortunately a detailed examination of how nucleic acid accessibility influences the rate and extent of MitoSOX fluorescence accumulation in cells is lacking. However, to begin to address whether mitochondrial nucleic acid content and/or accessibility limits the fluorescence yield of oxidized products, we investigated the effect of partial vs. complete mitochondrial depolarization on the total cellular MitoSOX signal using the electron inhibitor antimycin A as a positive control. Importantly, high (18 μM) but not moderate (1.8 μM) concentrations of the complex III inhibitor antimycin A were reported to increase hydroethidine fluorescence in the absence of cells (Tollefson et al., 2003), indicating the importance of using antimycin A at ≤2 μM to avoid fluorescence due to a direct interaction with mito-hydroethidine. In our hands, 1 μM antimycin A increases the rate of accumulation of MitoSOX fluorescent products in cortical neurons (Fig. 3D, G), consistent with the well-established stimulation of matrix superoxide production by this complex III inhibitor (Andreyev et al., 2005). Using mitochondrial and plasma membrane potential-sensitive dyes and modeling software, a ~22 mV antimycin-A-induced mitochondrial depolarization in cerebellar granule neurons was demonstrated (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007; Nicholls, 2006). Residual mitochondrial membrane potential during electron transport inhibition is maintained by reversal of the ATP synthase, which enables extrusion of protons from the matrix at the expense of ATP generated by glycolysis. Adding the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin together with antimycin A to prevent ATP synthase reversal and cause complete mitochondrial depolarization leads to a marked enhancement in the MitoSOX fluorescence signal compared to antimycin A treatment alone (Fig. 3E, G). Similarly, the calcium ionophore ionomycin causes an immediate, massive enhancement of MitoSOX fluorescence that leads to a rapid saturation of signal (Fig. 3C). Complete mitochondrial depolarization resulting from loss of calcium homeostasis occurs concomitantly in response to ionomycin addition (data not shown).

The dramatic enhancement of the MitoSOX fluorescence signal under conditions of full mitochondrial depolarization (antimycin A plus oligomycin or ionomycin) compared to conditions of partial mitochondrial depolarization (antimycin A alone) indicates that increased nucleic acid availability following intracellular redistribution likely contributes to the fluorescence yield of oxidized products. On the surface, this appears contradictory to the finding that MitoSOX fluorescence increases linearly over the 0.01–0.2 μM concentration range which suggests that mitochondrial DNA content is not limiting for the fluorescence yield of MitoSOX. However, because the TPP+ moiety within MitoSOX is lipophilic, it is possible that a portion of oxidized MitoSOX products partition into the inner membrane and do not associate with mitochondrial DNA. This unbound mito-2-hydroxyethidium and mito-ethidium might be minimally fluorescent but become fluorescent upon association with cytoplasmic RNA or nuclear DNA once mitochondria depolarize and the oxidized products redistribute out of the matrix. This hypothesis remains to be tested. However, regardless of whether the enhanced whole cell MitoSOX signal following depolarization is due to cytoplasmic/nuclear RNA/DNA binding or oxidation by non-mitochondrial ROS, it is clearly apparent that MitoSOX is not a quantitative indicator of mitochondrial ROS under conditions where mitochondrial membrane potential is largely dissipated.

Under conditions of partial mitochondrial membrane potential loss, e.g. the ~22 mV depolarization in response to antimycin A (Fig. 3D, G), it is uncertain to what extent the increased rate of accumulation of fluorescent MitoSOX products is due to increased MitoSOX oxidation vs. increased fluorescence of products redistributed to the cytoplasm and nucleus. If one assumes that MitoSOX rapidly redistributes across membranes and reaches a new equilibrium in response to changes in potential, similar to the cationic fluorescent dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM+), the decrease in MitoSOX matrix concentration in response to partial mitochondrial depolarization can be calculated based on TMRM+ measurements (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007). Under this scenario, significant sequestration of MitoSOX in the matrix relative to the cytoplasm persists even subsequent to antimycin A treatment due to the diminished but still substantially negative potential maintained by ATP synthase reversal. Thus, MitoSOX still detects mitochondrial matrix ROS and a correction for the altered mitochondrial probe concentration can be applied (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007). However, if the nucleic acid fluorescent enhancement of oxidation products is indeed greater in the cytoplasm/nucleus compared to in the mitochondrial matrix, oxidation of extramitochondrial MitoSOX following re-establishment of equilibrium may contribute disproportionately to the whole cell signal. Consequently, although MitoSOX can detect a qualitative change such as antimycin A-stimulated mitochondrial ROS accumulation, it should be understood that when mitochondrial depolarization occurs, mitochondrial ROS estimates are semi-quantitative at best, even when mitochondrial membrane potential corrections are applied.

3. Validating MitoSOX Using a Negative Control

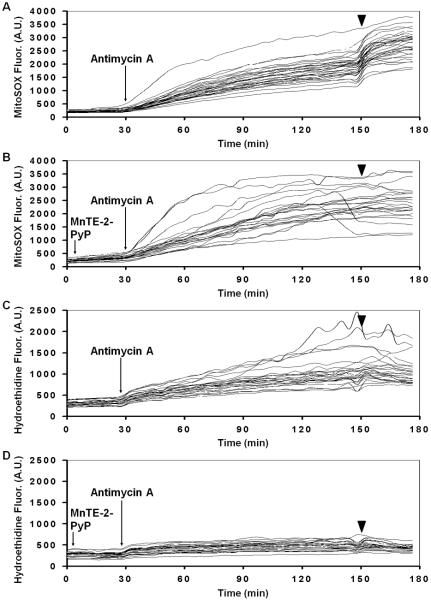

Despite the complications associated with partial mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization, antimycin A is a reasonable positive control that has been validated using isolated mitochondria (Robinson et al., 2006; Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007). A clear negative control is harder to achieve. If the red fluorescence that accumulates in MitoSOX-loaded cells is due at least in part to superoxide-specific mito-2-hydroxyethidium formation in the matrix, it should be prevented by elevating intramitochondrial superoxide dismutase activity. Cell permeable superoxide dismutase mimetic compounds such as Mn (III) tetrakis (4-benzoicacid) porphyrin chloride (MnTBAP) and Mn (III) tetrakis (N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin (MnTE-2-PyP) have been used for this purpose. When introduced to cortical neurons 10 minutes prior to MitoSOX loading, MnTE-2-PyP attenuates the increased accumulation of fluorescent oxidized MitoSOX products in response to both antimycin A and ionomycin (Fig. 3F, G). However, curiously, if neurons are loaded with MitoSOX first, followed by a 30 minute incubation with MnTE-2-PyP prior to antimycin A addition, MnTE-2-PyP fails to prevent the increased rate of fluorescent MitoSOX product accumulation stimulated by antimycin A (Fig. 4A, B). Nevertheless, MnTE-2-PyP blocks antimycin A-stimulated hydroethidine oxidation under an identical loading paradigm (Fig. 4C, D). We do not know the explanation for this unexpected finding. One possibility is that 30 minutes is insufficient time for MnTE-2-PyP to load into the mitochondrial matrix and prevent intramitochondrial MitoSOX oxidation. Another possibility is that the antimycin A-induced MitoSOX fluorescence increase is due to depolarization-induced redistribution of MitoSOX products that were already oxidized prior to MnTE-2-PyP addition. The translocation of these pre-oxidized products into the cytoplasm and nucleus would result in a consequent enhancement of fluorescence irrespective of the presence of MnTE-2-PyP antioxidant activity. Alternatively, a compound similar to MnTE-2-PyP, MnTBAP, was reported to react directly with hydroethidine to yield cationic ethidium (Zielonka et al., 2006). It is possible that MnTE-2-PyP reacts with MitoSOX in a similar fashion to form doubly charged mito-ethidium which may not enter cells. If this is the case, MnTE-2-PyP added prior to MitoSOX may effectively reduce the intracellular concentration of MitoSOX via the formation of a cell impermeable product. Mn porphyrin complexes can also absorb light at excitation and emission wavelengths commonly used for MitoSOX and hydroethidine detection (Zielonka et al., 2006), although this effect cannot explain the ability of MnTE-2-PyP to attenuate increases in MitoSOX fluorescence in Fig. 3F since the same concentration was used in Fig. 4B. Overall, data suggest that although antioxidant activity by MnTE-2-PyP likely contributes to the apparently diminished MitoSOX oxidation in Fig. 3F, quantification of intracellular MitoSOX and its oxidation products by HPLC is needed to fully understand the effects of Mn porphyrin complexes on MitoSOX fluorescence responses.

Fig. 4. MnTE-2-PyP fails to block antimycin A-stimulated accumulation of MitoSOX fluorescence when added after MitoSOX but still 30 minutes prior to antimycin A.

Vehicle (A and C) or MnTE-2-PyP (50 μM, arrow, B and D) was added after a 70 minute loading time of either MitoSOX (A and B) or dihydroethidium (C and D). The arrowhead indicates ionomycin (5 μM) addition. A.U. refers to arbitrary units.

As MnTE-2-PyP is an imperfect negative control, what alternatives exist? The commercially available mitochondrially-targeted antioxidant MitoTEMPO is one option. MitoTEMPO (25 nM) attenuated production of the superoxide-specific mito-2-hydroxyethidium MitoSOX oxidation product in endothelial cells stimulated with angiotensin II, as measured by HPLC as well as by red fluorescence (Dikalova et al., 2010). However, like MitoSOX, MitoTEMPO and related mitochondrially targeted antioxidants accumulate in mitochondria via a TPP+ delivery conjugate. As a consequence, the mitochondrial specificity of superoxide scavenging is also subject to membrane potential; antioxidant activity will not be confined to mitochondria when mitochondrial membrane potential loss occurs. Care must also be taken to ensure that tested concentrations of TPP+-conjugated molecules do not interfere with MitoSOX loading or cause mitochondrial dysfunction (Reily et al., 2013).

Genetic approaches aimed at increasing intramitochondrial antioxidant activity are another avenue. A mouse overexpressing the antioxidant enzyme catalase targeted to the mitochondrial matrix is commercially available (Schriner et al., 2005). However, catalase metabolizes hydrogen peroxide, not superoxide. Therefore its overexpression is unlikely to block MitoSOX oxidation. Although rarely employed, overexpression of the matrix superoxide dismutase MnSOD would be an excellent negative control and allow for detection of superoxide-specific MitoSOX oxidation. Provided transfected cells are fluorescently labeled, high transfection efficiency is not required. The appearance of fluorescent MitoSOX products can be quantified in MnSOD-transfected cells compared to non-transfected cells within the same field, as well as to control-transfected cells in a sister culture.

4. Choosing a Correct MitoSOX Loading Paradigm—Additional Considerations

Earlier we discussed the impact of mitochondrial DNA binding capacity and laser excitation intensity on choosing an optimal MitoSOX concentration for live-cell imaging, arriving at a range of 0.1–0.2 μM for primary rat neurons. The manufacturer recommends loading cells with MitoSOX (5 μM) for 10 minutes followed by three washes. There are at least two problems with this recommendation. The first is that potentiometric probes should be maintained in the assay medium so that equilibrium across membranes can be reached and sustained. The introduction of dye-free assay medium during washing will causes a progressive redistribution of MitoSOX out of the mitochondria as a new ionic equilibrium is slowly established. This will result in a MitoSOX matrix concentration that is dynamically changing over the course of an imaging experiment, making it impossible to accurately quantify matrix ROS levels over time and compare levels among different treatments. A second problem with this recommendation is that the influence of this high matrix MitoSOX concentration on mitochondrial function is not considered. An ideal probe will not perturb the system under study. During its initial characterization, a time-dependent redistribution of MitoSOX fluorescence to the nucleus was noted in several cell types at concentrations ≥2 μM (Robinson et al., 2006). This finding suggests that MitoSOX compromises mitochondrial function and possibly integrity if not carefully optimized. Disruption of mitochondrial function was a problem with early mitochondrial membrane potential probes, e.g. DioC6(3) inhibited mitochondrial respiration by ~90% at concentrations typically used to investigate mitochondrial potential by flow cytometry (Rottenberg and Wu, 1998). Several TPP+-conjugated probes were recently shown to cause uncoupling and respiratory inhibition in the low micromolar range (Reily et al., 2013), indicating that investigation of the influence of MitoSOX on mitochondrial bioenergetic function should be an important consideration.

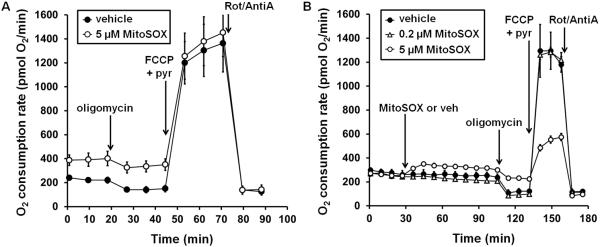

Following the manufacturer's recommendation for MitoSOX loading in primary rat cortical neurons, i.e. ten minutes of loading with 5 μM MitoSOX followed by washout, results in persistent mitochondrial uncoupling (Fig. 5A). This uncoupling of ATP synthesis from electron transport is detected as an increase in oxygen consumption rate that is insensitive to the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin, measured an hour after washout using a Seahorse Bioscience XF24 cell-based respirometer (Fig. 5A). Consistent with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential due to uncoupling, red fluorescence is predominantly nuclear when primary rat cortical neurons are loaded with 5 μM MitoSOX according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Low micromolar concentrations of MitoSOX cause mitochondrial dysfunction.

In A, primary cortical neurons were incubated with 5 μM MitoSOX or vehicle (DMSO) for 10 minutes as recommended by the manufacturer, followed by three washes in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). Baseline oxygen consumption rate measurements were acquired following a 45 minute incubation in aCSF. Oligomycin (0.3 μg/ml), FCCP (5 μM) plus pyruvate (pyr, 10 mM), and rotenone (Rot, 1 μM) plus antimycin A (AntiA, 1 μM) were sequentially injected. In B, 0.2 or 5 μM MitoSOX or vehicle was injected after three baseline oxygen consumption rate measurements. Oligomycin, FCCP plus pyruvate, and rotenone plus antimycin were sequentially added after 80 minutes of MitoSOX or vehicle exposure.

Fig. 6. MitoSOX fluorescence in cortical neurons is nuclear when following the manufacturer-recommended loading paradigm.

A cortical neuron co-loaded with MitoSOX Red (5 μM) and MitoTracker Green (100 nM) for 10 minutes followed by three washes is depicted. The nucleus is stained by Hoescht (10 μM). The scale bar is 5 μm.

In the following experiment, which we recommend when validating a MitoSOX concentration for mitochondrial ROS detection, we directly compared the effects of MitoSOX added at 0.2 μM or 5 μM on cortical neuron respiratory function in real time. The uncoupling effect of 5 μM MitoSOX was readily apparent when MitoSOX was injected during real-time measurements, reflected as an immediate rise in oxygen consumption rate and subsequent oligomycin insensitivity (Fig. 5B). In contrast, 0.2 μM, the MitoSOX concentration we employed for imaging, had no effect on mitochondrial coupling even after an 80 minute loading period. When 5 μM MitoSOX was maintained in the incubation medium, rather than washed out after 10 minutes as in Fig. 5A, inhibition of maximal mitochondrial respiration by MitoSOX also occurred (Fig. 5B). This was manifested as a reduced oxygen consumption rate measured in the presence of the uncoupler FCCP and excess mitochondrial substrate. Maximal uncoupling by FCCP eliminates control over electron transport by the ATP synthase, diffusing the proton gradient and allowing oxygen consumption to proceed at a rate limited only by the electron transport chain complexes and substrate supply. Because co-injection of 10 mM pyruvate ensured that substrate supply was not rate limiting for uncoupled respiration, the reduced oxygen consumption rate by MitoSOX-loaded neurons likely reflects direct inhibition of electron transport at one or more of the respiratory complexes. Despite the pronounced effects of 5 μM MitoSOX on mitochondrial bioenergetics, the sustained presence of 0.2 μM MitoSOX did not negatively impact neuronal respiration over the time course of a typical imaging experiment. As mitochondrial uncoupling and/or respiratory inhibition will almost certainly influence the parameter that MitoSOX is designed to detect, namely mitochondrial ROS, it is crucial to avoid concentrations of MitoSOX that impair mitochondrial energy metabolism. Detailed procedures for examining the influence of compounds on mitochondrial bioenergetic function using cell-based respirometers such as the Seahorse Extracellular Flux Analyzer are previously described and should be referred to for additional details (Jekabsons and Nicholls, 2004; Choi et al., 2009; Clerc and Polster, 2012).

5. Is MitoSOX Imaging Useful?

Given all of the complications associated with the interpretation of MitoSOX fluorescent responses, under what scenarios are potentiometric indicators of mitochondrial ROS useful? To avoid pitfalls associated with non-mitochondrially localized indicator, ideally one would want to quantify only mitochondrial regions of interest as in Fig. 2B, C. However, MitoSOX is a non-ratiometric probe that exhibits substantial cell-to-cell variability in the magnitude of fluorescence within an imaged field of cells, necessitating visualization of many cells to obtain meaningful quantitative information (e.g. see Fig. 3 and 4). Imaging MitoSOX-loaded cells under high magnification (e.g. 63x or 100x) would severely limit the number of cells that could be monitored in an individual experiment, making it impractical to try to quantify only mitochondrial regions of interest. However, imaging cells under relatively low magnification (e.g. 10x or 20x) restricts quantification of MitoSOX to cell somas. Such quantifications are most accurate in scenarios where mitochondrial and plasma membrane potentials are static and non-mitochondrial MitoSOX is consequently minimal.

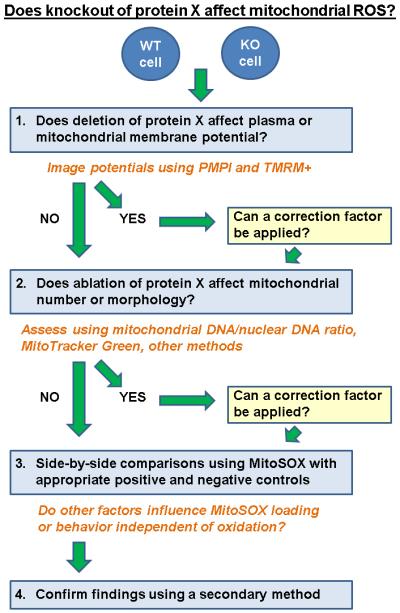

A frequent such application of MitoSOX is to assess differences in steady-state mitochondrial ROS due to an overexpressed or ablated protein, or due to an altered cell culture condition (Fig. 7). For pairwise comparisons, imaging is best conducted side-by-side with fixed microscope settings, including laser excitation intensity, stage settings, and gain. Unfortunately, the non-ratiometric nature of MitoSOX still makes comparisons of independently loaded and imaged fields of cells difficult. This can be overcome by imaging a large number of cells under each condition to average out variability due to loading. It may also be possible to use a maximal signal, such as the response to antimycin A plus oligomycin, to help normalize for MitoSOX loading, provided care is taken to ensure that responses do not saturate the detection system. Importantly, even when dynamic changes in membrane potential do not occur during the time course of an experiment, it is still important to confirm that the variable under consideration, e.g. knockout of hypothetical protein X, does not alter steady state mitochondrial or plasma membrane potentials which would affect the extent of matrix MitoSOX accumulation. A detailed protocol for simultaneously measuring mitochondrial and plasma membrane potentials using the voltage-sensitive dyes TMRM+ and PMPI, respectively, has been provided elsewhere (Nicholls, 2006; Gerencser et al., 2012). In addition to membrane potential differences being a potentially confounding factor, mitochondrial number is also an important variable to consider since whole-cell MitoSOX fluorescence is quantified. A change in mitochondrial number due to a modified rate of mitochondrial biogenesis or mitophagy could easily lead to differences in total MitoSOX loading between experimental conditions, leading to erroneous interpretation of alterations in fluorescence magnitude.

Fig. 7.

An experimental flow chart detailing application of MitoSOX to detect changes in mitochondrial ROS due to knockout of hypothetical protein X.

Another scenario where MitoSOX is often applied is to determine whether an exogenous factor, e.g. hypothetical drug Y, leads to a change in the rate of fluorescent product accumulation, implying an altered rate of mitochondrial ROS production or removal. In one respect this type of experiment is easier than the previous experiment discussed; MitoSOX oxidation rates are compared before and after a stimulus in the same cells, eliminating noise due to variable loading. However, dynamic changes in mitochondria are more likely to occur in this scenario. In addition to loss of membrane potential, events such as mitochondrial fission or fusion may cause MitoSOX dispersion or lead to altered behavior of the dye (e.g. a changed ratio of membrane-bound to DNA-bound oxidation products). Nevertheless, if mitochondrial depolarization is modest and proper negative and positive controls are employed, it is reasonable to use the fluorescent MitoSOX response as a qualitative indicator of ROS (e.g. drug Y increases mitochondrial ROS), with semi-quantitative information available if a correction factor based on membrane potential measurements is applied (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007).

All this being said, far more quantitative and easily interpretable information on mitochondrial ROS, and mitochondrial superoxide in particular, can be obtained by quantifying the oxidation products of MitoSOX by HPLC (Zielonka and Kalyanaraman, 2010). So why image MitoSOX at all? One of the most useful pieces of information that can be obtained from a live cell imaging approach is not the amount of mitochondrial ROS, but the timing of the change relative to other cellular events. MitoSOX is readily imaged in conjunction with other fluorophores, including green calcium indicators (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007). Thus, while it would be difficult to use MitoSOX to say that drug Y increases mitochondrial ROS by 4-fold, MitoSOX could easily be helpful in determining whether mitochondrial ROS increases before or after drug Y causes a rise in intracellular calcium. Since ROS are key participants in numerous cell signaling events, the ability to order mitochondrial ROS changes relative to other events in real time can provide valuable early insight into cause-effect relationships that can then later be established using additional techniques.

As with any technique, validation of findings using independent methods increases confidence in results. The mitochondrial matrix enzyme aconitase is highly sensitive to inactivation by superoxide and measurement of its activity in mitochondrial fractions is a dye/label free method of assaying changes in mitochondrial ROS (Gardner et al., 1995). In addition, although hydroethidine, the uncharged “parent” of MitoSOX, is not preferentially sequestered by mitochondria, it is sensitive to oxidation by mitochondrial ROS. The pairing of hydroethidine with a mitochondrially targeted antioxidant or matrix MnSOD overexpression can provide robust information on mitochondrial ROS changes with fewer membrane potential-associated complications.

Overall, we conclude that mitochondrial membrane potential changes are a major barrier to the implementation of potentiometric fluorophores such as MitoSOX for mitochondrial ROS detection. The fluorescent enhancement of MitoSOX oxidized products by nucleic acids such as RNA and DNA adds to the complexity of dye interpretation; consequently, potentiometric ROS-sensitive fluorophores without this property are desirable. Nevertheless, when used cautiously and in conjunction with mitochondrial membrane potential measurements, MitoSOX can still provide valuable qualitative and sometimes semi-quantitative information on mitochondrial ROS, particularly with regard to the timing of changes relative to other cellular events. A general protocol for imaging MitoSOX in primary rat cortical neurons is provided below.

6. Preparation of Primary Rat Cortical Neurons for Imaging

Embryonic day 18 primary rat cortical neurons are prepared by enzymatic dissociation of forebrain tissue using papain or trypsin followed by gentle manual trituration (5–10 strokes) using a 1 ml pipette (Yakovlev et al., 2001; Gerencser et al., 2009).

Neurons are plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in poly-D-lysine-coated Lab-Tek 8-well chambered coverglass slides (Nunc) in fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10%)-supplemented Neurobasal medium containing B27 supplement (2%), L-GlutaMAX (0.5 mM), penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

At two hours after initial plating, FBS-supplemented Neurobasal medium is replaced by serum-free Neurobasal medium and cells are maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 at 37°C. An oxygen-regulated incubator can alternatively be used to culture cells at physiologically realistic brain pO2 (2–5% O2, 15–40 mm Hg) (Erecinska and Silver, 2001; Grote et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1995; Gerencser et al., 2009).

Serum-free culture conditions reduce but do not eliminate glial contamination. If relatively pure neuronal cultures are desired (typically <5% contamination by glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive astrocytes), cytosine arabinofuranoside (5 μM) is added at 4 days in vitro (DIV) to inhibit glial proliferation (Almeida and Bolanos, 2001).

At 3–4 day intervals, one half volume of Neurobasal medium is replaced with freshly prepared Neurobasal medium. Medium “yellowing” signifies a pH drop primarily due to glycolytic lactic acid production and is an indicator that a half medium change is necessary. Note that neurons require conditioned medium for prolonged survival in culture; complete medium replacement is toxic due to the dilution of survival factors.

Embryonic neurons begin expressing functional N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors after 7–8 days in vitro (DIV) and continue to mature in culture (Frandsen and Schousboe, 1990; Peterson et al., 1989). Experiments with “mature” neurons are typically conducted at 11–15 DIV. Although neurons continue to change beyond 15 DIV in terms of glutamate receptor subunit expression levels (Stanika et al., 2009), maintaining viable neurons for greater than two weeks in culture is difficult and requires careful optimization of culture conditions.

7. Optimizing MitoSOX Concentration and Establishing Mitochondrial Localization

Insert the chambered coverglass slide containing neurons on a temperature-regulated 37°C microscope stage. Gently remove Neurobasal medium using a bent thin gel loading tip positioned in a corner of the well. Immediately wash neurons twice with 0.4 ml artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) of desired composition, taking care to add the solution slowly so as not to perturb the cells, and then add 0.4 ml of aCSF to each well. We employ aCSF consisting of 120 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 0.4 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM Na2SO4, 15 mM D-glucose and 20 mM Na-Tes, pH 7.4.

Add MitoSOX from a fresh concentrated stock prepared in DMSO at final concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1 μM. The DMSO concentration should be minimized in all experiments and the total amount following all drug additions should not exceed 0.1% if possible (Galvao et al., 2014). If an automated stage and auto-focus is available, several concentrations of MitoSOX can be tested in parallel using the 8-well chambered coverglass slide.

Allow ~70 minutes for dye loading. During this incubation period, choose fields of ~40 neurons to focus on at 10x magnification. Excite MitoSOX Red at 543 nm using a helium-neon laser, monochromator, light-emitting diode or other illumination system. Collect emission using a 585 nm cut-off filter. Adjust the laser intensity and gain so that red fluorescence is low but visible. Red fluorescence will increase over the course of an experiment due to the accumulation of oxidized MitoSOX products. Consequently, if the fluorescence intensity is initially too high, saturation of the fluorescence may occur. We find that the 70 minute loading time allows for low but visible fluorescence using a moderate (0.2 μM) MitoSOX concentration without excessive helium-neon laser intensity, however the use of different illumination systems will likely require independent optimization. Note that MitoSOX can be excited at alternative wavelengths if desired and 408 nm excitation was reported to be more specific for mito-2-hydroxyethidium vs. mito-ethidium (Robinson et al., 2006). However, cell autofluorescence can interfere at shorter wavelengths and 543 nm excitation is compatible with the simultaneous imaging of blue and green fluorophores.

Acquire images over a 90 minute period. If cycling among 8 wells using an automated stage, an acquisition rate of one image per minute will result in a data point every 8 minutes for each well of cells, resulting in limited MitoSOX photo-oxidation while providing sufficient resolution to determine whether fluorescence increases linearly over time.

Add antimycin A (1 μM) to neurons to induce an increase in mitochondrial ROS and image for an additional 30 minutes. To facilitate rapid mixing of small volumes, additions to cells during imaging can be made as follows. Drug is first added to a microfuge tube. For example, for a final concentration of 1 μM antimcyin, 4 μl of 100 μM stock is added, with 100 μM antimycin A already pre-diluted in aCSF from a more concentrated stock). Fifty μl of aCSF is removed from the well containing neurons using a bent gel loading tip and added to the microfuge tube. Drug is mixed in the 50 μl volume in the microfuge tube by pipetting up and down. The drug-equilibrated aCSF is then returned to the well by positioning the gel loading tip in a corner of the well far from the imaging field and slowly pipetting up and down to equilibrate this volume with the remaining volume. Submicroliter additions should be avoided to minimize differences due to pipetting inaccuracy.

Quantify fluorescence over time in regions of interest corresponding to neuronal somas. Plot the fluorescence change from 30–90 minutes against MitoSOX concentration as in Fig. 1. Choose the lowest MitoSOX concentration that is within a linear range and gives a readily detectable increase with antimycin A as in Fig. 3D without saturating the detection system.

If a cell-based respirometer such as the Seahorse Extracellular Flux Analyzer is available, perform the experiment illustrated in Fig. 5B to ensure that the selected MitoSOX concentration does not cause mitochondrial uncoupling or respiratory inhibition under the experimental conditions employed.

Co-load a new set of cells with 100 nM MitoTracker Green and MitoSOX at the selected concentration and loading time. Select a few cells at 63× or 100× to image.

Excite MitoSOX at 543 nm as in step 3 and excite MitoTracker Green at 488 nm using an argon laser or other illumination system. Collect emissions using a 585 nm cut-off filter and a 505–530 nm emission filter, respectively. MitoSOX fluorescence should co-localize with MitoTracker Green and be devoid of the nucleus. If nuclear staining is detected, re-optimize MitoSOX using a lower concentration. If MitoSOX/MitoTracker Green co-localization cannot be achieved, test the health of the cultures using the mitochondrial membrane potential sensitive dye TMRM+ or a cell-based respirometer.

8. Imaging using MitoSOX

Co-load neurons using the optimized MitoSOX concentration and other probe(s) of interest. Independently verify that the selected concentrations of other probes do not compromise mitochondrial function using a cell respirometer or the mitochondrial membrane potential indicator TMRM+.

Select fields of neurons for imaging as in step 3 of the above section. Adjust laser intensities and gain so that there is no crosstalk among channels. This can be achieved by imaging cells loaded with only one indicator in the non-optimal channels. For example, if imaging the green calcium indicator Fluo4-FF in conjunction with MitoSOX, load cells only with Fluo4-FF and image using 543 nm excitation/>585 nm emission to ensure there is no bleed-through of the calcium signal into the MitoSOX channel. If bleed-through is detected, reduce the laser intensity and/or gain.

Image cells over time as in step 4 of the above section, perform drug additions as desired, and quantify regions of interest as in step 6 of the above section.

In sister cultures, image cells under identical conditions using the plasma membrane potential indicator PMPI and the mitochondrial membrane potential probe TMRM+ (Nicholls, 2006; Gerencser et al., 2012). Use free software to calculate any membrane potential changes detected during the experimental time course (Nicholls, 2006; Gerencser et al., 2012) and apply correction factors for matrix MitoSOX concentration when appropriate (Johnson-Cadwell et al., 2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NINDS R01 NS085165.

References

- Almeida A, Bolanos JP. A transient inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by nitric oxide synthase activation triggered apoptosis in primary cortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 2001;77:676–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyev AY, Kushnareva YE, Starkov AA. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2005;70:200–214. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:205–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd SL, Castilho RF, Nicholls DG. Mitochondrial membrane potential and hydroethidine-monitored superoxide generation in cultured cerebellar granule cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SW, Gerencser AA, Nicholls DG. Bioenergetic analysis of isolated cerebrocortical nerve terminals on a microgram scale: spare respiratory capacity and stochastic mitochondrial failure. J. Neurochem. 2009;109:1179–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc P, Polster BM. Investigation of mitochondrial dysfunction by sequential microplate-based respiration measurements from intact and permeabilized neurons. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denu JM, Tanner KG. Specific and reversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases by hydrogen peroxide: evidence for a sulfenic acid intermediate and implications for redox regulation. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5633–5642. doi: 10.1021/bi973035t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Budzyn K, Nazarewicz RR, McCann L, Lewis W, et al. Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial superoxide in hypertension. Circ. Res. 2010;107:106–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.214601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erecinska M, Silver IA. Tissue oxygen tension and brain sensitivity to hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. 2001;128:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(01)00306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frandsen A, Schousboe A. Development of excitatory amino acid induced cytotoxicity in cultured neurons. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 1990;8:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(90)90013-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao J, Davis B, Tilley M, Normando E, Duchen MR, Cordeiro MF. Unexpected low-dose toxicity of the universal solvent DMSO. FASEB J. 2014;28:1317–1330. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-235440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner PR, Raineri I, Epstein LB, White CW. Superoxide radical and iron modulate aconitase activity in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:13399–13405. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerencser AA, Chinopoulos C, Birket MJ, Jastroch M, Vitelli C, Nicholls DG, et al. Quantitative measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential in cultured cells: calcium-induced de- and hyperpolarization of neuronal mitochondria. J. Physiol. 2012;590:2845–2871. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.228387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerencser AA, Mark KA, Hubbard AE, Divakaruni AS, Mehrabian Z, Nicholls DG, et al. Real-time visualization of cytoplasmic calpain activation and calcium deregulation in acute glutamate excitotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 2009;110:990–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote J, Laue O, Eiring P, Wehler M. Evaluation of brain tissue O2 supply based on results of PO2 measurements with needle and surface microelectrodes. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1996;57:168–172. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht D, Zick Y. Selective inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatase activities by H2O2 and vanadate in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;188:773–779. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huie RE, Padmaja S. The reaction of NO with superoxide. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1993;18:195–199. doi: 10.3109/10715769309145868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekabsons MB, Nicholls DG. In situ respiration and bioenergetic status of mitochondria in primary cerebellar granule neuronal cultures exposed continuously to glutamate. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:32989–33000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Cadwell LI, Jekabsons MB, Wang A, Polster BM, Nicholls DG. 'Mild Uncoupling' does not decrease mitochondrial superoxide levels in cultured cerebellar granule neurons but decreases spare respiratory capacity and increases toxicity to glutamate and oxidative stress. J. Neurochem. 2007;101:1619–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata H, Honda S, Maeda S, Chang L, Hirata H, Karin M. Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell. 2005;120:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowaltowski AJ, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondrial permeability transition and oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:12–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LePecq JB, Paoletti C. A fluorescent complex between ethidium bromide and nucleic acids. Physical-chemical characterization. J. Mol. Biol. 1967;27:87–106. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu KJ, Bacic G, Hoopes PJ, Jiang J, Du H, Ou LC, et al. Assessment of cerebral pO2 by EPR oximetry in rodents: effects of anesthesia, ischemia, and breathing gas. Brain Res. 1995;685:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00413-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord JM, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein) J. Biol. Chem. 1969;244:6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature. 1961;191:144–148. doi: 10.1038/191144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Yoshihiro K, Hasko G, Pacher P. Simple quantitative detection of mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;358:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG. Simultaneous monitoring of ionophore- and inhibitor-mediated plasma and mitochondrial membrane potential changes in cultured neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:14864–14874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Ferguson SJ. Bioenergetics 4. Academic Press; London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted J, III, Kearns DR. Mechanism of ethidium bromide fluorescence enhancement on binding to nucleic acids. Biochemistry. 1977;16:3647–3654. doi: 10.1021/bi00635a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Neal JH, Cotman CW. Development of N-methyl-D-aspartate excitotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1989;48:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reily C, Mitchell T, Chacko BK, Benavides G, Murphy MP, Darley-Usmar V. Mitochondrially targeted compounds and their impact on cellular bioenergetics. Redox. Biol. 2013;1:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KM, Janes MS, Pehar M, Monette JS, Ross MF, Hagen TM, et al. Selective fluorescent imaging of superoxide in vivo using ethidium-based probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:15038–15043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601945103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg H, Wu S. Quantitative assay by flow cytometry of the mitochondrial membrane potential in intact cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1404:393–404. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(98)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriner SE, Linford NJ, Martin GM, Treuting P, Ogburn CE, Emond M, et al. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science. 2005;308:1909–1911. doi: 10.1126/science.1106653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanika RI, Pivovarova NB, Brantner CA, Watts CA, Winters CA, Andrews SB. Coupling diverse routes of calcium entry to mitochondrial dysfunction and glutamate excitotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:9854–9859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903546106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefson KE, Kroczynski J, Cutaia MV. Time-dependent interactions of oxidant-sensitive fluoroprobes with inhibitors of cellular metabolism. Lab Invest. 2003;83:367–375. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000059934.53602.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisiger RA, Fridovich I. Mitochondrial superoxide simutase. Site of synthesis and intramitochondrial localization. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:4793–4796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourn CC. Toxicity of iron and hydrogen peroxide: the Fenton reaction. Toxicol. Lett. 1995;82–83:969–974. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev AG, Ota K, Wang G, Movsesyan V, Bao WL, Yoshihara K, et al. Differential expression of apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 and caspase-3 genes and susceptibility to apoptosis during brain development and after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7439–7446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07439.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Joseph J, Fales HM, Sokoloski EA, Levine RL, Vasquez-Vivar J, et al. Detection and characterization of the product of hydroethidine and intracellular superoxide by HPLC and limitations of fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:5727–5732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501719102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Kalivendi S, Zhang H, Joseph J, Nithipatikom K, Vasquez-Vivar J, et al. Superoxide reacts with hydroethidine but forms a fluorescent product that is distinctly different from ethidium: potential implications in intracellular fluorescence detection of superoxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:1359–1368. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielonka J, Kalyanaraman B. Hydroethidine- and MitoSOX-derived red fluorescence is not a reliable indicator of intracellular superoxide formation: another inconvenient truth. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:983–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielonka J, Sikora A, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Peroxynitrite is the major species formed from different flux ratios of co-generated nitric oxide and superoxide: direct reaction with boronate-based fluorescent probe. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:14210–14216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielonka J, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. The confounding effects of light, sonication, and Mn(III)TBAP on quantitation of superoxide using hydroethidine. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]