Abstract

The bloom-forming coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi (Haptophyta) is a dominant marine phytoplankton, cells of which are covered with calcareous plates (coccoliths). E. huxleyi produces unique lipids of C37–C40 long-chain ketones (alkenones) with two to four trans-unsaturated bonds, β-glucan (but not α-glucan) and acid polysaccharide (AP) associated with the morphogenesis of CaCO3 crystals in coccoliths. Despite such unique features, there is no detailed information on the patterns of carbon allocation into these compounds. Therefore, we performed quantitative estimation of carbon flow into various macromolecular products by conducting 14C-radiotracer experiments using NaH14CO3 as a substrate. Photosynthetic 14C incorporation into low molecular-mass compounds (LMC), extracellular AP, alkenones, and total lipids except alkenones was estimated to be 35, 13, 17, and 25 % of total 14C fixation in logarithmic growth phase cells and 33, 19, 18, and 18 % in stationary growth phase cells, respectively. However, less than 1 % of 14C was incorporated into β-glucan in both cells. 14C-mannitol occupied ca. 5 % of total fixed 14C as the most dominant LMC product. Levels of all 14C compounds decreased in the dark. Therefore, alkenones and LMC (including mannitol), but not β-glucan, function in carbon/energy storage in E. huxleyi, irrespective of the growth phase. Compared with other algae, the low carbon flux into β-glucan is a unique feature of carbon metabolism in E. huxelyi.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10126-015-9632-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Alkenones, Carbon partitioning, Carbon storage compound, Emiliania huxleyi, Haptophyte, Lipid biosynthesis

Introduction

Coccolithophores play an important role in global oceanic carbon cycling due to their worldwide distribution and capacity to produce huge blooms (Tyrrell and Merico 2004; Harada et al. 2012; Read et al. 2013). The cells are usually covered with calcareous scales, called coccoliths, consisting of CaCO3 crystals and acid polysaccharides (AP) called coccolith polysaccharides. Coccolithophores belong to the Haptophyta, which evolved through the secondary endosymbiosis of red algae into a non-photosynthetic eukaryotic host. During this process, many genes were transferred from the endosymbiont to the host cell. Consequently, secondary algae including coccolithophores contain mosaic genomes consisting of genes from endosymbionts and host non-photosynthetic protists (Read et al. 2013). According to recent genomic studies, the newly acquired genes from host protists contribute to the carbon metabolism of secondary algae. For example, the common coccolithophore, Emiliania huxleyi, possesses a chloroplast-localized pyruvate carboxylase (PYC) (Tsuji et al. 2012) and an enzyme set corresponding to the ornithine–urea cycle (Allen et al. 2011). In addition, the carbon metabolism of E. huxleyi is distinct from that of primary endosymbiotic algae as it yields unique photosynthetic products, such as long-chain unsaturated ketones known as alkenones, water-soluble β-glucan, and acid polysaccharides (Rontani et al. 2006; Vårum et al. 1986; Fichtinger-Schepman et al. 1981).

Alkenones are structurally unique lipids characterized by the presence of extremely long-chain carbon compounds (C37–C40) with two to four trans-double bonds and a keto-group in each molecule (Rontani et al. 2006). Several physiological functions of alkenones have been proposed, namely, as membrane components (Sawada and Shiraiwa 2004), buoyancy regulators (Fernández et al. 1996), and storage compounds (Epstein et al. 2001; Prahl et al. 2003; Eltgroth et al. 2005; Pan and Sun 2011). Recently, alkenones were proposed to be a storage compound in E. huxleyi since they accumulate in cytosolic lipid droplets under illumination, and their levels decreased under dark conditions, although no comparative evaluation with other photosynthetic products is available (Epstein et al. 2001; Prahl et al. 2003; Eltgroth et al. 2005; Pan and Sun 2011).

Unlike plants and green algae that accumulate water-insoluble α-glucan (starch), E. huxleyi produces water-soluble β-glucan, which was assumed to be a storage compound (Vårum et al. 1986). A molecule of β-glucan of E. huxleyi contains β-(1 → 6) and β-(1 → 3) linkages and is characterized by a relatively high ratio of β-(1 → 6) linkages (Vårum et al. 1986). In addition to the neutral polysaccharide β-glucan, E. huxleyi also produces another type of polysaccharide, AP, known as coccolith polysaccharide, which regulates the morphogenesis of coccoliths by controlling CaCO3 crystal growth (Fichtinger-Schepman et al. 1981). AP in E. huxleyi consists of mannose polymer as the main chain and side chains with galacturonic acid, xylose, and rhamnose with sulfate groups (Fichtinger-Schepman et al. 1981). AP is synthesized in the intracellular coccolith vesicle, embedded in the CaCO3 crystals, and then excreted onto the cell surface with the coccoliths (Van Emburg et al. 1986). Unlike β-glucan, AP is considered to be a structural component of coccoliths rather than an energy storage compound (Van Emburg et al. 1986; Kayano et al. 2011).

In addition to the macromolecules described above, some low molecular-mass compounds (LMC) appear to have an important role in energy storage in E. huxleyi. Recently, Obata et al. (2013) showed high carbon flux into mannitol compared with other sugars and amino acids and suggested that mannitol is a potential candidate storage compound.

E. huxleyi accumulates unique photosynthetic products and some, such as alkenones and β-glucan, are assumed to be metabolically active energy storage compounds. However, due to the complexity of the fate of fixed carbon, no quantitative analysis of carbon flux into these compounds in E. huxleyi has been performed. Previous studies on the synthesis of alkenones and polysaccharides were carried out independently; no quantitative data for simultaneous estimation of carbon flux into alkenones and polysaccharides in the same experiment are available. Consequently, the significance of alkenones and β-glucan as energy storage carbon compounds has not been demonstrated experimentally. This was due to the lack of a useful analytical method for fractionation of carbon storage compounds in marine microalgae, including E. huxleyi. In this study, we established the first analytical method to identify major carbon storage compounds in E. huxleyi.

Materials and Methods

Organism and Culture Conditions

The organism used in this study was the coccolithophore E. huxleyi NIES 837 (Haptophyta), which was isolated from the Great Barrier Reef in 1990. The algal cells in the stock culture have been maintained autotrophically in natural seawater enriched with Erd–Schreiber’s medium (NA-ESM), and later the soil extract component of ESM was replaced with 10 nM (final concentration) sodium selenite (modified NS-ESM). We previously found that selenite is an essential micronutrient for E. huxleyi growth, and soil extract can be replaced by 10 nM sodium selenite (Danbara and Shiraiwa 1999). The algal cells (50 ml in suspension) were maintained in a 100-ml Erlenmeyer flask under illumination by a 20-W fluorescent lamp at an intensity of 20–30 μmol m−2 s−1 with a light/dark regime of 16 h/8 h.

In the experimental culture, E. huxleyi cells were grown in medium containing the artificial seawater Marine Art SF (produced by Tomita Seiyaku Co., Ltd., Tokushima, Japan and distributed by Osaka Yakken Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan) enriched with modified ESM (MA-ESM). The composition of Marine Art SF1 was described previously (Danbara and Shiraiwa 1999). Prior to the experiments, cells were pre-cultured for 10–14 days (ca. 5–7 generations) under experimental conditions with various dilutions. Pre-cultured cells were then inoculated to fresh medium following culture to start the experimental culture. For experimental culture, algal suspension (500 ml) in a 1-l Erlenmeyer flask with an air-permeable and bacteria-free porous silicone cap was illuminated continuously by a 20-W fluorescent lamp at an intensity of 120 μmol m−2 s−1 at 20 °C. The culture was shaken by hand once per day. The pH was maintained at 8.2 by the 10-mM Tris–HCl included in the modified MA-ESM medium.

Conditions for 14C-Labeling Experiments

For the experimental culture, a portion of culture suspension (100 ml) was transferred to another culture bottle (200-ml Erlenmeyer flask) at the logarithmic (2 days after inoculation, 1.5–2.0 × 106 cells ml−1) and stationary (8 days after inoculation; 8–12 × 106 cells ml−1) growth phases. The 14C-labeling experiment was immediately started by injection of 100 μl of NaH14CO3 (3.7 MBq, 20 μM). The final concentration of dissolved inorganic carbons (DIC) was ca. 2 mM, which is the air-equilibrated level. In the light/dark transition experiments, the light was turned off and the culture bottle was immediately wrapped with aluminum foil. To analyze the time course of 14C-labeling, 20 ml of algal suspension were harvested by centrifugation (4400×g for 5 min at 4 °C) and washed with 1 ml of fresh modified MA-ESM medium for further analysis of 14C-labeled metabolites.

Fractionation of β-glucan, AP, Alkenones, and Other Compounds

To focus on 14C-labeling patterns of putative macromolecular carbon storage compounds, we established a method of separating cellular components into six fractions: (1) low molecular-mass compounds/proteins/nucleic acids (LMC/proteins/NA), (2) external acid polysaccharides located in the extracellular coccoliths (APext), (3) internal acid polysaccharides presumably located in the coccolith vesicles (APint), (4) β-glucan as a neutral polysaccharide, (5) long-chain ketones (alkenones), and (6) lipids other than alkenones.

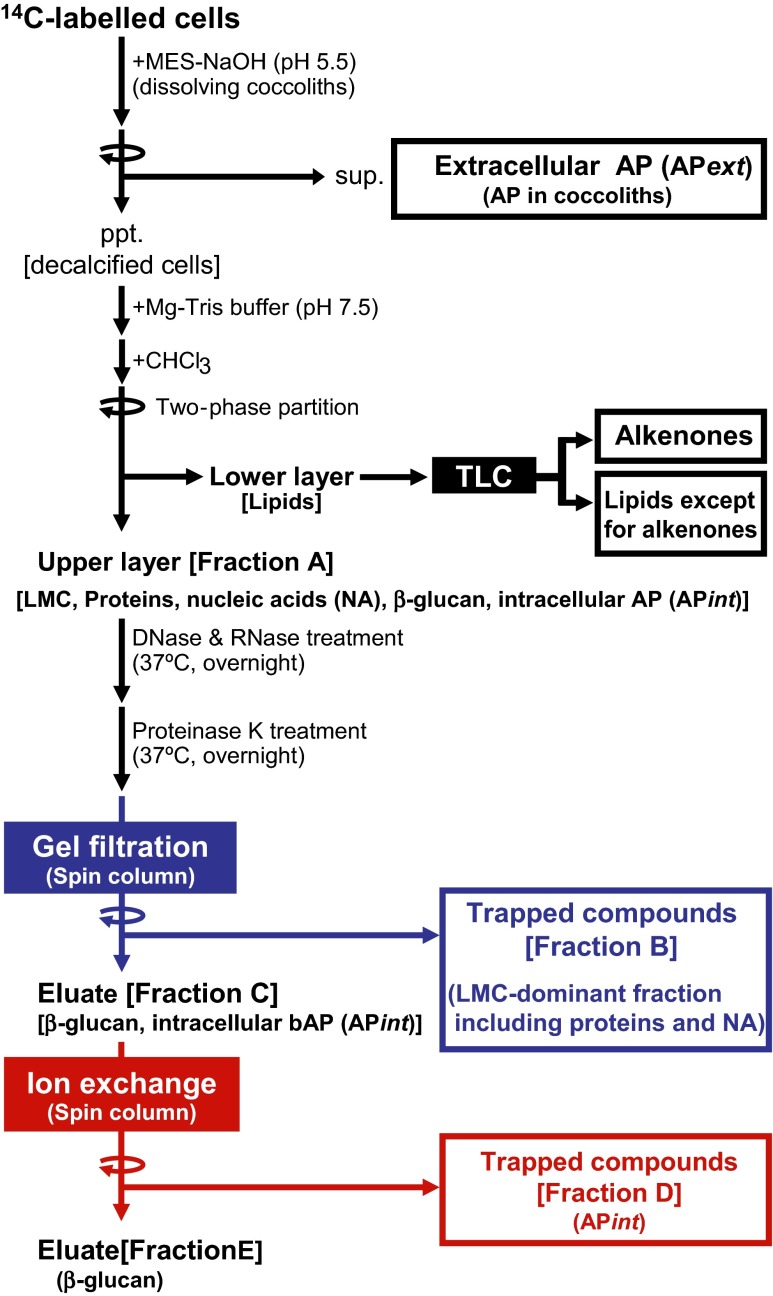

The fractionation procedure is outlined in Fig. 1. Harvested cells were washed with fresh medium as described above. The resultant cell pellets were washed with 1 ml of a decalcifying solution containing 3 % NaCl and 50 mM MES-NaOH (pH 5.5), and then treated again with 0.5 ml of the decalcifying solution to extract AP from the coccoliths (APext) by dissolving the CaCO3 crystals. After combining two supernatant fractions containing APext, the acidic fraction was exposed to an air stream overnight to remove inorganic 14C derived from Ca14CO3. After the removal of 14C-inorganic carbon, 14C radioactivity in APext was quantified using a liquid scintillation counter (LSC) (LSC-6100, Hitachi Aloka Medical, Tokyo, Japan). In the protocol of this study, 14C in CaCO3 was removed as 14CO2 by acid treatment, since we focused on fate of photosynthetically fixed carbons. Therefore, 14C incorporation into coccoliths was not determined in this study.

Fig. 1.

The novel fractionation protocol established in this study. For details, see the “Materials and Methods”

The resultant pellets containing artificially decalcified cells were mixed with Mg–Tris buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl, 8.5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) and chloroform, then separated by centrifugation into aqueous (upper part) and non-aqueous (lower part) fractions by the two-phase partitioning method: a water-soluble fraction (fraction A containing LMC/proteins/NA; Fig. 1) and a chloroform-soluble fraction (lipids). The lipid fraction was subjected to thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and developed by using hexane/ethyl acetate (9:1) as the solvent. On the autoradiogram of the TLC plate, two major 14C-labeled bands were detected (bands I and II in Fig. S1a).

To perform the analysis, we prepared a non-radioactive lipid fraction in parallel with the radioactive lipid fraction, since radioactive samples cannot be used in the gas chromatography (GC) system. Non-radioactive lipids and 14C-labled lipids were developed in adjacent lanes on TLC, then respective bands in the non-radioactive sample were marked according to the position of the radioactive bands in the adjacent lane. The marked silica gel was extracted by mixtures of hexane/ethyl acetate (95:5), hexane/ethyl acetate (9:1), and MeOH/ethyl acetate (1:1) in sequence. All extracts were then combined and concentrated by evaporation. The concentrated samples were subjected to GC using a flame ionization detector (FID) (GC-2014 AFsc, Shimadzu Seisakusho Co., Kyoto, Japan). Based on GC-FID analysis, bands I and II were identified as C38 and C37 alkenones, respectively (Fig. S1b, detailed information on the GC-FID analysis is described below). C39 alkenones were not detected in the two major bands, possibly due to the low C39 alkenone production by strain NIES837 grown at 20 °C, as reported previously (Ono et al. 2009). Therefore, the sum of 14C radioactivity in both C37 and C38 alkenones is expressed as the “alkenone fraction” in this paper.

The upper layer (fraction A) was expected to contain LMCs, proteins, NA, β-glucan, and APint. Fraction A was heated at 70 °C for 10 min to remove contaminating chloroform and obtain the “water-soluble fraction.” Then, deoxyribonuclease (10 units ml−1, final concentration) and ribonuclease (50 μg ml−1, final concentration) were added and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C overnight to degrade nucleic acids (NA) to nucleotides. Proteinase K (50 μg ml−1, final concentration) was then added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C overnight to degrade proteins to small peptides.

Next, 150 μl of the enzyme-treated samples were applied to a spin column containing Sephadex G75 gel and centrifuged in a swinging-bucket rotor at 8×g for 10 min. Polysaccharides, including β-glucan and APint (fraction C), were present in the eluate, while LMC, nucleotides, and peptides (fraction B) were trapped in the gel (Fig. 1).

The eluate (100 μl) from the Sephadex G75 gel filtration column was applied to a spin column containing DEAE-cellulose and centrifuged at 8×g for 10 min in a swinging-bucket rotor. The column was then washed with 100 μl of deionized water to elute compounds not bound completely. The combined eluate fraction contained neutral polysaccharides, namely β-glucan (fraction E), while the fraction retained in the gel contained acid polysaccharides, such as APint (fraction D).

Preparation of a Standard Sample of Alkenones

We prepared standard alkenones (shown as alkenones extract in supplemental Fig. S1) from E. huxleyi cells according to Sawada et al. (1996) with minor modifications. Briefly, cell pellets were extracted using 5 ml of MeOH with sonication, and further extracted using 5 ml of MeOH/dichloromethane (1:1) and 5 ml of dichloromethane. All extracts were combined, and n-triacontane (1 mg ml−1 at final concentration) was added as an internal standard. After the addition of water (25 ml) and saturated NaCl solution (5 ml), extracts were mixed vigorously. Lipids in the CH2Cl2 layer were passed through a column containing anhydrous Na2SO4 to remove water and then dried using an evaporator. Lipids were dissolved in 2 ml of hexane and applied onto a silica gel column. Alkenones were eluted sequentially with hexane, hexane/ethyl acetate (95/5, v/v) and hexane/ethyl acetate (9:1, v/v). All eluates were combined and evaporated, and then dissolved using small amounts of hexane for GC-FID analysis. The standard alkenones were also analyzed using GC-mass spectrometry according to the method of Nakamura et al. (2014) to identify peaks of alkenones on the GC chromatogram.

Analysis of Alkenones by GC-FID

Bands of alkenones extracted from TLC and standard alkenones were analyzed using GC (GC-2014 AFsc, Shimadzu Seisakusho Co., Kyoto, Japan) equipped with FID attached to a capillary column (length, 50 m; internal diameter, 0.32 mm; CP-Sil5 CB; Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Helium was used as a carrier at a constant flow rate of 1.25 ml min−1 in split-less mode. Temperature was programmed as follows: 60 °C for 1.5 min, an increase to 130 °C at 20 °C min−1, a further increase to 300 °C at 4 °C min−1 and holding at 300 °C for 25 min.

Evaluation of Fractionation Efficiency of Water-Soluble Macromolecules

We evaluated the fractionation efficiency of water-soluble macromolecules (included in fraction A, Fig. 1; Table S1) using commercial salmon sperm DNA and self-prepared RNA, AP, β-glucan, and 35S-labeled crude proteins as test samples. Since simultaneous quantification of these compounds in the same mixture was difficult, we performed independent assays for each compound.

To evaluate the fractionation efficiency of DNA into fractions B and C (Fig. 1; Table S1), salmon sperm DNA was used as a test sample. Salmon sperm DNA dissolved in Mg–Tris buffer, corresponding to fraction A, was subjected to enzymatic treatment and subsequent gel filtration (Fig. 1). After gel filtration, the DNA content of the eluate was determined using a NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). The fractionation efficiency was calculated by comparison of the DNA content of the initial sample and that after gel filtration. To evaluate RNA fractionation efficiency into fractions B and C, total RNA purified from E. huxleyi cells was used as the test sample.

To evaluate protein fractionation efficiency, we prepared 35S-labeled proteins from E. huxleyi cells. For this purpose, 50 ml of E. huxleyi cells were labeled with 35S-Met/Cys (24 kBq ml−1 final concentration) for 24 h under continuous illumination. After labeling, cells were harvested and subjected to two-phase partition with Mg–Tris buffer and chloroform. The upper layer (corresponding to fraction A) was fractionated into fractions B and C by enzymatic treatment and gel filtration. The 35S-protein fractionation efficiency was calculated by measuring radioactivity in the samples before and after gel filtration.

To evaluate the fractionation efficiency of AP and β-glucan into fractions B and C, we purified AP and β-glucan from E. huxleyi according to Kayano and Shiraiwa (2009). AP purified from whole cell contains APint and APext, and both APs are structurally the same with different localization patterns. Purified AP was dissolved in Mg–Tris buffer, which corresponds to fraction A, and then subjected to enzymatic treatment and subsequent gel filtration. The AP content of the samples before and after gel filtration was measured by phenol-H2SO4 assay (Kayano and Shiraiwa 2009). The β-glucan fractionation efficiency was determined using the method described except that AP was replaced by β-glucan.

To determine the AP fractionation efficiency into fractions D and E, purified AP was dissolved in deionized water and then this sample, corresponding to fraction C, was applied to the ion exchange spin column. AP contents of the initial sample and eluate were measured using phenol-H2SO4 to calculate the fractionation efficiency. Fractionation efficiency of β-glucan into fractions D and E was determined in the same manner, except that AP was replaced by β-glucan.

Proteins, DNA, and RNA in fraction A were recovered at 95, 97, and 98 % from fraction B. Removal rates of proteins and nucleic acids from the polysaccharide fraction (Ffraction C in Fig. 1) were greater than 95 % (Table S1). Neutral and acid polysaccharides, such as β-glucan and APint, respectively, in fraction C were recovered at 100 and 89 % from fractions E and D, respectively (Table S1). The total recovery rates of β-glucan and APint in fraction A were 76 and 87 % from fractions E and D, respectively (Table S1).

TLC Analysis of LMC

Cell suspension (100 ml) was labeled using NaH14CO3 as a substrate under continuous illumination. After the 24-h labeling period, cells were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in 500 μl of Mg–Tris buffer. After the addition of 500 μl of chloroform, samples were mixed vigorously and centrifuged briefly to separate the water-soluble compounds from lipids by two-phase partition. One-hundred microliters of the aqueous (upper) layer were transferred to another tube and mixed with 400 μl of methanol. Water-soluble LMC was obtained as the supernatant after precipitation of water-soluble macromolecules by centrifugation at 18,000×g for 30 min. The resultant 80 % methanol-soluble fraction was subjected to TLC analysis as the 14C-LMC fraction. To identify the 14C-mannitol spot on the TLC plate, standard mannitol (0.2 μmol, purchased from Wako Purechemical industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan; Cat. No. 133-00845) was mixed with 14C-LMC samples (ca. 3000 dpm), and then developed on TLC according to Tsuji et al. (2009). The addition of standard mannitol was essential since the amount of mannitol contained in the 14C-LMC fraction was too low to detect colorimetrically. Autoradiogram of the TLC plate was obtained using Bio-imaging Analyzer System (BAS-1800; Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). The mannitol spot was colorimetrically visualized by spraying 0.5 % (w/v) KMnO4 dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH (Bansal et al. 2008).

Results

Growth and Photosynthetic 14C Fixation in E. huxleyi

The main culture of E. huxleyi NIES837 was maintained under continuous illumination at a saturated light intensity (120 μmol photons m−2 s−1) without bubbling. To allow for gas exchange, 500 ml of cell suspension was cultured in a 1-l Erlenmeyer flask with a gas-permeable cap. Medium contained 10 mM Tris and the initial pH of the culture was set at 8.2. Therefore, the concentration of DIC is expected to be at near air-equilibrium levels (ca. 2 mM). Artificial seawater (Marine Art SF-1) enriched with modified Erd–Schreiber’s medium (modified MA-ESM, Danbara and Shiraiwa 1999), which contains 1.9 mM NO3− and 28 μM inorganic phosphate (Pi), was used. Since light intensity given during photosynthetic 14C-fixation assay was saturated, nutrient limitation, such as inorganic phosphate and nitrate, can be considered to be major factor affecting carbon allocation pattern in LP and SP cells.

Aliquots (100 ml) of cells were withdrawn from the main culture at the logarithmic and stationary growth phases to prepare LP and SP cells, respectively (Fig. 2a). Cells were immediately transferred to other subculture glass vessels for photosynthetic 14C-labeling experiments under continuous illumination (Fig. 2b, c). Conditions for labeling experiments were identical those in the main culture, except that 100 ml of cell suspensions was cultured in a 200-ml Erlenmeyer flask. To start the 14C-labeling experiments, NaH14CO3 was injected as a substrate into the vessels. Total 14C-incorporation proceeded linearly for 24 h in both LP and SP cells, although 14C-bicarbonate concentration in the medium decreased to ca. 50 % of the initial value (Fig. 2b). The rate of 14C-fixation (dpm cell−1 h−1) calculated on a cell basis was 2.7-fold higher in LP than SP cells, showing that LP cells are more photosynthetically active than SP cells (Fig. 2c). While SP cells still had some activity of carbon fixation (Fig. 2c), cell division of SP cells was arrested probably due to the limitation of nutrients (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Growth curve of the main batch culture without bubbling or shaking and the time course of photosynthetic 14C fixation in the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi NIES837. a Algal growth curve of the main culture. The culture (500 ml) was maintained under continuous illumination at 120 μmol photons m−2 s−2. At the logarithmic (LP cells) and stationary (SP cells) growth phases, an aliquot (100 ml) of the culture was transferred to a fresh subculture flask for 14C labeling. b Time courses of changes in 14C remaining in the medium (open symbols) and 14C incorporated into cells (closed symbols) in LP (diamonds) and SP cells (triangles). c Time courses of 14C fixation (calculated as dpm per cell) for LP cells (closed diamonds) and SP cells (closed triangles). The photosynthetic rates were 0.13 and 0.05 dpm cell−1 h−1 in LP and SP cells, respectively. Values are means ± SD of three independent experiments. For details of 14C-labeling experiments, see the “Materials and Methods.” The temperature was maintained at 20 °C during both culture (a) and 14C-labeling (b, c)

Establishment of a Fractionation Method for Quantitative Estimation of 14C Incorporation into Major Photosynthetic Products in E. huxleyi

We developed a fractionation protocol for macromolecules as major photosynthetic products in E. huxleyi cells (Fig. 1). According to this method, 14C products were fractionated into the following six portions: (1) APext which is embedded in or surrounding the coccoliths displayed on the cell surface, (2) the LMC-dominant fraction which contains mainly primary photosynthetic metabolites and mannitol together with minor contamination by proteins, nucleic acids (NA), APint and β-glucan (see Supplementary Table S1), (3) APint which is located in intracellular coccolith-producing vesicles, (4) β-glucan, which is neutral polysaccharide, (5) alkenones which are neutral lipids, and (6) lipids except alkenones (Fig. 1).

In this method, water-soluble macromolecules (Fraction A, Fig. 1) were separated into fractions B to E. We evaluated the fractionation efficiency of compounds using commercial salmon sperm DNA (purchased from Sigma-zAldrich Chemical, St. Louis, MO; Cat. No. D1626) and self-prepared RNA, AP, β-glucan and 35S-labeled crude proteins as standard test samples (Supplementary Table S1; see the “Materials and Methods” for details). During preparation of fractions B and C, more than 95 % of DNA, RNA, and proteins were present in fractions A and B, while 87 and 85 % of β-glucan and AP, respectively, were recovered in fraction C (Table S1).

The content of 14C-LMC in fraction B was independently estimated by omitting enzymatic degradation of proteins and NA (see the Materials and Methods; Fig. S2). Following 24 h 14C-labeling of SP cells, 14C-LMC comprised ca. 75 % of 14C in fraction B; the remainder (25 %) comprised the sum of 14C-proteins, 14C-NA, and 14C-polysaccharides (Fig. S2). According to the fractionation efficiencies shown in Table S1, 14C-proteins (95 %), 14C-DNA (97 %), 14C-RNA (98 %), 14C-β-glucan (13 %), and 14C-APint (15 %) (% of the total 14C in each component) were estimated to be fractionated from fraction A into fraction B.

Trends in 14C Incorporation into Major Photosynthetic Products

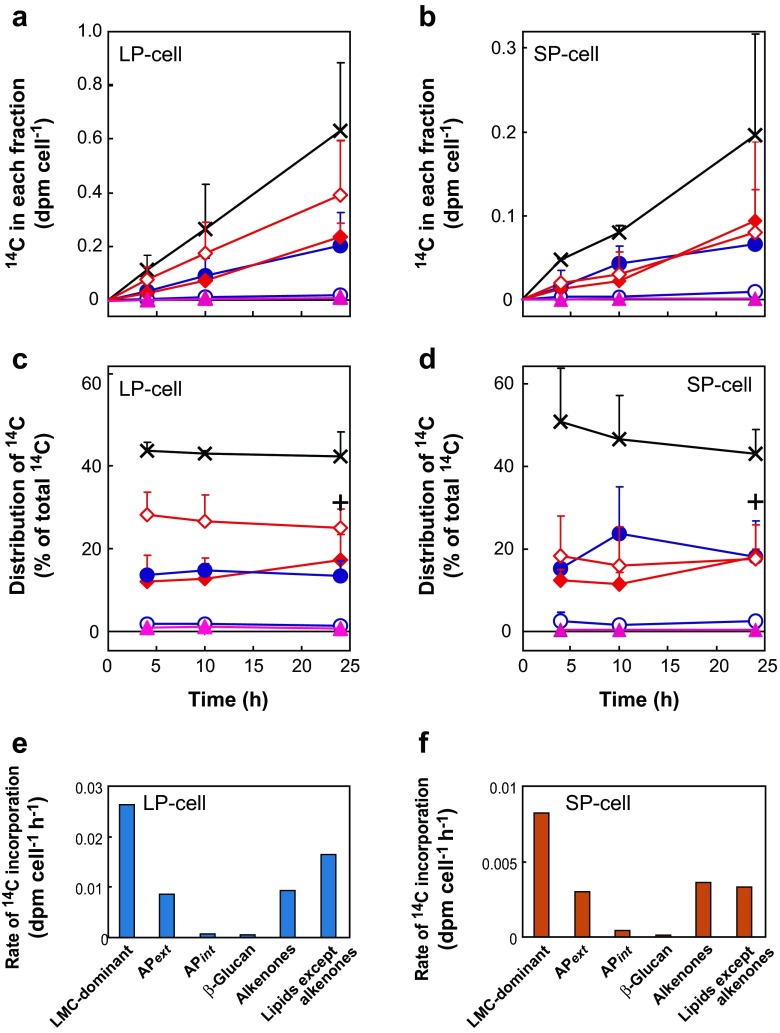

After fractionation of 14C-labeled photosynthetic products according to the method established in this study (Fig. 1), 14C radioactivity in each fraction was determined separately. 14C incorporation into all fractions increased linearly in both LP and SP cells, although the rates were higher in LP than SP cells (Fig. 3). 14C was mostly incorporated into the LMC-dominant fraction (fraction B), with ca. 40 and 45 % of total 14C fixation in LP and SP cells, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). According to the fractionation data, in which 24-h 14C-labeled cells were used as test materials (Supplementary Table S1), 14C-LMC occupied ca. 75 % of 14C in the LMC-dominant fraction (Supplemental Fig. S2). Finally, we calculated that 14C-LMC accounted for ca. 35 and 33 % of total 14C fixation in LP and SP cells, respectively (plotted as a plus (+) in Fig. 3c, d).

Fig. 3.

Photosynthetic 14C incorporation into various fractions of LP (a, c, e) and SP cells (b, d, f) of the coccolithophore E. huxleyi NIES 837. a, b 14C incorporation (dpm cell−1) into various fractions. c, d 14C distribution (% of total 14C fixation) into each fraction. Crosses LMC-dominant fraction including 14C-proteins and 14C-NA as minor components; plus sign 14C-LMC value calculated from data obtained separately, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2 (ca. 75 % of 14C in LMC-dominant fraction comprised 14C-LMC after 24 h 14C-labeling.); closed circles extracellular acid polysaccharides (APext); open circles intracellular acid polysaccharides (APint); closed diamonds alkenones; open diamonds lipids other than alkenones; closed triangles β-glucan. Values are means + SD of three independent experiments. e, f Rates of 14C incorporation (dpm cell−1 h−1) into the various fraction in LP and SP cells, respectively. For time courses of total 14C fixation in LP and SP cells see Fig. 2. Values are means + SD

Lipids other than alkenones were the second most dominant products, containing 25–30 % of the total 14C-fixed in LP cells. This lipid fraction is expected to contain mainly membrane lipids and photosynthetic pigments. However, it contains no or only minor amounts of triacylglycerol (TAG), which is the major storage lipid in most microalgae, as reported by Volkman et al. (1986). We did not perform further analysis of 14C-polar lipids since these polar lipids are components of membranes. The composition of polar lipids in E. huxleyi has been reported previously (Bell and Pond 1996). The third most dominant products were alkenones and APext, which each represented ca. 18 % of total 14C fixation in LP cells (Fig. 3a, c). The percentage 14C incorporation into whole lipids other than alkenones and APext was almost identical, ca. 20 % of total 14C fixation in SP cells (Fig. 3c, d). Little 14C-labeled APint or β-glucan was produced by either LP or SP cells (Fig. 3).

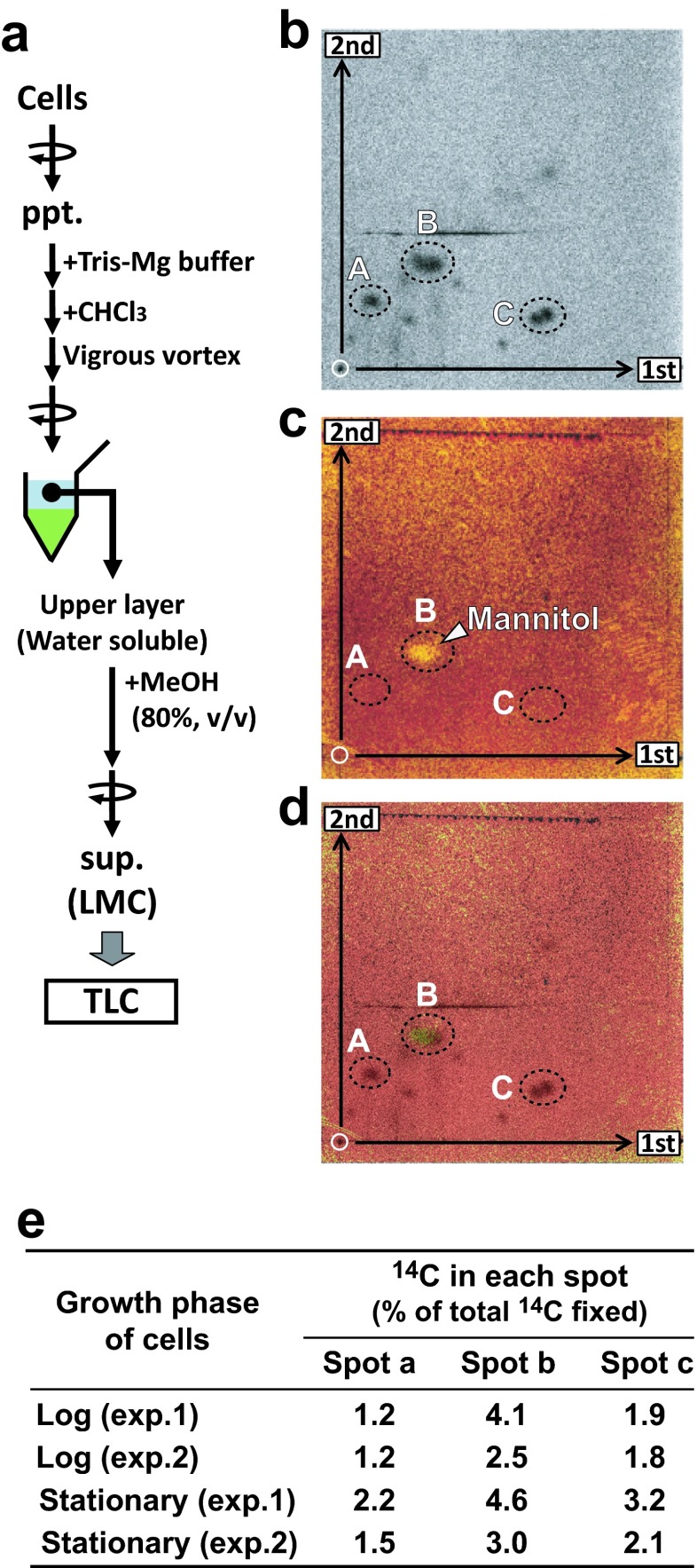

TLC Analysis of the 14C-LMC-dominant Fraction

Obata et al. (2013) suggested that mannitol is used for carbon storage in E. huxleyi. To estimate the contribution of mannitol to the LMC-dominant fraction, we analyzed the molecular composition of 14C-LMC by thin-layer chromatography. However, detailed analysis of 14C-LMC was difficult since LMC is trapped by the gel in the spin column in the new fractionation method (Fig. 1). Therefore, we used another fractionation method to analyze 14C-LMC, namely, extraction using the water/chloroform two-phase partitioning method followed by 80 % methanol extraction (Fig. 4a). To identify the mannitol spot, commercial standard mannitol was added to 14C-LMC samples for simultaneous detection of 14C-spots and mannitol spots on the same TLC plate (Fig. 4b–d) (see the Materials and Methods). Three major 14C-spots appeared on the autoradiogram (spot A–C) and mannitol was detected as spot b (Fig. 4b–d). 14C in all spots was less than 5 % of total 14C-fixation (Fig. 4e). However, as the mannitol spot appeared to be multiple spots, further detailed quantitative analysis is necessary for high-quality estimation.

Fig. 4.

Two-dimensional TLC analysis of 14C-LMC produced by the coccolithophorid E. huxleyi NIES 837 under continuous illumination for 24 h. a Fractionation protocol for the preparation of LMC for TLC analysis. b Autoradiogram. c Mannitol spot (shown by arrow) visualized by KMnO4 reagent. d A merged image of the autoradiogram (b) and chemical staining of mannitol (c). The TLC images presented here are representative of two independent experiments using LP cells. e Quantification of 14C-mannitol (expressed as % of total 14C fixation). Results of two independent experiments (exp. 1 and 2) are shown

Analysis of 14C-lipids

Lipids were separated into a chloroform-soluble fraction; i.e., the lower layer in the chloroform/water two-phase partitioning method (Fig. 1). When the lipid fraction was analyzed by TLC, two major radioactive spots in bands I and II were identified (Supplementary Fig. S1). Using gas chromatography (GC) analysis, bands I and II were identified as C38 and C37 alkenones, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1b). C39 alkenones were not detected in the two major bands, possibly due to the low C39 alkenone production by strain NIES837 grown at 20 °C, as reported previously (Ono et al. 2009). The sum of C37 and C38 alkenones identified and quantified using TLC was expressed as “alkenones” in the present study. The alkenones accounted for ca. 17 % of total 14C-fixation in the 24-h 14C-labeling experiment in both LP and SP cells, while the 14C ratios in lipids other than alkenones were 25 and 18 % in LP and SP cells, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). Although we did not quantify the amount of TAG, there were no major bands of TAG in our TLC analysis, indicating no TAG qualitatively. These results are same as that in previous reports (Volkman et al. 1986; Eltgroth et al. 2005).

Analysis of the 14C-polysaccharide Fraction

The polysaccharide fraction was divided into three subfractions, APext and APint for acid polysaccharides and β-glucan as a neutral polysaccharide (Fig. 1). 14C-β-glucan comprised only 0.8 and 0.4 % of total 14C fixation in LP and SP cells, respectively (Fig. 3), despite its being assumed previously to be a storage compound in E. huxleyi. 14C-APint, presumably located in the coccolith vesicles, comprised 1.3 and 2.5 % of total 14C fixation in LP and SP cells, respectively, whereas 14C-APext, synthesized intracellularly and then excreted to the cell surface with coccoliths, comprised 13 and 18 % of total 14C fixation in LP and SP cells, respectively (Fig. 3c, d). Total 14C-AP (APint + APext) comprised 14 and 20 % of total 14C fixation in LP and SP cells, respectively.

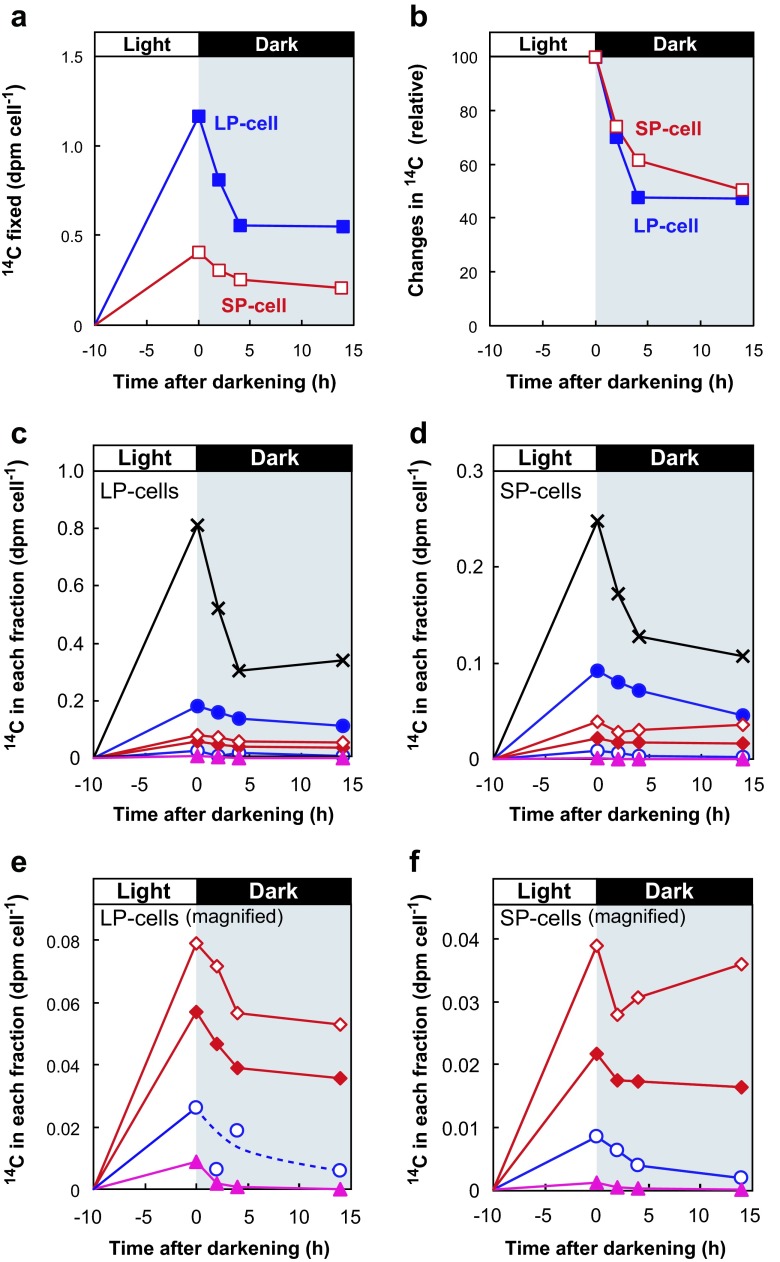

Catabolism of 14C-Labeled Compounds in the Dark in Light/Dark Transient Experiments

To evaluate utilization of photosynthetic 14C-products in the dark, E. huxleyi cells were transferred from light to dark conditions. After transition to dark conditions, total 14C in cells decreased rapidly and reached a steady level after a 4-h incubation in the dark in both LP and SP cells (Fig. 5a, b). Immediately following the transfer of cells from light to dark conditions, the 14C-LMC-dominant fraction, of which mannitol comprises ca. 16 % corresponding to 5 % of total 14C-fixation, decreased rapidly. 14C-alkenones decreased to ca. 70 % of the initial level during the first 4 h of incubation in the dark. These trends were similar in both LP and SP cells (Fig. 5c, d).

Fig. 5.

Changes in 14C in various fractions during light/dark transition in the coccolithophore E. huxleyi NIES837. First, cells were photosynthetically labeled with 14C using NaH14CO3 as the substrate for 10 h, and then transferred to dark conditions. a Changes in 14C incorporation into LP cells (closed squares) and SP cells (open squares) expressed as actual radioactivity (dpm cell−1). b Relative amount of 14C under dark conditions (% change) in LP (closed squares) and SP cells (open squares), respectively. c, d Changes in 14C incorporation into each metabolite in the LMC-dominant fraction (crosses), APext (closed circles), lipids other than alkenones (open diamonds), alkenones (closed diamonds), APint (open circles), and β-glucan (closed triangles) expressed as actual activity (dpm cell−1) in LP and SP cells, respectively. e, f Graphs with magnified y-axis of Fig. 5c, d for lipids other than alkenones (open diamonds), alkenones (closed diamonds), APint (open circles), and β-glucan (closed triangles) in LP and SP cells, respectively. Representative results of two independent experiments are shown

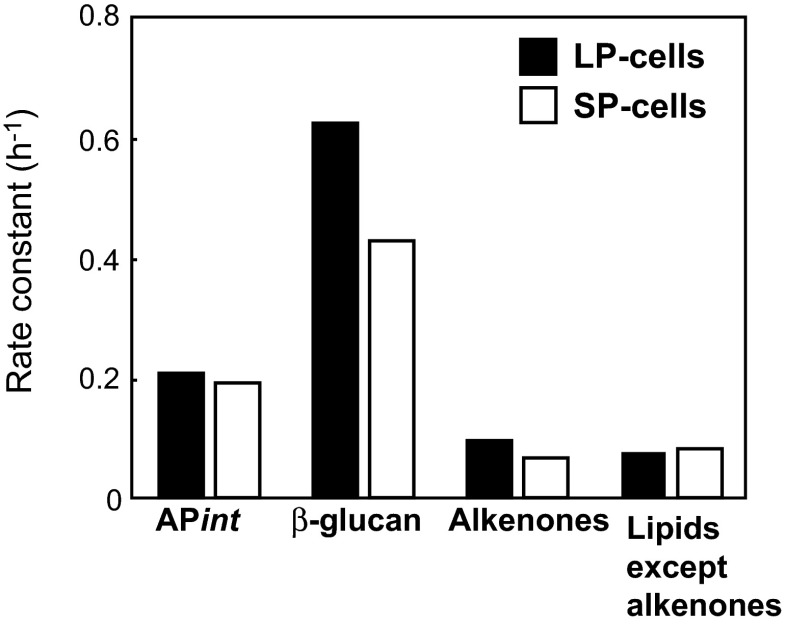

Since most 14C-labeled major fractions decreased exponentially during the first 4 h of incubation under dark conditions, 14C decreases of intracellular macromolecules were fit to exponential curves to calculate the rate constant using the following equation: R (t) = R0e−kt (Fig. 6; Supplemental Fig. S3). In this equation, R0 and R (t) represent the radioactivity of 14C in each fraction (dpm cell−1) at time 0 and t, respectively. k is the rate constant of the degradation reaction. The rate constant of β-glucan was considerably higher than that of other intracellular macromolecules in both LP and SP cells (Fig. 6). These results showed a marked difference between β-glucan and alkenones as storage compounds, namely, alkenones function as a slowly degradable large carbon pool while β-glucan functions as a rapidly degradable small carbon pool. β-glucan cannot be considered a major carbon/energy storage compound since it is present at extremely low concentrations (Figs. 3 and 5e, f). The actual calculated concentrations of 14C released from alkenones during the first 4 h of incubation under dark conditions were two- and fivefold greater than that of β-glucan in LP and SP cells, respectively (Fig. 5e, f).

Fig. 6.

Rate constant of the decrease in 14C in intracellular macromolecules during a 4-h dark period in LP (solid bars) and SP cells (open bars). To calculate the rate constant, 14C decrease in each fraction was fit to exponential curves using the following equation: R (t) = R 0 e −kt. In this equation, R 0 and R (t) are 14C-radioactivities in each fraction (dpm (103 cells)−1) at time zero and t, respectively. k rate constant. Data in Fig. 5c, d were used for calculations

Discussion

Low Carbon Flux into β-glucan Is a Feature of Carbon Metabolism in E. huxleyi

Carbon metabolism in the haptophyte alga E. huxleyi, a secondary endosymbiotic alga, is distinguished from that in primary endosymbiotic algae by the production of unique photosynthetic products, such as alkenones, AP, and β-glucan. Here, we revealed that 17 % of fixed 14C is distributed to alkenones, while 14C in β-glucan was less than 1 % in both LP and SP cells (Fig. 3). This result demonstrated that fixed carbons are stored mainly as C37 and C38 alkenones, not as β-glucan. Another potential carbon storage resource is the LMC fraction, which accumulated ca. 30 % of cellular 14C, but contains various components (Fig. 3).

Generally, carbohydrates such as α/β-glucans are known to be major storage compounds stored during photosynthesis and preferentially utilized as primary energy/carbon sources in the dark in many phytoplankton species, while lipids play a role in slow, degradable carbon storage (Ricketts 1966; Handa 1969). However, our results demonstrate that β-glucan is not a major energy/carbon storage in E. huxleyi since 14C-flux into β-glucan for storage was extremely low, and therefore the amount of degradation was also very low (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S3).

In diatoms, which are known to have evolved through secondary endosymbiosis of red alga, both synthesis and accumulation of β-glucan was stimulated under nutrient limited conditions, especially N-limitation (Myklestad 1989). In a diatom Skeletonema costatum, ca. 30 % of fixed 14C was incorporated into β-glucan in LP cells, and the value was higher in SP cells (Myklestad 1989). These trends are opposite to those observed in the coccolithophore E. huxleyi.

We previously reported that availability of inorganic phosphate (Pi) regulates carbon flux between β-glucan and AP in E. huxleyi (Kayano and Shiraiwa 2009). When Pi is sufficient, β-glucan synthesis is stimulated while AP synthesis is suppressed (Kayano and Shiraiwa 2009). This tendency was also observed in the present study; 14C in β-glucan of LP cells was twofold that in SP cells (Fig. 3c, d; 0.8 % in LP cells and 0.4 % in SP cells). According to these results, E. huxleyi synthesizes β-glucan when nutrients are sufficient. Although β-glucan is rapidly produced even in E. hyxleyi LP cells, the amount of 14C flux into β-glucan was much lower than that in diatoms. This result suggested that low carbon flux into β-glucan is a potent physiological property of E. huxleyi. However, it remains possible that β-glucan synthesis becomes dominant under specific conditions.

We demonstrated that β-glucan is not the major carbon/energy storage molecule in E. huxleyi. These features are not common in all coccolithophorids since the non-alkenone-producing coccolithophore, Pleurochrysis haptonemofera, produces β-glucan as the major carbon storage molecule (Hirokawa et al. 2008). The present study observed differences in the function of β-glucan between alkenone-producing and non-alkenone-producing coccolithophores.

Alkenones Function in Storage in E. huxleyi

14C flux into alkenones were ca. 17 % in both LP and SP cells, demonstrating that alkenones are the major carbon/energy storage macromolecule in E. huxleyi. Alkenones were constantly synthesized through cell growth, suggesting that alkenone synthesis is not regulated by nutrient conditions. This result is consistent with previous studies showing the constant ratio of alkenones to total organic carbon in LP and SP cells of E. huxleyi (Conte et al. 1998). We showed constant biosynthesis of alkenones (Fig. 3), while coccolith production is enhanced by Pi-limitation (Kayano and Shiraiwa 2009). Therefore, alkenones are unlikely to function as a buoyancy regulator to compensate for the heaviness of coccoliths, since coccolith biosynthesis and alkenone biosynthesis are regulated independently.

In the natural environment, E. huxleyi may be exposed to dark periods of various lengths depending on their ecosystem conditions. By means of a dark incubation experiment that evaluated the alkenone degradation rate (Fig. 5), we demonstrated that alkenones are actively metabolized and can function as a carbon/energy source during the daily light/dark cycle. In addition to our data on short-term experiments (Fig. 5, several hours of dark period), the degradation of alkenones was observed in darkness after several days (Epstein et al. 2001; Prahl et al. 2003; Eltgroth et al. 2005; Pan and Sun 2011) and 25 % of alkenones remained after 5 days of darkness (Prahl et al. 2003). Considering the global distribution of E. huxleyi, alkenones may play key roles as important carbon storage molecules during circulation-mediated vertical transport of algal cells to 100–200 m depths.

Fernández et al. (1996) reported the reallocation of 14C from total lipids to proteins under dark conditions, although alkenones were not examined independently. It is possible that stored alkenones are used not only for energy but also serve as a carbon source for protein synthesis under dark conditions in E. huxleyi. Patterns of 14C incorporation into lipids other than alkenones were similar to those for alkenones, especially in LP cells (Fig. 5e). Similarly, lipids other than alkenones, including polar lipids and pigments, which are components of membranes, may function in carbon and energy storage.

What is the advantage of accumulating alkenones as storage compounds? Triacylglycerol (TAG) is a general storage lipid in various microalgae (Yoshida et al. 2012), but E. huxleyi produces only trace amounts of TAG (Volkman et al. 1986). In comparison with TAG, the unique features of alkenones are their extremely long carbon chain lengths (C37–C39), the keto-group, and trans-double bonds. Rontani et al. (1997) showed that trans-unsaturated alkenones are more resistant to photochemical degradation than other lipids with cis-unsaturated bonds. E. huxleyi frequently produces blooms at the ocean surface where it is exposed to very high irradiance (Tyrrell and Merico 2004); the high resistance of alkenones to photochemical degradation may be advantageous under such conditions (Rontani et al. 1997). E. huxleyi is exposed to various environmental conditions from high irradiance to prolonged dark periods according to climate change and vertical mixing. The photostability of alkenones is likely important for this organism to adapt to sudden changes in the light environment. However, further direct analysis is required to support this hypothesis.

Mannitol and LMC Function as Water-Soluble Carbon Storage Molecules in E. huxleyi

Recently, Obata et al. (2013) suggested that some LMCs, such as mannitol, could act as storage compounds in E. huxleyi. In the present study, almost 40 % of total 14C-fixed was incorporated into the LMC-dominant fraction (Fig. 3). 14C-mannitol was estimated to comprise less than 5 % of total 14C-fixed, which is ca. 30 % of the 14C in alkenones. Obata et al. (2013) analyzed 13C flux into LMC including mannitol, but no data on macromolecules are available. On the other hand, our analysis provided quantitative data on 14C flux into mannitol and alkenones and revealed that 14C flux into alkenones was higher than that into mannitol by comparing the production profile of both metabolites (Fig. 3). The 14C incorporation into the LMC-dominant fraction was not saturated within the 24-h labeling period (Fig. 3), suggesting that LMC has a large capacity for carbon storage. We consider that not only mannitol but also the whole pool of LMC may function in carbon storage in combination with alkenones. Linear 14C incorporation into the LMC fraction in the marine brown alga Eisenia bicyclis, which accumulates high amounts of mannitol as a storage compound, has been reported (Yamaguchi et al. 1966). These trends differ from other reports that 14C incorporation into photosynthetic primary intermediates generally attains a steady level on the order of minutes to an hour, as in the freshwater cryptophyte Chroomonas sp. (Suzuki and Ikawa 1985) and freshwater chlorophyte Chlorella vulgaris (Miyachi et al. 1978; Nakamura and Miyachi 1982). The biosynthetic pathway for mannitol in brown algae was revealed as photosynthetic synthesis via C3-intermediates produced in the Calvin–Benson cycle, hexose phosphate, and mannitol-1-phosphate (Yamaguchi et al. 1969).

In the present study, we showed high 14C-flux into LMC in the light and a rapid decrease in 14C-LMC in the dark. However, further studies are required to identify other LMC and their metabolic profiles to clarify how mannitol and other LMCs function in carbon storage. Mannitol has various functions, including as a storage compound, compatible solute, energy source to regenerate reducing power, and agent for scavenging reactive oxygen species, in various algae (Iwamoto and Shiraiwa 2005). In addition to mannitol, several other major unidentified 14C compound spots were found by TLC (Fig. 4b). These compounds may include dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), as E. huxleyi is known to synthesize DMSP as a compatible solute (Franklin et al. 2010). Although changes in salinity are minimal in the ocean, compatible solutes should be synthesized according to the increase in cell volume or cell number. One of the 14C-LMC spots (Fig. 5b) is expected to be DMSP, which is known to be a compatible solute of E. huxleyi (Franklin et al. 2010).

Acid Polysaccharides Are Major Products Associated with Coccoliths in E. huxleyi

14C incorporation into APext was 13–18 % of total 14C-fixed, which is comparable with that into alkenones (Fig. 3). APext was also decreased under dark conditions (Fig. 5). However, APext is unlikely to be a storage polysaccharide since it is embedded in or covering the coccoliths on the cell surface and so is a structural component rather than a storage compound (Van Emburg et al. 1986). A proportion of APext is released into the medium, where it is degraded by bacterial activity (Van Oostende et al. 2013). Since the E. huxleyi strain used in this study (NIES837) is not from a completely axenic culture, it is possible that the decrease in 14C-APext under dark conditions may be due to the release of AP into the medium and subsequent degradation by bacteria.

In conclusion, we observed high 14C-flux into lipids including alkenones and LMCs, while 14C-flux into β-glucan was low in E. huxleyi. 14C-flux into alkenones was constant in both LP and SP cells, suggesting that alkenone biosynthesis was not regulated by nutrients. Coccolithophores and other secondary endosymbiotic algae, such as diatoms, are proposed to have distinct enzyme sets and regulatory mechanisms for central carbon metabolism (Hockin et al. 2012). Studies on the unique carbon metabolism of secondary endosymbiotic algae will provide new insight onto the diversity and evolution of photosynthetic carbon metabolism in eukaryotes. According to biogeochemical evidence, the coccolithophore E. huxleyi may be a source of petroleum since long-chain hydrocarbons are present in crude oil. The high concentration of alkenones in this organism supports such biogeochemical evidence as alkenones are known to have high potential for crude oil production in comparison with other microalgae (Yamane et al. 2013).

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PPTX 224 kb)

(PPTX 124 kb)

(PPTX 94 kb)

(PPTX 52 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Center for Research in Isotopes and Environmental Dynamics, University of Tsukuba for their generous help with the radioisotope experiments. We also thank Mr. Y. Watanabe (Univ. of Tsukuba) for technical assistance with the GC-FID analysis. This work was supported by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) [CREST/JST] to YS (FY2010–2015).

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest are declared.

References

- Allen AE, Dupont CL, Oborník M, Horák A, Nunes-Nesi A, McCrow JP, Zheng H, Johnson DA, Hu H, Fernie AR, Bowler C. Evolution and metabolic significance of the urea cycle in photosynthetic diatoms. Nature. 2011;473:203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal K, McCrady J, Hansen A, Bhalerao K. Thin layer chromatography and image analysis to detect glycerol in biodiesel. Fuel. 2008;87:3369–3372. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2008.04.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MV, Pond D. Lipid composition during growth of motile and coccolith forms of Emiliania huxleyi. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:465–471. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00663-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conte HM, Thompson A, Lesley D, Harris RP. Genetic and physiological influences on the alkenone/alkenoate versus growth temperature relationship in Emiliania huxleyi and Gephyrocapsa oceanica. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1998;62:51–68. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(97)00327-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danbara A, Shiraiwa Y. The requirement of selenium for the growth of marine coccolithophorids, Emiliania huxleyi, Gephyrocapsa oceanica and Helladosphaera sp. (Prymnesiophyceae) Plant Cell Physiol. 1999;40:762–766. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eltgroth ML, Watwood RL, Wolfe GV. Production and cellular localization of neutral long-chain lipids in the haptophyte algae Isochrysis galbana and Emiliania huxleyi. J Phycol. 2005;41:1000–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein BL, D’Hondt S, Hargraves PE. The possible metabolic role of C37 alkenones in Emiliania huxleyi. Org Geochem. 2001;32:867–875. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(01)00026-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández E, Marañón E, Balch WM. Intracellular carbon partitioning in the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi. J Mar Syst. 1996;9:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0924-7963(96)00016-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtinger-Schepman AMJ, Kamerling JP, Versluis C, Vliegenthart JFG. Structural studies of the methylated, acidic polysaccharide associated with coccoliths of Emiliania huxleyi (lohmann) Kamptner. Carbohydr Res. 1981;93:105–123. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)80756-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin DJ, Steinke M, Young J, Probert I, Malin G. Dimethylsulphoniopropionate (DMSP), DMSP-lyase activity (DLA) and dimethylsulphide (DMS) in 10 species of coccolithophore. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2010;410:13–23. doi: 10.3354/meps08596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Handa N. Carbohydrate metabolism in the marine diatom Skeletonema costatum. Mar Biol. 1969;4:208–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00393894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N, Sato M, Oguri K, Hagino K, Okazaki Y, Katsuki K, Tsuji Y, Shin K-H, Tadai O, Saitoh S, Narita H, Konno S, Jordan RW, Shiraiwa Y, Grebmeier J. Enhancement of coccolithophorid blooms in the Bering Sea by recent environmental changes. Global Biogeochem Cy. 2012;26:GB2036. doi: 10.1029/2011GB004177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa Y, Fujiwara S, Suzuki M, Akiyama T, Sakamoto M, Kobayashi S, Tsuzuki M. Structural and physiological studies on the storage beta-polyglucan of haptophyte Pleurochrysis haptonemofera. Planta. 2008;227:589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockin NL, Mock T, Mulholland F, Kopriva S, Malin G. The response of diatom central carbon metabolism to nitrogen starvation is different from that of green algae and higher plants. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:299–312. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.184333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto K, Shiraiwa Y. Salt-regulated mannitol metabolism in algae. Mar Biotechnol. 2005;7:407–415. doi: 10.1007/s10126-005-0029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayano K, Shiraiwa Y. Physiological regulation of coccolith polysaccharide production by phosphate availability in the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:1522–1531. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayano K, Saruwatari K, Kogure T, Shiraiwa Y. Effect of coccolith polysaccharides isolated from the coccolithophorid, Emiliania huxleyi, on calcite crystal formation in in vitro CaCO3 Crystallization. Mar Biotechnol. 2011;13:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9272-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyachi S, Miyachi S, Kamiya A. Wavelength effects on photosynthetic carbon metabolism in Chlorella. Plant Cell Physiol. 1978;19:277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Myklestad SM. Production, chemical structure, metabolism, and biological function of the (1 → 3)-linked, β-d-glucans in diatoms. Biol Oceanogr. 1989;6:313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Miyachi S. Effect of temperature and CO2 concentration on photosynthetic CO2 fixation by Chlorella. Plant Cell Physiol. 1982;21:765–774. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Sawada K, Araie H, Suzuki I, Shiraiwa Y. Long chain alkenes, alkenones and alkenoates produced by the haptophyte alga Chrysotila lamellosa CCMP1307 isolated from a salt marsh. Org Geochem. 2014;66:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2013.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obata T, Schoenefeld S, Krahnert I, Bergmann S, Scheffel A, Fernie AR. Gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry (GC-MS) based metabolite profiling reveals mannitol as a major storage carbohydrate in the coccolithophorid alga Emiliania huxleyi. Metabolites. 2013;3:168–184. doi: 10.3390/metabo3010168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M, Sawada K, Kubota M, Shiraiwa Y. Change of the unsaturation degree of alkenone and alkenoate during acclimation to salinity change in Emiliania huxleyi and Gephyrocapsa oceanica with reference to palaeosalinity indicator. Res Org Geochem. 2009;25:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Sun M-Y. Variations of alkenone based paleotemperature index (U37K′) during Emiliania huxleyi cell growth, respiration (auto-metabolism) and microbial degradation. Org Geochem. 2011;42:678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2011.03.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prahl FG, Sparrow MA, Wolfe GV (2003) Physiological impacts on alkenone paleothermometry. Paleoceanography 18:2002PA000803

- Read BA, Kegel J, Klute MJ, Kuo A, Lefebvre SC, Maumus F, Mayer C, Miller J, Monier A, Salamov A, Young J, Aguilar M, Claverie JM, Frickenhaus S, Gonzalez K, Herman EK, Lin YC, Napier J, Ogata H, Sarno AF, Shmutz J, Schroeder D, de Vargas C, Verret F, von Dassow P, Valentin K, Van de Peer Y, Wheeler G, Emiliania huxleyi Annotation Consortium. Dacks JB, Delwiche CF, Dyhrman ST, Glöckner G, John U, Richards T, Worden AZ, Zhang X, Grigoriev IV. Pangenome of the phytoplankton Emiliania underpins its global distribution. Nature. 2013;499:209–213. doi: 10.1038/nature12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts TR. On the chemical composition of some unicellular algae. Phytochemistry. 1966;5:67–76. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)85082-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rontani J-F, Cuny P, Grossi V, Beker B. Stability of long-chain alkenones in senescing cells of Emiliania huxleyi: effect of photochemical and aerobic microbial degradation on the alkenone unsaturation ratio (U37k′) Org Geochem. 1997;26:503–509. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(97)00023-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rontani J-F, Prahl FG, Volkman JK. Re-examination of the double bond positions in alkenones and derivatives: biosynthetic implications. J Phycol. 2006;42:800–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00251.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada K, Shiraiwa Y. Alkenone and alkenoic acid compositions of the membrane fractions of Emiliania huxleyi. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1299–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada K, Handa N, Shiraiwa Y, Danbara A, Montani S. Long-chain alkenones and alkyl alkenoates in the coastal and pelagic sediments of the northwest North Pacific, with special reference to the reconstruction of Emiliania huxleyi and Gephyrocapsa oceanica ratios. Org Geochem. 1996;24:751–764. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(96)00087-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Ikawa T. Effects of oxygen on photosynthetic 14CO2 fixation in Chroomonas sp. (Cryptopyta) III. Effect of oxygen on photosynthetic carbon metabolism. Plant Cell Physiol. 1985;26:1003–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji Y, Suzuki I, Shiraiwa Y. Photosynthetic carbon assimilation in the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi (Haptophyta): Evidence for the predominant operation of the C3 cycle and the contribution of β-carboxylases to the active anaplerotic reaction. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:318–329. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji Y, Suzuki I, Shiraiwa Y. Enzymological evidence for the function of a plastid-located pyruvate carboxylase in the Haptophyte alga Emiliania huxleyi: a novel pathway for the production of C4 compounds. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:1043–1052. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrrell T, Merico A. In: Coccolithophores. From molecular processes to global impact. Thierstein HR, Young JR, editors. Berlin: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Van Emburg PR, de Jong EW, Daems WT. Immunochemical localization of a polysaccharide from biomineral structures (coccoliths) of Emiliania huxleyi. J Ultrastruct Mol Struct Res. 1986;94:246–259. doi: 10.1016/0889-1605(86)90071-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oostende N, Moerdijk-Poortvliet TC, Boschker HT, Vyverman W, Sabbe K. Release of dissolved carbohydrates by Emiliania huxleyi and formation of transparent exopolymer particles depend on algal life cycle and bacterial activity. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:1514–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vårum KM, Kvam BJ, Myklestad S. Structure of a food-reserve β-d-glucan produced by the haptophyte alga Emiliania huxleyi (Lohmann) Hay and Mohler. Carbohydr Res. 1986;152:243–248. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(00)90304-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman JK, Everitt DA, Allen DI. Some analyses of lipid classes in marine organisms, sediments and seawater using thin-layer chromatography–flame ionisation detection. J Chromatogr A. 1986;356:147–162. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(00)91474-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Ikawa T, Nisizawa K. Incorporation of radioactive carbon from H14CO3− into sugar constituents by a brown alga, Eisenia bicyclis, during photosynthesis and its fate in the dark. Plant Cell Physiol. 1966;7:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Ikawa T, Nishizawa K. Pathway of mannitol formation during photosynthesis in brown algae. Plant Cell Physiol. 1969;10:425–440. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane K, Matsuyama S, Igarashi K, Utsumi M, Shiraiwa Y, Kuwabara T. Anaerobic coculture of microalgae with Thermosipho globiformans and M. ethanocaldococcus jannaschii at 68 °C enhances generation of n-alkane-rich biofuels after pyrolysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:924–930. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01685-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Tanabe Y, Yonezawa N, Watanabe MM. Energy innovation potential of oleaginous microalgae. Biofuels. 2012;3:761–781. doi: 10.4155/bfs.12.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PPTX 224 kb)

(PPTX 124 kb)

(PPTX 94 kb)

(PPTX 52 kb)