Abstract

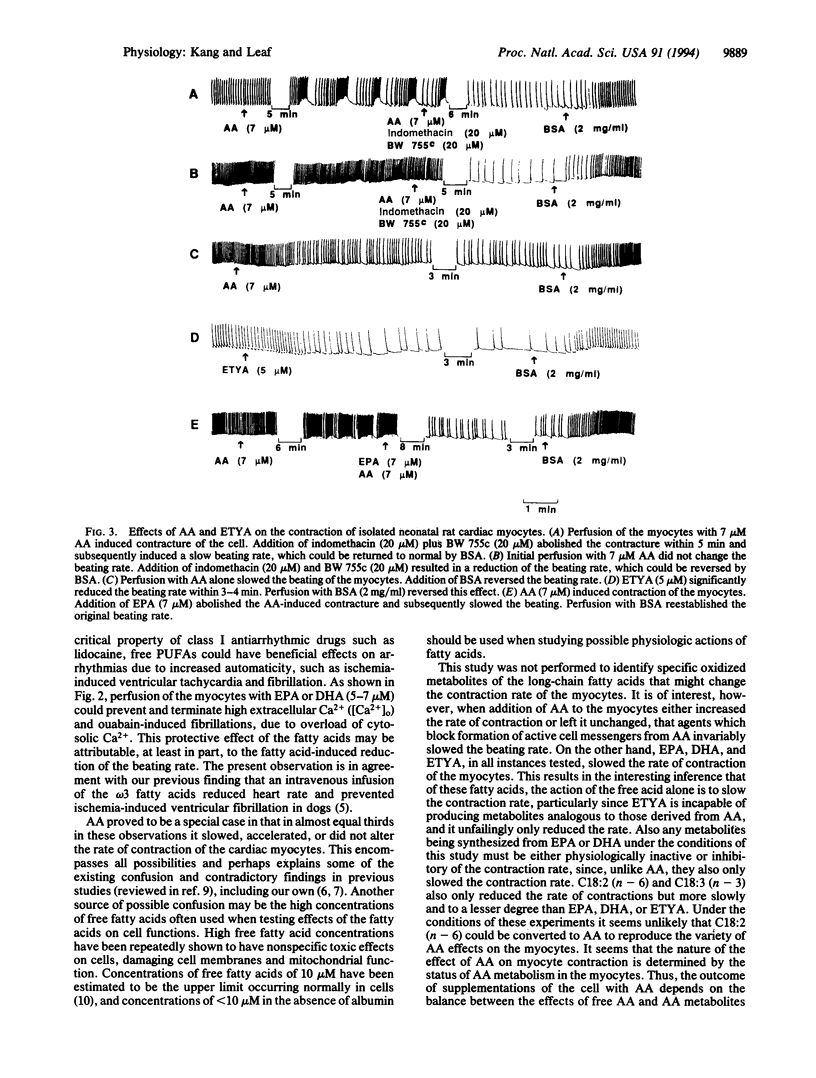

Because of the ability of certain long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to prevent lethal cardiac arrhythmias, we have examined the effects of various long-chain fatty acids on the contraction of spontaneously beating, isolated, neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. The omega 3 PUFA from fish oils, eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA; C20:5 (n-3)] and docosahexaenoic acid [DHA; C22:6 (n-3)], at 2-10 microM profoundly reduced the contraction rate of the cells without a significant change in the amplitude of the contractions. The fatty acid-induced reduction in the beating rate could be readily reversed by cell perfusion with fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin. Addition of either oxygenase inhibitors or antioxidants did not alter the effect of the fatty acids. Arachidonic acid [AA; C20:4 (n-6)] produced two different effects on the beating rate, an increase or a decrease, or it produced no change. In the case of the increased or unchanged beating rate in the presence of AA, addition of AA oxygenase inhibitors subsequently reduced the contraction rate. The nonmetabolizable AA analog eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA) always reduced the beating rate, as did EPA or DHA. Two other PUFAs, linoleic acid [C18:2 (n-6)] and linolenic acid [C18:3 (n-3)] also exhibited similar but less potent effects compared with EPA or ETYA. In contrast, neither the monounsaturated fatty acid oleic acid [C18:1 (n-9)] nor the saturated fatty acids stearic acid (C18:0), myristic acid (C14:0), and lauric acid (C12:0) affected the contraction rate. The inhibitory effect of these PUFAs on the contraction rate was similar to that produced by the class I antiarrhythmic drug lidocaine. The fatty acids that are able to reduce the beating rate, particularly EPA and DHA, could effectively prevent and terminate lethal tachyarrhythmias (contracture/fibrillation) induced by high extracellular calcium concentrations or ouabain. These results suggest that free PUFAs can suppress the automaticity of cardiac contraction and thereby exert their antiarrhythmic effects.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Billman G. E., Hallaq H., Leaf A. Prevention of ischemia-induced ventricular fibrillation by omega 3 fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 May 10;91(10):4427–4430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallaq H., Sellmayer A., Smith T. W., Leaf A. Protective effect of eicosapentaenoic acid on ouabain toxicity in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Oct;87(20):7834–7838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallaq H., Smith T. W., Leaf A. Modulation of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels in heart cells by fish oil fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Mar 1;89(5):1760–1764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honoré E., Barhanin J., Attali B., Lesage F., Lazdunski M. External blockade of the major cardiac delayed-rectifier K+ channel (Kv1.5) by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Mar 1;91(5):1937–1941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf A. Health claims: omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. Nutr Rev. 1992 May;50(5):150–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1992.tb01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan P. L., Abeywardena M. Y., Charnock J. S. Dietary fish oil prevents ventricular fibrillation following coronary artery occlusion and reperfusion. Am Heart J. 1988 Sep;116(3):709–717. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan P. L., Bridle T. M., Abeywardena M. Y., Charnock J. S. Dietary lipid modulation of ventricular fibrillation threshold in the marmoset monkey. Am Heart J. 1992 Jun;123(6):1555–1561. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90809-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe S., Bogdanov K., Hallaq H., Spurgeon H., Leaf A., Lakatta E. Omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid modulates dihydropyridine effects on L-type Ca2+ channels, cytosolic Ca2+, and contraction in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Sep 13;91(19):8832–8836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vusse G. J., Glatz J. F., Stam H. C., Reneman R. S. Fatty acid homeostasis in the normoxic and ischemic heart. Physiol Rev. 1992 Oct;72(4):881–940. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]