Abstract

Significance: The contribution of epigenetic alterations to cancer development and progression is becoming increasingly clear, prompting the development of epigenetic therapies. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDIs) represent one of the first classes of such therapy. Two HDIs, Vorinostat and Romidepsin, are broad-spectrum inhibitors that target multiple histone deacetylases (HDACs) and are FDA approved for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, the mechanism of action and the basis for the cancer-selective effects of these inhibitors are still unclear. Recent Advances: While the anti-tumor effects of HDIs have traditionally been attributed to their ability to modify gene expression after the accumulation of histone acetylation, recent studies have identified the effects of HDACs on DNA replication, DNA repair, and genome stability. In addition, the HDIs available in the clinic target multiple HDACs, making it difficult to assign either their anti-tumor effects or their associated toxicities to the inhibition of a single protein. However, recent studies in mouse models provide insights into the tissue-specific functions of individual HDACs and their involvement in mediating the effects of HDI therapy. Critical Issues: Here, we describe how altered replication contributes to the efficacy of HDAC-targeted therapies as well as discuss what knowledge mouse models have provided to our understanding of the specific functions of class I HDACs, their potential involvement in tumorigenesis, and how their disruption may contribute to toxicities associated with HDI treatment. Future Directions: Impairment of DNA replication by HDIs has important therapeutic implications. Future studies should assess how best to exploit these findings for therapeutic gain. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 51–65.

Introduction

One key consequence of the cellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is DNA damage. There are multiple origins of this damage, especially in cancer cells, where ROS can affect the levels or activity of DNA replication factors, the levels of deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) due to changes in metabolism, and cause the formation of DNA adducts. These effects are mutagenic and they also cause DNA replication stress that results in DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and genomic instability (17). There are many links between histone deacetylases (HDACs) and the production of ROS and/or the downstream repair of these lesions. For example, HDAC inhibition may induce the accumulation of ROS (98, 99, 102, 122, 130). Downstream of ROS, HDACs play a key role in the ability of cells to repair these DNA lesions either by unfolding compacted chromatin, modification of lysine acetylation on DNA repair factors, the regulation of DNA replication, or by the regulation of gene expression. The role of HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC3 in these processes and what we have learned by studying deletions of these genes in mice will be the focus of this review.

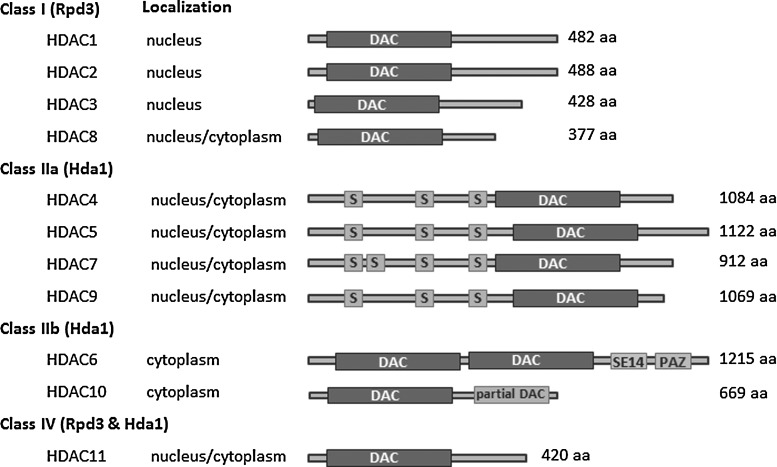

HDACs are divided into four classes based on their homology to yeast proteins (Fig. 1). Class I HDACs (HDAC1, 2, 3, and 8) are homologous to the yeast protein Rpd3, are predominantly nuclear, and are typically found in association with transcriptional repressor complexes. Class II HDACs (HDAC4, 5, 6, 7, 9, and 10) are homologous to the yeast Hda1 protein and are both nuclear and cytoplasmic. HDAC6 contains two catalytic domains, the second of which is specific for tubulin rather than histones, providing one specific example of how HDACs often have nonhistone as well as histone substrates. The third class of HDACs contains the sirtuins, which are homologous to the yeast Sir2. The lone member of class IV is HDAC11, which shares homology with both class I and II HDACs.

FIG. 1.

Classification of the nonsirtuin HDAC families. Eleven human HDACs are pictured (class III HDACs, the sirtuins, are not included). Class I HDACs are largely nuclear and are related to the yeast protein Rpd3 within the conserved, deacetylase domain (DAC). Class II HDACs are related to the yeast Hda1 protein. Class IIa proteins have a number of N-terminal serine phosphorylation sites (S), which facilitate cytoplasmic shuttling. Class IIb HDACs contain tandem deacetylase domains (only a partial domain in the case of HDAC10). In addition, HDAC6 contains an SE14 repeat domain, important for its cytoplasmic retention, and a ubiquitin-binding zinc finger domain (PAZ domain). HDAC11 is the sole member of the class IV HDACs and shows homology with both class I and class II HDACs. HDAC, histone deacetylase.

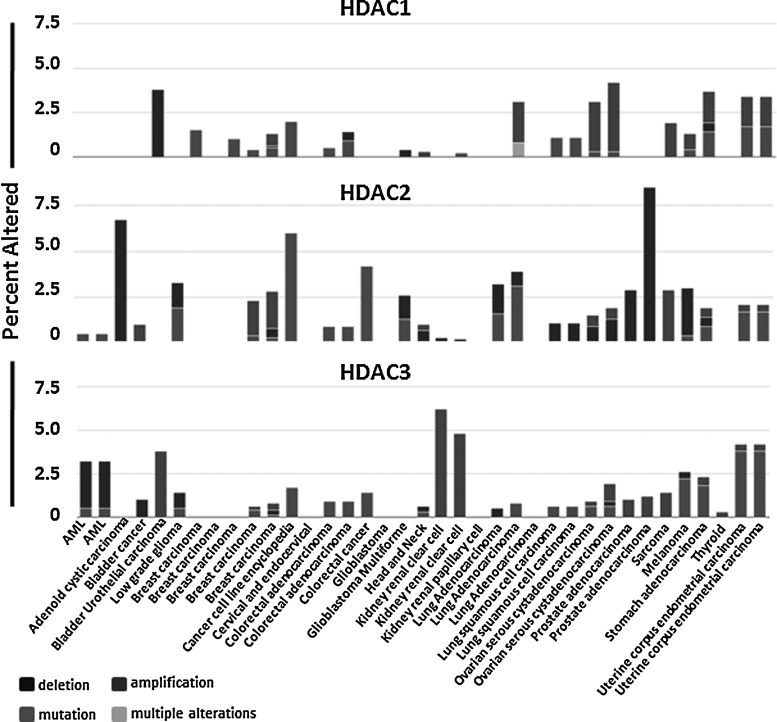

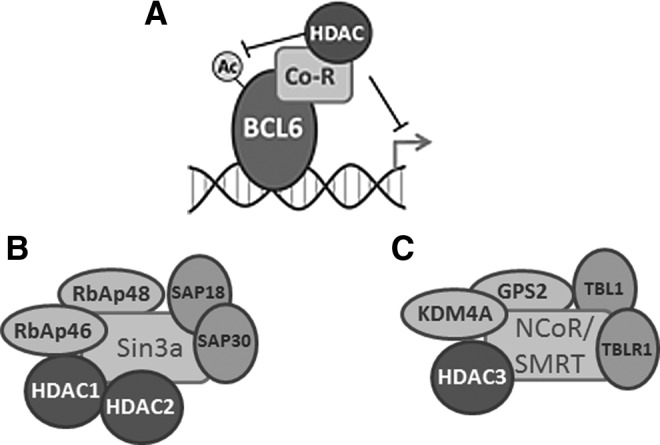

The enzymatic activity of HDACs 1, 2, and 3 requires their association with multi-subunit repression complexes (Fig. 2). For instance, the catalytic activity of HDAC3 requires its association with the nuclear hormone co-repressor 1 (NCOR1), or its homolog, silencing mediator of retinoid, or thyroid-hormone receptors (SMRT or NCOR2). Recently, the structure of the complex between HDAC3 and the SMRT “deacetylase activating domain” (DAD) was solved and found to contain an essential inositol tetraphosphate molecule (Ins(1,4,5,6)P4), which mediates the interaction of these two proteins (127) (Fig. 3). A subsequent study demonstrated a similar requirement of Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 in HDAC1-containing repression complexes and further concluded that the presence of Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 dramatically enhanced HDAC activity (75). Given the apparent requirement of Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 for class I HDAC function, targeting of the Ins(1,4,5,6)P4–HDAC/co-repressor interaction could provide a novel and selective node for therapeutic intervention, enabling the more specific targeting of class I HDACs.

FIG. 2.

Recruitment of HDAC-containing repressor complexes by the BCL6 proto-oncogene. Gene rearrangements involving BCL6 are commonly associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BCL6 represses target gene expression (A) through the recruitment of both HDAC1- and HDAC2-containing Sin3a complexes (B), as well as through the recruitment of HDAC3-containing NCoR/SMRT complexes (C). In addition, BCL6 is itself regulated by acetylation. Acetylation of BCL6 inhibits its ability to bind DNA, and the deacetylation of BCL6 has been ascribed to both Sirtuin and HDAC activities (10). NCoR, nuclear hormone co-repressor; SMRT, silencing mediator of retinoid or thyroid-hormone receptors.

FIG. 3.

The HDAC co-repressor association is mediated by Ins(1,4,5,6)P4. Crystallography studies have solved the structure of the interaction between the SMRT DAD (upper left) and human HDAC3. These studies have revealed the requirement of the inositol tetraphosphate molecule [Ins(1,4,5,6)P4, arrow] for both the stabilization and activation of the HDAC-corepressor complex (127). DAD, deacetylase activating domain.

Histone Acetylation and Its Regulation

Chromatin is a dynamic structure that enables the packaging of more than 5 billion base pairs of DNA into the cell nucleus, while also allowing context-specific accessibility to factors controlling cellular processes such as DNA replication, DNA damage repair, and gene transcription. The basic unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which is composed of 147 bp of DNA wrapped around a core histone octamer (two copies each of H3, H4, H2A, and H2B) (69). Histones undergo a number of post-translational modifications, including acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitylation, and sumoylation, which occur predominantly on the N-terminal histone tails (29). These modifications regulate the organization and relative compaction of the chromatin by altering inter- and intra-nucleosomal contacts and by serving as docking sites for other chromatin-modifying proteins (22).

In particular, lysine acetylation is associated with chromatin relaxation through disruption of nucleosomal contacts (69). In addition, acetylated lysine residues within the conserved amino-terminal histone tails serve as binding sites for bromodomain-containing proteins, which further regulate chromatin structure and DNA-templated processes (32). Thus, the appropriate levels of histone acetylation should be tightly regulated by the opposing activities of histone acetyltransferases and HDACs in order to appropriately regulate the many cellular processes that require access to DNA. For instance, histone acetylation opens chromatin, making DNA accessible for activation of gene expression or DNA replication, while deacetylation of those same histones renders DNA more compact, facilitating gene silencing (69). In many cases, these same lysines are subject to other forms of modification, including methylation, which may be associated with gene silencing (e.g., H3K9me3). Therefore, in instances such as these, lysines should first be deacetylated before other repressive marks may be added, thus creating a multilayered regulatory system (4, 38, 89). Remarkably, HDACs 1–3 deacetylate many of the same residues on the histone tails, including H3K4, H3K9, H3K14, H3K27, H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, and H4K16 (13, 131). The lone exception appears to be H3K56ac, which is affected by inactivation of Hdac1 and Hdac2, but not Hdac3 (76, 128). The acetylation of specific histone lysines may have unique functions. For instance, residues such as H3K9ac are most often associated with active transcription; whereas H4K5 and H4K12 are associated with histone deposition during DNA replication.

HDACs Regulate DNA Replication

The idea that HDACs play a role in the regulation of replication and S-phase progression is not a new one; however, in many ways, it has been overshadowed by studies examining the involvement of HDACs in the regulation of gene expression. Yeast cells lacking the ortholog of mammalian class I HDACs, Rpd3, exhibited a delay in S-phase progression, which is consistent with the idea that class I HDACs play a prominent role in S-phase regulation (125). Furthermore, studies in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) demonstrated that disrupting Hdac3 function causes the accumulation of S-phase-dependent DNA damage (11). Similarly, acute treatment of cancer cell lines with suberoyl anilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) induced DNA damage, which co-localized with sites of active DNA replication (25), further suggesting that HDAC inhibition may promote DNA damage and subsequent cell killing by first inducing replication stress. Mechanistically, it is possible that HDACs act at the replication fork or regulate global changes in chromatin structure to affect DNA polymerase functions to cause DNA damage (Fig. 4).

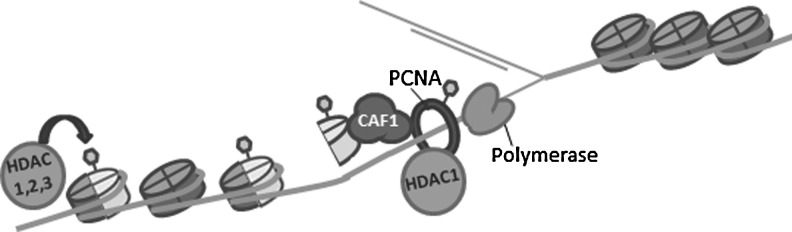

FIG. 4.

Changes in chromatin structure and histone acetylation are linked to DNA replication. HDACs 1, 2, and 3 localize to replication forks, and the disruption of HDAC function slows replication fork progression. This could be through direct effects on the replication machinery, as replication factors such as PCNA are regulated through acetylation. Alternatively, newly synthesized histones are acetylated on H4K5K12 before deposition onto nascent DNA. Histone chaperones, such as CAF-1, are important for histone deposition and associate with HDACs. Furthermore, HDACs 1, 2, and 3 have been implicated in the removal of histone deposition marks (H4K5 and H4K12), which is critical for chromatin maturation and the disruption of which can contribute to replication stress. CAF-1, chromatin assembly factor 1; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen.

HDACs affect DNA replication fork functions

While it is obvious that the inhibition of HDAC function has profound effects on S-phase progression and DNA replication, how HDACs function in the regulation of these processes is less obvious. During the S phase, dynamic changes in the chromatin landscape occur both as chromatin is disrupted to make way for the replication of DNA polymerase and as chromatin structure is re-established behind the moving fork. In addition, nucleosome positioning and histone modifications may play a role in the selection, licensing, and firing of replication origins (4, 74, 125). For instance, the origin recognition complex (ORC) tends to occupy nucleosome-free regions of chromatin, while histone H4 acetylation by the acetyltransferase HBO1 facilitates minichromosome maintenance loading/pre-replication complex assembly at origins (78). Additional studies in yeast and flies have revealed that the HDAC, Rpd3, localizes to replication origins (61), where it deacetylates histones to impair origin firing (2). Consistent with this idea, loss of Rpd3 is associated with redistribution of the ORC2 (2) and the early activation of late firing origins (8, 125).

The impact of HDAC function on higher-order spatial reorganization of chromatin may also be important for DNA replication (26). For example, cohesin complexes are regulated by acetylation (109), are enriched at origins, and may facilitate the organization of origins into looping replication domains, which contain multiple origins firing almost simultaneously (41). Deregulation of chromatin structure throughout the process of DNA replication is associated with anomalies such as uncontrolled origin firing and replication fork collapse, each of which can promote DNA damage and genomic instability, thereby having catastrophic and potentially oncogenic consequences for the cell (4). Therefore, the ability to modulate chromatin structure is crucial for successful DNA replication, and it is possible that HDAC-targeted therapies impact replication through the deregulation of these chromatin structures.

While such general changes in chromatin architecture may play a role in the generation of replication stress after HDAC inhibition, disruption of HDAC functions may also directly affect replication, as very short treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDIs) still generated robust reductions in the rates of replication fork progression (112, 128). In cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) cell lines treated with both broad-spectrum and HDAC3-selective inhibitors, the effects of HDI treatment on replication fork velocity were observed before the accumulation of global increases in histone acetylation (128). These results suggest that HDACs function to regulate replication (or local chromatin structure) on or around the replication fork. Since HDACs also have a multitude of nonhistone substrates, one possibility is that HDACs act directly on components of the replication machinery. In fact, replication factors themselves are subject to regulatory post-translational modifications, including acetylation. For instance, the ability of the replication processivity factor, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) to associate with DNA polymerase is regulated by acetylation (86). Moreover, PCNA co-purified with HDAC1 (77, 86), suggesting that this enzyme may regulate PCNA acetylation status to modulate its function.

Some of the most compelling data implicating HDAC function in DNA replication come from a powerful technique called isolation of proteins on nascent DNA (iPOND). iPOND enables the isolation of newly synthesized DNA (i.e., the replication fork) and the associated proteins (107). Consistent with the idea that HDACs function at or around the replication fork, this technique detected HDAC1, 2 and 3 at sites of active DNA replication. Interestingly, while HDAC1 appeared to move with the replication fork, HDAC2 and HDAC3 more stably associated with nascent chromatin (108). This suggests that HDAC1 moves with the fork, while the other HDACs are associated with chromatin before and after the fork. While the disparate kinetics of nascent chromatin association implies that these HDACs may have different functions at the replication fork, a more detailed understanding of their activities there awaits further study.

HDACs function in histone deposition

Since DNA is replicated, chromatin structure should be re-established behind the replication fork. This requires the incorporation of both old and new histones into the newly generated chromatin fiber in a process known as histone deposition. Importantly, the disruption of histone deposition can have dramatic effects on the stability of the departing replication fork. In yeast, impaired nucleosome deposition due to depletion of H4 resulted in replication fork collapse, DNA DSBs, and even large chromosomal rearrangements (24). The deposition of newly synthesized histones onto nascent DNA is mediated by histone chaperone proteins such as chromatin assembly factor 1 (CAF-1). Disruption of CAF-1 function in U2OS cells resulted in the accumulation of DNA damage and S-phase cell cycle arrest, suggesting that histone chaperone function and proper histone deposition is critical for chromatin maturation and maintenance of genomic stability (133). Consistent with a role in histone deposition, HDACs 1, 2, and 3 associate with histone chaperones, including CAF-1 (3, 87, 121); so, histone deacetylation likely occurs soon after histone deposition.

New histones are marked by acetylation (e.g., H4K5ac and H4K12ac) for deposition onto newly synthesized DNA. Treatment of cells with Depsipeptide (FK228) prevented the removal of H4K5 and H4K12 acetylation marks from nascent chromatin (108), suggesting that HDACs are required for deacetylation of newly deposited histones. Genetic studies confirmed these results, as deletion of Hdacs1/2 resulted in the accumulation of histone deposition marks in MEF models (131). In addition, Hdac3−/− MEFs displayed an accumulation of histone deposition marks as well as DNA damage, which is consistent with the idea that defects in chromatin maturation behind the replication fork can affect genome stability (11). Therefore, HDAC1, 2, and 3 remove acetylation marks after the deposition of newly synthesized histones onto nascent DNA. Furthermore, the disruption of this chromatin maturation process on HDAC inhibition may contribute to the accumulation of DNA damage observed after HDI treatment.

HDAC function is required for maintenance of heterochromatin

Failure to remove histone deposition marks in a timely fashion has been associated with the loss of silencing at particular loci as well as disruption of pericentric heterochromatin (31, 116). HDACs 1, 2, and 3 have been implicated in the maintenance of heterochromatin domains (13, 46, 106, 136), and deletion of Hdac3 in the murine liver caused increases in H3K9ac, a reduction in H3K9me3 (which is bound by heterochromatin proteins), and widespread losses of heterochromatin (13). These disruptions of histone acetylation and heterochromatin structure in the absence of HDACs or after treatment with HDIs have been linked to aberrant mitoses, which can be associated with mitotic catastrophe and cell killing (54, 72, 115, 116). Likewise, treatment of Drosophila melanogaster embryos with an HDI in the absence of de novo transcription generated aberrant mitoses, suggesting that mitotic defects observed on HDAC inhibition occurred independently of HDI-mediated changes in gene expression (126). These effects could be due to loss of heterochromatin or loss of checkpoint control, resulting in a loss of Aurora B kinase activity (11, 67). In all, these studies suggest that aberrations in replication, histone deposition, and chromatin maturation behind the replication fork after HDAC inhibition may be associated with replication fork stalling, accumulation of DNA damage, disruption of heterochromatin, and genomic instability.

Replication Defects Likely Contribute to Cancer-Selective Cell Killing by HDIs

The idea that HDIs exert their anti-cancer effects by targeting replication is a tempting hypothesis, as the therapeutic window of traditional chemotherapies has been attributed to their ability to cause DNA damage after induction of replication stress. Consistent with this idea, the treatment of CTCL cell lines with Depsipeptide and the treatment of breast cancer cells with SAHA demonstrated an effect of HDAC inhibition on replication rates (25, 128). Furthermore, these reductions in replication rates were associated with the induction of DNA damage, and in the case of CTCL cells, an accumulation of cells in the S phase (128). Therefore, it is likely that the ability to hinder replication is an important mechanism contributing to the efficacy of HDAC inhibition.

In particular, specific targeting of HDAC3 through either a selective inhibitor or siRNAs impaired replication in two different cancer models (25, 128). These data are consistent with Hdac3 gene deletion models, which demonstrated that apoptosis in the absence of Hdac3 was associated with impaired S-phase progression and the accumulation of DNA DSBs rather than dramatic changes in gene transcription (11). Given that Hdac3 is targeted by HDIs currently being used in cancer treatment (i.e., SAHA, Depsipeptide), it is possible that some of the anti-tumor effects associated with these drugs are related to their ability to target DNA replication on HDAC3 inhibition in tumor cells. Furthermore, deletion of HDAC1 and HDAC2 caused dramatic genomic instability in transformed cells, suggesting replication defects (12, 42). This is consistent with the presence of these HDACs at replication forks and their established role in histone deposition (108).

Studies implicating HDACs in replication control further hint at a mechanism for the cancer-selective effects of HDAC inhibition. Targeting of replication and S phase would spare the largely noncycling normal cells, while causing the accumulation of DNA damage and, ultimately, cell death in the rapidly dividing cancer cell populations. In addition, while primary cells have intact cell cycle checkpoints, which may enable them to cope with the stress imposed by HDIs, the abrogation of these checkpoints that characterizes cancer cells may further sensitize them to the effects of HDAC inhibition. For instance, while SAHA treatment resulted in the accumulation of DNA damage in both normal and transformed cells, normal cells were able to efficiently repair that damage, while cancer cell lines struggled to achieve efficient repair, ultimately resulting in cancer cell-specific cell death (65). Likewise, HDI-induced G1 arrest after p21 induction (40, 49, 97) might protect normal cells from accumulation of S-phase-dependent DNA damage, while the disruption of either the G1/S or intra-S-phase checkpoints frequently observed in cancer cells could result in either the failure to maximally induce p21 expression or the failure to arrest in its presence. This idea is supported by multiple reports suggesting that p21 induction by HDIs hampers their ability to induce apoptosis (16, 93, 100). Finally, inactivation of Hdac3 in immortal cells caused a loss of Aurora B kinase activity that was not observed in normal cells (11, 67) These effects might explain why cancer cells often exhibit a G2/M arrest after HDI treatment (54, 91, 101, 111).

In all, these studies suggest that altered cell cycle checkpoints found in cancer cells impair their ability to respond to HDI-induced genomic instability, and may account for the cancer-specific toxicity observed with these drugs. Furthermore, these studies suggest that replication stress and the resulting genomic instability likely contribute to the efficacy of HDAC-targeted therapies. However, other cellular processes, such DNA repair, are also impacted by HDIs and may cooperate with HDI-induced replication stress to promote cell killing.

Loss of HDAC Function Impairs DNA Repair

Altered DNA repair has also been observed after HDI treatment, and it may be expected to cooperate with HDI-induced replication stress to further promote genomic instability and cancer cell killing. Furthermore, multiple lines of evidence suggest that HDACs directly participate in the repair process. In particular, HDAC1 and HDAC2 rapidly localize to DSBs, where they deacetylate H3K56 and H4K16 (27, 35, 76). This initial deacetylation has been proposed to facilitate DNA repair by maintaining the broken DNA ends in close proximity, as well as by inhibiting transcription in the area of the DSB (30). In addition, H4K16 deacetylation by HDAC1/2 favored repair by nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) compared with homologous recombination repair (HRR) by promoting 53BP1 binding (35, 47, 117). Consistent with a role in NHEJ, knockdown of HDAC1 and HDAC2 resulted in impaired DSB repair by NHEJ, increased γH2AX, and hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation (IR) (76). Hdac3-deficient cells also exhibited defects in DNA repair. Hdac3-deleted fibroblasts showed increased and persistent γH2AX foci after IR, suggesting a role for Hdac3 in DSB repair (11). However, unlike knockdown of HDAC1 and HDAC2, which seemed to affect NHEJ in particular, knockdown of HDAC3 impaired both HR- and NHEJ-mediated repair (73). In addition, repair defects in Hdac3-deficient cells were characterized by an increase in H3K9/K14ac and a concomitant decrease in H3K9me3. This loss of H3K9me3 may hamper repair by preventing the recruitment of Tip60, which functions as a critical mediator of chromatin remodeling at DSBs, enabling repair factors to access the damaged DNA (113).

The effects on specific types of repair suggest that HDACs also impact repair by regulating the acetylation of key checkpoint and repair proteins. Treatment of cancer cell lines with SAHA or MS275 followed by immunoaffinity purification with anti-acetyl lysine and mass spectrophotometry identified changes in acetylation of a number of DNA damage response (DDR) proteins, including p53, Ku70, FEN1, DNA-PK, and ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) (92). Furthermore, HDAC1 associates with ATM and this interaction was increased on exposure to IR (60), again suggesting that HDACs may alter DNA repair by directly regulating the activity of repair proteins. In addition to direct regulation of repair protein activity, other studies have proposed that HDI treatment impairs DNA repair by downregulating the expression of critical repair factors (98, 120). In all, the disrupted DDR observed on HDAC inhibition likely results from changes in histone acetylation as well as changes in repair factor recruitment, activity, and/or levels. In addition, attenuation of DNA repair after HDI treatment likely cooperates with HDI-induced replication stress to increase DNA damage accumulation and, ultimately, cancer cell death.

HDIs Alter Gene Expression, but Is It Important?

While the preceding sections focused on impaired replication as a potential mechanism of action for HDIs, the disruption of other chromatin-associated processes, including transcription, also likely contribute to the anti-tumor effects associated with the disruption of HDAC function (1, 43, 44, 58). In fact, in some cases, it seems likely that the HDIs exert their effects through altering transcriptional programs. For instance, in the case of acute promyelocytic leukemia containing the PLZF-RARα fusion protein, it appears that combination therapy with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and HDIs is required to restore normal retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-regulated transcriptional programs and, subsequently, normal promyelocyte differentiation and cell death (44). It remains possible, however, that such cases are the exception rather than the rule. For instance, multiple groups reported relatively modest changes in gene expression (5%–22% of genes) after HDI treatment, and while many transcriptional studies have been performed, no common gene expression signature has been identified that would trigger cell death (34, 48, 68, 79, 90, 114, 123).

In most gene expression studies, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 is commonly upregulated and has been associated with an HDI-induced G1 arrest (40, 49, 97). While p21 expression is directly regulated by HDAC1 (40, 97, 137), p21 induction on HDAC inhibition is severely impaired in the absence of the critical DNA damage-sensing kinase, ATM (55). The idea that p21 induction on HDI treatment results entirely from a direct transcriptional effect is based largely on the fact that HDIs induce p21 expression even in the absence of p53 (49, 85, 110), but multiple mechanisms exist for the p53-independent induction of p21 in response to a variety of cellular stresses (6, 23, 103). Such observations support the idea that induction of p21 expression by HDIs, in addition to direct changes in acetylation at the p21 locus, could be related to DNA damage and/or DNA replication stress.

While histone acetylation is associated with active transcription, in most of these gene expression studies, just as many genes were downregulated as were up-regulated, suggesting that much of the altered transcription observed was not a direct result of gene-specific increases in histone acetylation after HDI treatment. Moreover, while HDIs display a good degree of selectivity for cancer cells, the treatment of normal cells with HDIs results in comparable numbers of transcriptional changes though the specific genes altered may be different. However, two observations point toward a defect in replication rather than altered transcription as the mechanism of action for HDI therapies. First, the overexpression of p16INK4a and associated G1-phase cell cycle arrest in leukemia cells prevented SAHA-induced apoptosis without dramatically altering SAHA-induced changes in gene expression profiles (90). Second, serum starvation to arrest cells in G0 also protected cells from HDI-mediated cell death, again supporting the idea that transcriptional changes which would be expected to occur in noncycling or G1-phase cells may not be the primary mechanism of HDI-mediated cell killing (11). These relatively simple cell cycle studies support the hypothesis that HDIs induce cell death by targeting replication, as induction of G1 arrest would prevent HDI-induced replication stress, the accumulation of DNA damage and/or loss of heterochromatin marks, and subsequent apoptosis. Finally, it is notable that in vivo mutagenesis of Hdac3 indicated that the deacetylase activity was not required for regulating transcription, suggesting that HDIs act by other means (109).

Toxicities Associated with Hdac1, Hdac2, and Hdac3 Inhibition

Just as multiple cellular process are targeted by HDIs to promote cancer cell killing, multiple HDAC proteins are also targeted by these inhibitors, making it difficult to ascribe the effects of these drugs to the inhibition of a single protein. Simultaneously, while it is obvious that HDIs selectively target cancer cells compared with normal cells (134), their use is not devoid of toxicity, suggesting that normal tissues are also affected by these drugs. In particular, HDI treatment has been associated with neurological, cardiac, and a number of blood-related toxicities (14, 15, 92, 96). Gene-specific and tissue-specific mouse models have begun to shed light onto which HDACs may be responsible for both the efficacy and the toxicities associated with broad-spectrum HDAC inhibition (21, 36, 39, 52, 53, 63, 81, 95, 119, 132) (Table 1). In addition, while clinical trials are currently underway to determine the effectiveness of HDIs in the treatment of a number of tumor types, hematologic malignancies remain the only cancers for which these drugs have obtained FDA approval (94). Therefore, it is important to gain an understanding of the function of these proteins within the hematopoietic compartment, which is an ideal model system to study the function of the class I HDACs in stem cell biology and cellular differentiation, as well as to predict the contribution of these proteins to HDI-associated hematological toxicities. Finally, it is likely that HDAC functions in replication control and maintenance of genome stability contributes to the phenotypes observed in mouse deletion models. For instance, replication stress was recently observed in a model of Hdac3 deletion in hematopoietic stem cells (112).

Table 1.

Tissue-Specific Effects of Histone Deacetylase Targeting

| Tissue | Cre-driver | Phenotype | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hdac1 | Germline | N/A | Embryonic lethal E9.5–10.5; proliferative defects | (51, 66) |

| T cells | CD4-Cre | Increased inflammation and proliferation in allergy model | (29) | |

| Hdac2 | Germline | N/A | Perinatal lethality; cardiac defects | (66, 107) |

| Neuronal | Nestin-Cre | Enhanced memory formation | (32) | |

| Brain | GLAST::CreER T2/ZEG | Apoptosis during adult neurogenesis | (44) | |

| Hdac1 and Hdac2 | CNS | GFAP-Cre | Increased proliferation of neural progenitors and differentiation block | (67) |

| Oligodendricytes | Olig1-Cre | Neonatal lethal, required for proper oligodendricyte specification and differentiation | (109) | |

| PNS | DHH-Cre | Schwann cell apoptosis and associated loss of myelination | (16, 43) | |

| Heart | αMHC-cre | Postnatal lethal by day 14—severe ventricular dilation, arrhythmia, and increased apoptosis. | (66) | |

| Epidermis | KRT14-Cre | Perinatal lethal, cell cycle block, and impaired development of both epidermis and hair follicle | (52) | |

| Blood | Mx-Cre | Hypocellular marrow, megakaryocte dysfunction, and reduction in erythrocytes/thrombocytes | (106) | |

| B cells | Mb1-cre, CD23-cre | Impaired differentiation and response to antigen | (107) | |

| Hdac3 | Germline | N/A | Embryonic lethal before E9.5 | (50, 68) |

| Liver | Alb-Cre | Altered metabolism, fatty liver, genomic instability, and HCC development | (10, 50) | |

| Blood | Vav-Cre | Loss of lymphoid populations, accumulation of multipotent progenitor cells, and impaired DNA replication | (93) | |

| Heart | αMHC-Cre | Lethal by 3–4 months. Cardiac hypertrophy, altered metabolism | (68) | |

| Bone | Osx-Cre | Runted animals, reduced bone density, and increased bone marrow adipogenesis | (79) | |

| T cells | CD4-Cre | Block in invariant natural killer T-cell development | (97) | |

| Macrophages | LysM-Cre; Mx-Cre | Skewing of macrophages toward alternative activation; loss of LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression | (15, 69) |

Hdac, histone deacetylase.

Although germ line deletion in mice yields a much more severe phenotype than transient inhibition using HDIs, these genetic experiments have provided key insights. Biochemically, HDAC1 and HDAC2 often have the same activity and co-purify. However, while deletion of Hdac1 was lethal by embryonic day 9.5, Hdac2-deficient mice exhibited perinatal lethality associated with cardiac defects, suggesting differences in Hdac1/2 function during development. Interestingly, cardiac-specific Hdac2-deletion did not result in a phenotype. However, αMHC-cre-mediated deletion of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 in the heart resulted in postnatal lethality associated with arrhythmia, severe ventricular dilation, and a three-fold increase in apoptosis in the heart (80). Importantly, the use of broad-spectrum HDIs, particularly Depsipeptide, has been associated with cardiac toxicities (59, 92, 105). These studies suggest that both HDAC1 and HDAC2 may significantly contribute to these adverse events.

It is notable that dramatic cardiac phenotypes did not manifest until both Hdac1 and Hdac2 were deleted. In vitro studies in MEF models revealed a compensatory upregulation of Hdac1 on Hdac2 loss and a similar upregulation of Hdac2 on acute Hdac1 deletion. However, deletion of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 resulted in a G1-phase cell cycle arrest, which may be partially attributed to the upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p21 and p57 (129, 131). A similar compensatory upregulation of these family members is observed in numerous cell types (64, 71, 80, 129, 131).

Are HDAC1 and HDAC2 tumor suppressors?

The propensity for compensation after deletion of either Hdac1 or 2 forced the conditional deletion of both Hdac1 and Hdac2 genes, and this analysis has changed the paradigm for how these proteins act during tumorigenesis. Mx1-Cre-mediated deletion of Hdac1/2 in the blood resulted in dramatic reductions in erythrocyte and thrombocyte levels after increases in megakaryocyte apoptosis (129). These results suggest that inhibition of HDAC1/2 functions may contribute to the thrombocytopenia and anemia associated with broad-spectrum HDIs currently in the clinic. Hdac1 and 2 also play important roles in lymphocyte development and function. Deletion of Hdac1/2 early in B-cell development resulted in a complete loss of B220+ cells in the spleen as well as dramatic reductions in immature B-cell populations in the marrow that were associated with a G1-cell cycle arrest and elevated apoptosis. Similarly, Hdac1/2-deficient mature B cells failed to proliferate and undergo apoptosis in response to mitogenic stimulation (131). Finally, Hdac1/2 deletion from T cells resulted in a reduction in total thymocytes associated with an increase in apoptosis and accumulation of cells at the double negative stage 3 (DN3) of development (45).

The fact that HDAC1 and 2 are found in complexes with both tumor suppressors [e.g., p53 (56, 84) and retinoblastoma protein (RB) (70, 73)] and oncogenes (e.g., BCL6, Fig. 2) highlights the complex roles of these proteins in cancer development as well as their response to therapy. Combinations of thymocyte-specific deletion of Hdac1 and/or Hdac2 alleles led to the spontaneous development of thymic lymphoma with penetrance increasing as Hdac activity was further decreased. Interestingly, while reductions in Hdac1 and 2 activity promoted tumorigenesis, suggesting a tumor suppressive role for these proteins, complete loss of Hdac1 and 2 function was not compatible with tumor development, suggesting that a minimal level of Hdac1/2 activity is required for lymphomagenesis (45). Similarly, knockdown of Hdac1 or Hdac2 in PML-RARα expressing pre-leukemic cells accelerated leukemogenesis, while knockdown of Hdac1 in fully leukemic cells had anti-leukemic effects and resulted in a significant increase in animal survival (104). Thus, in the early stages of leukemogenesis, Hdacs 1 and 2 may play tumor suppressive roles but remain a therapeutic target for established disease. These studies highlight the complex roles of Hdac1 and 2 in cancer development and maintenance, as well as identify a potential concern with the use of broad-spectrum HDIs, suggesting that prolonged reductions in HDAC1 and HDAC2 activity may promote therapy-associated secondary cancers.

It will be interesting to determine whether these complex roles for HDAC1 and HDAC2 in tumor development and maintenance can be attributed to the effects of HDAC1/2 function in the maintenance of genome stability. It is easy to envision a scenario where disruption of HDAC1/2 function in normal or premalignant cells could be associated with enhanced replication stress and DNA damage, resulting in the acquisition of mutations and genomic instability, and, ultimately, accelerating tumor formation. In contrast, fully transformed cells may be unable to cope with the replication stress and genomic instability associated with the loss of HDAC1/2 functions, therefore resulting in cancer cell killing in their absence.

Hdac3 and tumorigenesis

The active NCOR (or SMRT), inositol phosphate, Hdac3 complex is recruited by various sequence-specific transcription factors, including nuclear hormone receptors, to repress transcription. Consistent with a role for nuclear hormone signaling in metabolism, both cardiac- and liver-specific deletion of Hdac3 is associated with an altered metabolic phenotype resulting from deregulated gene expression (62, 82). Since mice with Hdac3-deleted livers were aged, signs of fibrosis were found and these mice, ultimately, died of hepatocellular carcinoma (13). Similar to the data with Hdac1/2 deletion in T lymphocytes, these data support a role for class I HDACs in tumor suppression. This could be due to a loss of heterochromatin (13), genomic instability (11), or deregulation of gene expression patterns that both control metabolic enzymes and regulate circadian rhythms (5, 62, 82).

Nuclear hormone receptors such as the RAR also play critical roles in the regulation of hematopoiesis, and the hematopoietic-specific Hdac3 deletion confirmed critical roles for Hdac3 in blood development. Vav-Cre-mediated deletion of Hdac3 in the hematopoietic stem cell resulted in a dramatic loss of lymphopoiesis coupled with bone marrow hypo-cellularity and mild anemia. Hdac3-deficient stem cells were severely defective in competitive bone marrow transplant assays, and reduced long-term culture initiating capacity further suggested a dramatic disruption of stem cell functions. Hdac3-deficiency also hindered normal differentiation, with cells accumulating at the multipotent progenitor stage of development. This block in differentiation was associated with severe reductions in both B and T cells as well as erythroid lineages (112). Given that both anemia and lymphopenia have been reported in patients treated with broad-spectrum HDIs, it is likely that abrogation of HDAC3 function contributes to these toxicities.

Mechanistically, a large percentage of these Hdac3−/− hematopoietic stem and progenitors incorporated BrdU into their DNA, even when injected into the mice, suggesting an accumulation of cells in the S phase. In addition, cultures of Hdac3−/− stem and progenitor cells failed to proliferate, suggesting defects in cell cycle control. DNA fiber labeling, which measures the movement of individual replication forks, demonstrated that Hdac3 deficiency reduced replication fork velocity, suggesting that the loss of Hdac3 hampered S-phase progression by directly affecting DNA replication rates. Moreover, even acute treatments of stem and progenitor cells with Depsipeptide resulted in a similar slowing of replication forks, suggesting that alteration of replication rates may be an immediate effect of HDAC inhibition (112). This rapid effect suggests that the defects are not due to altered transcriptional programs, but rather that Hdac3 has direct functions in replication. Combined, these data suggest that stem and progenitor cells lacking Hdac3 were impaired in their transit through the S phase, which further supports the idea that HDAC proteins play important and physiologically relevant roles in replication control.

HDI therapies that are approved for the treatment of cancer also possess anti-inflammatory effects resulting from reductions in inflammatory cytokine production (66). Macrophage-specific Hdac3 deletion models suggest that HDAC3 is a key target for the anti-inflammatory effects of HDIs. Activated macrophages are generally classified as either classically activated (M1) with a pro-inflammatory phenotype or alternatively activated (M2) and anti-inflammatory. In the absence of Hdac3 expression, macrophage polarization was shifted toward alternative activation. Furthermore, Hdac3 loss was protective in an inflammatory disease model (83). Consistent with these findings, in vitro stimulation of Hdac3−/− macrophages revealed a significantly impaired induction of pro-inflammatory transcriptional programs, which was associated with an impaired INF-β response (20). Finally, HDAC3 contributed to induction of inflammatory gene expression after IL-1 stimulation through its ability to remove inhibitory acetylation marks on NF-κB (135). These results are again consistent with the idea that inhibition of HDAC3 mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of broad-spectrum HDIs which are already in the clinic.

Conclusions: Targeting Replication, Transcription, or Inducing Synthetic Lethality?

The use of HDIs as nontargeted therapeutics continues to be tested in the clinic, but to date, the results have been modest. For instance, HDACs are recruited by oncogenic proteins such as BCL6 (10, 50, 51), PML-RARα (37), and AML1-ETO (7). While it appears that HDIs have efficacy in leukemia and lymphoma carrying these oncogenes, the responses were less dramatic than observed with targeted therapeutics (e.g., ATRA for PML-RARα). This could be due to collateral damage, as HDACs are also recruited by tumor suppressors such as p53 (56, 84) and RB (70, 73). Moreover, the two FDA-approved HDIs, Vorinostat (SAHA) and Romidepsin (Depsipeptide), were approved for the treatment of refractory CTCL (29, 118, 124), which does not contain an oncoprotein that recruits HDACs. While additional clinical trials are underway to assess the efficacy of a variety of HDIs in the treatment of both solid and hematologic malignancies, CTCL appears to be the tumor type most sensitive to HDI therapy, but the reason is still unknown.

In contrast to the clinical data, inhibition of HDACs in vitro has dramatic consequences and kills nearly every cell type tested. It is likely that the requirements for HDACs 1, 2, and 3 in DNA replication and DNA repair make these drugs potent tumor cell killers. Indeed, multiple model systems have demonstrated that either genetic deletion of HDACs or HDAC inhibition results in replication stress, impaired S-phase progression, and the accumulation of DNA damage. While these studies do not preclude the contribution of other HDAC-regulated processes to the effectiveness of HDAC-targeted therapies, it certainly raises the argument that the effects of HDIs on DNA replication may significantly contribute to their broad efficacy in vitro. This would also provide a mechanism for the therapeutic window, as rapidly cycling cancer cells lacking cell cycle checkpoints would be more sensitive to replication stress than the largely quiescent normal cells. However, these drugs have shown only moderate promise in the clinic, which raises the question as to whether the in vitro results have been “fools gold.”

Early-phase clinical trials are limited to patients for whom standard chemotherapy that targets DNA replication has already failed. If the broad spectrum of cell killing in vitro is primarily due to defects in DNA replication, it seems possible that the broad-spectrum effects in vitro might have led to clinical trials in the wrong types of cancers. Recent revelations might suggest that a more focused clinical approach is worth considering. For example, an inhibitor targeting the NCOR1:BCL6 interface has striking effects in preclinical models of BCL6-dependent lymphoma (Fig. 2) (19). While broad-spectrum HDIs had less of an effect, an HDAC3-selective inhibitor might synergize with the NCOR1 inhibitor in these lymphomas. This “pseudo targeted” approach is gaining traction for these diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but wider application to t(8;21)-containing acute myeloid leukemia seems appropriate based on biochemical and early clinical data (88).

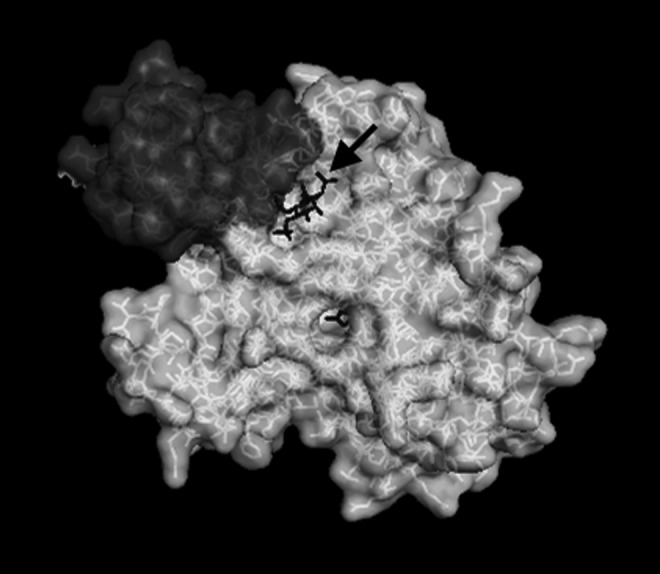

A second therapeutic avenue which has come from the class I HDAC gene deletion studies is that a minimal level of class I HDAC activity is required for cell survival (45). Thus, inactivating mutations of class I HDACs or their activating partners (NCOR1 or NCOR2) might not only contribute to tumorigenesis by inducing genomic instability, but would also sensitize the tumor cells to HDIs, causing synthetic lethality (45, 104). With the ever-growing genomic sequencing data emerging from The Cancer Genome Atlas and other sources, it is becoming obvious that inactivating mutations of class I HDACs occur at only moderate rates (Fig. 5), but their associated cofactors are mutated at much higher frequencies. In fact, NCOR1 and SIN3a were identified as frequently mutated genes, and these mutations were predicted to be inactivating mutations that “drive” tumorigenesis (28, 57). These tumors with reduced class 1 HDAC activity may be considered ideal clinical targets for HDIs with the synthetic lethality creating a wide therapeutic window. The incorporation of deep DNA sequencing of these genes into clinical trials and the development of more selective class 1 HDIs (9) will enable this synthetic lethal hypothesis to be tested in future genome-driven clinical trials.

FIG. 5.

TCGA identifies mutations and/or copy number alterations in HDACs 1, 2, and 3. Cancer genome sequencing analyses coordinated by the Cancer Genome Atlas have revealed alterations, including mutation, amplifications, and deletions of HDAC1, 2, and 3 in a number of tumor types (18, 33).

Abbreviations Used

- ATM

ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATRA

all-trans retinoic acid

- CAF-1

chromatin assembly factor 1

- CTCL

cutaneous T cell lymphoma

- DAD

deacetylase activating domain

- DDR

DNA damage response

- DN3

double negative stage 3

- DSB

double strand break

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HDI

histone deacetylase inhibitor

- HRR

homologous recombination repair

- iPOND

isolation of proteins on nascent DNA

- IR

ionizing radiation

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- NCOR1

nuclear hormone co-repressor 1

- NHEJ

nonhomologous end-joining

- ORC

origin recognition complex

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- RB

retinoblastoma protein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAHA

suberoyl anilide hydroxamic acid

- SMRT

silencing mediator of retinoid or thyroid-hormone receptors

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the members of the Hiebert lab for helpful discussions and editorial comments, and NIH grants R01-CA164605 and R01-CA141071 for support. K.R.S. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship award from the American Cancer Society.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Adimoolam S, Sirisawad M, Chen J, Thiemann P, Ford JM, and Buggy JJ. HDAC inhibitor PCI-24781 decreases RAD51 expression and inhibits homologous recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 19482–19487, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal BD. and Calvi BR. Chromatin regulates origin activity in Drosophila follicle cells. Nature 430: 372–376, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad A, Takami Y, and Nakayama T. WD repeats of the p48 subunit of chicken chromatin assembly factor-1 required for in vitro interaction with chicken histone deacetylase-2. J Biol Chem 274: 16646–16653, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alabert C. and Groth A. Chromatin replication and epigenome maintenance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 153–167, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alenghat T, Meyers K, Mullican SE, Leitner K, Adeniji-Adele A, Avila J, Bucan M, Ahima RS, Kaestner KH, and Lazar MA. Nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 govern circadian metabolic physiology. Nature 456: 997–1000, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aliouat-Denis CM, Dendouga N, Van den Wyngaert I, Goehlmann H, Steller U, van de Weyer I, Van Slycken N, Andries L, Kass S, Luyten W, Janicot M, and Vialard JE. p53-independent regulation of p21Waf1/Cip1 expression and senescence by Chk2. Mol Cancer Res 3: 627–634, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amann JM, Nip J, Strom DK, Lutterbach B, Harada H, Lenny N, Downing JR, Meyers S, and Hiebert SW. ETO, a target of t(8;21) in acute leukemia, makes distinct contacts with multiple histone deacetylases and binds mSin3A through its oligomerization domain. Mol Cell Biol 21: 6470–6483, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aparicio JG, Viggiani CJ, Gibson DG, and Aparicio OM. The Rpd3-Sin3 histone deacetylase regulates replication timing and enables intra-S origin control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 24: 4769–4780, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balasubramanian S, Verner E, and Buggy JJ. Isoform-specific histone deacetylase inhibitors: the next step? Cancer Lett 280: 211–221, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bereshchenko OR, Gu W, and Dalla-Favera R. Acetylation inactivates the transcriptional repressor BCL6. Nat Genet 32: 606–613, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhaskara S, Chyla BJ, Amann JM, Knutson SK, Cortez D, Sun ZW, and Hiebert SW. Deletion of histone deacetylase 3 reveals critical roles in S phase progression and DNA damage control. Mol Cell 30: 61–72, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhaskara S, Jacques V, Rusche JR, Olson EN, Cairns BR, and Chandrasekharan MB. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 maintain S-phase chromatin and DNA replication fork progression. Epigenetics Chromatin 6: 27, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhaskara S, Knutson SK, Jiang G, Chandrasekharan MB, Wilson AJ, Zheng S, Yenamandra A, Locke K, Yuan JL, Bonine-Summers AR, Wells CE, Kaiser JF, Washington MK, Zhao Z, Wagner FF, Sun ZW, Xia F, Holson EB, Khabele D, and Hiebert SW. Hdac3 is essential for the maintenance of chromatin structure and genome stability. Cancer Cell 18: 436–447, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishton MJ, Harrison SJ, Martin BP, McLaughlin N, James C, Josefsson EC, Henley KJ, Kile BT, Prince HM, and Johnstone RW. Deciphering the molecular and biologic processes that mediate histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood 117: 3658–3668, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruserud O, Stapnes C, Tronstad KJ, Ryningen A, Anensen N, and Gjertsen BT. Protein lysine acetylation in normal and leukaemic haematopoiesis: HDACs as possible therapeutic targets in adult AML. Expert Opin Ther Targets 10: 51–68, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgess AJ, Pavey S, Warrener R, Hunter LJ, Piva TJ, Musgrove EA, Saunders N, Parsons PG, and Gabrielli BG. Up-regulation of p21(WAF1/CIP1) by histone deacetylase inhibitors reduces their cytotoxicity. Mol Pharmacol 60: 828–837, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burhans WC. and Weinberger M. DNA replication stress, genome instability and aging. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 7545–7556, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, and Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov 2: 401–404, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerchietti LC, Ghetu AF, Zhu X, Da Silva GF, Zhong S, Matthews M, Bunting KL, Polo JM, Fares C, Arrowsmith CH, Yang SN, Garcia M, Coop A, Mackerell AD, Jr., Prive GG, and Melnick A. A small-molecule inhibitor of BCL6 kills DLBCL cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Cell 17: 400–411, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Barozzi I, Termanini A, Prosperini E, Recchiuti A, Dalli J, Mietton F, Matteoli G, Hiebert S, and Natoli G. Requirement for the histone deacetylase Hdac3 for the inflammatory gene expression program in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E2865–E2874, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Wang H, Yoon SO, Xu X, Hottiger MO, Svaren J, Nave KA, Kim HA, Olson EN, and Lu QR. HDAC-mediated deacetylation of NF-kappaB is critical for Schwann cell myelination. Nat Neurosci 14: 437–441, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chi P, Allis CD, and Wang GG. Covalent histone modifications—miswritten, misinterpreted and mis-erased in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 10: 457–469, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi YH. and Yoo YH. Taxol-induced growth arrest and apoptosis is associated with the upregulation of the Cdk inhibitor, p21WAF1/CIP1, in human breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep 28: 2163–2169, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clemente-Ruiz M. and Prado F. Chromatin assembly controls replication fork stability. EMBO Rep 10: 790–796, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conti C, Leo E, Eichler GS, Sordet O, Martin MM, Fan A, Aladjem MI, and Pommier Y. Inhibition of histone deacetylase in cancer cells slows down replication forks, activates dormant origins, and induces DNA damage. Cancer Res 70: 4470–4480, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courbet S, Gay S, Arnoult N, Wronka G, Anglana M, Brison O, and Debatisse M. Replication fork movement sets chromatin loop size and origin choice in mammalian cells. Nature 455: 557–560, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, and Tyler JK. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature 459: 113–117, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davoli T, Xu AW, Mengwasser KE, Sack LM, Yoon JC, Park PJ, and Elledge SJ. Cumulative haploinsufficiency and triplosensitivity drive aneuploidy patterns and shape the cancer genome. Cell 155: 948–962, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawson MA. and Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell 150: 12–27, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dobbin MM, Madabhushi R, Pan L, Chen Y, Kim D, Gao J, Ahanonu B, Pao PC, Qiu Y, Zhao Y, and Tsai LH. SIRT1 collaborates with ATM and HDAC1 to maintain genomic stability in neurons. Nat Neurosci 16: 1008–1015, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ekwall K, Olsson T, Turner BM, Cranston G, and Allshire RC. Transient inhibition of histone deacetylation alters the structural and functional imprint at fission yeast centromeres. Cell 91: 1021–1032, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filippakopoulos P. and Knapp S. The bromodomain interaction module. FEBS Lett 586: 2692–2704, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, and Schultz N. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 6: pl1, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glaser KB, Staver MJ, Waring JF, Stender J, Ulrich RG, and Davidsen SK. Gene expression profiling of multiple histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors: defining a common gene set produced by HDAC inhibition in T24 and MDA carcinoma cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther 2: 151–163, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gong F. and Miller KM. Mammalian DNA repair: HATs and HDACs make their mark through histone acetylation. Mutat Res 750: 23–30, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grausenburger R, Bilic I, Boucheron N, Zupkovitz G, El-Housseiny L, Tschismarov R, Zhang Y, Rembold M, Gaisberger M, Hartl A, Epstein MM, Matthias P, Seiser C, and Ellmeier W. Conditional deletion of histone deacetylase 1 in T cells leads to enhanced airway inflammation and increased Th2 cytokine production. J Immunol 185: 3489–3497, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grignani F, De Matteis S, Nervi C, Tomassoni L, Gelmetti V, Cioce M, Fanelli M, Ruthardt M, Ferrara FF, Zamir I, Seiser C, Lazar MA, Minucci S, and Pelicci PG. Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-alpha recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature 391: 815–818, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groth A, Rocha W, Verreault A, and Almouzni G. Chromatin challenges during DNA replication and repair. Cell 128: 721–733, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan JS, Haggarty SJ, Giacometti E, Dannenberg JH, Joseph N, Gao J, Nieland TJ, Zhou Y, Wang X, Mazitschek R, Bradner JE, DePinho RA, Jaenisch R, and Tsai LH. HDAC2 negatively regulates memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Nature 459: 55–60, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gui CY, Ngo L, Xu WS, Richon VM, and Marks PA. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor activation of p21WAF1 involves changes in promoter-associated proteins, including HDAC1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 1241–1246, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guillou E, Ibarra A, Coulon V, Casado-Vela J, Rico D, Casal I, Schwob E, Losada A, and Mendez J. Cohesin organizes chromatin loops at DNA replication factories. Genes Dev 24: 2812–2822, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haberland M, Johnson A, Mokalled MH, Montgomery RL, and Olson EN. Genetic dissection of histone deacetylase requirement in tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 7751–7755, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harikrishnan KN, Karagiannis TC, Chow MZ, and El-Osta A. Effect of valproic acid on radiation-induced DNA damage in euchromatic and heterochromatic compartments. Cell Cycle 7: 468–476, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He LZ, Tolentino T, Grayson P, Zhong S, Warrell RP, Jr., Rifkind RA, Marks PA, Richon VM, and Pandolfi PP. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce remission in transgenic models of therapy-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Clin Invest 108: 1321–1330, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heideman MR, Wilting RH, Yanover E, Velds A, de Jong J, Kerkhoven RM, Jacobs H, Wessels LF, and Dannenberg JH. Dosage-dependent tumor suppression by histone deacetylases 1 and 2 through regulation of c-Myc collaborating genes and p53 function. Blood 121: 2038–2050, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Helbling Chadwick L, Chadwick BP, Jaye DL, and Wade PA. The Mi-2/NuRD complex associates with pericentromeric heterochromatin during S phase in rapidly proliferating lymphoid cells. Chromosoma 118: 445–457, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hsiao KY. and Mizzen CA. Histone H4 deacetylation facilitates 53BP1 DNA damage signaling and double-strand break repair. J Mol Cell Biol 5: 157–165, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang L. and Pardee AB. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid as a potential therapeutic agent for human breast cancer treatment. Mol Med 6: 849–866, 2000 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang L, Sowa Y, Sakai T, and Pardee AB. Activation of the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter independent of p53 by the histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) through the Sp1 sites. Oncogene 19: 5712–5719, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huynh KD. and Bardwell VJ. The BCL-6 POZ domain and other POZ domains interact with the co-repressors N-CoR and SMRT. Oncogene 17: 2473–2484, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huynh KD, Fischle W, Verdin E, and Bardwell VJ. BCoR, a novel corepressor involved in BCL-6 repression. Genes Dev 14: 1810–1823, 2000 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacob C, Christen CN, Pereira JA, Somandin C, Baggiolini A, Lotscher P, Ozcelik M, Tricaud N, Meijer D, Yamaguchi T, Matthias P, and Suter U. HDAC1 and HDAC2 control the transcriptional program of myelination and the survival of Schwann cells. Nat Neurosci 14: 429–436, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jawerka M, Colak D, Dimou L, Spiller C, Lagger S, Montgomery RL, Olson EN, Wurst W, Gottlicher M, and Gotz M. The specific role of histone deacetylase 2 in adult neurogenesis. Neuron Glia Biol 6: 93–107, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnstone RW. and Licht JD. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy: is transcription the primary target? Cancer Cell 4: 13–18, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ju R. and Muller MT. Histone deacetylase inhibitors activate p21(WAF1) expression via ATM. Cancer Res 63: 2891–2897, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juan LJ, Shia WJ, Chen MH, Yang WM, Seto E, Lin YS, and Wu CW. Histone deacetylases specifically down-regulate p53-dependent gene activation. J Biol Chem 275: 20436–20443, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, Xie M, Zhang Q, McMichael JF, Wyczalkowski MA, Leiserson MD, Miller CA, Welch JS, Walter MJ, Wendl MC, Ley TJ, Wilson RK, Raphael BJ, and Ding L. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature 502: 333–339, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karagiannis TC. and El-Osta A. Chromatin modifications and DNA double-strand breaks: the current state of play. Leukemia 21: 195–200, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karagiannis TC. and El-Osta A. Will broad-spectrum histone deacetylase inhibitors be superseded by more specific compounds? Leukemia 21: 61–65, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim GD, Choi YH, Dimtchev A, Jeong SJ, Dritschilo A, and Jung M. Sensing of ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage by ATM through interaction with histone deacetylase. J Biol Chem 274: 31127–31130, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knott SR, Viggiani CJ, Tavare S, and Aparicio OM. Genome-wide replication profiles indicate an expansive role for Rpd3L in regulating replication initiation timing or efficiency, and reveal genomic loci of Rpd3 function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 23: 1077–1090, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knutson SK, Chyla BJ, Amann JM, Bhaskara S, Huppert SS, and Hiebert SW. Liver-specific deletion of histone deacetylase 3 disrupts metabolic transcriptional networks. EMBO J 27: 1017–1028, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lagger G, O'Carroll D, Rembold M, Khier H, Tischler J, Weitzer G, Schuettengruber B, Hauser C, Brunmeir R, Jenuwein T, and Seiser C. Essential function of histone deacetylase 1 in proliferation control and CDK inhibitor repression. EMBO J 21: 2672–2681, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.LeBoeuf M, Terrell A, Trivedi S, Sinha S, Epstein JA, Olson EN, Morrisey EE, and Millar SE. Hdac1 and Hdac2 act redundantly to control p63 and p53 functions in epidermal progenitor cells. Dev Cell 19: 807–818, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee JH, Choy ML, Ngo L, Foster SS, and Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor induces DNA damage, which normal but not transformed cells can repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 14639–14644, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leoni F, Zaliani A, Bertolini G, Porro G, Pagani P, Pozzi P, Dona G, Fossati G, Sozzani S, Azam T, Bufler P, Fantuzzi G, Goncharov I, Kim SH, Pomerantz BJ, Reznikov LL, Siegmund B, Dinarello CA, and Mascagni P. The antitumor histone deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid exhibits antiinflammatory properties via suppression of cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 2995–3000, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y, Kao GD, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Qin J, Phelan C, and Lazar MA. A novel histone deacetylase pathway regulates mitosis by modulating Aurora B kinase activity. Genes Dev 20: 2566–2579, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lindemann RK, Gabrielli B, and Johnstone RW. Histone-deacetylase inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. Cell Cycle 3: 779–788, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Flaus AJ, Waye MM, and Richmond TJ. Characterization of nucleosome core particles containing histone proteins made in bacteria. J Mol Biol 272: 301–311, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luo RX, Postigo AA, and Dean DC. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell 92: 463–473, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma P, Pan H, Montgomery RL, Olson EN, and Schultz RM. Compensatory functions of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and HDAC2 regulate transcription and apoptosis during mouse oocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E481–E489, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma P. and Schultz RM. Histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) regulates chromosome segregation and kinetochore function via H4K16 deacetylation during oocyte maturation in mouse. PLoS Genet 9: e1003377, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Groisman R, Naguibneva I, Robin P, Lorain S, Le Villain JP, Troalen F, Trouche D, and Harel-Bellan A. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature 391: 601–605, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mechali M. Eukaryotic DNA replication origins: many choices for appropriate answers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 728–738, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Millard CJ, Watson PJ, Celardo I, Gordiyenko Y, Cowley SM, Robinson CV, Fairall L, and Schwabe JW. Class I HDACs share a common mechanism of regulation by inositol phosphates. Mol Cell 51: 57–67, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller KM, Tjeertes JV, Coates J, Legube G, Polo SE, Britton S, and Jackson SP. Human HDAC1 and HDAC2 function in the DNA-damage response to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 1144–1151, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Milutinovic S, Zhuang Q, and Szyf M. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen associates with histone deacetylase activity, integrating DNA replication and chromatin modification. J Biol Chem 277: 20974–20978, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miotto B. and Struhl K. HBO1 histone acetylase activity is essential for DNA replication licensing and inhibited by Geminin. Mol Cell 37: 57–66, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades NS, McMullan CJ, Poulaki V, Shringarpure R, Hideshima T, Akiyama M, Chauhan D, Munshi N, Gu X, Bailey C, Joseph M, Libermann TA, Richon VM, Marks PA, and Anderson KC. Transcriptional signature of histone deacetylase inhibition in multiple myeloma: biological and clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 540–545, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Montgomery RL, Davis CA, Potthoff MJ, Haberland M, Fielitz J, Qi X, Hill JA, Richardson JA, and Olson EN. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 redundantly regulate cardiac morphogenesis, growth, and contractility. Genes Dev 21: 1790–1802, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Montgomery RL, Hsieh J, Barbosa AC, Richardson JA, and Olson EN. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 control the progression of neural precursors to neurons during brain development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 7876–7881, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Montgomery RL, Potthoff MJ, Haberland M, Qi X, Matsuzaki S, Humphries KM, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, and Olson EN. Maintenance of cardiac energy metabolism by histone deacetylase 3 in mice. J Clin Invest 118: 3588–3597, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mullican SE, Gaddis CA, Alenghat T, Nair MG, Giacomin PR, Everett LJ, Feng D, Steger DJ, Schug J, Artis D, and Lazar MA. Histone deacetylase 3 is an epigenomic brake in macrophage alternative activation. Genes Dev 25: 2480–2488, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Murphy M, Ahn J, Walker KK, Hoffman WH, Evans RM, Levine AJ, and George DL. Transcriptional repression by wild-type p53 utilizes histone deacetylases, mediated by interaction with mSin3a. Genes Dev 13: 2490–2501, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nakano K, Mizuno T, Sowa Y, Orita T, Yoshino T, Okuyama Y, Fujita T, Ohtani-Fujita N, Matsukawa Y, Tokino T, Yamagishi H, Oka T, Nomura H, and Sakai T. Butyrate activates the WAF1/Cip1 gene promoter through Sp1 sites in a p53-negative human colon cancer cell line. J Biol Chem 272: 22199–22206, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Naryzhny SN. and Lee H. The post-translational modifications of proliferating cell nuclear antigen: acetylation, not phosphorylation, plays an important role in the regulation of its function. J Biol Chem 279: 20194–20199, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nicolas E, Ait-Si-Ali S, and Trouche D. The histone deacetylase HDAC3 targets RbAp48 to the retinoblastoma protein. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 3131–3136, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Odenike OM, Alkan S, Sher D, Godwin JE, Huo D, Brandt SJ, Green M, Xie J, Zhang Y, Vesole DH, Stiff P, Wright J, Larson RA, and Stock W. Histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin has differential activity in core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 14: 7095–7101, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pasini D, Malatesta M, Jung HR, Walfridsson J, Willer A, Olsson L, Skotte J, Wutz A, Porse B, Jensen ON, and Helin K. Characterization of an antagonistic switch between histone H3 lysine 27 methylation and acetylation in the transcriptional regulation of Polycomb group target genes. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 4958–4969, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Peart MJ, Smyth GK, van Laar RK, Bowtell DD, Richon VM, Marks PA, Holloway AJ, and Johnstone RW. Identification and functional significance of genes regulated by structurally different histone deacetylase inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 3697–3702, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pettazzoni P, Pizzimenti S, Toaldo C, Sotomayor P, Tagliavacca L, Liu S, Wang D, Minelli R, Ellis L, Atadja P, Ciamporcero E, Dianzani MU, Barrera G, and Pili R. Induction of cell cycle arrest and DNA damage by the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat (LBH589) and the lipid peroxidation end product 4-hydroxynonenal in prostate cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med 50: 313–322, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Piekarz RL, Frye AR, Wright JJ, Steinberg SM, Liewehr DJ, Rosing DR, Sachdev V, Fojo T, and Bates SE. Cardiac studies in patients treated with depsipeptide, FK228, in a phase II trial for T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 12: 3762–3773, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rahmani M, Yu C, Reese E, Ahmed W, Hirsch K, Dent P, and Grant S. Inhibition of PI-3 kinase sensitizes human leukemic cells to histone deacetylase inhibitor-mediated apoptosis through p44/42 MAP kinase inactivation and abrogation of p21(CIP1/WAF1) induction rather than AKT inhibition. Oncogene 22: 6231–6242, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rangwala S, Zhang C, and Duvic M. HDAC inhibitors for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Future Med Chem 4: 471–486, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Razidlo DF, Whitney TJ, Casper ME, McGee-Lawrence ME, Stensgard BA, Li X, Secreto FJ, Knutson SK, Hiebert SW, and Westendorf JJ. Histone deacetylase 3 depletion in osteo/chondroprogenitor cells decreases bone density and increases marrow fat. PLoS One 5: e11492, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reichert N, Choukrallah MA, and Matthias P. Multiple roles of class I HDACs in proliferation, differentiation, and development. Cell Mol Life Sci 69: 2173–2187, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Richon VM, Sandhoff TW, Rifkind RA, and Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitor selectively induces p21WAF1 expression and gene-associated histone acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 10014–10019, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Robert C. and Rassool FV. HDAC inhibitors: roles of DNA damage and repair. Adv Cancer Res 116: 87–129, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rosato RR, Almenara JA, Maggio SC, Coe S, Atadja P, Dent P, and Grant S. Role of histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced reactive oxygen species and DNA damage in LAQ-824/fludarabine antileukemic interactions. Mol Cancer Ther 7: 3285–3297, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rosato RR, Wang Z, Gopalkrishnan RV, Fisher PB, and Grant S. Evidence of a functional role for the cyclin-dependent kinase-inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1/MDA6 in promoting differentiation and preventing mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis induced by sodium butyrate in human myelomonocytic leukemia cells (U937). Int J Oncol 19: 181–191, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Roy S, Packman K, Jeffrey R, and Tenniswood M. Histone deacetylase inhibitors differentially stabilize acetylated p53 and induce cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Differ 12: 482–491, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ruefli AA, Ausserlechner MJ, Bernhard D, Sutton VR, Tainton KM, Kofler R, Smyth MJ, and Johnstone RW. The histone deacetylase inhibitor and chemotherapeutic agent suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) induces a cell-death pathway characterized by cleavage of Bid and production of reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 10833–10838, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Russo T, Zambrano N, Esposito F, Ammendola R, Cimino F, Fiscella M, Jackman J, O'Connor PM, Anderson CW, and Appella E. A p53-independent pathway for activation of WAF1/CIP1 expression following oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 270: 29386–29391, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Santoro F, Botrugno OA, Dal Zuffo R, Pallavicini I, Matthews GM, Cluse L, Barozzi I, Senese S, Fornasari L, Moretti S, Altucci L, Pelicci PG, Chiocca S, Johnstone RW, and Minucci S. A dual role for Hdac1: oncosuppressor in tumorigenesis, oncogene in tumor maintenance. Blood 121: 3459–3468, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shah MH, Binkley P, Chan K, Xiao J, Arbogast D, Collamore M, Farra Y, Young D, and Grever M. Cardiotoxicity of histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res 12: 3997–4003, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sims JK. and Wade PA. Mi-2/NuRD complex function is required for normal S phase progression and assembly of pericentric heterochromatin. Mol Biol Cell 22: 3094–3102, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sirbu BM, Couch FB, and Cortez D. Monitoring the spatiotemporal dynamics of proteins at replication forks and in assembled chromatin using isolation of proteins on nascent DNA. Nat Protoc 7: 594–605, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sirbu BM, Couch FB, Feigerle JT, Bhaskara S, Hiebert SW, and Cortez D. Analysis of protein dynamics at active, stalled, and collapsed replication forks. Genes Dev 25: 1320–1327, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Song J, Lafont A, Chen J, Wu FM, Shirahige K, and Rankin S. Cohesin acetylation promotes sister chromatid cohesion only in association with the replication machinery. J Biol Chem 287: 34325–34336, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sowa Y, Orita T, Minamikawa S, Nakano K, Mizuno T, Nomura H, and Sakai T. Histone deacetylase inhibitor activates the WAF1/Cip1 gene promoter through the Sp1 sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 241: 142–150, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Strait KA, Warnick CT, Ford CD, Dabbas B, Hammond EH, and Ilstrup SJ. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce G2-checkpoint arrest and apoptosis in cisplatinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells associated with overexpression of the Bcl-2-related protein Bad. Mol Cancer Ther 4: 603–611, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]