Abstract

The reaction of Fe3(CO)12 with the dithiadiazacyclooctanes [SCH2N(R)CH2]2 affords Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)6 (R = Me, Bn). The methyl derivative 1Me was characterized crystallographically (Fe-Fe = 2.5702(5) Å). Its low symmetry is verified by variable temperature 13C NMR spectroscopy which revealed that the turnstile rotation of the S(CH2)Fe(CO)3 and S(NMe)Fe(CO)3 centers are subject to very different energy barriers. Although 1Me resists protonation, it readily undergoes substitution by tertiary phosphines, first at the S(CH2)Fe(CO)3 center, as verified crystallographically for Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)5(PPh3). Substitution by the chelating diphosphine dppe (Ph2PCH2CH2PPh2) gave Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)4(dppe), resulting from substitution at both the S(CH2)Fe(CO)3 and S(NMe)Fe(CO)3 sites.

Introduction

The iron carbonyls form an immense range of complexes with organosulfur ligands. Curiously almost all such complexes result from degradation of organosulfur compounds. Only a fraction of organosulfur ligands bind intact to iron carbonyls.[1] This trend highlights the tendency of iron(0) compounds to break C-S bonds, which in turn highlights the apparent high stability of iron carbonyl thiolates.

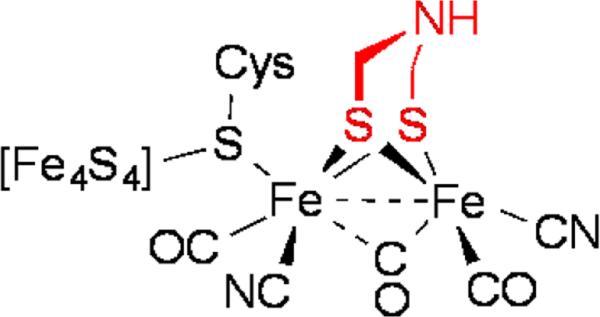

Iron carbonyl derivatives of S,N-compounds were uncommon, at least they were prior to the proposed,[2] now confirmed,[3] occurrence of the azadithiolate cofactor in the [FeFe]-hydrogenases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Active site of [FeFe]-hydrogenase highlighting the azadithiolate cofactor.

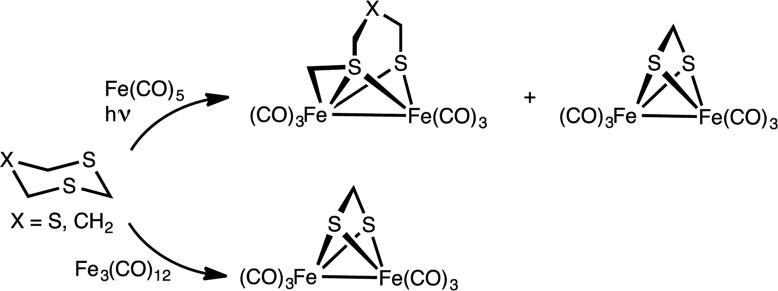

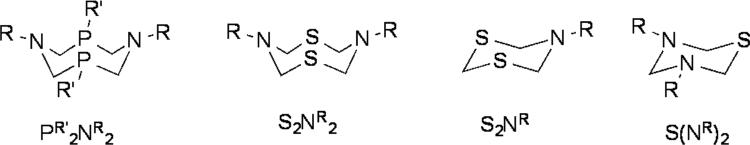

Although such diiron azadithiolates can be prepared by multiple routes,[4] such methods involve multistep conversions. We speculated that the [(SCH2)2NR]2- ligand (R-adt2-) could arise from the degradation of 8- or 6-membered S,N-heterocycles by Fe3(CO)12. Sulfur-nitrogen heterocycles are attractive reagents because they can be made in high yields by condensation of primary amines with hydrogen sulfide and formaldehyde.[5] They are structurally related to the P2N2 ligands popularized by DuBois et al. (Figure 2) [6].

Figure 2.

Heterocyclic compounds discussed in this work.

Our findings show that the S2NR2 heterocycles are cleaved by Fe3(CO)12 to yield organoiron complexes with bridging -CH2N(R)CH2S- moieties.

Results and Discussion

Reactions of S2N2R2 with Iron Carbonyls

The reaction of two equivalents of Fe3(CO)12 with S2NR2 produced organoiron compounds with the formula Fe2[SCH2N(R)CH2](CO)6 (1R, R = Me, Bn). The products were obtained in good yields as red colored powders after purification by column chromatography, which separates the product from Fe(CO)5 and traces of Fe2(SCH2S)(CO)6 (2). When the reaction was monitored by in-situ IR spectroscopy, we did not observe any intermediates. The synthesis can be represented by the idealized equation 1.

| (1) |

We propose that 2 arises via the reaction of Fe3(CO)12 with a small amount of S2NR generated by degradation of S2(NR)2 during the synthesis of 1Me. Consistent with this scenario, we demonstrated that 2 forms in moderate yields from the reaction of Fe3(CO)12 with S2NMe. The infrared spectra of 1Me and 1Bn in the νCO largely resemble that of Fe2((SCH2)2NH)(CO)6, the bands for 1R being ~5 cm-1 lower in energy than those for Fe2((SCH2)2 NH)(CO)6.

The structure of 1Me is supported by spectroscopic and crystallographic analysis. Two dimensional 1H-1H and 1H-13C correlation NMR spectra indicate that 1Me is chiral, and that the Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2] core is rigid. Signals for NCH2S (δ4.62, 3.51, 2H; δ73.8, 1C) were assigned by comparison to the SCH2S backbone of 2 (δ4.65, 2H); the FeCH2N group was therefore assigned to be the more downshifted signals in both the 1H and 13C NMR spectra (δ 2.73, 3.02, 2H; δ57.8, 1C). To assign the two C-H centers associated with the 4-bond coupling (“W-coupling”) in the spectrum of 1Me, we examined the dihedral angles of the -CH2-N-CH2-S-moiety containing the hydrogen atoms of interest (Table 1). Large W-coupling is associated with small dihedral angles (Φ).[7] Thus, since HC and HE are in planes with the smallest dihedral angle they will most likely exhibit the 4-bond coupling that is observed in the 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dihedral Angles and H-H Coupling Constants for the -CH2-N-CH2-S- Ligand of 1Me.

| Plane 1 | Plane 2 | Dihedral Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|

| HB-C5-N | N-C4-HD | 52.9 |

| HB-C5-N | N-C4-HE | 126 |

| HC-C5-N | N-C4-HD | 130 |

| HC-C5-N | N-C4-HE | 10.7 |

| Nucleus 1 (δ) | Nucleus 2 (δ) | ″JHH (Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| HA (2.17) | - | - |

| HB (2.73) | HC (3.02) | 7.34 (n = 2) |

| HC (3.02) | HE (4.62) | 2.91 (n = 4) |

| HD (3.51) | HE (4.62) | 7.54 (n =2) |

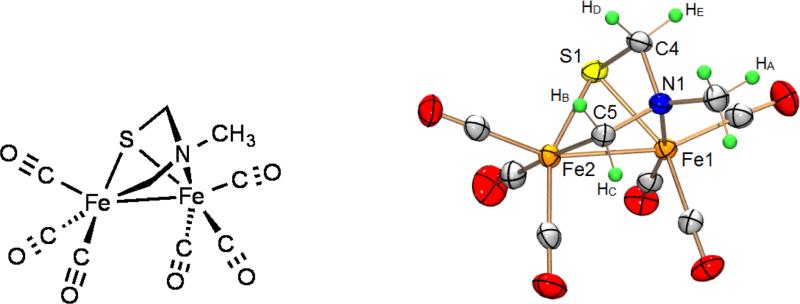

Crystallographic analysis confirmed that two Fe(CO)3 centers are bridged by thiolate and iminium-like[8] ligands. The Fe centers differ in that one is bonded to nitrogen (Fe-N = 2.0332(17) Å), and the other to an alkyl ligand (Fe-CH2 = 2.055(2) Å) (Figure 3). The Fe-Fe bond (2.5702(5) Å) is longer than related complexes with Fe2S2 cores (2.4924(7) Å).[4b] This elongation is attributed to the extended Fe-N(Me)-CH2-Fe linkage. Long has described a related Fe2(CO)6 complex with a μ-pyridyl group.[9] The Fe-Fe distance in that complex is comparable to that in 1Me.

Figure 3.

Two depictions of Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)6 (1Me) (thermal ellipsoids at 50% probability level).

Cyclic voltammogram of 1Me at various scan rates show a quasi-reversible reduction at Epc = -1.85 V vs Fc0/+ in CH2Cl2 (see SI). In comparison, Fe2[(SCH2)2CH2](CO)6 has been reported in the range of Epc = -1.61 to -1.74 V vs Fc0/+ in MeCN, and Fe2[(SCH2)2CH2](CO)6 is reduced at Epc = -1.58 V vs Fc0/+ in MeCN.[10] The shift in potential for 1Me in comparison to the iron dithiolate hexacarbonyl complexes may be partially attributed to the use of a less polar solvent. However, the more negative reduction potential for 1Me may also be attributed to increased electron density on the metal centers in comparison to the iron dithiolate hexacarbonyl complexes. This electron density difference was observed by FTIR as aforementioned, in which 1Me showed bands shifted to lower energy than Fe2[(SCH2)2NH](CO)6.

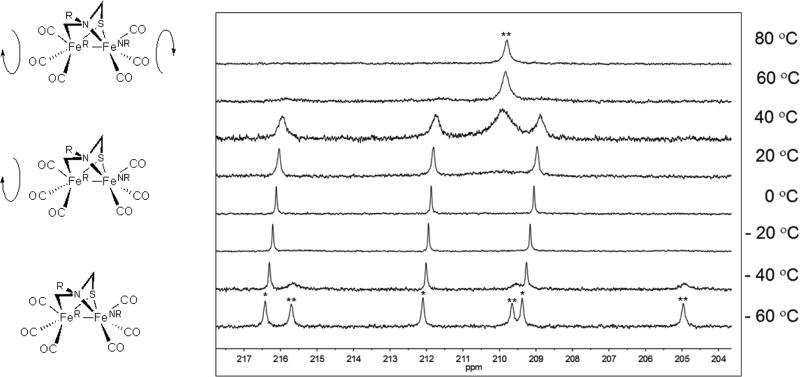

Dynamic NMR Studies of 1Me

Since 1Me is asymmetric, all six carbonyl ligands are inequivalent. At 22 °C, the 13C NMR spectrum (in the CO region) exhibits only three broad peaks at δ216, 212, and 209. These CO sites are located on what is referred to as the rigid iron center (FeR) because turnstile rotation of the CO sites is slow on the NMR timescale (Figure 4). At lower temperatures (< -36 °C), the remaining three signals for the CO ligands, those on the non-rigid iron center (FeNR), appear at δ216, 210, 205. At 41 °C four peaks are observed, three for the CO sites on the FeR center, and a broad singlet corresponding to the three CO sites on the FeNR center that have coalesced. Above 50 °C, only the coalesced signal for the CO sites on the FeNR center is observed. The differentiation of the FeNR(CO)3 vs the FeR(CO)3 centers is discussed below for the PMe3-substituted derivative of 1Me.

Figure 4.

Representation of dynamic processes of 1Me; FeNR = non-rigid, FeR = rigid. 13C NMR spectra (125.7 MHz, d8-toluene solution) of compound 1Me at various temperatures (right). The average chemical shifts for the CO signals on the FeR and FeNR centers are indicated with * and **, respectively.

The temperature dependence of the rates of two CO interchange processes followed Arrhenius behavior. This analysis revealed that the dynamics at FeNRproceed with an activation energy barrier of 10.8 (±0.65) kcal/mol, whereas the dynamic process for the FeR center occurs with a barrier of 16 (±0.85) kcal/mol. A change in the slope of the Arrhenius plot for the dynamic behavior of the FeNR center is observed at the extremes of the temperatures used. This suggests that different dynamic process may be in effect at differing temperature ranges, and that the calculated value is an average energy barrier for these processes. It is worth noting that at low temperatures (approaching - 60 °C) the viscosity of the solution could influence the broadness of the peaks in the 13C NMR, and influence the calculations of the energy barriers.

Monosubstituted Derivatives of 1Me

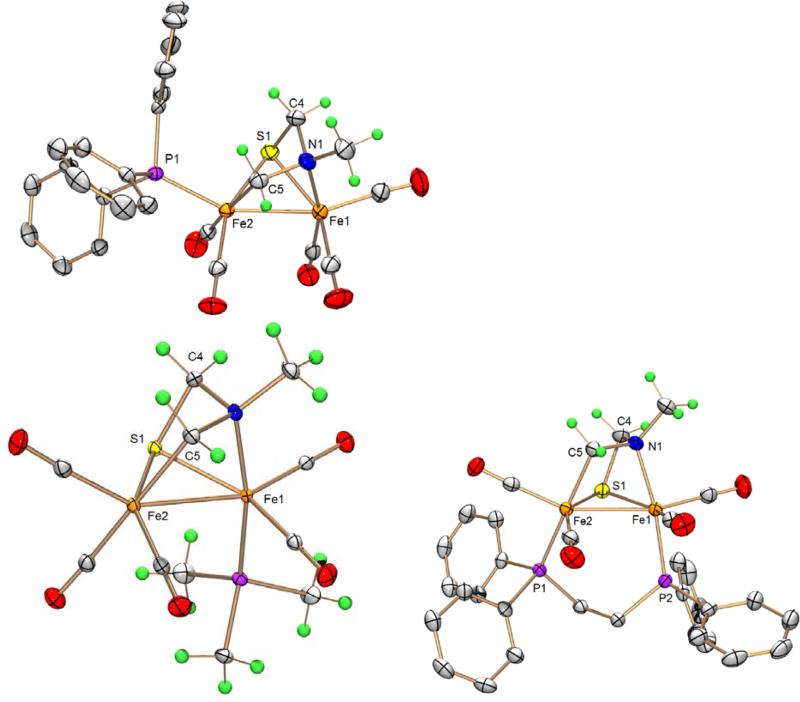

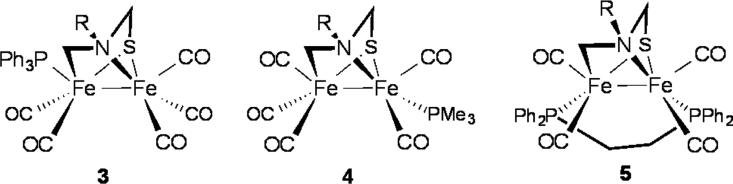

Treatment of 1Me with phosphine ligands in the presence of Me3NO·2H2O afforded monosubstituted derivatives Fe2(SCH2N(Me)CH2)(CO)5(PR3) (3Me, PR3 = PMe3 ;4Me, PR3 = PPh3). The 1H NMR signals for the aminothiolate ligand are relatively unchanged in both cases from that of 1Me. No 31P coupling to the 1H NMR nor the 13C NMR signals is observed. The molecular structure of the PPh3 derivative 3Me is similar to that of 1Me (Figure 5, Table 2). The phosphine is bound to the apical position of the Fe CH22 site (Figure 5). Owing to its low solubility, 3Me was not examined by DNMR spectroscopy. The overall structure of the PMe3 derivative 4Me is again similar to that of 1Me. The phosphine is however bound to a basal position of the Fe N1 site (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

ORTEP of Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)5 (PPh3) (3Me , top left), Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)5(PMe3) (4Me, top right), and Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)4(dppe) (5Me, bottom) with 50% probability thermal ellipsoids.

Table 2.

Bond distances of interest for crystallographically characterized complexes. All distances are given in angstroms.

| Fe1-Fe2 | Fe1-N1 | Fe2-C5 | Fe1-S1 | Fe2-S1 | Fen-Pm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Me | 2.5702 (4) | 2.033 (18) | 2.055 (2) | 2.258 (6) | 2.248 (6) | - |

| 3Me | 2.5771 (4) | 2.035 (16) | 2.062 (2) | 2.268 (6) | 2.250 (6) | Fe2-P1: 2.219 (6) |

| 4Me | 2.623 (5) | 2.039 (2) | 2.066 (2) | 2.260 (6) | 2.249 (6) | Fe1-P1: 2.211 (8) |

| 5Me | 2.648 (4) | 2.047 (18) | 2.018 (18) | 2.280 (6) | 2.250 (5) | Fe1-P1: 2.217 (7) |

| Fe2-P2: 2.222 (6) |

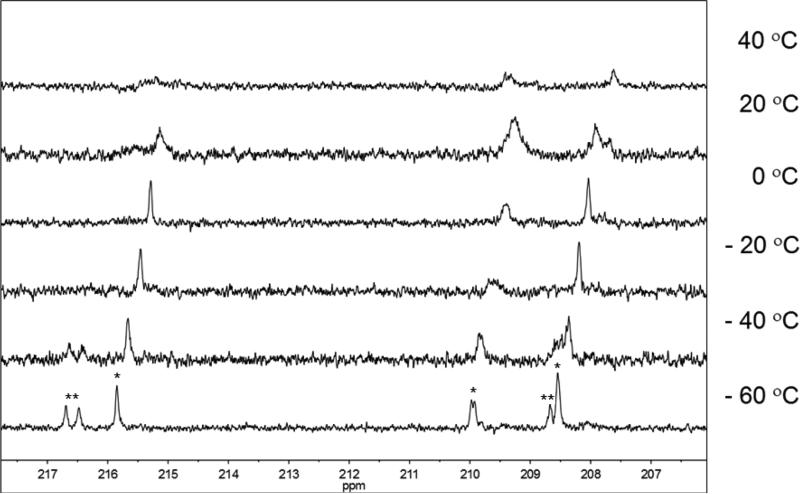

The high solubility of 4Me allowed examination of its low temperature NMR properties. Analogous to 1Me, three signals, albeit broadened, are observed in its 13C NMR spectrum at 215.8, 210, and 208.8δ at 20 °C (Figure 6). This observation suggests that the FeR center in 1Me and 4Me is FeCH2(CO)3. Upon cooling to - 60 °C all five CO sites of 4Me can be resolved, with two new signals corresponding to the FeNR or FeNMe(CO)2PMe3 center present at 216.6 and 208.7δ (see SI). The molecular structure of 4Me shows that the phosphine occupies the basal site of the FeNR center octahedral on the side of the sulfur atom. Based on the 13C NMR signals of 4Me it can concluded that the CO site of 1Me that is substituted to form 4Me corresponded to the peak at 205δ in the 13C NMR of 1Me. Coupling to phosphorus is observed for a non-rigid CO site, JPC = 27 Hz, which cannot be specifically assigned based on this data alone. As in 1Me, the CO sites on the FeR center begin to coalesce above 20 °C, and are too broad to be observed by NMR spectroscopy.

Figure 6.

13C NMR spectra (125.7 MHz, d8-toluene solution) of 4Me at various temperatures. Signals assigned to FeR(CO) (corresponding to FeCH2(CO)3) and FeNR (CO) (corresponding to FeNMe(CO)2PMe3) are indicated with * and **, respectively.

Disubstituted Derivatives of 1Me

Treatment of 1Me with dppe (dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane) in the presence of Me3NO·2H2O afforded the disubstituted derivative Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)4(dppe) (5Me, Figure 5 and 7). The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum shows two signals with JPP of 11.8 Hz. Its 13 C NMR spectrum shows four signals in the CO region (δ225, 224, 221, 214), each coupled to one phosphorus with JPC of ~ 17 Hz. Due to its poor solubility, 5Me was not examined by low temperature NMR spectroscopy. The molecular structure of 5Me confirms its similarity to 1Me. As with the PMe3 derivative 4Me, the phosphine on the Fe N1 side is trans to the amine, which causes an elongation of the Fe-N bond. The bridging of two metal centers by a dppe ligand in a similar fashion to that of 5Me has been observed for related diiron complexes.[11]

Figure 7.

Structures of the substituted derivatives of 1Me.

Conclusions

S2NR2 represent a fundamental class of S-N heterocycles, which have eluded study by the organometallic community. We show that they are readily cleaved by Fe(0) reagents to give diiron hexacarbonyls. The new azathiolate complexes are a rare examples of a chiral diiron hexacarbonyl in which the six diastereotopic carbonyl-carbon centers have been identified by NMR. Our ability to conduct these measurements is a result of the high solubility of 1Me in both polar and non-polar solvents even at very low temperatures (-60 °C).

Compounds containing the S-CH2-X group appear to be particularly reactive toward iron(0) carbonyls. In related work, the 1,3,5-trithiane is degraded by iron(0) carbonyls to give Fe2(SCH2SCH2SCH2)(CO)6 as well as the methanedithiolate Fe2(SCH2S)(CO)6 (Scheme 1).[12]

Scheme 1.

Activation of saturated C-S heterocycles by iron carbonyls, which are reminiscent of the results in this report.[12-13]

The selenium analogues of these complexes have recently been obtained from 1,3,5-triselenocyclohexane.[14]

The pathway leading to 1R (R = Me, Bn), as well as the SCH2SCH2 and SeCH2SeCH2 compounds is uncertain. With thioethers, iron carbonyls form complexes of the type Fe(CO)4(SR2)[15] and Fe3(CO)8 (μ-SC4H8)2. [16]

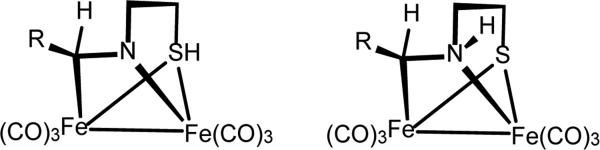

In related work, Hwang and coworkers described the compound Fe2[HS(CH2)2NCHR](CO)6 (R = 2-C5H3N-5-Me).[17] The structure of this complex was assigned on the basis of X-ray crystallography. Thiol ligands bridging two metals have been observed spectroscopically, but are typically very labile.[18] The results described in the present paper suggest that Huang's thiol complex might be reformulated as the Fe2[S(CH2)2N(H)CHR](CO)6 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Structures proposed by Huang et al (left)[17] and by this work for Fe2(RCHNC2H4S)(CO)6 (R = 2-methylpyridyl) (right).

Experimental Section

General Considerations

Unless otherwise stated, reactions were conducted using standard Schlenk techniques, and all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher. The heterocycles S2NBn2, S2NMe, and S2NMe2 proceeded as reported in the literature.[5, 19] Chromatography was conducted in air on 10 × 2.5 inch columns of silica gel (Silicycle, 40– 63μm). All other solvents were HPLC grade and purified using alumina filtration system (Glass Contour, Irvine, CA). NMR spectra were recorded on Varian UNITY 500 spectrometers. 1H NMR spectra (500 MHz) and 13C NMR spectra (100, 128 MHz) are referenced to residual solvent referenced to TMS. 31P{1H} NMR spectra (202 MHz) are referenced to external 85% H3PO4. FTIR spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer 100 FT-IR spectrometer. Elemental analyses were done on Exeter Analytical CE 440, and Perkin Elmer 2440, series II analyzers. X-ray crystallography data was obtained on a Bruker SMART instrument with an Apex II detector, using a Copper radiation source.

N,N′-Dimethyl-1,5-dithia-3,7-diazacyclooctane (S2NMe2)

The following is an optimized modification of the literature method.[5] Aqueous methylamine (40 %, 20 mL, 0.23 mmol) diluted with water (50 mL) was treated with cold formalin (34.6 mL, 0.46 mmol). After being stirred for 5 min at 0 °C, this solution was purged with H2S gas for 2 h causing precipitation of a white solid. After stirring the solution for an additional hour at 0 °C, the precipitate was collected and washed with cold ethanol (100 mL). The precipitate was purified by recrystallization by dissolving in 300 mL of hot acetone followed by cooling to 0 °C. Yield: 5.33 g (52%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 2.44 (s, 6H, NCH3), 4.24 (d, 4H, NCH2S), 4.52 (d, 4H, NCH2S). 13 C NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 38.2 (NCH3), 65.4 (NCH2S). 1H NMR (500 MHZ, CD2Cl2, δ): 4.49 (d, 4H, CH2); 4.25 (d, 4H, CH2); 2.40 (s, 6H, NCH3). Anal. Calcd for C6H14N2S2: C, 40.41; H, 7.91; N, 15.71. Found: C, 40.50; H, 7.90; N, 15.35. ESI-MS (m/z): 179 (MH+).

General Procedure for Reaction of S,N-Heterocycles with Fe3(CO)12

A slurry of the heterocycle and two mole equivalents of Fe3(CO)12 in THF was stirred for 20 h at room temperature under argon. The resulting dark red mixture was evaporated to dryness in vacuo, the residue was extracted in a minimum amount of hexane (15-30 mL). This extract was chromatographed on silica gel eluting with hexanes. Two closely spaced red bands were separated; the first band contained 2, and the second band contained 1 (see below). Each compound was recrystallized by dissolving in hexanes at room temperature followed by cooling to 0 °C.

Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2] (CO)6(1Me)

The general procedure was applied to the reaction of S2NMe2 (0.36 g, 2.0 mmol) and Fe3(CO)12 (2 g, 4.0 mmol) in 40 mL of THF. Yield, 2: 0.09 g (6%). Yield of 1Me: 0.62 g (84%). 13C NMR (127.7 MHz, d8-toluene, 20 °C): δ 52.68 (s, 1C, NCH3), 57.42(s, 1C, NCH2Fe), 73.05 (s, 1C, NCH2S). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 2.17 (s, 3H, NCH3), 2.73 (d, 1H, NCH2Fe), 3.03 (dd, 1H, NCH2Fe), 3.52 (d, 1H, NCH2S), 4.63 (dd, 1H, NCH2S). IR (hexanes): νCO = 2068 (s), 2024 (vs), 1995 (vs), 1981 (vs), 1964 (s) cm-1. Anal. Calcd for C9H7Fe2NO6S: C, 29.30; H, 1.91; N, 3.80. Found: C, 29.06; H, 1.83; N, 3.70.

Fe2[SCH2N(Bn)CH2](CO)6 (1Bn)

The above general procedure was applied to the reaction of S2N2Bn2 (0.22 g, 0.67 mmol) and Fe3(CO)12 (0.67 g, 1.3 mmol) in 20 mL of THF. Yield: 0.23 g (77%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.49 (d, 1H, NCH2Fe), 3.04 (dd, 1H, NCH2S), 3.20 (d, 1H, NCH2Fe), 3.31 (d, 1H, NCH2), 3.42 (d, 1H, NCH2), 4.69 (dd, 1H, NCH2S), 7.16-7.41 (m, 5H, C6H5). IR (hexane): νCO = 2067 (s), 2024 (vs), 1994(vs), 1980(vs), 1963 (s) cm–1. Anal. Calcd for C15H11Fe2NO6S: C, 40.48; H, 2.49; N, 3.15. Found: C, 40.55; H, 2.30; N, 3.14.

Fe2(SCH2S)(CO)6(2)

The general procedure was applied to the reaction of S2NMe (0.14 g, 1.0 mmol) and Fe3(CO)12 (1.0 g, 2.0 mmol) in 40 mL of THF. Yield: 0.12 g (33%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 4.65 (s, 2H, SCH2S). IR (hexane): νCO 2079 (s), 2039 (vs), 2007 (vs), 1999 (vs), 1987 (w) cm-1. 1H NMR and IR spectra matched published data.[12]

Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)5(PMe3)(4Me

A solution of 1Me (0.30 g, 0.811 mmol) in MeCN (50 mL) was treated with Me3NO·2H2O (0.09 g, 0.811 mmol) in MeCN (30 mL). The solution was stirred for 10 min. at room temperature until all starting material was consumed as detected by FTIR. The resulting dark red solution was treated with PMe3 (0.062 g, 0.811 mmol), and stirred for an additional 10 min. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo, and the solid was extracted into 5 mL of hexanes and chromatographed on silica (7 in by 0.5 in) in a glovebox. Hexanes were used remove first band followed by 95:5 hexanes: CH2Cl2 to obtain 4Me. The solvent was removed to yield a red solid that was recrystallized from hexanes at -40 °C. Yield: 0.171 g (45 %). 13C NMR (127.7 MHz, d8-toluene, 20 °C) δ 13.50 (d, 1C, P(CH3)3, JPC = 28.9 Hz),47.29 (s, 1C, NCH3), 52.01,(s, 1C, NCH2Fe), 67.77 (s, 1C, NCH2S), 207.9-215.13 (3s, 3 C, Fe(CO)3). 31 P{1H} NMR (202.3 MHz, d2-CH2Cl2): δ 70.6 (s). IR (CH2Cl2): νCO = 2034 (w), 2021 (w), 1968 (s), 1939 (m), 1905 (w) cm-1. Anal. Calcd for C11H16Fe2NO5PS: C, 31.68; H, 3.87; N, 3.36. Found: C, 31.67; H, 3.61; N, 3.39.

Reaction of 1Me with PPh3, and dppe

The diiron complex 1Me and one mole equivalent of the phosphine were dissolved in MeCN or CH2Cl2, and treated dropwise with one mole equivalent of Me3NO·2H2O in MeCN. The resulting mixture was stirred for 3 h at room temperature, and the solvent was evaporated to dryness in vacuo. The red solid was extracted in a minimum amount of CH2Cl2 (~10 mL), and chromatographed on silica gel with CH2Cl2 as the eluent. The dried red or orange powders were recrystallized from CH2Cl2 with hexanes.

Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2](CO)5(PPh3) (3Me)

The above general procedure was applied to reaction of 1Me (0.33 g, 0.75 mmol) and PPh3 (0.20 g, 0.75 mmol) in MeCN (30 mL) followed by a solution of Me3NO·2H2O (0.083 g, 0.75 mmol) in MeCN (15 mL). Yield: 0.31 g (61%). 13C NMR (127.7 MHz, CD2Cl2, 20 °C): δ 64.68 (s, 1C, NCH2Fe), 72.55 (s, 1C, NCH2S). 1 H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ 1.75 (d, 1H, NCH2Fe), 1.79 (d, 1H, NCH2Fe), 3.21 (d, 1H, NCH2), 3.27 (dd, 1H, NCH2S), 3.33 (d, 1H, NCH2), 4.16 (dd, 1H, NCH2S), 6.96-7.72 (m, 20H, C6H5). 31P{1H} NMR ( 202.3 MHz, d2-CH2Cl2): δ 70.6 (s). IR (hexane): νCO = 2042 (vs), 1979 (vs), 1971 (vs), 1957 (s), 1924 (s) cm-1. Anal. Calcd. for C26H22Fe2NO5PS: C, 51.77; H, 3.68; N, 2.32. Found: C, 52.27; H, 3.70; N, 2.48.

Fe2[SCH2N(Me)CH2(CO)4(dppe) (5Me)

The above general procedure was applied to reaction of 1Me (1.00 g, 2.7 mmol) and dppe (1.08 g, 2.7 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (50 mL); treated with Me3NO·2H2O (0.30 g, 2.7 mmol) in MeCN (35 mL). Yield: 0.821 g (97%). 13C NMR (100.3 MHz, dCD2Cl2): δ20.8 (t, 1C, PCH2CH2P), 27.3 (t, 1C, PCH2CH2P), 559.74 (d, 1C, NCH2Fe), 75.46 (d, 1C, NCH2S), 213.54-224.93 (4d, 4C, Fe(CO)2).1 H NMR (500 MHz, d2-CH2Cl2): δ2.06 (s, 3H, NCH3), 2.56 (dd, 1H, NCH2Fe), 3.02 (d, 1H, NCH2Fe), 3.68 (dd, 1H, NCH2S), 5.01 (d, 1H, NCH2S), 0.9-2.10 (m, 10H, PCH2CH2P), 7.37 7.95 (m, 20H, P(C5H6)2). [31]P 20] NMR (202.3 MHz, d2-CH2Cl2): δ 58.44 (d, PCH2CH2P, Jpp = 12 Hz), 65.65 (d, PCH2CH2P). IR (hexane): νCO = 2042 (vs), 1979 (vs), 1971 (vs), 1957 (s), 1924 (s) cm-1. Anal. Calcd for C33H31Fe2NO4P2S: C, 55.72; H, 4.39; N, 1.97. Found: C, 55.91; H, 4.34; N, 2.04.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by the U.S. NIH (grant GM061153-12). We thank Prof. G. S. Girolami for advice on the NMR spectroscopy, Dr. Jeffery Bertke for collecting crystallographic data, and Dr. Raja Angamuthu for help with initial experiments.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Spectroscopic data on new compounds.

References

- 1.a Linford L, Raubenheimer HG. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 1991;32:1–119. [Google Scholar]; b Mathur P. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 1997;41:243–314. [Google Scholar]; c Nametkin NS, Tyurin VD, Kukina MA. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1986;55:439–454. [Google Scholar]; d Ogino H, Inomata S, Tobita H. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:2093–2121. doi: 10.1021/cr940081f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolet Y, de Lacey AL, Vernede X, Fernandez VM, Hatchikian EC, Fontecilla-Camps JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1596–1601. doi: 10.1021/ja0020963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berggren G, Adamska A, Lambertz C, Simmons TR, Esselborn J, Atta M, Gambarelli S, Mouesca JM, Reijerse E, Lubitz W, Happe T, Artero V, Fontecave M. Nature. 2013;499:66–69. doi: 10.1038/nature12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Angamuthu R, Carroll ME, Ramesh M, Rauchfuss TB. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2011;2011:1029–1032. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201001208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lawrence JD, Li H, Rauchfuss TB, Bénard M, Rohmer M-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:1768–1771. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010504)40:9<1768::aid-anie17680>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li H, Rauchfuss TB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:726–727. doi: 10.1021/ja016964n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhmetova VR, Nadyrgulova GR, Niatshina ZT, Dzhemilev UM. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2009;45:1155–1176. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson AD, Fraze K, Twamley B, Miller SM, DuBois DL, Rakowski DuBois M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1061–1068. doi: 10.1021/ja077328d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobsen NE. NMR Spectroscoy Explained. Simplified Theory, Applications and Examples for Organic Chemistry and Structural Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams RD, Babin JE. Organometallics. 1988;7:963–969. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long L, Xiao Z, Zampella G, Wei Z, De GL, Liu X. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:9482–9492. doi: 10.1039/c2dt30798g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felton GAN, Mebi CA, Petro BJ, Vannucci AK, Evans DH, Glass RS, Lichtenberger DL. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009;694:2681–2699. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a Ezzaher S, Capon J-F, Gloaguen F, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:9863–9872. doi: 10.1021/ic701327w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Adam FI, Hogarth G, Kabir SE, Richards I. C. R. Chim. 2008;11:890–905. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raubenheimer HG, Linford L, van A. Lombard A. Organometallics. 1989;8:2062–2063. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaver A, Fitzpatrick PJ, Steliou K, Butler IS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:1313–1315. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harb MK, Niksch T, Windhager J, Görls H, Holze R, Lockett LT, Okumura N, Evans DH, Glass RS, Lichtenberger DL, El-khateeb M, Weigand W. Organometallics. 2009;28:1039–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Cane DJ, Graham WAG, Vancea L. Can. J. Chem. 1978;56:1538–1544. [Google Scholar]; b Meng X, Bandyopadhyay AK, Fehlner TP, Grevels F-W. J. Organomet. Chem. 1990;394:15–27. [Google Scholar]; c Cotton FA, Kolb JR, Stults BR. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1975;15:239–244. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotton FA, Troup JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:5070–5073. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu C-Y, Chen L-H, Hwang W-S, Chen H-S, Hung C-H. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004;689:2192–2200. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a Apfel U-P, Troegel D, Halpin Y, Tschierlei S, Uhlemann U, Görls H, Schmitt M, Popp J, Dunne P, Venkatesan M, Coey M, Rudolph M, Vos JG, Tacke R, Weigand W. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:10117–10132. doi: 10.1021/ic101399k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dong W, Wang M, Liu X, Jin K, Li G, Wang F, Sun L. Chem. Commun. 2006:305–307. doi: 10.1039/b513270c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zaffaroni R, Rauchfuss TB, Gray DL, De Gioia L, Zampella G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19260–19269. doi: 10.1021/ja3094394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a Cadenas-Pliego G, de Jesus Rosales-Hoz M, Contreras R, Flores-Parra A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 1994;5:633–640. [Google Scholar]; b Leonard NJ, Conrow K, Yethon AE. J. Org. Chem. 1962;27:2019–2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abel EW, Mittal PK, Orrell KG, Sik V. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1986:961–966. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.