Abstract

Background

Peanut oral immunotherapy (PNOIT) induces persistent tolerance to peanut in a subset of patients and induces specific antibodies which may play a role in clinical protection. The contribution of induced antibody clones to clinical tolerance in PNOIT is unknown, however.

Objective

We hypothesized that PNOIT induces a clonal, allergen-specific B cell response, which could serve as a surrogate for clinical outcomes.

Methods

We used a fluorescent Ara h 2 multimer for affinity-selection of Ara h 2-specific B cells, and subsequent single cell immunoglobulin amplification. Diversity of related clones was evaluated by next-generation sequencing (NGS) of immunoglobulin heavy chains from circulating memory B cells using 2×250 paired-end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform.

Results

Expression of class-switched antibodies from Ara h 2 positive cells confirms enrichment for Ara h 2 specificity. PNOIT induces an early and transient expansion of circulating Ara h 2 specific memory B cells that peaks at week 7. Ara h 2-specific sequences from memory cells have rates of non-silent mutations consistent with affinity maturation. The repertoire of Ara h 2-specific antibodies is oligoclonal. NGS-based repertoire analysis of circulating memory B cells, reveals evidence for convergent selection of related sequences in 3 unrelated subjects, suggesting the presence of similar Ara h 2-specific B cell clones.

Conclusions

Using a novel affinity selection approach to identify antigen-specific B cells, we demonstrate that the early PNOIT induced Ara h 2-specific BCR repertoire is oligoclonal, somatically hypermutated and shares similar clonal groups among unrelated individuals consistent with convergent selection.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, antigen-specific B cells, peanut allergy, food allergy, antibody repertoire

Introduction

IgE-mediated peanut allergy is one of the most serious food allergies due to its persistence and strong association with severe reactions, such as anaphylaxis.1, 2 In clinical trials, peanut oral immunotherapy (PNOIT) can significantly shift the threshold dose of peanut that can be ingested without symptoms in the majority of allergic patients through a gradual, incremental increase in oral peanut exposure under careful observation. The durability of this protective clinical effect once regular antigen administration ceases is highly variable however -- some individuals become more sensitive over time, while others appear to have long-lasting protection.3 A number of cellular and humoral immune responses have been associated with PNOIT and other forms of immunotherapy, including the suppression of mast cell and basophil reactivity to allergen, the deletion of Th2-skewed CD4 T cells, the induction of regulatory T cell populations and the induction of antigen-specific antibodies, including IgG, IgG4, and IgA.4-7 While many of these immune responses have been documented, few have been significantly or consistently correlated with clinical outcomes. In egg OIT, basophil suppression was correlated with the clinical effect immediately following therapy, but not with lasting protection.8 Demonstration of ‘blocking antibodies’ – capable of inhibiting IgE-mediated responses – first came more than 50 years ago in the context of subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy9-11, and such functional measures of antigen-specific antibody have correlated better with clinical outcomes than the concentration of antigen-binding antibodies in several studies.12, 13

Previous work comparing pre- and post-PNOIT serum from patients who underwent successful PNOIT demonstrated the development of epitope spreading within the IgE and IgG/IgG4 compartments to specific peanut antigens, suggesting that immunotherapy may increase the pool of cells producing specific antibodies.14 The emergence of new antigen-specific clones must be accomplished by the stimulation and expansion of a pool of B cells that has not yet terminally differentiated to secrete antibodies and retains the capacity to undergo BCR diversification, class switching and phenotypic differentiation. Further elucidation of the functional role of these cells – and therefore their mechanistic contributions of humoral immunity to OIT – has been limited by technical hurdles, however. One way to address the potential functional relevance of such OIT-induced changes is to isolate antigen-specific B cells and study them on a clonal level.

We hypothesized that we could recover peanut allergen-specific B cells from OIT patients using an affinity selection approach and that this method could be complemented with NGS-based analysis of the BCR repertoire to study antigen-specific responses. We focused on the allergen Ara h 2, as recent clinical studies have suggested that an Ara h 2-specific IgE response is most predictive of clinical hypersensitivity.15, 16 Using a fluorescent Ara h 2 multimer, we identified, enumerated and isolated allergen-specific B cells in patients undergoing PNOIT. Single-cell BCR cloning and expression was used to validate the affinity selection approach. Complementing this approach with NGS-based analyses of the memory BCR pool allowed us to more globally characterize the Ara h 2-specific BCR repertoire during PNOIT over time in three peanut allergic individuals.

Methods

Peanut oral immunotherapy trial

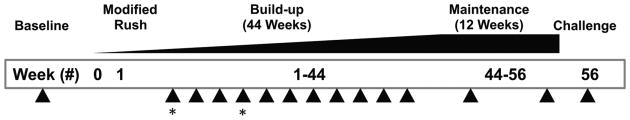

Peripheral blood was obtained after IRB-approved consent from peanut allergic participants of an open-label randomized trial of peanut OIT (NCT01324401). These study participants were 7-21 years old with a diagnosis of peanut allergy based on a clinical history of reaction to peanut within one hour of ingestion and either a positive skin prick test (>8 mm wheal) or elevated peanut-specific IgE (CAP FEIA >10 kU/L). The study schema, including time points of blood sampling, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Peanut oral immunotherapy clinical trial.

Patients aged 7-21 (N=22) with IgE-mediated peanut hypersensitivity (positive specific IgE, skin prick testing, and history of reaction) underwent PNOIT in a single-center, randomized trial (3:1, active:observational arm) using commercially available peanut flour. Patients recruited into the active arm underwent a one-day modified rush protocol for a maximum dose of 12mg, followed by a build-up period with escalating peanut doses every 2 weeks which included blood draws at every month (arrows), starting at 2 weeks. The build-up period was followed by a maintenance period of 3 months at 4000mg followed by an oral food challenge to assess tolerance. The 2 time points used for next generation-sequencing are noted using asterisks.

Multimer preparation

Purified native Ara h 2 (gift from Stef Koppelman) was biotinylated at lysine residues using a water-soluble biotin-XX sulfosuccinimidyl ester (Invitrogen). Fluorescent multimers were formed using stepwise addition of Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin (Invitrogen) to biotinylated Ara h 2 proteins until a 1:4 molar ratio was reached. The multimer was stored in the dark at 4°C until use.

Identification of Arah2+ circulating B cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by means of density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque Plus; GE Healthcare) from peripheral blood. These cells were then stained using CD3-APC (eBioscience clone OKT3), CD14-APC (eBioscience, clone 61D3), CD16-APC (eBioscience clone CB16), CD19-APC-Cy7 (BD Biosciences clone SJ25C1), CD27-PE (BD Pharmingen clone M-T271), CD38-Violet 421 (BD Biosciences clone HIT2), IgM-PE-Cy5 (BD Pharmingen clone G20-127), and AF488- Ara h 2 multimer. Normalization of AF488 was performed using Quantum Alexa Fluor 488 Molecules of Equivalent Soluble Fluorochrome (MESF) Beads (Bangs Laboratories, Inc). Flow cytometry was performed with an LSR II instrument (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using FlowJo 8.8.7 software (TreeStar). Experimental data was excluded from those samples which failed to meet quality control criteria; for example, samples with high background in the negative control (stained with the entire panel except for the Ara h 2 multimer) defined as >50 events per million CD19+ cells in the gate for multimer-positive cells were excluded (1.4% of 140 samples).

Single cell RT-PCR and immunoglobulin gene amplification

After using a similar staining procedure as above with PBMCs isolated from a PNOIT patient, single Arah2+CD19+ B cells were sorted using BD fluorescence-activated cell sorter Aria II into a 96-well plate (Eppendorf) containing 10uL of first strand buffer (Invitrogen) and 20 U Recombinant RNasin® Ribonuclease Inhibitor (Promega), and were subsequently frozen at -80°C. The following nested RT-PCR protocol was adapted from previous papers.17-19 The cells underwent heat lysis (65°C for 10 minutes, 25°C for 3 minutes, then 4°C) along with incubation with 3uL of NP40, and 150ng of random hexamers. The RT reaction was performed with first strand buffer (Invitrogen), 0.1mM DTT (Invitrogen), 2.5mM dNTP (Invitrogen), and SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). During the subsequent 2 PCR amplification rounds, in the first round, 5uL of template was used along with Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), and the second nested PCR used 3uL of template along with Pfu DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Primers for both rounds of PCR were modified from the previously published primer sets.18 The products from the second PCR were run on a 1.5% agarose gel to determine if heavy and light chains were successfully amplified (Figure E1). Successfully amplified products were Sanger sequenced (Genewiz Inc.) using second PCR primers. Consensus sequences combining both the forward and reverse sequences were determined using pairwise alignment in Geneious (Biomatters Ltd). These sequences were then analyzed using IMGT/V-BLAST,20-22 to identify germline V, D, and J sequences with the highest identity, CDR3 regions, and nucleotide and amino acid changes from germline sequence. Inference of antigen selection was performed using the Immunoglobulin Analysis Tool.23

Recombinant antibody production

Twenty-seven paired heavy and light chains were selected after sequencing as above. DNA from the second nested PCR of these heavy and light chains were purified using Qiaquick® 96 PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). A third PCR added restriction enzyme sites to the purified PCR product,17 followed by purification again using Qiaquick® 96 PCR Purification Kit. Restriction enzyme digestion with AgeI, BsiWI, Sall and XhoI (New England Biolabs) was prepared for ligation with linearized vectors containing human IgG1, kappa, or lamda constant domains, respectively (gift from Michel Nussenzweig). Competent E. coli NEB5α bacteria (New England Biolabs) were transformed at 42 °C (30 s) with the ligation produ ct, grown for 1.5 hours at 37°C, followed by selection on LB plates with 100ug/mL ampicillin. Ampicillin-resistant clones were selected and screened for vector insertion with colony PCR using forward and reverse primers19 followed by gel electrophoresis of PCR products on a 1% agarose gel. Plasmid DNA from overnight liquid cultures (LB with 100ug/mL ampicillin) of selected colonies which contained vectors was obtained using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). Plasmid DNA was sequenced using colony PCR primers to determine similarity to previous sequences in Geneious using pairwise alignment). Plasmid DNA (25ng) from selected heavy and light chains were transfected into HEK293 T cells using GenJet™ In Vitro DNA Transfection Reagent (SignaGen). Supernatants were harvested from cells after three days of culture at 37°C with 5% CO2 in serum free HL-1 media (Lonza) supplemented with Pen-Strep and 8mM Glutamax (Gibco).

Recombinant antibody characterization

Commercial ELISA assays (ImmunoCAP, Phadia) and protein microarrays validated the Ara h 2 specificity of the recombinant antibodies. Quantification of IgG antibodies was also validated using a cytometric bead assay (BD™ Cytometric Bead Array).

Next generation BCR sequencing

Ten to twenty million cryopreserved PBMCs from week 2 and week 14 during PNOIT were selected from three PNOIT patients in whom single-cell immunoglobulin amplification had been performed. Immunomagnetic peripheral memory B cells were isolated using Human Memory B Cell Enrichment Cocktail (Stemcell Technologies) with CD19+ negative selection followed by CD27+ selection using the manufacturers' directions. Cells were lysed in RLT buffer (Qiagen) supplemented with 1% β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). RNA was isolated using QIAquick EasyRNA Plus Purification kits (Qiagen), and one-fifth of the RNA was used for RT-PCR, using a previously published protocol.24 Briefly, cDNA was synthesized using Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and five constant region reverse transcriptase primers along with SUPERase-ln (Ambion). At the completion, RNAse H (Invitrogen) was used before PCR. Each of the eleven PCR reactions using Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen) contained 2μL of cDNA, primers for the five constant regions, and a separate leader region primer. PCR product purification was performed using Ampure Purification with a bead:product ratio of 1.8:1. Concentration and DNA quality was assessed by Bioanalyzer (Agilent) before sequencing. Commercial library preparation and sequencing services were used (Genewiz) for lllumina library preparation of 100ng cDNA (NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Preparation, New England BioLabs) followed by lllumina MiSeq 2×250 sequencing.

Analysis of next generation sequencing data

The next generation sequencing data analysis pipeline is detailed in the supplement (Figures E2-E3, Table E1). Forward and reverse read quality for each sample was examined using FastQC (Babraham Bioinformatics). SeqPrep (https://github.com/jstjohn/SeqPrep) was used to merge paired reads and trim lllumina adapters. Merged reads were filtered to a minimum length of 300bp. Sequences with a >99% homology were collapsed as unique reads.25 Sequence orientation and isotype determination was performed using leader sequence and constant region primer alignment allowing for 1 and 2 mismatches respectively. These sequences were then analyzed using IMGT/High V-QUEST26,27 to identify germline V, D, and J sequences with the highest identity, CDR3 regions, and nucleotide and amino acid changes from germline sequence. Python (http://www.python.org) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing)28 scripts used in the analysis are available on request.

Statistical Analysis

For longitudinal analysis, the time period was recoded as eight groups with approximately 15 observations per group (Table E2). The last group was dropped because of sparse data. In order to take into account the repeated aspect of the design, the reported means are least squares means from a linear mixed model. The relation between biomarkers and time was modeled using a generalized additive mixed model, which takes into account the non-linear relationship between variables and outcome and the longitudinal aspect of the design. The models were fitted using the mgcv29 packages in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing),28 the appropriate degrees of freedom for the smoothers were selected automatically using cross validation. Circos was used to make circular diagrams.30

Results

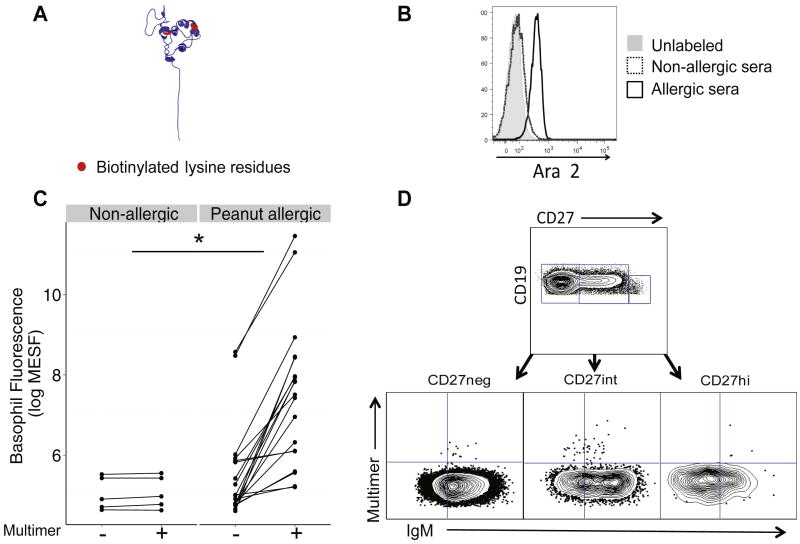

Ara h 2 multimer is specific

To validate the specificity of this reagent, we stained PBMCs with the Ara h 2 multimer (Figure 1, A) and analyzed basophils (CD123+CD203c+), which express high surface levels of bound IgE. We passively sensitized basophils from a non-peanut allergic donor with serum from an allergic (with Ara h 2 specific IgE) or non-allergic donor and stained those cells with multimer to demonstrate that only basophils sensitized with serum containing Ara h 2-specific IgE were fluorescent (Figure 1, B). Circulating basophils from patients undergoing PNOIT (N=19) had a significant shift in their fluorescence when stained with multimer, compared to healthy controls (N=5, P=0.05, Figure 1, C). Allergic subjects also had elevated levels of Ara h 2-specific IgE as measured by ImmunoCAP.

Figure 1. Fluorescent Ara h 2 multimer production and validation.

A, Four biotinylated Ara h 2 molecules (red = biotin) were conjugated to fluorescent streptavidin (SA). The multimer then could be used to identify B cells expressing a surface B-cell receptor (BCR) specific for Ara h 2 using flow cytometry. B, For multimer validation, basophils sensitized with serum from a peanut-allergic (black) but not a non-allergic donor (dotted) were specifically stained by the multimer (gray histogram represents unstained basophils). C, Circulating basophils from peanut allergic subjects undergoing PNOIT (N=19) and non-allergic subjects (N=5) were stained with and without the fluorescent Ara h 2 multimer (*P=0.05). Fluorescence was standardized using Alexa Fluor 488 MESF beads. D, CD3-CD14-CD16-CD19+ B cell subpopulations were defined based on their CD27 fluorescence. B cell subpopulations were defined as: Naïve B cells (CD19+CD27-IgM+), class-switched memory B cells (CD19+CD27intIgM-), and plasmablast cells (CD19+CD27hiIgM-). The multimer gate is determined based on the negative control (stained with the entire panel except for the multimer).

PNOIT increases the frequency of circulating multimer-positive memory B cells and specific immunoglobulins

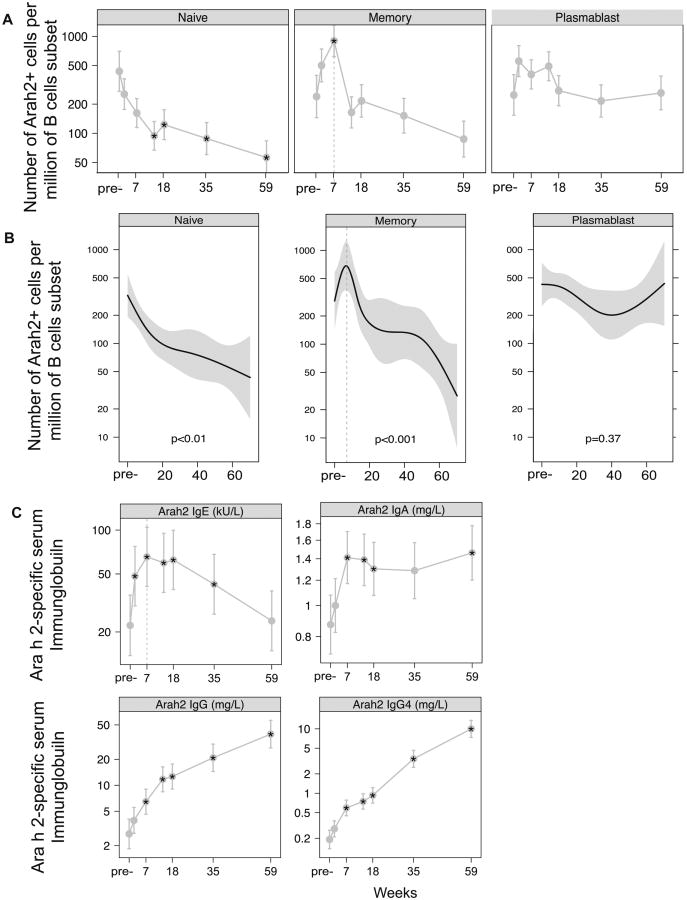

To identify Ara h 2-specific B cells within each B cell subset, we stained PBMCs with the multimer (Figure 1, D). For comparison between samples, we used the frequency of multimer-positive cells per million CD19+ B cells or per million class switched memory B cells. Figure 2 outlines the PNOIT study design. We found that the frequency of circulating Arah2-specific, class-switched memory B cells transiently increased after the initiation of PNOIT, by 3.2 fold within the entire CD19+ B cell population (P=0.06) and by 3.8 fold within the class-switched memory B cell population (P=0.03). This induction of multimer-positive memory B cells peaked around 7 weeks after the initiation of PNOIT (Figure 3, A). There was a similar trend of similar magnitude, though not statistically significant because of small numbers, in the plasmablast population. There was also a significant decrease at the end of PNOIT in the Arah 2 -positive naïve B cell population, both within the entire CD19+ B cell population (66% decrease, P=0.02) and within the naïve B cell compartment (80% decrease, P<0.01) (Figure 3, B).

Figure 3. Multimer-positive B cells and Ara h 2 immunoglobulins during the course of PNOIT.

A, The frequency of multimer-positive cells was normalized to the subset (naïve, memory, or plasmablast) population and described as the number of cells per million subset cells. B, Longitudinal analysis using a generalized additive mixed non-linear model demonstrates that multimer-positiveclass-switched memory B cell expansion within the memory B cell compartment occurs transiently during early PNOIT, peaking at week 7. C, Ara h 2-specific IgG, IgE, IgA, and IgG4 levels were measured longitudinally during PNOIT (N=22) by Phadia ImmunoCAP.

As seen in previous studies of PNOIT, Ara h 2-specific IgE levels transiently increased during early PNOIT, peaking at nearly double the starting value about seven weeks after the start of PNOIT and remained elevated above baseline until after week 35 (P<0.005). The Ara h 2-specific IgA, IgG, and IgG4 levels also rose significantly above baseline by week 7 and continued to rise through PNOIT (P<0.005, Figure 3, C).

Ara h 2 positive, class-switched B cells express highly mutated, Ara h 2-specific BCRs

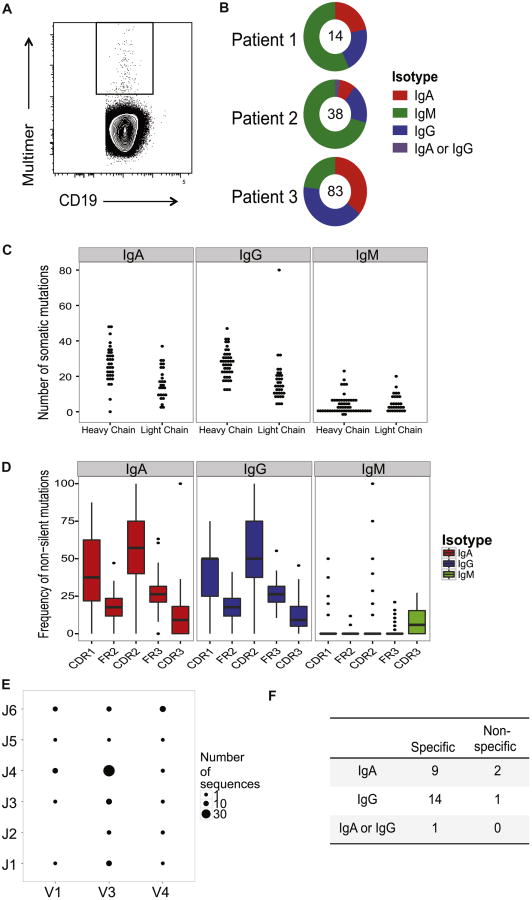

One month after beginning PNOIT in three unrelated subjects, 159 multimer-positive CD19+ B cells were sorted individually (Figure 4, A). Single-cell immunoglobulin by RT-PCR amplification yielded 135 heavy chains and 99 light chains (yield of 74%); nucleotide sequences were obtained by Sanger sequencing. Of these, there were 88 paired heavy and light chains from single cells.

Figure 4. Single-cell antibody cloning of multimer-positive B cells.

A, Individual multimer-positive CD19+ B cells were FACS sorted from 3 patients one month after initiation of PNOIT into a 96-well plate (sample shown above). B, Immunoglobulin heavy chain amplification from the 3 patients yielded of a total of 135 heavy chains, of which 40% were IgM, 32.6% were IgG, 26.7% were IgA and <1% could not be classified, based on identification by primer alignment of sequences. C, The frequency of somatic mutations is higher in the heavy chains compared to the light chains in the immunoglobulins amplified from sorted multimer-positive B cells. D, In amplified immunoglobilin heavy chain sequences, the frequency of non-silent mutations tend to be higher in the complementary determining regions (CDR) as opposed to the framework (FR) regions in IgA and IgG sequences compared to IgM sequences, suggestive of affinity maturation in the IgA and IgG immunoglobulin heavy chains. E, The distribution of heavy chain V-J gene usage is varied in the single-cell amplified immunoglobulins. F, From the 3 patients, a total of 40 recombinant antibodies were produced from paired transfection of HEK293 cells. While none of the IgM antibodies expressed were Ara h 2-specific, 24 of the 27 (89%) IgA or IgG antibodies were confirmed to be Ara h 2-specific by ImmunoCAP.

Of the 135 cloned immunoglobulin heavy chain sequences from multimer-positive B cells, 40% were IgM, 32.6% were IgG, 26.7% were IgA and <1% could not be accurately classified (Figure 4, B). As expected, the frequency of somatic mutations in the IgA and IgG heavy chain sequences was higher than that among IgM heavy chain sequences (Figure 4, C). This result was particularly true of mutations causing coding changes: the frequency of non-silent mutations in the heavy chain complementarity-determining regions (CDR) was significantly higher than in the framework regions (FR) of the IgA and IgG sequences (25 vs. 15.8, P=0.02 and 25 vs. 13.2, P<0.001) than IgM sequences (0 vs. 0, P=0.28) (Figure 4D). The heavy chain sequences from all 3 patients used a variety of V and J gene segments with the most abundant combination being V3-J4 (Figure 4, E).

To produce recombinant antibodies, we selected productive paired heavy and light chains, defined by IMGT analysis,26 from the single cell amplification of Ara h 2-positive B cells. A total of 27 antibodies were produced from the cloned IgA and IgG sequences, with three from the first patient, three from the second patient, and twenty-one from the third patient.

Of these antibodies, 24/27 (89%) were specific for Ara h 2 when characterized by ImmunoCAP (Table 2, Figure 4, F).

Table 2. Clonal groups within Arah2+ B cells.

From the Ara h 2 affinity selected single cell immunoglobulin amplification, clonal groups were identified as those sharing the same IgH V-J gene segment and similar CDR3 sequence (≤ 2 amino acid differences). Within clonal groups, differences in IgH CDR3 sequences, IgL V-J gene usage, and IgL CDR3 sequences are highlighted. Ara h 2 specificity of expressed antibodies was determined by ImmunoCAP. Blank entries represent antibodies or sequences which were unable to be sequenced or expressed.

| Clonal Group | IgH V-J | IgH CDR3 Amino Acid Sequence | Isotype | Antibody | Ara h 2 Specificity | IgL V-J | IgL CDR3 Amino Acid Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IGHV1 |

|

IgG | P12 | + | IGKV3- IGKJ1 | QQRSDWYMWT |

| IGHJ4 | IgA | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| 2 | IGHV3 IGHJ1 |

|

IgA | ||||

| IgA | |||||||

| IgG | |||||||

| IgA | * | IGKV1- IGKJ4 | QQYDNLSLT | ||||

| IgA | |||||||

|

| |||||||

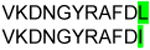

| 3 | IGHV3 | VKDGGLRYFQH | IgG | IGKV1- IGKJ5 | Non-productive | ||

| IGHJ1 | VKDGGLRYFQH | IgG | IGKV2- IGKJ2 | Non-productive | |||

|

| |||||||

| 4 | IGHV3 |

|

IgA | * | IGKV2- IGKJ1 |

|

|

| IGHJ2 | IgA | P13 | + | IGKV2- IGKJ1 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 5 | IGHV3 |

|

IgG | ||||

| IGHJ3 | IgG | P21 | + | IGKV2- IGKJ1 | MQALQRWT | ||

|

| |||||||

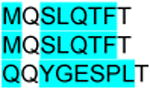

| 6 | IGHV3 |

|

IgG | P3 | + | IGKV2- IGKJ1 | MQSLQTWT |

| IGHJ3 | IgA | * | IGKV2- IGKJ1 | MQSLQTWT | |||

|

| |||||||

| 7 | IGHV3 |

|

IgG | * | IGLV1- IGLJ3 | AVWDDSLNGWV | |

| IGHJ3 | IgA | * | IGLV1- IGLJ3 | AVWDDSLNGWV | |||

|

| |||||||

| 8 | IGHV3 IGHJ4 |

VKDGGLRYFDS | IgA | P33 | + | IGKV2- IGKJ3 |

|

| VKDGGLRYFDS | IgA | P34 | + | IGKV2- IGKJ3 | |||

| VKDGGLRYFDS | IgA | P35 | - | IGKV3D-IGKJ1 | |||

|

| |||||||

| 9 | IGHV3 | VKDSGLRSLQY | IgA | P39 | + | IGKV2- IGKJ1 | MQAQQSWT |

| IGHJ4 | VKDSGLRSLQY | IgG | IGKV2- IGKJ1 | Non-productive | |||

|

| |||||||

| 10 | IGHV3 | ARDRGYSYGYYYYGMDV | IgM | ||||

| IGHJ6 | ARDRGYSYGYYYYGMDV | IgM | P27 | - | IGKV2- IGKJ1 | MQAQQTWT | |

Unable to express antibody through recombinant cloning.

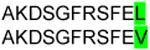

Ara h 2-specific responses are oligoclonal

We addressed the question of related clonal diversity of the 135 affinity selected BCR heavy chain (IgH) library by examining the CDR3 regions of sequences sharing the same V-J gene usage. If the amino acids in the CDR3 region were the same or differed by 2 or fewer amino acids, the sequences were grouped as highly related, most likely arising from the same parent clone and therefore referred to as a clonal group. Among the representative Ara h 2-specific sequences, a total of 10 clonal groups were identified (Table 2), capturing 18% of sequences (Figure E4). Half of these clonal groups included both IgA and IgG sequences, consistent with the likelihood that sequences in this group derive from a shared ancestral clone that differentiated to both IgA and IgG isotypes. Figure E5 shows the number and distribution of sequences that appeared as related or unique clones.

Of note, within these heavy chain clonal groups, several of the paired light chains were distinct from each other, suggesting that light chain promiscuity may exist in the Ara h 2-specific antibodies.

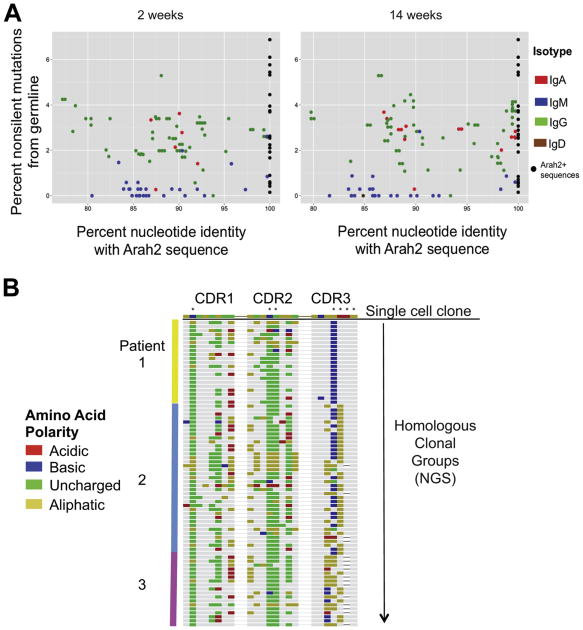

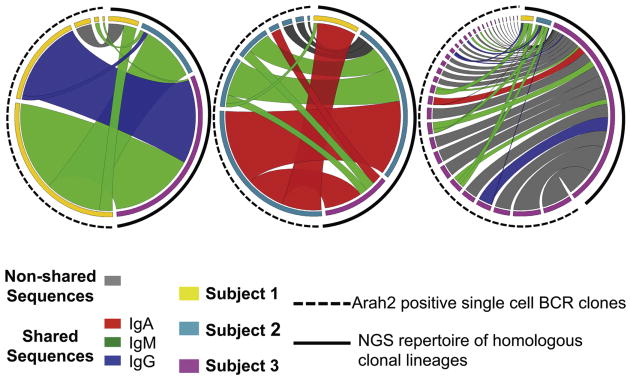

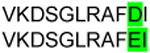

Stereotyped Ara h 2-specific clones present between unrelated individuals

To further analyze the antigen-specific B cell repertoire of these patients, next generation sequencing (NGS) of the BCR heavy chains from isolated CD19+CD27+ B cells was performed at two time points (weeks 2 and 14) before and after the peak induction of Ara h 2-specific memory B cells observed by flow cytometry (Figure 3). We used the 135 IgH sequences of Ara h 2-specific single B cells described above to identify clonal groups (same V and J segment usage and a CDR3 ≤ 2 amino acid substitutions) within the sequenced repertoires.

A total of 46 clonal groups (relating to 34% of the 135 IgH sequences) were identified by this definition. The number of clonal groups varied between patients (5 from patient 1, 7 from patient 2, 34 from patient 3). The number of homologous corresponding NGS sequences within each clonal group varied between 1 and 187 (median 13.5).

Similar to the IgH sequences identified by affinity selection, the homologous sequences from the NGS library within the IgG and IgA compartments had undergone high rates of somatic hypermutation (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Identity of Ara h 2 homologous sequences within the NGS repertoire to their affinity-selected Ara h 2 single-cell sequence counterparts.

A, Ara h 2 similar sequences within the NGS repertoire are shaded by their isotypes while the multimer-identified Ara h 2 sequences are represented as black dots. The Ara h 2 homolgous sequences on the x-axis demonstrate strong nucleotide similarity with the multimer identified Ara h 2 sequences. Class-switched IgA and IgG sequences are more highly mutated than IgM from germline. These graphs are representative. B, The CDR 1, 2, and 3 regions of homologous NGS sequences from all 3 patients are aligned to a representative Ara h 2 affinity-selected sequence from Patient 2. Colored amino acid residues represent disagreements with the Ara h 2 multimer-identified sequence while similar residues are gray. Colors represent polarity of the amino acid residues. Asterisks mark amino acid substitutions from the germline sequence.

Visualization of these clonal groups (Figure 5) within the NGS repertoire highlights an apparent convergence in selection between individuals. These stereotyped clones between individuals are extensively homologous and share non-germline encoded amino acids not only within the CDR3 but at CDR1 and 2 as well (Figure 6, B).

Figure 5. Stereotyped Ara h 2 clones within the NGS repertoire.

In each diagram, individual multimer-identified Ara h 2 sequences on the left were mapped to homologous sequences (same V-J gene segment with similar CDR3) within the NGS repertoire represented on the right. Colors on the outer left edge of the circle represent the subject origin of either the Ara h 2 sequence (on the left) or NGS repertoire (on the right). Ribbon width represents the relative frequency of the homologous sequence or clonal group, allowing for a relative comparison of the frequency of homologous sequences in the NGS repertoire to the Ara h 2 single cell sequence. Ribbon color (by the isotype of the Ara h 2 sequence) highlights those clones shared among unrelated subjects, with gray ribbons showing the subject-specific clonal groups.

Discussion

Previous clinical PNOIT studies have reproducibly demonstrated that antigen-specific immunoglobulins change during the course of PNOIT; however, further investigation of clonal antigen-specific responses to immunotherapy has been technically limited by our inability to reliably detect the low frequency population of antigen-specific B cells.

In this paper, we demonstrated the use of a novel fluorescent Ara h 2 multimer to identify Ara h 2-specific class-switched memory B cells by BCR affinity. Previous efforts to identify allergen-specific cells used several approaches such as transformation of circulating B cells using various activating stimuli31-33 and fluorescently labeled monomeric antigens,34, 35 though low fluorescence and nonspecific binding of B cells can result in a poor signal-to-noise ratio when compared with fluorescent antigen multimers.36

We further confirmed the approach by expressing Ara h 2 antibodies from sorted multimer-positive B cells and testing their specificity. We focused on the peanut antigen Ara h 2 due to its clinical relevance and importance in the function of allergic effector cells, but this approach should prove feasible to study B cell responses to other allergens as well. Using this technology, we have shown that a transient indication of circulating allergen specific B cells occurs early in peanut oral immunotherapy.

The kinetics of the induced antigen-specific memory B cell population demonstrates that the rise in Ara h 2-specific IgA, IgG, and IgG4 begins at about the same time as the peak expansion of this population – around week 7. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin induction has been reproduced in several trials of peanut immunotherapy.4, 7 Recent work using a peptide microarray-based assay suggests that antigen-specific antibody diversification also occurs in peanut immunotherapy.14 The induction of the Ara h 2 specific B cells found here is consistent with that observation. The early and transient increase in allergen-specific IgE during PNOIT occurs on a similar kinetic time scale as the expansion in the memory B cell population. The increase in epitope diversity described in the work by Vickery, et.al., 14 is another interesting avenue worth further exploration, as the increase in allergen-specific memory B cells may contribute to the expansion of this secreted allergen-specific IgE pool, and further phenotyping of this population may prove to be interesting in understanding some aspects of allergen-specific IgE memory. The frequency of antigen-specific B cell induction varies considerably among patients, raising the question of whether this variable could correlate with long-term clinical efficacy in patients undergoing PNOIT, as has been suggested in infection and vaccination.37 Previous studies have also demonstrated that there is significant heterogeneity of epitopes recognized by peanut-specific antibodies and have associated that with functional and clinical consequences raising and indirectly supporting the hypothesis that epitope diversity is an important feature of humoral response.38, 39 The approach taken here-- analyzing the diversity of the allergen-specific repertoire comprehensively and recovering and directly evaluating antibody function-- promises to significantly advance the capacity for studying the mechanistic consequence of clonal diversity and epitope specificity.

The recovered immunoglobulins from Ara h 2-specific class-switched B cells exhibited somatic hypermutation, consistent with affinity maturation and oligoclonality, as would be expected during an antigen-driven humoral response (Figure E5).23, 40 Furthermore, using the affinity selected Ara h 2-specific immunoglobulin heavy chain sequences to interrogate the NGS-derived library of memory B cell IgH repertoire, we characterized clonal groups of IgH sequences. These clonal groups were often present as multiple isotypes, consistent with an antigen-driven response that had undergone class switching. Despite their divergence from germline sequence, a subset of these sequences was found to be present between the three unrelated patients analyzed. These observations further support the possibility that these homologous sequences among unrelated patients may represent public clones – a finding only recently described in human B cell studies,41-43, though this study is somewhat limited by sample size. These shared clonal groups not only used the same V and J gene segments and had nearly identical CDR3 regions by definition; CDR1 and CDR2 sequences were also highly homologous. This information could inform structure-function studies to define critical mutations for Ara h 2 binding.

Of the affinity-selected Ara h 2-specific sequences used to identify shared Ara h 2 clonal groups, the IgG and IgA sequences exhibited extensive somatic hypermutation, and therefore, their homology does not simply reflect germline similarity. Furthermore, individual CDR3 repertoires have been shown to be highly unique, even between related individuals.44, 45 Previous work has suggested that the antibody repertoire in response to persistent antigen stimulation may induce additional stochastic and random nucleotide changes within the BCR repertoire, further increasing the likelihood of having clonal antibody divergence among individuals.24 These observations further support the idea that these homologous sequences among unrelated patients may represent public clones.

Evidence of convergent antibody signatures (i.e., ‘public clones’) such as these Ara h 2-specific clonal groups, have recently been observed in the context of Dengue fever as well as influenza41, 42 and their identification here suggests several possibilities about their ontogeny. The most straightforward possibility is that the BCR repertoire to Ara h 2, a small and dominant B cell antigen in peanut allergy, is highly constrained by selective pressures during clonal affinity maturation and selection, leading to convergence upon these public clones. The other possibility is that the BCR repertoire of peanut allergic patients underwent other selective pressures (e.g., microbiome, other environmental exposures) that encouraged similar selection of their memory B cell response, leading to similar BCR sequences and perhaps even an increased likelihood of peanut allergy by favoring the development of high affinity Ara h 2 specific antibodies.

Regardless of ontogeny, the presence of these shared clonal groups raises the possibility that protective antibodies induced by immunotherapy could have similar features (e.g., epitope specificity) between individuals and therefore play a role in effective PNOIT outcomes. Future studies in multicenter trials with diverse patient populations will likely be helpful in further defining the types and diversities of public clones, their ontogeny, and their potential significance in the induction of durable tolerance in PNOIT.

Supplementary Material

Figure E1: Frequency of multimer+ B cell subsets in allergic and non-allergic subjects

The frequency of multimer-positive cells was normalized to the subset (naïve, memory, or plasmablast) population and described as the number of cells per million subset cells or per million CD19+ B cells in either peanut allergic pateints from the PNOIT trial before the start of PNOIT compared to non-allergic control patients. Basophil staining of the non-allergic control patients is shown in Figure1c.

Figure E2: Single cell immunoglobulin amplification

Immunoglobulin amplification of heavy and light chains was performed using single cell, nested RT-PCR. In this example, gel electrophoresis demonstrates recovery of 17 out of 24 paired heavy and light chains.

Figure E3: Antibody cloning vectors

Recombinant antibodies were produced after insertion of the multimer-positive single cell amplified sequences into heavy or light (either kappa or lambda, respectively) vectors, as previously published in Tiller, et.al.

Figure E4: NGS analysis pipeline

The next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis pipeline for processing of raw Illumina MiSeq 2×250 reads is used to generate the heavy chain immunoglobulin sequences used for downstream analysis.

Figure E5: Representative results from NGS data analysis

The numbers of reads retained at each step of the analysis pipeline for one of the subjects' samples is shown.

Figure E6: Ara h 2 specific heavy chain clonal groups

The distribution of clonal groups (same V-J gene usage and similar CDR3) demonstrates that a subset (20%) have more than one sequence.

Figure E7: Inference of antigen selection of Arah2-positive B cell IgH

Heavy chain immunoglobulin sequences of Ara h 2 affinity selected B cells have increased frequency of CDR replacement mutations (RCDR) compared to the total number of mutations in the V region (MV), suggestive of antigen selection. The gray area represents the 90-95% confidence interval for the probability of random mutations.

Figure E8: Recombinant antibody affinity for Ara h 2

Ara h 2 affinity of the recombinant IgG1 antibodies produced from multimer-positive single cells was characterized using biolayer inferferometry (Octet). The colors of the bars reflect the original multimer-positive single cell isotype from which the recombinant antibody was produced.

Table E1: Comparison of observational controls and active arm before PNOIT

The frequency of multimer-positive B cells both within each B cell subset and within the entire B cell population were compared between subjects in the observational arm and the active arm before onset of PNOIT. No significant differences are found.

Table E2: Categorization of time in longitudinal model

Time period groups used in the longitudinal analysis are noted here with the number of observations (N) as well as the median, mean, minimum, and maximum number of weeks characterizing each time period.

Table E3: NGS sequences per sample

Within each of the six samples, with 2 time points during PNOIT of each of the three patients, the number of IgH sequences within each isotype are shown.

Table E4: Multimer selected sequence similarity to NGS repertoires

Each individual multimer-positive sequence with similar sequences in the NGS repertoire are listed, with both their originating subject and isotype, in each row. Columns reflect the NGS repertoires from different subjects by isotype compartment.

Table 1. Demographics of patients undergoing peanut oral immunotherapy.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total subjects | N=22 |

| Age at enrollment | 9 [7 - 15] |

| Gender | 7 female, 15 male |

| Skin prick wheal at baseline | 10.4 mm ± 6.1 mm |

| Skin prick flare at baseline | 25.0 mm ± 9.0 mm |

| Specific IgE to Ara h 2 at baseline | 113.2 kU/L (0.9-828) |

Key messages.

Ara h 2-specific circulating memory B cells are induced early and transiently in peanut oral immunotherapy and can be identified using a fluorescent multimer.

Immunoglobulins from these circulating Ara h 2-specific B cells are affinity matured.

Some clonal groups are shared among unrelated peanut allergic patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patients and their families for their participation and commitment to research. We thank Stephanie Kubala, Alicia Brennan, and Theodora Swenson for their contribution to these studies. We thank Brittany Anne Goods for her invaluable assistance with antibody cloning.

Funding: Research was supported by contracts with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID U19 AI087881, NIAID U19 AI095261), NIH grant 1S10RR023440-01A1, as well as supported in part by Koch Institute Support (core) grant P30-CA14051. Research is also by the Keck Foundation and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. S.U.P. supported by NIAID F32 AI104182 and 2013 AAAAI/Food Allergy Research & Education, Inc. Howard Gittis Memorial Research Award. J.C.L is a Camile Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar. Clinical studies supported in part by the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102, and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers.

Standard abbreviations

- PNOIT

Peanut oral immunotherapy

- BCR

B cell receptor

- NGS

next generation sequencing

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Burks AW, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the US determined by a random digit dial telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(4):559–62. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the United States determined by means of a random digit dial telephone survey: a 5-year follow-up study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(6):1203–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)02026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Kulis M, Steele PH, Kamilaris J, Berglund JP, et al. Sustained unresponsiveness to peanut in subjects who have completed peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2):468–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kemper A, Steele P, et al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim EH, Bird JA, Kulis M, Laubach S, Pons L, Shreffler W, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: clinical and immunologic evidence of desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):640–6 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thyagarajan A, Jones SM, Calatroni A, Pons L, Kulis M, Woo CS, et al. Evidence of pathway-specific basophil anergy induced by peanut oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(8):1197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones SM, Pons L, Roberts JL, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kulis M, et al. Clinical efficacy and immune regulation with peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(2):292–300. e1–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burks AW, Jones SM, Wood RA, Fleischer DM, Sicherer SH, Lindblad RW, et al. Oral immunotherapy for treatment of egg allergy in children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(3):233–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James LK, Bowen H, Calvert RA, Dodev TS, Shamji MH, Beavil AJ, et al. Allergen specificity of IgG(4)-expressing B cells in patients with grass pollen allergy undergoing immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3):663–70 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shamji MH, Durham SR. Mechanisms of immunotherapy to aeroallergens. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(9):1235–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooke RA, Barnard JH, Hebald S, Stull A. Serological Evidence of Immunity with Coexisting Sensitization in a Type of Human Allergy (Hay Fever) J Exp Med. 1935;62(6):733–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.62.6.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shamji MH, Ljorring C, Francis JN, Calderon MA, Larche M, Kimber I, et al. Functional rather than immunoreactive levels of IgG4 correlate closely with clinical response to grass pollen immunotherapy. Allergy. 2012;67(2):217–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wachholz PA, Soni NK, Till SJ, Durham SR. Inhibition of allergen-IgE binding to B cells by IgG antibodies after grass pollen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(5):915–22. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)02022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vickery BP, Lin J, Kulis M, Fu Z, Steele PH, Jones SM, et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy modifies IgE and IgG4 responses to major peanut allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(1):128–34. e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dang TD, Tang M, Choo S, Licciardi PV, Koplin JJ, Martin PE, et al. Increasing the accuracy of peanut allergy diagnosis by using Ara h 2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):1056–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klemans RJ, Otte D, Knol M, Knol EF, Meijer Y, Gmelig-Meyling FH, et al. The diagnostic value of specific IgE to Ara h 2 to predict peanut allergy in children is comparable to a validated and updated diagnostic prediction model. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(1):157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, Tsuiji M, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods. 2008;329(1-2):112–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Stollar BD. Human immunoglobulin variable region gene analysis by single cell RT-PCR. J Immunol Methods. 2000;244(1-2):217–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogunniyi AO, Thomas BA, Politano TJ, Varadarajan N, Landais E, Poignard P, et al. Profiling human antibody responses by integrated single-cell analysis. Vaccine. 2014;32(24):2866–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alamyar E, Duroux P, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. IMGT((R)) tools for the nucleotide analysis of immunoglobulin (IG) and T cell receptor (TR) V-(D)-J repertoires, polymorphisms, and IG mutations: IMGT/V-QUEST and IMGT/HighV-QUEST for NGS. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;882:569–604. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-842-9_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brochet X, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. IMGT/V-QUEST: the highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V-J and V-D-J sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W503–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giudicelli V, Brochet X, Lefranc MP. IMGT/V-QUEST: IMGT standardized analysis of the immunoglobulin (IG) and T cell receptor (TR) nucleotide sequences. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011(6):695–715. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogosch T, Kerzel S, Hoi KH, Zhang Z, Maier RF, Ippolito GC, et al. Immunoglobulin analysis tool: a novel tool for the analysis of human and mouse heavy and light chain transcripts. Front Immunol. 2012;3:176. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang N, He J, Weinstein JA, Penland L, Sasaki S, He XS, et al. Lineage structure of the human antibody repertoire in response to influenza vaccination. Science Transl Med. 2013;5(171):171ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lefranc MP. IMGT, the International ImMunoGeneTics Information System. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011(6):595–603. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V, Ginestoux C, Jabado-Michaloud J, Folch G, Bellahcene F, et al. IMGT, the international ImMunoGeneTics information system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D1006–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for StatisticalComputing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood SN. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krzywinski M, Schein J, Birol I, Connors J, Gascoyne R, Horsman D, et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009;19(9):1639–45. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van de Veen W, Stanic B, Yaman G, Wawrzyniak M, Sollner S, Akdis DG, et al. IgG4 production is confined to human IL-10-producing regulatory B cells that suppress antigen-specific immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(4):1204–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JH, Noh J, Noh G, Kim HS, Mun SH, Choi WS, et al. Allergen-specific B cell subset responses in cow's milk allergy of late eczematous reactions in atopic dermatitis. Cell Immunol. 2010;262(1):44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lanzavecchia A. Antigen uptake and accumulation in antigen-specific B cells. Immunol Rev. 1987;99:39–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newman J, Rice JS, Wang C, Harris SL, Diamond B. Identification of an antigen-specific B cell population. J Immunol Methods. 2003;272(1-2):177–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris L, Chen X, Alam M, Tomaras G, Zhang R, Marshall DJ, et al. Isolation of a human anti-HIV gp41 membrane proximal region neutralizing antibody by antigen-specific single B cell sorting. PloS One. 2011;6(9):e23532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franz B, May KF, Jr, Dranoff G, Wucherpfennig K. Ex vivo characterization and isolation of rare memory B cells with antigen tetramers. Blood. 2011;118(2):348–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia-Bates TM, Cordeiro MT, Nascimento EJ, Smith AP, Soares de Melo KM, McBurney SP, et al. Association between magnitude of the virus-specific plasmablast response and disease severity in dengue patients. J Immunol. 2013;190(1):80–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flinterman AE, Knol EF, Lencer DA, Bardina L, den Hartog Jager CF, Lin J, et al. Peanut epitopes for IgE and IgG4 in peanut-sensitized children in relation to severity of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(3):737–43 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shreffler WG, Lencer DA, Bardina L, Sampson HA. IgE and IgG4 epitope mapping by microarray immunoassay reveals the diversity of immune response to the peanut allergen, Ara h 2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(4):893–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frolich D, Giesecke C, Mei HE, Reiter K, Daridon C, Lipsky PE, et al. Secondary immunization generates clonally related antigen-specific plasma cells and memory B cells. J Immunol. 2010;185(5):3103–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parameswaran P, Liu Y, Roskin KM, Jackson KK, Dixit VP, Lee JY, et al. Convergent antibody signatures in human dengue. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13(6):691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson KJ, Liu Y, Roskin KM, Glanville J, Hoh RA, Seo K, et al. Human responses to influenza vaccination show seroconversion signatures and convergent antibody rearrangements. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(1):105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu X, Zhou T, Zhu J, Zhang B, Georgiev I, Wang C, et al. Focused evolution of HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies revealed by structures and deep sequencing. Science. 2011;333(6049):1593–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1207532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang N, Weinstein JA, Penland L, White RA, 3rd, Fisher DS, Quake SR. Determinism and stochasticity during maturation of the zebrafish antibody repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(13):5348–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014277108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glanville J, Kuo TC, von Budingen HC, Guey L, Berka J, Sundar PD, et al. Naive antibody gene-segment frequencies are heritable and unaltered by chronic lymphocyte ablation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(50):20066–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107498108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure E1: Frequency of multimer+ B cell subsets in allergic and non-allergic subjects

The frequency of multimer-positive cells was normalized to the subset (naïve, memory, or plasmablast) population and described as the number of cells per million subset cells or per million CD19+ B cells in either peanut allergic pateints from the PNOIT trial before the start of PNOIT compared to non-allergic control patients. Basophil staining of the non-allergic control patients is shown in Figure1c.

Figure E2: Single cell immunoglobulin amplification

Immunoglobulin amplification of heavy and light chains was performed using single cell, nested RT-PCR. In this example, gel electrophoresis demonstrates recovery of 17 out of 24 paired heavy and light chains.

Figure E3: Antibody cloning vectors

Recombinant antibodies were produced after insertion of the multimer-positive single cell amplified sequences into heavy or light (either kappa or lambda, respectively) vectors, as previously published in Tiller, et.al.

Figure E4: NGS analysis pipeline

The next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis pipeline for processing of raw Illumina MiSeq 2×250 reads is used to generate the heavy chain immunoglobulin sequences used for downstream analysis.

Figure E5: Representative results from NGS data analysis

The numbers of reads retained at each step of the analysis pipeline for one of the subjects' samples is shown.

Figure E6: Ara h 2 specific heavy chain clonal groups

The distribution of clonal groups (same V-J gene usage and similar CDR3) demonstrates that a subset (20%) have more than one sequence.

Figure E7: Inference of antigen selection of Arah2-positive B cell IgH

Heavy chain immunoglobulin sequences of Ara h 2 affinity selected B cells have increased frequency of CDR replacement mutations (RCDR) compared to the total number of mutations in the V region (MV), suggestive of antigen selection. The gray area represents the 90-95% confidence interval for the probability of random mutations.

Figure E8: Recombinant antibody affinity for Ara h 2

Ara h 2 affinity of the recombinant IgG1 antibodies produced from multimer-positive single cells was characterized using biolayer inferferometry (Octet). The colors of the bars reflect the original multimer-positive single cell isotype from which the recombinant antibody was produced.

Table E1: Comparison of observational controls and active arm before PNOIT

The frequency of multimer-positive B cells both within each B cell subset and within the entire B cell population were compared between subjects in the observational arm and the active arm before onset of PNOIT. No significant differences are found.

Table E2: Categorization of time in longitudinal model

Time period groups used in the longitudinal analysis are noted here with the number of observations (N) as well as the median, mean, minimum, and maximum number of weeks characterizing each time period.

Table E3: NGS sequences per sample

Within each of the six samples, with 2 time points during PNOIT of each of the three patients, the number of IgH sequences within each isotype are shown.

Table E4: Multimer selected sequence similarity to NGS repertoires

Each individual multimer-positive sequence with similar sequences in the NGS repertoire are listed, with both their originating subject and isotype, in each row. Columns reflect the NGS repertoires from different subjects by isotype compartment.