Abstract

Objectives

This study was undertaken to determine the mean peak filter resistance to airflow (Rfilter) encountered by subjects while wearing prototype filtering facepiece respirators (PRs) with low Rfilter during nasal and oral breathing at sedentary and low-moderate work rates.

Material and Methods

In-line pressure transducer measurements of mean Rfilter across PRs with nominal Rfilter of 29.4 Pa, 58.8 Pa and 88.2 Pa (measured at 85 l/min constant airflow) were obtained during nasal and oral breathing at sedentary and low-moderate work rates for 10 subjects.

Results

The mean Rfilter for the 29.4 PR was significantly lower than the other 2 PRs (p < 0.000), but there were no significant differences in mean Rfilter between the PRs with 58.8 and 88.2 Pa filter resistance (p > 0.05). The mean Rfilter was greater for oral versus nasal breathing and for exercise compared to sedentary activity (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Mean oral and nasal Rfilter for all 3 PRs was at, or below, the minimal threshold level for detection of inspiratory resistance (the 58.8–74.5 Pa/1×s−1), which may account for the previously-reported lack of significant subjective or physiological differences when wearing PRs with these low Rfilter. Lowering filtering facepiece respirator Rfilter below 88.2 Pa (measured at 85 l/min constant airflow) may not result in additional subjective or physiological benefit to the wearer.

Keywords: Respirator, Filter, Oral breathing, Nasal breathing

INTRODUCTION

Filtering facepiece respirators (FFRs) are the most commonly used respiratory protective devices in U.S. private industry and healthcare, and the class N95 FFR (essentially equivalent to the FF P2 class specified in European standard EN 149) is the single most used version [1]. The United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) N95 FFR certification testing (utilizing a filter tester at 85 l/min of constant airflow) specifies peak average inhalation and exhalation resistance to airflow (i.e., filter airflow resistance – Rfilter) limits of 35 mm (343.2 Pa) and 25 mm (245.1 Pa) H2O pressure, respectively, for this class of respirators [2]. Despite these relatively low Rfilter (defined as the pressure drop/flow rate) limits, complaints of difficulty breathing when wearing N95 FFRs have been reported by a sizeable number of healthcare workers [3–5].

Unfortunately, there are limited human data available with regard to actual Rfilter encountered across N95 FFR filters. Jones [6] reported that the peak average inhalation and exhalation ΔP of 1 early model FFR was related to work load and ranged 0–20 mm (0–196.1 Pa) H2O pressure in the subjects tested at rest and during mild, moderate and heavy workloads, but the route of breathing (i.e., nasal, oral, oronasal) was not identified. This investigation, part of a larger study and some of the results which have previously been reported [7], was undertaken by the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) of NIOSH and a respirator manufacturer (3M Company, St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.) to determine mean peak inhalation and exhalation Rfilter during oral and nasal breathing by subjects wearing a prototype FFR configured in 3 low filter resistances. These data could be of interest to researchers, manufacturers, standards development organizations, respiratory protection program managers, and end users.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Ten healthy, non-smoking subjects (7 men, 3 women) participated in this study, the majority of whom (8/10) were experienced N95 FFR users. Demographic mean values (± standard deviation) were: age − 24.5 years (±3.8), height −179 cm (±11), weight −75.3 kg (±12.4), and body mass index − 23.4 (±2.9). On the day of testing, the subjects underwent a screening history and physical examination by a hcensed physician. The subjects were dressed in athletic shorts or pants, tee shirts and athletic shoes during testing. The study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983, and were approved by the NIOSH Human Subjects Review Board, with all the subjects providing oral and written informed consent.

A cup-shaped, prototype FFR (PR) from 3M Company (St. Paul, MN, U.S.) was supplied to NPPTL in 3 different nominal Rfilter of 29.4 Pa, 58.8 Pa and 88.2 Pa at 85 1/min constant airflow (hereafter referred to as PR3, PR6, and PR9, respectively), achieved through modifications of the filter material. None of the PRs was equipped with an exhalation valve. Prior to the study trials, Rfilter were verified at NPPTL by testing with a TSI8130 automated filter tester (TSI, Shoreview, MN, U.S.), the same equipment utilized by 3M Company for its determination of the PR resistances. Results indicated Rfilter of 35.3 Pa, 63.7 Pa and 91.2 Pa for PR3, PR6 and PR9 at 85 1/min constant airflow, respectively. The subjects underwent standard U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) respirator quantitative fit testing exercises [8] for each of the PRs with the TSI Portacount®Pro+ Respirator Fit Tester Model 8038 (TSI, Shoreview, MN, U.S.), in the “plus” mode, that counts individual airborne particles to determine a quantitative estimate of respirator fit. The ratio of measured ambient particles to within-respirator particles is termed the “fit factor” and is, in part, a measure of the adequacy of the seal of the respirator to the face. In order to pass fit testing, the subjects had to achieve a score of ≥ 100, the passing score for an OSHA respirator quantitative fit test that is indicative of ≤ 1% entry of particles into the respirator wearer’s breathing zone [8]. All the subjects passed quantitative fit testing on each of the PRs. A Validyne (Northridge, CA, U.S.) Model DP45 low pressure transducer, calibrated to a water column, was connected to a centrally-placed metal grommet in the PRs via 1/8 inch internal diameter, flexible, plastic tubing (150 cm in length and supported by a stand midway between the transducer and the subject to prevent kinking) and collected Rfilter measurements at 10 samples-per-second.

The transducer measured sample Rfilter relative to ambient atmospheric pressure and the transducer’s output was converted to an electrical signal by a Validyne CD23 digital transducer connected to a computer with a dedicated LabView® data collection program (National Instruments Corporation, Austin, TX, U.S.). The Rfilter was recorded on LabView® as negative numbers for inhalation and positive numbers for exhalation and the reported Rfilter represents the average of the pressures during a breath. The subjects donned the individual PRs as per the manufacturer’s instructions, adjusted the pliable nose bar, performed negative and positive user seal checks to evaluate the seal of the respirator to the face [8], and underwent a 2 min acclimatization period to reach steady state [9].

The Rfilter measurements were then taken with the sedentary subjects standing and instructed to breathe only nasally for 30 s followed immediately by only oral breathing for 30 s. The subjects were then seated on a Kettler RX7 reclining bicycle ergometer (Ense-Parsit, Germany) and pedaled at a low-moderate work rate (50 watt resistance, 60 revolutions-per-minute) for 2 min to achieve stabilization of the respiratory rate and, with continued pedaling, were then instructed to breathe only nasally over a 30 s period followed immediately by only oral breathing for 30 s while Rfilter measurements were taken. This scenario was repeated for each of the 3 PRs, with a minimum 5 min respite between each of the trials.

Statistical analysis

Mean peak inhalation and exhalation Rfilter values, measured for 30 s, were separated and first averaged for statistical analysis, followed by the calculation of the group mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence interval (CI). Two-way ANOVA (3 resistance levels × 2 exercise states) was carried out for oral and nasal breathing to determine the main effect of the 3 filter resistances on the subjects’ Rfilter during sedentary activity and exercise. For a significant F value, post-hoc multiple comparisons for the observed means were subsequently performed with Sidak corrections for 95% confidence intervals. Mean peak inhalation and exhalation mean Rfilter comparisons between nasal and oral breathing were carried out by paired samples t-test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.19 (IBM, Somers, New York, U.S.).

RESULTS

Nasal breathing

The mean peak Rfilter of the PRs had a significant impact on the subjects’ Rfilter during nasal inhalation (F = 29.66, p < 0.001) and nasal exhalation (F = 11.01, p < 0.001). The mean peak Rfilter was greater during exercise trials than during sedentary activity for nasal inhalation (F = 25.77, p < 0.001) and nasal exhalation (F = 16.62, p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons (mean difference, CIs) of Rfilter during nasal inhalation were 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 58.8 Pa/l×s−1 (24.1, 15.2–32.8) and 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 88.2 Pa/l×s−1 (23.5, 14.7–32.2), and during nasal exhalation they were 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 58.8 Pa/l×s−1 (16.6, 7.0–26.3) and 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 88.2 Pa/l×s−1 (15.2, 5.58–24.9). Pair-wise comparisons of mean peak Rfilter during activity are Sedentary < Exercise (14.8, 8.9–20.5) for nasal inhalation and Sedentary < Exercise (13.0, 6.6–19.5) for nasal exhalation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean peak nasal and oral inhalation and exhalation airflow resistance (Rfilter) of prototype respirators (PR) at sedentary and low-moderate work rates

| Trial | Airflow resistance (Pa/l×s−1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sedentary standing | reclining bicycle exercise | |||

| M±SD | 95% CI | M±SD | 95% CI | |

| PR3Rfilter | ||||

| nasal inhalation | −11.6±5.5 | −7.6–15.5 | −22.6 ±8.1 | −16.8–28.5 |

| nasal exhalation | +4.9±6.4 | +2.7–9.5 | +14.8 ±19.8 | +6.1–28.9 |

| oral inhalation | −16.8±6.5 | −12.1–21.4 | −28.8 ±9.7 | −21.8–35.7 |

| oral exhalation | +9.2±6.3 | +4.7–13.8 | +19.6 ±10.2 | + 12.1–26.9 |

| PR6Rfilter | ||||

| nasal inhalation | −33.4±11.1 | −25.3–41.3 | −49.1 ±13.4 | −10.0–58.7 |

| nasal exhalation | + 19.9±7.5 | +14.6–25.3 | +33.0±14.3 | +22.8–3.3 |

| oral inhalation | −36.0±11.6 | −27.6–44.4 | −59.2 ±8.9 | −52.9–65.6 |

| oral exhalation | +24.3±9.3 | +17.5–30.9 | +43.5+11.4 | +35.4–51.7 |

| PR9 Rfilter | ||||

| nasal inhalation | −31.8±11.8 | −23.3–40.3 | −49.4 ±14.7 | −38.9–60.0 |

| nasal exhalation | + 16.9±7.4 | +11.5–22.3 | +33.1+13.2 | +23.6–12.6 |

| oral inhalation | −38.0±15.7 | −26.8–49.3 | −62.1 ±16.4 | −50.4–74.0 |

| oral exhalation | +26.5±11.3 | +18.4–34.7 | +48.9 ±17.7 | +36.1–61.5 |

M – mean; SD – standard deviation; CI – confidence interval.

Oral breathing

The mean peak Rfilter of the PRs had a significant impact on subjects’ Rfilter during oral inhalation (F = 31.28, p < 0.001) and oral exhalation (F = 23.23, p < 0.001). The mean peak Rfilter was greater during exercise trials than during sedentary activity for oral inhalation (F = 40.18, p < 0.001) and oral exhalation (F = 33.42, p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons (mean difference, CIs) of mean peak Rfilter during oral inhalation were 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 58.8 Pa/l×s−1 (24.8, 15.3–34.2) and 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 88.2 Pa (27.3, 17.9–36.7), and during oral exhalation they were 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 58.8 Pa/l×s−1 (19.5, 10.4–28.5) and 29.4 Pa/l×s−1 < 88.2 Pa/l×s−1 (23.3, 14.3–32.3). Pairwise comparisons of mean peak Rfilter during activity are Sedentary < Exercise (19.8,13.5–25.9) for oral inhalation and Sedentary < Exercise (17.3, 11.3–23.3) for oral exhalation (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

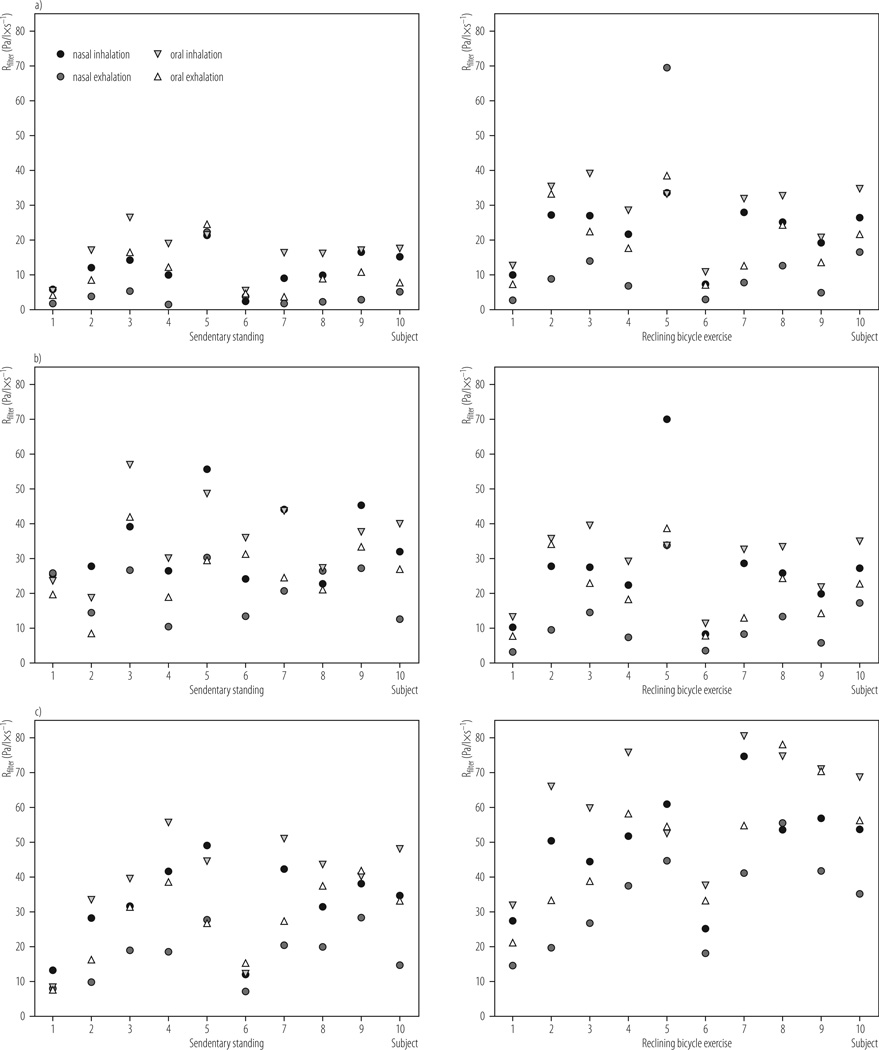

The mean peak Rfilter measurements in the current study represent the actual resistance to airflow through the filter material of the PRs during subject wear. The study data indicate that there were no significant differences in nasal and oral mean peak Rfilter when comparing PR6 and PR9 (Figure 1), whereas PR3 demonstrated significantly lower mean peak Rfilter compared with PR6 and PR9 (p < 0.000 for both comparisons) (Table 1; Figure 1 and Figure 2). Some inter-subject variability was noted and is represented in the width of the confidence intervals (Table 1) and visually in Figure 1. Nonetheless, our previously reported data from this study [7] showed that there were no significant differences in physiological (i.e., respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation, transcutaneous carbon dioxide) and subjective responses (i.e., exertion, thermal comfort, inspiratory effort, expiratory effort, overall breathing discomfort) among the 3 PRs during 1 h of treadmill exercise at a low-moderate work rate (5.6 km/h).

Fig. 1.

Mean peak oral and nasal inhalation and exhalation airflow filter resistance of prototype respirators (PR) at sedentary and low-moderate work rates: a) PR3, b) PR6, c) PR9

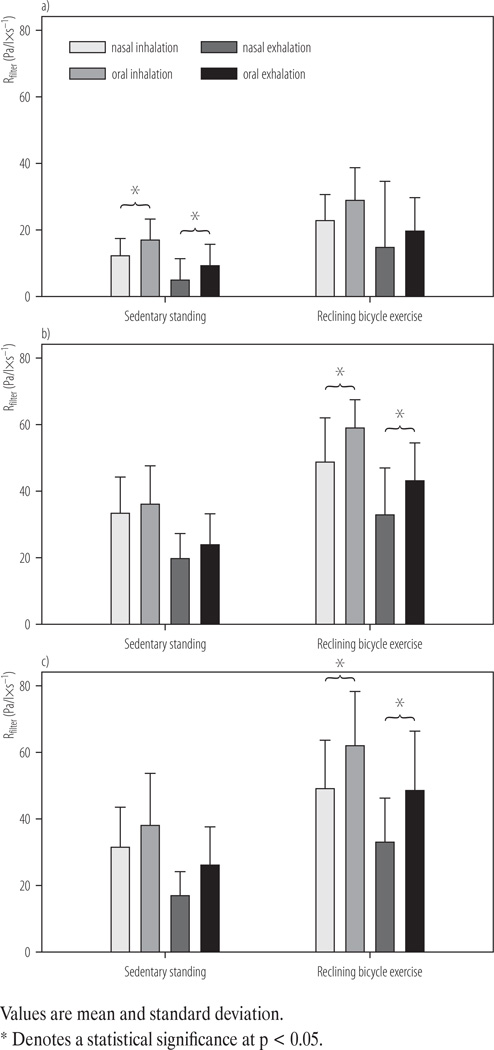

Fig. 2.

Differences in inhalation and exhalation filter airflow resistance at sedentary and low-moderate work rates for prototype respirators (PR): a) PR3, b) PR6, c) PR9

The reason for this lack of difference in these responses may be related to the fact that the 3 PRs had mean peak Rfilter (Table 1) that was at, or below, the 58.8–74.5 Pa/l×s−1 threshold level of detection for inspiratory resistance [10–15]. This suggests that the relatively common complaint by healthcare workers of difficulty breathing when wearing FFRs [3–5] with Rfilter similar to PR9 [16,17] are related to issues other than FFR-associated Rfilter.This further indicates that lower-ing Rfilter on FFRs below 88.2 Pa/l×s−1 may not be advantageous in terms of user physiological responses or subjective measures of comfort [7], parameters that are intimately connected to respirator compliance issues. The significantly higher mean peak Rfilter of low-moderate exercise compared with the sedentary state (Figure 2) when wearing a respirator, as reported in the current study, has been previously noted [18] and is a reflection of the increased airflow requirements of exercise.

The mean peak Rfilter during oral breathing was universally higher than during nasal breathing in the current study (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Although the oral airway is generally considered a lower resistance breathing route than the nasal airway, this is not necessarily always the case [19]. In research studies, airway pressures are frequently measured using either a mouthpiece or a mask (as in the current study), with the former being associated with lower pressures due to its creating a fairly wide opening of the mouth [19,20]. Also, the function of the bottom strap to ensure that the FFR is drawn down and over the jawbone [21] may result in restriction of jaw articulation leading to narrowing of the oral aperture that significantly affects the resistance of the oral route [18]. The same mechanism of respirator-related restriction in jaw articulation has also been postulated as the cause of speech impairment when wearing various respirator facemasks [22,23]. Additionally, during exercise, nasal resistance can fall due to sympathetic vasoconstriction of the nasal mucosa [24]. Lastly, the trajectory of the forces generated by the upper strap of FFRs is directed upward and outward at the malar (cheekbone) regions of the face [25], placing variable tension upon the paranasal facial skin that can increase the opening of the nasal valve and decrease nasal resistance (lateral traction on the paranasal facial skin is the basis of the Cottle test for evaluation of the nasal valve patency) [26]. The similarity in the mean peak Rfilter of PR6 and PR9 was an unexpected finding. The Rfilter across a filter fabric, such as N95 FFR filters, is airflow velocity dependent, as expressed in the following formula: ΔPf = K1V (where Kl = fabric resistance and V = airflow velocity) [27,28]. When humans experience mild-to-moderate inspiratory resistive loads (as with wearing an FFR), the main immediate neural mechanism for stabilizing their tidal volume is prolongation of the inspiratory portion of the breathing cycle at the expense of expiration, termed an increase in the duty cycle (ratio of total time of inspiration to total respiratory time) [29–32]. This increase in the duty cycle may have a role in minimizing the tension of respiratory muscles [9] and results in almost no change in minute ventilation [30].

We have previously reported that the respiratory rate, tidal volume and minute ventilation of the current study’s subjects at a low-moderate work rate (5.6 km/h) did not differ significantly while wearing the same 3 PRs [7]. Given that the Rfilter of filter fabrics is related to the air flow ve-locity [27], the similarity in inspiratory mean peak Rfilter of PR9 and PR6 indicates that the subjects wearing PR9 are sacrificing peak inspiratory airflow by prolonging the duty cycle to compensate for the greater mean peak Rfilter [33], a feature that may be imperceptible to the user. The similarity in exhalation mean peak Rfilter between the PR6 and PR9 may be related to the higher positive pressure generated during exhalation to overcome PR9 resistance that results in relatively greater disruption of the faceseal [34] and allows more exhaled air to follow the path of least resistance [35], thereby lowering mean peak Rfilter to the levels seen with PR6.

Prior research, using thermal imaging, showed that leakage at a single or multiple sites occurred during exhalation in majority of the study subjects wearing N95 FFRs during fit testing [36]. Thus, further study of human subjects to determine the impact of FFR Rfilter on faceseal leakage during exhalation may be warranted. Exhalation valve-equipped FFRs limit the buildup of positive pressure during exhalation [34], such that comparison of FFR with and without an exhalation valve might elucidate the contribution of leaks to exhalation ΔP

Interestingly, several of the study subjects conveyed that then molding of the deformable nose bar to the nasal contour was perceived as creating some nasal blockage and thereby promoting oronasal or oral breathing when the PRs were 1st donned. Previous research has indicated that respirators can distort the nasal alae [18], an area that accounts for the major contribution of nasal airway resistance [37], increasing the work of breathing and leading in a switch to oral or oronasal breathing [38]. Thus, if pliable nose bars cause nasal obstruction of any significant degree, it is possible that the nasal airway inhalation and exhalation mean peak Rfilter values we reported could have been artificially elevated. A human subject study comparing FFRs with and without nasal bars would be required to definitively answer this question. If phable nasal bars on FFRs are shown to affect nasal respiration, alternative design features to allow for conformity to the face without impingement (e.g., face seal adhesives, pre-molded nasal contours, etc.) might be an alternative, but this assumption requires further investigation. Additionally, given the current study findings of lower ΔP for nasal breathing and the additional physiological benefits ascribed to nasal breathing (e.g., decrease in water loss, lower FFR deadspace humidity, ah filtration, transport of nitric oxide to the lungs, etc.) [39], worker education in the proper use of FFRs might include information that the preferential route of breathing at low and moderate work rates is nasal, if tolerable.

Limitations of the current study include the relatively small number of participants (N = 10). However, the majority of the subjects (8/10) were experienced FFR users, thus offering some measure of confidence in the reliability of findings. We did not examine the impact of high workloads on the oral and nasal mean peak Rfilter; however, most current workers experience low and moderate work rates [40,41]. Also, none of the PRs was equipped with an exhalation valve that would likely have impacted exhalation measurements [34]. We tested only cup-shaped respirators and cannot comment on the impact of different respirator designs (e.g., duckbill, flat fold, etc.) on Rfilter. We tested only N95 FFR class respirators and cannot comment on Rfilter of classes with higher filter resistances. Lastly, we did not measure the rate or depth of breathing to assist in determining differences between nasal and oral breathing so that the reported mean peak Rfilter values could have been influenced either by functional filter resistance (pressure drop) or differences in airflow velocity.

CONCLUSIONS

Mean peak Rfilter during oral and nasal inhalation and exhalation was significantly lower for PR3 compared with PR6 and PR9 at sedentary and low-moderate work rates. However, mean peak Rfilter for all 3 PRs was at, or below, the threshold limit for detection of inspiratory resistance. The nasal route of breathing was associated with lower Rfilter at both work rates for the 3 PRs. The route of respiration (oral versus nasal) when wearing an FFR impacts Rfilter, and efforts to promote nasal breathing with the use of FFRs should be considered. Decreasing Rfilter of 95 FFRs below 88.2 Pa (measured at a constant airflow of 85 1/min) may not be of additional physiological or subjective benefit to the user [7].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Richard Vojtko for his assistance with the pressure transducer setup and measurements and also Andrew Palmiero, MS and Drs. William King, Aitor Coca, and W. Jon Williams of NPPTL and Andrew Viner, MS, of 3M Company, for their manuscript reviews and suggestions. Jung-Hyun Kim, Raymond J. Roberge, Jeffrey B. Powell, and Ronald Shaffer of the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory and Caroline M. Ylitao and John M. Sebastian of the 3M Company conducted the study, analyzed the results and prepared the manuscript.

This work was supported by internal operating funds of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), part of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Mention of any product name does not imply endorsement.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. [cited 2013 Feb 8];Respirator usage in private sector firms. 2001 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/respsurv.

- 2.Code of Federal Regulations (42 CFR 84.180) [cited 2013 May 16];Airflow resistance tests. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2007-title42-vol1/pdf/CFR-2007-title42-vol1-sec84-180.pdf.

- 3.Bryce E, Forrester L, Scharf S, Eshqhpour M. What do healthcare workers think? A survey of facial protection equipment user preferences. J Hosp Infect. 2007;68(3):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.12.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baig A, Knapp C, Eagan AE, Radonovich LJ., Jr Health care workers’ views about respirator use and features that should be included in the next generation of respirators. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(1):18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell R, Ogunremi T, Astrakianakis G, Bryce E, Gervais R, Gravel D, et al. Impact of the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic on Canadian health care workers: A survey on vaccination, illness, absenteeism, and person protective equipment. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(7):611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.01.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones JG. The physiological cost of wearing a disposable respirator. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1991;52(6):219–225. doi: 10.1080/15298669191364631. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15298669191364631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberge RJ, Kim J-H, Powell JB, Shaffer RE, Ylitalo CM, Sebastian JM. Impact of different breathing resistances on subjective and physiological responses to filtering facepiece respirators. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Occupational Safety and Health Administration. [cited 2013 Feb 11];Respiratory Protection Standard 1910.134. 1998 Available from: http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_id=12716&p_table=standards.

- 9.Nishino T, Kochi T. Breathing route and ventilator responses to inspiratory resistive loading in humans. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1994;150(3):742–746. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087346. http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman L, Lee G, Plotkin T, Sawyers LA, Yancey AR. Air flow measurement on human subjects with and without respiratory resistance at several work rates. Arch Ind Hyg Occup Med. 1951;3(5):61–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiley RL, Zechman FW., Jr Perception of added airflow resistance in humans. Resp Physiol. 1966;2(1):73–87. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(66)90039-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0034-5687(66)90039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottfried SB, Altose MD, Kelsen SG, Fogarty CM, Cher-niak NS. The perception of changes in airflow resistance in normal subjects and patients with chronic airways obstruction. Chest. 1978;73(2 Suppl):286–288. doi: 10.1378/chest.73.2_supplement.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell EJM, Gandevia SC, Killian KJ, Mahutte CK, Rigg JRA. Changes in the perception of inspiratory restive loads during partial curarization. J Physiol. 1980;309:93–100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Killian KJ, Mahutte CK, Howell JBL, Campbell EJM. Effect of timing, flow, lung volume, and threshold pressures on restive load detection. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49(6):958–963. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burki NK. Effects of added inspiratory loads on load detection thresholds. J Appl Physiol. 1981;50(1):162–164. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.50.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vojtko MR, Roberge MR, Vojtko RJ, Roberge RJ, Land-sittel DP. Effect on breathing resistance of a surgical mask worn over a N95 filtering facepiece respirator. J Intern Soc Resp Protect. 2008;25(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinkule EJ, Powell JB, Goss FL. Evaluation of N95 respirator use with a surgical mask cover: Effects on breathing resistance and inhaled carbon dioxide. Ann Occup Hyg. 2013;57:384–398. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mes068. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annhyg/mes068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harber PJ, Beck J, Luo J. Study of respirator effect on nasal-oral flow partition. Am J Ind Med. 1997;32(4):408–412. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199710)32:4<408::aid-ajim12>3.0.co;2-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199710)32:4%3C408::AID-AJIM12%3E3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amis TC, O’Neill N, Wheatley JR. Oral airway flow dynamics in healthy humans. J Physiol. 1999;515(Pt 1):293–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.293ad.x. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.293ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong LS, Johnson AT. Decrease of resistance to air flow with nasal strips as measured with the airflow perturbation device. Biomed Eng Online. 2004;3(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-3-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-925X-3-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yassi A, Bryce E, Moore D. [cited 2013 May 2];Protecting the faces of health care workers: Knowledge gaps and research priorities for effective protection against occupationally-acquired respiratory infectious diseases. Occupational Health and Safety Agency for Healthcare in British Columbia. 2004 Available from: https://circle.ubc.ca/bitstream/handle/2429/849/Protecting_Faces_Final_Report.pdf?sequence=1.

- 22.Lubker JF, Moll KL. Simultaneous oral-nasal air flow measurements and cinefluorographic observations during speech production. Proceedings of the American Speech and Hearing Association Convention. Chicago (IL). Iowa: University of Iowa; 1964. Nov, pp. 3–6. Available from: http://digital.library.pitt.edU/c/cleftpalate/pdf/e20986v02n3.06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wetherell A. [cited 2013 May 2];The UK general service respirator. Porton Down, Salisbury: Defence Scientific and Technical Laboratory. 2003 Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA452235.

- 24.Gehring JM, Garlick SR, Wheateley JR, Amis TC. Nasal resistance and flow resistive work of nasal breathing during exercise: Effects of a nasal dilator strip. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89(3):1114–1122. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.3.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niezgoda G, Benson SM, Eimer BC, Roberge RJ. Forces generated by N95 filtering facepiece respirator straps. J Intern Soc Resp Protect. 2013;30(2):31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tikanto J, Pirila T. Effects of the Cottle’s maneuver on the nasal valve as assessed by acoustic rhinometry. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(4):456–459. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3040. http://dx.doi.org/10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koehler JL, Leith D. Model calibration for pressure drop in a pulse-jet cleaned fabric filter. Atmos Environ. 1983;17(10):1909–1913. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(83)90348-7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newnum JD. The effects of relative humidity on respirator performance. University of Iowa, Iowa Research Online, Theses and Dissertations. 2010. [cited 2014 Mar 12]. Available: http://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2046&context=etd. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arad M, Heruti R, Shaham E, Atsmon J, Epstein Y. The effects of powered air supply to the respiratory protective device on respiration parameters during rest and exercise. Chest. 1992;102(6):1800–1804. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.6.1800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.102.6.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gozal D, Omidvar O, Kirlew KAT, Hathout GM, Hamilton R, Lufkin RB, et al. Identifcation of human brain regions underlying responses to resistive inspiratory loading with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92(14):6607–6611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6607. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.92.14.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bansal S, Harber P, Yun D, Liu D, Liu Y, Wu S, et al. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2009;6:221–227. doi: 10.1080/15459620902729218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15459620902729218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harber P, Shimozaki S, Barrett T, Fine G. Effect of exercise level on ventilator adaptation to respirator use. J Occup Med. 1990;32:1042–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hlavac MC, Catcheside PG, Adams A, Eckert DJ, McEvoy RD. The effects of hypoxia on load compensation during sustained incremental resistive loading in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103(1):234–239. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01618.2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01618.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberge RJ. Are exhalation valves on N95 filtering face-piece respirators benefcial at low-moderate work rates: An overview. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2012;9(11):617–623. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2012.715066. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15459624.2012.715066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CC, Willeke K. Characteristics of face seal leakage in filtering facepieces. Am Ind Hyg Assoc. 1992;53(9):533–539. doi: 10.1080/15298669291360120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15298669291360120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberge RJ, Monaghan WD, Palmiero AJ, Shaffer R, Bergman MS. Infrared imaging for leak detection of N95 filtering facepiece respirators: A pilot study. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(8):628–636. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20970. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNichols WT. The nose and OSA: Variable nasal obstruction may be more important in pathophysiology than fxed obstruction. Eur Resp J. 2008;32(1):3–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00050208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00050208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry PW, Mason NP, Richalet J-P. Nasal peak inspiratory fow at altitude. Eur Resp J. 2002;19(1):16–19. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00096902. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00096902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberge RJ, Kim J-H, Coca A. Protective facemask impact on human thermoregulation: An overview. Ann Occup Hyg. 2010;56(1):102–112. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/mer069. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/annhyg/mer069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harber P, Bansal S, Santiago S, Liu D, Yun D, Ng D, et al. Multidomain subjective response to respirator use during simulated work. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(1):38–45. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31817f458b. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e31817f458b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer JP, Hery M, Herrault J, Hubert G, Francois D, Hecht G, et al. Field study of subjective assessment of negative pressure half-masks Infuence of the work conditions on comfort and effciency. Appl Ergon. 1997;28(5-6):331–338. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(97)00007-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0003-6870(97)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]