Abstract

Objectives. We estimated the association between antiretroviral therapy (ART) uptake and HIV-related stigma at the population level in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods. We examined trends in HIV-related stigma and ART coverage in sub-Saharan Africa during 2003 to 2013 using longitudinal, population-based data on ART coverage from the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and on HIV-related stigma from the Demographic and Health Surveys and AIDS Indicator Surveys. We fitted 2 linear regression models with country fixed effects, with the percentage of men or women reporting HIV-related stigma as the dependent variable and the percentage of people living with HIV on ART as the explanatory variable.

Results. Eighteen countries in sub-Saharan Africa were included in our analysis. For each 1% increase in ART coverage, we observed a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of women (b = −0.226; P = .007; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −0.383, −0.070) and men (b = −0.281; P = .009; 95% CI = −0.480, −0.082) in the general population reporting HIV-related stigma.

Conclusions. An important benefit of ART scale-up may be the diminution of HIV-related stigma in the general population.

Recent evidence supporting the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for prevention of HIV transmission in low- and middle-income countries has raised hopes that the end of the HIV/AIDS epidemic is within reach.1 The success of this strategy hinges on early diagnosis and linkage to care for people living with HIV (PLHIV).2 However, people continue to present for treatment at late stages of disease3, and the stigma of HIV remains a major challenge. In the general population, stigmatizing beliefs are associated with reduced uptake of voluntary counseling and testing4,5 and increased sexual risk-taking behavior.6,7 When PLHIV internalize these beliefs, they may experience psychological distress and depression8,9 and are less likely to disclose their seropositivity to potential social supports.10,11 Internalized stigma, which is widespread among PLHIV in sub-Saharan Africa,12 is also an important public health issue because it compromises ART adherence.13,14 Consequently, efforts to counter stigma have been recognized as essential to HIV prevention and treatment.15,16

The extent to which ART scale-up itself is associated with reductions in HIV-related stigma has not been conclusively demonstrated. On one hand, it has been argued that ART does little to counter persistent blaming attitudes and feelings of moral outrage in the community; indeed, ART may be perceived as enabling PLHIV to appear healthy enough to engage in promiscuous behaviors and spread HIV.17–19 On the other hand, program implementers have argued that the increasing availability of effective treatment of PLHIV reduces the fear and stigma surrounding HIV in the general population20–22; these observations have been supported by studies in multiple African countries, including South Africa,23 Uganda,24,25 and Malawi.26 For example, in a population-based study conducted in Botswana, perceived access to ART was associated with markedly decreased odds of holding stigmatizing attitudes and of anticipated stigma.27 Although such findings may be explained in part by the community sensitization campaigns that generally accompany ART scale-up, improvements in physical health and HIV-related symptom burden may also reduce the extent to which PLHIV internalize stigmatizing beliefs25 and enable their economic rehabilitation and social reintegration,28,29 thereby weakening the symbolic and instrumental associations30 between HIV/AIDS and economic incapacity, social exclusion, and imminent death.24

Understanding the extent to which ART scale-up is associated with changes in stigma in the general population is important for policymakers given the relative absence of proven interventions that improve stigma on a national or regional scale.31–33 If ART scale-up is associated with reduced stigma in the general population, then expanding the availability of ART may itself spur a virtuous cycle of further improvements in ART uptake. Such a relationship would add to the impetus for strengthening ART delivery programs while identifying another much-needed intervention against HIV-related stigma. To help answer this question, we examined trends in stigma during ART scale-up in sub-Saharan Africa over the past decade, using longitudinal, country-level data on ART coverage from the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and on HIV-related stigma from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) and AIDS Indicator Surveys (AISs). Our primary aim was to understand the extent to which increased ART coverage in sub-Saharan Africa was associated with changes in HIV-related stigma in the general population.

METHODS

We focused our analysis on countries in sub-Saharan Africa during the period 2003 to 2013, given that this was a period of significant ART expansion promoted by the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria and the US President’s Plan for AIDS Relief.34,35 We extracted population-based data, measured at the country level, for the primary outcome of interest, HIV-related stigma, from published DHS and AIS reports.36 The DHS and AIS are nationally representative, population-based surveys conducted approximately every 5 years in more than 90 low- and middle-income countries worldwide. Standardization of DHS–AIS questions permits the analysis of trends in attitudes and behaviors within countries over time37 as well as comparative analyses across countries.38 Details of the DHS–AIS sampling procedures are included on the DHS Web site and in published country-level reports.36

We extracted country-level data on the primary exposure of interest, ART coverage, from the UNAIDS AIDSInfo online database.39 UNAIDS estimates HIV prevalence and incidence in countries using a modeling approach that incorporates annual antenatal clinic data and data from nationally representative population-based surveys that include blood testing.40,41 Data on the number of people receiving ART are reported by national HIV/AIDS control programs to the Global AIDS Response Progress Reporting system.

Measures

The DHS and AIS contain 4 questions pertaining to HIV-related stigma. Three measure stigmatizing attitudes: (1) “If a member of your family became sick with AIDS, would you be willing to care for her or him in your own household?” (2) “Would you buy fresh vegetables from a shopkeeper or vendor if you knew that this person had the AIDS virus?” and (3) “In your opinion, if a female teacher has the AIDS virus but is not sick, should she be allowed to continue teaching in the school?” Positive responses to these questions reflect expressions of social distance,42 often motivated by instrumental concerns about casual transmission or preoccupations with the symbolic meaning of HIV.30 The fourth question measures anticipated stigma: “If a member of your family got infected with the AIDS virus, would you want it to remain a secret or not?” Positive responses to this question reflect anticipated stigma,28 that is, the expectation of rejection if one’s stigmatized status is revealed to others.43

For each country-year observation, we calculated 2 composite indicators for HIV-related stigma, defined as the percentage of men and women aged 15 to 49 years in the country who responded positively to 1 or more of the HIV-related stigma questions, which is the standard presentation in DHS–AIS final country reports.36 We limited our analysis to countries with at least 2 available data sets during 2003 to 2013 in which this composite stigma variable was reported in the final DHS–AIS report. In the 1 instance in which a DHS and an AIS were conducted in the same year in the same country (Uganda, 2011), we elected to use data from the DHS. In a sensitivity analysis, we substituted data from the Uganda 2011 DHS with data from the Uganda 2011 AIS, and the resulting estimates remained unchanged.

The UNAIDS AIDSinfo database contains country-level data on the percentage of PLHIV on ART, which we defined as the total number of PLHIV on ART divided by the total number of PLHIV. We obtained these data for each country for the same years for which DHS or AIS data on HIV-related stigma were available. In cases in which a DHS report spanned 2 years (e.g., 2012–2013), we abstracted ART coverage data from the first year. Six countries had a DHS–AIS survey in 2003 (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Tanzania), but UNAIDS data on ART coverage were not available before 2004. For these countries, we matched the UNAIDS data from 2004 with the 2003 DHS–AIS.

Statistical Analysis

The resulting longitudinal data set consisted of country-year observations. We summarized differences in ART coverage and HIV-related stigma between the first and last year of available data for each country included in the analysis. For our primary model, we fitted linear regression models with country fixed effects, alternately specifying HIV-related stigma among men and women as the dependent variable and the percentage of PLHIV on ART as the explanatory variable. A statistically significant parameter estimate was interpreted as evidence of an association between ART coverage and stigma. The fixed effects specification is equivalent to including a dummy variable for each country, allowing us to adjust for all time-invariant confounding (whether observed or unobserved) at the country level. The “differencing” interpretation then permits an explicit assessment of how changes over time in ART coverage are associated with changes in HIV-related stigma, net of potential confounding from these time-invariant characteristics. In a sensitivity analysis, we also fitted models weighted by DHS–AIS sample size.

To account for potential changes in non–ART-related factors, we performed a secondary analysis with the addition of year as an explanatory variable in the regression model. To assess whether the association between ART coverage and stigma differed by region or HIV prevalence rates, we conducted stratified analyses by region and HIV prevalence. For the models stratified by region, we defined West Africa as including Senegal, Niger, Mali, Benin, Guinea, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast. We grouped East, Central, and Southern Africa into a single “other” category because of the small sample size. For the models stratified by high versus low baseline HIV prevalence, we used a threshold of 3.5%, which was the median baseline prevalence across the countries in our study sample. We used robust estimates of variance corrected for clustering within countries over time.44–47 All analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

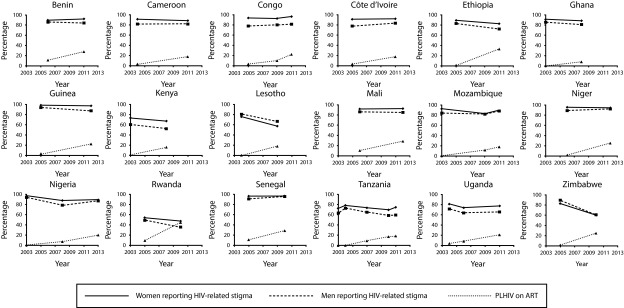

There were 21 countries with at least 2 DHSs–AISs conducted between 2003 and 2013. Of these 21 countries, we excluded 3 (Burkina Faso, Madagascar, and Mozambique) because the composite stigma variable was not included in at least 2 DHS–AIS reports. We analyzed data from the remaining 18 countries, comprising 43 total observations (Table 1, Figure 1). Most countries had data available from 2 DHS–AIS reports; 4 countries (22%) had 3, and Tanzania had 5. Survey refusal rates among men and women in the DHS–AIS were typically less than 10%, and no surveys had a refusal rate less than 20%. The median HIV prevalence in 2013 among the 18 countries was 2.8% (range = 0.4%–22.9%). The median rate of ART coverage at baseline among the 18 countries was 2.2% (range = 0.2%–11.4%). As expected, ART coverage from the first to the last year of observation increased in all 18 countries (median increase = 17.5 percentage points; range = 7.8–35.3 percentage points). At baseline, the median proportion of the general population reporting HIV-related stigma was 91.1% (range = 53.9%–98.3%) among women and 83.7% (range = 49.0%–93.8%) among men. In the last year of observation, the median proportion of the general population reporting HIV-related stigma was 88.4% (range = 47.0%–97.2%) among women and 81.4% (range = 35.6%–95.2%) among men.

TABLE 1—

Change Over Time in Percentage of People Living With HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy and HIV-Related Stigma in 18 Sub-Saharan African Countries: 2003–2013

| Country | HIV Prevalence,%, 2013a | First Year of Data | Last Year of Data | Absolute Change in Proportion of PLHIV on ART | Absolute Change in Proportion of Women Reporting Stigma | Absolute Change in Proportion of Men Reporting Stigma |

| Benin | 1.1 | 2006 | 2011 | 16.7 | 2.9 | −1.7 |

| Cameroon | 4.3 | 2004 | 2011 | 15.2 | −3.0 | 0.1 |

| Congo | 2.5 | 2005 | 2011 | 18.8 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Ivory Coast | 2.7 | 2005 | 2011 | 14.7 | 1.2 | 5.7 |

| Ethiopia | 1.2 | 2005 | 2011 | 31.8 | −6.4 | −10.9 |

| Ghana | 1.3 | 2003 | 2008 | 7.8 | −2.9 | −4.4 |

| Guinea | 1.7 | 2005 | 2012 | 20.2 | −1.1 | −6.3 |

| Kenya | 6.0 | 2003 | 2008 | 14.5 | −6.1 | −8.0 |

| Lesotho | 22.9 | 2004 | 2009 | 17.6 | −18.3 | −13.9 |

| Mali | 0.9 | 2006 | 2012 | 18.0 | 0.5 | −1.2 |

| Mozambique | 10.8 | 2003 | 2011 | 17.3 | −3.9 | 3.8 |

| Niger | 0.4 | 2006 | 2012 | 23.6 | −1.2 | 3.6 |

| Nigeria | 3.2 | 2003 | 2013 | 19.4 | −8.2 | −6.7 |

| Rwanda | 2.9 | 2005 | 2010 | 35.3 | −6.9 | −13.4 |

| Senegal | 0.5 | 2005 | 2010 | 17.4 | 0 | 4.5 |

| Tanzania | 5.0 | 2003 | 2011 | 18.6 | 1.8 | −3.7 |

| Uganda | 7.4 | 2004 | 2011 | 16.9 | −3.6 | −6.0 |

| Zimbabwe | 15.0 | 2005 | 2010 | 23.2 | −22.7 | −28.3 |

Note. ART = antiretroviral treatment; PLHIV = people living with HIV.

Source. Joint United Nations Program on AIDS (http://www.aidsinfoonline.org).

FIGURE 1—

Temporal trends in percentage of people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy and people reporting HIV-related stigma, by country: 2003–2013.

Note. ART = antiretroviral therapy; PLHIV = people living with HIV.

In our primary model, we estimated a statistically significant negative association between the proportion of PLHIV on ART and the percentage of the general population endorsing HIV-related stigma, among both women (b = −0.226; P = .007; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −0.383, −0.070) and men (b = −0.281; P = .009; 95% CI = −0.480, −0.082). These parameter estimates indicate that for each 10-percentage-point increase in ART coverage, we estimated a 2.3- to 2.8-percentage-point decrease in HIV stigma. Regression diagnostic procedures yielded no evidence of overly influential outliers in the models. The sensitivity analysis using models weighted by DHS–AIS sample size did not yield meaningfully different estimates for the parameter estimates on ART coverage.

In the secondary analysis, we did not find a statistically significant parameter estimate for the year variable when it was added to the models for either men or women. The magnitude of the parameter estimate for ART coverage remained essentially unchanged among women, albeit with decreased statistical significance (b = −0.245; P = .185; 95% CI = −0.620, 0.130), whereas the parameter estimate for ART coverage remained statistically significant among men (b = −0.484; P = .038; 95% CI = −0.937, −0.030).

We found important differences in the associations between ART coverage and stigma by HIV prevalence and region. Among the 9 countries with baseline HIV prevalence below the sample median, we found no statistically significant association between ART coverage and HIV-related stigma, either among women (b = −0.088; P = .131; 95% CI = −0.210, 0.033) or among men (b = −0.178; P = .105; 95% CI = −0.402, 0.046). By contrast, among the 9 countries with baseline HIV prevalence above the sample median, the magnitude of the negative association between ART coverage and HIV-related stigma was greater and statistically significant among both women (b = −0.426; P = .019; 95% CI = −0.760, −0.091) and men (b = −0.429; P = .047; 95% CI = −0.851, −0.008). These parameter estimates indicate that for each 10-percentage-point increase in ART coverage, we estimated a 4.3-percentage-point decrease in HIV stigma. In the analysis stratified by region, we estimated a statistically significant negative association between ART coverage and HIV-related stigma in Central, East, and Southern Africa (women, b = −0.317; P = .022; 95% CI = −0.574, −0.059; men, b = −0.429; P = .007; 95% CI = −0.702, −0.156) but not in the West African countries (women, b = −0.065; P = .282; 95% CI = −0.196, 0.065; men, b = −0.016; P = .858; 95% CI = −0.210, 0.179).

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal, cross-country analysis of population-based data from 18 countries, we observed a statistically significant association between increases in ART coverage and decreases in HIV-related stigma in the general population. Specifically, for each 10-percentage-point increase in ART coverage, there was a 2- to 3-percentage-point decrease in reported HIV-related stigma in the general population. When compared with the baseline standard deviation of HIV-related stigma across countries, these estimates represent approximately 0.2 standard deviation units. Although these effect sizes are relatively small, these changes could, as Rose48 classically argued, have substantial implications for population health, given the many negative downstream effects of HIV stigma.4–11,13,14 Thus, our findings suggest that an additional important benefit of ART scale-up may be the diminution of HIV-related stigma in the general population.

The addition of a calendar variable to the models did not yield a meaningful change in the magnitude of the parameter estimate for the ART coverage variable, although the statistical significance was decreased among women. In light of the fixed effects specification used in the models, this suggests that a portion of the decrease over time in HIV-related stigma was unrelated to ART scale-up, particularly among women. This is unsurprising, given the panoply of other stigma-reduction activities ongoing in many of the studied countries.31,49 More importantly, the persistent trends of decreasing stigma with increasing ART, despite adjustment for calendar time, reinforces our overall conclusion that an association exists between ART scale-up and decreasing population-level HIV-related stigma.

A mechanistic explanation for the observed association between ART scale-up and reduced HIV stigma has been suggested in several qualitative and epidemiological studies. This literature has shown that by enhancing the physical health of PLHIV and allowing for the subsequent reintegration of PLHIV as productive and contributing members of society, ART improves the perceived social value of PLHIV and removes the instrumental and symbolic association of HIV with economic incapacity25 and, thereby, the possibility of social death.50 The effects of ART on improving health, reversing economic incapacity, and reintegrating PLHIV into networks of mutual aid may ultimately outweigh instrumental concerns about casual transmission of HIV and the symbolic association of HIV with behaviors considered to be morally deviant.30 Niehaus,51 for example, argued that association with deviance is an insufficient explanation for persisting negative attitudes toward PLHIV. Furthermore, improvements in HIV-specific knowledge in the general population in sub-Saharan Africa (although levels of knowledge remain low overall)52 may render concerns about casual transmission less important over time.

The negative association between ART coverage and HIV-related stigma in the general population may differ by level of HIV prevalence and by region, as demonstrated in the stratified analyses. It has been argued that people in high-prevalence countries have more opportunities than people in low-prevalence countries to have personal contact with PLHIV, resulting in decreased fear, misunderstanding, and characterization of PLHIV as the “other.”53,54 Although the contact hypothesis formulated by Allport55 is one of the foremost theories of prejudice reduction,56 only recently have researchers demonstrated the persistence of attitude change through contact interventions.57,58 Our findings could be consistent with the contact hypothesis, given that the beneficial effects of increased ART coverage on stigma in the general population were most pronounced in countries with high HIV prevalence, where the impact of ART on improving health and reintegrating PLHIV into social and economic networks would be most evident.

The analyses stratified by region revealed a statistically significant negative association between ART coverage and reduced HIV-related stigma among both men and women in the 9 countries in Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa, but not in the 9 West African countries. This finding did not appear to be driven exclusively by differences in prevalence, because several low-prevalence countries outside of West Africa (e.g., Rwanda, Ethiopia) demonstrated decreases in stigma, whereas several high-prevalence countries in West Africa (e.g., Ivory Coast, Cameroon) did not. Because we are unaware of previous literature describing regional differences in stigma, the reasons for this finding remain unclear and warrant further investigation.

Furthermore, although the finding of an association between increasing ART coverage and improving HIV-related stigma may be reassuring, we emphasize that ART alone appears insufficient to reduce, let alone eliminate, stigma. Among the 18 countries in our analysis, approximately four fifths of respondents in the general population reported HIV-related stigma. Indeed, the lowest value for percentage of the general population reporting stigma was still 36%, which was reported by men in Rwanda in 2010, a country that was able to increase its ART coverage from 9% in 2005 to 45% in 2010. These findings parallel the recent study by Tsai,12 who demonstrated a persistently high level of internalized stigma among PLHIV throughout sub-Saharan Africa. We also found that HIV-related stigma in the general population appeared to be more prevalent among women than among men, perhaps reflecting gender differences in HIV-related knowledge, formal education, socioeconomic standing, and personal experiences with PLHIV.59 Thus, it remains evident that additional interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma—such as educational campaigns,31 changes to laws or policies that institutionalize stigma,14 and livelihood interventions24—will be needed and that such interventions may need to be tailored to reflect gender differences.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, these data are observational, not experimental, and the nature of the data sets available precluded us from being able to include in the models specific factors that might be considered potential confounders in the analysis. However, the fixed effects specification allows us to account for confounding factors that did not vary within countries in the short term of the study period. Second, our measures of stigmatizing attitudes and fears about disclosure, which are also used as core indicators by UNAIDS,60 are self-reports of hypothetical scenarios. Although the DHS–AIS stigma questions have been criticized on these grounds,61,62 this limitation would only bias our primary estimates (i.e., the association between changes in ART coverage and changes in stigma) if the extent to which study participants misinterpreted the survey questions systematically changed over time.

Third, although our results demonstrate an association between ART coverage and decreases in HIV-related stigma, it is conceivable that our findings may be explained in part by reverse causality—that is, in countries in which stigma was on the decline, governments may have had the political will to support and effectively implement ART scale-up. However, we believe it more likely that any stigma interventions were incorporated into ART scale-up itself, for example, community sensitization campaigns that accompanied the introduction of new ART programs. Regardless, evidence for an association is at least reassuring and further buttresses arguments for widespread ART scale-up in low- and middle-income countries. Fourth, our estimates of the association between ART coverage and stigma are susceptible to bias from error in the measurement of the explanatory variable, ART coverage. However, for this to meaningfully bias our estimates, the error would have to occur in such a way that estimates of ART coverage systematically differed in countries with or without population changes in stigma, which we believe is unlikely.

Conclusions

In this longitudinal, cross-country analysis of 18 countries in sub-Saharan Africa during 2003 to 2013, we found a statistically significant association between changes in ART coverage and improving HIV-related stigma in the general population. This association may be strongest in countries with high HIV prevalence and in countries outside of West Africa. Our findings suggest that another important benefit of ART scale-up in sub-Saharan Africa is its indirect effects on HIV-related stigma, which may, in turn, have important downstream benefits for HIV prevention and treatment. However, given that HIV-related stigmatizing attitudes remained highly prevalent in all of the countries under study despite ART expansion, further study on interventions that can be scaled up on a national or regional level to effectively target stigma is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the following additional sources of support: the National Institutes of Health (T32AI007433 [B. T. C.], K23MH096620 [A. C. T.], K23MH099916 [Siedner]), David Brudnoy Scholar Award (B. T. C.), and Harvard Catalyst The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award KL2 TR001100, an appointed KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award to B. T. C.).

This article was presented at the 22nd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; February 26, 2015; Seattle, WA.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, or the National Institutes of Health. The funding organizations have had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not necessary for this analysis of country-level data.

References

- 1.Sidibé M, Zuniga JM, Montaner J. Leveraging HIV treatment to end AIDS, stop new HIV infections, and avoid the cost of inaction. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(suppl 1):S3–S6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNairy ML, El-Sadr WM. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV transmission: what will it take? Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(7):1003–1011. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siedner MJ, Ng CK, Katz IT. Trends in CD4 count at presentation to care and treatment initiation in sub-Saharan Africa, 2002-2013: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(7):1120–1127. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly JD, Weiser SD, Tsai AC. Proximate context of HIV stigma and its association with HIV testing in Sierra Leone: a population-based study. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1035-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(6):442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA et al. AIDS-related stigma, HIV testing, and transmission risk among patrons of informal drinking places in Cape Town, South Africa. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(3):362–371. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delavande A, Sampaio M, Sood N. HIV-related social intolerance and risky sexual behavior in a high HIV prevalence environment. Soc Sci Med. 2014;111:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1823–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):2012–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norman A, Chopra M, Kadiyala S. Factors related to HIV disclosure in 2 South African communities. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1775–1781. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles SM et al. Internalized stigma, social distance, and disclosure of HIV seropositivity in rural Uganda. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(3):285–294. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9514-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai AC. Socioeconomic gradients in internalized stigma among 4,314 persons with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):270–282. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0993-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyer S, Clerc I, Bonono C-R, Marcellin F, Bilé P-C, Ventelou B. Non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment and unplanned treatment interruption among people living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon: individual and healthcare supply-related factors. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(8):1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 suppl 2):18640. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joint UN. Programme on AIDS. Key programmes to reduce stigma and discrimination and increase access to justice in national HIV responses. 2012. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/document/2012/Key_Human_Rights_Programmes_en_May2012.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2014.

- 16.Grossman CI, Stangl AL. Editorial: global action to reduce HIV stigma and discrimination. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 suppl 2):18881. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roura M, Urassa M, Busza J, Mbata D, Wringe A, Zaba B. Scaling up stigma? The effects of antiretroviral roll-out on stigma and HIV testing. Early evidence from rural Tanzania. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85(4):308–312. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maughan-Brown B. Stigma rises despite antiretroviral roll-out: a longitudinal analysis in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(3):368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ezekiel MJ, Talle A, Juma JM, Klepp K-I. “When in the body, it makes you look fat and HIV negative”: the constitution of antiretroviral therapy in local discourse among youth in Kahe, Tanzania. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(5):957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farmer P, Léandre F, Mukherjee JS et al. Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet. 2001;358(9279):404–409. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05550-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farmer P, Léandre F, Mukherjee J, Gupta R, Tarter L, Kim JY. Community-based treatment of advanced HIV disease: introducing DOT-HAART (directly observed therapy with highly active antiretroviral therapy) Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79(12):1145–1151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castro A, Farmer P. Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: from anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(1):53–59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.028563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mall S, Middelkoop K, Mark D, Wood R, Bekker L-G. Changing patterns in HIV/AIDS stigma and uptake of voluntary counselling and testing services: the results of two consecutive community surveys conducted in the Western Cape, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2013;25(2):194–201. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.689810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Weiser SD. Harnessing poverty alleviation to reduce the stigma of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11):e1001557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Bwana M et al. How does antiretroviral treatment attenuate the stigma of HIV? Evidence from a cohort study in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2725–2731. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0503-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baranov V, Bennett D, Kohler H-P. Hanover: New Hampshire; 2013. The indirect impact of antiretroviral therapy. Presented at: Northeast Universities Development Consortium Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfe WR, Weiser SD, Leiter K et al. The impact of universal access to antiretroviral therapy on HIV stigma in Botswana. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1865–1871. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell C, Skovdal M, Madanhire C, Mugurungi O, Gregson S, Nyamukapa C. “We, the AIDS people...”: how antiretroviral therapy enables Zimbabweans living with HIV/AIDS to cope with stigma. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1004–1010. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.202838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venkataramani AS, Thirumurthy H, Haberer JE et al. CD4+ cell count at antiretroviral therapy initiation and economic restoration in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2014;28(8):1221–1226. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pryor JB, Reeder GD, Vinacco R, Jr, Kott TL. The instrumental and symbolic functions of attitudes towards persons with AIDS. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1989;19(5):377–404. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stangl AL, Lloyd JK, Brady LM, Holland CE, Baral S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 suppl 2):18734. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coates TJ, Kulich M, Celentano DD et al. Effect of community-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV incidence and social and behavioural outcomes (NIMH Project Accept; HPTN 043): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(5):e267–e277. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70032-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jürgensen M, Sandøy IF, Michelo C, Fylkesnes K. ZAMACT Study Group. Effects of home-based voluntary counselling and testing on HIV-related stigma: findings from a cluster-randomized trial in Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;81:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in Africa: an evaluation of outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(10):688–695. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bendavid E, Holmes CB, Bhattacharya J, Miller G. HIV development assistance and adult mortality in Africa. JAMA. 2012;307(19):2060–2067. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demographic and Health Surveys Program. Available at: http://www.dhsprogram.com. Accessed September 8, 2014.

- 37.Chan BT, Weiser SD, Boum Y et al. Persistent HIV-related stigma in rural Uganda during a period of increasing HIV incidence despite treatment expansion. AIDS. 2015;29(1):83–90. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai AC, Subramanian SV. Proximate context of gender-unequal norms and women’s HIV risk in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2012;26(3):381–386. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834e1ccb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. AIDSinfo. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/datatools/aidsinfo. Accessed April 9, 2014.

- 40.Murray CJL, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):1005–1070. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60844-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. Methodology—understanding the HIV estimates. 2014. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_methodology_HIVestimates_en.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

- 42.Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. Am J Sociol. 1987;92(6):1461–1500. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52(1):96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers WH. Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Tech Bull. 1993;13(3):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams RL. A note on robust variance estimation for cluster-correlated data. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):645–646. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wooldridge JM. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Froot KA. Consistent covariance matrix estimation with cross-sectional dependence and heteroskedasticity in financial data. J Financ Quant Anal. 1989;24(3):333–355. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;282(6279):1847–1851. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. Reducing HIV stigma and discrimination: a critical part of national AIDS programmes: a resource for national stakeholders in the HIV response. 2008. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/pub/report/2008/jc1521_stigmatisation_en.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2014.

- 50.Egrot M. Renaître d’une mort sociale annoncée: recomposition du lien social des personnes vivant avec le VIH en Afrique de l’Ouest (Burkina Faso, Sénégal) Cult Sc. 2007;1:49–56. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niehaus I. Death before dying: understanding AIDS stigma in the South African lowveld. J South Afr Stud. 2007;33(4):845–860. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mishra V, Agrawal P, Alva S, Gu Y, Wang S. Changes in HIV-Related Knowledge and Behaviors in Sub-Saharan Africa. Calverton, MD: ICF Macro; 2009. DHS Comparative Reports No 24. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Genberg BL, Hlavka Z, Konda KA et al. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2279–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winskell K, Hill E, Obyerodhyambo O. Comparing HIV-related symbolic stigma in six African countries: social representations in young people’s narratives. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(8):1257–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allport GW. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paluck EL, Green DP. Prejudice reduction: what works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.LaCour MJ, Green DP. When contact changes minds: an experiment on transmission of support for gay equality. Science. 2014;346(6215):1366–1369. doi: 10.1126/science.1256151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90(5):751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mugoya GCT, Ernst K. Gender differences in HIV-related stigma in Kenya. AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):206–213. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. National AIDS programmes: a guide to monitoring and evaluation. 2000. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/me/pubnap/en. Accessed February 18, 2014.

- 61.Nyblade L, MacQuarrie K, Phillip F, Kwesigabo G, Mbwambo J, Ndega J. Washington, DC: US Agency for International Development; 2005. Measuring HIV stigma: results of a field test in Tanzania. Available at: http://www.icrw.org/files/publications/Working-Report-Measuring-HIV-Stigma-Results-of-a-Field-Test-in-Tanzania.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoder PS, Nyblade L. Comprehension of questions in the Tanzania AIDS Indicator Survey. 2004. Available at: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADC460.pdf. Accessed February 18, 2014.