Abstract

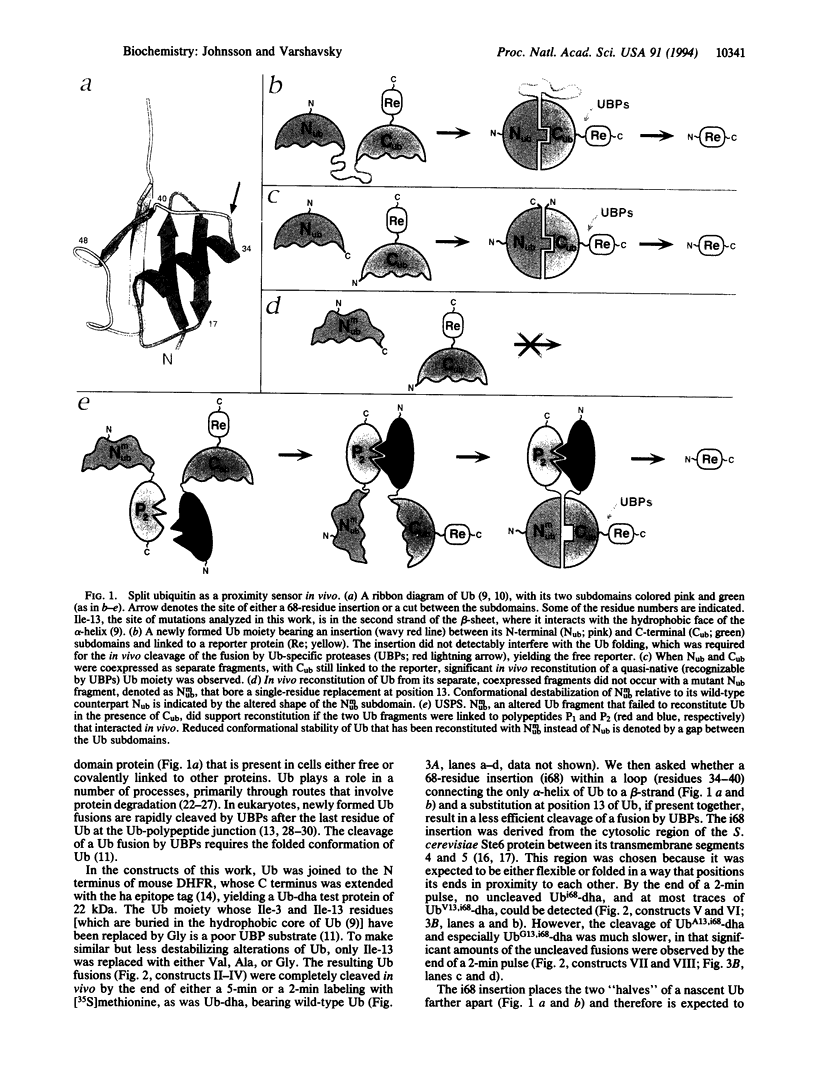

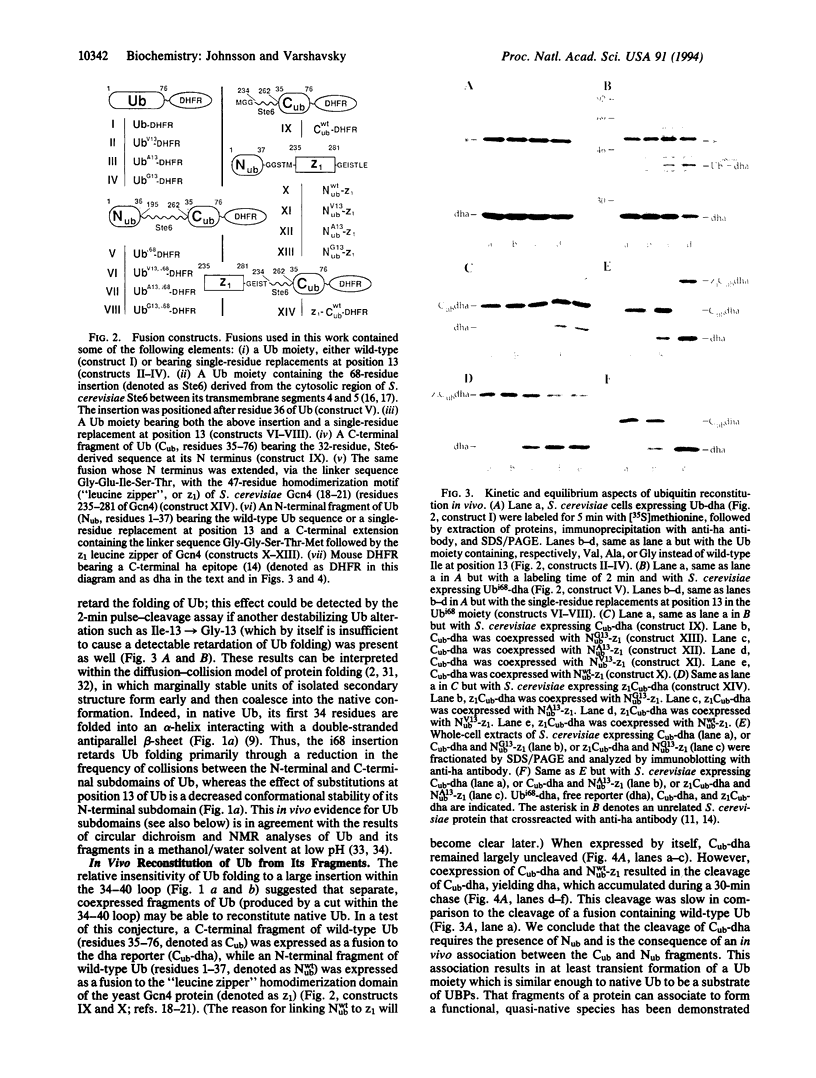

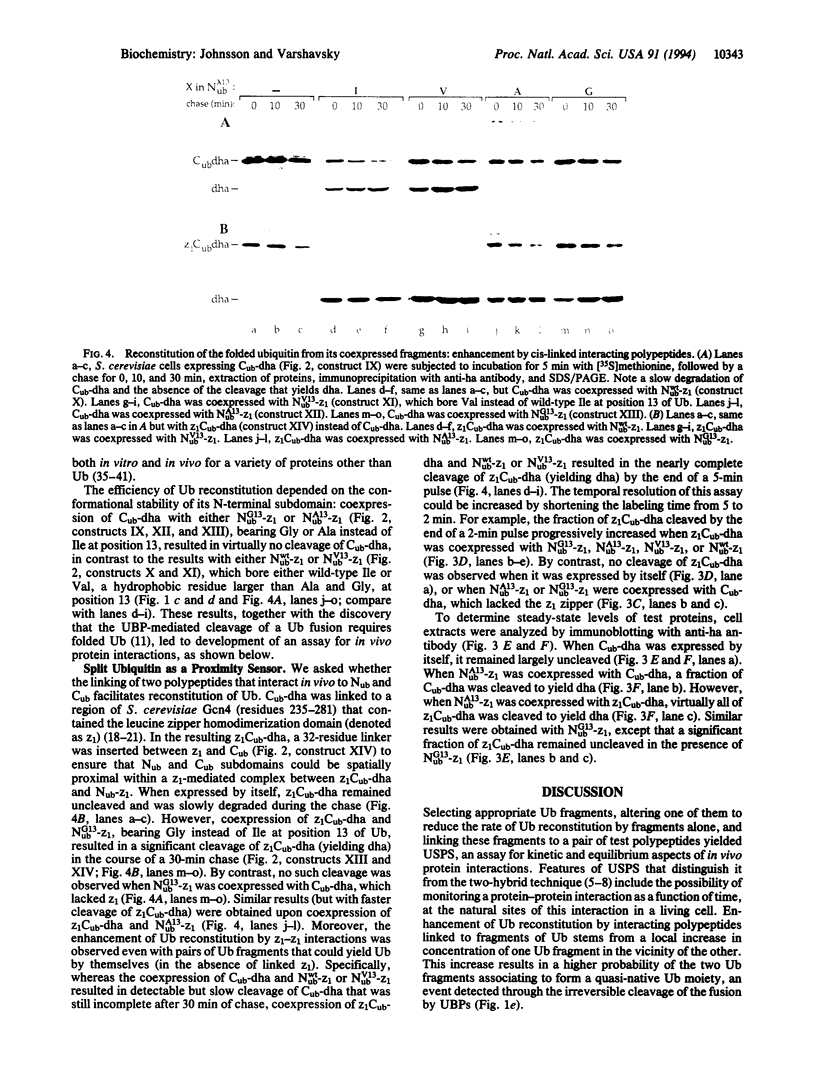

We describe an assay for in vivo protein interactions. Protein fusions containing ubiquitin, a 76-residue, single-domain protein, are rapidly cleaved in vivo by ubiquitin-specific proteases, which recognize the folded conformation of ubiquitin. When a C-terminal fragment of ubiquitin (C(ub)) is expressed as a fusion to a reporter protein, the fusion is cleaved only if an N-terminal fragment of ubiquitin (Nub) is also expressed in the same cell. This reconstitution of native ubiquitin from its fragments, detectable by the in vivo cleavage assay, is not observed with a mutationally altered Nub. However, if C(ub) and the altered Nub are each linked to polypeptides that interact in vivo, the cleavage of the fusion containing C(ub) is restored, yielding a generally applicable assay for kinetic and equilibrium aspects of in vivo protein interactions. This method, termed USPS (ubiquitin-based split-protein sensor), makes it possible to monitor a protein-protein interaction as a function of time, at the natural sites of this interaction in a living cell.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adams S. R., Harootunian A. T., Buechler Y. J., Taylor S. S., Tsien R. Y. Fluorescence ratio imaging of cyclic AMP in single cells. Nature. 1991 Feb 21;349(6311):694–697. doi: 10.1038/349694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B. M. The DNA enzymology of protein machines. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1984;49:1–12. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1984.049.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmair A., Finley D., Varshavsky A. In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue. Science. 1986 Oct 10;234(4773):179–186. doi: 10.1126/science.3018930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. T., Tobias J. W., Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin-specific proteases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cloning of UBP2 and UBP3, and functional analysis of the UBP gene family. J Biol Chem. 1992 Nov 15;267(32):23364–23375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien C. T., Bartel P. L., Sternglanz R., Fields S. The two-hybrid system: a method to identify and clone genes for proteins that interact with a protein of interest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Nov 1;88(21):9578–9582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. P., Evans P. A., Packman L. C., Williams D. H., Woolfson D. N. Dissecting the structure of a partially folded protein. Circular dichroism and nuclear magnetic resonance studies of peptides from ubiquitin. J Mol Biol. 1993 Nov 20;234(2):483–492. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies R. J., Schekman R. Structural and functional dissection of Sec62p, a membrane-bound component of the yeast endoplasmic reticulum protein import machinery. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Nov;10(11):6024–6035. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S., Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989 Jul 20;340(6230):245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D., Bartel B., Varshavsky A. The tails of ubiquitin precursors are ribosomal proteins whose fusion to ubiquitin facilitates ribosome biogenesis. Nature. 1989 Mar 30;338(6214):394–401. doi: 10.1038/338394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley D., Chau V. Ubiquitination. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1991;7:25–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.000325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galakatos N. G., Walsh C. T. Specific proteolysis of native alanine racemases from Salmonella typhimurium: identification of the cleavage site and characterization of the clipped two-domain proteins. Biochemistry. 1987 Dec 15;26(25):8475–8480. doi: 10.1021/bi00399a066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L. Strategies for the identification of interacting proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Mar 1;90(5):1639–1641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L. Synthetic enhancement in gene interaction: a genetic tool come of age. Trends Genet. 1993 Oct;9(10):362–366. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90042-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuris J., Golemis E., Chertkov H., Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993 Nov 19;75(4):791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system for protein degradation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:761–807. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch A. G. Evidence for translational regulation of the activator of general amino acid control in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Oct;81(20):6442–6446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin and intracellular protein degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992 Dec;4(6):1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90135-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch S. The ubiquitin-conjugation system. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:179–207. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E. S., Bartel B., Seufert W., Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin as a degradation signal. EMBO J. 1992 Feb;11(2):497–505. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05080.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson N., Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin-assisted dissection of protein transport across membranes. EMBO J. 1994 Jun 1;13(11):2686–2698. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson N., Weber K. Structural analysis of p36, a Ca2+/lipid-binding protein of the annexin family, by proteolysis and chemical fragmentation. Eur J Biochem. 1990 Feb 22;188(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus M., Weaver D. L. Protein-folding dynamics. Nature. 1976 Apr 1;260(5550):404–406. doi: 10.1038/260404a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P. S., Baldwin R. L. Specific intermediates in the folding reactions of small proteins and the mechanism of protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1982;51:459–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchler K., Sterne R. E., Thorner J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE6 gene product: a novel pathway for protein export in eukaryotic cells. EMBO J. 1989 Dec 20;8(13):3973–3984. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J. P., Varshavsky A. The yeast STE6 gene encodes a homologue of the mammalian multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein. Nature. 1989 Aug 3;340(6232):400–404. doi: 10.1038/340400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müsch A., Wiedmann M., Rapoport T. A. Yeast Sec proteins interact with polypeptides traversing the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Cell. 1992 Apr 17;69(2):343–352. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea E. K., Klemm J. D., Kim P. S., Alber T. X-ray structure of the GCN4 leucine zipper, a two-stranded, parallel coiled coil. Science. 1991 Oct 25;254(5031):539–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1948029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa F. R., Hochstrasser M. The yeast DOA4 gene encodes a deubiquitinating enzyme related to a product of the human tre-2 oncogene. Nature. 1993 Nov 25;366(6453):313–319. doi: 10.1038/366313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu W. T., Struhl K. Dimerization of leucine zippers analyzed by random selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993 Sep 11;21(18):4348–4355. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.18.4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechsteiner M. Natural substrates of the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway. Cell. 1991 Aug 23;66(4):615–618. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. A., Levy S. B. Tet protein domains interact productively to mediate tetracycline resistance when present on separate polypeptides. J Bacteriol. 1991 Jul;173(14):4503–4509. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4503-4509.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba K., Schimmel P. Functional assembly of a randomly cleaved protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Mar 1;89(5):1880–1884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989 May;122(1):19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockman B. J., Euvrard A., Scahill T. A. Heteronuclear three-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of a partially denatured protein: the A-state of human ubiquitin. J Biomol NMR. 1993 May;3(3):285–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00212515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshavsky A. The N-end rule. Cell. 1992 May 29;69(5):725–735. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90285-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay-Kumar S., Bugg C. E., Cook W. J. Structure of ubiquitin refined at 1.8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1987 Apr 5;194(3):531–544. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson C. R., Sigler P. B., McKnight S. L. Scissors-grip model for DNA recognition by a family of leucine zipper proteins. Science. 1989 Nov 17;246(4932):911–916. doi: 10.1126/science.2683088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]