Abstract

Background:

Guidelines recommend mediastinal lymph node sampling as the first invasive diagnostic procedure in patients with suspected lung cancer with mediastinal lymphadenopathy without distant metastases.

Methods:

Patients were a retrospective cohort of 15,316 patients with lung cancer with regional spread without metastatic disease in the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) or Texas Cancer Registry Medicare-linked databases. Patients were categorized based on the sequencing of invasive diagnostic tests performed: (1) evaluation consistent with guidelines, mediastinal sampling done first; (2) evaluation inconsistent with guidelines, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) present, mediastinal sampling performed but not as part of the first invasive test; (3) evaluation inconsistent with guidelines, NSCLC present, mediastinal sampling never done; and (4) evaluation inconsistent with guidelines, small cell lung cancer. The primary outcome was whether guideline-consistent care was delivered. Secondary outcomes included whether patients with NSCLC ever had mediastinal sampling and use of transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) among pulmonologists.

Results:

Only 21% of patients had a diagnostic evaluation consistent with guidelines. Only 56% of patients with NSCLC had mediastinal sampling prior to treatment. There was significant regional variability in guideline-consistent care (range, 12%-29%). Guideline-consistent care was associated with lower patient age, metropolitan areas, and if the physician ordering or performing the test was male, trained in the United States, had seen more patients with lung cancer, and was a pulmonologist or thoracic surgeon who had graduated more recently. More recent pulmonary graduates were also more likely to perform TBNA (P < .001).

Conclusions:

Guideline-consistent care varied regionally and was associated with physician-level factors, suggesting that a lack of effective physician training may be contributing to the quality gaps observed.

Current evidence-based guidelines recommend that patients with suspected lung cancer with mediastinal adenopathy by CT or PET imaging without evidence of distant metastatic disease undergo lymph node sampling to ensure accurate staging.1‐10 Accurate lymph node staging is important, because the status of the lymph nodes will determine whether the disease is surgically resectable. CT and PET imaging, although useful, do not always have sufficient positive and negative predictive value to guide treatment decisions in these cases.2,4,11 The result of relying solely on imaging to stage the mediastinum is that some patients will be falsely up-staged, leading to missed opportunities for surgery and possibly cure. Conversely, other patients will be falsely under-staged, leading to unnecessary thoracotomies and complications.2,4

However, previous studies have demonstrated that there are considerable differences between what is recommended in evidence-based guidelines and what is actually done.12‐17 Studies of the patterns of surgical care in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) found that mediastinoscopy is infrequently performed, and even then lymph nodes are biopsied in < 50% of cases.12,13 Alternative methods of mediastinal lymph node sampling, such as transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA), have been developed but are underused.14‐17 The net result is that mediastinal sampling is frequently not performed at all. In addition, in those patients in whom it is performed, it is often not performed as the first invasive diagnostic test, as recommended by guidelines, but rather it is only done after biopsies of peripheral lung masses have been performed.18 The consequence of improper test sequencing is additional and often unnecessary tests that, in turn, lead to increased costs and complications.

The question is, why do these detrimental practice patterns persist when there have been evidence-based guidelines in place for years? The goal of this study was to identify factors associated with guideline-consistent care. We hypothesized that system-level variables, such as physician specialty and training, are contributing to the persistent quality gaps observed.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis using the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and the Texas Cancer Registry (TCR). The registry data have been linked to Medicare claims and US 2000 Census data. We compared the registries and analyzed practice patterns and outcomes. This study was approved by institutional review board 4, and a waiver of informed consent was obtained. This dataset has been used to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of alternative staging strategies and presented in abstract form.19

Patient Population

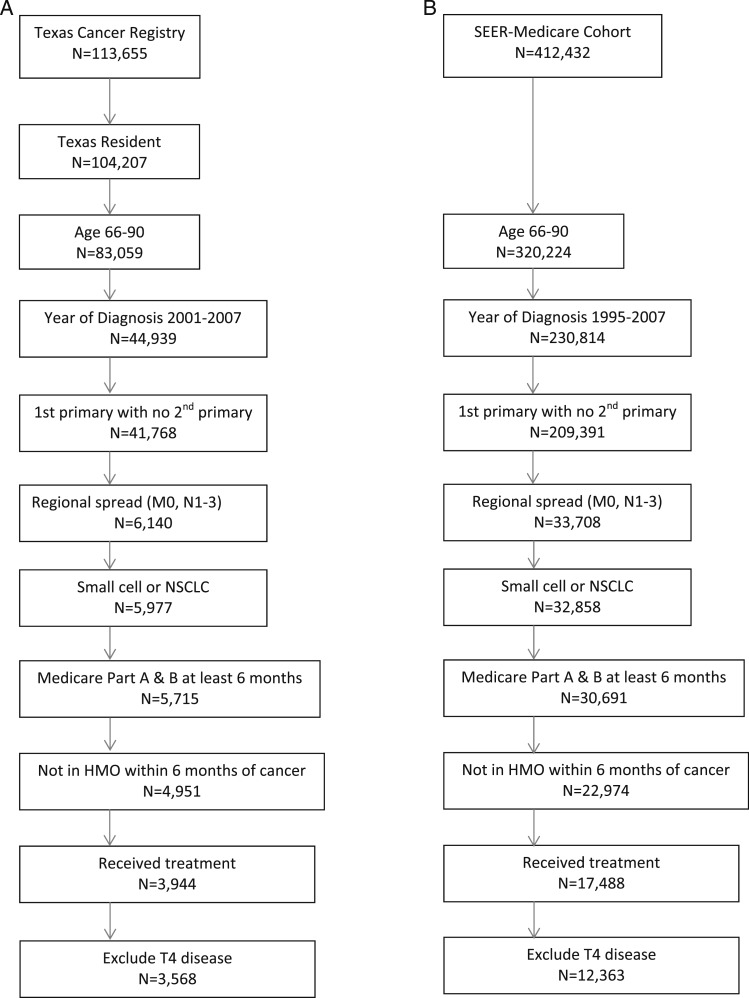

The population consisted of patients with lung cancer with regional spread to the hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes without distant metastases. The algorithms and search results are shown in Figure 1, and details are given in the online supplement (e-Table 1 (1.1MB, pdf) ).

Figure 1.

Study cohort selection results 1995 to 2007. A, Texas Cancer Registry. B, SEER. HMO = health maintenance organization; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Diagnostic Strategy and Guideline-Consistent Care

The invasive tests used and their sequencing were determined by checking Current Procedural Terminology and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes. Invasive tests were defined as CT scan-guided needle biopsy, bronchoscopy, endoscopy with ultrasound-guided needle aspiration, mediastinoscopy, or thoracotomy. Mediastinal sampling procedures were defined as bronchoscopy with TBNA or endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)-TBNA, endoscopy with ultrasound-guided needle aspiration, mediastinoscopy, thoracoscopy, or thoracotomy with mediastinal lymph node sampling.

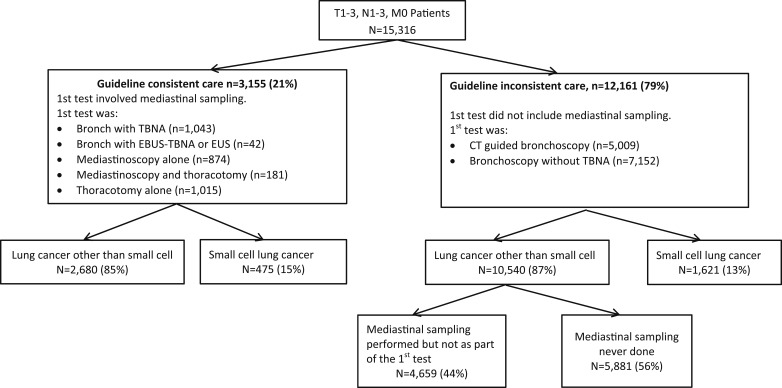

Patients were placed into categories based on their diagnostic testing sequence (Fig 2). Whether a patient received guideline-consistent care was determined by the first invasive test performed. If the first invasive test performed was one of the mediastinal sampling procedures listed here, then this was considered as guideline-consistent care.

Figure 2.

Practice patterns and diagnoses: SEER and Texas Cancer Registry 1995 to 2007. Diagram shows breakdown into guideline-consistent care vs guideline-inconsistent care, which was based on the first invasive test performed. Groups were subclassified based on tumor histology. Patients who had NSCLC were further subclassified based on whether mediastinal sampling was ever performed prior to treatment. EBUS = endobronchial ultrasound; EUS = endoscopic ultrasound; TBNA = transbronchial needle aspiration. See Figure 1 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

If the first invasive test did not involve mediastinal sampling (ie, the patient had CT scan-guided needle biopsy or bronchoscopy without TBNA) then this was considered as guideline-inconsistent care. These patients were further subclassified depending on tumor histology. Those who had NSCLC were divided into those who had mediastinal sampling performed but not as part of the first invasive test vs those who never had mediastinal sampling performed. Those who had small cell carcinoma were not further subdivided, since additional mediastinal sampling would not necessarily be required (Fig 2). See e-Appendix 1 (1.1MB, pdf) for additional details and rationale.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was whether the diagnostic workup was consistent with guidelines (N = 15,316). Secondary outcomes included whether mediastinal sampling was ever done in patients with NSCLC (n = 13,220). Secondary analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with TBNA use by pulmonologists and mediastinoscopy use by surgeons.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of patients and outcomes were compared using χ2 test for categorical variables. We used multilevel multivariable logistic regression with patients nested within physicians to identify factors associated with guideline-consistent care. We used backward selection with a P value ≤ .2 to enter the model and a P value ≤ .05 to stay in the model. Statistical analyses were performed at a significance level of .05. All data were analyzed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

SEER-Medicare and TCR-Medicare Cohort

In the SEER-Medicare linked dataset, 12,363 patients met the inclusion criteria. In the TCR-Medicare dataset, 3,568 met criteria (Fig 1). We compared the SEER and TCR registries patient characteristics, practice patterns, and lung cancer types (e-Table 2 (1.1MB, pdf) ). For subsequent analysis, we combined the two registries and controlled for geographic region. Patient characteristics for the combined cohort are shown in Table 1. Of the 15,931 patients, 615 (4%) had no Medicare data indicating that any diagnostic testing was performed. The remaining 15,316 patients (96%) constituted the final study cohort. Details on diagnostic test use, complications, and outcomes have been reported in more detail previously.

Table 1.

—Patient Characteristics

| Variables | Evaluation Consistent With Guidelines, Mediastinal Sampling Done First | Evaluation Inconsistent With Guidelines, NSCLC Present, Mediastinal Sampling Performed but Not as Part of the First Invasive Test | Evaluation Inconsistent With Guideline, NSCLC Present, Mediastinal Sampling Never Done | Evaluation Inconsistent With Guideline, Small Cell Present | No Evaluation Recordeda | Total |

| All subjects | 3,155 (100) | 4,659 (100) | 5,881 (100) | 1,621 (100) | 615 (100) | 15,931 (100) |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 66-70 | 1,074 (34.0) | 1,527 (32.8) | 1,549 (26.3) | 571 (35.2) | 196 (31.9) | 4,917 (30.9) |

| 71-75 | 995 (31.5) | 1,566 (33.6) | 1,697 (28.9) | 486 (30.0) | 169 (27.5) | 4,913 (30.8) |

| 76-80 | 761 (24.1) | 1,046 (22.5) | 1,521 (25.9) | 360 (22.2) | 143 (23.3) | 3,831 (24.1) |

| > 80 | 325 (10.3) | 520 (11.2) | 1,114 (18.9) | 204 (12.6) | 107 (17.4) | 2,270 (14.3) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1,530 (48.5) | 2,146 (46.1) | 2,637 (44.8) | 854 (52.7) | 254 (41.3) | 7,421 (46.6) |

| Male | 1,625 (51.5) | 2,513 (53.9) | 3,244 (55.2) | 767 (47.3) | 361 (58.7) | 8,510 (53.4) |

| Race | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2,745 (87.0) | 3,989 (85.6) | 4,826 (82.1) | 1,409 (86.9) | 490 (79.7) | 13,459 (84.5) |

| Hispanic | 129 (4.1) | 223 (4.8) | 289 (4.9) | 70 (4.3) | 34 (5.5) | 745 (4.7) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 199 (6.3) | 247 (5.3) | 548 (9.3) | 99 (6.1) | 66 (10.7) | 1,159 (7.3) |

| Non-Hispanic other | 82 (2.6) | 200 (4.3) | 218 (3.7) | 43 (2.7) | 25 (4.1) | 568 (3.6) |

| Urban/rural | ||||||

| Big metro | 1,763 (55.9) | 2,557 (54.9) | 3,092 (52.6) | 799 (49.3) | 320 (52.0) | 8,531 (53.6) |

| Metro | 861 (27.3) | 1,266 (27.2) | 1,625 (27.6) | 481 (29.7) | 181 (29.4) | 4,414 (27.7) |

| Urban | 196 (6.2) | 306 (6.6) | 431 (7.3) | 132 (8.1) | 39 (6.3) | 1,104 (6.9) |

| Less urban | 279 (8.8) | 433 (9.3) | 611 (10.4) | 171 (10.6) | 64 (10.4) | 1,558 (9.8) |

| Rural | 56 (1.8) | 97 (2.1) | 122 (2.1) | 38 (2.3) | 11 (1.8) | 324 (2.0) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1995 | 105 (3.3) | 181 (3.9) | 135 (2.3) | 45 (2.8) | 21 (3.4) | 487 (3.1) |

| 1996 | 88 (2.8) | 183 (3.9) | 150 (2.6) | 58 (3.6) | 21 (3.4) | 500 (3.1) |

| 1997 | 92 (2.9) | 178 (3.8) | 131 (2.2) | 51 (3.2) | 18 (2.9) | 470 (3.0) |

| 1998 | 89 (2.8) | 165 (3.5) | 152 (2.6) | 38 (2.3) | 15 (2.4) | 459 (2.9) |

| 1999 | 86 (2.7) | 131 (2.8) | 107 (1.8) | 48 (3.0) | 24 (3.9) | 396 (2.5) |

| 2000 | 207 (6.6) | 349 (7.5) | 338 (5.8) | 107 (6.6) | 40 (6.5) | 1041 (6.5) |

| 2001 | 335 (10.6) | 483 (10.4) | 636 (10.8) | 184 (11.4) | 63 (10.2) | 1,701 (10.7) |

| 2002 | 302 (9.6) | 516 (11.1) | 614 (10.4) | 191 (11.8) | 57 (9.3) | 1,680 (10.6) |

| 2003 | 377 (12.0) | 501 (10.8) | 716 (12.2) | 189 (11.7) | 69 (11.2) | 1,852 (11.6) |

| 2004 | 401 (12.7) | 497 (10.7) | 746 (12.7) | 197 (12.2) | 82 (13.3) | 1,923 (12.1) |

| 2005 | 344 (10.9) | 540 (11.6) | 742 (12.6) | 201 (12.4) | 65 (10.6) | 1,892 (11.9) |

| 2006 | 357 (11.3) | 484 (10.4) | 712 (12.1) | 155 (9.6) | 65 (10.6) | 1,773 (11.1) |

| 2007 | 372 (11.8) | 451 (9.7) | 702 (11.9) | 157 (9.7) | 75 (12.2) | 1,757 (11.0) |

| SEER/TCR region | ||||||

| Atlanta and rural Georgia | 68 (2.2) | 164 (3.5) | 218 (3.7) | 44 (2.7) | 14 (2.3) | 508 (3.2) |

| California | 640 (20.3) | 1,011 (21.7) | 1,122 (19.1) | 309 (19.1) | 134 (21.8) | 3,216 (20.2) |

| Connecticut | 239 (7.6) | 392 (8.4) | 327 (5.6) | 108 (6.7) | 53 (8.6) | 1,119 (7.0) |

| Detroit | 353 (11.2) | 387 (8.3) | 477 (8.1) | 115 (7.1) | 42 (6.8) | 1,374 (8.6) |

| Hawaii | 24 (0.8) | 68 (1.5) | 89 (1.5) | 13 (0.8) | 15 (2.4) | 209 (1.3) |

| Iowa | 175 (5.6) | 337 (7.2) | 408 (6.9) | 146 (9.0) | 33 (5.4) | 1,099 (6.9) |

| Kentucky | 209 (6.6) | 353 (7.6) | 475 (8.1) | 171 (10.6) | 37 (6.0) | 1,245 (7.8) |

| Louisiana | 98 (3.1) | 215 (4.6) | 454 (7.7) | 106 (6.5) | 36 (5.9) | 909 (5.7) |

| New Jersey | 395 (12.5) | 462 (9.9) | 576 (9.8) | 144 (8.9) | 64 (10.4) | 1,641 (10.3) |

| New Mexico | 49 (1.6) | 82 (1.8) | 80 (1.4) | 28 (1.7) | < 11 (< 2)b | < 250 (< 1.6) |

| Seattle | 146 (4.6) | 198 (4.3) | 217 (3.7) | 45 (2.8) | 38 (6.2) | 644 (4.0) |

| Texas | 720 (22.8) | 946 (20.3) | 1,393 (23.7) | 374 (23.1) | 135 (22.0) | 3,568 (22.4) |

| Utah | 39 (1.2) | 44 (0.9) | 45 (0.8) | 18 (1.1) | < 11 (< 1)b | < 157 (< 0.99) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||

| 0 | 1,620 (51.4) | 2,563 (55.0) | 2,740 (46.6) | 784 (48.4) | 332 (54.0) | 8,039 (50.5) |

| 1 | 959 (30.4) | 1,340 (28.8) | 1,800 (30.6) | 498 (30.7) | 148 (24.1) | 4,745 (29.8) |

| 2+ | 576 (18.3) | 756 (16.2) | 1,341 (22.8) | 339 (20.9) | 135 (22.0) | 3,147 (19.8) |

| % Poverty in patient’s census tractc | ||||||

| ≤ 4.76 | 886 (28.1) | 1,183 (25.4) | 1,316 (22.4) | 369 (22.8) | 145 (23.6) | 3,899 (24.5) |

| 4.77-9.07 | 742 (23.5) | 1,194 (25.6) | 1,401 (23.8) | 390 (24.1) | 136 (22.1) | 3,863 (24.3) |

| 9.08-16.53 | 779 (24.7) | 1,071 (23.0) | 1,461 (24.8) | 417 (25.7) | 155 (25.2) | 3,883 (24.4) |

| > 16.53 | 619 (19.6) | 997 (21.4) | 1,544 (26.3) | 391 (24.1) | 153 (24.9) | 3,704 (23.3) |

| Unknown | 129 (4.1) | 214 (4.6) | 159 (2.7) | 54 (3.3) | 26 (4.2) | 582 (3.7) |

| % With < 12 y educationd | ||||||

| ≤ 10.09 | 864 (27.4) | 1,239 (26.6) | 1,330 (22.6) | 336 (20.7) | 140 (22.8) | 3,909 (24.5) |

| 10.1-17.18 | 767 (24.3) | 1,157 (24.8) | 1,392 (23.7) | 413 (25.5) | 145 (23.6) | 3,874 (24.3) |

| 17.19-27.8 | 765 (24.3) | 1,040 (22.3) | 1,471 (25.0) | 417 (25.7) | 162 (26.3) | 3,855 (24.2) |

| > 27.85 | 630 (20.0) | 1,009 (21.7) | 1,529 (26.0) | 401 (24.7) | 142 (23.1) | 3,711 (23.3) |

| Unknown | 129 (4.1) | 214 (4.6) | 159 (2.7) | 54 (3.3) | 26 (4.2) | 582 (3.7) |

| Specialty of physician doing first teste | ||||||

| Internal medicine | 368 (11.7) | 1,040 (22.3) | 1,381 (23.5) | 375 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 3,164 (19.9) |

| Pulmonary | 945 (30.0) | 2,300 (49.4) | 2,998 (51.0) | 878 (54.2) | 0 (0) | 7,121 (44.7) |

| General surgery | 298 (9.5) | 196 (4.2) | 244 (4.2) | 74 (4.6) | 0 (0) | 812 (5.1) |

| Thoracic surgery | 1,431 (45.4) | 304 (6.5) | 292 (5.0) | 80 (4.9) | 0 (0) | 2,107 (13.2) |

| Other | 19 (0.6) | 141 (3.0) | 236 (4.0) | 46 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 442 (2.8) |

| Unknown | 94 (3.0) | 678 (14.6) | 730 (12.4) | 168 (10.4) | 615 (100) | 2,285 (14.3) |

| T stages | ||||||

| T1b | 908 (28.8) | 1,105 (23.7) | 869 (14.8) | 322 (19.9) | 133 (21.6) | 3,337 (20.9) |

| T2 | 1,342 (42.5) | 2,633 (56.5) | 2,993 (50.9) | 728 (44.9) | 243 (39.5) | 7,939 (49.8) |

| T3 | 176 (5.6) | 279 (6.0) | 762 (13.0) | 117 (7.2) | 74 (12.0) | 1,408 (8.8) |

| Unknown | 729 (23.1) | 642 (13.8) | 1,257 (21.4) | 454 (28.0) | 165 (26.8) | 3,247 (20.4) |

| Cancer type | ||||||

| NSCLC | 2,680 (85.0) | 4,659 (100) | 5,881 (100) | 0 (0) | 500 (81.3) | 13,720 (86.1) |

| Small cell | 475 (15.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1,621 (100) | 115 (18.7) | 2,211 (13.9) |

Data are presented as No. (%). NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; TCR = Texas Cancer Registry.

No testing recorded means that there are no Medicare payments noted. For example, a patient who had their care delivered through the Veterans Affairs would not show up in the Medicare dataset.

Strata with ≤ 10 patients were suppressed as per National Cancer Institute policy and are reported as “< 11” to ensure confidentiality. A total of 50 patients with T0 disease have been included in the T1 category to maintain confidentiality, because there were too few patients with T0 disease to report them separately while maintaining confidentiality.

% Poverty is the percentage of the population in the patient’s census tract living below the poverty level. Note that this does not mean the patient’s income is below the poverty line, just that they are living in a census tract with that level of poverty.

% With < 12 y education is the percentage of the population in the patient’s census tract that did not graduate high school.

Refers to the physician who ordered or performed the first invasive diagnostic test. For bronchoscopy and surgical procedures, this was the physician performing the procedure. For CT scan-guided biopsy, this was the referring physician. Internal medicine includes family practice and all subspecialties of internal medicine other than oncology and pulmonary medicine physicians. Surgery includes all other subspecialties of surgery other than thoracic or cardiothoracic surgery. Thoracic surgery and cardiothoracic surgery are included under thoracic surgery.

Practice Patterns

The most common first invasive diagnostic test was bronchoscopy without TBNA followed by CT scan-guided biopsy (Table 2). The breakdown of patients according to diagnostic strategy (guideline-consistent vs guideline-inconsistent) and type of lung cancer is shown in Figure 2. Only 21% of patients had a diagnostic evaluation performed in a manner consistent with guidelines. Among patients with NSCLC, 44% never had mediastinal sampling prior to treatment.

Table 2.

—Initial Invasive Testing Procedures Used in Patients With Lung Cancer With Regional Spread

| First Test Performed | Frequency | % | Cumulative Frequency | Cumulative % |

| Guideline-inconsistent care | ||||

| CT scan-guided biopsy | 5,009 | 32.7 | 5,009 | 32.7 |

| Bronchoscopy without TBNA | 7,152 | 46.7 | 12,161 | 79.4 |

| Guideline-consistent care | ||||

| Bronchoscopy with TBNA | 1,043 | 6.8 | 13,204 | 86.2 |

| Bronchoscopy with TBNA + EBUS or EUSa | 42 | 0.3 | 13,246 | 86.5 |

| Mediastinoscopy alone | 874 | 5.7 | 14,120 | 92.2 |

| Mediastinoscopy and thoracotomy | 181 | 1.2 | 14,301 | 93.4 |

| Thoracotomy alone | 1,015 | 6.6 | 15,316 | 100 |

EBUS = endobronchial ultrasound; EUS = endoscopic ultrasound; TBNA = transbronchial needle aspiration.

Strata with ≤ 10 patients were suppressed as per National Cancer Institute policy and are reported as “ < 11” to ensure confidentiality. Endoscopy with ultrasound was done in < 11 patients and was, therefore, included in the bronchoscopy with TBNA + EBUS category to protect patient confidentiality.

The characteristics of the physicians ordering or performing invasive diagnostic tests are shown in Table 3. Most patients had their first invasive test ordered by internists or pulmonologists. There was significant regional variability in guideline-consistent care (range, 12%-29%). On multivariate analysis, the probability of guideline-consistent care was associated with patient age < 76 years, geographic region, not being in a big metropolitan area, lower poverty levels, lower T stage, physician specialty, and physicians who were men and trained in the United States (Table 4). Guideline-consistent care was also more likely if the physician saw a higher number of patients with lung cancer in the registry. Recent graduates in pulmonary and thoracic surgery were more likely to deliver guideline-consistent care than older graduates. However, there was no association between graduation year and probability of guideline-consistent care for other disciplines (Table 5) (Mantel-Haenszel P < .0001). When we restricted our analysis to SEER data from 2004 to 2007, so that current nodal staging information was available, the results were similar (e-Table 3 (1.1MB, pdf) ).

Table 3.

—Characteristics of Physicians Ordering or Performing Invasive Diagnostic Tests

| First Invasive Test | Any Invasive Test | |||

| Characteristics | No. | % | No. | % |

| No. of physicians | 6,325 | 100 | 8,037 | 100 |

| Physician sex | ||||

| Male | 4,753 | 75.2 | 5,934 | 73.8 |

| Female | 491 | 7.8 | 618 | 7.7 |

| Unknown | 1,081 | 17.1 | 1,485 | 18.5 |

| Decade of graduation | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 2,376 | 37.6 | 3,018 | 37.6 |

| 1980-1989 | 1,899 | 30.0 | 2,331 | 29.0 |

| 1990+ | 969 | 15.3 | 1,203 | 15.0 |

| Unknown | 1,081 | 17.1 | 1,485 | 18.5 |

| Trained in the United States | ||||

| Yes | 4,050 | 64.0 | 5,058 | 62.9 |

| No | 1,342 | 21.2 | 1,676 | 20.9 |

| Unknown | 933 | 14.8 | 1,303 | 16.2 |

| Degree | ||||

| MD | 5,160 | 81.6 | 6,452 | 80.3 |

| DO | 232 | 3.7 | 282 | 3.5 |

| Unknown | 933 | 14.8 | 1,303 | 16.2 |

| Specialtya | ||||

| Internal medicinea | 1,903 | 30.1 | 2,309 | 28.7 |

| Surgery | 596 | 9.4 | 1,031 | 12.8 |

| Oncology | 244 | 3.9 | 368 | 4.6 |

| Pulmonary | 2,027 | 32.1 | 2,109 | 26.2 |

| Other | 144 | 2.3 | 218 | 2.7 |

| Thoracic surgery | 669 | 10.6 | 1,006 | 12.5 |

| Unknown | 742 | 11.7 | 996 | 12.4 |

| No. of patients | ||||

| 1 | 3,759 | 59.4 | 4,590 | 57.1 |

| 2-5 | 1,769 | 28.0 | 2,257 | 28.1 |

| 6-10 | 564 | 8.9 | 754 | 9.4 |

| > 10 | 233 | 3.7 | 436 | 5.4 |

Refers to the physician who ordered or performed the invasive diagnostic test. For bronchoscopy and surgical procedures, this was the physician performing the procedure. For CT scan-guided biopsy, this was the referring physician. Internal medicine includes family practice and all subspecialties of internal medicine other than oncology and pulmonary. Surgery includes all subspecialties of surgery other than thoracic or cardiothoracic surgery. Thoracic surgery and cardiothoracic surgery are included under thoracic surgery.

Table 4.

—Factors Associated With Guideline-Consistent Care

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

| Variables | Patients Receiving Guideline-Consistent Care, % | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Patient age, y | |||||

| 66-70 | 22.6 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 71-75 | 20.7 | 0.90 (0.81-0.99) | .03 | 0.93 (0.83-1.03) | .17 |

| 76-80 | 20.5 | 0.89 (0.80-0.99) | .03 | 0.86 (0.77-0.96) | .008 |

| > 80 | 15.0 | 0.61 (0.53-0.70) | < .0001 | 0.63 (0.55-0.74) | < .0001 |

| Patient sex | |||||

| Male | 20.6 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Female | 22.3 | 1.10 (1.02-1.19) | .02 | … | … |

| Patient race | |||||

| White | 21.9 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Hispanic | 19.3 | 0.85 (0.70-1.04) | .11 | … | … |

| Black | 19.0 | 0.84 (0.71-0.98) | .03 | … | … |

| Other | 16.0 | 0.68 (0.53-0.86) | .002 | … | … |

| Urban/rural | |||||

| Big metro | 22.4 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Metro | 21.2 | 0.93 (0.84-1.02) | .11 | 1.28 (1.1-1.49) | .001 |

| Urban | 19.4 | 0.83 (0.71-0.98) | .03 | 1.11 (0.89-1.39) | .36 |

| Less urban | 19.2 | 0.82 (0.71-0.95) | .008 | 1.12 (0.90-1.38) | .31 |

| Rural | 18.2 | 0.77 (0.57-1.04) | .09 | 1.12 (0.79-1.59) | .51 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 1995 | 22.6 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 1996 | 18.7 | 0.79 (0.57-1.09) | .15 | … | … |

| 1997 | 21.3 | 0.93 (0.67-1.27) | .63 | … | … |

| 1998 | 20.8 | 0.90 (0.65-1.24) | .51 | … | … |

| 1999 | 23.3 | 1.04 (0.75-1.45) | .80 | … | … |

| 2000 | 21.2 | 0.92 (0.70-1.20) | .54 | … | … |

| 2001 | 21.5 | 0.94 (0.73-1.21) | .62 | … | … |

| 2002 | 18.9 | 0.80 (0.62-1.03) | .08 | … | … |

| 2003 | 22.1 | 0.97 (0.76-1.25) | .83 | … | … |

| 2004 | 22.7 | 1.01 (0.79-1.29) | .95 | … | … |

| 2005 | 19.8 | 0.84 (0.66-1.08) | .18 | … | … |

| 2006 | 21.8 | 0.95 (0.74-1.22) | .71 | … | … |

| 2007 | 23.3 | 1.04 (0.81-1.33) | .76 | … | … |

| SEER/TCR region | |||||

| California | 22.0 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Atlanta and rural Georgia | 14.8 | 0.62 (0.47-0.81) | .0005 | 0.68 (0.47-0.99) | .04 |

| Connecticut | 23.2 | 1.07 (0.91-1.27) | .42 | 0.83 (0.64-1.08) | .17 |

| Detroit | 27.8 | 1.37 (1.18-1.59) | < .0001 | 1.04 (0.78-1.37) | .80 |

| Hawaii | 12.4 | 0.51 (0.33-0.78) | .002 | 0.48 (0.26-0.87) | .02 |

| Iowa | 16.7 | 0.71 (0.59-0.86) | .0003 | 1.15 (0.86-1.54) | .36 |

| Kentucky | 17.8 | 0.77 (0.65-0.92) | .003 | 0.64 (0.48-0.86) | .003 |

| Louisiana | 11.7 | 0.47 (0.37-0.59) | < .0001 | 0.64 (0.47-0.86) | .004 |

| New Jersey | 26.3 | 1.27 (1.10-1.47) | .001 | 1.14 (0.91-1.43) | .25 |

| New Mexico | 22.2 | 1.02 (0.73-1.42) | .93 | 1.16 (0.72-1.85) | .54 |

| Seattle | 24.6 | 1.16 (0.94-1.42) | .17 | 1.42 (1.06-1.90) | .02 |

| Texas | 21.4 | 0.97 (0.86-1.09) | .58 | 1.22 (1.00-1.48) | .048 |

| Utah | 28.9 | 1.44 (0.99-2.12) | .06 | 2.18 (1.33-3.57) | .002 |

| % Povertya | |||||

| ≤ 4.76 | 24.7 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 4.77-9.07 | 20.7 | 0.80 (0.71-0.89) | < .0001 | 0.83 (0.74-0.93) | .002 |

| 9.08-16.53 | 21.6 | 0.84 (0.75-0.94) | .002 | 0.93 (0.81-1.06) | .27 |

| > 16.53 | 18.2 | 0.68 (0.60-0.76) | < .0001 | 0.81 (0.71-0.94) | .004 |

| Unknown | 23.4 | 0.94 (0.76-1.16) | .54 | 1.16 (0.63-2.11) | .64 |

| % Non-high schoolb | |||||

| ≤ 10.09 | 23.9 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 10.1-17.18 | 21.3 | 0.87 (0.77-0.97) | .01 | … | … |

| 17.19-27.8 | 21.6 | 0.88 (0.79-0.98) | .02 | … | … |

| > 27.85 | 18.3 | 0.72 (0.64-0.81) | < .0001 | … | … |

| Unknown | 23.4 | 0.98 (0.79-1.21) | .83 | … | … |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| 0 | 21.8 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 1 | 21.7 | 0.99 (0.90-1.09) | .84 | … | … |

| 2+ | 19.8 | 0.88 (0.79-0.99) | .03 | … | … |

| T stages | |||||

| T1 (include T0) | 29.7 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| T2 | 18.2 | 0.53 (0.48-0.58) | < .0001 | 0.66 (0.60-0.74) | < .0001 |

| T3 | 13.7 | 0.38 (0.32-0.45) | < .0001 | 0.52 (0.43-0.64) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 24.3 | 0.76 (0.68-0.85) | < .0001 | 1.12 (0.96-1.3) | .14 |

| Physician sex | |||||

| Male | 21.5 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Female | 12.9 | 0.54 (0.44-0.66) | < .0001 | 0.78 (0.61-1.00) | .05 |

| Unknown | 25.4 | 1.25 (1.11-1.40) | .0003 | … | … |

| Physician graduation year | |||||

| Prior to 1980 | 20.0 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 22.0 | 1.13 (1.03-1.24) | .01 | 1.31 (1.13-1.52) | .0003 |

| After 1990 | 21.1 | 1.07 (0.95-1.21) | .28 | 1.68 (1.39-2.03) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 25.4 | 1.37 (1.21-1.55) | < .0001 | 1.95 (1.26-3.01) | .003 |

| Trained in the United States | |||||

| Yes | 22.9 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| No | 15.5 | 0.62 (0.56-0.69) | < .0001 | 0.69 (0.59-0.82) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 24.5 | 1.10 (0.96-1.25) | .17 | 1.09 (0.70-1.70) | .70 |

| Degree | |||||

| MD | 21.4 | Reference | … | … | … |

| DO | 15.6 | 0.68 (0.55-0.85) | .0005 | … | … |

| Unknown | 24.5 | 1.20 (1.05-1.36) | .007 | … | … |

| Total No. of patients | |||||

| 1 | 16.5 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 2-5 | 22.1 | 1.43 (1.29-1.60) | < .0001 | 1.47 (1.26-1.71) | < .0001 |

| 6-10 | 23.4 | 1.54 (1.37-1.73) | < .0001 | 1.86 (1.50-2.30) | < .0001 |

| > 10 | 25.4 | 1.72 (1.52-1.94) | < .0001 | 1.45 (1.09-1.93) | .01 |

| Specialty of physicianc | |||||

| Pulmonary | 13.2 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Internal medicine | 11.5 | 0.86 (0.75-0.97) | .02 | 0.97 (0.80-1.17) | .75 |

| General surgery | 36.4 | 3.77 (3.21-4.42) | < .0001 | 4.26 (3.36-5.40) | < .0001 |

| Thoracic surgery | 67.5 | 13.71 (12.22-15.38) | < .0001 | 14.79 (12.46-17.55) | < .0001 |

| Other | 4.3 | 0.30 (0.19-0.47) | < .0001 | 0.37 (0.23-0.61) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 8.8 | 0.64 (0.5-0.81) | .0002 | 0.46 (0.32-0.64) | < .0001 |

See Table 1 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

% Poverty is the percentage of people living in that patient’s census tract living below the poverty level. The variable itself has a P value of .036.

% Without a high school education is the percentage of people living in that patient’s census tract with that level of education.

Refers to the physician who ordered or performed the first invasive diagnostic test. For bronchoscopy and surgical procedures, this was the physician performing the procedure. For CT scan-guided biopsy, this was the referring physician. Internal medicine includes family practice and all subspecialties of internal medicine other than pulmonary medicine physicians. Surgery includes all other subspecialties of surgery other than thoracic or cardiothoracic surgery. Thoracic surgery and cardiothoracic surgery are included under thoracic surgery.

Table 5.

—Associations Between Specialty, Graduation Year, and Guideline-Consistent Care of Physicians Ordering or Performing the First Invasive Diagnostic Test

| Specialtya | No. Patients | Guideline-Consistent Care, % | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Internal medicine | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 1,424 | 6.95 | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 1,137 | 7.74 | 1.12 (0.83-1.51) | .4469 |

| 1990+ | 498 | 6.83 | 0.98 (0.66-1.47) | .9247 |

| Unknown | 220 | 28.64 | 5.37 (3.76-7.67) | < .0001 |

| Surgery | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 499 | 34.87 | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 316 | 41.77 | 1.34 (1.00-1.79) | .0477 |

| 1990+ | 132 | 35.61 | 1.03 (0.69-1.54) | .8747 |

| Unknown | 157 | 62.42 | 3.10 (2.14-4.50) | < .0001 |

| Oncology | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 149 | 1.34 | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 102 | 4.9 | 3.79 (0.72-19.92) | .1157 |

| 1990+ | 42 | 2.38 | 1.79 (0.16-20.26) | .6372 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | … | … |

| Pulmonary | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 3,816 | 8.54 | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 3,102 | 13.09 | 1.61 (1.38-1.88) | < .0001 |

| 1990+ | 1,227 | 19.48 | 2.59 (2.16-3.10) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 591 | 12.86 | 1.58 (1.21-2.06) | .0008 |

| Other | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 58 | 0 | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 80 | 2.5 | … | .9326 |

| 1990+ | 50 | 0 | … | 1.00 |

| Unknown | 8 | 0 | … | 1.00 |

| Thoracic surgery | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 1,190 | 70.84 | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 705 | 71.77 | 1.05 (0.85-1.29) | .6648 |

| 1990+ | 159 | 79.87 | 1.63 (1.09-2.45) | .0183 |

| Unknown | 355 | 74.65 | 1.21 (0.93-1.59) | .1625 |

| Unknown | ||||

| Prior to 1980 | 188 | 17.02 | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 74 | 33.78 | 2.49 (1.35-4.60) | .0036 |

| 1990+ | 18 | 22.22 | 1.39 (0.43-4.51) | .5803 |

| Unknown | 1,476 | 2.3 | 0.12 (0.07-0.19) | < .0001 |

For procedures, this was the physician performing the procedure. For CT scan-guided biopsy, this was the referring physician. Internal medicine includes family practice and all subspecialties of internal medicine other than oncology and pulmonary medicine physicians. Surgery includes all other subspecialties of surgery other than thoracic or cardiothoracic surgery. Thoracic surgery and cardiothoracic surgery are included under thoracic surgery.

There was also significant regional variability in whether mediastinal sampling was done at any point (vs never) in patients with NSCLC (range, 41%-66%) (see Table 6 for multivariate analysis). When we restricted our analysis to SEER data from 2004 to 2007, the results were similar (e-Table 4 (1.1MB, pdf) ).

Table 6.

—Factors Associated With Mediastinal Sampling Being Performed in Patients With NSCLC

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

| Variables | Mediastinal Sampling Performed, % | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Patient age, y | |||||

| 66-70 | 61.3 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 71-75 | 59.2 | 0.91 (0.83-1.00) | .051 | 0.91 (0.83-1.01) | .0654 |

| 76-80 | 53.3 | 0.72 (0.65-0.79) | < .0001 | 0.69 (0.62-0.76) | < .0001 |

| > 80 | 42.0 | 0.46 (0.41-0.51) | < .0001 | 0.43 (0.38-0.49) | < .0001 |

| Patient sex | |||||

| Male | 55.2 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Female | 56.8 | 1.07 (1.00-1.15) | .0647 | … | … |

| Patient race | |||||

| White | 57.0 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Hispanic | 53.8 | 0.88 (0.74-1.04) | .1274 | 0.97 (0.81-1.17) | .7573 |

| Black | 43.6 | 0.58 (0.51-0.67) | < .0001 | 0.66 (0.56-0.78) | < .0001 |

| Other | 57.1 | 1.00 (0.83-1.21) | .9774 | 1.05 (0.83-1.33) | .6899 |

| Urban/rural | |||||

| Big metro | 57.2 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Metro | 55.6 | 0.94 (0.86-1.02) | .1135 | … | … |

| Urban | 52.7 | 0.83 (0.72-0.96) | .0116 | … | … |

| Less urban | 52.2 | 0.82 (0.72-0.92) | .0012 | … | … |

| Rural | 53.9 | 0.88 (0.68-1.13) | .2995 | … | … |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 1995 | 67.0 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 1996 | 63.8 | 0.87 (0.65-1.16) | .3361 | … | … |

| 1997 | 65.5 | 0.94 (0.69-1.26) | .6583 | … | … |

| 1998 | 61.3 | 0.78 (0.58-1.05) | .0977 | … | … |

| 1999 | 65.2 | 0.92 (0.67-1.27) | .6221 | … | … |

| 2000 | 61.3 | 0.78 (0.61-1.00) | .0537 | … | … |

| 2001 | 55.3 | 0.61 (0.48-0.77) | < .0001 | … | … |

| 2002 | 54.9 | 0.60 (0.47-0.76) | < .0001 | … | … |

| 2003 | 54.1 | 0.58 (0.46-0.73) | < .0001 | … | … |

| 2004 | 53.5 | 0.57 (0.45-0.71) | < .0001 | … | … |

| 2005 | 53.1 | 0.56 (0.44-0.70) | < .0001 | … | … |

| 2006 | 52.8 | 0.55 (0.44-0.70) | < .0001 | … | … |

| 2007 | 53.2 | 0.56 (0.44-0.71) | < .0001 | … | … |

| SEER/TCR region | |||||

| California | 58.9 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Atlanta and rural Georgia | 50.6 | 0.72 (0.58-0.88) | .0019 | 0.73 (0.57-0.92) | .0073 |

| Connecticut | 65.8 | 1.34 (1.14-1.57) | .0003 | 1.31 (1.09-1.58) | .0043 |

| Detroit | 60.0 | 1.05 (0.91-1.21) | .5442 | 0.92 (0.76-1.11) | .3831 |

| Hawaii | 50.0 | 0.70 (0.52-0.95) | .0209 | 0.65 (0.45-0.95) | .0245 |

| Iowa | 54.8 | 0.85 (0.73-0.99) | .036 | 0.93 (0.75-1.15) | .4957 |

| Kentucky | 51.5 | 0.74 (0.64-0.86) | .0001 | 0.74 (0.61-0.91) | .0033 |

| Louisiana | 40.5 | 0.48 (0.40-0.56) | < .0001 | 0.59 (0.48-0.72) | < .0001 |

| New Jersey | 58.8 | 1.00 (0.87-1.14) | .9424 | 1.17 (0.99-1.38) | .058 |

| New Mexico | 59.9 | 1.04 (0.76-1.42) | .7909 | 1.05 (0.74-1.51) | .7725 |

| Seattle | 59.1 | 1.01 (0.83-1.22) | .9209 | 1.19 (0.94-1.49) | .1436 |

| Texas | 52.9 | 0.79 (0.70-0.88) | < .0001 | 1.22 (1.06-1.41) | .0061 |

| Utah | 63.5 | 1.21 (0.82-1.79) | .3266 | 1.25 (0.84-1.85) | .2657 |

| % Povertya | |||||

| ≤ 4.76% | 60.4 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 4.77-9.07 | 57.0 | 0.87 (0.79-0.97) | .0083 | … | … |

| 9.08-16.53 | 54.3 | 0.78 (0.71-0.87) | < .0001 | … | … |

| > 16.53 | 49.6 | 0.65 (0.58-0.72) | < .0001 | … | … |

| Unknown | 67.4 | 1.36 (1.11-1.66) | .0035 | … | … |

| % Non-high schoola | |||||

| ≤ 10.09 | 60.6 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 10.1-17.18 | 56.6 | 0.85 (0.77-0.94) | .0015 | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | .0132 |

| 17.19-27.8 | 54.0 | 0.76 (0.69-0.85) | < .0001 | 0.83 (0.74-0.92) | .0009 |

| > 27.85 | 50.2 | 0.66 (0.59-0.73) | < .0001 | 0.8 (0.71-0.91) | .0003 |

| Unknown | 67.4 | 1.34 (1.10-1.65) | .0045 | 1.04 (0.60-1.80) | .8982 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| 0 | 59.6 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 1 | 54.8 | 0.82 (0.76-0.89) | < .0001 | 0.83 (0.76-0.90) | < .0001 |

| 2+ | 48.1 | 0.63 (0.57-0.69) | < .0001 | 0.65 (0.59-0.72) | < .0001 |

| T stages | |||||

| T1/T0 | 69.6 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| T2 | 56.4 | 0.56 (0.51-0.62) | < .0001 | 0.61 (0.55-0.68) | < .0001 |

| T3 | 35.8 | 0.24 (0.21-0.28) | < .0001 | 0.28 (0.24-0.32) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 48.8 | 0.42 (0.37-0.47) | < .0001 | 0.38 (0.33-0.43) | < .0001 |

| Physician sex | |||||

| Male | 55.6 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Female | 49.3 | 0.78 (0.67-0.90) | .0007 | … | … |

| Unknown | 61.6 | 1.28 (1.15-1.44) | < .0001 | … | … |

| Physician graduation year | |||||

| Prior to 1980 | 56.1 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 1980-1989 | 54.8 | 0.95 (0.87-1.03) | .199 | … | … |

| 1990+ | 52.9 | 0.88 (0.79-0.98) | .02 | … | … |

| Unknown | 61.6 | 1.26 (1.12-1.41) | .0002 | … | … |

| Trained in the United States | |||||

| Yes | 56.4 | Reference | … | … | … |

| No | 52.0 | 0.84 (0.77-0.91) | < .0001 | … | … |

| Unknown | 61.0 | 1.21 (1.07-1.37) | .0024 | … | … |

| Degree | |||||

| MD | 55.7 | Reference | … | … | … |

| DO | 48.4 | 0.75 (0.63-0.89) | .0009 | … | … |

| Unknown | 61.0 | 1.25 (1.10-1.41) | .0004 | … | … |

| Total No. of patients | |||||

| 1 | 53.2 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 2-5 | 56.2 | 1.13 (1.03-1.23) | .0095 | 1.08 (0.96-1.20) | .1941 |

| 6-10 | 57.8 | 1.21 (1.09-1.33) | .0003 | 1.22 (1.06-1.39) | .0048 |

| > 10 | 57.6 | 1.19 (1.07-1.33) | .0016 | 1.04 (0.87-1.24) | .6748 |

| Specialty of physicianb | |||||

| Pulmonary | 50.5 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Internal medicine | 49.0 | 0.94 (0.86-1.03) | .2046 | 0.98 (0.88-1.10) | .7499 |

| General surgery | 64.4 | 1.78 (1.51-2.09) | < .0001 | 1.82 (1.48-2.25) | < .0001 |

| Thoracic surgery | 84.3 | 5.25 (4.59-6.01) | < .0001 | 4.68 (3.98-5.50) | < .0001 |

| Other | 40.0 | 0.65 (0.53-0.80) | < .0001 | 0.66 (0.53-0.83) | .0004 |

| Unknown | 54.5 | 1.17 (1.01-1.36) | .036 | 1.08 (0.91-1.29) | .3589 |

See Table 1 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

% Poverty and % without a high school education is the percentage of people living in that patient’s census tract living below the poverty level or with that level of education.

Refers to the physician who ordered or performed the first invasive diagnostic test. For bronchoscopy and surgical procedures, this was the physician performing the procedure. For CT scan-guided biopsy, this was the referring physician. Internal medicine includes family practice and all subspecialties of internal medicine other than oncology and pulmonary medicine physicians. Surgery includes all subspecialties of surgery other than thoracic or cardiothoracic surgery. Thoracic surgery and cardiothoracic surgery are included under thoracic surgery.

There were also differences in the propensity of pulmonologists to perform TBNA, with recent graduates being more likely to perform TBNA than older graduates (P < .001) (Table 7). In hierarchical multivariate analysis, TBNA use was associated with more recent physician graduation, physicians trained in the United States, lower patient age, lower T stage, not being in a big metropolitan area, and geographic region (Table 8).

Table 7.

—Use of TBNA Among Pulmonologists Caring for Patients With Lung Cancer as a Function of Medical School Graduation Year

| Year of Medical School Graduation | Did Not Perform Any TBNA Procedures but Ordered or Performed Other Invasive Diagnostic Tests | Performed One or More TBNA Procedures | Totala |

| Prior to 1980 | 564 (79) | 150 (21)b | 714 (100) |

| 1980-1989 | 470 (71) | 189 (29)b | 659 (100) |

| 1990+ | 256 (65) | 138 (35)b | 394 (100) |

| Unknown | 170 (80) | 42 (20) | 212 (100) |

| Total | 1,366 (72) | 521 (28) | 1,979 (100) |

Data are presented as No. (%). See Table 2 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

Total is the number of pulmonologists ordering and/or performing invasive diagnostic testing in patients with lung cancer in this cohort. Invasive tests include bronchoscopy or referral for CT scan-guided biopsy.

P value < .001.

Table 8.

—Factors Associated With TBNA Use Among Pulmonologists

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

| Variables | % Having TBNA | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value | Crude OR (95% CI) | P Value |

| Patient age, y | |||||

| 66-70 | 12.0 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 71-75 | 10.0 | 0.82 (0.68-0.98) | .0291 | 0.82 (0.69-0.98) | .0265 |

| 76-80 | 10.3 | 0.84 (0.70-1.03) | .0869 | 0.84 (0.70-1.00) | .0458 |

| > 80 | 8.5 | 0.68 (0.53-0.87) | .0022 | 0.69 (0.54-0.87) | .0016 |

| Patient sex | |||||

| Male | 10.7 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Female | 10.3 | 0.96 (0.83-1.11) | .6024 | … | … |

| Patient race | |||||

| White | 10.6 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Hispanic | 9.0 | 0.83 (0.57-1.20) | .3238 | … | … |

| Black | 11.8 | 1.12 (0.86-1.47) | .3969 | … | … |

| Other | 6.6 | 0.60 (0.36-0.99) | .0439 | … | … |

| Urban/rural | |||||

| Big metro | 9.9 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Metro | 11.7 | 1.20 (1.02-1.42) | .0292 | 1.75 (1.36-2.26) | < .0001 |

| Urban | 10.0 | 1.01 (0.74-1.36) | .9763 | 1.40 (0.99-1.98) | .0565 |

| Less urban | 10.3 | 1.05 (0.81-1.34) | .7277 | 1.48 (1.09-2.01) | .0128 |

| Rural | 10.1 | 1.02 (0.62-1.67) | .9531 | 1.52 (0.97-2.37) | .0672 |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||

| 1995 | 9.1 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 1996 | 6.2 | 0.66 (0.32-1.35) | .2517 | … | … |

| 1997 | 6.9 | 0.74 (0.37-1.50) | .4082 | … | … |

| 1998 | 7.9 | 0.86 (0.44-1.69) | .664 | … | … |

| 1999 | 7.9 | 0.85 (0.42-1.76) | .6672 | … | … |

| 2000 | 10.2 | 1.14 (0.65-1.97) | .6521 | … | … |

| 2001 | 9.5 | 1.05 (0.62-1.76) | .8703 | … | … |

| 2002 | 9.7 | 1.07 (0.64-1.81) | .795 | … | … |

| 2003 | 9.5 | 1.04 (0.62-1.76) | .8714 | … | … |

| 2004 | 12.3 | 1.40 (0.84-2.32) | .1994 | … | … |

| 2005 | 11.2 | 1.26 (0.75-2.11) | .383 | … | … |

| 2006 | 12.2 | 1.38 (0.83-2.31) | .2173 | … | … |

| 2007 | 13.1 | 1.51 (0.90-2.53) | .1154 | … | … |

| SEER/TCR region | |||||

| California | 7.9 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| Atlanta and rural Georgia | 6.6 | 0.82 (0.5-1.37) | .4546 | 1.15 (0.65-2.05) | .6308 |

| Connecticut | 7.4 | 0.94 (0.62-1.41) | .757 | 0.74 (0.41-1.33) | .3138 |

| Detroit | 17.8 | 2.54 (1.88-3.43) | < .0001 | 3.51 (2.30-5.37) | < .0001 |

| Hawaii | 6.2 | 0.77 (0.35-1.71) | .5237 | 0.64 (0.25-1.64) | .3495 |

| Iowa | 10.0 | 1.29 (0.93-1.80) | .1278 | 1.52 (0.94-2.46) | .0857 |

| Kentucky | 8.6 | 1.10 (0.75-1.60) | .6314 | 1.14 (0.71-1.82) | .5932 |

| Louisiana | 2.9 | 0.35 (0.20-0.60) | .0001 | 0.31 (0.16-0.61) | .0006 |

| New Jersey | 11.9 | 1.58 (1.18-2.12) | .0021 | 1.52 (1.00-2.30) | .0496 |

| New Mexico | 10.9 | 1.43 (0.72-2.84) | .3114 | 1.16 (0.50-2.66) | .7292 |

| Seattle | 21.4 | 3.18 (2.26-4.49) | < .0001 | 2.45 (1.51-4.00) | .0003 |

| Texas | 11.8 | 1.56 (1.22-2.00) | .0004 | 1.02 (0.70-1.49) | .9137 |

| Utah | 16.1 | 2.24 (1.22-4.12) | .0092 | 1.74 (0.76-3.99) | .1867 |

| % Povertya | |||||

| ≤ 4.76 | 10.6 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 4.77-9.07 | 10.2 | 0.96 (0.77-1.18) | .6705 | … | … |

| 9.08-16.53 | 12.3 | 1.18 (0.97-1.45) | .1012 | … | … |

| > 16.53 | 8.9 | 0.82 (0.66-1.03) | .0827 | … | … |

| Unknown | 9.3 | 0.86 (0.55-1.34) | .5078 | … | … |

| % Non-high schoola | |||||

| ≤ 10.09 | 10.5 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 10.1-17.18 | 11.6 | 1.11 (0.91-1.37) | .3052 | … | … |

| 17.19-27.8 | 11.3 | 1.09 (0.89-1.34) | .4133 | … | … |

| > 27.85 | 8.7 | 0.81 (0.65-1.01) | .0622 | … | … |

| Unknown | 9.3 | 0.87 (0.56-1.36) | .5429 | … | … |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| 0 | 11.2 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 1 | 10.3 | 0.91 (0.77-1.07) | .2501 | … | … |

| 2+ | 9.1 | 0.79 (0.65-0.97) | .0211 | … | … |

| T stages | |||||

| T1 (include T0) | 10.8 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| T2 | 9.0 | 0.82 (0.67-1.01) | .0638 | 0.91 (0.75-1.12) | .3773 |

| T3 | 9.7 | 0.89 (0.66-1.20) | .4401 | 0.91 (0.67-1.25) | .5681 |

| Unknown | 13.9 | 1.34 (1.07-1.67) | .011 | 1.88 (1.48-2.38) | < .0001 |

| Physician sex | |||||

| Male | 10.2 | Reference | … | … | … |

| Female | 12.4 | 1.24 (0.93-1.65) | .1373 | … | … |

| Unknown | 12.1 | 1.21 (0.90-1.62) | .1997 | … | … |

| Physician graduation year | |||||

| Prior to 1980 | 7.2 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| 1980-1989 | 11.4 | 1.66 (1.39-1.99) | < .0001 | 1.79 (1.36-2.35) | < .0001 |

| After 1990 | 17.1 | 2.67 (2.18-3.27) | < .0001 | 2.66 (1.98-3.58) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 12.1 | 1.79 (1.31-2.45) | .0002 | 2.38 (1.03-5.50) | .0432 |

| Trained in the United States | |||||

| Yes | 11.8 | Reference | … | Reference | … |

| No | 6.6 | 0.53 (0.44-0.65) | < .0001 | 0.54 (0.41-0.71) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 11.9 | 1.01 (0.73-1.40) | .9344 | 0.67 (0.27-1.66) | .3834 |

| Degree | |||||

| MD | 10.2 | Reference | … | … | … |

| DO | 14.7 | 1.52 (1.13-2.03) | .0052 | … | … |

| Unknown | 11.9 | 1.19 (0.87-1.64) | .2815 | … | … |

| Total No. of patients | |||||

| 1 | 12.3 | Reference | … | … | … |

| 2-5 | 9.6 | 0.76 (0.58-1.00) | .0525 | … | … |

| 6-10 | 10.3 | 0.82 (0.62-1.08) | .1566 | … | … |

| > 10 | 11.4 | 0.92 (0.69-1.21) | .5429 | … | … |

Population is all patients with an invasive test done by pulmonologists (n = 7,695). Hierarchical analysis with patients nested within physicians.

% Having TBNA is the percentage of patients that ever had TBNA done prior to initiation of treatment. See Table 1 and 2 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

% Poverty and % without a high school education is the percentage of people living in that patient’s census tract living below the poverty level or with that level of education.

For surgical procedures, the probability of performing mediastinoscopy prior to proceeding to thoracotomy was not associated with graduation year and did not vary significantly between general and thoracic surgeons (e-Tables 5 (1.1MB, pdf) , 6 (1.1MB, pdf) ). There were, however, widespread geographic differences in the probability of having mediastinoscopy prior to thoracotomy (range, 20%-69%).

Discussion

We found that in patients with regional spread to the hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes without distant metastases, mediastinal lymph node sampling was performed first as per guidelines in only 21% of patients. Only 56% of patients with NSCLC ever had mediastinal sampling performed prior to treatment. Correction of these quality gaps requires insight into the determinants of practice patterns.16,17 Our data indicate there are multiple physician-level and system-level determinants that impact the probability of receiving guideline-consistent care. We found that more recent graduates in pulmonary medicine (P < .001) were more likely to deliver guideline-consistent care. This paralleled a trend in procedural practices, with more recent graduates being more likely to perform TBNA. This suggests that at least some of the variation in practice patterns is due to differences in procedural training. However, graduation year did not impact practice patterns for other disciplines. This suggests that the effectiveness of knowledge dissemination for this particular problem has not been equal between disciplines. Specialties that deal with this problem more frequently have seen the greatest improvement in terms of recent graduate performance.

Although our study does add to the existing body of evidence in the lung cancer field, there are several limitations that are worth considering. This was an administrative database and included only Medicare patients from 1995 to 2007. As such, it may not be as generalizable to current practice or to younger patients or those with alternative insurance schedules. In addition, most of the patients came from SEER, so this may not be generalizable to non-SEER registry participants. However, we did validate our findings from the SEER registry by comparing them with the TCR, and the results are consistent. In addition, a retrospective analysis of patients seen in 2009 demonstrated similar findings, suggesting that these quality gaps have persisted.18

In addition, because these are administrative data, we cannot determine which patients were not surgical candidates because of concurrent severe COPD, other comorbidities, or patient preferences, and this might have impacted the use of surgical mediastinal sampling. We did adjust for comorbidities using the Charlson comorbidity index, but there is probably residual confounding. However, we restricted our cohort to patients who received treatment. Since all the patients were healthy enough to have treatment, mediastinal sampling would still have been necessary to determine which patients should receive radiation alone and which should receive chemotherapy and radiation. If the patient’s performance status was poor, then TBNA would have been a very suitable method to both stage and diagnose the patient, since it has a much lower complication rate than CT scan-guided biopsy.20,21

Similarly, because these were administrative data, we had no way to verify that the lymph nodes were positive on either CT or PET scan. If the lymph nodes were negative on CT and PET scan, then mediastinal sampling would not have been warranted. However, previous studies have shown that patients with CT scan-negative and/or PET scan-negative lymph nodes have a very low incidence of occult mediastinal disease—around 5% to 7%.22‐25 So although a small fraction of the patients in this study probably did have lymph nodes that were negative on CT and PET scan, it is very likely that the number of patients receiving guideline-inconsistent care is significant.

Given these limitations, we cannot know precisely the exact incidence of guideline-consistent care or the magnitude of the quality gap. It would be unreasonable to expect 100% guideline-consistent care when using purely administrative data as the reference source, since there are just too many contingencies to account for. Indeed, administrative data probably are insufficient to establish precise benchmarks for a problem of this complexity. However, based on the available data, we can say that the incidence of guideline-consistent care is low enough to warrant attention. In addition, despite the fact that we cannot define exactly how often things should have been done differently, we can use the data to gain insights into what factors are associated with quality gaps. It is knowledge of these factors that is truly valuable, not defining the exact incidence of guideline-consistent care.

In this regard, we identified several factors that may be contributing to the quality gap. The data show that one of the most common errors was in test sequencing, with CT scan-guided biopsy and bronchoscopy without TBNA being ordered first, and that this testing was most frequently ordered by internists and pulmonologists. It is, therefore, logical to integrate internists, pulmonologists, and interventional radiologists into the solution. Pulmonologists should not be performing bronchoscopy without EBUS-TBNA for these patients, since sampling the mediastinum is the critical first step. Similarly, if a patient is referred for CT scan-guided biopsy, and there is mediastinal lymphadenopathy that has not been biopsied, the interventional radiologist should discuss this with the referring physician, so that unnecessary procedures can be avoided. Traditional quality improvement, benchmarking, and targeted physician education programs are well suited for achieving these goals.

We also observed that 44% of patients never had any mediastinal sampling yet received treatment. One possible explanation is that oncologists and radiation oncologists are unaware of the necessity of proper mediastinal sampling, but this would be unlikely, although it might account for a fraction of the observed quality gap. Alternatively, it is more likely that there is a lack of access to specialists who have the capability to sample the mediastinum effectively, such that some physicians view the risk-benefit equation differently, given their own local practice environment. This would be consistent with the significant regional variations observed (guideline-consistent care range, 12%-29%) and with the low percentage of pulmonologists who performed even one TBNA (Table 7).

However, if the material cause of the quality gap is scarcity of physicians who can perform TBNA, the efficient cause of the quality gap must be failures in the physician training system. The system failure is both at the level of fellowship training and at the level of continuing physician education. The fellowship training problem can be seen in the low percentage (35%) of pulmonologists graduating after 1990 who saw patients with lung cancer and performed even one TBNA.

There is also a system failure at the level of continuing physician education. Most patients were cared for by older physicians. When new technologies are developed, older physicians need a way to update their training. But we found that older pulmonologists were much less likely to use TBNA than their younger counterparts (P < .001). This suggests that the system is failing to provide accessible effective quality training to practicing physicians. Although there is an abundance of continuing medical education, none of these programs is sufficient for invasive procedures, since they do not provide what is truly needed—supervised practice on patients in real life. This study demonstrates how deficits in the system of procedural training can eventually lead to suboptimal practice patterns at the system level (due to lack of skilled providers) and eventually to suboptimal patient outcomes.

Unfortunately, the existing regulatory and administrative-medical-legal system sets up so many barriers to hands-on training that practicing physicians cannot overcome them. Ironically, it is much easier for a resident or fellow or even a student to travel to another institution to get training on patients than an attending physician. Yet the attending physician by definition has more experience and, therefore, should represent a lower risk. Thus, the root cause of the quality gaps we observe may lie outside of what many physicians conventionally think of as the health-care delivery system. However, financial, regulatory, or legislative incentives are recognized quality-improvement strategies.26 Quality interventions are usually thought of as active interventions—meaning more new things, whether they are reminder systems, data relays, feedback, self-management, organizational changes, financial incentives, licensure requirements, or accreditation. Ironically, what might prove more effective is less—meaning fewer barriers to obtaining additional hands-on training for practicing physicians. Although this would take careful legislative and administrative planning, the payoff would be immense, since it would impact not only lung cancer staging but all areas of procedural interventions, and the payoff would continue with each new cycle of technological innovation. Certainly there are many other determinants that impact quality gaps and implementation delays, and the degree to which training barriers impact these will vary with the procedure and the technology. But making even a small dent in such a large and recurring problem would be significant.

Another system-level factor that may be contributing to TBNA underuse is financial.27‐30 Previous studies have shown that from a payer perspective EBUS-TBNA is the most cost-effective strategy.31 However, physicians may not believe it is worthwhile to learn this technology, since it will be a money loser for their practice as compared with alternative strategies of seeing more outpatients or performing other procedures that are reimbursed better. Strategies such as referring patients for CT scan-guided biopsy or proceeding directly to thoracotomy are much more attractive. For established physicians many years out of fellowship this is likely to be particularly relevant. This is further compounded by inconsistencies in the reimbursement system of Medicare, which pays for ultrasound facilities fees for endoscopy but not bronchoscopy.30 On balance, these economic factors are probably contributing to the relative scarcity of quality care as well.

Regional or structural differences in insurance companies may also be contributing. It is frequently the case that guidelines call for no biopsy of the primary tumor but rather a PET scan to identify extent of disease, yet insurance companies may deny the PET scan unless a biopsy has been performed. This may lead to many physicians adopting an approach of biopsy first, even in the face of a strong clinical suspicion of lung cancer. Evidence-based medicine should be used to drive practice patterns and insurance company policy, rather than having insurance company policy determine practice patterns.

In summary, we found that there are significant quality gaps in the diagnosis and staging of patients with lung cancer. Guideline-consistent care, defined as sampling the mediastinum first in patients with suspected lung cancer, mediastinal adenopathy, and no distant metastases, only occurred in 21% of patients. The probability of guideline-consistent care varied with physician specialty and graduation year and paralleled use of TBNA. We found significant regional variation in care, suggesting that system-level problems are contributing to the quality gap. One of the root causes of the quality gap probably lies in the procedural training system for physicians. In particular, a lack of effective training in fellowship as well as a lack of access to effective procedural training for practicing physicians after graduation is probably contributing to the gap. Addressing the root causes of the quality gap in lung cancer will require educational initiatives as well as fundamental reforms that facilitate more effective training.

Supplementary Material

Online Supplement

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Dr Ost was principal investigator and was responsible for study oversight.

Dr Ost: contributed to data analysis and writing, editing, and review of the manuscript.

Dr Niu: contributed to data analysis and writing, editing, and review of the manuscript.

Dr Elting: contributed to data analysis and writing, editing, and review of the manuscript.

Dr Buchholz: contributed to writing, editing, and review of the manuscript.

Dr Giordano: contributed to data analysis and writing, editing, and review of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST that no potential conflicts of interest exist with any companies/organizations whose products or services may be discussed in this article.

Role of sponsors: The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Texas Department of State Health Services, the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Other contributions: This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. We thank the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc; and the SEER Program tumor registries for their efforts in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. All work was performed at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas.

Additional information: The e-Appendix and e-Tables can be found in the “Supplemental Materials” area of the online article.

Abbreviations

- EBUS

endobronchial ultrasound

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

- TBNA

transbronchial needle aspiration

- TCR

Texas Cancer Registry

Footnotes

Funding/Support: This work was supported in part by the Center for Comparative Effectiveness Research on Cancer in Texas (CERCIT), a multi-university consortium funded by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas [Grant RP101207 by 2P30 CA016672]. Dr Giordano is also supported by the American Cancer Society [Grant RSG-09-149-01-CPHPS]. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the Texas Department of State Health Services and Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas, as part of the statewide cancer reporting program, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries Cooperative Agreement 5U58/DP000824-05.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians. See online for more details.

References

- 1.Ost DE, Yeung S-CJ, Tanoue LT. Gould MK. Clinical and organizational factors in the initial evaluation of patients with lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5_suppl):e121S-e141S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detterbeck FC, Jantz MA, Wallace M, Vansteenkiste J, Silvestri GA. Invasive mediastinal staging of lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007;132(3_suppl):202S-220S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silvestri GA, Gonzalez AV, Jantz MA, et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5_suppl):e211S-e250S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silvestri GA, Gould MK, Margolis ML, et al. Noninvasive staging of non-small cell lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest. 2007;132(3_suppl):178S-201S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin DR, White B, Schmidt-Hansen M, Champion AR, Melder AM; Guideline Development Group. Diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;342:d2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crinò L, Weder W, van Meerbeeck J, Felip E; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Early stage and locally advanced (non-metastatic) non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 5):v103-v115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Leyn P, Lardinois D, Van Schil PE, et al. ESTS guidelines for preoperative lymph node staging for non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32(1):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivera MP, Mehta AC, Wahidi MM. Establishing the diagnosis of lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5_suppl):e142S-e165S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron R, Fringer J, Taylor C, Gilden CR, Figlin RA. Practice guidelines for non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer J Sci Am. 1996;2(suppl 3A):S61-S68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ettinger DS, Cox JD, Ginsberg RJ, et al. NCCN non-small-cell lung cancer practice guidelines. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Oncology (Williston Park). 1996;10(suppl 11):81-111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almeida FA, Uzbeck M, Ost D. Initial evaluation of the nonsmall cell lung cancer patient: diagnosis and staging. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16(4):307-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Little AG, Rusch VW, Bonner JA, et al. Patterns of surgical care of lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80(6):2051-2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schipper P, Schoolfield M. Minimally invasive staging of N2 disease: endobronchial ultrasound/transesophageal endoscopic ultrasound, mediastinoscopy, and thoracoscopy. Thorac Surg Clin. 2008;18(4):363-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haponik EF, Shure D. Underutilization of transbronchial needle aspiration: experiences of current pulmonary fellows. Chest. 1997;112(1):251-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smyth CM, Stead RJ. Survey of flexible fibreoptic bronchoscopy in the United Kingdom. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):458-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prakash UB, Offord KP, Stubbs SE. Bronchoscopy in North America: the ACCP survey. Chest. 1991;100(6):1668-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colt HG, Prakash UBS, Offord KP. Bronchoscopy in North America: survey by the American Association for Bronchology, 1999. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2000;7(1):8-25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almeida FA, Casal RF, Jimenez CA, et al. Quality gaps and comparative effectiveness in lung cancer staging: the impact of test sequencing on outcomes. Chest. 2013;144(6): 1776-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ost DE, Niu J, Elting LS, Buchholz TA, Giordano SH. Quality gaps and comparative effectiveness in lung cancer staging and diagnosis. Chest. 2014;145(2):331-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eapen GA, Shah AM, Lei X, et al. ; American College of Chest Physicians Quality Improvement Registry, Education, and Evaluation (AQuIRE) Participants. Complications, consequences, and practice patterns of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: results of the AQuIRE registry. Chest. 2013;143(4):1044-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Population-based risk for complications after transthoracic needle lung biopsy of a pulmonary nodule: an analysis of discharge records. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):137-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS. Survival of patients with unsuspected N2 (stage IIIA) nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(2):362-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Eloubeidi MA. Routine mediastinoscopy and esophageal ultrasound fine-needle aspiration in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who are clinically N2 negative: a prospective study. Chest. 2006;130(6):1791-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herth FJF, Eberhardt R, Krasnik M, Ernst A. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration of lymph nodes in the radiologically and positron emission tomography-normal mediastinum in patients with lung cancer. Chest. 2008;133(4):887-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gould MK, Kuschner WG, Rydzak CE, et al. Test performance of positron emission tomography and computed tomography for mediastinal staging in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):879-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shojania K, McDonald K, Wachter R. Owens DK, eds. Closing The Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies. Volume 1—Series Overview and Methodology. Technical Review 9 (Contract No. 290-02-0017 to the Stanford University-UCSF Evidence-based Practices Center). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. AHRQ Publication No. 04-0051-1.

- 27.Pastis NJ, Simkovich S, Silvestri GA. Understanding the economic impact of introducing a new procedure: calculating downstream revenue of endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration as a model. Chest. 2012;141(2):506-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowling MR, Perry CD, Chin R, Jr, Adair N, Chatterjee A, Conforti J. Endobronchial ultrasound in the evaluation of lung cancer: a practical review and cost analysis for the practicing pulmonologist. South Med J. 2008;101(5):534-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Callister ME, Gill A, Allott W, Plant PK. Endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes for lung cancer staging: a projected cost analysis. Thorax. 2008;63(4):384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manaker S, Ernst A, Marcus L. Affording endobronchial ultrasound. Chest. 2008;133(4):842-843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharples LD, Jackson C, Wheaton E, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound relative to surgical staging in potentially resectable lung cancer: results from the ASTER randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(18):1-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Online Supplement