Abstract

To identify a panel of tumor associated autoantibodies which can potentially be used as biomarkers for the early diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Thirty-five unique and in-frame expressed phage proteins were isolated. Based on the gene expression profiling, four proteins were selected for further study. Both receiver operating characteristic curve analysis and leave-one-out method revealed that combined measurements of four antibodies produced have better predictive accuracies than any single marker alone. Leave-one-out validation also showed significant relevance with all stages of NSCLC patients. The panel of autoantibodies has a high potential for detecting early stage NSCLC.

Keywords: NSCLC, Tumor-associated autoantibodies, SEREX, Early diagnosis

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers as well as the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide because of its lack of symptoms during the early stages [1,2]. Although it is well studied that early diagnosis of lung cancer can significantly improve the 5-year survival rate up to 45–53% compared to 3–4% of late/distant stage [1,3,4], the dismal fact is that the majority of lung cancer patients are diagnosed at the late stages due to the lack of perceivable symptoms at the early stage of tumorigenesis. Therefore, it is urgent to develop robust non-invasive screening methods to detect lung cancer at curable early stage.

Numerous evidences have demonstrated that the immune system reacts against cancers [5–8]. Autoantibodies have been found to response to over-expressed, mutated, misfolded, or aberrantly degraded tumor self-proteins. This process occurs several months or years earlier than the onset of clinical symptoms of cancer [9–11]. These autoantibodies would serve as pioneer reporters of tumorigenesis. Given the heterogeneity of human lung cancers, the application of a panel of antibodies to several antigens would achieve higher sensitivity and more accuracy than single biomarkers [12,13]. Serological identification of antigens by recombinant expression cloning (SEREX) was initially used to analyze the humoral response to cancers [14]. However, the technical limitations retained its clinical application, such as a large volume of sera to screen the positive phage expression clones, and time-consuming and labor-intensive procedure.

In this study, we chose NSCLC as research subject as lung cancer histologically consists of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and NSCLC which accounts for about 80% cases of all lung cancer. Then we combined phage display technology with immunochemistry to screen the phage expressed immunogenic proteins. Four differentially expressed proteins between patients’ and normal sera were identified as potential NSCLC markers. ELISA was employed to evaluate the prediction ability of the four combined markers versus single markers. Here we brought up a combination of new lung cancer markers that has significant relevance with all stages of lung cancer, specifically the early stage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Population and samples

Malignant tissues were obtained from 20 individuals with histologically confirmed stage I to stage IV NSCLC. Sixty-five serum samples with pathology-proven NSCLC were collected before surgery from March 2008 through March 2009 at Tianjin Medical University General Hospital. The clinical information is listed in Table 1 (Supplementary Appendix). The 41 normal controls samples were from volunteers without a history of cancer registered at the Health Management Center of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital between 2008 and 2009 (Table 2 of the Supplementary Appendix). The detailed descriptions of the controls (age, sex and smoking status matched cohorts) were provided in Tables 3–5 of the Supplementary Appendix. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Table 1.

Sequences identity of selected immunogenic phage displayed tumor-associated proteins.

| Protein | Full name, function/comments | Scorea (bits) |

E-valueb (alignment) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMOX | Homo sapiens spermine oxidase. The overexpression of SMO isoforms can induce epithelial cell apoptosis and DNA damage that may contribute to the pathogenesis of the infection and development of cancer | 1016 | 0.0 (99%) |

| NOLC1 | Homo sapiens nucleolar and coiled-body phosphoprotein 1. A novel nucleolar GTPase/ATPase, represses human cell cycle-dependent genes in quiescence and plays a role in the regulation of tumorigenesis of NPC | 1100 | 0.0 (98%) |

| HMMR | Homo sapiens hyaluronan-mediated motility receptor. Involved in cell motility and proliferation, elicit specific CD8+ T cell responses, associated with higher risk of breast cancer, B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas | 586 | 6e–165 (100%) |

| MALAT1 | Homo sapiens metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1. A long non-coding RNA known to be misregulated in many human cancers, association with metastasis was stage- and histology specific in NSCLC patients | 699 | 0.0 (99%) |

The bit score represents the number of matching nucleotide bases.

E-value is the number of different alignments with scores equivalent to or better than the defined bit score. The lower the e-value is the more significant the score.

2.2. Construction and amplification of phage display NSCLC cDNA library

Total RNAs of 20 NSCLC tissues were extracted following the standard Trizol protocol (Table 1 of the Supplementary Appendix). Equal amounts of total RNA were gathered together and messenger RNA (mRNA) was isolated from the total RNA pool by using Straight A’s mRNA Isolation System (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). To generate a T7 phage display NSCLC cDNA library, cDNA was synthesized by mRNA reverse transcription and ligated into T7 phage vector after digestion using T7 Select OrientExpress cDNA Cloning Systems (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). Then the primary phage library were tittered and amplified as T7Select System Manual described.

2.3. Biopanning of tumor-associated antigen expressing phage clones

The libraries were biopanned with pooled sera from 25 patients with NSCLC (5 allogenic patients’sera and 20 autologous sera) and normal healthy donors, to enrich the population of phage-expressed proteins recognized by tumor-associated antibodies as Zhong described [15]. The only difference is we usedEscherichia coli BLT5403 was used to amplify every rounds of phage eluent, not E. coli BLT5615.

2.4. Immunodetection of tumor-associated antigen expressing phages

The appropriate dilutions of phages from the last biopanning step were mixed with E. coli BLT5403 and performed immunodetection as Zhong described [15].

The immunoreactivity of individual phage plaque was carefully compared in these two membranes probed with pooled patient and normal sera, highly immunoreactive phages observed much stronger signal with patient sera than that with normal sera were selected for further amplification in E. coli BLT5403.

2.5. Sequence analysis of phage displayed tumor-associated protein

The cDNA inserts of isolated Phage clones above were PCR-amplified by a universal primer pair for T7 phage vector (Sense primer: 5′-GGAGCTGTCGTATTCCAGTC-3′; Antisense primer: 5′-AA CCCCTCAAGACCCGTTTA-3′). PCR products were then sequenced and insert DNAs were identified using GeneBank database [16]. The validated phage clones that encode for in-frame proteins and have no amino acid mutations in the open reading frame were subject to the following studies in this paper.

2.6. Microarray profiles of in-frame phage expressed proteins

Genome-wide mRNA expression profiling of 55 NSCLC cell lines and 8 normal HBECs (human bronchial epithelial cells) were performed on Affymetrix Gene Chip U133 Plus 2.0 microarrays. Gene expression profiles of 112 NSCLC cell lines and 59 normal HBECs or HSAECs (human small airway epithelial cells) were determined by Illumina human WG-6 V3 beadchip, and 83 NSCLC and paired nonmalignant lung tissue samples were also determined by Illumina human WG-6 V3 beadchip. All array data were log-transformed and quantile-normalized. Validated phage expressed proteins were correlated with their respective microarray gene expression profiles to confirm their expression levels.

2.7. Measurement of serum antibodies to phage displayed tumorassociated proteins

The four phage displayed up-regulated proteins (NOLC1, HMMR, MALAT1 and SMOX) were selected to investigate the immunospecific binding by Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and evaluate their immunogenic activities with different patient serum. Ninety-six-well microtiter plates (Jet Biofil, Guangzhou, China) were separately coated with the 4 Cscl-purified phage displayed proteins with empty phages as negative control (1 × 109 phage/well) at 4 °C overnight. After blocked and washed, Serially diluted serum samples from 3 other patients excluded from the biopanning process were added to each well and incubated at 37 °C. Plates were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Then tetramethyl benzidine(TMB)/H2O2 substrate was added to each well. The reaction was stopped immediately with 2 M H2SO4. The plate was read on a spectrophotometer at 450λ. Each serum sample was run in triplicate.

We then measured the autoantibody activities in serum samples from 40 NSCLC patients and 36 healthy matched controls against the 4 phage displayed antigens with single dilution (dilution factor: 1/1,000). The data were analyzed both with individual marker and combinations of four markers.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was done with SAS package software. ELISA data for all 76 samples (40 patient samples and 36 healthy control samples) were randomly chosen to build up classifiers that were able to distinguish patient samples from normal samples using individual or a combination of markers. Logistic regression analysis was used to predict the possibility that a sample was from a NSCLC patient. Receiver operating characteristic curves were generated to compare the area under the curve (AUC) and the predictive sensitivity and specificity. The classifiers were further examined by using leave-one-out cross-validation.

3. Results

3.1. Construction and analysis of T7 phage display NSCLC cDNA library

To develop a phage-display library of NSCLC, we isolated total RNA from 20 NSCLC tumor tissues. The integrity of RNA product was assessed by the UV spectrophotometry (ratio of A260/A280 is greater than 1.8) and gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1A of the Supplementary Appendix). mRNA was successively isolated from total RNA and its high integrity was demonstrated also by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1B of the Supplementary Appendix).

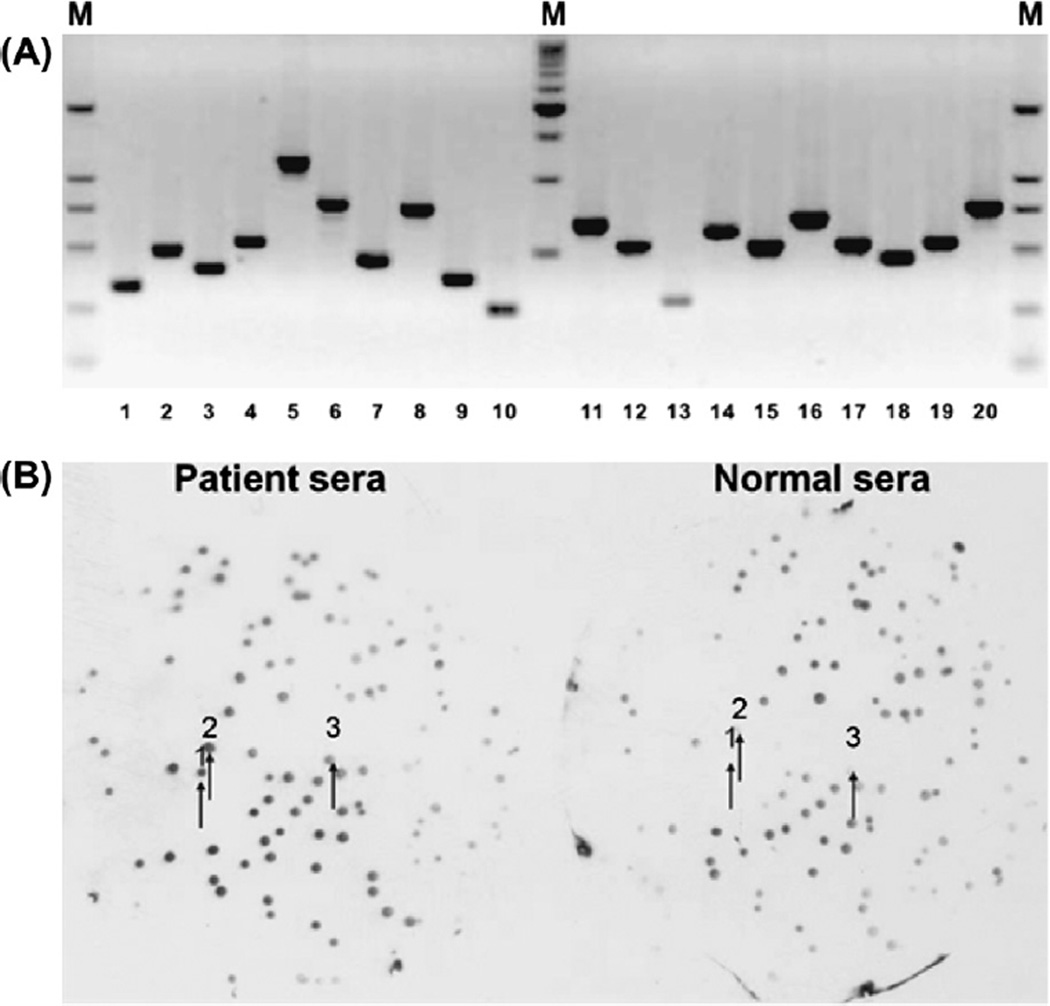

Fig. 1.

(A) PCR analysis of random plaque from T7 phage display NSCLC cDNA library. PCR amplification of 20 random plaques showed that recombination ratio was 100% and Inserts range from 300 bp to 1500 bp (M: DL2000 DNA Maker). (B) Comparison of the immunoreactivity of individual phage clones with pooled patient and normal sera after biopanning process. Two nitrocellulose membranes were placed on and then lifted from the same phage grown plate of biopan 4. One membrane was probed with pooled patient sera and the other was probed with pooled normal sera. After ECL detection, a large number of clone relative spots showed higher immunoreactivity on the membrane incubated with patient sera than on the membrane incubated with normal sera. The arrows indicated the same spots on the duplicate membranes.

The primary library titers were 1.3 × 106 pfu/ml as determined by plaque assay, and attained to concentration of 9 × 1010 pfu/ml of phage after the library amplification. PCR amplification of 20 random plaques showed that recombination rate was 100% with inserts range from 300 to 1500 bp (Fig. 1A).

3.2. Screening of immunogenic tumor-associated antigen expressing phage clones

The duplicate plaque-lift membranes probed with pooled patient sera and normal sera respectively after the fourth biopanning developed dots on films. Each dot indicated one phage plaque on the plate. The dot with dark color indicated the strong reaction with antibodies. Totally, 148 dots that showed relatively higher activities with patient sera (dark color) while had lower activities with normal sera (light color) were matched with their corresponding clones on the plates (Fig. 1B). Highly immunoreactive phage clones were selected from plates as tumor-associated antigen expressing phage clones.

3.3. Characterizations of immunogenic antigen-expressing phage clones

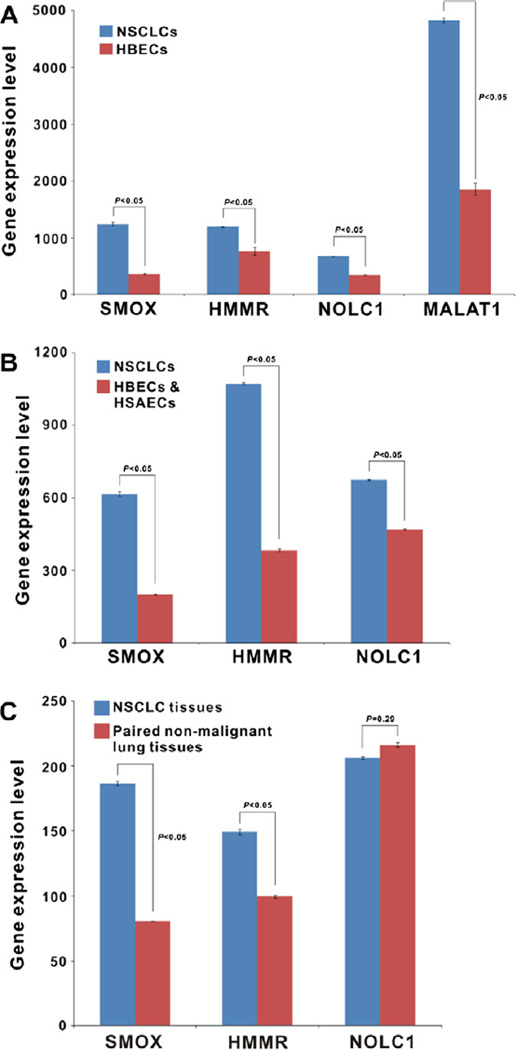

One hundred and forty-eight highly immunoreactive phage clones were isolated for PCR, sequenced and compared to GeneBank database. All sequences were assessed by bit score, e-value and percent sequence match. Of these, 69 were in-frame known genes but 34 phage clones were found redundant, and the other 79 clones were either in untranslated regions of expressed genes or not associated with any known gene (Table 6 of the Supplementary Appendix). According to the gene expression profiling, four in-frame proteins (SMOX, NOLC1, MALAT1 and HMMR) were selected for the further study. After analysis with Affymetrix Gene Chip U133 Plus 2.0 microarray, the mRNA transcripts of these four proteins were significantly up-regulated in NSCLC cell lines as compared with HBECs (fold difference >1.50, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). When tested in Illumina human WG-6 V3 beadchip, there were statistically significant differences in SMOX and HMMR gene expression level between NSCLC cell lines in contrast to HBECs/HSAECs (up-regulated fold differences >1.50, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2B), similar results were also found in 83 NSCLC tissue samples compared with non-malignant paired lung tissues (up-regulated fold differences ≥1.50, p < 0.05) (Fig. 2C). But NOLC1 expression difference was not so dramatic in cell lines profiled with Illumina (up-regulated fold difference was 1.44, p < 0.05), and there was no statistically significant difference for lung tissue samples (p > 0.05). Moreover, MALAT1 gene probe was not available in Illumina database. The complete names and known functions of the four selected proteins are showed in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

(A) the mRNA transcripts level of four proteins (SMOX, NOLC1, HMMR and MALAT1) in NSCLC cell lines and HBECs profiled with Affymetrix microarray. (B) The gene expression level of SMOX, HMMR and NOLC1 in NSCLC cell lines and HBECs/HSAECs profiled with Illumina microarray. (C) The gene expression level of SMOX, HMMR and NOLC1 in 83 NSCLC tissues and paired non-malignant lung tissues profiled with Illumina microarray.

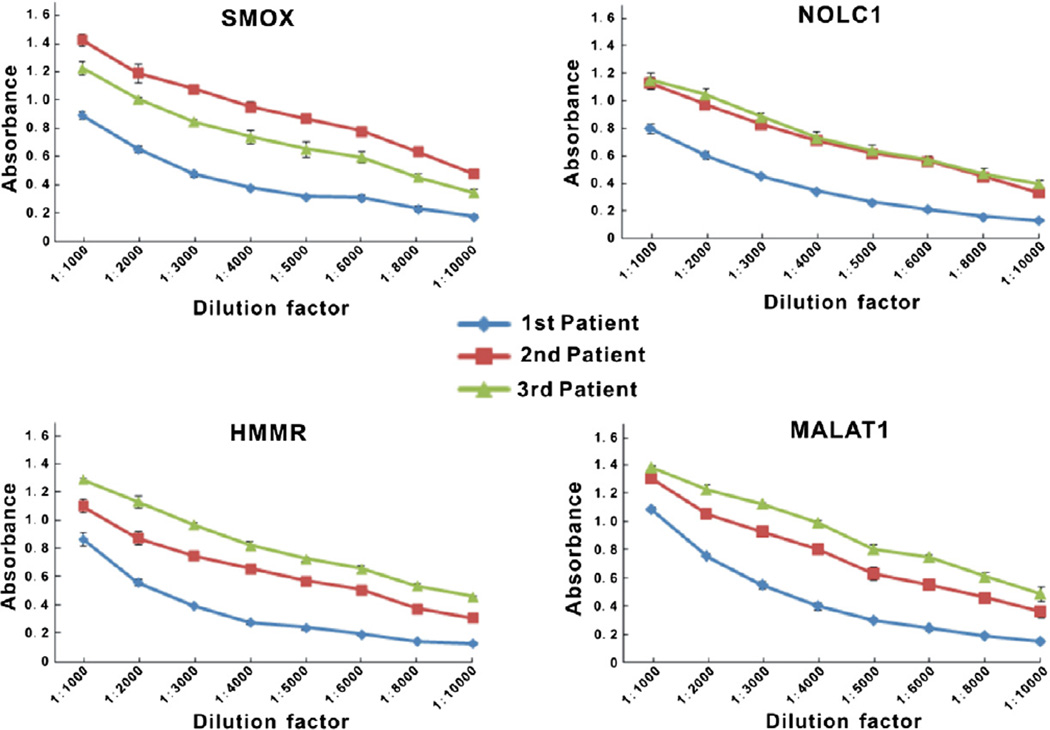

3.4. Antibody affinity test for selected phage displayed tumor-associated proteins

To confirm antibody affinity in the sera of patients for immunogenic phage displayed proteins, serum sample was serially diluted and assayed by ELISA with coated phages displayed SMOX, NOLC1, MALAT1 and HMMR proteins, using T7 empty phages as control. The decreased absorbance values over serial dilutions in all three patients’ sera demonstrated the specificity of antigen-antibody reactions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Antibody affinity for four phage-expressed proteins by ELISA with individual NSCLC serum samples. ELISA assays were developed with SMOX, NOLC1, HMMR and MALAT1 antigen expressing phage and serially diluted (1:1,000 to 1:10,000) three patient serum samples as autoantibodies source. Measurements are evaluated as mean absorbance minus the values of each serum sample assayed against empty T7 phage ± SEM absorbance.

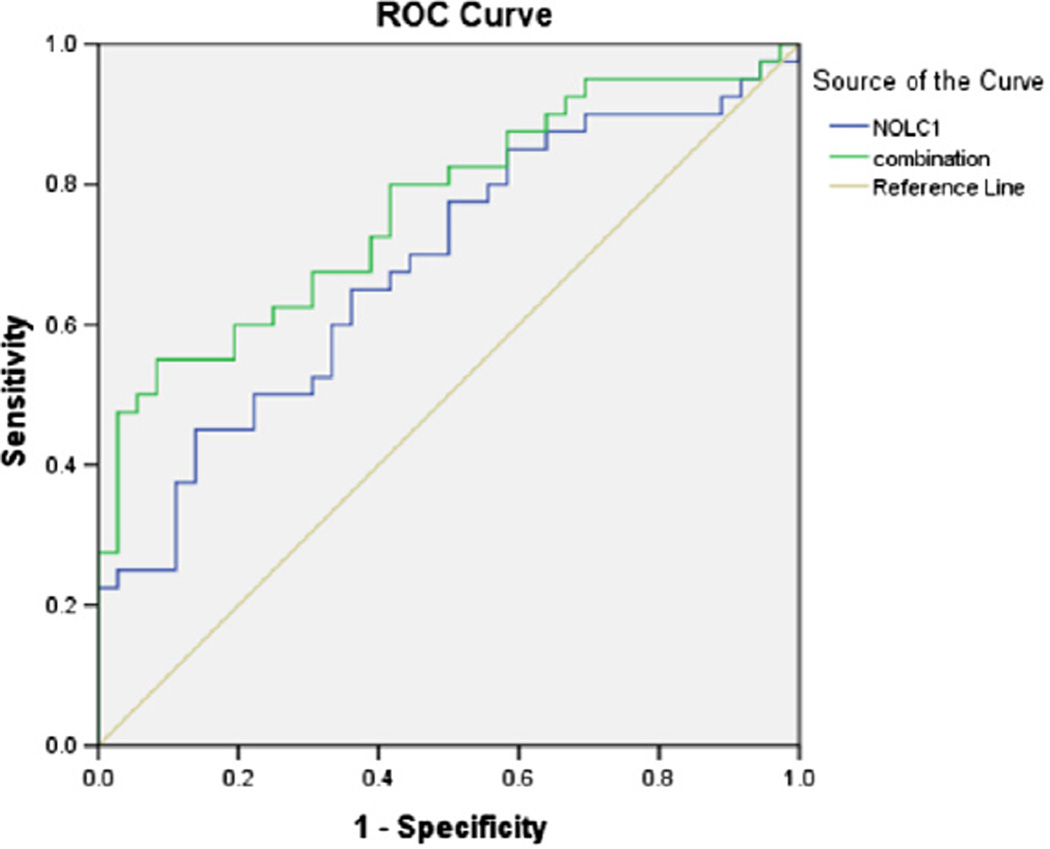

3.5. Evaluate the relevance ratio of combined antibodies versus single antibody

To assess the predictive value of combined antibodies versus single antibody, the four selected phage displayed proteins SMOX, NOLC1, MALAT1 and HMMR were selected for ELISA again to measure the detection rate in 40 individual patient sera and 36 normal sera. Logistic regression was used for processing the data and distinguishing patient serum samples from the 76 serum sample pool.

Firstly, individual marker was estimated. Among the four markers, NOLC1 showed the most significance (p = 0.006) with an area under the curve that equals to 0.684 (Fig. 4), and the predictive accuracy was achieved with 45% sensitivity and 96.2% specificity (Table 7 of the Supplementary Appendix). Next, the combination of four markers was analyzed. We found that for the combined markers the area under the curve increased to 0.767 with 47.5% sensitivity and 97.3% specificity (p = 0.000).

Fig. 4.

Comparisons of the diagnostic value of single antibody versus combined antibodies with logistic regression models.

To further examine the classifiers, leave-one-out cross-validation was performed on the same data used above, and showed that the four combined markers have the most predictive value with 66.67% sensitivity and 60.00% specificity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of the specificity and sensitivity by leave-one-out validation.

| Protein | Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Diagnostic accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOLC1 | 69.4 | 52.5 | 60.5 |

| MALAT1 | 66.7 | 52.5 | 59.2 |

| HMMR | 61.1 | 57.5 | 59.2 |

| SMOX | 50.0 | 62.5 | 56.6 |

| Four Combined | 60.0 | 66.7 | 63.2 |

3.6. Correlation of disease stages and diagnostic accuracies

To evaluate whether our data can be applied to detect early-stage NSCLC cancer patients, we associated them with different stages of the disease. The leave-one-out validation showed 63.6% sensitivity on detection of stage I NSCLC cancer patients, 62.5% sensitivity on stage II patients, 82.4% sensitivity on stage III patients, and 50% sensitivity on stage IV patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diagnostic accuracies in control and different stage patient samples.

| Control (n = 36) | Cancer (n = 40) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV | ||

| Number correct/total | 23/36 | 7/11 | 5/8 | 14/17 | 2/4 |

| Accuracy (%) | 63.9 | 63.6 | 62.5 | 82.4 | 50.0 |

4. Discussion

Numerous studies have demonstrated that metabolites and other proteins released from tumor cells can trigger humoral immune responses in patients [7,8,10,17]. Due to the efficient biological amplification of circulating autoantibodies, they may be present at high concentrations in blood [18]. In addition, they are not subjected to proteolysis like other polypeptides [19], autoantibodies are largely stable in serum for a relatively long period of time (T1/2 of between 7 and 30 days, depending on the subclass of immunoglobulin). These advantages make serum autoantibodies more eligible for tumor detection than the traditional methods. Most importantly, autoantibodies are secreted to the serum much earlier than the observation of clinical symptoms [11,20–22].

Over the past two decades, the most extensively investigated lung cancer serum markers include Cytokeratin 19 Fragment (CYFRA 21-1), Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA), Cancer Antigen 125(CA 125), Neuron-specific Enolase(NSE), Tissue Polypeptide Antigen(TPA), Chromogranin A (CgA) and Cancer Antigen 19-9(CA19-9) [23–28]. However, each marker either showed increased positive rate as the stage advances or insufficient sensitivity and specificity. Thus, none of them can be served as early screening indicator [29,30]. To date, by using proteomic technologies such as SEREX, SERPA, ELISA, and protein microarray, identifying lung cancer circulating autoantibodies and their antigen counterparts has shown the potential of blood tests develop for detecting early stage lung cancer [11,15,21,31,32].

In this study, we used phage display technique and ELISA to detect a set of serum autoantibodies against lung cancer antigens. Firstly, a pool of 5 allogenic sera and 20 autologous obtained from lung cancer patients were used for biopanning process not only to enrich the specific antigen-expressed phage clones but also to exclude the antigens that only interacted with autologous serum and were less reactive to allogenic sera. Meanwhile, we used healthy sera to eliminate natural antibodies that are present in the serum of healthy individuals in the absence of specific immunization with the target antigen, because most natural antibodies are capable of recognizing self and “foreign” antigens [33]. Secondly, 35 unique correct in-frame phage-displayed proteins were identified after sequencing. This low percentage of in-frame proteins in T7 phage library was also found in similar studies [34]. To address the issue, preselecting the library by introducing second antibiotic genes into the expression vector could help to increase the yield [35]. Thirdly, based on the gene expression profiling, four in-frame phage-expressed proteins were selected and assayed by ELISA to confirm the antibody’s affinity. The mRNA transcripts of these four proteins were significantly up-regulated in NSCLC cell lines and tissue samples, which add promises in detection value. In order to assess the potential diagnosis value of selected markers, we also used ELISA screenings to replace newly developed phage peptide microarray [11,36]. Since this method does not need specific high-precision instruments, it makes the screening procedure much easier to handle and more economic as well. And our method showed quit consistent and repeatable.

Furthermore, due to the histological heterogeneity of cancer, different patients are unlikely to respond to the same immunogenic antigens. Even cancers with the same type are composed of different biological subtypes. Therefore, it is very difficult to use a single marker for detecting, whereas utilizing a full panel of multiple markers may greatly enhance diagnosis value. In this study, our statistical analysis revealed the better predictive accuracy with multiple antibodies relative to single antibody. Moreover, these four proteins are involved in multiple cellular functions, such as proliferation, apoptosis, adhesion, and migration, which are associated with tumorigenesis. Two of these four antigens (NOLC1 and MALAT1) have been described in other detection studies in NSCLC [11,15]. When correlating the disease stages with diagnostic accuracies, our data showed 63.6% and 62.5% of sensitivity on detection of stage I and stage II NSCLC cancer patients, respectively, indicating our four-marker predictive assay has the potential value for early-stage cancer screening.

Our study identified a set of serum biomarkers that evoked a humoral immune response in NSCLC patients, based on testing of the sera from patients and normal control subjects that are carefully matched by age, sex and smoking status. Due to a limited size of samples tested, we plan to further validate on additional lung cancer samples plus the control samples of non-lung cancer diseases such as benign lung diseases (COPD and granulomatous lung disease), autoimmune disorders, and other malignancies.

In summary, our study demonstrated the presence of serum antoantibody in lung cancer patient sera and identified four lung cancer related proteins that may be associated with cancer-specific autoantibody production at early stage of tumorigenesis. These four markers may have potential to be used in developing screening tests for detecting early-stage lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Grants from National Eleventh-Five-Year Key Task Project of China (2006BAI02A01), China-Sweden International Cooperative Project (09ZCZDSF04100), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30973384), the 211 Project Innovation Foundation of Tianjin Medical University for Ph.D. Graduation (2009GSI12), EDRN and the Canary Foundation.

The authors thank Dr. John Minna for applying microarray database, and Dr. Yu-An Zhang and Dr. Chunli Shao for helpful writing revision.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.050.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. (2010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spira A, Ettinger DS. Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:379–392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin RW. Tumour-specific immunity against spontaneous rat tumours. Int. J. Cancer. 1966;1:257–264. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910010305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldwin RW. Tumour-associated antigens and tumour-host interactions. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1971;64:1039–1042. doi: 10.1177/003591577106401013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mintz PJ, Kim J, Do KA, et al. Fingerprinting the circulating repertoire of antibodies from cancer patients. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nbt774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finn OJ. Immune response as a biomarker for cancer detection and a lot more. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1288–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan EM. Autoantibodies as reporters identifying aberrant cellular mechanisms in tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1411–1415. doi: 10.1172/JCI14451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caron M, Choquet-Kastylevsky G, Joubert-Caron R. Cancer immunomics using autoantibody signatures for biomarker discovery. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:1115–1122. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R600016-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong L, Coe SP, Stromberg AJ, et al. Profiling tumor-associated antibodies for early detection of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2006;1:513–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang JY, Casiano CA, Peng XX, et al. Enhancement of antibody detection in cancer using panel of recombinant tumor-associated antigens. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:136–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman CJ, Murray A, McElveen JE, et al. Autoantibodies in lung cancer: possibilities for early detection and subsequent cure. Thorax. 2008;63:228–233. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.083592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahin U, Tureci O, Schmitt H, et al. Human neoplasms elicit multiple specific immune responses in the autologous host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11810–11813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong L, Peng X, Hidalgo GE, et al. Identification of circulating antibodies to tumor-associated proteins for combined use as markers of non-small cell lung cancer. Proteomics. 2004;4:1216–1225. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200200679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KS, LaBaer J. The sentinel within: exploiting the immune system for cancer biomarkers. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:1123–1133. doi: 10.1021/pr0500814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belousov PV, Kuprash DV, Nedospasov SA, et al. Autoantibodies to tumor-associated antigens as cancer biomarkers. Curr. Mol. Med. 2010;10:115–122. doi: 10.2174/156652410790963259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desmetz C, Mange A, Maudelonde T, et al. Autoantibody signatures: progress and perspectives for early cancer detection. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2011;15:2013–2024. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman C, Murray A, Chakrabarti J, et al. Autoantibodies in breast cancer: their use as an aid to early diagnosis. Ann. Oncol. 2007;18:868–873. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu J, Choi G, Li L, et al. Occurrence of autoantibodies to Annexin I, 14–3-3 Theta and LAMR1 in prediagnostic lung cancer sera. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5060–5066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madrid MF. Autoantibodies in breast cancer sera: candidate biomarkers and reporters of tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2005;230:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pujol JL, Grenier J, Daures JP, et al. Serum fragment of cytokeratin subunit-19 measured by cyfra-21-1 immunoradiometric assay as a marker of lung-cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pujol L, Molinier O, Ebert W, et al. CYFRA 21-1 is a prognostic determinant in non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a meta-analysis in 2063 patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;90:2097–2105. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulpa J, Wojcik E, Reinfuss M, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, CYFRA 21-1, and neuron-specific enolase in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Clin. Chem. 2002;48:1931–1937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarro G, Perna A, Esposito C. Early diagnosis of lung cancer by detection of tumor liberated protein. J. Cell. Physiol. 2005;203:1–5. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niklinski J, Furman M. Clinical tumour markers in lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 1995;4:129–138. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foa P, Fornier M, Miceli R, et al. Tumour markers CEA, NSE, SCC, TPA and CYFRA 21.1 in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:3613–3618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solassol J, Maudelonde T, Mange A, et al. Clinical relevance of autoantibody detection in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:955–962. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318215a0a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacot W, Lhermitte L, Dossat N, et al. Serum proteomic profiling of lung cancer in high-risk groups and determination of clinical outcomes. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2008;3:840–850. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817e464a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen G, Wang X, Yu J, et al. Autoantibody profiles reveal ubiquilin 1 as a humoral immune response target in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3461–3467. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu LL, Chang WJ, Zhao JF, et al. Development of autoantibody signatures as novel diagnostic biomarkers of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:3760–3768. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1995;7:812–818. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhong L, Ge K, Zu JC, et al. Autoantibodies as potential biomarkers for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10 doi: 10.1186/bcr2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis CA, Benzer S. Generation of cDNA expression libraries enriched for inframe sequences. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:2128–2132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Yu J, Sreekumar A, et al. Autoantibody signatures in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1224–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.