Abstract

Introduction

Adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic type of lung cancer. To address advances in oncology, molecular biology, pathology, radiology, and surgery of lung adenocarcinoma, an international multidisciplinary classification was sponsored by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. This new adenocarcinoma classification is needed to provide uniform terminology and diagnostic criteria, especially for bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC), the overall approach to small nonresection cancer specimens, and for multidisciplinary strategic management of tissue for molecular and immunohistochemical studies.

Methods

An international core panel of experts representing all three societies was formed with oncologists/pulmonologists, pathologists, radiologists, molecular biologists, and thoracic surgeons. A systematic review was performed under the guidance of the American Thoracic Society Documents Development and Implementation Committee. The search strategy identified 11,368 citations of which 312 articles met specified eligibility criteria and were retrieved for full text review. A series of meetings were held to discuss the development of the new classification, to develop the recommendations, and to write the current document. Recommendations for key questions were graded by strength and quality of the evidence according to the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach.

Results

The classification addresses both resection specimens, and small biopsies and cytology. The terms BAC and mixed subtype adenocarcinoma are no longer used. For resection specimens, new concepts are introduced such as adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA) for small solitary adenocarcinomas with either pure lepidic growth (AIS) or predominant lepidic growth with ≤5 mm invasion (MIA) to define patients who, if they undergo complete resection, will have 100% or near 100% disease-specific survival, respectively. AIS and MIA are usually nonmucinous but rarely may be mucinous. Invasive adenocarcinomas are classified by predominant pattern after using comprehensive histologic subtyping with lepidic (formerly most mixed subtype tumors with nonmucinous BAC), acinar, papillary, and solid patterns; micropapillary is added as a new histologic subtype. Variants include invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (formerly mucinous BAC), colloid, fetal, and enteric adenocarcinoma. This classification provides guidance for small biopsies and cytology specimens, as approximately 70% of lung cancers are diagnosed in such samples. Non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs), in patients with advanced-stage disease, are to be classified into more specific types such as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, whenever possible for several reasons: (1) adenocarcinoma or NSCLC not otherwise specified should be tested for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations as the presence of these mutations is predictive of responsiveness to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors, (2) adenocarcinoma histology is a strong predictor for improved outcome with pemetrexed therapy compared with squamous cell carcinoma, and (3) potential life-threatening hemorrhage may occur in patients with squamous cell carcinoma who receive bevacizumab. If the tumor cannot be classified based on light microscopy alone, special studies such as immunohistochemistry and/or mucin stains should be applied to classify the tumor further. Use of the term NSCLC not otherwise specified should be minimized.

Conclusions

This new classification strategy is based on a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma that incorporates clinical, molecular, radiologic, and surgical issues, but it is primarily based on histology. This classification is intended to support clinical practice, and research investigation and clinical trials. As EGFR mutation is a validated predictive marker for response and progression-free survival with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced lung adenocarcinoma, we recommend that patients with advanced adenocarcinomas be tested for EGFR mutation. This has implications for strategic management of tissue, particularly for small biopsies and cytology samples, to maximize high-quality tissue available for molecular studies. Potential impact for tumor, node, and metastasis staging include adjustment of the size T factor according to only the invasive component (1) pathologically in invasive tumors with lepidic areas or (2) radiologically by measuring the solid component of part-solid nodules.

Keywords: Lung, Adenocarcinoma, Classification, Histologic, Pathology, Oncology, Pulmonary, Radiology, Computed tomography, Molecular, EGFR, KRAS, EML4-ALK, Gene profiling, Gene amplification, Surgery, Limited resection, Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, Lepidic, Acinar, Papillary, Micropapillary, Solid, Adenocarcinoma in situ, Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, Colloid, Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, Enteric, Fetal, Signet ring, Clear cell, Frozen section, TTF-1, p63

RATIONALE FOR A CHANGE IN THE APPROACH TO CLASSIFICATION OF LUNG ADENOCARCINOMA

Lung cancer is the most frequent cause of major cancer incidence and mortality worldwide.1,2 Adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic subtype of lung cancer in most countries, accounting for almost half of all lung cancers.3 A widely divergent clinical, radiologic, molecular, and pathologic spectrum exists within lung adenocarcinoma. As a result, confusion exists, and studies are difficult to compare. Despite remarkable advances in understanding of this tumor in the past decade, there remains a need for universally accepted criteria for adenocarcinoma subtypes, in particular tumors formerly classified as bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC).4,5 As enormous resources are being spent on trials involving molecular and therapeutic aspects of adenocarcinoma of the lung, the development of standardized criteria is of great importance and should help advance the field, increasing the impact of research, and improving patient care. This classification is needed to assist in determining patient therapy and predicting outcome.

NEED FOR A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS OF LUNG ADENOCARCINOMA

One of the major outcomes of this project is the recognition that the diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma requires a multidisciplinary approach. The classifications of lung cancer published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1967, 1981, and 1999 were written primarily by pathologists for pathologists.5–7 Only in the 2004 revision, relevant genetics and clinical information were introduced.4 Nevertheless, because of remarkable advances over the last 6 years in our understanding of lung adenocarcinoma, particularly in area of medical oncology, molecular biology, and radiology, there is a pressing need for a revised classification, based not on pathology alone, but rather on an integrated multidisciplinary platform. In particular, there are two major areas of interaction between specialties that are driving the need for our multidisciplinary approach to classification of lung adenocarcinoma: (1) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, recent progress in molecular biology and oncology has led to (a) discovery of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation and its prediction of response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in adenocarcinoma patients8–11 and (b) the requirement to exclude a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma to determine eligibility patients for treatment with pemetrexed, (because of improved efficacy)12–15 or bevacizumab (because of toxicity)16,17 and (2) the emergence of radiologic-pathologic correlations between ground-glass versus solid or mixed opacities seen by computed tomography (CT) and BAC versus invasive growth by pathology have opened new opportunities for imaging studies to be used by radiologists, pulmonologists, and surgeons for predicting the histologic subtype of adenocarcinomas,18–21 patient prognosis,18–23 and improve preoperative assessment for choice of timing and type of surgical intervention.18–26

Although histologic criteria remain the foundation of this new classification, this document has been developed by pathologists in collaboration with clinical, radiology, molecular, and surgical colleagues. This effort has led to the development of terminology and criteria that not only define pathologic entities but also communicate critical information that is relevant to patient management (Tables 1 and 2). The classification also provides recommendations on strategic handling of specimens to optimize the amount of information to be gleaned. The goal is not only longer to solely provide the most accurate diagnosis but also to manage the tissue in a way that immunohistochemical and/or molecular studies can be performed to obtain predictive and prognostic data that will lead to improvement in patient outcomes.

TABLE 1.

IASLC/ATS/ERS Classification of Lung Adenocarcinoma in Resection Specimens

| Preinvasive lesions |

| Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia |

| Adenocarcinoma in situ (≤3 cm formerly BAC) |

| Nonmucinous |

| Mucinous |

| Mixed mucinous/nonmucinous |

| Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (≤3 cm lepidic predominant tumor with ≤5 mm invasion) |

| Nonmucinous |

| Mucinous |

| Mixed mucinous/nonmucinous |

| Invasive adenocarcinoma |

| Lepidic predominant (formerly nonmucinous BAC pattern, with >5 mm invasion) |

| Acinar predominant |

| Papillary predominant |

| Micropapillary predominant |

| Solid predominant with mucin production |

| Variants of invasive adenocarcinoma |

| Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (formerly mucinous BAC) |

| Colloid |

| Fetal (low and high grade) |

| Enteric |

BAC, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma; IASLC, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer; ATS, American Thoracic Society; ERS, European Respiratory Society.

TABLE 2.

Proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS Classification for Small Biopsies/Cytology

| 2004 WHO Classification | SMALL BIOPSY/CYTOLOGY: IASLC/ATS/ERS |

|---|---|

| ADENOCARCINOMA Mixed subtype Acinar Papillary Solid |

Morphologic adenocarcinoma patterns clearly present: Adenocarcinoma, describe identifiable patterns present (including micropapillary pattern not included in 2004 WHO classification) Comment: If pure lepidic growth - mention an invasive component cannot be excluded in this small specimen |

| Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (nonmucinous) | Adenocarcinoma with lepidic pattern (if pure, add note: an invasive component cannot be excluded) |

| Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (mucinous) | Mucinous adenocarcinoma (describe patterns present) |

| Fetal | Adenocarcinoma with fetal pattern |

| Mucinous (colloid) | Adenocarcinoma with colloid pattern |

| Signet ring | Adenocarcinoma with (describe patterns present) and signet ring features |

| Clear cell | Adenocarcinoma with (describe patterns present) and clear cell features |

| No 2004 WHO counterpart - most will be solid adenocarcinomas |

Morphologic adenocarcinoma patterns not present (supported by special stains): Non-small cell carcinoma, favor adenocarcinoma |

| SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA Papillary Clear cell Small cell Basaloid |

Morphologic squamous cell patterns clearly present: Squamous cell carcinoma |

| No 2004 WHO counterpart |

Morphologic squamous cell patterns not present (supported by stains): Non-small cell carcinoma, favor squamous cell carcinoma |

| SMALL CELL CARCINOMA | Small cell carcinoma |

| LARGE CELL CARCINOMA | Non-small cell carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) |

| Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) | Non-small cell carcinoma with neuroendocrine (NE) morphology (positive NE markers), possible LCNEC |

| Large cell carcinoma with NE morphology (LCNEM) | Non-small cell carcinoma with NE morphology (negative NE markers) - see comment Comment: This is a non-small cell carcinoma where LCNEC is suspected, but stains failed to demonstrate NE differentiation. |

| ADENOSQUAMOUS CARCINOMA |

Morphologic squamous cell and adenocarcinoma patterns present: Non-small cell carcinoma, with squamous cell and adenocarcinoma patterns Comment: this could represent adenosquamous carcinoma. |

| No counterpart in 2004 WHO classification |

Morphologic squamous cell or adenocarcinoma patterns not present but immunostains favor separate glandular and adenocarcinoma components Non-small cell carcinoma, NOS, (specify the results of the immunohistochemical stains and the interpretation) Comment: this could represent adenosquamous carcinoma. |

| Sarcomatoid carcinoma | Poorly differentiated NSCLC with spindle and/or giant cell carcinoma (mention if adenocarcinoma or squamous carcinoma are present) |

IASLC, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer; ATS, American Thoracic Society; ERS, European Respiratory Society; WHO, World Health Organization: NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; IHC, immunohistochemistry; TTF, thyroid transcription factor.

For the first time, this classification addresses an approach to small biopsies and cytology in lung cancer diagnosis (Table 2). Recent data regarding EGFR mutation predicting responsiveness to EGFR-TKIs,8–11 toxicities,16 and therapeutic efficacy12–15 have established the importance of distinguishing squamous cell carcinoma from adenocarcinoma and non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) not otherwise specified (NOS) in patients with advanced lung cancer. Approximately 70% of lung cancers are diagnosed and staged by small biopsies or cytology rather than surgical resection specimens, with increasing use of transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA), endobronchial ultrasound-guided TBNA and esophageal ultrasound-guided needle aspiration.27 Within the NSCLC group, most pathologists can identify well- or moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas, but specific diagnoses are more difficult with poorly differentiated tumors. Nevertheless, in small biopsies and/or cytology specimens, 10 to 30% of specimens continue to be diagnosed as NSCLC-NOS.13,28,29

Proposed terminology to be used in small biopsies is summarized in Table 2. Pathologists need to minimize the use of the term NSCLC or NSCLC-NOS on small samples and aspiration and exfoliative cytology, providing as specific a histologic classification as possible to facilitate the treatment approach of medical oncologists.30

Unlike previous WHO classifications where the primary diagnostic criteria for as many tumor types as possible were based on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) examination, this classification emphasizes the use and integration of immunohistochemical (i.e., thyroid transcription factor [TTF-1]/p63 staining), histochemical (i.e., mucin staining), and molecular studies, as specific therapies are driven histologic subtyping. Although these techniques should be used whenever possible, it is recognized that this may not always be possible, and thus, a simpler approach is also provided when only H&E-stained slides are available, so this classification may be applicable even in a low resource setting.

METHODOLOGY

Objectives

This international multidisciplinary classification has been produced as a collaborative effort by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society. The purpose is to provide an integrated clinical, radiologic, molecular, and pathologic approach to classification of the various types of lung adenocarcinoma that will help to define categories that have distinct clinical, radiologic, molecular, and pathologic characteristics. The goal is to identify prognostic and predictive factors and therapeutic targets.

Participants

Panel members included thoracic medical oncologists, pulmonologists, radiologists, molecular biologists, thoracic surgeons, and pathologists. The supporting associations nominated panel members. The cochairs were selected by the IASLC. Panel members were selected because of special interest and expertise in lung adenocarcinoma and to provide an international and multidisciplinary representation. The panel consisted of a core group (author list) and a reviewer group (Appendix 1, see Supplemental Digital Content 1 available at http://links.lww.com/JTO/A59, affiliations for coauthors are listed in appendix).

Evidence

The panel performed a systematic review with guidance by members of the ATS Documents Development and Implementation Committee. Key questions for this project were generated by each specialty group, and a search strategy was developed (Appendix 2, see Supplemental Digital Content 2 available at http://links.lww.com/JTO/A60). Searches were performed in June 2008 with an update in June 2009 resulting in 11,368 citations. These were reviewed to exclude articles that did not have any relevance to the topic of lung adenocarcinoma classification. The remaining articles were evaluated by two observers who rated them by a predetermined set of eligibility criteria using an electronic web-based survey program (www.surveymonkey.com) to collect responses.31 This process narrowed the total number of articles to 312 that were reviewed in detail for a total of 141 specific features, including 17 study characteristics, 35 clinical, 48 pathologic, 16 radiologic, 16 molecular, and nine surgical (Appendix 2). These 141 features were summarized in an electronic database that was distributed to members of the core panel, including the writing committee. Articles chosen for specific data summaries were reviewed, and based on analysis of tables from this systematic review, recommendations were made according to the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE).32–37 Throughout the rest of the document, the term GRADE (spelled in capital letters) must be distinguished from histologic grade, which is a measure of pathologic tumor differentiation. The GRADE system has two major components: (1) grading the strength of the recommendation and (2) evaluating the quality of the evidence.32 The strength of recommendations is based on weighing estimates of benefits versus downsides. Evidence was rated as high, moderate, or low or very low.32 The quality of the evidence expresses the confidence in an estimate of effect or an association and whether it is adequate to support a recommendation. After review of all articles, a writing committee met to develop the recommendations with each specialty group proposing the recommendations, votes for or against the recommendation, and modifications were conducted after multidisciplinary discussion. If randomized trials were available, we started by assuming high quality but down-graded the quality when there were serious methodological limitations, indirectness in population, inconsistency in results, imprecision in estimates, or a strong suspicion of publication bias. If well-done observational studies were available, low-quality evidence was assumed, but the quality was upgraded when there was a large treatment effect or a large association, all plausible residual confounders would diminish the effects, or if there was a dose-response gradient.36 We developed considerations for good practice related to interventions that usually represent necessary and standard procedures of health care system—such as history taking and physical examination helping patients to make informed decisions, obtaining written consent, or the importance of good communication—when we considered them helpful. In that case, we did not perform a grading of the quality of evidence or strength of the recommendations.38

Meetings

Between March 2008 and December 2009, a series of meetings were held, mostly at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in New York, NY, to discuss issues related to lung adenocarcinoma classification and to formulate this document. The core group established a uniform and consistent approach to the proposed types of lung adenocarcinoma.

Validation

Separate projects were initiated by individuals involved with this classification effort in an attempt to develop data to test the proposed system. These included projects on small biopsies,39,40 histologic grading,41–43 stage I adenocarcinomas,44 small adenocarcinomas from Japan, international multiple pathologist project on reproducibility of recognizing major histologic patterns of lung adenocarcinoma,45 molecular-histologic correlations, and radiologic-pathologic correlation focused on adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA).

The new proposals in this classification are based on the best available evidence at the time of writing this document. Nevertheless, because of the lack of universal diagnostic criteria in the literature, there is a need for future validation studies based on these standardized pathologic criteria with clinical, molecular, radiologic, and surgical correlations.

PATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

Histopathology is the backbone of this classification, but lung cancer diagnosis is a multidisciplinary process requiring correlation with clinical, radiologic, molecular, and surgical information. Because of the multidisciplinary approach in developing this classification, we are recommending significant changes that should improve the diagnosis and classification of lung adenocarcinoma, resulting in therapeutic benefits.

Even after publication of the 1999 and 2004 WHO classifications,4,5 the former term BAC continues to be used for a broad spectrum of tumors including (1) solitary small noninvasive peripheral lung tumors with a 100% 5-year survival,46 (2) invasive adenocarcinomas with minimal invasion that have approximately 100% 5-year survival,47,48 (3) mixed subtype invasive adenocarcinomas,49 –53 (4) mucinous and nonmucinous subtypes of tumors formerly known as BAC,50 –52,54,55 and (5) widespread advanced disease with a very low survival rate.4,5 The consequences of confusion from the multiple uses of the former BAC term in the clinical and research arenas have been the subject of many reviews and editorials and are addressed throughout this document.55– 61

Pathology Recommendation 1

We recommend discontinuing the use of the term “BAC.” Strong recommendation, low-quality evidence.

Throughout this article, the term BAC (applicable to multiple places in the new classification, Table 3), will be referred to as “former BAC.” We understand this will be a major adjustment and suggest initially that when the new proposed terms are used, it will be accompanied in parentheses by “(formerly BAC).” This transition will impact not only clinical practice and research but also cancer registries future analyses of registry data.

TABLE 3.

Categories of New Adenocarcinoma Classification Where Former BAC Concept was Used

|

BAC, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma.

CLASSIFICATION FOR RESECTION SPECIMENS

Multiple studies have shown that patients with small solitary peripheral adenocarcinomas with pure lepidic growth may have 100% 5-year disease-free survival.46,62–68 In addition, a growing number of articles suggest that patients with lepidic predominant adenocarcinomas (LPAs) with minimal invasion may also have excellent survival.47,48 Recent work has demonstrated that more than 90% of lung adenocarcinomas fall into the mixed subtype according to the 2004 WHO classification, so it has been proposed to use comprehensive histologic subtyping to make a semiquantitative assessment of the percentages of the various histologic components: acinar, papillary, micropapillary, lepidic, and solid and to classify tumors according to the predominant histologic subtype.69 This has demonstrated an improved ability to address the complex histologic heterogeneity of lung adenocarcinomas and to improve molecular and prognostic correlations.69

The new proposed lung adenocarcinoma classification for resected tumors is summarized in Table 1.

Preinvasive Lesions

In the 1999 and 2004 WHO classifications, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) was recognized as a preinvasive lesion for lung adenocarcinoma. This is based on multiple studies documenting these lesions as incidental findings in the adjacent lung parenchyma in 5 to 23% of resected lung adenocarcinomas70–74 and a variety of molecular findings that demonstrate a relationship to lung adenocarcinoma including clonality,75,76 KRAS mutation,77,78 KRAS polymorphism,79 EGFR mutation,80 p53 expression,81 loss of heterozygosity,82 methylation,83 telomerase overexpression,84 eukaryotic initiation factor 4E expression,85 epigenetic alterations in the Wnt pathway,86 and FHIT expression.87 Depending on the extensiveness of the search, AAH may be multiple in up to 7% of resected lung adenocarcinomas.71,88

A major change in this classification is the official recognition of AIS, as a second preinvasive lesion for lung adenocarcinoma in addition to AAH. In the category of preinvasive lesions, AAH is the counterpart to squamous dysplasia and AIS the counterpart to squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia

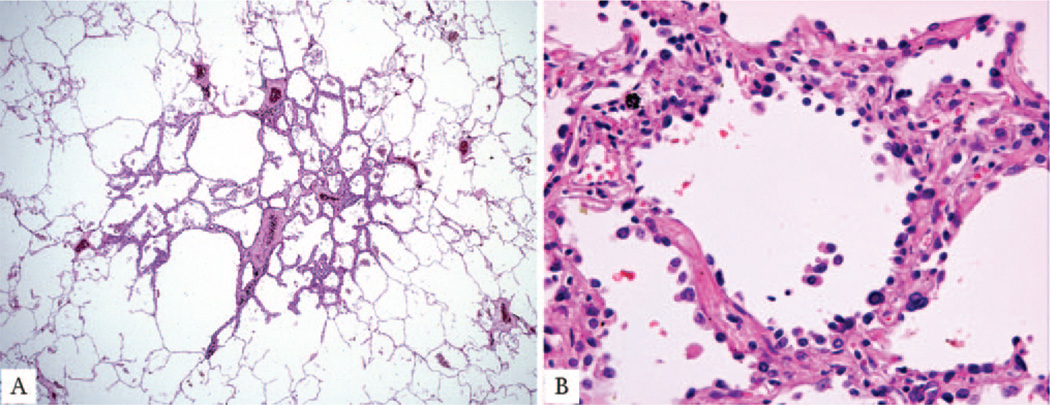

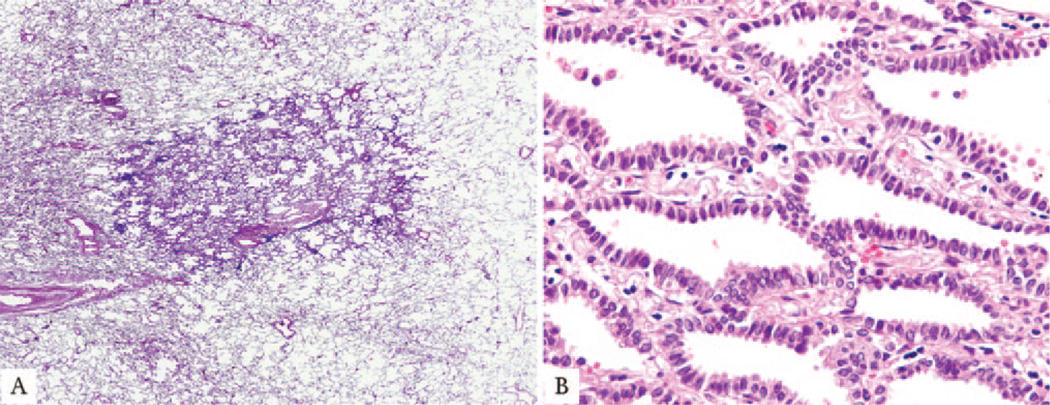

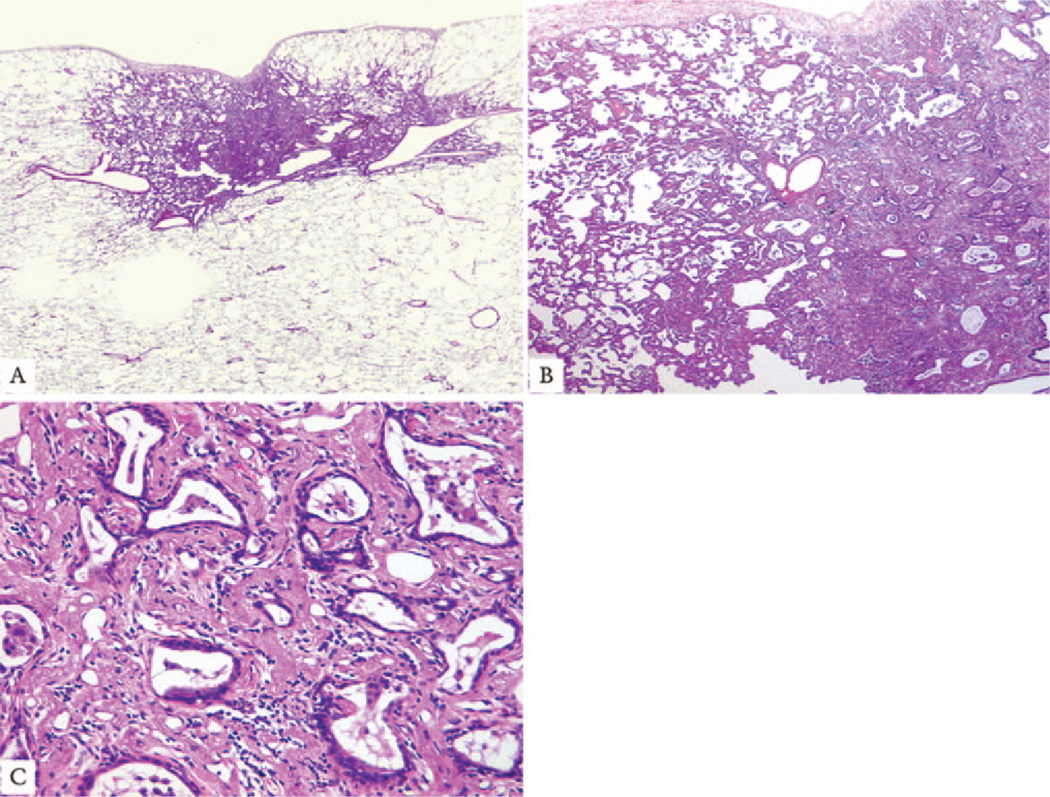

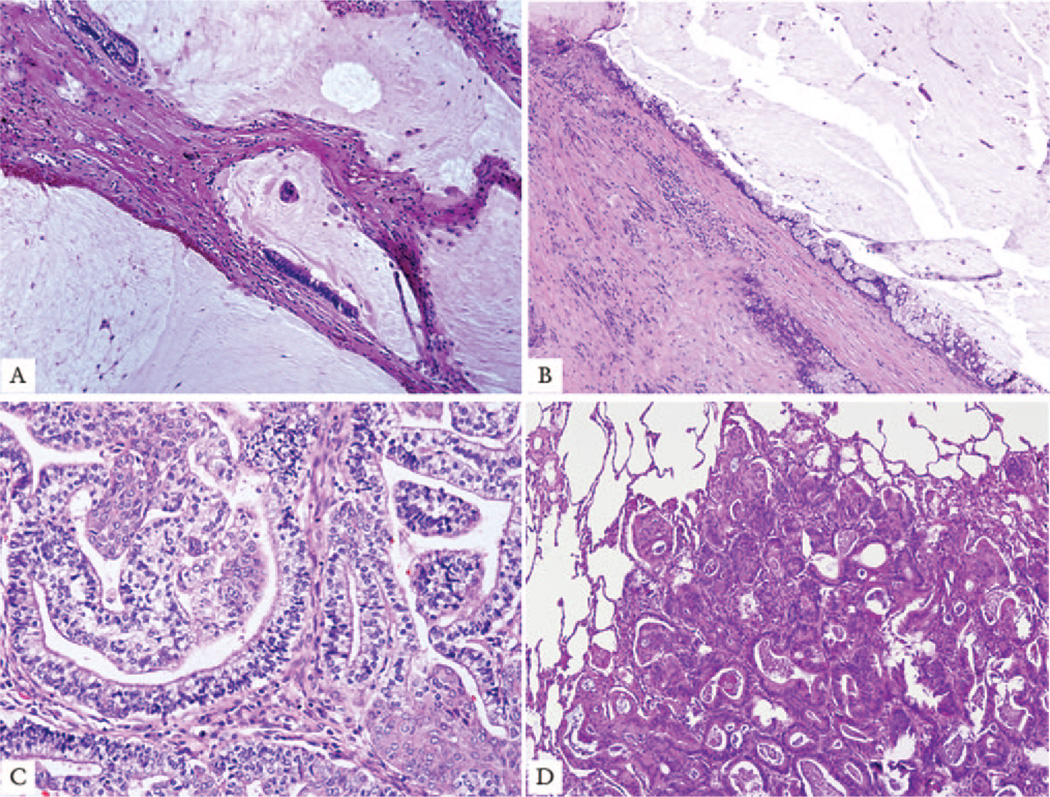

AAH is a localized, small (usually 0.5 cm or less) proliferation of mildly to moderately atypical type II pneumocytes and/or Clara cells lining alveolar walls and sometimes, respiratory bronchioles (Figures 1A, B).4,89,90 Gaps are usually seen between the cells, which consist of rounded, cuboidal, low columnar, or “peg” cells with round to oval nuclei (Figure 1B). Intranuclear inclusions are frequent. There is a continuum of morphologic changes between AAH and AIS.4,89,90 A spectrum of cellularity and atypia occurs in AAH. Although some have classified AAH into low- and high-grade types,84,91 grading is not recommended.4 Distinction between more cellular and atypical AAH and AIS can be difficult histologically and impossible cytologically.

Figure 1.

Atypical adenomatous hyperplasia. A, This 3-mm nodular lesion consists of atypical pneumocytes proliferating along preexisting alveolar walls. There is no invasive component. B, The slightly atypical pneumocytes are cuboidal and show gaps between the cells. Nuclei are hyperchromatic, and a few show nuclear enlargement and multinucleation.

AIS, Nonmucinous, and/or Mucinous

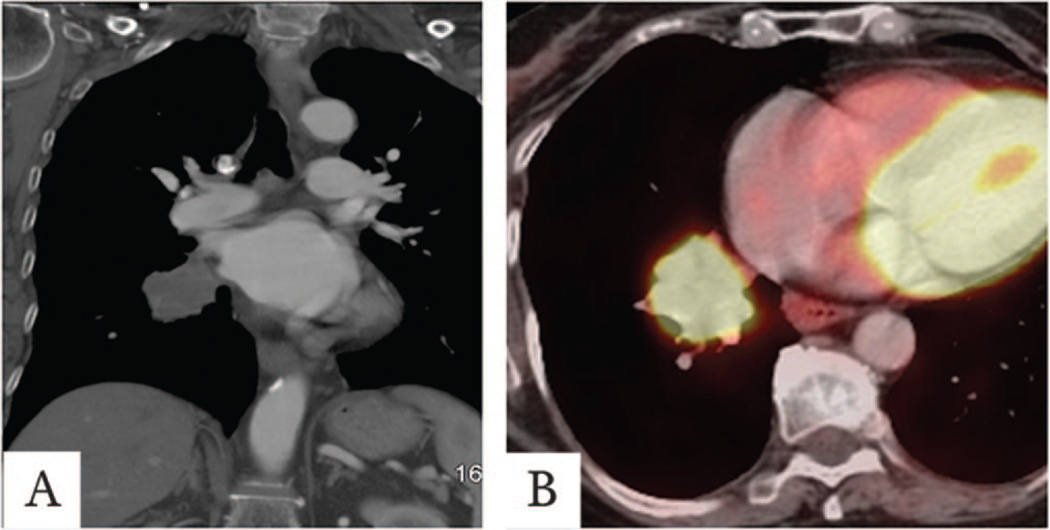

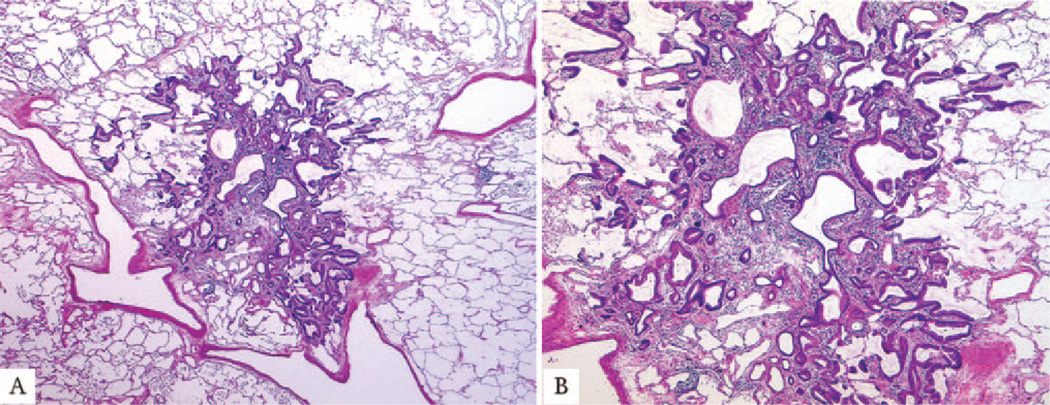

AIS (one of the lesions formerly known as BAC) is a localized small (≤3 cm) adenocarcinoma with growth restricted to neoplastic cells along preexisting alveolar structures (lepidic growth), lacking stromal, vascular, or pleural invasion. Papillary or micropapillary patterns and intraalveolar tumor cells are absent. AIS is subdivided into nonmucinous and mucinous variants. Virtually, all cases of AIS are nonmucinous, consisting of type II pneumocytes and/or Clara cells (Figures 2A, B). There is no recognized clinical significance to the distinction between type II or Clara cells, so this morphologic separation is not recommended. The rare cases of mucinous AIS consist of tall columnar cells with basal nuclei and abundant cytoplasmic mucin; sometimes they resemble goblet cells (Figures 3A, B). Nuclear atypia is absent or inconspicuous in both nonmucinous and mucinous AIS (Figures 2B and 3B). Septal widening with sclerosis is common in AIS, particularly the nonmucinous variant.

Figure 2.

Nonmucinous adenocarcinoma in situ. A, This circumscribed nonmucinous tumor grows purely with a lepidic pattern. No foci of invasion or scarring are seen. B, The tumor shows atypical pneumocytes proliferating along the slightly thickened, but preserved, alveolar walls.

Figure 3.

Mucinous adenocarcinoma in situ. A, This mucinous AIS consists of a nodular proliferation of mucinous columnar cells growing in a purely lepidic pattern. Although there is a small central scar, no stromal or vascular invasion is seen. B, The tumor cells consist of cuboidal to columnar cells with abundant apical mucin and small basally oriented nuclei. AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ.

Tumors that meet criteria for AIS have formerly been classified as BAC according to the strict definition of the 1999 and 2004 WHO classifications and type A and type B adenocarcinoma according to the 1995 Noguchi classification.4,46 Multiple observational studies on solitary lung adenocarcinomas with pure lepidic growth, smaller than either 2 or 3 cm have documented 100% disease-free survival.46,62–68 Although most of these tumors are nonmucinous, 2 of the 28 tumors reported by Noguchi as types A and B in the 1995 study were mucinous.46 Small size (≤3 cm) and a discrete circumscribed border are important to exclude cases with miliary spread into adjacent lung parenchyma and/or lobar consolidation, particularly for mucinous AIS.

Pathology Recommendation 2

For small (≤3 cm), solitary adenocarcinomas with pure lepidic growth, we recommend the term “Adenocarcinoma in situ” that defines patients who should have 100% disease-specific survival, if the lesion is completely resected (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence).

Remark: Most AIS are nonmucinous, rarely are they mucinous.

MIA, Nonmucinous, and/or Mucinous

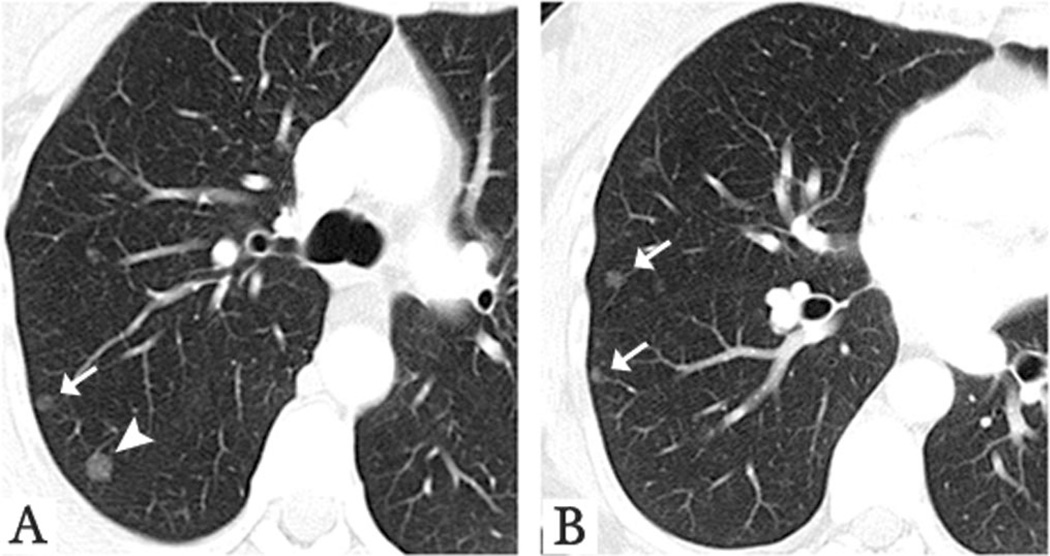

MIA is a small, solitary adenocarcinoma (≤3 cm), with a predominantly lepidic pattern and ≤5 mm invasion in greatest dimension in any one focus.47,48,92 MIA is usually nonmucinous (Figures 4A–C) but rarely may be mucinous (Figures 5A, B).44 MIA is, by definition, solitary and discrete. The criteria for MIA can be applied in the setting of multiple tumors only if the other tumors are regarded as synchronous primaries rather than intrapulmonary metastases.

Figure 4.

Nonmucinous minimally invasive adenocarcinoma. A, This subpleural adenocarcinoma tumor consists primarily of lepidic growth with a small (<0.5 cm) central area of invasion. B, To the left is the lepidic pattern and on the right is an area of acinar invasion. C, These acinar glands are invading in the fibrous stroma.

Figure 5.

Mucinous minimally invasive adenocarcinoma. A, This mucinous MIA consists of a tumor showing lepidic growth and a small (<0.5 cm) area of invasion. B, The tumor cells consist of mucinous columnar cells growing mostly in a lepidic pattern along the surface of alveolar walls. The tumor invades the areas of stromal fibrosis in an acinar pattern. MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma.

The invasive component to be measured in MIA is defined as follows: (1) histological subtypes other than a lepidic pattern (i.e., acinar, papillary, micropapillary, and/or solid) or (2) tumor cells infiltrating myofibroblastic stroma. MIA is excluded if the tumor (1) invades lymphatics, blood vessels, or pleura or (2) contains tumor necrosis. If multiple microinvasive areas are found in one tumor, the size of the largest invasive area should be measured in the largest dimension, and it should be ≤5 mm in size. The size of invasion is not the summation of all such foci, if more than one occurs. If the manner of histologic sectioning of the tumor makes it impossible to measure the size of invasion, an estimate of invasive size can be made by multiplying the total percentage of the invasive (nonlepidic) components times the total tumor size.

Evidence for a category of MIA with 100% disease-free survival can be found in the 1995 article by Noguchi et al., where vascular or pleural invasion was found in 10% of the small solitary lung adenocarcinomas that otherwise met the former definition of pure BAC. Even these focally invasive tumors also showed 100% disease-free survival.46 Subsequent articles by Suzuki et al. and Sakurai et al.19,21 defined subsets of small lung adenocarcinomas with 100% disease-free survival using scar size less than 5 mm and stromal invasion in the area of bronchioloalveolar growth, respectively. More recently, articles by Yim et al., Borczuk et al., and Maeshima et al.47,48,92 have described patients with MIA defined similar to the above criteria, and these have demonstrated near 100% disease specific or very favorable overall survival. There is very limited data regarding mucinous MIA; however, this seems to exist. A mucinous MIA with a minor mixture of a nonmucinous component is being reported.44 The recent report by Sawada et al.93 of localized mucinous BAC may have included a few cases of mucinous AIS or MIA, but details of the pathology are not specific enough to be certain. A recent series of surgically resected solitary mucinous BAC did not document histologically whether focal invasion was present or not, so AIS versus MIA status cannot be determined, but all eight patients with tumors measuring ≤3 cm had 100% overall 5-year survival rates.94 Presentation as a solitary mass, small size, and a discrete circumscribed border is important to exclude cases of miliary involvement of adjacent lung parenchyma and/or lobar consolidation, particularly for mucinous AIS.

Pathology Recommendation 3

For small (≤3 cm), solitary, adenocarcinomas with predominant lepidic growth and small foci of invasion measuring ≤0.5 cm, we recommend a new concept of “Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma” to define patients who have near 100%, disease-specific survival, if completely resected (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Remark: Most MIA are nonmucinous, rarely are they mucinous.

Tumor Size and Specimen Processing Issues for AIS and MIA

The diagnosis of AIS or MIA cannot be firmly established without entire histologic sampling of the tumor. If tumor procurement is performed, it should be done strategically as discussed in the molecular section.

Because most of the literature on the topic of AIS and MIA deal with tumors 2.0 or 3.0 cm or less, there is insufficient evidence to support that 100% disease-free survival can occur in completely resected, solitary tumors suspected to be AIS or MIA that are larger than 3.0 cm. Until data validate 100% disease-free survival for completely resected, solitary, adenocarcinomas larger than 3.0 cm suspected to be AIS or MIA after complete sampling, the term “lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma, suspect AIS or MIA” is suggested. In such a tumor larger than 3.0 cm, particularly if it has not been completely sampled, the term “lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma” is best applied with a comment that the clinical behavior is uncertain and/or that an invasive component cannot be excluded.

Invasive Adenocarcinoma

As invasive adenocarcinomas represent more than 70 to 90% of surgically resected lung cases, one of the most important aspects of this classification is to present a practical way to address these tumors that are composed of a complex heterogeneous mixture of histologic subtypes. This complex mixture of histologic subtypes has presented one of the greatest challenges to classification of invasive lung adenocarcinomas. In recent years, multiple independent research groups have begun to classify lung adenocarcinomas according to the most predominant subtype.43,44,69,95–102 This approach provides better stratification of the “mixed subtype” lung adenocarcinomas according to the 1999/2004 WHO Classifications and has allowed for novel correlations between histologic subtypes and both molecular and clinical features.43,44,69,95–102

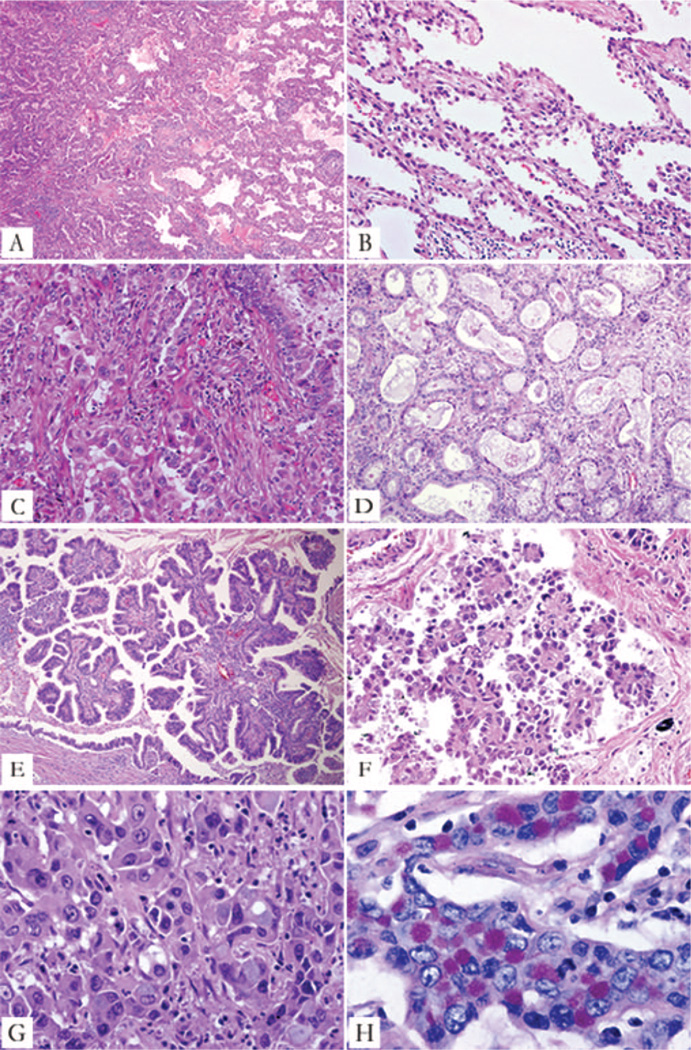

In the revised classification, the term “predominant” is appended to all categories of invasive adenocarcinoma, as most of these tumors consist of mixtures of the histologic subtypes (Figures 6A–C). This replaces the use of the term adenocarcinoma, mixed subtype. Semiquantitative recording of the patterns in 5% increments encourages the observer to identify all patterns that may be present, rather than focusing on a single pattern (i.e., lepidic growth). This method provides a basis for choosing the predominant pattern. Although most previous studies on this topic used 10% increments, using 5% allows for greater flexibility in choosing a predominant subtype when tumors have two patterns with relatively similar percentages; it also avoids the need to use 10% for small amounts of components that may be prognostically important such as micropapillary or solid patterns. Recording of these percentages also makes it clear to the reader of a report when a tumor has relatively even mixtures of several patterns versus a single dominant pattern. In addition, it provides a way to compare the histology of multiple adenocarcinomas (see later).102 This approach may also provide a basis for architectural grading of lung adenocarcinomas.43 A recent reproducibility study of classical and difficult selected images of the major lung adenocarcinoma subtypes circulated among a panel of 26 expert lung cancer pathologists documented kappa values of 0.77 ± 0.07 and 0.38 ± 0.14, respectively.45 This study did not test recognition of predominant subtype.

Figure 6.

Major histologic patterns of invasive adenocarcinoma. A, Lepidic predominant pattern with mostly lepidic growth (right) and a smaller area of invasive acinar adenocarcinoma (left). B, Lepidic pattern consists of a proliferation type II pneumocytes and Clara cells along the surface alveolar walls. C, Area of invasive acinar adenocarcinoma (same tumor as in A and B). D, Acinar adenocarcinoma consists of round to oval-shaped malignant glands invading a fibrous stroma. E, Papillary adenocarcinoma consists of malignant cuboidal to columnar tumor cells growing on the surface of fibrovascular cores. F, Micropapillary adenocarcinoma consists of small papillary clusters of glandular cells growing within this airspace, most of which do not show fibrovascular cores. G, Solid adenocarcinoma with mucin consisting of sheets of tumor cells with abundant cytoplasm and mostly vesicular nuclei with several conspicuous nucleoli. No acinar, papillary, or lepidic patterns are seen, but multiple cells have intracytoplasmic basophilic globules that suggest intracytoplasmic mucin. H, Solid adenocarcinoma with mucin. Numerous intracytoplasmic droplets of mucin are highlighted with this DPAS stain. DPAS, diastase-periodic acid Schiff.

Pathology Recommendation 4

For invasive adenocarcinomas, we suggest comprehensive histologic subtyping be used to assess histologic patterns semiquantitatively in 5% increments, choosing a single predominant pattern. Individual tumors are then classified according to the predominant pattern and the percentages of the subtypes are also reported (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Histologic Comparison of Multiple Adenocarcinomas and Impact on Staging

Comprehensive histologic subtyping can be useful in comparing multiple lung adenocarcinomas to distinguish multiple primary tumors from intrapulmonary metastases. This has a great impact on staging for patients with multiple lung adenocarcinomas. Recording the percentages of the various histologic types in 5% increments, not just the most predominant type, allows these data to be used to compare multiple adenocarcinomas, particularly if the slides of a previous tumor are not available at the time of review of the additional lung tumors.102 In addition to comprehensive histologic subtyping, other histologic features of the tumors such as cytologic (clear cell or signet ring features) or stromal (desmoplasia or inflammation) characteristics may be helpful to compare multiple tumors.102

Pathology Recommendation 5

In patients with multiple lung adenocarcinomas, we suggest comprehensive histologic subtyping may facilitate in the comparison of the complex, heterogeneous mixtures of histologic patterns to determine whether the tumors are metastases or separate synchronous or metachronous primaries (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).

LPA typically consists of bland pneumocytic cells (type II pneumocytes or Clara cells) growing along the surface of alveolar walls similar to the morphology defined in the above section on AIS and MIA (Figures 6A, B). Invasive adenocarcinoma is present in at least one focus measuring more than 5 mm in greatest dimension. Invasion is defined as (1) histological subtypes other than a lepidic pattern (i.e., acinar, papillary, micropapillary, and/or solid) or (2) myofibroblastic stroma associated with invasive tumor cells (Figure 6C). The diagnosis of LPA rather than MIA is made if the tumor (1) invades lymphatics, blood vessels, or pleura or (2) contains tumor necrosis. It is understood that lepidic growth can occur in metastatic tumors and invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas. Nevertheless, the specific term “Lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma (LPA)” in this classification defines a nonmucinous adenocarcinoma that has lepidic growth as its predominant component, and these tumors are now separated from invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. The term LPA should not be used in the context of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma with predominant lepidic growth.

In the categories of mixed subtype in the 1999/2004 WHO classifications and type C in the Noguchi classification,4,46 there was no assessment of the percentage of lepidic growth (former BAC pattern), so in series diagnosed according to these classification systems, most of the LPAs are buried among a heterogeneous group of tumors that include predominantly invasive adenocarcinomas. Nevertheless, several studies have shown lepidic growth to be associated with more favorable survival in small solitary resected lung adenocarcinomas with an invasive component.47,64,103–105 One recent study of stage I adenocarcinomas using this approach demonstrated 90% 5-year recurrence free survival.44

Pathology Recommendation 6

For nonmucinous adenocarcinomas previously classified as mixed subtype where the predominant subtype consists of the former nonmucinous BAC, we recommend use of the term LPA and discontinuing the term “mixed subtype” (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Acinar predominant adenocarcinoma shows a majority component of glands, which are round to oval shaped with a central luminal space surrounded by tumor cells (Figure 6D).4 The neoplastic cells and glandular spaces may contain mucin. Acinar structures also may consist of rounded aggregates of tumor cells with peripheral nuclear polarization with central cytoplasm without a clear lumen. AIS with collapse may be difficult to distinguish from the acinar pattern. Nevertheless, when the alveolar architecture is lost and/or myofibroblastic stroma is present, invasive acinar adenocarcinoma is considered present. Cribriform arrangements are regarded as a pattern of acinar adenocarcinoma.106

Papillary predominant adenocarcinoma shows a major component of a growth of glandular cells along central fibrovascular cores (Figure 6E).4 This should be distinguished from tangential sectioning of alveolar walls in AIS. If a tumor has lepidic growth, but the alveolar spaces are filled with papillary structures, the tumor is classified as papillary adenocarcinoma. Myofibroblastic stroma is not needed to diagnose this pattern.

Micropapillary predominant adenocarcinoma has tumor cells growing in papillary tufts, which lack fibrovascular cores (Figure 6F).4 These may appear detached and/or connected to alveolar walls. The tumor cells are usually small and cuboidal with minimal nuclear atypia. Ring-like glandular structures may “float” within alveolar spaces. Vascular invasion and stromal invasion are frequent. Psammoma bodies may be seen.

The micropapillary pattern of lung adenocarcinoma was cited in the 2004 WHO classification in the discussion,4 but there were too few publications on this topic to introduce it as a formal histologic subtype.107–109 Although most of the studies have used a very low threshold for classification of adenocarcinomas as micropapillary, including as low as 1 to 5%,108,109 it has recently been demonstrated that tumors classified as micropapillary according to the predominant subtype also have a poor prognosis similar to adenocarcinomas with a predominant solid subtype.44 All articles on the topic of micropapillary lung adenocarcinoma in early-stage patients have reported data indicating that this is a poor prognostic subtype.95,108–119 Additional evidence for the aggressive behavior of this histologic pattern is the overrepresentation of the micropapillary pattern in metastases compared with the primary tumors, where it sometimes comprises only a small percentage of the overall tumor.43

Pathology Recommendation 7

In patients with early-stage adenocarcinoma, we recommend the addition of “micropapillary predominant adenocarcinoma,” when applicable, as a major histologic subtype due to its association with poor prognosis (strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).

Solid predominant adenocarcinoma with mucin production shows a major component of polygonal tumor cells forming sheets, which lack recognizable patterns of adenocarcinoma, i.e., acinar, papillary, micropapillary, or lepidic growth (Figure 6G).4 If the tumor is 100% solid, intracellular mucin should be present in at least five tumor cells in each of two high-power fields, confirmed with histochemical stains for mucin (Figure 6H).4 Solid adenocarcinoma must be distinguished from squamous cell carcinomas and large cell carcinomas both of which may show rare cells with intracellular mucin.

Variants

Rationale for Changes in Adenocarcinoma Histologic Variants

Rationale for separation of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (formerly mucinous BAC) from nonmucinous adenocarcinomas

Multiple studies indicate that tumors formerly classified as mucinous BAC have major clinical, radiologic, pathologic, and genetic differences from the tumors formerly classified as nonmucinous BAC (Table 4).55,77,120,121,125–127,136,145–148 In particular, these tumors show a very strong correlation with KRAS mutation, whereas nonmucinous adenocarcinomas are more likely to show EGFR mutation and only occasionally KRAS mutation (Table 4). Therefore, in the new classification, these tumors are now separated into different categories (Table 1). The neoplasms formerly termed mucinous BAC, now recognized to have invasive components in the majority of cases, are classified as invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (formerly mucinous BAC).149

TABLE 4.

Difference between Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma and Nonmucinous Adenocarcinoma In Situ/Minimally Invasive Adenocarcinoma/Lepidic Predominant Adenocarcinoma

| Invasive Mucinous Adenocarcinoma (Formerly Mucinous BAC) |

Nonmucinous AIS/MIA/LPA (Formerly Nonmucinous BAC) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Female | 49/84 (58%)52,120–123 | 101/140 (72%)52,120–123 |

| Smoker | 39/87 (45%)52,120–122,124 | 75/164 (46%)52,120–122,124 |

| Radiographic appearance | Majority consolidation; air bronchogram125 | Majority ground-glass attenuation23,56,58,103,129–134 |

| Frequent multifocal and multilobar presentation56,125–128 | ||

| Cell type | Mucin-filled, columnar, and/or goblet50–52,125,135 | Type II pneumocyte and/or Clara cell50–52,125,135 |

| Phenotype | ||

| CK7 | Mostly positive (~88%)a54,55,136–139 | Positive (~98%)a54,55,136–139 |

| CK20 | Positive (~54%)a54,55,136–139 | Negative (~5%)a54,55,136–139 |

| TTF-1 | Mostly negative (~17%)1a54,55,120,137–139 | Positive (~67%)a54,55,120,137–139 |

| Genotype | ||

| KRAS mutation | Frequent (~76%)a55,94,121,127,140–144 | Some (~13%)a55,121,127,140–144 |

| EGFR mutation | Almost none (~3)a55,121,127,140–142 | Frequent (~45%)a55,121,127,140–142 |

Numbers represent the percentage of cases that are reported to be positive.

BAC, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma; AIS, adenocarcinoma in situ; MIA, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma; LPA, lepidic predominant adenocarcinoma; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; TTF, thyroid transcription factor.

Rationale for including mucinous cystadenocarcinoma in colloid adenocarcinoma

Tumors formerly classified as “Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma” are very rare, and they probably represent a spectrum of colloid adenocarcinoma. Therefore, we suggest that these adenocarcinomas that consist of uni- or oligolocular cystic structures by imaging and/or gross examination be included in the category of colloid adenocarcinoma.150 For such tumors, a comment could be made that the tumor resembles that formerly classified as mucinous cystadenocarcinoma.

Rationale for removing clear cell and signet ring carcinoma as adenocarcinoma subtypes

Clear cell and signet ring cell features are now regarded as cytologic changes that may occur in association with multiple histologic patterns.151,152 Thus, their presence and extent should be recorded, but data are not available that show a clinical significance beyond a strong association with the solid subtype. They are not considered to be specific histologic subtypes, although associations with molecular features are possible such as the recent observation of a solid pattern with more than 10% signet ring cell features in up to 56% of tumors from patients with echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene fusions (EML4-ALK).153

Rationale for adding enteric adenocarcinoma

Enteric adenocarcinoma is added to the classification to draw attention to this rare histologic type of primary lung adenocarcinoma that can share some morphologic and immunohistochemical features with colorectal adenocarcinoma.154 Because of these similarities, clinical evaluation is needed to exclude a gastrointestinal primary. It is not known whether there are any distinctive clinical or molecular features.

Histologic Features

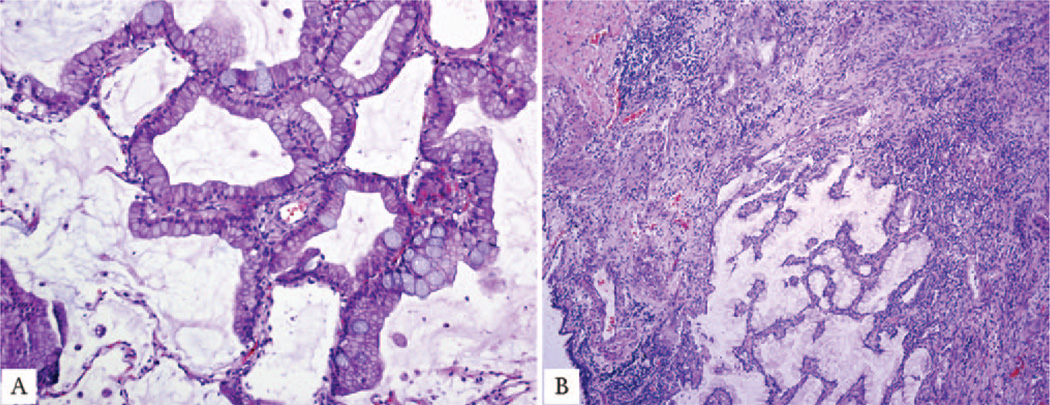

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (formerly mucinous BAC) has a distinctive histologic appearance with tumor cells having a goblet or columnar cell morphology with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin (Figures 7A, B). Cytologic atypia is usually inconspicuous or absent. Alveolar spaces often contain mucin. These tumors may show the same heterogeneous mixture of lepidic, acinar, papillary, micropapillary, and solid growth as in nonmucinous tumors. The clinical significance of reporting semiquantitative estimates of subtype percentages and the predominant histologic subtype similar to nonmucinous adenocarcinomas is not certain. When stromal invasion is seen, the malignant cells may show less cytoplasmic mucin and more atypia. These tumors differ from mucinous AIS and MIA by one or more of the following criteria: size (>3 cm), amount of invasion (>0.5 cm), multiple nodules, or lack of a circumscribed border with miliary spread into adjacent lung parenchyma.

Figure 7.

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. A, This area of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma demonstrates a pure lepidic growth. The tumor consists of columnar cells filled with abundant mucin in the apical cytoplasm and shows small basal oriented nuclei. B, Nevertheless, elsewhere this tumor demonstrated invasion associated with desmoplastic stroma and an acinar pattern.

There is a strong tendency for multicentric, multilobar, and bilateral lung involvement, which may reflect aerogenous spread. Mixtures of mucinous and nonmucinous tumors may rarely occur; then the percentage of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma should be recorded in a comment. If there is at least 10% of each component, it should be classified as “Mixed mucinous and nonmucinous adenocarcinoma.” Invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas (formerly mucinous BAC) need to be distinguished from adenocarcinomas that produce mucin but lack the characteristic goblet cell or columnar cell morphology of the tumors that have historically been classified as mucinous BAC. When mucin is identified by light microscopy or mucin stains in adenocarcinomas that do not meet the above criteria, this feature should be reported in a comment after classifying the tumor according to the appropriate terminology and criteria proposed in this classification. This can be done by adding a descriptive phrase such as “with mucin production” or “with mucinous features” rather than the term “invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma.”

Pathology Recommendation 8

For adenocarcinomas formerly classified as mucinous BAC, we recommend they be separated from the adenocarcinomas formerly classified as nonmucinous BAC and depending on the extent of lepidic versus invasive growth that they be classified as mucinous AIS, mucinous MIA, or for overtly invasive tumors “invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma” (weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).

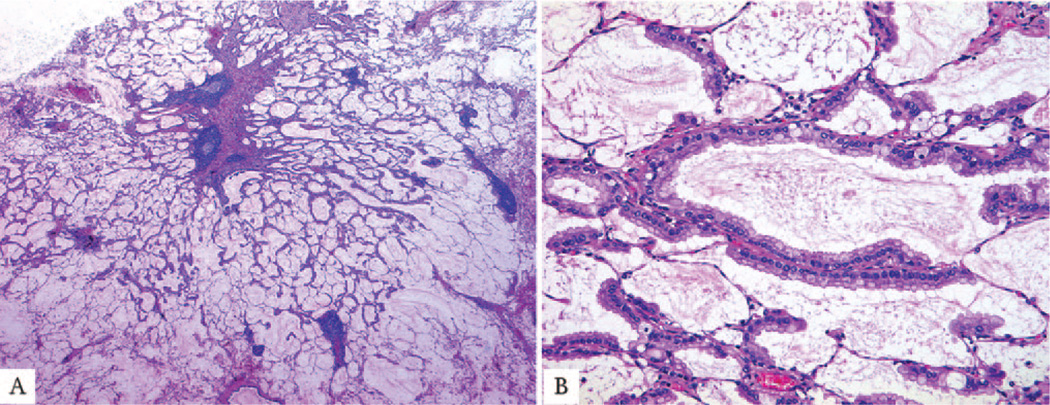

Colloid adenocarcinoma shows extracellular mucin in abundant pools, which distend alveolar spaces with destruction of their walls (Figure 8A). The mucin pools contain clusters of mucin-secreting tumor cells, which may comprise only a small percentage of the total tumor and, thus, be inconspicuous (Figure 8A).155,156 The tumor cells may consist of goblet cells or other mucin secreting cells. Colloid adenocarcinoma is found more often as a mixture with other adenocarcinoma histologic subtypes rather than as a pure pattern. A tumor is classified as a colloid adenocarcinoma when it is the predominant component; the percentages of other components should be recorded.150 Cystic gross and histologic features are included in the spectrum of colloid adenocarcinoma, but in most cases, this is a focal feature. Cases previously reported as mucinous cystadenocarcinoma are extremely rare, and now these should be classified as colloid adenocarcinoma with cystic changes. The cysts are filled with mucin and lined by goblet or other mucin secreting cells (Figure 8B). The lining epithelium may be discontinuous and replaced with inflammation including a granulomatous reaction or granulation tissue. Cytologic atypia of the neoplastic epithelium is usually minimal.157

Figure 8.

Adenocarcinoma, variants. A, Colloid adenocarcinoma consists of abundant pools of mucin growing within and distending airspaces. Focally well-differentiated mucinous glandular epithelium grows along the surface of fibrous septa and within the pools of mucin. Tumor cells may be very inconspicuous. B, This colloid adenocarcinoma contains a cystic component surrounded by a fibrous wall that is filled with pools of mucin; such a pattern was previously called mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. The surface of the fibrous wall is lined by well-differentiated cuboidal or columnar mucinous epithelium. C, Fetal adenocarcinoma consists of malignant glandular cells growing in tubules and papillary structures. These tumor cells have prominent clear cytoplasm, and squamoid morules are present. D, Enteric adenocarcinoma consists of an adenocarcinoma that morphologically resembles colonic adenocarcinoma with back-to-back angulated acinar structures. The tumor cells are cuboidal to columnar with nuclear pseudostratification.

Fetal adenocarcinoma consists of glandular elements with tubules composed of glycogen-rich, nonciliated cells that resemble fetal lung tubules (Figure 8C).4 Subnuclear vacuoles are common and characteristic. Squamoid morules may be seen within lumens. Most are low grade with a favorable outcome. High-grade tumors occur. When mixtures occur with other histologic subtypes, the tumor should be classified according to the predominant component.158 This tumor typically occurs in younger patients than other adenocarcinomas. Uniquely, these tumors appear driven by mutations in the beta-catenin gene, and the epithelial cells express aberrant nuclear and cytoplasmic staining with this antibody by immunohistochemistry.159,160 Nakatani et al. and Sekine et al.159,160 have suggested that up-regulation of components in the Wnt signaling pathway such as β-catenin is important in low-grade fetal adenocarcinomas and in biphasic pulmonary blastomas in contrast to high-grade fetal adenocarcinomas.

Enteric differentiation can occur in lung adenocarcinoma, and when this component exceeds 50%, the tumor is classified as pulmonary adenocarcinoma with enteric differentiation. The enteric pattern shares morphologic and immunohistochemical features with colorectal adenocarcinoma.154 In contrast to metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma, these tumors are histologically heterogeneous with some component that resembles primary lung adenocarcinoma such as lepidic growth. Recording of the percentages of these other components may be useful. The enteric pattern consists of glandular and/or papillary structures sometimes with a cribriform pattern, lined by tumor cells that are mostly tall-columnar with nuclear pseudostratification, luminal necrosis, and prominent nuclear debris (Figure 8D).154 Poorly differentiated tumors may have a more solid pattern. These tumors show at least one immunohistologic marker of enteric differentiation (CDX-2, CK20, or MUC2). Consistent positivity for CK7 and expression of TTF-1 in approximately half the cases helps in the distinction from metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma.154,161 CK7-negative cases may occur.162 Primary lung adenocarcinomas that histologically resemble colorectal adenocarcinoma but lack immunohistochemical markers of enteric differentiation are probably better regarded as lung adenocarcinomas with enteric morphology rather than pulmonary adenocarcinoma with enteric differentiation.163

CLASSIFICATION FOR SMALL BIOPSIES AND CYTOLOGY

Clinical Relevance of Histologic Diagnosis Drives Need to Classify NSCLC Further

This section applies to pathologic diagnosis of the majority of patients with lung cancer due to presentation with locally advanced or metastatic disease. Because of the need for improved separation of squamous cell carcinoma from adenocarcinoma, as it determines eligibility for molecular testing and impacts on specific therapies, there is now greater clinical interest in application of additional pathology tools to refine further the diagnosis in small biopsies (bronchoscopic, needle, or core biopsies) and cytology specimens from patients with advanced lung cancer, when morphologic features are not clear.30,39,40,164,165 Patients with adenocarcinoma should be tested for EGFR mutations (see evidence in Clinical Recommendation section) because patients with EGFR mutation-positive tumors may be eligible for first-line TKI therapy.8–11 Adenocarcinoma patients are also eligible for pemetrexed12–15 or bevacizumab-based chemotherapy regimens (see Clinical Recommendation section).16,17

Pathology Recommendation 9

For small biopsies and cytology, we recommend that NSCLC be further classified into a more specific histologic type, such as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, whenever possible (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence).

Data Driving Need to Classify NSCLC Further are Based Only on Light Microscopy

All current data that justify the importance of the distinction between histologic types of NSCLC in patients with advanced lung cancer are based on light microscopy alone.8–16 Thus, the diagnosis for clinical work, research studies, and clinical trials should be recorded in a manner, so it is clear how the pathologist made their determination: based on light microscopy alone or light microscopy plus special studies.

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

When a diagnosis is made in a small biopsy or cytology specimen in conjunction with special studies, it should be clarified whether the diagnosis was established based on light microscopy alone or whether special stains were required.

Management of Tissue for Molecular Studies is Critical

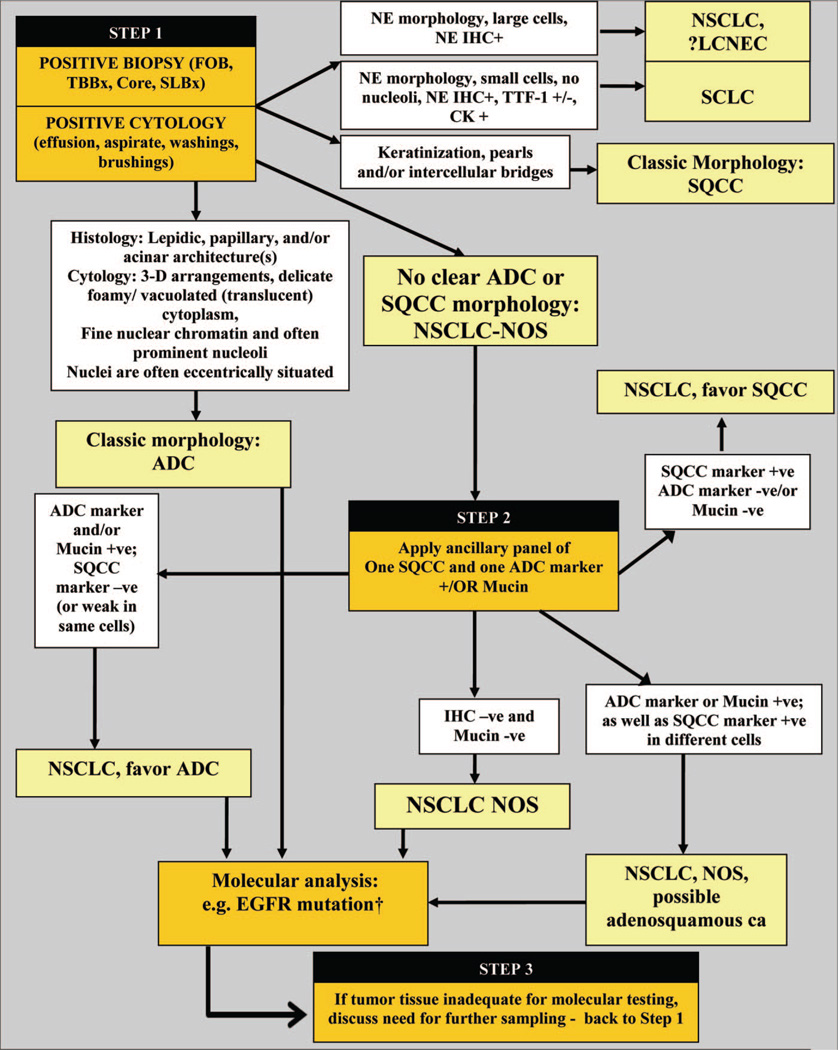

Strategic use of small biopsy and cytology samples is important, i.e., use the minimum specimen necessary for an accurate diagnosis, to preserve as much tissue as possible for potential molecular studies (Figure 9).166 Methods that use substantial amounts of tissue to make a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma, such as large panels of immunohistochemical stains or molecular studies, may not provide an advantage over routine light microscopy with a limited immunohistochemical workup.165

Figure 9.

Algorithm for adenocarcinoma diagnosis in small biopsies and/or cytology. Step 1: When positive biopsies (fiberoptic bronchoscopy [FOB], transbronchial [TBBx], core, or surgical lung biopsy [SLBx]) or cytology (effusion, aspirate, washings, and brushings) show clear adenocarcinoma (ADC) or squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) morphology, the diagnosis can be firmly established. If there is neuroendocrine morphology, the tumor may be classified as small cell carcinoma (SCLC) or non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), probably large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) according to standard criteria (+ = positive, − = negative, and ± = positive or negative). If there is no clear ADC or SQCC morphology, the tumor is regarded as NSCLC-not otherwise specified (NOS). Step 2: NSCLC-NOS can be further classified based on (a) immunohistochemical stains (b) mucin (DPAS or mucicarmine) stains, or (c) molecular data. If the stains all favor ADC: positive ADC marker(s) (i.e., TTF-1 and/or mucin positive) with negative SQCC markers, then the tumor is classified as NSCLC, favor ADC. If SQCC markers (i.e., p63 and/or CK5/6) are positive with negative ADC markers, the tumor is classified as NSCLC, favor SQCC. If the ADC and SQCC markers are both strongly positive in different populations of tumor cells, the tumor is classified as NSCLC-NOS, with a comment it may represent adenosquamous carcinoma. If all markers are negative, the tumor is classified as NSCLC-NOS. See text for recommendations on NSCLCs with marked pleomorphic and overlapping ADC/SQCC morphology. †EGFR mutation testing should be performed in (1) classic ADC, (2) NSCLC, favor ADC, (3) NSCLC-NOS, and (4) NSCLC-NOS, possible adenosquamous carcinoma. In a NSCLC-NOS, if EGFR mutation is positive, the tumor is more likely to be ADC than SQCC. Step 3: If clinical management requires a more specific diagnosis than NSCLC-NOS, additional biopsies may be indicated (−ve = negative; +ive = positive; TTF-1: thyroid transcription factor-1; DPAS +ve: periodic-acid-Schiff with diastase; +ve: positive; e.g., IHC, immunohistochemistry; NE, neuroendocrine; CD, cluster designation; CK, cytokeratin; NB, of note). EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; DPAS, diastase-periodic acid Schiff.

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

Tissue specimens should be managed not only for diagnosis but also to maximize the amount of tissue available for molecular studies.

To guide therapy for patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma, each institution should develop a multidisciplinary team that coordinates the optimal approach to obtaining and processing biopsy/cytology specimens to provide expeditious diagnostic and molecular results.

If Light Microscopic Diagnosis is Clearly Adenocarcinoma or Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Use These WHO Diagnostic Terms

Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma should be diagnosed on biopsy and cytological materials when the criteria for specific diagnosis of these tumor types in the 2004 WHO classification are met. Nevertheless, for tumors that do not meet these criteria, newly proposed terminology and criteria are outlined in Table 2 and Figure 9.4

Histologic Heterogeneity of Lung Cancer is an Underlying Complexity

Because of histologic heterogeneity, small biopsy and/or cytology samples may not be representative of the total tumor, and there may be a discrepancy with the final histologic diagnosis in a resection specimen. Still, combined histologic types that meet criteria for adenosquamous carcinoma comprise less than 5% of all resected NSCLCs.4 A much more common difficulty in small biopsies or cytologies is classifying poorly differentiated tumors where clear differentiation is difficult or impossible to appreciate on light microscopy. The heterogeneity issue also makes it impossible to make the diagnosis of AIS, MIA, large cell carcinoma, or pleomorphic carcinoma in a small biopsy or cytology, because resection specimens are needed to make these interpretations. The term “large cell carcinoma” has been used in some clinical trials, but the pathologic criteria for that diagnosis are not defined, and it is not clear how these tumors were distinguished from NSCLC-NOS, as this diagnosis specimens used to diagnose the patients with advanced-stage lung cancer studied in these trials.13,15,167

Pathology Considerations for Good Practice

The terms AIS or MIA should not be diagnosed in small biopsies or cytology specimens. If a noninvasive pattern is present in a small biopsy, it should be referred to as a lepidic growth pattern.

The term large cell carcinoma should not be used for diagnosis in small biopsy or cytology specimens and should be restricted to resection specimens where the tumor is thoroughly sampled to exclude a differentiated component.

Use Minimal Stains to Diagnose NSCLC, Favor Adenocarcinoma, or Favor Squamous Cell Carcinoma

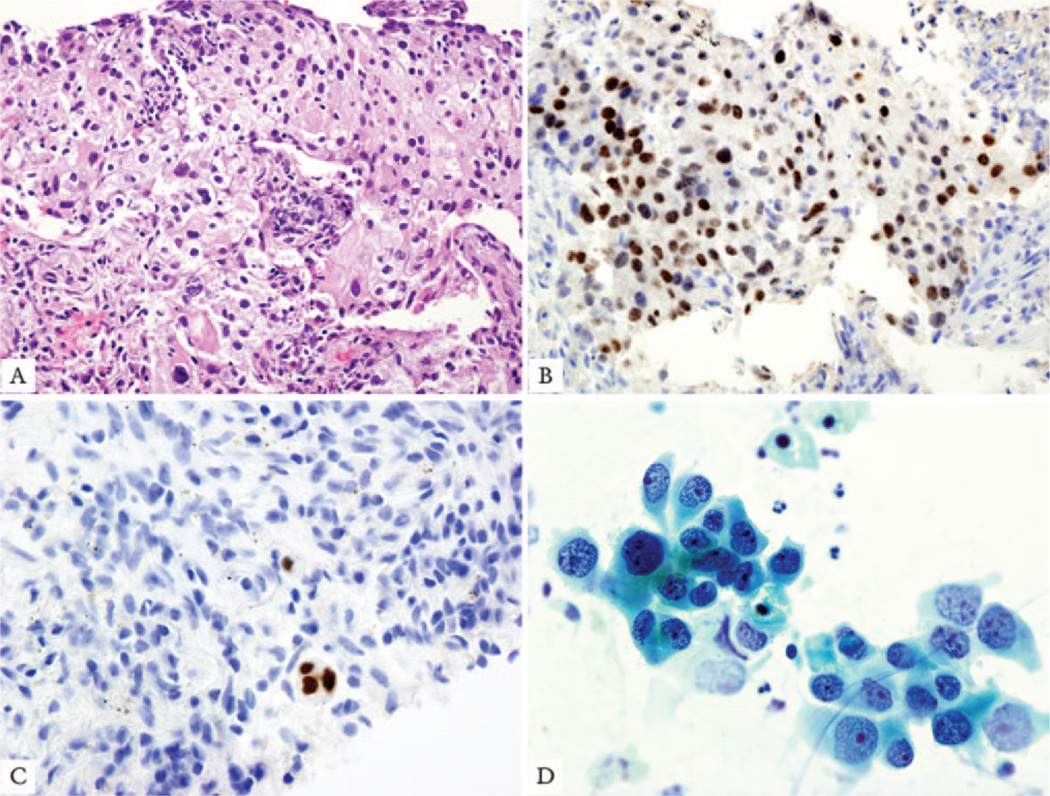

In those cases where a specimen shows NSCLC lacking either definite squamous or adenocarcinoma morphology, immunohistochemistry may refine diagnosis (Figure 9, step 2). To preserve as much tissue as possible for molecular testing in small biopsies, the workup should be minimal.165 Realizing that new markers are likely to be developed, we suggest the initial evaluation use as only one adenocarcinoma marker and one squamous marker. At the present time, TTF-1 seems to be the single best marker for adenocarcinoma. TTF-1 provides the added value of serving as a pneumocyte marker that can help confirm a primary lung origin in 75 to 85% of lung adenocarcinomas.69,168,169 This can be very helpful in addressing the question of metastatic adenocarcinoma from other sites such as the colon or breast. Diastase-periodic acid Schiff or mucicarmine mucin stains may also be of value. p63 is consistently reported as a reliable marker for squamous histology and CK5/6 also can be useful.39,40,170–176 Cytokeratin 7 also tends to stain adenocarcinoma more often than squamous cell carcinoma.177 Other antibodies (34βE12 and S100A7) are less specific and sensitive for squamous differentiation. These data have been confirmed using resections where biopsies were interpreted as NSCLC39 and also work on most needle aspirate specimens.40 It is possible that cocktails of nuclear and cytoplasmic markers (TTF-1/CK5/6 or p63/napsin-A) may allow for use of fewer immunohistochemical studies of multiple antibodies.164 Cases positive for an adenocarcinoma marker (i.e.,TTF-1) and/or mucin with a negative squamous marker (i.e., p63) should be classified as “NSCLC favor adenocarcinoma” (Figures 10A–C) and those that are positive for a squamous marker, with at least moderate, diffuse staining, and a negative adenocarcinoma marker and/or mucin stains, should be classified as “NSCLC favor squamous cell carcinoma,” with a comment specifying whether the differentiation was detected by light microscopy and/or by special stains. These two small staining panels are generally mutually exclusive. If an adenocarcinoma marker such as TTF-1 is positive, the tumor should be classified as NSCLC, favor adenocarcinoma despite any expression of squamous markers.164,165 If the reactivity for adenocarcinoma versus squamous markers is positive in a different population of tumor cells, this may suggest adenosquamous carcinoma. If tumor tissue is inadequate for molecular testing, there may be a need to rebiopsy the patient to perform testing that will guide therapy (step 3, Figure 9).

Figure 10.

Adenocarcinoma in small biopsy and cytology. Poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma, favor adenocarcinoma. A, This core biopsy shows a solid pattern of growth, and morphologically, it lacks any acinar, papillary, or lepidic patterns. The mucin stain was also negative. B, The TTF-1 stain is strongly positive. C, The p63 stain is very focally positive. The strongly and diffusely positive TTF-1 and only focal p63 staining favor adenocarcinoma. In this case, EGFR mutation was positive. D, Cytology from different adenocarcinoma shows large malignant cells with abundant cytoplasm and prominent nuclei growing in an acinar structure. EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; TTF, thyroid transcription factor.

There may be cases where multidisciplinary correlation can help guide a pathologist in their evaluation of small biopsies and/or cytology specimens from lung adenocarcinomas. For example, if a biopsy showing NSCLC-NOS is obtained from an Asian, female, never smoker with ground-glass nodules (GGNs) on CT, the pathologist should know this information as the tumor is more likely to be adenocarcinoma and have an EGFR mutation.

Cytology is a Useful Diagnostic Method, Especially When Correlated with Histology

Cytology is a powerful tool in the diagnosis of lung cancer, in particular in the distinction of adenocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma.178 In a recent study, of 192 preoperative cytology diagnoses, definitive versus favored versus unclassified diagnoses were observed in 88% versus 8% versus 4% of cases, respectively.179 When compared with subsequent resection specimens, the accuracy of cytologic diagnosis was 93% and for definitive diagnoses, it was 96%. For the adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma cases, only 3% of cases were unclassified, and the overall accuracy was 96%. When immunohistochemistry was used in 9% of these cases, the accuracy was 100%.179

Whenever possible, cytology should be used in conjunction with histology in small biopsies (Figure 10D).40,180 In another study where small biopsies were evaluated in conjunction with cytology for the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma versus unclassified (NSCLC-NOS), the result for cytology was 70% versus 19% versus 11% and for biopsies, it was 72%, 22%, and 6%, respectively.180 Still when cytology was correlated with biopsy, the percentage of cases diagnosed as NSCLC-NOS was greatly reduced to only 4% of cases.180 In a small percentage of cases (<5%), cytology was more informative than histology in classifying tumors as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma.180 The factors that contributed the greatest to difficulty in a specific diagnosis in both studies were poor differentiation, low specimen cellularity, and squamous histology.179,180

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

When paired cytology and biopsy specimens exist, they should be reviewed together to achieve the most specific and nondiscordant diagnoses.

Preservation of Cell Blocks from Cytology Aspirates or Effusions for Molecular Studies

The volume of tumor cells in biopsies may be small due to frequent prominent stromal reactions, so that there may be insufficient material for molecular analysis. Material derived from aspirates or effusions may have more tumor cells than a small biopsy obtained at the same time, so any positive cytology samples should be preserved as cell blocks, so that tumor is archived for immunohistochemical and molecular studies. Furthermore, these materials should be used judiciously in making the diagnosis to preserve as much material as possible for potential molecular studies.40,181–183 In a recent study, material from cell blocks prepared from 128 lung cancer cytology specimens was suitable for molecular analysis for EGFR and KRAS mutations in 126 (98%) of specimens.179

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

Cell blocks should be prepared from cytology samples including pleural fluids.

NSCLC-NOS: If No Clear Differentiation by Morphology or Immunohistochemistry

There will remain a minority of cases where the diagnosis remains NSCLC-NOS, as no differentiation can be established by routine morphology and/or immunohistochemistry (Figure 9, step 2). In the setting of a tumor with a negative adenocarcinoma marker (i.e., TTF-1), and only weak or focal staining for a squamous marker, it is best to classify the tumor as NSCLC-NOS rather than NSCLC, favor squamous cell carcinoma. These cases may benefit from discussion in a multidisciplinary setting (a) to determine the need for a further sample if subtyping will affect treatment; (b) whether molecular data should be sought, again if treatment will be defined by such data; (c) whether noninvasive features such as imaging characteristics (e.g., peripheral GGN supporting adenocarcinoma) favor a tumor subtype; and (d) whether clinical phenotype (e.g., female, never smoker, and Asian) may assist in determining future management (Figure 9, step 3).

Pathology Recommendation 10

We recommend that the term NSCLC-NOS be used as little as possible, and we recommend it be applied only when a more specific diagnosis is not possible by morphology and/or special stains (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence).

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

The term nonsquamous cell carcinoma should not be used by pathologists in diagnostic reports. It is a categorization used by clinicians to define groups of patients with several histologic types who can be treated in a similar manner; in small biopsies/cytology, pathologists should classify NSCLC as adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, NSCLC-NOS, or other terms outlined in Table 2 or Figure 9.

NSCLC-NOS: When Morphology and Immunohistochemistry are Conflicting

Rarely, small samples may show either morphologic features of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma with routine histology or by immunohistochemical expression of both squamous and adenocarcinoma markers; these should be termed as “NSCLC-NOS” with a comment recording the features suggesting concurrent glandular and squamous cell differentiation, specifying whether this was detected by light microscopy or immunohistochemistry. As p63 expression can occur in up to one third of adenocarcinomas,40,184,185 in a tumor that lacks squamous cell morphology, virtually all tumors that show coexpression of p63 and TTF-1 will be adenocarcinomas. It is possible that the tumor may be an adenosquamous carcinoma but that diagnosis cannot be established without a resection specimen showing at least 10% of each component. If TTF-1 and p63 positivity are seen in different populations of tumor cells, it is possible that this may be more suggestive of adenosquamous carcinoma than if these markers are coexpressed in the same tumor cells.

Interpret Morphologic and Staining Patterns to Maximize Patient Eligibility for Therapies

Presently, the recommendation for EGFR mutation testing and candidacy for pemetrexed or bevacizumab therapy is for the diagnosis of (1) adenocarcinoma, (2) NSCLCNOS, favor adenocarcinoma, or (3) NSCLC-NOS (see Clinical Recommendation section later). For this reason, in most NSCLC, the primary decision pathologists need to focus on, while interpreting small biopsies and cytology specimens, whether the tumor is a definite squamous cell carcinoma or NSCLC, favor squamous cell carcinoma versus one of the above diagnoses. Thus, when morphology or immunohistochemical findings are equivocal, pathologists need to keep in mind that a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma or NSCLC, favor squamous cell carcinoma will exclude them from histologically driven molecular testing or chemotherapy. In such a situation, it may be best to favor NSCLC-NOS, to allow the patient to be eligible for the therapeutic options mentioned earlier in the text. Hopefully, effective therapies, perhaps based on molecular targets, will become available for squamous cell carcinoma in the near future.

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

The above strategy for classification of adenocarcinoma versus other histologies and the terminology in Table 2 and Figure 9 should be used in routine diagnosis and future research and clinical trials, so that there is uniform classification of disease cohorts in relationship to tumor subtypes and data can be stratified according to diagnoses made by light microscopy alone versus diagnoses requiring special stains.

Distinction of Adenocarcinoma from Sarcomatoid Carcinomas

Cases that show sarcomatoid features such as marked nuclear pleomorphism, malignant giant cells, or spindle cell morphology should be preferentially regarded as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma if these features are clearly present, as this is apt to influence management. Nevertheless, pleomorphic carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and blastoma are very difficult to diagnose in small specimens due to the limited ability to assess for mixed histologies. Nevertheless, if a small biopsy shows what is probably an adenocarcinoma with pleomorphism, a comment should be made, e.g., “NSCLC, favor adenocarcinoma, with giant and/or spindle cell features” (depending on which feature is identified).

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

Tumors that show sarcomatoid features, such as marked nuclear pleomorphism, malignant giant cells, or spindle cell morphology, should be preferentially regarded as adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma if clear glandular or squamous features are present, as this is apt to influence management. If such features are not present, the term “poorly differentiated non-small cell carcinoma with giant and/or spindle cell features” (depending on what feature is present) should be used.

Distinction of Adenocarcinoma from Neuroendocrine Carcinomas

Some cases of NSCLC may suggest neuroendocrine (NE) morphology; these should be assessed with NE markers (CD56, chromogranin, and/or synaptophysin), so that a diagnosis of large cell NE carcinoma (LCNEC) can be suggested. The term NSCLC, possible LCNEC is usually the best term when this diagnosis is suspected as it is difficult to establish a diagnosis of LCNEC on small biopsies. In those lacking NE morphology, we recommend against using routine staining with NE markers, as immunohistochemical evidence of NE differentiation in otherwise definite adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma does not seem to affect prognosis186,187 or treatment.

Pathology Consideration for Good Practice

NE immunohistochemical markers should only be performed in cases where there is suspected NE morphology. If NE morphology is not suspected, NE markers should not be performed.

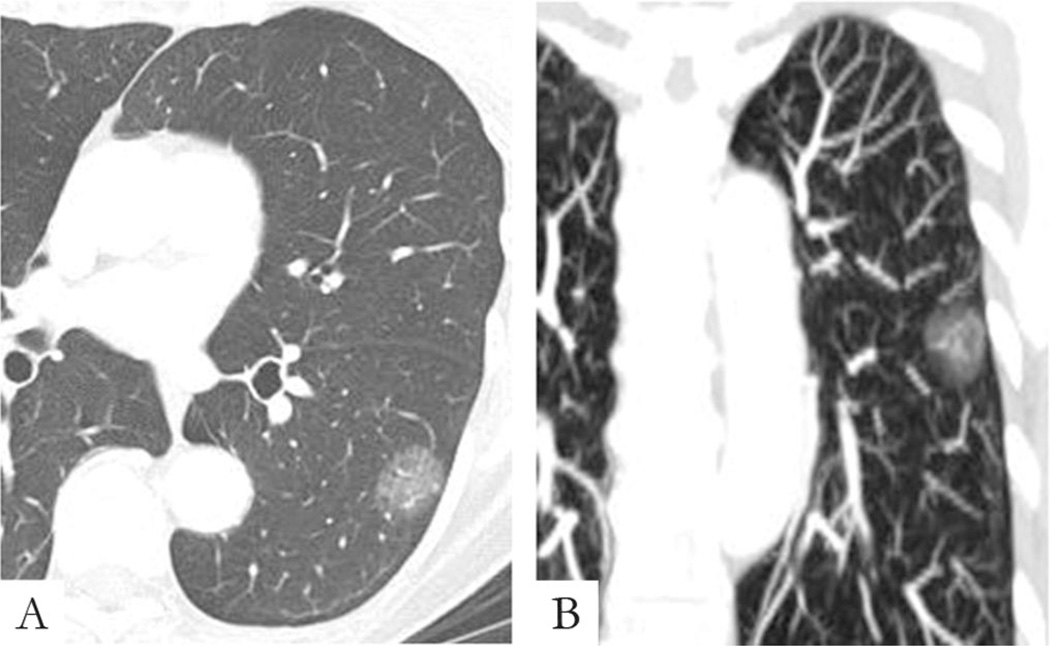

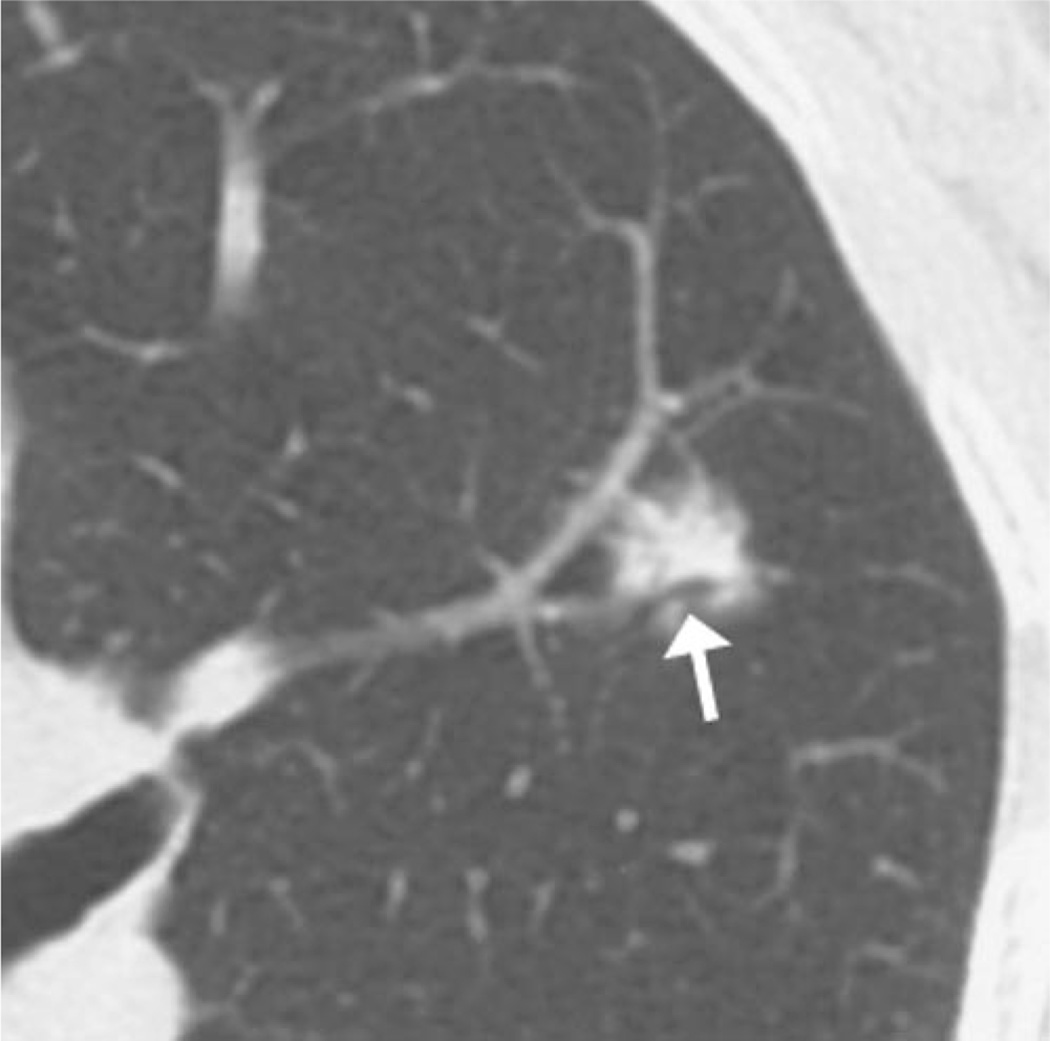

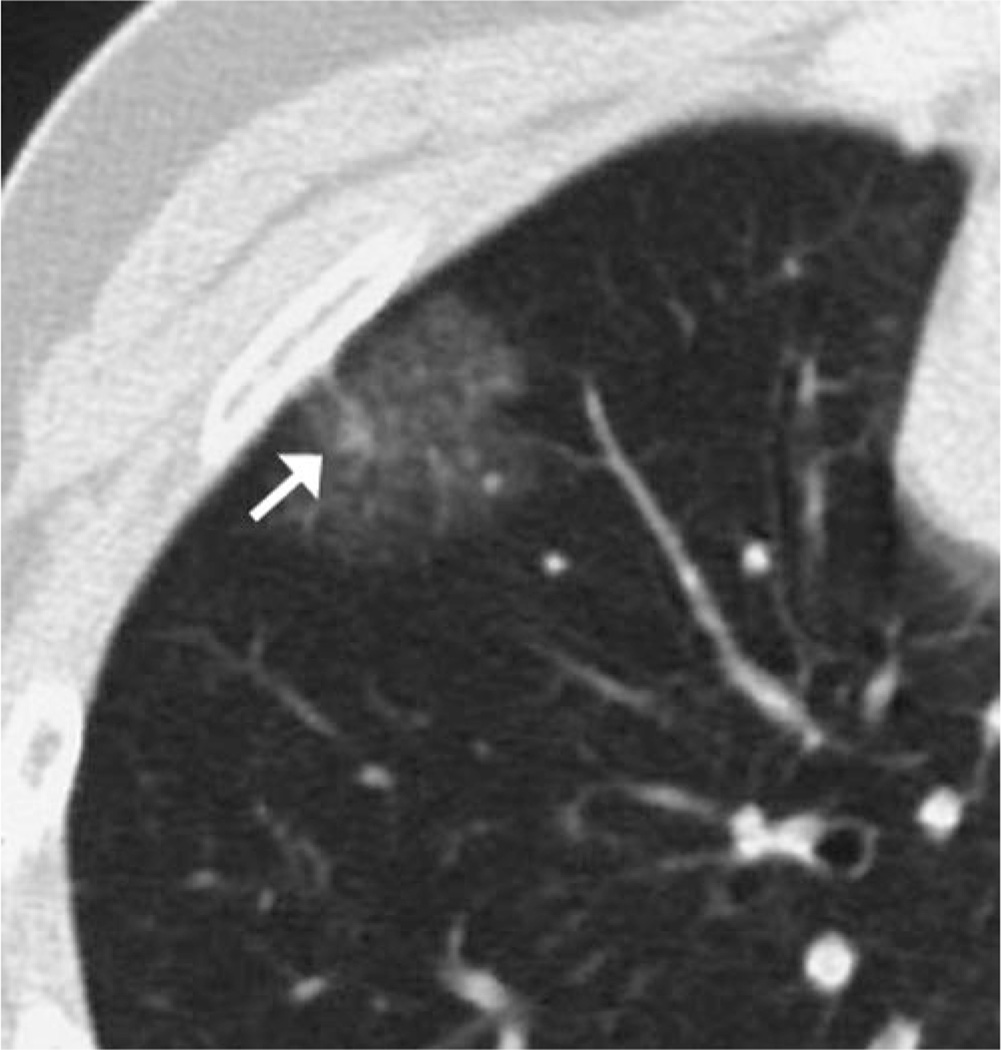

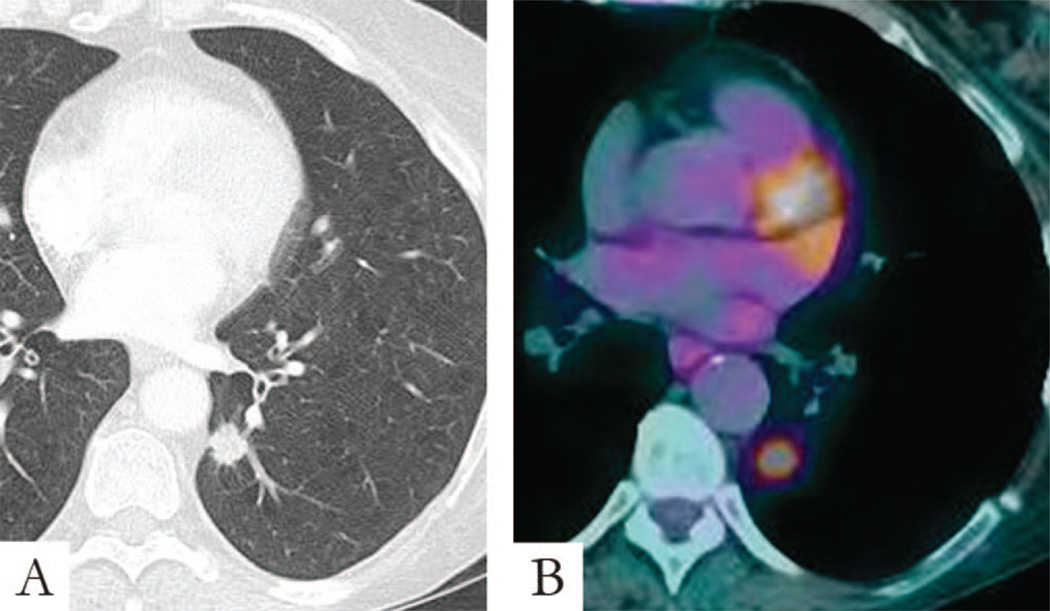

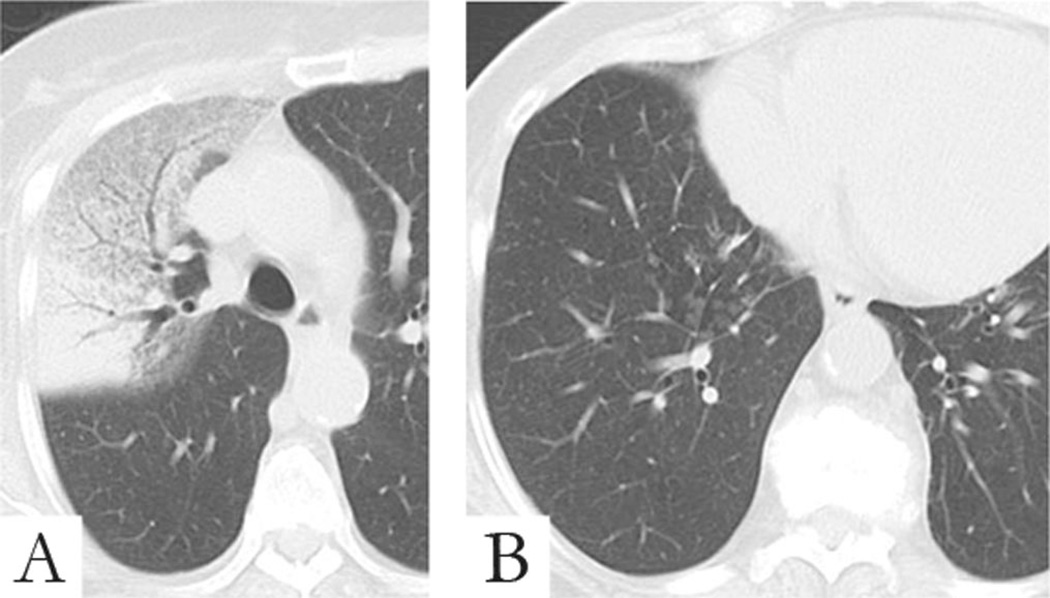

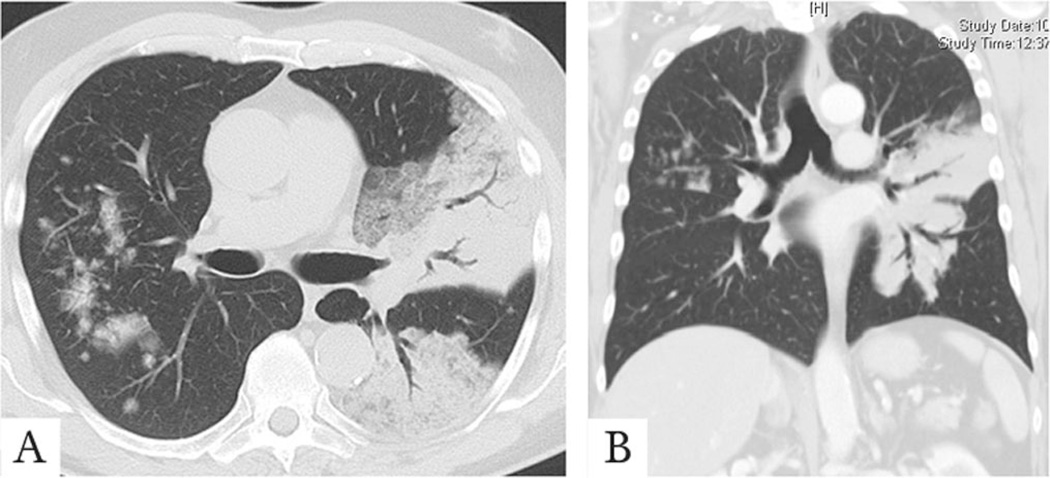

GRADING OF ADENOCARCINOMAS