Abstract

Invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD) and community acquired pneumonia (CAP) represent two of the major causes of out-patient visits, hospital admissions and deaths in the elderly. In Tuscany (Italy), in the Local Health Unit of Florence, a project aimed at implementing an active surveillance of pneumococcal diseases in the hospitalized elderly population started in 2013. The aim of this study is to show the results of the retrospective analysis (2010–2012) on hospital discharge records (HDRs) related to diseases potentially due to S. pneumoniae, using a selection of ICD9-CM codes. All ordinary hospitalizations (primary and secondary diagnoses) of the elderly population were included (11 245 HDRs). Among a population of about 200 000 inhabitants ≥65 y, the hospitalization rate (HR) increased with increasing age and was higher in males in all age groups. Almost all hospitalizations (95%) were due to CAP, only 5% were invasive diseases. Only few cases of CAP were specified as related to S. pneumoniae, the percentage was higher in case of meningitis (100%) or septicemia (22%). In-hospital deaths over the three-year period were 1703 (case fatality rate: 15%). The risk of dying, being hospitalized for a disease potentially attributable to pneumococcus (as primary diagnosis) increased significantly with age (P < 0.001), the odds ratio (OR) per increasing age year was 1.06 (95% CI 1.05–1.07) and was higher in patients with co-existing medical conditions with respect to patients without comorbidities. Currently, an active surveillance system on S. pneumoniae diseases with the inclusion of bio-molecular tests (RT-PCR), is a key step to assess the effectiveness of the PCV13 vaccine (13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine) in the elderly population after implementation of vaccination policies. The results of this study will provide the comparator baseline data for the evaluation of a possible immunization programme involving one or more cohorts of the elderly in Tuscany.

Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, hospitalizations, elderly, immunization policies, Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, Tuscany, Italy

Introduction

Community acquired pneumonia (CAP) and, to a lesser extent, invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD) represent a major cause of out-patient visits, hospital admissions and deaths in the elderly.1 The incidence of pneumococcal disease, meningitis, and CAP by age has a characteristic “U-shaped” distribution with peaks at extremes of age. There is a consistency in this pattern/figure in different geographical areas around the world.2-4

Data from the USA surveillance system confirms that age is the first risk-factor for acquiring pneumococcal diseases. In 2012, the highest incidence rates of IPD were observed in subjects over 65 y (29.6/100 000) and the mortality rates associated with IPD in the same age group was almost 4.24/100 000.5 S. pneumoniae is the most frequently isolated pathogen in CAP cases in Europe (12–68% of cases).1

The definition of CAP is: pneumonia occurring in people who have not recently been hospitalized. It is difficult to determine the disease burden of CAP in Europe, because precise data are scarce. Mortality attributable to CAP varies widely among European countries. CAP is the largest cause of death from infectious disease in adults aged >65.1,6 Pneumococcus is also an important etiologic agent of pneumonia in residents of long-term care facilities.7

Data from the CAP network in Germany (CAPNETZ) showed that Streptococcus pneumoniae was the most frequent causative agent (30% of all patients with identified pathogens). Besides, patients with pneumococcal pneumonia were more frequently admitted to hospital than others and pneumococcal pneumonia was associated with a more severe clinical course needing more medical resources as compared with non-pneumococcal pneumonia.8

In Italy incidence of CAP in the elderly (>65 y) settled to 4.8/100 000 in 1997–1999 according to Rossi et al.9 and to 3.3/100 000 in 1999–2000 according to Viegi et al.10

Since the implementation of the Italian National Plan for Vaccination 2012–2014, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is offered free of charge to all newborns with a three-dose regimen (3, 5, and 11 mo of life).11 The impact of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) immunization programme in some Italian Regions has already been demonstrated against invasive and noninvasive diseases.12,13 As far as the elderly are concerned, in USA and Europe many studies showed the positive impact of PCV vaccines in reducing the disease burden of IPD.14-19

Currently, only few Italian Regions have implemented a specific immunization programme with PCV 13 for one or more cohorts of elderly people, the majority of the Regions (including Tuscany) have adopted a risk based strategy for preventing pneumococcal diseases in adults.

Furthermore, there are few epidemiological data available in Italy for the elderly on the serotype distribution of pneumococcus, due to the scarce attitude of practitioners to investigate the etiology and also to the heterogeneity of clinical presentation of pneumococcal diseases. Moreover, pneumococcal infections in Italy are not included in the national reporting system as mandatory notifications. Thus, the need to measure the burden of disease potentially preventable by vaccination and the difficulty to find information on out-patient visits or patients cared at home prompted our research group to implement a surveillance network involving hospitals, laboratories and the university with the purpose to monitor hospitalization of the elderly population for pneumococcal diseases. Hospitalizations suggestive of disease potentially due to pneumococcus are the most reliable data source to assess the pneumococcal disease burden and to implement an active surveillance to define the epidemiology and the serotype distribution of S. pneumoniae in a given territory.

In Tuscany (Central Italy), in the Local Health Unit (LHU) of Florence, a project aimed at implementing an active surveillance of pneumococcal diseases in the hospitalized elderly population started in 2013. The Tuscany project consists of two phases: a retrospective one of 6 mo, and a prospective phase of 30 mo.

The aim of this study is to show the results of the retrospective phase of the study in order to assess the burden of disease for hospitalizations potentially caused by S. pneumoniae in the population ≥ 65 y resident in the LHU of Florence, and to define the burden of CAP and IPD in this age group, in hospital settings, between 2010 and 2012.

Results

Population aged ≥ 65 y resident in the LHU of Florence is about 200,000 inhabitants.20

In the current analysis, all ordinary hospitalizations (both primary and secondary diagnoses) potentially attributable to pneumococcus in the elderly population were included. Diseases potentially caused by S. pneumoniae in the elderly resident population of the Florentine area accounted for an overall number of 11 245 hospitalizations in the three-year period 2010–2012, with an annual mean of 3748 hospitalizations. That is, this disease burden resulted in more than 10 hospitalizations per day in Florence hospitals. In the selected period, hospitalizations occurred mainly in public hospitals (44.3%) and research hospitals (43.1%), while only 12.7% of cases were hospitalized in accredited private hospitals. (Table 1) The number of hospitalizations increased with increasing age. The highest number occurred in subjects aged 85 y and over, accounting for about 42% of hospitalizations. It is noteworthy that, in males, 34% of hospitalizations happened in this age group whereas in females this percentage reached 50%. Overall, no gender difference was found in hospitalizations over the three-year period. (Male/female ratio 1/1). However, statistical differences in gender were found concerning age of hospitalizations (P < 0.001). Indeed, among males, 41.6% of hospitalizations occurred in patients aged <80 y, whereas in females this percentage dropped to 29.0%. Mean age of hospitalization was 83.4 and 80.8 in females and in males, respectively.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 11 245 hospitalizations occurred in subjects over 64 resident in the LHU of Florence, Tuscany (Italy), in a three-year period (2010–2012).

| Covariates | Number of HDRs (%) | Covariates (continued) | Number of HDRs (%) (continued) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Admission diagnosis | ||

| 65–69 y | 798 (7.1) | Acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis | 887 (7.9) |

| 70–74 y | 1360 (12.1) | Pneumonia | 9,775 (86.9) |

| 75–79 y | 1811 (16.1) | Septicemia | 113 (1.0) |

| 80–84 y | 2562 (22.8) | Meningitis | 19 (0.2) |

| Over 85 | 4714 (41.9) | Pericarditis | 186 (1.7) |

| Sex | Pleuritis | 253 (2.3) | |

| Male | 5627 (50.0) | Myocariditis | 12 (0.1) |

| Female | 5618 (50.0) | Co-existing medical conditions | |

| Year of admission | None | 3062 (27.2) | |

| 2010 | 3452 (30.7) | Respiratory diseases | 685 (6.1) |

| 2011 | 3927 (34.9) | Diabetes | 396 (3.5) |

| 2012 | 3866 (34.4) | Cardiovascular systemdiseases | 3313 (29.5) |

| Type of hospital | Anemias | 255 (2.3) | |

| Public hospitals | 4977 (44.3) | Neoplasias | 622 (5.5) |

| Research hospital | 4845 (43.1) | Dementias | 774 (6.9) |

| Accredited private hospitals | 1423 (12.7) | Parkinson disease | 275 (2.5) |

| Number of co-existing medical conditions | Reference | Disease of kidney and urinary tract | 1262 (11.2) |

| none | 3062 (27.2) | Liver disease | 128 (1.1) |

| 1 | 4350 (38.7) | Immune deficiency/Immunosuppression conditions | 473 (4.2) |

| 2 | 2510 (22.3) | ||

| ≥ 3 | 1323 (11.8) |

Among the elderly population, annual hospitalization rates (HRs) in 2010, 2011, and 2012 were 1748, 1988, and 1957 per 100 000, respectively. In all age groups hospitalization rates were higher in males than in females. Moreover, hospitalization rates increased with age. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1. Hospitalization rate by age and gender in the LHU of Florence, Tuscany (Italy) in 2012.

Pneumonia was the most frequent cause of hospitalization (87%) followed by acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis (8%), pleuritis (2.3%), and pericarditis (1.7%). In the same period, 113 hospitalizations due to septicemia (1%) and 19 due to meningitis (0.2%) occurred, too. (Table 1)

Overall, almost all hospitalizations (around 95%) could be classified as CAP and only 5% as invasive diseases.

As far as type of diagnosis is concerned, more than a half of hospitalizations potentially attributable to pneumococcus reported the corresponding selected ICD9-CM codes in primary diagnosis (54.9%), 43.8% in secondary diagnosis and 1.3% both in primary and secondary diagnosis.

Besides, co-existing medical conditions were also investigated; the most frequent co-morbidities were cardiovascular system diseases (29.5%), disease of kidney or urinary tract (11.2%), dementias (6.9%) or respiratory disease (6.1%). In particular, the main cardiovascular diseases were: essential hypertension (prevalence 10.0%), heart failure (9.8%), chronic ischemic heart disease (5.3%), hypertensive heart disease (4.0%). As far as kidney and urinary tract diseases are concerned, chronic renal failure was the main co-existing condition observed with a prevalence of 8.3%. Furthermore, neoplasias, immunodeficiency or diabetes were reported in 5.5%, 4.2%, and 3.5% of hospitalizations, respectively. The remaining observed co-existing medical conditions were anemia, liver diseases and Parkinson disease.

Finally, 27.2% of hospitalization cases reported no co-existing medical conditions, 38.7% presented one co-existing medical conditions, 22.3% two and 11.8% three or more. (Table 1)

Overall, only 1.4% of hospitalizations were specified as pneumococcal disease (162 cases). (Table 2) This percentage was higher in case of meningitis (100%) or septicemia (22.1%) whereas it was only 1.3% in pneumonia, for which the etiologic agent is not always searched and often is not recorded in HDRs.

Table 2. Hospitalizations, in the LHU of Florence, Tuscany (Italy), in a three-year period (2010–2012), by specified pneumococcal disease.

| Disease | Specified as pneumococcal disease | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Septicemia | 27 | 122 | 22.1 |

| Meningitis | 19 | 19 | 100 |

| Pneumonia | 132 | 9784 | 1.3 |

The length of hospital stay (LOS), as showed in Figure 2, depended on admission diagnoses (primary diagnosis). Indeed, when potentially pneumococcal diseases were the main cause of hospitalization (recorded as primary diagnosis) the LOS was shorter, on average 10.3 d (95% CI 10.0–10.5), with respect to cases in which it was a co-existing medical condition (recorded only as secondary diagnosis) of patients hospitalized for different causes, on average 13.0 d (95%CI 12.7–13.3) (P < 0.001).

Figure 2. Days of hospitalizations, by type of diagnosis (primary or secondary) for the elderly in the LHU of Florence, Tuscany (Italy) in the 3-y-period 2010–2012.

Therefore, analyzing LOS, we considered only hospitalizations for diseases potentially due to S. pneumoniae as primary diagnosis. Overall, when this was the case, a total of 64 712 d of hospitalization was registered for the entire three-year period (21 471 in 2012).

In case of acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis, 90% of hospitalizations had a duration ≤ 10 d (57% ≤ 5 d), in case of pneumonia 65% had a duration ≤ 10 d (26% ≤ 5 d); on the contrary, in case of meningitis 93% had a duration of ≥ 11 d (27% ≥ 21 d). (Fig. 3)

Figure 3. Days of hospitalizations by admission diagnosis (*only hospitalizations for diseases potentially due to S. pneumoniae as primary diagnosis) for the elderly in the LHU of Florence, Tuscany (Italy) in the 3-y-period 2010–2012.

LOS also depended from the number of co-existing medical conditions associated. Indeed, LOS of patients with a disease potentially attributable to pneumococcus and no other co-existing medical conditions was 9.2 d (36.9% with LOS ≤ 5 d). LOS of patients who had three or more co-existing condition was on average 11.5 d (18.3% with LOS ≤ 5 d).

In-hospital deaths over the 3-y-period were 1703 (case fatality rate: 15%).

The risk of dying, being hospitalized for a disease potentially attributable to pneumococcus (recorded as primary diagnosis) increased significantly with age, showing a significant linear trend by age (P < 0.001), the odds ratio (OR) per increasing age year being 1.06 (95% CI 1.05–1.07). In particular, the risk of dying in subjects between 75 and 84 y was more than twice compared with the first considered age group, whereas it was almost 4-fold higher in subjects over 85 y. (Table 3)

Table 3. Case fatality, multivariable logistic regression analysis (only hospitalizations for diseases potentially due to S. pneumoniae as primary diagnosis), in the LHU of Florence (2010–2012).

| OR | 95% C.I. | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | |||

| 65–69 y | Reference | ||

| 70–74 y | 0.97 | 0.55–1.68 | 0.90 |

| 75–79 y | 2.30 | 1.42–3.71 | 0.001 |

| 80–84 y | 2.22 | 1.39–3.56 | 0.001 |

| Over 85 | 3.70 | 2.35–5.82 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.79 | 0.67–0.93 | 0.005 |

| Admission diagnosis | |||

| Acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis | Reference | ||

| Pneumonia | 6.92 | 2.83–16.89 | < 0.001 |

| Septicemia | 6.97 | 2.25–21.57 | 0.001 |

| Meningitis | 47.41 | 11.30–198.89 | < 0.001 |

| Pericarditis | 0.57 | 0.07–4.94 | 0.608 |

| Pleuritis | 1.97 | 0.52–7.51 | 0.319 |

| Type of hospital | |||

| Public hospitals | Reference | ||

| Research hospital | 1.23 | 1.01–1.51 | 0.044 |

| Accredited private hospitals | 1.35 | 1.04–1.76 | 0.024 |

| Co-existing medical conditions | |||

| None | Reference | ||

| Respiratory diseases | 0.87 | 0.60–1.25 | 0.437 |

| Diabetes | 0.62 | 0.36–1.06 | 0.082 |

| Cardiovascular system diseases | 0.68 | 0.54–0.84 | 0.001 |

| Anemias | 0.23 | 0.09–0.56 | 0.001 |

| Neoplasias | 0.66 | 0.42–104 | 0.073 |

| Dementias | 0.91 | 0.65–1.27 | 0.575 |

| Parkinson disease | 1.13 | 0.71–1.79 | 0.611 |

| Disease of kidney and urinary tract | 1.32 | 1.02–1.71 | 0.037 |

| Liver disease | 1.61 | 0.80–3.26 | 0.192 |

| Immune deficiency/immunosuppression conditions | 0.98 | 0.62–1.53 | 0.918 |

Males had a significantly higher risk of dying with respect to females (P = 0.005). As expected, the highest risk of dying was found in case of meningitis (almost 50 times higher), and it was also significantly higher in case of septicemia and pneumonia (about 7 times higher), with respect to simple acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis. (Table 3)

With regard to the type of hospital, the Research hospital showed a slightly increased case fatality when compared with public hospitals, (adjusted OR; 1.23; 95% CI 1.01–1.51). However, this result maybe explainable because of residual confounding due to a more complex case-mix (Unadjusted OR 1.4; 95% CI 1.12–1.66). Moreover, a significantly higher case fatality rate was also observed in accredited private hospitals (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.04–1.76) (P = 0.02).

Patients with a co-existing disease of kidney or urinary tract had a slight significantly higher risk of dying with respect to patients without comorbidities associated, that could be explainable due to higher risk of patients with acute renal failure (OR 5.18; 95% CI 3.57–7.52). Moreover, a significantly higher risk was found also in patients with lymphomas (OR 2.62; 95% CI 1.09–6.30).

Unexpectedly, we found a lower risk of dying among patients with anemia and cardiovascular diseases, due to the lower risk that was found only in patients with essential hypertension (OR 0.38; 95% CI 0.26–0.55) or hypertensive heart disease (OR 0.29; 95% CI 0.15–0.56).

Discussion

In the current analysis, all ordinary hospitalizations (both primary and secondary diagnoses) of the elderly (>65 y) population resident in the LHU of Florence (Italy) were included. The burden of diseases potentially caused by S. pneumoniae in the LHU of Florence is quite relevant for the population ≥65 y. About 10 cases per day were observed in this study. Hospitalization rate (HR) increases with increasing age. Age is confirmed to be one of the main risk factors for pneumococcal diseases. Male gender is more affected than female gender. Almost all hospitalizations (around 95%) were due to CAP, only 5% were invasive diseases. The picture has remained largely unchanged over the 2010–2012 period.

According to our results, men were hospitalized, for diseases potentially related to S. pneumonia at an earlier age than women. A possible reason could be found in the fact that, generally, the hospitalized men in our sample had concomitantly more associated co-morbidities than females. This is in line with other studies. CAPs have a significant impact on elderly individuals, who are affected more frequently and with more severe consequences than younger populations. As the population ages, it is expected that the medical and economic impact of this disease will increase.6

A paramount underestimation of pneumococcal diseases is showed in Italian epidemiological studies. An analysis of hospital discharge records (HDRs) restricted to ICD9-CM code 481 for pneumonia, showed that in Italy in the period 1999–2003, hospitalizations for which pneumococcal pneumonia was specifically reported were annually, on average, 2443, among them over 45% occurred in subjects over 65 y. While hospitalizations due to pneumococcal meningitis and or septicemia were annually, on average, 415 and 212, respectively and over 30% of them occurred in subjects over 65 y.21 Moreover, in the period 1985–2003, mortality due to pneumococcal pneumonia has consistently increased in Italy, especially in the last decade. In addition, the highest percentages could be observed in subjects over 65 y (ranging from 70% to 87%, depending on the year).21

As presented in the following evidences, active surveillance studies in Italy evaluating the incidence of IPD showed that there is an utmost underestimation.

In 2002, the European Commission promoted and funded a study called “Pneumococcal Disease in Europe” (PNC-EURO) identifying four European countries, including Italy. Two Italian comparable Regions (Piedmont, in the North, and Apulia, in the South, overall accounting for 14% of the Italian population) were involved and the estimated incidence for IPD in the age group ≥ 65 y in Piedmont and Apulia, was 5.7 per 100 000 and 0.2 per 100 000, respectively.22

Moreover, about 96% of isolates from IPD patients, aged 65 y and over, belonged to serogroups included in the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine, whereas about 79% of strains isolated from patients under 5 y of age were related to serotypes included in the 7-valent conjugate vaccine.22

In 2006, Merito et al. estimated an overall incidence rate for pneumonia among the elderly population of 16.3 per 100 000 persons.23

Moreover, IPD and risk of death is higher in patients with co-morbidities. Patients with certain conditions are associated with an increased risk of contracting, and dying from IPD.24-27

In our study, analysis of co-existing medical conditions was limited to analyze the selection of HDRs, thus it is likely underestimated. In order to perform a more precise estimate of patients’ comorbidities all HDRs referring to each patient in the index year and in the five years before the index date should be analyzed. Despite this limitation, analyzing co-existing conditions showed interesting results (i.e., LOS). Furthermore, adjusting for co-existing conditions was fundamental in order to estimate the risk of dying for diseases potentially attributable to S. pneumoniae by age, gender and type of hospital.

Some other limitations of the study could be traced. As a matter of fact, hospitalizations due to S. pneumoniae are nowadays confirmed by means of blood cultures, but the sensitivity of this method is not often reliable, especially in case of antimicrobial treatment. Besides, blood cultures are not always performed. Of course, this study, considering all hospitalized cases, does not take into account all those cases that are not severe enough to be admitted to hospital, so the result is an underestimation of the problem. A further distortion due to the source of data is that the case fatality rates could be higher than those really occuring, because the most serious cases of IPD or CAP are hospitalized.

In our study, only few cases of CAP were specified as related to S. pneumoniae. As a matter of fact, HDRs represent the regional reimbursement document for the hospital and they are not filled in for diagnostic purpose. This could partly explain why etiology was not specified with high frequency. The highest percentage of specified pneumococcal disease was found in HDRs due to invasive bacterial diseases, such as septicemia (22%) and meningitis (100%).

Our results confirm that the burden of pneumococcal diseases increases with aging, having a higher incidence and mortality from pneumococcal disease. IPDs have a greater case fatality in patients with chronic illnesses and other co-morbidities. A higher risk of dying in patients with acute renal failure and with lymphomas was observed in our study, confirming data from other studies.26,28

CAP will increase with an aging population and will continue to represent a significant clinical and economic burden. Available data on HDRs in Italy heavily underestimate the real burden of pneumococcal disease. An Italian study by Amodio et al. proposed a model for estimating the burden of pneumococcal pneumonia on hospitalizations. Analyzing a total of 72 372 hospitalizations occurring in Sicily from 2005 to 2012 with at least one ICD-9 CM diagnosis code suggestive of all-cause pneumonia, only 2.7% hospitalizations had specific ICD-9 CM diagnosis codes for pneumococcal pneumonia. Whereas, according to the designed model, almost 23% of pneumonia cases among all-cause pneumonia was estimated to be attributable to S. pneumoniae.29

A more sensitive surveillance system is needed nationwide. Surveillance of an infectious disease after the introduction of a new immunization programme, in order to monitor the impact of the strategy is not an optional measure. Complete epidemiological data are the cornerstone for surveillance. The hospital can play an important role in that process being the place where more severe cases are observed, and where a specific surveillance can be performed with the most updated techniques of molecular biology.

Moreover, the increasing numbers of older patients hospitalized with CAP and IPD will consume an increasing percentage of health resources in the future. Such considerable cost for treatment highlight the need to prevent CAP and IPD with an effective vaccine. PCV vaccines may prevent a considerable proportion of the overall burden of CAP.30

Conclusions

The results of our study are the first step to assess the real burden of disease through the prospective phase, and to tailor possible vaccination strategies for the elderly in Tuscany. An active surveillance system of S. pneumoniae diseases with the inclusion of bio-molecular test, as RT-PCR to be compared with results of blood cultures, is a key to assess, in the near future, the effectiveness of the PCV13 vaccine in the elderly population.31,32

Besides the evaluation of pneumococcal serotypes distribution in the elderly will help to define if serotypes in this population are the same as in the pediatric population or different and to assess whether the elderly could be indirectly protected by children PCV vaccination, implemented in Tuscany since 2008, or if they need a direct protection through a targeted vaccination programme.

Moreover, the results of this study will provide the baseline data for potential comparison, after the possible offer of PCV13 vaccine (13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine) in Tuscany to one or more cohorts of elderly, like some Italian Regions and some European countries have already implemented in their immunization programmes.

Materials and Methods

We performed a population-based retrospective study to investigate acute hospital admission rates, length of stay and case fatality for diseases potentially due to S. pneumoniae in elderly aged 65 or older resident in Florence LHU (both for all conditions combined and for specific diagnoses). Analyses were based on HDRs for potentially associated S. pneumoniae diseases, using a selection of ICD9-CM codes (Table 4).

Table 4. ICD9-CM codes selected for the analysis of hospital discharge records of elderly (aged 65 and over) resident in Florence LHU, Tuscany (Italy), in the period 2010–2012.

| Disease | ICD9-CM Code |

|---|---|

| Acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis | 466.0, 466.19 |

| Pneumonia | 480–487.0 |

| Streptococcal or pneumococcal septicemia | 038.0, 038.2 |

| Bacterial meningitis, streptococcal or pneumococcal | 320, 320.1, 320.2, 322 |

| Acute pericarditis | 420–420.99 |

| Pneumococcal peritonitis | 567.1 |

| Acute pleuritis | 511.0, 511.1 |

| Acute myocarditis | 422–422.92 |

| Streptococcal or pneumococcal infection in other conditions | 041.0, 041.2 |

| Pyogenic arthritis | 711.0 |

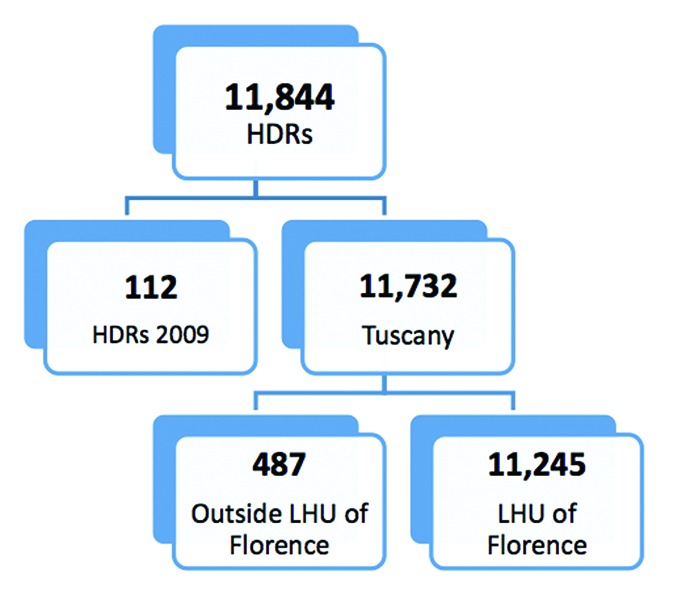

We included data for individuals aged 65 and over, whose hospital admission was between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012. Hospitalizations in ordinary admission, excluding Day Hospital, were included in the analysis. 11 844 HDRs of all subjects aged 65 or older resident in the LHU of Florence and hospitalized for potentially associated S. pneumonia diseases between 2010 and 2012 were collected. Of these, 112 HDRs were excluded because of hospital admission in 2009, and 487 HDRs because they concerned hospitals outside the LHU of Florence. The main study database therefore comprised 11 245 HDRs. (Fig. 4)

Figure 4. Selection of HDRs, included in the analysis.

The primary outcome was potentially associated S. pneumoniae hospitalization rates. Secondary outcomes included: case fatality rates, length of hospital stay, prevalence of co-existing medical conditions, and the number of hospitalization due to specified pneumococcal disease.

The covariates concerning potentially associated S. pneumoniae diseases were age, gender, diagnosis (both as specific diagnoses as well as grouped as CAP and IPD), year of hospital admission, type of hospital (public hospitals, research hospital, accredited private hospitals), co-existing medical conditions (respiratory diseases; diabetes, cardiovascular diseases; anemia; neoplasm; dementias; Parkinson diseases; kidney and urinary tract diseases; liver diseases; immune deficiency/immunosuppressions conditios). (Table 5)

Table 5. ICD9-CM codes for co-existing medical conditions considered in the analysis.

| Disease | ICD9-CM Code |

|---|---|

| Respiratory diseases | |

| Asthma | 493 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 491 |

| Emphysema | 492 |

| Other Chronic Respiratory Diseases | 494, 496 |

| Pulmonary insufficiency/Respiratory failure | 518.82 |

| Diabetes | 250 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | |

| Heart failure | 428, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.011, 404 |

| Pulmonary edema | 518.4, 514 |

| Chronic ischemic heart disease | 414.01, 429.2, 414.1, 414.8, 414.9, 412 |

| Angina pectoris | 413, 411.1 |

| Essential hypertension | 401 |

| Hypertensive heart disease | 402 |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 427.3 |

| Anemias | 280–283 |

| Neoplasms | |

| Malignant neoplasm of trachea bronchus and lung | 162 |

| Malignant neoplasm of other sites within the respiratory system and intrathoracic organs | 160–161, 163–165 |

| Malignant neoplasm of other sites | 208, 140–165, 170–176, 179–199, 210–239 |

| Dementias | |

| Alzheimer disease | 331.0 |

| Other dementias | 290.4, 294.1, 294.2, 290.0, 290.10, 290.11, 290.13, 290.21, 290.8, 290.9, 331.1, 331.2, 331.6, 331.7, 331.81, 331.82, 331.89, 331.9 |

| Parkinson disease | 332 |

| Diseases of kidney and urinary tract | |

| Acute kidney failure | 584 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 585 |

| Other diseases of kidney and urinary tract | 581, 582, 586, 590, 588, 753 |

| Liver diseases | 570–572 |

| Immune deficiency/immunosuppression conditions | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] disease | 042 |

| Organ or tissue replaced by transplant | V42 |

| Immunity Disorders | 284, 288, 289, 279 |

| Celiac disease | 579.0 |

| Lymphomas and other malignant neoplasms of lymphoid and histiocytic tissue | 200–202 |

| Multiple myeloma and immunoproliferative neoplasms | 203 |

| Leukemias | 204–208 |

Age was categorized in 5 groups: 65–69 y; 70–74 y; 75–79 y; 80–84 y; ≥ 85 y. “Length of hospital stay” (LOS) was defined as the time between admission and discharge from the hospital or in-hospital death. Hospitals were divided into 3 groups based on hospital characteristics: public hospitals (n = 5), research hospitals (n = 1), and accredited private hospitals (n = 14). Co-existing medical conditions were analyzed both as diseases’ groups and as specific diagnoses, as well as categorized according to their number (none, 1, 2, 3, or more).

Statistical analysis

Age- and sex-specific hospitalization rates were calculated referring to corresponding population aged 65 or older resident in LHU of Florence. In Table 6 the elderly population broken down by age group and gender is reported.20

Table 6. Elderly population resident in Florence LHU, by age group and gender, updated to December 31, 2010.

| Male | Female | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 65–69 y | 21 584 | 24 846 | 46 430 |

| 70–74 y | 21 963 | 26 715 | 48 678 |

| 75–79 y | 16 826 | 22 330 | 39 156 |

| 80–84 y | 12 629 | 19 611 | 32 240 |

| ≥ 85 y | 9520 | 21 491 | 31 011 |

| Total | 82 522 | 114,993 | 197 515 |

To assess the independent relation between an admission diagnosis of potentially associated S. pneumonia diseases and in-hospital death, we constructed multivariable logistic regression models.

Initially, univariate logistic regression analyses were performed, to determine potential associations between confounding variables and the above mentioned outcome. Subsequently, all significant covariates from the univariate analyses were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. Regardless of significance, we planned a priori to include patients’ age and gender.

Variables included in the final multivariable model were: age, gender, type of hospital, admission diagnosis, and co-existing medical conditions.

For both the univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses we used a level for statistical significance P< 0.05. The data were analysed using the STATA version 11.0 (Statacorp).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

SB received a partial support from Pfizer Italy for a part time researcher position, PB participated in national and international boards sponsored by Pfizer.

Acknowledgments

The work was partially supported by a research grant provided by Pfizer Inc.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- LHU

Local Health Unit

- PCV

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

- HDR

hospital discharge record

- HR

hospitalization rate

- DRG

Diagnosis Related Groups

- ICD9-CM

International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision - Clinical Modification

- LOS

Length of Hospital Stay

References

- 1.Welte T, Torres A, Nathwani D.. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia among adults in Europe. Thorax 2012; 67:71 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/thx.2009.129502; PMID: 20729232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho PL, Chiu SS, Cheung CH, Lee R, Tsai TF, Lau YL.. Invasive pneumococcal disease burden in Hong Kong children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2006; 25:454 - 5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.inf.0000215004.85582.30; PMID: 16645513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntyre P, Gilmour R, Watson M.. Differences in the epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease, metropolitan NSW, 1997-2001. N S W Public Health Bull 2003; 14:85 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1071/NB03026; PMID: 12806407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jokinen C, Heiskanen L, Juvonen H, Kallinen S, Karkola K, Korppi M, Kurki S, Rönnberg PR, Seppä A, Soimakallio S, et al.. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in the population of four municipalities in eastern Finland. Am J Epidemiol 1993; 137:977 - 88; PMID: 8317455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs): Emerging Infections Program Network, Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/surv-reports.html [Last accessed July 2014]

- 6.Stupka JE, Mortensen EM, Anzueto A, Restrepo MI.. Community-acquired pneumonia in elderly patients. Aging health 2009; 5:763 - 74; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2217/ahe.09.74; PMID: 20694055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loeb M.. Pneumonia in the elderly. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2004; 17:127 - 30; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00001432-200404000-00010; PMID: 15021052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pletz MW, von Baum H, van der Linden M, Rohde G, Schütte H, Suttorp N, Welte T.. The burden of pneumococcal pneumonia - experience of the German competence network CAPNETZ. Pneumologie 2012; 66:470 - 5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1055/s-0032-1310103; PMID: 22875730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giorgi Rossi P, Agabiti N, Faustini A, Ancona C, Tancioni V, Forastiere F, Perucci CA.. The burden of hospitalised pneumonia in Lazio, Italy, 1997-1999. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8:528 - 36; PMID: 15137527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viegi G, Pistelli R, Cazzola M, Falcone F, Cerveri I, Rossi A, Ugo Di Maria G.. Epidemiological survey on incidence and treatment of community acquired pneumonia in Italy. Respir Med 2006; 100:46 - 55; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.04.013; PMID: 16046113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.della Salute M. Piano Nazionale Prevenzione Vaccinale (PNPV) 2012-14. Gazzetta Ufficiale n. 60 del 12.03.2012 (Supplemento Ordinario n.47). Italian Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/c_17_pubblicazioni_1721_allegato.pdf

- 12.Martinelli D, Pedalino B, Cappelli MG, Caputi G, Sallustio A, Fortunato F, Tafuri S, Cozza V, Germinario C, Chironna M, et al. , Apulian Group for the surveillance of pediatric IPD.. Towards the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate universal vaccination: effectiveness in the transition era between PCV7 and PCV13 in Italy, 2010-2013. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:33 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.26650; PMID: 24096297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durando P, Faust SN, Fletcher M, Krizova P, Torres A, Welte T.. Experience with pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (conjugated to CRM197 carrier protein) in children and adults. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19:Suppl 11 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/1469-0691.12320; PMID: 24083785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilishvili T, Lexau C, Farley MM, Hadler J, Harrison LH, Bennett NM, Reingold A, Thomas A, Schaffner W, Craig AS, et al. , Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network.. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis 2010; 201:32 - 41; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/648593; PMID: 19947881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Linden M, Weiß S, Falkenhorst G, Siedler A, Imöhl M, von Kries R.. Four years of universal pneumococcal conjugate infant vaccination in Germany: impact on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease and serotype distribution in children. Vaccine 2012; 30:5880 - 5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.068; PMID: 22771186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F, Kyaw MH, Shefer A, Winston CA, Nuorti JP.. Health care utilization for pneumonia in young children after routine pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007; 161:1162 - 8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1162; PMID: 18056561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee GE, Lorch SA, Sheffler-Collins S, Kronman MP, Shah SS.. National hospitalization trends for pediatric pneumonia and associated complications. Pediatrics 2010; 126:204 - 13; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2009-3109; PMID: 20643717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koshy E, Murray J, Bottle A, Sharland M, Saxena S.. Impact of the seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination (PCV7) programme on childhood hospital admissions for bacterial pneumonia and empyema in England: national time-trends study, 1997-2008. Thorax 2010; 65:770 - 4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/thx.2010.137802; PMID: 20805169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durando P, Crovari P, Ansaldi F, Sticchi L, Sticchi C, Turello V, Marensi L, Giacchino R, Timitilli A, Carloni R, et al. , Collaborative Group for Pneumococcal Vaccination in Liguria.. Universal childhood immunisation against Streptococcus pneumoniae: the five-year experience of Liguria Region, Italy. Vaccine 2009; 27:3459 - 62; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.052; PMID: 19200823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Resident population, by LHU in Tuscany, 2010. Available from: http://web.rete.toscana.it/demografia/?MIval=pop_ricerca [last accessed April 2014].

- 21.Regional Health Agency of Tuscany. (ARS). Dossier: Introduzione universale della vaccinazione contro le patologie causate da Streptococcus pneumoniae nei bambini e negli adulti: prove di efficacia]. July 2007. Italian. Available from: http://www.epicentro.iss.it/ebp/pdf/strepto.pdf

- 22.D’Ancona F, Salmaso S, Barale A, Boccia D, Lopalco PL, Rizzo C, Monaco M, Massari M, Demicheli V, Pantosti A, Italian PNC-Euro working group.. Incidence of vaccine preventable pneumococcal invasive infections and blood culture practices in Italy. Vaccine 2005; 23:2494 - 500; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.037; PMID: 15752836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merito M, Giorgi Rossi P, Mantovani J, Curtale F, Borgia P, Guasticchi G.. Cost-effectiveness of vaccinating for invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly in the Lazio region of Italy. Vaccine 2007; 25:458 - 65; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.005; PMID: 17049685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butler JC, Schuchat A.. Epidemiology of pneumococcal infections in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1999; 15:Suppl 111 - 9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2165/00002512-199915001-00002; PMID: 10690791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization.. 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2008; 83:373 - 84; PMID: 18927997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hoek AJ, Andrews N, Waight PA, Stowe J, Gates P, George R, Miller E.. The effect of underlying clinical conditions on the risk of developing invasive pneumococcal disease in England. J Infect 2012; 65:17 - 24; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.02.017; PMID: 22394683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonnel AR, Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR.. Immune dysfunction and infections in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:727 - 38; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.02.031; PMID: 21397731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kyaw MH, Rose CE Jr., Fry AM, Singleton JA, Moore Z, Zell ER, Whitney CG, Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Program of the Emerging Infections Program Network.. The influence of chronic illnesses on the incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease in adults. J Infect Dis 2005; 192:377 - 86; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/431521; PMID: 15995950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amodio E, Costantino C, Boccalini S, Tramuto F, Maida CM, Vitale F.. Estimating the burden of hospitalization for pneumococcal pneumonia in a general population aged 50 years or older and implications for vaccination strategies. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/hv.27947; PMID: 24577505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alicino C, Barberis I, Orsi A, Durando P.. Pneumococcal vaccination strategies in adult population: perspectives with the pneumococcal 13 - valent polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. Minerva Med 2014; 105:89 - 97; PMID: 24572454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bechini A, Boccalini S, Bonanni P.. Immunization with the 7-valent conjugate pneumococcal vaccine: impact evaluation, continuing surveillance and future perspectives. Vaccine 2009; 27:3285 - 90; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.058; PMID: 19200829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasinato A, Indolfi G, Marchisio P, Valleriani C, Cortimiglia M, Spanevello V, Chiamenti G, Buzzetti R, Resti M, Azzari C, Italian Group for the Study of Bacterial Nasopharyngeal Carriage in Children.. Pneumococcal serotype distribution in 1315 nasopharyngeal swabs from a highly vaccinated cohort of Italian children as detected by RT-PCR. Vaccine 2014; 32:1375 - 81; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.023; PMID: 24486364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]