Abstract

Progressive CKD is generally detected at a late stage by a sustained decline in eGFR and/or the presence of significant albuminuria. With the aim of early and improved risk stratification of patients with CKD, we studied urinary peptides in a large cross-sectional multicenter cohort of 1990 individuals, including 522 with follow-up data, using proteome analysis. We validated that a previously established multipeptide urinary biomarker classifier performed significantly better in detecting and predicting progression of CKD than the current clinical standard, urinary albumin. The classifier was also more sensitive for identifying patients with rapidly progressing CKD. Compared with the combination of baseline eGFR and albuminuria (area under the curve [AUC]=0.758), the addition of the multipeptide biomarker classifier significantly improved CKD risk prediction (AUC=0.831) as assessed by the net reclassification index (0.303±−0.065; P<0.001) and integrated discrimination improvement (0.058±0.014; P<0.001). Correlation of individual urinary peptides with CKD stage and progression showed that the peptides that associated with CKD, irrespective of CKD stage or CKD progression, were either fragments of the major circulating proteins, suggesting failure of the glomerular filtration barrier sieving properties, or different collagen fragments, suggesting accumulation of intrarenal extracellular matrix. Furthermore, protein fragments associated with progression of CKD originated mostly from proteins related to inflammation and tissue repair. Results of this study suggest that urinary proteome analysis might significantly improve the current state of the art of CKD detection and outcome prediction and that identification of the urinary peptides allows insight into various ongoing pathophysiologic processes in CKD.

Keywords: CKD, renal progression, fibrosis, extracellular matrix, albuminuria, biomarker

CKD is often characterized by progressive renal failure. Approximately 5%–10% of the adult Western population suffers from CKD (i.e., an eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2).1 These individuals are at increased risk of death (particularly from cardiovascular causes) and progression to ESRD.2,3 The prognosis of CKD may be improved by early and more accurate detection and—where feasible and indicated—earlier treatment.4 CKD is currently diagnosed by the presence of proteinuria and/or changes in serum creatinine indicating decline in GFR.5 Although these tests are appropriate in patients with advanced CKD (stage >4), high interindividual variability at mild to moderate stages of disease is a major limitation for accurate early diagnosis and prognosis.6

This might be especially relevant in diabetic nephropathy (DN) representing one of the two major causes of CKD.1 Microalbuminuria (30–300 mg/24 h) is considered to be the best predictor of DN progression available in the clinic.7 However, it is increasingly shown to be, in contrast to what was previously believed, only moderately associated with the progression toward DN (recently reviewed by MacIsaac et al.).8 Reduction of eGFR is a clear indicator of CKD, but only at an advanced stage of disease, where success of treatment is severely compromised by advanced structural damage.9

There is thus a need to widen the focus of clinical care in CKD and to develop broader models that include novel pathways and risk markers apart from those related to the traditional urinary albumin pathway. This has initiated research to identify noninvasive urinary protein biomarkers of CKD that enable early detection and accurate prognosis.10–12 Urinary proteome analysis by capillary electrophoresis (CE) coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) has shown high reproducibility allowing the comparison of the protein and peptide content of thousands of samples.13 Hence, CE-MS has been used to analyze urine samples from patients with various renal and nonrenal diseases.14

CE-MS was used for the identification of a panel of 273 urinary peptide biomarkers of CKD (CKD273 classifier) by comparison of the urinary proteome of 379 healthy participants and 230 participants with CKD originating from a variety of renal diseases15,16 followed by the validation of these findings in independent cohorts.17,18 Small-scale studies in patients with diabetes showed that this classifier is able to predict the progression from normoalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria as well.19,20 These data show the presence of diagnostic/prognostic peptide-based markers of CKD in urine. In addition, these markers may enable insights into the pathophysiology of CKD.

Although the diagnostic potential of the CKD273 classifier for CKD has extensively been studied, its prognostic potential for CKD progression has not been adequately addressed. Hence, as the first aim of this study, we assessed the performance of the CKD273 classifier in CKD progression using a multicenter cohort of 1990 individuals with CKD, including 522 patients for whom data on progression were available. Because the CKD273 classifier was established using a dichotomous cut-off (i.e., by comparing healthy controls and participants with CKD), as a second aim we used this large cohort to determine whether a de novo analysis of correlating individual urinary peptides to progression of eGFR and CKD stage led to the discovery of additional urinary markers of CKD.

Results

Samples from participants with CKD were obtained from 19 different centers. Cross-sectional patient data are displayed in Table 1. For the identification of urinary peptides associated with the progression of CKD (follow-up cohort), we studied the urinary proteome of 522 patients (Table 2) from nine different medical centers for whom we obtained on average five follow-up visits measuring eGFR over a period of 54±28 months. The mean eGFR at baseline was 76±24 ml/min per 1.73 m2 with a mean change in eGFR per year follow-up of −1.24%±5.03%. The mean urinary albumin concentration of the patients in the follow-up cohort was 127±415 mg/L at baseline.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of the cross-sectional cohort

| Characteristic | Cross-Sectional Cohort (n=1990) | Mild-Moderate CKD (n=1669) | Advanced CKD (n=321) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (men/women) | 1260/730 | 1089/580 | 167/154 |

| Age (yr) | 57±13 | 56±12 | 61±13 |

| Urinary albumin (mg/L) | 308±833 | 229±731 | 731±1157 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.25±0.76 | 1.02±0.24 | 2.48±1.24 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 135±22 | 134±19 | 141±32 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 78±11 | 77±10 | 81±12 |

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min per 1.73m2) | 70±27 | 78±21 | 29±11 |

Data are presented as the mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical data of the follow-up cohort

| Characteristic | Follow-Up Cohort (n=522) | Fast Progressors (n=89) | Slow Progressors (n=433) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (men/women) | 298/224 | 51/38 | 247/186 |

| Age (yr) | 58±13 | 57±14 | 58±13 |

| Urinary albumin (mg/L) | 127±415 | 379±820 | 76±237 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.10±0.41 | 1.27±0.74 | 1.07±0.32 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 134±19 | 140±21 | 133±19 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 77±10 | 78±12 | 77±10 |

| Baseline eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 76±24 | 72±30 | 76±22 |

| eGFR after 3 yr (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 72±24 | 52±24 | 76±22 |

| Slope of eGFR (%) per yr | −1.24±5.03 | −9.29±4.48 | 0.42±3.21 |

Data are presented as the mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

The CKD273 Classifier Is Significantly Better than Urinary Albumin in Predicting CKD

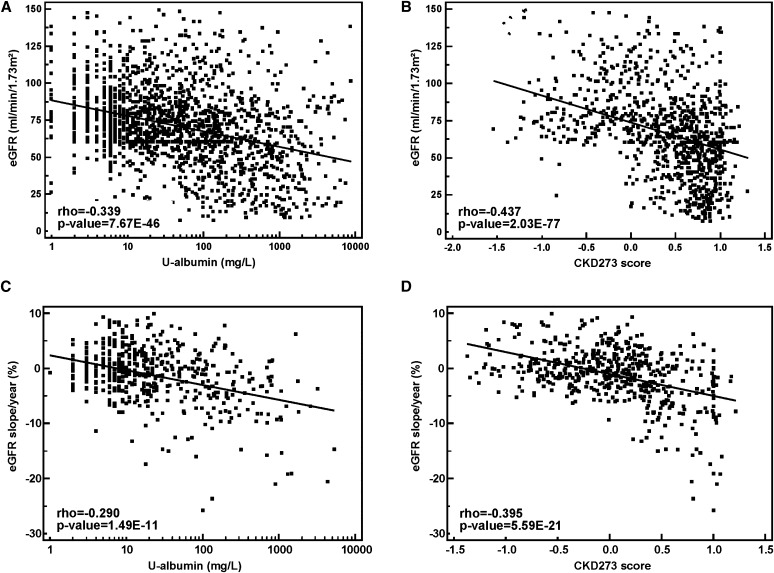

We first aimed to validate the diagnostic and prognostic potential of the previously established CKD273 classifier16 in this large cohort. A number of previous studies observed a significant correlation between urinary albumin levels and eGFR (e.g., Chou et al.21). We confirmed this correlation in the cross-sectional cohort: Urinary albumin correlated with eGFR with Rho=−0.34 (Figure 1A). However, the CKD273 classifier, based on 273 urinary peptides, displayed a significantly (P<0.001) stronger correlation with eGFR in this large cohort with Rho=−0.44 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Correlation analysis. Scatter diagrams of regression analyses with baseline eGFR and log urinary albumin (A) or CKD273 classifier (B) or with the slope of eGFR per year and log urinary albumin (C) or CKD273 classifier (D).

Furthermore, we had previously observed in small cohorts that the CKD273 classifier, although not initially developed to predict progression, also predicts progression of CKD.19,20 We therefore assessed whether the association of the CKD273 classifier with progression of CKD could be confirmed in this larger cohort (n=522), in which progression was defined as the percent decrease in eGFR per year. Albuminuria correlated with eGFR slope with a Rho=−0.29 (Figure 1C). The correlation of eGFR slope with the CKD273 classifier (Rho=−0.40, Figure 1D) was again markedly higher (P=0.05). For 258 of the 522 patients, albumin/creatinine ratios (ACRs) were available as well. For these 258 patients, the CKD273 classifier still displayed a higher correlation with eGFR slope than ACR (Rho values of −0.51 and −0.40, respectively). This is in agreement with the observation that we see a high correlation between urinary albumin (in milligrams per liter) and ACR (Rho=0.93, P<0.001, Supplemental Figure 1) in these 258 individuals.

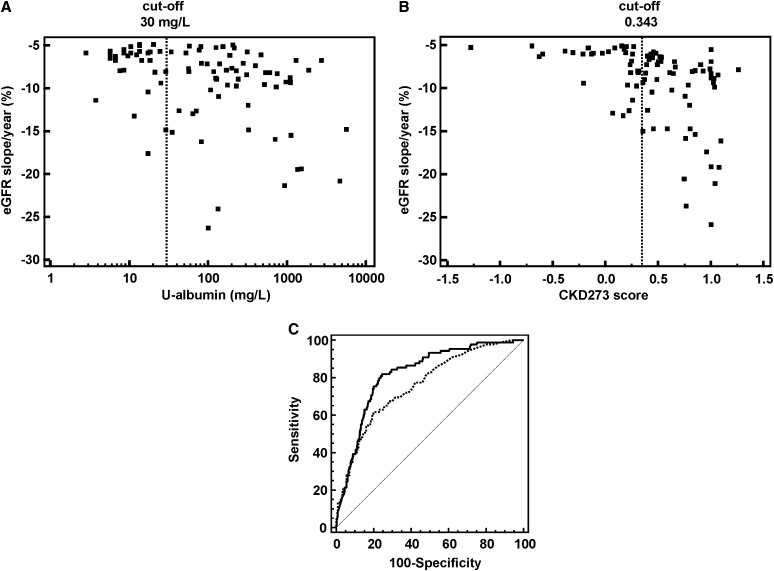

The identification of patients with CKD displaying fast progression of disease is a key issue in the management of CKD.22,23 To compare the performance of albuminuria and the CKD273 classifier concerning their prediction of CKD development, we defined patients who progress rapidly to CKD with an eGFR decline >−5% per year (for justification of this cut-off rapid progressors, please see the Concise Methods and Table 2). On the basis of this cut-off, we calculated the sensitivity of urinary albumin compared with the CKD273 classifier to detect patients that progress rapidly to CKD. Urinary albumin identified (cut-off: ≥30 mg/L; i.e., the presence of microalbuminuria) 58 of 89 (sensitivity: 65%) rapidly progressing patients, resulting in a misclassification of 35% (Figure 2A). By contrast, the CKD273 classifier (using the predefined cut-off of 0.343 for CKD16) detected 67 of 89 (sensitivity: 75%) progressors (only 25% misclassified, Figure 2B). The CKD273 classifier identified 17 of 31 (55%) of progressors that were missed by urinary albumin analysis. On the other hand, microalbuminuria identified only eight further progressors (36%), which were misclassified with the CKD273 classifier. Furthermore, the examination of the specificity resulted in a better value for the CKD273 classifier (79%) than for the microalbuminuria (73%). In total, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of the classification of these fast progressors displayed a significantly higher area under the curve (AUC) (P=0.01) for the CKD273 classifier than for albuminuria (AUC=0.821 and AUC=0.758, respectively) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Classification of fast progressors. (A and B) Regression analyses of patients with an eGFR slope decline of >−5% per year with log urinary albumin (A) or with CKD273-classifier scores (B). The cut-off (for microalbuminuria and the CKD273 classifier) is shown as a dotted line in each scatter diagram. (C) ROC analysis of the CKD273 classifier (black line) and albuminuria (dotted line) using patients with fast-progressing CKD (eGFR slope decline of >−5% per year).

To determine the contribution of the CKD273 classifier to the baseline covariates, we defined cases and controls according to the threshold (−5% per year) for eGFR decline. Compared with the validated risk factor–based model of the combination of baseline eGFR and albuminuria (AUC=0.758), the addition of the CKD273 classifier significantly and incrementally improved CKD risk prediction (AUC=0.831) as assessed by the net reclassification index (NRI) (0.303±−0.065; P<0.001) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) (0.058±0.014; P<0.001).

Correlation of Individual Urinary Peptides to Baseline eGFR

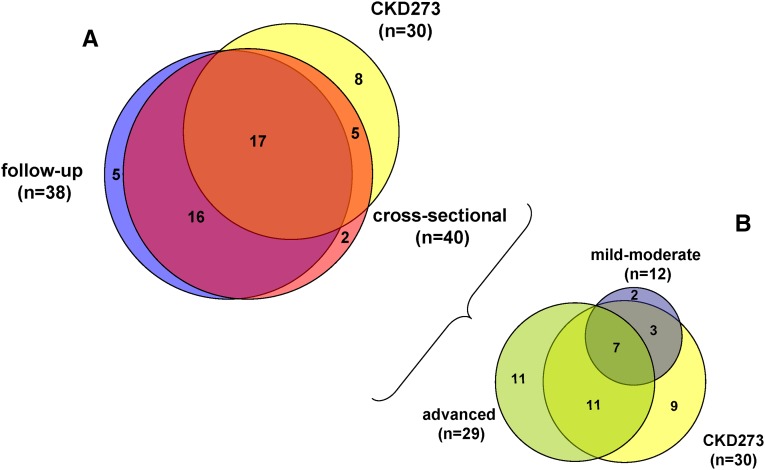

As a second aim, and because the CKD273 classifier was established using a dichotomous cut-off (i.e., presence or absence of CKD), we performed a de novo analysis determining the correlation of detected urinary peptides to eGFR and CKD stage at baseline. Correlation analysis led to the identification of a total of 179 urinary peptides, corresponding to 40 different proteins (Figure 3A, Table 3), which were significantly associated with baseline eGFR (Supplemental Table 1, columns B and C). Six urinary peptides displayed higher correlation factors than albuminuria (Rho=−0.34) but were lower than the correlation of the CKD273 classifier (Rho=−0.43, Figure 1B). Fragments of the blood-derived proteins β2-microglobulin, apoA-I, α1-antitrypsin, and serum albumin displayed a negative correlation, whereas two fragments of collagen α1(I) and (III) displayed a positive correlation. The most prominent peptides (top 25% and ≥3 peptides observed) correlating to baseline eGFR were fragments of α1-antitrypsin, apoA-I, β2-microglobulin, and collagen α1(I) chain.

Figure 3.

Overlap of proteins. (A) Venn diagram of proteins corresponding to peptides significantly associated with eGFR in patients of the cross-sectional cohort and with eGFR slope in patients of the follow-up cohort. Overlap with the CKD273-classifier is shown as well. (B) Venn diagram of proteins corresponding to peptides significantly associated with baseline eGFR in patients of the cross-sectional cohort with either mild-moderate or advanced stage CKD. Overlap with the CKD273 classifier is shown as well.

Table 3.

Proteins of which fragments show a significant correlation to baseline eGFR (cross-sectional) or eGFR slope per year (follow-up)

| Protein Name | Direction of Correlation | Related to Baseline eGFR | Related to Advanced CKD | Related to Mild-Moderate CKD | Related to eGFR Slope per yr | CKD273 Component | Relation to Stages of CKD | Role in CKD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen α1(I) chain | Positive | X | X | X | X | X | All stages | ECM remodeling |

| Collagen α1(III) chain | Positive | X | X | X | X | X | All stages | ECM remodeling |

| Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit γ | Positive | X | X | X | X | X | All stages | Homeostasis |

| ApoA-I | Negative | X | X | X | X | X | All stages | Proteinuria biomarker |

| Serum albumin | Negative | X | X | X | X | X | All stages | Proteinuria biomarker |

| α1-antitrypsin | Negative | X | X | X | X | X | All stages | Proteinuria biomarker, inflammation |

| β2-microglobulin | Negative | X | X | X | X | X | All stages | Proteinuria biomarker, inflammation |

| Uromodulin | Negative | X | X | Baseline | Homeostasis | |||

| Osteopontin | Negative | X | X | X | Mild-moderate | Inflammation, renin activation | ||

| Vesicular integral-membrane protein VIP36 | Negative | X | X | X | Mild-moderate, predictive | Inflammation, homeostasis | ||

| Peptidase inhibitor 16 | Negative | X | X | X | Mild-moderate, predictive | ECM remodeling | ||

| α1B-glycoprotein | Negative | X | X | X | X | Mild-moderate, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | |

| ProSAAS | Negative | X | X | X | X | Mild-moderate, predictive | Renin activation | |

| Collagen α1(II) chain | Positive | X | X | X | Advanced | ECM remodeling | ||

| Neurosecretory protein VGF | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced | Homeostasis | ||

| Mannan-binding lectin serine protease 2 | Negative | X | X | Advanced | Proteinuria biomarker, inflammation | |||

| Plasma protease C1 inhibitor | Negative | X | X | Advanced | Proteinuria biomarker, inflammation | |||

| Collagen α2(I) chain | Positive | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | ECM remodeling | |

| Plasminogen | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | ECM remodeling | ||

| PGH2 D-isomerase | Negative | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | GFR biomarker | |

| Annexin A1 | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Repair | ||

| Membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 1 | Positive | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Repair | |

| Clusterin | Negative | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Repair, inflammation | |

| CD99 antigen | Positive | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Inflammation | |

| Complement factor B | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Inflammation | ||

| Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 1 | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Inflammation | ||

| Protein S100-A9 | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Inflammation | ||

| α2-HS-glycoprotein | Negative | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | |

| Antithrombin-III | Negative | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | |

| ApoA-II | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | ||

| ApoA-IV | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | ||

| Fibrinogen α chain | Positive | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | |

| Hemoglobin subunit α | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | ||

| Hemoglobin subunit β | Negative | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | ||

| Transthyretin | Negative | X | X | X | X | Advanced, predictive | Proteinuria biomarker | |

| Collagen α1(XVI) chain | Positive | X | X | Predictive | ECM remodeling | |||

| Collagen α2(XI) chain | Positive | X | Predictive | ECM remodeling | ||||

| Ig κ chain C region | Negative | X | Predictive | Inflammation | ||||

| Ig γ-1 chain C region | Negative | X | X | Predictive | Inflammation | |||

| Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 | Negative | X | Predictive | Inflammation | ||||

| Cornulin | Negative | X | Predictive | Repair | ||||

| Zyxin | Negative | X | X | Predictive | Repair | |||

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Negative | X | X | Predictive | Repair, oxidative stress | |||

| Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 13 | Negative | X | Predictive | Unknown | ||||

| Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 9 | Negative | X | X | Predictive | Unknown | |||

| Total | 40 | 29 | 12 | 38 |

ECM, extracellular matrix.

In order to identify peptides specifically associated with different CKD stages (Supplemental Table 1, columns D–G), we divided the cohort into advanced stage (eGFR≤45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n=321) and mild-moderate stage (eGFR>45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n=1669) CKD. Of the 179 peptides associated with baseline eGFR (see above), 84 peptides (from 29 proteins, Figure 3B) also correlated with baseline eGFR in the advanced stage CKD cohort and 42 peptides (from 12 proteins, Figure 3B) in the mild-moderate CKD cohort. Only 18 peptides (from 7 proteins, Figure 3B) overlapped between the mild-moderate and advanced stage CKD subcohorts. Of the 84 peptides correlating with eGFR in advanced stage CKD, 57 peptides showed higher correlation factors than albuminuria (Rho=−0.18). In mild-moderate stage CKD, 19 peptides displayed stronger correlations to eGFR than albuminuria (Rho=−0.18). Collagen α1(I) chain peptides displayed the most prominent (25% top and ≥3 peptides observed) positive correlation to eGFR in mild-moderate stage CKD. Collagen fragments were still most prominent in advanced stage CKD, but two blood-derived peptides (apoA-I and β2-microglobulin fragments) were also among the most prominent ones in the advanced cohort, but correlated negatively to eGFR.

Correlation of Individual Urinary Peptides to Progression of CKD

Although previous studies suggest the potential prognostic abilities of the CKD273 classifier to predict increments in albuminuria19,20 and we observed here that the CKD273 classifier correlates to eGFR slope (see above), this classifier was established based on a comparison of healthy individuals and individuals with CKD.16 Hence, most likely, a number of individual peptides associated with the progression of CKD are not included in the classifier. We therefore studied the correlation of individual peptides with the percent slope eGFR per year in the 522 patients with CKD. We identified 124 peptides (from 38 proteins, Figure 3A) that significantly correlated with the slope of eGFR per year (Supplemental Table 1, columns H and I, highest Rho=−0.28). However, similar to the cross-sectional analysis, the CKD273 classifier still displayed the highest correlation with the eGFR slope (Figure 1D, Rho=−0.40). Two blood-derived proteins, α-antitrypsin and serum albumin, displayed the most prominent (25% top and ≥3 peptides observed) negative correlation to eGFR. Collagen fragments were not among the most prominent peptides that correlated to slope of eGFR per year.

A Large Overlap with the CKD273 Classifier Is Observed

The previously defined CKD273 classifier16 was derived from 241 different peptides (see the Concise Methods) corresponding to 30 different proteins. Of the 40 proteins identified in the cross-sectional cohort, 22 were already included in the classifier (Figure 3A, Table 3). The correlation analysis to eGFR slope led to the identification of 17 of 38 proteins already included in the classifier (Figure 3A). In total, 73% of the proteins of which fragments were already present in the CKD273 classifier were also observed in the correlation analyses to both baseline eGFR and/or eGFR decline.

When we considered different CKD stages, the overlap of proteins that were already included in the CKD273 classifier resulted in 18 of 29 proteins for the advanced CKD stage and 10 of 12 for the mild-moderate CKD stage (Figure 3B). In total, 70% of the proteins found in the CKD273-classifier also displayed correlation to advanced and/or mild-moderate CKD stages.

Discussion

Even if patients at risk of CKD and CKD progression can often be identified based on their primary disease, detection of individuals developing actual CKD is still troublesome. The currently used standard is elevated urinary albumin excretion (UAE), but the association between albuminuria and CKD has low sensitivity and specificity.24–26 Other urinary biomarkers, including neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and liver-type fatty acid-binding protein,21,27 showed even lower correlation factors with eGFR than urinary albumin. Although it was not initially developed to detect CKD progression, we have shown that the urinary proteome-based CKD273 classifier16 allows the identification of patients with diabetes who are at risk of progression to DN.19,20 We have also shown that a low CKD273 score is associated with slow progression of CKD in a small CKD cohort. Assessment of the potential of the CKD273 classifier to predict CKD and its progression mandated investigation in a large cohort.

Therefore, we studied the urinary proteome of a large cross-sectional cohort of 1990 participants with and without CKD, of which 522 participants had follow-up data on eGFR. The CKD273 classifier displayed a significantly stronger correlation with baseline eGFR and, more importantly, progression of CKD than albuminuria. This higher predictive value of the CKD273 classifier over urinary albumin became even clearer when considering patients with fast-progressing CKD (eGFR decline >−5% per year) in which the classifier detected 17 of 31 (55%) progressors missed by microalbuminuria. Because the multimarker CKD273 originally was defined based on the comparison of CKD controls and cases without consideration of progression of disease,16 further research is needed to adapt the cut-off of the CKD273 classifier for more precise diagnosis of CKD progression. However, in this study, we analyzed the correlation of individual urinary peptides to eGFR in more detail. Although a number of peptides not previously included in the CDK273 classifier were observed, their individual correlation coefficients were all lower than the correlation of the classifier with both baseline and slope eGFR. The majority of peptides with best correlation factors for baseline eGFR were collagen fragments (positive correlation) and fragments of blood-derived proteins (negative correlation), such as α1-antitrypsin and β2-microglobulin. However, prominent peptides correlating to eGFR slope were fragments of blood-derived proteins. Furthermore, we identified six urinary peptides that displayed a significantly stronger association with eGFR than albuminuria, four of which were already included in the CKD273 classifier. In addition, a high number of proteins (>70%) associated with either baseline eGFR mild-moderate or late stage CKD or progression of CKD were already included in the classifier. This most likely confers the previously observed predictive abilities of the classifier.19,20,28 Finally, the size of the cohort allowed the identification of urinary peptides specifically associated with mild-moderate or advanced stage CKD as well. To our knowledge, this is the first time that potential biomarkers were analyzed with respect to their association with different stages of CKD and hence may allow further stratification of patients with CKD.

Comparing the association of urinary peptides with the different subcohorts allows generation of a number of hypotheses on the development/progression of CKD based on the potential role of the molecules (Table 3). First, peptides associated with CKD irrespective of stage or rate of progression are mostly derived from proteins in the circulation with a variety of biologic functions, or from the extracellular matrix. This supports the general observation in progressive CKD of a combined failure of the glomerular filtration barrier and tubular function,29 in addition to excessive production of extracellular matrix.30

When analyzing peptides specifically associated with advanced stage and progression of CKD, failure of glomerular sieving still seems to be a major contributing factor; however, a number of proteins specifically associated with inflammation and, potentially, with repair also appear. This association is further strengthened when proteins that are almost only associated with progression of CKD are taken into account (Table 3).

Although the exact regulation in situ in the kidney based on the regulation observed in urine remains unknown, a number of proteins associated with inflammatory processes have already been found to be associated with CKD or conditions potentially linked to CKD (Table 3). The Ig κ chain C region was found to be altered in both visceral adipose tissue and plasma in preobese patients with diabetes compared with preobese participants without diabetes31,32 and increased in urine of early DN in type 2 diabetes.33 Protein S100-A9 was found to be involved in immune processes leading to microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes.34 Interestingly, pentoxifylline, an anti-inflammatory drug, lowered protein S100-A9 expression in patients with coronary artery disease35 and has antiproteinuric effects in CKD.36

These six proteins potentially associated with repair were correlated with CKD progression (Table 3). Of those, clusterin has been shown in an accelerated fibrosis model to protect against excessive fibrotic lesions.37 Cornulin is involved in cell cycle arrest at the G1/S checkpoint by upregulating the expression of p21(WAF/CIP).38 Progression of renal failure in a subtotal nephrectomy model in p21 knockout mice was slower and associated with a 5-fold increase in epithelial surface compared with wild-type mice, suggesting that epithelial repair is hampered in the wild-type strain. Epithelial cell cycle arrest has been identified as a major promotor of kidney fibrosis.39 It has been shown that in vitro activation of membrane-associated progesterone receptor component 1 inhibits rat and human liver myofibroblast trans-differentiation/proliferation.40 Annexin A1 is an important endogenous anti-inflammatory mediator, which is activated in response to cellular or tissue injury.41 Zyxin tightly controls the transcriptional activity of hepatocyte NF-1β (HNF-1β).42 Mutations in HNF-1β result in renal cysts and congenital kidney anomalies.43 In addition, during AKI, HNF-1β regulated the expression of genes important for homeostasis control, repair, and the state of epithelial cell differentiation.44

A shortcoming of our study is the fact that we could not obtain detailed data on the probable cause of CKD for all patients (we obtained the probable cause of CKD for 91.4% of the patients) and that we lacked information on comorbidities. Therefore, there may be a potential selection bias or unknown (comorbidity) confounder effect. This is caused by the multicenter retrospective character of the study. On the other hand, the absence of verification of effects of those confounders/or bias might be compensated by the high number of patients included from multiple centers. In conclusion, we validated in this large cohort that a previously established multipeptide biomarker CKD273 performed significantly better in detecting and predicting progression of CKD than the current clinical standard urinary albumin. In addition, we identified a number of individual urinary peptides that have significantly higher associations with baseline eGFR as well as with progression of eGFR than albuminuria. This demonstrates the advantage of using urinary peptidomics for assessing CKD diagnosis and prognosis. In addition, our study confirms the general observation in CKD of sieving failure of the glomerular filtration barrier and accumulation of extracellular matrix. Inflammatory and repair processes have clearly been associated with the development of CKD, which is reflected in the urinary proteome of patients displaying progressive kidney disease. Further studies will determine the clinical effect of the use of these individual urinary peptides as markers of disease activity and progression.

Concise Methods

Patient Data

Urine samples were obtained from 19 different centers: Austin Health and Northern Health (Melbourne, Australia; n=197), Steno Diabetes Center (Gentofte, Denmark; n=441), Medical School of Hanover (Hanover, Germany; n=128), Diabetes Centre of the Isala Clinics (Zwolle, The Netherlands; n=168), University Medical Center (Groningen, The Netherlands; n=215), Barbara Davis Center for Childhood (Denver, CO; n=82), Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA; n=112), RWTH University of Aachen (Aachen, Germany; n=78), BHF Glasgow Cardiovascular Research Centre (Glasgow, UK; n=93), RD Néphrologie (Montpellier, France; n=45), Human Nutrition and Metabolism Research and Training Centre (Graz, Austria; n=54), KU Leuven (Leuven, Belgium; n=84), University of Skopje (Skopje, Macedonia; n=18), KfH Renal Unit (Leipzig, Germany; n=26), Poliklinik (Munich, Germany; n=77), Charles University (Prague, Czech Republic; n=55), University of Alabama (Birmingham, AL; n=20), Quintiles Ltd. (London, UK; n=52), and University of Athens (Athens, Greece; n=45). In total, the cohort consisted of 223 apparently healthy individuals (eGFR≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and UAE<30 mg/L) and 1767 patients with different stages of CKD (eGFR<90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and/or UAE≥30 mg/L). The distribution among the different CKD stages was 20.9% stage 1, 50.1% stage 2, 13.5% stage 3A, 7.6% stage 3B, 6.2% stage 4, and 1.8% stage 5. The distribution of the probable causes of CKD was 52.9% DN (CKD in patients with diabetes), 24.5% GN, 6.4% vasculitis, 4.2% lupus nephritis, 2.2% nephrosclerosis, 1.3% interstitial nephritis, and 8.6% unknown CKDs. The study was designed and conducted fulfilling all of the requisites of the laws on the protection of individuals collaborating in medical research and was in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The protocols were approved by the local ethics committees.

Rapid progression was recently defined in the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes 2012 CKD guidelines as a sustained decline in eGFR of >5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year.45 The decline in eGFR in ml/min per 1.73m2 per year and the decrease in % eGFR slope per year in our cohort strongly correlated (Rho=0.98, P<0.001, see Supplemental Figure 2). Therefore, we defined patients that progress rapidly to CKD in our cohort as patients with a decrease in eGFR slope of >5% per year based on this strong correlation with GFR decline in ml/min per 1.73m2 per year. The differences in eGFR changes (slopes) for progressors versus nonprogressors are depicted in Supplemental Figure 3.

For the identification of markers of specific stages of CKD, we divided the cohort into patients with an eGFR (Chronic Kidney Disease in Epidemiology Collaboration formula)46 either lower or higher than 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Using 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 as a cut-off, instead of adopting a 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 cut-off, leads to the division of the cohort into patients with normal-to-moderately compromised renal function (CKD stages 1–3a) and patients with mostly advanced disease (CKD stages 3b–5).47

Sample Preparation

Urine samples were stored frozen at clinical centers (at −20°C in minimum) and shipped frozen for analysis. After arrival, they were prepared using a cut-off ultracentrifugation device to remove high molecular weight polypeptides and proteins, desalted, and then concentrated by lyophilization and stored at −20°C as described previously in detail.16 This procedure results in an average sample recovery of peptides and low molecular weight proteins of approximately 85%.48 Before CE-MS analysis, lyophilisates were resuspended in HPLC-grade water to a final protein concentration of 0.8 µg/µl checked by bicinchoninic acid assay (Interchim, Montluçon, France).

CE-MS Analysis

CE-MS analysis was performed as previously described.49 The limit of detection was approximately 1 fmol, and mass resolution was above 8000 enabling resolution of monoisotopic mass signals for z≤6. After charge deconvolution, mass deviation was <25 parts per million for monoisotopic resolution and <100 parts per million for unresolved peaks (z>6). The analytical precision was reported previously.16 To ensure high data consistency, one sample data set had to consist of a minimum of 800 peptides with a minimal MS resolution of 8000 and a minimal migration time interval of 10 minutes.

Data Processing

Mass spectral ion peaks representing identical molecules at different charge states were deconvoluted into single masses using MosaiquesVisu software.50 Reference signals of 1770 urinary polypeptides were used for CE time calibration by local regression. For normalization of analytical and urine dilution variances, MS signal intensities were normalized relative to 29 internal standard peptides generally present in at least 90% of all urine samples with small relative SD.51 For calibration, linear regression was performed. The obtained peak lists characterized each polypeptide by its molecular mass (in Daltons), normalized CE migration time (in minutes) and normalized signal intensity.

We only considered those peptides for which sequence information was available. To reduce the complexity of the study, we combined peptides with the same amino acid sequence, but displaying different modifications (like oxidized methionine or hydroxylated proline). This led for the CKD273 classifier to a reduction from 273 to 241 peptide markers.

Correlation and Statistical Analyses

Because the biomarker profiles across the samples are not normally distributed, we used the nonparametric Spearman's rank correlation coefficient for estimating the correlation of individual urinary peptides, the CKD273 classifier or albuminuria with baseline eGFR or progression (percentage slope) of eGFR. To estimate the percentage slope of eGFR per year, the reported eGFRs (average of five measurements with a minimum of two) over 54±28 months was used in a linear model of the decay between baseline and follow-up eGFR. Due to the fact that normally the eGFR is decreasing in the course of time, we defined this decrease as a negative eGFR slope per year (in percentages). The slope values were then correlated to the concentration of urinary albumin, to the CKD273 classifier values, and to a large array of urinary peptides. Correlations were considered significant with a correlation factor Rho>0.15 or < −0.15 or a P value <0.05. Sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the previously defined CKD273 classifier and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using ROC plots and the comparisons of the correlation coefficients were calculated with MedCalc (version 12.1.0.0, http://www.medcalc.be; MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium).52 To evaluate the added predictive ability of the CKD273 classifier, we calculated the NRI and the IDI as described in Pencina et al.53 The NRI and IDI are measures for how well the model with the new predictor reclassifies the participants with events and nonevents and answers questions such as whether the patients experiencing an event go up in risk and those without events go down in risk. In order to see the additional contribution of the CKD273 classifier to the baseline covariates, we considered a definition of the cases and controls according to the threshold (−5% per year) for the eGFR calculated slope. The outcome is defined by the variable Diagnosisslope-5%/year. The classic-model (Diagnosisslope-5%/year approximately log10[UAEB]+GFRB) was compared with the new model including the CKD273 classifier (Diagnosisslope-5%/year approximately log10[UAEB]+GFRB+CKD273). The formulas for the calculation are as follows (Equations 1 and 2):

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

We calculated the AUC, the NRI, and IDI considering the risk categories <6%, 6%–19%, and ≥20%, using baseline urinary albumin excretion (UAEB), baseline eGFR (GFRB), and CKD273 scores.

Disclosures

J.P.S., A.Ar., J.B., J.J., A.O., G.S., H.M., and R.V. are members of the European Uraemic Toxin Working Group. H.M. is cofounder and a shareholder of mosaiques diagnostics GmbH. P.Z., M.D., and J.S. are employees of mosaiques diagnostics GmbH. J.P.S. was temporarily employed by mosaiques diagnostics GmbH during this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by European Union funding through EuroKUP (Kidney and Urine Proteomics) COSTAction (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) BM0702, SysKID (Systems Biology towards Novel Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Treatment) FP7-HEALTH-F2-2009-241544, EU-MASCARA (Markers for Subclinical Cardiovascular Risk Assessment) FP7-HEALTH-2011-F2-278249, and HoMAGE (Heart–omics in Aging) FP7-HEALTH-F7-305507. A.O. was supported by funds from the Carlos III Institute of Health and the Spanish Government (RD012/0021 RETIC REDINREN and PI13/00047). The work of J.P.S. was partly supported by the Midi-Pyrenees region. J.A.S. was supported in part by the European Research Council (Advanced Researcher Grant 2011-294713-EPLORE), the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen, and the Ministry of the Flemish Community (Brussels, Belgium) (Grants G.0881.13 and G.088013). The International Zinc and Lead Research Organization currently support the Studies Coordinating Centre in Leuven.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Can the Urinary Peptidome Outperform Creatinine and Albumin to Predict Renal Function Decline?,” on pages 1760–1761.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014050423/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, Saran R, Wang AY, Yang CW: Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 382: 260–272, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Bertenthal D, Bacchetti P, Garg AX, Kaufman JS, Walter LC, Mehta KM, Steinman MA, Allon M, McClellan WM, Landefeld CS: Age affects outcomes in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2758–2765, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Culleton B, House A, Rabbat C, Fok M, McAlister F, Garg AX: Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: A systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2034–2047, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J, Cohen EP, Collins AJ, Eckardt KU, Nahas ME, Jaber BL, Jadoul M, Levin A, Powe NR, Rossert J, Wheeler DC, Lameire N, Eknoyan G: Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: Approaches and initiatives - A position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int 72: 247–259, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, De Zeeuw D, Hostetter TH, Lameire N, Eknoyan G: Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 67: 2089–2100, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller WG, Bruns DE, Hortin GL, Sandberg S, Aakre KM, McQueen MJ, Itoh Y, Lieske JC, Seccombe DW, Jones G, Bunk DM, Curhan GC, Narva AS, National Kidney Disease Education Program-IFCC Working Group on Standardization of Albumin in Urine : Current issues in measurement and reporting of urinary albumin excretion. Clin Chem 55: 24–38, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossing P: Prediction, progression and prevention of diabetic nephropathy. The Minkowski Lecture 2005. Diabetologia 49: 11–19, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacIsaac RJ, Ekinci EI, Jerums G: ‘Progressive diabetic nephropathy. How useful is microalbuminuria?: Contra’. Kidney Int 86: 50–57, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S, RENAAL Study Investigators : Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matheson A, Willcox MD, Flanagan J, Walsh BJ: Urinary biomarkers involved in type 2 diabetes: A review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 26: 150–171, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerums G, Premaratne E, Panagiotopoulos S, Clarke S, Power DA, MacIsaac RJ: New and old markers of progression of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 82[Suppl 1]: S30–S37, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steinke JM: The natural progression of kidney injury in young type 1 diabetic patients. Curr Diab Rep 9: 473–479, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mischak H, Coon JJ, Novak J, Weissinger EM, Schanstra JP, Dominiczak AF: Capillary electrophoresis-mass spectrometry as a powerful tool in biomarker discovery and clinical diagnosis: An update of recent developments. Mass Spectrom Rev 28: 703–724, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mischak H, Schanstra JP: CE-MS in biomarker discovery, validation, and clinical application. Proteomics Clin Appl 5: 9–23, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossing K, Mischak H, Dakna M, Zürbig P, Novak J, Julian BA, Good DM, Coon JJ, Tarnow L, Rossing P, PREDICTIONS Network : Urinary proteomics in diabetes and CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1283–1290, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Good DM, Zürbig P, Argilés A, Bauer HW, Behrens G, Coon JJ, Dakna M, Decramer S, Delles C, Dominiczak AF, Ehrich JH, Eitner F, Fliser D, Frommberger M, Ganser A, Girolami MA, Golovko I, Gwinner W, Haubitz M, Herget-Rosenthal S, Jankowski J, Jahn H, Jerums G, Julian BA, Kellmann M, Kliem V, Kolch W, Krolewski AS, Luppi M, Massy Z, Melter M, Neusüss C, Novak J, Peter K, Rossing K, Rupprecht H, Schanstra JP, Schiffer E, Stolzenburg JU, Tarnow L, Theodorescu D, Thongboonkerd V, Vanholder R, Weissinger EM, Mischak H, Schmitt-Kopplin P: Naturally occurring human urinary peptides for use in diagnosis of chronic kidney disease. Mol Cell Proteomics 9: 2424–2437, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alkhalaf A, Zürbig P, Bakker SJ, Bilo HJ, Cerna M, Fischer C, Fuchs S, Janssen B, Medek K, Mischak H, Roob JM, Rossing K, Rossing P, Rychlík I, Sourij H, Tiran B, Winklhofer-Roob BM, Navis GJ, PREDICTIONS Group : Multicentric validation of proteomic biomarkers in urine specific for diabetic nephropathy. PLoS ONE 5: e13421, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molin L, Seraglia R, Lapolla A, Ragazzi E, Gonzalez J, Vlahou A, Schanstra JP, Albalat A, Dakna M, Siwy J, Jankowski J, Bitsika V, Mischak H, Zürbig P, Traldi P: A comparison between MALDI-MS and CE-MS data for biomarker assessment in chronic kidney diseases. J Proteomics 75: 5888–5897, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roscioni SS, de Zeeuw D, Hellemons ME, Mischak H, Zürbig P, Bakker SJ, Gansevoort RT, Reinhard H, Persson F, Lajer M, Rossing P, Lambers Heerspink HJ: A urinary peptide biomarker set predicts worsening of albuminuria in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 56: 259–267, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zürbig P, Jerums G, Hovind P, Macisaac RJ, Mischak H, Nielsen SE, Panagiotopoulos S, Persson F, Rossing P: Urinary proteomics for early diagnosis in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 61: 3304–3313, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chou KM, Lee CC, Chen CH, Sun CY: Clinical value of NGAL, L-FABP and albuminuria in predicting GFR decline in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. PLoS ONE 8: e54863, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spasovski G, Ortiz A, Vanholder R, El Nahas M: Proteomics in chronic kidney disease: The issues clinical nephrologists need an answer for. Proteomics Clin Appl 5: 233–240, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taal MW, Brenner BM: Predicting initiation and progression of chronic kidney disease: Developing renal risk scores. Kidney Int 70: 1694–1705, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caramori ML, Fioretto P, Mauer M: The need for early predictors of diabetic nephropathy risk: Is albumin excretion rate sufficient? Diabetes 49: 1399–1408, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macisaac RJ, Jerums G: Diabetic kidney disease with and without albuminuria. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 20: 246–257, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perkins BA, Ficociello LH, Roshan B, Warram JH, Krolewski AS: In patients with type 1 diabetes and new-onset microalbuminuria the development of advanced chronic kidney disease may not require progression to proteinuria. Kidney Int 77: 57–64, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu KD, Yang W, Anderson AH, Feldman HI, Demirjian S, Hamano T, He J, Lash J, Lustigova E, Rosas SE, Simonson MS, Tao K, Hsu CY, Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study investigators : Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels do not improve risk prediction of progressive chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 83: 909–914, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Argilés Á, Siwy J, Duranton F, Gayrard N, Dakna M, Lundin U, Osaba L, Delles C, Mourad G, Weinberger KM, Mischak H: CKD273, a new proteomics classifier assessing CKD and its prognosis. PLoS ONE 8: e62837, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suh JH, Miner JH: The glomerular basement membrane as a barrier to albumin. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 470–477, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossing K, Mischak H, Rossing P, Schanstra JP, Wiseman A, Maahs DM: The urinary proteome in diabetes and diabetes-associated complications: New ways to assess disease progression and evaluate therapy. Proteomics Clin Appl 2: 997–1007, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murri M, Insenser M, Bernal-Lopez MR, Perez-Martinez P, Escobar-Morreale HF, Tinahones FJ: Proteomic analysis of visceral adipose tissue in pre-obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 376: 99–106, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Awartani F: Serum immunoglobulin levels in type 2 diabetes patients with chronic periodontitis. J Contemp Dent Pract 11:001-008, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellei E, Rossi E, Lucchi L, Uggeri S, Albertazzi A, Tomasi A, Iannone A: Proteomic analysis of early urinary biomarkers of renal changes in type 2 diabetic patients. Proteomics Clin Appl 2: 478–491, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caseiro A, Ferreira R, Padrão A, Quintaneiro C, Pereira A, Marinheiro R, Vitorino R, Amado F: Salivary proteome and peptidome profiling in type 1 diabetes mellitus using a quantitative approach. J Proteome Res 12: 1700–1709, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shamsara J, Behravan J, Falsoleiman H, Mohammadpour AH, Rendeirs J, Ramezani M: Pentoxifylline administration changes protein expression profile of coronary artery disease patients. Gene 487: 107–111, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navarro JF, Mora C, Muros M, García J: Additive antiproteinuric effect of pentoxifylline in patients with type 2 diabetes under angiotensin II receptor blockade: A short-term, randomized, controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2119–2126, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jung GS, Kim MK, Jung YA, Kim HS, Park IS, Min BH, Lee KU, Kim JG, Park KG, Lee IK: Clusterin attenuates the development of renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 73–85, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen K, Li Y, Dai Y, Li J, Qin Y, Zhu Y, Zeng T, Ban X, Fu L, Guan XY: Characterization of tumor suppressive function of cornulin in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE 8: e68838, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L, Besschetnova TY, Brooks CR, Shah JV, Bonventre JV: Epithelial cell cycle arrest in G2/M mediates kidney fibrosis after injury. Nat Med 16:535–543, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marek CJ, Wallace K, Durward E, Koruth M, Leel V, Leiper LJ, Wright MC: Low affinity glucocorticoid binding site ligands as potential anti-fibrogenics. Comp Hepatol 8: 1, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Facio FN, Jr, Sena AA, Araújo LP, Mendes GE, Castro I, Luz MA, Yu L, Oliani SM, Burdmann EA: Annexin 1 mimetic peptide protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J Mol Med (Berl) 89: 51–63, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi YH, McNally BT, Igarashi P: Zyxin regulates migration of renal epithelial cells through activation of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1β. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F100–F110, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Decramer S, Parant O, Beaufils S, Clauin S, Guillou C, Kessler S, Aziza J, Bandin F, Schanstra JP, Bellanné-Chantelot C: Anomalies of the TCF2 gene are the main cause of fetal bilateral hyperechogenic kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 923–933, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Faguer S, Mayeur N, Casemayou A, Pageaud AL, Courtellemont C, Cartery C, Fournie GJ, Schanstra JP, Tack I, Bascands JL, Chauveau D: Hnf-1β transcription factor is an early hif-1α-independent marker of epithelial hypoxia and controls renal repair. PLoS ONE 8: e63585, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levin A, Stevens PE: Summary of KDIGO 2012 CKD Guideline: Behind the scenes, need for guidance, and a framework for moving forward. Kidney Int 85: 49–61, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eckardt KU, Coresh J, Devuyst O, Johnson RJ, Köttgen A, Levey AS, Levin A: Evolving importance of kidney disease: From subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 382: 158–169, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haubitz M, Good DM, Woywodt A, Haller H, Rupprecht H, Theodorescu D, Dakna M, Coon JJ, Mischak H: Identification and validation of urinary biomarkers for differential diagnosis and evaluation of therapeutic intervention in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Mol Cell Proteomics 8: 2296–2307, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theodorescu D, Wittke S, Ross MM, Walden M, Conaway M, Just I, Mischak H, Frierson HF: Discovery and validation of new protein biomarkers for urothelial cancer: A prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol 7: f230–240, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neuhoff N, Kaiser T, Wittke S, Krebs R, Pitt A, Burchard A, Sundmacher A, Schlegelberger B, Kolch W, Mischak H: Mass spectrometry for the detection of differentially expressed proteins: A comparison of surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization and capillary electrophoresis/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 18: 149–156, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jantos-Siwy J, Schiffer E, Brand K, Schumann G, Rossing K, Delles C, Mischak H, Metzger J: Quantitative urinary proteome analysis for biomarker evaluation in chronic kidney disease. J Proteome Res 8: 268–281, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeLeo JM: Receiver operating characteristic laboratory (ROCLAB): Software for developing decision strategies that account for uncertainty. In: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Uncertainty Modeling and Analysis, College Park, MD, IEEE, 1993, pp 318–325 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Vasan RS: Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: From area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 27: 157–172, discussion 207–212, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.