Abstract

The putative occurrence of methane in the Martian atmosphere has had a major influence on the exploration of Mars, especially by the implication of active biology. The occurrence has not been borne out by measurements of atmosphere by the MSL rover Curiosity but, as on Earth, methane on Mars is most likely in the subsurface of the crust. Serpentinization of olivine-bearing rocks, to yield hydrogen that may further react with carbon-bearing species, has been widely invoked as a source of methane on Mars, but this possibility has not hitherto been tested. Here we show that some Martian meteorites, representing basic igneous rocks, liberate a methane-rich volatile component on crushing. The occurrence of methane in Martian rock samples adds strong weight to models whereby any life on Mars is/was likely to be resident in a subsurface habitat, where methane could be a source of energy and carbon for microbial activity.

Extremophiles on Earth are known to respire methane, and the potential existence of methane on Mars indicates similar organisms could survive there. Here, the authors present data from Martian meteorites confirming the presence of methane, indicating that a habitat capable of supporting organisms exists on Mars.

Extremophiles on Earth are known to respire methane, and the potential existence of methane on Mars indicates similar organisms could survive there. Here, the authors present data from Martian meteorites confirming the presence of methane, indicating that a habitat capable of supporting organisms exists on Mars.

On Earth, methane (CH4) can have a microbial origin (methanogenesis) and/or is a source of carbon and metabolic energy for microbes (methanotrophs); hence, the putative occurrence of methane in the Martian atmosphere1,2 attracted much attention for its possible biological significance3,4,5,6. However, alternative treatments of the data have raised uncertainty about the occurrence of methane7,8. Nevertheless, analysis of the local Martian atmosphere by the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover Curiosity has detected transient methane anomalies9. Any life on Mars is likely to be in the subsurface10,11,12, and the potential remains for a subsurface habitat based on methane derived inorganically from low-temperature (<100 °C) reactions of water or carbon-bearing fluids with basalt and other rocks13. The serpentinization of olivine and hydration of pyroxene in basalt and other rocks in the presence of water yields hydrogen, which in turn may interact with carbon-bearing species such as carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2) and formic acid (HCOOH) to yield methane3,14,15,16.

Methane in submarine terrestrial basalts can support a microbial population17. There are also large volumes of basalt and other basic igneous rocks on Mars18. Olivine-rich volcanic rocks have been identified in each of the Noachian, Hesperian and Amazonian successions, and olivine is a significant component of Martian sediment, unlike on Earth19. Pyroxene is volumetrically greater than olivine within the Martian crust, and is potentially important as, in addition to a source of hydrogen20, on Earth altered pyroxenes harbour life21. Widespread hydrated silicates on Mars imply extensive water–rock interaction22, and the opportunities for gas-generating alteration in the Martian crust should, therefore, be widespread. The olivine in Martian meteorites, including all of the nakhlites and many of the shergottites, has experienced aqueous alteration including serpentinization23. Serpentinization of olivine at some stage in the past is also recorded on Mars through orbital measurements, using MRO-CRISM24,25 and could be extensive10. Martian meteorites contain magmatic carbon, carbonate carbon from interaction with Martian atmospheric CO2 and organic carbon from meteoritic infall26. We anticipate that all of these carbon-bearing components could become entrained in hydration reactions, which alter olivine and pyroxene, and contribute to methane generation.

There is an opportunity to assess whether Martian rocks could be releasing methane by the analysis of Martian meteorites. The volatile components of the meteorites must be derived from a mixture of sources, including Martian atmosphere, Martian magmatism, Martian crustal processes and terrestrial contamination27. All meteorites from Mars have a bulk basic or ultrabasic igneous composition18; hence, it is possible that some of them have generated methane upon aqueous alteration before ejection from Mars. A range of other fluid-related signatures obtained from Martian meteorites (for example, refs 28, 29, 30, 31) implies that methane generated from alteration on Mars could survive the journey to Earth and be amenable to extraction.

The analysis of entrapped gas has been undertaken on six Martian meteorites (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Note 1). These were nakhlites Nakhla, Y 000749, NWA 5790 and MIL 03346, and the shergottites Zagami and LA002. The nakhlites are known to have experienced extensive alteration in a highly oxidizing environment on Mars, and many shergottites show evidence of some interaction with oxidizing fluids in the subsurface28. Nakhla and the shergottites do not exhibit significant terrestrial weathering28,32; however, MIL 03346, NWA 5790 and Y 000749 show evidence of significant aqueous alteration on both Mars and Earth31,33,34,35. With the exception of NWA 5790, the samples were from meteorite interiors, to mitigate against terrestrial contamination. All samples excluded any fusion crust, so they should not have been thermally altered during atmospheric entry (Supplementary Note 2), and fluid inclusions should remain intact36. The meteorites were analysed using the crush-fast scan technique, in which incremental crushing at room temperature liberates gases trapped in fluid inclusions and crystal boundaries, into a quadrupole mass spectrometer37. Each crush yields a burst of gas that is individually analysed. Gas compositions are calibrated against standard gas mixtures and fluid inclusion standards of known composition. This technique has the advantage that it does not involve the liberation of gas through heating, in which carbon-bearing components could be converted into a different form. Thus, carbonates, which would yield a strongly CO2-rich signature due to thermal breakdown upon heating, can yield a CH4-rich signature if that is the predominant entrapped gas. Analyses of gases in meteorites following the heating of samples provide valuable information, including the isotopic composition of the carbon reservoir38, and liberation of entrained hydrocarbons28, but preclude detailed determination of the indigenous carbon-bearing gas species.

Results

Gases in Martian meteorites

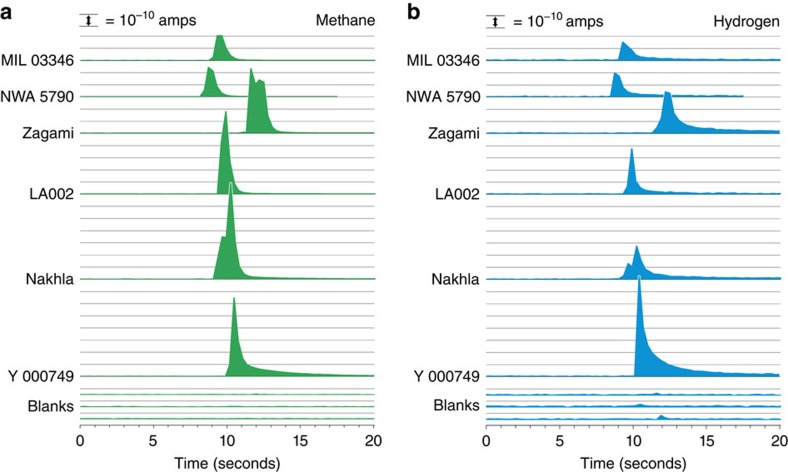

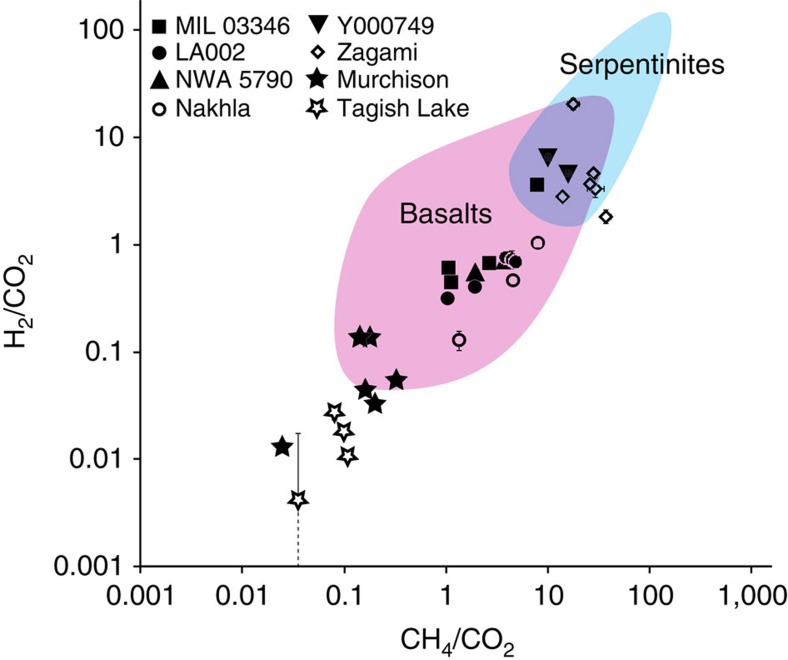

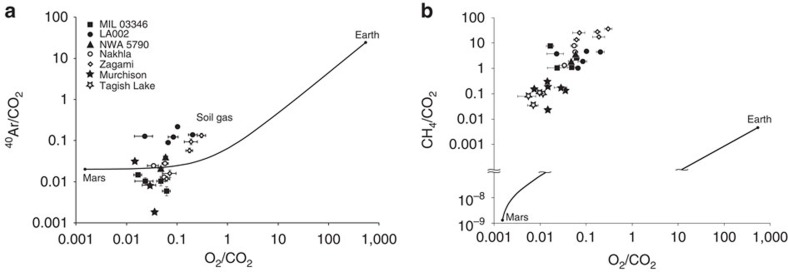

The gases released were dominated by CH4, CO2, H2, N2, with traces of O2 and Ar. The highest yields were from Nakhla and LA 002 and lowest from NWA 5790 and MIL 03346 (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 2). The CH4/CO2 ratio varies from about 3 (LA002, NWA 5790, MIL 03346) to 23 (Zagami). The H2/CO2 ratio varies from 0.5 to 7. These values are all in the same range as those for terrestrial basalts (Fig. 2). The lower CH4/CO2 ratio for Martian samples compared with terrestrial serpentinites39 may reflect an abundance of CO2 in the Martian crust, evidenced by carbonation observed in meteorites40 and from orbit41. Variations in H2/CH4 ratio imply varying degrees of interaction between H2 and available carbon, but would also reflect differential retention of H2 and CH4 in the rock. The artificial generation of CH4 during application of the steel crushing device was monitored using procedural blanks of heat-degassed basalt, as previous studies showed that crushing creates traces of CH4 (refs 42, 43, 44). The contributions of the blanks to the methane found in the meteorite samples (Fig. 1) were 0.03 to 0.1% (mean 0.07%) for the mean blank, and 0.7 to 2.3% for the maximum blank of mean value plus s.d. The contribution of the blank to the methane measured in the Nakhla sample is 0.05%. Normalization of gases to CO2 and comparison with the composition of the terrestrial and Martian atmosphere27 allows the plotting of data relative to mixing lines between the two atmospheres (Fig. 3). A plot of argon against oxygen shows that the meteorite data plots much closer to the Martian atmosphere composition with Ar/O2 ratio ∼13. Contamination by the terrestrial atmosphere, which has Ar/O2 ratio ∼0.05, would shift the data along the mixing line away from the Martian end member. The proximity of the meteorite data to the Martian end member indicates that terrestrial contamination is limited, although the composition of terrestrial soil gas lies closer to the meteorite data than the composition of the terrestrial atmosphere. However, a plot of methane against oxygen shows meteorite data well removed from the atmospheric mixing line (Fig. 3). There is substantially more methane than in the Martian atmosphere, strongly suggesting a mechanism for methane generation in the Martian crust. An alternative explanation could be that the methane composition of the atmosphere was much higher when the nakhlites were being altered about 600 Myr ago, but the similar enrichment in terrestrial basalts suggests that a crustal origin is more likely. The scatter in the data reflects variations in mineralogy including proportions of alteration products, and gas retention, and is comparable with the scatter found in terrestrial basalts45, as shown in Fig. 2.

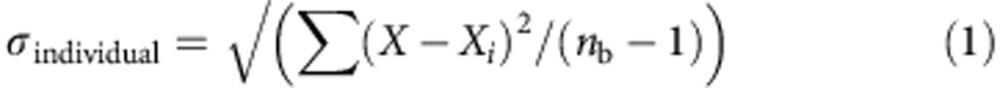

Figure 1. Output from crush fast scan-mass spectrometry analyses of Martian meteorites.

Output shown from during CH4 (a) and H2 (b) release. Output is over 80 cycles (∼20–25 s) at m/z=15 and m/z=2, representing ionized CH3+ and H2+ during sample crushing. The ionized volatiles produce an instantaneous current in the detector proportional to their amount. The signals from Martian meteorites are shown above quartz blanks, in units of 10−10 amps above background. Hydrogen generates more current than an equal volume of methane because of a difference in sensitivity factor. Doublet peaks may represent gas release from successively crushed inclusions. Peaks are displaced laterally for clarity only. The meteorite methane peak signals are 2 to 3 orders of magnitude higher than the highest signal from the blank.

Figure 2. Comparison of gas compositions in Martian meteorites with those in terrestrial samples and carbonaceous chondrites.

The terrestrial samples are from basalts and terrestrial fluids. Each point corresponds to one burst of volatiles produced by an increment of crushing. Gases of interest are normalized to CO2. All Martian meteorites plot within the data field for terrestrial basalts; both are more methane-rich than terrestrial fluids and carbonaceous chondrites. Errors are obtained from molar volumes of individual species±one weighted s.d. (see Methods). One Tagish Lake analysis has large error bar, but in most cases error bars are smaller than data symbols. Data sources: terrestrial serpentinites39, and terrestrial basalts45, both crushed in same manner as the meteorites.

Figure 3. Comparison of Martian meteorite data with mixing lines between Martian and terrestrial atmospheres.

Data are from ref. 27. Each point corresponds to one burst of volatiles produced by an increment of crushing. Gases of interest are normalized to CO2. Ar/O2 plot (a) implies a primary Martian signature with limited contamination from the terrestrial atmosphere. CH4/O2 plot (b) implies substantial enrichment in CH4 by a non-atmospheric source, most likely in the Martian crust. The Ar/O2 meteorite data lie close to the composition of terrestrial soil gas, but the CH4 enrichment excludes soil gas as a major contaminant. Together the plots show that contamination from terrestrial atmosphere was minimal, and that the gas signature is crustal rather than atmospheric. Errors are obtained from molar volumes of individual species±one weighted s.d. (see Methods).

Discussion

The gases released by crushing are likely to be resident within fluid inclusions, which have been observed in nakhlite meteorites29, and crystal boundaries. The relatively high hydrogen and methane contents are consistent with the aqueous alteration of olivine and pyroxene in the meteorites. Nakhlites in particular are known to have experienced significant aqueous alteration on Mars, including the formation of carbonates, sulfates and hydrous silicates23. Olivines found within the nakhlites and other Martian meteorites are iron-rich compared with typical terrestrial olivines, and are therefore particularly susceptible to serpentinization reactions3,14. Indeed, traces of serpentine have been detected in the Yamato 000593 meteorite23. Therefore, hydrogen and methane should have been generated from these rocks on Mars, just as they are in comparable rocks on Earth. There is a strong implication that the gases measured in this study are predominantly Martian in origin.

Several other lines of evidence suggest that the gases had a Martian origin.

First, the samples that had experienced most alteration, both on Mars and Earth, have the lowest gas yields. This suggests that alteration had facilitated gas release, either during the alteration process or during subsequent history. This does not preclude the adsorption of gas after arrival on Earth, but the much greater gas yields from the less altered meteorites, including the shergottites, implies that their gas signatures are largely Martian in origin.

Second, the gas assemblages in the meteorites compare closely with those from terrestrial basalts, that is, the meteorites contain those gases expected from basaltic rocks (Fig. 2), suggesting a similar genesis by alteration of the basalt mineralogy. Measurements on terrestrial basalts and serpentinites show that they consistently yield gas with high CH4/CO2 ratios, commonly >1 (refs 39, 45). Many other data sets measured by the same technique yield very different assemblages37. These data sets underline the CH4-rich signature (CH4/CO2>5) for the meteorite basalts. If the gas assemblage was modified on Mars, for example by uptake of atmospheric CO2 in secondary carbonates, or during the shock of meteorite ejection26, the CH4/CO2 ratio would have been lowered from the original composition, further emphasizing the significance of the CH4 as a primary signature of basalt alteration.

Third, samples of a group of meteorites with a very different composition, carbonaceous chondrites (Murchison, Tagish Lake), yield a distinct gas assemblage, characterized by 1 to 2 orders of magnitude lower CH4/CO2 and H2/CO2 (Fig. 2; data from this study, in Supplementary Table 2). Both groups of meteorite have experienced low-temperature alteration of silicates, probably at low water–rock ratios46. The carbonaceous chondrites differ in containing organic carbon at the percentage level, orders of magnitude greater than in the Martian meteorites. This suggests that the gas assemblages are a product of the meteorite mineralogy, rather than a characteristic of the terrestrial environment in which the meteorites arrived.

There is evidence for the adsorption of terrestrial air47 and for a terrestrial component of carbon26,28 in Martian meteorites. The incorporation of air in surface environments on Earth can result in measurable levels of oxygen in the gases liberated on crushing, including in samples of oxidized basalt45. Traces of oxygen occur in the meteorites, most abundantly in those meteorites known to have experienced terrestrial weathering, MIL 03346 and NWA 5790. This observation indicates that some interaction with terrestrial air may have occurred, but terrestrial air or soil gas would not contribute the methane-rich gas assemblage. It might be argued that some interaction with water could have occurred since arrival on Earth. However, in the gas-rich Nakhla and Zagami samples, it is unrealistic to envisage this gas generation on the timescales since they fell to Earth (1911, 1962). Traces of oxygen also occur in the Martian atmosphere, but the meteorites do not exhibit the high Ar content in the Martian atmosphere. We can estimate the possible degree of contamination, based on the oxygen contents of the meteorite gases. One meteorite (Y000749) has no oxygen, and effectively represents a Martian basalt end member, while the terrestrial atmosphere has ∼21%. The percentage oxygen in the other meteorites (ranging up to 0.72%) would be the equivalent of up to 3.4% contamination by the terrestrial atmosphere.

The availability of methane and hydrogen is critical to the potential of the Martian crust as a habitat for microbial life. The hostile Martian surface is probably less habitable than the subsurface, and several scenarios have been proposed for deep Martian life10,11,12. The gases would be most concentrated in subsurface environments such as fracture systems and basalt lava vesicles, where they could support a deep biosphere, as envisaged in basalts and other crystalline basement rocks on Earth14,48. Methane supports the deep biosphere on Earth, including in basalt where, critically for a Martian analogue, the methane is used by anaerobic microbes and may be partially coupled to the microbial cycling of sulfur17. The evidence presented here indicates that a methane-bearing subsurface habitat is similarly available on Mars. Whether or not the habitat has been occupied remains to be determined.

Methods

Sample processing

Extraction and analysis of volatiles was performed by the crush-fast scan (CFS) method37,49, which offers very low detection limits50. Samples the size of a match head (that is, milligram to gram scale) were first dried below 100 °C. Samples were then loaded into a crushing chamber then held under vacuum (∼10−8 Torr) for 72 h. The samples were crushed in swift increments, with each crush producing a burst of mixed volatiles which is individually analysed. A typical sample size of about 250 mg (one or two 3-mm grains) released 4–10 bursts of volatiles (up to ∼2 × 10−11 mol) into the vacuum chamber, which remained there for 8–10 analyser scans (∼2 s) before removal by the vacuum pump. This method does not require a carrier gas and volatiles are not separated from each other but released simultaneously into the chamber. Each individual crush was analysed for H2, He, CH4, N2, O2, Ar and CO2, using a Pfeiffer Prisma ‘residual-gas' quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in fast-scan, peak-hopping mode at room temperature. In multiple ion detection mode, both isotopic peaks and fragmentation peaks are observed; the major peaks for individual gases are generally selected but some exceptions occur. Methane is detected at mass 15 (that is, the CH3+ fragment) to avoid interference by O- fragments from water (the methane peak at mass 15 is about 90% as intense as the peak at mass 16). CH3+ fragments generated by other organic compounds are typically much less abundant and can be corrected for. It is likely that the meteorites host multiple fluid inclusions and, as the sample is incrementally crushed, inclusions can rupture several milliseconds apart to produce a doublet in some mass scans, as seen in Fig. 1. Ratios of gases are reported, as the crushing does not liberate the total amount of entrapped gas. The instrument was calibrated using Scott Gas Mini-mix commercial standard gas mixtures, synthetic inclusions filled with gas mixtures and three in-house fluid inclusion gas standards49. The Mini-mix gas mixtures have a possible 2% error in the value of the secondary gas mixed with hydrogen. Data are reported on a water-free basis. Instrumental blanks are also analysed routinely. The amount of each species was calculated by matrix methods51,52 to provide a quantitative analysis, which is corrected for the instrumental background. Crushing does not liberate all the entrapped gas from samples, so data are generated as molar percentages rather than moles. To circumvent the dependence of individual percentages on irrelevant species, we report methane abundances as the ratio (mol% CH4)/(mol% CO2), hydrogen abundances as (mol% H2)/(mol% CO2) and oxygen abundances as (mol% O2)/(mol% CO2) (hereafter CH4/CO2, H2/CO2 and O2/CO2 respectively). Analyses were only treated as valid if they yielded an order of magnitude more total gas than (that is, at least 20 × ) the blanks. The mass spectrometer has a range of linearity up to 10e−6 amps. The bursts from the meteorites are too low to reach this part of the current range where non-linearity begins, so linearity is assured. Before analysis, the crushing area and the bellows of the crusher were cleaned using potassium hydroxide. The potassium hydroxide was then removed by swabbing with deionized water, followed by air drying. The apparatus is also routinely cleaned with isopropanol. Thereafter, the crushing chamber is baked at about 150–200 °Celsius for 72 h before loading and analysing the samples at room temperature the next day. The crushing area is isolated from the main chamber so that the main chamber can be baked out every evening. This way the samples are not heated overnight and lose gas, but they are exposed to high vacuum to remove adhered gases. Meteorite samples were transferred directly onto hard metal disks for crushing to avoid handling contamination.

Calibration using blank analysis

A standard NB84, consisting of calcite containing a 25.0% carbon dioxide-water mix, was analysed 52 times. The weighted mean content of carbon dioxide measured was 25.18 mol%, within <1% of the standard composition. This standard is used to calibrate water-gas ratios, but is not essential to measurement of the relative proportions of gases reported in this study. Three blank/reference sample measurements are considered in the measurement of gases. First, a blank is measured from moving parts (bellows in crushing mechanism), without crushing a sample. Second, a procedural blank is measured from crushing a Cenozoic olivine basalt (Beinn Totaig Group, Loch Beag, Island of Skye, Scotland; ref. 53), after heating for 4 h at 750 °C in a vacuum, to cause complete degassing. Third, a blank is measured from crushing synthetic quartz free of visible inclusions (so none larger than 1 μm, if any are present).

The compositions of the quartz blank and basalt blank (mean and standard deviation) are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Composition of quartz and basalt blanks.

| Gas | Qtz blank mean (mols) | Qtz blank s.d. (mols) | Basalt blank mean (mols) | Basalt blank s.d. (mols) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | 5.1E−15 | 1.31E−14 | 3.01E−15 | 4.09E−15 |

| He | Below detection | 0 | 2.12E−16 | 2.50E−16 |

| CH4 | 4.14E−14 | 2.08E−14 | 6.62E−16 | 1.42E−15 |

| N2 | 2.84E−15 | 3.2E−14 | 1.14E−12 | 6.81E−13 |

| O2 | 1.1E−15 | 4.7E−16 | 0 | 0 |

| Ar | 1E−16 | 1.6E−16 | 3.01E−16 | 5.37E−16 |

| CO2 | 4.5E−15 | 2.83E−15 | 5.50E−11 | 4.27E−11 |

The blank from the bellows is negligible compared with the blanks from crushing and is so small that we cannot quantify it. The meteorite yields are much greater than the basalt and quartz blanks, so we have confidence that the yields are predominantly gas from the meteorites rather than an artefact of crushing. The mean basalt blank gives yields 0.03 to 0.10% (mean 0.07%) of the meteorite yields of methane after blank correction (Table 2). The maximum basalt blank (uppermost value of the standard deviation) gives yields 0.68 to 2.30% of the meteorite yields. The procedural blank was deducted from measurements, excepting for carbon dioxide that was measured from the quartz blank, as the heating-degassing process generates new carbon dioxide.

Table 2. Blank methane value as percentages of meteorite methane values.

| Sample | Blank % of meteorite | Blank+s.d. % of meteorite |

|---|---|---|

| NWA5790 | 0.08 | 1.76 |

| Zagami | 0.04 | 0.90 |

| LA002 | 0.10 | 2.30 |

| Nakhla | 0.05 | 1.04 |

| Y000749 | 0.03 | 0.68 |

| MIL03346 | 0.10 | 2.26 |

The blanks quantify the maximum possible contribution of trace gas produced by the crushing process, which we attribute to the metal crushing discs. The blank current is about double that of the background current. The s.d. of the mass spectrometer's signal to noise ratio at the mass 15 background is 1.196e−13.

Detection limits

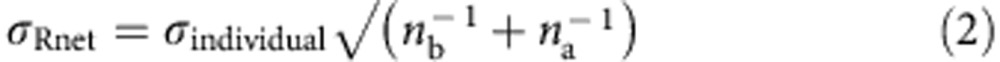

The detection limit measurements are as described in ref. 50. The formula is the same as used by ref. 54 and slightly modified by later workers55,56. The s.d. of an individual determination of the background of a sample is given by the formula:

|

where X is the mean, and Xi is one of the values contributing to the mean.

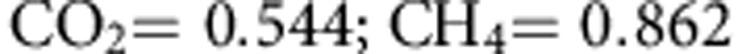

Previous workers50,54 recognized for a MS transient sampling signal that the measurement error included both elements of the background (nb is number of cycles obtained from the background) and the analyte (na is number of cycles used for the measurement of the analyte signal) where the error associated with the net (analyte minus background) signal (σRnet) equals the 1σ from the background times the square root of 1/nb plus 1/na as shown in the formula below. For σRnet, the s.d. of the mean net signal (gross—background), both nb and na are 10 thus improving the σRnet by 0.45 times the σindividual.

|

The term σRnet is the s.d. of the mean net signal and while it is common practice by geochemists to make 2σ as the confidence limits or approximately a 95% confidence limit, we adopt a 99% or ∼3σ value is used to confirm that the gas burst contains more than zero concentration. As the above s.d. is in terms of signal count rates or other convenient units, it is more useful to convert this value to concentration units by dividing by the sensitivity, S (signal per unit concentration):

|

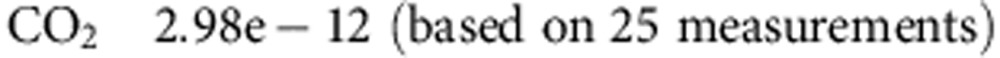

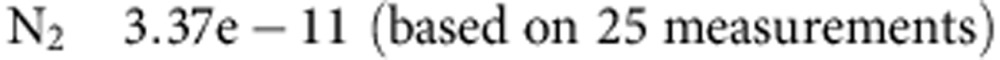

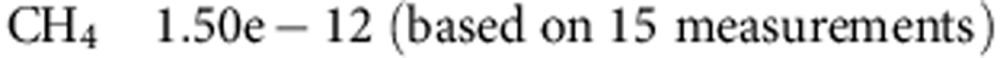

The sensitivity factors, relative to N2=1.0, determined at the time of analysis were:

|

For the mass spectrometer system in its current configuration the 2σ detection limit ranges from 0.8 to 1.2 femtomol (10−15 mol), depending on noise within the mass spectrometer.

Introduction to error calculations

Total errors are calculated from six components: blank compositions; uncertainty in gas composition; analytical errors in measuring current; interferences in measuring gas species; error in linear range; and background instrument noise. There is an additional, seventh, component, which only applies to the summary data table (Supplementary Table 2), where mols are reported, based on the conversion of the mass spectrometer current into mols.

Blank compositions

The s.d. (1 sigma) of blank compositions, as determined above, expressed as current (amps), are:

|

|

|

Uncertainty in gas composition

During calibration, Scott Gas standard gas mixtures are used for the gases H2, He, CH4 and CO2, for which the manufacturer specifies a 2% uncertainty. The gases N2, O2 and Ar are sourced from the atmosphere for which no uncertainty is assigned. Our measurements of the composition of CH4, CO2 and N2 have a s.d. of 0.061, 0.062 and 0.043% respectively, determined over 400 acquisitions.

Analytical errors

To quantify the error associated with the incremental crush method, we used atmosphere sealed in seven gas capillary tubes and analysed the N2/Ar ratios. The analytical mean ratio was 83.4 and s.d. 0.4; atmosphere is 83.6. The error therefore includes estimation of the area under the peak curve as well as signal noise within the mass spectrometer. Note that, although some analysts using LA-ICP-MS apply a Gaussian formula57, gas signals released from fluid inclusions are not Gaussian in shape (also recognized using LA-ICP-MS55,58,59) and our estimation of the area under the curve bears a close resemblance to that of ref. 55. Our 1σ precision is 0.5%.

Interferences in measuring gas species

Three interferences are potentially relevant. First, analysts may consider analysing for CH4 at m/e=16 (which is the major peak); however, this mass corresponds to a minor interference by a fragmented water ion. We used m/e=15 instead of 16 for methane as the m/e=15 peak (CH3+) is 90% of the m/e=16 peak and avoids interference corrections from water. The trade-off of 10% increased error at m/e=15 versus interference from water makes the m/e=15 much more attractive for methane analysis. Second, a very minor interference of 0.032% is detected at the m/e=32 (principle mass for oxygen) and is attributable to CO2. No adjustment is made for this very low value. The principle interference that occurs is that of CO2 fragmentation to produce CO+ and which corresponds to the N2 m/e=28 channel. Of the total CO2 signal, 8.2% is due to CO+ at m/e=28. However, typically the CO2 is half that of N2 for the meteorite samples and therefore the contribution of CO+ to the m/e=28 signal is only about 4%. The CO2 content at m/e=44 is used to remove 4% contribution to the N2 value. The relative error added to N2 includes a square function and therefore CO2 only contributes about 0.16% to the relative N2 error.

Error in linear range

The error across the linear range of the mass spectrometer is estimated from the s.d. for capillary tube measurements of the N2/Ar ratio. This covers the noise and the area under the peak curve. The measurements indicate a maximum error of 1%.

Background instrument noise

The background instrument noise is measured when no sample is being analysed. The signal is measured with the sample exposed to the main chamber and represents all residual gases that comprise the background with the turbo pump operating at maximum speed of 90,000 r.p.m. The mass spectrometer is instructed to begin recording and cycle through the selected masses relating to the gases being analysed. Approximately 30 s later the incremental crush occurs. The background is measured for 10 cycles stopping at 1 s before the gas burst. Both the background signal mean and s.d. are recorded.

Conversion of current to moles

Conversion from mass spectrometer current (amps) to gas concentration (mols) is achieved by analysing the contents of a Millipore one microliter volume capillary tube containing atmosphere at standard temperature and pressure, sealed using a high-vacuum epoxy glue. The tube is crushed in the same manner as any other sample. The number of moles of nitrogen (obtained using PV=nRT) is equated to the measured current. The equivalence determined at the time of measurement of the meteorites was 1,054 amps per mol, calculated by conventional matrix methods51,52. The uncertainty in measurement is no more than 5%, based on the s.d. of measurements of the ratio of current to moles calculated from the area under the peak curve. In addition, the manufacturer reports a maximum 1% uncertainty in the volume of the capillary tube. Adding these two errors give 5.04% (square root of added squares).

Propagation of errors

The uncertainty matrix includes multiple components as described above. There will be different contributions of uncertainties for each gas. The formula to incorporate the additive uncertainties is:

|

The components used in the additive error calculation are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Components used in additive error calculation.

| CO2 | N2 | CH4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank (current (amps), 1 sigma s.d.) | 2.98e−12 | 3.37e−11 | 1.50e−12 |

| Uncertainty in gas composition from standard | 2% | 0 | 2% |

| Interference | 0 | 4% of CO2 | 0 |

| Analytical error | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Error in linear range | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| Background instrument noise (1-sigma) | Specific to analysis | Specific to analysis | Specific to analysis |

| Conversion current to mols | 5.04% | 5.04% | 5.04% |

An example of the errors is given in Table 4. This is for a crush of the Zagami meteorite and is the smallest burst of gas measured in the programme.

Table 4. Errors calculated for smallest crush of the Zagami meteorite.

| Source of error/uncertainty | CO2 | N2 | CH4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background instrument noise (1-sigma) | 5.20e−13 | 1.47e−12 | 1.05e−13 |

| Blank (1-sigma) | 2.98e−12 | 3.37e−11 | 1.50e−12 |

| Uncertainty in gas composition from standard | 4.73e−13 | 0 | 1.19e−11 |

| Interference | 0 | 2.92e−13 | 0 |

| Analytical error (0.5%) | 1.18e−13 | 4.75e−13 | 2.98e−12 |

| Error in linear range (1%) | 2.36e−13 | 9.50e−13 | 5.96e−12 |

| Additive error before converting to mols | 3.07e−12 | 3.37e−11 | 1.37e−11 |

| Conversion current to mols for this crush | 3.13e−15 mols | 3.24e−14 mols | 3.14e−14 mols |

Additional information

How to cite this article: Blamey, N.J.F. et al. Evidence for methane in Martian meteorites. Nat. Commun. 6:7399 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8399 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

Meteorite samples were kindly provided by the University of New Mexico (Zagami), Caroline Smith, Natural History Museum, London (Nakhla), Robert Verish, Meteorite Recovery Laboratory, California (LA 002), Darryl Pitt, Macovich Collection, New York NWA 5790), Hideyasu Kojima, National Institute of Polar Research, Japan (Yamoto 000749) and the Meteorite Working Group, NASA Johnson Space Center (Miller 03346). D.M. is supported by the STFC (ST/H002472/1 & ST/K000918/1). S.McM. was supported by a STFC Aurora studentship.

Author contributions J.P., N.B. and D.M. conceived the project and prepared the manuscript. J.P., D.M., T.T., J.S. and M.I. undertook the sampling. N.B. performed the measurements. N.B. , J.P. and S. McM. analysed the data. M.L., N.B. and R.F. were joint supervisors. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

07/27/2015

This Article was originally published under NPG's License to Publish, which has now been changed to CC-BY 4.0. The PDF and HTML versions of the paper have been modified accordingly.

References

- Formisano V., Atreya S., Encrenaz T., Ignatiev N. & Giuranna M. Detection of methane in the atmosphere of Mars. Science 306, 1758–1761 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumma M. J. et al. Strong release of methane on Mars in northern summer 2003. Science 323, 1041–1045 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte M., Blake D., Hoehler T. & McCollum T. Serpentinization and its implications for life on the early Earth and Mars. Astrobiology 6, 364–376 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atreya S. K., Mahaffy P. R. & Wong A. S. Methane and related trace species on Mars: Origin, loss, implications for life, and habitability. Planet. Space Sci. 55, 358–369 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Blank J. G. et al. An alkaline spring system within the Del Puerto Ophiolite (California, USA): A Mars analog site. Planet. Space Sci. 57, 533–540 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- ten Kate I. L. Organics on Mars? Astrobiology 10, 589–603 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre F. & Forget F. Observed variations of methane on Mars unexplained by known atmospheric chemistry and physics. Nature 460, 720–723 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahnle K., Freedman R. S. & Catling D. C. Is there methane on Mars? Icarus 212, 493–503 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Webster C. R. et al. Mars methane detection and variability at Gale crater. Science 347, 415–417 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk M. R. & Giovannoni S. J. Sources of nutrients and energy for a deep biosphere on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. 104, E11805–E11815 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B. P., Yung Y. L. & Nealson K. H. Atmospheric energy for subsurface life on Mars? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 1395–1399 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski J. R. et al. Groundwater activity on Mars and implications for a deep biosphere. Nat. Geosci. 6, 133–138 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Etiope G., Ehlmann B. L. & Schoell M. Low temperature production and exhalation of methane from serpentinized rocks on Earth: a potential analog for methane production on Mars. Icarus 224, 276–285 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sleep N. H., Meibom A., Fridriksson T., Coleman R. G. & Bird D. K. H2-rich fluids from serpentinization: geochemical and biotic implications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 12818–12823 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassefière E. & Leblanc F. Methane release and the carbon cycle on Mars. Planet. Space Sci. 59, 207–217 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- McCollom T. M., Sherwood Lollar B., Lacrampe-Couloume G. & Seewald J. S. The influence of carbon source on abiotic organic synthesis and carbon isotope fractionation under hydrothermal conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 2717–2740 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Lever M. A. et al. Evidence for microbial carbon and sulfur cycling in deeply buried ridge flank basalt. Science 339, 1305–1308 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSween H. Y. Jr., Taylor G. J. & Wyatt M. B. Elemental composition of the martian crust. Science 324, 736–739 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton V. E. & Christensen P. R. Evidence for extensive, olivine-rich bedrock on Mars. Geology 33, 433–436 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew L. E., Ellison E. T., McCollom T. M., Trainor T. P. & Templeton A. S. Hydrogen generation from low-temperature water-rock reactions. Nat. Geosci. 6, 478–484 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ménez B., Pasini V. & Brunelli D. Life in the hydrated suboceanic mantle. Nat. Geosci. 5, 133–137 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Mustard J. F. et al. Hydrated silicate minerals on Mars observed by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter CRISM instrument. Nature 454, 305–309 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T. et al. Laihunite and jarosite in the Yamato 00 nakhlites: alteration products on Mars? J. Geophys. Res. 114, E10004 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Ehlmann B. L., Mustard J. F. & Murchie S. L. Geologic setting of serpentine deposits on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L06201 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Wray J. J. & Ehlmann B. L. Geology of possible Martian methane source regions. Planet Space Sci. 59, 196–202 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Grady M. M., Verchovsky A. B. & Wright I. P. Magmatic carbon in Martian meteorites: attempts to constrain the carbon cycle on Mars. Int. J. Astrobiol. 3, 117–124 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffy P. R. et al. Abundance and isotopic composition of gases in the Martian atmosphere from the Curiosity rover. Science 341, 263–266 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooding J. L., Aggrey K. E. & Muenow D. W. Volatile compounds in shergottite and nakhlite meteorites. Meteoritics 25, 281–289 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Bridges J. C., Smith M. P. & Grady M. M. Progressive evaporation and relict fluid inclusions in the nakhlites. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. XXXI, 1590 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Mathew K. J. & Marti K. Martian atmospheric and interior volatiles in the meteorite Nakhla. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 199, 7–20 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright J. A., Gilmour J. D. & Burgess R. Martian fluid and Martian weathering signatures identified in Nakhla, NWA 998 and MIL 03346 by halogen and noble gas analysis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 105, 255–293 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Jambon A. et al. The basaltic shergottite Northwest Africa 856: Petrology and chemistry. Meteor. Planet. Sci. 37, 1147–1164 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Shih C.-Y., Nyquist L. E. & Jambon A. Sm-Nd isotopic studies of two nakhlites, NWA 5790 and Nakhla. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. XLI, 1367 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Hallis L. J. & Taylor G. J. Comparisons of the four Miller Range nakhlites, MIL 03346, 090030, 090032 and 090136: Textural and compositional observations of primary and secondary mineral assemblages. Meteor. Planet. Sci. 46, 1787–1803 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tomkinson T., Lee M. R., Mark D. F., Dobson K. J. & Franchi I. A. The Northwest Africa (NWA) 5790 meteorite: a mesostasis-rich nakhlite with little or no Martian aqueous alteration. Meteor. Planet. Sci. 50, 287–304 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Parnell J., Mark D. & Brandstatter F. Response of sandstone to atmospheric heating during the STONE-5 experiment: Implications for the palaeofluid record in meteorites. Icarus 197, 282–290 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Blamey N. J. F. Composition and evolution of crustal fluids interpreted using quantitative fluid inclusion gas analysis. J. Geochem. Explor. 116-117, 17–27 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wright I. P., Grady M. M. & Pillinger C. T. Chassigny and the nakhlites: Carbon-bearing components and their relationship to Martian environmental conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 817–826 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Parnell J., Boyce A. J. & Blamey N. J. F. Follow the methane: the search for a deep biosphere, and the case for sampling serpentinites, on Mars. Int. J. Astrobiol. 9, 193–200 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Tomkinson T., Lee M. R., Mark D. F. & Smith C. L. Sequestration of Martian CO2 by mineral carbonation. Nat. Commun. 4, 2662 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalski J. R. & Niles P. B. Deep crustal carbonate rocks exposed by meteor impact on Mars. Nat. Geosci. 3, 751–755 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Andrawes F. F. & Gibson E. K. Release and analysis of gases from geological samples. Am. Mineral 64, 453–463 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer B., Fischer G., Neftel A. & Oeschger H. Increase of atmospheric methane recorded in Antarctic ice core. Science 229, 1386–1388 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki S., Oya Y. & Makide Y. Emission of methane from stainless steel investigated by using tritium as a radioactive tracer. Chem. Lett. 35, 292–293 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- McMahon S., Parnell J. & Blamey N. J. F. Sampling methane in basalt on Earth and Mars. Int. J. Astrobiol. 12, 113–122 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Zolensky M. E., Krot A. N. & Benedix G. Record of low-temperature alteration in asteroids. Revs. Mineral 68, 429–462 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Busemann H. & Eugster O. The trapped heavy noble gases in recently found Martian meteorites. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. XXXIII, 1823 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Schrenk M. O., Brazelton W. J. & Lang S. Q. Serpentinization, carbon, and deep life. Revs. Mineral 75, 575–606 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Norman D. I. & Blamey N. J. F. Quantitative analysis of fluid inclusion volatiles by a two quadrupole mass spectrometer system. ECROFI XVI, 341–344 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Blamey N. J. F., Parnell J. & Longerich H. P. Understanding detection limits in fluid inclusion analysis using an incremental crush fast scan method for planetary science. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. XLIII, 1035 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Isenhour T. L. & Jurs P. C. Introduction to computer programming for chemists 325Allyn & Baco (1972). [Google Scholar]

- Norman D. I. & Sawkins F. J. Analysis of volatiles in fluid inclusions by mass spectrometry. Chem. Geol. 61, 1–10 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. N., Gibson I. L., Marriner G. F., Mattey D. P. & Morrison M. A. Trace-element evidence of multistage mantle fusion and polybaric fractional crystallization in the Palaeocene lavas of Skye, NW Scotland. J. Petrol. 21, 265–293 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Longerich H. P., Jackson S. E. & Günther D. Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric transient signal data acquisition and analyte concentration calculation. J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 11, 899–904 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Tanner M. & Günther D. In torch laser ablation sampling for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. J . Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 20, 987–989 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Borovinskaya O., Gschwind S., Hattendorf B., Tanner M. & Günther D. Simultaneous mass quantification of nanoparticles of different composition in a mixture by microdroplet generator-ICPTOFMS. Anal. Chem. 86, 8142–8148 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwind S., Hattendorf B., Frick D. A. & Günther D. Mass quantification of nanoparticles by single droplet calibration using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 85, 5875–5883 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottle J. M., Horstwood M. S. A. & Parrish R. R. A new approach to single shot laser ablation analysis and its application to in situ Pb/U geochronology. J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 24, 1355–1363 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Pettke T. et al. Recent developments in element concentration and isotope ratio analysis of individual fluid inclusions by laser ablation single and multiple collector ICP-MS. Ore Geol. Revs. 44, 10–38 (2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Tables 1-2, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary References