Abstract

Background

Alcohol exposure has adverse effects on stress physiology and behavioral reactivity. This is suggested to be due, in part, to the effect of alcohol on β-endorphin (β-EP) producing neurons in the hypothalamus. In response to stress, β-EP normally provides negative feedback to the HPA axis and interacts with other neurotransmitter systems in the amygdala to regulate behavior. We examined whether β-EP neuronal function in the hypothalamus reduces the corticosterone response to acute stress, attenuates anxiety-like behaviors, and modulates alcohol drinking in rats.

Methods

To determine if β-EP neuronal transplants modulate the stress response, anxiety behavior and alcohol drinking, we implanted differentiated β-EP neurons into the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) of normal, prenatal alcohol exposed, and alcohol-preferring (P) and non-preferring (NP) rats. We then assessed corticosterone levels in response to acute restraint stress and other markers of stress response in the brain, and anxiety-like behaviors in the elevated plus maze and open-field assays.

Results

We showed that β-EP neuronal transplants into the PVN reduced the peripheral corticosterone response to acute stress and attenuated anxiety-like behaviors. Similar transplants completely reduced the hyper-corticosterone response and elevated anxiety behaviors in prenatal alcohol exposed adult rats. Moreover, we showed that β-EP reduced anxiety behavior in P rats with minimal effects on alcohol drinking during and following restraint stress.

Conclusions

These data further establish a role of β-EP neurons in the hypothalamus for regulating physiological stress response and anxiety behavior, and resembles a potential novel therapy for treating stress-related psychiatric disorders in prenatal alcohol exposed children and those genetically predisposed to increased alcohol consumption.

INTRODUCTION

In the U.S. alone, direct and indirect health costs related to alcohol abuse and alcoholism disorders are steadily rising. The impact of alcohol use reaches beyond the individual drinker. In particular, as alcohol use during pregnancy has severe health consequences that persist throughout childhood and into adulthood (May et al., 2009). The adverse effects of fetal alcohol exposure on stress physiology and behavioral reactivity may be primarily due to vulnerability of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis to developmental perturbation. In the CNS, β-endorphin (β-EP) contributes to the positive reinforcement and motivational properties of drugs of abuse. Indeed, β-EP is intimately involved in the development of alcohol abuse and dependence (Mendez and Morales-Mulia, 2008; Roth-Deri et al., 2008). In the current study, we explored whether β-EP producing neurons alleviated the elevated corticosterone response to restraint stress that is often observed in animal models of fetal alcohol exposure. Several studies in human and non-human primate subjects have demonstrated a positive correlation between higher levels of alcohol exposure in utero to elevated heart rate, higher cortisol reactivity, and negative affect (Taylor et al., 1988; Schneider et al., 2011; Ouellet-Morin et al., 2011). Other studies have extended these findings by demonstrating that fetal alcohol exposed children are at an increased risk for psychiatric diseases, including psychotic disorders, addiction, depression and anxiety (Famy et al., 1998; Molteno et al., 2014).

A common endophenotype of fetal alcohol exposed offspring is an elevated neuroendocrine response of the HPA axis, particularly circulating corticosterone, which has been suggested to be due, at least in part, to the deleterious effects of alcohol exposure on hypothalamic β-EP producing neurons (Hellemans et al., 2008; Wynne and Sarkar, 2013). During the stress response, hypothalamic peptides are released through several signaling cascades, such as the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) followed by the release of proopiomelanocortin (POMC). POMC is a relatively large peptide that is cleaved into multiple biologically active subunits, including β-EP, which provides negative feedback to the HPA axis by inhibiting further CRH release. Upon stimulation, β-EP synthesis, primarily within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, is activated by CRH release from terminals emerging from the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, which is in turn inhibited by β-EP release (Plotsky et al., 1991; Wynne and Sarkar, 2013). In addition, endogenous opioid systems interact extensively with serotonergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission in brain areas known to be associated with anxiety, such as the amygdala, which suggests other mechanisms of β-EP to modulate behavior (Zarrindast et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 1996). Previous studies indicate that β-EP modulation of the HPA axis influences the behavioral response to stress and low β-EP is associated with increased anxiety-like behavior (Barfield et al., 2010; Grisel et al., 2008;). In the current study, we investigated whether β-EP neuronal transplantation could attenuate the elevated anxiety-like behavior and the corticosterone response to acute restraint stress in fetal alcohol exposed rats. Previously, we have shown that β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN of the hypothalamus reduces the response of hypothalamic CRH neurons to an immune stressor and modulates the peripheral stress response during and following a stressor (Boyadjieva et al., 2009; Sarkar and Zhang, 2013).

Although some studies have demonstrated an association between an increased physiological stress response and increased alcohol consumption, studies from both animals and humans suggest this relationship is complex (Brady and Sonne, 1999; Spanagel et al., 2014). Certain stressors have been shown to increase alcohol self-administration (Eckardt et al., 1998; Wolffgramm, 1990) and inhibition of the stress axis via CRH antagonism has been shown to reduce alcohol intake under some conditions (Funk et al., 2007; Le et al., 2000). Previous studies suggest acute and chronic stress, such as single or repeated exposure to physical restraint and/or foot-shock, alters alcohol intake during continuous and limited access conditions in selectively-bred alcohol preferring (P) and non-preferring (NP) rats (Bertholomey et al., 2011; Chester et al., 2004). Indeed, P rats display enhanced stress-induced alcohol drinking compared to NP rats (Chester et al., 2004), as well as differences between selectively-bred lines in stress-related neuropeptides and HPA-axis regulation (Ehlers et al., 1992; Hwang et al., 2004; Yong et al., 2014). Therefore, we investigated whether β-EP neurons transplanted into the hypothalamic PVN would alter alcohol drinking under continuous and limited access conditions before, during, and following restraint stress in P and NP rats. We extended our hypotheses to determine whether β-EP neurons had any effects on anxiety-like behaviors considering several previous studies reporting P rats exhibited increased anxiety-like behavior than NP rats (Pandey et al., 2005; Stewart et al., 1993), potentially due to differences in stress neurobiology (Yong et al., 2014).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Sprague Dawley male rats and Fischer (344) male and female rats were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Male and female NP and P rats were obtained from the Indiana University Alcohol Research Center (Indianapolis, IN). All animals were housed in a climate controlled environment with a standard 12:12 light-dark cycle (7:00 and 19:00 h, on and off, respectively). All experimental animals were individually housed for at least three weeks prior to behavioral testing. Animal care and treatment were performed in accordance with the Rutgers Animal Care and Facilities Committee and complied with policies of the National Institutes of Health.

Experimental Design

Experiments were conducted using male rats for the following experiments: 1) Separate cohorts of male Sprague Dawley rats underwent behavioral testing following neuronal transplantation or following acute injections with anxiogenic or anxiolytic pharmacological compounds (n=20/group). After 2–3 weeks post-behavioral testing, male rats were exposed to acute restraint stress (n=10/), during which tail blood was collected to assess peripheral corticosterone levels; 2) Male Fischer rats that were exposed to control or alcohol treatments (n=8/group) during gestation were transplanted with differentiated neurons at 3–4 weeks of age and underwent behavioral testing between 3–5 months of age. After 2–3 weeks post-behavioral testing, male rats were exposed to restraint stress (n=4/group) to assess peripheral corticosterone levels. At approximately 3–4 weeks following the acute stress test, these rats were sacrificed and their brains were removed for gene expression analyses (n=4/group); and 3) Male and female NP and P rats (n=8–10/group) underwent neuronal transplantation shortly after delivery and allowed to recover and acclimate for approximately two months prior to behavioral testing. Anxiety-like behavioral testing was completed prior (~4–6 weeks) to the alcohol drinking experiments.

Animal breeding and prenatal alcohol treatment

Following an acclimation period of 7–10 days, male and female rats were breed. Between days 7–21 of gestation, pregnant dams had ad libitum (AD) access to rodent chow, or fed an ethanol-containing liquid diet (AF) (Bioserv, Frenchtown, NJ), or an isocaloric liquid diet (PF). Both PF and AF diets were refilled about 1 h before lights off each day. Pregnant dams were acclimated to the ethanol containing liquid diet in a stepwise fashion—days 7–8, 2.2% ethanol followed by 4.4% on days 9–10, and finally 6.7% on days 11 to 21. Previous studies have shown that the peak blood ethanol concentration is achieved in the range of 120–150 mg/dl in pregnant dams fed with this liquid diet (Miller, 1992). On day 2 after birth, pups from both PF and AF mothers were cross-fostered to AD females until day 22 post-partum and then weaned and housed in pairs until neuronal transplantation surgery, behavioral testing and other assays.

Preparation of β-EP cells from neural stem cells

We developed and described in detail isolation and characterization of β-EP-producing cells derived from neural stem cells (NSCs) (Sarkar et al., 2008). Briefly, NSCs were isolated from mediobasal hypothalamic tissue of 17-day old fetal Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River). Hypothalamic neural cells were enriched and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium with HEPES (HDMEM with10% FBS) for approximately 3 weeks. At the 3rd week, neurospheres were dissociated into single cells and maintained in culture for several months. In order to promote β-EP cell differentiation, cells were treated for 1 week with 10 μM pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) and 10 μM dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate (dbcAMP).

Animal surgery and neural transplantation

These procedures have been described previously (Boyadjieva et al., 2009). Briefly, in vitro differentiated β-EP cells were dissociated, washed, and resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 104 cell/μl for transplantation. Control cortical cells (CC) were prepared and resuspended similarly. Cell viability, assessed with Trypan blue exclusion assay, was routinely > 90% for in vitro preparations. Rats between 40–90 days of age were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50–70 mg/kg, i.p.; Henry Schein, Indianapolis, IN), then bilaterally injected with 1 μl of neural stem cells in suspension into the PVN (A/P: −1.8 mm; M/L: +/− 0.5 mm; D/V: −7.5 mm). Following each injection, the syringe remained in place for ~20 mins, which was then slowly removed over ~10 min. The dura was closed with 9-0 sutures, the muscle was reapposed, and the skin was closed using metal wound clips. Penicillin was administered post-surgery and rats were placed on a heating pad during recovery. No immune suppression was used. At the end of experimentation, animals were sacrificed and brains were collected for verification of the site of cell transplants and the viability of transplanted β-EP cells by immunocytochemical procedures. Because the NSC lacks MHC-I protein (Mammolenti et al, 2004), the in vitro differentiated β-EP cells are not expected to get rejected in non-isogenic Fiscer 344 rat strain of host animals.

Behavioral testing in elevated plus maze (EPM)

Anxiety behavior was measured using the EPM apparatus constructed from black acrylic pieces sitting 60 cm above the floor. The EPM consisted of four arms (50 cm L × 10 cm W), two arms closed by non-transparent walls (~40 cm high) and two open arms without walls that were joined by a central square (10 cm × 10 cm). Behavioral testing was conducted between 1400 and 1700 h (during the later portion of the light phase of the light-dark cycle) in a sound attenuated dimly lit room (75 lux open arm; 12 lux closed arm). Rats were transported to the behavioral testing room under cover 1 h prior to testing to allow acclimation to the testing environment. An individual rat was placed in the center of the EPM facing an open arm and allowed to freely explore for 5 min, during which the experimenter monitored the rat on a computer behind a large non-transparent wall. Entry was defined as all four paws within an arm. Videos recorded by an overhead high resolution camera were scored for behaviors including, proportion of entries into the open arm (number of open entries to total entries × 100), proportion of time spent on open arm (time spent on open arm to total time × 100), and number of closed entries which are considered to be a reliable indicator of locomotor activity (Cruz et al., 1994). Other ethologically relevant behaviors were recorded as noted, including rears, head-dips, and stretched-attends (Walf and Frye, 2007), and duration of autogrooming (Kalueff and Tuohimaa, 2005).

Pharmacological validation of EPM

In order to validate EPM testing parameters, male Fischer rats were injected IP with either diazepam (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 2 g/kg; DZP), a known anxiolytic (Bert et al., 2001), or yohimbine (Sigma, 1.5 g/kg; YOH), an anxiogenic substance (Johnston and File, 1989), dissolved in distilled water with a few drops of Tween 20. DZP is a benzodiazepine having agonistic effects on GABA receptors, whereas YOH is an α2 adrenoreceptor antagonist. Rats were injected 30 min prior to EPM testing.

Behavioral testing in the open-field arena (OF)

Anxiety behavior was also measured in the OF arena, which is constructed from non-transparent black acrylic open-topped box measuring 90cm (L) × 90cm (W) × 40cm (H). The behavioral testing was conduced under modified fluorescent lighting (~25 lux at floor level) between 1400 and 1700h (during the later portion of the light-dark cycle). Rats were transported to the room under cover 1h prior to testing to allow acclimation to the testing environment. Videos recorded by an overhead high resolution camera were scored for behaviors including time spent in the center of the arena, center time (20cm × 20cm square), line crosses in the center, total line crosses, number of rears and stretch-attends, and time spent grooming.

Restraint stress, tail-blood collection, and corticosterone response plasma measurements

To assess basal corticosterone levels, blood was collected immediately prior to restraint from the tail. Rats were then restrained in Plexiglas tubes (Plas Labs, Inc, Lansing, MI) for 1 h (1200 to 1300h), during which tail blood was collected at 15 min intervals. Following restraint, tail blood was collected at 30 min intervals. All blood samples were collected in EDTA (Sigma) and kept on ice until centrifugation (at 4° and 3000 rpm) for plasma extraction. Plasma samples were analyzed for corticosterone levels by a competitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to manufacturer’s recommendations (ELISA, IBL, USA). All groups were analyzed on each 96-well plate to minimize between plate variability.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Rats were sacrificed, decapitated, and brains were collected then snap frozen using liquid nitrogen between 1000 to 1300h. Freshly frozen rat brains were sliced using a brain block (1 mm) to punch the following regions—PVN and the amygdala (AMY). Total RNA was isolated from brain tissue using RNeasy Mini Kit following manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). Using Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis Super Mix (Invitrogen), 250 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed for mRNA quantification by real-time qRT-PCR (ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector), using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) for the following genes, Crh (Rn01462137_m1), Crhr1 (Rn00578611_m1), and Npy (Rn01410145_m1). Analyses were performed using the relative standard curve method with GAPDH (Rn01775763_g1) as the endogenous control.

Alcohol drinking

After transplantation (~2 months), NP and P male rats (n = 8–10/group) were given two-bottle free choice (10% ethanol and tap water) for 14 days to establish baseline alcohol intake. Following baseline, rats were given limited access for five days, which consisted of access to 10% ethanol drinking solution for the first 3 h of the dark cycle. A separate cohort of rats was maintained on continuous 24 h access for five days. Both cohorts were subject to 60 min of restraint stress during the five days of the limited or continuous access paradigms. Alcohol drinking preferences during limited or continuous paradigms were averaged across each of the five days of access. The post-restraint phase also lasted for five days, also during which ethanol and water intakes were recorded. Ethanol intake was measured daily (mLs consumed).

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen brains were sectioned from bregma −1.3 to −1.8 mm with a slice thickness of 20 μM using a Cryostat (Leica CM1900, Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL)fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with rabbit anti-rat β-EP antibody (Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA, 1:200). The secondary antibody used was Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (Invitrogen, 4 μg/ml).

Statistical Analyses

Comparisons between groups were made using one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls or Bonferronic corrected multiple comparison post-hoc tests, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni, Tukey’s, or Newman-Keuls post-hoc tests (as noted) to correct for multiple comparisons, or Student t-test where appropriate. Significance was set at α=0.05. Refer to Table 1 for summary of statistical results.

Table 1.

| Experiment | Statistics | Post hoc tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-EP transplantation reduced corticosterone levels during restraint Fig. 1 | Main effects of group, F(1, 120) = 63.06, p < 0.0001, and time, F(6, 120) = 23.20, p < 0.0001, and group × time interaction F(6, 120), p = 0.0018# | 30 minutes, p < 0.0001; 60 minutes, p < 0.05; 90 minutes, p < 0.0001; and 120 minutes, p < 0.05* | |||

| β-EP transplantation reduced anxiety-like behaviors in the EPM Fig. 2 | Open arm time | F(2, 44) = 27.68, p < 0.0001a | CC versus DZP+, p < 0.0001* | ||

| Open arm entries | F(2, 44) = 25.33, p < 0.0001a | CC versus DZP+, p < 0.0001; CC versus β-EP, p < 0.0001* | |||

| Head dips | F(2,44) = 10.25, p < 0.001a | CC versus DZP+, p < 0.001; CC versus β-EP, p < 0.01* | |||

| Stretch attends | F(2,44) = 6.07, p = 0.0049a | CC versus DZP+, p < 0.01; CC versus β-EP, p < 0.05* | |||

| β-EP transplantation reduced anxiety-like behaviors in the OF Fig. 3 | Center time | p < 0.05b | N/A | ||

| Center activity | p < 0.05b | ||||

| Stretch attends | p < 0.05b | ||||

| Grooming | p < 0.001b | ||||

| β-EP transplantation attenuated the hyper-corticosterone response to acute restraint stress Fig. 4 | Basal levels | Main effects of treatment F(2, 18) = 11.81, p = 0.0006, and group F(1, 18) = 9.574, p = 0.0066, and no interaction# | CCAD or CCPFversus CCAF, p < 0.01, and CC AF versus β-EP AF, p < 0.01* | ||

| Restraint stress | Main effects of group, F(2, 58) = 64.24, p < 0.0001, and time, F(6, 58) = 31.99, p < 0.0001, and an interaction F(12, 58) = 9.3, p < 0.0001; aF(5, 18) = 31.10, p < 0.0001# | CC AD versus β-EP AD at 30 minutes, p < 0.01, and 60 minutes, p < 0.05, and CC PF versus β-EP PF, p < 0.01, CC AF, versus β-EP AF; CC ADversus CC PF, p < 0.05, CC AF versus CC AD or PF, p < 0.001, CC PF versus β-EP PF, p < 0.05, CC AF versus β-EP AF, p < 0.001* | |||

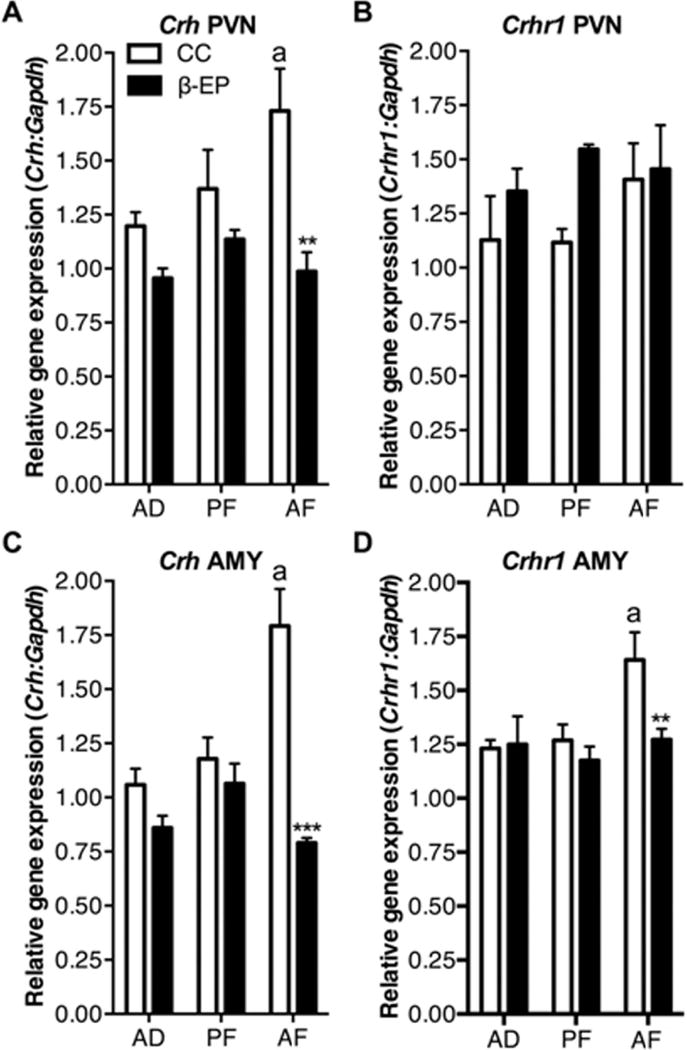

| β-EP transplantation reduced CRH and CRHR1 gene expression in the PVN and AMY in prenatal alcohol exposed male rats Fig. 5 | Crh | PVN | Main effects of treatment, F(1, 18) = 17.03, p = 0.0006, and group, F(2, 18) = 3.794, p < 0.05# | CC AD versus CC AF, p < 0.05, and CC AF versus β-EP AF, p < 0.01c | |

| AMY | Main effects of treatment, F(1, 18) = 30.66, p < 0.001, and group, F(2, 18) = 5.889, p < 0.05, and an interaction, F(2, 18) = 12.76, p < 0.001# | CC AD versus CC AF, p < 0.05, and CC AF versus β-EP AF, p < 0.001c | |||

| Crhr1 | AMY | Main effects of treatment, F(1, 18) = 4.12, p < 0.05, and group, F(2, 18) = 4.375, p < 0.05, but no interaction, F(2, 18) = 2.56, p = 0.10# | CC AD vs. CC AF, p < 0.05, and CC AF vs. β-EP AF, p < 0.01c | ||

| β-EP transplantation reduced anxiety-like behavior of prenatal alcohol exposed male rats inthe EPM Fig. 6 | Open arm time | Main effect of group, F(2, 42) = 14.84, p < 0.0001, without an overall effect of treatment, and a significant interaction, F(2, 42) = 4.881, p < 0.01# | β-EP AF versus CC AF, p < 0.001c | ||

| Open arm entries | Main effect of treatment, F(1, 42) = 6.948, p < 0.012# | CC PF versus CC AF, p < 0.05, and CC AF versus β-EP AF, p < 0.05c | |||

| Head dips | Main effect of treatment, F(2, 42) = 1.92, p = 0.05, and a significant interaction, F(2, 42) = 5.16, p < 0.001# | CC AF versus β-EP AF, p < 0.05c | |||

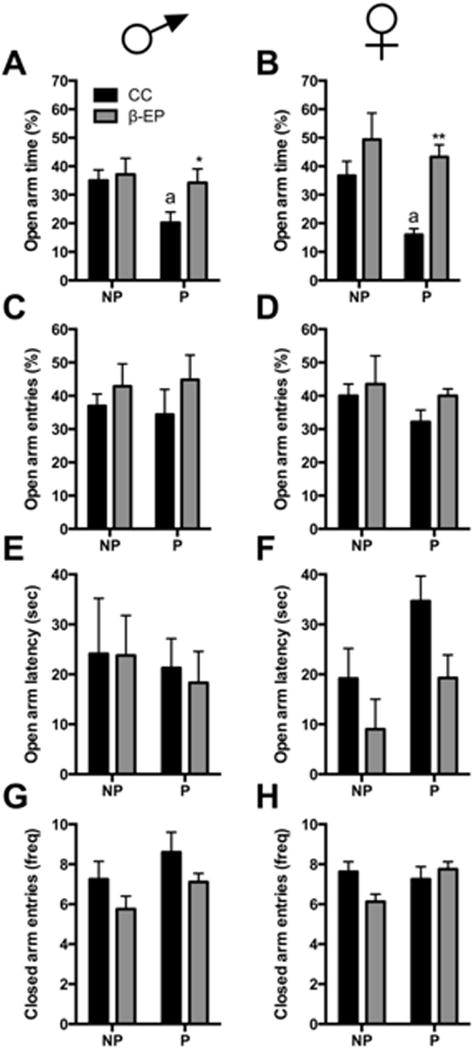

| β-EP transplantation altered anxiety-like behavior in the EPM of NP and P rats Fig. 7 | Open arm time | Males | Main effect of treatment F(1, 31) = 4.218# | CC P versus β-EP P, p < 0.05, and CC NP and CC P, p < 0.05d | |

| Females | Main effects of group, F(1, 28) = 6.663, p < 0.01, and treatment, F(1, 28) = 14.65, p < 0.001# | CC P versus β-EP P, p < 0.05, and CC NP and CC P, p < 0.05d | |||

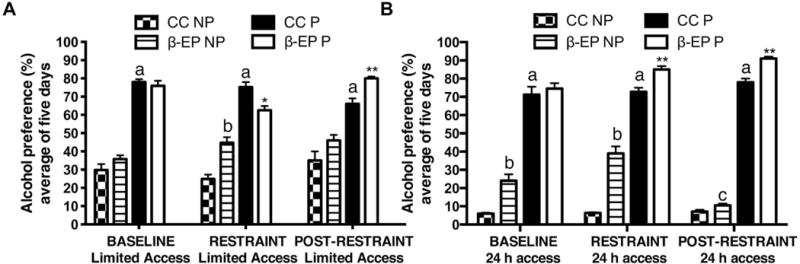

| β-EP transplantation altered ethanol intake during limited and continuous access following restraint stress in NP and P male rats Fig. 8 | Limited access | Main effects of experimental treatment, F(2, 138) = 3.72, p = 0.05, and group, F(3, 138) = 158.7, p < 0.0001, and an interaction, F(6, 138) = 5.727, p < 0.0001# | CC P versus β-EP P during restraint under limited access, p < 0.05; CC NP versus β-EP NP, p < 0.05c | ||

| Continuous access | Main effects of experimental treatment, F(2, 138) = 8.098, p < 0.001, and group, F(3, 138) = 711.9, p < 0.0001, and an interaction, F(6, 138) = 13.37, p < 0.0001# | CC P versus β-EP P during restraint under limited access, p < 0.05; CC NP versus β-EP NP prior toand during restraint, p < 0.05; CC β-EP restraint versus post-restraint, p < 0.05c | |||

Two-way ANOVA

Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons tests

One-way ANOVA

Student t test

Tukey’s posthoc tests

Newman-Keul’s post hoc tests.

RESULTS

β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN reduced corticosterone levels in response to restraint stress in male rats

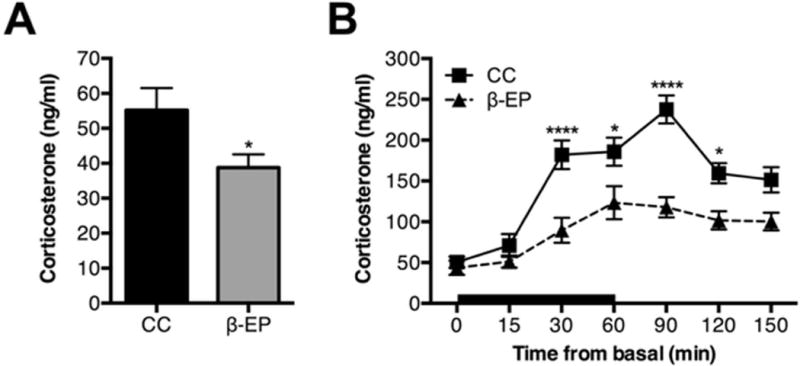

β-EP neurons were transplanted into the PVN of naïve male Sprague Dawley rats to determine whether β-EP neuronal transplantation would suppress the peripheral levels of corticosterone in response to an acute physical stressor. At baseline, β-EP transplanted rats displayed reduced peripheral blood levels of corticosterone (Fig. 1A). As expected, transplantation of β-EP cells, but not cortical cells (CC), into the PVN reduced peripheral blood levels of corticosterone in response to 60 min of restraint stress, which persisted following restraint (Fig. 1B), suggesting β-EP neuronal transplantation regulates HPA axis stress response through negative feedback of endogenous opioid peptides.

Figure 1.

β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN reduced corticosterone levels during baseline and in response to acute stress in male Sprague Dawley rats. β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN reduced basal circulating peripheral blood levels of corticosterone (A). β-EP neuronal transplantation also reduced the normal corticosterone stress response during and following restraint (B). Data shown in A are analyzed by Student t-test(CC vs. β-EP p < 0.05). Data of B are analyzed by Two-way repeated measures ANOVA [Main effects of group, F(1, 120) = 63.06, p < 0.0001, and time, F(6, 120) = 23.20, p < 0.0001, and group × time interaction F(6, 120), p = 0.0018]., followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests (CC vs. β-EP *, p < 0.05; ****, p < 0.0001).

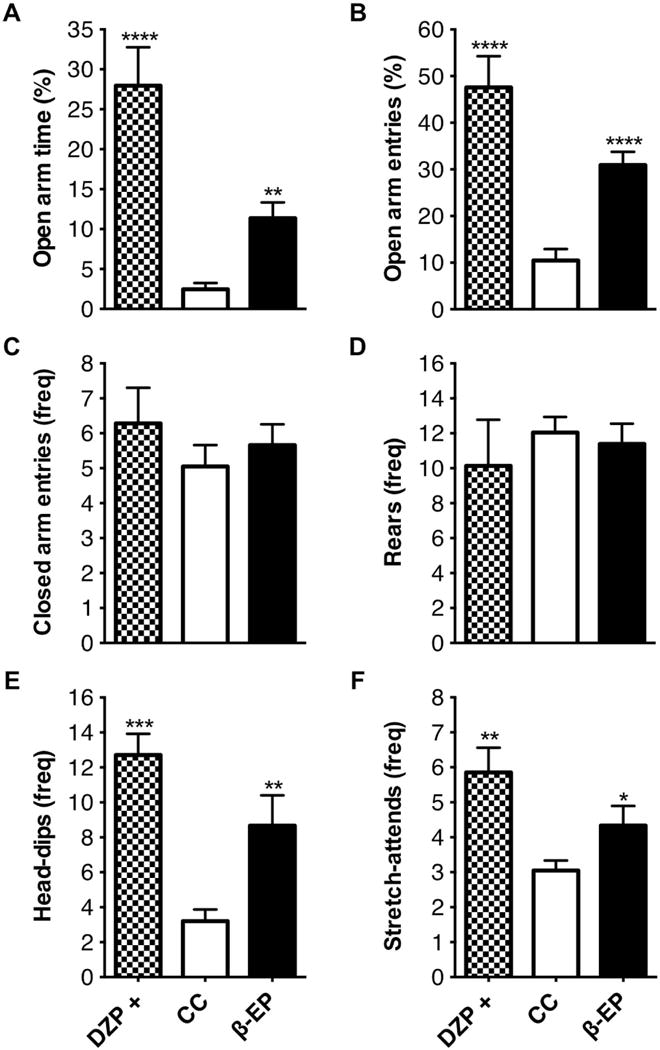

β-EP Neuronal transplantation into the PVN reduced anxiety-like behaviors in male rats

A separate cohorts of animals were administered a low dose of diazepam (positive control, DZP+, 2 g/kg), 30 min prior to behavioral testing to validate the conditions of the behavioral testing suite and also to compare the magnitude of the behavioral effects of β-EP transplantation on anxiety-like behaviors. As anticipated, DZP+ reduced anxiety-like behaviors, as evident by an increase in open arm time (Fig. 2A), in the absence of non-specific effects on exploratory activity relative to the rest (Fig. 2C). Head-dips (Fig. 2E), and stretch-attends (Fig. 2F), were also increased by acute DZP treatment.

Figure 2.

The effects of β-EP neuronal transplantation on anxiety-like behaviors of male Sprague Dawley rats in the elevated plus maze. β-EP transplantation into the PVN reduced anxiety-like behaviors in the elevated plus maze (A–F). β-EP transplantation increased the amount of time spent in the open arms (A) and the number of entries into the open arms (B), and increased the number of the head-dips and stretch-attends on the open arms (E,F). β-EP transplantation had no effect on general locomotor activity (number of closed arm entries) (C) and rearing behavior (D). Yohimbine (anxiogenic stimulus) and diazepam (anxiolytic compound) were used to verify testing procedures. One-way ANOVA. [open arm time F(2, 44) = 27.68, p < 0.0001; open arm entries, F(2, 44) = 25.33, p < 0.000; head dips, F(2,44) = 10.25, p < 0.001; stretch attends, F(2,44) = 6.07, p = 0.0049] with Bonferroni corrected post hoc tests (CC vs. β-EP, or DZP+ vs. YOH -, * p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; DZP+ vs. CC, a, p < 0.01).

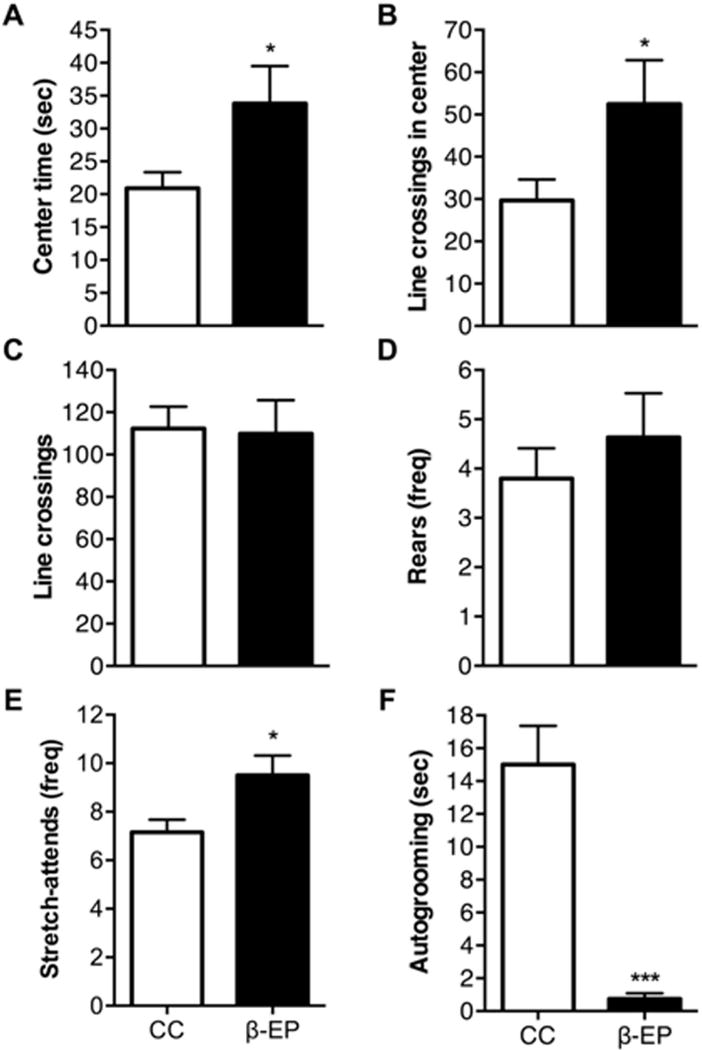

In addition, β-EP transplantation reduced anxiety-like behaviors in the elevated plus maze and further investigation indicated similar behavioral effects in the open-field area (Fig. 2 and 3). β-EP transplantation into the PVN increased the amount of time spent in the open arms (Fig. 2A), the number of entries into the open arms (Fig. 2B), and the number of head-dips (Fig. 2E) and stretch-attends (Fig. 2F), onto the open-arms relative to the CC control group. β-EP transplantation also increased the amount of time spent in the center of the open-field arena (Fig. 3A), exploratory activity in the center (Fig. 3B), and the number of stretch-attends (Fig. 3E), without affecting exploratory activity (Fig. 3C), or rearing behavior (Fig. 3D). Moreover, β-EP transplantation reduced the amount of time spent grooming in the open-field (Fig. 3F), an indicator of anxiety, or stress-induced behaviors. Together, these results indicate β-EP transplantation into the PVN is effective, similar to DZP+, in reducing anxiety-like behaviors in response to novel environments in male Sprague Dawley rats.

Figure 3.

The effects of β-EP neuronal transplantation on anxiety-like behaviors of male Sprague Dawley rats in the open field arena. β-EP transplantation into the PVN reduced anxiety-like behavior in the open field arena (A–F). β-EP transplantation increased the amount of time spent in the center of the arena (A), increased exploratory activity in the center (B), and increased stretch-attends behavior in the center (E). β-EP transplantation had no effect on general locomotor activity (total line crossings) (C) and no effect on rearing behavior (D), while almost completely abolishing grooming behavior (F). Student’s t test, *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN attenuated the hyper corticosterone response to acute restraint stress and reduced CRH and CRHR1 gene expression in the PVN and AMY in prenatal alcohol exposed male rats

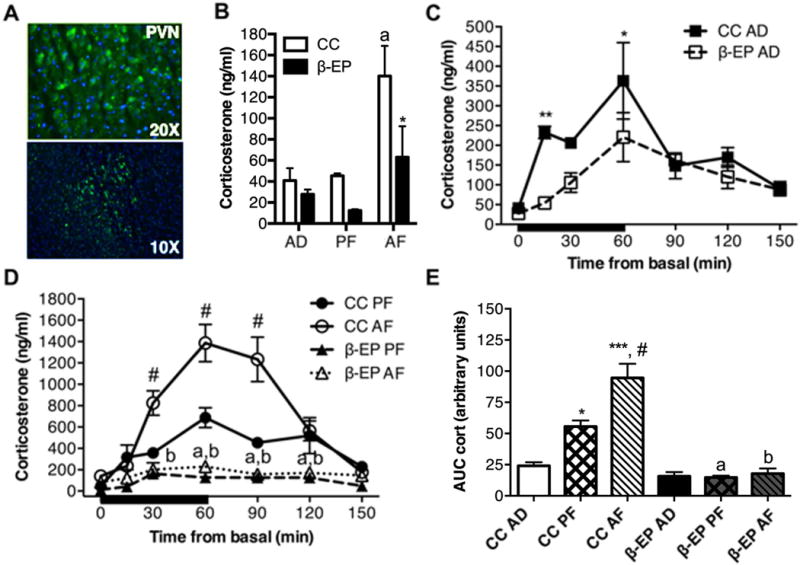

We have previously shown that in situ differentiated β-EP neurons transplanted in the medial parvocellular area of the PVN remained viable for 3 or more months (Boyadjieva et al., 2009; Sarkar et al., 2008). Here, we showed that β-EP transplanted neurons were present in the PVN and continued to produce β-EP after 6 months (Fig. 4A), suggesting these cells remain viable for long periods of time following transplantation.

Figure 4.

The effects of β-EP neuronal transplantation on corticosterone response during restraint stress in prenatal alcohol exposed (AF) male Fischer rats. Representative immunofluorescence pictures of β-EP cells in the PVN of the hypothalamus at 6 months after transplantation (A). Green staining represents β-EP and blue staining represent DAPI. β-EP transplantation reduced the basal levels of corticosterone in AF rats (B) and AD, PF, and AF rats (C,D) in response to restraint stress. β-EP transplantation reduced the hyper-response of corticosterone to restraint stress in AF rats (D,E). Area under the curve (AUC) calculated from time-series analyses (see C,D) shows a reduction in total corticosterone levels in all groups (E). Data shown in B were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with main effects of treatment F(2, 18) = 11.81, p = 0.0006, and group F(1, 18) = 9.574, p = 0.0066, and no interaction followed by comparison tests, a, CC AF vs. CC AD or CC PF p < 0.01; *, CC AF vs. β-EP AF p < 0.05. Data shown in C, D were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with main effects of group, F(2, 58) = 64.24, p < 0.0001, and time, F(6, 58) = 31.99, p < 0.0001, and an interaction F(12, 58) = 9.3, p < 0.0001) followed by Bonferroni, *, p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; a, p < 0.01 CC PF vs. β-EP PF p < 0.01; b, CC AF vs. β-EP AF p < 0.01;; #, CC AF vs. β-EP PAF p < 0.001. Data shown in E were analyzed by one-way ANOVA, F(5, 18) = 31.10, p < 0.0001), followed by Bonferroni corrected multiple comparisons tests, *, CC PF vs. CC AD p < 0.05; ***, CC AF vs. CC AD p < 0.001; #, AF vs. CC PF p < 0.05 CC; a, β-EP PF vs. CC PF p < 0.05; and b, β-EP AF vs. CC AF p < 0.05.

To further characterize the impact of β-EP transplanted cells on the HPA axis stress response, control AD and PF, and AF rats underwent 60 min of restraint stress, during and after which, blood samples were collected to measure peripheral levels of corticosterone. Basal corticosterone levels from AF rats were significantly elevated compared to both AD and PF control groups (Fig. 4B). β-EP transplantation in AD (Fig. 4C and 4D), and PF and AF rats significantly attenuated the corticosterone response to restraint stress. Moreover, the hyper response of corticosterone in AF rats was completely normalized to AD control levels during and following restraint stress (Fig. 4D,E). β-EP transplants also attenuated the corticosterone response to stress in AD and PF control groups (Fig. 4C–E).

We measured Crh and Crhr1 gene expression in the PVN and the AMY in AD, PF, and AF rats with and without β-EP cell transplantation. AF significantly elevated Crh gene expression in CC control rats in the PVN and the AMY (Fig. 5A) and the AMY (Fig. 5C). While no differences were observed for Crhr1 expression in the PVN between groups (Fig. 5B), AF increased Crhr1, and β-EP normalized the expression of Crhr1 in the AMY (Fig. 5D). These results provide further evidence that β-EP neuron transplants are able to reduce peripheral corticosterone release and suppress CRH neuronal function in brain areas that regulate stress response and anxiety behaviors.

Figure 5.

The effects of β-EP neuronal transplantation on Crh and Crhr1 gene expression in the PVN and AMY of AF male Fischer rats. AF increased Crh expression in the PVN (A) and AMY (C), which was reduced by β-EP transplantation into the PVN (A,C). AF had no effect on Crhr1 expression in the PVN, but increased it’s expression in the AMY, which was reduced by β-EP transplantation into the PVN (B,D). Two-way ANOVA [A, F(1, 18) = 17.03, p = 0.0006, and group, F(2, 18) = 3.794, p < 0.05; B, F(1, 18) = 4.12, p < 0.05, and group, F(2, 18) = 4.375, p < 0.05, but no interaction, F(2, 18) = 2.56, p = 0.10; C, F(1, 18) = 30.66, p < 0.001, and group, F(2, 18) = 5.889, p < 0.05, and an interaction, F(2, 18) = 12.76, p < 0.001: D, F(1, 18) = 4.12, p < 0.05, and group, F(2, 18) = 4.375, p < 0.05, but no interaction, F(2, 18) = 2.56, p = 0.10] followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests (CC AF vs. β-EP AF, ** p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; CC AD vs. CC AF, a, p < 0.05).

β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN reduced anxiety-like behavior of prenatal alcohol exposed male rats in the elevated plus maze

A cohort of AF male rats transplanted with either CC control or β-EP cells, along with AD and PF control cohorts were tested in the elevated plus maze. AF treatment significantly reduced the number of open arm entries compared to PF and AD rats, which was reversed by β-EP transplants, as shown by β-EP transplanted AF rats displaying more open arm entries than CC transplanted rats (Fig. 6B). Fetal alcohol treatment moderately, but not significantly, reduced the open arm time (Fig. 6A). The treatment did not have any effects on closed arm entries (Fig. 6C), rears (Fig. 6D), head-dips (Fig. 6E), and stretch-attends (Fig. 6F). β-EP transplantation increased open arm times and entries (Fig. 6A, B) and the number of head-dips on the open arms (Fig. 6E) in AF rats. β-EP transplantation appeared to have selective effects on elevated plus maze behaviors associated with anxiety-like behaviors in AF treated rats, while having minimal effects on anxiety behavior in AD and PF control groups.

Figure 6.

The effects of β-EP neuronal transplantation on anxiety-like behaviors of AF male Fischer rats in the elevated plus maze. β-EP transplantation into the PVN reduced anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze selectively in AF male Fischer rats (A,B,E). β-EP transplantation increased the amount of time spent in the open arms (A), increased the number of entries into the open arms (B), and increased the number of head-dips on the open arms (E). β-EP transplantation had no effect on general locomotor activity (number of closed arm entries) (C) and no effect on rearing behavior (D) or stretch-attends (F). Two-way ANOVA (A, main effect of group, F(2, 42) = 14.84, p < 0.0001, without an overall effect of treatment, and a significant interaction, F(2, 42) = 4.881, p < 0.01; B, main effect of treatment, F(1, 42) = 6.948, p < 0.012, with no overall effect of group) followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests, CC AF vs. β-EP AF, * p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001; a, CC PF vs. CC AF, p < 0.05.; b, CC AD and CC PF vs. CC AF, p < 0.05.

β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN altered anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze of male and female selectively-bred NP and P rats

Male and female NP and P rats were transplanted with either cortical (CC) or β-EP cells in the PVN and tested in the elevated plus maze. Although no changes were observed in other behavioral measures, both male and female P rats displayed a modest, yet significant, reduction in the amount of time spent in the open arms (Fig. 7A), and this effect was completely reversed by β-EP neuronal transplantation. β-EP transplantation into the PVN of male and female NP rats appeared to have no effect on their behavior in the elevated plus maze (Fig. 7A–H). These results suggest β-EP transplants influence anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze of selectively bred P rats.

Figure 7.

The effects of β-EP neuronal transplantation on anxiety-like behaviors of NP and P rats in the elevated plus maze. β-EP transplantation into the PVN increased the amount of time spent in the open arms in male (A) and female (B) P rats. β-EP transplantation had no effect on any other behavioral measure in the elevated plus maze (C–H). Two-way ANOVA [A, main effects of group, F(1, 28) = 6.663, p < 0.01, and treatment, F(1,28) = 14.65, p < 0.001; B, main effects of treatment F(1,31) = 4.218] followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc tests, CC P vs. β-EP P, * p < 0.05; a, CC P vs. β-EP NP, p < 0.05.

β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN altered ethanol intake during limited and continuous access paradigms following restraint stress in selectively-bred NP and P male rats

We investigated whether β-EP transplantation had effects on alcohol drinking in separate cohorts of NP and P male rats during limited and continuous access to a 10% ethanol containing solution and water. Increased alcohol preference in male P rats was largely unaffected by repeated restraint stress or β-EP transplantation (Fig. 8); however, during restraint, β-EP transplanted P rats with limited alcohol access displayed a small, yet significant, reduction in alcohol preference (~15%) (Fig. 8A). However, under continuous access conditions, β-EP transplanted P rats actually increased their alcohol preference during restraint, which was maintained following restraint (Fig. 8B). β-EP transplanted NP rats displayed a significant increase in alcohol preference during restraint under limited access conditions (Fig. 8). During continuous access conditions, β-EP transplanted NP rats displayed an increase in alcohol preference prior to and during restraint stress, which was significantly reduced following restraint (Fig. 8B). Thus, β-EP transplantation into the PVN altered alcohol preference in both NP and P rats depending on whether stress was acutely present or following repeated stress.

Figure 8.

The effects of β-EP neuronal transplantation on alcohol preference under limited (access during the first 3h of the dark cycle) or continuous (24h) access to 10% ethanol drinking solution in male NP and P rats prior to, during, and after repeated restraint stress. β-EP neuronal transplantation had differential effects on alcohol preference during limited (A) or continuous (B) ethanol access depending on the stress condition. Each bar represents averages across five days of the baseline, restraint, and post-restraint phases. Two-way ANOVA [A, main effects of treatment, F(2, 138) = 3.72, p = 0.05, and group, F(3, 138) = 158.7, p < 0.0001, and an interaction, F(6, 138) = 5.727, p < 0.0001; B, main effects of experimental treatment, F(2, 138) = 8.098, p < 0.001, and group, F(3, 138) = 711.9, p < 0.0001, and an interaction, F(6, 138) = 13.37, p < 0.0001] followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons posthoc tests, *, CC P vs. P β-EP, *p < 0.05, **, CC P vs. β-EP P p < 0.01; a, CC NP vs. P β-EP, p < 0.05; b, CC NP vs. CC β-EP, p < 0.05; c, β-EP NP restraint continuous access vs. post-restraint, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Establishing the role of β-EP in regulating the effects of alcohol exposure and alcohol intake will lead to a better understanding of the neurobiological basis of alcohol use disorders and possibly provide novel treatment approaches for alleviating the consequences of alcohol exposure during development and in adulthood. These studies provide novel evidence for the role of β-EP neuronal deficiency in regulating the stress response and anxiety behavior in fetal alcohol exposed animals. We report that β-EP transplantation into the PVN reduces the hyper-corticosterone response to acute restraint stress and reduces baseline anxiety-like behavior in fetal alcohol exposed adult male rats. Interestingly, β-EP transplantation also altered alcohol preference in P and NP rats and reduced anxiety-like behavior in both male and female P rats.

Previously, we reported that β-EP transplantation into the PVN reduced the CRH neuronal response to an immune challenge in fetal alcohol exposed rats (Boyadjieva et al., 2009). Here, we extend these findings by demonstrating the β-EP neuronal transplantation reduces Crh and Crhr1 gene expression in the PVN and AMY of AF rats and significantly attenuated the peripheral corticosterone response to acute restraint stress in AD, PF, and AF rats. Prenatal alcohol exposure increased the expression of Crh in the hypothalamus and the amygdala, while Crhr1 was only increased in the amygdala, which was significantly reduced by β-EP transplantation. Similarly, the hyper stress response of AF rats was completely abolished by β-EP transplantation. Our results are consistent with previous studies reporting enhanced stress reactivity in prenatal alcohol exposure animals (Ogilvie et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1990).

β-EP transplantation also significantly attenuated the corticosterone response to acute restraint in both control AD and PF cohorts, suggesting the effects of β-EP on stress response are not specific to developmental alcohol exposure. Altered β-EP levels are correlated with a high incidence of psychiatric diseases, including anxiety and also depression, in those with fetal alcohol syndrome (Bernstein et al., 2002; Darko et al., 1992). β-EP neuronal transplantation into the PVN reduced the anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze of AF male rats without altering general locomotor activity, suggesting restoring the β-EP neuronal deficiency in the hypothalamus reverses the anxiety phenotype induced by prenatal alcohol exposure. Indeed, β-EP deficiency leads to exaggerated stress reactivity and increased anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze and light-dark box behavioral assays (Grisel et al., 2008). Impaired negative feedback of the HPA axis may be amplify the reactive to stressful stimuli (Sarkar et al., 2007). These findings suggest β-EP attenuates the behavioral response to stressful stimuli, and alcohol exposure, during the prenatal period or during adulthood, impairs hypothalamic β-EP neuronal function.

Previous studies demonstrate that P rats have altered stress neurobiology and neurochemical processes compared to NP rats that may be associated with their increased anxiety-like behavior and increased alcohol intake (Chester et al., 2004; Ehlers et al., 1992; Cullen et al., 2013; Yong et al., 2014). NP and P rats, which are selectively bred for low and high alcohol drinking, respectively, exhibit baseline differences in anxiety behavior, such that P rats display a more anxious behavioral phenotype compared to their NP counterparts (Baldwin et al., 1991; Stewart et al., 1993). As such, the elevated plus maze appears to be the most sensitive for examining anxiety-like behavior in these selectively bred lines. We show that both male and female P rats spent modestly, yet significantly, less time on the open arms of the elevated plus maze. β-EP neuronal transplantation appeared to reverse this anxiety-like phenotype only in the P line, with an enhanced effect observed in the female P rats. Future studies will expand on this result by determining the effects of β-EP neurons on depression-like behaviors and other behavioral assays of anxiety in the P and NP rats.

In addition to the anxiety-like phenotype, the P rats also show enhanced alcohol intake following repeated restraint stress, which is consistent with a previous study (Chester et al., 2004). We explored whether β-EP transplantation would reduce alcohol drinking during both limited and continuous access conditions during and following five days of restraint stress. We initially hypothesized that β-EP neuronal transplantation may decrease alcohol drinking under stress conditions only in the P rats considering other studies have shown certain types of stressors elevate alcohol intake in P rats (Chester et al., 2004; Overstreet et al., 2007). However, β-EP neuronal transplantation seemed to have only modest reductions in alcohol intake during restraint under scheduled limited alcohol access, which was restored to baseline alcohol preference levels following restraint, whereas under continuous access, β-EP neurons increased alcohol preference during and following restraint stress. In NP rats, β-EP neuronal transplantation actually increased alcohol preference during continuous access as well as during limited access only during restraint stress. The relationship between stress and alcohol intake is complex. Stress-induced alcohol drinking in rodents in influenced by numerous factors, such as the type, duration, and frequency of the stressor, and alcohol-related factors, such as the history, level, pattern, and timing of alcohol intake (Becker et al., 2011; Spanagel et al., 2014). Similar to other studies restraint stress had minimal effects on alcohol preference during both limited and continuous access to alcohol in P and NP rats (Bertholomey et al., 2011; Vengeliene et al., 2003). Other stressors, such as foot-shock, are more reliable in inducing increased home cage alcohol drinking in P rats (Vengeliene et al., 2003). It is possible we would observe a reduction in overall alcohol preference under those conditions in β-EP transplanted rats.

Alcoholism and anxiety disorders are frequently comorbid and alcoholics often report consuming alcohol to “self-medicate”, or to reduce anxiety and other withdrawal symptoms (Compton et al., 2007; Zimmerman and Chelminski, 2003). We report that β-EP neuronal transplantation reduces anxiety-like behavior in both male and female high alcohol preferring rats, although the effects of the transplantation, even under repeated stress conditions, on alcohol preference were very minimal and seemed to depend on whether the stress is acutely present or whether access to alcohol is freely available. Moreover, β-EP transplanted NP rats actually increased their alcohol preference during restraint stress, which seems paradoxical considering it has been shown that β-EP levels are linked to higher risk for excessive alcohol intake and alcoholism (Roth-Deri et al., 2008; Gianoulakis et al., 1996; Wand et al., 1998). Although speculative, it is possible that enhanced β-EP signaling in the hypothalamus due to the transplantation enhances NP and P rats’ capacity to consume alcohol under certain stress conditions. The relationship between stress, resiliency, anxiety, and alcohol consumption is complex (Becker et al., 2011; Spanagel et al., 2014). Indeed, there are both shared and disparate genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying these phenotypes, as has been shown with depression-like behaviors in P rats (Bertholomey et al., 2011; Godfrey et al., 1997), which may or may not be uniformly influenced by β-EP signaling in the hypothalamus.

Overall, these findings suggest that altered β-EP neuronal functioning regulates the hyper-responsiveness of the stress system in those with altered HPA axis regulation to acute stress and anxiety-like behavior. These data suggest β-EP may be an important contributing factor the relationship between stress, alcohol drinking, and reward.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Maria Ortigüela for surgical assistance. This work is partly supported by a National Institute of Health grant R37AA08757.

References

- Baldwin HA, Rassnick S, Rivier J, Koob GF, Britton KT. CRF antagonist reverses the “anxiogenic” response to ethanol withdrawal in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1991;103:227–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02244208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barfield ET, Barry SM, Hodgin HB, Thompson BM, Allen SS, Grisel JE. Beta-endorphin mediates behavioral despair and the effect of ethanol on the tail suspension test in mice. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2010;34:1066–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF, Doremus-Fitzwater TL. Effects of stress on alcohol drinking: a review of animal studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:131–156. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert B, Fink H, Sohr R, Rex A. Different effects of diazepam in Fischer rats and two stocks of Wistar rats in tests of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:411–420. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00629-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, Krell D, Emrich HM, Baumann B, Danos P, Diekmann S, Bogerts B. Fewer beta-endorphin expressing arcuate nucleus neurons and reduced beta-endorphinergic innervation of paraventricular neurons in schizophrenics and patients with depression. Cellular and molecular biology. 2002;48:OL259–265. Online Pub. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholomey ML, West CH, Jensen ML, Li TK, Stewart RB, Weiss JM, Lumeng L. Genetic propensities to increase ethanol intake in response to stress: studies with selectively bred swim test susceptible (SUS), alcohol-preferring (P), and non-preferring (NP) lines of rats. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:157–167. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyadjieva NI, Ortiguela M, Arjona A, Cheng X, Sarkar DK. Beta-endorphin neuronal cell transplant reduces corticotropin releasing hormone hyperresponse to lipopolysaccharide and eliminates natural killer cell functional deficiencies in fetal alcohol exposed rats. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2009;33:931–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sonne SC. The role of stress in alcohol use, alcoholism treatment, and relapse. Alcohol research & health: the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 1999;23:263–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester JA, Blose AM, Zweifel M, Froehlich JC. Effects of stress on alcohol consumption in rats selectively bred for high or low alcohol drinking. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2004;28:385–393. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000117830.54371.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64:566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz AP, Frei F, Graeff FG. Ethopharmacological analysis of rat behavior on the elevated plus-maze. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 1994;49:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BA, La Flair LN, Storr CL, Green KM, Alvanzo AA, Mojtabai R, Pacek LR, Crum RM. Association of comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder symptoms with health-related quality of life: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of addiction medicine. 2013;7:394–400. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829faa1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darko DF, Risch SC, Gillin JC, Golshan S. Association of beta-endorphin with specific clinical symptoms of depression. The American journal of psychiatry. 1992;149:1162–1167. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt MJ, File SE, Gessa GL, Grant KA, Guerri C, Hoffman PL, Kalant H, Koob GF, Li TK, Tabakoff B. Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on the central nervous system. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1998;22:998–1040. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Chaplin RI, Wall TL, Lumeng L, Li TK, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF): studies in alcohol preferring and non-preferring rats. Psychopharmacology. 1992;106:359–364. doi: 10.1007/BF02245418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famy C, Streissguth AP, Unis AS. Mental illness in adults with fetal alcohol syndrome or fetal alcohol effects. The American journal of psychiatry. 1998;155:552–554. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CK, Zorrilla EP, Lee MJ, Rice KC, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor 1 antagonists selectively reduce ethanol self-administration in ethanol-dependent rats. Biological psychiatry. 2007;61:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoulakis C, de Waele JP, Thavundayil J. Implication of the endogenous opioid system in excessive ethanol consumption. Alcohol. 1996;13:19–23. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(95)02035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey CD, Froehlich JC, Stewart RB, Li TK, Murphy JM. Comparison of rats selectively bred for high and low ethanol intake in a forced-swim-test model of depression: effects of desipramine. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:729–733. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisel JE, Bartels JL, Allen SA, Turgeon VL. Influence of beta-Endorphin on anxious behavior in mice: interaction with EtOH. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:105–115. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1161-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans KG, Verma P, Yoon E, Yu W, Weinberg J. Prenatal alcohol exposure increases vulnerability to stress and anxiety-like disorders in adulthood. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1144:154–175. doi: 10.1196/annals.1418.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang BH, Stewart R, Zhang JK, Lumeng L, Li TK. Corticotropin-releasing factor gene expression is down-regulated in the central nucleus of the amygdala of alcohol-preferring rats which exhibit high anxiety: a comparison between rat lines selectively bred for high and low alcohol preference. Brain research. 2004;1026:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston AL, File SE, Dingemanse J, Aranko K. Diazepam reverses the effects of pentylenetetrazole in rat pups by acting at type 2 benzodiazepine receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1989;32:823–825. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalueff AV, Tuohimaa P. The Suok (“ropewalking”) murine test of anxiety. Brain research. Brain research protocols. 2005;14:87–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Watchus J, Shalev U, Shaham Y. The role of corticotrophin-releasing factor in stress-induced relapse to alcohol-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2000;150:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s002130000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Imaki T, Vale W, Rivier C. Effect of prenatal exposure to ethanol on the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of the offspring: Importance of the time of exposure to ethanol and possible modulating mechanisms. Molecular and cellular neurosciences. 1990;1:168–177. doi: 10.1016/1044-7431(90)90022-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mammolenti M, Gajavelli S, Tsoulfas P, Levy R. Absence of major histocompatibility complex class I on neural stem cells does not permit natural killer cell killing and prevents recognition by alloreactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vitro. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1101–1110. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, Robinson LK, Buckley D, Manning M, Hoyme HE. Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on recent in-school studies. Developmental disabilities research reviews. 2009;15:176–192. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez M, Morales-Mulia M. Role of mu and delta opioid receptors in alcohol drinking behaviour. Current drug abuse reviews. 2008;1:239–252. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801020239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Circadian rhythm of cell proliferation in the telencephalic ventricular zone: effect of in utero exposure to ethanol. Brain Res. 1992;595:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91447-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molteno CD, Jacobson JL, Carter RC, Dodge NC, Jacobson SW. Infant emotional withdrawal: a precursor of affective and cognitive disturbance in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:479–88. doi: 10.1111/acer.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Stewart RB, Bell RL, Badia-Elder NE, Carr LG, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of the Indiana University rat lines selectively bred for high and low alcohol preference. Behav Genet. 2002;32:363–388. doi: 10.1023/a:1020266306135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie KM, Rivier C. Prenatal alcohol exposure results in hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of the offspring: modulation by fostering at birth and postnatal handling. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 1997;21:424–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet-Morin I, Dionne G, Lupien SJ, Muckle G, Côté S, Pérusse D, Tremblay RE, Boivin M. Prenatal alcohol exposure and cortisol activity in 19-month-old toddlers: an investigation of the moderating effects of sex and testosterone. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:297–307. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1955-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet DH, Knapp DJ, Breese GR. Drug challenges reveal differences in mediation of stress facilitation of voluntary alcohol drinking and withdrawal-induced anxiety in alcohol-preferring P rats. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2007;31:1473–1481. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey SC, Zhang H, Roy A, Xu T. Deficits in amygdaloid cAMP-responsive element-binding protein signaling play a role in genetic predisposition to anxiety and alcoholism. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:2762–2773. doi: 10.1172/JCI24381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky PM, Kjaer A, Sutton SW, Sawchenko PE, Vale W. Central activin administration modulates corticotropin-releasing hormone and adrenocorticotropin secretion. Endocrinology. 1991;128:2520–2525. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-5-2520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro SC, Kennedy SE, Smith YR, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK. Interface of physical and emotional stress regulation through the endogenous opioid system and mu-opioid receptors. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2005;29:1264–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Deri I, Green-Sadan T, Yadid G. Beta-endorphin and drug-induced reward and reinforcement. Progress in neurobiology. 2008;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar DK, Boyadjieva NI, Chen CP, Ortiguela M, Reuhl K, Clement EM, Kuhn P, Marano J. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate differentiated beta-endorphin neurons promote immune function and prevent prostate cancer growth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9105–9110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800289105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar DK, Kuhn P, Marano J, Chen C, Boyadjieva N. Alcohol exposure during the developmental period induces beta-endorphin neuronal death and causes alteration in the opioid control of stress axis function. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2828–2834. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar DK, Zhang C. Beta-endorphin neuron regulates stress response and innate immunity to prevent breast cancer growth and progression. Vitamins and hormones. 2013;93:263–276. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-416673-8.00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider ML, Moore CF, Adkins MM. The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on behavior: rodent and primate studies. Neuropsychol Rev. 2011;21:186–203. doi: 10.1007/s11065-011-9168-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Noori HR, Heilig M. Stress and alcohol interactions: animal studies and clinical significance. Trends in neurosciences. 2014;37:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RB, Gatto GJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM. Comparison of alcohol-preferring (P) and nonpreferring (NP) rats on tests of anxiety and for the anxiolytic effects of ethanol. Alcohol. 1993;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(93)90046-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Branch BJ, Van Zuylen JE, Redei E. Maternal alcohol consumption and stress responsiveness in offspring. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 1988;245:311–317. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2064-5_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengeliene V, Siegmund S, Singer MV, Sinclair JD, Li TK, Spanagel R. A comparative study on alcohol-preferring rat lines: effects of deprivation and stress phases on voluntary alcohol intake. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2003;27:1048–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000075829.81211.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walf AA, Frye CA. The use of the elevated plus maze as an assay of anxiety-related behavior in rodents. Nature protocols. 2007;2:322–328. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand GS, Schumann H. Relationship between plasma adrenocorticotropin, hypothalamic opioid tone, and plasma leptin. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1998;83:2138–2142. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffgramm J. Free choice ethanol intake of laboratory rats under different social conditions. Psychopharmacology. 1990;101:233–239. doi: 10.1007/BF02244132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne O, Sarkar DK. Stress and neuroendocrine-immune interaction: a therapeutic role for β-endorphin. In: Kusnecov A, Anisman H, editors. Handbook of Psychoneuroimmunology. Wiley, Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2013. pp. 198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Yong W, Spence JP, Eskay R, Fitz SD, Damadzic R, Lai D, Foroud T, Carr LG, Shekhar A, Chester JA, Heilig M, Liang T. Alcohol-preferring rats show decreased corticotropin-releasing hormone-2 receptor expression and differences in HPA activation compared to alcohol-nonpreferring rats. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2014;38:1275–1283. doi: 10.1111/acer.12379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Babapoor-Farrokhran S, Rezayof A. Involvement of opioidergic system of the ventral hippocampus, the nucleus accumbens or the central amygdala in anxiety-related behavior. Life sciences. 2008;82:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Lagrange AH, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Tolerance of hypothalamic beta-endorphin neurons to mu-opioid receptor activation after chronic morphine. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1996;277:551–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. Generalized anxiety disorder in patients with major depression: is DSM-IV’s hierarchy correct? The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160:504–512. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]