Significance

Genetic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a debilitating disease affecting 1 in 500 of the general population, and there is no effective therapy to reverse or prevent its development and/or progression to heart failure. To inhibit a detrimental HCM phenotype induced by the D166V mutation of cardiac myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) in mice that also show reduced phosphorylation of endogenous cardiac RLC, constitutively phosphorylated D166V mutant mice were produced and tested. Our in-depth investigation of heart morphology, structure, and function of S15D-D166V mice provided evidence for the pseudophosphorylation-elicited prevention of the progressive HCM-D166V phenotype. This study is significant for the field of HCM, and our findings may constitute a novel therapeutic modality to battle hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with RLC mutations.

Keywords: cardiomyopathy, hemodynamics, myocardial contraction, X-ray structure, myosin RLC

Abstract

Myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)-dependent phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain (RLC) of cardiac myosin is known to play a beneficial role in heart disease, but the idea of a phosphorylation-mediated reversal of a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) phenotype is novel. Our previous studies on transgenic (Tg) HCM-RLC mice revealed that the D166V (Aspartate166 →Valine) mutation-induced changes in heart morphology and function coincided with largely reduced RLC phosphorylation in situ. We hypothesized that the introduction of a constitutively phosphorylated Serine15 (S15D) into the hearts of D166V mice would prevent the development of a deleterious HCM phenotype. In support of this notion, MLCK-induced phosphorylation of D166V-mutated hearts was found to rescue some of their abnormal contractile properties. Tg-S15D-D166V mice were generated with the human cardiac RLC-S15D-D166V construct substituted for mouse cardiac RLC and were subjected to functional, structural, and morphological assessments. The results were compared with Tg-WT and Tg-D166V mice expressing the human ventricular RLC-WT or its D166V mutant, respectively. Echocardiography and invasive hemodynamic studies demonstrated significant improvements of intact heart function in S15D-D166V mice compared with D166V, with the systolic and diastolic indices reaching those monitored in WT mice. A largely reduced maximal tension and abnormally high myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity observed in D166V-mutated hearts were reversed in S15D-D166V mice. Low-angle X-ray diffraction study revealed that altered myofilament structures present in HCM-D166V mice were mitigated in S15D-D166V rescue mice. Our collective results suggest that expression of pseudophosphorylated RLC in the hearts of HCM mice is sufficient to prevent the development of the pathological HCM phenotype.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a complex and heterogeneous disorder with extensive diversity in the course of the disease, age of onset, severity of symptoms, and risk for sudden cardiac death (SCD) (1). HCM is the most common cause of SCD among young people, particularly in athletes (2). The characteristic pathologic features of HCM include cardiac hypertrophy with disproportionate involvement of the ventricular septum and extensive disorganization of the myocyte structure and myocardial fibrosis (3). At present, there is no cure for HCM, and it is now becoming evident that any effective therapy must target the underlying mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of the disease.

The D166V (aspartic acid replaced by valine) mutation in the ventricular myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) was reported by Richard et al. to cause HCM and SCD (4). Our extensive study of the mechanisms underlying the D166V phenotype revealed that the severity of mutation-induced effects in transgenic (Tg) mice correlated with reduced in situ RLC phosphorylation (5, 6). Tg-D166V papillary muscle preparations demonstrated a significantly lower contractile force and abnormally increased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity compared with Tg-WT, expressing a nonmutated human ventricular RLC (5). Likewise, single molecule detection applied to fluorescently labeled cardiac myofibrils from Tg-D166V mice showed slower rates of cross-bridge cycling, and, as in Kerrick et al. (5), these functional abnormalities were paralleled by a low level of RLC phosphorylation compared with Tg-WT hearts (7).

Cardiac myosin RLC is a major regulatory subunit of muscle myosin and a modulator of the troponin and Ca2+-controlled regulation of muscle contraction (8). It is localized at the head-rod junction of the myosin heavy chain (MHC), and, in addition to the N-terminal Ca2+-Mg2+ binding site, it also contains the myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)-specific phosphorylatable Serine15. Phosphorylation of Ser15 has been recognized to play an important role in cardiac muscle contraction under normal and disease conditions (9). Significantly reduced RLC phosphorylation was reported in patients with heart failure (10, 11) and observed in animal models of cardiac disease (5, 12–14). Attenuation of RLC phosphorylation in cardiac MLCK knockout mice led to ventricular myocyte hypertrophy, with histological evidence of necrosis and fibrosis, and to mild dilated cardiomyopathy (15, 16). These results and our decade-long investigation of the RLC mutant-induced pathology of the heart suggest that RLC phosphorylation may have an important physiological role in the heart and serve as a rescue tool to mitigate detrimental disease phenotypes.

We first addressed this hypothesis in vitro and pursued the MLCK-induced phosphorylation studies on Tg-D166V mice (6), followed by the use of the pseudophosphorylation mimetic proteins exchanged in porcine myosin or skinned muscle fibers (17). Results from both lines of investigation showed that phosphorylation of RLC could counterbalance the adverse contractile effects of an HCM-causing mutation in vitro. In this report, we aimed to test the idea of pseudophosphorylation-induced prevention of a deleterious phenotype in HCM mice. Transgenic S15D-D166V mice were generated expressing the pseudophosphorylated Ser15 (S15D) in the background of the disease-causing D166V mutation. Functional, structural, and morphological assessments were conducted on Tg-S15D-D166V mice, and the results were compared with those of previously generated Tg-D166V (5) and Tg-WT (18) mice. Our findings indicate that myosin phosphorylation may have an important translational application and be used to prevent the development of a severe RLC mutant-induced HCM phenotype.

Results

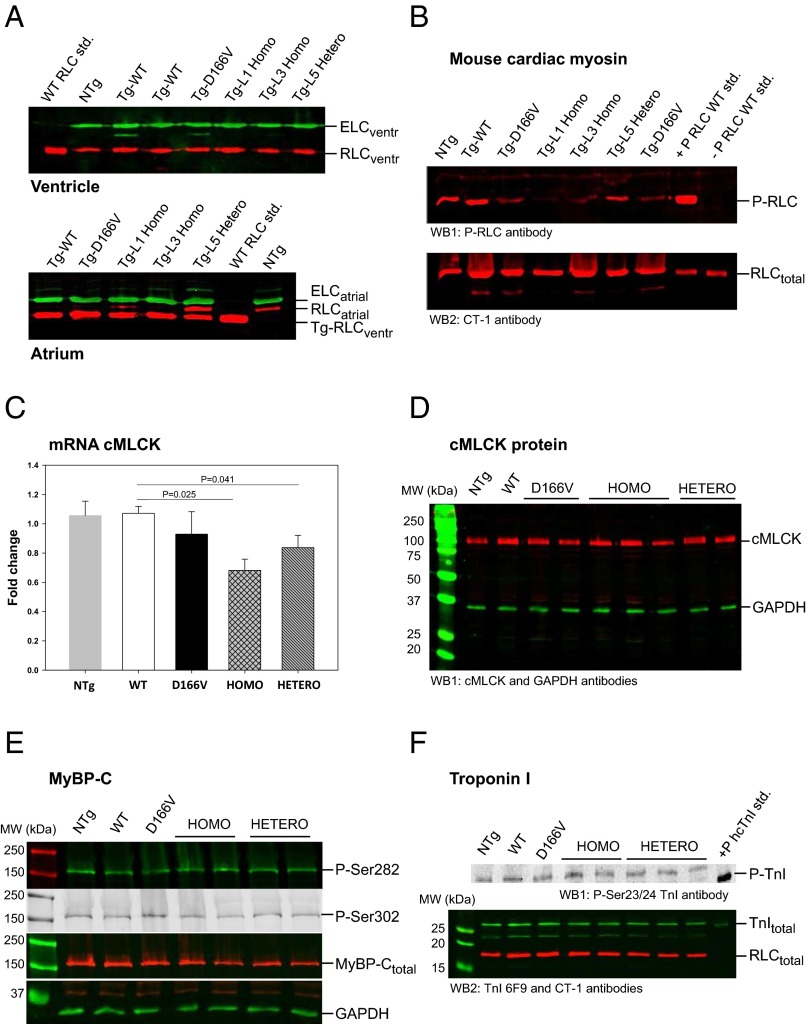

Creation of genetically manipulated transgenic mice expressing the HCM-associated D166V mutation of the myosin ventricular RLC in their hearts has been extremely helpful in unraveling the molecular and cellular mechanisms of pathogenesis of HCM (5). To follow up on our in vitro experiments (6, 17) and to test the hypothesis that pseudo-RLC phosphorylation is capable of preventing the development of detrimental D166V phenotypes in vivo, we produced three lines of the α-MHC–driven transgenic “rescue mice” expressing a constitutively phosphorylated RLC-S15D (serine mutated to aspartic acid) in a background of RLC-D166V. Transgene expression and the incorporation of the S15D-D166V mutant into the mouse myocardium were determined in ventricular and atrial lysates (four to six hearts per group) or in myofibrils purified from three to seven hearts per line (L1, L3, and L5). Fig. 1A shows representative Western blots of myofibril preparations from L1 expressing 95 ± 3% (n = 9), L3 = 97 ± 2% (n = 5), and L5 = 56 ± 3% (n = 11) of the S15D-D166V double mutant of human ventricular RLC [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) no. P10916] substituted for endogenous mouse RLC (NCBI no. P51667). For clarity, we refer to the highly expressing lines L1 and L3 as Homo-rescue and to L5 as Hetero-rescue (zygote) mice. All in vivo and in vitro experiments were conducted on Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice of both genders, and the results were compared with those obtained for age-matched and previously generated D166V (93 ± 3%) (5) and WT (L2 = 99 ± 1%) (18).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of Tg-S15D-D166V transgenic mice. All assessments were made using three to four hearts of ∼5-mo-old female and male mice of NTg, WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice (see SI Methods for details). (A) Transgenic protein expression. Two lines of S15D-D166V mice (L1 = 95 ± 3%, n = 9 and L3 = 97 ± 2%, n = 5) with nearly complete replacement of the endogenous mouse RLC with S15D-D166V are called “Homo” (homozygote); whereas in one line (L5 = 56 ± 3%, n = 11) RLC was replaced ∼50% and is referred to as “Hetero” (heterozygote)-rescue mice. Transgenic S15D-D166V lines were compared with previously generated D166V (93 ± 3%) (5) and WT (L2 = 99 ± 1%) (18). The assessment of transgene expression was achieved in mouse atrium due to different molecular weights of RLC-atrial vs. RLC-ventricular. In ventricles, both mouse endogenous and Tg-human RLC migrate with the same speed due to their similar MW. (B) RLC phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of mouse purified myosin RLC was tested in all groups of mice. Note largely reduced phosphorylation in D166V vs. WT mice, no phosphorylation in Homo-rescue, and ∼50% in Hetero-rescue mice. +P-RLC WT std., positive phosphorylation control; –P RLC WT std., negative phosphorylation control. (C) cMLCK expression by qPCR. The changes in mRNA cMLCK expression in LV heart lysates from WT, D166V, and S15D-D166V Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice are presented as fold change vs. NTg mice (FC = 1). (D) Expression of cMLCK protein by Western blotting. LV tissue from the hearts of all mice was homogenized in CHAPS solution, and 5-µg samples, dissolved in Laemmli buffer, were loaded into 12% (wt/vol) SDS/PAGE. Membranes were probed with a cMLCK-specific antibody (16). GAPDH was probed with ab9485 (Abcam), which was also used as the loading control. No significant differences were observed in cMLCK expression in the hearts of mice from all groups. (E) Phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C (MyBP-C). Phosphorylation of MyBP-C at Ser282 and Ser302 was tested in LV heart lysates from all groups of mice. Approximately 20-µg samples were loaded into 10% SDS/PAGE, and the membranes were probed with phospho-specific MyBP-C antibodies (29). A rabbit polyclonal antibody was used to detect total MyBP-C. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Note no changes in MyBP-C phosphorylation or total MyBP-C protein expression between the groups. (F) Phosphorylation of troponin I (TnI). Phosphorylation of Troponin I at Ser23/24 was tested using 15% SDS/PAGE (∼20 µg protein per lane) and phospho-Ser23/24 and total-TnI antibodies. Total RLC served as a loading control. Note no changes in P-TnI between WT, D166V, and Homo/Hetero-rescue mice.

Phosphorylation of RLC and S15D Substitution Elicited Regulation of cMLCK Expression.

Ventricular preparations from all groups of mice were evaluated for the mRNA expression of cardiac MLCK (cMLCK) and the ensuing RLC phosphorylation. In agreement with our earlier reports (5, 6), a largely reduced RLC phosphorylation was observed in HCM-D166V mouse purified ventricular myosin compared with WT (Fig. 1B). As expected, ∼2% RLC phosphorylation was shown to be present in myosin from Homo-lines and ∼50% in Hetero-rescue mice. Consistent with the pattern of RLC phosphorylation, a significantly reduced cMLCK transcript expression was noted in S15D-D166V-rescue mice compared with WT and/or nontransgenic (NTg) control mice (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, diminished phosphorylation of the RLC observed in myosin from D166V hearts seemed to be independent of the cMLCK because only a slightly lower expression of cMLCK transcript was monitored in ventricles of D166V vs. WT mice (Fig. 1C). Likewise, the expression of cMLCK protein was slightly lower (not significant) in the hearts of D166V compared with WT mice, but no differences were noted compared with NTg mice or to the hearts of rescue mice (Fig. 1D). One can conclude that the availability of the cMLCK was not limited in any of the examined hearts, supporting our hypothesis that the diminished phosphorylation of D166V-myosin is a result of steric constraints rendered by the valine-for-aspartic acid substitution that triggers intramolecular structural changes in D166V-myofilaments, ultimately affecting myosin mechanochemistry and the performance of D166V-mutated hearts. Changes in RLC phosphorylation in the hearts of WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice seemed to be independent of phosphorylation of other sarcomeric proteins, and similar levels of myosin binding protein C (MyBP-C) (Fig. 1E) and Troponin I (TnI) (Fig. 1F) phosphorylation were observed in the hearts of mice from all groups, suggesting no obvious phosphorylation-induced compensatory mechanisms.

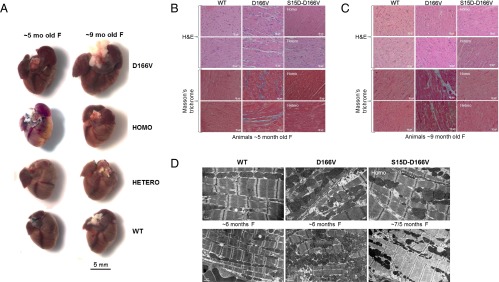

Prevention of the Development of Abnormal Heart Morphology by Pseudophosphorylation of the D166V Mutant RLC in Homo- and Hetero-Rescue Mice.

The hearts of ∼5-mo-old animals from all groups were not different in size, but, with age, HCM-D166V mice displayed hypertrophy, enlarged atria, and fatty deposits (Fig. 2A). However, the hearts of Homo- and/or Hetero-rescue mice remained indistinguishable from age-matched WT animals (Fig. 2A). Combined heart to body weight ratios [(HW/BW) × 1,000] for male and female D166V animals of 4–7 mo of age were 5.21 ± 0.12, n = 76, and the difference between HCM and WT mice (4.85 ± 0.09, n = 76) was statistically significant (P = 0.014). Both, Homo-rescue (4.44 ± 0.14, n = 25) and Hetero-rescue (4.77 ± 0.15, n = 31) mice demonstrated significantly lower HW/BW ratios compared with D166V mice (P < 0.05), and their HW/BW ratios were no different from those of WT. Therefore, pseudophosphorylation of Ser15-RLC was able to prevent abnormal hypertrophic cardiac growth in S15D-D166V mice.

Fig. 2.

Gross morphology (A), histopathology (B), and EM (C) in WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice. (A) The sizes of ∼5- and ∼9-mo-old female (F) rescue mice were compared with age- and sex-matched Tg-WT and Tg-D166V mice. Note that the hearts of ∼5-mo-old mice are the same in size whereas those of ∼9-mo-old Tg-D166V mice are much larger than control Tg-WT mice. No changes in heart size of rescue mice were noticed in both age groups of mice. (B) H&E- and Masson’s trichrome-stained heart sections from ∼5-mo-old Tg-WT, Tg-D166V, and Tg-S15D-D166V female mice. Note that the myocardium of D166V-HCM mice shows morphological abnormalities and fibrotic lesions that are not observed in the myocardium of Tg-S15D-D166V mice. (C) H&E- and Masson’s Trichrome-stained heart sections from ∼9-mo-old Tg-WT, Tg-D166V, and Tg-S15D-D166V mice. Similar to histopathology images of the hearts from young D166V-HCM mice, ∼9-mo-old animals also show distinct abnormalities and severe fibrotic lesions. In contrast, the hearts of rescue mice display no histopathological changes, and the myocardium of Tg-S15D-D166V mice looks similar to age-matched Tg-WT mice. (D) Rescue of sarcomeric ultrastructure in the hearts of Tg-S15D-D166V mice. Note severe myofilament disarray in the myocardium from D166V mice compared with WT mice. Sarcomeric abnormalities seen in HCM-D166V mice were lessened or not present in Homo- and/or Hetero-rescue mice.

Histological evaluation of the hearts from ∼5- and ∼9-mo-old female mice demonstrated abnormalities typical for HCM, including myofilament disarray and fibrosis in D166V vs. WT mice, but a lack of histopathological defects in the myocardium of ∼5-mo-old (Fig. 2B) or ∼9-mo-old (Fig. 2C) Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice. Interestingly, similar D166V-induced changes in sarcomeric ultrastructure that were not present in the hearts of S15D-D166V mice were observed by electron microscopy (EM) (Fig. 2D).

Echocardiography evaluation of ∼5-mo-old female and male mice showed a typical hypertrophic phenotype in D166V mice, manifested by significant hypertrophy of interventricular septum (IVS) in systole (s) and diastole (d), increased left ventricular posterior wall (LVPW) thickness, decreased LV inner diameter (LVID), and increased LVmass/BW compared with WT mice (Table 1). Ejection fraction (EF) was also significantly higher in HCM compared with WT mice, which is consistent with reports on HCM patients (19, 20), and indicates cardiac hypertrophy in D166V mice. These HCM-induced abnormalities observed in Tg-D166V mice were reversed or significantly improved in Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice (Table 1). Collectively, these results suggest that myosin pseudophosphorylation is sufficient to prevent the development of adverse morphological defects observed in D166V mice and could be used as an efficient remedy for pathological cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.

Table 1.

Echocardiography evaluation of transgenic WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice

| Parameter | WT | D166V | Homo | Hetero |

| No. of mice (no. of females) | 18 (12F) | 15 (12F) | 17 (11F) | 17 (12F) |

| Age, mo | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 |

| BW, g | 29.2 ± 1.7 | 28.7 ± 2.1 | 26.1 ± 1.6 | 29.6 ± 1.4 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 497 ± 14 | 448 ± 13* | 479 ± 8# | 497 ± 15# |

| LVID;d, mm | 3.88 ± 0.09 | 3.61 ± 0.06* | 3.74 ± 0.10 | 3.79 ± 0.08 |

| LVID;s, mm | 2.59 ± 0.12 | 2.04 ± 0.05** | 2.38 ± 0.08## | 2.36 ± 0.11# |

| IVS;d, mm | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 0.92 ± 0.05** | 0.72 ± 0.05## | 0.82 ± 0.02# |

| IVS;s, mm | 1.19 ± 0.06 | 1.51 ± 0.06** | 1.07 ± 0.04## | 1.23 ± 0.05## |

| LVPW;d, mm | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 0.90 ± 0.06* | 0.70 ± 0.05# | 0.73 ± 0.04# |

| LVPW;s, mm | 1.11 ± 0.04 | 1.42 ± 0.08** | 1.05 ± 0.07## | 1.19 ± 0.06# |

| LVmass/BW, mg/g weight | 3.05 ± 0.15 | 3.67 ± 0.19* | 2.83 ± 0.16## | 2.81 ± 0.12## |

| EF, % | 66 ± 2 | 82 ± 2* | 76 ± 2# | 71 ± 3# |

The M-mode and B-mode images were analyzed for cardiac morphology and function using Vevo 770 3.0.0 software (VisualSonics). Data are the average of n mice ± SEM; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 for D166V vs. WT, and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 for Homo/Hetero vs. D166V. d, diastole; EF, ejection fraction; IVS, interventricular septum; LVID, left ventricular inner diameter, PW, posterior wall; s, systole.

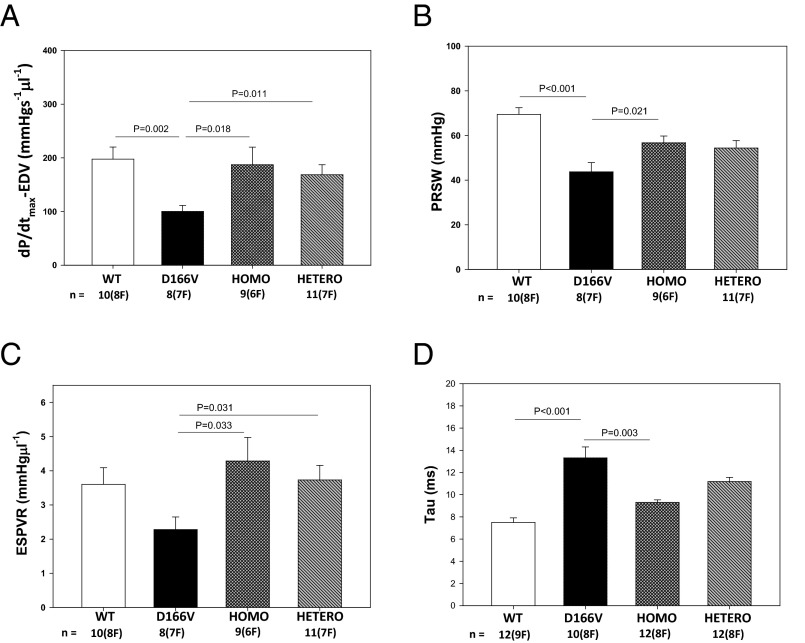

Improvement of Systolic and Diastolic Function in Homo- and Hetero-Rescue Mice Compared with HCM-D166V Mice.

Invasive hemodynamic experiments were performed on ∼5-mo-old female and male mice from all groups (8–12 mice per group). The average heart rate was 476 ± 10, 452 ± 16, 473 ± 16, and 473 ± 8 for WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice, respectively. Fig. 3 presents evidence for compromised heart function monitored in D166V vs. WT mice and a pseudophosphorylation-mediated improvement of the systolic and diastolic indices in S15D-D166V-rescue mice. The peak rate of rise in the LV pressure–end diastolic volume relationship was observed to be significantly lower in D166V vs. WT mice (100 ± 11, n = 8 mice vs. 198 ± 22, n = 10), indicating a compromised inotropic function of the heart in HCM mice (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, dP/dtmax-EDV was significantly improved in Homo-rescue (187 ± 33, n = 9) and Hetero-rescue (169 ± 19, n = 11) mice compared with D166V-HCM animals (Fig. 3A). Likewise, a largely reduced preload recruited stroke work (PRSW in mmHg) observed in D166V (44 ± 4) vs. WT (69 ± 3) mice was significantly improved in Homo-rescue (57 ± 3) and also in Hetero-rescue (54 ± 3) mice compared with D166V mice (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the slope of end systolic pressure–volume relationship (ESPVR), a measure of cardiac contractility, was decreased in D166V (2.3 ± 0.4) vs. WT (3.6 ± 0.5) mice, but was fully recovered in Homo-rescue (4.3 ± 0.7) and Hetero-rescue (3.7 ± 0.4) mice (Fig. 3C). Finally, Tau (in ms), the isovolumetric relaxation time that was prolonged in HCM-D166V (13.3 ± 1.0, n = 10) compared with WT (7.5 ± 0.4, n = 12) mice, was significantly reduced in Homo-rescue (9.3 ± 0.2, n = 12) and Hetero-rescue (11.2 ± 0.4, n = 12) mice (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Hemodynamic assessment of ∼5-mo-old WT, D166V, and S15D-D166V rescue-mice by pressure-volume loops. (A) dP/dtmax-EDV (peak rate of rise in LV pressure–end diastolic volume relationship). (B) PRSW (preload recruited stroke work). (C) ESPVR (slope = contractility of end-systolic pressure-volume relationship). (D) Relaxation time, Tau in ms. Note significantly altered heart function in HCM-D166V mice and substantial improvement of systolic and diastolic indices in Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice.

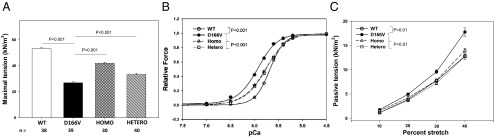

Pseudophosphorylation Elicited Inhibition of Abnormal Contractile Function Imposed by the D166V Mutation Assessed in Skinned Papillary Muscle Preparations from Tg-Rescue Mice.

The ATPase activity-pCa assays were performed on myofibrils prepared from the hearts of male and female mice (4–8 per group). Table 2 summarizes the beneficial effect of pseudo-RLC phosphorylation on both the maximal ATPase activity and Ca2+ sensitivity. The low level of ATPase observed in D166V vs. WT myofibrils was significantly improved in Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice. A mutation-induced abnormal Ca2+ sensitivity monitored in D166V preparations was significantly reversed in Homo-rescue mice and halfway improved in Hetero-mice (Table 2). These results demonstrate evidence that pseudophosphorylation of D166V played an important role in alleviating the detrimental HCM phenotype.

Table 2.

Myofibrillar ATPase activity in WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice

| Parameter | WT | D166V | Homo | Hetero |

| Max ATPase activity, µmol Pi/mgCMF/min | 0.148 ± 0.007 | 0.116 ± 0.004** | 0.162 ± 0.010## | 0.146 ± 0.009# |

| n | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| pCa50 | 5.69 ± 0.02 | 5.78 ± 0.02** | 5.68 ± 0.04# | 5.73 ± 0.05 |

| n | 9 | 5 | 7 | 5 |

Cardiac myofibrils were prepared from the ventricles of ∼5-mo-old female and male mice. Data are the average of n experiments ± SEM; **P < 0.01 for D166V vs. WT and #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 for Homo/Hetero vs. D166V.

Papillary muscle strips from 4.5- to 6.5-mo-old male and female mice from all groups were tested for maximal contractile force development and the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. At least four mice per group were tested, each heart yielding 8–15 individual skinned muscle fibers. No sex-dependent changes were noted. Reflecting an HCM detrimental phenotype, the level of maximal tension measured in kN/m2 in D166V mice (26.9 ± 0.9, n = 39 papillary muscle strips) was largely reduced compared with WT mice (53.2 ± 0.6, n = 38) (Fig. 4A) (P < 0.001). D166V-induced compromised force production was rescued in 60% in Homo-rescue (41.9 ± 0.8, n = 30) and in 25% Hetero-rescue (33.2 ± 0.9, n = 40) mice compared with D166V (Fig. 4A) (P < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Improvement of contractile function in skinned cardiac papillary muscle strips from LV of Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice compared with HCM-D166V mice. (A) Maximal tension per cross-section of muscle strip in kN/m2. Note significantly lower tension in D166V compared with WT mice. The ability to produce force was significantly increased in Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice compared with D166V. (B) Force-pCa relationship in transgenic mice. Note significantly increased Ca2+ sensitivity of force in D166V mice (black circles, pCa50 = 5.94 ± 0.01, nH = 2.09 ± 0.07, n = 37) compared with Tg-WT (open circles, pCa50 = 5.68 ± 0.01, nH = 2.86 ± 0.09, n = 30). The mutation-induced sensitizing effect was significantly reversed in Homo-rescue (gray triangles, pCa50 = 5.77 ± 0.01, nH = 1.89 ± 0.05, n = 32) and Hetero-rescue (open squares, pCa50 (midpoint) = 5.76 ± 0.01, nH (Hill coefficient) = 2.02 ± 0.05, n = 43) mice. P < 0.001 indicates significance between curves of D166V vs. WT and between D166V vs. Homo- and hetero-rescue mice. (C) Resistance to stretch monitored in skinned muscle fibers from Tg mice. Note significantly elevated passive tension in skinned papillary muscle strips from in D166V mice compared with WT. Resistance to stretch was significantly recovered in Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice (P < 0.01, as determined by ANOVA for repeated measurements). All data are average of n fibers ± SEM isolated from ∼5-mo-old female and male mice (about 10 mice per group).

Likewise, characteristic for HCM mice, the Ca2+ sensitivity of force was abnormally increased in D166V compared with WT (ΔpCa50 = 0.26) (Fig. 4B) (P < 0.001). This abnormality was corrected in S15D-D166V-rescue mice compared with D166V by ΔpCa50 = −0.17 in Homo-rescue and by ΔpCa50=-0.18 in Hetero-rescue mice (Fig. 4B) (P < 0.001).

Diastolic dysfunction, as monitored by the pressure-volume (P-V) loop measurements in D166V vs. WT mice (Fig. 3D), is often associated with alterations in muscle stiffness brought about by collagen deposition and fibrosis of the myocardium, hallmarks of HCM. As shown in Fig. 2B in Masson’s Trichrome-stained sections from D166V mice, collagen deposits were present in mice as young as ∼5 mo of age. To assess muscle stiffness, we proceeded to measure the level of passive tension (at pCa 8) in response to muscle stretch using three to four ∼5-mo-old mice per group (Fig. 4C). The following values of passive tension (in kN/m2 ± SEM) were measured as a function of muscle stretch for 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% of stretch, respectively: WT, 1.18 ± 0.09, 3.87 ± 0.14, 7.75 ± 0.21, and 12.82 ± 0.33 (n = 60 strips); D166V, 1.76 ± 0.14, 4.95 ± 0.26, 9.60 ± 0.37, and 17.76 ± 0.85 (n = 44); Homo, 1.53 ± 0.18, 4.21 ± 0.31, 7.80 ± 0.31, and 13.98 ± 0.42 (n = 22); and Hetero, 1.12 ± 0.19, 3.68 ± 0.30, 7.24 ± 0.34, and 12.72 ± 0.61 (n = 16). The differences between D166V and WT groups and between rescue-mice and D166V were statistically significant, with P < 0.01 (determined by ANOVA for repeated measurements) (Fig. 4C). Thus, D166V preparations displayed significantly increased levels of passive tension compared with WT, consistent with morphological assessments of D166V myocardium (Fig. 2 B and C). These abnormalities were not observed in Homo- or Hetero-rescue mice.

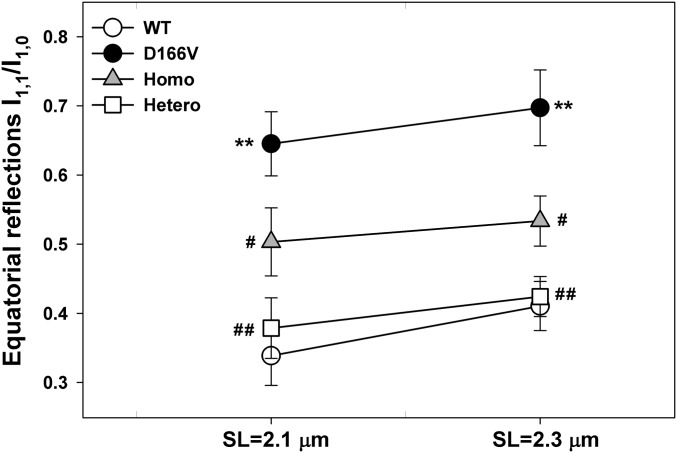

Sarcomeric Structure Assessed by Low-Angle X-Ray Diffraction Patterns in Skinned Papillary Muscle Fibers from WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-Rescue Mice.

To gain mechanistic insight into the HCM phenotype and the ability of RLC phosphorylation to prevent the development of disease in mice, we obtained small-angle X-ray diffraction patterns of freshly skinned papillary muscle strips from all mice. Male and female mice (5.4 ± 0.2-mo-old mice, six animals per group) were used. Table 3 summarizes the interfilament lattice spacing (d1,0 or IFS) determined from the distance between the 1,0 and 1,1 equatorial reflections. IFS depicts the center-to-center distance between adjacent thick filaments. Fig. 5 represents the cross-bridge mass distribution between the thick and thin filaments, as indicated by the ratio (I1,1/I1,0, ) of the intensity of the 1,1 to that of the 1,0 equatorial reflections (21). Both IFS and I1,1/I1,0 were significantly higher in D166V mice compared with WT. The larger values of IFS and I1,1/I1,0 measured in D166V vs. WT fibers under relaxation conditions were paralleled by the lower tension and a left-shifted force-pCa dependence monitored in contracting D166V vs. WT fibers (Fig. 4 A and B). This structure–function relationship observed in D166V mice reveals structural evidence for D166V mutation-mediated sensitization of the myofilaments to calcium as observed in functional studies (Fig. 4B). The greater I1,1/I1,0 in HCM vs. WT mice indicates repositioning of the D166V cross-bridges closer to actin, which may potentially result in premature activation of the thin filaments at a lower Ca2+ concentration (increased Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction). Interestingly, these abnormalities, and especially increased I1,1/I1,0, were partially or fully reversed by pseudophosphorylation of D166V fibers in Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice, respectively (Fig. 5). The reason that the I1,1/I1,0 ratio of Hetero-mice expressing ∼50% transgene lies closer to the WT could be due to 50% of WT cross-bridges that reside in the Hetero-mice assuming the same spatial orientation as the cross-bridges of WT mice.

Table 3.

Interfilament lattice spacing assessed in WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mouse papillary muscle fibers in relaxation

| Parameter | WT | D166V | Homo | Hetero |

| d1,0, nm | 41.71 ± 0.17 | 42.81 ± 0.27* | 41.97 ± 0.82 | 42.59 ± 0.33 |

| IFS, nm | 48.16 ± 0.20 | 49.43 ± 0.31* | 48.46 ± 0.95 | 49.18 ± 0.38 |

| No. of fibers (no. of shots) | 18 (76) | 7 (29) | 8 (29) | 14 (52) |

The distance between the 1,0 and 1,1 reflections was converted to the d1,0 lattice spacing using Bragg’s law and then converted to the interfilament spacing (IFS) by multiplying by 2/√3, IFS being the center-to-center distance between the thick filaments. Sarcomere length was 2.1 µm. Data are the average of n fibers ± SEM; *P = 0.002 for D166V vs. WT.

Fig. 5.

Equatorial reflections intensity ratio I1,1/I1,0 in skinned papillary muscle fibers from WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue mice in relaxation. The I1,1/I1,0 was established for sarcomere length (SL) = 2.1 and 2.3 µm. Note the increased I1,1/I1,0 in D166V vs. WT mice depicting mutation-induced changes in cross-bridge mass distribution, positioning them closer to the thin filaments. Pseudophosphorylation significantly reversed an abnormal cross-bridge arrangement in Homo- and Hetero-rescue mouse fibers. The number of X-rayed fibers (n) from WT, D166V, and Homo- and Hetero-rescue hearts were, respectively: for SL = 2.1 μm, n = 18, 18, 16 and 14; and for SL = 2.3 μm, n = 17, 17, 16, and 12. Errors are SEM. **P < 0.001 for D166V vs. WT and #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.001 for S15D-D166V vs. D166V.

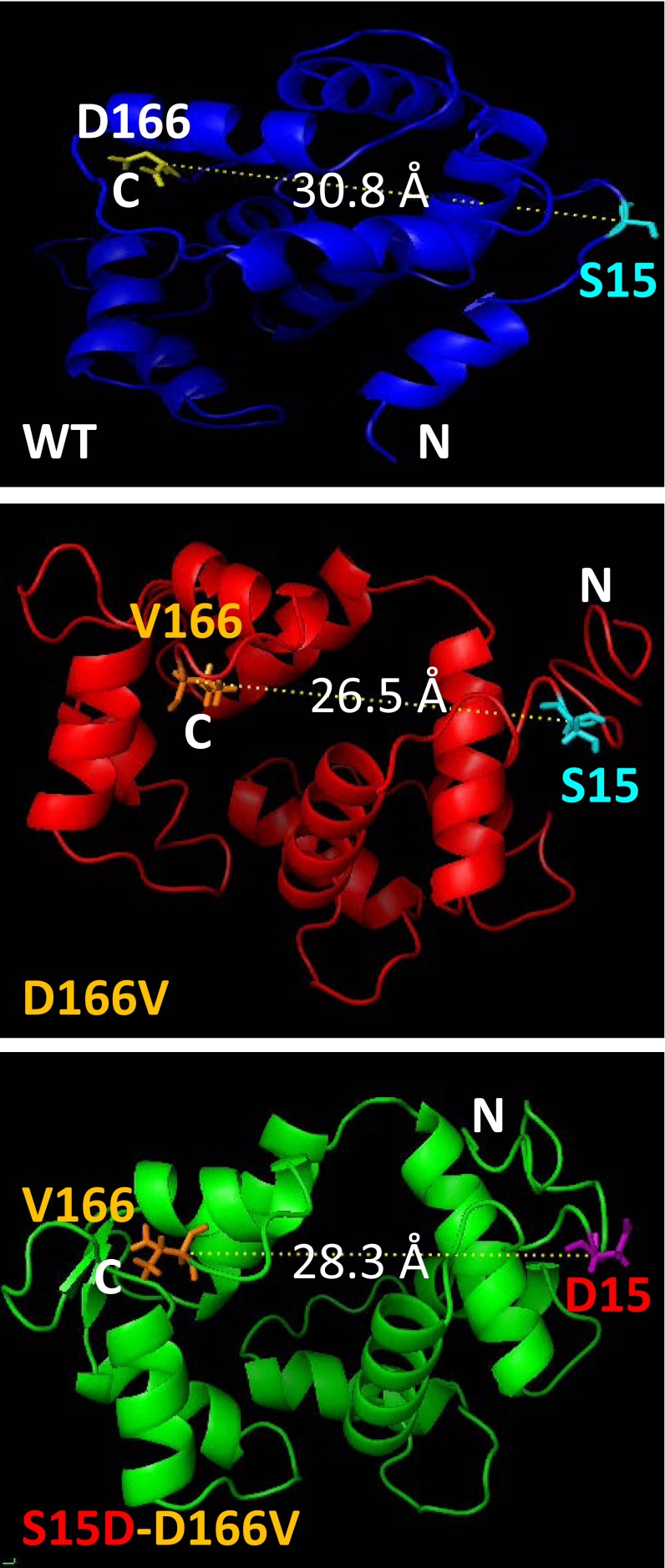

To further understand the mutation-induced molecular rearrangements, we pursued the secondary structure prediction of WT, D166V, and S15D-D166V proteins using I-TASSER software. The five lowest energy secondary structures of the human ventricular RLC were computed using protein templates similar to RLC structures and extracted from the Protein Data Bank library. The following PDB structures with high similarity to the structure of RLC were used (PDB ID code): 3jvtB [chain B, calcium-bound scallop myosin regulatory domain (lever arm) with reconstituted complete light chains], 1prwA (chain A, crystal structure of bovine brain Ca2+ calmodulin in a compact form), 4ik1A (chain A, high-resolution structure of Gcampj at pH 8.5), 2mysB (chain B, myosin subfragment 1), 4i2yA (chain A, crystal structure of the calcium indicator Rgeco1), and 4aqrA (chain A, crystal structure of calmodulin in complex with the regulatory domain of a plasma-membrane Ca2+-ATPase) (22). In all modeled structures, the RLC-like proteins were bound to their immediate binding partners, reflecting the assessment of the structural effects of mutation(s) under more physiological conditions.

The site of D166V mutation was predicted to be in close proximity to the N-terminal α-helical region of the RLC containing the MLCK-specific phosphorylation site at Ser15 (Fig. 6). The C-α distance between D166 and Ser15 residues observed in WT-RLC (30.8 Å) was decreased to 26.5 Å in D166V-RLC. Interestingly, in S15D-D166V, the C-α distance between D15 and V166 reached the median value of 28.3 Å. These subtle intermolecular rearrangements demonstrate the propensity of HCM-causing mutations to render significant structural changes (Fig. 5) that may ultimately affect the function of the mutated myocardium.

Fig. 6.

Modeled structure of the human ventricular RLC-WT, D166V, and S15D-D166V mutant proteins. Note the mutation-rendered changes in the C-α distance between the site of HCM mutation and the myosin RLC phosphorylation site at Serine15 (S15). The predicted structures of RLCs were based on PDB structures 3jvtB, 1prwA, 4ik1A, 2mysA, 4i2yA, and 2w4aB (SI Methods).

Discussion

HCM is defined as an autosomal dominant myocardial disease characterized by specific functional abnormalities, echocardiographic features, asymmetric septal hypertrophy, and disordered myocardial architecture. In this study, we examined, for the first time, to our knowledge, the myosin RLC phosphorylation-based rescue mechanism to abrogate or prevent the development of the HCM phenotype in transgenic mice expressing the pseudophosphorylated Ser15 (S15D) in the background of HCM-causing D166V-RLC mutation. In vivo and in vitro investigations on Tg-S15D-D166V-rescue mice provided strong evidence for significant improvement of the structural, functional, and morphologic phenotypes, which were largely compromised in HCM-D166V mice, by constitutive Ser15 phosphorylation.

The Mechanism of Heart Failure in D166V-HCM Mice.

Our published results on Tg-D166V mice suggested that a mutation-induced inhibition of RLC phosphorylation might underlie the mechanism of D166V-mediated development of HCM (5). Diminished RLC phosphorylation, observed in Tg-D166V hearts previously (5–7, 17) and in this study (Fig. 1B), seems to be independent of the expression of cardiac MLCK in D166V hearts because only slightly lower, and not significant from WT, expression of cMLCK (mRNA and protein) was observed in Tg-D166V vs. Tg-WT mice (Fig. 1 C and D). No phosphorylation of other sarcomeric protein-elicited compensatory mechanisms were noted in the hearts of HCM or rescue mice that could explain the functional differences between the phenotypes (Fig. 1 E and F). The inability of D166V-RLC to become phosphorylated led to reduced rates of cross-bridge cycling kinetics (7) and resulted in lower myofibrillar ATPase activity in D166V compared with WT heart preparations (Table 2). Typical for HCM, the D166V mutation also bestowed the hypersensitive Ca2+-dependent regulation of cardiac muscle contraction (Fig. 4B and Table 2). Structural evidence providing insight into these abnormal functional effects came from small-angle X-ray diffraction experiments that clearly demonstrated a mutation-sensitive cross-bridge mass distribution positioning them closer to the thin filaments and potentially allowing premature Ca2+ activation (Fig. 5). A mutation-induced increase in the distance between the thick and thin filaments (Table 3) was most likely responsible for the reduced maximal force in contracting skinned papillary muscle fibers from D166V-mice (Fig. 4A). The reciprocal relationship between the IFS and maximal tension generation observed in this study (Table 3 and Fig. 4A) would be predicted by the theoretical work of Williams et al. (23) and is in accord with the work of Colson et al., where a 1.6-nm decrease in d1,0 due to the MLCK-induced phosphorylation of the RLC in mouse trabeculae muscles produced an ∼64% increase in maximal Ca2+-activated tension (24). Thus, these structural changes in the sarcomere presumably rendered defective heart performance in D166V mice and led to systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction (Fig. 3 and Table 1). At the protein level, the aspartic acid-to-valine substitution could be seen as a trigger of intramolecular changes in the RLC molecule (Fig. 6) that might affect myosin load-dependent mechanochemistry and disrupt its force generation capability, ultimately reducing the power stroke and the strength of cardiac muscle contraction. We then hypothesized that these molecular defects due to the D166V mutation could be counterbalanced by myosin RLC phosphorylation capable of restoring myosin’s mechanical properties and fine-tuning myosin function.

Potential Mechanism of Rescue by Pseudophosphorylation of Myosin RLC.

Although much is known about the functional significance of myosin RLC phosphorylation in cardiac disease, the idea of RLC phosphorylation-induced prevention of an HCM phenotype has not been tested before. Structural studies implied that the negative charge associated with phosphorylation of the RLC can repel myosin heads away from the thick filament backbone toward actin (24). On the other hand, RLC phosphorylation was proposed to modify the mechanical properties of the myosin lever arm and its ability to control the step size of cardiac myosin and advancing the longer 8-nm step frequency compared with nonphosphorylated myosin (25). An RLC phosphorylation-elicited longer myosin working stroke would then lead to increased contractile force and power (26). We believe that this mechanism may underlie the pseudophosphorylation-induced prevention of the development of the D166V-HCM phenotype in transgenic S15D-D166V mice. Reversal of the D166V-induced reduction of myofibrillar ATPase activity and the maximal steady state force noted in Tg-S15D-D166V compared with Tg-D166V mice (Table 2 and Fig. 4A) indicate that pseudophosphorylation is capable of increasing myosin's force production capacity, possibly through favoring a longer cross-bridge step size (25). Pseudophosphorylation was therefore able to prevent the consequences of D166V mutation and reverse the reciprocal relationship between the disease-causing D166V mutation and myosin activation.

In conclusion, we demonstrated here that the HCM-linked D166V mutation-induced adverse changes at the level of protein, myofilament structure, and intact hearts were offset by constitutive D166V phosphorylation. The contractile function of D166V-mutated myocardium was restored by the Serine15-to-aspartic acid substitution. The S15D-D166V hearts did not develop hypertrophy and maintained normal systolic and diastolic performance. More studies are needed to fully understand the mechanism by which myosin RLC phosphorylation is able to counterbalance a progressive HCM phenotype. This study may constitute a small-molecule therapeutic approach capable of correcting a mutation-induced inhibitory conformation of the RLC unable to become phosphorylated in the HCM hearts.

Methods

Detailed materials and methods are outlined in SI Methods.

Generation and Characterization of Transgenic S15D-D166V Mice.

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines. The University of Miami has an Animal Welfare Assurance (A-3224–01, effective November 23, 2011) on file with the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW), National Institutes of Health. Three lines of Tg-S15D-D166V mice were generated using protocols described earlier (18). The α-MHC–driven expression of the human ventricular S15D-D166V-RLC mutant in mouse hearts was assessed on the basis of the faster SDS/PAGE gel mobility of the human ventricular RLC (18.789 kDa) vs. mouse atrial RLC (19.450 kDa) as described previously (5, 27). RLC phosphorylation was detected in mouse purified myosin from the right and left ventricles of ∼5-mo-old mice with phospho-specific RLC antibodies (produced in this laboratory), which recognize the phosphorylated form of the RLC (27), followed by a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with IR red 800. The total RLC protein was detected with CT-1 and served as a loading control (18). The expression of Mylk3 (gene ID 213435) encoding the mouse cMLCK was assessed in three to four hearts per group by quantitative (qPCR) as described in ref. 27, and at the level of protein using a cMLCK-specific antibody (16).

For histological assessment, ∼5- and ∼9-mo-old Tg-S15D-D166V, Tg-D166V, and Tg-WT mice were used. The paraffin-embedded longitudinal sections of the hearts stained with H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) and Masson’s trichrome were examined for overall morphology and fibrosis (27). For transmission EM imaging, the hearts were fixed with 2% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, and the left ventricles were sectioned longitudinally for imaging as described earlier (27).

In Vivo Assessment of Cardiac Function.

The development of the HCM phenotype in Tg-D166V mice and its reversal in Tg-S15D-D166V animals were monitored using a Vevo-770 image system (28) using female and male S15D-D166V, D166V, and WT mice (Table 1). For invasive hemodynamics studies, the pressure-volume (P-V) loops were recorded at steady state and during vena cava inferior occlusions (28).

Contractile Force Assessment.

The ATPase assays on cardiac myofibrils from the right and left ventricles of ∼5-mo-old mice were performed as described previously (12). The papillary muscles of the left ventricles from Tg mice were subjected to force measurements, and the force-pCa curves were determined (27). The measurement of passive force (in pCa 8 solution) in response to muscle stretch was performed as described in Kazmierczak et al. (28).

X-Ray Diffraction Measurements in Skinned Papillary Muscle Fibers.

The equatorial X-ray diffraction patterns were collected from freshly skinned Tg papillary muscle strips using a small-angle instrument on the BioCAT beamline 18ID (Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory). The distance between the 1,0 and 1,1 reflections allowed the assessment of the interfilament lattice spacing (21). Intensities of the 1,0 and 1,1 reflections were determined from nonlinear least square fits to 1D intensity projections along the equator.

SI Methods

Generation of Transgenic S15D-D166V Mice.

Tg-S15D-D166V mice were generated as described earlier for transgenic Tg-WT (18) and Tg-D166V (5) mice. Multiple crosses with B6SJL/F1 mice were performed before the animals were used in experiments. The results were obtained on 5- to 6-mo-old and 9- to 10-mo-old double mutant mice (two lines) of both sexes and compared with those obtained for age- and sex-matched WT or D166V mice. About 45 mice per group, for a total of 180 animals, were used in this study.

Analysis of Transgenic Protein Expression.

The α-MHC (myosin heavy chain)–driven expression of the human ventricular S15D-D166V-RLC mutant in mouse hearts was assessed on the basis of the faster SDS/PAGE gel mobility of the human ventricular RLC (18.789 kDa) vs. mouse atrial RLC (19.450 kDa) as described previously (5, 27). The transgenic protein was detected using a rabbit polyclonal RLC CT-1 antibody produced previously (18), followed by a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with the fluorescent dye, IR red 800. The myosin essential light chain (ELC) was used as a loading control and detected with the monoclonal ab680 antibody (Abcam) (27).

Analysis of RLC Phosphorylation, cMLCK Expression, and Phosphorylation of MyBP-C and TnI.

RLC phosphorylation was detected in mouse purified myosin from the right and left ventricles of ∼5-mo-old mice with a phospho-specific RLC antibody (produced in this laboratory), which recognizes the phosphorylated form of the RLC and does not react with nonphosphorylated RLC (22, 27), followed by a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with IR red 800. Total RLC protein was detected with the CT-1 antibody, which served as a loading control (18). The expression of Mylk3 (gene ID 213435) encoding the mouse cardiac MLCK was assessed in three to four hearts per group by quantitative PCR, conducted using SYBR Green I chemistry and a Bio-Rad iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system, as described in ref. 27. Raw data were analyzed using the Bio-Rad CFX manager software, and fold change (FC) in expression was calculated using the relative quantification (RQ) ΔΔCt method, with the levels of GAPDH as the normalizer gene (27). In addition, cMLCK protein expression and phosphorylation of myosin binding protein C (MyBP-C) and Troponin I (TnI) were tested in heart lysates from ∼5-mo-old mice from all groups. Briefly, small pieces of LV tissue were homogenized in CHAPS {3-[(3-cholamidopropyl) dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate} buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, and 0.5% CHAPS with 5 nM microcystin, phosphatase inhibitors (phosphatase inhibitor mixture 2 and 3; Sigma) and 1 µL/mL protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Protein concentration was determined using Coomassie Plus reagent (Pierce). Homogenates were dissolved in Laemmli buffer composed of 62.5 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.8, 25% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.01% Bromophenol blue and 5% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol (BME). Western blotting was performed by SDS/PAGE using 10% (wt/vol) (for MyBP-C), 12% (wt/vol) (cMLCK), and 15% (wt/vol) (TnI) PA (polyacrylamide) gels, and 5 µg (cMLCK) or 20 µg (MyBP-C, TnI) of protein per lane. The following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for phosphorylated MyBP-C at Ser282 and Ser302 (provided by Sakthivel Sadayappan, Loyola University, Chicago, IL) (29), cMLCK (provided by James Stull and Audrey Chang, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) (16), or phosphorylated Ser23/24 -TnI (Mab14 MMS-418R; Covance). Membranes were also probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to detect total MyBP-C (K-16 sc-50115; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or TnI (6F9; Research Diagnostics Inc.). A goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with the fluorescent dye, IR red 800, goat anti-mouse antibody conjugated with fluorescent Cy 5.5, and donkey anti-goat antibody conjugated with IR red 800 were used as secondary antibodies. The RLC (probed with CT-1) and GAPDH (ab9485; Abcam) proteins were used as loading controls. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software (imageJ.en.softonic.com) (22).

Histopathology and Electron Microscopy.

For histological assessment of heart morphology, two age groups (∼5- and ∼9-mo-old) of Tg-S15D-D166V, Tg-D166V, and Tg-WT mice (three to four mice per group) were used. The paraffin-embedded longitudinal sections of the hearts stained with H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) and Masson’s trichrome were examined for overall morphology and fibrosis using a Dialux20 microscope, ×40/0.65 N.A. (numerical aperture) Leitz Wetzlar objective and an AxioCam HRc camera (Zeiss) as described previously (27). Transmission EM imaging was conducted in the EM Core Facility at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. The hearts of 5- to 7-mo-old mice were fixed with 2% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, and the left ventricles were sectioned longitudinally for imaging as described previously (27). The slides were examined using a Philips CM-10 electron microscope at 10,500× magnification.

In Vivo Assessment of Cardiac Function by Echocardiography and Invasive Hemodynamics.

The development of the HCM phenotype in Tg-D166V mice and its reversal in Tg-S15D-D166V animals were monitored using a Vevo-770 image system equipped with a 17.5-MHz transducer, as described previously (28). Female and male Tg-S15D-D166V, Tg-D166V, and Tg-WT mice at 5.5 ± 0.2 mo of age were used (Table 1). The M-mode and B-mode images were analyzed for cardiac morphology and function using the Vevo 770 3.0.0 software (VisualSonics). Determined parameters included the following: left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic and end-systolic dimensions, LV posterior wall (LVPW), and interventricular septum (IVS) thickness, LVmass/body weight (BW), and ejection fraction (EF). For invasive hemodynamics studies, a catheter transducer (SPR-839; Millar Instrument) was introduced into the left ventricle through the right carotid. Pressure-volume (P-V) loops were recorded at steady state and during vena cava inferior occlusions (28). Parameters determined included the peak rate of rise in LV pressure dP/dtmax-end-diastolic volume (EDV) relation, preload recruited stroke work (PRSW), and the slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR). Diastolic performance was measured by the time constant of ventricular relaxation (Tau). Data were analyzed using LabChart7 Pro v7.2 software (ADInstruments).

Functional Assessment of Transgenic Cardiac Muscle Preparations in Vitro Myofibrillar ATPase Activity.

Cardiac myofibrils (CMFs) were prepared from the right and left ventricles of ∼5-mo-old mice of both sexes and subjected to ATPase assays as described previously (12). The assay was performed in 96-well microplates containing 20 µg of CMF per well in a solution containing 20 mM Mops (pH 7.0), 40 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, and increasing concentrations of Ca2+ from 10−8 M to 10−4 M (30). After 5 min of incubation at 30 °C, the reaction was initiated with 2.5 mM ATP and terminated after 10 min with 5% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid. Released inorganic phosphate (Pi) was measured using the Fiske and Subbarow method (31).

Skinned Papillary Muscle Fibers from Transgenic Mice.

The papillary muscles of the left ventricles from 4.5- to 6.5-mo-old male and female Tg mice were isolated, dissected into muscle bundles in the buffer containing pCa 8 solution {10−8 M [Ca2+], 1 mM free [Mg2+] [total MgPr (propionate) =3.88 mM], 7 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM [Mg-ATP2-], 20 mM Mops, pH 7.0, 15 mM creatine phosphate, and 15 units/mL phosphocreatine kinase, ionic strength = 150 mM adjusted with KPr}, 15% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 30 mM BDM. Muscle bundles were then skinned in 50% pCa 8 solution and 50% glycerol containing 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 24 h at 4 °C. Muscle bundles were then transferred to the same solution without Triton X-100 and stored at −20 °C for experimentation within ∼5 d (27).

Steady-State Force Development.

Small muscle strips of ∼1.4 mm in length and 100 μm in diameter were isolated from a batch of glycerinated skinned mouse papillary muscle bundles and attached to a Guth force transducer for force measurements (27). The sarcomere length was adjusted to ∼2.1 μm (32), and the maximal steady state force was measured in pCa 4 solution (composition is the same as pCa 8 buffer except the [Ca2+]=10−4 M) and expressed in kN/m2. The Ca2+ dependence of force development was determined in solutions of increasing Ca2+ concentrations from pCa 8 to pCa 4. The force-pCa curves were analyzed using the Hill equation, yielding the pCa50 (midpoint of the force-pCa relation) and nH (Hill coefficient) (33).

Passive Force Measurements.

The measurement of passive force (in pCa 8 solution) in response to muscle stretch was performed as described in Kazmierczak et al. (28). The strip was first released and stretched until it began generating tension. This point was set as zero for both the passive force and starting length of the muscle strip. Then the strip was stretched by 10% of its length times four consecutive times, and the passive force per cross-section of muscle (in kN/m2) was determined.

X-Ray Diffraction Measurements in Skinned Papillary Muscle Fibers.

The equatorial X-ray diffraction patterns were collected from freshly skinned Tg papillary muscle strips and mounted in a simple Plexiglas X-ray chamber in pCa 8 solution using the small-angle instrument on the BioCAT beamline 18-D at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory). Sarcomere length was adjusted to 2.1 µm using a light microscope and a digital image analysis system as described earlier (21). Equatorial small-angle X-ray diffraction patterns were collected on a CCD-based X-ray detector (Mar 165; Rayonix Inc.) The distance between the 1,0 and 1,1 reflections was converted to the d1,0 lattice spacing using Bragg’s law and then converted to the interfilament spacing (IFS) by multiplying by 2/√3, IFS being the center-to-center distance between the thick filaments (21). Intensities of the 1,0 and 1,1 equatorial reflections were determined from nonlinear least square fits to 1-dimensional projections of the integrated intensity along the equator. All data were analyzed independently by three people, and the results were averaged (21).

Secondary Structure Prediction.

The secondary structure prediction of WT, D166V, and S15D-D166V proteins was conducted using I-TASSER software (online server, University of Michigan, zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) (34–36). The five lowest energy secondary structures of human ventricular RLC were computed using protein templates similar to the RLC structures and extracted from the Protein Data Bank library: 3jvtB, 1prwA, 4ik1A, 2mysA, 4i2yA, 2w4aB, and 4aqrA (see Results for explanation of protein structures) (22). The full-length protein was assembled from the excised fragments and simulated into the lowest energy model, and the confidence of each predicted structure was presented as a C score, ranging from −5 to 2. The quality of the prediction was proportional to the value of the C score (34–36). The predicted structures were then modeled using the PyMOL (www.pymol.org) molecular visualization system to allow determination of the C-α distances (Å) between neighboring amino acid residues.

Statistical Analysis.

All values are shown as means ± SEM. Statistically significant differences between two groups were determined using an unpaired Student’s t test, with significance defined as P < 0.05. Comparisons between multiple groups were performed using One Way ANOVA (Sigma Plot 11; Systat Software).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. James Stull, Audrey Chang, and Sakthivel Sadayappan for the gift of cMLCK and phospho-MyBP-C antibodies. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-HL-071778 and HL-108343 (to D.S.-C.) and HL-107110 (to J.M.H.) and by American Heart Association Grants 15PRE23020006 (to C.-C.Y.), 10POST3420009 (to P.M.), and 12PRE12030412 (to W.H.). Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the US DOE under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. BioCAT is an NIH-supported research center (9 P41 GM103622).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 9148.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1505819112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Alcalai R, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Genetic basis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: From bench to the clinics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2008;19(1):104–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho CY. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart Fail Clin. 2010;6(2):141–159. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho CY, et al. Myocardial fibrosis as an early manifestation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):552–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richard P, et al. EUROGENE Heart Failure Project 2003. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation 107(17):2227–2232, and erratum (2004) 109(25):3258.

- 5.Kerrick WG, Kazmierczak K, Xu Y, Wang Y, Szczesna-Cordary D. Malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy D166V mutation in the ventricular myosin regulatory light chain causes profound effects in skinned and intact papillary muscle fibers from transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2009;23(3):855–865. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-118182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muthu P, Kazmierczak K, Jones M, Szczesna-Cordary D. The effect of myosin RLC phosphorylation in normal and cardiomyopathic mouse hearts. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(4):911–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muthu P, et al. Single molecule kinetics in the familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy D166V mutant mouse heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48(5):989–998. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szczesna D. Regulatory light chains of striated muscle myosin: Structure, function and malfunction. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2003;3(2):187–197. doi: 10.2174/1568006033481474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamm KE, Stull JT. Signaling to myosin regulatory light chain in sarcomeres. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(12):9941–9947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.198697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Velden J, et al. The effect of myosin light chain 2 dephosphorylation on Ca2+-sensitivity of force is enhanced in failing human hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57(2):505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Velden J, et al. Increased Ca2+-sensitivity of the contractile apparatus in end-stage human heart failure results from altered phosphorylation of contractile proteins. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57(1):37–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00606-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham TP, et al. Diastolic dysfunction in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy transgenic model mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82(1):84–92. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scruggs SB, et al. Ablation of ventricular myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation in mice causes cardiac dysfunction in situ and affects neighboring myofilament protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(8):5097–5106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807414200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheikh F, et al. Mouse and computational models link Mlc2v dephosphorylation to altered myosin kinetics in early cardiac disease. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(4):1209–1221. doi: 10.1172/JCI61134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding P, et al. Cardiac myosin light chain kinase is necessary for myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation and cardiac performance in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(52):40819–40829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang AN, et al. Constitutive phosphorylation of cardiac Myosin regulatory light chain in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(17):10703–10716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.642165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muthu P, Liang J, Schmidt W, Moore JR, Szczesna-Cordary D. In vitro rescue study of a malignant familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotype by pseudo-phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chain. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;552-553:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, et al. Prolonged Ca2+ and force transients in myosin RLC transgenic mouse fibers expressing malignant and benign FHC mutations. J Mol Biol. 2006;361(2):286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afonso LC, Bernal J, Bax JJ, Abraham TP. Echocardiography in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the role of conventional and emerging technologies. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1(6):787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carasso S, et al. Systolic myocardial mechanics in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Novel concepts and implications for clinical status. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21(6):675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthu P, et al. Structural and functional aspects of the myosin essential light chain in cardiac muscle contraction. FASEB J. 2011;25(12):4394–4405. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-191973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang W, et al. Novel familial dilated cardiomyopathy mutation in MYL2 affects the structure and function of myosin regulatory light chain. FEBS J. 2015;2015(Mar):30. doi: 10.1111/febs.13286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams CD, Salcedo MK, Irving TC, Regnier M, Daniel TL. The length-tension curve in muscle depends on lattice spacing. Proc Biol Sci. 2013;280(1766):20130697. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colson BA, et al. Differential roles of regulatory light chain and myosin binding protein-C phosphorylations in the modulation of cardiac force development. J Physiol. 2010;588(Pt 6):981–993. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Ajtai K, Burghardt TP. Ventricular myosin modifies in vitro step-size when phosphorylated. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;72:231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller MS, et al. Regulatory light chain phosphorylation and N-terminal extension increase cross-bridge binding and power output in Drosophila at in vivo myofilament lattice spacing. Biophys J. 2011;100(7):1737–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang W, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated Lys104Glu mutation in the myosin regulatory light chain causes diastolic disturbance in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;74:318–329. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazmierczak K, et al. Discrete effects of A57G-myosin essential light chain mutation associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305(4):H575–H589. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00107.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barefield D, Kumar M, de Tombe PP, Sadayappan S. Contractile dysfunction in a mouse model expressing a heterozygous MYBPC3 mutation associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306(6):H807–H815. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00913.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dweck D, Reyes-Alfonso A, Jr, Potter JD. Expanding the range of free calcium regulation in biological solutions. Anal Biochem. 2005;347(2):303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiske CH, Subbarow Y. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. J Biol Chem. 1925;66:375–400. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Muthu P, Szczesna-Cordary D, Kawai M. Characterizations of myosin essential light chain’s N-terminal truncation mutant Δ43 in transgenic mouse papillary muscles by using tension transients in response to sinusoidal length alterations. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2013;34(2):93–105. doi: 10.1007/s10974-013-9337-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hill TL, Eisenberg E, Greene L. Theoretical model for the cooperative equilibrium binding of myosin subfragment 1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77(6):3186–3190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: A unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc. 2010;5(4):725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy A, Yang J, Zhang Y. COFACTOR: An accurate comparative algorithm for structure-based protein function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Web Server issue):W471–W477. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]