The current data on systemic treatment options for patients with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma are reviewed, with recommendations for their use in everyday practice. Patients with MALT lymphoma should be treated within prospective trials to further define optimal therapeutic strategies. Systemic treatment is a reasonable option with potentially curative intent in everyday practice.

Keywords: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, Systemic treatment, Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma, Rituximab, Chemotherapy, Indolent lymphoma

Abstract

Background.

Biological treatments, chemoimmunotherapy, and radiotherapy are associated with excellent disease control in both gastric and extragastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas. Systemic treatment approaches with both oral and i.v. agents are being increasingly studied, not only for patients with disseminated MALT lymphoma, but also for those with localized disease. To date, however, recommendations for the use of available systemic modalities have not been clearly defined.

Materials and Methods.

The present report reviews the current data on systemic treatment options for patients with MALT lymphoma and provides recommendations for their use in everyday practice.

Results.

Different chemotherapeutic agents, including anthracyclines, alkylators, and purine analogs, have been successfully tested in patients with MALT lymphoma. Reducing side effects while maintaining efficacy should be the main goal in treating these indolent lymphomas. From the data from the largest trial performed to date, the combination of chlorambucil plus rituximab (R) appears to be active as first-line treatment. Similarly, R-bendamustine also seems to be highly effective, but a longer follow-up period is needed. R-monotherapy results in lower remission rates, but seems a suitable option for less fit patients. New immunotherapeutic agents such as lenalidomide (with or without rituximab) or clarithromycin show solid activity but have not yet been validated in larger collectives.

Conclusion.

Patients with MALT lymphoma should be treated within prospective trials to further define optimal therapeutic strategies. Systemic treatment is a reasonable option with potentially curative intent in everyday practice. Based on the efficacy and safety data from available studies, the present review provides recommendations for the use of systemic strategies.

Implications for Practice:

In view of the biology of MALT lymphoma with trafficking of cells within various mucosal structures, systemic treatment strategies are increasingly being used not only in advanced but also localized MALT lymphoma. In the past, different chemotherapeutic agents, including anthracyclines, alkylators, and purine analogs, have been tested successfully. However, modern regimens concentrate on reducing side effects because of the indolent nature of this distinct disease. As outlined in this review and based on recent data, chlorambucil plus rituximab (R) may be considered one standard treatment within this setting. In addition, R-bendamustine seems to be a very promising combination. According to recent trends, however, “chemo-free” approaches (i.e., antibiotics with immunomodulatory effects [clarithromycin]) or other immunotherapies (lenalidomide ±R) may be important therapeutic approaches in the near future.

Introduction

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) is characterized by unique clinicopathological properties [1]. Initially described as a gastric disease related to infection with Helicobacter pylori (HP) [2], it is now apparent that MALT lymphoma can arise in virtually every tissue of the human body. The characteristics of the disease have led to the use of antibiotics as first-line treatment in gastric, as well as ocular adnexal, MALT lymphomas. Given the impressive results in gastric MALT lymphoma, HP eradication is now the worldwide accepted, standard therapy, resulting in durable responses in up to 80% of patients [3]. Also, antibiotic therapy is a reasonable first-line approach in patients with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma [4–6]. Likewise, evidence supporting antiviral treatment in patients with hepatitis C virus-related MALT lymphomas is increasing [7].

In patients with relapsing or disseminated MALT lymphomas, however, different treatment approaches have been used. Although localized disease has historically been—and still is—preferentially treated using radiotherapy in most centers [8–10], chemotherapy had only been given in advanced or refractory disease [11–14]. Recent years, however, have seen a trend toward an increased use of systemic treatment approaches, irrespective of disease stage. Different drugs and combinations have been used in mostly smaller studies; however, the indications for a potential standard regimen outside of clinical trials remain unclear. The objective of the present review therefore was to sum the current evidence on systemic therapies in patients with MALT lymphoma, providing some recommendations for their use in everyday practice.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a computerized search in MEDLINE to identify current publications on systemic treatment with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and/or combined regimens for histologically verified gastric and extragastric MALT lymphoma. Included were only full-text publications written in English; thus, we cannot exclude a bias resulting from nonprovided or nontranslated abstracts and reports with only the abstract but not the full text available online. Single case reports or case series consisting of fewer than 5 patients were excluded, as were trials of indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas or marginal zone lymphomas in general, without a subgroup analysis for MALT lymphoma. Retrospective analyses without detailed information on the regimen and reports on several therapy regimens without data or analyses on the specific treatment arms were also excluded.

The following data were extracted from matching reports if available: study design; number of patients included; localization of MALT lymphoma (gastric or extragastric), including stage; basic characteristics of study population; exact treatment plan and dosing; toxicities; overall response rate (ORR), detailed responses (i.e., complete remission [CR], partial remission [PR], stable disease [SD], and progressive disease [PD]), and ORR of gastric versus extragastric MALT lymphoma, if applicable; consecutive relapses; progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and follow-up period (FUP). The responses as stated by the respective investigators were used for further interpretation and the overall response rate was defined as the number or percentage of patients achieving CR and PR.

We made no attempts to discover unpublished data. In addition to the computerized search in MEDLINE, a manual search of the reference sections of the reports included in the analysis was performed.

Results

Chemotherapy-Containing Regimens for the Treatment of MALT Lymphoma

Data on the application of “classic” chemotherapeutic agents date back to the early 1990s. However, these data might have been biased because only patients with advanced disease received chemotherapy. With few exceptions, patients with localized MALT lymphoma were almost exclusively treated with surgery or radiotherapy. Only more recently have researchers included patients with limited-stage disease in clinical trials addressing systemic therapies. Detailed results of the respective studies, including the exact dosing, side effects, and relapse rates are reported in Tables 1 and 2.

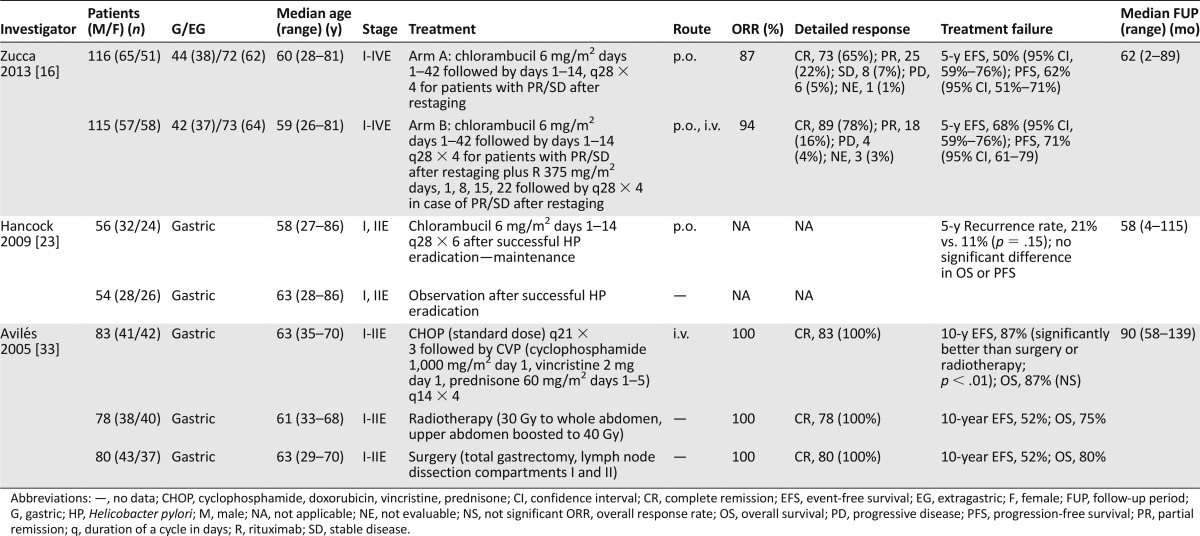

Table 1.

Randomized trials in MALT lymphoma

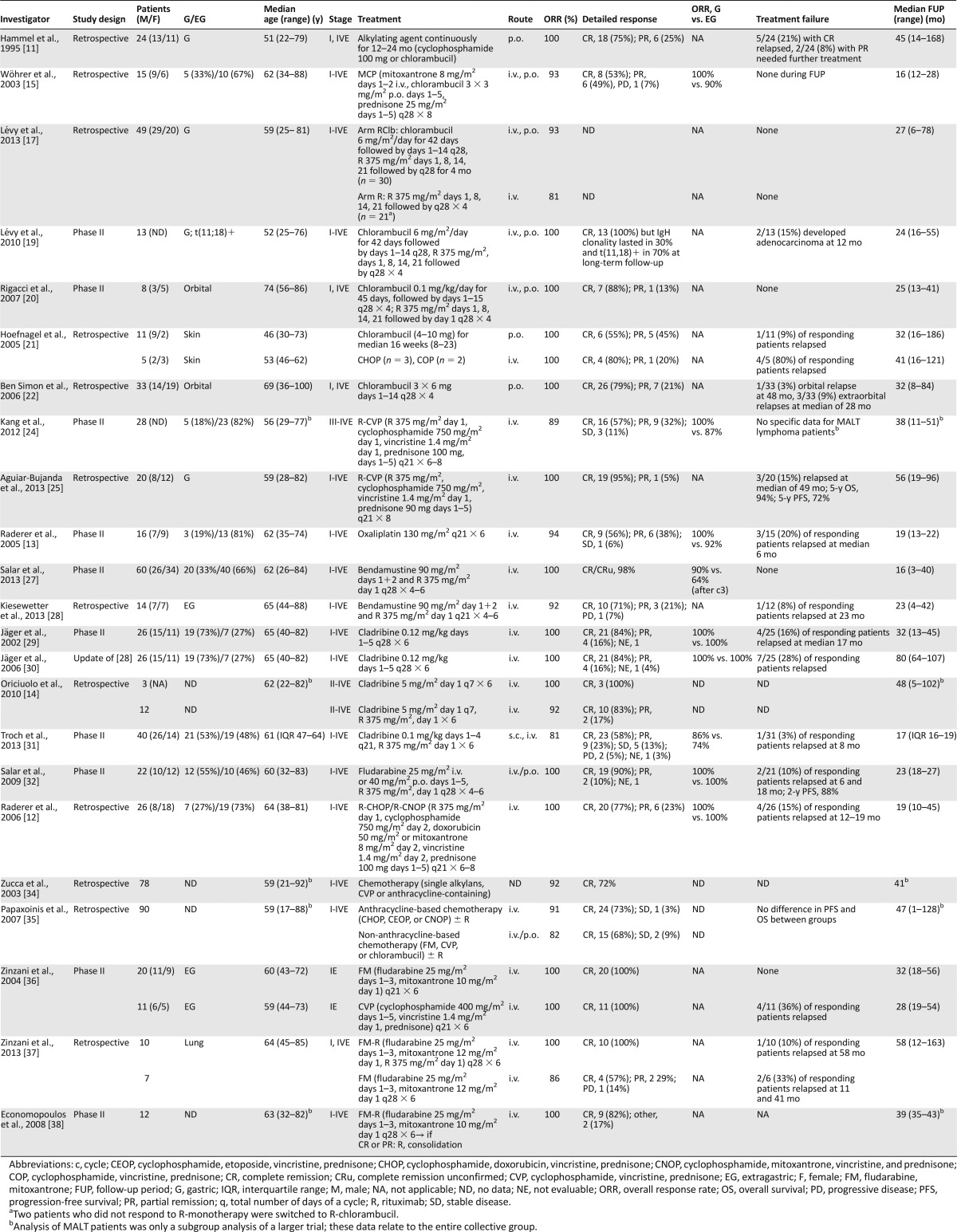

Table 2.

Chemotherapy-containing regimens for MALT lymphoma

Alkylating Agents

Hammel et al. [11] used either chlorambucil or cyclophosphamide in 24 patients with MALT lymphoma (17 stage I, 7 stage IV). The complete remission rate (CRR) was 75% after a median treatment duration of 12 months; 6 patients stopped therapy after 24 months in PR.

Since then, alkylating agents, in particular, chlorambucil, are probably the most extensively studied agents in MALT lymphoma. Chlorambucil has been tested alone or, more recently, in combination. Chlorambucil was combined with mitoxantrone and prednisone in a retrospective series of 15 patients resulting in a 93% ORR and 53% CRR [15]. An increasing interest in the combination of chlorambucil with rituximab (R) led to the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG-19) study, the largest randomized trial in MALT lymphoma [16]. A total of 231 patients were included to compare chlorambucil versus R-chlorambucil. Chlorambucil was given at 6 mg/m2 for 42 consecutive days (weeks 1–6), followed by chlorambucil for 2 weeks every 4 weeks (1 cycle) for up to 4 cycles for patients with SD or PR after restaging. The ORR rate was 87% for chlorambucil and 94% for the combination (p = .069). The CRR was significantly higher with the combination (78% vs. 65%, p = .025), in both gastric and extragastric forms. The 5-year event-free survival was significantly better for R-chlorambucil (68% vs. 50%), resulting in a risk reduction for events (hazard ratio [HR], 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34–0.79). Toxicity was mild, with grade III/IV neutropenia <5% in the chlorambucil arm and 14% in the combination arm, with no treatment-related deaths. However, OS was not significantly improved. Consequently, the study was amended to include an R-monotherapy arm for further comparison of R- and chlorambucil monotherapies; definitive results will be available in the next years.

A smaller prospective trial [17] compared R-chlorambucil with R-monotherapy in 49 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma refractory to HP eradication or not associated with HP infection. Responses after 25 weeks of treatment were 81% for R-monotherapy and 93% for the combination arm. No patient experienced progressive disease after a median follow-up (FUP) of 24 months. In that trial, the response rate was correlated with t(11;18)(q21;q21) status, which has been shown to be a negative predictor for the response to HP eradication [18]. R-chlorambucil was associated with a higher ORR compared with R-monotherapy, irrespective of t(11;18)(q21;q21) status, which has been confirmed by another small (n = 13) prospective study [17, 19]. In addition, several smaller studies using chlorambucil in MALT lymphomas of different extranodal sites have been published (Tables 1 and 2) [20, 21].

A retrospective analysis of 33 patients with newly diagnosed stage IE orbital MALT lymphoma treated with chlorambucil reported a 100% ORR (CRR, 79%) with only 1 local relapse (3%) at a median FUP of 48 months, and a 9% rate of extraorbital relapse, suggesting solid activity with low toxicity in orbital MALT lymphoma [22].

Chlorambucil has been also used after HP eradication in gastric MALT lymphoma in a study randomizing 110 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma responding to HP eradication between “wait and see” and chlorambucil maintenance [23]. The 5-year recurrence rate was low in both arms (21% in the observation and 11% in the chlorambucil arm; p = .15). No benefit was observed with the addition of chlorambucil, neither in patients in CR after initial HP eradication nor in patients with lymphoma remnants after initial antibiotic therapy, suggesting that patients with residual gastric disease after antibiotic therapy should not receive maintenance/consolidative alkylating agents.

R-cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) has been historically used as an alternative to R-cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) in “unfit” patients and has been reported as an effective first-line treatment in a phase II trial of advanced-stage marginal zone lymphoma in a subgroup analysis of 28 patients [24]. This is in line with recent retrospective data from 20 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma [25]. The ORR with R-CVP was high, but neutropenia and polyneuropathy were relatively frequent, limiting its use in elderly patients.

The alkylating DACH-platinum oxaliplatin has been analyzed in a prospective phase II study on 16 patients, with a 94% ORR and 56% CRR [13]. However, this agent does not seem a reasonable choice for upfront treatment of MALT lymphoma, because early relapses (3 at a median of 6 months) and a high prevalence of neuropathy were noted.

Summary

According to published evidence, the combination chlorambucil plus R is active as first-line treatment for patients with disseminated MALT lymphoma or with limited-stage MALT lymphoma relapsing after local treatment or antibiotics. This is a suitable combination for elderly patients, both with gastric or extragastric forms and is efficacious irrespective of t(11;18)(q21;q21) status.

According to published evidence, the combination chlorambucil plus R is active as first-line treatment for patients with disseminated MALT lymphoma or with limited-stage MALT lymphoma relapsing after local treatment or antibiotics.

Bendamustine

In addition to classic alkylators, bendamustine (B) has seen a revival in the treatment of lymphomas, and the combination with R (R-B) has recently been validated as equally effective to R-CHOP in the first-line treatment of indolent and mantle cell lymphomas [26]. Promising data from a Spanish nation-wide phase II trial were recently reported in abstract form [27]. Sixty untreated patients with MALT lymphoma were given R at 375 mg/m2 on day 1 plus bendamustine 90 mg/m2 on days 1 and 2, every 28 days, for 4 or 6 cycles according to the response after the third course. All patients responded, and after a median FUP of 16 months (range, 3–40), no relapses have occurred. Toxicity was mild, with only 5 patients requiring a dose reduction of bendamustine and 18% experiencing grade III/IV neutropenia. Interestingly, the responses after 3 cycles were higher in gastric lymphoma, and after a maximum of 6 courses, an equal response rate was achieved both in gastric and extragastric MALT lymphoma, suggesting that nongastric MALT lymphomas might require longer therapy.

A recent retrospective analysis of 14 patients with extragastric MALT lymphoma managed with R-B after relapse, including 4, with at least 2 previous treatment lines, suggested a high activity also in this pretreated cohort of patients (ORR, 92%; CRR, 71%) [28]. After a median FUP of 23 months (range, 4–42), only 1 patient experienced relapse, and all patients but 1 were alive.

Summary

R-B seems to be highly effective and well tolerated in both newly diagnosed and previously untreated MALT lymphomas. Preliminary data have suggested that extragastric MALT lymphoma probably needs six courses for optimal activity.

Purine Analogs

The purine analogs cladribine and fludarabine are active drugs in both gastric and extragastric MALT lymphomas, with ORRs ranging from 80% to 100%. Jäger et al. [29] reported a phase II study of 26 patients (gastric, 73%; extragastric, 27%) treated with 6 cycles of cladribine monotherapy (0.12 mg/kg i.v. on days 1–5, every 28 days). The ORR was 100%, with an 84% CRR, the latter being higher in gastric than extragastric forms (100% vs. 43%). Updated results of that study [30] have reported a relapse rate of only 27% and no lymphoma-related deaths at a median FUP of 80 months (range, 64–107).

The combination of cladribine with R has been tested in two studies. A retrospective analysis on marginal zone lymphoma, including 12 MALT lymphoma patients, has shown a 92% ORR [14] and, more recently, a multicenter Austrian phase II trial of 40 assessable patients (gastric, 53%; extragastric, 48%) showed an 81% ORR (CRR, 58%), and only 2 patients developed progression during therapy [31]. In contrast to trials reporting on cladribine monotherapy, the combination with R seemed to be more toxic, because nearly 30% of patients experienced leukopenia grade III/IV, and 2 patients had prolonged pancytopenia. ORR has been similar in gastric and extragastric forms and equally distributed between patients with localized and disseminated disease. When interpreting these data, however, one should bear in mind that the overall dose of cladribine was higher at 0.12 mg/kg on days 1–5 compared with 0.1 mg/kg i.v. on days 1–4 in the latter series, which might explain the different outcomes. Still, the initial data with a median FUP of >6 years render cladribine one of the most effective monotherapies published to date [30].

Fludarabine 25 mg/m2 i.v. or 40 mg p.o. on days 1–5 in combination with R has been highly active (ORR, 100%; CRR, 90%) in 22 patients with newly diagnosed MALT lymphoma [32]. However, hematologic side effects were a major issue in that study, because more than 30% of patients experienced grade III/IV neutropenia.

Summary

Purine analogs (also combined with R) are a highly active option for patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed MALT lymphoma. Owing to hematological toxicity, these drugs should be kept for younger patients, mostly as first-line treatment. Recently, these drugs have been progressively replaced by bendamustine in patients with MALT lymphoma.

Anthracyclines

In 2005, Avilés et al. [33] were the first to publish data comparing surgery (n = 80), radiotherapy (n = 78), or chemotherapy (n = 83) in 241 patients with limited-stage gastric MALT lymphoma. Chemotherapy consisted of 3 courses of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) every 21 days followed by 4 courses of CVP (i.e., the identical regimen without doxorubicin). After a median FUP of 7.5 years, an identical ORR of 100% in all 3 groups was seen and a significantly better 10-year event-free survival in the chemotherapy group (87%) compared with surgery (52%) or radiotherapy (52%) was documented (p < .01). In total, 38 patients (46%) in the surgery arm, 30 (38%) in the radiotherapy and 10 (12%) in the chemotherapy arm experienced relapses. However, the 10-year OS was not significantly different (p = .4), which can be explained by effective salvage therapy after failure of local therapies. No attempts to treat patients with HP eradication had been made in this old series; thus, that study is difficult to put in the context of patients with HP-refractory gastric MALT lymphoma. However, this is as yet the only randomized study to directly compare radiation and chemotherapy in localized disease, showing a favorable event-free survival for systemic therapy in stage I and II disease.

Anthracycline-based chemotherapy, either using R-CHOP or R-cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine, and prednisone (CNOP) (in patients older than 65 years or with pre-existing cardiac disease), was assessed in a retrospective series of 26 MALT lymphoma patients [12]. All patients responded (CR 77%, PR 23%), but four relapses occurred at a median FUP of 19 months. Toxicity was quite substantial (31% neutropenia grade III/IV requiring granulocyte colony-stimulating factor support in the following cycles (nausea, polyneuropathy, thrombocytopenia). In view of the indolent nature of MALT lymphoma, the investigators concluded that this treatment is too toxic as the initial approach for most patients with MALT lymphoma. In addition, two retrospective series have found no evidence of benefit with the addition of anthracyclines to CVP-like regimens or monotherapy with an alkylator [34, 35].

In a retrospective analysis of 78 patients with extragastric MALT lymphoma managed with different chemotherapies, the ORR was 92% (CRR, 72%) [34], with no advantage for the 38 patients receiving anthracyclines. Similar data were reported by Papaxoinis et al. [35], with a CRR of 73% and 68% for MALT lymphoma patients treated with or without anthracyclines, with an ORR of 91% and 82%, respectively.

The combination of fludarabine plus mitoxantrone (FM) was successfully tested in 20 patients with an ORR of 100% and no relapses at 32 months. Some of these patients have been treated with FM for disease relapse after first-line CVP [36]. The same study group recently conducted a retrospective analysis of 17 patients with pulmonary MALT lymphoma treated with either FM or R-FM, confirming the expected high therapeutic activity [37]. Additional small studies have confirmed the high activity of this regimen [38] (Table 2).

Summary

Anthracyclines might be used in fit patients with a high tumor burden or acute symptomatic disease, in whom side effects might be acceptable, but should not be applied as front-line treatment in most MALT lymphoma patients, who are usually asymptomatic and do not require aggressive therapy.

Rituximab

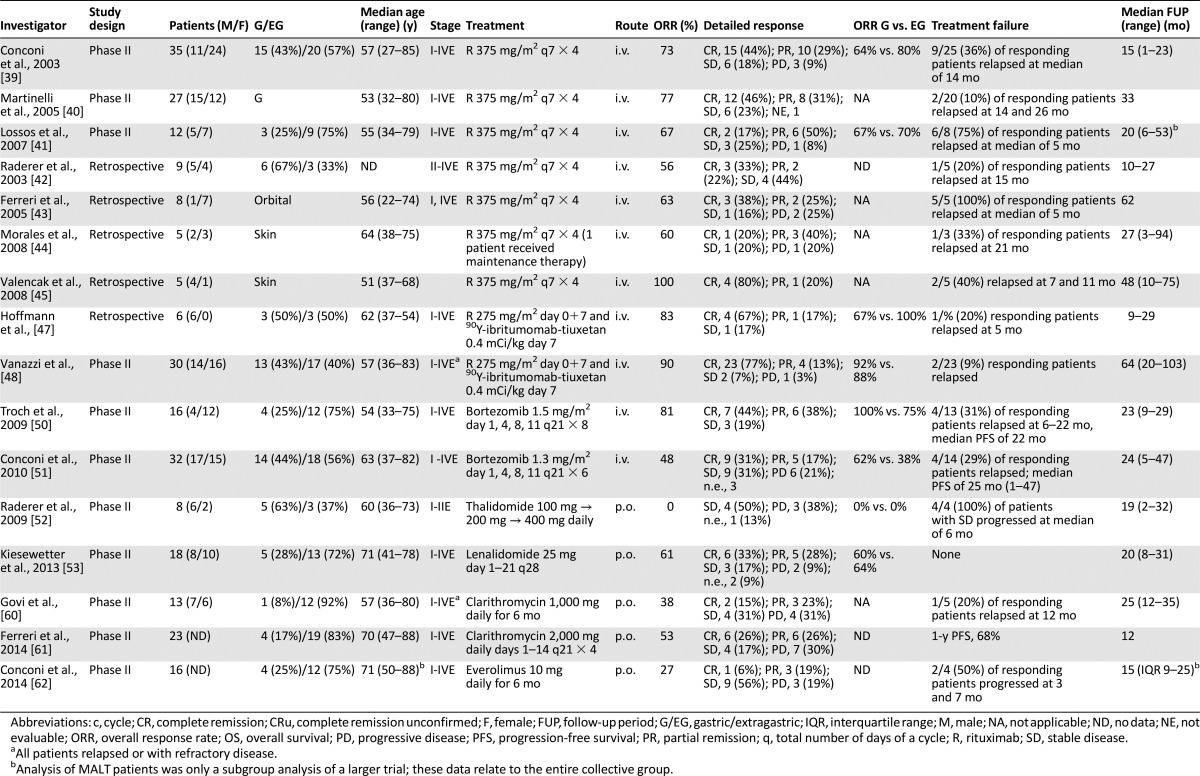

Three phase II trials focusing on the activity of R-monotherapy in MALT lymphoma have been published, including 74 patients (Table 3) [39–41]. Additionally, as mentioned, the IELSG-19 randomized trial on chlorambucil with or without R has also introduced a post hoc R-monotherapy arm (115 patients) in 2006 to further define the activity of R-upfront monotherapy [16]. Although having been published in abstract form only, the data are in line with the two-arm trial reported earlier with no significant difference between chlorambucil and R-monotherapies, but a final publication of data are pending.

Table 3.

Immunotherapy and targeted therapy for MALT lymphoma

A standard dose of R (i.e., 4 weekly doses of 375 mg/m2) was used for most trials. Patients with any disease stage have been included in the three published phase II trials [39–41]. Two trials included various primary sites of MALT lymphoma, and one exclusively studied gastric MALT lymphoma resistant to or not eligible for HP eradication [40]. Taken together, ORRs oscillated between 67% and 77% (CRR, 17%–46%). In the two trials that included both gastric and extragastric lymphoma, a comparable ORR was achieved in both groups (i.e., 64% vs. 80% [39] and 67% vs. 70% [41]). One publication also analyzed response rates in chemotherapy therapy-naïve versus pretreated patients, showing significantly better response rates (p = .03) and a longer median time to treatment failure (p = .001) [39] in previously untreated individuals. In one series, the investigated have discussed better efficacy in a low tumor burden (i.e., localized disease) [40]. The t(11;18)(q21;q21) status was not predictive of response to R. Toxicities were mild, and, as in most other trials of indolent lymphomas, slight infusion reactions were the main side effect. Hematological toxicity was mild in two trials, and grade III neutropenia was observed in 10% of patients (3 of 27) in the gastric-only collective [40]. Apart from the relatively low CRR with R-monotherapy, also early relapses seemed to be common. Overall, relapses were reported in 10% of responding patients with gastric MALT lymphoma [40], in 36% of responding patients entered in the IELSG-6 trial [39] and in 75% of chemotherapy-naive patients [41], after a median FUP of 33, 15, and 20 months, respectively. In the latter series, all patients were switched to either radiation or R-CVP after relapse, resulting in a response in all patients. In addition to these prospective data, some smaller retrospective case series have been reported, with response rates again at 56%–63% (20%–38% CRR) and a median time to progression of 5–21 months for responding patients [42–44].

That R might nevertheless be very effective in the treatment of cutaneous MALT lymphomas was suggested in a small series published by Valencak et al. [45], who observed responses in 5 patients treated (including 4 CRs) with 2 relapses at 7 and 11 months.

Interestingly, using R, alone or in combinations, might potentially alter histological features of MALT lymphoma. It has been shown that R-containing treatment might lead to a clonal selection of CD20-negative malignant plasma cells, resulting in plasmacytic differentiation in some cases [46].

After a retrospective analysis of 6 patients had shown promising activity of 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan in pretreated patients [47], clinical activity was assessed in a more extensive study. From May 2004 to April 2011, 30 patients with relapsed/refractory MALT lymphoma—arising at any extranodal site—received 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan at the activity of 0.4 mCi/kg [48]. At the time of treatment, 13 of 30 patients had disseminated disease (stage III/IV). All patients had received previous treatment with a maximum of seven lines. ORR was 90%, with a CRR of 77%. With a median follow-up of 5.3 years, the median time to relapse was not reached; 2 patients experienced relapse after an initial CR; 18 of 23 patients with CRs were relapse free after >3 years and 12 of them after >5 years. Accordingly, 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan represents an active therapeutic option for patients with relapsed/refractory MALT lymphoma. An overview of targeted therapy and immunotherapy for MALT lymphoma is given in Table 3.

Summary

Currently, it has not been substantiated by published data that R is an indispensable part of treatment for MALT lymphomas. R-monotherapy has definitive, albeit limited, activity in MALT lymphoma without substantial side effects in patients not suitable for more intensive treatment. Judging from updated IELSG-19 data, the activity of R-monotherapy seems comparable to chlorambucil monotherapy. However, this monoclonal antibody remains an important anticancer agent in combination with bendamustine, purine analogs, and/or alkylators in the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed or relapsing MALT lymphoma.

Proteasome Inhibitors

It has repeatedly been suggested that MALT lymphoma and multiple myeloma (MM) share common features, including the potential to produce monoclonal immunoglobulins, such as is seen in up to 40% of patients [49]. Thus, the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib has been tested in two contemporaneous phase II trials focused on MALT lymphoma patients, using slightly different schedules. The first monocentric trial included a total of 16 patients, mostly with new diagnosed MALT lymphoma, using bortezomib at 1.5 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every 3 weeks for a maximum of 8 cycles [50]. The ORR was 81% (CRR, 44%), with 31% developing a relapse at a median FUP of 23 months (range, 9–29). In the second trial, performed by the IELSG, 32 patients with relapsed/refractory MALT lymphoma received bortezomib at 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 every 3 weeks, achieving a 48% ORR (CRR, 31%), 6 patients (21%) experienced lymphoma progression during therapy and 4 of 14 responders (29%) experienced relapse after a median FUP of 24 months [51]. The higher number of cycles (eight vs. six), the higher proportion of patients treated at diagnosis and the higher single dose might explain the better response rate in the Austrian trial [50]. Nevertheless, both trials reported a high number of adverse events: 15 of 16 patients (94%) required a dose reduction in the Austrian trial [50] and more than 65% of patients in the whole collective developed polyneuropathy. Moreover, grade III-IV neutropenia and thrombocytopenia were seen, especially with the higher dose, suggesting the potential for unacceptably high toxicities in this indolent disease despite substantial activity.

Summary

Bortezomib remains an experimental drug in the management of MALT lymphomas. The high rates of polyneuropathy and hematological toxicity limit its use in routine practice and suggest that new schedules and lower doses should be investigated.

Immunomodulators

A further treatment approach adapted from MM is the application of immunomodulators (IMiDs) thalidomide and lenalidomide. However, a pilot study of thalidomide was closed prematurely owing to toxicity and absent responses among 8 recruited patients (SD, 50%; PD, 38%; 1 early termination), after a median FUP of 19 months [52]. In contrast to these rather sobering results, the second-generation IMiD lenalidomide was successfully tested in a pilot study, including 18 patients with MALT lymphoma [53]. Treatment consisted of lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1–21 every 28 days. In 16 evaluable patients, an ORR of 69% was achieved, including 6 CRs and 5 PRs. Toxicity was manageable and consisted mostly of neutropenia (grade III in 3 patients) and pruritus/exanthema as the leading nonhematologic toxicity. Interim analysis of 40 evaluable patients treated with R plus lenalidomide showed a promising 80% ORR (CRR, 55%), with manageable toxicities [54]. The final results of this combination are awaited.

Summary

Preliminary results have shown that lenalidomide, alone or with R, is active in MALT lymphoma, suggesting that this IMID deserves further investigation in larger trials. In contrast, the limited available evidence does not support the use of thalidomide.

Clarithromycin

In vitro, preclinical, and clinical data have generated great interest in the antineoplastic and IMID activities of macrolides [55–57]. Clarithromycin alone or in combination with other IMIDs has been associated with encouraging results in MM or Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia [58, 59]. Two prospective trials have assessed activity and feasibility of salvage monotherapy with clarithromycin at two different dose levels in heavily pretreated patients with MALT lymphoma [60, 61]. A 6-month regimen of oral clarithromycin at 500 mg b.i.d. was associated with an ORR of 38%, mostly in ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas, a 3-year PFS of 58%, and an excellent safety profile in 13 patients [60]. A recently completed phase II trial of 4 courses of oral clarithromycin 2 g/day, on days 1–14, every 21 days, in 23 patients with relapsed or refractory MALT lymphoma showed an ORR of 52% (CRR, 26%), a 1-year PFS of 68%, and excellent tolerance [61].

Summary

The high activity and excellent tolerance of clarithromycin reported in exploratory trials provide the rationale for future investigations on the antilymphoma activity of this macrolide, perhaps in combination with IMIDs.

The high activity and excellent tolerance of clarithromycin reported in exploratory trials provide the rationale for future investigations on the antilymphoma activity of this macrolide, perhaps in combination with IMIDs.

Everolimus

A recently published study investigated application of everolimus (10 mg/day) in 30 patients with relapsed/refractory marginal zone B-cell lymphomas, including 20 MALT lymphomas, 4 with nodal and 6 with splenic marginal zone lymphoma [62]. The ORR was 25%, with a median response duration of 7 months (range, 1.4–11+); 4 (25%) of the 16 evaluable patients with MALT lymphoma responded to treatment, with a single CR. Toxicities were substantial, with grade 3 or 4 infections in 17% of cases, mucositis and dental infection in 13%, pneumonitis in 13%, and neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in 17% each.

Summary

Given its low activity and poor tolerability, everolimus is not recommendable in the treatment of MALT lymphoma.

Conclusion

In recent years, systemic treatment approaches, including chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, IMIDs, and targeted drugs, have been increasingly used in localized and disseminated MALT lymphomas. Recent guidelines have recommended their use as a reasonable alternative to radiotherapy in gastric MALT lymphoma [63, 64]. Although there is now little doubt that systemic treatment approaches can be successfully applied, many relevant questions remain unanswered.

In view of the excellent prognosis of patients with MALT lymphoma and their usually generally good performance status, it seems advisable to induce as little toxicity as possible in these patients. From the data published to date, it still appears sensible to include patients with MALT lymphomas in clinical trials to further define the activity of novel therapeutic concepts and establish the role of systemic therapies compared with radiation in localized disease. MALT lymphoma is a lymphoproliferative disorder with some molecular and biological heterogeneity according to the origin of the lymphoma. The pathogenesis, molecular profile, and clinical behavior can vary among the different forms of MALT lymphoma, as could therapeutic choices and outcome. Thus, whether the whole group of patients with MALT lymphoma should be enrolled in future trials, irrespective of extranodal organ of origin or whether trials focused exclusively on specific primary forms of MALT lymphomas should be preferred remains a relevant question in this field.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Barbara Kiesewetter, Andrés J.M. Ferreri, Markus Raderer

Collection and/or assembly of data: Barbara Kiesewetter, Andrés J.M. Ferreri

Data analysis and interpretation: Barbara Kiesewetter, Andrés J.M. Ferreri, Markus Raderer

Manuscript writing: Barbara Kiesewetter, Andrés J.M. Ferreri, Markus Raderer

Final approval of manuscript: Barbara Kiesewetter, Andrés J.M. Ferreri, Markus Raderer

Disclosures

Andrés J.M. Ferreri: Celgene (C/A), Gilead (H), Mundipharma (RF); Markus Raderer: Novartis, Roche, Celgene, Ipsen, Eisai (H). The other author indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Isaacson PG, Chott A, Nakumura S, et al. Extranodal marginal cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated tissue (MALT lymphoma). In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL. et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon, France: IARC, 2008:214–217. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, et al. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;338:1175–1176. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischbach W, Goebeler-Kolve ME, Dragosics B, et al. Long term outcome of patients with gastric marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) following exclusive Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: Experience from a large prospective series. Gut. 2004;53:34–37. doi: 10.1136/gut.53.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreri AJ, Govi S, Pasini E, et al. Chlamydophila psittaci eradication with doxycycline as first-line targeted therapy for ocular adnexae lymphoma: Final results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2988–2994. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, et al. Bacteria-eradicating therapy with doxycycline in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: A multicenter prospective trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1375–1382. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiesewetter B, Raderer M. Antibiotic therapy in nongastrointestinal MALT lymphoma: A review of the literature. Blood. 2013;122:1350–1357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-486522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcaini L, Vallisa D, Rattotti S, et al. Antiviral treatment in patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas associated with HCV infection: A study of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1404–1410. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, et al. Localized mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated with radiation therapy has excellent clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4157–4164. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goda JS, Gospodarowicz M, Pintilie M, et al. Long-term outcome in localized extranodal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas treated with radiotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:3815–3824. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Son SH, Choi BO, Kim GW, et al. Primary radiation therapy in patients with localized orbital marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT Lymphoma) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammel P, Haioun C, Chaumette MT, et al. Efficacy of single-agent chemotherapy in low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with prominent gastric expression. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2524–2529. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.10.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raderer M, Wohrer S, Streubel B, et al. Activity of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin/mitoxantrone, vincristine and prednisone in patients with relapsed MALT lymphoma. Oncology. 2006;70:411–417. doi: 10.1159/000098555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raderer M, Wöhrer S, Bartsch R, et al. Phase II study of oxaliplatin for treatment of patients with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8442–8446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.8532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orciuolo E, Buda G, Sordi E, et al. 2CdA chemotherapy and rituximab in the treatment of marginal zone lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2010;34:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wöhrer S, Drach J, Hejna M, et al. Treatment of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) with mitoxantrone, chlorambucil and prednisone (MCP) Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1758–1761. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucca E, Conconi A, Laszlo D, et al. Addition of rituximab to chlorambucil produces superior event-free survival in the treatment of patients with extranodal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma: 5-Year analysis of the IELSG-19 randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:565–572. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lévy M, Copie-Bergman C, Amiot A, et al. Rituximab and chlorambucil versus rituximab alone in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma according to t(11;18) status: A monocentric non-randomized observational study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:940–944. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.729832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H, Ye H, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, et al. T(11;18) is a marker for all stage gastric MALT lymphomas that will not respond to H. pylori eradication. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1286–1294. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lévy M, Copie-Bergman C, Molinier-Frenkel V, et al. Treatment of t(11;18)-positive gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma with rituximab and chlorambucil: Clinical, histological, and molecular follow-up. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:284–290. doi: 10.3109/10428190903431820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rigacci L, Nassi L, Puccioni M, et al. Rituximab and chlorambucil as first-line treatment for low-grade ocular adnexal lymphomas. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:565–568. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoefnagel JJ, Vermeer MH, Jansen PM, et al. Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: Clinical and therapeutic features in 50 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1139–1145. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.9.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben Simon GJ, Cheung N, McKelvie P, et al. Oral chlorambucil for extranodal, marginal zone, B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue of the orbit. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1209–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hancock BW, Qian W, Linch D, et al. Chlorambucil versus observation after anti-Helicobacter therapy in gastric MALT lymphomas: Results of the international randomised LY03 trial. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:367–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang HJ, Kim WS, Kim SJ, et al. Phase II trial of rituximab plus CVP combination chemotherapy for advanced stage marginal zone lymphoma as a first-line therapy: Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) study. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:543–551. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aguiar-Bujanda D, Llorca-Martinez I, Rivero-Vera JC, et al. Treatment of gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone. 139. Hematol Oncol. 2014;32 doi: 10.1002/hon.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: An open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1203–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salar A, Domingo-Domenech E, Panizo C et al. Final results of a multicenter phase II trial with bendamustine and rituximab as first line treatment for patients with MALT lymphoma (MALT-2008-01). Paper presented at: ASH 2012 Annual Meeting, 2012 (abstract 3691). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiesewetter B, Mayerhoefer ME, Lukas J, et al. Rituximab plus bendamustine is active in pretreated patients with extragastric marginal zone B cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) Ann Hematol. 2014;93:249–253. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1865-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jäger G, Neumeister P, Brezinschek R, et al. Treatment of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type with cladribine: A phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3872–3877. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jäger G, Neumeister P, Quehenberger F, et al. Prolonged clinical remission in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type treated with cladribine: 6 Year follow-up of a phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1722–1723. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troch M, Kiesewetter B, Willenbacher W, et al. Rituximab plus subcutaneous cladribine in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue: A phase II study by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Medikamentose Tumortherapie. Haematologica. 2013;98:264–268. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.072587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salar A, Domingo-Domenech E, Estany C, et al. Combination therapy with rituximab and intravenous or oral fludarabine in the first-line, systemic treatment of patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type. Cancer. 2009;115:5210–5217. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, et al. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the stomach: Results of a controlled clinical trial. Med Oncol. 2005;22:57–62. doi: 10.1385/MO:22:1:057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, et al. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003;101:2489–2495. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papaxoinis G, Fountzilas G, Rontogianni D, et al. Low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: A retrospective analysis of 97 patients by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) Ann Oncol. 2008;19:780–786. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zinzani PL, Stefoni V, Musuraca G, et al. Fludarabine-containing chemotherapy as frontline treatment of nongastrointestinal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100:2190–2194. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zinzani PL, Pellegrini C, Gandolfi L, et al. Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the lung: experience with fludarabine and mitoxantrone-containing regimens. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31:183–188. doi: 10.1002/hon.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Economopoulos T, Psyrri A, Fountzilas G, et al. Phase II study of low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphomas with fludarabine and mitoxantrone followed by rituximab consolidation: Promising results in marginal zone lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:68–74. doi: 10.1080/10428190701784714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conconi A, Martinelli G, Thiéblemont C, et al. Clinical activity of rituximab in extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type. Blood. 2003;102:2741–2745. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinelli G, Laszlo D, Ferreri AJ, et al. Clinical activity of rituximab in gastric marginal zone non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma resistant to or not eligible for anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1979–1983. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lossos IS, Morgensztern D, Blaya M, et al. Rituximab for treatment of chemoimmunotherapy naive marginal zone lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1630–1632. doi: 10.1080/10428190701457949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raderer M, Jäger G, Brugger S, et al. Rituximab for treatment of advanced extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Oncology. 2003;65:306–310. doi: 10.1159/000074641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Martinelli G, et al. Rituximab in patients with mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Haematologica. 2005;90:1578–1579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morales AV, Advani R, Horwitz SM, et al. Indolent primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: Experience using systemic rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:953–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valencak J, Weihsengruber F, Rappersberger K, et al. Rituximab monotherapy for primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma: Response and follow-up in 16 patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:326–330. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Troch M, Kiesewetter B, Dolak W, et al. Plasmacytic differentiation in MALT lymphomas following treatment with rituximab. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:723–728. doi: 10.1007/s00277-011-1387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffmann M, Troch M, Eidherr H, et al. 90Y-ibritumomab-tiuxetan (Zevalin) in heavily pretreated patients with mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:42–45. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.534519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanazzi A, Grana C, Crosta C, et al. Efficacy of 90Yttrium-ibritumomab-tiuxetan in relapsed/refractory extranodal marginal-zone lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2014;32:10–15. doi: 10.1002/hon.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wöhrer S, Kiesewetter B, Fischbach J, et al. Retrospective comparison of the effectiveness of various treatment modalities of extragastric MALT lymphoma: A single-center analysis. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1287–1295. doi: 10.1007/s00277-014-2042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Troch M, Jonak C, Müllauer L, et al. A phase II study of bortezomib in patients with MALT lymphoma. Haematologica. 2009;94:738–742. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Conconi A, Martinelli G, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Clinical activity of bortezomib in relapsed/refractory MALT lymphomas: Results of a phase II study of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG) Ann Oncol. 2011;22:689–695. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Troch M, Zielinski C, Raderer M. Absence of efficacy of thalidomide monotherapy in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1446–1447. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kiesewetter B, Troch M, Dolak W, et al. A phase II study of lenalidomide in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) Haematologica. 2013;98:353–356. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raderer M, Kiesewetter B, Willenbacher W. A phase II study of rituximab plus lenalidomide in patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). Paper presented at: 19th Congress of EHA, 2014 (abstract 651). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aoki D, Ueno S, Kubo F, et al. Roxithromycin inhibits angiogenesis of human hepatoma cells in vivo by suppressing VEGF production. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurdowska A, Noble JM, Griffith DE. The effect of azithromycin and clarithromycin on ex vivo interleukin-8 (IL-8) release from whole blood and IL-8 production by human alveolar macrophages. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:867–870. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yatsunami J, Tsuruta N, Hara N, et al. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by roxithromycin, a 14-membered ring macrolide antibiotic. Cancer Lett. 1998;131:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coleman M, Leonard J, Lyons L, et al. Treatment of Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia with clarithromycin, low-dose thalidomide, and dexamethasone. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:270–274. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niesvizky R, Jayabalan DS, Christos PJ, et al. BiRD (Biaxin [clarithromycin]/Revlimid [lenalidomide]/dexamethasone) combination therapy results in high complete- and overall-response rates in treatment-naive symptomatic multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:1101–1109. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Govi S, Dognini GP, Licata G, et al. Six-month oral clarithromycin regimen is safe and active in extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas: Final results of a single-centre phase II trial. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:226–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferreri AJ, Sassone M, Kiesewetter B et al. High-dose clarithromycin is a feasible and active monotherapy for patients with relapsed/ refractory extranodal marginal zone lymphoma [EMZL]: Results from the “HD-K” phase II trial. Paper presented at: 19th Congress of EHA, 2014 (abstract 442). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Conconi A, Raderer M, Franceschetti S, et al. Clinical activity of everolimus in relapsed/refractory marginal zone B-cell lymphomas: Results of a phase II study of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Br J Haematol. 2014;166:69–76. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zucca E, Copie-Bergman C, Ricardi U, et al. Gastric marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi144–vi148. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Fischbach W, Aleman BM, et al. EGILS consensus report: Gastric extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Gut. 2011;60:747–758. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]