Abstract

Background and objectives

The secular trend toward dialysis initiation at progressively higher levels of eGFR is not well understood. This study compared temporal trends in eGFR at dialysis initiation within versus outside the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)—the largest non–fee-for-service health system in the United States.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The study used linked data from the US Renal Data System, VA, and Medicare to compare temporal trends in eGFR at dialysis initiation between 2000 and 2009 (n=971,543). Veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA were compared with three groups who initiated dialysis outside the VA: (1) veterans whose dialysis was paid for by the VA, (2) veterans whose dialysis was not paid for by the VA, and (3) nonveterans. Logistic regression was used to estimate average predicted probabilities of dialysis initiation at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Results

The adjusted probability of starting dialysis at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 increased over time for all groups but was lower for veterans who started dialysis within the VA (0.31; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.30 to 0.32) than for those starting outside the VA, including veterans whose dialysis was (0.36; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.38) and was not (0.40; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.40) paid for by the VA and nonveterans (0.39; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.39). Differences in eGFR at initiation within versus outside the VA were most pronounced among older patients (P for interaction <0.001) and those with a higher risk of 1-year mortality (P for interaction <0.001).

Conclusions

Temporal trends in eGFR at dialysis initiation within the VA mirrored those in the wider United States dialysis population, but eGFR at initiation was consistently lowest among those who initiated within the VA. Differences in eGFR at initiation within versus outside the VA were especially pronounced in older patients and those with higher 1-year mortality risk.

Keywords: dialysis initiation, Department of Veterans Affairs, health system

Introduction

More than 100,000 Americans start maintenance dialysis for ESRD every year (1). While dialysis is a life-sustaining intervention for many patients, it is a demanding treatment, and patients receiving maintenance dialysis have a high prevalence of depression (2), functional disability (3), and impaired quality of life (4,5). Dialysis is also very costly, with annual Medicare expenditures for ESRD estimated at $26 billion (1).

The optimal timing of dialysis initiation remains uncertain. Despite recent evidence to the contrary (6–17), initial observational studies suggested that starting dialysis at higher levels of kidney function might be beneficial, and opinion-based clinical practice guidelines have generally supported a progressively more liberal approach to dialysis initiation (18). Until recently (19), there has been a pervasive temporal trend toward dialysis initiation at increasingly higher levels of eGFR (10,12,20–23). The drivers of this trend are poorly understood (6–8,10–16). While some have speculated that providers' financial incentives may encourage earlier dialysis initiation, evidence to support this possibility is conflicting (10). A survey of European nephrologists found that provider reimbursement was associated with higher self-reported target levels of eGFR at initiation (24). However, an upward trend in eGFR has been reported for patients treated in both for-profit and not-for-profit dialysis facilities in the United States (10) and in countries with a range of different reimbursement structures (12,22,23), arguing against a strong role for financial incentives.

Because the decision to start dialysis is typically made before arrival at an outpatient dialysis facility, the health system in which dialysis is initiated may be a consideration in understanding trends in timing of dialysis initiation. Similar to other areas of clinical practice (25,26), some evidence suggests that system-level factors may be important in shaping treatment decisions and dialysis initiation practices for patients with ESRD (27,28). However, to our knowledge, no prior studies have rigorously compared eGFR at initiation across health systems with differing reimbursement structures within the United States.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) supports the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing care to more than 8 million veterans each year (29). For some types of care there are systematic differences in practices and utilization within versus outside the VA. For example, coronary angiography after acute myocardial infarction is less frequent (30,31) within the VA than in the private sector, with no significant difference in outcomes (32). The objective of the current study is to determine whether there are differences in the timing of dialysis initiation within versus outside the VA.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

We linked data from the VA, Medicare, and the US Renal Data System (USRDS)—a comprehensive national registry of patients with ESRD receiving RRT—using a crosswalk file supplied by the Veterans Information Resource Center. Veterans were defined as those who enrolled in, obtained health care from, or received compensation or pension benefits from the VA and were thus eligible for VA services (33). Among veterans, we used VA and Medicare administrative data to determine the location of the patient’s initial dialysis. Patient characteristics, eGFR at dialysis initiation, and mortality were ascertained from USRDS standard analyses files (1).

We identified all patients age ≥18 years who started dialysis between January 1, 2000, and September 25, 2009. We excluded patients with missing information on sex (n=52) or eGFR at dialysis initiation (n=29,877) and those with a history of preemptive kidney transplant (n=17,154), yielding an analytic cohort of 971,543 patients, including 120,210 (12.4%) veterans. Among veterans, 16,761 (13.9%) initiated dialysis at VA medical centers, 4013 (3.3%) initiated outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA, and 99,436 (82.7%) initiated outside the VA with dialysis not paid for by the VA.

The institutional review board at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System approved this study.

Exposure

The primary exposure was veteran status, site of first dialysis, and dialysis payment source. Veterans receive maintenance dialysis in several settings, including VA medical centers and medical centers and dialysis facilities outside the VA. The VA pays for dialysis for some but not all veterans treated outside the VA under the Fee Basis system or contract. We compared eGFR at initiation among veterans who initiated dialysis at a VA medical center with that in three other groups who initiated dialysis outside the VA: (1) veterans whose dialysis was paid for by the VA under Fee Basis or contract, (2) veterans whose dialysis was paid for by other insurance and not by the VA, and (3) nonveterans. The location of each veteran’s first dialysis session was ascertained by searching for dialysis procedure codes in VA inpatient and outpatient administrative data and Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims (Current Procedural Terminology codes 90935–90937, 90945–90947, 90999, and G0257; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, procedure codes 39.95, 54.98) occurring within 30 days before or after the first ESRD service date recorded in the USRDS patients file. Veterans were considered to have initiated dialysis within the VA if the closest dialysis procedure code to the USRDS first service date occurred in VA files. Among veterans who initiated dialysis outside the VA, we distinguished between those for whom the VA did and did not pay for dialysis using the VA Fee Basis files.

Main Outcome

The primary outcome was eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at dialysis initiation, based on the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation, which was the dominant method for estimating GFR for much of the study period (34).

Covariates

Patient characteristics at dialysis initiation were ascertained from USRDS, including year of dialysis initiation, age, sex, race, ethnicity, employment status, rurality (based on ZIP code of residence recorded in USRDS and VA definitions of rurality [35]), ESRD network, dialysis modality, body mass index, serum albumin (≥3 or <3 g/dl or missing), cause of primary renal disease, and comorbid conditions (cardiac disease, stroke/transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, smoking, alcohol abuse, drug use, or inability to ambulate or transfer). We also classified patients by quintile of risk for 1-year mortality, wherein risk was measured as the predicted probability of 1-year mortality from a logistic regression that included the aforementioned covariates. Much of the information obtained from USRDS was derived from the ESRD Medical Evidence report (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS]-2728), which is completed by the nephrology provider around the time of ESRD onset. This form was revised in 2005 to include additional information about predialysis nephrology care; thus, results for predialysis nephrology care pertain only to cohort members who initiated dialysis in 2005–2009.

Statistical Analyses

We compared patient characteristics by veteran status and payer using one-way ANOVA and chi-squared tests. We examined temporal trends in eGFR at initiation across these groups using logistic regression to estimate the average predicted probabilities of dialysis initiation at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2, adjusted for covariates described above. The average predicted probability gives the estimated probability of starting dialysis at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for a hypothetical “average” patient in the group who has mean values for each of the adjustment covariates. Age was modeled as age and age2 to accommodate nonlinearity in the relationship with eGFR. A two-sample test of proportions was used to compare the adjusted predicted probability of dialysis initiation at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 within the VA in 2000 versus 2009. We calculated differences in the predicted probabilities of dialysis initiation at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 between veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA and each of the other groups. We conducted sensitivity analyses in the subgroup of patients who survived >90 days after dialysis initiation (n=888,278) and in patients who initiated dialysis after June 1, 2005 (n=448,187), and therefore had information regarding predialysis nephrology care. We conducted analyses stratified by all variables in the primary analysis along with quintile of risk for 1-year mortality. Interactions between the primary predictor and age or 1-year mortality risk quintile were examined in separate models; the point estimates reported for the main model do not reflect the models with interaction terms. To evaluate for consistency in observed associations over time, we also tested for interactions between the primary predictor and time period of initiation (2000–2004 and 2005–2009) within each subgroup. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata software, version 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA had the lowest mean eGFR at initiation overall (mean±SD, 9.27±4.63 ml/min per 1.73 m2 versus 10.17±4.81 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for veterans who initiated outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA, 10.88±5.65 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for veterans who initiated outside the VA under other insurance, and 9.73±5.37 mL/min/1.73 m2 for nonveterans) (Table 1) and for all age groups (Supplemental Table 1). Veterans who initiated dialysis at VA medical centers were least likely to initiate dialysis at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (34.3% versus 43.0% for veterans initiating outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA, 47.4% for veterans initiating outside the VA under other insurance, and 37.8% for nonveterans).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients initiating dialysis in the United States between 2000 and 2009

| Characteristic | Veteran, Initiated Dialysis within VA (n=16,761) | Veteran, Initiated Dialysis outside VA, Paid for by VA (n=4013) | Veteran, Initiated Dialysis outside VA, Not Paid for by VA (n=99,436) | Nonveteran (n=851,333) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal function | |||||

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 9.27±4.63 | 10.17±4.81 | 10.91±5.68 | 9.73±5.37 | <0.001 |

| eGFR ≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 5754 (34.3) | 1725 (43.0) | 47,303 (47.6) | 322,131 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| eGFR ≥15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n (%) | 1391 (8.3) | 470 (11.7) | 16,615 (16.7) | 102,651 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 64.1±11.7) | 62.4±11.0 | 70.3±11.8 | 62.1±15.5 | <0.001 |

| Age category, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| <55 yr | 3563 (21.3) | 867 (21.6) | 10,894 (11.0) | 255,369 (30.0) | |

| 55–64 yr | 5436 (32.4) | 1694 (42.2) | 17,341 (17.4) | 186,927 (22.0) | |

| 65–74 yr | 4037 (24.1) | 758 (19.0) | 27,846 (28.0) | 203,369 (23.9) | |

| 75–84 yr | 3243 (19.4) | 615 (15.3) | 36,081 (36.3) | 162,990 (19.2) | |

| ≥85 yr | 482 (2.9) | 79 (2.0) | 7274 (7.3) | 42,678 (5.0) | |

| Women, n (%) | 303 (1.8) | 59 (1.5) | 5996 (6.0) | 429,890 (50.5) | <0.001 |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 9661 (57.6) | 2649 (66.0) | 75,825 (76.3) | 546,329 (64.2) | |

| Black | 6655 (39.7) | 1219 (30.4) | 20,764 (20.9) | 250,522 (29.4) | |

| Asian | 221 (1.3) | 71 (1.8) | 1497 (1.5) | 36,115 (4.2) | |

| Native American | 139 (0.8) | 65 (1.6) | 1115 (1.1) | 9873 (1.2) | |

| Other/missing | 85 (0.5) | 9 (0.2) | 235 (0.2) | 8494 (1.0) | |

| Hispanic | 1596 (9.5) | 282 (7.0) | 5515 (5.6) | 121,422 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Employment status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Employed full- or part-time | 1042 (6.2) | 263 (6.6) | 7446 (7.5) | 89,444 (10.5) | |

| Unemployed | 2941 (17.6) | 693 (17.3) | 8976 (9.0) | 180,104 (21.2) | |

| Retired/homemaker | 12,116 (72.3) | 2921 (72.8) | 78,866 (79.3) | 531,987 (62.5) | |

| Other/missing | 662 (4.0) | 136 (3.4) | 4148 (4.2) | 49,798 (5.9) | |

| Rurality, n (%)a | <0.001 | ||||

| Urban | 10,556 (63.1) | 1753 (44.0) | 55,249 (55.7) | 519,764 (61.3) | |

| Rural | 6026 (36.0) | 2153 (54.0) | 43,086 (43.5) | 323,403 (38.1) | |

| Highly rural | 136 (0.8) | 79 (2.0) | 795 (0.8) | 5,158 (0.6) | |

| Dialysis type, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Hemodialysis | 16,361 (97.6) | 3730 (93.0) | 92,894 (93.4) | 792,575 (93.1) | |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 395 (2.4) | 283 (7.1) | 6501 (6.4) | 57,503 (6.8) | |

| Other/Missing | 5 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 141 (0.1) | 1255 (0.2) | |

| BMI category, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Underweight, <18.5 kg/m2 | 712 (4.3) | 131 (3.3) | 3596 (3.6) | 38,965 (4.6) | |

| Normal weight, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 5840 (34.8) | 1214 (30.3) | 36,738 (37.0) | 288,070 (33.8) | |

| Overweight, 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 5402 (32.2) | 1255 (31.3) | 32,215 (32.4) | 235,824 (27.7) | |

| Obese class 1, 30–34.9 kg/m2 | 2817 (16.8) | 762 (19.0) | 15,872 (16.0) | 140,595 (16.5) | |

| Obese class 2, 35–39.9 kg/m2 | 1125 (6.7) | 377 (9.4) | 6099 (6.1) | 72,114 (8.5) | |

| Obese class 3, ≥40.0 kg/m2 | 699 (4.2) | 229 (5.7) | 4011 (4.0) | 67,012 (7.9) | |

| Missing | 166 (1.0) | 45 (1.1) | 905 (0.9) | 8753 (1.0) | |

| Serum albumin, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| ≥3 g/dl | 8793 (52.5) | 2049 (51.1) | 48,927 (49.2) | 386,216 (45.4) | |

| <3 g/dl | 5645 (33.7) | 1001 (24.9) | 26,481 (26.6) | 252,890 (29.7) | |

| Missing | 2323 (13.9) | 963 (24.0) | 24,028 (24.2) | 212,227 (24.9) | |

| Primary renal disease, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8128 (48.5) | 2103 (52.4) | 41,434 (41.7) | 391,876 (46.0) | |

| Hypertension | 4282 (25.6) | 1039 (25.9) | 32,066 (32.3) | 234,651 (27.6) | |

| GN | 1197 (7.1) | 267 (6.7) | 6976 (7.0) | 63,851 (7.5) | |

| Acute tubular necrosis | 409 (2.4) | 67 (1.7) | 2900 (2.9) | 19,734 (2.3) | |

| Other renal disease | 1928 (11.5) | 398 (9.9) | 11,838 (11.9) | 107,799 (12.7) | |

| Missing | 817 (4.9) | 139 (3.5) | 4222 (4.3) | 33,422 (3.9) | |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | |||||

| Cardiac | 7680 (45.8) | 1868 (46.6) | 57,820 (58.2) | 390,671 (45.9) | <0.001 |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack | 1795 (10.7) | 406 (10.1) | 11,562 (11.6) | 79,404 (9.3) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2455 (14.7) | 627 (15.6) | 19,479 (19.6) | 118,104 (13.9) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 14,249 (85.0) | 3444 (85.8) | 81,066 (81.5) | 698,893 (82.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10,137 (60.5) | 2586 (64.4) | 53,641 (54.0) | 484,518 (56.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1643 (9.8) | 449 (11.2) | 12,668 (12.7) | 67,973 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Malignancy | 1518 (9.1) | 278 (7.0) | 10,421 (10.5) | 53,995 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 1598 (9.5) | 507 (12.6) | 5585 (5.6) | 47,680 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 591 (3.5) | 140 (3.5) | 1546 (1.6) | 12,203 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Illicit drug use | 615 (3.7) | 83 (2.1) | 703 (0.7) | 10,308 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Inability to walk or transfer | 945 (5.6) | 190 (4.7) | 5826 (5.9) | 49,399 (5.8) | 0.02 |

| Prior nephrology care, n (%)b | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 1817 (23.9) | 556 (23.1) | 12,004 (26.8) | 124,127 (31.6) | |

| <6 mo | 775 (10.2) | 304 (12.6) | 5295 (11.8) | 43,338 (11.0) | |

| 6–12 mo | 1946 (25.6) | 601 (25.0) | 10,351 (23.1) | 88,914 (22.6) | |

| >12 mo | 2330 (30.6) | 678 (28.2) | 12,169 (27.2) | 90,014 (22.9) | |

| Missing | 739 (9.7) | 267 (11.1) | 4908 (11.0) | 47,054 (12.0) | |

| Risk quintile, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| 1 (low risk) | 2848 (17.0) | 972 (24.4) | 11,824 (11.9) | 177,988 (21.0) | |

| 2 | 4126 (24.7) | 1118 (28.1) | 15,261 (15.4) | 173,126 (20.4) | |

| 3 | 3979 (23.8) | 895 (22.5) | 20,319 (20.5) | 168,438 (19.9) | |

| 4 | 3250 (19.4) | 589 (14.8) | 25,770 (26.0) | 164,022 (19.3) | |

| 5 (high risk) | 2515 (15.0) | 411 (10.3) | 25,956 (26.2) | 164,749 (19.4) |

Values expressed with a plus/minus sign are the mean±SD.BMI, body mass index; VA, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Data were missing for 3385 patients (0.3%).

Data were only collected on the 448,187 patients who initiated dialysis after June 1, 2005

Compared with other groups, veterans initiating dialysis within the VA were more likely to be black and to reside in an urban area and less likely to be employed. Although hemodialysis was the dominant modality for all groups, veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA were less likely to start with peritoneal dialysis compared with the other groups. Veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA had the second highest prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and smoking and the highest prevalence of alcohol abuse and illicit drug use. For the subset of patients who initiated dialysis after June 1, 2005, veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA were more likely to have been under the care of a nephrologist before initiation (66.4%) than veterans initiating outside of the VA under other insurance (62.4%) or nonveterans (56.5%).

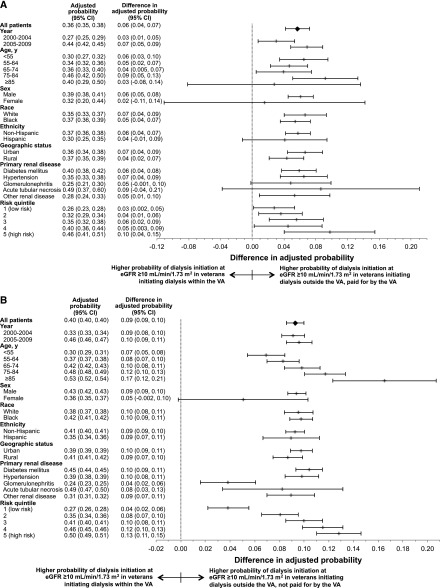

Temporal Trends in Dialysis Timing in the VA

From 2000 to 2009, mean eGFR at dialysis initiation increased from 8.26±4.28 to 10.60±5.49 ml/min per 1.73 m2 among patients initiating dialysis at VA medical centers; from 8.74±3.31 to 11.06±4.85 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for veterans who initiated outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA; from 9.59±5.14 to 12.28±6.31 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for veterans who initiated outside the VA under other insurance; and from 8.67±4.72 to 10.74±5.74 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for nonveterans. The adjusted probability of starting dialysis with an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 increased over time for all groups (Figure 1). Among veterans who initiated dialysis within the VA, the probability of starting dialysis with an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 increased from 0.20 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.18 to 0.22) in 2000 to 0.42 (95% CI, 0.39 to 0.44) in 2009 (P<0.001), compared with 0.25 (95% CI, 0.19 to 0.30) to 0.49 (95% CI, 0.45 to 0.54) for veterans who initiated outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA, 0.29 (95% CI, 0.28 to 0.30) to 0.51 (95% CI, 0.49 to 0.52) for veterans who initiated outside the VA under other insurance, and 0.29 (95% CI, 0.28 to 0.29) to 0.49 (95% CI, 0.48 to 0.49) for nonveterans.

Figure 1.

Temporal trends in adjusted probability of dialysis initiation at eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 by veteran status, payer, and location of dialysis initiation. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. VA, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Comparison of VA and Non-VA Groups

The adjusted probability of initiating dialysis at an eGFR ≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 within the VA was 0.31 (95% CI, 0.30 to 0.31), compared with 0.36 (95% CI, 0.35 to 0.38) for veterans initiating outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA, 0.40 (95% CI, 0.40 to 0.40) for veterans initiating outside the VA under other insurance, and 0.39 (95% CI, 0.39 to 0.39) for nonveterans (Supplemental Table 2, Table 2). Results were broadly consistent in sensitivity analyses among patients who survived beyond 90 days after dialysis initiation and when adjusting for predialysis nephrology care.

Table 2.

Risk of dialysis initiation at eGFR ≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 by veteran status, payer, and location of dialysis initiation

| Variable | Unadjusted Probability (95% CI) | Difference in Unadjusted Probability (95% CI) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted Probability (95% CI)a | Difference in Adjusted Probability (95% CI)a | Adjusted RR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veteran, initiated dialysis within VA | 0.34 (0.34 to 0.35) | Reference | Reference | 0.31 (0.30 to 0.31) | Reference | Reference |

| Veteran, initiated dialysis outside VA, paid for by VA | 0.43 (0.41 to 0.45) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.10) | 1.25 (1.20 to 1.30) | 0.36 (0.35 to 0.38) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.07) | 1.19 (1.13 to 1.24) |

| Veteran, initiated dialysis outside VA, not paid for by VA | 0.47 (0.47 to 0.48) | 0.13 (0.12 to 0.14) | 1.39 (1.36 to 1.42) | 0.40 (0.40 to 0.40) | 0.09 (0.09 to 0.10) | 1.30 (1.27 to 1.33) |

| Nonveteran | 0.38 (0.38 to 0.38) | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.04) | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.13) | 0.39 (0.39 to 0.39) | 0.08 (0.08 to 0.09) | 1.27 (1.24 to 1.30) |

VA, Department of Veterans Affairs; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Adjusted for year, age, age2, sex, race, ethnicity, employment status, rurality, ESRD network, dialysis type, body mass index category, serum albumin, primary renal disease, and comorbid conditions (cardiac, stroke/transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, smoking, alcohol abuse, illicit drug use, and inability to walk or transfer).

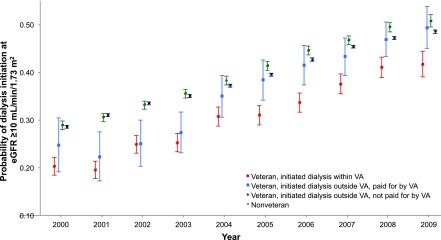

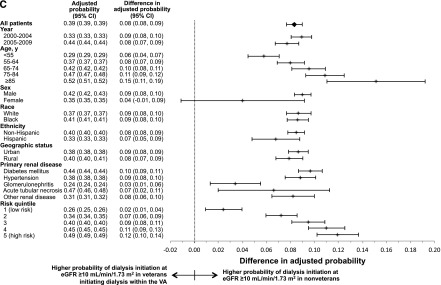

Stratified Analyses

Differences in the probability of dialysis initiation at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 for those initiating dialysis within versus outside the VA were similar across subgroups (Figure 2) but were especially pronounced for older patients (with the exception of veterans initiating outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA; P for interaction <0.001) and among patients with a higher 1-year mortality risk (P for interaction <0.001). Differences in eGFR at initiation across groups were consistent over time (Supplemental Figure 1). Absolute differences in eGFR at initiation were more pronounced at older ages and among those with higher mortality risk (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Differences in the adjusted probabilities of dialysis initiation at eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in patients initiating dialysis outside versus within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). (A) Veterans initiating dialysis outside the VA, paid for by the VA, (B) veterans initiating dialysis outside the VA, not paid for by the VA, and (C) nonveterans. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

From 2000 to 2009, there was an upward trend in eGFR at dialysis initiation among both veterans and nonveterans, regardless of where dialysis was initiated and whether the VA paid for treatment. Nevertheless, the risk of starting dialysis with an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 was consistently lower among veterans who initiated dialysis at VA medical centers than for any other group. The most pronounced differences in eGFR at initiation across groups were seen among older patients and those with a higher risk of 1-year mortality after dialysis initiation.

The finding of an upward trend in eGFR at initiation among veterans who started dialysis within the VA, where physicians are salaried and cannot bill insurance for dialysis services, seems to suggest that temporal trends in eGFR at initiation are unlikely to be explained entirely by provider-level financial incentives. Consistent with previous work, our study also suggests that these trends are not explained by changes in patient characteristics (6–8,10–16) or the clinical context of dialysis initiation (36) over time. Other hypotheses to explain trends in eGFR at dialysis initiation include acceptance by the nephrology community of opinion-based clinical practice guidelines supporting earlier dialysis (18), more widespread automated eGFR reporting (37), provider preference for dialysis compared with other strategies for managing patients with advanced kidney disease (38,39), and provider belief in the benefit of preemptive dialysis (10,24). Slinin et al. found that earlier dialysis initiation was associated with several provider characteristics, including provider inexperience, foreign (outside the United States) medical training, a high- or low-density of nephrologists, and receipt of predialysis nephrology care (38). Prior work also demonstrates the importance of pragmatic factors in shaping dialysis treatment decisions, including patient/family preferences, distance to the dialysis facility, dietary or medication nonadherence, and the presence of a functioning fistula or graft (24,38). Collectively, these prior studies highlight the complexity and multifaceted nature of decisions about dialysis initiation in real-world clinical settings.

This study is the first to describe differences in dialysis timing among patients initiating within versus outside a large single-payer health system in the United States. We found systematic differences in eGFR at dialysis initiation based on setting and payer at the time of initiation. Observed differences in eGFR at initiation within versus outside the VA were of similar magnitude to within-system differences across the same time period, and probably translate into substantial differences in dialysis initiation timing (20). If anything, observed differences in timing of dialysis initiation within versus outside the VA became more sharply delineated over time. In the early 2000s, veterans who initiated outside the VA with dialysis paid for by the VA had a risk of starting at an eGFR≥10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 that was closest to that for veterans initiating within the VA, but by the late 2000s eGFR at initiation within this group more closely aligned with that for other groups initiating dialysis outside the VA. Collectively, our findings suggest that care structure and practices within an integrated health system may influence dialysis treatment decisions. The VA underwent substantial reengineering in the late 1990s to focus on universal primary care and prevention (40). This led to large improvements in the quality of care within the VA compared with the private sector across a broad range of quality measures (41). Differences between the VA and other United States health systems that may influence the timing of dialysis initiation include access to primary care and predialysis nephrology care; procedures for dialysis education and access evaluation; a central electronic medical record system that can facilitate communication and coordination across settings and providers; and perhaps differences in capacity for dialysis, palliative care services, or illness acuity at the time of dialysis initiation.

It is notable that the most pronounced differences in eGFR at initiation between different groups defined by dialysis setting and payer were observed among older patients and those with a higher mortality risk, groups for whom the benefits of initiation of long-term dialysis are least certain (3,21). Available evidence suggests that older adults have been disproportionately affected by trends toward earlier initiation of dialysis (20). Furthermore, there is often uncertainty about the likely benefit of long-term dialysis in older adults with a high burden of comorbidity (42). Survival on dialysis can be extremely limited at older ages (21), and small observational studies from the United Kingdom suggest that dialysis may not lengthen survival for those with a high degree of comorbidity compared with a more conservative approach (43,44). Among patients residing in a nursing home around the time of dialysis initiation, substantial functional decline often occurs after dialysis initiation (3), and older patients report a poorer quality of life on dialysis than do their younger counterparts (45). We suspect that the more pronounced differences in timing of dialysis initiation within versus outside the VA among older patients and those with higher 1-year mortality risk may be emblematic of broader differences in treatment practices for medically complex patients and those with limited life expectancy within versus outside the VA (46,47).

This study had several limitations. First, data were collected from the ESRD Medical Evidence report (CMS-2728), which may contain inaccurate information regarding medical history (48) and predialysis care (49). Second, there may be residual confounding by unmeasured factors that influence clinical decision making, especially because there are often systematic reasons that veterans initiate dialysis outside the VA, such as the urgency of their presentation (36). Future studies might address this limitation by collecting detailed information regarding the clinical context of dialysis initiation, including the trajectory of renal function before initiation (50). Finally, the generalizability of this study is limited to patients within the United States who survived long enough to be included in the USRDS registry.

Temporal trends in eGFR at dialysis initiation within the wider United States dialysis population were also present within a large single-payer health system within the United States. However, even after adjustment for patient characteristics, level of eGFR at initiation was markedly lower among patients who initiated dialysis within versus outside the VA. The most pronounced differences in eGFR at initiation within versus outside the VA were observed among older patients and those with higher mortality risk, groups for whom the benefits of dialysis are least certain. Collectively these findings suggest that health system factors may play a significant role in shaping decisions about dialysis initiation, especially in medically complex patients and those with limited life expectancy.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Pam Green for her data programming support in this project.

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research & Development Service, grant IIR 09-094 (P.L.H.). M.K.Y. was supported by the VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Health Services Research and Development and the American Kidney Fund’s Clinical Scientist in Nephrology Program. A.M.O., C.F.L., and P.L.H. receive research funding from the VA Health Services Research and Development Service. A.M.O. also receives research funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health and royalties from UpToDate.

None of the funding sources had any role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VA or the United States government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Timing of Dialysis Initiation—Do Health Care Setting or Provider Incentives Matter?,” on pages 1321–1323.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.12731214/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System: USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Insitute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watnick S, Kirwin P, Mahnensmith R, Concato J: The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 41: 105–110, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP, Jr, Hart LG, Blagg CR, Gutman RA, Hull AR, Lowrie EG: The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 312: 553–559, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merkus MP, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Boeschoten EW, Stevens P, Krediet RT, The Necosad Study Group : Quality of life in patients on chronic dialysis: Self-assessment 3 months after the start of treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 29: 584–592, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traynor JP, Simpson K, Geddes CC, Deighan CJ, Fox JG: Early initiation of dialysis fails to prolong survival in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2125–2132, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beddhu S, Samore MH, Roberts MS, Stoddard GJ, Ramkumar N, Pappas LM, Cheung AK: Impact of timing of initiation of dialysis on mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2305–2312, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kazmi WH, Gilbertson DT, Obrador GT, Guo H, Pereira BJ, Collins AJ, Kausz AT: Effect of comorbidity on the increased mortality associated with early initiation of dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 887–896, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiao CC, Huang JW, Chien KL, Chuang HF, Chen YM, Wu KD: Early initiation of dialysis and late implantation of catheters adversely affect outcomes of patients on chronic peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 28: 73–81, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosansky SJ, Clark WF, Eggers P, Glassock RJ: Initiation of dialysis at higher GFRs: Is the apparent rising tide of early dialysis harmful or helpful? Kidney Int 76: 257–261, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stel VS, Dekker FW, Ansell D, Augustijn H, Casino FG, Collart F, Finne P, Ioannidis GA, Salomone M, Traynor JP, Zurriaga O, Verrina E, Jager KJ: Residual renal function at the start of dialysis and clinical outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3175–3182, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark WF, Na Y, Rosansky SJ, Sontrop JM, Macnab JJ, Glassock RJ, Eggers PW, Jackson K, Moist L: Association between estimated glomerular filtration rate at initiation of dialysis and mortality. CMAJ 183: 47–53, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosansky SJ, Eggers P, Jackson K, Glassock R, Clark WF: Early start of hemodialysis may be harmful. Arch Intern Med 171: 396–403, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Susantitaphong P, Altamimi S, Ashkar M, Balk EM, Stel VS, Wright S, Jaber BL: GFR at initiation of dialysis and mortality in CKD: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 829–840, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crews DC, Scialla JJ, Liu J, Guo H, Bandeen-Roche K, Ephraim PL, Jaar BG, Sozio SM, Miskulin DC, Tangri N, Shafi T, Meyer KB, Wu AW, Powe NR, Boulware LE, Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness (DEcIDE) Patient Outcomes in End Stage Renal Disease Study Investigators : Predialysis health, dialysis timing, and outcomes among older United States adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 370–379, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright S, Klausner D, Baird B, Williams ME, Steinman T, Tang H, Ragasa R, Goldfarb-Rumyantzev AS: Timing of dialysis initiation and survival in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1828–1835, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris A, Cooper BA, Li JJ, Bulfone L, Branley P, Collins JF, Craig JC, Fraenkel MB, Johnson DW, Kesselhut J, Luxton G, Pilmore A, Rosevear M, Tiller DJ, Pollock CA, Harris DC: Cost-effectiveness of initiating dialysis early: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 707–715, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemodialysis Adequacy 2006 Work Group : Clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, update 2006. Am J Kidney Dis 48[Suppl 1]: S2–S90, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosansky SJ, Clark WF: Has the yearly increase in the renal replacement therapy population ended? J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1367–1370, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Hare AM, Choi AI, Boscardin WJ, Clinton WL, Zawadzki I, Hebert PL, Kurella Tamura M, Taylor L, Larson EB: Trends in timing of initiation of chronic dialysis in the United States. Arch Intern Med 171: 1663–1669, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, Chertow GM: Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med 146: 177–183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stel VS, Tomson C, Ansell D, Casino FG, Collart F, Finne P, Ioannidis GA, De Meester J, Salomone M, Traynor JP, Zurriaga O, Jager KJ: Level of renal function in patients starting dialysis: An ERA-EDTA Registry study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 3315–3325, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, Collins JF, Craig JC, Fraenkel MB, Harris A, Johnson DW, Kesselhut J, Li JJ, Luxton G, Pilmore A, Tiller DJ, Harris DC, Pollock CA, IDEAL Study : A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 363: 609–619, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Luijtgaarden MW, Noordzij M, Tomson C, Couchoud C, Cancarini G, Ansell D, Bos WJ, Dekker FW, Gorriz JL, Iatrou C, Garneata L, Wanner C, Cala S, Stojceva-Taneva O, Finne P, Stel VS, van Biesen W, Jager KJ: Factors influencing the decision to start renal replacement therapy: Results of a survey among European nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 60: 940–948, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES: Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Engl J Med 363: 45–53, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sirovich BE, Gottlieb DJ, Welch HG, Fisher ES: Variation in the tendency of primary care physicians to intervene. Arch Intern Med 165: 2252–2256, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Hare AM, Rodriguez RA, Hailpern SM, Larson EB, Kurella Tamura M: Regional variation in health care intensity and treatment practices for end-stage renal disease in older adults. JAMA 304: 180–186, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treit K, Lam D, O’Hare AM: Timing of dialysis initiation in the geriatric population: Toward a patient-centered approach. Semin Dial 26: 682–689, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veterans Health Administration: About VHA. Available at: http://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp Accessed April 9, 2014

- 30.Wright SM, Daley J, Fisher ES, Thibault GE: Where do elderly veterans obtain care for acute myocardial infarction: Department of Veterans Affairs or Medicare? Health Serv Res 31: 739–754, 1997 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen LA, Normand SL, Leape LL, McNeil BJ: Regionalization and the underuse of angiography in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System as compared with a fee-for-service system. N Engl J Med 348: 2209–2217, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trivedi AN, Matula S, Miake-Lye I, Glassman PA, Shekelle P, Asch S: Systematic review: Comparison of the quality of medical care in Veterans Affairs and non-Veterans Affairs settings. Med Care 49: 76–88, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Information Resource Center. Available at: http://www.virec.research.va.gov Accessed April 9, 2014

- 34.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration : Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 145: 247–254, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VHA Office of Rural Health : VHA Office of Rural Health Fact Sheet April 2013, Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Hare AM, Wong SP, Yu MK, Wynar B, Perkins M, Liu CF, Lemon JM, Hebert PL: Trends in timing and clinical context of maintenance dialysis initiation [published online ahead of print February 19, 2015]. J Am Soc Nephrol doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brimble KS, Mehrotra R, Tonelli M, Hawley CM, Castledine C, McDonald SP, Levidiotis V, Gangji AS, Treleaven DJ, Margetts PJ, Walsh M: Estimated GFR reporting influences recommendations for dialysis initiation. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1737–1742, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slinin Y, Guo H, Li S, Liu J, Morgan B, Ensrud K, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ, Ishani A: Provider and care characteristics associated with timing of dialysis initiation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 310–317, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosansky SJ: Early dialysis initiation, a look from the rearview mirror to what’s ahead. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 222–224, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kizer KW: The “new VA”: a national laboratory for health care quality management. Am J Med Qual 14: 3–20, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA: Effect of the transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the quality of care. N Engl J Med 348: 2218–2227, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE: Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1955–1962, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K: Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: Comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 1608–1614, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canaud B, Tong L, Tentori F, Akiba T, Karaboyas A, Gillespie B, Akizawa T, Pisoni RL, Bommer J, Port FK: Clinical practices and outcomes in elderly hemodialysis patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1651–1662, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, Davis RB, Phillips RS: Hospice use among Medicare managed care and fee-for-service patients dying with cancer. JAMA 289: 2238–2245, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, Earle CC, Bozeman SR, McNeil BJ: End-of-life care for older cancer patients in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector. Cancer 116: 3732–3739, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Layton JB, Hogan SL, Jennette CE, Kenderes B, Krisher J, Jennette JC, McClellan WM: Discrepancy between Medical Evidence Form 2728 and renal biopsy for glomerular diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2046–2052, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JP, Desai M, Chertow GM, Winkelmayer WC: Validation of reported predialysis nephrology care of older patients initiating dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1078–1085, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Hare AM, Batten A, Burrows NR, Pavkov ME, Taylor L, Gupta I, Todd-Stenberg J, Maynard C, Rodriguez RA, Murtagh FE, Larson EB, Williams DE: Trajectories of kidney function decline in the 2 years before initiation of long-term dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 513–522, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.