Abstract

HIV-1 interacts with numerous cellular proteins during viral replication. Identifying such host proteins and characterizing their roles in HIV-1 infection can deepen our understanding of the dynamic interplay between host and pathogen. We previously identified non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein (NonO or p54nrb) as one of host factors associated with catalytically active preintegration complexes (PIC) of HIV-1 in infected CD4+ T cells. NonO is involved in nuclear processes including transcriptional regulation and RNA splicing. Although NonO has been identified as an HIV-1 interactant in several recent studies, its role in HIV-1 replication has not been characterized. We investigated the effect of NonO on the HIV-1 life cycle in CD4+ T cell lines and primary CD4+ T cells using single-cycle and replication-competent HIV-1 infection assays. We observed that short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated stable NonO knockdown in a CD4+ Jurkat T cell line and primary CD4+ T cells did not affect cell viability or proliferation, but enhanced HIV-1 infection. The enhancement of HIV-1 infection in Jurkat T cells correlated with increased viral reverse transcription and gene expression. Knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat T cells modestly enhanced HIV-1 gag mRNA expression and Gag protein synthesis, suggesting that viral gene expression and RNA regulation are the predominantly affected events causing enhanced HIV-1 replication in NonO knockdown (KD) cells. Furthermore, overexpression of NonO in Jurkat T cells reduced HIV-1 single-cycle infection by 41% compared to control cells. Our data suggest that NonO negatively regulates HIV-1 infection in CD4+ T cells, albeit it has modest effects on early and late stages of the viral life cycle, highlighting the importance of host proteins associated with HIV-1 PIC in regulating viral replication.

Introduction

HIV-1 interacts with numerous host cellular proteins during viral replication, which are often subverted by HIV-1 to aid during steps of the replication cycle, including reverse transcription, nuclear import, integration, gene expression, virion assembly, and release.1 Contrary to this, many host factors aim to restrict HIV-1 replication at several stages through indirect or directs means. Several studies have attempted to identify and characterize host proteins2–5 required for efficient HIV-1 replication in an effort to understand HIV-1 and host cell interactions with the aim of developing novel therapeutic targets. One caveat of global screening methods is the lack of overlap in identified factors across independent studies due to differences in the experimental approach and cell lines used and off-target effects, often resulting in false-positive or false-negative results.3,6,7 Current research efforts are focused on validating these interactions utilizing cellular and biochemical models.

During HIV-1 replication large complexes are formed that facilitate replication processes, for example, the reverse transcription complexes (RTC) and preintegration complexes (PIC) are composed of viral and host proteins and viral RNA and DNA species. However, these complexes have not been thoroughly studied and the exact composition and function of all components are not well understood. Clear elucidation of these complex interactomes is ongoing in an effort to better understand HIV-1 and host interactions. The HIV-1 PIC is one of the major viral–host nucleoprotein complexes whose composition has yet to be fully elucidated. The PIC is composed of HIV-1 DNA and both viral and host proteins and it is thought to be derived from the RTC.8 Although they functionally differ, it is not clear whether the protein composition of the PIC and the RTC overlaps.

In our previous study, we utilized an affinity pull-down and mass spectrometry approach and identified 18 new host proteins specifically associated with catalytically active PICs isolated from HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cell lines.9 Non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein (NonO, also known as p54nrb) is one of these host proteins.9 Subsequent studies from other groups have also identified NonO as a component of HIV-1 RTC or as directly interacting with HIV-1 proteins. Proteomic analysis of fractions from HIV-1-infected T cell lines identified NonO as a component of HIV-1 RTC across seven repeat experiments.10 NonO was also shown to interact with several HIV-1 proteins (including integrase) ectopically expressed in HEK293 and Jurkat cells.11 Furthermore, NonO was identified in an analysis of the Rev interactome in HeLa cells, and the association between NonO and Rev was enhanced by the presence of the Rev response element.12 These studies suggest that NonO may affect multiple steps of the HIV-1 lifecycle including integration. However, the role of NonO in HIV-1 infection has not been clearly characterized.

NonO is a nuclear protein with known roles in transcriptional regulation and RNA splicing.13,14 It is homologous to polypyrimidine tract-binding protein-associated splicing factor (PSF) and often acts in concert with PSF, forming a heterodimer.15 NonO is unique regarding its structure and function as it contains both RNA recognition motifs to bind RNA16–18 and interacts with RNA polymerase II.19 NonO also contains DNA recognition domains,16,20 which are thought to facilitate the recruitment of transcription factors to their respective response elements, and NonO has been shown to increase the binding activities of several transcription factors such as OTF-1, OTF-2, and E47.21 Overall, these studies suggest a role for NonO in transcriptional regulation; one mechanism through which this has been demonstrated is the retention of adenosine- to inosine-edited RNAs in the nucleus.22 Many other cellular functions of NonO are associated with RNA splicing. For example, NonO is a component of paraspeckles and it interacts with pre-mRNA by binding to U5 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) and binds to a 5′ splice site within transcription/splicing complexes.13,17,18,20,23,24

Despite many studies regarding NonO's cellular function, the role of NonO in HIV-1 infection is unknown. A previous study reported that PSF and NonO interact with the HIV-1 gag cis-acting instability elements (INS) and that overexpression of PSF, but not NonO, inhibits HIV-1 Gag p24 production in transfected HEK293 cells.25 This study suggests that PSF and NonO may regulate HIV-1 mRNA production causing diminished HIV-1 gag–pol and env gene expression.25 NonO has also been shown to form a complex with PSF and participate in the nonhomologous end-joining pathway, capable of DNA double-strand break rejoining.26 We thus speculated that NonO might have a role in the assembly of PICs and integration of the HIV-1 genome into the host chromosome.9

In this study, we examined the role of NonO in HIV-1 infection of CD4+ T cells by silencing or overexpressing NonO protein. We analyzed the early and late stages of the HIV-1 replication cycle in order to determine the stage of the replication cycle on which NonO had an effect. We found that NonO knockdown (KD) in CD4+ Jurkat T cells enhanced HIV-1 infection by promoting viral reverse transcription and gene expression. We also confirmed that NonO KD in primary CD4+ T cells also increased HIV-1 infection. Our data suggest that endogenous NonO protein expression negatively regulates HIV infection in CD4+ T cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and isolation of primary CD4+ T cells

HEK293T, GHOSTX4/R5, and Jurkat cell lines were kind gifts from Dr. Vineet KewalRamani (National Cancer Institute) and were maintained in specific media as previously described.27–31 Primary CD4+ T cells were isolated from healthy blood donors' buffy coats (purchased from American Red Cross Blood Service, Columbus, OH) using a negative selection kit (RosetteSep Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail, STEMCELL Technologies) and the purity of the cells was determined by flow cytometry for CD4. Isolated CD4+ T cells were maintained in complete RPMI media containing interleukin-2 (20 U/ml, Peprotech).

Lentivirus-mediated knockdown of NonO in Jurkat cells and primary CD4+ T cells

Lentivirus vectors for the short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of NonO were generated by calcium phosphate-based cotransfection of HEK293T cells with a NonO-specific shRNA-expressing GFP lentiviral vector pGIPZ (V3LHS_646457, mature antisense: TTGAGAAACTAGACACTGC, OpenBiosystems) together with a packaging vector (psPAX2) and a vesicular stomatitis virus G protein-expressing vector (pVSV-G, gifts from Paul Spearman, Emory University). Two days posttransfection, lentivirus-containing supernatants were harvested, centrifuged to remove cellular debris, and filtered with a 0.45-μm filter. Lentivirus stocks were then spinoculated into Jurkat cells by centrifugation at 2,000×g for 2 h at room temperature in the presence of 10 μg/ml polybrene (Fisher Scientific), adapted from O'Doherty et al.32 Cells were then resuspended and grown in normal RPMI media for 2 days, after which transduced cells were selected by puromycin (1 μg/ml). Puromycin-selected cell populations were expanded and the top 10% GFP expressing cells were sorted by fluorescent automated cell sorting and further expanded for 2 weeks as stable cell populations. A nonsilencing control vector (RHS4346, Open Biosystems) was also used to generate control stable Jurkat cells.

Primary CD4+ T cells were activated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA, 5 μg/ml) for 3 days prior to transduction with lentiviral vectors as described above. At 3 days posttransduction, cells were briefly selected with puromycin (0.5 μg/ml) for a further 3 days. After selection, cells were either lysed for immunoblotting or infected with single cycle HIV-1 as described below.

Immunoblotting

To confirm knockdown of NonO protein expression, Jurkat control and NonO KD cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling) and lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using a monoclonal mouse anti-NonO antibody (Abcam, ab13164). Immunoblotting of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control.

Cell proliferation and viability assays

Cell growth and proliferation of control and NonO KD cells were determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assays. Cells (1×104) were plated in triplicate in a 96-well plate and cultured for 3 days. MTS reagent (CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay, Promega) was added to wells and incubated for an hour. The absorbance was read at 490 nm at 0, 1, 2, and 3 day time points. Cell viability assays were conducted by cell counting and using trypan blue to exclude dead cells. GraphPad Prism 5 software was used to determine 95% confidence intervals to analyze any statistical variance between cell lines.

HIV-1 stocks and viral infection assays

Single-cycle, luciferase reporter HIV-1 stocks were generated by calcium phosphate-based transfection of HEK293T cells with the pNL-Luc-E–R+ proviral DNA vector (kindly provided by Dr. Nathanial Landau), together with pVSV-G. Replication-competent HIV-1NL4-3 was generated by transfection of HEK293T cells with pNL4-3. The p24 level in all replication HIV-1NL4-3 stocks was determined using a p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.) and the infectivity of each virus stock, represented as the infectious unit titer, was determined by limiting the dilution on HIV-1 indicator GHOST/R5 cells as previously described.33

For infections with single-cycle luciferase reporter HIV-Luc/VSV-G, Jurkat cells (2.5×105) were infected at an MOI of 0.5, or as indicated, for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were washed twice in RPMI media and cultured for the time period indicated. Lysates were harvested in the Reporter Lysis buffer (Promega) and HIV-1 infection was determined by luciferase assay. Replication-competent HIV-1NL4-3 infection was performed with 2.5×105 Jurkat cells infected with 10 ng of p24. Infections proceeded for a period of up to 4 days. Cell-associated Gag p24 production and Gag p24 released into the culture supernatant during the infection period were assessed by ELISA as previously described.34 Azidothymidine (AZT)-treated cells were pretreated with 10 μM AZT for 30 min prior to infection and AZT was present for the duration of the infection.

Quantitative PCR analysis of HIV-1 DNA

Levels of late reverse transcription products, two-long terminal repeat (2-LTR) circles, and integrated copies of provirus in infected Jurkat cells were quantified by Taqman-based real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis.35 Genomic DNA (50 ng) from HIV-1-infected Jurkat cells was used as input for the detection of HIV-1 early and late reverse transcription products, and 150–250 ng for the detection of 2-LTR circles and integrated proviral DNA. Plasmid DNA was used to generate standard curves for all qPCR steps. GAPDH was used to ensure equal loading of samples for qPCR.35 All virus stocks were treated with DNase I (40 U/ml; Ambion) prior to infections to avoid plasmid DNA contamination. DNA from infected cells was isolated using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen).

Quantitative RT-PCR detection of HIV-1 gag mRNA

Jurkat cells were infected with either single-cycle or replication-competent HIV-1 as described above and harvested on day 2 (for single-cycle HIV-1) and day 3 (for replication-competent HIV-1) postinfection. Total cellular RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini kit (Invitrogen), and 300 ng of RNA was used as template for first strand cDNA synthesis using a Superscript III first-strand synthesis kit and oligo(dT) primers (Invitrogen). On column DNase I digestion was also performed using an RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen). Sybergreen-based real-time PCR analysis was performed using gag-specific primers35 to quantify the levels of HIV-1 gag mRNA copies in infected cells as described.28 Serial dilutions of the pNLAD8 plasmid were used as the standard for the gag-specific PCR. Amplification of gapdh mRNA was also performed for each sample to normalize for the amount of input cDNA in each reaction.

Overexpression of NonO in Jurkat cells

Parental Jurkat cells were nucelofected using the Lonza nucleofector system, according to the manufacturer's instructions, with a FLAG-tagged NonO-expressing construct (pF-54, Addgene Plasmid #35379) or an empty vector control. At 24 h postnucleofection, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by immunoblotting using a FLAG-specific antibody (Sigma). The remaining viable cells were then infected with single-cycle HIV-1 as described above.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis of CD4 cell surface expression on control and NonO KD-stable Jurkat cells was performed by staining cells with PE-conjugated antibodies to human CD4 (Invitrogen MHCD0404) or CXCR4 (BD Pharmingen 555974) and compared to isotype control antibody (BD Pharmingen 555749 and 555574)-stained cells. Flow cytometry was completed using a Guava EasyCyte Mini and data analysis was performed using FlowJo software.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the unpaired Student's t test, one-way ANOVA, and Dunnetts's correction or the Mann–Whitney test in GraphPad Prism 5 as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

Stable knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat cells does not affect cell viability or proliferation

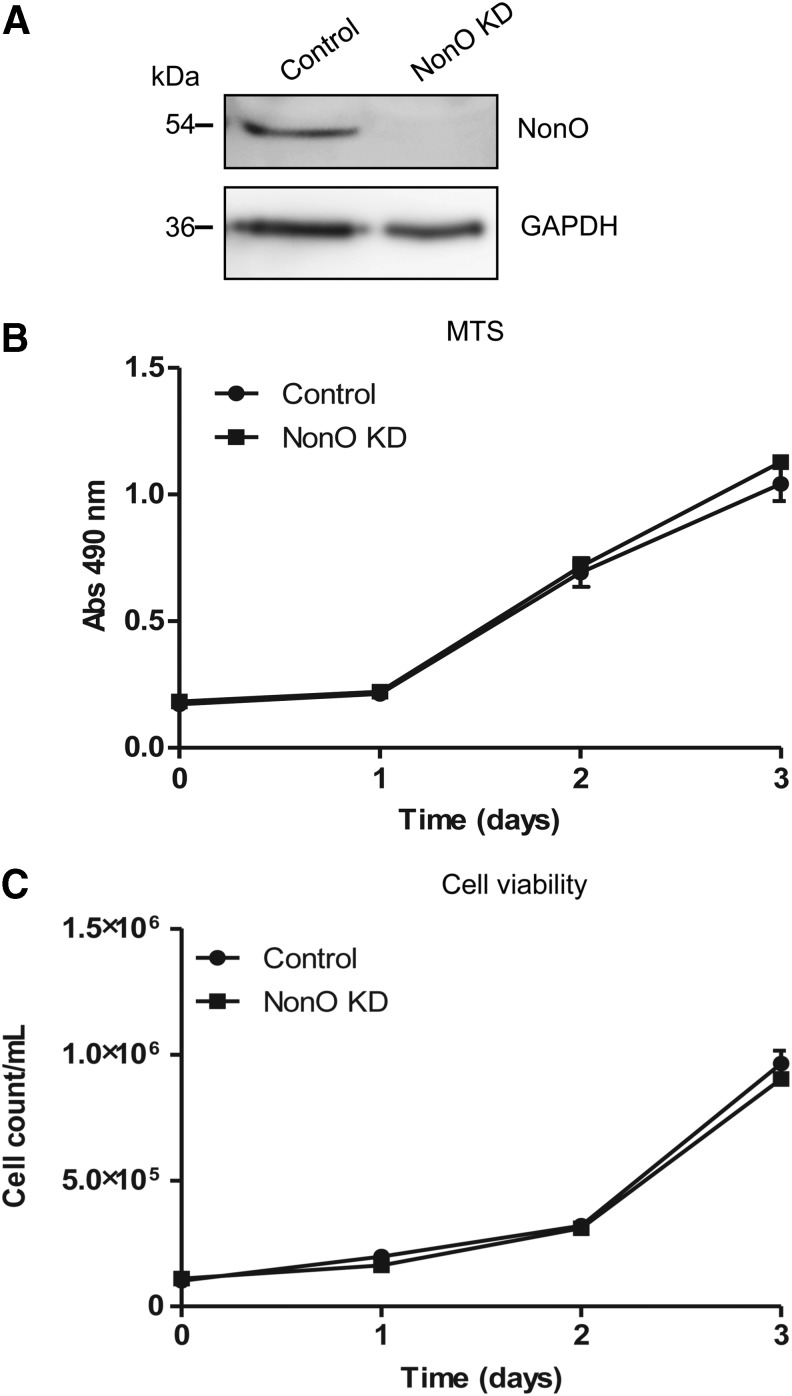

We previously identified NonO protein interacting with catalytically active HIV-1 PIC in CD4+ T cell lines.9 To determine the significance of this interaction for HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T cells, we generated a stable NonO KD Jurkat cell line and a nonsilencing shRNA control cell line using lentiviral shRNA vectors. To confirm efficient shRNA KD of NonO, we analyzed NonO protein expression in the KD cells and the control stable cells. Immunoblotting of NonO demonstrated a specific band at 54 kDa in the control cells and the KD cells had undetectable protein levels, confirming efficient KD of endogenous NonO protein (Fig. 1A). Given NonO's role in multiple cellular processes such as transcriptional regulation, it was important to determine the effect of NonO KD on cell viability and proliferation. We utilized a colorimetric MTS assay to measure the cell growth over a period of 3 days. This timeframe corresponded to the duration of subsequent HIV-1 infection experiments. The results showed no difference in cell growth between the control and KD cells for 3 days, indicating that knockdown of NonO did not affect cell proliferation (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Stable knockdown (KD) of NonO expression in Jurkat cells does not affect cell viability or proliferation. (A) Stable Jurkat cell lines expressing either nonsilencing short hairpin RNA (shRNA) (control) or NonO-specific shRNA KD (NonO KD) were generated by lentiviral transduction followed by puromycin selection. Cells were sorted and the top 10% GFP-expressing cell population was isolated and expanded for further experiments. Knockdown of NonO expression, compared to control cells, was verified by immunoblotting of 20-μg cell lysate with a specific antibody to NonO. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. (B) Proliferation and (C) cell viability assays of stable Jurkat cell lines. Control or NonO KD cells were seeded in 96-well plates (104 cells/well) and cultured for a total of 3 days. At the times indicated, cell proliferation was measured using an MTS assay reagent, or cell viability was determined using trypan blue counting. Error bars show standard deviation (SD) of (n= 9) from three independent experiments.

To determine the cell viability and doubling time, trypan blue staining and cell counting were performed. In agreement with the MTS assay, the cell viability counts for control and KD cells were comparable, confirming that NonO KD did not affect cell viability (Fig. 1C). Data from the cell viability assay were used to calculate doubling times of the cell lines, which were found to be similar and were not statistically significant (95% confidence interval: control cells=0.65–0.89, NonO KD cells=0.66–0.87). Together, these results confirmed that stable knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat cells does not affect cell viability or proliferation within the time period tested.

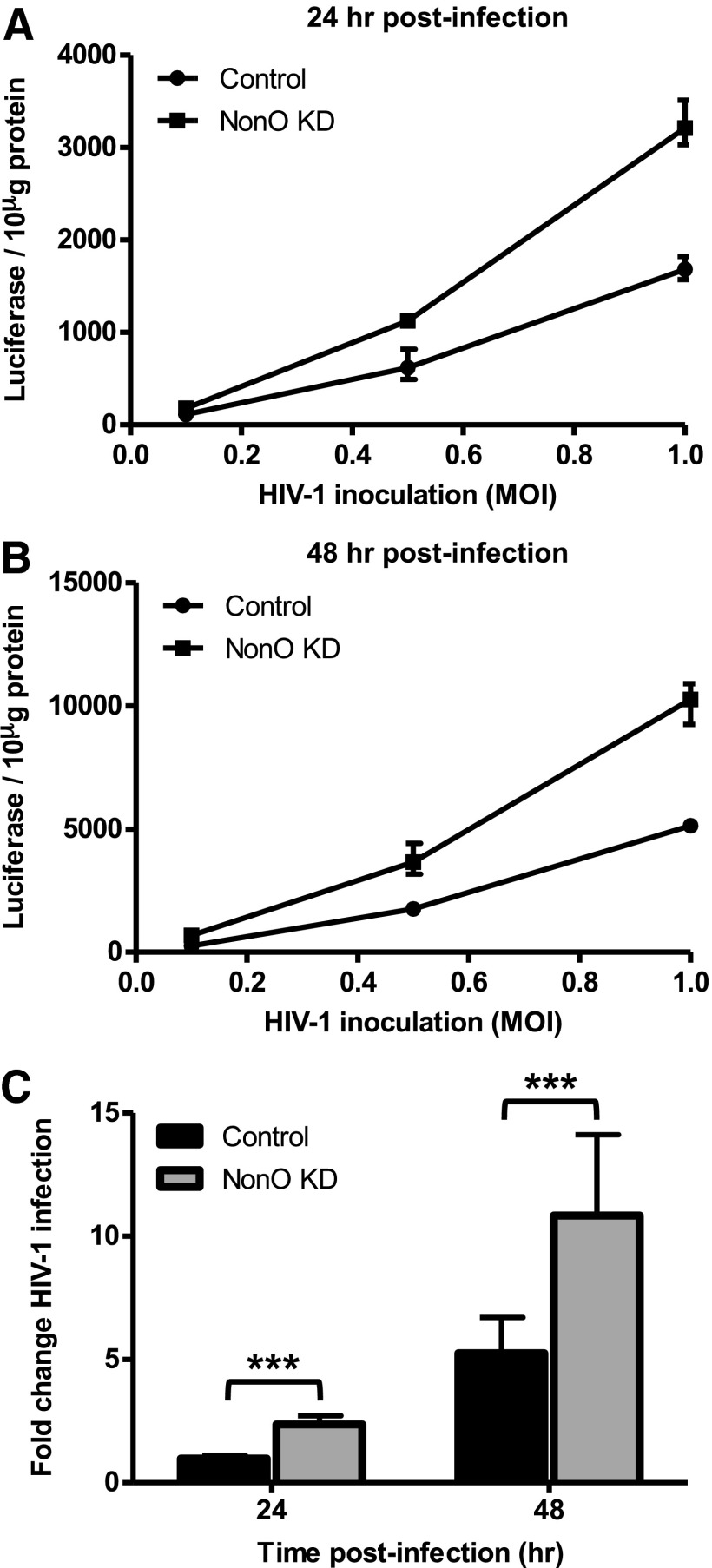

Knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat cells enhances single-cycle HIV-1 infection

To evaluate whether silencing NonO expression in Jurkat cells affects HIV-1 infection, we used a single-cycle HIV-1 luciferase reporter pseudotyped with a vesicular stomatitis virus envelope protein (HIV-Luc/VSV-G) to assess postentry HIV-1 infection. We first tested a range of HIV-1 multiplicity of infection (MOI of 0.1, 0.5, and 1) and found that NonO KD cells exhibited a 1.6-, 1.8-, and 1.9-fold increase in HIV-1 infection over control cells at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 2A). Similar results were observed at 48 h postinfection with a 2.6-, 2.1-, and 2-fold enhancement in HIV-1 infection in NonO KD cells versus control cells (Fig. 2B). A summary of five independent experiments of HIV-1 infection performed at an MOI of 0.5 demonstrated on average a 2.4-fold (p=0.0001) and a 1.9-fold increase in HIV-1 infection in NonO KD cells compared to control cells at 24 h and 48 h postinfection, respectively (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that NonO can negatively regulate postentry HIV-1 infection in the CD4+ Jurkat T cell line.

FIG. 2.

Knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat cells enhances single-cycle HIV-1 infection. (A, B) Single-cycle HIV-1 infection of control and NonO KD Jurkat cells. Jurkat cells were infected with single-cycle vesicular stomatitis virus G protein expressing vector (pVSV-G) pseudotyped HIV-1 at a range of MOIs: 0.1, 0.5, and 1. Cell pellets were harvested at (A) 24 h or (B) 48 h postinfection and lysed in reporter lysis buffer and HIV-1 infection determined by luciferase activity. Error bars represent the range of triplicate samples. (C) Control and NonO KD Jurkat cells were infected with single cycle VSV-G pseudotyped virus at an MOI of 0.5. Cell pellets were harvested at 24 or 48 h postinfection and lysed in reporter lysis buffer and HIV-1 infection determined by luciferase activity. Luciferase values were normalized to 10 μg protein and fold changes were calculated to the HIV-1 control cells, which were set as 1. Data in (C) represent a summary of five independent experiments and error bars represent SD (n=15). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

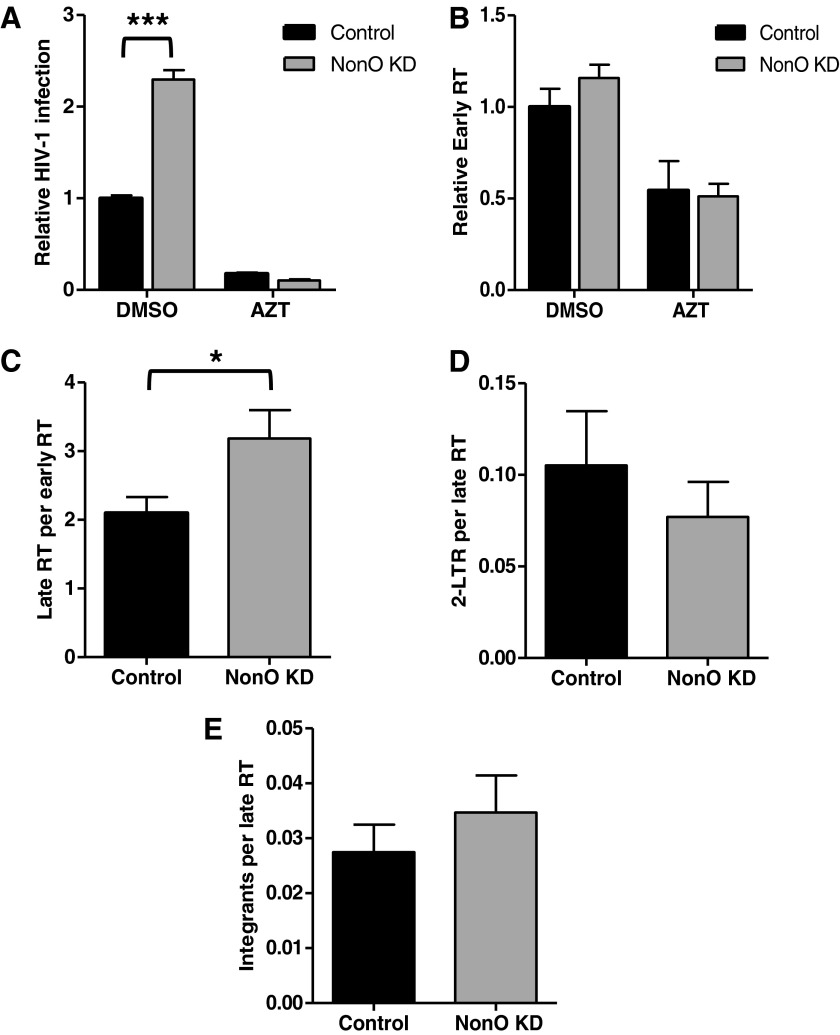

Knockdown of NonO expression enhances early stages of HIV-1 replication in Jurkat cells

Given the interactions of NonO with HIV-1 RTC and PIC and its cellular functions including DNA/RNA binding and transcriptional regulation, we hypothesized that NonO may affect an early stage of HIV-1 replication. To determine at which stage of the HIV-1 life cycle NonO affects HIV-1 infection, we used single-cycle HIV-Luc/VSV-G to infect control and NonO KD Jurkat cells and measured the HIV-1 DNA products by qPCR assays.35,36 Using genomic DNA isolated from HIV-Luc/VSV-G-infected cells at 24 h postinfection, we measured early and late reverse transcription (RT) products, 2-LTR circles, and integration products (Fig. 3). The integration-defective 2-LTR circles were used as a surrogate marker for nuclear import of HIV-1 cDNA.37

FIG. 3.

Knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat cells increases early stages of HIV-1 replication. Control and NonO KD Jurkat cells were infected with single-cycle HIV-Luc/VSV-G at an MOI of 0.5. (A) Cell pellets harvested at 24 h postinfection were lysed and HIV-1 infection determined by luciferase activity. A duplicate infection was used to harvest cell pellets for DNA isolation and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). (B) To determine HIV-1 early reverse transcription (RT) levels, cellular GAPDH was used to normalize raw data and relative early RT levels were calculated to HIV-1-infected control cells, which were set as 1. (C) Late RT levels were normalized to early RT levels. (D) Two-long terminal repeat (2-LTR) circles and (E) integration products were normalized to late RT products. Cells treated with azidothymidine (AZT) (5 μM) were used as a negative control. Data represent a summary of four independent experiments (n=12). Mean values±standard error of the mean are shown. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

The results of four independent experiments showed that relative HIV-1 infection increased 2.3-fold in NonO KD cells compared to control cells (p=0.0001) (Fig. 3A). To better compare the qPCR data between the infected cell lines, HIV-1 early RT levels were normalized to cellular GAPDH levels and subsequent processes (late RT, 2-LTR circles, and integration products) were normalized to the preceding step to compensate for any change in one-step filtering to downstream steps. The normalized qPCR results are shown (Fig. 3B–E). As a negative control, treatment of NonO KD and control cells with the RT inhibitor azidothymidine (AZT) prior to HIV-1 infection significantly diminished HIV-1 infection and early RT products (2- to 5-fold reduction, p<0.0001, Fig. 3A and B). In NonO KD cells, HIV-1 early RT products did not significantly increase (1.16-fold) compared to the control cells (p=0.2138) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the number of late RT products produced relative to early RT products significantly increased 1.52-fold (p=0.0355) (Fig. 3C). Quantification of 2-LTR circles (Fig. 3D) and HIV-1 integration products relative to the late RT levels did not show a statistically significant difference in NonO KD and control cells (Fig. 3E). Together, these results suggest that enhanced HIV-1 single-cycle infection in NonO-silenced Jurkat cells corresponds to modestly increased viral late reverse transcription.

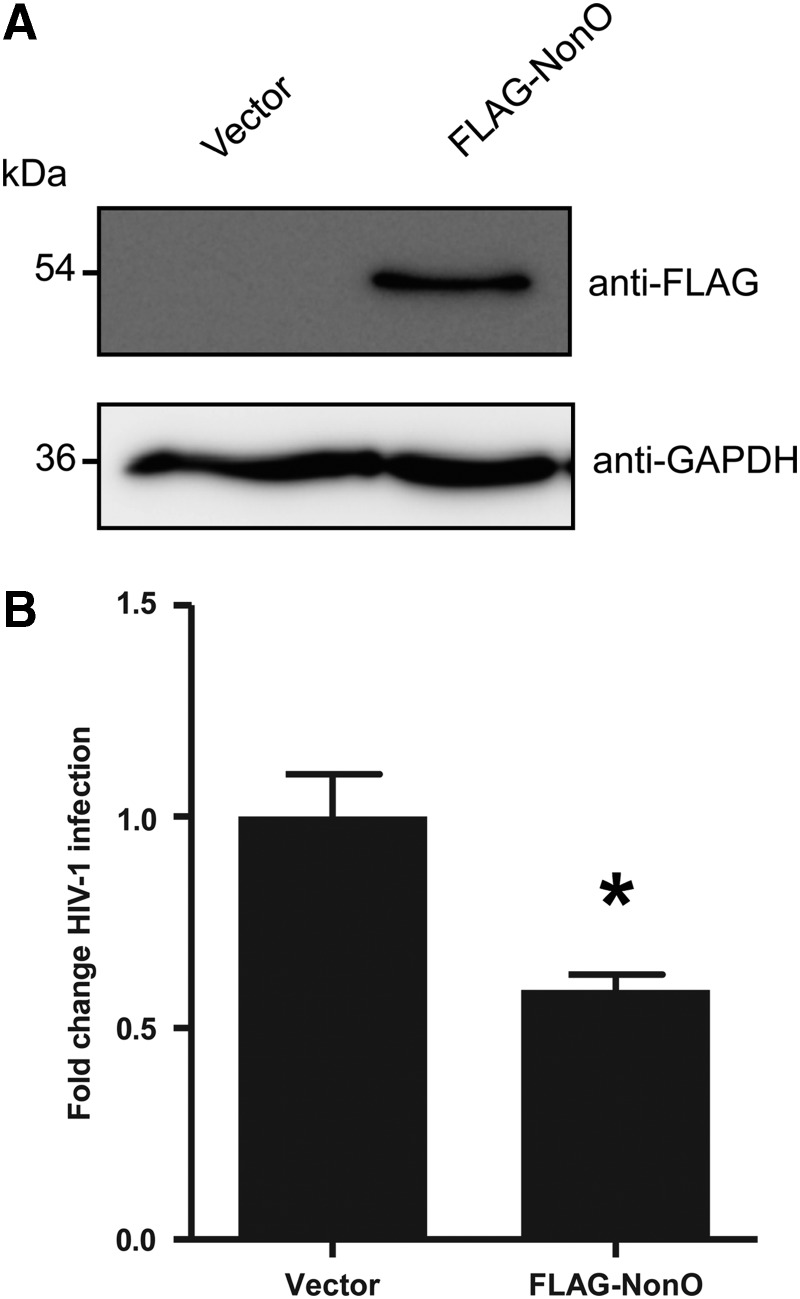

Overexpression of NonO in Jurkat cells reduces single-cycle HIV-1 infection

The above results suggest that endogenous NonO in Jurkat cells can negatively regulate postentry HIV-1 infection. To examine whether overexpression of NonO would negatively regulate HIV-1 infection, we nucleofected a FLAG-tagged NonO-expressing construct38 into Jurkat cells and determined the effect on postentry HIV-1 infection. Immunoblotting analysis confirmed overexpression of the FLAG-NonO protein in Jurkat cells at 24 h postnucleofection (Fig. 4A). Single-cycle HIV-Luc/VSV-G infection results demonstrated that overexpression of NonO reduced HIV-1 infection by 41% (p=0.0165) at 24 h postinfection (Fig. 4B). This result suggests that overexpression of NonO protein in Jurkat cells can partially suppress postentry HIV-1 infection.

FIG. 4.

Overexpression of NonO in Jurkat cells reduces HIV-1 infection. (A) Jurkat cells were nucleofected with either an empty vector or a FLAG-tagged NonO mammalian expression construct. Twenty-four hours postnucleofection cell lysates were harvested and 10 μg protein lysate analyzed by immunoblotting to confirm overexpression of NonO using a FLAG-specific antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Nucleofected Jurkat cells were subjected to single-cycle HIV-1 infection. Cell lysates were harvested and HIV-1 infection was determined using a luciferase assay at 24 h postinfection. Luciferase values were normalized to 10 μg protein, and all values were calculated relative to the control cells, which were set as 1. Data shown represent a summary of three independent experiments; error bars represent SD (n=9). *p<0.05.

Knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat cells enhances HIV-1 Gag production

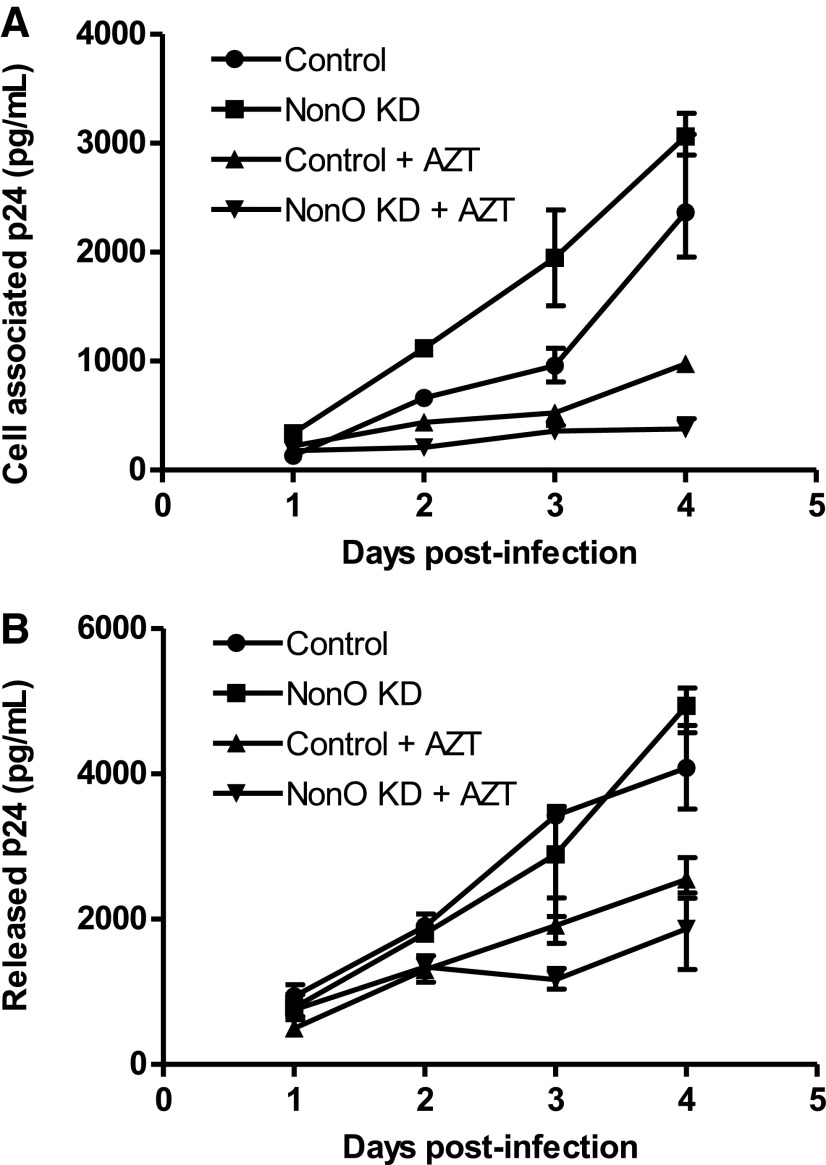

Our results obtained with single-cycle HIV-1 indicated that NonO negatively affects HIV-1 infection primarily at late reverse transcription. To investigate potential effects of NonO during a spreading HIV-1 infection, we used an X4-tropic replication-competent HIV-1NL4-3 to infect NonO KD and control cell lines. To eliminate the possibility that differences in HIV-1 replication were the result of altered cell surface expression of HIV-1 receptors on NonO KD cells, cell surface expression of the HIV-1 receptor CD4 or the coreceptor CXCR4 on both control and NonO KD Jurkat cells was determined by flow cytometry using specific antibodies. Both stable cell lines were found to express comparable and high levels of CD4 and CXCR4 (>95% positive and >90% positive, respectively, data not shown). After replication-competent HIV-1 infection, cell pellets and supernatants were collected over a period of 4 days postinfection for HIV-1 Gag p24 quantification. Compared to control cells, cell-associated HIV-1 Gag in NonO KD cells was significantly increased from 1.7- to 2.5-fold at days 1–3 postinfection (Fig. 5A). AZT treatment efficiently reduced HIV-1 p24 production throughout the course of infection (Fig. 5A). A summary of three independent experiments demonstrated an average of 1.5- to 2.6-fold increase in HIV-1 p24 production in NonO KD cells compared to control cells at 1–4 days postinfection (figure not shown). We then measured the release of Gag p24 in the supernatants from infected cells and observed no significant change in KD cells compared to control cells over 4 days postinfection and AZT treatment partially reduced HIV-1 p24 release (Fig. 5B). Overall, these results suggest that silencing NonO in Jurkat cells may slightly enhance HIV-1 Gag production in infected cells, but does not seem to affect Gag release and maturation.

FIG. 5.

Knockdown of NonO expression in Jurkat cells enhances HIV-1 Gag production. (A) Replication-competent HIV-1NL4-3 was used to infect control or NonO KD stable Jurkat cells. Cells (2.5×105) were infected at an equivalent MOI of 0.5 for 2 h. Cells were then washed and replated in fresh media and cultured for a total of 4 days. At the time points indicated supernatants were collected, clarified, and lysed in 1% Triton X-100; cells pellets were washed and also lysed in 1% Triton X-100. Lysate cells and supernatants were analyzed by p24 ELISA for (A) cell-associated p24 or (B) supernatant p24. Cells treated with AZT (5 μM) were used as a positive control. Data shown represent one of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the range of triplicate samples.

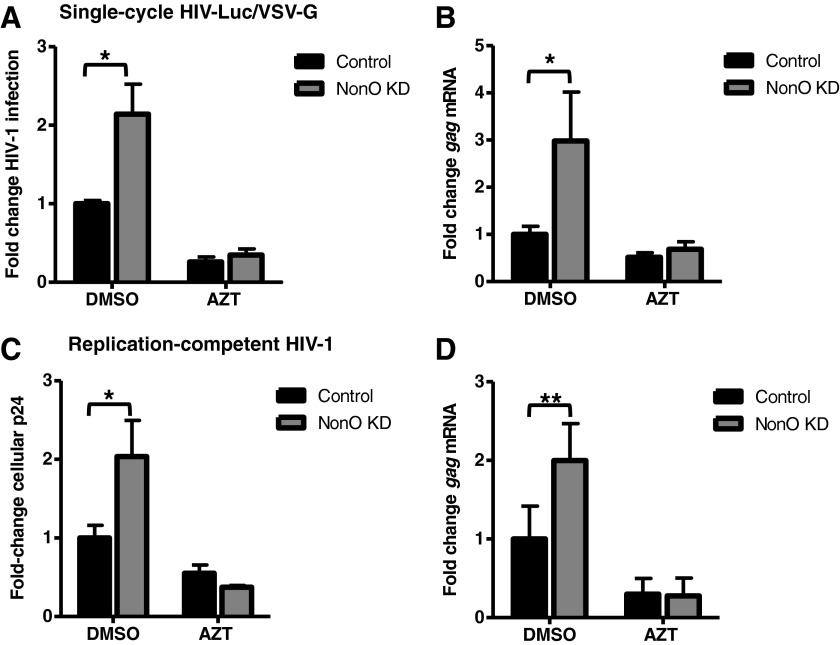

Knockdown of NonO increases gag mRNA expression in HIV-1-infected Jurkat cells

We questioned whether the increase in HIV-1 gene expression and cellular Gag p24 protein in NonO KD cells correlated with increased viral gene transcription. To address this question, we measured HIV-1 gag mRNA from either single-cycle or replication-competent HIV-1-infected NonO KD and control Jurkat cells by qPCR. We quantified HIV-1 gag mRNA levels at 2 and 3 days postinfection for the single-cycle and the replication-competent infection, respectively. This is because peak infection of CD4+ T cell lines with single-cycle and replication-competent HIV-1 occurred at these particular time points.28 Compared to control cells, NonO KD cells demonstrated a 2.1-fold increase (p=0.01) in single-cycle HIV-1 infection (Fig. 6A) and a 3-fold increase (p=0.019) in gag mRNA expression (Fig. 6B). Analysis of replication-competent HIV-1 infection showed a 2-fold (p=0.02) increase in Gag p24 production (Fig. 6C) and a 2-fold (p=0.0087) enhancement of gag mRNA levels in NonO KD cells compared to control cells (Fig. 6D). As a positive control, treatment of infected Jurkat cells with AZT diminished the differences between NonO KD and control cells (Fig. 6A–D). These results combined with the results in Figs. 2 and 3 suggest that although NonO KD modestly enhances HIV-1 late reverse transcription (1.52-fold), we observed a stronger effect of NonO KD on HIV-1 gene expression and protein production, causing increased viral gene expression (up to 3-fold) and Gag p24 production (up to 2.6-fold) in infected Jurkat cells.

FIG. 6.

Knockdown of NonO increases gag mRNA expression in HIV-1-infected Jurkat cells. (A) Single-cycle HIV-1 was used to infect control or NonO KD Jurkat cells. Two days postinfection lysates were harvested and HIV-1 infection was determined using a luciferase assay. Luciferase values were normalized to 10 μg protein, and all values were calculated relative to the control cells, which were set as 1. (B) Cells from a duplicate single-cycle HIV-1 infection were used to isolate total RNA. Oligo(dT) primers were used to generate cDNA and gag mRNA levels were quantified by qPCR using gag-specific primers. All qPCR input was normalized to gapdh. (C) Replication-competent HIV-1NL4-3 was used to infect control or NonO KD stable Jurkat cells. Cells (2.5×105) were infected at an equivalent MOI of 0.5 for 2 h. Cells were then washed and replated in fresh media and cultured for a total of 3 days. Cell-associated gag p24 was quantified by ELISA using lysates from infected cells. (D) A parallel infection to (C) was performed and RNA was isolated and qPCR performed as described in (B). Cells treated with 5 μM AZT were used as a negative control. Fold changes were calculated according to the control cells, which were set to 1. All data shown represent a summary of two representative independent experiments. Error bars represent SD (n=6). Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney test. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

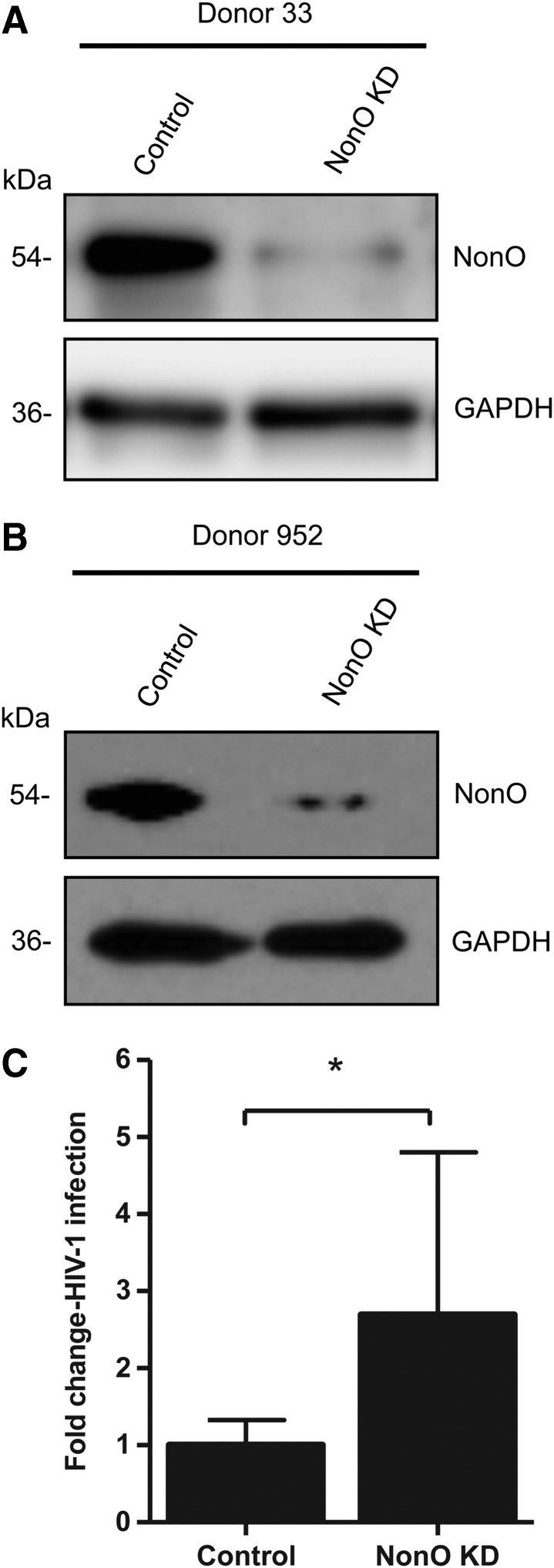

Knockdown of NonO enhances HIV-1 infection in activated primary CD4+ T cells

To determine the importance of NonO expression for HIV-1 infection in primary CD4+ T cells, we isolated primary CD4+ T cells from healthy donors and silenced NonO protein expression in activated CD4+ T cells using shRNA. Immunoblotting of cell lysates demonstrated that we successfully diminished NonO protein expression in primary CD4+ T cells from two separate donors, compared to nonsilenced control cells (Fig. 7A and B). Similar to Jurkat cells, we did not observe significant cytotoxicity after shRNA-mediated NonO knockdown in primary CD4+ T cells. Single-cycle HIV-1 infection of NonO KD primary CD4+ T cells from three different donors showed a trend of enhanced HIV-1 infection compared to control cells, which demonstrated an average of 2.7-fold (p=0.0163) enhancement in HIV-1 infection (Fig. 7C). These data are consistent with our observations in a NonO silenced Jurkat T cell line, confirming a role for NonO in moderately suppressing HIV-1 infection in primary CD4+ T cells.

FIG. 7.

Knockdown of NonO in primary CD4+ T cells modestly enhances HIV-1 infection. (A, B) Primary CD4+ T cells were isolated from healthy donor's blood and activated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 5 μg/ml). Activated CD4+ T cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors containing either NonO silencing shRNA or a nonsilencing control. At 3 days posttransduction, cells were briefly selected with puromycin for 3 days. Cell lysates were harvested and 5 μg protein lysate was analyzed by immunoblotting to confirm KD of NonO. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) Transduced CD4+ T cells were infected with single-cycle HIV-luc/VSV-G at an MOI of 0.5 for 3 days. HIV-1 infection was determined using a luciferase assay; luciferase values were normalized to 10 μg protein, and all values were calculated relative to the control cells, which were set as 1. Data show average results derived from three different donors' CD4+ T cells (n=11) and error bars represent SD. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's unpaired t test. *p<0.05.

Discussion

NonO is a mammalian protein that has been characterized as possessing a multitude of cellular functions in transcriptional regulation. We initially identified NonO interacting with PICs in HIV-1-infected CD4+ T cell lines,9 and subsequent studies have also identified NonO to be an HIV-1 interactant.10–12 However, the significance of these interactions and whether NonO plays a crucial role in HIV-1 infection have not been answered. We addressed these questions by investigating the effect of NonO KD on HIV-1 infection and characterized what stages of the replication cycle were affected. Our data suggest that NonO can play a role in late reverse transcription of HIV-1 replication in Jurkat cells, wherein its endogenous expression has a negative impact on HIV-1 infection. Furthermore, our data suggest that NonO acts primarily at late stages of replication, affecting HIV-1 gene expression and viral protein production.

While NonO is not essential for HIV-1 infection, our data suggest that downregulation of NonO expression allows for moderately enhanced HIV-1 late reverse transcription. It is possible that NonO regulates viral reverse transcription through its association with the RTC and PIC, either directly or by modulation of required components for the process; alternatively, NonO could interact with HIV-1 mRNA. However, we also observed an additional effect of silencing NonO at late stages of HIV-1 infection where gag mRNA and Gag production were enhanced, suggesting an additional role in modulating viral gene expression. However, despite enhanced cellular Gag production we did not observe enhanced Gag release and maturation, suggesting either that enhanced Gag production was not sufficient to subsequently enhance Gag release or that NonO's effect at later stages of HIV-1 replication may not be the primary function of NonO. Further evidence suggesting the inhibitory role of NonO during HIV-1 infection is provided from overexpression experiments in which exogenous NonO was able to reduce HIV-1 infection in a Jurkat T cell line. Silencing of NonO in Jurkat cells had a more prominent effect in enhancing HIV-1 infection (2.4-fold) than overexpressing NonO to reduce HIV-1 infection; this could be attributed to a limitation of overexpressing high levels of NonO in Jurkat cells.

There are numerous host factors that may interact directly or indirectly with viral components during HIV-1 replication.39,40 Many of these interactions occur at early stages of replication resulting in abortive substrates, modification or degradation of viral cDNA, or induction of an innate immune response. As NonO was identified interacting with the HIV-1 PIC, we initially hypothesized that NonO would exert a predominant effect at integration. However, given the potential similarity and close association between the RTC and PIC, it is conceivable that NonO is able to affect viral reverse transcription. The nature of the association between NonO and the PIC remains to be investigated as it is not known if the interaction is indirect or occurs directly through integrase. Interestingly, integrase has been shown to associate with RTCs as the viral DNA is generated and traffics through the cytoplasm and then converts to the PIC (reviewed in Wu et al.41). Furthermore, integrase mutants have been found to affect proviral DNA synthesis,42,43 presumably as a result of their interaction with the RTC. It is possible that NonO acts as a component of the RTC and negatively affects HIV-1 reverse transcription through its DNA and RNA binding motifs.

NonO has many roles in cellular functions such as transcriptional regulation and splicing, though little is known about the mechanism in these processes and the effect on HIV-1 replication. The only study investigating NonO in HIV-1 gene expression found that the INS of HIV-1 gag assembled with PSF and NonO in nuclear extracts of cells, hinting at a possible role at later stages of HIV-1 infection.25 However, only overexpression of PSF inhibited INS mRNA expression and extracellular Gag production in HEK293 cells.25

As suggested, it is possible that the endogenous level of NonO in HEK293 cells is saturating and consequently no further effect was observed upon its overexpression. However, our data suggest that NonO not only negatively regulates HIV-1 reverse transcription, but also affects viral gene expression, as evidenced by increased HIV-1 gag mRNA expression and cell-associated p24 production in NonO KD cells. It is possible that these changes in the late events of the HIV-1 lifecycle were a downstream effect of changes in reverse transcription. Furthermore, while we analyzed early stages of replication encompassing reverse transcription during HIV-1 infection, the previous study examined only transcriptional regulation of transfected proviral DNA, omitting the reverse transcription step during viral replication.25 It is possible that NonO regulates viral reverse transcription through its association with the RTC and PIC, either directly or by modulation of required components for the process; alternatively, NonO could interact with HIV-1 mRNA.

The effect of NonO silencing on HIV-1 infection in Jurkat cells observed in this study was small in magnitude, although statistically significant. It is possible that PSF, a known interactor with NonO, would also need to be silenced to observe an optimal effect on HIV-1 infection. Previous studies investigating NonO/PSF functions have found that analyzing each one alone often yields a weak effect.44,45 Furthermore, the effect we observed may also be lower due to incomplete depletion of NonO in the Jurkat or primary CD4+ T cells, or there may be some redundancy with PSF.46 As PSF was not one of the proteins identified interacting with the PIC, we did not pursue silencing of PSF experiments in this study.

NonO is well established as a multifunctional protein that is mainly involved in nuclear processes, although there is evidence it has an export signal and has been observed in the cytoplasm.25 Given the multiple cellular functions of NonO, it is likely that variable effects of NonO could arise from its association with different functional protein complexes and posttranslational modifications.47,48 Knockdown NonO in active primary CD4+ T cells resulted in an approximately 2- to 4.5-fold enhancement of HIV-1 infection, corresponding to NonO silencing in the cells.

In conclusion, we found that knockdown of endogenous NonO in CD4+ T cell lines and primary CD4+ T cells enhanced HIV-1 infection, while overexpression of exogenous NonO in a Jurkat T cell line reduced viral infection. The enhanced HIV-1 infection by NonO silencing in the Jurkat T cell line appears to be an initial effect through promoting HIV-1 reverse transcription and subsequently enhanced viral gene expression. Overall, our results suggest that NonO has a role in negatively regulating HIV-1 infection in CD4+ T cells. Further clarification of the host proteins involved in HIV-1 nucleoprotein complexes can result in a better understanding of HIV-1 replication and identify potential targets for therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Nathanial Landau, Paul Spearman, and Vineet KewalRamani for reagents. We thank Heather Hoy for technical assistance, Dr. Suresh de Silva for critical reading of the manuscript, and the Wu laboratory for helpful discussions. AZT was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent. This work was supported by NIH grant AI102822 to L.W. C.S. and L.W. are supported in part by NIH grant AI104483 to L.W. L.W. is also supported in part by the Public Health Preparedness for Infectious Diseases Program of The Ohio State University.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Goff SP: Host factors exploited by retroviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007;5:253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, et al. : Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science 2008;319:921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushman FD, Malani N, Fernandes J, et al. : Host cell factors in HIV replication: Meta-analysis of genome-wide studies. PLoS Path 2009;5:e1000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konig R, Zhou Y, Elleder D, et al. : Global analysis of host-pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell 2008;135:49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou H, Xu M, Huang Q, et al. : Genome-scale RNAi screen for host factors required for HIV replication. Cell Host Microbe 2008;4:495–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao L, He Q, Wang Z, et al. : Limited agreement of independent RNAi screens for virus-required host genes owes more to false-negative than false-positive factors. PLoS Comp Biol 2013;9:e1003235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pache L, Konig R, and Chanda SK: Identifying HIV-1 host cell factors by genome-scale RNAi screening. Methods 2011;53:3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matreyek KA. and Engelman A: Viral and cellular requirements for the nuclear entry of retroviral preintegration nucleoprotein complexes. Viruses 2013;5:2483–2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghavendra NK, Shkriabai N, Graham R, et al. : Identification of host proteins associated with HIV-1 preintegration complexes isolated from infected CD4+cells. Retrovirology 2010;7:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schweitzer CJ, Jagadish T, Haverland N, et al. : Proteomic analysis of early HIV-1 nucleoprotein complexes. J Proteome Res 2013;12:559–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jager S, Cimermancic P, Gulbahce N, et al. : Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature 2012;481:365–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naji S, Ambrus G, Cimermancic P, et al. : Host cell interactome of HIV-1 Rev includes RNA helicases involved in multiple facets of virus production. Mol Cell Proteom 2012;11:M111 015313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreger M, Bengtsson L, Schoneberg T, et al. : Nuclear envelope proteomics: Novel integral membrane proteins of the inner nuclear membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:11943–11948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen JS, Lyon CE, Fox AH, et al. : Directed proteomic analysis of the human nucleolus. Curr Biol 2002;12:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang WW, Zhang LX, Busch RK, et al. : Purification and characterization of a DNA-binding heterodimer of 52 and 100 kDa from HeLa cells. Biochem J 1993;290(Pt 1):267–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang YS, Hanke JH, Carayannopoulos L, et al. : (1993) NonO, a non-POU-domain-containing, octamer-binding protein, is the mammalian homolog of Drosophila nonAdiss. Mol Cell Biol 1993;13:5593–5603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu A, Dong B, Krainer AR, and Howe CC: The intracisternal A-particle proximal enhancer-binding protein activates transcription and is identical to the RNA- and DNA-binding protein p54nrb/NonO. Mol Cell Biol 1997;17:677–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallier M, Tavitian A, and Moreau-Gachelin F: The transcription factor Spi-1/PU.1 binds RNA and interferes with the RNA-binding protein p54nrb. J Biol Chem 1996;271:11177–11181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emili A, Shales M, McCracken S, et al. : Splicing and transcription-associated proteins PSF and p54nrb/nonO bind to the RNA polymerase II CTD. RNA 2002;8:1102–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong B, Horowitz DS, Kobayashi R, and Krainer AR: Purification and cDNA cloning of HeLa cell p54nrb, a nuclear protein with two RNA recognition motifs and extensive homology to human splicing factor PSF and Drosophila NONA/BJ6. Nucl Acids Res 1993;21:4085–4092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang YS, Yang MC, Tucker PW, and Capra JD: NonO enhances the association of many DNA-binding proteins to their targets. Nucl Acids Res 1997;25:2284–2292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z. and Carmichael GG: The fate of dsRNA in the nucleus: A p54(nrb)-containing complex mediates the nuclear retention of promiscuously A-to-I edited RNAs. Cell 2001;106:465–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marko M, Leichter M, Patrinou-Georgoula M, and Guialis A: hnRNP M interacts with PSF and p54(nrb) and co-localizes within defined nuclear structures. Exp Cell Res 2010;316:390–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng R, Dye BT, Perez I,et al. : PSF and p54nrb bind a conserved stem in U5 snRNA. RNA 2002:8:1334–1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zolotukhin AS, Michalowski D, Bear J,et al. : PSF acts through the human immunodeficiency Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:6618–6630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bladen CL, Udayakumar D, Takeda Y, and Dynan WS: Identification of the polypyrimidine tract binding protein-associated splicing factor.p54(nrb) complex as a candidate DNA double-strand break rejoining factor. J Biol Chem 2005;280:5205–5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Silva S, Hoy H, Hake TS, et al. : Promoter methylation regulates SAMHD1 gene expression in human CD4+T cells. J Biol Chem 2013;288:9284–9292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Silva S, Planelles V, and Wu L: Differential effects of Vpr on single-cycle and spreading HIV-1 infections in CD4+T-cells and dendritic cells. PLoS One 2012;7:e35385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.St Gelais C, Coleman CM, Wang J-H, and Wu L: HIV-1 nef enhances dendritic cell-mediated viral transmission to CD4(+) T cells and promotes T-cell activation. PLoS One 2012;7:e34521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu L, Martin TD, Carrington M, and KewalRamani VN: Raji B cells, misidentified as THP-1 cells, stimulate DC-SIGN-mediated HIV transmission. Virology 2004;318:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu L, Martin TD, Vazeux R, et al. : Functional evaluation of DC-SIGN monoclonal antibodies reveals DC-SIGN interactions with ICAM-3 do not promote human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission. J Virol 2002;76:5905–5914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Doherty U, Swiggard WJ, and Malim MH: Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 spinoculation enhances infection through virus binding. J Virol 2000;74:10074–10080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janas AM. and Wu L: HIV-1 interactions with cells: From viral binding to cell-cell transmission. Curr Protocols Cell Biol 2009;Chapter 26:Unit 26.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang JH, Janas AM, Olson WJ, et al. : CD4 coexpression regulates DC-SIGN-mediated transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 2007;81:2497–2507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong C, Janas AM, Wang JH, et al. : Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in immature and mature dendritic cells reveals dissociable cis- and trans-infection. J Virol 2007;81:11352–11362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llano M, Saenz DT, Meehan A, et al. : An essential role for LEDGF/p75 in HIV integration. Science 2006;314:461–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bukrinsky MI, Sharova N, Dempsey MP, et al. : Active nuclear import of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 preintegration complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:6580–6584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosonina E, Ip JY, Calarco JA, et al. : Role for PSF in mediating transcriptional activator-dependent stimulation of pre-mRNA processing in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:6734–6746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lama J. and Planelles V: Host factors influencing susceptibility to HIV infection and AIDS progression. Retrovirology 2007;4:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strebel K: HIV accessory proteins versus host restriction factors. Curr Opin Virol 2013;3:692–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandegraaff N. and Engelman A: Molecular mechanisms of HIV integration and therapeutic intervention. Expert Rev Mol Med 2007;9:1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu X, Liu H, Xiao H, et al. : Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase protein promotes reverse transcription through specific interactions with the nucleoprotein reverse transcription complex. J Virol 1999;73:2126–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engelman A, Englund G, Orenstein JM, et al. : Multiple effects of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase on viral replication. J Virol 1995;69:2729–2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King HA, Cobbold LC, Pichon X, et al. : Remodelling of a polypyrimidine tract-binding protein complex during apoptosis activates cellular IRESs. Cell Death Differ 2014;21:161–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Izumi H, McCloskey A, Shinmyozu K, and Ohno M: p54nrb/NonO and PSF promote U snRNA nuclear export by accelerating its export complex assembly. Nucl Acids Res 2014;42:3998– 400.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li S, Kuhne WW, Kulharya A, et al. : Involvement of p54(nrb), a PSF partner protein, in DNA double-strand break repair and radioresistance. Nucl Acids Res 2009;37:6746–6753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otto H, Dreger M, Bengtsson L, and Hucho F: Identification of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins associated with the nuclear envelope. Eur J Biochem/FEBS 2001;268:420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Proteau A, Blier S, Albert AL, et al. : The multifunctional nuclear protein p54nrb is multiphosphorylated in mitosis and interacts with the mitotic regulator Pin1. J Mol Biol 2005;346:1163–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]