Summary

Microbes play an important role in the pathogenesis of nutritional disorders such as protein-specific malnutrition. However, the precise contribution of microbes to host energy balance during undernutrition is unclear. Here, we show that Issatchenkia orientalis, a fungal microbe isolated from field-caught Drosophila melanogaster, promotes amino acid harvest to rescue the lifespan of undernourished flies. Using radioisotope-labeled dietary components (amino acids, nucleotides, and sucrose) to quantify nutrient transfer from food to microbe to fly, we demonstrate that I. orientalis extracts amino acids directly from nutrient-poor diets and increases protein flux to the fly. This microbial association restores body mass, protein, glycerol, and ATP levels and phenocopies the metabolic profile of adequately fed flies. Our study uncovers amino acid harvest as a fundamental mechanism linking microbial and host metabolism, and highlights Drosophila as a platform for quantitative studies of host-microbe relationships.

Introduction

Recent studies have emphasized the importance of gut microbes in the regulation of energy balance and the development of metabolic disease (Cho and Blaser, 2012; Cox and Blaser, 2013; Krajmalnik-Brown et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2013; Subramanian et al., 2014). However, our understanding of the mechanisms shaping these metabolic interactions remains incomplete. Host-microbe relationships may have evolved to harvest energy from the diet and improve fitness during food shortage (Ley et al., 2008; Wichmann et al., 2013). Microbial energy extraction is evident from studies showing that axenic rodents have lower levels of intestinal short-chain fatty acids, reduced adiposity, and greater excretion of calories (Flint et al., 2012; Turnbaugh et al., 2006). Nonetheless, studies defining how microbes facilitate nutrient assimilation and affect host metabolism are likely hindered by the complex functional interactions between microbes and host—particularly in mammals.

Dietary changes can have major effects on microbial composition, energy harvest and host health (David et al., 2014). Specifically, hyper-caloric or high-fat diets can select for microbes that exacerbate obesity (Jumpertz et al., 2011; Turnbaugh et al., 2009). Similarly, protein-deficient diets also shape the microbial community and contribute to a severe form of protein-specific undernutrition, kwashiorkor (Smith et al., 2013). While dietary interventions may be the most feasible method to re-establish host metabolic homeostasis, existing nutritional therapies have not considered variations in microbial metabolism and have not been successful as long-term treatments (Smith et al., 2013). A better understanding of microbial metabolism, and the nutrient flux between microbes and host, is key to developing probiotic interventions that persistently alleviate nutritional imbalances.

The Drosophila system offers a simplified model for defining the mechanisms underlying symbiotic host-microbe interactions (Bakula, 1969; Broderick and Lemaitre, 2012; Brummel et al., 2004; Chandler et al., 2011; Douglas, 2011; Erkosar et al., 2013). In both humans and flies, bacterial communities shift with changes in host nutrition (Chandler et al., 2011; David et al., 2014) and age (Claesson et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2011). Using Drosophila, we have developed a quantitative assay to show how microbes mediate amino acid flux from diet to host. Our findings highlight the utility of this simplified model system for characterizing the role of microbes in affecting host metabolism, using experimental designs that are difficult to implement in mammals.

Results

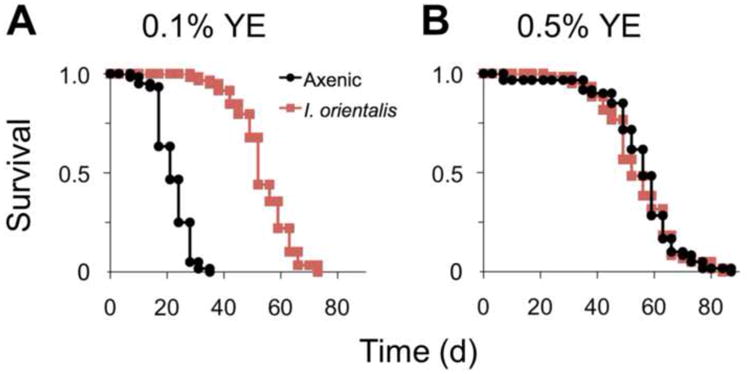

Microbial association extends lifespan during undernutrition

Feeding flies diets that are low in yeast can model protein-specific undernutrition and severely shorten lifespan (Bruce et al., 2013; Ja et al., 2009; Katewa et al., 2012; Zid et al., 2009). In this study, we asked whether microbial association could rescue the effect of protein deficiency. Since Drosophila may have adapted to nutrient shortage in the wild, we sought to acquire microbes naturally associated with flies and hence more likely to complement fly fitness. We established isofemale lines from field-caught Drosophila melanogaster. Bacterial and fungal species were identified by ribosomal RNA gene sequencing of distinct colonies cultured from fly homogenates. We identified Issatchenkia orientalis (yeast), and Lactobacillus plantarum (bacteria) as the predominant microbes from field-caught flies. In agreement with previous findings (Chandler et al., 2011), we also identified many bacterial strains of the Acetobacter genus, and used Acetobacter indonesiensis as a representative strain in this study. Similarly, Saccharomyces cerevisiae was selected as a conventional yeast associated with laboratory flies. To determine microbe-specific effects on fly physiology and lifespan, axenic (germ-free) animals were inoculated with a single dose of live microbes to produce monoxenic flies (associated with a single microbial species). On a protein-deficient diet (0.1% yeast extract, YE), I. orientalis association extended median lifespan by 148% over the axenic control (p = 3.2 × 10−13, Fisher's exact test, Figure 1A). In contrast, fly lifespan was unaffected by I. orientalis association on 0.5% YE food (Figure 1B), suggesting that at an optimal dietary yeast concentration, I. orientalis has no additive effect on lifespan. S. cerevisiae and A. indonesiensis association also extended median lifespan (67% and 114% respectively) over the axenic control (p < 5.4 × 10−13, Fisher's exact test, Figure S1A), but to a lesser extent than I. orientalis. The change in median lifespan was even less with L. plantarum association (33%, p = 0.0040, Fisher's exact test, Figure S1A). Since I. orientalis consistently showed the greatest benefit to fly lifespan in other independent trials (Figure S1B), we focused on I. orientalis for subsequent studies.

Figure 1. I. orientalis extends fly lifespan on undernutrition diet.

(A) Survival of axenic or I. orientalis-associated monoxenic flies on 0.1% yeast extract (YE) diet. I. orientalis association increases survival compared to the axenic control (p < 10−10, log-rank test). (B) Survival on 0.5% YE diet. Survival curves of I. orientalis-associated and axenic flies do not differ (p > 0.090, log-rank test). Monoxenic flies were inoculated once as adults with I. orientalis. N = 59–61 flies for each condition. See also Figure S1.

We next asked whether lifelong I. orientalis association is necessary to extend fly lifespan. We manipulated I. orientalis growth using methylparaben, a commonly used food preservative (Ashburner et al., 2005). Methylparaben effectively eliminated I. orientalis in the fly environment (Figure S1C) and also abolished lifespan extension in flies fed 0.1% YE food (Figure S1D). Neither methylparaben nor I. orientalis affected fly lifespan on 0.5% YE food (Figures 1B and S1E). Hence, a persistent microbial presence is likely needed to rescue longevity during undernutrition.

Since a single inoculation with live I. orientalis is sufficient to rescue lifespan, we hypothesized that, once inoculated, the fly host can maintain an adequate supply of I. orientalis within the nutritional environment to benefit health throughout life. To support this idea, we measured I. orientalis populations at two time points during a fly lifespan trial. Microbial load in whole fly homogenates is maintained at both ages (Figure S1F). No difference in microbe count was observed between whole fly and dissected gut (Figure S1G), suggesting that the majority of fly-associated I. orientalis resides within the digestive tract. Interestingly, counts of I. orientalis in the environment were consistently higher than microbe numbers from fly homogenates (cf. Figures S1F and S1H). Since flies are transferred to axenic medium every few days during lifespan trials, our results suggest that flies inoculate their food with live I. orientalis upon each passage. Indeed, fly-free microbial growth confirmed that I. orientalis can grow independently on the medium (Figure S1I). Importantly, daily transfer of flies to fresh axenic medium leads to loss of fly-associated I. orientalis (Figure S1J). Collectively, our findings suggest that maintenance of I. orientalis is a synergistic process requiring live microbes to be passaged using the fly host as a vector, and microbial growth in the environment constantly resupplies the transiently colonized I. orientalis in the fly gut. These results are consistent with previous studies reporting that husbandry practices are key to shaping the adult fly microbiota (Blum et al., 2013; Broderick et al., 2014).

I. orientalis harvests dietary amino acids and enhances protein flux to the fly

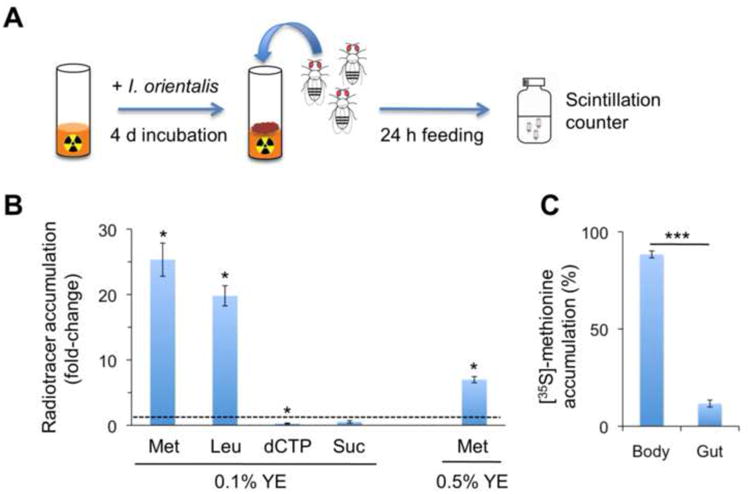

The influence of I. orientalis and higher YE diets is not additive (Figures 1A and 1B), suggesting that I. orientalis and YE function identically to rescue undernutrition through nutrient provision. We hypothesized that I. orientalis directly harvests protein from the diet for the fly host. In mammals, microbial energy harvest has been indirectly examined through either metabolic markers, such as short-chain fatty acids, or caloric excretion (Turnbaugh et al., 2006). To directly determine the flux of other nutrients, we monitored the transfer of radioisotope-labeled dietary components (amino acids, nucleotides and sucrose) from food to microbe to fly (Figure 2A) (Deshpande et al., 2014).

Figure 2. I. orientalis increases amino acid harvest in Drosophila.

(A) Radioisotope-labeled feeding assay for examining nutrient accumulation in the fly. Flies feed for 24 h on radiolabeled food that is pre-inoculated with I. orientalis. Radioisotope abundance in the fly is then measured to reveal the effect of microbial association on nutrient accumulation. (B) Effect of I. orientalis association on fly accumulation of radiolabeled nutrients on 0.1% or 0.5% YE medium. Results (average ± s.d.) are normalized to the axenic control (dashed line) for each radioactive tracer. Significant differences between each tracer and its axenic control are shown (Mann-Whitney rank-sum test: *, p < 0.05). N = 4 vials of 10 flies for each condition. Met = [35S]-methionine; Leu = [14C]-leucine; dCTP = [α-32P]-dCTP; Suc = [14C]-sucrose. (C) Distribution of accumulated [35S]-methionine in flies. After 24 h feeding on [35S]-methionine-labeled 0.1% YE medium that is pre-inoculated with I. orientalis, the entire fly digestive tract is dissected and 35S is quantitated from the gut and remaining fly carcass. Results (average ± s.d.) are shown as a percentage of [35S]-methionine accumulation. Student's t-test: ***, p < 0.001. N = 4 samples of 2 flies each. See also Figure S2.

I. orientalis was inoculated onto 0.1% YE food supplemented with [35S]-methionine, [14C]-leucine, [14C]-sucrose or [α–32P]-dCTP. We then measured radiolabel accumulation in flies that were fed axenic or microbe-inoculated food for 24 h. In the presence of I. orientalis, flies accumulated over 20-fold more [35S]-methionine and [14C]-leucine compared to axenic controls (Figure 2B). To ensure that radioisotope accumulation is representative of nutrient assimilation rather than a measure of undigested radiolabeled microbes in the fly gut, the complete digestive tract was dissected. Dissected guts contained only ∼10% of consumed [35S]-methionine, while the remaining fly carcass contained ∼90%, suggesting that consumed amino acids are incorporated into the fly body (Figure 2C). Hence, I. orientalis association increases accumulation of diet-derived amino acids in fly tissues.

To determine whether I. orientalis increases the flux of amino acids to the fly by directly harvesting them from the diet, microbes from spent vials were collected and radioactive tracers were measured (Figure S2A). Consistent with fly radiolabel accumulation, microbial suspensions contained more [35S]-methionine and [14C]-leucine compared to axenic controls, while the increase in [14C]-sucrose and [α–32P]-dCTP levels was less marked, demonstrating the efficient uptake of amino acids by I. orientalis (Figure S2B). In contrast, S. cerevisiae did not accumulate [35S]-methionine (0.92 ± 0.25 fold-change over axenic, p = 0.56, Student's t-test). I. orientalis also accumulated [35S]-methionine on 0.5% YE food, although the enrichment of amino acid in both microbe and fly was far less than on the 0.1% YE diet (Figures 2B and S2B). Collectively, our findings suggest that I. orientalis extracts and concentrates amino acids from food substrates—perhaps more efficiently than other strains—under low protein conditions. This leads to increased amino acid flux to the fly upon consumption, which is critical in conditions where protein is scarce.

To rule out the possibility that I. orientalis increases nutrient accumulation by simply altering feeding behavior, we measured total food intake using the radioisotope-labeling method (Deshpande et al., 2014). I. orientalis association had no effect on feeding rate (Figure S2C). We also measured total food intake using an independent assay that does not rely on medium labeling to rule out caveats of label dynamics. The capillary feeder (CAFE) assay allowed us to limit food surfaces available for microbial growth and likely minimized fly consumption of live microbes from the environment (Ja et al., 2007). Our results confirmed that I. orientalis association had no effect on feeding rate (Figure S2D), supporting the idea that, under low protein conditions, I. orientalis directly serves as a nutrient source.

Microbial association during undernutrition rescues metabolism to phenocopy adequately fed flies

If I. orientalis serves as a nutrient source for undernourished flies, we would expect host metabolic phenotypes to match that of adequately fed animals. We measured a variety of metabolic parameters in axenic and I. orientalis-associated flies maintained on 0.1% or 0.5% YE. Consistent with the minimal effect on lifespan, microbial association did not affect any physiological measures on the 0.5% YE diet (Figure S3). In contrast, I. orientalis association with undernourished flies (0.1% YE) mimicked the effect of increased dietary YE, represented by increased protein, glycerol, and ATP and reduced glucose and triglyceride levels (Figure S3). The effect of I. orientalis on metabolites is consistent with a recent study showing that conventional microbe-associated flies have decreased glucose and triglyceride levels compared with axenic flies (Newell and Douglas, 2014).

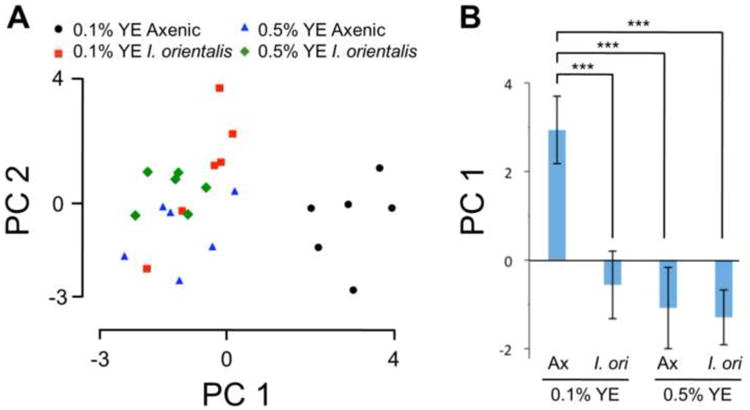

We next performed a principal component analysis (PCA) to determine how flies in each condition cluster and are thus most similar. PCA revealed that I. orientalis-associated flies on the 0.1% YE diet are more closely related to flies on the 0.5% YE diets, regardless of microbial association, than to axenic animals on 0.1% YE food (Figure 3A). PC1 scores show a strong negative correlation with median lifespan (Pearson's r = -0.99, p = 0.013). Accordingly, axenic flies on 0.1% YE diet show significantly higher PC1 scores compared with flies from the remaining three conditions (Figure 3B). PC1 is negatively loaded with body mass, protein, glycerol and ATP while positively loaded with glucose and triglycerides (Figure 3A). Except for body mass, which showed the expected trend but without statistical significance, PC1 highlights the metabolic measurements that were significantly different between axenic and I. orientalis-associated flies maintained on 0.1% YE (Figure S3). These results show that I. orientalis induces a change in fly physiology and metabolic state that reproduces the effect of increased dietary YE.

Figure 3. Principal component analysis of metabolic parameters from axenic and I. orientalis-associated flies maintained on 0.1% YE and 0.5% YE diets.

(A) Plot of PC1 and PC2 scores, which account for 45% and 28% of the total variance, respectively. The metabolic state of I. orientalis-associated flies on 0.1% YE medium more closely resembles that of animals on higher YE diet (0.5% YE) than that of undernourished axenic flies. Loadings for PC1 and PC2, respectively: body mass, −0.452 and −0.146; protein, −0.419 and 0.233; glucose, 0.452 and 0.255; glycogen, 0.066 and 0.592; trehalose, 0.103 and 0.556; glycerol, −0.323 and 0.423; TAG, 0.274 and −0.145; ATP, −0.471 and 0.008. (B) PC1 scores (average ± s.d.) from (A). Significant differences are shown (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-test for multiple comparisons: ***, p < 0.001). N = 6 for each condition. Abbreviations: Ax, axenic; I. ori, I. orientalis. See also Figure S3.

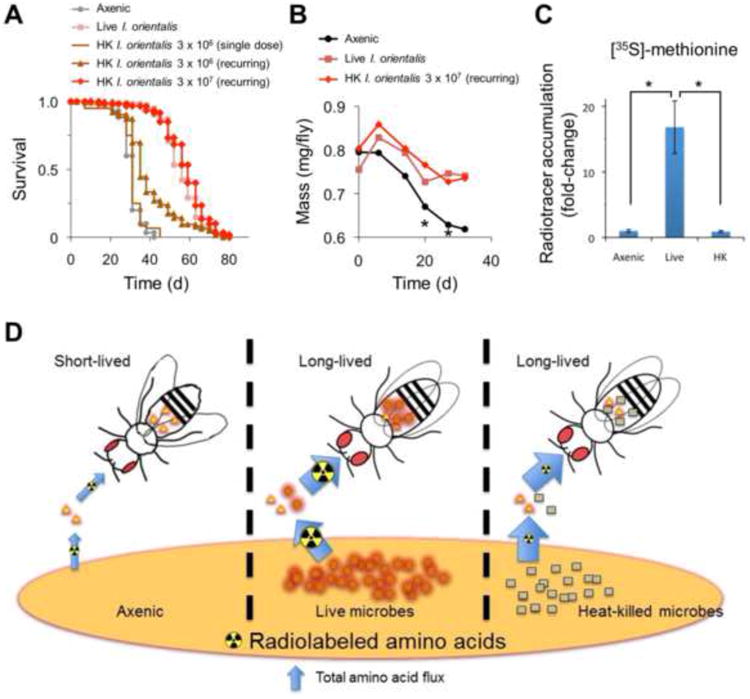

Heat-killed microbes can extend lifespan to the same extent as live microbes

We next asked whether active I. orientalis is needed to rescue fly lifespan during undernutrition. We supplemented fly food with heat-killed I. orientalis either once in early adulthood or at every food change throughout life. A single, relatively low dose of heat-killed I. orientalis did not affect longevity compared to the axenic control, while a recurring supply of heat-killed I. orientalis rescued lifespan partially (Figure 4A). Increasing the quantity of heat-killed I. orientalis given to flies throughout life revealed a dose-dependent rescue of lifespan that matched the longevity observed following live I. orientalis inoculation (Figure 4A). Changes in fly body mass, a measure of metabolic status, were also consistent with the quantity of heat-killed I. orientalis provided (Figure 4B). Interestingly, the dose of heat-killed I. orientalis that resulted in maximum lifespan extension (3 × 107 CFU twice/week = 8.6 × 106 CFU/day) is nearly equivalent to the number of live microbes found associated with flies (Figures S1C and S2C). The estimated protein content contributed by this microbial biomass (4 μg/fly/day for 20 flies) is in strong agreement with fly nutritional requirements quantitatively determined in our previous studies of optimal macronutrient ingestion (Bruce et al., 2013). Although environmental I. orientalis counts may not reflect the number of microbes ingested by flies, quantification of live I. orientalis from our nutrient flux studies (Figure S2B) allowed us to calculate radiotracer accumulation per yeast cell and determine that, over 24 h, flies attained the equivalent of 6.6 ± 0.40 or 3 ± 0.12 (×106) CFU per fly from the [35S]-methionine or [14C]-leucine experiments (Figure 2B), respectively. Hence, direct measurements of I. orientalis accumulation are consistent with the number of microbes available in the fly environment (Figures S1C and S2C).

Figure 4. Heat-killedI. orientalisextends lifespan on an undernutrition diet.

(A) Survival of axenic or I. orientalis-associated flies on 0.1% YE undernutrition diet. Live microbes were supplied once in early adulthood. The indicated quantity of heat-killed (HK) microbes was provided once in early adulthood (single dose) or at every food change (twice/week) throughout life (recurring). Microbial association (live or HK) extends survival in all experiments compared to the axenic control (p < 5 × 10−9 for all comparisons, log-rank test) except in the single dose trial (p = 0.134, log-rank test). N = 57–64 flies for each condition. (B) Body mass increases with microbe supplementation (average of 3 vials). Body mass of axenic flies was significantly lower than that of microbe-associated flies on days 20 and 27 (Kruskal-Wallis followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post-test for multiple comparisons: *, p < 0.05). (C) Accumulation of [35S]-methionine (average ± s.d.) in the presence of live or HK I. orientalis on 0.1% YE medium. While live and HK microbes both extend fly lifespan, only live I. orientalis increases accumulation of the diet-supplemented radiolabel (Kruskal-Wallis followed by Tukey's post-test for multiple comparisons: *, p < 0.05). N = 4 vials of 10 flies for each condition. (D) Model of microbe-mediated amino acid harvest. I. orientalis increases amino acid/protein flux, resulting in improved nutrition and longevity in the fly host. The size of the arrows and radiation symbols represent the amount of amino acid flux and radiolabeled amino acid levels, respectively. See also Figure S4.

Supplementation of tryptone, representing a pure protein source, showed the same effect on fly lifespan as YE or I. orientalis (p > 0.39, log-rank test, Figure S4A). These results rule out the possibility that I. orientalis rescues undernutrition by providing other macro- or micro-nutrients such as vitamins and sterols. Collectively, our results suggest that flies are able to maintain a live population of I. orientalis in order to harvest sufficient amino acids from the diet.

Although both live and heat-killed I. orientalis rescue undernourished fly lifespan (Figure 4A), we would expect live I. orientalis to increase nutrient flux from the diet to the fly (since these nutrients are required for microbe proliferation) but heat-killed I. orientalis should have a negligible effect. Using radiolabeled medium, we show that, while an active microbial metabolism is necessary for increasing amino acid flux from the diet, heat-killed I. orientalis fails to increase fly accumulation of [35S]-methionine (Figure 4C). Taken together, our results support a model where specific microbes directly facilitate amino acid uptake from the diet and act as a source of nutrition to rescue nutritional imbalance in the fly, rather than enhance host metabolism, stimulate indirect processes such as gut transit time, or modify feeding behavior (Figure 4D). This is consistent with previous studies suggesting that insects can use microbes as a food source (Drew et al., 1983; Murphy et al., 1994; Robacker, 2007), although to our knowledge, the scavenging and concentration of protein by a symbiont from a nutrient-poor diet has not previously been quantified.

Discussion

There is currently a growing interest in understanding the mechanisms by which microbes may influence protein-specific malnutrition. Recent studies have shown that protein-specific severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is associated with microbial dysbiosis (Smith et al,. 2013). Existing interventions do not consider differences in microbial metabolism and have limited efficacy, highlighting the need to better understand the metabolic interaction between host and microbes. Here, we reveal that microbe-mediated amino acid harvest from nutrient-poor diets is a fundamental mechanism that synergizes microbial and host metabolism. Our model suggests an alternative interpretation of previous studies of growth and development on low yeast diets that propose the fly microbiota acts genetically up-stream of the nutrient-sensing Tor and insulin signaling pathways, possibly by contributing to protein processing and regulating branched-chain amino acid levels in the hemolymph (Shin et al., 2011; Storelli et al., 2011). Since increased amino acid supply would up-regulate the same nutrient-sensitive pathways, microbe-mediated protein uptake rather than metabolic stimulation may be the primary contributor of enhanced protein metabolism and nutritional rescue. To differentiate between nutrient uptake and processing, future studies of Drosophila-microbe interactions should use quantitative assays to assess microbial number and density, which may contribute greatly to fly nutrition. It is not sufficient to rule out additional mechanisms by ignoring small changes in microbe number, which can contribute greatly to nutrient availability, or measuring microbial growth rate outside the context of the fly environment (Shin et al., 2011; Storelli et al., 2011).

Since amino acid harvest is a key mechanism underlying microbial benefits during undernutrition, we postulate that I. orientalis-fly association may be an adaptive mechanism to survive on a fruit-based low-protein diet in the natural environment (Figure S4B). Indeed, I. orientalis is commonly isolated from field-caught D. melanogaster (Chandler et al., 2012), suggesting that it is a natural fly symbiont. Although Drosophila-yeast associations are common (Anagnostou et al., 2010; Starmer and Fogleman, 1986), we note that I. orientalis benefits flies while S. cerevisiae, another yeast commonly associated with Drosophila, does not fully rescue the detrimental effects of undernutrition. Overall, both yeast and bacteria broadly extend fly lifespan during undernutrition (Figures S1A and S1B). Whether differences in the magnitude of lifespan extension are dependent on microbial growth rate, efficiency of amino acid accumulation, or other mechanisms will require further study.

In response to environmental factors such as diet or antibiotic treatment, most mammalian studies focus on how the microbiota composition changes, despite the clear indication that microbe number is also drastically altered (David et al., 2014; Dethlefsen and Relman, 2011). A recent study revealed that host adiposity and immune function are similarly modulated by an unexpectedly high number of bacterial strains (Faith et al., 2014), suggesting common features of microbial metabolism, rather than strain-specific effects, have the greatest impact on host physiology. This is consistent with our work showing that, in certain contexts, microbial quantity might override quality. While I. orientalis has the greatest beneficial effect on fly lifespan during undernutrition, any microbial growth likely increases protein flux, and maximal benefits may be achieved if quantities are increased. This notion is consistent with a recent study of Drosophila microbiota demonstrating that many bacterial species can promote larval development and decrease adult triglyceride levels. However, this study did not consider the importance of microbial quantity in the context of different nutritional environments (Chaston et al., 2014). Future studies that aim to identify effector strains in any animal system should consider both nutrient flux and microbial quantity as potentially critical parameters.

Recent studies of human kwashiorkor—severe protein-specific malnutrition—have demonstrated the importance of altered gut microbiota in dietary protein deficiency (Smith et al., 2013; Subramanian et al., 2014), suggesting that microbe-mediated amino acid harvest may be an effective intervention to treat protein-specific undernutrition. Digestion of excessive microbial biomass—either associated with food or in the gut itself—may be a major contributor to mammalian nutrition (Kuhad et al., 1997). Interestingly, I. orientalis, also known as Pichia kudriavzevii or Candida krusei (Chan et al., 2012), is commonly associated with several food products, such as wine-grapes (Chavan et al., 2009), cheese (Prillinger et al., 1999), lafun (fermented cassava) (Padonou et al., 2009) and fermented cocoa beans used for chocolate production (Daniel et al., 2009). Food-associated microbes, both bacteria and fungi, are known to colonize the human gut (David et al., 2014), but whether they are able to harvest protein from nutrient-poor diets, similar to I. orientalis, remains to be tested. New methodologies may be needed to quantify microbes in mammalian hosts, complementing the typical characterization of microbiota composition.

Mammalian studies have often focused on the contribution of secondary metabolites to host metabolism, thereby ignoring the huge impact that microbes (and microbial quantity) can obviously play on primary metabolism. Our study begins to characterize the specific dynamics of microbial protein metabolism as a major contributor to host nutrition and health. While clear differences may limit the efficacy of the Drosophila platform for direct studies of human health, our findings highlight the utility of the model for otherwise challenging quantitative studies that complement analogous research in mammals. Further use of this model may advance our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms underlying microbial energy harvest and lead to the development of long-term strategies that treat and prevent malnutrition.

Experimental Procedures

Fly strains

Fly stocks were maintained at 23 °C under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle on a standard medium [1.5% dry active yeast, 5% sucrose, 5% cornmeal, and 1.5% agar (all w/v), supplemented with 0.4% propionic acid and 0.035% phosphoric acid (both v/v)]. The Dahomey line was negative for Wolbachia, as confirmed by PCR of the wsp gene using primers 81F and 691R (Braig et al., 1998).

Identification of microbial species

We established D. melanogaster isofemale lines from field-caught flies collected using banana traps in Jupiter, Florida in 2009. Adult flies from the isofemale lines were washed with 70% ethanol and sterile 1× PBS. Sterilized flies were homogenized by motorized pestle for 10 s in sterile 1× PBS. Fly homogenates were plated on MRS agar and single colonies were isolated for colony PCR. The bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the degenerate primers, 16SA1 (5′-AGAGT TTGAT CMTGG CTCAG) and 16SB1 (5′-TACGG YTACC TTGTT ACGAC TT)(Fukatsu and Nikoh, 1998). The fungal 18S rRNA gene was amplified with NS1 (5′-GTAGT CATAT GCTTG TCTC) and NS2 (5′-GGCTG CTGGC ACCAG ACTTG C) or ITS1 (5′-TCCGT AGGTG AACCT GCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTC CGCTT ATTGA TATGC)(White et al., 1990). After cloning and sequencing the PCR products, homologous sequences were identified by BLAST.

Food preparation

Bacto™ agar, yeast extract (YE), and tryptone (#211705) were from BD Diagnostic Systems (Franklin Lakes, NJ); dry active yeast and cornmeal from LabScientific (Livingston, NJ); and Drosophila enclosures (8 oz. round bottom bottles or 25 × 95 mm vials, polypropylene) and plugs (Droso-Plugs™) from Genesee Scientific (San Diego, CA). All other reagents were from VWR International (Radnor, PA) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).

For lifespan studies, 0.1% or 0.5% YE was used in a base medium of 5% sucrose, 8.6% cornmeal, 0.5% agar, 0.4% propionic acid, and 0.035% phosphoric acid. Diets for the survival curves in Figure S4A did not include cornmeal. Methylparaben (p-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester, also called Nipagen M or Tegosept) supplementation consisted of 0.3% (w/v) of the additive in the absence of propionic and phosphoric acids. All foods were autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min and acids or methylparaben were added after cooling to <65 °C. Food was dispensed into pre-autoclaved vials (2 mL/vial). Calculated dietary protein provided by microbes was based on the expected protein composition of yeast [Live yeast non-water weight = 31% (Alcazar et al., 2000), dry yeast protein content = 38% (NutritionData.com), mass = 80 pg/cell (Haddad and Lindegren, 1953): 80 pg/cell × 31% × 38% = 9.42 pg protein/cell)].

Generation of axenic and microbe-associated flies

Axenic (germ-free) flies were generated by bleach treatment of embryos, as described previously (Bakula, 1969; Brummel et al., 2004). Collections of embryos (<12 h old) were dechorionated for 20 min in 3% sodium hypochlorite (50% v/v regular bleach), rinsed in 70% ethanol for 5 min, and then washed three times with 1× PBS + 0.01% Triton X-100. Sterile embryos were transferred into autoclaved food bottles (500 embryos/bottle) in a laminar flow cabinet. Axenic conditions were confirmed by 1) 16S rRNA gene PCR of DNA extracted from whole fly homogenate or 2) plating the homogenate on MRS agar periodically throughout life, which we found to be more sensitive than PCR for detecting microbial contamination. In a typical PCR, DNA was extracted from 3 flies and 1/17 fly equivalent was used per sample. Plating of swabs from spent vials or homogenates from monoxenic flies showed a single colony morphology in all studies shown, consistent with a lack of microbial contamination between studies. First-generation axenic flies were used for all experiments in this study.

To generate monoxenic flies that were associated with microbes as adults, germ-free flies (typically 3–5 days old) were transferred to axenic food vials containing microbial cultures (50 μL; OD600 = 1.0, corresponding to ∼5 × 105 CFUI. orientalis). This generally marked “day 0” for all studies. I. orientalis was cultured overnight in MRS broth at room temperature without shaking. Heat-killed microbes were prepared by autoclaving at 121 °C for 30 min and storing aliquots at −20 °C.

Lifespan assay

Flies were developed on autoclaved standard medium. Axenic or monoxenic adult males (3–5 days old) were collected under mild CO2 anesthesia and randomly transferred to experimental diets (20–25 flies/vial). Flies were maintained at 25 °C under controlled light (12/12-h light/dark cycle) and humidity (60%). Transfers to fresh food typically occurred every 3–4 days; dead flies were scored at least as often. All fly manipulations were conducted by aseptic technique. Axenic conditions were verified periodically by 16S rRNA gene PCR and/or plating swabs from the interior of spent fly enclosures on rich media and confirming the lack of microbial colonies. Statistically significant differences between survival curves and median lifespan were determined by log-rank test and Fisher's exact test, respectively (Yang et al., 2011).

Microbial load measurements

To measure microbial load in the fly environment, spent food vials were rinsed with 1 mL 1× PBS. Microbe counts were determined by serial dilution plating on MRS agar. To measure microbial load in the fly body, flies were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol for 1 min and then washed three times with sterile 1× PBS. Single whole flies were homogenized in 100 μL 1× PBS by motorized pestle for 10 s. Microbe counts were determined by serial dilution plating on MRS agar.

Nutrient flux measurements

Axenic 2–3 d old Dahomey males (10/vial) were maintained on nutritious food (lifespan diet described above, but with 5% YE) for 3 d and habituated on undernutrition food (unlabeled 0.1% YE lifespan diet) for 1 d before being transferred to the radiolabeled, experimental diet. Radiolabeled food (0.1% YE) was supplemented with one of the tracers (∼0.5 μCi [35S]-methionine, [14C]-leucine, or [14C]-sucrose or ∼1 μCi [α-32P]-dCTP per mL food). Microbes (5 × 105 CFU I. orientalis/vial) were inoculated onto radiolabeled food and incubated for 4 days at 25 °C before the assay was initiated by adding axenic flies. Control medium was not inoculated with microbes. After 24 h of feeding, flies were collected and frozen. Flies on food labeled with [α-32P]-dCTP were directly assayed by liquid scintillation (5 mL ScintiVerse™ BD Cocktail, Fisher Scientific) in a multipurpose scintillation counter (LS 6500, Beckman Coulter). All other flies were homogenized in 100 μL of 1% SDS before transferring to vials for liquid scintillation (Carvalho et al., 2006; Deshpande et al., 2014; Ja et al., 2009). The contribution of microbes to fly nutrient accumulation was determined by comparing the amount of radioactive tracer in flies feeding on microbe-associated food with that in flies which were fed axenic medium. Data were tested for being normally distributed and the appropriate test, Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney rank-sum test, was then used.

Microbial accumulation of radioisotopes was determined by rinsing spent vials with 1 mL of ddH2O and measuring a 100 μL aliquot by liquid scintillation. Fold-change was calculated over the average of axenic controls. Labeled microbes were also counted by serial dilution plating on MRS agar. Radiotracer accumulation per CFU was calculated and, in combination with fly radiotracer measurements, the equivalent CFU of I. orientalis accumulated in flies could be determined.

To measure the tissue distribution of radioisotope, dissected guts and remaining fly carcass were assayed separately by liquid scintillation. Gut tissues damaged during dissection were excluded from analysis. Dissection techniques were validated in parallel experiments using a nonabsorbable dye (FD&C Blue #1) and ensuring no leaching of dye from dissected guts.

Food intake measurement

Feeding assays were performed essentially as described using a radioactive tracer as a food label (Carvalho et al., 2006; Deshpande et al., 2014; Ja et al., 2009). Briefly, adult males (20 flies/vial) were maintained on 0.1%YE food with or without I. orientalis for 1 day and then transferred to the 0.1% YE diet supplemented with ∼1 μCi [α-32P]-dCTP per mL food. After 24 h of feeding, flies were frozen and assayed in 5 mL of scintillation fluid (ScintiVerseTM BD Cocktail, Fisher Scientific) in an LS 6500 Multi-Purpose Scintillation Counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Scintillation counts of aliquots of non-solidified food with radioactive tracer were used to calculate total food intake. Liquid food intake was measured using the CAFE assay, performed as described previously (Deshpande et al., 2014; Ja et al., 2007) using 0.1% YE + 5% sucrose without cornmeal, which is not soluble and therefore excluded in CAFE trials. Capillaries were replaced every 12 h.

Metabolic assays

Flies collected under CO2 anesthesia were massed in pre-weighed tubes using a Voyager Pro balance (VP64CN, OHAUS Corp., Parsippany, NJ), frozen immediately on dry ice, and then homogenized in batches of 6 males in 750 μL of 0.05% Tween-20 using a motorized pestle for 10 s. Homogenates were heat-inactivated at 95 °C for 5 min and clarified by centrifugation (1800 × g for 2 min) at room temperature. Supernatants were then used in the various assays. Free glycerol and total triglyceride (TAG) content were determined using 25 μL of homogenate (1/5 fly equivalent) with 80 μL of Free Glycerol Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by addition of 20 μL of Triglyceride Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Concentrations were quantified based on the absorbance at 535 nm using glycerol as a standard. TAG content was obtained by subtraction of the glycerol concentration from the total TAG concentration. Protein was assessed from 20 μL of homogenate (1/6.25 fly equivalent) mixed with 150 μL of 660 nm Protein Assay reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford IL). Concentrations were quantified based on absorbance at 620 nm and comparison to a BSA standard curve. Glucose and glycogen content were determined according to manufacturer's instructions using either 2.5 or 5 μL of homogenate (1/50 or 1/25 fly equivalent, respectively) and 50 μL of Reaction Mix (Glycogen Assay Kit, BioVision, San Francisco, CA). Trehalose content was determined by adding trehalase (0.002 U per 50 μL reaction, Sigma-Aldrich) instead of the kit's glucoamylase and incubating at 37 °C overnight. Concentrations were quantified based on absorbance at 560 nm using a glycogen standard. All spectrophotometry used a 2104 EnVision plate reader. Measurements were normalized to a single fly equivalent and then to body mass.

ATP content was determined with the ATP Determination Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Three adult flies were collected under CO2 anesthesia and immediately homogenized in 150 μL of ATP assay buffer (6 M guanidine-HCl, 100 mM Tris, 4 mM EDTA, pH 7.8) using a motorized pestle for 10 s. The homogenate was clarified by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 3 min) at room temperature and then the supernatant was diluted with ddH2O. Aliquots (10 μL) of a 1:1000 diluted homogenate (1/5000 fly equivalent) were combined with 100 μL of reaction mix. ATP concentration was quantified based on luminescence using an ATP standard and a 2104 EnVision plate reader. ATP content was normalized to the number of flies.

For each measurement, differences were determined by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons (Prism v5.04).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Microbes extend fly lifespan on undernutrition diet; Related to Figure 1. (A) Survival of axenic or monoxenic flies on 0.1% YE diet. All microbe-associated survival curves differ from that of the axenic control (p < 4.4 ×10-5 for all comparisons, log-rank test). Monoxenic flies were inoculated once as adults with the indicated microbes. N = 59–61 flies for each condition. (B) Independent trial of Figure S1A. Lifespan of I. orientalis-, A. indonesiensis- and S. cerevisiae-associated flies differ from that of the axenic control (p < 1.0 ×10-10 for I. orientalis and A. indonesiensis; p = 0.0046 for S. cerevisiae, log-rank test). Survival of L. plantarum-associated flies does not differ from that of axenic control (p = 0.099, log-rank test). N = 59–61 flies for each condition. (C) Methylparaben eliminates the presence of I. orientalis. Flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet with or without methylparaben. Microbe counts (average + s.d.) were from spent fly enclosures (N = 3), including the food surface, collected on day 8. Spent vials from axenic flies had no microbes regardless of methylparaben supplementation. N.D., not detected. (D) Eliminating environmental microbes with methylparaben treatment abolishes the beneficial effect of microbes on lifespan on 0.1% YE diet. Survival curve of I. orientalis-associated flies does not differ from that of axenic animals (p = 0.32, log-rank test). N = 59–62 flies for each condition. (E) Methylparaben treatment has no effect on lifespan on 0.5% YE diet. Survival curve of I. orientalis-associated flies does not differ from that of axenic animals (p = 0.57, log-rank test). N = 57–60 flies for each condition. (F) Microbial load in flies. I. orientalis-associated flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet. Flies were collected on days 7 and 22 and average microbe counts from whole fly homogenates are plotted (+ s.d.). N = 6 individual flies for each age group. (G) I. orientalis is harbored in the fly gut. I. orientalis-associated flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet for 11 days. Microbe counts from whole flies or the dissected gut are shown (average + s.d.). N = 6 individual flies for each sample source. (H) Microbial load in fly enclosure. I. orientalis-associated flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet. Microbes were collected on days 8 and 26 and average microbe counts from the fly enclosure, including the food surface, are plotted (+ s.d.). N = 3 vials for each time point. (I) Fly-free microbial growth on 0.1% YE diet. I. orientalis (1 × 105 CFU/vial) was inoculated on 0.1% YE medium and incubated at 25 °C. Microbes were collected on the indicated day post-inoculation or immediately after inoculation (day 0) and average microbe counts from vials are shown (+ s.d.). N = 4 vials for each time point. (J) Daily food change eliminates the presence of I. orientalis. Axenic Dahomey males (3-5 d old) were associated with I. orientalis (5 × 105 CFU/vial) on 0.1%YE food. Flies were transferred to fresh axenic medium daily and I. orientalis counts from whole fly homogenates were determined on day 4. Flies that were not transferred to fresh medium over the same period retain I. orientalis-association. N.D., not detected. Average + s.d. is shown for N = 6 flies for each condition.

Figure S2. Microbes incorporate radiolabeled amino acids; Related to Figure 2. (A) Radioisotope-labeled feeding assay for examining nutrient accumulation in microbes. (B) Microbe accumulation of radiolabeled nutrients on 0.1% or 0.5% YE medium. Results (average ± s.d.) are normalized to the axenic control (dashed line) for each radioactive tracer. Significant differences between each tracer and its axenic control are shown (Mann-Whitney rank-sum test or Student's t-test: *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). N = 4 vials for each condition. Met = [35S]-methionine; Leu = [14C]-leucine; dCTP = [α -32P]-dCTP; Suc = [14C]-sucrose. (C, D) I. orientalis association does not affect fly total food intake. (C) Radioisotope-labeled feeding assay on solid 0.1% YE medium. Axenic flies (7-d old) were maintained on 0.1% YE diet for 1 day with or without I. orientalis and then fed a radiolabeled diet for 24 h. Feeding was measured by quantifying the [32P]-dCTP tracer and average ± s.d. is shown. N = 6 vials of 20 flies for each condition. (D) Capillary feeder (CAFE) assay measures liquid food intake. Axenic flies (7 days old) were maintained on 0.1% YE diet for 1 day with or without I. orientalis before starting the CAFE assay on liquid medium (0.1% YE diet without cornmeal). Average (± s.d.) total consumption over 24 h is shown of N = 6 CAFE chambers of 4 flies each.

Figure S3. Physiological and metabolic parameters of axenic orI. orientalis-associated flies maintained on 0.1% or 0.5% YE diets; Related to Figure 3. Flies maintained on 0 1% or 0.5% YE were collected on day 14. Average ± s.d. are shown for N = 6 groups of Dahomey males except for body mass and ATP levels (N = 3). All measurements except for ATP were normalized to fly mass. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using diet and microbe treatment as factors, followed by Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001).

Figure S4. Microbes rescue fly lifespan on undernutrition diet by mimicking yeast extract (YE) and tryptone; Related to Figure 4. (A) Lifelong supplementation of tryptone, YE, or I. orientalis extends lifespan similarly on 0.1% YE food (p > 0.39, log-rank tests of all pairwise comparisons between tryptone, YE, or I. orientalis survival). Tryptone or YE (15 mg/vial, equivalent to 0.75% final w/v) or I. orientalis (3 × 108 CFU/vial) were supplied on fresh food every 3–4 days. All pairwise comparisons of survival curves to the axenic control are significantly different (p < 10-10, log-rank test). N = 58–60 flies for each condition. (B) Schematic describing beneficial effect of microbes on fly lifespan during undernutrition. Lines represent axenic (black) and I. orientalis-associated (red dashed) fly lifespan. The presence of microbes in the low yeast environment (low protein) rescues undernutrition and extends fly lifespan. On an optimal diet with moderate yeast, the effect of microbes on fly lifespan is minimal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R00AG030493 and R21DK092735), The Ellison Medical Foundation, and the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research. We thank M. Piper and L. Partridge (University College London) for the Dahomey fly line and T. Brummel (Long Island University) and A. Soto Obando (The Scripps Research Institute) for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions The authors have made the following declarations about their contributions: conceived and designed experiments: R.Y., S.A.D., K.D.B., and W.W.J. Performed experiments: R.Y, S.A.D., and E.M.M. Performed data analysis: R.Y., S.A.D. and W.W.J. Wrote the paper: R.Y, K.D.B., and W.W.J.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alcazar EB, Rocha-Leao MHM, Dweck J. Yeast intracellular water determination by thermogravimetry. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2000;59:643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou C, Dorsch M, Rohlfs M. Influence of dietary yeasts on Drosophila melanogaster life-history traits. Entomol Exp Et Appl. 2010;136:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, Golic KG, Hawley SR. Parasites, pests, and diseases. In: Ashburner M, Golic KG, Hawley SR, editors. Drosophila: A laboratory handbook. New York: CSHL Press; 2005. pp. 1285–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Bakula M. Persistence of a microbial flora during postembryogenesis of Drosophila melanogaster. J Invertebr Pathol. 1969;14:365–374. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(69)90163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum JE, Fischer CN, Miles J, Handelsman J. Frequent replenishment sustains the beneficial microbiome of Drosophila melanogaster. mBio. 2013;4:e00860–00813. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00860-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braig HR, Zhou W, Dobson SL, O'Neill SL. Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2373–2378. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2373-2378.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick NA, Buchon N, Lemaitre B. Microbiota-induced changes in Drosophila melanogaster host gene expression and gut morphology. mBio. 2014;5:e01117–01114. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01117-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick NA, Lemaitre B. Gut-associated microbes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:307–321. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce KD, Hoxha S, Carvalho GB, Yamada R, Wang HD, Karayan P, He S, Brummel T, Kapahi P, Ja WW. High carbohydrate-low protein consumption maximizes Drosophila lifespan. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:1129–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummel T, Ching A, Seroude L, Simon AF, Benzer S. Drosophila lifespan enhancement by exogenous bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12974–12979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405207101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho GB, Kapahi P, Anderson DJ, Benzer S. Allocrine modulation of feeding behavior by the sex peptide of Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16:692–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan GF, Gan HM, Ling HL, Rashid NA. Genome sequence of Pichia kudriavzevii M12, a potential producer of bioethanol and phytase. Eukaryot Cell. 2012;11:1300–1301. doi: 10.1128/EC.00229-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JA, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Yeast communities of diverse Drosophila species: comparison of two symbiont groups in the same hosts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7327–7336. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01741-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaston JM, Newell PD, Douglas AE. Metagenome-Wide Association of Microbial Determinants of Host Phenotype in Drosophila melanogaster. mBio. 2014;5:e01631–01614. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01631-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan P, Mane S, Kulkarni G, Shaikh S, Ghormade V, Nerkar DP, Shouche Y, Deshpande MV. Natural yeast flora of different varieties of grapes used for wine making in India. Food Microbiol. 2009;26:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho I, Blaser MJ. The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nature Rev Genet. 2012;13:260–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claesson MJ, Cusack S, O'Sullivan O, Greene-Diniz R, de Weerd H, Flannery E, Marchesi JR, Falush D, Dinan T, Fitzgerald G, et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LM, Blaser MJ. Pathways in microbe-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2013;17:883–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel HM, Vrancken G, Takrama JF, Camu N, De Vos P, De Vuyst L. Yeast diversity of Ghanaian cocoa bean heap fermentations. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9:774–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande SA, Carvalho GB, Amador A, Phillips AM, Hoxha S, Lizotte KJ, Ja WW. Quantifying Drosophila food intake: comparative analysis of current methodology. Nature Methods. 2014;11:535–540. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4554–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AE. Lessons from studying insect symbioses. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew RAI, Courtice AC, Teakle DS. Bacteria as a natural source of food for adult fruit-flies (Diptera, Tephritidae) Oecologia. 1983;60:279–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00376839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkosar B, Storelli G, Defaye A, Leulier F. Host-intestinal microbiota mutualism: “Learning on the Fly”. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith JJ, Ahern PP, Ridaura VK, Cheng J, Gordon JI. Identifying gut microbe-host phenotype relationships using combinatorial communities in gnotobiotic mice. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:220ra211. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint HJ, Scott KP, Louis P, Duncan SH. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nature Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:577–589. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukatsu T, Nikoh N. Two intracellular symbiotic bacteria from the mulberry psyllid Anomoneura mori (Insecta, Homoptera) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3599–3606. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3599-3606.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad SA, Lindegren CC. A method for determining the weight of an individual yeast cell. Appl Microbiol. 1953;1:153–156. doi: 10.1128/am.1.3.153-156.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ja WW, Carvalho GB, Mak EM, de la Rosa NN, Fang AY, Liong JC, Brummel T, Benzer S. Prandiology of Drosophila and the CAFE assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8253–8256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702726104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ja WW, Carvalho GB, Zid BM, Mak EM, Brummel T, Benzer S. Water-and nutrient-dependent effects of dietary restriction on Drosophila lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18633–18637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908016106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, Trinidad C, Bogardus C, Gordon JI, Krakoff J. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:58–65. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katewa SD, Demontis F, Kolipinski M, Hubbard A, Gill MS, Perrimon N, Melov S, Kapahi P. Intramyocellular fatty-acid metabolism plays a critical role in mediating responses to dietary restriction in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 2012;16:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajmalnik-Brown R, Ilhan ZE, Kang DW, DiBaise JK. Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2012;27:201–214. doi: 10.1177/0884533611436116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhad RC, Singh A, Tripathi KK, Saxena RK, Eriksson KE. Microorganisms as an alternative source of protein. Nutr Rev. 1997;55:65–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley RE, Hamady M, Lozupone C, Turnbaugh PJ, Ramey RR, Bircher JS, Schlegel ML, Tucker TA, Schrenzel MD, Knight R, et al. Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science. 2008;320:1647–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.1155725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KM, Teakle DS, Macrae IC. Kinetics of colonization of adult Queensland fruit flies (Bactrocera tryoni) by dinitrogen-fixing alimentary tract bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2508–2517. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2508-2517.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell PD, Douglas AE. Interspecies interactions determine the impact of the gut microbiota on nutrient allocation in Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:788–796. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02742-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padonou SW, Nielsen DS, Hounhouigan JD, Thorsen L, Nago MC, Jakobsen M. The microbiota of Lafun, an African traditional cassava food product. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;133:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prillinger H, Molnar O, Eliskases-Lechner F, Lopandic K. Phenotypic and genotypic identification of yeasts from cheese. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1999;75:267–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1001889917533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robacker DC. Chemical ecology of bacterial relationships with fruit flies. Integ Protect Olive Crops. 2007;30:9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shin SC, Kim SH, You H, Kim B, Kim AC, Lee KA, Yoon JH, Ryu JH, Lee WJ. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. 2011;334:670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1212782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MI, Yatsunenko T, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Mkakosya R, Cheng J, Kau AL, Rich SS, Concannon P, Mychaleckyj JC, et al. Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science. 2013;339:548–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1229000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starmer WT, Fogleman JC. Coadaptation of Drosophila and yeasts in their natural habitat. J Chem Ecol. 1986;12:1037–1055. doi: 10.1007/BF01638995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storelli G, Defaye A, Erkosar B, Hols P, Royet J, Leulier F. Lactobacillus plantarum promotes Drosophila systemic growth by modulating hormonal signals through TOR-dependent nutrient sensing. Cell Metab. 2011;14:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S, Huq S, Yatsunenko T, Haque R, Mahfuz M, Alam MA, Benezra A, DeStefano J, Meier MF, Muegge BD, et al. Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished Bangladeshi children. Nature. 2014;509:417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature13421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature. 2006;444:1027–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature05414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M, Gelfand D, Shinsky J, White TJ, editors. PCR Protocols. Academic Press; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann A, Allahyar A, Greiner TU, Plovier H, Lunden GO, Larsson T, Drucker DJ, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Backhed F. Microbial modulation of energy availability in the colon regulates intestinal transit. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CN, Ng P, Douglas AE. Low-diversity bacterial community in the gut of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1889–1900. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JS, Nam HJ, Seo M, Han SK, Choi Y, Nam HG, Lee SJ, Kim S. OASIS: online application for the survival analysis of lifespan assays performed in aging research. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zid BM, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Vargas MA, Kolipinski MC, Lu TA, Benzer S, Kapahi P. 4E-BP extends lifespan upon dietary restriction by enhancing mitochondrial activity in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;139:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Microbes extend fly lifespan on undernutrition diet; Related to Figure 1. (A) Survival of axenic or monoxenic flies on 0.1% YE diet. All microbe-associated survival curves differ from that of the axenic control (p < 4.4 ×10-5 for all comparisons, log-rank test). Monoxenic flies were inoculated once as adults with the indicated microbes. N = 59–61 flies for each condition. (B) Independent trial of Figure S1A. Lifespan of I. orientalis-, A. indonesiensis- and S. cerevisiae-associated flies differ from that of the axenic control (p < 1.0 ×10-10 for I. orientalis and A. indonesiensis; p = 0.0046 for S. cerevisiae, log-rank test). Survival of L. plantarum-associated flies does not differ from that of axenic control (p = 0.099, log-rank test). N = 59–61 flies for each condition. (C) Methylparaben eliminates the presence of I. orientalis. Flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet with or without methylparaben. Microbe counts (average + s.d.) were from spent fly enclosures (N = 3), including the food surface, collected on day 8. Spent vials from axenic flies had no microbes regardless of methylparaben supplementation. N.D., not detected. (D) Eliminating environmental microbes with methylparaben treatment abolishes the beneficial effect of microbes on lifespan on 0.1% YE diet. Survival curve of I. orientalis-associated flies does not differ from that of axenic animals (p = 0.32, log-rank test). N = 59–62 flies for each condition. (E) Methylparaben treatment has no effect on lifespan on 0.5% YE diet. Survival curve of I. orientalis-associated flies does not differ from that of axenic animals (p = 0.57, log-rank test). N = 57–60 flies for each condition. (F) Microbial load in flies. I. orientalis-associated flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet. Flies were collected on days 7 and 22 and average microbe counts from whole fly homogenates are plotted (+ s.d.). N = 6 individual flies for each age group. (G) I. orientalis is harbored in the fly gut. I. orientalis-associated flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet for 11 days. Microbe counts from whole flies or the dissected gut are shown (average + s.d.). N = 6 individual flies for each sample source. (H) Microbial load in fly enclosure. I. orientalis-associated flies were maintained on 0.1% YE diet. Microbes were collected on days 8 and 26 and average microbe counts from the fly enclosure, including the food surface, are plotted (+ s.d.). N = 3 vials for each time point. (I) Fly-free microbial growth on 0.1% YE diet. I. orientalis (1 × 105 CFU/vial) was inoculated on 0.1% YE medium and incubated at 25 °C. Microbes were collected on the indicated day post-inoculation or immediately after inoculation (day 0) and average microbe counts from vials are shown (+ s.d.). N = 4 vials for each time point. (J) Daily food change eliminates the presence of I. orientalis. Axenic Dahomey males (3-5 d old) were associated with I. orientalis (5 × 105 CFU/vial) on 0.1%YE food. Flies were transferred to fresh axenic medium daily and I. orientalis counts from whole fly homogenates were determined on day 4. Flies that were not transferred to fresh medium over the same period retain I. orientalis-association. N.D., not detected. Average + s.d. is shown for N = 6 flies for each condition.

Figure S2. Microbes incorporate radiolabeled amino acids; Related to Figure 2. (A) Radioisotope-labeled feeding assay for examining nutrient accumulation in microbes. (B) Microbe accumulation of radiolabeled nutrients on 0.1% or 0.5% YE medium. Results (average ± s.d.) are normalized to the axenic control (dashed line) for each radioactive tracer. Significant differences between each tracer and its axenic control are shown (Mann-Whitney rank-sum test or Student's t-test: *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001). N = 4 vials for each condition. Met = [35S]-methionine; Leu = [14C]-leucine; dCTP = [α -32P]-dCTP; Suc = [14C]-sucrose. (C, D) I. orientalis association does not affect fly total food intake. (C) Radioisotope-labeled feeding assay on solid 0.1% YE medium. Axenic flies (7-d old) were maintained on 0.1% YE diet for 1 day with or without I. orientalis and then fed a radiolabeled diet for 24 h. Feeding was measured by quantifying the [32P]-dCTP tracer and average ± s.d. is shown. N = 6 vials of 20 flies for each condition. (D) Capillary feeder (CAFE) assay measures liquid food intake. Axenic flies (7 days old) were maintained on 0.1% YE diet for 1 day with or without I. orientalis before starting the CAFE assay on liquid medium (0.1% YE diet without cornmeal). Average (± s.d.) total consumption over 24 h is shown of N = 6 CAFE chambers of 4 flies each.

Figure S3. Physiological and metabolic parameters of axenic orI. orientalis-associated flies maintained on 0.1% or 0.5% YE diets; Related to Figure 3. Flies maintained on 0 1% or 0.5% YE were collected on day 14. Average ± s.d. are shown for N = 6 groups of Dahomey males except for body mass and ATP levels (N = 3). All measurements except for ATP were normalized to fly mass. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA using diet and microbe treatment as factors, followed by Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001).

Figure S4. Microbes rescue fly lifespan on undernutrition diet by mimicking yeast extract (YE) and tryptone; Related to Figure 4. (A) Lifelong supplementation of tryptone, YE, or I. orientalis extends lifespan similarly on 0.1% YE food (p > 0.39, log-rank tests of all pairwise comparisons between tryptone, YE, or I. orientalis survival). Tryptone or YE (15 mg/vial, equivalent to 0.75% final w/v) or I. orientalis (3 × 108 CFU/vial) were supplied on fresh food every 3–4 days. All pairwise comparisons of survival curves to the axenic control are significantly different (p < 10-10, log-rank test). N = 58–60 flies for each condition. (B) Schematic describing beneficial effect of microbes on fly lifespan during undernutrition. Lines represent axenic (black) and I. orientalis-associated (red dashed) fly lifespan. The presence of microbes in the low yeast environment (low protein) rescues undernutrition and extends fly lifespan. On an optimal diet with moderate yeast, the effect of microbes on fly lifespan is minimal.