Abstract

One of best validated findings in schizophrenia research is the association between blockade of dopamine D2 receptors and the effects of antipsychotics on positive psychotic symptoms. The aim of the present study was to examine correlations between baseline striatal D2/3 receptor binding potential (BPp) values and treatment outcome in a cohort of antipsychotic-naïve first-episode schizophrenia patients. Additionally, we wished to investigate associations between striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor blockade and alterations of negative symptoms as well as functioning and subjective well-being. Twenty-eight antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia patients and 26 controls were included in the study. Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with [123I]iodobenzamide ([123I]-IBZM) was used to examine striatal D2/3 receptor BPp. Patients were examined before and after 6 weeks of treatment with the D2/3 receptor antagonist amisulpride. There was a significant negative correlation between striatal D2/3 receptor BPp at baseline and improvement of positive symptoms in the total group of patients. Comparing patients responding to treatment to nonresponders further showed significantly lower baseline BPp in the responders. At follow-up, the patients demonstrated a negative correlation between the blockade and functioning, whereas no associations between blockade and negative symptoms or subjective well-being were observed. The results show an association between striatal BPp of dopamine D2/3 receptors in antipsychotic-naïve first-episode patients with schizophrenia and treatment response. Patients with a low BPp have a better treatment response than patients with a high BPp. The results further suggest that functioning may decline at high levels of dopamine receptor blockade.

Key words: [123I]iodobenzamide, SPECT, occupancy, amisulpride, subjective well-being

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a complex brain disorder with multifactorial disease mechanisms. In spite of great advances in the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms during the last decades, progress in treatment strategies has been hindered by eg, the complexity of the illness and the absence of biologically valid diagnostic criteria.

Positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) data generally support an increase in striatal dopamine release and synthesis capacity in psychotic schizophrenia patients as well as in patients at ultra-high risk for psychosis.1–12 In recent studies, this is found more pronounced in the associative striatum.8–10,12 Antipsychotic compounds suppress dopamine activity via blockade of striatal D2 receptors, and the correlation between antipsychotic potency of first generation antipsychotics (FGAs) in vitro and blockade of the D2 receptor is well validated.13,14 In line with this, in vivo studies have found that 60%–70% occupancy of striatal D2 receptors is required to achieve an antipsychotic effect of FGAs.15–17

Most studies of unmedicated schizophrenia patients have failed to demonstrate significant differences of striatal D2 receptor BP in patients compared to healthy controls (HC) (for references and review, see Laruelle18 and Howes et al19). The meta-analysis by Laruelle18 did show a modest (around 12%) elevation in baseline striatal D2 receptor BP in patients. In a newer meta-analysis, though, no difference between patients and controls was observed, when analyses included only drug-naïve patients.19 In line with this, 2 studies on unmedicated patients failed to find differences in baseline D2 receptor BP in patients compared to control.9,20 However, patients showed a greater change in D2 BP following pharmacological dopamine depletion than controls, indicating that baseline extracellular dopamine concentrations and D2 receptor occupancy by dopamine are elevated in schizophrenia. The interpretation of PET and SPECT data on D2 receptor BP in schizophrenia patients is complicated by the fact that increases in endogenous dopamine release and synthesis are likely to decrease D2 receptor BP both by direct competition with the ligand and via agonist-induced internalization of the receptors.21–23 Consequently, the literature tends to support increased dopamine stimulation and decreased availability of striatal D2 receptors in psychotic patients.

In daily clinical practice, the response of individual patients to antipsychotic treatment differs considerably,24–28 possibly due to differences in endogenous dopamine activity between patients.29 In a recent study dopamine synthesis capacity was found to be significantly higher in 12 good responders compared to 12 patients with treatment resistant illness.11 This may suggest that patients with greater dopamine elevation may be more likely to respond to dopamine blockade. Earlier data from the same group suggest that responders and nonresponders represent separate subtypes that may benefit from different treatment approaches.30 This is consistent with findings from our group, implying subtypes with either serotonergic or dopaminergic disturbances.31,32 Moreover, growing evidence has shown that glutamatergic disturbances might play a role in schizophrenia, particularly in treatment-resistant patients.33,34

In line with the subdivision of schizophrenia patients based on baseline dopamine activity is the finding that some patients have a poor treatment response despite high striatal D2 receptor occupancy.35,36 Other data suggest that lower baseline dopamine activity is associated with an increased risk of developing dysphoria, akathisia and extrapyramidal side effects (EPS).37 In addition to EPS, dopamine receptor occupancy by antipsychotics has also been associated with (secondary) negative symptoms such as avolition, apathy, and affective flattening38–40 and with subjective experience.41,42 The Subjective Well-Being under Neuroleptics Scale (SWN)43 has been used in studies relating subjective experiences with dopaminergic changes. Two studies44,45 have found a negative association between striatal D2 receptor occupancy and subjective well-being in patients treated with D2 antagonists, and de Haan et al44 suggest that negative subjective experience might be more sensitive to D2 receptor occupancy than EPS. Both studies, however, included previously medicated patients.

In general, the literature emphasizes the need for predictive markers for treatment response as well as for development of side effects, thereby sparing patients unnecessary treatment trials and adverse effects. In the search for such markers, it is critical to examine the patients before their brains have been modified by antipsychotic medication and repeated relapses—and to follow the patients over time to study the effects of specific interventions.

In the present study, SPECT [123I]-IBZM was used to examine the relationship between baseline D2/3 receptor binding potential (BPP) and treatment outcome in a quite large cohort of antipsychotic-naïve first-episode schizophrenia patients. Additionally, we related D2/3 receptor occupancy following 6 weeks of monotherapy with the relatively selective D2/3 antagonist amisulpride to functioning and subjective well-being. High resolution PET studies have found dopamine activity more pronounced in the functionally defined associative striatum.8,9 We used an automatic application of regions dividing the striatum into its anatomic subdivisions; ie, the caudate and the putamen. Since the caudate is part of the associative striatum46 we used this region as our region of interest. With the spatial resolution of our SPECT system (7.4mm) we assumed similar to Stone et al47 that this is sufficient to resolve the caudate from the putamen.

We hypothesized: (1) first-episode schizophrenia patients with low striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor BPp in the antipsychotic-naïve state achieve a better treatment response from striatal D2/3 receptor blockade than patients with a high BPp, particularly regarding positive symptoms; and (2) high striatal dopamine D2/3 receptor occupancy is associated with deterioration of a patient’s functioning and subjective well-being.

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki II and approved by the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (H-D-2008–088). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Thirty-two first-episode patients, aged 18–45 years, meeting the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) criteria for schizophrenia were recruited from the Capital Region of Denmark as part of a large, multimodal longitudinal study on antipsychotic-naïve first-episode schizophrenia patients (the Pan European Collaboration Antipsychotic-Naive Studies [PECANS]). There is a partial overlap between the participants in the present study and participants in previously published articles from the PECANS study on different modalities regarding reward processing48,49 and psychophysiology.50

A structured diagnostic interview (Schedule of Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry [SCAN], version 2.1) was performed to verify the diagnosis. None of the patients included in the study had ever been treated with antipsychotic medications or methylphenidate. Patients in antidepressant treatment were either excluded or taken out of their medication 1 month prior to baseline examinations. Other exclusion criteria were serious head traumas, neurological diseases, developmental disorders, pregnancy, and drug dependency (according to ICD-10). Twenty-eight HC matched by gender, age, and parental socioeconomic status were recruited through advertisement. The exclusion criteria were the same as for the patients, and also included former or current psychiatric illnesses, drug abuse or psychiatric diagnosis among first-degree relatives. Urine samples were used for drug screening (Rapid Response, Jepsen HealthCare) for all participants prior to the SPECT scanning.

Four patients and 2 HC were excluded from all analyses. Two patients were excluded due to technical problems with the SPECT image acquisition and one was diagnosed with severe major depressive disorder with psychotic features (DF 32.3) just after baseline examinations. Since conflicting results exist for the association between D2/3 receptor availability and cannabis,51,52 we also excluded one patient due to positive cannabis screenings before the SPECT scans. The excluded HC both received antidepressants at a later 6-month follow-up examination. Four patients discontinued the study and an additional 3 patients were not included at follow-up; see supplementary material. The patients who discontinued the study were not significantly more ill based on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Thus, the complete dataset consisted of 28 patients, 26 HC at baseline and 21 patients at follow-up.

Medication

Treatment with amisulpride was started up in the patients after the baseline examinations. Amisulpride was chosen as the “tool compound” due to its relatively selective D2/3 receptor antagonistic effects.53 The dosage was slowly increased and individually adjusted according to the clinical impression of symptoms and complaints of adverse effects. No medical treatment against adverse effects was allowed. Follow-up examinations were done after 6 weeks of treatment. No adjustment to the dose was allowed in the last week prior to follow-up examinations.

Clinical Measures

In the patient group, psychopathology was assessed with PANSS.54 Subjective experience of well-being and functioning were assessed with the short form of the SWN (SWNS)55 and global assessment of functioning (GAF), respectively. We used both the GAF symptom score (GAF-S) and the GAF functioning score (GAF-F). Adverse effects were rated with the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale56 (supplementary material).

The change in PANSS scores was calculated as a percentage change between scores at follow-up and baseline. Patients responding to treatment were defined as having an improvement of PANSS positive score of more than 30% similar to a previous study by Meisenzahl et al.57

SPECT Acquisition

SPECT data were obtained with a Siemens Symbia T2 series SPECT•CT scanner with low energy high-resolution collimators (full width at half-maximum 7.4mm) and two-slice CT. The ligand, (S)-N-[(1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)methyl]-2-hydroxy-3-iodo-6-methoxybenzamide ([123I]-IBZM) was chosen due to its selectivity for striatal D2/3 receptors.58,59 All participants received 185mBq [123I]-IBZM per scanning (GE Healthcare). The SPECT scanning was performed using the constant infusion technique.60,61 A CT scout and 2×30min tomography were performed. The individually adjusted dose of amisulpride was administered to all patients at same time, 3h prior to the SPECT scanning at follow-up.

Plasma free fraction of [123I]-IBZM was determined using ultrafiltration (Centrifree, 30000 MW).62 The plasma metabolite analysis of [123I]-IBZM was performed using Oasis WCX (Waters) solid phase extraction units and stepwise elution with water, 40% acetonitrile and acidified 95% methanol. The native compound was eluted in the water phase and the metabolites in the subsequent elution.

All participants had a structural MRI scan performed for co-registration. The HC were only scanned at baseline to reduce the radiation dose.

Note that the supplementary material contains the details of the SPECT and MRI acquisitions.

Image Analyses

SPECT images were reconstructed with scatter correction and CT-based attenuation correction using Flash 3D iterative reconstruction (4 subsets, 8 iterations, Gaussian filter 9mm) on a Siemens syngo workstation (software version VA60B). The 2 [123I]-IBZM tomographies were summed and activity measurements were decay-corrected to the time of the radioligand injection. The CT image from the SPECT scanning and the MRI image were co-registered using the statistical parametric mapping (SPM8) method. The result of the SPM co-registration was then carefully inspected in all 3 planes and, if needed, adjusted manually using a local implementation of an image overlay method.63 The information from the co-registration between CT and MRI images was used for co-registration between SPECT and MRI. Inspection and manually adjustments were repeated if needed.

Regions of interest were defined using the high resolution structural MR images and automatically applied to the co-registered SPECT image using a volume-of-interest brain template.64 We focused on the caudate and chose the cerebellum as the reference region.65

Data Analysis and Statistics

BPp was used as a measure of the regional dopamine D2/3 receptor density available for [123I]-IBZM binding. BPp refers to the steady-state ratio of specifically bound radioligand to that of total parent radioligand in plasma.66 The occupancy was calculated as:

IBM SPSS version 20 statistics was used for the statistical analyses. For the between group comparison, an independent t-test was used when appropriate, and Mann-Whitney U test when there was evidence of nonnormal distribution. The repeated measures ANOVA analyses were carried out with an approximate normal distribution and with group and gender used as between-subjects factors when means of the BPp were compared. Paired t-test was used when baseline measurements were compared with follow-up data. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used in the analyses, though the correlations between BPp and change in PANSS scores, GAF and SWNS were analysed using general linear modelling techniques.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Data

The patient group did not differ significantly by gender, age, or handedness from the HC group. The 2 groups did, though, differ on smoking habits; table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data and Psychopathology

| Baseline | N | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female/male | Schz.p | 14/14 | |||

| HC | 13/13 | ||||

| Age (years) | Schz.p | 28 | 23 | 4.4 | 18 to 37 |

| HC | 26 | 23 | 4.7 | 18 to 38 | |

| Hand-score | Schz.p | 28 | 64 | 57 | −88 to 100 |

| HC | 24 | 61 | 62 | −100 to 100 | |

| DUI (weeks) | 69 | 88 | 2 to 312 | ||

| GAF-S | 40 | 9.3 | 25 to 61 | ||

| GAF-F | 42 | 11.9 | 30 to 75 | ||

| SWNS total | 24 | 67 | 13.7 | 41 to 88 | |

| PANSS positive | 20 | 3.6 | 10 to 29 | ||

| PANSS negative | 20 | 7.7 | 7 to 38 | ||

| PANSS general | 41 | 8.4 | 22 to 56 | ||

| PANSS total | 81 | 15.3 | 39 to 102 | ||

| Follow-up | 24 | ||||

| Female/male | 12/12 | ||||

| GAF-S | 23 | 57a | 8.6 | 37 to 80 | |

| GAF-F | 23 | 56a | 12.6 | 32 to 75 | |

| SWNS total | 76a | 12.7 | 44 to 99 | ||

| PANSS positive | 14a | 3.5 | 7 to 20 | ||

| PANSS negative | 20 | 6.1 | 9 to 33 | ||

| PANSS general | 31a | 7.3 | 18 to 48 | ||

| PANSS total | 65a | 13.8 | 40 to 100 | ||

| Dose (mg) | 238 | 120 | 50 to 500 | ||

| (S)-amisulpride (ng/ml) | 392 | 290 | 15 to 1013 | ||

| Diagnosis no. | 28 | ||||

| DF.20.0 paranoid | 19 | ||||

| DF.20.1 disorganised | 3 | ||||

| DF.20.3 undifferentiated | 3 | ||||

| DF.20.9 unspecified | 3 | ||||

| SES (A/B/C) | Schz.p | 28 | 4 | 12 | 8 |

| HC | 25 | 5 | 16 | 4 | |

| Tobacco | Schz.p | 28 | 61% smokers | ||

| HC | 24 | 25% smokers | |||

Note: DUI, duration of untreated illness; GAF-F, global assessment of functioning—functioning score; GAF-S: global assessment of functioning—symptom score; HC, healthy controls; PANSS, positive and negative syndrome scale; Sch.p, schizophrenia patients; SD, standard deviation; SES,Parental socioeconomic status (A:high/B:moderate/C:low); SWNS, Subjective Well-Being under Neuroleptics Scale, short version. DUI was calculated from the time a patient experienced a continuous invasive deterioration of functioning due to psychosis-related symptoms. 75

aSignificant difference from baseline.

SPECT Data, Baseline

There were no significant differences in BPp (total, left or right caudate) between patients and HC at baseline; table 2.

Table 2.

SPECT Data

| Baseline | N | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPp total caudate | Schz.p | 28 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 1.5–5.6 |

| HC | 26 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 1.6–4.3 | |

| BPp left caudate | Schz.p | 2.9 | 1.1 | 1.6–5.8 | |

| HC | 2.9 | 0.7 | 1.6–4.5 | ||

| BPp right caudate | Schz.p | 2.9 | 1.2 | 1.3–5.6 | |

| HC | 2.6 | 0.8 | 1.5–4.3 | ||

| Follow-up | |||||

| BPp total caudate | 22 | 1.3a | 0.7 | 0.3–2.5 | |

| BPp left caudate | 1.3a | 0.7 | 0.4–3.0 | ||

| BPp right caudate | 1.2a | 0.7 | 0.3–2.6 | ||

| Occupancy total caudate (%) | 52 | 19 | 15–84 | ||

| Occupancy left caudate (%) | 50 | 20 | 7–85 | ||

| Occupancy right caudate (%) | 55 | 21 | 17–83 | ||

Note: BPp, binding potential; HC, healthy controls; Schz.p, schizophrenia patients; SD, standard deviation.

aSignificant difference from baseline.

Follow-Up Data

The difference between baseline and follow-up measures of BPp, GAF, SWNS, and PANSS in patients was all significant. BPp decreased. PANSS, GAF, and SWNS scores all improved. The PANSS negative score did not change significantly; table 1.

Correlations Between BPp and Treatment Response

Since clinical follow-up was available for a few patients without follow-up SPECT, 24 patients were included in the analyses.

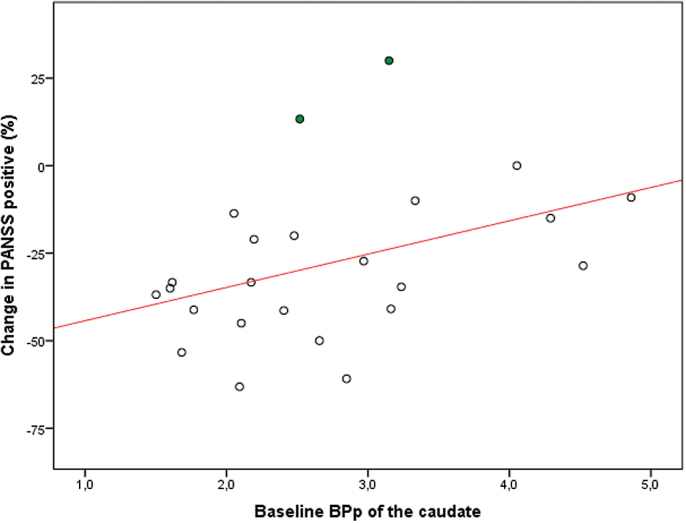

Significant positive correlations were found between baseline BPp of the caudate and the change in PANSS score in the total patient group. Patients with a low BPp had a better treatment response. The correlations were significant for PANSS positive (P = .048, r 2 = .166); PANSS general (P = .011, r 2 = .257); and PANSS total (P = .003, r 2 = .342) but nonsignificant for PANSS negative scores (P = .328); figure 1. The 2 patients with a worsening of positive symptoms (filled circles in figure 1) had very low PANSS positive scores at baseline. One was also treated with a low dose of amisulpride (50mg). Omitting them from the regression strengthened the results (P = .014, r 2 = .268).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between binding potential of the caudate and change in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale positive score in the patient group. N = 24; R 2 = .166; P = .048.

No significant correlations between BPp at baseline and percentage change in either GAF or SWNS were found.

We also compared patients responding to treatment (defined as an improvement of PANSS positive ≥30%) (n = 13, f = 5, m = 8) to patients not responding (n = 11, f = 7, m = 4). Responders had a significantly lower BPp (mean BPp 2.2 vs 3.3 in the caudate, P = .003); a lower GAF-F (mean 37 vs 51, P = .002); and a lower GAF-S score (mean 37 vs 46, P = .028) at baseline. The responders had, per definition, a significantly higher improvement on the PANSS positive, but also on the PANSS general and total score compared to non-responders. Furthermore, responders and nonresponders were found to have similar baseline PANSS scores. The responders improved more on the GAF-S compared to nonresponders; however, they did not improve more on the GAF-F and SWNS. In secondary analyses, we also tested whether the groups or results changed if the rescaled PANSS positive scale (PANSS0–6) was used. Responders were then defined as having an improvement on PANSS0–6 positive ≥50%.68,69 One male patient moved to the nonresponder group; the results were otherwise similar.

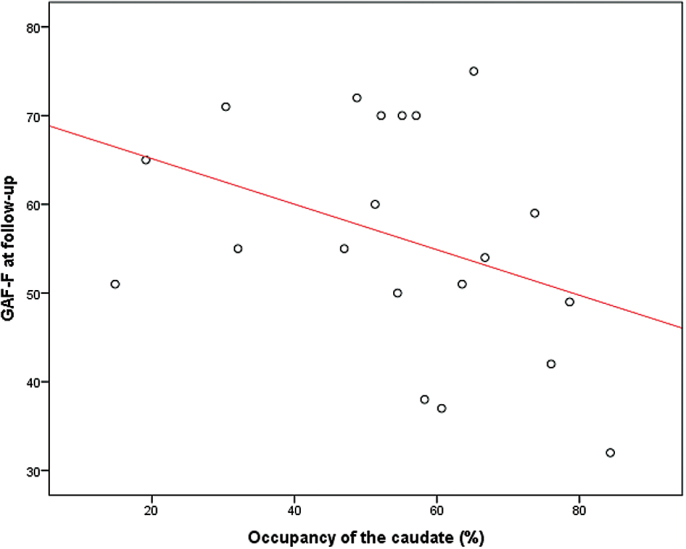

Correlations at Follow-Up

The mean daily dose of amisulpride was 238 (SD 120) mg and was well correlated with the serum level of amisulpride [(S)-amisulpride] (P < .001). We did not find any correlations between caudate BPp at baseline and the optimal dose needed to obtain clinical effect. The dose of amisulpride and (S)-amisulpride were significantly correlated with the occupancy (P = .003 and P < .001); supplementary material. There were no significant correlations between the dose [or (S)-amisulpride] and change in PANSS, change in SWNS or change in GAF. Consistent with these findings we did not find any significant correlations between the occupancy and change in PANSS, SWNS, or GAF. The occupancy was significantly negatively correlated with GAF-F, however, at follow-up (P = .049; Spearman’s rho = −.446). Since we only had a hypothesis regarding GAF and not the specific GAF-F score, this finding is more explorative, but may suggest that the more the dopamine receptors were blocked, the worse the functioning; figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between occupancy and functioning by global assessment of functioning—functioning score. A first-order linear approximation is included in the figure solely to illustrate the sign of correlation. N = 20; Spearman’s rho = −.0446; P = .049.

Supplementary Analyses

There was no significant correlation between BPp and PANSS, SWNS, GAF scores, and DUI at baseline.

Discussion

As expected, we found a significant negative correlation between the BPp of the caudate at baseline and clinical improvement of positive symptoms in 24 antipsychotic-naïve first-episode schizophrenia patients after 6 weeks of treatment with the relatively selective D2/3 antagonist amisulpride. Additionally, the fact that the patients with a good response had significantly lower baseline D2/3 BPp compared to nonresponders, even though the groups’ PANSS baseline scores did not differ, supports baseline D2/3 BPp as a potential marker for treatment outcome. The latter finding mentioned underlines the inability to differentiate good and poor responders based on baseline PANSS scores.

Our findings of a lower baseline BPp, interpreted as higher synaptic dopamine, that correlates with better 6 weeks medication response on positive symptoms are consistent with the previously mentioned study by Abi-Dargham et al,20 where an association between elevated synaptic dopamine and greater improvement of positive symptoms was demonstrated in 14 unmedicated patients after treatment with different antipsychotics. The present data are also in line with Demjaha et al’s11 study that shows a higher dopamine synthesis capacity in 12 responders vs 12 nonresponders to antipsychotic treatment. Together these studies indicate a variance in the dopamine disturbances with some patients having a high level of subcortical dopamine.

We chose to define responders based on an improvement on the PANSS positive score of more than 30%. This was in accordance with the study of Meisenzahl et al.57 However, we obtained a similar division in our patients—and the same results—if we defined the responders with a 50% improvement on the PANSS0–6.67,68 The responders improved significantly more on both the PANSS positive, total and general scales, although neither responders nor non-responders had any improvement of the negative symptoms. Not surprisingly, the responders also improved significantly more on GAF-S than nonresponders, although no significant differences were found regarding the change in GAF-F and SWNS. These findings suggest that even if patients experience a relief of positive symptoms, their level of functioning and well-being might not improve. A longer follow-up period would of course be necessary to make firm conclusions regarding final remission and recovery, but the present data emphasize the importance of considering improvement of positive symptoms vs adverse effects, particularly secondary negative symptoms from antipsychotic treatment.

Since the patients were all drug naïve a relatively low mean dose of amisulpride (238mg) was used in the present study. Dose and (S)-amisulpride were, as expected, well correlated with striatal occupancy. We observed a maximum occupancy of 80%. Even if the individually adjusted dose of amisulpride was administered to all patients at same time, we did not find any associations between the striatal occupancy and improvement on the PANSS, SWNS, or GAF. This is consistent with another [123I]-IBZM SPECT study of amisulpride.57

Significant correlations between striatal occupancy and outcome have, however, been supported by other PET and SPECT studies16,17,69–72 correlating striatal occupancy with improvement on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the PANSS positive and the Clinical Global Impression Scale. Possible explanations for the conflicting results are the different compounds and methodology used in the studies, small sample sizes, inclusion of a mix of schizophrenia patients and patients with schizophreniform disorder, and partly previously medicated patients. Moreover, these studies included patients with motor adverse effects and striatal occupancies above threshold, ie, the studies had a broader range in occupancy. Moreover, in several of the studies occupancy was calculated from baseline BP obtained from different subjects or from a subgroup of the patients. In the present study, BPp was measured at baseline in the antipsychotic-naïve state and at follow-up, which due to inter-individual differences gives a more precise estimate. Furthermore, our sample size was rather large, homogeneous and included only first-episode schizophrenia patients.

The present data did not replicate the previously mentioned findings of a negative correlation between the striatal occupancy and SWNS at follow-up. We did, however, find a negative correlation between striatal occupancy and functioning on the GAF-F score at follow-up. This could suggest that the more the dopamine receptors are blocked, the worse the functioning, which support the precaution we need to be aware of in treating patients.

Limitations and Strengths of the Data

Given that the antipsychotic-naïve patients had to go through an extensive examination programme we risk ending up with only the mildest cases. Even so, the patients included were moderately to severely ill with a total PANSS score of 81. Patients and controls in our study were not matched for smoking. The relationship between tobacco and enhancement of dopamine transmission has been reported, however changes in human studies are modest (5%–10%) and comparable to test-retest variability.73 A recent PET study did not find any significant effect of moderate smoking synthesis capacity in the striatum.74 Moreover, schizophrenia patients have a higher use of tobacco than HC, which is why matching for smoking would have added bias to either the patient or the HC group. Also, our primary outcomes were analyses within the patient group and these analyses were not affected by the lack of matching for smoking.

A few patients received a small amount of benzodiazepines during hospitalization, but none did so regularly and benzodiazepines were not allowed 12h prior to any of the examinations. Three patients, though, received benzodiazepine the evening prior to the baseline SPECT scan, and 2 of them had positive urine tests prior to the scan. Another limitation in the study was the spatial resolution of the SPECT images. Choosing an anatomic subdivision of striatum precludes identification of the total associative striatum. We focused on the caudate because PET imaging has identified the head of the caudate as the site of greatest dopamine excess in schizophrenia,8,9 and we assumed that our spatial resolution was sufficient to distinguish the caudate from the putamen.

The strengths of the study are: inclusion of solely antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia patients never previously exposed to antipsychotic compounds, the relatively large sample size, the longitudinal study design and the fact that the patients all went through a standardized treatment using antipsychotic monotherapy with a relatively selective D2/3 receptor antagonist (amisulpride).

Conlusion

The present data demonstrate a significant correlation between caudate D2/3 BPp and treatment response in a relatively large group of antipsychotic-naïve schizophrenia patients where low BPp associates with a better treatment response. Psychopathology at baseline did not predict treatment response and no associations between striatal D2/3 occupancy and clinical improvement were found. Finding possible prediction markers of treatment response would spare patients ineffective treatment and unnessecary adverse effects. Our findings are in agreement with the hypothesis of an association between treatment response to dopamine blockade and a hyperdopaminergic profile in the patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

Lundbeck Foundation (R13-A1349, R25-A2701); the Danish Medical Research Council; the Mental Health Services in the Capital Region of Denmark; and the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all patients and controls who participated in the study as well as the departments that helped in the recruitment process. The authors are grateful to our research nurses Gitte Saltoft Andersen and Katherina Alfsen, to research secretary Lisbeth Jensen and to the staff, in particular Annette Foldager, at the Department of Diagnostics, Section of Clinical Physiology and Nuclear Medicine, Glostrup Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark for the assistance in acquiring the SPECT scans and carrying out the blood analyses.

References

- 1. Hietala J, Syvälahti E, Vuorio K, et al. Presynaptic dopamine function in striatum of neuroleptic-naive schizophrenic patients. Lancet. 1995;346:1130–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, et al. Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9235–9240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, et al. Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2569–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abi-Dargham A, Gil R, Krystal J, et al. Increased striatal dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: confirmation in a second cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, Gil R, Kegeles L, Innis R. Increased dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: relationship to illness phases. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:56–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindström LH, Gefvert O, Hagberg G, et al. Increased dopamine synthesis rate in medial prefrontal cortex and striatum in schizophrenia indicated by L-(beta-11C) DOPA and PET. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McGowan S, Lawrence AD, Sales T, Quested D, Grasby P. Presynaptic dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia: a positron emission tomographic [18F]fluorodopa study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Howes OD, Montgomery AJ, Asselin MC, et al. Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kegeles LS, Abi-Dargham A, Frankle WG, et al. Increased synaptic dopamine function in associative regions of the striatum in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howes OD, Bose SK, Turkheimer F, et al. Dopamine synthesis capacity before onset of psychosis: a prospective [18F]-DOPA PET imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1311–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Demjaha A, Murray RM, McGuire PK, Kapur S, Howes OD. Dopamine synthesis capacity in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1203–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Egerton A, Chaddock CA, Winton-Brown TT, et al. Presynaptic striatal dopamine dysfunction in people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: findings in a second cohort. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seeman P, Staiman A, Chau-Wong M. The nerve impulse-blocking actions of tranquilizers and the binding of neuroleptics to synaptosome membranes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1974;190:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seeman P, Lee T. Antipsychotic drugs: direct correlation between clinical potency and presynaptic action on dopamine neurons. Science. 1975;188:1217–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farde L, Nordström AL, Wiesel FA, Pauli S, Halldin C, Sedvall G. Positron emission tomographic analysis of central D1 and D2 dopamine receptor occupancy in patients treated with classical neuroleptics and clozapine. Relation to extrapyramidal side effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:538–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, Remington G, Houle S. Relationship between dopamine D(2) occupancy, clinical response, and side effects: a double-blind PET study of first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Catafau AM, Corripio I, Pérez V, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy by risperidone: implications for the timing and magnitude of clinical response. Psychiatry Res. 2006;148:175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Laruelle M. Imaging dopamine transmission in schizophrenia. A review and meta-analysis. Q J Nucl Med. 1998;42:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, et al. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:776–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, et al. Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8104–8109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laruelle M. Imaging synaptic neurotransmission with in vivo binding competition techniques: a critical review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:423–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun W, Ginovart N, Ko F, Seeman P, Kapur S. In vivo evidence for dopamine-mediated internalization of D2-receptors after amphetamine: differential findings with [3H]raclopride versus [3H]spiperone. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quelch DR, Withey SL, Nutt DJ, Tyacke RJ, Parker CA. The influence of different cellular environments on PET radioligand binding: an application to D2/3-dopamine receptor imaging. Neuropharmacology. 2014;85:305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lieberman JA. Prediction of outcome in first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54(suppl):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crespo-Facorro B, Pelayo-Terán JM, Pérez-Iglesias R, et al. Predictors of acute treatment response in patients with a first episode of non-affective psychosis: sociodemographics, premorbid and clinical variables. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Levine SZ, Leucht S. Elaboration on the early-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic drug action: treatment response trajectories. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schennach-Wolff R, Meyer S, Seemüller F, et al. Influencing factors and predictors of early improvement in the acute treatment of schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1639–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crespo-Facorro B, de la Foz VO, Ayesa-Arriola R, et al. Prediction of acute clinical response following a first episode of non affective psychosis: results of a cohort of 375 patients from the Spanish PAFIP study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;44:162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Howes OD, Kapur S. A neurobiological hypothesis for the classification of schizophrenia: type A (hyperdopaminergic) and type B (normodopaminergic). Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stone JM, Raffin M, Morrison P, McGuire PK. Review: the biological basis of antipsychotic response in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:953–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rasmussen H, Ebdrup BH, Erritzoe D, et al. Serotonin2A receptor blockade and clinical effect in first-episode schizophrenia patients treated with quetiapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;213:583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ebdrup BH, Rasmussen H, Arnt J, Glenthøj B. Serotonin 2A receptor antagonists for treatment of schizophrenia. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20:1211–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Egerton A, Brugger S, Raffin M, et al. Anterior cingulate glutamate levels related to clinical status following treatment in first-episode schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2515–2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Demjaha A, Egerton A, Murray RM, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in schizophrenia associated with elevated glutamate levels but normal dopamine function. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:e11–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wolkin A, Barouche F, Wolf AP, et al. Dopamine blockade and clinical response: evidence for two biological subgroups of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:905–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pilowsky LS, Costa DC, Ell PJ, Murray RM, Verhoeff NP, Kerwin RW. Antipsychotic medication, D2 dopamine receptor blockade and clinical response: a 123I IBZM SPET (single photon emission tomography) study. Psychol Med. 1993;23:791–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Voruganti L, Slomka P, Zabel P, et al. Subjective effects of AMPT-induced dopamine depletion in schizophrenia: correlation between dysphoric responses and striatal D(2) binding ratios on SPECT imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:642–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heinz A, Knable MB, Coppola R, et al. Psychomotor slowing, negative symptoms and dopamine receptor availability—an IBZM SPECT study in neuroleptic-treated and drug-free schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Res. 1998;31:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bressan RA, Costa DC, Jones HM, Ell PJ, Pilowsky LS. Typical antipsychotic drugs—D(2) receptor occupancy and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2002;56:31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. de Haan L, Lavalaye J, van Bruggen M, et al. Subjective experience and dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients treated with antipsychotics: clinical implications. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marder SR. Subjective experiences on antipsychotic medications: synthesis and conclusions. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2005;427:43–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Naber D. A self-rating to measure subjective effects of neuroleptic drugs, relationships to objective psychopathology, quality of life, compliance and other clinical variables. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10(suppl 3):133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. de Haan L, Lavalaye J, Linszen D, Dingemans PM, Booij J. Subjective experience and striatal dopamine D(2) receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia stabilized by olanzapine or risperidone. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1019–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mizrahi R, Rusjan P, Agid O, et al. Adverse subjective experience with antipsychotics and its relationship to striatal and extrastriatal D2 receptors: a PET study in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:630–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haber SN, Kim KS, Mailly P, Calzavara R. Reward-related cortical inputs define a large striatal region in primates that interface with associative cortical connections, providing a substrate for incentive-based learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8368–8376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stone JM, Bressan RA, Erlandsson K, Ell PJ, Pilowsky LS. Non-uniform blockade of intrastriatal D2/D3 receptors by risperidone and amisulpride. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2005;180:664–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nielsen MØ, Rostrup E, Wulff S, et al. Alterations of the brain reward system in antipsychotic naïve schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nielsen MO, Rostrup E, Wulff S, et al. Improvement of brain reward abnormalities by antipsychotic monotherapy in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1195–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Düring S, Glenthøj BY, Andersen GS, Oranje B. Effects of dopamine D2/D3 blockade on human sensory and sensorimotor gating in initially antipsychotic-naive, first-episode schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:3000–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Glenthoj BY, Mackeprang T, Svarer C, et al. Frontal dopamine D(2/3) receptor binding in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenic patients correlates with positive psychotic symptoms and gender. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Albrecht DS, Skosnik PD, Vollmer JM, et al. Striatal D(2)/D(3) receptor availability is inversely correlated with cannabis consumption in chronic marijuana users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schoemaker H, Claustre Y, Fage D, et al. Neurochemical characteristics of amisulpride, an atypical dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist with both presynaptic and limbic selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:83–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Naber D, Moritz S, Lambert M, et al. Improvement of schizophrenic patients’ subjective well-being under atypical antipsychotic drugs. Schizophr Res. 2001;50:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chouinard G, Margolese HC. Manual for the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS). Schizophr Res. 2005;76:247–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Meisenzahl EM, Schmitt G, Gründer G, et al. Striatal D2/D3 receptor occupancy, clinical response and side effects with amisulpride: an iodine-123-iodobenzamide SPET study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2008;41:169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kung HF, Alavi A, Chang W, et al. In vivo SPECT imaging of CNS D-2 dopamine receptors: initial studies with iodine-123-IBZM in humans. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:573–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Seibyl JP, Woods SW, Zoghbi SS, et al. Dynamic SPECT imaging of dopamine D2 receptors in human subjects with iodine-123-IBZM. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1964–1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Carson RE, Channing MA, Blasberg RG, et al. Comparison of bolus and infusion methods for receptor quantitation: application to [18F]cyclofoxy and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:24–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Seibyl JP, Zea-Ponce Y, Brenner L, et al. Continuous intravenous infusion of iodine-123-IBZM for SPECT determination of human brain dopamine receptor occupancy by antipsychotic agent RWJ-37796. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zea-Ponce Y, Laruelle M. Protein precipitation: an expedient procedure for the routine analysis of the plasma metabolites of [123I]IBZM. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Willendrup OP, Pinborg LH, Hasselbalch SG, Adams KH, Stahr K, Knudsen GM. Assessment of the precision in co-registration of structural MR-images and PET-images with localized binding. Anonymous. International Congress Series. 2004. 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Svarer C, Madsen K, Hasselbalch SG, et al. MR-based automatic delineation of volumes of interest in human brain PET images using probability maps. Neuroimage. 2005;24:969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Farde L, Wiesel FA, Stone-Elander S, et al. D2 dopamine receptors in neuroleptic-naive schizophrenic patients. A positron emission tomography study with [11C]raclopride. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Obermeier M, Schennach-Wolff R, Meyer S, et al. Is the PANSS used correctly? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Leucht S. Measurements of response, remission, and recovery in schizophrenia and examples for their clinical application. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(suppl 1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nordström AL, Farde L, Wiesel FA, et al. Central D2-dopamine receptor occupancy in relation to antipsychotic drug effects: a double-blind PET study of schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33:227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Agid O, Mamo D, Ginovart N, et al. Striatal vs extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors in antipsychotic response—a double-blind PET study in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kegeles LS, Slifstein M, Frankle WG, et al. Dose-occupancy study of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors by aripiprazole in schizophrenia with PET and [18F]fallypride. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3111–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kessler RM, Woodward ND, Riccardi P, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor levels in striatum, thalamus, substantia nigra, limbic regions, and cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:1024–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Thomsen G, Knudsen GM, Jensen PS, et al. No difference in striatal dopamine transporter availability between active smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers using [123I]FP-CIT (DaTSCAN) and SPECT. EJNMMI Res. 2013;3:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Bloomfield MA, Pepper F, Egerton A, et al. Dopamine Function in Cigarette Smokers: an [F]-DOPA PET Study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2397–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Crespo-Facorro B, Roiz-Santiáñez R, Pelayo-Terán JM, et al. Caudate nucleus volume and its clinical and cognitive correlations in first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;91:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.