Abstract

Insulin resistance and abdominal obesity are present in the majority of people with the metabolic syndrome. Antioxidant therapy might be a useful strategy for type 2 diabetes and other insulin-resistant states. The combination of vitamin C (Vc) and vitamin E has synthetic scavenging effect on free radicals and inhibition effect on lipid peroxidation. However, there are few studies about how to define the best combination of more than three anti-oxidants as it is difficult or impossible to test the anti-oxidant effect of the combination of every concentration of each ingredient experimentally. Here we present a math model, which is based on the classical Hill equation to determine the best combination, called Fixed Dose Combination (FDC), of several natural anti-oxidants, including Vc, green tea polyphenols (GTP) and grape seed extract proanthocyanidin (GSEP). Then we investigated the effects of FDC on oxidative stress, blood glucose and serum lipid levels in cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes, high fat diet (HFD)-fed rats which serve as obesity model, and KK-ay mice as diabetic model. The level of serum malondialdehyde (MDA) in the treated rats was studied and Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) staining or Oil red slices of liver and adipose tissue in the rats were examined as well. FDC shows excellent antioxidant and anti-glycation activity by attenuating lipid peroxidation. FDC determined in this investigation can become a potential solution to reduce obesity, to improve insulin sensitivity and be beneficial for the treatment of fat and diabetic patients. It is the first time to use the math model to determine the best ratio of three anti-oxidants, which can save much more time and chemical materials than traditional experimental method. This quantitative method represents a potentially new and useful strategy to screen all possible combinations of many natural anti-oxidants, therefore may help develop novel therapeutics with the potential to ameliorate the worldwide metabolic abnormalities.

Keywords: Insulin resistance, Abdominal obesity, Anti-oxidants, Quantitative combination, Hill function, High fat diet-fed rats and KK-ay mice

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a disorder of energy utilization and storage, and a constellation of cardiovascular risk factors including abdominal obesity, elevated blood pressure, elevated fasting plasma glucose, high serum triglycerides, dyslipidemia, and low high-density cholesterol (HDL) levels, etc. Insulin resistance and abdominal obesity are present in the majority of people with metabolic syndrome. Obesity is a major risk factor for Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [6] which has two most common features: high blood glucose (hyperglycemia) and hyperlipidemia. Hyperglycemia is a result of the body being unable to produce enough insulin, or not being able to use the insulin properly (insulin resistance).

Obesity-related disorders is linked with the change of redox status with increased oxidative stress in adipose tissue. Oxidative stress in adipocytes plays a central role in T2DM and obesity-caused insulin resistance [26]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), the radical forms of oxygen and the by-products of mitochondrial respiration and enzymatic oxidases, can act as signaling molecules. ROS are also a common feature of insulin resistance [13]. Therefore, antioxidant therapy might be a useful strategy for type 2 diabetes and other insulin-resistant states. Studies showed that many anti-oxidants exhibited protective effect on preadipocytes exposed to oxidative stress [11]. Some anti-oxidants, such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and manganese (III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP), showed dose-dependent suppression of insulin resistance [13], while others, such as green tea catechins (GTCs), GTP, GSEP, etc. which are associated with a lower risk of obesity, can modulate fat metabolism [27], and ameliorate pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and death in HFD-induced diabetic rats [4]. Some antioxidants, such as Vc supplementation, can ameliorate some aspects of the obesity-diabetes syndrome in fat hyperglycemic mice [1] and may be beneficial in preventing the development of diabetic nephropathy.

It has been known that, the combination of Vc and vitamin E has synthetic scavenging effect on free radicals and inhibition effect on lipid peroxidation. However, there are few studies about how to define the best combination of more than three anti-oxidants because it is difficult to test the anti-oxidant effect of the combination of every concentration of each ingredient experimentally.. The question whether the combined administration of these anti-oxidants appears to be essential to reinforce the anti-oxidative effect of single component keeps open.

To address this question, we at first present a math model which is based on the classical Hill equation to get the best combination, which is called FDC, of several natural anti-oxidants Vc, GSEP and GTPs, after the measurement of scavenging effect of these components with different doses on hydroxyl free radicals.

Complex diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, can be induced by either genetic factors or environmental and lifestyle factors, or a combination of both. We investigated the effects of FDC on oxidative stress, blood glucose and serum lipid levels in cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes, Diet-Induced Obese rats (DIO rats) and KK-ay mice. DIO rats here serve as an obesity model caused by environmental factors, while KK-ay mice a diabetic model caused by genetic factors. We tested the hypothesis that FDC reduces the fat mass and oxidative stress in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, KK-ay mice and DIO rats. Finally, the level of serum MDA in the treated rats was studied and the HE or Oil red slices of liver and adipose tissue in the rats were examined to study whether FDC can inhibit lipid peroxidation and reduce fat accumulation in different tissue.

Our quantitative model can be used to determine the best combination of many natural anti-oxidants. It represents a potentially novel and useful strategy to screen all possible combinations of many natural anti-oxidants, therefore may help develop novel therapeutics with the potential to ameliorate the worldwide metabolic abnormalities.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Cell culture media and supplements were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and newborn calf serum were purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY). 2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA). All anti-oxidants, including Proanthocyanidins (20% glycerin dissolved), Vitamin E powder, Vitamin C, Grape seed extract, Grape skin extract, Oligo Proanthocyanidin (OPC>=85%) and Tea Polyphenol, were purchased from TianJin JianFeng Natural Product R&D Co., Ltd., Tianjin, PR China. The precise composition and purity of these compounds are shown in Table S1 (for OPC), S2 (for Tea Polyphenol) and S3 (for Grape skin extract), respectively. All other chemicals made in China were of analytical grade.

2.2. Assay for the scavenging effect on hydroxyl radical generated from Fenton reaction system

The HO• scavenging activity was assessed according to previous reference with slight modification [16]. HO• was generated by a Fenton-type reaction at room temperature. The reaction mixture (1.0 mL) contained 600 μL of luminol (0.1 mM, diluted in the carbonic acid-buffered saline solution (CBSS, pH 10.2), 100 μL of sample solution (with different concentrations, replaced with CBSS in the control), 200 μL of Fe2+–EDTA (3 mM), and 100 μL of H2O2 (1.2 mM). Initiation of the reaction was achieved by adding Fe2+–EDTA and then H2O2 into the mixture.

The HO• scavenging abilities of all anti-oxidants mentioned above were assessed by the chemiluminescent method. The chemiluminescence (CL) intensity integral was recorded and the inhibitory rate was obtained according to the formula: inhibitory rate (%)=[(CLcontrol−CLsample)×100]/CLcontrol.

2.3. Math model to determine FDC

The process of Initiation and inhibition of free radical processes can be described by the Hill equation [12].

where x is the final concentration of FDC (unit: μg/ml); is the free radical scavenging percentage when the concentration of FDC is x; a, the log value of the FDC concentration, is the concentration of x when the curve reaches the maximum; n determines the curvature of the curve (n>0). y=0.5 when n=0; y can be 0 or 1 when n=+∞; and k determines the IC50, the concentration of x when 50% of free radical were scavenged:

For more details, please check the Supplementary online materials.

2.4. Cell culture and treatment

3T3-L1 fibroblastic cells (preadipocytes) were cultured and maintained in culture medium (DMEM supplemented with 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 75 μg/ml penicillin, and 10% newborn calf serum) at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere. 3T3-L1 preadipocytes were induced and differentiated into adipocytes as described before with slight modification [26].

Completely confluent plates were incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS with 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 10 μM dexamethasone and 0.5 μg/ml insulin. Two days after incubation, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5 μg/ml insulin. Fresh culture medium was added after 2 days and then every other day till the cells attained adipocyte morphology identified by Oil Red O stai4ning.

2.5. Measurement of intracellular ROS induced by DEX or TNF-α in adipocytes

Fully differentiated adipocytes were incubated with DEX or TNF-α to induce intracellular ultra ROS generation as a model in high level oxidative stress state [27]. 3T3-L1 cells treated with DEX or TNF-α and FDC were used to measure the effect of FDC, while cells without any treatment as control. Fully differentiated adipocytes were incubated with cell-permeable, oxidation-sensitive and non-fluorescent reagent DCFH-DA (final concentration 10 μmol/L for 30 min at 37 °C). Oxidation of DCFH-DA by peroxides yielded fluorescent derivative dichlorofluorescein (DCF), which acts as a control for changes in uptake, ester cleavage, and efflux, to detect intracellular ROS content change.

FDC treatment: concentration gradient of FDC was applied with adipocytes for 24 h to attenuate oxidative stress stimulated by DEX or TNF-α. The measured fluorescence values were expressed as a percentage of fluorescence in control cells.

The intracellular ROS levels were measured by Flow Cytometry (BD FACS Calibur), at excitation wavelength of 488 nm and emission wavelength of 525 nm, after the loaded cells were washed three times.

2.6. DIO rat model establishment, FDC treatment and the measurement of physiological and biochemical parameters

Four-week-old male SD rats were purchased from Vital River Laboratories (VRL), China, and housed in a SPF (specific pathogen free) environment in the range of (40–70)% Relative Humidity (RH), (20–26) °C, with a 14/10 h light–dark cycle. All rats were raised, one rat per cage, for 7 days at first, to allow their adaptation to the environment.

All rats were divided into two groups randomly. One group was fed a chow diet while the other was fed high fat diet (15% saturated fat, 1% cholesterol, 84% chow diet) for four weeks. To determine whether the fat model was established, the following indicator was used:

(Body weight of DIO rat-body weight of normal rat)/body weight of normal rat=20%.

Normally the DIO rat model can be established after 30 days high-diet-fat feeding. Thereafter, each group was further subdivided into 2 subgroups, 6 rats per subgroup. One subgroup fed with FDC while the other not: vehicle-treatment+chow diet feeding group (Control),

FDC(100 mg/kg/day-treatment)+chow diet feeding group (Control+FDC),

Vehicle-treatment+high fat diet feeding group (fat),

FDC (100 mg/kg/day-treatment)+high fat diet feeding group (Fat+FDC).

Rats were fed further with intragastric administration for 30 days. The body weight, food and water intakes by the animal and nutritional status of all subgroups were measured every day and compared.

2.6.1. Blood glucose measurement and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

After all rats were fasted overnight, they were orally given glucose (3 g per kg body weight). Blood glucose was measured at 6 different time points: 0 h, 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 1.5 h and 2 h. Blood glucose concentrations, including FBG (Fasting Blood Glucose, the rats were fasted 8–10 h before cutting the tail and measuring the blood glucose), PBG (2-h Postprandial Blood Glucose), and RBG (Random Blood Glucose), of the tail vein were measured using GT-1920 blood glucose meter (ARKRAY Inc., Shiga, Japan). Normally the blood sugar value will reach the peak at 30 min.

2.6.2. Triglycerides (TG) measurement in liver

The liver was removed, weighed and rapidly washed in cold saline (0.9%) 2–3 times. Total lipids were extracted from liver and measured using the method described before [9] with slight modification. The connective tissue at liver surface was removed before the liver was shredded. Next, liver tissue was washed by saline several times and 400 mg liver tissue was homogenized by using ice-cold n-heptane: isopropyl acetone=2:3.5. Then the homogenate was centrifuged at 3 k rpm for 10 min, before TG was measured in the supernatant.

2.7. Measurement of lipid peroxidation in serum in DIO rat

The level of lipid peroxidation was measured by determining TBARS (Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances), as TBARS is still a popular method to use. Therefore the level of lipid peroxidation in this investigation was measured by TBARS, as previously described [27].

2.8. Morphological and histological examination in DIO rat

After animal euthanasia, epididymal and perirenal fat pad as well as livers were taken out and photographed. Small pieces of fat tissue were fixed immediately in 10% buffered formalin. After paraffin embedding, 5 μm sections were deparaffinized in xylene and were rehydrated through a series of decreasing concentrations of ethanol. Sections were stained with HE staining. Alternatively, portions of fresh liver were flash-frozen and cryostat sections were cut and prepared for Oil Red O staining. Photomicrographs of all sections were taken with an ECLIPSE 90i microscope (Nikon, Japan).

2.9. T2DM KK-ay mouse model establishment, FDC treatment and measurement of physiological and biochemical parameters

Eight-week-old female KK-ay (28–32 g) and C57BL/6J mice (B6 mice, as control) were purchased from Vital River Laboratories, China, and housed in a SPF environment in the range of (40–70)% RH, (20–26) °C, with a 14/10 h light–dark cycle. All KK-ay mice were fed with a high fat diet (15% saturated fat, 1% cholesterol, 84% chow diet) for 1 week to allow adaptation to the environment and diet. Meanwhile, B6 mice were fed with a chow diet for 1 week.

KK-ay mice were confirmed to be successful model of type 2 diabetes at 9 weeks of age (the random blood glucose concentration >16.6 mM). Then mice were randomly divided into 4 groups base on gavage:

Vehicle-fed C57BL/6J (B6)+chow diet feeding group (Control),

Vehicle-fed KK-ay (DM)+High Fat Diet feeding group,

FDC 2 mg/ 10 g/day-fed (DM+FDC low)+High Fat Diet feeding group, (FDC low: low dose of FDC),

FDC 8 mg/10 g/day-fed (DM+FDC high)+High Fat Diet feeding group. (FDC high: high dose of FDC).

Mice were treated with FDC once a day for 4 weeks by gavage. Blood glucose concentrations of the tail vein were measured with Super Glucocard II glucometer in the end. The food and water intakes by the animal and nutritional status of the animal groups were measured every day and were compared. 11 parameters were measured as indicated in Section 2.6.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate or more. The statistical analysis was performed using software OriginPro (OriginLab Corp.). Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). A probability level of 5% (p<0.05) was considered to be significant. The significance of difference versus the control group was determined by Student's t-test.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of the scavenging effects of single ingredient on free radicals

In order to find the best combination ratio of anti-oxidants vitamin C, GSEP and GTPs using math model, we at first need to measure the scavenging effects of single ingredient on hydroxyl free radicals.

3.1.1. Scavenging effect of single ingredients on hydroxyl radicals

We selected eight different ingredients or extracts (Table 1) to test their antioxidant effect of scavenging Hydroxyl Radicals (HO•). With regression equations derived, IC50 values of single ingredients were calculated for Group 3 (Oligo Proanthocyanidin, Tea Polyphenol and Vitamin C) in Table 1, and their scavenging effects are shown in Fig. S1.

Table 1.

The scavenging effect of FDC single ingredients on hydroxyl radicals.

| Group | Single ingredients | IC50 hydroxyl |

|---|---|---|

| Group 1: glycerin solution | Proanthocyanidins (20% glycerin dissolved) | 0.26 μg/ml |

| Vitamin E (100% glycerin dissolved) | 100.35 fold diluted | |

| Vitamin E powder (20% glycerin dissolved) | 16 μg/ml | |

| Group 2: aqueous solution (diluted) | Grape skin liquid (color value ) | 102.1 fold diluted |

| Grape skin red segment solution (color value ) | 105.3 fold diluted | |

| Group 3: aqueous solution (powder, diluted) | Oligo Proanthocyanidin (OPC>=85%) | 0.08 μg/ml |

| Tea polyphenol | 0.4 μg/ml | |

| Vitamin C | 0.04 μg/ml |

3.1.2. Scavenging effect of double ingredients on hydroxyl radical

Next we tested the scavenging effect of the combination of every two ingredients among the three on Hydroxyl free radicals, respectively. We chose the concentration of every combination manually based on our priori knowledge. With regression equations derived, IC50 values of double ingredients were calculated (Table 2).

Table 2.

The scavenging effect of double ingredients on hydroxyl radicals.

| Double ingredients | Concentration ratio | IC50 on hydroxyl radicals |

|---|---|---|

| OPC:Vc | 10:1 | 0.07 |

| 8:1 | 0.08 | |

| TP:Vc | 10:1 | 0.09 |

| 8:1 | 0.07 | |

| OPC:TP | 1:1 | 0.08 |

| 2:1 | 0.06 | |

| 3:1 | 0.04 | |

| 1:2 | 0.50 | |

| 1:3 | 0.07 |

Note: OPC: Oligoprocyanidins; TP: Tea polyphenol; Vc: Vitamin C.

3.1.3. Scavenging effect of three ingredients on hydroxyl radicals to determine the FDC

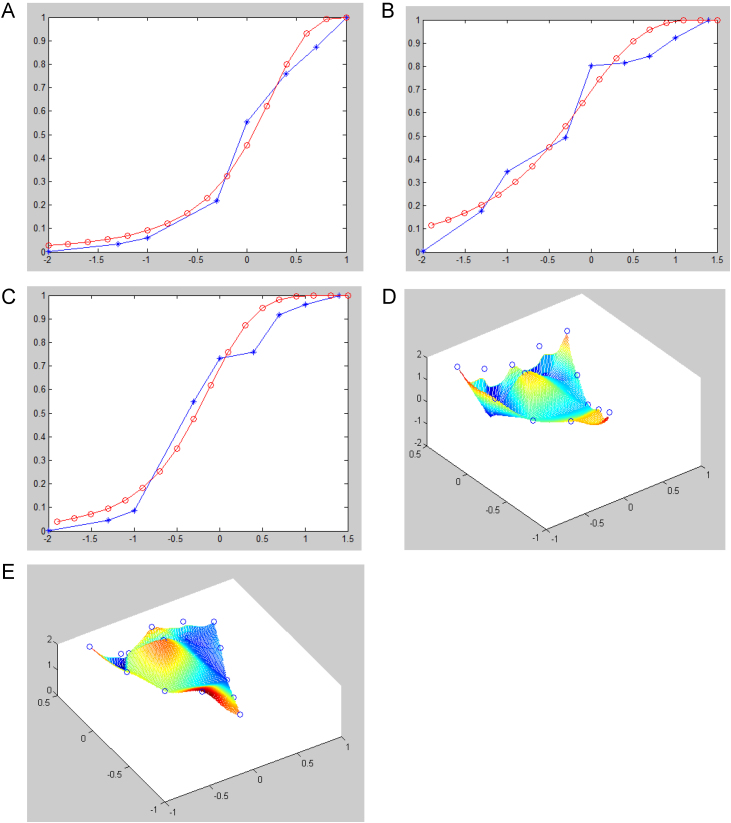

In order to determine the FDC, we tested the scavenging effect of several combinations (that is, concentration ratio) of all three ingredients on hydroxyl free radicals. Next we applied the math model, which is based on the classical Hill function that has been used to predict the rate of product formation in enzymatic reactions for more than one hundred years, to find the best combination of three ingredients to scavenge free radicals. We modified the initial condition of the equation slightly. With regression equations derived, IC50 values of three ingredients were calculated (Fig. 1 and Figs. S1–S9) and the best ratio for OPC, TP and Vc was obtained as OPC: TP: VC=0.224: 0.704: 0.072.

Fig. 1.

The scavenging effect of three single ingredients (OPC, Vc and TP) on hydroxyl radicals. (A–C) The scavenging effect of OPC (A), TP (B) and Vc (C) on hydroxyl radicals, respectively. X axis: the log value of single ingredient concentration. Y axis: the scavenging percentage. (D and E). The fitting of parameter a(D), k(E) in Hill's function, respectively. X axis: The first main component. Y axis: the second main component. Z axis: the parameter a, k or n.

3.2. FDC reduced the intracellular ROS induced by DEX or TNF-α

3.2.1. Inhibition effect of FDC on ROS in adipocyte cells

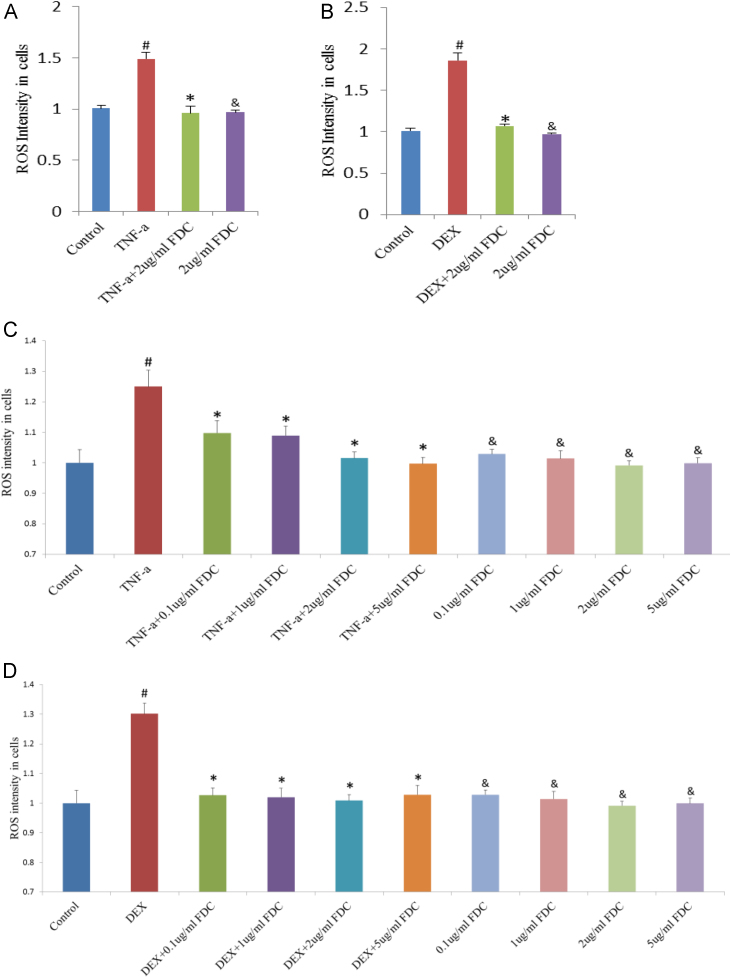

The cell-permeable and non-fluorescent redox-sensitive dye DCFH-DA can be oxidized by peroxides to yield DCF whose fluorescence intensity can be treated as the indicator for intracellular oxidative stress. With 40 ng/ml TNF-α (Fig. 2A) or 20 nM DEX (Fig. 2B) exposure for 24 h in adipocytes, the ROS level was increased significantly (red bar, Fig. 2A and B), while TNF-α or DEX with 2 μg/ml FDC were added into adipocytes, ROS level decreased significantly (green bar, Fig. 2A and B), indicating that FDC can reduce intracellular ROS.

Fig. 2.

Effect of FDC on intracellular ROS generation of 3T3-L1 adipocytes detected by Flow Cytometry (FCM). Data are expressed as means±S.D. from at least three independent experiments. ROS level was detected by DCFH-DA, in 24 h after FDC and DEX (B and D) incubation, or FDC and TNF-α (A and C) incubation. # indicates the significant difference between DEX or TNF-α group (red) and control group (deep blue) (P<0.05); * indicates the significant difference between DEX or TNF-α group (red) and FDC with DEX or TNF- α group (P<0.05); & indicates the significant difference between DEX or TNF-α group (red) and FDC group (P<0.05). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Next, we tested how the concentration gradient of FDC could influence the oxidative stress stimulated by DEX or TNF-α. The range of treated concentration of FDC used in experiments was from 0.1 to 5 μg/ml. With the increased concentration, the ROS intensity declined increasingly (Fig. 2C). The oxidative stress stimulated by TNF-α (Fig. 2C) or DEX (Fig. 2D) was attenuated by FDC administration.

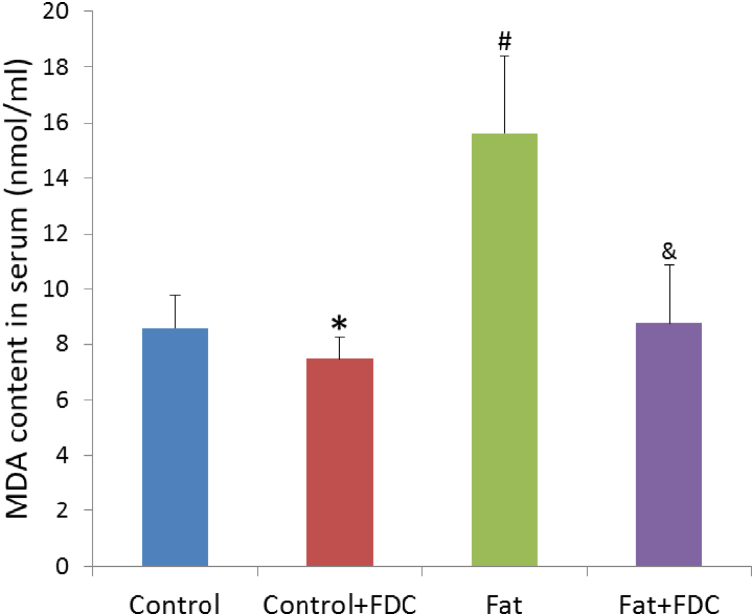

3.2.2. Inhibition effects of FDC on lipid peroxidation in serum of DIO rats

There is a close relationship between the increase of free radicals and lipid peroxidation in the progress of diabetes [21]. As by-product of lipid peroxidation, MDA reflects the degree of oxidation in the body [28]. Therefore MDA was used to test whether FDC could inhibit lipid peroxidation in adipose tissue of DIO rats. In this investigation, fat rat model was successfully established after 2 months HFD feeding. Then we showed that FDC treatment has no significant effect on water or food intake (Fig. S10).

FDC feeding decreased MDA content in serum significantly, thus ameliorated the oxidative stress in DIO rats (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

FDC feeding decreased MDA content in serum of DIO rats. MDA values (nmol/ml) in serum are expressed by mean±SD of 6 animals per group for each measurement. * and & indicate a significant difference between FDC feeding and vehicle feeding groups (P<0.05). # indicates a significant difference between chow diet control and high fat diet feeding groups (P<0.05).

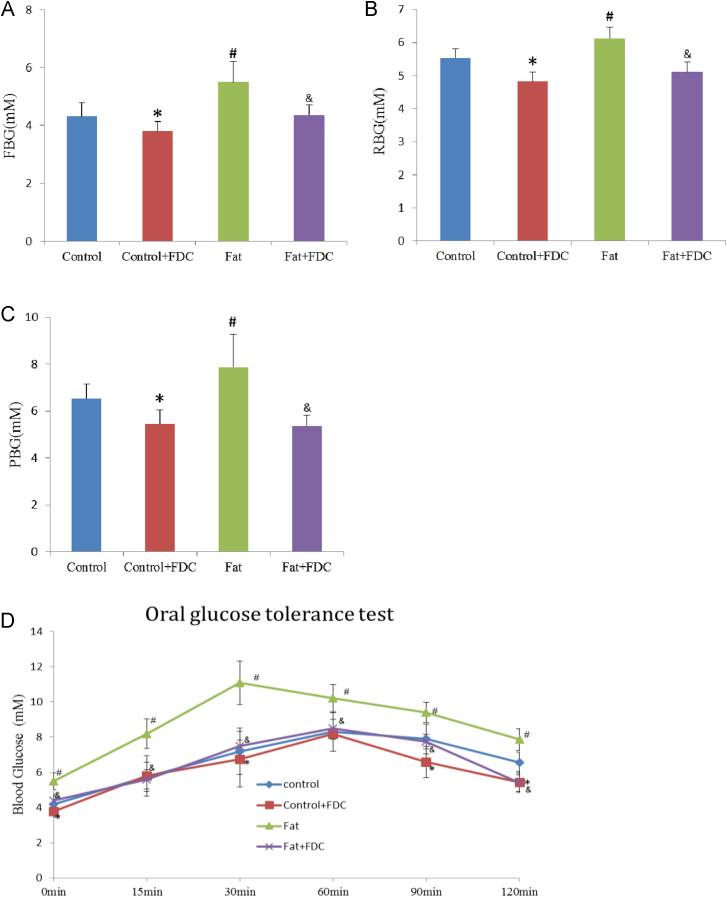

3.3. FDC reduced blood glucose level in DIO rat model

Blood glucose level is an important index for diabetes. In DIO rats, high-fat diet increased blood glucose level significantly compared to the control, while FDC gavage administration decreased blood glucose content in DIO rats (Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of FDC on lowering blood glucose content of DIO rats. FDC administration decreased fasting blood glucose content (FBG) (A), random blood glucose (RBG) (B) and 2-h postprandial blood glucose content (PBG) (C). (D) FDC administration increased glucose tolerance of DIO rats. * and & indicate a significant difference between FDC feeding and vehicle feeding groups (P<0.05); # indicates a significant difference between chow diet control and high fat diet feeding groups (P<0.05).

To test the glucose tolerance in rats, the blood glucose level at time point 0 min, 15 min, 30 min, 60 min, 90 min and 120 min was measured in OGTT test (Fig. 4C). FDC treatment group restored normal glucose tolerance and the ability to regulate blood glucose (Fig. 4D). These data implied that FDC administration can increase glucose absorption or metabolic transformation in DIO animals, consequently lower blood glucose level.

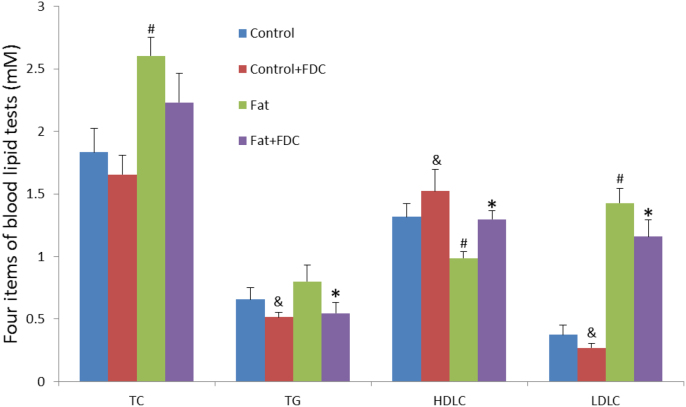

3.4. FDC ameliorated lipid disorders in DIO rats

Lipid disorders are associated with an increased risk for vascular disease, especially strokes and heart attacks. As abnormalities in lipid disorders are a combination of genetic predisposition as well as the nature of dietary intake, we'd plan to study the effect of FDC on lipid disorder either in DIO rat model (in this section), which was set up by HFD, or in KK-ay mouse model, a useful spontaneous animal model to evaluate pathogenesis and treatment of human type 2 diabetic nephropathy (in Section 3.7). Here we focus on the investigation of four indicators: blood total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) in DIO rat model.

In Fig. 5, HFD increased significantly the TC and LDL level in the Fat group (green bar), but reduced significantly the HDL-C level (p<0.05), comparing with that in control group (blue bar). In the group fed with HFD and FDC at the same time (purple bar), TG and LDL level decreased significantly (p<0.05), and HDL-C level increased significantly comparing with that in Fat group (p<0.05), thus very different from those in Fat group.

Fig. 5.

FDC administration ameliorated lipid disorders in DIO rats. Values are mean±SD of 6 animals per group for each measurement. * and & indicate a significant difference between FDC feeding and vehicle feeding groups (P<0.05); # indicates a significant difference between the control group B6 mice or chow diet control and high fat diet feeding group (P<0.05). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The fact that blood TG level did not increase to a significant level in Fat group (green bar), comparing with that in control group (p=0.10431), implied that HFD did not change blood TG level that much. When fed with HFD and FDC at the same time, the average TC level is not significantly different from that in the group fed with HFD (p=0.06838), indicating that FDC can not lower TC level in a very good manner.

In summary, FDC lowered LDL-C and raised HDL-C significantly in DIO rat model, without an obvious effect to lower TC level.

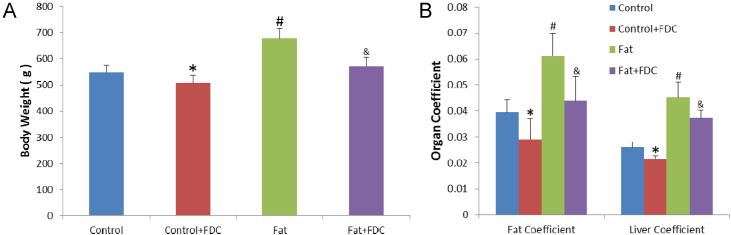

3.5. FDC significantly reduced HFD-induced fat accumulation and liver coefficient

After one-month FDC treatment, the pathological alterations of livers from different groups were evaluated by morphologic and histological examination (HE and Oil Red O staining) at first. Long-term HFD feeding increased significantly body weight (green bar in Fig. 6A), average Fat Coefficient, and Liver Coefficient (green bar in Fig. 6B) in Fat group, thus induced massive hepatic steatosis comparing with those in six rats in control group (p<0.05).

Fig. 6.

FDC administration lowered body weight (A), Fat Coefficient and Liver Coefficient (B) in DIO rats. * and & indicate a significant difference between FDC feeding and vehicle feeding groups (P<0.05). # indicates a significant difference between chow diet control and high fat diet feeding groups (P<0.05). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In Fat+FDC group (purple bar), average body weight decreased significantly to 571±34 g, average Fat Coefficient was reduced significantly to (4.39±0.9)%, and the average Liver Coefficient was significantly reduced to (3.5±0.29)%, comparing with those in Fat group (p<0.05), indicating that FDC can indeed reduce the extra body weight (declined 15.5%), fat content (declined 28%) and liver hyperplasia (declined 17.5%) in DIO rats (Fig. 6). Therefore, HFD-induced increase in fat or liver/body weight ratio was significantly alleviated by FDC supplemented to HFD.

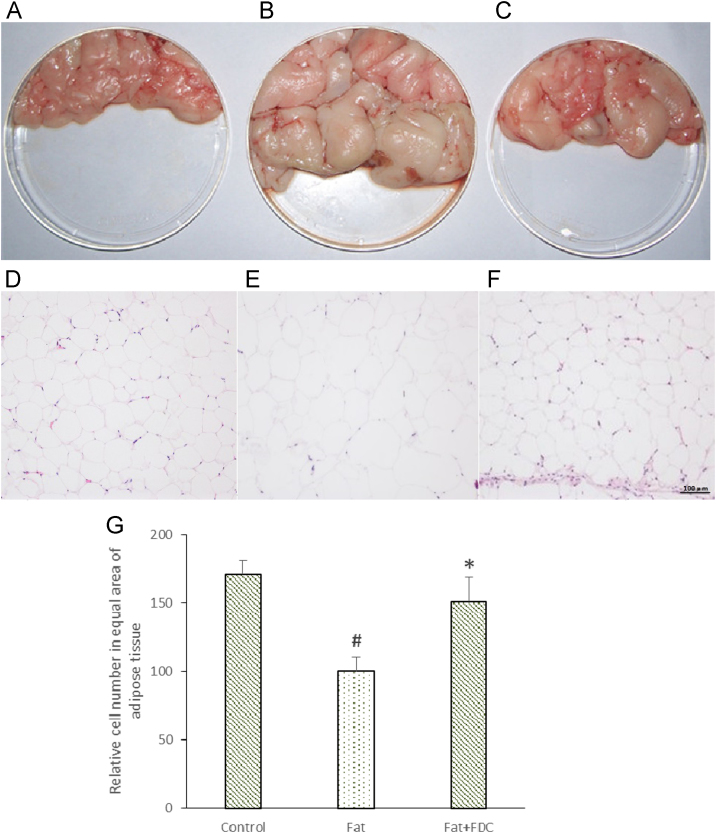

3.6. FDC reduced visceral fat (epididymal, perirenal) and liver lipid accumulation in DIO rats

Visceral fat accumulation is an important characteristic of metabolism syndrome. Here we investigated how the visceral fat changed after rats were fed with FDC. At first we compared the morphological change of epididymal and perirenal white adipose tissue (e+p WAT) in Control group (Fig. 7A), Fat group (Fig. 7B) and Fat+FDC group (Fig. 7C). Obviously, long term HFD feeding significantly increased the volume of visceral fat – the total mass of e+p WAT tissue (Fig. 7B), while administration with FDC reduced the total amount of fat in e+p WAT tissue (Fig. 7C). Paraffin sections show that rats have larger adipocyte size in Fat group (Fig. 7E) than that in Control group (Fig. 7D), while in Fat+FDC group, the size of cells in adipose tissue decreased significantly (Fig. 7F). The quantitative analysis also showed that the relative cell number of adipose tissue in Fat+FDC group is significantly larger than that in Fat group in the equal area (Fig. 7G and F).

Fig. 7.

FDC administration changed the morphology and reduced the cell volume of epididymal and perirenal white adipose tissue in DIO rats. (A–C) The morphological photograph of epididymal and perirenal white adipose tissue in Control group (A), Fat group (B) and Fat+FDC group (C). (D–F) H&E staining photomicrographs of the adipose tissue in liver paraffin section in Control group (D), Fat group (E) and Fat+FDC group (F). (G) The relative cell number in adipose tissue of same area in Fat+FDC group is much larger than that in Fat group.

Values are means±SD (n=6). The values with #, * are significantly different from those of control group or Fat group at P<0.05.

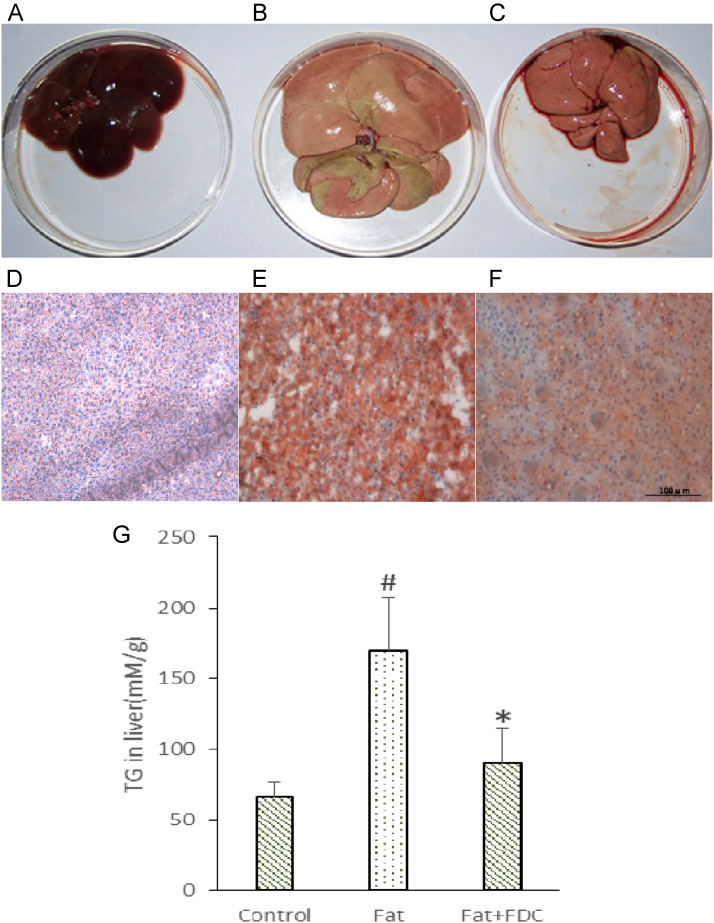

Next we compared the morphological change of liver tissue. Long term HFD feeding significantly increased the volume of liver (Fig. 8). Every single piece of liver in Fat group (Fig. 8B) is much larger than that in control group and Fat+FDC group (Fig. 8A and C). In Fat group, the liver tissue has more fat accumulation (Fig. 8B), while less in and around liver tissue which keeps almost the normal morphology in Fat+FDC group (Fig. 8C). Paraffin sections were stained with a lipid-soluble dye Oil Red O, which is the reliable and standard method to visualize lipids in tissues [24]. The frozen section photomicrographs of liver tissue also showed that FDC reduces fat accumulation of liver tissue in Fat+FDC group (Fig. 8E and F). The quantitative analysis also showed that TG content in Fat+FDC group is significantly lower than that in Fat group (Fig. 8G). Taken together, these data indicated that FDC reduced the fat accumulation in liver, in line with the significant decrease of Liver Coefficient in Section 3.5.

Fig. 8.

FDC administration changed the morphology and reduced the TG content of liver tissue in DIO rats. (A–C) The morphological photograph of Liver in Control group (A), Fat group (B) and in Fat+FDC group (C). (D–F) The photomicrographs of frozen section of Liver in Control group (D), Fat group (E) and in Fat+FDC group (F) with Oil Red O staining. (G) The liver TG content in Fat group is significantly higher than that in Fat+FDC group. Values are means±SD (n=6). The values with #, * are significantly different from those of control group or Fat group at P<0.05.

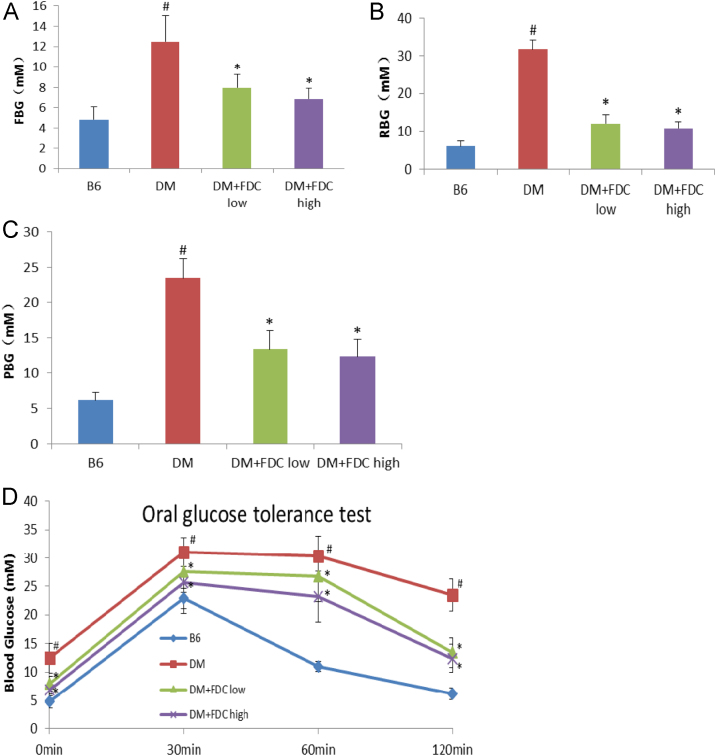

3.7. FDC ameliorated diabetic phenotype and lipid disorders in KK-ay mice

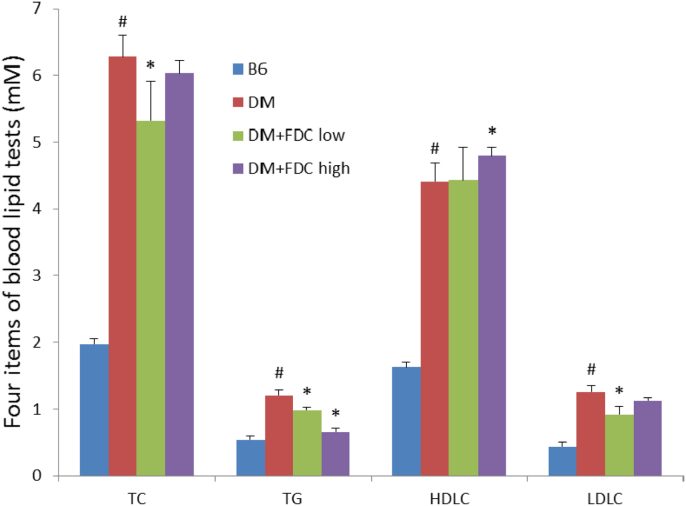

In KK-ay mice diabetes model, the effect of FDC is similar to that in DIO rat model. The one-month FDC feeding decreased fasting blood glucose content (Fig. 9A), random blood glucose content (Fig. 9B) and 2-h postprandial blood glucose content (PBG) (Fig. 9C), but greatly improved glucose tolerance in KK-ay DM mice ( Fig. 9D). FDC also ameliorated lipid disorders in KK-ay mouse model. FDC significantly lowered blood TC, TG and LDL-C, but raised HDL-C in KK-ay mice diabetes model (Fig. 10). Serum TC, TG and HDL-C contents in HFD-fed KK-ay mice were dramatically increased compared to control B6 mice. These results indicated that FDC improved glucose control in KK-ay mice.

Fig. 9.

Effect of FDC on lowering blood glucose content of KK-ay DM mice. (A–C). FDC feeding decreased Fasting Blood Glucose content (FBG) (A), Random Blood Glucose content (RBG) (B) and 2-h Postprandial Blood Glucose content (PBG)(C). (D) FDC feeding greatly improved glucose tolerance of KK-ay DM mice. Values are mean±SD of 6 animals per group for each measurement. * indicates a significant difference between FDC feeding and vehicle feeding groups (P<0.05); # indicates a significant difference between control group B6 mice and KK-ay DM group (P<0.05).

Fig. 10.

Effect of FDC on reducing lipid disorders in KK-ay DM mice. Values are mean±SD of 6 animals per group for each measurement. * indicates a significant difference between FDC feeding and vehicle feeding groups (P<0.05); # indicates a significant difference between control group B6 mice and KK-ay DM groups, or difference between chow diet control and high fat diet feeding groups (P<0.05).

4. Discussion

Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of developing diabetes, physical and functional disabilities and cardiovascular disease [2]. Some patients suffer from a disease associated with low insulin levels and prone to ketoacidosis (type 1DM), while others, the vast majority, have high circulating insulin levels despite increased glucose levels (type 2DM, T2DM) [15,6]. As one of the most common metabolic disorders, diabetes accounts for 6–8% of all health care expenditures [6], and T2DM accounts for around 90% of these cases. Insulin resistance precedes the development of T2DM. Once beta cells can no longer compensate to the insulin resistance, the full-blown disease with hyperglycemia develops [23].

Diabeties usually exhibits high oxidative stress and promotes free radicals generation [17]. ROS secreted by adipocytes leads to insulin resistance in many tissues. Oxidative stress is associated with insulin resistance ([7]) and plays a central role in obesity-caused insulin resistance and T2DM. Especially, oxidative stress in adipocytes decreased insulin-stimulating glucose uptake [13] and might connect obesity with T2DM. Obesity is a major risk factor for T2DM, stroke, hypertension, and some types of cancer (such as colon and breast cancers). Current anti-obesity and anti-diabetes drugs are not highly effective because of considerable side effects such as weight gain, dropsy, hypoglycemia and drug-resistance [3]. However, studies showed that anti-oxidants, such as some polyphenols whose antioxidant properties may depend on structure, cell conditioning with oxidative stress, dose and exposure time, might decrease oxidative stress in adipocytes and improve insulin sensitivity [27]. Polyphenols, flavonoids (such as quercetin and epicatechin), curcuminoids and representatives of main dietary phenolic acids can have protective effect on diabetes [25].

In our previous study, we presented a new mechanism for the anti-insulin resistance effect of green tea, by detecting the enhancement of glucose uptake by GTCs through amelioration of oxidative stress in DIO rats, diabetic KK-ay mice and 3T3-L1 adipocytes [27]. Evidence also showed that although vitamin C alone failed to reduce oxidative stress [14], the combination of vitamin C and vitamin E prevented the teratogenic effects in diabetic rats and autoimmunity of β-cells [18]. Therefore, it is interesting to study the effects of combined antioxidant components in diabetic rats.

However, a quantitative method to evaluate the antioxidant capacity of (the combination of) different compounds is still lacking [10]. Though math models based on numerical and statistical methods [19,20,22] were used to evaluate the antioxidant capacity of some anti-oxidants, many of these current methods have questions that keep open [5]. Moreover, how these in vitro methods are relevant to in vivo cell activities keep uncertain. Hill function used in our model relates the magnitude of an effect to the variable concentration of associating substances with relatively low concentration [8]. Though Hill equation is an empirical model which requires a priori knowledge, it remains an important tool to serve as a theoretical basis for drug discoveries and many pharmacological investigations. Therefore, in this study, we used Hill equation to identify the best combination of the antioxidant components, which can be obtained by the fitted curved surface of parameter a and k, when the free radicals were scavenged by 50%. From this math model, we found that the best ratio for OPC, TP and Vc was obtained as OPC: TP: VC=0.224: 0.704: 0.072. Since this is a ratio close to our empirical values, we changed this value slightly to, based on our priori knowledge, OPC: TP: Vc=3:1:0.1.

It is the first time to use a math model to find the best ratio of three anti-oxidants as FDC about their scavenging effect on free radicals and therapeutic effect on metabolic syndrome in mouse/rat model. It saved much more time and chemical materials than by tranditional experimental method, thus can be extended to define the best ratio of many natural anti-oxidants.

Next, we evaluated the effect of FDC on lipid disorder, obesity, and other characteristics of metabolic syndrome. Lipid disorder is a broad term for abnormalities of cholesterol and triglycerides. Hyperinsulinemia, obesity, and fatty liver are connected to parasympathetic overweight. Four indicators in DIO rats model were tested: LDL-C, HDL-C, TG and TC. High amounts of LDL cholesterol lead to plaque growth and atherosclerosis by tending to deposit in the walls of arteries, further increase the risk of heart disease. Triglyceride, as a blood lipid, is an ester derived from glycerol and three fatty acids. Many triglycerides are the main constituents of vegetable oil, animal fats and human skin oils. High level of TG in the bloodstream has been linked to atherosclerosis and the risk of heart disease and stroke. HDL-C has anti-oxidant property due to its ability to remove oxidized lipids from LDL-C, thus inhibit LDL-C oxidation and protect against atherosclerosis and metabolic syndrome.

Some other indicators were also measured in this investigation. For example, Body weight is somewhat an indicator for metabolic syndrome. If a person's body weight is at least 20% higher than it should be, one is considered fat. Obesity correlates with increased risk for hypertension and stroke. Fat Coefficient is defined as the ratio between the amount of fat in one's body and body weight. The higher the Fat Coefficient is, the more fat one has. Liver Coefficient is defined as the ratio between liver weight and body weight. The higher Liver Coefficient is, the more fat there is in liver cells. The results in this study suggested that FDC showed excellent antioxidant and anti-glycation activity, by attenuating the lipid peroxidation caused by different kinds of free radicals, responsible for its anti-diabetogenic properties. Though FDC can obviously lower the TC level and LDL-C, and raised HDL-C, it did not lower the level of TG significantly. There might be two reasons for this effect: (1) the rat number, in this case, 6, is not high enough for us to observe the real level of TC (for example, the green bar in Fig. 5 has larger variation than expected); (2) the FDC used in this article, indeed, can not lower the level of TG. There might be some other factors which can influence the experimental results, such as concentration of components. Taken together, FDC determined in this investigation can become a potential solution to reduce obesity, improve insulin sensitivity and be beneficial for the treatment of fat and diabetic patients, possibly through strong antioxidant activity and a protective action on β-cells. The potential mechanism by which FDC brings about its hypoglycemic effect may be, at least in part, by increasing the insulin level because of the protective effect of the extracts to pancreatic β-cells and stimulation of insulin secretion from the remaining pancreatic β-cells.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by National Key Basic Research Project (973 program, 2012CB316503) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31361163004 and 91019016).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at 10.1016/j.bios.2014.05.063.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Reference

- 1.Abdel-Wahab Y.H.A., O’Harte F.P.M., Mooney M.H., Barnett C.R., Flatt P.R. Vitamin C supplementation decreases insulin glycation and improves glucose homeostasis in fat hyperglycemic (ob/ob) mice. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2002;51:514–517. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.30528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti K.G.M.M., Eckel R.H., Grundy S.M., Zimmet P.Z., Cleeman J.I., Donato K.A., Fruchart J.-C., James W.P.T., Loria C.M., Smith S.C. Vol. 120. 2009. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity; pp. 1640–1645. (Circulation). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dietrich M.O., Horvath T.L. Limitations in anti-obesity drug development: the critical role of hunger-promoting neurons. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012;11:675–691. doi: 10.1038/nrd3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding Y., Zhang Z., Dai X., Jiang Y., Bao L., Li Y., Li Y. Grape seed proanthocyanidins ameliorate pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and death in low-dose streptozotocin- and high-carbohydrate/high-fat diet-induced diabetic rats partially by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2013;10:51. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frankel E.N., Meyer A.S. The problems of using one-dimensional methods to evaluate multifunctional food and biological anti-oxidants. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000;80:1925–1941. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu W.J., Haynes T.E., Kohli R., Hu J., Shi W., Spencer T.E., Carroll R.J., Meininger C.J., Wu G. Dietary l-arginine supplementation reduces fat mass in zucker diabetic fatty rats. J. Nutr. 2005;135:714–721. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukino Y., Shimbo M., Aoki N., Okubo T., Iso H. Randomized controlled trial for an effect of green tea consumption on insulin resistance and inflammation markers. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2005;51:335–342. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.51.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gesztelyi R., Zsuga J., Kemeny-Beke A., Varga B., Juhasz B., Tosaki A. The Hill equation and the origin of quantitative pharmacology. Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 2012;66:427–438. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo S., Yan J., Yang T., Yang X., Bezard E., Zhao B. Protective effects of green tea polyphenols in the 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson’s disease through inhibition of ROS-NO pathway. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;62:1353–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutteridge J.M.C., Halliwell B. Anti-oxidants: Molecules, medicines, and myths. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;393:561–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatia S., Septembre-Malaterre A., Le Sage F., Badiou-Bénéteau A., Baret P., Payet B., Lefebvre d’hellencourt C., Gonthier M.P. Evaluation of antioxidant properties of major dietary polyphenols and their protective effect on 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and red blood cells exposed to oxidative stress. Free Radic. Res. 2014;48:387–401. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2013.879985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill A.V. The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of hæmoglobin on its dissociation curves. J. Physiol. 1910;40(Suppl):iv–vii. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houstis N., Rosen E.D., Lander E.S. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iino K., Iwase M., Sonoki K., Yoshinari M., Iida M. Combination treatment of vitamin C and desferrioxamine suppresses glomerular superoxide and prostaglandin E2 production in diabetic rats. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2005;7:106–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2005.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inzucchi S.E., Bergenstal R.M., Buse J.B., Diamant M., Ferrannini E., Nauck M., Peters A.L., Tsapas A., Wender R., Matthews D.R. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 dabetes: a patient-centered approach position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jie G., Lin Z., Zhang L., Lv H., He P., Zhao B. Free radical scavenging effect of Pu-erh tea extracts and their protective effect on oxidative damage in human fibroblast cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:8058–8064. doi: 10.1021/jf061663o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamalakkannan N., Prince P.S.M. Antihyperglycaemic and antioxidant effect of rutin, a polyphenolic flavonoid, in streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar Rats. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006;98:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutlu M., Naziroğlu M., Simşek H., Yilmaz T., Sahap Kükner A. Moderate exercise combined with dietary vitamins C and E counteracts oxidative stress in the kidney and lens of streptozotocin-induced diabetic-rat. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2005;75:71–80. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.75.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell S., Mendes P. A Computational Model of Liver Iron Metabolism. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013;9:e1003299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prieto M.A., Zquez J.A. A time-dose model to quantify the antioxidant responses of the oxidative hemolysis inhibition assay (OxHLIA) and its extension to evaluate other hemolytic effectors. BioMed Res. Int. 2014:e632971. doi: 10.1155/2014/632971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy V.P., Zhu X., Perry G., Smith M.A. Oxidative stress in diabetes and Alzheimer's Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:763–774. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shao H., He Y., Li K.C.P., Zhou X. A system mathematical model of cell–cell communication network in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol. Biosyst. 2013;9:398–406. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25370d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabák A.G., Jokela M., Akbaraly T.N., Brunner E.J., Kivimäki M., Witte D.R. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 2009;373:2215–2221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60619-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tracy R.E., Walia P. A method to fix lipids for staining fat embolism in paraffin sections. Histopathology. 2002;41:75–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfram S. Effects of green tea and EGCG on cardiovascular and metabolic health. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007;26:373S–388S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu G., Sztalryd C., Lu X., Tansey J.T., Gan J., Dorward H., Kimmel A.R., Londos C. Post-translational regulation of adipose differentiation-related protein by the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:42841–42847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan J., Zhao Y., Suo S., Liu Y., Zhao B. Green tea catechins ameliorate adipose insulin resistance by improving oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012;52:1648–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L., Yang J., Chen X., Zan K., Wen X., Chen H., Wang Q., Lai M. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effects of extracts from Potentilla discolor Bunge on diabetic rats induced by high fat diet and streptozotocin. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132:518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material