Abstract

Genetic diagnosis of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) using Sanger sequencing is complicated by the high genetic heterogeneity and phenotypic variability of this disease. We aimed to improve the genetic diagnosis of SRNS by simultaneously sequencing 26 glomerular genes using massive parallel sequencing and to study whether mutations in multiple genes increase disease severity. High-throughput mutation analysis was performed in 50 SRNS and/or focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) patients, a validation cohort of 25 patients with known pathogenic mutations, and a discovery cohort of 25 uncharacterized patients with probable genetic etiology. In the validation cohort, we identified the 42 previously known pathogenic mutations across NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, TRPC6, and INF2 genes. In the discovery cohort, disease-causing mutations in SRNS/FSGS genes were found in nine patients. We detected three patients with mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3. Two of them were familial cases and presented a more severe phenotype than family members with mutation in only one gene. In conclusion, our results show that massive parallel sequencing is feasible and robust for genetic diagnosis of SRNS/FSGS. Our results indicate that patients carrying mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and also in COL4A3 gene have increased disease severity.

Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is characterized by heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, edema, and dyslipidemia. Although most patients are steroid-sensitive NS (SSNS), about 20% of children and 40% of adults are steroid-resistant NS (SRNS) and progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD). In these cases, renal histology typically shows focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).1, 2, 3

Inherited structural defects in the glomerular filtration barrier proteins are responsible for a significant proportion of SRNS.4, 5 Patients with SRNS of genetic origin have poor renal survival but low rate of disease recurrence after renal transplantation.6 Genetic forms of SRNS can be inherited as an autosomal recessive (AR) or autosomal dominant (AD) condition and can be isolated or syndromic.5 Mutations in nephrin (NPHS1)7 and podocin (NPHS2),8 with an AR inheritance, are the major cause of congenital and childhood onset NS, respectively. However, mutations in other genes have also been reported.5, 9 Mutations in inverted formin-2 (INF2),10 transient receptor potential channel 6 (TRPC6),11 and rarely, in α-actinin-4 (ACTN4)12 and CD2-associated protein (CD2AP)13 genes cause juvenile or adult onset FSGS with AD inheritance. In rare cases, recessive mutations in NPHS2 are associated with adult onset FSGS.14 De novo heterozygous mutations in exons 8 and 9 of Wilms tumor (WT1) gene can cause both syndromic15 and isolated childhood onset SRNS.16 The study of the relative frequency of mutations in the most commonly altered genes in patients with SRNS and/or FSGS allowed the development of genetic testing algorithms based on age at onset, family history, or renal histology.17, 18, 19, 20 However, the genetic heterogeneity and significant phenotypic variability of SRNS make genetic testing using standard Sanger methods costly and time consuming, even if the analysis is restricted to the most frequently mutated genes.

Massive parallel next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has dramatically increased the throughput and reduced the cost per nucleotide sequenced compared with traditional Sanger methods, enabling cost-effective sequencing of multiple genes simultaneously. Over the past 3 years, whole-exome sequencing has revealed new genes associated with SRNS in a few cases, expanding the genetic heterogeneity of the disease.21, 22, 23, 24, 25 Based on this scenario, targeted NGS of a broad panel of NS-related genes has emerged as a cost-effective strategy to screen the multiple genes involved in SRNS/FSGS,26 but optimal sensitivity and specificity must be demonstrated for each gene in the panel.

In this study, we used targeted NGS to simultaneously sequence 26 genes associated with inherited glomerular diseases in a heterogeneous cohort of 50 SRNS/FSGS patients and 5 control individuals. We aimed to develop a glomerular disease gene panel for SRNS/FSGS and to study the influence of mutations in multiple genes on phenotype variability.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 50 Spanish patients with idiopathic SRNS/FSGS were included. Patients developing steroid resistance at a later stage of the disease or with recurrence after kidney transplantation were excluded as we considered that they likely had an immunological cause. Biopsy findings included FSGS, minimal change disease (MCD) or diffuse mesangial sclerosis. The validation cohort consisted of 25 patients with known pathogenic mutations in the five most commonly mutated SRNS/FSGS genes that had been previously identified by Sanger sequencing.18 The discovery cohort consisted of 25 patients with diagnosis of SRNS/FSGS, 21 genetically uncharacterized, and 4 incompletely characterized. All 25 had a probable genetic etiology, based on early onset of the disease (n=10), familial history of SRNS/FSGS (n=11), or consanguinity (n=4). Four of these patients had been analyzed by Sanger sequencing for the most frequently mutated SRNS/FSGS genes in our previous study, and only one recessive pathogenic mutation was identified.18 We also included five control individuals without nephropathy who had been previously genome-wide genotyped with a HumanOmni 2.5–8 BeadChip (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) to test the performance of the assay across the whole panel. Blood samples were obtained from other family members if they were available. All the samples were codified, and data analysis was performed blindly. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave their signed informed consent.

Sequencing and data analyses

We selected 26 genes associated with hereditary glomerular diseases based on published literature (Table 1). The complete genomic sequence (plus 1 kb of 5′ and 3′ flanking genomic regions) of NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, TRPC6, INF2, LAMB2, COL4A3, COL4A4, COL4A5, and GLA genes and all exons and intron boundaries (plus 100 bp at each end) of the remaining genes were captured using a custom NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Choice Library (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI, USA). After removal of repetitive sequences, 83.6% of the targeted bases were covered with capture baits ranging from 68 to 6689 bp (average 1062 bp), for a final targeted region of 0.9 Mb.

Table 1. Panel of genes involved in inherited glomerular diseases.

| Gene | Disease association | Inheritance | Target | Accession no. | Chromosome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPHS1 | CNS, SRNS | AR | Whole gene | NM_004646.2 | 19 |

| NPHS2 | CNS, SRNS | AR | Whole gene | NM_014625.2 | 1 |

| WT1 | SRNS, Denys–Drash syndrome | AD | Whole gene | NM_000378.4 | 11 |

| INF2 | SRNS, FSGS | AD | Whole gene | NM_001031714.3 | 14 |

| TRPC6 | SRNS, FSGS | AD | Whole gene | NM_004621.5 | 11 |

| LAMB2 | SRNS, Pierson syndrome | AR | Whole gene | NM_002292.3 | 3 |

| COL4A5 | Collagen type IV nephropathy | XL | Whole gene | NM_000495.4 | X |

| COL4A3 | Collagen type IV nephropathy | AD/AR | Whole gene | NM_000091.4 | 2 |

| COL4A4 | Collagen type IV nephropathy | AD/AR | Whole gene | NM_000092.4 | 2 |

| GLA | Fabry disease | XL | Whole gene | NM_000169.2 | X |

| PLCE1 | CNS, SRNS | AR | Exons | NM_016341.3 | 10 |

| ACTN4 | SRNS, FSGS | AD | Exons | NM_004924.4 | 19 |

| CD2AP | SRNS | AD/AR | Exons | NM_012120.2 | 6 |

| MYO1E | SRNS | AR | Exons | NM_004998.3 | 15 |

| ARHGAP24 | NS, FSGS | AD | Exons | NM_001025616.2 | 4 |

| CUBN | NS | AR | Exons | NM_001081.3 | 10 |

| CFH | NS | AR | Exons | NM_000186.3 | 1 |

| COQ2 | NS | AR | Exons | NM_015697.7 | 4 |

| COQ6 | NS | AR | Exons | NM_182476.2 | 14 |

| ITGA3 | NS | AR | Exons | NM_002204.2 | 17 |

| LMX1B | NS, FSGS | AR | Exons | NM_001174146.1 | 9 |

| NEIL1 | NS | AR | Exons | NM_001256552.1 | 15 |

| PDSS2 | NS | AR | Exons | NM_020381.3 | 6 |

| PTPRO | SRNS | AR | Exons | NM_030667.2 | 12 |

| SCARB2 | NS | AR | Exons | NM_005506.3 | 4 |

| SMARCAL1 | NS | AR | Exons | NM_001127207.1 | 2 |

Abbreviations: AD autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; CNS, congenital nephrotic syndrome; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; NS, nephrotic syndrome; SRNS, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome; XL, X-linked.

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using the salting-out method. Libraries were prepared with the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In familial cases, only the proband was analyzed by NGS. Pools of 24 individuals were prepared, hybridized to the custom NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Choice Library (Roche NimbleGen) for 72 h, stringently washed, amplified 17 PCR cycles, and run in a HiSeq2000 instrument (Illumina Inc.).

Data analysis was performed blindly with an in-house developed pipeline previously described.27 All candidate variants were required on both sequenced DNA strands and to account for ≥20% of total reads at that site. Common polymorphisms (≥5% in the general population) were discarded by comparison with dbSNP 138, the 1000G (http://www.1000genomes.org), the Exome Variant Server (http://evs.gs.washington.edu), and an in-house exome variant database to filter out both common benign variants and recurrent artifact variant calls. To identify large structural variants, we used Pindel,28 Conifer,29 and PeSV-Fisher (http://gd.crg.eu/tools).

Evaluation of the pathogenicity of the variants

Nonsense, frameshift, and canonical splice site variants were classified as definitely pathogenic mutations (mutation group (MG)=A). Missense variants were considered a priori unclassified sequence variants (UCV), and their potential pathogenicity was evaluated using an in silico scoring system developed for the PKD1 and PKD2 genes.30 This scoring system with some minor modifications was tested using previously described pathogenic mutations, for which functional studies had been performed, as positive controls, and known neutral variants or polymorphisms as negative controls.31, 32, 33 This scoring system takes into consideration the biophysical and biochemical difference between wild type and mutant amino acid, the evolutionary conservation of the amino-acid residue in orthologs,34 a number of in silico predictors (Sift, Polyphen, Mutation taster, and Condel), and population data. All candidate pathogenic variants not previously identified were validated by conventional PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing and were not detected in 284 control chromosomes. Segregation of these changes with the disease was assessed for all the available family members. We scored each of these factors, and their sum resulted in an overall variant score (VS). The UCV were classified into four MGs: highly likely pathogenic (VS≥11, MG=B), likely pathogenic (5≤VS≤10, MG=C), indeterminate (0≤VS≤4, MG=I), and highly likely neutral (VS≤−1, MG=NV). To evaluate the pathogenicity of non-canonical splice site variants, RNA analysis was performed by RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing. If no RNA was available, these variants were analyzed using Alamut version 2.3 (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France), a software package that uses different splice site prediction programs to compare the normal and variant sequences for differences in potential regulatory signals.35

We designated pathogenic mutations to be: (i) those sequence variants predicted to result in a truncated protein (MG=A), (ii) canonical and non-canonical splice site variants showed to alter splicing patterns (MG=A), and (iii) those amino-acid substitutions expected to severely alter the protein sequence using in silico predictors (MG=B). Missense substitutions classified as MG=C or MG=I were considered as mild mutations in NPHS132 or variants of unknown clinical significance. All the variants were entered in the Leiden Open Variation Database (http://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes).

Results

Validation of the technology

Sequencing of the 26 glomerular disease gene panel (Table 1) in 50 patients with SRNS/FSGS and 5 control individuals generated a mean of 14.3 million reads per patient. On average, 99.1% of these reads mapped to the reference genome. A mean depth of coverage of 466 × was achieved for the 26 targeted genes across all individuals, with 99.6% of targeted bases covered by at least 20 reads (Supplementary Table S1).

The validation cohort included 25 SRNS/FSGS patients who carried a total of 42 known pathogenic mutations in NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, TRPC6, or INF2 genes and with different phenotypic characteristics (Table 2). We identified all known pathogenic mutations (33 different) in their correct heterozygous/homozygous state, specifically: 22 missense, 3 nonsense, 2 splice site, 4 small deletions, 1 small insertion, and 1 deletion/insertion (Indel) (data not shown). No spurious pathogenic mutations were found in any of these samples. Prior Sanger sequencing of these patients had revealed a total of 285 variants in these genes, 281 of which were also detected by NGS, resulting in 98.6% accuracy.

Table 2. Overview of genotypic data obtained by next-generation sequencing.

| Total | Familial | Sporadic | Congenital onset | Early or late childhood onset | Adolescent or adult onset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation cohort | 25 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 9 | 6 |

| Patients with pathogenic mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene | 23 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 8 | 6 |

| Patients with mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Patients with no pathogenic mutations found | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Discovery cohort | 25 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 12 | 8 |

| Patients with pathogenic mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene | 9 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Patients with mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Patients with no pathogenic mutations found | 15 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 5 |

Abbreviations: FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; SRNS, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Onset was classified as follows: congenital, 0–3 months; early childhood, 4 months to 5 years; late childhood, 6–12 years; adolescent, 13–18 years; adult, >18 years.

To assess the sensitivity and specificity of our assay across all 26 genes included in the panel, we evaluated 5 control individuals without nephropathy who had been previously genome-wide genotyped. Sensitivity of detecting homozygous and heterozygous polymorphisms across the 26 genes was 95.6% (1315/1375), and specificity of detecting non-variant sites from the reference genome was 99.9% (3387/3391). No spurious pathogenic mutations were found in any of these samples. Detailed quality control parameters are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Sequence variants in NS genes in the discovery cohort

We identified disease-causing mutations in NS genes in 9 out of the 25 SRNS/FSGS patients in the discovery cohort (Table 3). The distribution of mutations in SRNS/FSGS genes differed depending on the age at onset. The mutation detection rate decreased as the age at onset of NS increased. In congenital onset patients (from 0 to 3 months), all the five patients (100%) carried mutations in NPHS1 (n=3) and NPHS2 (n=2) genes. In the early-childhood onset cohort (from 4 months to 5 years), two out of the nine patients (22%) had mutations in NPHS1 (n=1) and WT1 (n=1). No disease-causing mutations were found in any of the three patients with late-childhood onset NS (from 6 to 12 years). In patients with adult onset of NS or FSGS (>18 years), two out of the eight patients (25%) carried mutations in INF2 (n=1) and TRPC6 (n=1) (Table 2). A detailed scoring matrix for the missense variants is provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 3. Clinical and genetic data of patients in the discovery cohort with disease-causing mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and patients with mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3.

| Patient | Gender | Familial/sporadic | Age at onset (years) | Features at presentation | Renal biopsy | Immunosuppressive therapy | Evolution | Gene | Mutation 1 (MG) | Mutation 2 (MG) | Gene | Mutation (MG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients in the discovery cohort with disease-causing mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene | ||||||||||||

| 319 | M | Sp | 0 | CNS | NP | — | Dead at 1 year | NPHS1 | c.468C>G | c.3478C>T | ||

| p.(Y156*) (A) | p.(R1160*) (A) | |||||||||||

| 336 | M | Sp | 0 | CNS | CNF | — | ESRD at 2 months | NPHS1 | c.1655C>A | c.1655C>A | ||

| p.(A552D) (B) | p.(A552D) (B) | |||||||||||

| 299 | F | Sp | 0.1 | CNS | NP | — | ESRD at 8 months | NPHS1 | c.3250dup | c.3250dup | ||

| p.(V1084Gfs*12) (A) | p.(V1084Gfs*12) (A) | |||||||||||

| 324 | M | Sp | 0.3 | NS without edema | DMS | Cs, CP, CsA, MMF − | Normal Cr at 19 years | NPHS1 | c.1930+5G>A | c.1930+5G>A | ||

| p.(V634Tfs*13) (A) | p.(V634Tfs*13) (A) | |||||||||||

| 363 | F | Sp | 0 | CNS | NP | — | Cr 0.37 mg/dl at 1 month | NPHS2 | c.413G>C | c.413G>A | ||

| p.(R138P) (B) | p.(R138Q) (B) | |||||||||||

| 330 | F | Fama | 0.2 | Nephrotic proteinuria, MAL | DMS | — | Normal Cr at 4 months | NPHS2 | c.320T>C | c.320T>C | ||

| p.(L107P) (B) | p.(L107P) (B) | |||||||||||

| 320 | F | Sp | 3 | Denys–Drash syndrome | FSGS | — | ESRD at 4 years | WT1 | c.1419T>A | — | ||

| p.(H473Q) (B) | ||||||||||||

| 347-1 | M | Famb | 19 | Non-nephrotic proteinuria | FSGS | — | CKD stage II at 20 years | INF2 | c.658G>A | — | ||

| p.(E220K) (B) | ||||||||||||

| 347-2 | F | Famc | 20 | Nephrotic proteinuria | FSGS | Cs, CsA − | ESRD at 29 years | INF2 | c.658G>A | — | ||

| p.(E220K) (B) | ||||||||||||

| 384-1 | F | Famb | 27 | Non-nephrotic proteinuria, MH, MAL | NP | — | Normal Cr at 32 years | TRPC6 | c.2656G>A | — | ||

| p.(E886K) (B) | ||||||||||||

| 384-2 | M | Famd | 30 | MAL | NP | — | Normal Cr at 35 years | TRPC6 | c.2656G>A | — | ||

| p.(E886K) (B) | ||||||||||||

| 384-3 | F | Famc | 55 | Non-nephrotic proteinuria, MH | NP | — | Normal Cr at 63 years | TRPC6 | c.2656G>A | — | ||

| p.(E886K) (B) | ||||||||||||

| Patients with mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3 | ||||||||||||

| 266e | F | Sp | 0 | CNS, MH | NP | — | ESRD at 1 year | NPHS1f | c.514_516del | c.3250dup | COL4A3 | c.3829G>A |

| p.(T172del) | p.(V1084Gfs*12) (A) | p.(G1277S) (B) | ||||||||||

| 10-1e | M | Famb | 4 | NS, MH | FSGS | Cs, CsA − | ESRD at 12 years | NPHS2f | c.274G>T | c.506T>C | COL4A3 | c.4504T>C |

| p.(G92C) (B) | p.(L169P) (B) | p.(F1502L) (C) | ||||||||||

| 10-2 | F | Famg | 2 | NS | MCD | Cs, CsA ± | Normal Cr at 18 years | NPHS2f | c.274G>T | c.506T>C | COL4A3 | — |

| p.(G92C) (B) | p.(L169P) (B) | |||||||||||

| 253-1 | F | Famb | 32 | NS, MH | FSGS* | Cs, CsA − | ESRD at 33 years | INF2 | c.2065C>T | COL4A3 | c.4028-3C>A p.(V1344_G1385del) (A) | |

| p.(R689W) (I) | ||||||||||||

| 253-2 | M | Famh | 39 | Non-nephrotic proteinuria, MH | FSGS | — | ESRD at 51 years | INF2 | — | COL4A3 | c.4028-3C>A p.(V1344_G1385del) (A) | |

| 253-3 | M | Fami | — | — | NP | — | Normal Cr at 61 years | INF2 | — | COL4A3 | c.4028-3C>A p.(V1344_G1385del) (A) | |

| 253-4 | F | Famj | U | MH | NP | — | Normal Cr at 52 years | INF2 | — | COL4A3 | c.4028-3C>A p.(V1344_G1385del) (A) | |

| 253-5 | F | Famc | — | — | NP | — | Normal Cr at 63 years | INF2 | c.2065C>T | COL4A3 | — | |

| p.(R689W) (I) | ||||||||||||

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; CNF, congenital nephrotic syndrome of Finnish type; CNS, congenital nephrotic syndrome; CP, cyclophosphamide; Cr, creatinine; Cs, corticosteroids; CsA, cyclosporin A; DMS, diffuse mesangial sclerosis; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; F, female; Fam, familial case; FSGS, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis; FSGS*, mesangioproliferative lesions with FSGS; M, male; MAL, microalbuminuria; MCD, minimal change disease; MG, mutation group; MH, microhematuria; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; NP, not performed; NS, nephrotic syndrome; Sp, sporadic case; U, unknown.

Therapy effect categories: (−), no response; (±), partial reduction of proteinuria. Mutations on these genes were classified according to Genebank Accession numbers: NG_013356.2, NM_004646.2 and NP_004637.1 (NPHS1); NG_007535.1, NM_014625.2 and NP_055440.1 (NPHS2); NG_009272.1, NM_024426.3 and NP_077744.3 (WT1); NG_027684.1, NM_022489.3 and NP_071934.3 (INF2); NG_011476.1, NM_004621.5 and NP_004612.2 (TRPC6); NG_011591.1, NM_000091.4 and NP_000082.2 (COL4A3). The nomenclature used in this study for the description of sequence variants in DNA and protein is in accordance with the Human Genome Variation Society guidelines and can be found at http://www.hgvs.org/. Mutation groups: A, definitely pathogenic; B, highly likely pathogenic→VS≥11; C, likely pathogenic→5≤VS≤10. Leiden Open Variation Database proband IDs (following the order of the table from top to bottom): 17906, 17907, 19917, 19413, 17908, 17909, 19916, 18450, 18451, 18452, 18453, and 18844.

Only child of consanguineous parents.

Proband.

Proband's mother.

Proband's brother.

Patients of the validation cohort.

Mutations in these genes were previously known in Sanger sequencing.

Proband's sister.

Proband's father.

Proband's uncle.

Proband's aunt.

In the discovery cohort, we included four cases (one familial and three sporadic), with only one recessive pathogenic mutation previously identified by Sanger sequencing. The NGS approach detected variants predicted to alter the non-canonical splice site sequences by the Alamut software but with uncertain clinical significance in three patients.

Phenotypic effect of mutations in multiple glomerular genes

We found four patients belonging to the validation cohort with three mutated alleles in two recessive SRNS/FSGS genes (Supplementary Table S4). Phenotype modification of the third mutated allele could not be assessed in these patients as three of them were sporadic cases, and only two siblings, both carrying the three mutated alleles, were identified.

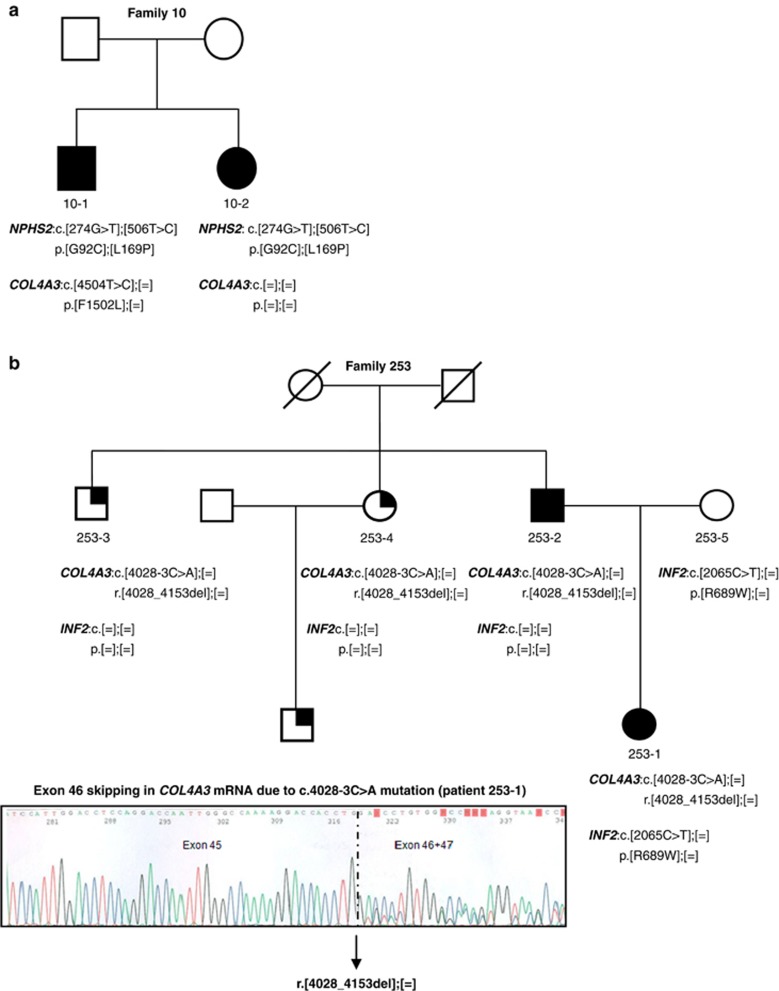

We identified three patients carrying mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and also in COL4A3 (Table 3). Patient 266 carried two NPHS1 pathogenic mutations, an in-frame deletion and a frameshift, together with a heterozygous missense mutation in COL4A3, previously reported by Heidet et al.36 She had a congenital NS presenting with microhematuria and no family history of NS. Patient 10-1 and his affected sister (10-2) both carried compound heterozygous missense pathogenic mutations in NPHS2 gene, but only the proband 10-1 harbored a heterozygous missense variant in COL4A3 predicted to be likely pathogenic. Both siblings had early childhood onset of SRNS. Patient 10-1 presented with nephrotic range proteinuria and microhematuria. His renal biopsy revealed FSGS, and he developed ESRD at 12 years. His sibling 10-2 presented with borderline nephrotic range proteinuria but no evidence of microhematuria, renal biopsy showed MCD and she presented normal renal function by the age of 18 years (Figure 1a). Patient 253-1 carried a heterozygous splicing mutation in COL4A3, demonstrated to produce exon 46 skipping by RNA analysis and predicted to result in a protein lacking 42 amino acids, in combination with a missense variant in the exon 12 of INF2. This novel non-conservative substitution, p.R689W, is located at a highly conservative domain (FH2) in the INF2 protein and scored as highly likely pathogenic, using mutation prediction programs. The arginine in the position 689 is totally conserved in mammals and a basic amino acid in all the species. She presented with SRNS and microhematuria at 32 years, and her renal biopsy showed mesangioproliferative lesions with FSGS. Her renal function rapidly deteriorated, reaching ESRD at 33 years. The COL4A3 mutation was inherited from her affected father (253-2) who presented with non-nephrotic range proteinuria and hematuria at 39 years. His renal biopsy showed FSGS, and he reached ESRD at 51 years. The INF2 variant was inherited from her asymptomatic mother (253-5). Two of the proband's uncles carried the COL4A3 mutation, but they only presented microhematuria at 61 (253-3) and 56 years (253-4) (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of two families with mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3. (a) In family 10, both siblings had compound heterozygous pathogenic mutations in NPHS2 gene and the more severely affected individual (10-1) carried an additional likely pathogenic variant in COL4A3 gene. (b) In family 253, individuals 253-1 to -4 carried a pathogenic mutation in COL4A3 gene demonstrated to produce exon 46 skipping by reverse transcriptase-PCR and Sanger sequencing and predicted to result in a protein lacking 42 amino acids. Patient 253-1 carried an additional variant in INF2 gene inherited from her mother and developed a more aggressive phenotype than the other affected family members. Cr, creatinine; wt, wild type. The arrows indicate probands. Squares denote males, circles denote females. Filled symbols indicate affected status. Quarter solid symbols indicate microhematuria.

Discussion

In this study, we show that the simultaneous analysis of 26 genes causative of inherited glomerular diseases allows a more complete and efficient characterization of patients with SRNS/FSGS than traditional Sanger sequencing. In addition, we identified three patients carrying combined mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3, suggesting that mutations in different genes that converge in the glomerular filtration barrier influence disease severity.

In the past years, several genetic testing algorithms for SRNS/FSGS have been developed to help in establishing a prioritization of the genes to be sequenced by Sanger. However, the genetic heterogeneity and phenotypic variability of this disease make this approach expensive and time consuming.17, 18, 19, 20 Recently, two studies used NGS technology to analyze the exons and intron boundaries of 24 genes26 and 21 genes37 associated with SRNS. Our gene panel included not only genes related with SRNS/FSGS but also genes involved in other glomerular diseases, as we hypothesized that disease severity could be influenced by mutations in multiple glomerular genes. The identification of all previously known pathogenic mutations and no spurious pathogenic mutations in our validation cohort, as well as the high sensitivity and specificity obtained with the analysis of the previously genotyped controls, demonstrate the suitability of this approach for genetic diagnosis of SRNS/FSGS.

In the discovery cohort, we identified disease-causing mutations in NS genes in 9 out of the 25 patients. All patients carried pathogenic mutations in the most likely mutated NS gene according to their age at disease onset.18 Interestingly, patient 324 had a congenital onset of the disease but still normal renal function at the age of 19 years. He carried a homozygous splicing mutation (c.1930+5G>A) in NPHS1 found to produce the deletion of the 31 last nucleotides of exon 14 in the mRNA, which is predicted to result in a truncated protein. The mild phenotype of this patient could be explained, because splicing mutations that do not affect the canonical GT/AG splice sites could allow the coexistence of a certain proportion of wild-type NPHS1 mRNA with the altered mRNA, as previously suggested.38 Although mRNA analysis from patient's blood did not confirm this hypothesis, we cannot discard the occurrence of this phenomenon in kidneys (Supplementary Figure S1).

We also included four patients with only one recessive candidate pathogenic mutation in an SRNS gene identified by Sanger sequencing. We hypothesized that these patients would carry a large insertion or deletion or a deep intronic splicing mutation as a second pathogenic mutation. Thus we included the whole genomic sequence of the most frequently mutated genes in glomerular diseases in our NGS gene panel and analyzed the data using specific algorithms to search for structural variants. No clear pathogenic mutation was detected, but only variants in non-canonical splice sites were found in three patients. However, RNA from these patients was not available, and the pathogenicity of these variants could not be assessed.

The phenotypic variability observed in SRNS/FSGS patients bearing mutations in the same gene suggests that modifier genes and environmental factors may have a significant role in the renal presentation and outcome.4 Evidence of oligogenic inheritance with mutations in genes encoding proteins that converge in common pathomechanistic pathways has been reported in Bardet–Biedl syndrome.39 In addition, the p.R229Q variant in NPHS2 gene has been suggested to contribute to proteinuria and ESRD in thin basement membrane nephropathy.40, 41 Recently, modifier genes have been proposed to explain early and severe polycystic kidney disease.42 McCarthy et al26 described two patients carrying a homozygous mutation in NPHS1 and a possibly pathogenic variant in WT1, who developed a more aggressive disease than a third patient carrying the same mutation in NPHS1 but without the WT1 variant. To study the putative role of mutations in multiple glomerular genes on SRNS/FSGS clinical variability, disease severity should ideally be compared among various family members with different genotype combinations. Here, four patients carrying three mutated alleles in two SRNS/FSGS genes were found. Unfortunately, three of them were sporadic cases, and only two affected siblings—both carrying the three mutated alleles—were identified. Therefore, the putative effect of the third variant on disease severity could not be assessed.

We identified three patients carrying mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene in combination with a heterozygous mutation in COL4A3 gene. Heterozygous mutations in COL4A3 and COL4A4 genes cause the mildest phenotype of collagen type IV (α3α4) nephropathy, also named thin basement membrane nephropathy. This nephropathy is characterized by hematuria and low proteinuria,43, 44 and progression to ESRD has recently been described in 30% of cases.45 The clinical phenotype of the three patients with combined mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3 stands out for the coexistence of NS and microhematuria at presentation. Interestingly, in two of these three cases, several family members with different genotype combinations were available (Figure 1). In both families, patients with mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and COL4A3 had a more severe phenotype than their family members carrying mutations in only one gene. Variable disease penetrance in INF2-mutated patients has been reported46 likely explaining that, in family 253, the proband's mother (253-5) remained asymptomatic. These findings suggest that mutations in multiple glomerular disease genes explain some of the phenotypic variability in nephropathies. Another possible explanation for clinical intrafamilial variability could arise in families carrying a splicing mutation that does not affect the canonical splice sites, such as the mutation in COL4A3 gene detected in family 253. This mutation could lead to variable amounts of the correctly spliced transcript and could explain the phenotypic variability among the three siblings carrying this splicing mutation.38

Despite the broad panel of genes analyzed, we could not find pathogenic mutations in 15 of the patients in the discovery cohort, 8 of whom were familial cases. The fact that some SRNS/FSGS patients present with recurrence after kidney transplantation indicates that some of these cases may be due to an immunological cause, although no evidence of immunological bases was observed in our cohort. In the familial cases, it is highly likely that an SRNS/FSGS gene, as yet non-identified, is responsible for the disease. The next step should therefore be to sequence the whole exome in the 8 familial cases to identify new candidate genes.

The results obtained in the validation cohort demonstrate that our approach is suitable for genetic diagnosis of SRNS/FSGS but, based on the discovery cohort findings, we propose some modifications: (1) to sequence a gene panel with only the six most frequently mutated genes in SRNS/FSGS (NPHS1, NPHS2, PLCE1, WT1, INF2, TRPC6). The COL4A3, COL4A4 and COL4A5 genes, associated with collagen type IV (α3α4) nephropathy, could also be included as they may influence disease severity. If no pathogenic mutations are identified, a more extensive glomerular gene panel or exome sequencing could be performed; and (2) to restrict the targeted sequence to exons and intron boundaries as the assessment of the pathogenicity of deep intronic variants is challenging and their involvement in the disease speculative. In terms of the cost, NGS will allow the simultaneous analysis of around 250 exons for approximately the same cost of consumables than sequencing 40 exons by Sanger, with three times saving in hands-on time. Identifying pathogenic mutations in SRNS is important for many reasons. It can help to avoid the adverse effects of steroid therapy, modify the intensity and duration of immunosuppressive therapies, encourage living donor kidney transplantation, provide prognostic information regarding the gene and type of mutations, and enable genetic counseling. Sequencing a panel of genes involved in glomerular inherited diseases will also help to elucidate cases with atypical renal phenotypes and/or with high clinical intrafamilial variability. Based on our findings, such cases could be more prevalent than previously expected.

In conclusion, this study shows the feasibility and robustness of targeted NGS for genetic diagnosis of SRNS/FSGS, allowing a more complete characterization of patients with SRNS/FSGS. Our results indicate that patients carrying mutations in an SRNS/FSGS gene and also in COL4A3 gene have increased disease severity.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for taking part in this study and the referring physicians who participated in this study, especially Dr Camino (Hospital San Agustín, Avilés). We thank Justo Gonzalez, Patricia Ruiz and Estefania Eugui for technical support; Cristian Tornador and Georgia Escaramis for bioinformatics assistance; Carolyn Newey for English language editing; and IIB Sant Pau-Fundació Puigvert Biobank for kindly providing some of the NS samples, ReTBioH (Spanish Biobank Network) RD09/76/00064. This project was funded by the Spanish Plan Nacional SAF2008-00357 (NOVADIS); the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FIS/FEDER PI11/00733); the European Commission 7th Framework Program, Project N. 261123 (GEUVADIS) and Project N. 262055 (ESGI); the Spanish Healthy Ministry (FIS 12/01523 and FIS PI13/01731), ISCIII-RETIC REDinREN/RD06/0016 and RD012/0021 FEDER funds; the Catalan Government (AGAUR 2009/SGR-1116); and the Fundación Renal Iñigo Álvarez de Toledo (FRIAT) in Spain. Dr Roser Torra is supported by the Intensification Program of Research Activity ISCIII/Generalitat de Catalunya (program I3SN).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Short versus standard prednisone therapy for initial treatment of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children. Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Padiatrische. Lancet 1988; 1: 380–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troyanov S, Wall CA, Miller JA, Scholey JW, Cattran DC: Focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis: definition and relevance of a partial remission. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 1061–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antignac C: Genetic models: clues for understanding the pathogenesis of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest 2002; 109: 447–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit G, Machuca E, Heidet L, Antignac C: Hereditary kidney diseases: highlighting the importance of classical Mendelian phenotypes. Ann NY Acad Sci 2010; 1214: 83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbadegesin RA, Winn MP, Smoyer WE: Genetic testing in nephrotic syndrome—challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Nephrol 2013; 9: 179–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlon PJ, Lynn K, Winn MP et al: Spectrum of disease in familial focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 1999; 56: 1863–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestilä M, Lenkkeri U, Männikkö M et al: Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein—nephrin—is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Mol Cell 1998; 1: 575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boute N, Gribouval O, Roselli S et al: NPHS2, encoding the glomerular protein podocin, is mutated in autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Nat Genet 2000; 24: 349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkes BG, Mucha B, Vlangos CN et al: Nephrotic syndrome in the first year of life: two thirds of cases are caused by mutations in 4 genes (NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, and LAMB2). Pediatrics 2007; 119: e907–e919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Schlöndorff JS, Becker DJ et al: Mutations in the formin gene INF2 cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL et al: A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science 2005; 308: 1801–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN et al: Mutations in ACTN4, encoding alpha-actinin-4, cause familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet 2000; 24: 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Wu H, Green G et al: CD2-associated protein haploinsufficiency is linked to glomerular disease susceptibility. Science 2003; 300: 1298–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machuca E, Hummel A, Nevo F et al: Clinical and epidemiological assessment of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome associated with the NPHS2 R229Q variant. Kidney Int 2009; 75: 727–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier J, Bruening W, Li FP, Haber DA, Glaser T, Housman DE: WT1 mutations contribute to abnormal genital system development and hereditary Wilms' tumour. Nature 1991; 353: 431–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanpierre C, Denamur E, Henry I et al: Identification of constitutional WT1 mutations, in patients with isolated diffuse mesangial sclerosis, and analysis of genotype/phenotype correlations by use of a computerized mutation database. Am J Hum Genet 1998; 62: 824–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit G, Machuca E, Antignac C: Hereditary nephrotic syndrome: a systematic approach for genetic testing and a review of associated podocyte gene mutations. Pediatr Nephrol 2010; 25: 1621–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santín S, Bullich G, Tazón-Vega B et al: Clinical utility of genetic testing in children and adults with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 1139–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rood IM, Deegens JK, Wetzels JF: Genetic causes of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: implications for clinical practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipska BS, Iatropoulos P, Maranta R et al: Genetic screening in adolescents with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int 2013; 84: 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele C, Iatropoulos P, Donadelli R et al: MYO1E mutations and childhood familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna-Cherchi S, Burgess KE, Nees SN et al: Exome sequencing identified MYO1E and NEIL1 as candidate genes for human autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int 2011; 80: 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovunc B, Otto EA, Vega-Warner V et al: Exome sequencing reveals cubilin mutation as a single-gene cause of proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22: 1815–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta IR, Baldwin C, Auguste D et al: ARHGDIA: a novel gene implicated in nephrotic syndrome. J Med Genet 2013; 50: 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer O, Woerner S, Yang F et al: LMX1B mutations cause hereditary FSGS without extrarenal involvement. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 1216–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy HJ, Bierzynska A, Wherlock M et al: Simultaneous sequencing of 24 genes associated with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 8: 637–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillano D, Ramos MD, Gonzalez J et al: Next generation diagnostics of cystic fibrosis and CFTR-related disorders by targeted multiplex high-coverage resequencing of CFTR. J Med Genet 2013; 50: 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z: Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 2865–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm N, Sudmant PH, Ko A et al: Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res 2012; 22: 1525–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti S, Consugar MB, Chapman AB et al: Comprehensive molecular diagnostics in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18: 2143–2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santin S, Ars E, Rossetti S et al: TRPC6 mutational analysis in a large cohort of patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2009; 24: 3089–3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santín S, García-Maset R, Ruíz P et al: Nephrin mutations cause childhood- and adult-onset focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 2009; 76: 1268–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santín S, Tazón-Vega B, Silva I et al: Clinical value of NPHS2 analysis in early- and adult-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 344–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavtigian SV, Deffenbaugh AM, Yin L et al: Comprehensive statistical study of 452 BRCA1 missense substitutions with classification of eight recurrent substitutions as neutral. J Med Genet 2006; 43: 295–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdayer C: In silico prediction of splice-affecting nucleotide variants. Methods Mol Biol 2011; 760: 269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidet L, Arrondel C, Forestier L et al: Structure of the human type IV collagen gene COL4A3 and mutations in autosomal Alport syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovric S, Fang H, Vega-Warner V et al: Rapid detection of monogenic causes of childhood-onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 9: 1109–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ars E, Tazon-Vega B, Ruiz P et al: Male-to-male transmission of X-linked Alport syndrome in a boy with a 47,XXY karyotype. Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsanis N, Ansley SJ, Badano JL et al: Triallelic inheritance in Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a Mendelian recessive disorder. Science 2001; 293: 2256–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonna S, Wang YY, Wilson D et al: The R229Q mutation in NPHS2 may predispose to proteinuria in thin-basement-membrane nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol 2008; 23: 2201–2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskarides K, Arsali M, Athanasiou Y, Elia A, Pierides A, Deltas C: Evidence that NPHS2-R229Q predisposes to proteinuria and renal failure in familial hematuria. Pediatr Nephrol 2012; 4: 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann C, von Bothmer J, Ortiz Bruchle N et al: Mutations in multiple PKD genes may explain early and severe polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22: 2047–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY: Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int 2003; 64: 1169–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torra R, Tazon-Vega B, Ars E, Ballarin J: Collagen type IV (alpha3-alpha4) nephropathy: from isolated haematuria to renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19: 2429–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallerini C, Dosa L, Tita R et al: Unbiased next generation sequencing analysis confirms the existence of autosomal dominant Alport syndrome in a relevant fraction of cases. Clin Genet 2014; 86: 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barua M, Brown EJ, Charoonratana VT, Genovese G, Sun H, Pollak MR: Mutations in the INF2 gene account for a significant proportion of familial but not sporadic focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int 2013; 83: 316–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.