Abstract

Introduction

We prospectively tested whether environmental cues prompts attempts to stop smoking.

Methods

We recruited 134 smokers who intended to quit in the next 3 months to complete nightly calls to report cues as well as smoking status, intentions to smoke or not on the next day, and quit attempts over 12 weeks. We provided no treatment.

Results

Participants averaged 6.5 cues/week. The most common cues were embarrassment, cost of cigarettes and messages in the media. The number of cues over a 7-day period predicted the incidence of a quit attempt on the eighth day (e.g. from 1.5% when no cues occurred to 3% when 7 cues occurred during the 7 days). This effect was dose-dependent and was due to both between and within-subject predictors. Five cues predicted quit attempts. A cue that made smokers concerned about the cost of cigarettes appeared to be the strongest cue. Cues on the day prior were not more powerful predictors than more distal cues. Intention to not smoke the next day on the evening prior to the eighth day was a partial mediator of the effect of cues on quit attempts. Retrospective recall of cues was poor.

Conclusions

Our results suggest the occurrence of cues may be a cause of quit attempts and that programs to increase the frequency of cues may increase quit attempts. Further research should examine whether environmental cues and introspective states (e.g. self-efficacy) interact to prompt quit attempts.

Keywords: tobacco, nicotine, natural history, smoking cessation, quit attempts

1. INTRODUCTION

To stop smoking requires two processes: making a quit attempt and then remaining abstinent (Zhu et al., 2012). Several tobacco control interventions (e.g., increased taxes, worksite restrictions and counter-marketing; Warner & Tam, 2012) and several clinical interventions (e.g., physician advice, stage of change interventions, and motivational interviewing; Zhu et al., 2012) prompt quit attempts. However, despite the implementation of many of these interventions only 53% of US smokers try to quit in a calendar year (Jamal et al., 2014). Thus, new strategies to prompt quit attempts are needed. To develop these, we need a better understanding of what triggers quit attempts (Zhu et al., 2012). For example, if being embarrassed by smoking is a strong predictor of a quit attempt but hearing that a friend is suffering from a smoking-related illness is not, then media messages should focus on the former rather than the latter.

Although many studies have examined factors that influence remaining abstinent after a quit attempt (Piasecki, 2006), few have explored the processes that influence making a quit attempt (Zhu et al., 2012). Most of the empirical descriptions of what leads to quit attempts are based on retrospective studies that ask about reasons for wanting to quit and suffer from the well-documented attribution, recall and forgetting biases common in retrospective studies (Shiffman, 2009). The few prospective studies have focused on predictors that are not modifiable (e.g., demographics), and gather data only at 3-12 month intervals. Prior studies have focused mostly on introspective states such as intention to quit, self-efficacy, and motivation (Piasecki, 2006). These studies often imply a slow, gradual increase in cognitive factors leads to a clear decision to quit, followed by preparatory actions, and the setting of a future quit date (Noar and Zimmerman, 2005). However, more recent studies suggest many quit attempts are sudden, spontaneous, and largely devoid of anticipatory planning (Larabie, 2005; West and Sohal, 2006) . These descriptions often imply that some proximal event may trigger a quit attempt (Larabie, 2005).

The purpose of the current study was to provide a prospective, near real-time, description of the processes leading up to a quit attempt. Our prior published analyses of a pilot study (Hughes et al., 2014) and of the current data set (Hughes et al., 2014) reported on the role of intentions and setting a quit date as predictors of quit attempts and abstinence, and thus, these outcomes will not be repeated in this paper. Instead, the current analysis focuses on whether external cues related to stopping smoking prompt a quit attempt.

2. METHODS

2.1 Overview of Study Design

We recruited adult daily smokers who were interested in quitting at some point in the next 3 months into a prospective, observational, cohort study. Participants called an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system (Corkrey and Parkinson, 2002) nightly for 12 weeks and completed longer questionnaires at baseline, and then every 4 weeks for a second 12 weeks. The nightly IVR recorded tobacco use, intentions to quit, and external cues. No intervention occurred. Our major hypotheses for the current analysis were that the number of cues and the type of cue would prospectively predict the occurrence of a quit attempt. The University of Vermont Committees on the Use of Human Participants approved the study and we registered the study at www.clinicaltrials.com (NCT00995644).

2.2 Development of List of Cues Related to Stopping Smoking

We initially reviewed the published literature and developed a list of possible cues related to quit attempts. We also recruited 27 current daily smokers or ex-smokers who had made an attempt to stop smoking in the last month. Two of us (JRH and LS) conducted semi-structured interviews that asked the participant to describe cues that prompted the most recent quit attempt. From these two procedures, we developed a list of several cue categories along with operational definitions and exemplars. To further confirm our categories, we sent a list of cues to eight smoking experts and asked them to identify the most important ones and sort them into categories. The experts suggested minor changes that were incorporated into a list of 13 cue titles and descriptions. Next we recruited 40 participants into a one-month pilot test of the protocol, and its quitting outcomes are described elsewhere (Hughes JR et al., 2014). In this pilot we included a “don't know/unclear” option for cue questions to assess question clarity. We also conducted a qualitative interview at the end of the first 2 weeks of their participation to determine feasibility of the IVR, ask about difficulties with assigning cues to categories and suggestions for wording of the cues. Minor methodological changes to cue descriptions were made based on this pilot study. In addition, we found some cues were highly correlated because they referred to similar events; thus, we reduced the 13 cues into 9 categories: “something happened to make you embarrassed about your smoking, media mentioned harm from or treatment for smoking, someone asked you to quit or mentioned harm from smoking, cue that made you concerned about the cost of cigarettes, new or worsening symptom, smoker you know quit smoking, smoker you know has a new tobacco-related symptom, MD asked you to quit or mentioned harm from smoking, and non-smoker has a symptom related to your smoking (Table 1).”

Table 1.

Median number of days per week that a cue occurred and percent of participants who had weekly cues

| Total number of occurrences of cue in the study | Percent of participants in which cue occurred weekly | Median times (25th, 75th percentiles) cue occurred during a week | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embarrassed about your smoking | 2,758 | 49 | 0.9 (0.2,3.6) |

| Cue that made you concerned about the cost of cigarettes | 2,413 | 46 | 0.6 (0.1,2.3) |

| Media mentioned harm from or treatment for smoking | 1,674 | 41 | 0.8 (0.3,1.9) |

| Someone asked you to quit or mentioned harm from smoking | 1,661 | 39 | 0.7 (0.3,1.8) |

| New or worsening symptom | 816 | 19 | 0.2 (0.1, 0.8) |

| Smoker you know quit smoking | 518 | 10 | 0.2 (0,0.5) |

| Smoker you know has tobacco related symptom | 228 | 4 | 0.1 (0, 0.2) |

| MD asked you to quit or mentioned harm from smoking | 197 | 0 | 0.1 (0), 0.2) |

| Nonsmoker had symptom due to your smoking | 160 | 1 | 0.0 (0, 0.2) |

2.3 Recruitment

In 2010-11, we recruited participants using internet advertisements that appeared when smokers entered phrases such as “quit smoking” into search engines. We also posted our study on research study websites (e.g., www.clinicaltrials.gov) and Craig's List (www.craigslist.org). A typical message was “Daily smokers who want to quit wanted for University of Vermont research study. No need to leave home. This study does not offer treatment.” There was no mention of reimbursement in the ads.

Major inclusion criteria were a) ≥ 18 years old, b) smoke cigarettes daily for at least 1 year, c) smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day, d) have not used oral tobacco, pipes or cigars in the last 2 weeks, e) probably or definitely intend to quit in the next 3 months, f) own a touch-tone phone, g) does not work a night shift and typically goes to bed between 2100-0200, and h) is fluent in English. We required high intentions to quit to increase the probability that most participants would make a quit attempt within the next 3 months. Our sample of smokers intending to quit in the next 3 months probably represents about half of US smokers (Tobacco Use in Canada: 2014, www.tobaccoreport.ca). We screened 1013 participants and excluded 809. The major reason for initial exclusion was low intention to quit in the next 3 months. Among the 204 eligible, 193 consented and began the study. We a priori decided to exclude participants who did not complete ≥ 5 IVR calls in the first week) because our prior experience is that such participants are likely to have significant amounts of missing data during the study. This excluded 41 participants, leaving 152 enrolled participants. We asked about cues for quit attempts only on days of smoking. To obtain a sufficient sample of cues, we only included participants who had a minimum of 7 consecutive days of smoking (i.e., excluded those who became abstinent early on). This decreased the sample to 134 participants who contributed a total of 10,062 days of IVR data. Among the 134 who entered the study, few (6%) dropped out during the study. Few (5%) calls were missed; half (51%) of the participants did not miss any calls.

These 134 participants averaged 45 years old (standard deviation = 13), and 68% were women, 94% high school graduates, and 77% non-Hispanic Whites. They smoked an average of 19 cigarettes/day (sd = 10) and had an average Fagerstrom Test for Tobacco Dependence score of 5.4 (2.2). Our sample was generally similar to the average US smoker trying to quit but had more women, were more educated and were heavier smokers; it included less heavy, less dependent smokers than treatment seeking smokers (Hughes JR et al., 2014).

2.4 Interactive Voice Recording (IVR)

The IVR is a system in which participants call a number which directs them to enter data using the phone keypad (Corkrey and Parkinson, 2002). IVR has many of the assets of computer-assisted telephone interviewing; e.g., automatic skips, branching options, prohibition of illogical responses and outliers, standardized questioning, and direct data entry. IVR's major assets are the increased confidentiality and the ability to prompt participants to call (Corkrey and Parkinson, 2002). Drug use outcomes are more accurately reported in IVR studies compared to in-person phone interviews, computer assessments, written questionnaires, or in-person interviews (Corkrey and Parkinson, 2002). IVR appears to produce little reactivity and less volunteer bias. (Corkrey and Parkinson, 2002). The IVR asked smoking status, intention to smoke the next day, and cigarettes/day nightly for 12 weeks (i.e. 84 days). If the participant smoked that day, the IVR also asked whether the different cues occurred that day. To detect quit attempts that lasted less than an entire day, each week the IVR asked the number of such brief quit attempts that occurred in the prior week and when the most recent attempt occurred.

2.5 Post Quit Attempt Interview

To compare retrospective recall of cues with cues reported on the IVR, we conducted a phone interview among the first 42 smokers who made a quit attempt, within a week after their quit attempt, and asked them whether any of the cues occurred in the last week.

2.6 Data Analysis

Like most natural history studies, we had little information to use to estimate a sufficient sample size. We chose a sample size of 200 because, with dichotomous outcome, it will produce a 95% CI of no wider than ± 7%. For descriptive statistics (e.g. the incidence of quit attempts or cues), to ensure each participant contributed equally to the outcomes, we first averaged results within each participant and then averaged across participants. Most of the results had skewed outcomes; thus, we often report medians and interquartile range (i.e. 25th and 75th percentiles).

Our major dependent variable was the incidence of a quit attempt. Our major independent variable was the number of cessation-related cues over the 7-day period prior to the day of interest. We chose 7 days because it would allow us to examine not only the total number of cues but also the dose-dependency of number of cues and whether more proximal cues were more robust predictors of quit attempts. We allowed overlap in time periods when testing the effect of cues. For example, we tested whether cues occurring on a Sunday through Saturday predicted quitting on Sunday, and examined whether cues occurring on Monday through Sunday of that same week predicted quitting on Monday. These criteria produced a total of 5081 pochs to test. We used multilevel logistic regression with a random-intercept(Hox, 2002) to predict quit attempts via the Proc GLIMMIX, SAS v9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC statistical software. This approach is appropriate when there are a large number of repeated measures and when there are varying numbers of records per participant.

Secondary analyses examined a) the different types of cues (e.g., concern about cost of cigarettes vs. advice from a health care provider) as predictors, and b) the incidence of attempts lasting ≥ 1 day as an outcome. Because of reports that many quit attempts are impulsive, we also examined whether the number of cues on a prior day predicted quitting on the next day, plus we examined whether baseline characteristics were moderators of any cue effects. A final secondary analysis examined whether intention to quit on the evening prior to the eighth day was a mediator via a multilevel mediation analysis (Hayes 2009; Preacher and Hayes 2004). Because the distribution of the indirect (i.e., mediation) effect would probably not be normally distributed, a bootstrap approach was used. For each sample, three separate multilevel logistic regression models were run: (a) a model estimating the direct effect, namely cues predicting quit attempt; (b) the mediator added to the model as a second predictor; and (c) number of cues predicting the mediator. The mediation effect was calculated for each sample as the product of the relevant coefficients from the second and third models.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Incidence of Quit Attempts

Most participants (81%) reported at least one quit attempt of any length (i.e. including those lasting less than a day), and the total number of attempts of any length was 357 with a median of 2 (25th and 75th percentiles = 1, 4) quit attempts. About a third (37%) reported a quit attempt that lasted ≥ 1 day, and the total number of these attempts was 68. In comparison, the 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) found that about half (53%) of unselected US smokers made a quit attempt that lasted ≥ 1 day in the last year and that, among those that made an attempt, the median number of quit attempts in that year was two. (Jamal et al., 2014) Thus, the expected incidence of a quit attempt in a randomly selected smoker over our study period would be 0.53 × 2 × 12 weeks/52 weeks = 24%. Our higher rate (37% vs 24%) is probably because we required a high intention to quit in the next 3 months, plus prior studies (Borland, Partos, Yong, Cummings, & Hyland, 2012; Berg et al., 2010) and our results (see below) suggest 20%-90% of quit attempts are forgotten.

3.2 Incidence of Cues

Almost all participants (90%) reported at least one cue each week. The median number of days during a week that a cue occurred was 3.9 (2.0, 5.7), and the median number of cues/week was 6.5 (2.9, 10.6). The most prevalent cues were embarrassment, exposure to media messages about smoking or smoking treatment, someone other than a health care provider commented on smoking, and something made the participant more concerned about the cost of cigarettes (Table 1). Smokers who endorsed more anti-smoking norms or had a greater external locus of control were more likely to report a cue (F = 9.9 and 7.8, p ≤ .005). Those with more education, anti-smoking norms, or external locus of control were more likely to report embarrassment as a cue (F=7.2, 11.7 and 8.4, p ≤ .007). Smokers without home rules about smoking or higher FTND scores were more likely to report a smoking-related health symptom cue (F= 5.6 and 7.0, P ≤ .008). Those with a higher FTND scores were more likely to report an MD talked to them about smoking (F = 9.4, p = .002.). Age, cigarettes/day, employment, gender, perceived benefits of and barriers to quitting smoking, plans for quitting, race, self-rated addiction, time-to-first cigarette, self-efficacy did not predict cue occurrence. None of the tested moderators influenced the relationship between cues and quit attempts.

When we compared the retrospective report of cues in the prior week among the 42 participants in the qualitative phone study with the reports of the IVR for that same week, across the nine cue categories, the Kappa values were small and ranged from 0.25 to 0.53. The majority of disagreements were participants failing to retrospectively report a cue when they had reported it on the IVR.

3.3 Cues as Predictors of Quitting

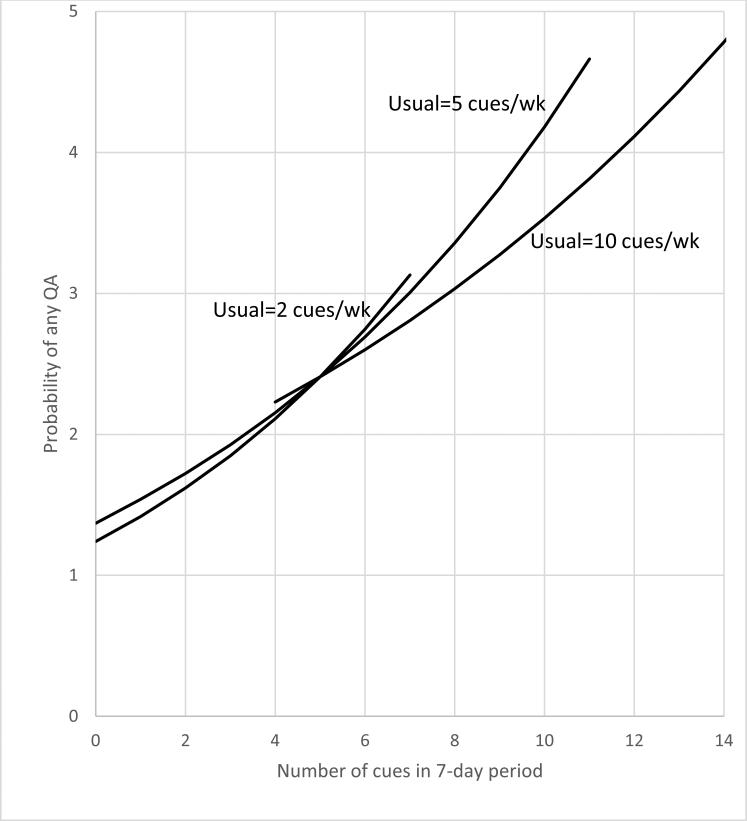

In the analysis that included both within- and between-participant effects, the number of cessation-related cues over a 7-day period prospectively predicted the occurrence of a quit attempt on the eighth day in a dose-responsive manner; however, an interaction of between and within participant variation occurred; i.e., the dose-response effect of the number of cues was greater among participants who typically had a lower number of cues (Finteraction = 4.1, p = .04). Figure 1 illustrates this effect. In terms of the magnitude of the effect, the resultant model projects that the probability of a quit attempt on the eighth day when a participant had no cues in the prior 7 days was about 1.5% and doubled to 3% if the participant experienced 7 cues in the prior week. A similar but not significant trend occurred when only attempts lasting 1+ days was the outcome.

Figure 1.

Probability of a quit attempt on a given day as a function of number of cues in the preceding 7 days for participants with low, medium or high distribution of usual number of cues/week (subject-level medians of 2, 5, and 10 cues/week = 25th, 50th, 75th percentiles). The regression lines are plotted for the range of values represented by 95% of the observed data.

In the analysis examining only within-participant effects, when participants had a greater number of cues on the week prior to the eighth day they were more likely to make a quit attempt of any length and an attempt lasting 1+ days (Table 2). A similar effect occurred when we examined only cues that occurred the day before the eighth day (p = .02). We also found cues on the day of the quit attempt were associated with a quit attempt; (p = .004); however, we do not know whether cues on day of the attempt preceded or post-ceded the actual attempt and, thus, do not know if this relationship represents prospective prediction. Unexpectedly, the effect of cues was not more powerful on the days more proximal to the eighth day; e.g. the Beta values for prediction of a quit attempt on the 1st-7th day prior were 0.19, 0.19, 0.24, 0.15, 0.25, 0.29, and 0.19. In terms of specific cues, five cues predict quitting in one or more analyses; however, cost was the only cue that predicted increased quitting across both time frames and outcomes (Table 2). We tested whether the number of different types of cues would predict quit attempts, independent of the number of cues, and found it did not, but this may be because the two were highly correlated (r=.89). Among those who made a quit attempt, the number of cues did not predict the duration of abstinence.

Table 2.

F-values for the Association of Number of Cues and of Specific Cues on Quit Attempts (QA)a

| 7 Days Prior to Eighth Day | 1 Day Prior to Eighth Day | Incidence of Attributing Quit Attempt to Factors In Prior Study (Ussher, 2013) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quit Attempt | 1+ Day of Abstinence | Quit Attempts | 1+ Day of Abstinence | ||

| Number of cues | 13.3** | 5.7* | 5.2* | 5.0* | Not Asked |

| Nonsmoker had symptom due to your smoking | 0.8 | NC | 0.1 | NC | Not Asked |

| Cue that made you concerned about the cost of cigarettes | 7.2* | 4.6* | 10.8* | 7.8* | 19% |

| Embarrassed by your smoking | 0.8 | NC | 0.2 | 0 | Not Asked |

| HCP asked or mentioned harm from smoking | 4.1* | 0.7 | 0.5 | 5.8* | 25% |

| Media mentioned harm from or treatment for smoking | 9.0* | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.01 | 7% |

| New or worsening symptom | 0 | NC | 0.2 | 0.1 | 21% |

| Smoker you know has tobacco related symptom | 2.2 | NC | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1% |

| Smoker you know quit smoking | 1.1 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 8.0* | 8% |

| Someone asked you to quit or mentioned harm from smoking | 10.9* | NC | 3.8 | 2.6 | 14% |

df of F statistic = 1, 4948

p < .05

p< .001,

Similar, but not exact, cues. When more than one factor applicable, used factor with highest rating

HCP = health care provider, NC = Model did not converge and thus the effect could not be tested

The mediation analysis found that the number of cues occurring in the past 7 days predicted reporting a new intent to quit on the evening of the last day of the period (t = 2.4, p = .02), which in turn predicted making a quit attempt on the next (eighth) day (t = 8.1, p < .0001). The mediation pathway was significant (p < .05 based on 95% bootstrap confidence interval), although the direct path between cues and quit attempts also remained significant (p = .0004). About half (56%) of the effect of cues on quit attempts was mediated by intention; thus, cues predicted attempts both on days with no prior intention to quit and on days with a prior intention to quit. The results were similar when attempts that lasted ≥1 day was the outcome.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 Summary of Results

Our major findings are a) participants averaged 6.5 cues to quit each week, b) the most common cues were embarrassment and tobacco-related media, c) the number of cues to stop smoking over a 7-day period prospectively predicted the probability of a quit attempt on the eighth day in a within-participant, dose-response manner, d) among the nine cue types, the only specific cue that reliably predicted quit attempts was a cue reminding smokers of the cost of cigarettes, e) within the 7-day periods, more proximal cues were not more predictive than more distal cues, f) cues predicted both planned and unplanned quit attempts, g) intention to not smoke the next day was a mediator of cue effects, and h) retrospective recall of cues in the last week was poor.

4.2 Interpretation of Results

Most attempts to increase cessation have focused on increasing success after a quit attempt (Zhu et al., 2012). Another method to increase cessation is to increase the number of quit attempts. Prior research on quit attempts has focused on demographic, or smoking characteristics as predictors of quit attempts (McCaul et al., 2006; Smith, et al., 2013; Vangeli et al., 2011). Several studies have asked smokers why they tried to quit smoking or asked about introspective states such as motivation to quit or self-efficacy. These studies were either retrospective or, if prospective, asked about quit attempts over a several month time period. To our knowledge, the current study is the first prospective study examining proximal predictors of quit attempts.

Our study focused on environmental cues as predictors of a quit attempt. One of the reasons for this focus was that several retrospective surveys (Resnicow et al., 2014) and our prospective study (Hughes et al., 2014) found that 23-73% of quit attempts appear to be spontaneous; i.e., on the day prior to the quit attempt there was no plan to quit the next day. One possible cause of such spontaneous attempts is that the introspective states have increased over time and finally reached some threshold level that lead to a quit attempt (West, 2006). However, another possible explanation is that some salient, smoking-related, environmental event occurred in close temporal proximity to the quit attempt, or that the effect of cues summated over time to prompt an attempt to quit (West, 2006). We are unaware of prior studies on the incidence of stop smoking cues. In our study, cues to stop smoking were fairly common, averaging about one a day. The most commonly cited cues were those due to social or external pressure: i.e., embarrassment, media message, someone commenting on their smoking, and cues about cost. For example, almost half of smokers said they were embarrassed about their smoking on a weekly basis. These results suggest tobacco control efforts to denormalize (i.e. stigmatize) smoking (Warner and Tam, 2012) are having their intended effects.

Our finding that the number of cues predicted the probability of a quit attempt showed a within-participant effect; i.e., when a participant had a week with many cues occurring, he/she was more likely to make a quit attempt than in a week in which he/she had few cues occurring. This effect was more salient among smokers who typically had fewer cues occurring. Surprisingly, more proximal cues were not more powerful. This finding, in combination with our finding that the probability of quitting was dose-related to the number of cues, suggests that the effect of cues on quit attempts is due to a cumulative effect over time, rather than a salient cue immediately prior to the quit attempt. This interpretation is consistent with predictions from the PRIME and other theories of addiction (West, 2006). In addition, our finding that changes in the number of cues within a participant over time prospectively predict quit attempts more strongly suggests causality than prior between participant findings in retrospective studies (Gordis, 2004).

In terms of specific cues, cues that raised concern about the cost of cigarettes were the most reliable predictor of quit attempts. This is consistent with most reports that increasing cost is the tobacco control activity that most reliably increases quitting (Resnicow et al., 2014) but contrasts with retrospective surveys that most frequently report health reasons and/or physician advice are the main reasons for quitting (McCaul et al., 2006). The only prior study specifically examining environmental cues asked quitters to retrospectively report which cues contributed to their making a quit attempt (Ussher et al., 2013). Advice from a health care provider and a new or worsened tobacco related symptom were the two most common cues in that study (right hand column, Table 3). One possible explanation for the discrepancy is that our study was prospective and the prior studies were retrospective and thus could have been influenced by biased recall (Borland et al., 2012). Another possibility is that we asked participants only to report the occurrence of cues but not whether they believed the cue contributed to quitting; i.e., we did not ask about reasons nor attributions. Attributions (i.e., reasons) about behavior change are often not validated in prospective studies (Shiffman and Waters, 2004). For example, smokers may be reluctant to cite external factors (such as cost) as a cause of their behavior change because quitting due to cost may be thought of as succumbing to external pressure, thereby undermining internal attributions for behavior change.

The number of cues did not predict the duration of abstinence among those who made a quit attempt; however, this may be because quit attempts were very short-lived; i.e., most did not even last a day. In addition, recent analyses have found that different variables may predict quit attempts vs duration of abstinence once an attempt is made (Vangeli et al., 2011).

4.3 Limitations and Assets

First, although prospective prediction is thought of as a stronger indication of causality than retrospective association (Gordis, 2004), it cannot prove causality. For example, increased number of cues may be a marker for increased tobacco control activity in a smoker's local environment, and tobacco control activity, not number of cues, may cause increased quitting. Also, perhaps smokers who are more motivated to quit may recognize cues more readily than smokers less motivated to quit. Second, we focused on quit attempts. Although, logically, increasing quit attempts should increase cessation, some recent data suggests that, in some smokers this is not the case (Partos et al., 2013). Third, because there were no prior publications identifying possible cues, we developed a list of cues using qualitative methods among small samples of smokers, and we may have omitted some important proximal cues. Fourth, we did not include several cues that occur infrequently and thus would be unlikely to occur within the 3-month duration of our study; e.g., new restrictions on smoking or new media campaigns. Fifth, we examined cues only over 7-day periods. We did so, because we were interested in proximal cues and believed that more distal cues would be less relevant; however, we found that cues on 7 days prior to the eighth day were still predicting quit attempts. Thus, cues even more distant may still predict quit attempts. Sixth, we did not assess the salience of each cue; e.g., embarrassment and a heart attack were treated equally. Seventh, other than intention to smoke or not on the evening of the 7th day, we did not examine changes in introspective states to see how they might interact with the effects of cues. Eighth, for efficiency of effort, we examined only smokers intending to quit in the next 3 months. Prior studies have shown that even smokers without such an intent will make quit attempts (West, 2005; Jardin et al., 2014); thus, future studies should include such smokers. Ninth, we did not biochemically verify reports of smoking or abstinence. We think falsifications were likely rare given that reimbursement was not mentioned in the ads plus recent reviews state biochemical verification is usually not necessary in non-treatment, minimal contact studies (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002).

The major assets of our study include a) prospective design, b) large sample size, c) “real world” quitters, d) focus on proximal events, e) high compliance with reporting, and f) statistical methods that focused on within-participant effects. Also, our finding of poor retrospective recall of cues for quitting suggests intensive prospective studies likely provide more valid estimates of the triggers of quit attempts than retrospective studies covering the last several months.

4.4 Conclusion

In summary, our results suggest that external factors such as environmental events play a role in the occurrence of quit attempts. They also suggest that the effect of these events is cumulative. This suggests that each time a comment by a clinician, relative, friend, the media, etc., occurs, this pushes the smoker closer to making a quit attempt. Further research is needed to see whether a) there are important proximal cues that we did not measure, b) threshold or ceiling effects occur, c) the salience of the cue is important, d) cognitive states and cues interact, and e) experimental manipulation of cue frequency increases quit attempts.

Highlights.

Several environmental cues predicted future quit attempts in a dose-related manner

Cues related to the costs of cigarettes were the strongest predictor

The effect of cues on quit attempts appeared to be cumulative over time

These results differ from retrospective recall of reasons for quitting

Acknowledgements

We thank Emily Casey, Ginger Cloud, Miki Dash, Tonya Ferraro, Matthew MacKinnon, Sharon Muellers, Adam Rhodes-Rogan, and Beth Walsh for their help in the conduct of the study, and Ron Borland and Saul Shiffman for comments on our report.

Role of funding source

This work was supported by U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA-025089). The institute had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Drs Callas, Hughes, and Solomon designed the study. Drs Fingar, Hughes, and Solomon conducted the study. All authors were involved in data analysis and the writing of the paper. All authors have approved the final manuscript

Declaration of Interests

Dr Hughes has received grants and consulting fees from many for-profit and nonprofit companies that develop or sell smoking cessation products and services or engage in tobacco control education or advocacy. None of the other authors have anything to declare.

REFERENCES

- Berg C, An L, Kirch M, Guo H, Thomas J, Patten CA, Ahluwalia JS, West R. Failure to report attempts to quit smoking. Addict. Behav. 2010;35:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland R, Partos T, Yong H, Cummings K, Hyland A. How much unsuccessful quitting activity is going on among adult smokers? Data from the International Tobacco Control 4-Country cohort survey. Addiction. 2012;107:673–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkrey R, Parkinson L. Interactive voice response: review of studies 1989-2000. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2002;34:342–353. doi: 10.3758/bf03195462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordis L. Epidemiology. Third Edition. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Naud S, Fingar J, Helzer JE, Callas P. Natural history of attempts to stop smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16:1190–1198. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Agaku I, O'Connor E, King B, Kenemer J, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults - United States, 2005-2013. MMWR. 2014;63:1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardin B, Cropsey KL, Wahlquist AE, Gray KM, Silvestri GA, Cummings M, Carpenter MJ. Evaluating the effect of access to free medication to quit smoking: a clinical trial testing the role of motivation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16:992–999. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larabie LC. To what extent do smokers plan quit attempts? Tob. Control. 2005;14:425–428. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul K, Hockemeyer J, Johnson R, Zetocha K, Quinlan K, Glasgow R. Motivation to quit using cigarettes: a review. Addict. Behav. 2006;31:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Zimmerman RS. Health Behavior Theory and cumulative knowledge regarding health behaviors: are we moving in the right direction? Health Educ. Res. 2005;20:275–290. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partos T, Borland R, Yong H-H, Hyland A, Cummings K. The quitting rollercoaster: How recent quitting history affects future cessation outcomes. Data from the International Tobacco Control 4-Country Cohort Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013;15:1578–1587. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki T. Relapse to smoking. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006;26:196–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Zhou Y, Scheuermann T, Nollen N. Unplanned quitting in a triethnic sample of U.S. smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014;16:759–765. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychol. Assess. 2009;21:486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ. Negative affect and smoking lapses: a prospective analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:192–201. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AL, Chapman S, Dunlop S. What do we know about unassisted smoking cessation in Australia? A systematic review, 2005-2012. Tob. Control. 2013;24:18–27. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher M, Brown J, Rajamanoharan A, West R. How do prompts for attempts to quit smoking relate to method of quitting and quit success? Ann. Behav. Med. 2013;47:358–368. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106:2110–2121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner K, Tam J. The impact of tobacco control research policy: 20 years of progress. Tob. Control. 2012;21:103–109. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R. Time for a change: putting the Transtheoretical (Stages of Change) Model to rest. Addiction. 2005;100:1036–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R. Theory of Addiction. Blackwell Publishing; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- West R, Sohal T. Catastrophic pathways to smoking cessation: findings from a national survey. BMJ. 2006;302:458–460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38723.573866.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S-H, Lee M, Zhuang Y-L, Gamst A, Wolfson T. Interventions to increase smoking cessation at the population level: How much progress has been made in the last two decades? Tob. Control. 2012;21:110–118. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]