Abstract

Background

U.S. breast cancer deaths have been declining since 1989, but African American women are still more likely than white women to die of breast cancer. Black-white disparities in breast cancer mortality rate-ratios have actually been increasing.

Methods

Across 762 U.S. counties with enough deaths to generate reliable rates, we examined county-level age-adjusted breast cancer mortality rates for women aged 35–74 during the period 1989–2010. Twenty-two years of mortality data generated 20 three-year rolling average data points, each centered on a specific year from 1990 – 2009. We used mixed linear models to group each county into one of four mutually exclusive trend patterns. We also categorized the most recent three-year average black breast cancer mortality rate for each county as being worse than or not worse than the breast cancer mortality rate for the total U.S. population.

Results

More than half of counties (54%) showed persistent, unchanging disparities. Roughly one in four (24%) had a divergent pattern of worsening black-white disparities. However, 10.5% of counties sustained racial equality over the 20-year period, and 11.7% of counties actually showed a converging pattern from high disparities to greater equality. Twenty-three counties had 2008–2010 black mortality rates better than the U.S. average mortality rate.

Conclusion

Disparities are not inevitable. Four U.S. counties have sustained both optimal and equitable black outcomes, as measured by both absolute (better than US average) and relative (equality in local black-white rate-ratio) benchmarks for decades, while six counties have shown a path from disparities to health equity.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Disparities, Equity, Race, Local-Area Variation, Mortality Trends

Introduction

Breast cancer mortality rates are declining in the U.S.1 Since 1990 there has been a 3.2% decrease in breast cancer mortality for women under age 50, and a 2.0% decrease for women over age 50. However, the benefits of decreasing mortality have not accrued equally to all segments of the population. The racial (black-white) gap in breast cancer mortality has been increasing since the 1990s.2,3 Despite having a lower incidence of breast cancer, African American women are more likely to die of breast cancer at every age, with 30.8 deaths per 100,000 women, compared to 22.7 deaths per 100,000 for White women.4 These racial disparities appear to have emerged since the 1970’s, during the very time when more effective screening, early detection, and treatment combined to decrease overall mortality rates. For example, from 2001 to 2010, the decrease in breast cancer deaths was smaller (1.6%) for black women and Hispanic / Latina women (1.7%) than it was for non-Hispanic white women (1.8%) and Asian women (1.0%).5 African American women now experience a 41% higher mortality rate than non-Hispanic white women.6 More recent data from the 50 largest US cities confirmed this trend of increasing racial disparities as measured by a black-white mortality rate ratio, with a rate ratio of 1.17 in 1990–1994 rising to 1.40 in 2005–2009.7

However, these racial differences in breast cancer mortality trends are not the same in every geographic community.8 There is tremendous local-area variation, not only in cancer mortality rates, but also in racial-ethnic disparities in these rates.9,10 This local-area variation suggests that the pattern of widening disparities during overall mortality decline is not inevitable. Risk factors or “determinants” of racial disparities in health outcomes have been well documented, but there has been less focus on positive progress toward equality.11 Specifically, are disparities pervasive and persistent everywhere, or are there communities that could show us a pattern of decreasing health disparities and thus a path to health equity?

Therefore, we studied county-level black-white disparity trends in breast cancer mortality over two decades, specifically looking for counties that showed each of the following patterns in their progress toward more equitable breast cancer outcomes – sustained equality (overlapping trend lines), persistent (parallel) inequality, worsening disparities (diverging trend lines) and progress toward equality (converging trend lines). Thus a more “equitable” outcome refers to a trend in which the breast cancer mortality is improving for both groups but also becoming more equal (disparities rate-ratio is declining). Because black-white equality could occur at high mortality rates as well as low, we also assessed whether age-adjusted black female breast cancer mortality rates at the county level were below the national average for all women (even recognizing that those rates may still be higher than “best-group” outcomes). If all of these patterns are occurring in at least some counties in the U.S., then it is indeed possible to achieve more optimal and equitable breast cancer outcomes across racial groups.

Materials and Methods

Data

Our initial sample included 3,140 U.S. counties and county equivalents. We compiled county-level data from two sources, including county-level mortality rates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Compressed Mortality File (CMF),12 and county-level socioeconomics and contextual variables from the US Census Bureau.13 The CDC describes the Compressed Mortality data as having mortality and population counts for all U.S. counties, with counts and rates of death coded by underlying cause of death, state, county, age, race, sex, and year. County-level data representing fewer than ten deaths or fewer than ten persons in any sub-group population count in the denominator are suppressed to protect confidentiality. Causes of death for data from CMF years 1979–1998 are listed as 4-digit ICD-9 codes with 72 cause-of-death recodes; for years from 1999 forward the CMF provides 4-digit ICD-10 codes with 113 cause-of-death recodes.

We examined county-level Black/White disparities in breast cancer age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000 women aged 35 –74 during the study period of 1989–2010. We adjusted the mortality rates using age distributions from the year 1989–2010 U.S. population, which allowed us to compare the rates over time and reduce the potential for confounding by age.

Some counties had small population sizes and reported relatively few breast cancer deaths during the study period. We selected counties with at least eleven annual breast cancer deaths (963 counties). To adjust for instability of rates from small areas, we used three-year rolling averages as a smoothing technique. While this helps reduce random fluctuations and generates a larger sample size for each data point, it does not account for all the potential non-linearities that might occur in each county over 20 years. For example, the age-adjusted three-year average mortality rate for 2000 is the average of three years data in that county, e.g., mortality rates from 1999, 2000, and 2001. Thus 22 years of annual rates from 1989 to 2010 generated 20 three-year rolling average data points (each three-year rolling average data point centered on a specific year, from 1990 through 2009). To construct 20-year trend lines, we excluded counties with incomplete records (all counties with less than 17 years of reported breast cancer cases for either racial group were excluded), resulting in a final sample of 762 counties from 41 states.

Categorizing racial disparity trend patterns (progress toward health equity)

We grouped each county into one of four mutually exclusive patterns of black/white racial disparity trends in age-adjusted breast cancer mortality. These categories were the following:

Persistent disparities (mortality trends were perhaps improving, but black-white trend lines were parallel -- gap remained unchanged);

Sustained equality (black and white mortality were essentially equal and trend lines were overlapping throughout the study period);

Converging toward equality;

Diverging to greater disparities (increasing black-white gap)

We calculated the ratio of Black/White age-adjusted mortality rates, and used a mixed linear model to estimate the disparities trends across 20 three-year rolling average datapoints at the county level. We set the black-white rate-ratio as the outcome and time as an independent variable. The intersect was set up as the only random effect in the model. Estimation method was specified as maximum likelihood. Among alternative covariance structures for the mixed linear models, we used the unstructured covariance matrix, so we would not impose any constraints on the values. We defined a “converging toward equality” trend pattern as one in which the slope of the black/white mortality rate ratio over time was significantly less than zero (p <.05). Counties with a slope of the black/white breast cancer mortality rate ratio over time significantly greater than zero (p <.05) were defined as diverging (increasing disparities gap). For each remaining county (e.g., those with black/white mortality rate ratio not changing [slope not significantly different than zero over time]), we used a paired t-test to separate those with persistent inequality from those with sustained equality. Conclusions would not be altered by choosing an absolute rate difference measure of disparities instead of the rate-ratio.

Categorizing current black mortality rates as optimal or not optimal

It is important not only to achieve equality, but also to achieve equality at a low mortality rate. Equality in settings where white women were dying at the higher rates of African American women would not be a positive finding, so we developed an approach to identify counties which were achieving both absolute improvements (relative to the US population average) in breast cancer mortality rates as well as black-white equality in outcomes. Therefore, we categorized each county with the most recent (2008–2010) black mortality rate as better than the overall U.S. population average (more optimal), and other counties as not better than the U.S. average (less optimal).

Results

We were able to categorize all 762 counties from 41 states into one of four trend patterns over the 20-year study period (Table 1). Unfortunately, more than three-fourths of counties showed either persistent, unchanging disparities (53.8%), as measured by black-white rate-ratios, or a divergent pattern (24.0%) of worsening disparities (i.e., increasing black-white rate-ratios). The good news is that disparities are not inevitable – 10.5% of counties had actually achieved equality and were sustaining it over the 20-year study period. Even more relevant in our quest for paths to health equity, 11.7% of counties actually showed a converging pattern of black-white mortality trends, e.g., moving from high disparities to greater equality. Figure 1 shows the black and white mortality trend lines for counties aggregated into their four trend pattern groups.

Table 1.

US counties categorized by black-white racial disparities patterns over time for age-adjusted breast cancer mortality from 1989–2010

| Region* | Convergent | Divergent | Consistent Equal |

Persistent Unequal |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #(%) | 89 (11.7%) | 183 (24.0%) | 80 (10.5%) | 410 (53.8%) | 762(100%) |

| Middle West | 9(10.71%) | 23(27.38%) | 6(7.14%) | 46(54.76%) | 84(11.02%) |

| North East | 10(14.08%) | 28(39.44%) | 9(12.68%) | 24(33.80%) | 71(9.32%) |

| South | 65(11.40%) | 123(21.58%) | 61(10.70%) | 321(56.32%) | 570(74.80%) |

| West | 5(13.51%) | 9(24.32%) | 4(10.81%) | 19(51.35%) | 37(4.86%) |

US Census Divisions:: Middle West: Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska, Illinois, Kansas, North Dakota, Michigan, Minnesota, South Dakota, Ohio, Missouri, Wisconsin;

North East: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania;

South: Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Texas;

West: Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, New Mexico, Montana, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington;

Figure 1.

Four patterns of county-level black/white racial disparity trends, 1989–2010

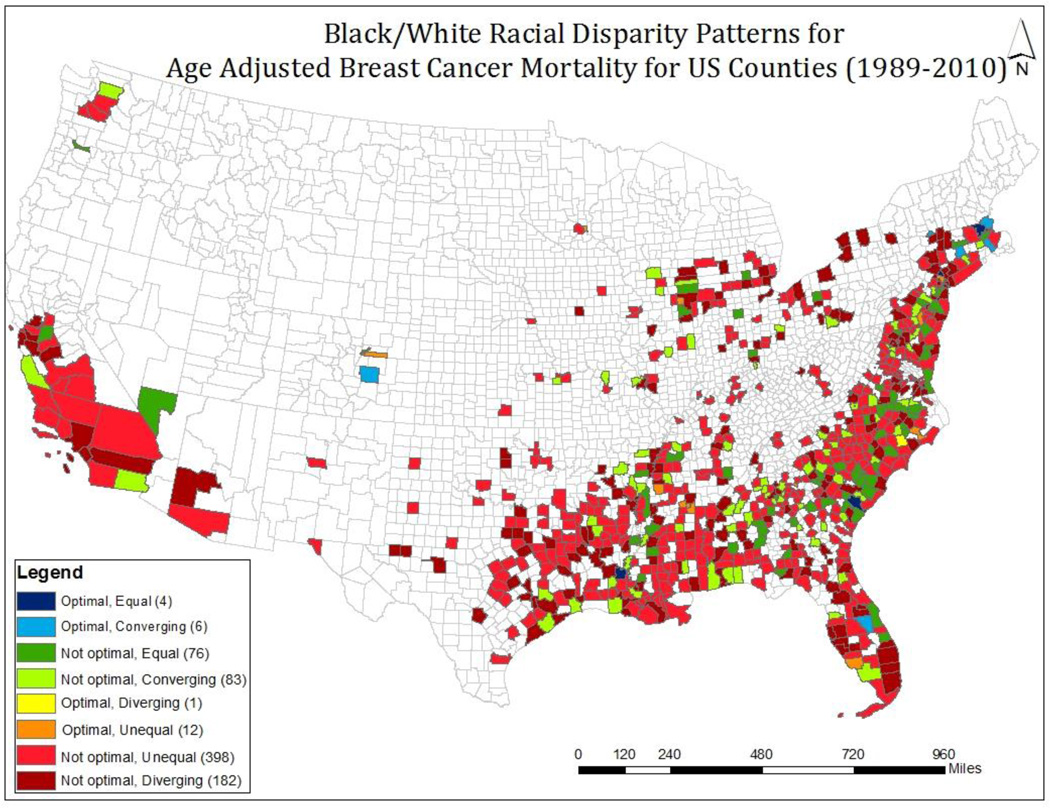

Twenty-three counties showed 2008–2010 black mortality rates better than the U.S. overall population mortality rate (more optimal). This included nearly 10% of counties in the Northeastern US Census Region, but only 2% of those in the Southern and the Midwest Regions. In only ten counties in the nation did black or African American women achieve both optimal (better-than-national average) and equitable (equal to local county-level rates for white women) breast cancer outcomes. Of these, four counties sustained equality over the entire twenty-year period, and six counties began the study period with high disparities but showed a converging pattern of progress toward outcomes equality. Demographic trends in these ten counties with more optimal and equitable breast cancer outcomes are shown in Tables 2 and 3. While most counties showed substantial increases in median income, the percent of population with incomes below poverty level increased in some and decreased in others. Figure 2 shows a map of counties in each of the eight final categories of more optimal and equal outcomes (better than or not better than U.S. average current outcomes combined with four disparity trend patterns of converging, diverging, persistent inequality, and sustained equality).

Table 2.

US counties with convergent racial disparities trend lines and better-than-national-average” (more optimal*) breast cancer mortality rate

| County | Year | Population | % White | % Black | Median Income ($) |

% persons below poverty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osceola, FL | 2010 | 268,685 | 71 | 11.3 | $42,165 | 16.3 |

| 1990 | 107,700 | 89.3 | 5.5 | $27,260 | 9.4 | |

| % change | +149.5% | −20.5% | +105.5% | +54.7% | +73.4% | |

| Schenectady, NY | 2010 | 154,727 | 79.6 | 9.5 | $52,062 | 12 |

| 1990 | 149,300 | 93.7 | 4.3 | $31,569 | 8.3 | |

| % change | +3.6% | −15.0% | +120.9% | +64.9% | +44.6% | |

| El Paso, CO | 2010 | 622,263 | 79.8 | 6.2 | $51,553 | 13.4 |

| 1990 | 397,000 | 86 | 7.2 | $29,604 | 10.4 | |

| % change | +56.7% | −7.2% | −13.9% | +74.1% | +28.8% | |

| Bristol, MA | 2010 | 548,285 | 88.4 | 3.3 | $51,361 | 12.8 |

| 1990 | 506,300 | 95.3 | 1.6 | $31,520 | 9.1 | |

| % change | +8.3% | −7.2% | +106.3% | +62.9% | +40.7% | |

| Essex, MA | 2010 | 743,159 | 81.9 | 3.8 | $61,604 | 10.4 |

| 1990 | 670,100 | 92 | 2.4 | $37,913 | 9.3 | |

| % change | +10.9% | −11.0% | +58.3% | +62.5% | +11.8% | |

| Hartford, CT | 2010 | 894,014 | 72.4 | 13.3 | $60,028 | 11.3 |

| 1990 | 851,800 | 83.5 | 10.2 | $40,609 | 7.9 | |

| % change | +5.0% | −13.3% | +30.4% | +47.8% | +43.0% |

More Optimal = 2008–2010 African American age-adjusted breast cancer mortality below US average

Table 3.

Counties with persistently equal racial disparities pattern (sustained equality) and better-than-national-average” (more optimal*) breast cancer mortality rate

| County | Year | Population | % White | % Black | Median Income ($) |

% persons below poverty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoyelles, LA | 2010 | 42,073 | 67 | 29.5 | $31,523 | 21.6 |

| 1990 | 39,200 | 72.3 | 27 | $13,451 | 37.1 | |

| % change | +7.3% | −7.3% | +9.3% | +133.6% | −41.8% | |

| Middlesex, MA | 2010 | 1,503,085 | 80 | 4.7 | $75,364 | 8.2 |

| 1990 | 1,398,500 | 92.1 | 2.9 | $43,847 | 6.2 | |

| % change | +7.5% | −13.1% | +62.1% | +71.9% | +32.3% | |

| Rockland, NY | 2010 | 311,687 | 73.2 | 11.9 | $79,798 | 11.6 |

| 1990 | 265,500 | 83.9 | 10 | $52,731 | 6.4 | |

| % change | +17.4% | −12.8% | +19% | +51.3% | +81.3% | |

| Colleton, SC | 2010 | 38,892 | 57 | 39 | $32,446 | 22.6 |

| 1990 | 34,400 | 54.3 | 45 | $20,617 | 23.4 | |

| % change | +13.1% | +5.0% | −13.3% | +57.4% | −3.4% |

More Optimal = 2008–2010 African American age-adjusted breast cancer mortality below US average

Figure 2.

Black/White racial disparity trend patterns for age-adjusted breast cancer mortality for US counties (1989–2010)

Discussion

Although black-white racial disparities in breast cancer mortality are widening at a national level, the results of our study demonstrate that the trend lines for black and white cancer mortality vary significantly by county and can be grouped into four categories: persistent disparities, sustained equality, converging toward equality and diverging toward greater disparities. This county-level variation is consistent with previous studies.14,15 Unfortunately, most counties showed persistent or even worsening disparities. However, our study also demonstrated that racial disparities in cancer outcome are not inevitable. Some counties have sustained black-white equality over twenty years. Other counties showed that progress from high-disparities to more optimal and equal cancer outcomes is also achievable.

This paper focuses on racial-ethnic disparities in outcomes. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) defines "cancer health disparities" as "differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of cancer and related adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the United States," which may be thought of as outcome inequalities. In this usage, achieving racial-ethnic equality in cancer outcomes would represent a strong benchmark of cancer health equity, while achieving equality or sameness in access and care for all sub-groups of the population (despite varying needs and resources) would not. In the simplest example, providing state-of-the-art cancer care with English-language providers to all patient groups “equally” would result in disadvantage and lesser quality of care for non-English proficient patients. In this case, equity would demand “unequal” treatment if linguistically-appropriate care for non-English speakers required additional resources. (If high quality care is re-defined instead as state-of-the-art, culturally and linguistically-appropriate cancer care by a health care team that is culturally and linguistically synchronous with the patient, then equality of care begins to approach “equitable” care). Therefore, moving from outcome disparities to equality of outcomes is indeed a path to health equity, while moving all patient sub-groups to equality (sameness) in access and care would not be.

Our analysis is based on the premise that “optimal” (absolute rate compared to a benchmark) and “equitable” (equality of one group relative to another, as in a rate-ratio) are two different measures and both are important. Should we still be concerned about persistent outcome inequalities if both blacks and whites are doing fairly well (e.g., mortality below the national average)? Certainly, if a county shows both blacks and whites achieving mortality rates below the national average, that is a good thing (more optimal outcomes), but the inequality of outcomes shows that there are still lives to be saved by eliminating racial variation in mortality rates. Further, if we used “best outcome racial group” as the benchmark, we would see that almost every community could still save lives by eliminating racial-ethnic variation and moving all groups to the benchmark best-achievable outcomes.

Potential contributing factors to disparities in breast cancer mortality are complex and multifaceted, including both biological and social determinants, as well as healthcare access and quality, health literacy, and health behaviors.16,17 The strongest body of research links local-area variation in disparities to socioeconomic factors, including poverty at the individual and neighborhood levels.18 Women of low socioeconomic status (SES) and the uninsured are more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, and they are also less likely to have access to advanced technologies.19,20 Underserved groups are more likely to reside in neighborhoods with decreased access to sidewalks, parks, and healthy foods, which may place them at greater risk of obesity as well as decreased access to healthcare.21,22

Lack of transportation has been reported to be a barrier to screening mammography23 and is assumed to be a factor associated with lower breast cancer screening rates, but a ten-state, multilevel analysis did not show travel time to screening facility to be a risk factor for being diagnosed at an advanced stage (but race, poverty, and lack of health insurance were significant risk factors).24 Research has shown an inverse association between educational attainment and cancer mortality.25 Several studies also report decreased access to cancer screening and worse outcomes for women in rural areas,26, 27 although one Chicago study showed an urban disadvantage.28

To the extent that declines in cancer-related mortality over the past 20 years can be attributed to improvements in early cancer detection and more effective treatments,29,30 then unequal diffusion of medical advances could also be widening the disparities gap between black and white persons.31 Phelan argued that rapid improvements in treatment or health promotion are distributed unequally based upon disparities in knowledge, money, power, prestige, and social connections, so that individuals with higher income, better knowledge, and better connections are more likely to benefit from improved technology.32,33 Advantaged segments of the population may be better educated, better insured, and more highly resourced, leading to higher and quicker utilization of mammography, diagnostic screening tests, and cutting-edge cancer treatments.34–40

Biologic differences could also be unmasked by improved treatments. For example, it is possible that the development of effective treatments for receptor-positive cancers unmasked inadequacies in our treatment of triple-negative breast cancer, which is more common among black or African American women.41–42 These more aggressive cancers are a biological source of racial variation in outcomes, but do not explain local-area variation in black or African American outcomes.

Much additional research is needed to explain why different communities are on such different paths toward increasing or decreasing disparities. However, the finding that certain counties show good minority group outcomes with black mortality rates better than the US average and relative black-white equality in mortality rates suggests that disparities are not inevitable. This extends and confirms previous research which found positive outlier communities with more optimal and equitable outcomes in overall mortality and mortality not only from breast cancer, but also related to HIV-AIDS and infant mortality.43–46

A few communities in our study even improved from high disparities and poor cancer outcomes to a trend line of more optimal and equitable outcomes. Our finding that a group of counties had converging black and white trend lines suggests that there may be a path to health equity for communities currently experiencing high disparities. Interestingly, none of these counties are in the top ten U.S. counties for African American median income.47,48

In our study, three of the counties with optimal rates that were either equal or converging are located in the state of Massachusetts, which not only implemented health insurance reform in 2006, but may also have a more cohesive safety net health system (tighter integration of safety net primary care with sub-specialty care).49 It is plausible that the expansion of health insurance coverage in the state played a role, e.g., black women were 1.75 times more likely to receive a mammogram than white women after health reform in Massachusetts.50 Outside of Massachusetts are geographic outlier communities such as Avoyelles Parish, LA and Colleton County, SC, which have obtained persistently equal and optimal rates for black women, in contrast to neighboring counties in the region.

Perhaps this study can help accelerate a shift in the national dialogue on disparities from a backwards look at risk factors and "determinants" to a forward-looking conversation about how to identify assets and strategies that enable communities to move from high disparities to greater equality. What do Osceola (Florida), Schenectady (New York), and Hartford (Connecticut) have in common with each other and with Bristol and Essex counties in Massachusetts? What have they done differently over the past twenty years? Or are the communities themselves changing?

Demographic trends (table 4) suggest that improved minority health outcomes and racial equality may be partially due to in-migration of more high-income, highly-educated African Americans. However, many communities that have experienced this migration pattern have not seen a concomitant resolution of health disparities. Something in the interaction between persons (including health behaviors), and communities (including health care systems) also changed during these decades.

Table 4.

Demographic trends (1990–2010) in counties by breast cancer disparity trend pattern groups

| County Characteristics Grouped by Disparities Trend |

Convergent toward Equality | Divergent (Widening Disparities) | Sustained Equality | Persistent Inequality | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern Year |

1990 | 2010 | 20-year % Change |

1990 | 2010 | 20-year % Change |

1990 | 2010 | 20-year % Change |

1990 | 2010 | 20-year % Change |

| Total Population | 12,666,964 | 17,678,375 | 39.6% | 83,265,089 | 100,986,137 | 21.3% | 13,442,215 | 17,542,195 | 30.5% | 64,461,081 | 81,568,264 | 26.5% |

| White as Percent of Population | 84.09% | 79.85% | −5.0% | 64.77% | 69.25% | 6.9% | 78.34% | 73.57% | −6.1% | 73.84% | 74.99% | 1.6% |

| Black or African American as Percent of Population | 8.80% | 12.81% | 45.6% | 17.75% | 19.43% | 9.5% | 12.90% | 15.69% | 21.6% | 14.58% | 15.97% | 9.5% |

| Percent of counties in that category with Median Household Income below US Average* | 56.18% | 51.69% | −8.0% | 69.95% | 69.95% | 0.0% | 70.00% | 75.00% | 7.1% | 78.05% | 77.32% | −0.9% |

| Median Household Income | $ 23,905 | $ 4 2,665 | 78.5% | $ 25,368 | $ 44,356 | 74.9% | 21,386 | $ 36,701 | 71.6% | $ 23,666 | $ 41,727 | 76.3% |

| Median Black Household Income (458 counties only) | $ 15,670 | $ 3 7,821 | 141.4% | $ 15,763 | $ 31,709 | 101.2% | 15,018 | $ 35,090 | 133.7% | $ 14,834 | $ 30,336 | 104.5% |

| % persons with income below poverty level | 12.7 | 17.1 | 34.6% | 15.3 | 17.3 | 13.1% | 19.35 | 21.3 | 10.1% | 15.45 | 18.2 | 17.8% |

Specific interventions may also make a difference. For example, a cancer control program started by the Delaware Cancer Consortium in 2003 included three key elements: a colorectal cancer screening program, a cancer treatment program providing for the uninsured, and an emphasis on reducing African American cancer disparities. By 2009, the disparities in colorectal cancer screening, incidence, and advanced disease stage were eliminated, and the difference in mortality rates between whites and African Americans was declining in Delaware.51 In other cases, there may need to be a critical mass of many positive community attributes and multi-dimensional interventions to achieve equity-related outcomes, as in “the apparent elimination” of the black-white infant mortality gap in Dane County Wisconsin from 1990–2007.52

These positive deviance communities, (i.e., communities which have moved from high racial disparities to more optimal and equitable outcomes) can become model communities for studying ways to improve outcomes in communities that are currently stuck in a persistently high disparity pattern. The road out to health equity may not be the same as the road which led in to high disparities. Further research will be needed to tease out whether communities achieving optimal and equitable breast cancer outcomes demonstrate improvements at every level of screening, detection, time-to-diagnosis, stage-at-diagnosis, time-to-treatment, and quality of treatment, or whether there are specific leverage points which were critical drivers of success in these communities. This line of research will help guide interventional trials that target specific leverage points identified in these communities.

Our study has significant limitations. We did not have individual person-level death certificates or any linkages to medical records, so we could not control for stage at diagnosis, comorbidity profiles, or other clinical factors. We also did not have individual-level socioeconomic data such as income, poverty, education, or insurance status. Even so, the strength of this study is that it incorporates data from all death certificates for all U.S. counties with sufficient population size and diversity and numbers of deaths to generate stable rates. These rates make it clear that disparities are not universally persistent across all counties in America, and that health equity is indeed achievable.

Further research must seek to understand the positive attributes and determinants of success in communities moving from disparities to more optimal and equitable cancer outcomes, and to build models of characteristics and strategies that other communities might follow on their own path to health equity. Using these models, we can shift from defining the problem (including causes and risk factors) to testing effective interventions, informed by the natural experiments of what has worked in communities that are already moving toward health equity.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project included research project grant support from the Amgen Foundation, and from the following federal grants: career development support (Rust) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) grant # K18HS022444; and institutional support from the NIH Center of Excellence on Health Disparities (CEHD) grant # 1P20MD006881-02 and NIH / RCMI grant # 8U54MD007588. Dr. Levine received support from National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities Grant # P20MD000516.

Footnotes

There are no additional financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Brawley OW. Breast cancer trends of black women compared with white women. Archives of Family Medicine. 1999;8(6):521–528. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.6.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Figure 5b. Trends in Female Breast Cancer Death Rates by Race and Ethnicity, US, 1975–2010. [Accessed Sept 16 2014];Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013–2014. :7. Accessed at http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042725.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Table 2. Female Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates by Race, Ethnicity, and State, 2006–2010. [Accessed Sept 16 2014];Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013–2014. :3. Accessed at http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042725.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2013. [Nov. 10, 2014]. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, as cited in Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013–14, American Cancer Society, p.9. Accessed at http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042725.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Racial Disparities in Breast Cancer Severity — United States, 2005–2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2012 Nov 16;61(45):922–926. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6145a5.htm?s_cid=mm6145a5_w Nov. 10, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunt BR, Whitman S, Hurlbert MS. Increasing Black:White disparities in breast cancer mortality in the 50 largest cities in the United States. Cancer epidemiology. 2014;38(2):118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh G, Miller B, Hankey B, et al. Area Socioeconomic Variations in U.S. Cancer Incidence,Mortality, Stage, Treatment, and Survival, 1975–1999. Vol. 2003. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan L, Mohile S, Zhang N, et al. Self-reported cancer screening among elderly Medicare beneficiaries: a rural-urban comparison. The Journal of rural health : official journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association. 2012;28(3):312–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farrow DC, Hunt WC, Samet JM. Geographic variation in the treatment of localized breast cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 1992;326(17):1097–1101. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rust G, Levine RS, Fry-Johnson Y, Baltrus P, Ye J, Mack D. Paths to success: optimal and equitable health outcomes for all. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012 May;23(2) Suppl:7–19. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.yearly data directly from the Compressed Mortality File obtained from the CDC/NCHS under a project-specific data use agreement.

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau. 2013 American Community Survey. [Accessed October 3 2014]; and 48 http://factfinder2.census.gov/rest/dnldController/deliver?_ts=430396426915.

- 14.Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Lian M, et al. The role of poverty rate and racial distribution in the geographic clustering of breast cancer survival among older women: a geographic and multilevel analysis. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169(5):554–561. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien LC, Deshpande AD, Jeffe DB, et al. Influence of primary care physician availability and socioeconomic deprivation on breast cancer from 1988 to 2008: a spatio-temporal analysis. PloS one. 2012;7(4):e35737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell RT, Li X, Dolecek TA, et al. Economic, racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer in the US: towards a more comprehensive model. Health & place. 2009;15(3):855–864. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cullen MR, Cummins C, Fuchs VR. Geographic and racial variation in premature mortality in the U.S.: analyzing the disparities. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e32930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94(7):490–496. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.7.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu KC, Miller BA, Springfield SA. Measures of racial/ethnic health disparities in cancer mortality rates and the influence of socioeconomic status. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1092–1100. 1102–1094. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker GV, Grant SR, Guadagnolo BA, et al. Disparities in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival in nonelderly adult patients with cancer according to insurance status. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(28):3118–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.6258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh GK, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. Neighborhood socioeconomic conditions, built environments, and childhood obesity. Health Affairs. 2010;29(3):503–512. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eheman C, Henley SJ, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2008, featuring cancers associated with excess weight and lack of sufficient physical activity. Cancer. 2012;118(9):2338–2366. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alexandraki I, Mooradian AD. Barriers related to mammography use for breast cancer screening among minority women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(3):206–218. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry KA, Boscoe FP, Johnson CJ, Goldberg DW, Sherman R, Cockburn M. Breast cancer stage at diagnosis: is travel time important? J Community Health. 2011 Dec;36(6):933–942. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9392-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albano JD, Ward E, Jemal A, et al. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99(18):1384–1394. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meilleur A, Subramanian SV, Plascak JJ, et al. Rural residence and cancer outcomes in the United States: issues and challenges. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2013;22(10):1657–1667. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuno T, Gerald JK, Harris R, et al. Comparison of breast and cervical cancer screening utilization among rural and urban Hispanic and American Indian women in the Southwestern United States. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2012;23(8):1333–1341. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLafferty S, Wang F. Rural reversal? Rural-urban disparities in late-stage cancer risk in Illinois. Cancer. 2009;115(12):2755–2764. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tehranifar P, Neugut AI, Phelan JC, et al. Medical advances and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer survival. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2009;18(10):2701–2708. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine RS, Rust GS, Pisu M, Agboto V, Baltrus PA, Briggs NC, Zoorob R, Juarez P, Hull PC, Goldzweig I, Hennekens CH. Increased Black-White disparities in mortality after the introduction of lifesaving innovations: a possible consequence of US federal laws. Am J Public Health. 2010 Nov;100(11):2176–2184. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers EM. 5th edition. Chapter 3. New York: Free Press; 2003. p. 130. Diffusion of Innovation “The Issue of Equality in Innovation”. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phelan JC, Link BG. Controlling disease and creating disparities: a fundamental cause perspective. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2005;60(Spec No 2):27–33. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phelan JC, Link BG, Diez-Roux A, et al. "Fundamental causes" of social inequalities in mortality: a test of the theory. Journal of health and social behavior. 2004;45(3):265–285. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akinyemiju TF, Soliman AS, Johnson NJ, et al. Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and healthcare resources in relation to black-white breast cancer survival disparities. Journal of Cancer Epidemiology. 2013;2013:490472. doi: 10.1155/2013/490472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel K, Kanu M, Liu J, et al. Factors influencing breast cancer screening in low-income African Americans in Tennessee. J Community Health. 2014;39(5):943–950. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9834-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McAlearney AS, Reeves KW, Tatum C, et al. Cost as a barrier to screening mammography among underserved women. Ethnicity & health. 2007;12(2):189–203. doi: 10.1080/13557850601002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peek ME, Han JH. Disparities in screening mammography. Current status, interventions and implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):184–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caplan LS, May DS, Richardson LC. Time to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1991–1995. American journal of public health. 2000;90(1):130–134. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ansell D, Grabler P, Whitman S, et al. A community effort to reduce the black/white breast cancer mortality disparity in Chicago. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2009;20(9):1681–1688. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(9):1357–1362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aysola K, Desai A, Welch C, Xu J, Qin Y, Reddy V, Matthews R, Owens C, Okoli J, Beech DJ, Piyathilake CJ, Reddy SP, Rao VN. Triple Negative Breast Cancer – An Overview. Hereditary Genet. 2013;2013(Suppl 2) doi: 10.4172/2161-1041.S2-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dignam JJ. Differences in breast cancer prognosis among African-American and Caucasian women. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2000;50(1):50–64. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine RS, Rust G, Aliyu M, Pisu M, Zoorob R, Goldzweig I, Juarez P, Husaini B, Hennekens CH. United States counties with low black male mortality rates. Am J Med. 2013 Jan;126(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levine RS, Kilbourne BE, Baltrus PA, et al. Black-white disparities in elderly breast cancer mortality before and after implementation of Medicare benefits for screening mammography. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved. 2008;19(1):103–134. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2008.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levine RS, Briggs NC, Kilbourne BS, et al. Black-White mortality from HIV in the United States before and after introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996. American journal of public health. 2007;97(10):1884–1892. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fry-Johnson YW, Levine R, Rowley D, et al. United States black:white infant mortality disparities are not inevitable: identification of community resilience independent of socioeconomic status. Ethnicity & disease. 2010;20(1) Suppl 1:S1-131–S1-135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staff A. Ten of the Richest Black Communities in America. [Accessed October 2, 2014]; Accessed at http://atlantablackstar.com/2014/01/03/10-richest-black-communities-america/5/. [Google Scholar]

- 48.U.S. Census Bureau. '2013 American Community Survey. [Accessed October 3 2014]; Available at http://factfinder2.census.gov/rest/dnldController/deliver?_ts=430396426915.

- 49.Van Der Wees PJ, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Improvements in health status after Massachusetts health care reform. The Milbank quarterly. 2013;91(4):663–689. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark CR, Baril N, Kunicki M, et al. Addressing social determinants of health to improve access to early breast cancer detection: results of the Boston REACH 2010 Breast and Cervical Cancer Coalition Women's Health Demonstration Project. Journal of women's health. 2009;18(5):677–690. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grubbs SS, Polite BN, Carney J, Jr, et al. Eliminating racial disparities in colorectal cancer in the real world: it took a village. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(16):1928–1930. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Apparent disappearance of the black-white infant mortality gap - Dane County, Wisconsin, 1990–2007. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2009;58(20):561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]