Abstract

Polyarteritis nodosa is a rare vasculitis in children characterized by necrotizing inflammation in small and medium size arteries. It is classified into systemic and cutaneous PAN according to the presence of systemic symptoms or visceral involvement. We describe the case of a 14-year-old girl with cutaneous Polyarteritis nodosa with an atypical clinical presentation.

Keywords: Child, Polyarteritis nodosa, Streptococcus pyogenes

INTRODUCTION

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis of small and medium arteries of the dermis and hypodermis and sometimes peripheral nerves and muscles.1,2 Pediatric diagnostic criteria are: evidence of necrotizing vasculitis in arteries of medium or small size on skin biopsy or angiographic abnormalities showing aneurysms or occlusions in arteries of medium or small size as mandatory conditions, and one of the next five criteria: 1 - cutaneous affectation (livedo reticularis, painful subcutaneous nodules, superficial and deep ulceration); 2-Myalgia or muscle pain; 3- Systolic or diastolic hypertension greater than 95th percentile for height and age of the patient; 4- Peripheral neuropathy and 5-Renal affectation (proteinuria > 0.3 g / day, hematuria or > 5 red blood cells per field or 2 or more crossing strips, glomerular filtration rate <50% for age and sex of the patient). 3

PAN is uncommon in children and in most cases, it occurs only with affectation of the skin (CPAN). Currently, CPAN is considered to be an inflammatory reactive condition secondary to infection by group A b-hemolytic streptococcus (GAS).4 In 2005, the European Rheumatological Societies agreed to add, as a criterion of CPAN, the serological evidence of streptococcal infection, recognizing the frequent association between this infection and PAN in children. 5-6

Cutaneous manifestations of CPAN can be painful erythematous nodules with a smooth surface that can sometimes coalesce to form large areas of hardened skin; livedo racemosa or reticularis, cutaneous ulceration and symptoms such as myalgia, arthralgia and non-erosive arthritis.7 The skin manifestations are usually limited to the lower extremities.8

Histopathologic examination of skin biopsies taken from the cutaneous manifestation reveals necrotizing vasculitis characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the affected vascular wall, neutrophilic infiltration with nuclear fragmentation in the vascular periphery, and erythrocyte extravasation in the vessels from the lower dermis to the subcutaneous fat. 7

We present the case of a patient with CPAN and atypical clinical evolution.

CASE REPORT

We report the case of a previously healthy 14-year-old girl who came to see us due to painful lesions of 6 months' duration on her thighs. The lesions had been interpreted as cellulitis at another institution and the patient had been treated with intravenous (IV) antibiotics (Clindamycin and Trimethoprim / sulfamethoxazole) for 7 days, with little response.

On dermatological examination, we observed erythematous and brownish plaques at the inner side of both thighs with multiple, underlying, painful, indurated nodules and, on the dorsal back, an injury with similar features (Figures 1 and 2). Additional tests were requested and the complete blood count (CBC) showed: white blood cells (WBC) 10280 mm3 (N 84%, L 10%, M 5%, E 1%); Hb: 12.8 g / dl, platelet count: 315000 mm3; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): 36 mm/h and c-reactive protein (CRP): 7 mg/l. Serologies were negative.

FIGURE 1.

Area of hardened skin in both thighs with livedo reticularis

FIGURE 2.

Tender red nodule at the inner side of the left arm

Histopathological biopsy and culture of the lesion were performed, showing discrete mixed inflammatory infiltrate consisting of histiocytes, lymphocytes, occasional eosinophils and isolated neutrophils with perivascular and periadnexal arrangement, and vasculitic phenomenon associated with extension to subcutaneous fat lobules and septa; diagnosis: mild nonspecific septal and lobular dermohipodermitis. The fungus Aureobasidium pullulans was isolated in a culture taken from the lesion. New nodules appeared in the arms, elbow folds and right ankle. The lesions at the thighs became painful and erythematous, which made walking difficult. She was admitted to hospital and received B amphotericin (total cumulative dose 1m/kg/day), Clindamycin 30 mg / kg / day and morphine 0.1 mg/kg/dose IV. During hospitalization, the patient showed partial remissions of the symptoms. Because of exacerbation of the pain, adding edema of upper and lower limbs, fever and coagulopathy (prothrombin time decreased), we decided to perform a new surgical biopsy and culture (Figure 3). This latter histology showed an "unaltered epidermis, the deep dermis and hypodermis had numerous small- and medium-sized vessels (some arterial) with occasional fibrinoid necrosis and fibrin microthrombi in small vessels. The infiltrate was rich in polymorphonuclear cells and eosinophils affecting the entire vessel diameter (disseminated leukocytoclastic vasculitis). The most preserved vascular structures showed intimal degeneration, prominent endothelium and marked perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figures 4, 5 and 6). PAS, Ziehl Nielsen, Giemsa staining and culture were negative. Because of the histological features, we arrived at the diagnosis of "Polyarteritis Nodosa."

FIGURE 3.

Edema at the left elbow and left hand

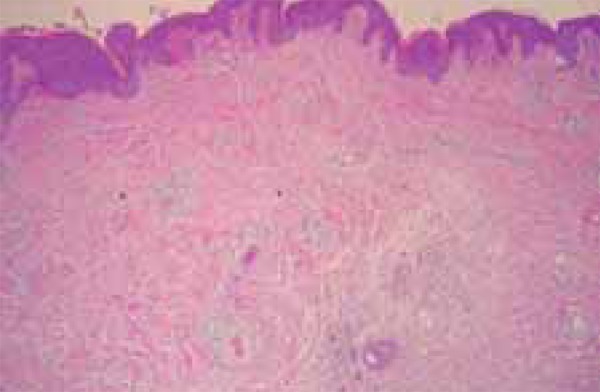

FIGURE 4.

H and E, 10x: shows normal epidermis and inflammatory infiltrate in dermis

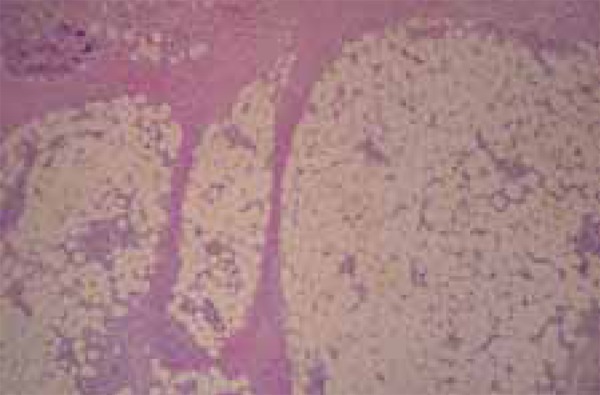

FIGURE 5.

H and E, 10x: shows inflammatory infiltrate around blood vessels in subcutaneous fat

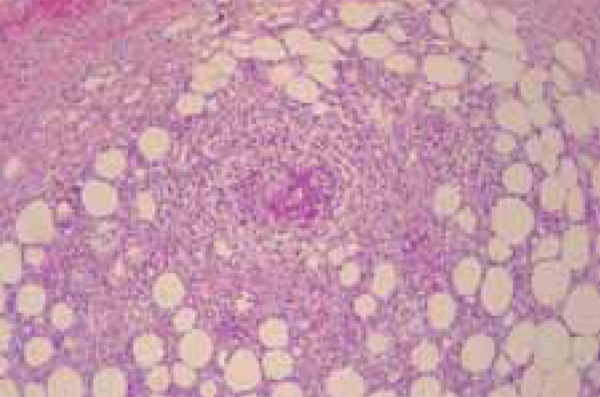

FIGURE 6.

H and E, 40x: shows destruction of the vessel walls by inflammatory infi ltrate in subcutaneous fat

New CBC reported leukocytosis and neutrophilia: WBC 13000 mm3 ( 71%N), increased ESR 76 mm/h and CRP 55 mg/l; complete metabolic panel (CMP) and urinalysis (UA) were normal; negative ANCA; negative throat culture and antiestreptolysin O (ASO) titers were 2580 IU / ml. Ophthalmologic and cardiac evaluations were normal. We performed abdominal CT angiography and thoracic CT, whose results were unremarkable.

She began a treatment with oral meprednisone 1.3 mg/kg /day for a month with gradual decline and intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin 2,400,000 UI every 28 days, which she still receives with a favorable response. She is periodically monitored at the Dermatology Department and shows no residual skin lesions or other systemic symptoms.

DISCUSSION

PAN is a vasculitis of small and médiumsize arteries, uncommon in children. At this age, the cutaneous form is more common than the systemic form and it is associated with streptococcal infection.9 Although the disease is chronic with relapsing, prognosis is generally good, with no visceral involvement.

Our patient presented a cutaneous PAN evidenced by necrotizing vasculitis of small and medium-size vessels in the dermis and hypodermis, with cutaneous involvement and myalgias. Although she had no medical history of streptococcal infection, this could be confirmed by measuring elevated ASO.

Initial cutaneous manifestations of the disease made us suspect a lymphoproliferative disease versus infectious process. As time elapsed, new symptons such as myalgia, arthralgia, fever and livedo reticularis in the thighs indicated a new deep skin biopsy through which we arrived at the diagnosis.

When the patient began treatment with corticosteroids and benzathine penicillin, she had a good clinical and laboratory response, which coincided with the description in the literature; even though there is no consensus on how long to keep the penicilin prophylaxis, this should be prolonged. 10

Other treatments described for PAN are immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate and mizoribine (an inhibitor of purine synthesis) with variable considerations. 7

Footnotes

Financial Support: None.

How to cite this article: Matteoda MA, Stefano PC, Bocián M, Katsicas MM, Sala J, Cervini AB. Cutaneous Polyarteritis Nodosa. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(3 Supl 1):S188-90

Study conducted at the National Hospital of Pediatrics “Prof. Dr. Juan P. Garrahan”, Buenos Aires ( Bs As), Argentina.

References

- 1.Segelmark M, Selga D. The challenge of managing patients with polyarteritis nodosa. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:33–38. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328011cb6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo RAG, Laterza AM, Katsicas MM, Cervini AB, Pierini AM. Poliarteritis nodosa cutánea postestreptocóccica: un simulador de la fiebre reumática. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2006;104:234–239. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozen S, Pistorio A, Iusan SM, Bakkaloglu A, Herlin T, Brik R, et al. EULAR/PRINTO/PRES criteria for Henoch-Schönlein purpura, childhood polyarteritis nodosa, childhood Wegener granulomatosis and childhood Takayasu arteritis: Ankara 2008. Part II: Final classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:798–806. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.116657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fink CW. The Role of the Streptococcus in post-streptococcal reactive arthitis and childhood polyarteritis nodosa. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1991;29:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringold S, Wallace CA. Evolution of paediatric-specific vasculitis classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:785–786. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozen S, Ruperto N, Dillon MJ, Bagga A, Barron K, Davin JC, et al. EULAR/PReS endorsed consensus criteria for the classification of childhood vasculitides. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:936–941. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.046300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawakami T. A Review of Pediatric Vasculitis with a Focus on Juvenile Polyarteritis Nodosa. Department of Dermatology, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, Kawasaki, Japan. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:389–398. doi: 10.2165/11599660-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss P. Pediatric Vasculitis. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59:407–423. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos F, Figueira R, Fonseca JE, Canhão H, Mouzinho A, Valente P, et al. Poliarterite Nodosa Cutânea Infantil Associada a Infecção Estreptocócica. Acta Reum Port. 2006;31:83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bont L, Brus F, Dijkman-Neerincx RH, Jansen TL, Meyer JW, Janssen M. The clinical spectrum of post-streptococcal syndromes with arthritis in children. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1998;16:750–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]