Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous environmental bacterium and a clinically significant opportunistic human pathogen. Central to the ability of P. aeruginosa to colonise both environmental and host niches is the acquisition of zinc. Here we show that P. aeruginosa PAO1 acquires zinc via an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) permease in which ZnuA is the high affinity, zinc-specific binding protein. Zinc uptake in Gram-negative organisms predominantly occurs via an ABC permease, and consistent with this expectation a P. aeruginosa ΔznuA mutant strain showed an ~60% reduction in cellular zinc accumulation, while other metal ions were essentially unaffected. Despite the major reduction in zinc accumulation, minimal phenotypic differences were observed between the wild-type and ΔznuA mutant strains. However, the effect of zinc limitation on the transcriptome of P. aeruginosa PAO1 revealed significant changes in gene expression that enable adaptation to low-zinc conditions. Genes significantly up-regulated included non-zinc-requiring paralogs of zinc-dependent proteins and a number of novel import pathways associated with zinc acquisition. Collectively, this study provides new insight into the acquisition of zinc by P. aeruginosa PAO1, revealing a hitherto unrecognized complexity in zinc homeostasis that enables the bacterium to survive under zinc limitation.

Zinc is the second most abundant first-row transition metal in biological organisms1. Approximately 6% of prokaryotic proteins are predicted to bind zinc2 and this can be attributed to the ability of the metal ion to serve in both structural and catalytic roles1,3. Although zinc lacks redox activity, due to its completely filled d-shell, it can still mediate significant toxicity in biological systems by inappropriately binding to the metal binding sites of proteins or DNA, thereby perturbing or inhibiting their function4,5. Consequently, efficient management and regulation of zinc homeostasis is a critical aspect of prokaryotic chemical biology.

Zinc, which occurs as the divalent cation Zn2+ in biological systems, is present at widely varying concentrations in the environment. The bioavailability of Zn2+ is dictated by a number of prevailing variables and, in soils and plants, Zn2+ content is highly dependent on both geological and meteorological contributions, typically occurring within a range between 15 and 200 mg Zn2+ per kg (dry weight)6,7. Significant variation in metal ion abundance also occurs in the context of host-pathogen interactions. Mammalian hosts, such as humans, employ nutritional immunity as a component of their innate defence, wherein they restrict the bioavailability of certain transition metal ions, by using chelating proteins, such as calprotectin and psoriasin, to hamper bacterial colonisation during the initial stages of infection8,9. At later stages of infection, transition metal ion fluxes, notably Zn2+ and copper, have been associated with the prosecution of metal-toxicity towards bacterial pathogens9. As both a ubiquitous environmental organism and a clinically significant opportunistic human pathogen, P. aeruginosa encounters widely varying levels of Zn2+ abundance depending on its niche. To date, there has been limited information regarding how the bacterium manages its cellular Zn2+ content in response to fluctuations in extracellular Zn2+ abundance.

Specific, high-affinity acquisition of Zn2+ was first demonstrated in E. coli and shown to occur via the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) permease, ZnuABC10. The Znu permease comprises the solute-binding protein (SBP) ZnuA, and an ABC transporter, which consists of ZnuB (the transmembrane protein) and ZnuC (the nucleotide-binding domain), in a ZnuAB2C2 organisation10. The SBP was shown to be Zn2+-specific and responsible for delivery of Zn2+ ions to the ZnuBC transporter, located in the cytoplasmic membrane. The Znu permease and its homologs are the most common Zn2+ uptake pathway in prokaryotes11,12,13,14. Loss of the Znu permease in many species, including E. coli, Salmonella Typhimurium and Yersinia pestis, typically results in a pronounced growth defect12,13. Zinc acquisition is controlled by metalloregulatory proteins, such as the Zn2+-uptake regulator (Zur), which is a Zn2+-specific regulatory protein, belonging to the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) family of transcriptional regulators15. In P. aeruginosa Zur (formerly Np20 and PA5499), was recently shown to be a Zn2+-responsive metalloregulatory protein that mediated the Zn2+-dependent repression of a putative znuABC permease16. Hence, in P. aeruginosa, as in many prokaryotes, Zn2+ appears to negatively regulate its own accumulation via transcriptional control over the Zn2+-import pathway genes.

Complementary to the Zur-dependent regulation of Zn2+ uptake, prokaryotic organisms also efflux Zn2+ ions to prevent Zn2+ overload. Efflux of cellular Zn2+ from prokaryotes can occur via a number of distinct transporters depending on the organism, and include resistance-nodulation division pumps (e.g. CzcCBA), cation diffusion facilitator transporters (e.g. ZitB and CzcD), and P-type ATPase transporters (e.g. ZntA)17,18,19,20. Expression of each of these efflux systems is tightly controlled by a cognate transcriptional regulator21,22,23. Collectively, studies of the Zn2+-uptake and -efflux pathways and their associated regulators have revealed that prokaryotic Zn2+ homeostasis involves acutely tight regulation and management of intracellular Zn2+ ions. Although the absolute intracellular accumulation of Zn2+ varies, depending on the organism24,25, studies of E. coli have indicated that the concentration of ‘free’ or labile Zn2+ present in the cytoplasm was extraordinarily low (in femtomolar range).

Bioinformatics analyses of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome identified three genes homologous to E. coli znuABC: PA5498 (znuA), PA5500 (znuB), and PA5501 (znuC), which have also been shown to be under the control of the Zur transcriptional regulator16,26. The putative znuA gene is present in a separate operon to the putative ABC transporter components (znuB and znuC), while zur is encoded immediately upstream of znuB and znuC, with the three genes forming an operon16. PA5502, which encodes a putative lipoprotein, is present following znuC, but this gene is transcribed independently of zur and znuBC, suggesting that it does not play a role in Zn2+ acquisition. Although P. aeruginosa mutant strains lacking znuA, znuB, or znuC were recently shown to have a modest reduction in the final biomass, when grown overnight in rich media treated with the divalent cation-chelating agent ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)16, direct evidence for their involvement in Zn2+-specific acquisition has been lacking. Hence, although studies of Zn2+ regulation in P. aeruginosa have implicated an ABC uptake system in Zn2+ uptake, its precise molecular role has not yet been elucidated16. Here, we report on the cellular accumulation of Zn2+ in P. aeruginosa PAO1, which represents ~10% of the total cellular transition metal content, the primary mechanisms of Zn2+ acquisition, and the impact of Zn2+ limitation upon transcriptional regulation and cellular physiology.

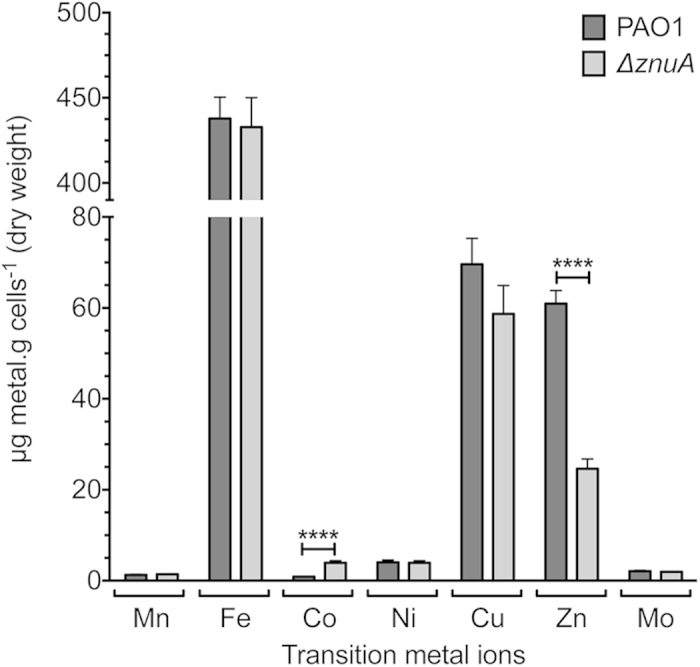

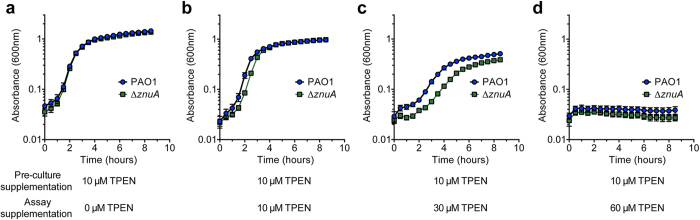

Results and Discussion

P. aeruginosa encodes a Zn2+-specific ABC permease

To directly assess the role of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 putative ZnuA protein in Zn2+ acquisition, we constructed a mutant strain lacking znuA (ΔznuA). Whole cell metal accumulation of wild-type P. aeruginosa and the ΔznuA strain was assessed in Chelex-100 treated, chemically-defined media (CDM) by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Metal accumulation analyses revealed a significant 59.6% decrease in cellular Zn2+ due to loss of the SBP (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1). Disruption of the Znu permease had no impact on the cellular accumulation of other transition metal ions apart from cobalt, which increased in cellular abundance (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1), suggesting that the P. aeruginosa Zn2+ regulatory and/or homeostatic mechanisms may also associated with cobalt homeostasis. Collectively, these data indicate that the P. aeruginosa znuA gene, and by extension the Znu permease, is associated with acquisition of Zn2+, while loss of znuA results in a significant disruption of cellular Zn2+ homeostasis. Due to the widespread utilization of zinc in cellular processes, it was anticipated that impairment of Zn2+ accumulation would result in perturbation of growth, as has been observed in other bacteria12,13. However, despite the highly restricted Zn2+ content (800 nM) of the CDM, the ΔznuA mutant strain did not exhibit a growth defect (Supplementary Fig. S1 online). Supplementation of the CDM with 10 μM of the preferential Zn2+ chelating agent N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN) in the pre-culture also failed to elicit a significant phenotypic impact on growth, despite being present at 10-fold in excess of the Zn2+ present in the media (Fig. 2a). Subsequent growth of the pre-treated PAO1 and ΔznuA mutant strains in the presence of 10 μM TPEN resulted in a slight growth perturbation of the mutant strain (Fig. 2b), an effect enhanced at 30 μM TPEN (Fig. 2c). Growth of both strains was inhibited in the presence of 60 μM TPEN (Fig. 2d). Therefore, as the growth defects were elicited in both the wild-type and mutant strain (Fig. 2c,d, and Supplementary Fig. S1 online) principally at higher TPEN concentrations, i.e. 30 μM and 60 μM relative to Zn2+, it cannot be excluded that the chelation of other essential transition row metal ions also contributed to these more pronounced phenotypic impacts. These observations would be consistent with the recent study of Ellison et al. (2013), wherein a slight growth perturbation was observed for a znuA mutant grown in undefined media with the broad acting divalent-chelating agent EDTA. In our study, the minor growth perturbation observed for the ΔznuA strain, relative to the wild-type, under Zn2+ limitation suggests that one or more high-affinity Zn2+ acquisition pathways may exist in P. aeruginosa that permit acquisition of Zn2+ ions, present at nanomolar concentrations, from the extracellular environment.

Figure 1. Whole cell metal accumulation analyses.

In vitro accumulation of metals by wild-type PAO1 (dark grey) and ΔznuA cultures (light grey) were assessed via growth in CDM. Metal content was expressed as μg of metal per gram of dry cells, as determined by ICP-MS. Data are the mean ± s.e.m., with duplicate readings taken from each biological replicate grown on three separate days. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, where ****represents P < 0.0001.

Figure 2. The effect of Zn2+ limitation on P. aeruginosa growth.

The growth phenotypes of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (blue) and the ΔznuA strain (green) were compared by absorbance at 600 nm. (a) CDM overnight seed cultures were supplemented with 10 μM TPEN, prior to growth analyses in unsupplemented CDM. (b) CDM overnight seed cultures were supplemented with 10 μM TPEN, prior to growth analyses in CDM supplemented with 10 μM TPEN. (c) CDM overnight seed cultures were supplemented with 10 μM TPEN, prior to growth analyses in CDM supplemented with 30 μM TPEN. (d) CDM overnight seed cultures were supplemented with 10 μM TPEN, prior to growth analyses in CDM supplemented with 60 μM TPEN. Cultures were grown as indicated and, in all experiments, data are the mean ± s.e.m., with n ≥ 3.

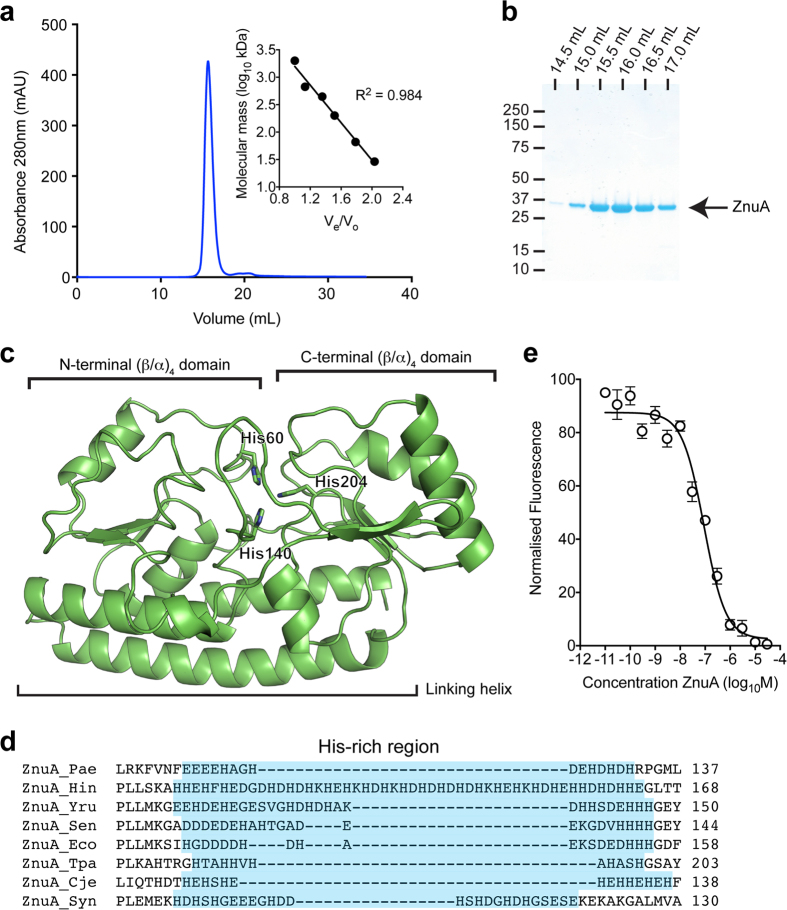

ZnuA is a high affinity Cluster A-I Zn2+-binding protein

To ascertain whether P. aeruginosa ZnuA is a high-affinity Zn2+-SBP, biochemical and biophysical characterisation was undertaken. Recombinant C-terminal dodecahistidine-tagged ZnuA was expressed without the putative Sec-type signal peptide and purified by immobilised metal affinity chromatography and gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (Fig. 3a,b). GPC indicated that recombinant ZnuA was isolated as a single monodisperse species with a relative molecular mass of 34.5 kDa, which matched closely with the predicted molecular mass (34.4 kDa) of monomeric dodecahistidine-tagged ZnuA. The dodecahistidine tag was cleaved from ZnuA prior to subsequent characterisation. Endogenous metals were removed by denaturation at pH 4.0 in the presence of 30 mM EDTA, prior to refolding by dialysis in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl. ICP-MS analysis of refolded tag-cleaved ZnuA found that it was metal-free (apo), containing less than 0.01 mol of metal ions per mol of protein. A thermostabilisation assay was employed to assess cation interaction with ZnuA (Table 1). Zinc induced the largest increase in ZnuA stability, consistent with the role of ZnuA in Zn2+ acquisition as indicated by whole cell ICP-MS. Intriguingly, cobalt induced the next largest increase in ZnuA thermostability. However, as cobalt accumulation in P. aeruginosa is an order of magnitude less than Zn2+, and increased rather than decreased in the ΔznuA strain, ZnuA does not appear to have a physiological role in cobalt uptake.

Figure 3. Bioinformatics and biochemical characterisation of ZnuA.

(a) Absorbance (280 nm) trace of ZnuA analysed by gel permeation chromatography. Inset represents linear regression of soluble molecular mass standards used to determine the apparent molecular mass of ZnuA. ZnuA was determined to be monomeric with a molecular mass of 34.5 kDa. (b) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE analysis of monomeric ZnuA (indicated by arrow) by comparison with soluble molecular mass standards. Fractions analysed were 0.5 mL, with elution volume at start of each fraction indicated above the lane. (c) Cartoon representation of the homology-based model of P. aeruginosa ZnuA showing a typical cluster A-I fold and the predicted Zn2+ binding residues. (d) Primary sequence alignment of P. aeruginosa ZnuA, and ZnuA orthologs from other bacterial species with the His-rich region indicated in blue. ZnuA proteins from: Pae, P. aeruginosa (GI:15600691); Hin, H. influenza (GI:491963406); Yru, Y. ruckeri (GI:490857750); Sen, S. enterica (GI:541470409); Eco, E. coli (GI:635897169); Tpa, T. palladium (GI:504108253); Cje, C. jejuni (GI:504330062); Syn, Synechocystis 6803 (GI:499174152). (e) Competitive binding experiment with apo-ZnuA using Mag-fura-2-Zn2+. The normalised fluorescence emission (520 nm) of Mag-fura-2 was monitored in response to the addition of increasing concentrations of apo-ZnuA. Data are the mean (±s.e.m.) for three independent experiments.

Table 1. Effect of first row transition metal ions on the melting temperature of apo-ZnuA.

| Sample | Tm (°C)a | ΔTm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| apo-ZnuA | 48.45 ± 1.25 | — |

| ZnuA-Mn2+ | 49.53 ± 1.65 | +1.08 |

| ZnuA-Fe2+ | 52.58 ± 3.32 | +4.14 |

| ZnuA-Fe3+ | 44.36 ± 3.00 | −4.09 |

| ZnuA-Co2+ | 58.46 ± 1.00 | +10.01 |

| ZnuA-Ni2+ | 51.88 ± 1.66 | +3.43 |

| ZnuA-Cu2+ | 52.81 ± 0.33 | +4.37 |

| ZnuA-Zn2+ | 61.41 ± 1.12 | +12.96 |

aValues shown represent the average and standard deviation from at least three independent measurements.

Primary sequence analysis of P. aeruginosa PAO1 ZnuA indicates that it belongs to the Cluster A-I (formerly cluster IX) subgroup of SBPs associated with ABC transporters (Supplementary Fig. S2 online)27. High-resolution structural analyses have shown that cluster A-I SBPs have a bi-lobed architecture, with the N- and C-terminal (β/α)4-domains linked by a long alpha-helix and the protein surface bisected by the cleft between the two lobes. In Zn2+-specific cluster A-I SBPs, Zn2+ is generally bound by three Nε2 atoms, contributed by conserved histidine residues, and an oxygen atom from a coordinating carboxylate residue or a water molecule within this cleft28,29,30. An energy-minimised homology model of ZnuA was generated based on a high-resolution crystal structure of ZnuA from E. coli (PDB 2OGW) (Fig. 3c). Primary sequence alignment and the structural prediction indicated that the high-affinity Zn2+-binding site, located in the interdomain cleft of P. aeruginosa ZnuA, would comprise His60, His140, and His204 (Nε2 contributing residues). The metal ion coordination modality observed in the E. coli ZnuA homolog (Glu77, His78, His161, and His225) is unlikely to occur in P. aeruginosa ZnuA due to the absence of an oxygen-contributing residue at the position proximal to the first His residue (His60) or elsewhere in the vicinity of the Zn2+ ion binding site29. Instead, the coordinating oxygen-ligand would mostly likely be a water molecule, as observed in the Synechocystis 6803 ZnuA homolog30. Similar to the high-resolution structures of other cluster A-I SBPs, the metal-binding site of ZnuA would be buried ~10–15 Å beneath the molecular surface of the protein5,29,30,31. In addition to the metal-coordinating residues, a disordered region of 15 acidic residues, which is similar to the His-rich region (or loop) of other Zn2+-specific SBPs, was also identified in the primary sequence of P. aeruginosa ZnuA (Fig. 3d). The length of this region has been observed to vary in Zn2+-specific SBPs from 12 residues (T. pallidum)32 to 50 residues (H. influenzae)33, but this region was not present in the homology model due to its absence from all high-resolution crystal structures.

Zinc-specific SBPs from Gram-negative organisms contain a single high affinity Zn2+-binding site. In addition, the His-rich loop has been reported to bind Zn2+, but with much lower affinity (~3–4 orders of magnitude lower). Here, ZnuA was analysed using a competitive Zn2+-binding assay with the Zn2+-responsive fluorophore Mag-Fura-2. A titration with increasing concentrations of ZnuA revealed a KD for Zn2+ of 22.6 ± 6.4 nM (Fig. 3e). This is consistent with the nanomolar affinity of other ZnuA homologs for Zn2+34,35,36. We then investigated the stoichiometry of Zn2+ binding by ZnuA. ICP-MS analysis of a ZnuA-Zn2+ equilibrium binding experiment showed that ZnuA bound 1.6 ± 0.1 mol Zn2+.mol protein−1. The stoichiometry indicated the presence of an additional Zn2+-binding site, consistent with observations from other Zn2+-specific SBPs from Gram-negative organisms, e.g. E. coli ZnuA (~1.85 mol Zn2+.mol protein−1)34 and H. influenzae Pzp1 (1.6–1.9 mol Zn2+.mol protein−1)33, which is likely due to the presence of the low-affinity (micromolar) His-rich Zn2+-binding region. It has been suggested that the role of the His-rich region is to aid in delivery of Zn2+ to the primary binding site of the SBP or in facilitating Zn2+ transfer to ZnuB 30. However, due to its highly disordered structure, conclusive evidence has remained elusive. Irrespective, the His-rich loop has a much lower (micromolar) affinity, with its precise role in ZnuA only poorly defined35. Indeed, the His-rich loop is not essential for the function of the high affinity Zn2+-binding site, although recent studies have indicated that this region may play a role in promoting Zn2+ interaction with ZnuA in order to aid in Zn2+ binding at the high-affinity site in vivo37. Taken together, these data show that P. aeruginosa ZnuA is a high-affinity Zn2+-specific cluster A-I SBP. Similar to other Gram-negative SBPs, P. aeruginosa ZnuA is competent for binding multiple Zn2+ atoms. Collectively, these analyses indicate that the Znu permease is a major Zn2+ acquisition pathway of P. aeruginosa.

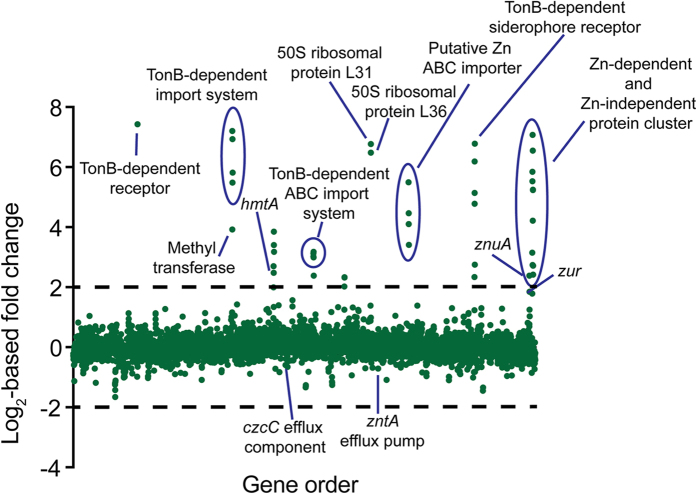

Zinc depletion results in transcriptional modulation

Bioinformatic studies have predicted Zn2+ to be utilised by approximately 6% of prokaryotic proteins2. Consequently, it was anticipated that the Zn2+ deficiency of the ΔznuA strain would be accompanied by a significant transcriptional response. To identify the pathways affected by Zn2+ depletion, the transcriptomes of wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 and the ΔznuA strain were analysed by RNA sequencing (Table 2 and Fig. 4). Overall 88 of the 5697 genes were up-regulated ≥2-fold, with 44 up-regulated ≥4-fold. Surprisingly, only 22 genes were down-regulated ≥2-fold in the ΔznuA strain. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis of several representative genes validated the RNA sequencing results (Supplementary Fig. S3 online).

Table 2. P. aeruginosa gene transcription under ΔznuA-induced Zn2+ depletion.

| Locus ID | Predicted functionsa | Foldchange | Zur bindingsite (E-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA0781 | TonB-dependent receptor (ZnuD) | 172.2 | 0.0012 |

| PA1921 | methyltransferase | 15.1 | 0.00027 |

| PA1922 | TonB-dependent receptor | 147.3 | 0.00027 |

| PA1923 | cobaltochelatase subunit (CobN) | 122.2 | |

| PA1924 | ExbD | 44.7 | |

| PA1925 | hypothetical | 56.4 | |

| PA2434 | hypothetical | 6.5 | 0.11 |

| PA2435 | P-type ATPase importer (HmtA) | 5.6 | |

| PA2437 | membrane protease subunit of HflC family | 14.4 | |

| PA2438 | HflC membrane protease subunit | 10.6 | |

| PA2439 | membrane protease subunit of HflK family | 9.0 | |

| PA2911 | TonB dependent receptor | 8.1 | 0.00027 |

| PA2912 | nucleotide binding domain of ABC transporter | 8.8 | |

| PA2913 | iron periplasmic binding protein | 9.1 | |

| PA2914 | transmembrane domain of Vitamin B12 ABC permease | 8.0 | |

| PA2915 | metallo β-lactamase | 5.2 | — |

| PA2916 | lysine transporter (LysE) | 4.2 | — |

| PA3282 | hypothetical | 4.1 | — |

| PA3283 | hypothetical | 5.0 | |

| PA3284 | hypothetical | 5.0 | |

| PA3600 | 50S ribosomal protein L36 | 89.2 | 0.0013 |

| PA3601 | 50S ribosomal protein L31 | 109.0 | |

| PA4063 | Zn2+ periplasmic binding protein | 45.1 | 0.0011 |

| PA4064 | ABC transporter nucleotide binding protein | 17.2 | |

| PA4065 | lipoprotein release ABC transporter permease | 22.1 | |

| PA4066 | lipoprotein | 10.6 | |

| PA4833 | hemolysin III family protein | 5.0 | — |

| PA4834 | putative membrane transporter | 27.4 | 0.0014 |

| PA4835 | hypothetical | 35.2 | |

| PA4836 | hypothetical | 72.9 | |

| PA4837 | TonB-dependent siderophore receptor | 110.0 | |

| PA4838 | hypothetical membrane protein | 6.7 | 0.0014 |

| PA5498 | Zn2+ ABC transporter SBP (ZnuA) | 5.2 | 0.0012 |

| PA5532 | cobalamin biosynthesis protein (CobW) | 8.9 | — |

| PA5534 | hypothetical | 57.5 | 0.00021 |

| PA5535 | cobalamin synthesis protein | 46.1 | |

| PA5536 | Zn2+-independent transcription regulator (DksA2) | 134.6 | |

| PA5537 | glutamine synthetase | 6.7 | 0.00021 |

| PA5538 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase (AmiA) | 18.6 | 0.00017 |

| PA5539 | GTP cyclohydrolase (FolE2) | 93.6 | 0.00017 |

| PA5540 | carbonate dehydratase | 37.6 | |

| PA5541 | dihydroorotase (PyrC2) | 37.9 | |

| PA5542 | β-lactamase | 6.6 | — |

| PA5543 | hypothetical | 5.4 | — |

aThe functional prediction was determined by BLAST searches (P value < 10−30).

Figure 4. Differential expression of genes in response to the Zn2+ depletion of the ΔznuA strain.

RNA sequencing of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and the isogenic ΔznuA deletion strain was used to determine relative gene expression (expressed as log2-fold change). Each green dot represents a gene, with each gene distributed on the x-axis in accordance with locus tag numbering for PAO1. Genes more highly expressed in the ΔznuA strain are present above the x-axis, with those below the x-axis expressed at a lower level in the ΔznuA strain. Genes of interest are annotated with their putative or characterised functions.

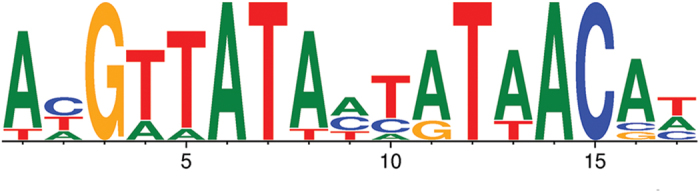

In order to examine the role of the P. aeruginosa Zur in modulating the transcriptional response to Zn2+ limitation, we examined the genome for the presence of putative Zur binding sites. Recently, the P. protegens Pf-5 Zur motif was determined38, providing a template from which a P. aeruginosa PAO1 optimized Zur binding motif could be generated. The P. protegens Pf-5 Zur motif was subjected to iterative refinement by only selecting putative sites in the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome that were positioned intergenically, up-regulated ≥2-fold as determined by our RNA-sequencing data, and possessing an E-value ≤ 0.002, until no new candidate sites were identified. On the basis of these parameters, a PAO1 Zur motif was generated from 9 Zur binding sites (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S1 online). Subsequent examination of the transcriptomic responses of P. aeruginosa to Zn2+ deficiency showed that Zur is the primary regulator of Zn2+ homeostasis in this bacterium, as all but 9 of the transcriptionally responsive genes up-regulated ≥4-fold possessed a Zur binding site (Table 2).

Figure 5. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 Zur motif.

The size of the nucleotide (T in red, A in green, C in blue and G in yellow) indicates its conservation across the 9 Zur binding site sequences listed in Supplementary Table S1 online. The 17 bp motif shows a palindrome with a central non-conserved nucleotide in position 9. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 Zur motif was created using WebLogo 3.066.

Zinc homeostatic mechanisms

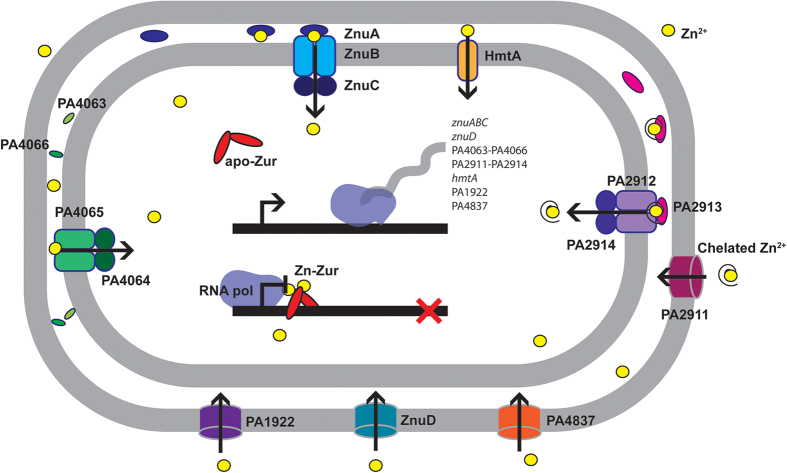

Although deletion of znuA reduced cellular Zn2+ abundance, the ΔznuA strain was capable of acquiring sufficient Zn2+ to facilitate a growth phenotype similar to that of the wild-type strain. Hence, given the restriction of Zn2+ abundance in the CDM to nanomolar concentrations, it is likely that P. aeruginosa PAO1 possesses one or more additional high affinity Zn2+ acquisition mechanisms to ensure the cellular Zn2+ requirement is met. Analysis of the RNA-sequencing data allowed identification of three putative transport systems, in addition to the ZnuABC permease, that may facilitate translocation of Zn2+ across the inner membrane into the cell: PA2911-PA2914, hmtA and PA4063-PA4066. Each of these putative transport systems was identified as being under the transcriptional control of Zur and was significantly up-regulated in the ΔznuA strain (Supplementary Fig. S4 online).

Primary sequence analyses predicted that PA2911-PA2914 encodes an iron ABC permease (PA2912-PA2914) that is co-transcribed with a putative TonB-dependent receptor (PA2911). However, studies of iron limitation in P. protegens indicated that the homologous cluster was not associated with iron recruitment39. Furthermore, the presence of a Zur site in the regulatory elements of the PA2911-PA2914 cluster (E-value = 0.00027; Table 2) is consistent with the observed transcriptional response to Zn2+ depletion. However, the mechanism by which the PA2911-PA2914 cluster may acquire Zn2+ is not immediately apparent, as primary sequence analysis of the putative PA2913 SBP component indicates that it does not belong to the cluster A-I subgroup of ABC permease cation-recruiting SBPs. Instead, PA2913 more closely resembles a cluster A-II SBP, suggesting that it may interact with a chelated form of Zn2+ (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). Although we have no direct evidence for a chelated-Zn2+ complex in P. aeruginosa, recently a Zn2+-chelating molecule known as yersiniabactin, was characterized in Yersinia pestis40. Yersiniabactin Zn2+ uptake was shown to be dependent upon the major facilitator family transporter, YbtX. Although a Zn2+-chelate ABC-dependent uptake system has not yet been identified, it is not inconceivable that PA2911, which shares homology with a TonB-dependent receptor, may function in concert with PA2912-PA2914 to facilitate transport of chelated Zn2+ from the extracellular environment to the cytoplasm. Of interest, PA2914 also shares homology with the transmembrane domain protein of the Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) ABC permease. Hence, the up-regulation of the PA2911-PA2914 system in response to Zn2+ depletion may enable the import of cobalt-containing cobalamin, possibly accounting for the increase in cellular cobalt levels observed in the ΔznuA strain (Fig. 1). Further studies of PA2911-PA2914 will be required to elucidate whether Zn2+ or cobalt could be acquired via this type of pathway.

A second putative ABC permease gene cluster (PA4063-PA4066) featuring a Zur site (E-value = 0.0011) was also up-regulated in response to Zn2+ limitation. By contrast with other ABC permeases, the individual putative SBP genes associated with this gene cluster, PA4063 and PA4066, are too small to form an SBP of sufficient size to stably interact with a ligand and the transmembrane domains of the ABC transporter. Furthermore, monomeric PA4066 has an insufficient number of histidine residues to coordinate Zn2+ ions, while PA4063 appears to have an abundance of histidine residues. Thus, it remains unclear how these proteins may contribute to Zn2+ homeostasis. Zinc-depletion was also associated with the up-regulation hmtA, an atypical P-type ATPase importer involved in Zn2+ and copper import (Supplementary Fig. S4 online)41. The hmtA-containing gene cluster (PA2434-PA2439) was also shown to feature a weak putative Zur binding site (E-value = 0.11). Collectively, these putative Zur-regulated transporters may aid in Zn2+ acquisition in the absence of the functional Znu permease, thereby minimizing the impact of Zn2+ depletion and the growth phenotype perturbation.

In addition to the transport systems identified in the inner membrane, four genes encoding putative TonB-dependent outer membrane proteins were found to be up-regulated in the ΔznuA strain (PA0781, PA1922, PA2911 and PA4837). The gene most highly up-regulated, as determined in our transcriptome study, was PA0781 (172-fold), which shares 27% identity with the TonB-dependent Zn2+-binding protein ZnuD from Neisseria meningiditis42. ZnuD facilitates Zn2+ recruitment to the periplasm under Zn2+-restricted conditions, thereby enabling subsequent import of Zn2+ to the cytoplasm42. PA2911 is associated with an ABC permease (PA2912-PA2914), discussed above, while the two remaining putative TonB-dependent receptors are also present within Zur-regulated gene clusters. The putative TonB-dependent receptor PA1922 is located within an operon that contains a cobN-like gene (PA1923), which encodes a putative cobaltochelatase involved in cobalamin biosynthesis. The up-regulation of this operon may account for the increase in cellular cobalt levels observed in the ΔznuA mutant (Fig. 1). Alternatively, Zn2+ may substitute for cobalt in PA192343, although the precise role of this operon in metal ion homeostasis remains to be determined. The TonB-dependent receptor encoded by PA4837 is located in an operon with a putative nicotianamine synthase (PA4836). Although the function of nicotianamine in bacteria has not been explored, these secondary metabolites have previously been shown to be involved in Zn2+ homeostasis in plant and yeast cells44. It is tempting to speculate that the putative drug/metabolite exporter encoded by PA4834 is involved in the transport of nicotianamine to the periplasm of P. aeruginosa. However, the exact interaction of the TonB-dependent receptor encoded by PA4837 and nicotianamine remains unknown. Consequently, further studies are required to ascertain the role of these pathways and whether they contribute to Zn2+ and/or cobalt acquisition.

TonB-dependent outer membrane receptors rely on TonB, ExbB and ExbD to energize transport. P. aeruginosa PAO1 features two identified exbB and exbD genes (exbB1 and exbB2, and exbD1 and exbD2) and three tonB genes (tonB1, tonB2 and tonB3), but these were not significantly up-regulated under Zn2+ restriction. However, PA1924 encoding a putative ExbD homolog was up-regulated by ~44-fold under Zn2+ deficiency. Co-transcribed with the putative TonB-dependent receptor PA1922, PA1924 may serve as a component of the TonB uptake pathway in P. aeruginosa.

Comparative analyses of the Zn2+ acquisition mechanisms described above revealed that, in general, these proteins are highly conserved within the species (data not shown). Major sequence variation was only observed within PA4063, specifically within the second of the two histidine rich regions of the protein, wherein the number of histidine residues varied between 3 and 10 across the species. Since PA4063 may play a role in delivery of Zn2+ to the ABC-transporter encoded by PA4064-PA4065, the substantial differences observed within the histidine rich region could have a profound impact on the efficiency of Zn2+ uptake via this system in different P. aeruginosa strains.

Zinc limitation and transcriptional regulation of ribosomal proteins

Prokaryotic ribosomal proteins commonly occur in two forms, which either bind metals ions such as Zn2+ (C+ isoform), or lack the ability to interact with metal ions (C− isoform) due to the absence of the metal-binding residues45. It is the ability of the C− form to substitute for the Zn2+-dependent C+ form that enables ribosomal function to be maintained under Zn2+ limitation46. This has led to the suggestion that ribosomal proteins may act as a Zn2+ reservoir and allow Zn2+ redeployment during periods of Zn2+ depletion46. Similar to P. protogens Pf-5, P. aeruginosa harbours genes for both the C+ and C− paralogs of the 50s ribosomal proteins L36 and L3138,45. The C+ copies of L36 and L31 (rpmJ/PA4242 and rpmE/PA5049, respectively) each feature canonical Zn2+-binding resides (either His or Cys). The C− isoforms L36 and L31 (PA3600 and PA3601, respectively) are predicted to be co-transcribed under the control of an adjacent putative Zur site (P = 0.0013), and lack almost all of the Zn2+-binding residues. Consistent with these analyses the C− (Zn2+-independent) L36 (PA3600) and L31 (PA3601) isoforms were highly up-regulated (89.2- and 109-fold, respectively) under Zn2+-depleted conditions. This implicates redeployment of Zn2+ via the switch to C− ribosomal proteins as a potential strategy for managing Zn2+ depletion.

Up-regulation of genes encoding Zn2+-independent paralogs and Zn2+-dependent proteins

The importance of Zn2+ as a structural and catalytic cofactor in a range of proteins necessitates an efficient strategy on behalf of the bacterium to adapt to Zn2+ limitation. This is presumed to involve a combination of substitution by Zn2+-independent paralogs and redeployment of Zn2+ to proteins that have an absolute requirement for Zn2+. We identified a Zur-regulated cluster of genes (PA5532-PA5541), which encodes a number of genes up-regulated in response to Zn2+ depletion. A similar, yet distinct cluster was recently identified in a study examining Zn2+ depletion in P. protegens Pf-538. The Pf-5 cluster includes genes encoding an ABC import system (PFL_6178-PFL_6180) and two putative enzymes (PFL_6181 and PFL_6184). By contrast, the up-regulated genes of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 cluster include DksA2 (PA5536), the Zn2+-independent global transcriptional regulator that substitutes for the Zn2+-dependent DksA (PA4723) under Zn2+-limiting conditions47,48. DksA and DksA2 have major roles in regulating the starvation response of P. aeruginosa47,48. In addition, other up-regulated genes encoding Zn2+-independent paralogs include pyrC2 (PA5541), a dihydroorotase involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis49, a putative γ-carbonic dehydratase (PA5540), responsible for the conversion of carbon dioxide to bicarbonate50 and folE2 (PA5539). Up-regulated 93.6-fold and featuring a putative Zur binding site (E-value = 0.00017), folE2 is a putative Zn2+-independent GTP cyclohydrolase. The Zn2+-dependent FolE catalyses the first step of the de novo tetrahydrofolate (THF) biosynthetic pathway as well as the production of modified ribonucleosides found in tRNA molecules51, with a similar role predicted for FolE2. In contrast, the PA5532-PA5541 cluster also includes AmiA (PA5538), an N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase involved in membrane remodelling that has a strict requirement for Zn2+ 52. Two of the other genes up-regulated in this cluster, PA5532 and PA5535, belong to the COG0523 family and encode proteins with putative roles in cobalamin biosynthesis. However, approximately 30% of COG0523 family genes are predicted to be involved in Zn2+ homeostasis rather than cobalamin biosynthesis, while ~8% are directly Zur-regulated43. Although the precise role of these genes remains unclear, it is highly probable that they serve in facilitating cation homeostasis, particularly under Zn2+ restriction43.

Down-regulation of genes in response to Zn2+ depletion

Intriguingly, only a small proportion of genes were down-regulated by ≥2-fold in response to Zn2+ depletion and the majority of these encode tRNAs (38%). The nitrite reductase cluster (nirCFGHJL) showed a ≥2-fold reduction in transcription, although as none of the proteins involved in nitrate reduction directly utilize Zn2+, the underlying basis for this is unclear. The Zn2+ efflux pathways were only minimally down-regulated in the ΔznuA strain, with PA2522 (czcC) down-regulated 1.3-fold, and the E. coli zntA homolog, PA3690, down-regulated 1.6-fold. This indicates very limited Zn2+ efflux was required by the wild-type PAO1 strain in the CDM media used, with intracellular Zn2+ concentrations attributable to high affinity uptake pathways.

Conclusions

In environments of changing Zn2+ abundance, efficient acquisition and efflux mechanisms are crucial for maintaining cellular Zn2+ homeostasis. Similar to other prokaryotes, the Znu permease is a high-affinity Zn2+ acquisition pathway in P. aeruginosa PAO1, and the biochemical and biophysical properties of ZnuA are consistent with this role. Although disruption of the Znu permease resulted in significant impairment in cellular Zn2+ accumulation, this was not observed to elicit a major perturbation of growth. The global impact of Zn2+ limitation on P. aeruginosa PAO1 was revealed by the role of Zur in the regulation of genes associated with cellular Zn2+ homeostasis. Zur binding sites were identified adjacent to 79.5% (35 of 44) of the genes observed to be up-regulated by more than 4-fold in response to Zn2+ depletion. However, not all genes differentially regulated in response to Zn2+ depletion were located downstream of putative Zur binding sites, suggesting other regulatory processes also contribute to management of cellular stress under conditions of Zn2+ depletion. Transcriptome analyses showed that under Zn2+ limitation, P. aeruginosa PAO1 up-regulated a number of previously unidentified putative metal ion import pathways while also inducing the expression of Zn2+-independent paralogs of Zn2+-dependent proteins, such as the ribosomal proteins L31 and L36, PyrC2 and DksA2. In parallel, genes encoding proteins that have been reported to be crucially dependent on Zn2+ were also up-regulated. Taken together, these data implicate Zur in presiding over the cellular balance between Zn2+ conservation and utilization. In this way, Zur regulates the induction of Zn2+-dependent and -independent proteins, thereby controlling the magnitude of competition for the cellular Zn2+ pool and ensuring essential protein functions are maintained. Collectively, this work highlights the dynamic nature of P. aeruginosa Zn2+ acquisition, and the concerted cellular response to manage cellular Zn2+ utilization upon Zn2+ depletion (summarized in Fig. 6). Overall, this study provides new insights into the mechanisms and pathways utilized by P. aeruginosa to survive and promulgate in environments of varying Zn2+ abundance, with the findings widely applicable to other prokaryotic organisms.

Figure 6. Proposed model of Zn2+ acquisition in P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Schematic representation of the Zn2+ acquisition pathways of P. aeruginosa PAO1 based on transcriptomic and biochemical analyses. Under Zn2+-replete conditions, dimeric Zur, the primary Zn2+-responsive regulator, binds Zn2+, thereby repressing transcription of the Zn2+ import pathways. Zinc limitation facilitates the dissociation of Zn2+ from Zur, thereby permitting de-repression of the Zn2+ uptake pathway genes. Zinc entry into the periplasm occurs via four TonB-dependent outer membrane proteins: ZnuD (PA0781), PA2911, PA1922, and PA4837. Within the periplasm, Zn2+-specific SBPs (ZnuA, PA2913, PA4063 and PA4066) likely bind Zn2+, either as the free ion or chelated Zn2+, and deliver it to a cognate ABC import system (ZnuBC, PA2912/PA2914 and PA4064/PA4065), which facilitates vectorial transport to the cytosol. In addition, HmtA, a P-type ATPase is also able to import periplasmic Zn2+ ions into the cytoplasm.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains, media and growth

The wild-type P. aeruginosa strain used in this study was PAO1, with the ΔznuA deletion mutant made using PAO1 according to Choi and Schweizer53 using primers listed in Supplementary Table S2 online. P. aeruginosa was grown in a semi-synthetic cation-defined media (CDM) containing 8.45 mM Na2HPO4, 4.41 mM KH2PO4, 1.71 mM NaCl and 3.74 mM NH4Cl, supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (Difco) and vitamins (0.2 μM biotin, 0.4 μM nicotinic acid, 0.24 μM pyridoxine-HCl, 0.15 μM thiamine-HCl, 66.4 μM riboflavin-HCl, and 0.63 μM calcium pathothenate) and Chelex-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) treated. CaCl2 and MgSO4 were subsequently added to 0.1 mM and 2 mM, respectively. Metal concentrations of the CDM were ascertained by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) with Zn2+ present at 800 nM. For routine bacterial growth, media was inoculated to OD600 of 0.05 using overnight culture. Cells were grown to an OD600 of 0.6 on an Innova 40R shaking incubator (Eppendorf) at 240 rpm, 37 °C. Whole cell metal accumulation was performed as previously described5 and analysed by ICP-MS on an Agilent 7500cx ICP-MS (Adelaide Microscopy, University of Adelaide).

Expression and purification of ZnuA

Recombinant ZnuA was generated by PCR amplification of P. aeruginosa PAO1 znuA using ligation-independent cloning and primers listed in Supplementary Table S2 online, to insert the gene into a C-terminal dodecahistidine tag-containing vector, pCAMcLIC01, to generate pCAMcLIC01-ZnuA. Recombinant ZnuA expression and purification was performed essentially as described previously54. Recombinant ZnuA had the dodecahistidine tag removed by 1 h enzymatic digestion at a ratio of 1:25 by the histidine-tagged 3C human rhinovirus protease, at a cleavage site introduced between ZnuA and the tag. The protein was then reverse-purified on a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) with the cleaved protein unable to bind to the column. Removal of the dodecahistidine tag was confirmed by the observed reduction in molecular mass on a 4–12% SDS-PAGE gel and confirmed by immunoblotting. Demetallated (apo) ZnuA was prepared by dialyzing the protein (10 ml) in a 20 kDa MWCO membrane (Pierce) against 4 L of sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0, with 20 mM EDTA, at 25 °C. The sample was then dialyzed against 4 L of 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 100 mM NaCl, at 4 °C. The sample was then recovered and centrifuged at 120,000 × g for 10 min to remove any insoluble material. Metal content analysis was performed by ICP-MS5.

Homology modelling and structural analyses

The homology model of P. aeruginosa ZnuA was constructed using the SwissModel webserver55, with ZnuA (PDB ID: 2OGW) as a template. The resulting model of ZnuA was energy-minimized in SwissPDBViewer56 using the inbuilt 43B1 vacuum forcefield57. Structure-based sequence alignment was performed with 3D-Coffee58 as described in Plumptre, et al.36.

Biophysical analyses of ZnuA

Zinc loading assays were performed on 3C cleaved ZnuA (20 μM) as previously described31. The supernatant was then analysed by ICP-MS and the protein-to-metal ratio determined. Determination of the KD for ZnuA with Zn2+ was performed by means of a competition assay using apo-ZnuA and the Zn2+-fluorophore Mag-Fura-2 (Life Technologies) as previously described36. Competition by ZnuA for Zn2+ binding was assessed by monitoring the increase in the fluorescence of 150 nM Mag-Fura-2-Zn2+ in response to increasing apo-ZnuA concentrations and analysed using log10[inhibitor] versus response model, with the experimentally derived KD for Mag-Fura-2 (22.6 ± 6.4 nM, with Zn2+, n = 8) in Graphpad Prism to determine the KD value for Zn2+ binding by ZnuA. The thermal shift assays were performed essentially as described previously5. Briefly, 10 μM of protein in 100 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 5 × SYPRO Orange (Life Technologies) was incubated in the presence of 1 mM metal ion and then analysed on a Roche LC480 Real-Time Cycler (Roche). The fluorescence data were collected by excitation at 470 nm and emission at 570 nm. After subtraction of the background fluorescence from the buffer, the first derivative of the fluorescence data was determined and analysed using Graphpad Prism to determine the inflection point of the melting transition (Tm). Data from at least three independent experiments were used to determine the mean Tm (±s.e.m.) of wild-type ZnuA.

Zur binding site identification

The P. aeruginosa Zur binding motif was determined as described previously59. In brief, the sequences of the P. protegens Pf-5 Zur motif38 were used to generate a P. aeruginosa PAO1 optimized Zur binding site motif. The sequences were aligned using ClustalW260 and a subsequent weight matrix was generated using HMMER 2.0 as an integral tool of UGENE61. Iterative refinement of the PAO1 Zur binding motif was performed based on genomic positioning, E-value (≤0.002) and up-regulation of the downstream gene (≥2-fold). The resulting sequences from which the Zur binding motif has been generated have been listed in Supplementary Table S1 online.

RNA isolation

Cells were grown aerobically to OD600 of 0.6 as detailed above, then 5 mL culture was harvested at 7000 × g, for 8 min, 4 °C and lysed in Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, USA) and chloroform. Following phase separation by centrifugation, RNA was isolated from the aqueous phase using a PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies), with a 30 min on-column DNaseI treatment with 2.7 U DNaseI. DNaseI treatment was performed on 2 μg total RNA using 50 units of recombinant RNase-free DNaseI (Roche) in a 50 μL reaction at 37 °C for 30 min, prior to inactivation of the enzyme by the addition of ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA, pH 8.0) to a final concentration of 2 mM, and incubation at 65 °C for 10 min. Samples were analysed for purity and integrity using a RNA 6000 Nano Assay on a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) according to the manufacturers protocol and stored at −80 °C until required.

qRT-PCR

For transcriptional analysis qRT-PCR was performed using a two-step method as previously described54. Briefly, cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers (Sigma-Aldrich) and Moloney murine leukaemia virus RNaseH minus point mutant (M-MLV, RNaseH minus) reverse transcriptase (Promega), as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 (Roche) using DyNAmo ColorFlash SYBR Green qPCR mix (ThermoFisher Scientific). Oligonucleotides used in this study were designed using Primer3 integrated within UGENE v1.11.4 (Unipro)61 and are listed in Supplementary Table S2 online. The constitutively expressed sigma factor gene rpoD (PA0576) was used as a control to normalize gene expression, with the data representing biological triplicates.

RNA sequencing

RNA isolated from biological triplicates of wild-type PAO1 and ΔznuA strains was pooled and submitted to the Adelaide Microarray Centre (University of Adelaide) for sequencing. Briefly, the Epicentre Bacterial Ribozero Kit (Illumina) was used to reduce the ribosomal RNA content of the total RNA pool, followed by use of the Ultra Directional RNA kit (New England Biolabs) to generate the barcoded libraries. Prepared libraries were then sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq2500 with Version 3 SBS reagents and 2 × 100 bp paired-end chemistry. Reads were aligned to the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome (GenBank accession number AE004091.2)26 using BOWTIE2 version 2.2.362. Counts for each gene were obtained with the aid of SAMtools (v 0.1.18)63 and BEDtools64 and differential gene expression was examined using DESeq65; the data has been submitted to GEO (accession number GSE60177).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Pederick, V. G. et al. ZnuA and zinc homeostasis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 5, 13139; doi: 10.1038/srep13139 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) grant DP120103957 to C.A.M. and J.C.P., and the National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project grants 1022240 and 1080784 to C.A.M. and Program grants 565526 and 1071659 to J.C.P, and the Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation grant 13661 to V.G.P. J.C.P. is a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow (1043070) and V.G.P. is supported by an Australian Cystic Fibrosis Research Trust scholarship. We thank Prof. H. Schweizer for providing the pEX18ApGW and pFLP2 plasmids, and Dr C. Adolphe and Prof. A.G. McEwan for discussions.

Footnotes

Author Contributions V.G.P., B.A.E. and C.A.M. designed the experiments. V.G.P., B.A.E., M.P.W., S.L.B., L.J.M. and C.A.M. performed the experiments and analysed the data. V.G.P., B.A.E., J.C.P. and C.A.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Hantke K. Bacterial zinc uptake and regulators. Curr Opin Microbiol 8, 196–202 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreini C., Banci L., Bertini I. & Rosato A. Zinc through the three domains of life. J Proteome Res 5, 3173–3178 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreini C., Bertini I., Cavallaro G., Holliday G. L. & Thornton J. M. Metal ions in biological catalysis: from enzyme databases to general principles. J Biol Inorg Chem 13, 1205–1218 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruins M. R., Kapil S. & Oehme F. W. Microbial resistance to metals in the environment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 45, 198–207 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt C. A. et al. A molecular mechanism for bacterial susceptibility to zinc. PLoS Pathog 7, e1002357 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepp N. W. Effect of Heavy Metal Pollution on Plants: Metals in the environment. (Applied Science Publishers, 1981). [Google Scholar]

- Markert B. A. Instrumental element and multi-element analysis of plant samples: methods and applications. (John Wiley, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Hood M. I. & Skaar E. P. Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen-host interface. Nat Rev Microbiol 10, 525–537 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerasi M., Ammendola S. & Battistoni A. Competition for zinc binding in the host-pathogen interaction. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3, 108 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzer S. I. & Hantke K. The ZnuABC high-affinity zinc uptake system and its regulator Zur in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 28, 1199–1210 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campoy S. et al. Role of the high-affinity zinc uptake znuABC system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence. Infect Immun 70, 4721–4725 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers D. C. et al. Znu is the predominant zinc importer in Yersinia pestis during in vitro growth but is not essential for virulence. Infect Immun 78, 5163–5177 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. A. et al. Identification of the znuA-encoded periplasmic zinc transport protein of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun 67, 5060–5068 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis V. G., Ween M. P. & McDevitt C. A. The role of ATP-binding cassette transporters in bacterial pathogenicity. Protoplasma 249, 919–942 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patzer S. I. & Hantke K. The zinc-responsive regulator Zur and its control of the znu gene cluster encoding the ZnuABC zinc uptake system in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 275, 24321–24332 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison M. L., Farrow J. M. 3rd, Parrish W., Danell A. S. & Pesci E. C. The transcriptional regulator Np20 is the zinc uptake regulator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS One 8, e75389 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver S. Bacterial resistances to toxic metal ions—a review. Gene 179, 9–19 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legatzki A., Grass G., Anton A., Rensing C. & Nies D. H. Interplay of the Czc system and two P-type ATPases in conferring metal resistance to Ralstonia metallidurans. J Bacteriol 185, 4354–4361 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guffanti A. A., Wei Y., Rood S. V. & Krulwich T. A. An antiport mechanism for a member of the cation diffusion facilitator family: divalent cations efflux in exchange for K+ and H+. Mol Microbiol 45, 145–153 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rensing C., Mitra B. & Rosen B. P. The zntA gene of Escherichia coli encodes a Zn(II)-translocating P-type ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 14326–14331 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman T. G., van der Kooi-Pol M. M., Bijlsma J. J. & Kuipers O. P. The novel transcriptional regulator SczA mediates protection against Zn2+ stress by activation of the Zn2+-resistance gene czcD in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 65, 1049–1063 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. K. et al. ZntR is an autoregulatory protein and negatively regulates the chromosomal zinc resistance operon znt of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 33, 200–207 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hosteen O. & Fierke C. A. ZntR-mediated transcription of zntA responds to nanomolar intracellular free zinc. J Inorg Biochem 111, 173–181 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg S. L. et al. Dysregulation of transition metal ion homeostasis is the molecular basis for cadmium toxicity in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nat Commun 6, 6418 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten C. E. & O'Halloran T. V. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science 292, 2488–2492 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover C. K. et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406, 959–964 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsson R. P., Smits S. H., Schmitt L., Slotboom D. J. & Poolman B. A structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett 584, 2606–2617 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couñago R. M., McDevitt C. A., Ween M. P. & Kobe B. Prokaryotic substrate-binding proteins as targets for antimicrobial therapies. Curr Drug Targets 13, 1400–1410 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. & Jogl G. Crystal structure of the zinc-binding transport protein ZnuA from Escherichia coli reveals an unexpected variation in metal coordination. J Mol Biol 368, 1358–1366 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Wei B., Bhattacharyya-Pakrasi M., Pakrasi H. B. & Smith T. J. Structural determinants of metal specificity in the zinc transport protein ZnuA from Synechocystis 6803. J Mol Biol 333, 1061–1069 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couñago R. M. et al. Imperfect coordination chemistry facilitates metal ion release in the Psa permease. Nat Chem Biol 10, 35–41 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers D. C. et al. The general transition metal (Tro) and Zn2+ (Znu) transporters in Treponema pallidum: analysis of metal specificities and expression profiles. Mol Microbiol 65, 137–152 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D., Boyd B. & Lingwood C. A. Identification of the key protein for zinc uptake in Hemophilus influenzae. J Biol Chem 272, 29033–29038 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatsunyk L. A. et al. Structure and metal binding properties of ZnuA, a periplasmic zinc transporter from Escherichia coli. J Biol Inorg Chem 13, 271–288 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei B., Randich A. M., Bhattacharyya-Pakrasi M., Pakrasi H. B. & Smith T. J. Possible regulatory role for the histidine-rich loop in the zinc transport protein, ZnuA. Biochemistry 46, 8734–8743 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumptre C. D. et al. AdcA and AdcAII employ distinct zinc acquisition mechanisms and contribute additively to zinc homeostasis in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol 91, 834–851 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbianelli R. et al. Role of ZnuABC and ZinT in Escherichia coli O157:H7 zinc acquisition and interaction with epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol 11, 36 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. K., Hassan K. A., Penesyan A., Loper J. E. & Paulsen I. T. The effect of zinc limitation on the transcriptome of Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5. Environ Microbiol 15, 702–715 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. K., Hassan K. A., Tetu S. G., Loper J. E. & Paulsen I. T. The effect of iron limitation on the transcriptome and proteome of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. PLoS One 7, e39139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrov A. G. et al. The Yersinia pestis siderophore, yersiniabactin, and the ZnuABC system both contribute to zinc acquisition and the development of lethal septicaemic plague in mice. Mol Microbiol 93, 759–775 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinson O., Lee A. T. & Rees D. C. A P-type ATPase importer that discriminates between essential and toxic transition metals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 4677–4682 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork M. et al. An outer membrane receptor of Neisseria meningitidis involved in zinc acquisition with vaccine potential. PLoS Pathog 6, e1000969 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas C. E. et al. A subset of the diverse COG0523 family of putative metal chaperones is linked to zinc homeostasis in all kingdoms of life. BMC Genomics 10, 470 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S., Deinlein U., Ahmadi H., Horeth S. & Uraguchi S. Nicotianamine is a major player in plant Zn homeostasis. Biometals 26, 623–632 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova K. S., Ponomarev V. A. & Koonin E. V. Two C or not two C: recurrent disruption of Zn-ribbons, gene duplication, lineage-specific gene loss, and horizontal gene transfer in evolution of bacterial ribosomal proteins. Genome Biology 2, research0033.0031 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S. E. & Helmann J. D. Contributions of Zur-controlled ribosomal proteins to growth under zinc starvation conditions. J Bacteriol 191, 6116–6122 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaby-Haas C. E., Furman R., Rodionov D. A., Artsimovitch I. & de Crecy-Lagard V. Role of a Zn-independent DksA in Zn homeostasis and stringent response. Mol Microbiol 79, 700–715 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perron K., Comte R. & van Delden C. DksA represses ribosomal gene transcription in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by interacting with RNA polymerase on ribosomal promoters. Mol Microbiol 56, 1087–1102 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brichta D. M., Azad K. N., Ralli P. & O'Donovan G. A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa dihydroorotases: a tale of three pyrCs. Arch Microbiol 182, 7–17 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capasso C. & Supuran C. T. An overview of the alpha-, beta- and gamma-carbonic anhydrases from Bacteria: can bacterial carbonic anhydrases shed new light on evolution of bacteria? J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 0, 1–8 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran B. et al. Zinc-independent folate biosynthesis: genetic, biochemical, and structural investigations reveal new metal dependence for GTP cyclohydrolase IB. J Bacteriol 191, 6936–6949 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidrich C. et al. Involvement of N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanine amidases in cell separation and antibiotic-induced autolysis of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 41, 167–178 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K. H. & Schweizer H. P. An improved method for rapid generation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa deletion mutants. BMC Microbiol 5, 30 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederick V. G. et al. Acquisition and role of molybdate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl Environ Microbiol 80, 6843–6852 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N. & Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL: An automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res 31, 3381–3385 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N. & Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gunsteren W. F. et al. Biomolecular Simulation: The GROMOS96 Manual and User Guide. (Vdf Hochschulverlag AG an der ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Armougom F. et al. Expresso: automatic incorporation of structural information in multiple sequence alignments using 3D-Coffee. Nucleic Acids Res 34, W604–608 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijkelkamp B. A., Hassan K. A., Paulsen I. T. & Brown M. H. Investigation of the human pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii under iron limiting conditions. BMC Genomics 12, 126 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A., Brown M., Mian I. S., Sjolander K. & Haussler D. Hidden Markov models in computational biology. Applications to protein modeling. J Mol Biol 235, 1501–1531 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonechnikov K., Golosova O., Fursov M. & team, U. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 28, 1166–1167 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B. & Salzberg S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan A. R. & Hall I. M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 26, 841–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S. & Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biology 11, R106 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M. & Brenner S. E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14, 1188–1190 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.