Abstract

Grain hardness is an important quality trait that influences product development in wheat. This trait is governed by variation in puroindoline proteins (PINA and PINB). Our study evaluated 551 Indian wheat germplasm lines for diversity in Pina and Pinb genes. Eighty-two lines were shortlisted for full length sequencing and grain hardness studies. Sequencing studies identified six unknown alleles: two for the Pina gene and four for the Pinb gene. Five of them were novel with non-synonymous changes in the corresponding amino acid sequences. Identified mutations in the deduced mature proteins and their pre- and pro-peptides influenced the hardness characteristics of the grain. We classified these 82 varieties into different hardness categories with reference to international and Indian systems of classification. The majority of Indian wheat varieties were categorized as hard. This study revealed that unexplored Indian wheat germplasm can be a good source of genetic variability for both Pina and Pinb genes, helping in marker-assisted breeding and in obtaining wheat with different textural properties.

Keywords: puroindolines, kernel texture, Ha (hardness) locus, hardness index, allele

Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most important food crops in the world. In the grain market, wheat is classified based on its hardness. Grain hardness refers to the texture of the kernel and has two main classes, hard and soft. The differences in grain texture are due to the expression of two major genes, puroindoline a (Pina) and puroindoline b (Pinb), located at the hardness locus (Ha) on the short arm of chromosome 5D (Baker 1977, Law et al. 1978, Symes 1965). In addition, minor loci other than the Ha may also be involved in modifying grain hardness. For example, QTLs associated with grain hardness of wheat are located on different chromosomes: 1A, 2A, 5A, 7A, 2B, 6B, 7B, 2D, 6D, and 7D (Galande et al. 2001, Geng et al. 2012, Perretant et al. 2000, Sourdille et al. 1996, Tsilo et al. 2011, Turner et al. 2004).

Ha controls the expression of friabilins having two major proteins, puroindoline A (PINA) and puroindoline B (PINB), and one minor protein, grain softness protein (GSP-1, Greenwell and Schofield 1986). Puroindoline proteins have structural similarity with wheat non-specific lipid transfer proteins (ns-LTPs) (Gautier et al. 1994) and dicot 2S storage proteins (Véronique et al. 2011). These unique 15 KDa proteins have a tryptophan rich domain, backbone of 10 cysteine residues, and high affinity for binding with lipids (Dubreil et al. 1997, Morris 2002). The tryptophan rich domain forms a looped structure at the exterior of the protein (Kooijman et al. 1997) and is directly associated with the starch granule surface (Wall et al. 2011). Minor components of friabilins, i.e., GSP-1, are structurally similar to PINs, but do not interact with lipids due to specific post-translational modification (Khalil et al. 2013).

Puroindoline gene expression in its wild-type state (Pina-D1a/Pinb-D1a) is necessary for soft texture wheat (Morris 2002). When either of the puroindoline proteins is absent or mutated, the resulting texture will be hard. Several mutations which result in hard grain texture have been reported. Pina null allele (Pina-D1b), i.e., complete absence of genes, was the first mutation to be reported in Pina (Giroux and Morris 1998). Non-functional Pinb allele (Pinb-D1b) resulting from single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), which changes amino acid glycine to serine at position 46 of the protein (Gly46Ser), was the first mutation reported in Pinb (Giroux and Morris 1997). Pina-D1b results in a slightly harder phenotype than Pinb-D1b (Chen et al. 2012, Morris 2002). In the Pina gene, other SNPs with corresponding amino acid change, without amino acid change (synonymous mutation = sm), i.e. Pina-D1c (Arg58Gln), Pina-D1g (sm), Pina-D1m (Pro35Ser), Pina-D1n (Trp43Stop) (Chen et al. 2006, Massa et al. 2004), and Pina-D1t (Trp41Stop) (Ramalingam et al. 2012), with two SNPs, i.e., Pina-D1d (Arg58Gln + sm), Pina-D1e (Arg58Gln + sm), Pina-D1h (Arg58Gln + sm), Pina-D1i (Arg58Glu + Arg21Ser), Pina-D1o (Arg58Gln + sm), and Pina-D1q (Chang et al. 2006, Gedye et al. 2004, Massa et al. 2004), with three SNPs, with frame shifts, with multiple deletions, i.e., Pina-D1f, Pina-D1j, Pina-D1k, Pina-D1l, and Pina-D1p (Gazza et al. 2005, Massa et al. 2004, McIntosh et al. 2006, Tranquilli et al. 2002), and with complete locus deletion, i.e., Pina-D1r (Chen et al. 2012), Pina-D1s (4222bp deletion), and Pina-D1u (6460bp deletion) (Chen et al. 2013), have been reported.

Occurrence of Pinb null haplotype is rare, but double null mutants have been reported, which occur with Pina-D1k allele and Pinb-D1h(t) (Chang et al. 2006, Ikeda et al. 2005, Tanaka et al. 2008). In other Pinb mutations with one SNP, i.e., Pinb-D1c (Leu60Pro) (Lillemo and Morris 2000), Pinb-D1d (Trp44Arg), Pinb-D1e (Trp39 to stop codon), Pinb-D1f (Trp44 to stop codon), Pinb-D1g (Cys56 to stop codon) (Morris et al. 2001), Pinb-D1l (Lys45Glu) (Pan et al. 2004), Pinb-D1q (Trp44Leu), and Pinb-D1t (Gly47Arg) (Chen et al. 2006), with multiple SNPs, with substitutions, with deletions, and with frame shifts, i.e., Pinb-D1h, i, j, k, m, n, o, p, r, s, u, v, w, x, aa, ab, and ac (Chang et al. 2006, Chen et al. 2007, 2013, Gedye et al. 2004, Ikeda et al. 2005, Lillemo et al. 2002, Massa et al. 2004, Ram et al. 2005, Tranquilli et al. 2002), have been reported.

An ample amount of information is available about puroindoline diversity at the international level. Indian wheat varieties have been screened for limited allelic diversity (Pina-D1a vs. Pina-D1b and Pinb-D1a vs. Pinb-D1b) using PCR amplification and a restriction digestion-based approach (Ram et al. 2002, Singh et al. 2012). The desire to understand the complete allelic diversity of Pin genes in Indian wheat germplasm remains a subject of interest. In this study, a sequencing-based approach was used to explore puroindoline allelic diversity and new allele discovery in Indian wheat germplasm with the aim to utilize this diversity in breeding programmes to develop wheat varieties with different textural properties.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

The 551 Indian wheat germplasm lines (cultivars, advanced breeding lines, functionally important landraces; Supplemental Table 1) were grown in single lines in a well-fertilized NABI field in the first year for DNA isolation. These lines were used for puroindoline gene amplification. Out of 551 lines, 82 lines (Supplemental Table 2) were grown in a completely randomized design (CRD) in three replications in the second year. These 82 lines were utilized for sequencing and grain hardness characterization.

Amplification and sequencing

Five different types of primer sets, three for Pina and two for Pinb, available in the literature (Gautier et al. 1994, Lillemo et al. 2006, Massa et al. 2004, Tranquilli et al. 2002; Supplemental Table 3), were utilized for initial amplification. Selected single primer sets for Pina (Pina-D1_F IV: 5′ CATCTATTCATCTCCACCTGC 3′; Pina-D1_R IV: 5′ GTGACAGTTTATTAGCTAGT 3′; Lillemo et al. 2006) and Pinb (Pinb-D1_FII: 5′AATAAAGGGGAGCCTCAACC 3′; Pinb-D1_RII: 5′ CGAATAGAGGCTATATCATCACCA 3′; Tranquilli et al. 2002) were used for further amplification of 551 cultivars. PCR was carried out using 300 ng of DNA, ready-to-use PCR master mix (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania), and 10 μM primer, with reaction conditions, initial denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, and amplification consisting of 35 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 58°C (56–62°C gradient) for 90 sec, and 72°C for 2 min, and with a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were gel purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and were used for sequencing after cloning. For cloning of amplified genes, pGEM-T Easy cloning vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used. Sequencing of the recombinant constructs was performed using standard T7 and SP6 sequencing primers on ABI DNA Analyser 3730 xl (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Sequence analysis

BLAST tool from http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov was used to identify any statistically significant homologous sequences with identity >98% and 100% query coverage for the sequenced clones of Pina and Pinb amplified fragments, against non-redundant dataset.

CAP3 sequence assembly program from http://pbil.univ-lyon1.fr/cap3.php was used for contig generation using forward and reverse sequences.

ClustalW2 multiple sequence alignment from http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/ and MEGA 5.10 from http://www.megasoftware.net/mega_beta.php were used for aligning various sequences of different cultivars.

Grain hardness

Grain hardness was determined by the Single Kernel Characterization System (SKCS 4100, Perten Instruments North America Inc, Springfield, IL, USA) and information about grain hardness, weight, moisture, and diameter was measured (Supplemental Table 4). Indian wheat lines were classified into different hardness groups according to two systems, System-I proposed by Morris et al. (2001) and System-II by Sharma et al. (2012).

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS version 16 software packages. The results were expressed as mean ± SE of experiments.

Results

Puroindoline gene amplification studies

One set of primers each for Pina and Pinb was selected after initial screening based on size, specificity, and reproducibility. Selected primer sets were used for amplification of 551 cultivars (Supplemental Table 1). PCR amplification of Pina-D1 gene indicated the presence of Pina-D1a functional allele in 53 lines, i.e., 9.6% of total lines. No amplification of Pina gene in 90.4% of the lines indicated absence of Pina in these lines. PCR amplification of Pinb-D1 gene from 551 Indian germplasms indicated amplification in all the lines studied. Out of 551 lines, 82 (Supplemental Table 2) were selected for grain texture determination and sequencing of Pina and Pinb genes.

Puroindoline gene sequencing studies

Sequencing of Pina and Pinb genes from 82 Indian wheat lines revealed 11 different allelic patterns (Table 1). Out of the 82 lines, seven had wild-type Pina and Pinb alleles (Pina-D1a and Pinb-D1a, Group 1, Table 1). All these lines belonged to the soft wheat category on the basis of SKCS results.

Table 1.

Allelic variation of puroindoline genes in Indian wheat cultivars

| Group no. | Type of Pina allele | Type of Pinb allele | No./percentage of cultivars | Nucleotide mismatch position/base change | Amino acid (AA) mismatch position/AA change | Cultivar names | Hardness (in SKCS units) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pina-D1a | Pinb-D1a | 7/8.5% | Wild type | Wild type | CHOTTILERMA, DLRRL35, GW89, H867, HS490, NAPHAL, SAFED LERMA | 21–36 |

| 2 | Pina-D1b | Pinb-D1a | 53/64.6% | Null allele (gene deletion) | Null allele | A90, A115, AGRALOCAL, C306, DBW46, DBW39, DHT12, HD3014, HD3002, HD2967, HPW251, HPW296, HS513, HS505, S508, HS295, HS1138, HS113, HS512, HUW612, HUW12, HW5210, HYB11, K65, K816, K0307, K0607, KSML3, LOK1, ACS6222, NP809, PBW343, PBW550, PBW621, PBW613, PBW628, RAJ4120, UAS315, UP2772, UP2771, UP215, VL916, VL921, VL829, VL924, VL401, VL925, VL935, VL616, WH10 61, WH1081, WH1062, WWONIR205 | 70–101 |

| 3 | Pina-D1a | Pinb-D1b | 8/9.7% | 223/G to A | 46/Gly to Ser | AKW318, HB208, NP852, NP818, NP825, NP824, SONALIKA, VL 934 | 58–84 |

| 4 | Pina-D1a | Pinb-D1e | 6/7.3% | 204/G to A | 39/Trp to stop | DHT23, HD2135, NARMADA195, NARBADA4, NARMADA112, NI5643 | 59–82 |

| 5 | Pina-D1a | Pinb-D1r | 1/1.2% | Insertion 127/G | Frame shift and stop codon at 48 | HYB65 | 76 |

| 6 | Pina-D1v* | Pinb-D1b | 1/1.2% | 41/C to T | (−) 15/Ala to Val | HS277 | 76 |

| 7 | Pina-D1w* | Pinb-D1b | 1/1.2% | 65/G to C 86/A to G |

(−) 7/Ser to Th 1/Asp to Gly |

SARBATI SONARA | 57 |

| 8 | Pina-D1a | Pinb-D1ad* | 1/1.2% | 92/T to C | 2/Val to Ala | WH1073 | 78 |

| 9 | Pina-D1b | Pinb-D1ae* | 1/1.2% | 93/T to A | No change | DBW17 | 87 |

| 10 | Pina-D1b | Pinb-D1af* | 2/2.4% | 232/G to T | 49/Glu acid to stop | K53, NP715 | 76, 81 |

| 11 | Pina-D1b | Pinb-D1ag* | 1/1.2% | 371/T to C | 95/Leu to Pro | K0710 | 95 |

Newly reported allele.

Genotypically hard textured lines exhibited 10 different allelic patterns, with the patterns non-functional null Pina-D1b and functional Pinb-D1a being the most common (64.6%, Group 2, Table 1). A significant number of lines (9.7%, Group 3, Table 1) had functional Pina-D1a and non-functional mutant Pinb-D1b alleles (Gly46Ser). Of the lines belonging to group 4, 7.3% (Table 1) had functional wild-type Pina-D1a and non-functional Pinb (Pinb-D1e, Trp39Stop) alleles. One cultivar belonging to Group 5 (Table 1), had functional Pina-D1a and non-functional mutant Pinb (Pinb-D1r, frame shift at Glu14Gly and stop codon at position 48). In total, two Pina (Pina-D1a, Pina-D1b) and four Pinb (Pinb-D1a, Pinb-D1b, Pinb-D1e, Pinb-D1r) published alleles were observed in Indian germplasm (Groups 1 to 5, Table 1).

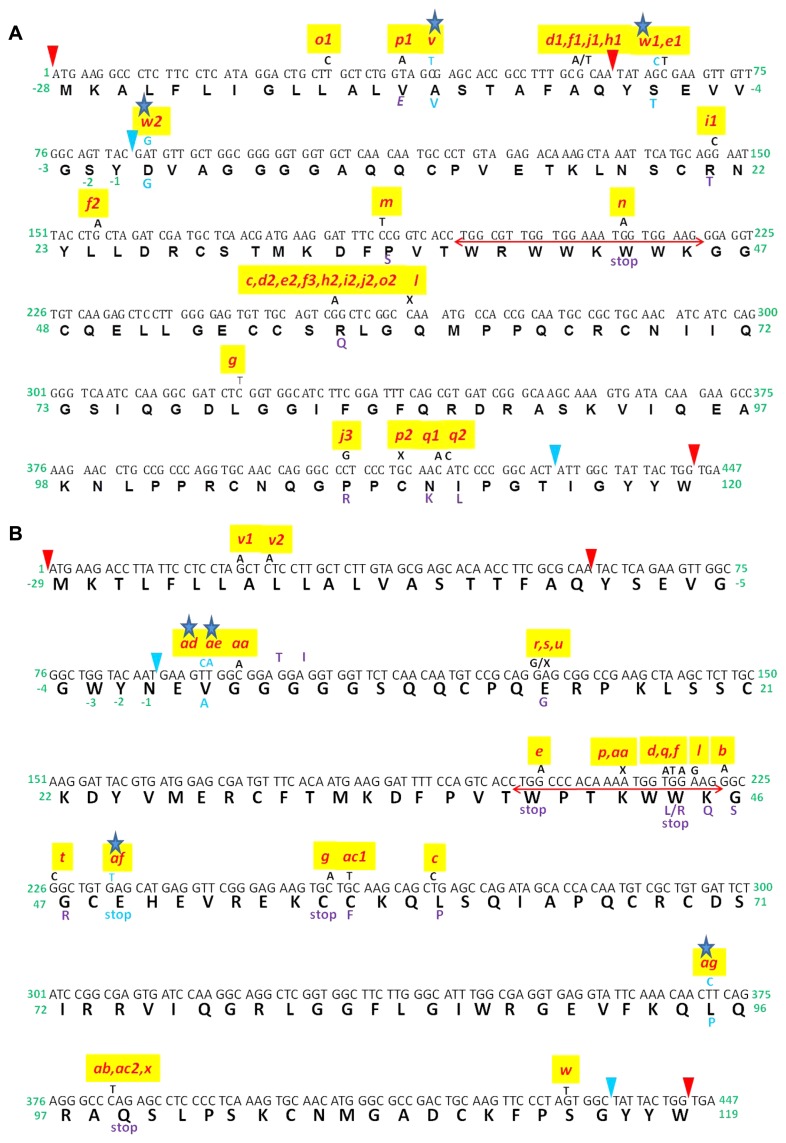

We identified six new allelic variants: two for Pina and four for Pinb (Fig. 1). The Pina and Pinb alleles resulted from SNPs in the signal peptide and functional part of the coding region, respectively. Among the two Pina alleles, one had SNP from C to T, at position 41 (Fig. 1A), in the pre-peptide part of the signal peptide that changed amino acid Ala −15 to Val (Table 1). The second allele had two mutations, G to C, at position 65, and A to G, at position 86 (Fig. 1A). The first mutation in the pro-peptide part of the signal peptide resulted in amino acid change from Ser −7 to Thr, while the second mutation changed the first amino acid of the functional mature protein from Asp1 to Gly. Until now, discovered Pina alleles have been from Pina-D1a to Pina-D1u. We are naming the new alleles identified in this study as Pina-D1v (Group 6, Table 1) and Pina-D1w (Group 7, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

A: Sequence of Pina gene showing its complete allelic diversity, including new alleles reported in this study. Letters with blue asterisk represent new alleles. Tryptophan rich domain is represented with horizontal red double arrows. Sequence between red arrowheads represents pre-peptide at the N terminal and that between red and blue arrowheads represents pro-peptide at N and C terminals. Red colored letters represent previously reported alleles. Multiple deletions, complete deletions, and insertions are not shown here, i.e., Pina-D1b, k, r, s, u. B: Sequence of Pinb gene showing its complete allelic diversity, including new alleles reported in this study. Letters with blue asterisk represent new alleles. Tryptophan rich domain is represented with horizontal red double arrows. Sequence between red arrowheads represents pre-peptide at the N terminal and that between red and blue arrowheads represent pro-peptide at N and C terminals. Red colored letters represent previously reported alleles. Multiple substitutions, deletions, complete deletions, and insertions are not shown here, i.e., Pinb-D1h, i, j, k, m, n, o.

Among the new Pina alleles, Pina-D1v was identified with Pinb-D1b allele in cultivar ‘HS277’. The hardness of ‘HS277’ was 76 (Supplemental Table 4). Another new allele, Pina-D1w, was identified in combination with Pinb-D1b in cultivar ‘Sarbati Sonora’ with an SKCS value of 57 (Supplemental Table 4).

Among the four new Pinb alleles identified in this study, the first had a single SNP (T to C at position 92) that changed amino acid Val2 to Ala (Group 8, Table 1, Fig. 1B). Until now, 29 Pinb alleles have been identified Pinb-D1a to Pinb-D1ac. We are naming the new allele identified in this study as Pinb-D1ad (Group 8, Table 1). This allele was found in ‘WH1073’ with a functional Pina-D1a allele and hardness around 78 (Supplemental Table 4). The second Pinb allele identified in this study resulted from SNP (T to A) at position 93 (Fig. 1B) that did not change the amino acid (synonymous mutation). We are naming this allele found in Indian cultivar ‘DBW17’ as Pinb-D1ae (Group 9, Table 1). The hardness of cultivar ‘DBW17’ was 87 (Supplemental Table 4). The third new allelic variant of Pinb resulted from a single SNP (G to T at position 232) that changed Glu49 to stop codon (Fig. 1B). It was found with non-functional Pina-D1b allele. We are naming this new allele found in Indian cultivars ‘K53’ and ‘NP715’ with hardnesses of 76 and 81, respectively, as Pinb-D1af (Group 10, Table 1). The fourth new allele resulted from a single SNP (T to C at position 371) with a subsequent amino acid change of Leu95 to Pro (Fig. 1B). We are naming this new allele, found with non-functional Pina-D1b allele in Indian cultivar ‘K0710’ with hardness of 95, as Pinb-D1ag (Group 11, Table 1).

Grain hardness and allele distribution studies

Hardness of the wheat genotypes as determined by the SKCS ranged from 21 to 101 (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 4). There are different systems of wheat classification based on grain hardness/texture. According to the first and frequently used system proposed by Morris et al. (2001) (System-I), wheat cultivars/lines are divided into four categories based on the SKCS data. These categories include ≤33 (soft), 34–46 (medium soft), 47–59 (medium hard), and ≥60 (hard). However, different countries have formulated and adopted their own classification systems. For India, Sharma et al. (2012) (System-II) has proposed a five category system with one additional category to better classify hard wheat genotypes. These categories include ≤34 (very soft), 35–54 (soft), 55–74 (medium hard), 75–89 (hard), and ≥90 (very hard). According to System-I (Table 2), out of 82 lines screened for hardness, 91.5% of the lines were categorized as hard (4.9% medium hard, 86.6% hard), and 8.5% as soft (1.2% medium soft, 7.3% soft). Soft wheat groups according to System-II (Table 3) were the same as System-I. Hard wheat lines were better classified according to System-II. According to this system, 18.3% of the lines were classified as medium hard, 64.6% as hard, and 8.5% as very hard.

Table 2.

Classification of wheat cultivars into different hardness groups according to Morris et al. 2001 (System-I)

| Hardness group | No./frequency of cultivars | Cultivar names |

|---|---|---|

| >33 | 6/7.3% | CHOTTI LERMA, DLRRL35, GW89, H867, NAPHAL, SAFED LERMA |

| 34–46 | 1/1.2% | HS490 |

| 47–59 | 5/6.09% | HB208, VL401, SARBATI SONARA, NP809, SONALIKA |

| >60 | 70/85.3% | A90, A115, AGRALOCAL, AKW318, C306, DBW17, DBW39, DBW46, DHT12, DHT23, HD2135, HD2967, HD3002, HD3014, HPW251, HPW296, HS113, HS1138, HS277, HS295, HS505, HS508, HS512, HS513, HUWI2, HUW612, HW5210, HYB11, HYB65, K53, K65, K816, KO307, KO607, KO710, KSML3, LOK1, MACS6222, NARBADA4, NARMADA112, NARMADA195, NI5643, NP818, NP824, NP825, NP715, NP852, PBW343, PBW550, PBW613, PBW621, PBW628, RAJ4120, UAS315, UP215, UP2771, UP2772, VL616, VL829, VL916, VL921, VL924, VL925, VL934, VL935, WH1061, WH1062, WH1073, WH1081, WWONIR205 |

Table 3.

Classification of wheat cultivars into different hardness groups according to Sharma et al. 2012 (System-II)

| Group no. | Proposed classification | Hardness group | No./frequency of cultivars | Cultivar names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Very soft | >34 | 6/7.3% | CHOTTI LERMA, DLRRL35, GW89, H867, NAPHAL, SAFED LERMA |

| II | Soft | 35–54 | 1/1.2% | HS 490 |

| III | Medium hard | 55–74 | 15/18.2% | AKW318, DHT23, HS113, NARBADA4, NARMADA112, NARMADA195, NP809, NP818, SARBATI SONARA, SONALIKA, UP215, VL401, VL934, VL935, WH1061 |

| IV | Hard | 75–89 | 53/64.6% | A115, AGRALOCAL, DBW17, DBW39, DBW46, HB208, HD2135, HD2967, HD3002, HD3014, HPW251, HPW296, HS1138, HS277, HS295, HS505, HS508, HS512, HS513, HUWI2, HUW612, HW5210, HYB11, HYB65, K53, K816, KO307, KO607, KSML3, LOK1, NI5643, NP824, NP825, NP715, NP852, PBW343, PBW550, PBW613, PBW621, PBW628, RAJ4120, UAS315, UP2771, UP2772, VL616, VL829, VL921, VL924, VL925, WH1062, WH1073, WH1081, WWONIR205 |

| V | Very hard | 90 or more | 7/8.5% | A90, C306, DHT12, K65, KO710, MACS6222, VL916 |

Frequency distribution of different pin alleles was studied in different agro-climatic zones of India (northern hill zone {NHZ}, north western plane zone {NWPZ}, central zone {CZ}, north eastern plane zone {NEPZ}, peninsular zone {PZ}, and southern hill zone {SHZ}; Supplemental Fig. 1). Variable frequency of different alleles was reported in these zones. Frequency of b/a allelic combination was highest in all the climatic zones studied, followed by a/a, a/e, and a/b alleles. Among the four frequently reported allelic combinations (b/a, a/a, a/e, a/b), a/b was not reported in CZ, PZ, and SHZ. The allelic combination a/a was not reported in PZ and SHZ, while a/e was not reported in PZ. New alleles were reported from all the zones except SHZ. The frequencies of new allelic combination in various zones were 3.4% (a/ad) in CZ, 12.5% (v/b) and 25% (b/af) in NEPZ, 3.4% (w/b) in NHZ, 6.6% (b/ae) in NWPZ, and 12.5% (b/ag) in PZ.

Discussion

All the soft grains studied from Triticeae have both PINA and PINB expressed proteins, and a mutation in any of these proteins leads to grain hardness (Giroux and Morris 1997). Initial screening revealed that 9.6% of Indian germplasm had functional Pina allele (Pina-D1a). Absence of Pina gene in most of the Indian wheat cultivars/lines may be related to the narrow genetic base and selection criteria for higher grain hardness for better chapatti making quality. Out of 82 lines, seven had wild-type and functional Pina (Pina-D1a) and Pinb (Pinb-D1a) alleles. All these lines had soft grain texture, supporting the earlier observation that puroindoline gene expression in its wild-type state (Pina-D1a/Pinb-D1a) is necessary for soft texture wheat (Morris 2002). This allelic combination was observed in high yielding exotic germplasm selected directly for cultivation in India (‘Chotti lerma’, ‘Safed lerma’) during the green revolution or in exotic germplasm included in the pedigrees of Indian wheat cultivars (‘HS490’, ‘GW 89’; Supplemental Table 2). Although soft wheat germplasm (‘Naphal’) exists in India, it has not been utilized for varietal development. Out of five different combinations of Pina and Pinb alleles in Indian wheat germplasm (a/a, b/a, a/b, a/e, a/r), the highest number of cultivars had b/a allelic combination and belonged to the hard wheat category. A high percentage of cultivars from CIMMYT (86%) carry this b/a allelic combination (Chen et al. 2013), while cultivars from North America, Chile, and Australia (Chen et al. 2013, Morris et al. 2001) have a higher frequency of a/b allele, and in cultivars from China, a/p allelic combinations are more common (Chen et al. 2013). The higher frequency of b/a allelic combination in Indian wheat cultivars/lines might be due to its higher frequency in indigenous germplasm, or direct introduction of CIMMYT cultivars in India as well as utilization of introduced cultivars in Indian breeding programmes. Another allelic combination, a/e, which was observed in 7.3% of the lines, was unique in Indian wheat cultivars. It has also been reported in cultivars from other countries, including those in North America (Morris et al. 2001) and China (Chen et al. 2007). Pinb-D1e allele resulted from stop codon at the 39th amino acid position, i.e., complete loss of function. The hardness of lines with a/e allelic combination varied from 59–82, which is similar to that of a/b allelic combination, i.e., 58–84, indicating a similar effect on grain hardness.

Allelic combination b/a provides higher hardness than a/b (Chen et al. 2013, Morris et al. 2001). A similar trend was also observed in this study. The hardness of Indian wheat lines with allelic combination b/a varied from 71–101, which was significantly higher than that of lines with allelic combination a/b (58–84). Allele combination a/b was present in both Indian germplasm and exotic germplasm.

Sequencing studies identified six unknown alleles, two for the Pina gene and four for the Pinb gene in Indian wheat germplasm, which were named according to standard nomenclature. Some of them might be associated with functional change of their respective proteins. New mutations in the Pina gene were observed in the signal peptide (pre- and pro-peptides), which could affect grain hardness. This is because PINs are synthesized as precursors. These precursors consist of a signal peptide, two cleavable domains (N-terminal and C-terminal), and mature protein (Gautier et al. 1994). These three domains have important functions during the processing of the mature protein. Consequently, any mutation in these regions could have an effect on grain endosperm texture due to the correct or incorrect processing of the PIN precursors. Among the new Pina alleles, Pina-D1v, with a mutation in the pre-peptide and found in NEPZ cultivars, might have been introduced into Indian germplasm from exotic germplasm as it was observed in Indian wheat cultivars directly selected for cultivation from exotic germplasm from Turkey/Kenya. The hardness of cultivars with the v/b allelic combination was well within the range of that of a/b allelic combination, indicating an insignificant effect on gene function. Another new allele, Pina-D1w, had mutations in the pro-peptide as well as the first amino acid of mature protein. Mutation in the first amino acid of mature protein changed aspartic acid to glycine. Aspartic acid is acidic and a polar amino acid with a negative side chain, whereas glycine is an aliphatic, non-polar, and neutral amino acid. This change is expected to exercise effect on the functional properties of the protein. Hardness of cultivars with w/b allelic combination was lower than that of the range of a/b allelic combination. As the mutation has changed the first amino acid from acidic to neutral, it might have a positive effect on translocation of PINA to starch granule membranes. Allelic w/b combinations reported from NHZ might have been introduced into Indian germplasm from exotic germplasm, as it was observed in Indian wheat cultivars directly selected for cultivation from exotic germplasm.

Among the mutations identified in the Pinb gene, Pinb-D1af with SNP that converted normal amino acid to stop codon, showed loss of gene function, as b/af allelic combination had grain hardness in the range of that of a/b rather than a/a. This b/af allelic combination reported from NEPZ might be of Indian origin, as it has been observed in cultivars of Indian origin and not reported in exotic cultivars or their derivative lines used in this study. Allele Pinb-D1ad changed amino acid valine to alanine at the second amino acid position of mature protein. Both of these are aliphatic, non-polar, and neutral amino acids and are not expected to change the function of the protein. Allele Pinb-D1ae had synonymous mutation and thus is not expected to change the function of the protein. Allele Pinb-D1ag had a change from aliphatic amino acid leucine to cyclic proline. This change, with respect to wild-type alleles, could also alter grain hardness. These allelic combinations, i.e., a/ad, b/ae, and b/ag, might be of Indian or exotic origin as pedigrees of cultivars with these allelic combinations had both germplasms.

Hardness of observed b/ae and b/ag allelic combinations was within the range of that of b/a allelic combination, indicating an insignificant effect on gene function. Hardness of lines with Pinb-D1ag allele was higher (95) than that of cultivars with Pinb-D1ae alleles (76–87). This might be because of changed amino acid (aliphatic to cyclic), which might have affected the function of protein.

Based on grain hardness, selected lines were classified according to two earlier proposed systems. According to System-I (Morris et al. 2001), Indian wheat lines were classified into four groups. But most of the Indian wheat lines are of hard type; hence, System-II (Sharma et al. 2012) seems to be a better classification system, which classifies them into five groups. Percentage of wheat lines belonging to the soft wheat category remained the same in both systems. Over 90% of the varieties fell under the hard wheat category. This might be due to selection preferences of Indian breeders for higher grain hardness for better chapatti making quality.

Variable frequency distribution of different pin alleles (old as well as new) in the different agro-climatic zones indicated an unbiased sample collection. All the zones showed highest frequency of b/a allelic combination. Some of the alleles were not found in a particular zone, which may not have been due to the absence of those alleles in the studied zone, but might have been due to the number of wheat lines used for the study. A comparatively lower number of cultivars selected for testing belonged to PZ and SHZ. These are tropical climate zones and wheat cultivation in these zones is very limited. Cultivars of temperate climate zones, NHZ, NWPZ, NEPZ, and CZ, had a better representation in this study. One of the new alleles, Pinb-D1ag, was reported from the less represented PZ.

In conclusion, identification of six new Pina and Pinb alleles indicates that Indian wheat germplasm can be a good source of novel genetic variability, and this can be used in breeding programmes to extend the range of textures of wheat. Additional studies are required in order to further investigate these alleles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by NABI’s core grant for agricultural biotechnology for the research project “Improvement of processing and nutritional quality in wheat”. We thank the Department of Biotechnology, Govt. of India, for the fellowship provided to RK.

Literature Cited

- Baker, R.J. (1977) Inheritance of kernel hardness in spring wheat. Crop Sci. 17: 960–962. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C., Zhang, H., Xu, J., Li, W., Liu, G., You, M. and Li, B. (2006) Identification of allelic variations of puroindoline genes controlling grain hardness in wheat using a modified denaturing PAGE. Euphytica 152: 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., He, Z.H., Xia, X.C., Xia, L.Q., Zhang, X.Y., Lillemo, M. and Morris, C.F. (2006) Molecular and biochemical characterization of puroindoline a and b alleles in Chinese landraces and historical cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Yu, Y., Xia, X. and He, Z. (2007) Prevalence of a novel puroindoline b allele in Yunnan endemic wheats (Triticum aestivum ssp. Yunnanense King). Euphytica 156: 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Zhang, F.Y., Xia, X.C., Dong, Z.D. and Cui, D.Q. (2012) Distribution of puroindoline alleles in bread wheat cultivars of the Yellow and Huai valley of China and discovery of a novel puroindoline a allele without PINA protein. Mol. Breed. 29: 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F., Li, H. and Cui, D. (2013) Discovery, distribution and diversity of Puroindoline-D1 genes in bread wheat from five countries (Triticum aestivum L.). B.M.C. Plant Biol. 125: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreil, L., Compoint, J.-P. and Marion, D. (1997) Interaction of puroindolines with wheat flour polar lipids determines their foaming properties. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45: 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Galande, A.A., Tiwari, R., Ammiraju, J.S.S., Santra, D.K., Lagu, M.D., Rao, V.S., Gupta, V.S., Misra, B.K., Nagarajan, S. and Ranjekar, P.K. (2001) Genetic analysis of kernel hardness in bread wheat using PCR-based markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103: 601–606. [Google Scholar]

- Gautier, M.-F., Aleman, M.-E., Guirao, A., Marion, D. and Joudrier, P. (1994) Triticum aestivum puroindolines, two basic cysteine-rich seed proteins: cDNA sequence analysis and developmental gene expression. Plant Mol. Biol. 25: 43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazza, L., Nocente, F., Ng, P.K.W. and Ponga, N.E. (2005) Genetic and biochemical analysis of common wheat cultivars lacking puroindoline a. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110: 470–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedye, K.R., Morris, C.F. and Bettge, A.D. (2004) Determination and evaluation of the sequence and textural effects of the puroindoline a and puroindoline b genes in a population of synthetic hexaploid wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109: 1597–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng, H., Beecher, B.S., He, Z. and Morris, C.F. (2012) Physical mapping of Puroindoline b-2 genes in wheat using ‘Chinese Spring’ chromosome group 7 deletion lines. Crop Sci. 52: 2674–2678. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, M.J. and Morris, C.F. (1997) A glycine to serine change in puroindoline b is associated with wheat grain hardness and low levels of starch-surface friabilin. Theor. Appl. Genet. 95: 857–864. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, M.J. and Morris, C.F. (1998) Wheat grain hardness results from highly conserved mutations in the friabilin components puroindoline a and b. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 6262–6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwell, P. and Schofield, J.D. (1986) A starch granule protein associated with endosperm softness in wheat. Cereal Chem. 63: 379– 380. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, T.M., Ohnishi, N., Nagamine, T., Oda, S., Hisatomi, T. and Yano, H. (2005) Identification of new puroindoline genotypes and their relationship to flour texture among wheat cultivars. J. Cereal Sci. 41: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, E., Nathalie, G., Michèle, D., Gérard, B. and Didier, M. (2013) Wheat grain softness protein (Gsp1) is a puroindoline-like protein that displays a specific post-translational maturation and does not interact with lipids. J. Cereal Sci. 58: 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kooijman, M., Orsel, R., Hessing, M., Hamer, R.J. and Bekkers, A.C.A.P.A. (1997) Spectroscopic characterization of the lipid-binding properties of wheat puroindolines. J. Cereal Sci. 26: 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Law, C.N., Young, C.F., Brown, J.W.S., Snape, J.W. and Worland, A.J. (1978) The study of grain protein control in wheat using whole chromosome substitution lines. In: Seed Protein Improvement by Nuclear Techniques, International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, Austria, pp. 483–502. [Google Scholar]

- Lillemo, M. and Morris, C.F. (2000) A leucine to proline mutation in puroindoline b is frequently present in hard wheats from Northern Europe. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100: 1100–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Lillemo, M., Simeone, M.C. and Morris, C.F. (2002) Analysis of puroindoline a and b sequences from Triticum aestivum cv. ‘Penawawa’ and related diploid taxa. Euphytica 126: 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Lillemo, M., Chen, F., Xia, X., William, M., Peña, R.J., Trethowan, R. and He, Z. (2006) Puroindoline grain hardness alleles in CIMMYT bread wheat germplasm. J. Cereal Sci. 44: 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, A.N., Morris, C.F. and Gill, B.S. (2004) Sequence diversity of puoindoline-a, puoindoline-b and the grain softness protein genes in Aegilops tauschii Coss. Crop Sci. 44: 1808–1816. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, R.A., Devos, K.M., Dubcovsky, J. and Rogers, W.J. (2006) Catalogue of gene symbols for wheat 2006 supplement. In: Annual wheat newsletter, Vol. 54, pp. 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.F., Lillemo, M., Simeone, M.C., Giroux, M.J., Babb, S.L. and Kidwell, K.K. (2001) Prevalence of puroindoline grain hardness genotypes among historically significant North American spring and winter wheats. Crop Sci. 41: 218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.F. (2002) Puroindolines: the molecular genetic basis of wheat grain hardness. Plant Mol. Biol. 48: 633–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z., Song, W., Meng, F., Xu, L., Liu, B. and Zhu, J. (2004) Characterization of genes encoding wheat grain hardness from Chinese cultivar GaoCheng 8901. Cereal Chem. 81: 287–289. [Google Scholar]

- Perretant, M.R., Cadalen, T., Charmet, G., Sourdille, P., Nicolas, P., Boeuf, C., Tixier, M.H., Branlard, G., Bernard, S. and Bernard, M. (2000) QTL analysis of bread-making quality in wheat using a doubled haploid population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100: 1167–1175. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, S., Boyko, E., Giroux, M.J. and Gill, B.S. (2002) Null mutation in puroindoline a is prevalent in Indian wheats: puroindoline genes are located in the distal part of chromosome 5DS. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 11: 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, S., Jain, N., Shoran, J. and Singh, R. (2005) New frame shift mutation in puroindoline B in Indian wheat cultivars Hyb65 and NI5439. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 14: 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam, A., Palombo, E.A. and Bhave, M. (2012) The Pinb-2 genes in wheat comprise a multigene family with great sequence diversity and important variants. J. Cereal Sci. 56: 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R., Rawat, A., Misra, B.K. and Nagarajan, S. (2012) Distribution of grain hardness in Indian wheat varieties and landraces. Wheat Inf. Serv. 114: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.M., Singh, S.K., Ahlawat, A.K., Jain, N., Singh, G.P., Ravi, I., Yadav, M. and Misra, P.C. (2012) Distribution of alleles of grain quality genes in Indian bread wheat varieties. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 72: 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sourdille, P., Perretant, M.R., Charmet, G., Leroy, P., Gautier, M.F., Joudrier, P., Nelson, J.C., Sorrells, M.E. and Bernard, M. (1996) Linkage between RFLP markers and genes affecting kernel hardness in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 93: 580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symes, K.J. (1965) The inheritance of grain hardness in wheat as measured by the particle size index. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 16: 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, H., Morris, C.F., Haruna, M. and Tsujimoto, H. (2008) Prevalence of puroindoline alleles in wheat varieties from eastern Asia including the discovery of a new SNP in puroindoline b. Plant Genet. Resour-C 6: 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Tranquilli, G., Heaton, J., Chicaiza, O. and Dubcovsky, J. (2002) Substitutions and deletions of genes related to grain hardness in wheat and their effect on grain texture. Crop Sci. 42: 1812–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Tsilo, T.J., Simsek, S., Ohm, J.-B., Hareland, G.A., Chao, S. and Anderson, J.A. (2011) Quantitative trait loci influencing endosperm texture, dough-mixing strength, and breed-making properties of the hard red spring wheat breeding lines. Genome 54: 460–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A.S., Bradburne, R.P., Fish, L. and Snape, J.W. (2004) New quantitative trait loci influencing grain texture and protein content in bread wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 40: 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Véronique, S.L., Brigitte, B., Larbi, R., Khalil, E., Gérard, B. and Didier, M. (2011) New insight into puroindoline function inferred from their subcellular localization in developing hard and soft near-isogenic endosperm and their relationship with polymer size of storage proteins. J. Cereal Sci. 53: 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, M.L., Wheeler, H.L., Huebsch, M.P., Smith, J.C., Figeys, D. and Altosaar, I. (2011) The tryptophan-rich domain of puroindoline is directly associated with the starch granule surface as judged by tryptic shaving and mass spectrometry. J. Cereal Sci. 52: 115–120. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.