Abstract

Background

Mice lacking calsequestrin-1 (CASQ1-null), a Ca2+ binding protein that modulates the activity of Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle, exhibit lethal hypermetabolic episodes that resemble malignant hyperthermia (MH) in humans when exposed to halothane or heat stress.

Methods

As oxidative species may play a critical role in MH crises, we treated CASQ1-null mice with two antioxidants, N-acetylcysteine (NAC provided ad libitum in drinking water) and Trolox (administered by intra-peritoneal injection), before exposure to halothane (2%, 1 h) or heat (41°C, 1 h).

Results

NAC and Trolox significantly protected CASQ1-null mice from lethal episodes, with mortality being: 79% (n=14), 25% (n=16) and 20% (n=5) during halothane exposure and 86% (n=21), 29% (n=21) and 33% (n=6) during heat-stress in un-treated, NAC- and Trolox- treated mice, respectively. During heat challenge, the increase in core temperature in CASQ1-null mice (42.3±0.1°C, n=10) was significantly reduced by both NAC and Trolox (40.6±0.3°C, n=6; 40.5±0.2°C, n=6). NAC treatment of CASQ1-null muscles/mice normalized caffeine sensitivity during in-vitro contracture tests, Ca2+ transients in single fibers, and significantly reduced the percentage of fibers undergoing rhabdomyolysis (37.6±2.5%, 38/101 fibers in 3 mice; 11.6±1.1%, 21/186 fibers in 5 mice respectively). The protective effect of antioxidant treatment likely resulted from mitigation of oxidative stress, as NAC reduced mitochondrial superoxide production, superoxide dismutase type-1 (SOD1) and 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) expression, and increased both reduced glutathione (GSH) and GSH/GSSG ratio.

Conclusions

These studies provide a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that underlie hyperthermic crises in calsequestrin-1 deficient muscle and demonstrate that antioxidant pre-treatment may prevent them.

INTRODUCTION

In humans, MH susceptibility (MHS) is an autosomal dominantly inherited pharmacogenetic disorder most often linked to mutations in ryanodine receptor type-1 (RYR1), the gene that encodes the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release channel of skeletal muscle.1–3 Individuals are diagnosed as MHS if they have experienced a MH crisis during anesthesia4,5 and/or score positive in a diagnostic in vitro caffeine-halothane contracture test.6,7 In some cases, life-threatening hyperthermic episodes have been reported in individuals in the absence of anesthetics during exposure to extreme environmental heat, physical exertion, or even during febrile illness.8 Hyperthermic crises triggered by high temperatures and humidity are collectively known as environmental heat-stroke (EHS). EHS crises exhibit a clinical presentation similar, but not identical, to that of MH: increased internal temperature, rhabdomyolysis, hypermetabolism, cyanosis, and increased serum levels of potassium (K+) and creatine kinase (CK).9,10 Interestingly, some EHS patients have a family history of MH11 and an association between RYR1 variants and exertional- or stress-induced sudden death (or rhabdomyolylis) have been reported.12–14

Although hypothesized on occasion in the literature,10–12 the similar presentation and pathophysiological mechanisms shared between MHS and EHS is still not widely recognized. Animal studies support the hypothesis of MHS and EHS being related disorders: in Porcine Stress Syndrome,15,16 pigs carrying a point mutation in RYR1 undergo MH episodes in response to halothane exposure, but can also trigger during heat challenge or emotional/physical stress. In addition, knock-in mice carrying point mutations in RYR1 linked to MHS in humans also exhibit heat- and anesthetic-induced MH episodes.17,18

We previously reported that male mice lacking calsequestrin-1 (CASQ1), the primary Ca2+ binding protein in the SR that interacts and modulates RYR1 Ca2+ release channel activity, exhibit lethal anaesthetic- and heat-induced hyperthermic episodes19,20 similar to that observed in RYR1 knock-in mice and MHS/EHS humans. Specifically, muscle fibers from CASQ1-knockout (CASQ1-null) mice exhibit impairments in Ca2+ handling consistent with their enhanced heat- and anesthetic-sensitivity: a) resting Ca2+ levels are slightly increased at physiological temperature (37°C) due to enhanced SR Ca2+ leak,19 b) total SR Ca2+ store content is greatly reduced,21 and c) SR depletion during repetitive stimulation is accelerated.22–24 However, a recent study failed to identify any mutations in the CASQ1 gene in MHS individuals within the North American population.25

Ca2+-dependent production of reactive oxygen/nitrogen (ROS/RNS) species has been proposed to play a crucial role in the cascade of events leading to enhanced SR Ca2+ leak, hypercontracture, and rhabdomyolysis in mice carrying a mutation in RYR1 linked to MHS in humans (RYR1Y522S/WT).26 In the present work, we tested the hypothesis that excessive ROS production also plays a central role in lethal hyperthermic crises observed in CASQ1-null mice. To test this hypothesis, we treated CASQ1-null mice with two different antioxidants (N-acetylcysteine and Trolox) to determine whether these treatments reduced the incidence of lethal events triggered by halothane and heat stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animals used in this study were males, as male CASQ1-null animals are more susceptible than females to trigger lethal MH-like crises when exposed to heat or halothane.19,20

A - In-vivo experiments

CASQ1-null mice and antioxidant treatment

CASQ1-null mice were generated as previously described.21 Mice were housed in micro-isolator cages, at 20°C, in a 12 h light/dark cycle, and provided free access to water and food. All experiments were conducted according to the Directive of the European Union 2010/63/UE and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the animal Ethical Committees of the University of Chieti (Chieti, Italy) and the University Committee on Animal Resources at the University of Rochester Medical Center (Rochester, NY, U.S.A.). Four month old male CASQ1-null mice were randomly assigned to three experimental groups: control group (untreated CASQ1-null mice); CASQ1-null mice treated with N-acetylcysteine (NAC, Sigma Aldrich, Italy), and CASQ1-null mice treated with (±)-6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox, Sigma Aldrich, Italy). For in vivo NAC treatment, CASQ1-null mice were provided ad libitum access to drinking water containing NAC 1% weight/volume (1% w/v) for 2 months (from 2 to 4 months of age). This dose of NAC for two months did not cause any noticeable negative side effects in CASQ1-null mice. Another cohort of CASQ1-null mice were treated with Trolox, dissolved in 1 M NaHCO3 water solution and administered by daily intra-peritoneal injection for 1 month at a dose of ~ 45 μg/g of body weight.27 Control CASQ1-null mice received either daily NAC-free drinking water or intraperitoneal injection of 1M NaHCO3 water solution without Trolox for 1 month. A group of wild type (WT) mice, randomly selected, were treated with NAC as an experimental control for NAC treatment for in vitro experiments. Samples size that we used in all in vivo experiments were based on previous work.19

Heat-stress protocol and measurements of internal core temperature

The effects of heat challenge were studied in WT, untreated CASQ1-null, NAC-treated CASQ1-null and Trolox- treated CASQ1-null mice. Animals were placed in a temperature-controlled environmental chamber in which the ambient temperature was maintained at 41°C (see19 for more detail). Breathing and spasmodic contractions were visually monitored. Muscle rigidity was manually confirmed by limb resistance immediately following animal death. Surviving animals were returned to normal housing conditions and monitored for 24 hours to assess possible delayed deaths. Internal temperature was measured using a rectal thermometer taped on the tails of the animals and recorded every 5 minutes throughout the duration of heat challenge (41°C, 1 h).

Halothane exposure

To determine susceptibility to volatile halogenated anaesthetics, WT, untreated CASQ1-null, as well as NAC- and Trolox-treated CASQ1-null mice were exposed to an air mixture containing halothane (Sigma Aldrich, Italy) at concentrations sufficient to induce stage 3 anaesthesia (2% halothane, with more added as necessary to induce and maintain this level of anaesthesia) using an Isotec 3 evaporator (Datex-Ohmeda, GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA). During halothane exposure, mice were kept in a chamber at constant temperature (32°C) to avoid a drop in body temperature during the anaesthesia. Respiration was monitored visually. The maximum exposure time to halothane was 1 h and surviving mice were then recovered by suspension of anaesthetic.

Quantitative plasma and serum analyses

For quantitative assessment of markers of rhabdomyolysis in blood/serum - i.e. creatine kinase (CK), potassium (K+) and calcium (Ca2+) - control CASQ1-null mice (not exposed to heat or halothane) and mice with brief (30–35 minute) exposure to a non-triggering heat-stress challenge were immediately anesthetized with diethyl ether before collecting blood samples via cardiac puncture. Mice were then subjected to thoracotomy and 500–800 μl of blood was collected from the right ventricle with a 26 G needle. Approximately half of this volume was placed in vials containing lithium heparin to prevent blood clotting and centrifuged at 2500 x g (4°C for 15 min) to isolate plasma. The other half of the blood was placed in a vial without anti-coagulant and serum was obtained by centrifugation at 4000 x g (4°C for 20 min). CK (in serum), K+ and Ca2+ (in plasma) levels were measured spectrophotometrically using a Screen Touch Master (Hospitex Diagnostic, Sesto Fiorentino, Italy). All standards for measurements of CK, K+ and Ca2+ were purchased from Hospitex Diagnostic (Sesto Fiorentino, Italy).

Grip Strength Test

Strength developed by untreated/NAC-treated WT and untreated/NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice during instinctive grasp measured as described previously.28 Briefly, mice were held by the tail and lowered to a metal grating connected to the shaft of a Shimpo Fgv 0.5X force transducer (Metrotec Group, San Sebastián, Spain). Once the mouse had firmly grasped the grating, a steady, gentle pull was exerted on the tail. Measurements of peak force generated by each mouse using fore- and hind-limbs were repeated three times with appropriate intervals (at least 30 s) to avoid fatigue. Average peak force values were normalized to total body mass measured before each experiment.

B – Hystological analyses

Immediately after heat stress, extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles were carefully dissected from control CASQ1-null (n = 3 mice; n = 101 skeletal muscle fibers analyzed) and NAC-treated CASQ1-null (n = 4 mice; n = 186 skeletal muscle fibers analyzed) mice. EDL muscles were also removed from WT mice (n = 3 mice; n = 97 skeletal muscle fibers analyzed) subjected to identical treatment following sacrifice. After fixation of EDL muscles at room temperature (RT) in 3.5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1 M Na cacodylate (EMS - Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) buffer, pH 7.2 overnight, small bundles of fixed fibers were post-fixed in 2% OsO4 (EMS, Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in the same buffer for 2 hours and then block-stained in aqueous saturated uranyl acetate (EMS - Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA).29 After dehydration, specimens were embedded in an epoxy resin (Epon 812). For histological analyses, semi-thin (800 nm) sections were cut with a Leica Ultracut R Microtome (Leica Microsystem, Vienna, Austria) using a Diatome diamond knife (DiatomeLtd. CH-2501 Biel, Switzerland). After staining with Toluidine Blue dye, the sections were viewed using a Leica DMLB light-microscope (Leica Microsystem, Vienna, Austria).

Determinations of the number of damaged fibers from WT and treated/untreated CASQ1-null mice after exposure to heat stress were performed on histological sections. Individual fibers were visually scored for rhabdomyolysis based on the presence of extended damage (i.e. contractures, disassembly of contractile elements, extended regions lacking striations). The number of fibers with such alterations is presented as a percentage of all fibers evaluated.

C - Ex-vivo and in-vitro experiments

Contractile responses and caffeine sensitivity of isolated intact EDL muscles

EDL muscles were dissected from hind limbs of untreated or NAC-treated WT and untreated or NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice and mounted in a myograph (Muscle Tester System, SI, Heidelberg) between a force transducer (SI H KG7B, SI, Heidelberg) and a micromanipulator-controlled shaft in a small chamber where oxygenated Krebs solution (Sigma Aldrich, Italy) was continuously circulated. For experiments with EDL muscles obtained from both WT and CASQ1-null treated mice, experiments utilized a Krebs solution + 2.5 mM NAC. Contractile responses and caffeine sensitivity were studied as previously described.19 The temperature was kept constant at 25°C. Stimulation conditions were optimized and muscle length was increased until force development during tetanus was maximal. To record responses to caffeine, muscles continuously stimulated at 0.2 Hz were exposed to increasing concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 14, 18, 22 mM) of caffeine with changes made every 3 minutes (no wash between applications). Experiments were performed on 6 WT EDL (3 mice), 5 NAC-treated WT EDL (3 mice), 6 CASQ1-null EDL (3 mice) and 8 CASQ1-null NAC-treated EDL (4 mice) muscles.

Cytosolic Ca2+ measurements in intact FDB muscle fibers

Single fibers were isolated from flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles of untreated/NAC-treated WT and untreated/NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice according to a modified collagenase/protease method described previously.30 Briefly, FDB muscles were dissected from mice and incubated in 0.2% collagenase and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) Tyrode solution (Sigma Aldrich, Italy) at 37°C for 1–2 h. After digestion, collagenase was removed and FDB fiber bundles were transferred to Tyrode solution (for 3 minutes), then 10% FBS Tyrode solution for 15 min (to block collagenase activity), and finally washed for 3 minutes in Tyrode solution before trituration with Pasteur pipettes of decreasing diameter to disperse single myofibers. After dissociation, FDB myofibers were plated on laminin-coated glass coverslips positioned at the center of 35-mm dishes to allow their sedimentation and attachment. FDB fibers from non-treated WT and CASQ1-null mice were incubated overnight in the culture medium. FDB fibers isolated from WT and CASQ1-null NAC-treated mice were incubated overnight with 2.5 mM NAC dissolved in the culture medium. 24 h after dissociation, fibers were incubated with 5 μM Fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2 AM; Invitrogen, San Giuliano Milanese, Italy) in 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM KH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 1 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Hepes and 1% BSA, pH7.4 (incubation buffer) for 30 min at 37°C. After Fura-2 loading, fibers were washed twice for 10 min in the incubation buffer without BSA. A minimum of 30 min was allowed for Fura-2 de-esterification before the fibers were imaged. Intracellular Ca2+ transients were recorded at 25°C using a dual-beam excitation fluorescence photometry setup (IonOptix Corp., Milton, MA, USA), as previously described.21,22 Single muscle fibers were stimulated with two distinct frequency protocols. Five fibers from each dish were routinely monitored as follows: 1) after 10 min of steady-state pacing at 0.5 Hz, 10 successive Ca2+ transients at 1 Hz were recorded from each fiber; 2) two trains of high frequency stimulation (60 Hz for 2 sec) were delivered with a recovery time of 5 min between trains. Fura-2 ratios were calculated and analyzed using IonWizard software (IonOptix Corp., Milton, MA, USA). Peak amplitude was calculated by subtracting basal fluorescence ratio values from peak ratio values. FDB fibers evaluated in these experiments were obtained from WT (3 mice), WT NAC-treated (2 mice), CASQ1-null (3 mice), and CASQ1-null NAC-treated (3 mice) mice.

In-vivo electroporation of mt-cpYFP cDNA into hindlimb footpads of anesthetized mice

Mt-cpYFP was expressed in FDB muscles by electroporation as described previously.31 Briefly, 4–5 month old WT and CASQ1-null mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine, 10 mg/kg xylazine, and 3 mg/kg acepromazine. Hindlimb footpads of anesthetized mice were then injected subcutaneously with bovine hyaluronidase (7 μl/foot, 2μg/μl). One hour later, hindlimb footpads were subcutaneously injected with 30 μg of mt-cpYFP cDNA (total volume10 μl in 71 mM NaCl) using a 30-gauge needle. The footpad was then electroporated (100 V/cm, 20 ms duration, and 20 pulses delivered at 1 Hz) using subcutaneous gold-plated electrodes placed perpendicular to the long axis of the muscle as described previously.31

FDB fiber isolation and mSOF measurement/analyses

One week after in vivo electroporation of mt-cp YFP, FDB fibers were acutely isolated from FDB muscle electroporated with mt-cpYFP cDNA by enzymatic digestion in 0.1% collagenase A, 45 min at 37°C, and plated on glass-bottom dishes in a rodent Ringer’s solution (146 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). mSOF productivity was measured as previously described31 with or without preincubation in 2.5 mM NAC for 30 min. Mt-cpYFP was excited using a 488 nm laser and detected at 515/30nm emission. Images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse C1 Plus Confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with a SuperFluor 60x (1.4 NA) oil immersion objective. Automated detection and analysis of individual mSOF events during time-lapse x, y imaging was performed using “Flash Collector,” a MATLAB-based image analysis program described in detail previously.31 Flash frequency and amplitude were expressed as the number of events/1000 μm2·100 s and ΔF/F0, respectively. Output data from Flash Collector were processed for statistical analyses using Microsoft Excel and SigmaPlot software suites.

Western blot analyses

EDL muscles were dissected from untreated WT (n = 7), WT treated with NAC (n = 5), CASQ1-null (n = 8), and CASQ1-null treated with NAC mice (n = 8) and then rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. EDL muscles were homogenized in 3% Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate (SDS, Sigma Aldrich, Italy) and 1 mM EGTA (Sigma Aldrich, Italy) buffer using a mechanical homogenizer and then centrifuged for 15 min at 900 x g at RT. The supernatant was collected and protein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using a modified Lowry method. Equal amounts of total protein (20–40 μg) were resolved in 12% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were visualized with Ponceau stain (Sigma-Aldrich, Italy) to confirm successful transfer and then blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk (EuroClone, Italy) in Tris-buffered saline 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T, Sigma Aldrich, Italy) for 1 h. Membranes were then probed with primary antibody diluted in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T overnight at 4°C: anti-superoxide dismutase type-1 (SOD1) antibody (rabbit polyclonal 1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) and anti-3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) antibody (mouse monoclonal 1:500, Merck Millipore, Italy) to detect expression of SOD1 and nitrated proteins respectively; anti-α-actinin antibody (mouse monoclonal 1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich, Italy) and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibody (mouse monoclonal 1:5000, OriGene Technologies, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) were used as loading controls for SOD1 and 3-nitrotyrosine respectively. Following incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were washed 3 times (10 min for each step) with TBS-T and then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:10,000, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated, Merck Millipore, Italy) diluted in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T for 1 h at RT. Finally, membranes were washed 3 times in TBS-T as described for primary antibodies. The proteins were detected by Enhanced Chemiluminescent Liquid (ECL, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The amount of protein on the immunoblots was quantified using Image J software.

Glutathione assay

4 months old untreated WT (n = 5), NAC-treated WT (n = 5), untreated CASQ1-null (n = 6), and NAC-treated CASQ1-null (n = 5) mice were sacrificed and hind limb muscles removed. Hind limb muscles were homogenized and total glutathione and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) levels were measured according to Rahman et al.32 Briefly, 0.1 g of tissue from hind limb muscles was homogenized in 1 ml of extraction buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.6% sulfosalicylic acid in 0.1M potassium phosphate buffer with 5 mM EDTA disodium salt, pH 7.3) on ice 3 times using a MICCRA D-1 Homogenizer (ART Prozess- & Labortechnik GmbH & Co., Germany). After homogenization, 10% trichloroacetic acid was added to the solution and the homogenized tissue sample was centrifuged at 8000 x g for 10 min at 2–4°C to obtain a supernatant containing glutathione. The sample was then stored at −80°C until further use. Intracellular total glutathione and GSSG levels were measured as described previously.32 The assay used for measurement of total glutathione and GSSG is based on the reaction of reduced glutathione (GSH) (directly or through conversion of GSSG to GSH by 2-vinylpyridine) with 5,5′-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), which produces the 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate anion (TNB) chromophore measured at 412 nm. The rate of TNB formation (change in absorbance/min) is proportional to the concentration of GSH in the sample. The assay was performed in 96 well plates (96 Well Tissue Culture Testplate; Spl Life Sciences, Korea) using an Absorbance Microplate Reader SpectraMAX 190 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data were normalized to a GSH standard curve with the GSH concentration in the samples determined from a linear regression from the GSH standard curve.32 All reagents for these experiments were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Italy.

D - Statistical analyses

Four month old male WT and CASQ1-null mice were randomly assigned to one of three different experimental groups: control group (untreated mice); WT and CASQ1-null mice treated with NAC and CASQ1-null mice treated with Trolox.

The following experiments were performed blinded: a) caffeine in-vitro contracture tests (performed at the University of Padova by Marta Canato and Carlo Reggiani); quantitative histological analysis of fiber damage (performed by Cecilia Paolini); measurements of reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) glutathione (performed by Alessandro De Marco).

Statistical significance in experiments on halothane- and heat-induced mortality (Fig. 1) was evaluated using a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. One-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey test was used for statistical analyses of all other experiments except for measurements of time-to-lethal-crises (presented in Fig. 2) in which statistical significance was determined using an un-paired student’s t-test (two-tailed). We performed a two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey test for the pairwise comparisons, for experiments in Figs. 2 and 3 in which we measured a dependent variable over multiple time points. In all cases, differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. We performed Fisher’s exact test using GraphPad software, whereas both one-way ANOVA, two-way repeated measures ANOVA and student’s t-tests were performed using Origin 8.0 software.

Figure 1. Pre-treatment with NAC and Trolox protect CASQ1-null mice from heat- and halothane-induced sudden death.

A–B) Incidence of heat- (A - 41°C for 1 h) and halothane-induced (B - 2% for 1 h) sudden and delayed death (within 24 h after challenge) in WT, untreated CASQ1-null, NAC-treated CASQ1-null (1% NAC provided ad-libitum from 2 to 4 months of age) and Trolox-treated CASQ1-null mice (Trolox was administered by intra-peritoneal injection at the dose of 45 μg/g of body weight). Mortality during heat challenge and halothane exposure was significantly reduced for both NAC- and Trolox-treated CASQ1-null mice compared to age-matched untreated CASQ1-null mice (*p<0.05). Abbreviations: CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin-1 knockout; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; WT, wild type.

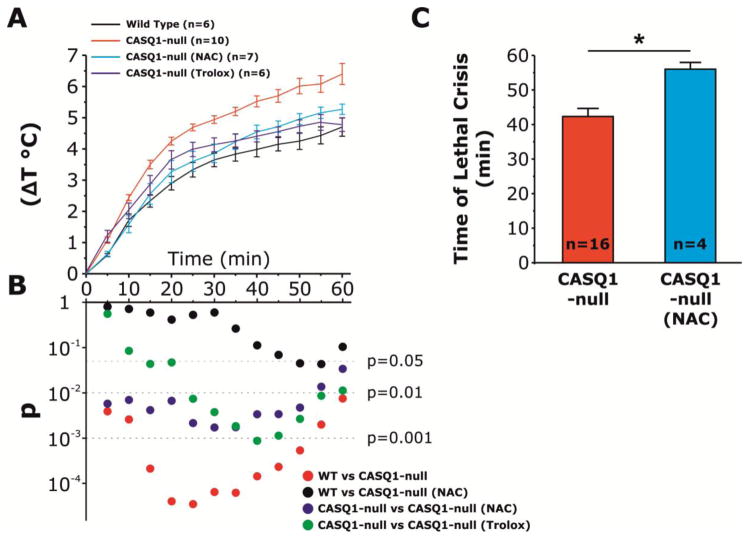

Figure 2. Pre-treatment with NAC and Trolox reduce the time-dependent increase in core temperature of CASQ1-null mice during heat challenge.

A) Increase in core temperature during exposure to heat challenge (41°C, 1 h) in WT, untreated CASQ1-null, NAC-treated CASQ1-null, and Trolox-treated CASQ-null mice. B) Semilog plot showing results of two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test performed during 1 h heat exposure (calculated every 5 min). C) In the few CASQ1-null mice treated with NAC that did not survive heat challenge (n = 4), NAC treatment significantly prolonged the time to onset of heat-induced sudden death. *p<0.01. Data are given as means ± SEM; n = number of mice. Abbreviations: CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin-1 knockout; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; WT, wild type.

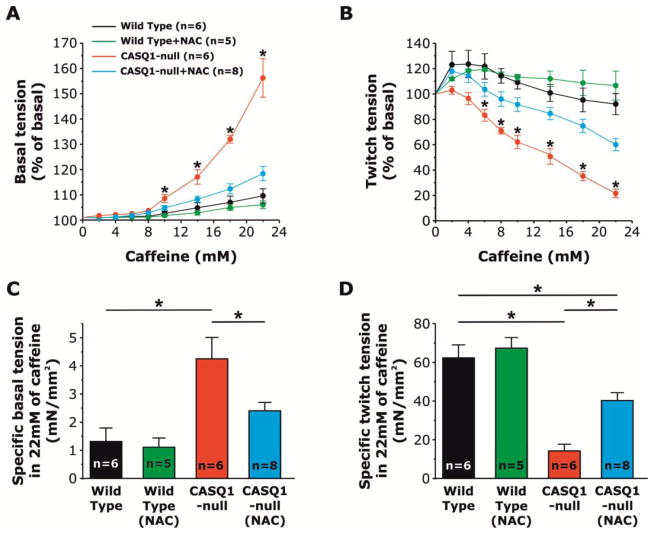

Figure 3. NAC treatment reverses increased caffeine sensitivity of EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice.

A) Increased caffeine response of resting tension of EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice is normalized to WT levels following treatment with NAC (1% ad libitum for 2 months). B) Twitch tension in EDL muscles is markedly reduced with increasing concentrations of caffeine in untreated CASQ1-null mice compared to WT, but significantly rescued in NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice. C) Compared to EDL muscles from WT and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice, specific basal tension in 22 mM caffeine is significantly increased in EDL muscles from untreated CASQ1-null mice. D) Compared to EDL muscles from WT and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice, specific twitch tension in 22 mM caffeine is significantly decreased in EDL muscles from untreated CASQ1-null mice (*p<0.05). EDL muscles from NAC-treated WT mice did not show significant differences in either specific basal or twitch tension in the presence of 22 mM of caffeine compared to EDL muscles from untreated WT mice. Experiments were analyzed by applying two-way repeated measures ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey test. Data are given as means ± SEM; n = number of EDL muscles. Abbreviations: CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin-1 knockout; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; WT, wild type.

RESULTS

Antioxidant treatment protects CASQ1-null mice from heat- and halothane-induced sudden death

We treated two different groups of CASQ1-null mice with two potent antioxidant compounds. One group was treated with NAC, a precursor of glutathione, provided ad-libitum in drinking water at a final concentration of 1% w/v for 60 days (from 2 to 4 months of age). A second group of CASQ1-null mice was treated with Trolox, a water soluble analog of vitamin E that exhibits both radical scavenging and antioxidant activities, administered daily for 4 weeks by intraperitoneal injection, prior to heat (41°C, 1 h) or halothane (2%, 1 h at 32°C) exposure. Both heat and halothane exposure were well-tolerated in all WT animals, but was lethal in about 80% of untreated CASQ1-null mice (Fig. 1 and Table 1). However, both NAC and Trolox treatment significantly reduced heat- and halothane-induced mortality in CASQ1-null mice. The incidence of death in untreated, NAC- and Trolox-treated CASQ1-null mice was respectively 86% (18/21, n = 21), 29% (6/21, n = 21) and 33% (2/6, n = 6) for heat stress and 79% (11/14, n = 14), 25% (4/16, n = 16) and 20% (1/5, n = 5) for halothane sensitivity.

Table 1. Antioxidants protect CASQ1-null mice from heat- and halothane-induced sudden deaths.

Number of mice (and experimental outcomes) tested during in-vivo heat challenge and halothane exposure. Whereas untreated CASQ1-null animals display a significant percentage of survival significantly lower compared to WT during both stress protocols (14% and 92% for heat stress; 21% and 100% for halothane exposure), pre-treatment with both NAC and Trolox bring back this percentage to values very close to those of WT (71% and 67% for heat stress; 75% and 80% for halothane exposure).

| HEAT | HALOTHANE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Responders | WT | CASQ1-null | NAC | Trolox | WT | CASQ1-null | NAC | Trolox |

| total tested | 13 | 21 | 21 | 6 | 8 | 14 | 16 | 5 |

| Survived | 12 | 3 | 15 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 12 | 4 |

| Sudden death | 0 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 1 |

| Delayed death | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| % Survived | 92% | 14% | 71% | 67% | 100% | 21% | 75% | 80% |

CASQ1-null, calsequestrin 1 knock-out; NAC, N-accetylcysteine; WT, wild type.

Antioxidants reduce hyperthermia during exposure to high environmental temperatures

We monitored rectal temperatures in WT, untreated CASQ1-null and NAC- and Trolox-treated CASQ1-null mice during heat challenge (60 min 41°C; Fig. 2A and Table 2). The time-dependent increase in core temperature observed in untreated CASQ1-null mice was significantly greater than that of WT animals. However, the change in core temperature (Fig. 2B) of both NAC- and Trolox-treated CASQ1-null mice was significantly lower than that of untreated CASQ1-null mice (40.6 ± 0.3°C, 40.5 ± 0.3 and. 42.3 ± 0.1°C respectively), but not WT mice (40.1 ± 0.1°C). In addition, in the NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice that did not survive heat challenge (4/21; see Table 1), the time to the onset of lethal crises was significantly prolonged (Fig. 2C), consistent with some degree of protection by NAC also in these animals.

Table 2. Antioxidants reduce hyperthermia during heat challenge in CASQ1-null mice.

Absolute and relative changes in core temperature measured at the beginning (t0) and end (t60) of the experiments. The increase in core temperature, during heat challenge, was significantly higher in CASQ1-null mice respect to WT animals (6.4±0.3 vs 4.7±0.3 respectively). However, we observed significant reduction of ΔT in CASQ1-null mice treated with NAC and Trolox (5.3±0.2 a 4.8±0.2 respectively).

| Wild type n=6 |

CASQ1-null n=10 |

CASQ1-null (NAC) n=7 |

CASQ1-null (Trolox) n=6 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t0 | 35.4 ± 0.3 | 35.9 ± 0.2 | 35.3 ± 0.2 | 35.8 ± 0.3 |

| t60 | 40.1 ± 0.1 | 42.3 ± 0.1 | 40.6 ± 0.3 | 40.5 ± 0.3 |

| ΔT | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 4.8 ± 0.2 |

CASQ1-null, calsequestrin 1 knock-out; ΔT, relative temperature; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; WT, wild type.

NAC treatment of CASQ1-null mice normalizes the threshold of caffeine-induced contracture

EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice exhibit an increased contractile responsiveness to low concentrations of caffeine compared to that observed for EDL muscles from WT mice (Fig. 3A). In addition, twitch force of EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice, but not WT mice, declines progressively during exposure to increasing caffeine concentrations (Fig. 3B). Both the increase in caffeine sensitivity of resting tension and caffeine-dependent decline in twitch force observed for EDL muscles from CASQ1-null muscles was ameliorated by NAC treatment (also present in the Krebs solution during the experiment, at the concentration of 2.5 mM). Specifically, the threshold for caffeine-induced resting contracture for EDL muscles from NAC-treated CASQ1-null muscles was significantly higher with respect to EDL muscles from untreated CASQ1-null and very close to that of EDL muscles from WT mice (Fig. 3A). In addition, the increased caffeine-dependent decline in twitch amplitude in EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice was partially counteracted by NAC treatment (Fig. 3B). Finally, NAC treatment normalized both resting basal contracture (Fig. 3C) and twitch tension (Fig. 3D) of EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice during exposure to 22 mM caffeine. EDL muscles from WT mice treated with NAC did not show significant differences with untreated WT in caffeine sensitivity of resting tension, caffeine-dependent decline in twitch force and in both specific basal and twitch tension at 22 mM of caffeine.

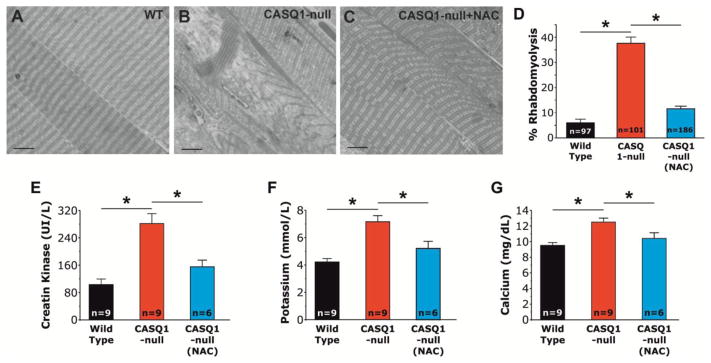

NAC treatment prevents rhabdomyolysis in muscle of CASQ1-null mice following heat challenge

To assess the efficacy of NAC in preventing rhabdomyolysis, EDL muscles from WT and untreated/treated CASQ1-null mice were quickly dissected at the end of heat challenge (or immediately after a lethal crisis). After fixation, the examination of histological sections showed in Fig. 4A–C, revealed that 37.6 ± 2.5% (38/101, n = 3 mice) of fibers were severely damaged in 3 EDL muscles from 3 triggered CASQ1-null mice (Fig. 4B). Similar alterations were only very rarely observed in surviving WT (6.2 ± 1.4%, 6/97, n = 3 mice) and CASQ1-null mice (11.6 ± 1.1%, 21/186, n = 5 mice) treated with NAC (Fig. 4A and C). The decreased incidence of fiber damage between untreated CASQ1-null mice and both WT and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice was significant (Fig. 4D). Consistent with the development of rhadomyolysis following heat challenge, serum CK levels and plasma K+ and Ca2+ concentrations were significantly elevated in untreated CASQ1-null mice, but not in either WT or NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice (Fig. 4E–G). This reduction in blood CK, K+ and Ca2+ levels in NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice was consistent with the significantly reduced incidence of rhabdomyolysis assessed by histological analysis (Fig. 4D). On the other hand, no differences in CK, K+ or Ca2+ levels were detected between the different groups (WT, untreated and NAC treated CASQ1-null mice) under resting, non-challenged conditions (data not shown).

Figure 4. NAC treatment prevents heat-induced rhabdomyolysis in CASQ1-null mice.

A–C) Morphological examination of EDL muscles after exposure to heat challenge (41°C, 1 h). D) Muscle fibers from untreated CASQ1-null mice exhibit an increased incidence of rhabdomyolysis (38/101 = 37.6 ± 2.5 %) compared to either WT or NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice (6/97 = 6.2 ± 1.4% and 21/186 = 11.6 ± 1.1%, respectively) (*p<0.01; n = number of fibers analyzed). E–G) Serum/plasma levels of CK (E), K+ (F) and Ca2+ (G) were all significantly elevated in untreated CASQ1-null mice following heat stress and significantly reduced following NAC-treatment (*p<0.05; n = number of mice). Data are given as means ± SEM. Scale bar: 10 μm. Abbreviations: Ca2+, calcium ion; CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin-1 knockout; CK, creatine kinase; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; K+, potassium; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; WT, wild type.

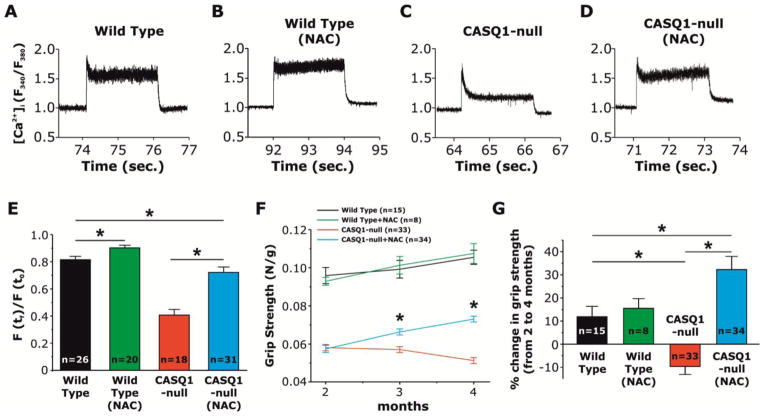

NAC treatment rescues Ca2+ transients and improves muscle function in CASQ1-null mice

We determined the effect of NAC treatment on myoplasmic Ca2+ levels at rest and during prolonged high-frequency stimulation (60 Hz, 2 s) in FDB fibers loaded with the ratiometric Ca2+ dye, Fura-2 (Fig. 5A–D). At room temperature (25°C), resting Fura-2 ratios were not different in fibers from untreated WT, NAC-treated WT, untreated CASQ1-null, and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice (data not shown). While high myoplasmic Ca2+ levels in fibers from WT mice were maintained throughout prolonged high-frequency stimulation (Fig. 5A), a significant decay was found in fibers from CASQ1-null mice (Fig. 5C). However, treatment of CASQ1-null mice with NAC reduced the Ca2+ transient decay during prolonged high-frequency stimulation to a level comparable to that of fibers from WT mice (Fig. 5C and D). In FDB muscle fibers from NAC-treated WT mice (Fig. 5A), the Ca2+ transient decay was slightly, but significantly, reduced with respect to that observed for untreated WT fibers (Fig. 5B and E). Additionally, grip strength of CASQ1-null mice was significantly increased by NAC treatment. Fig. 5F shows that while grip-strength decreased in untreated CASQ1-null mice from 2 to 4 months of age, NAC-treatment enhanced grip strength of CASQ1-null animals to a level closer to that of age-matched WT animals (Fig. 5F and G), an effect not observed in NAC-treated WT animals.

Figure 5. NAC treatment prevents the decline in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration during trains of 60 Hz stimulation in FDB fibers from CASQ1-null mice and improves grip strength in CASQ1-null mice.

A–D) Representative fura-2 fluorescence ratio (F340/F380) traces obtained during sustained high frequency electrical stimulation (60 Hz, 2 seconds) in single FDB fibers from untreated WT (A), NAC-treated WT (B), untreated CASQ1-null (C), and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice (D). The pronounced decline during 60 Hz stimulation in fibers from CASQ1-null mice is prevented by NAC treatment. E) Average (+/− SEM) fractional fura-2 ratio signal, calculated as the ratio between fura-2 ratio at the end of the stimulation (F (tf)) with that recorded at the start of the stimulation (F (t0)), during sustained 60 Hz stimulation in FDB fibers from untreated WT, NAC-treated WT, untreated CASQ1-null, and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice (*p<0.01; n = number of fibers). NAC significantly reduces Ca2+ transient decline in FDB fibers from both WT and CASQ1-null mice. F) Time-course of grip strength from 2 (beginning of treatment) to 4 months (end of treatment) of age in untreated WT, NAC-treated WT, untreated CASQ1-null, and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice. Grip strength was significantly (*p<0.01, n = number of mice) increased in NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice compared to untreated CASQ1-null mice, though still significantly reduced compared to that of untreated and NAC-treated WT mice. No significant differences were detected between untreated and NAC-treated WT mice. G) Bar graph showing the percent change in grip strength from 2 to 4 months of age in all four groups. Data are given as mean ± SEM. Abbreviations: CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin-1 knockout; FDB, flexor digitorum brevis; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; WT, wild type.

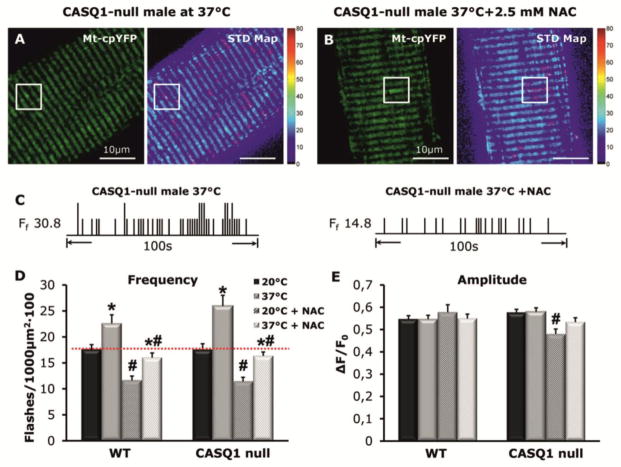

NAC treatment reduces mitochondrial superoxide flash (mSOF) production in FDB fibers of CASQ1-null mice

To determine the effect of NAC on oxidative stress in skeletal muscle of CASQ1-null mice, we measured mitochondrial superoxide flashes (mSOF) activity in dissociated FDB muscle fibers. NAC treatment significantly reduced mSOF frequency in FDB fibers from both WT and CASQ1-null mice at 20 and 37°C (Fig. 6A–D), while a temperature-dependent increase in mSOF frequency persisted in fibers from both WT and CASQ1-null mice (Fig. 6C). Importantly, NAC treatment reduced mSOF frequency in CASQ1-null fibers at 37°C to a level similar to that observed for fibers from untreated WT mice (Fig. 6D, red dotted line). On the other hand, mSOF amplitude was unchanged except for a minor decrease in fibers from NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice at 20°C (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. NAC treatment reduces frequency but not amplitude of mitochondrial superoxide flash (mSOF) activity in FDB fibers from WT and CASQ1-null mice.

A) left: Representative mt-cpYFP confocal image of a FDB fiber at 37°C obtained from a CASQ1-null mouse; boxed region indicates an area containing mSOF activity; right: standard deviation map of mSOF analysis for this fiber. mSOF events are circled in magenta. Scale bars = 10μm. B) Same as A except that the fiber was pretreated with 2.5 mM NAC for 30 min. C) Schematic mSOF event registry for the CASQ-null fibers shown in A and B. D–E) Average (± SEM.) mSOF frequency (D) and amplitude (E) for fibers obtained from WT (n = 24–43 cells from 2–4 mice) and CASQ1-null mice (n = 21 cells from 3–4 mice) at 20°C and 37°C with and without 30 min pre-treatment with 2.5 mM NAC. *p<0.05 compared with corresponding 20°C; #p<0.05 compared with and in the absence of NAC. Abbreviations: CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin 1 knockout; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; mSOF, mitochondrial super-oxide flash; WT, wild type.

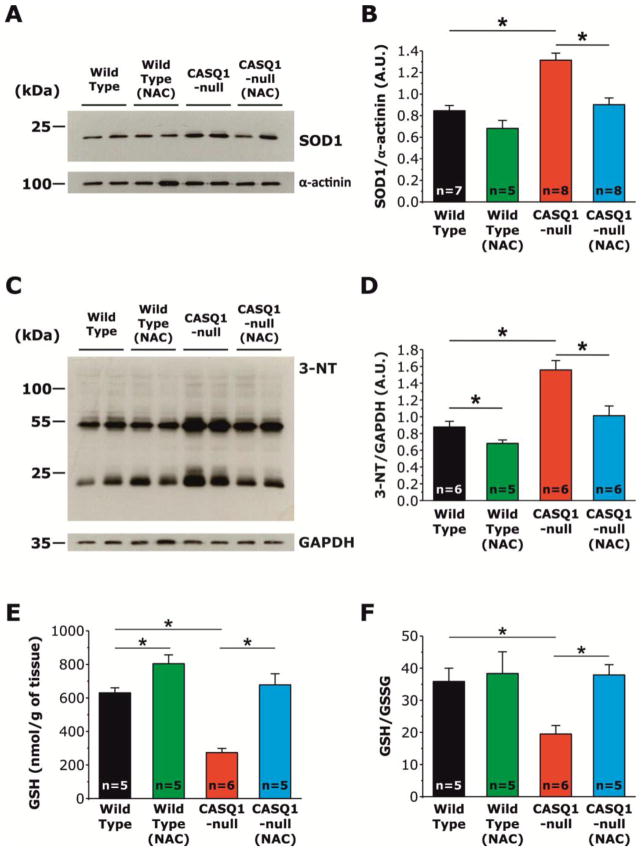

NAC treatment reduces superoxide dismutase type-1 (SOD1) expression, 3-nitrotyrosylation (3-NT), and oxidative stress

To verify the efficacy of NAC treatment to reduce oxidative stress, we measured: a) expression levels of superoxide dismutase type-1 (SOD1), one of three enzymes that catalyze the dismutation of superoxide (O2−) into oxygen (O2) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2),33 the first step in the elimination of reactive species of oxygen (ROS); b) levels of 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT), a product of nitration of tyrosine residues of proteins mediated by reactive species of nitrogen (RNS) such as peroxynitrite anion and nitrogen dioxide, which are indicators of oxidative stress and oxidative protein damage34; c) global amount of reduced glutathione, a molecule synthetized from amino acids that is capable of reducing disulfide bonds formed within cytoplasmic proteins to cysteines by serving as an electron donor; and d) the ratio of reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) glutathione, a recognized biomarker of oxidative stress.35 Western blot analyses, performed on homogenates from EDL muscles of untreated WT, NAC-treated WT, untreated CASQ1-null, and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice revealed that SOD1 expression in CASQ1-null mice, significantly increased compared to WT mice, was normalized to values close to that of WT mice following treatment with NAC (Fig. 7A and B). The increased expression of SOD1 in CASQ1-null mice likely reflects a compensatory response to the excessive production of superoxide within mitochondria (see Fig. 6), a finding in agreement with the observation that SOD1 expression and activity are increased under conditions of high oxidative stress.36–39 In the same samples, we also measured 3-NT levels, a recognized biomarker of oxidative stress, cell damage, and inflammation. As shown in Fig. 7C and D, EDL muscles from untreated CASQ1-null mice display a significant increase in 3-NT compared to that of EDL muscles from untreated WT and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice. Thus, NAC treatment of CASQ1-null mice reduced 3-NT to a level comparable to that of untreated WT mice.

Figure 7. NAC treatment reduces SOD1 expression, 3-nitrotyrosylation (3-NT), and the increased oxidative stress of EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice.

A) Representative immunoblots showing expression levels of SOD1 in EDL muscles from untreated WT (n = 7), NAC-treated WT (n = 5), untreated CASQ1-null (n = 8), and NAC-treated CASQ1-null (n = 8) mice. B) Relative band densities, expressed as SOD1/α-actinin ratio, show that SOD-1 expression is significantly increased in EDL muscles of CASQ1-null mice compared to that for both untreated WT and NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice. SOD1 expression was not significantly different between EDL muscles from untreated and NAC-treated WT mice. C) Representative immunoblots showing levels of 3-nitrotyrosylation (3-NT) in untreated WT (n = 6), NAC-treated WT (n = 5), untreated CASQ1-null (n = 6), and NAC-treated CASQ-null (n = 6) mice. D) Relative band densities, expressed as 3-NT/GAPDH ratio, show that levels of 3-NT are significantly increased in EDL muscles from CASQ1-null mice compared to that of WT mice. NAC treatment significantly reduced levels of 3-NT in EDL muscles from both WT and CASQ1-null mice. E-F) Values of reduced glutathione (GSH, expressed as nmol/g of tissue) and GSH/GSSG ratio are significantly reduced in EDL muscle homogenates from CASQ1-null mice compared to that from WT and are significantly increased after treatment with NAC. Data are given as means ± SEM; n = number of mice. Abbreviations: 3-NT, 3-nitrotyrosine; CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin-1 knockout; GAPDH, Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; SOD1, superoxide dismutase type-1; WT, wild type.

As GSH and GSSG levels reflect the overall cellular redox state, we quantified the amount of reduced glutathione (GSH) and GSH/GSSG ratio in hind-limb muscle homogenates from untreated/NAC-treated WT and untreated/NAC-treated CASQ1-null mice. While both GSH (nmol/g of tissue, Fig. 7E) and the GSH/GSSG ratio were significantly reduced (~57% and ~46%, respectively; Fig. 7E and F) in muscles from CASQ1-null mice compared to that of WT mice, treatment of CASQ1-null mice with NAC restored both GSH levels and the GSH/GSSG ratio to values similar to that of WT, consistent with NAC treatment reducing oxidative stress.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

Ablation of CASQ1 in mice results in increased susceptibility of CASQ1-knockout animals to lethal heat- and halothane-induced hyperthermic episodes.19,20,40 This phenotype closely resembles that observed in porcine stress syndrome,15,16 knock-in mice carrying MHS mutations in RYR1,17,18 and some cases of RYR1-linked MH and EHS in humans.11–13 Here, we tested the hypothesis that excessive oxidative stress contributes to lethal hyperthermic episodes in male CASQ1-null mice.

In our studies, antioxidant treatment (with either NAC or Trolox) reverses several pathophysiological phenomena that underlie hyperthermic crises in CASQ1-null mice: a) increased elevation in core temperature (Fig. 2A), b) enhanced caffeine sensitivity of skeletal muscle to develop contractures (Fig. 3A and C), and c) increased muscle fiber damage and rhabdomyolysis (Fig. 4A–D). Most importantly, antioxidant treatment prevented lethal heat- and halothane-induced episodes (Fig. 1), possibly by reducing mitochondrial superoxide production and oxidative stress (Figs. 6 and 7). These results support recent evidence that excessive production of oxidative species is a key event in the onset of these life-threatening crises.26

Molecular mechanisms underlying lethal hyperthermic episodes: role of oxidative stress

MHS is linked to RYR1 mutations that enhance SR Ca2+ leak and the sensitivity of the SR Ca2+ release process to activation.41 However, this may be an oversimplified view of the complex events that underlie MH/EHS responses as recent findings provides additional information that must also be taken into account:

Only a subset of MHS individuals have been linked to a specific gene mutation: 60–70% to RYR141,42 and ~1% to the DHPR α1S-subunit.43,44 Mutations in other gene(s) could be responsible for some MHS cases in the remaining fraction. However, whereas our results indicate that CASQ1 ablation in mice results in a phenotype that resembles MHS/EHS,19,20,40 loss-of-function mutations in the CASQ1 gene have not been linked to MHS/EHS in humans. Indeed, Kraeva et al.25 failed to identify any mutations within the CASQ1 coding region in 75 unrelated MHS patients diagnosed by caffeine-halothane contracture test, thus concluding CASQ1 is an unlikely genetic locus for MHS within the North American population. A similar conclusion was reached in another study of European MHS patients (Vincenzo Sorrentino, M.D. Professor, Department of Molecular and Developmental Medicine, University of Siena, Siena 53100, Italy; personal communication: March 2014). To date only one disease mutation in the CASQ1 gene (N244G) has been detected in a group of patients that exhibit a myopathy characterized by weakness, fatigue, and the presence of large vacuoles containing characteristic inclusions that result from the aggregation of sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) proteins.45 However, an increase in susceptibility to MH has not been demonstrated in these families.

In-vitro contracture tests used to diagnose MHS only work when extracellular Ca2+ is included in the solution bathing the muscle biopsy,46–48 suggesting that Ca2+ influx may play a critical role in the MH crises. Interestingly, store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), a Ca2+ influx mechanism triggered by store depletion in which STIM1 Ca2+ sensors in the SR activate Ca2+ influx through Orai1 Ca2+ channels in the transverse tubule membrane,49,50 is significantly enhanced in human skeletal fibers from MHS patients.51

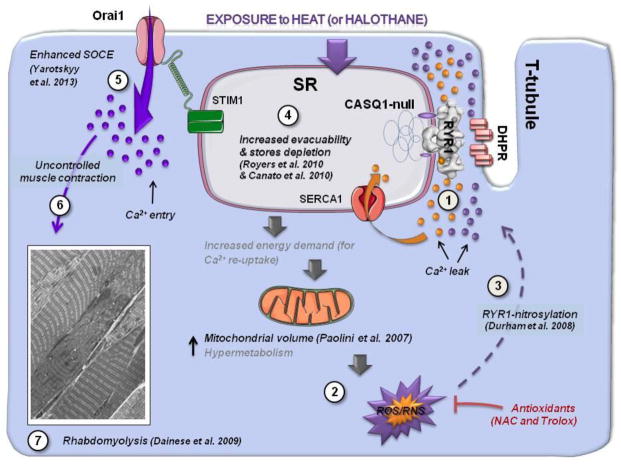

Fig. 8 depicts a proposed cascade of events linking SR Ca2+ leak (step 1) to rhabdomyolysis of skeletal muscle fibers (step 7). The model is based both on results presented here and in related previous studies. CASQ1 deficiency increases susceptibility of mice to heat- and halothane-induced contractures: indeed, CASQ1-deficiency SR lowers Ca2+ buffering and increases RYR1 Ca2+ leak,52 which together serve to increase SR evacuability53 and promote SR Ca2+ depletion.22,54 Even under resting conditions (follow orange labeling), SR Ca2+ leak (step 1) would lead to an increased energy demand (required for continual SERCA-mediated SR Ca2+ re-uptake) and enhanced oxidative stress (step 2) due to increased mitochondrial content21 and activity, a scenario that predisposes CASQ1-null mice to lethal reactions under stress.19 During exposure to heat or halothane, the sequence of events leading to lethal crises involve (follow purple labeling): a) excessive RYR1 Ca2+ leak and increased oxidative and nitrosative stress (steps 1 and 219,31); b) RYR1 S-nitrosylation, resulting in a feed-forward mechanism to further increase RYR1 leak (step 326); c) SR Ca2+ store depletion (step 422); d) activation of SOCE resulting in massive Ca2+ entry (step 524); e) uncontrolled contractures and rhabdomyolysis (steps 6 and 719).

Figure 8. Proposed model for NAC-mediated prevention of heat- and halothane-induced rhabdomyolysis in CASQ1-null mice.

Schematic model proposing a series of events linking SR Ca2+ leak (step 1) to rhabdomyolysis during heat- or halothane exposure (step 6) in muscle from CASQ1-null mice. Resting Ca2+ leak and oxidative stress are slightly elevated (compared to WT) in mice lacking CASQ1 (shown as orange junctional Ca2+ ions). During exposure to heat or halothane, SR Ca2+ leak (shown as additional purple junctional Ca2+ ions) and oxidative stress (steps 1 and 2) are further increased, driving a feed-forward mechanism (step 326) that ultimately leads to SR Ca2+ store depletion (step 422,53), activation of SOCE (step 524), and uncontrolled Ca2+ influx resulting in severe contractures and rhabdomyolysis (steps 6 and 719). The protective effects of NAC and Trolox shown in this study likely result from direct effects of the antioxidants to reduce oxidative stress, thus blocking the feed-forward mechanism (steps 3 to 5) leading to SOCE activation. Abbreviations: Ca2+, calcium ion; CASQ1-null, Calsequestrin-1 knockout; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; SOCE, Store Operated Ca2+ Entry; WT, wild type.

Possible molecular mechanisms by which antioxidants prevent lethal hyperthermic episodes

The full understanding of the molecular mechanism by which anti-oxidants are capable of preventing lethal episodes in CASQ1-null mice may require additional investigation. Several publications, though, have demonstrated that an increased production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS) results in RYR1 S-nitrosylation/glutathionylation, which increases its opening probability.26,55–58 At physiological conditions, the normal levels of oxidative stress could be responsible for a basal RyR1 low-opening probability, which would cause a small SR Ca2+ leak and in turn influence the total SR Ca2+ content. This hypothesis seems to be confirmed by data in Fig. 5B and D showing how NAC has an effect also on Ca2+ transient of WT fibers: indeed in these experiments the SR of WT fibers treated with NAC releases more Ca2+ during prolonged stimulation. Furthermore, data presented in Fig. 3B and D shows that WT muscles treated with NAC sustain twitch-tension better than untreated WT muscles, as their SR is likely more depletion-resistant when exposed to increasing caffeine concentrations. Our results are well in agreement with those reported in Durham et al.26: indeed, in those experiments NAC treatment of WT mice resulted in a modest increase in frequency-dependent contractile force in soleus and also maximal caffeine-induced contractile force. Together, these findings suggest that basal levels of oxidative stress have a modest inhibitory effect on maximal Ca2+ release and contraction also in WT, possibly via an effect on basal SR Ca2+ leak and store content. According to this model, the protective effect of NAC and Trolox results from a reduction in oxidative stress in muscle (supported by data in Figs. 6 and 7), thus reducing Ca2+ leak and blocking the feed-forward mechanism that promotes SR Ca2+ depletion22 (supported by data in Figs. 3B and D and 5 A-E) and SOCE activation.24 Whether RYR1 S-nitrosylation26 occurs in CASQ1-null mice and the degree to which NAC and Trolox treatment prevents RYR1 S-nitrosylation and/or uncontrolled Ca2+ entry through SOCE channels requires further investigation.

The model proposed in Fig. 8 provides a framework for future investigations aiming to identify and develop drugs to prevent hyperthermic crises by blocking either SR Ca2+ leak or SOCE, two key steps that represent potentially viable therapeutic targets. Indeed, AICAR, an activator of the energy sensing kinase AMPK59 and a partial RYR1 agonist, reduces SR Ca2+ leak and prevents heat-induced sudden death in RYR1Y522S/WT knock-in mice.60 In addition, dantrolene (or its analog azumolene), the drug of choice for acute treatment of MH crises,61 reduces RYR1 Ca2+ release62 and limits excessive Ca2+ entry due to activation of SOCE.63,64

Significance of the study

Because MH reactions during anesthesia are rare, patients are not routinely tested/screened for MHS and preventive anesthetic measures are not typically taken to avoid hyperthermic crises in individuals who are not known to be at increased risk for MHS. Indeed, in most cases, diagnosis of MH performed using standard protocols6,7 follows a suspected MH episode (i.e. proband and/or blood related family members). Our results demonstrating that pre-treatment with antioxidant (N-acetylcysteine and Trolox) protects CASQ1-null mice from lethal hyperthermic events induced by exposure to either halothane- or heat-stress may suggest a possible preventive (and inexpensive) therapy that could be used to reduce the risk of MH reactions in patients undergoing anesthesia that have not pre-screened for MHS. However, further investigation is needed to determine a) the minimal effective antioxidant dose and b) the efficacy of acute antioxidant treatment in preventing hypethermic crises in-vivo. Indeed, in our experiments, the NAC dose used here (1 to 1.5 mg/g body weight), which was similar to that used in RYR1Y522S/WT knock-in mice,26 is ~10x higher than that tested in a recent human clinical trial (acute oral administration) evaluating the effect of NAC on muscle fatigue during exercise (0.15 mg/g of body weight).65 In addition, since CASQ1 mutations have not been identified in MHS patients,25 it will be important for future studies to validate whether chronic antioxidant treatment also provides protection from heat- and halothane-induced episodes in RYR1 mouse and pig models of MHS and EHS.15–18

Finally, together with previous studies,19–24,26 our results indicate that the increased susceptibility of some individuals to MHS (and EHS) may result from defects in proteins that interact and regulate RYR1 Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of Funding: This study was supported by the following grants: a) Italian Telethon ONLUS Foundation (Rome, Italy): GGP13213 to Feliciano Protasi and Carlo Reggiani; b) National Institute of Health (Bethesda, MD, U.S.A): AR059646 to Robert T. Dirksen (and subcontract to Feliciano Protasi); c) Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA275574) to Robert T. Dirksen (and subcontract to Feliciano Protasi); d) AR053349 to Robert T. Dirksen (and subcontract to Feliciano Protasi); e) the Academia Dei Lincei Fund (Rochester, NY, U.S.A.) to Lan Wei-Lapierre.

Abbreviations used

- CASQ

calsequestrin

- CPVT

catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- CRU

calcium release unit

- EDL

extensor digitorum brevis

- EM

electron microscopy

- FDB

flexor digitorum brevis

- EHS

environmental/exertional heat-stroke

- IVCT

in-vitro contracture test

- MH

malignant hyperthermia

- mSOF

mitochondrial super-oxide flash

- MHS

MH susceptibility

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- ROS and RNS

reactive oxygen and nitrogen species

- RYR

ryanodine receptor

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F. Ryanodine receptors of striated muscles: a complex channel capable of multiple interactions. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:699–729. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denborough M. Malignant hyperthermia. Lancet. 1998;352:1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacLennan DH, Phillips MS. Malignant hyperthermia. Science. 1992;256:789–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1589759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finsterer J. Current concepts in Malignant Hyperthermia. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2002;4:64–74. doi: 10.1097/00131402-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glahn KPE, Ellis FR, Halsall PJ, Müller CR, Snoeck MM, Urwyler A, Wappler F. European Malignant Hyperthermia Group: Recognizing and managing a malignant hyperthermia crisis: guidelines from the European Malignant Hyperthermia Group. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:417–20. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The European Malignant Hyperthermia Group. A protocol for the investigation of malignant hyperpyrexia (MH) susceptibility. The European Malignant Hyperpyrexia Group. Br J Anaesth. 1984;56:1267–1269. doi: 10.1093/bja/56.11.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larach MG. Standardization of the caffeine halothane muscle contracture test. North American Malignant Hyperthermia Group. Anesth Analg. 1989;69:511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehmann-Horn F, Klingler W, Jurkat-Rott K. Nonanesthetic malignant hyperthermia. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:915–917. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318232008f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouchama A, Knochel JP. Heat stroke. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1978–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopkins PM, Ellis FR, Halsall PJ. Evidence for related myopathies in exertional heat stroke and malignant hyperthermia. Lancet. 1991;338:1491–1492. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92304-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis M, Brown R, Dickson A, Horton H, James D, Laing N, Marston R, Norgate M, Perlman D, Pollock N, Stowell K. Malignant hyperthermia associated with exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis or congenital abnormalities and a novel RYR1 mutation in New Zealand and Australian pedigrees. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:508–515. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capacchione JF, Sambuughin N, Bina S, Mulligan LP, Lawson TD, Muldoon SM. Exertional rhabdomyolysis and malignant hyperthermia in a patient with ryanodine receptor type 1 gene, L-type calcium channel alpha-1 subunit gene, and calsequestrin-1 gene polymorphisms. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:239–244. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c29504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groom L, Muldoon SM, Tang ZZ, Brandom BW, Bayarsaikhan M, Bina S, Lee HS, Qiu X, Sambuughin N, Dirksen RT. Identical de novo mutation in the type 1 ryanodine receptor gene associated with fatal, stress-induced malignant hyperthermia in two unrelated families. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:938–945. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182320068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobin JR, Jason DR, Challa VR, Nelson TE, Sambuughin N. Malignant hyperthermia and apparent heat stroke. JAMA. 2001;286:168–169. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson TE, Jones EW, Venable JH, Kerr DD. Malignant hyperthermia of Poland China swine: studies of a myogenic etiology. Anesthesiology. 1972;36:52–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones EW, Nelson TE, Anderson IL, Kerr DD, Burnap TK. Malignant hyperthermia of swine. Anesthesiology. 1972;36:52–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chelu MG, Goonasekera SA, Durham WJ, Tang W, Lueck JD, Riehl J, Pessah IN, Zhang P, Bhattacharjee MB, Dirksen RT, Hamilton SL. Heat- and anesthesia-induced malignant hyperthermia in an RyR1 knock-in mouse. FASEB J. 2006;20:329–330. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4497fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang T, Riehl J, Esteve E, Matthaei KI, Goth S, Allen PD, Pessah IN, Lopez JR. Pharmacologic and functional characterization of malignant hyperthermia in the R163C RyR1 knock-in mouse. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1164–1175. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200612000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dainese M, Quarta M, Lyfenko AD, Paolini C, Canato M, Reggiani C, Dirksen RT, Protasi F. Anesthetic- and heat-induced sudden death in calsequestrin-1-knockout mice. FASEB J. 2009;23:1710–1720. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-121335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Protasi F, Paolini C, Dainese M. Calsequestrin-1: a new candidate gene for malignant hyperthermia and exertional/environmental heat stroke. J Physiol. 2009;587:3095–3100. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paolini C, Quarta M, Nori A, Boncompagni S, Canato M, Volpe P, Allen PD, Reggiani C, Protasi F. Reorganized stores and impaired calcium handling in skeletal muscle of mice lacking calsequestrin-1. J Physiol. 2007;583:767–784. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canato M, Scorzeto M, Giacomello M, Protasi F, Reggiani C, Stienen GJ. Massive alterations of sarcoplasmic reticulum free calcium in skeletal muscle fibers lacking calsequestrin revealed by a genetically encoded probe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22326–22331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009168108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paolini C, Quarta M, D’Onofrio L, Reggiani C, Protasi F. Differential effect of calsequestrin ablation on structure and function of fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. J Biomed Biotech. 2011:634075. doi: 10.1155/2011/634075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yarotskyy V, Protasi F, Dirksen RT. Accelerated Activation of SOCE Current in Myotubes from Two Mouse Models of Anesthetic- and Heat-Induced Sudden Death. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraeva N, Zvaritch E, Frodis W, Sizova O, Kraev A, MacLennan DH, Riazi S. CASQ1 gene is an unlikely candidate for malignant hyperthermia susceptibility in the North American population. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:344–9. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000530185.78660.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Durham WJ, Aracena-Parks P, Long C, Rossi AE, Goonasekera SA, Boncompagni S, Galvan DL, Gilman CP, Baker MR, Shirokova N, Protasi F, Dirksen R, Hamilton SL. RyR1 S-nitrosylation underlies environmental heat stroke and sudden death in Y522S RyR1 knockin mice. Cell. 2008;133:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brocca L, Pellegrino MA, Desaphy JF, Pierno S, Camerino DC, Bottinelli R. Is oxidative stress a cause or consequence of disuse muscle atrophy in mice? A proteomic approach in hindlimb-unloaded mice. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:331–50. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.050245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connolly AM, Keeling RM, Metha S, Pestronk A, Sanes JR. Three mouse models of muscular dystrophy: the natural history of strength and fatigue in dystrophin- dystrophin/utrophin-, and laminin alpha2-deficient mice. Neuromusc Disord. 2001;11:703–712. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(01)00232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boncompagni S, Rossi AE, Micaroni M, Hamilton SL, Dirksen RT, Franzini-Armstrong C, Protasi F. Characterization and temporal development of cores in a mouse model of malignant hyperthermia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21996–22001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911496106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Defranchi E, Bonaccurso E, Tedesco M, Canato M, Pavan E, Raiteri R, Reggiani C. Imaging and elasticity measurements of the sarcolemma of fully differentiated skeletal muscle fibres. Microsc Res Tech. 2005;67:27–35. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei L, Salahura G, Boncompagni S, Kasischke KA, Protasi F, Sheu SS, Dirksen RT. Mitochondrial superoxide flashes: metabolic biomarkers of skeletal muscle activity and disease. FASEB J. 2011;25:3068–3078. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman I, Kode A, Biswas SK. Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:3159–3165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCord JM, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein) J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogino K, Wang DH. Biomarkers of oxidative/nitrosative stress: an approach to disease prevention. Acta Med Okayama. 2007;61:181–9. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asensi M, Sastre J, Pallardo FV, Lloret A, Lehner M, Garcia-de-la Asuncion J, Viña J. Ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione as indicator of oxidative stress status and DNA damage. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)99026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Disatnik MH, Dhawan J, Yu Y, Beal MF, Whirl MM, Franco AA, Rando TA. Evidence of oxidative stress in mdx mouse muscle: studies of the pre-necrotic state. J Neurol Sci. 1998;161:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lawler JM, Song W, Demaree SR. Hindlimb unloading increases oxidative stress and disrupts antioxidant capacity in skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahoney DJ, Kaczor JJ, Bourgeois J, Yasuda N, Tarnopolsky MA. Oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme upregulation in SOD1-G93A mouse skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 2006;33:809–16. doi: 10.1002/mus.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abruzzo PM, di Tullio S, Marchionni C, Belia S, Fanó G, Zampieri S, Carraro U, Kern H, Sgarbi G, Lenaz G, Marini M. Oxidative stress in the denervated muscle. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:563–76. doi: 10.3109/10715761003692487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Protasi F, Paolini C, Canato M, Reggiani C, Quarta M. Lessons from calsequestrin-1 ablation in vivo: much more than a Ca2+ buffer after all. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2011;32:257–270. doi: 10.1007/s10974-011-9277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galli L, Orrico A, Lorenzini S, Censini S, Falciani M, Covacci A, Tegazzin V, Sorrentino V. Frequency and localization of mutations in the 106 exons of the RYR1 gene in 50 individuals with malignant hyperthermia. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:830. doi: 10.1002/humu.9442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson R, Carpenter D, Shaw MA, Halsall J, Hopkins P. Mutations in RYR1 in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:977–989. doi: 10.1002/humu.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monnier N, Procaccio V, Stieglitz P, Lunardi J. Malignant-hyperthermia susceptibility is associated with a mutation of the alpha 1-subunit of the human dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type voltage-dependent calcium-channel receptor in skeletal muscle. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:1316–1325. doi: 10.1086/515454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carpenter D, Ringrose C, Leo V, Morris A, Robinson RL, Halsall PJ, Hopkins PM, Shaw MA. The role of CACNA1S in predisposition to malignant hyperthermia. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi D, Vezzani B, Galli L, Paolini C, Toniolo L, Pierantozzi E, Spinozzi S, Barone V, Pegoraro E, Bello L, Cenacchi G, Vattemi G, Tomelleri G, Ricci G, Siciliano G, Protasi F, Reggiani C, Sorrentino V. A mutation in the CASQ1 gene causes a vacuolar myopathy with accumulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum protein aggregates. Hum Mutat. 2014;35:1163–70. doi: 10.1002/humu.22631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson TE, Bedell DM, Jones EW. Porcine malignant hyperthermia: Effects of temperature and extracellular calcium concentration on halothane-induced contracture of susceptible skeletal muscle. Anesthesiology. 1975;42:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fletcher JE, Huggins FJ, Rosenberg H. The importance of calcium ions for in vitro malignant hyperthermia testing. Can J Anaesth. 1990;37:695–698. doi: 10.1007/BF03006495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adnet PJ, Krivosic-Horber RM, Adamantidis MM, Reyford H, Cordonnier C, Haudecoeur G. Effects of calcium-free solution, calcium antagonists, and the calcium agonist BAY K 8644 on mechanical responses of skeletal muscle from patients susceptible to malignant hyperthermia. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:413–419. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyfenko AD, Dirksen RT. Differential dependence of store-operated and excitation-coupled Ca2+ entry in skeletal muscle on STIM1 and Orai1. J Physiol. 2008;586:4815–4824. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.160481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei-Lapierre L, Carrell EM, Boncompagni S, Protasi F, Dirksen RT. Orai1-dependent calcium entry promotes skeletal muscle growth and limits fatigue. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2805. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duke AM, Hopkins PM, Calaghan SC, Halsall JP, Steele DS. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in malignant hyperthermia-susceptible human skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25645–25653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beard NA, Sakowska MM, Dulhunty AF, Laver DR. Calsequestrin is an inhibitor of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor calcium release channels. Biophys J. 2002;82:310–320. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Royer L, Sztretye M, Manno C, Pouvreau S, Zhou J, Knollmann BC, Protasi F, Allen PD, Ríos E. Paradoxical buffering of calcium by calsequestrin demonstrated for the calcium store of skeletal muscle. J Gen Physiol. 2010;136:325–338. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomasi M, Canato M, Paolini C, Dainese M, Reggiani C, Volpe P, Protasi F, Nori A. Calsequestrin (CASQ1) rescues function and structure of calcium release units in skeletal muscles of CASQ1-null mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C575–586. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00119.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eu JP, Sun J, Xu L, Stamler JS, Meissner G. The skeletal muscle calcium release channel: coupled O2 sensor and NO signaling functions. Cell. 2000;102:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun J, Xin C, Eu JP, Stamler JS, Meissner G. Cysteine-3635 is responsible for skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor modulation by NO. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11158–11162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201289098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun J, Xu L, Eu JP, Stamler JS, Meissner G. Nitric oxide, NOC-12, and S-nitrosoglutathione modulate the skeletal muscle calcium release channel/ryanodine receptor by different mechanisms. An allosteric function for O2 in S-nitrosylation of the channel. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8184–8189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bellinger AM, Reiken S, Carlson C, Mongillo M, Liu X, Rothman L, Matecki S, Lacampagne A, Marks AR. Hypernitrosylated ryanodine receptor calcium release channels are leaky in dystrophic muscle. Nat Med. 2009;15:325–330. doi: 10.1038/nm.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Narkar VA, Downes M, Yu RT, Embler E, Wang YX, Banayo E, Mihaylova MM, Nelson MC, Zou Y, Juguilon H, Kang H, Shaw RJ, Evans RM. AMPK and PPARdelta agonists are exercise mimetics. Cell. 2008;134:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Dagnino-Acosta A, Ainbinder A, Cheng Q, Joshi AD, Chen Z, Yarotskyy V, Oakes JM, Lee CS, Monroe TO, Santillan A, Dong K, Goodyear L, Ismailov II, Rodney GG, Dirksen RT, Hamilton SL. AICAR prevents heat-induced sudden death in RyR1 mutant mice independent of AMPK activation. Nat Med. 2012;18:244–251. doi: 10.1038/nm.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wedel DJ, Quinlan JG, Iaizzo PA. Clinical effects of intravenously administered dantrolene. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:241–246. doi: 10.4065/70.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szentesi P, Collet C, Sárközi S, Szegedi C, Jona I, Jacquemond V, Kovács L, Csernoch L. Effects of dantrolene on steps of excitation-contraction coupling in mammalian skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:355–375. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.4.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cherednichenko G, Ward CW, Feng W, Cabrales E, Michaelson L, Samso M, López JR, Allen PD, Pessah IN. Enhanced excitation-coupled calcium entry in myotubes expressing malignant hyperthermia mutation R163C is attenuated by dantrolene. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1203–1212. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao X, Weisleder N, Han X, Pan Z, Parness J, Brotto M, Ma J. Azumolene inhibits a component of store-operated calcium entry coupled to the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33477–33486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matuszczak Y, Farid M, Jones J, Lansdowne S, Smith MA, Taylor AA, Reid MB. Effects of N-acetylcysteine on glutathione oxidation and fatigue during handgrip exercise. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:633–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.20385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]