Summary

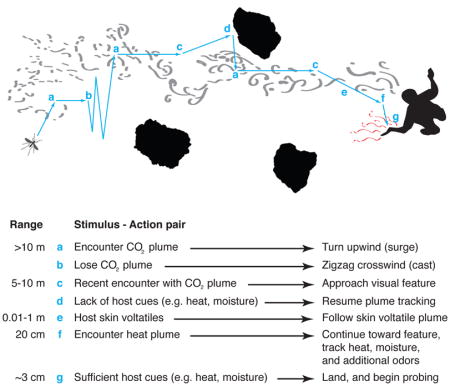

All moving animals, including flies [1–3], sharks [4], and humans [5], experience a dynamic sensory landscape that is a function of both their trajectory through space and the distribution of stimuli in the environment. This is particularly apparent for mosquitoes, which use a combination of olfactory, visual, and thermal cues to locate hosts [6–10]. Mosquitoes are thought to detect suitable hosts by the presence of a sparse CO2 plume, which they track by surging upwind and casting crosswind [11]. Upon approach, local cues such as heat and skin volatiles help them identify a landing site [12–15]. Recent evidence suggests that thermal attraction is gated by the presence of CO2 [6], although this conclusion was based experiments in which the actual flight trajectories of the animals were unknown and visual cues were not studied. Using a 3-dimensional tracking system we show that rather than gating heat sensing, the detection of CO2 actually activates a strong attraction to visual features. This visual reflex guides the mosquitoes to potential hosts where they are close enough to detect thermal cues. By experimentally decoupling the olfactory, visual, and thermal cues, we show that the motor reactions to these stimuli are independently controlled. Given that humans become visible to mosquitoes at a distance of 5–15 m [16], visual cues play a critical intermediate role in host localization by coupling long-range plume tracking to behaviors that require short-range cues. Rather than direct neural coupling, the separate sensory-motor reflexes are linked as a result of the interaction between the animal’s reactions and the spatial structure of the stimuli in the environment.

Graphical Abstract

Results

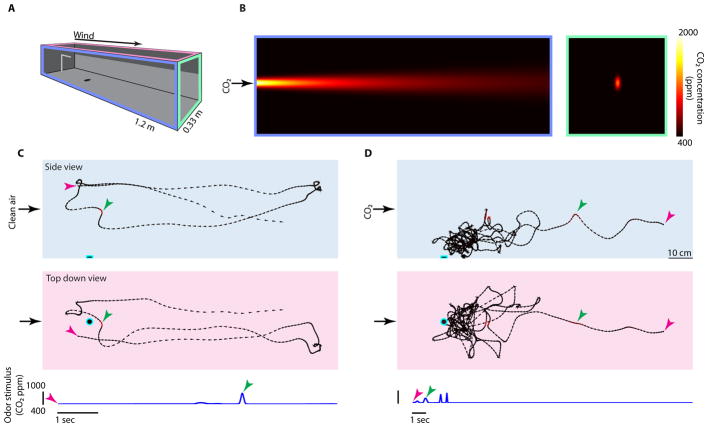

To study host-seeking behavior in Aedes aegypti, we released mated females in a wind tunnel with 40 cm sec−1 laminar flow and recorded over 20,000 flight trajectories (mean length > 6 sec) using a 3-dimensional real-time tracking system [17] (Figure 1a). We projected a low contrast checkerboard pattern on the entire floor of the tunnel, and placed one high contrast spot 20 cm from the upwind end (Figure S1a). After allowing the mosquitoes to acclimatize for an hour in clean air, which contained a background CO2 level of 400 ppm, we introduced a CO2 plume with a peak concentration of 2,500 ppm for three hours during the mosquitoes’ circadian activity peak. In separate experiments, we measured the CO2 concentration at 65 points in the tunnel and constructed a spatial model of the plume (Figure 1b and Figure S1b–c). When combined with our 3-dimensional tracking, the plume model made it possible to reconstruct the olfactory experiences of the mosquitoes along each individual trajectory [1] (see Methods for additional details). In control experiments, in which we injected clean air instead of CO2, the female mosquitoes did not exhibit plume-tracking behavior (Figures 1c and 2a, Figure S1). In the presence of the CO2 plume, the female mosquitoes showed stereotypical cast and surge behavior in response to CO2 concentrations greater than 500–600 ppm (Figure S2), as has been reported previously [11, 18].

Figure 1. Wind tunnel, CO2 plume, and example flight trajectories.

(A) Wind tunnel used in our experiments. Color borders indicate top, side, and upwind views used in subsequent panels.

(B) Heat map of a turbulent flow, particle diffusion model of the CO2 plume based on 65 measurements in the wind tunnel, see Methods and Figure S1 for details. The white dot indicates a mosquito, drawn to scale.

(C) Example flight trajectory in clean air. The two colored arrowheads show synchronized points across side and top views. The spacing between the points (33 Hz intervals) indicates the animal’s speed.

(D) Example flight trajectory in the presence of a CO2 plume, showing the mosquitoes’ stereotypical behavior exploring the high contrast object after sensing CO2. In both c and d, an estimate of the animal’s instantaneous CO2 (or control) experience is plotted below and color-coded within the trajectories using the scale in b. See Figure S1 for additional trajectories, and Supplemental Movie for animations.

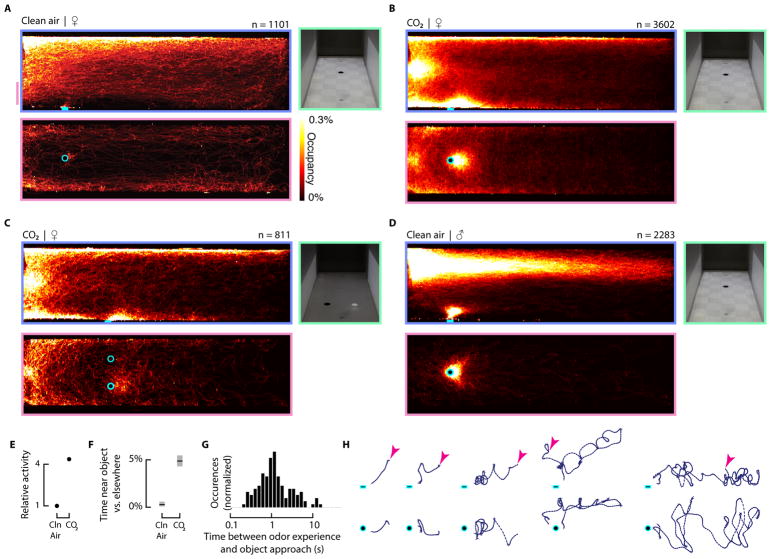

Figure 2. CO2 triggers mosquitoes to explore high contrast dark objects.

(A) Heat map showing where female mosquitoes spent their time over a three hour period. The top panel shows a side view of the data. The bottom panel shows a top down view of the data over the altitude range indicated by the vertical pink line in the top panel. The right panel shows a photograph of the wind tunnel.

(B) Same as a, but in the presence of a CO2 plume.

(C) Same as a, but in the presence of a CO2 plume and with a black and a white visual object on the floor of the tunnel.

(D) Same as a, but with male mosquitoes in clean air. We did not find any qualitative differences in male mosquitoes’ behavior in the presence of a CO2 plume (not shown).

(E) Relative flight activity, measured as the ratio of time mosquitoes spent flying in the presence of a CO2 or clean air plume compared to their prior activity.

(F) The ratio of the total time mosquitoes spent near the object divided by the total time they spent elsewhere for CO2 and clean air conditions. Shading shows bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the mean.

(G) Time elapsed between when mosquitoes left the plume (conservatively defined here as 401 ppm) and when they approached to within 3 cm of the object.

(H) Example trajectories (top row, side view; bottom row, top down view) that contributed to the histogram shown in g, demonstrating the circuitous path many mosquitoes took from the plume to the object. Only the trajectory segments between plume exit (pink arrow) and object approach are shown. See Figure S2 for a description of plume tracking behavior.

The most salient result of our experiments, however, was the influence of odor on the attractiveness of the visual object. When the female mosquitoes were exposed to clean air they explored the ceiling and walls of the wind tunnel, but rarely approached the visual feature. By contrast, when mosquitoes were exposed to the CO2 plume, they spent much of their time exploring the dark visual feature on the floor of the wind tunnel, despite its location approximately 10 cm below the CO2 plume (Figures 1d and 2b, Figure S1, and Supplemental Movie). The attraction to this visual feature persisted through the entire length of the 3-hour CO2 presentation (Figure S3). During these exploratory bouts, the mosquitoes hovered near the visual object at a distance of approximately 3 cm. These results are, to our knowledge, the first direct observation of odor-gated visual attraction in mosquitoes. In previous unpublished experiments, however, Richard Dow came to similar conclusions using trap assays without access to detailed knowledge of either the animals’ trajectories or the structure of the odor plume [10]. In experiments in which we provided both a bright white and a dark black object on a gray background, the mosquitoes only explored the dark object (Figure 2c), consistent with trap assays using wild mosquitoes [19–21]. In contrast to the female mosquitoes, males vigorously explored the visual feature in clean air (Figure 2d). In the presence of CO2, the males did not show any qualitative behavioral changes compared to their clean air responses, and did not exhibit any evidence of plume tracking behaviors. Thus, the influence of CO2 on the reaction to visual features appears to be a sex-specific behavior associated with blood foraging. In addition to plume tracking and object attraction, CO2 also elicited a significant increase in the general flight activity of females (Figure 2e). Averaged across all of the trajectories, the female mosquitoes spent close to 5% of their time near the visual object compared to all other parts of the wind tunnel (Figure 2f). Normalized for volume, the mosquitoes spent 10 times more time near the object than in the rest of the tunnel (8.8% / mm3 vs. 0.88% / mm3). They also spent much of their time in the vicinity of the tube through which CO2 was introduced into the tunnel. Although we tried to minimize the visual signature of this tube, it is likely that the mosquitoes could see it to some degree.

The visual object was placed 10 cm below the plume, at which distance the CO2 was not detectable using a sensitive meter (LI-6262 CO2/H2O analyzer, LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) and our spatial model based on measurements within the plume estimated a concentration at the floor that was no different from background levels. Thus, when the mosquitoes approached and explored the visual object they were not experiencing CO2 above the background. We calculated the time elapsed between leaving the plume and approaching the visual object for the 126 trajectories that contained continuous, un-fragmented data between these two events (Figure 2g). Some mosquitoes approached the object immediately after leaving the CO2 plume, whereas others took circuitous paths in which more than 10 seconds elapsed before reaching the object (Figure 2h). Many of the mosquitoes that approached the visual feature continued to explore the area for another 10 or more seconds without reencountering the plume (see Supplemental Movie). These results indicate that attraction to visual features can be triggered by a brief prior exposure to odor and does not require simultaneous experience of the two cues. Our estimates are necessarily conservative because our tracking system cannot reliably maintain the identities of individual mosquitoes over periods longer than 10–20 seconds.

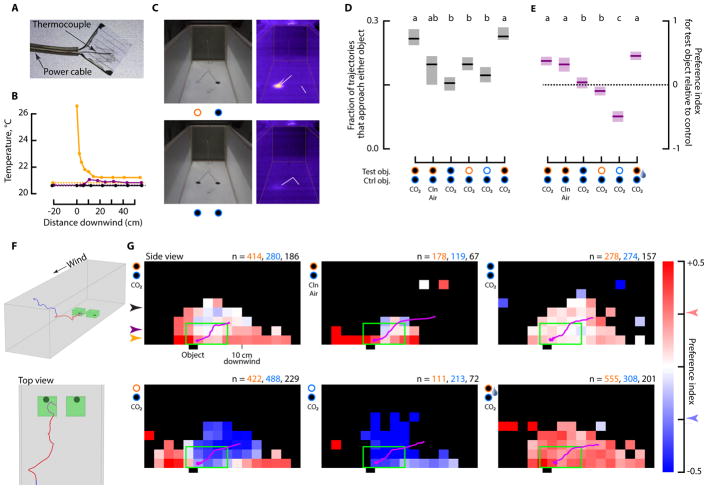

Odor-induced visual attraction could be one mechanism by which mosquitoes first navigate toward and localize potential hosts, but other cues, such as warmth, might also aid in the final stages of foraging. To investigate the potential interaction between vision and CO2-gated thermal attraction described in a previous study [6], we constructed two transparent objects from ITO (indium tin oxide) coated glass, which could be heated to a desired temperature (Figure 3a). We could independently manipulate the thermal and visual features of the stimulus by placing a long-pass gel filter over the glass. Such a filter appears dark to the mosquitoes but transparent to our cameras (Figure 3b–c). In each experiment, we presented the mosquitoes with two objects: a dark room temperature control object, and a test object that was either dark or nearly invisible, and either room temperature or heated to 37° C (Figure 3d–e). When presented with two dark objects, one of which was warm, the female mosquitoes showed a significant preference for the warm object (p<0.01). Although fewer mosquitoes approached either object in clean air, those that did showed a preference for the warm object that was not different than in the presence of a CO2 plume (p<0.01), indicating that CO2 does not appear to directly gate the attraction to warm objects. Significantly more mosquitoes approached the warm high-contrast object than the warm nearly invisible object. This result shows that attraction to visual features increases the probability of localizing a warm object. However, more mosquitoes found the warm nearly invisible object than a room temperature nearly invisible object, indicating that thermal signals can provide an independent source of information about the location of potential hosts.

Figure 3. Visual stimuli provide an intermediate cue, linking long range olfactory cues and short range heat sensing.

(A) Photograph of the ITO coated glass pad.

(B) Measurements of the thermal plume created by the heated glass pads at 0.5, 2.5, and 6.5 cm altitude, colored orange, purple, and black, respectively.

(C) Photographs and thermal images of the stimuli in the wind tunnel.

(D) Mean fraction of trajectories that entered an 8×8×4 cm3 volume above and downwind of either the left or right object (see f). Shading indicates 95% confidence intervals. The letters at the top indicate significantly different groups (Mann-Whitney u-test with Bonferoni correction, p=0.01).

(E) Mean preference index for the test object vs. control object with 95% confidence intervals, statistics calculated as in d.

(F) Sample trajectory entering one of the test volumes (green) used in d-e. The trajectory is color-coded red for the 2 seconds prior to when it entered the volume.

(G) Spatial representation of preference index prior to when mosquitoes entered either test volume shown in f. For each trajectory, we selected the segments 2 seconds prior to when they entered either volume, in addition to the portions spent inside the volumes (red region of the trajectory shown in f). We then calculated the preference index for each 2×2 cm2 rectangular region as the amount of time spent on the side of the wind tunnel of the test object compared to the control object, divided by their sum. We then calculated the mean preference index for each 2×2 cm2 region across all trajectories, and its 95% confidence interval. Colors indicate preference index for regions where the 95% confidence interval was smaller than 0.5 (out of the total range of −1 to +1); the regions with higher uncertainty are shown in black. A blue or pink color that is more saturated than the arrows on the scale bar represent regions where the mosquitoes showed a statistically significant preference for one side or the other. The average approach trajectory for all the mosquitoes in each trial is shown as a magenta line. Because the average approach trajectories to the two objects were indistinguishable, this line shows the average approach of all trajectories for simplicity. The light green box shows a side view of the volumes shown in f. The colored arrows indicate the altitudes at which the temperature of the air was measured in b. The number of trajectories that approached the test (orange), control (blue), or both (black) objects is indicated in the top right of each panel.

The data shown in Figure 3e provide only a simplified view of the behavioral algorithm used by the mosquitoes. To indicate how the visual and thermal cues influence behavior on a finer spatial scale, we constructed a preference index as a function of tunnel position for the two seconds before the mosquitoes approached either object (Figure 3f–g). On average, mosquitoes initially approached the objects without encountering the heat plume, which was only detectable 2–3 cm above the floor of the tunnel (Figure 3b). The mosquitoes that approached the object from just above the floor did, however, show a preference for the warm object from as far away as 20 cm.

Water vapor from rapidly evaporated perspiration has been attributed as another cue mediating host-seeking behavior in mosquitoes [12]. To investigate the possible role of water vapor on host localization in combination with visual and thermal cues, we placed a small petri dish containing a moist KimWipe over each glass pad in combination with the infrared pass filter that provides the visual cue. In this case, mosquitoes showed a significantly stronger response to the warm object at altitudes of 6–8 cm, rather than the narrow 2 cm region above the floor in which mosquitoes responded to the heat plume without H2O (p<0.01) (Figure 3g). These results suggest that the secondary effect of increased humidity over a warm object may be a more important cue than the temperature of the object itself. This behavior would help mosquitoes differentiate warm radiant objects, such as dark rocks heated by the sun, from animals, which increase the humidity around them when perspiring [12].

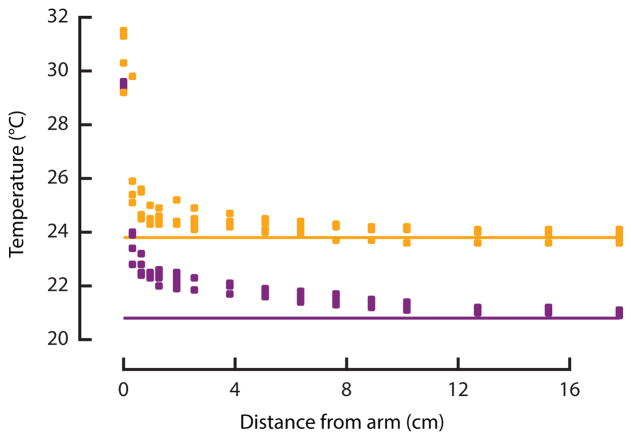

To determine the spatial scale over which thermal cues could realistically be detected by a mosquito, we measured the temperature downwind of a human arm in our laminar flow wind tunnel at ambient temperatures of 20.8° C and 23.8° C (Figure 4). These temperatures are representative of the typical range in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [22], during the months of highest Dengue fever transmission by Aedes [23]. At a distance of 10–15 cm, the difference between the heat plume and ambient temperature falls below 0.2° C, the detection threshold for Aedes [13]. Although mosquitoes can only see with an angular resolution of 4–8° [16], this would still allow them to detect a human arm at 30–50 cm, three times the distance at which they might detect a heat signature. In still air conditions, such as those found in a home, the heat plume would likely dissipate even more quickly. Thus, visual features are likely to provide useful cues over a much greater distance than thermal plumes.

Figure 4.

Temperature downwind (0.4 m/s) of a human arm measured at two different ambient temperatures (orange and purple). Horizontal lines indicate the ambient temperatures.

Discussion

In our experiments, we deliberately created a simple continuous odor plume so that we could register it with the mosquitoes’ reactions. Under more natural conditions, however, CO2 would move with the wind in intermittent packets of high concentration interspersed with background air [24]. The intermittent structure of natural plumes will cause an animal to experience a brief puff of odor, and then nothing for seconds, or even minutes [24–26]. Visual cues, however, are constant and effective from any angle, regardless of wind direction and turbulence. After experiencing a short CO2 exposure, mosquitoes may encounter a visual feature that might be the odor’s source. It thus makes sense that the attraction to visual features is triggered by a brief encounter with a chemical cue, but persists for many seconds following the exposure. This feature of the behavior is a natural consequence of the physics of natural plumes and makes clear predictions for the time constants of the underlying neural circuits. The time course of the CO2-induced visual attraction that we observed is similar to that recently demonstrated for a change in the gain of the optomotor response in Drosophila following exposure to an attractive odor [27]. Odor-gated attraction to visual features has also been observed in other insects such as fruit flies [1] and hawk moths [28], which suggests that this type of behavioral coupling may be a general and ancient strategy employed by insects for food search. Many vertebrates also track intermittent odor plumes to locate food [4, 5], suggesting that they, too, must integrate chemical and visual cues with long interaction delays, as opposed to the 100 ms time scales typically considered in multimodal sensory integration [29].

Our results are consistent with a scheme in which host seeking behavior emerges from a simple series of reflexes that are sequentially triggered according to the spatial scale over which the sensory cues can be detected. In the presence of an attractive odor such as CO2, mosquitoes become more active, follow the plume upwind using an iterative sequence of cast and surge reflexes. The distance at which mosquitoes first detect the CO2 plume created by a human has not been precisely measured. However, a study that artificially released CO2 at 4 L/min (roughly equivalent to that produced by a large bovine) found that the plume was detectable above background at a distance of 60 m in a riverine habitat [30]. The results reported here show that the detection of CO2 triggers the exploration of high contrast visual features, and a human figure would become visible to mosquitoes at distance of roughly 5–15 m [16], depending on the lighting conditions. This behavior will direct mosquitoes towards a potential host, at which point heat, humidity, and other olfactory cues [15, 31–35] may guide the final approach and the decision whether or not to land. At these intermediate distances human skin volatiles are likely to play an important role, as demonstrated in a recent study which showed that when presented with separate plumes of CO2 and human skin volatiles, Aedes followed the skin volatiles rather than the CO2 [15]. This might direct mosquitoes to an appropriate landing site on the body surface – such as the feet or ankles - rather than following the CO2 plume to the mouth. In the same study, exposure to a CO2 plume did not induce mosquitoes to land on dark beads whereas they did land on beads coated with human odor [15]. The most likely explanation for the discrepancy between these prior observations and our own results is that the visual contrast generated by the small dark beads on a dark background may have been insufficient to elicit the visual attracted that we observed.

In our proposed scheme, the behavioral modules employed by mosquitoes to find a host are both independent and interacting. The modules are independent from one another in the sense that mosquitoes may bypass individual steps in the sequence. For example, if mosquitoes happen to fly near a warm object without having previously encountered CO2, they may still approach the object and land. The behavioral modules may also interact with one another indirectly. For example, the influence of CO2 on both arousal and visual feature attraction will greatly increase the probability that mosquitoes come close enough to a host to detect its thermal plume.

For a human hoping to avoid being bitten by a mosquito, our results underscore a number of unfortunate realities. Even if it were possible to hold one’s breath indefinitely, another human breathing nearby, or several meters upwind, would create a CO2 plume that could lead mosquitoes close enough to you that they may lock on to your visual signature. The strongest defense is therefore to become invisible, or at least visually camouflaged. Even in this case, however, mosquitoes could still locate you by tracking the heat signature of your body provided they get close enough. The independent and iterative nature of the sensory-motor reflexes renders mosquitoes’ host seeking strategy annoyingly robust.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti, standard laboratory Rockefeller strain [18, 36]) were raised in groups of 100, and cold-anesthetized to sort males from females after cohabitating for 6–8 days. At this time, more than 90% of the females have typically mated, as indicated by their developing embryos. Three hours prior to their subjective sunset, we released 20 females into the wind tunnel. Two hours prior to sunset, the CO2 plume (or air in control experiments) was automatically switched on for 3 hours. The wind tunnel and tracking system have been described in detail previously [1, 17].

CO2 plume calibration

In order to calculate the olfactory experience of each trajectory, we measured the CO2 concentration inside the wind tunnel at 65 different locations with a LI-6262 CO2/H2O analyzer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE), and constructed a model based on particle diffusion in turbulent flow (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures).

Trajectory analysis

Details on the tracking software [17] and general camera setup for this particular system [1] are provided elsewhere. Because our tracking system is unable to maintain identities for extended periods of time, individual traces were considered independent for the sake of statistical analysis. We restricted all of our analysis to trajectories that were at least 150 frames (1.5 seconds) long. The average length of the trajectories was approximately 6 seconds, with some trajectories reaching 85 seconds. In total, we collected over 20,000 trajectories over the course of our experiments.

Data for the heated object experiments in Figure 3, as well as in Figure 2a, were collected with 60 individual mosquitoes over three trials per experimental condition, yielding between 1101 and 3433 trajectories for each condition. Data in Figure 2b were collected with 120 individuals over six trials, yielding 3602 trajectories. Data for Figures 2c–d did not require statistical analyses and were collected with 20 individuals over one session due to equipment access constraints, and yielded 811 and 2,283 trajectories for the two conditions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A mosquito’s perception of CO2 triggers a strong attraction to visual features.

A mosquito’s attraction to thermal targets is independent of the presence of CO2.

Olfaction, vision, and heat trigger independent host seeking behavioral modules.

Interactions among behavioral modules underlie multimodal sensory integration.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Straw for help with the 3D tracking software, C. Vinauger and B. Nguyen for help with raising the mosquitos, and members of the Dickinson lab for experimental and manuscript feedback. This work was funded by NIH grant NIH1RO1DCO13693-01.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, three figures, and one movie, and can be found online.

Author Contributions F.v.B. carried out all the experiments and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the experimental design, and interpretation of the data. F.v.B and M.H.D. together produced the figures and wrote the manuscript, with help from J.R. and A.F.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Van Breugel F, Dickinson MH. Plume-tracking behavior of flying Drosophila emerges from a set of distinct sensory-motor reflexes. Curr Biol. 2014;24:274–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budick SA, Dickinson MH. Free-flight responses of Drosophila melanogaster to attractive odors. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:3001–17. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrows WM. The reactions of the Pomace fly, Drosophila ampelophila loew, to odorous substances. J Exp Zool. 1907;4:515–537. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnsen PB, Teeter JH. Behavioral responses of bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo) to controlled olfactory stimulation. Mar Freshw Behav Phy. 1985;11:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter J, Craven B, Khan RM, Chang SJ, Kang I, Judkewitz B, Judkewicz B, Volpe J, Settles G, Sobel N. Mechanisms of scent-tracking in humans. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:27–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMeniman CJ, Corfas RA, Matthews BJ, Ritchie SA, Vosshall LB. Multimodal integration of carbon dioxide and other sensory cues drives mosquito attraction to humans. Cell. 2014;156:1060–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ditzen M, Pellegrino M, Vosshall LB. Insect odorant receptors are molecular targets of the insect repellent DEET. Science (80-) 2008;319:1838–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1153121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeGennaro M, McBride CS, Seeholzer L, Nakagawa T, Dennis EJ, Goldman C, Jasinskiene N, James AA, Vosshall LB. orco mutant mosquitoes lose strong preference for humans and are not repelled by volatile DEET. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner SL, Li N, Guda T, Githure J, Cardé RT, Ray A. Ultra-prolonged activation of CO2-sensing neurons disorients mosquitoes. Nature. 2011;474:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature10081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bidlingmayer WL. How mosquitoes see traps: role of visual responses. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1994;10:272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dekker T, Cardé RT. Moment-to-moment flight manoeuvres of the female yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti L) in response to plumes of carbon dioxide and human skin odour. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:3480–94. doi: 10.1242/jeb.055186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eiras AE, Jepson PC. Responses of female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) to host odours and convection currents using an olfactometer bioassay. Bull Entomol Res. 1994;84:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis E, Sokolove P. Temperature responses of antennal receptors of the mosquito, Aedes aegypti. J Comp Physiol. 1975;96:223–236. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang G, Qiu YT, Lu T, Kwon HW, Pitts RJ, Van Loon JJa, Takken W, Zwiebel LJ. Anopheles gambiae TRPA1 is a heat-activated channel expressed in thermosensitive sensilla of female antennae. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:967–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacey ES, Ray A, Cardé RT. Close encounters: Contributions of carbon dioxide and human skin odour to finding and landing on a host in Aedes aegypti. Physiol Entomol. 2014;39:60–68. doi: 10.1111/phen.12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bidlingmayer WL, Hem DG. The range of visual attraction and the effect of competitive visual attractants upon mosquito (Diptera: Culicidae) flight. Bull Entomol Res. 1980;70:321–342. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straw AD, Branson K, Neumann TR, Dickinson MH. Multi-camera real-time three-dimensional tracking of multiple flying animals. J R Soc Interface. 2011;8:395–409. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2010.0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dekker T, Geier M, Cardé RT. Carbon dioxide instantly sensitizes female yellow fever mosquitoes to human skin odours. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:2963–72. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson G, Torr SJ. Visual and olfactory responses of haematophagous Diptera to host stimuli. Med Vet Entomol. 1999;13:2–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.1999.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muir L, Kay B, Thorne M. Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Vision: Response to Stimuli from the Optical Environment. J Med Entomol. 1992;29:445–450. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/29.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Browne S, Bennett G. Response of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to visual stimuli. J Med Entomol. 1981;18:505–521. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/18.6.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Weather Online. [Accessed January 1, 2015]; Available at: http://www.worldweatheronline.com/Rio-De-Janeiro-weather-averages/Rio-De-Janeiro/BR.aspx.

- 23.Chan EH, Sahai V, Conrad C, Brownstein JS. Using web search query data to monitor dengue epidemics: a new model for neglected tropical disease surveillance. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murlis J, Willis MA, Carde RT. Spatial and temporal structures of pheromone plumes in fields and forests. Physiol Entomol. 2000;25:211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murlis J, Elkinton JS, Carde RT. Odor plumes and how insects use them. Annu Rev Entomol. 1992;37:505–532. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riffell JA, Abrell L, Hildebrand JG. Physical processes and real-time chemical measurement of the insect olfactory environment. J Chem Ecol. 2008;34:837–53. doi: 10.1007/s10886-008-9490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasserman SM, Aptekar JW, Larsen C, Frye Ma, Wasserman SM, Aptekar JW, Lu P, Nguyen J, Wang AL, Keles MF, et al. Olfactory Neuromodulation of Motion Vision Circuitry in Drosophila Olfactory Neuromodulation of Motion Vision Circuitry in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raguso RA, Willis MA. Synergy between visual and olfactory cues in nectar feeding by naïve hawkmoths, Manduca sexta. Anim Behav. 2002;64:685–695. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein BE, Stanford TR. Multisensory integration: current issues from the perspective of the single neuron. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:255–266. doi: 10.1038/nrn2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zöllner GE, Torr SJ, Ammann C, Meixner FX. Dispersion of carbon dioxide plumes in African woodland: implications for host-finding by tsetse flies. Physiol Entomol. 2004;29:381–394. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dekker T, Takken W, Carde RT. Structure of host-odour plumes influences catch of Anopheles gambiae s. s and Aedes aegypti in a dual-choice olfactometer. Physiol Entomol. 2001;26:124–134. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dekker T, Steib B, Carde RT, Geier M. L-lactic acid: a human-signifying host cue for the anthropophilic mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16:91–98. doi: 10.1046/j.0269-283x.2002.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geier M, Sass H, Boeckh J. A search for components in human body odour that attract females of Aedes. Olfaction mosquito-host Interact. 1996;781:132. doi: 10.1002/9780470514948.ch11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skinner WA, Tong H. Human sweat components attractive to mosquitoes. Nature. 1965;207:661–662. doi: 10.1038/207661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besansky NJ, Hill Ca, Costantini C. No accounting for taste: host preference in malaria vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:249–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tauxe GM, Macwilliam D, Boyle SM, Guda T, Ray A. Targeting a dual detector of skin and CO2 to modify mosquito host seeking. Cell. 2013;155:1365–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.