Summary

Cell-based therapies to treat retinal degeneration are now being tested in clinical trials. However, it is not known if the source of stem cells is important for the production of differentiated cells suitable for transplantation. To test this, we generated iPSCs murine rod photoreceptors (r-iPSCs) and scored their ability to make retina using a standardized quantitative protocol called STEM-RET. We discovered that r-iPSCs were more efficient at producing differentiated retina than embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or fibroblast-derived iPSCs (f-iPSCs). Retinae derived from f-iPSCs had a reduction in amacrine cells and other inner nuclear layer cells. Integrated epigenetic analysis showed that DNA methylation contributes to the defects in f-iPSC retinogenesis and that rod specific CTCF insulator protein binding sites may promote retinogenes in r-iPSCs. Taken together, our data suggest that the source of stem cells are important for producing retinal neurons in 3D organ cultures.

Introduction

Retinal degeneration affects millions of people each year worldwide and cell-based therapies are now being tested for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), Stargardt’s disease and retinitis pigmentosa (Cramer and MacLaren, 2013; Ramsden et al., 2013). For example, embryonic stem cell (ESC)–based therapies to replace retinal pigmented epithelial cells are currently in clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers NCT01691261, NCT01344993, and NCT01345006), and preclinical studies have demonstrated the feasibility of similar approaches to replace photoreceptors lost to retinal degeneration (MacLaren et al., 2006; Pearson et al., 2012).

Both ESCs and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have been shown to produce RPE and photoreceptors in culture (Buchholz et al., 2009; Eiraku et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2009; Nakano et al., 2012; Zhong et al., 2014) but there are important differences between these stem cell populations that may have a significant impact on cell transplantation. For example, individual iPSC lines may retain epigenetic marks of the differentiated cells they were derived from, which in turn may influence their efficiency to produce different lineages (Kim et al., 2010). Indeed, iPSCs derived from primary human fetal retinal pigmented epithelial (RPE) cells can retain memory of their previous differentiation state and exhibited a preference to redifferentiate into RPE (Hu et al., 2010). In some iPSC lines, this epigenetic memory is reduced with each passage in culture (Kim et al., 2010) but it is possible that some forms of epigenetic memory are more stable and can be exploited in selecting iPSC lines for stem cell based therapies (Hargus et al., 2014). To date, most studies of epigenetic memory in iPSCs have focused on DNA methylation but higher order chromatin organization mediated by insulator element such as CTCF may also play a role in iPSC epigenetic memory (Narendra et al., 2015).

Sasai and coworkers showed that eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation can be achieved in three-dimensional (3D) cultures of human and mouse ESCs (Eiraku and Sasai, 2012a; Eiraku and Sasai, 2012b; Eiraku et al., 2011; Nakano et al., 2012). A more recent study that used a modification of the Sasai protocol showed that human iPSCs derived from fibroblasts can also produce retinae (Zhong et al., 2014). However, it is not known if the source of stem cells is important for retinal differentiation, functional integration and survival when transplanted (Assawachananont et al., 2014; Gonzalez-Cordero et al., 2013).

In this study, we compared the retinal differentiation of iPSCs derived from murine fibroblasts and rod photoreceptors using a quantitative protocol for monitoring retinal development in culture called STEM-RET. We discovered that the source of iPSCs had a significant impact on the efficiency and structure of retinae formed in 3D organ cultures. By integrating the retinal differentiation data with epigenetic profiling, we identified a new mechanism that contributes to these differences between iPSC lines. Our results suggest that the source of stem cells for cellular transplantation in the retina may be an important consideration and we provide a platform for comparing the retinal differentiation and epigenetic memory of different stem cell populations.

Results

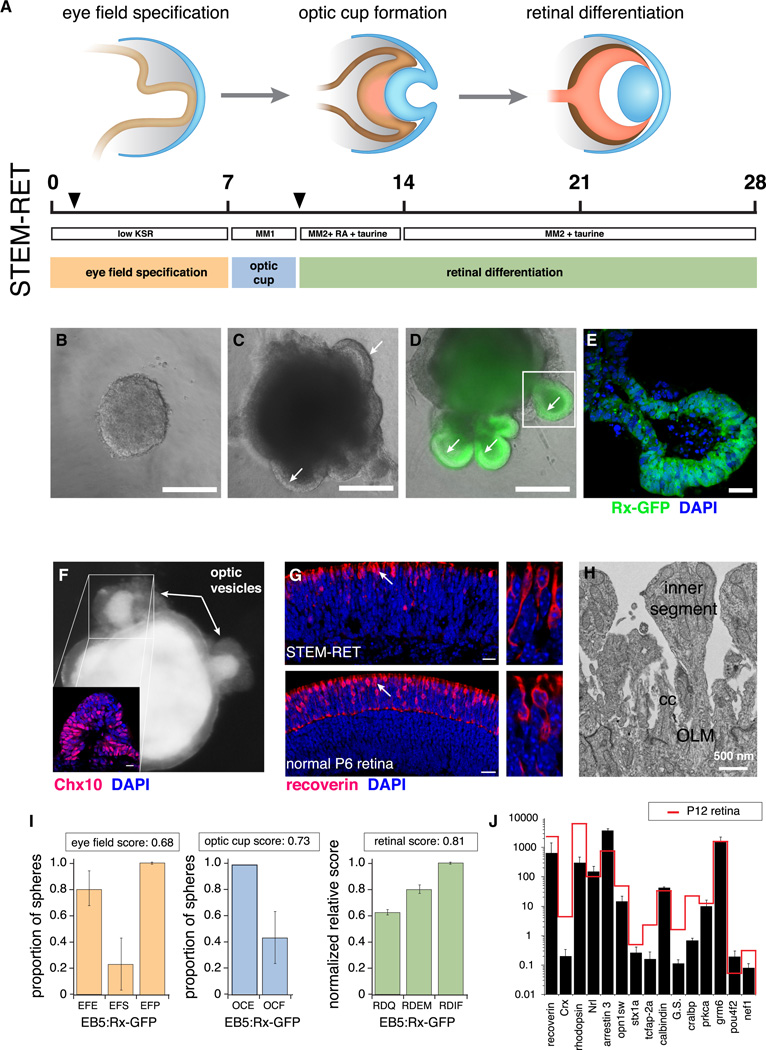

Quantitation of Retinogenesis from Murine ESCs

To quantitate retinogenesis from murine ESCs and iPSCs, we incorporated molecular, cellular, and morphologic scoring criteria into a quantitative STEM-RET protocol (Figure 1A). The timeline of STEM-RET corresponded to eye field specification during the first 7 days in culture, optic cup formation from days 7 to 10, and retinal differentiation from days 10 to 28 (Figure 1A). As a benchmark for STEM-RET, we used the EB5:Rx-GFP murine ESC line, which efficiently produces eye field, optic cup, and retinae in culture (Figures 1B–G and S1)(Eiraku et al., 2011). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis revealed the presence of several hallmarks of normal retinae in the tissue derived from murine ESCs, such as photoreceptor inner segments, outer limiting membranes, photoreceptor terminals, and other cellular features associated with the inner nuclear layer and ganglion cell layer (Figures 1H and S1).

Figure 1. Quantitation of retinal specification and differentiation by the STEM-RET protocol.

A) Timeline of the STEM-RET protocol corresponding to eye field specification (days 0–7), optic cup formation (days 7–10), and retinal differentiation (days 10–28). The arrowheads indicate additional manipulations. B) Micrograph of an embryonic stem cell (ESC) aggregate 24 h after plating at the time of addition of Matrigel. C) Micrograph of the ESC aggregate on day 4 in culture showing outcropping of the early eye fields (arrows). D) Micrograph of EB5:Rx-GFP on day 7 in culture with expression of the Rx-GFP transgene in the optic vesicles (arrows). E) Section through the optic cup shown in (D) with GFP expression (green fluorescence) and nuclei stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). F) Micrograph of optic vesicles at day 10 in culture just before isolating the retina for subsequent retinal differentiation culture. Chx10 immunofluorescence (red fluorescence) is shown in the lower left corner with nuclei stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). G) Section through a differentiated retina by using STEM-RET after 23 days in culture and immunostained for recoverin (red fluorescence) with nuclei stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). A normal P6 retina is shown for comparison. H) Electron micrograph of a STEM-RET–derived retina after 28 days of differentiation showing the outer limiting membrane (OLM), connecting cilium (cc), and photoreceptor inner segments. I) Histograms of scoring of eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation for the EB5:Rx-GFP ESC line. J) Representative histogram of qPCR using TaqMan® probes for retinal genes from STEM-RET–differentiated retinae using the EB5:Rx-GFP ESC line. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of duplicate PCR reactions, and each experiment was performed in triplicate. Data are normalized to Gapdh expression and plotted relative to normal P12 retinal expression. Scale bars: B-D: 200 µm; E,F:10 µm; G: 25 µm. Abbreviations: RA, retinoic acid; OLM, outer limiting membrane; cc, connecting cilium; EFE, eye field efficiency; EFS, eye field specificity; EFP, eye field proliferation; OCE, optic cup efficiency; OCF, optic cup frequency; RDQ, retinal differentiation q-PCR; RDEM, retinal differentiation electron microscopy; RDIF, retinal differentiation immunofluorescence. See also Fig. S1.

For eye field specification we scored eye field induction efficiency (EFE), eye field induction specificity (EFS), and eye field proliferation (EFP) at day 7 (Figure 1I). For optic cup formation, we scored optic cup efficiency (OCE) and optic cup frequency (OCF) at day 10 (Figure 1I). To measure retinal differentiation (days 10–28), we analyzed 15 retinal differentiation genes by quantitative PCR (qPCR) [retinal differentiation qPCR (RDQ)], 18 morphologic criteria by TEM [retinal differentiation electron microscopy (RDEM)], and 9 proteins by immunofluorescence on cryosections [retinal differentiation immunofluorescence (RDIF)] (Figure 1I and Table S1). For the RDQ score, the normalized expression of each gene relative to P12 murine retina was calculated and then those scores were averaged across all genes such that a score of 1.0 would be equivalent to mature retina. The immunostained sections and electron micrographs were scored blinded and the data were averaged such that a score of 1.0 would be equivalent to mature retina. To combine individual eye field (EFE, EFS and EFP), optic cup (OCE, OCF) and retinal differentiation (RDQ, RDIF, RDEM) scores into a single integrated score, an unweighted average was calculated. The EB5:Rx-GFP ESC line had integrated scores of 0.68 on eye field specification, 0.73 on optic cup formation, and 0.81 on retinal differentiation from 6 replicate experiments with more than 1,000 individual sphere cultures (Figures 1I, 1J and Tables 1, S1).

Table 1.

Stem cell lines used for STEM-RET.

| LINE | SOURCE | METHOD | TYPE | EF | OC | RD | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EB5 | RIKEN | n.a | ESC | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.41 |

| EB5:RxGFP | RIKEN | n.a. | ESC | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.75 |

| iPS7 | MEF | viral | iPSC | 0.52 | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.65 |

| iPS11 | MEFNrl−/− | viral | iPSC | 0.36 | 0.11 | n.a. | n.a. |

| FDN01 | MEFOKSM;Nrl−/− | OKSM | iPSC | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| FDN02 | MEFOKSM;Nrl−/− | OKSM | iPSC | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.60 | 0.46 |

| FNR01 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 0.58 |

| FNR02 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.39 | 0.7 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| FNR03 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| FNR04 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.44 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.54 |

| FNR05 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.48 | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.62 |

| FNR06 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| FNR07 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.42 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.57 |

| FNR08 | MEFOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.41 | 0.77 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| 8601 | (i)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.41 | 0.54 | 0.76 | 0.57 |

| 8602 | (i)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.44 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.69 |

| 8603 | (i)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.88 | 0.62 |

| 8604 | (i)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.48 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.64 |

| 7601 | (m)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.42 | 0.59 | 0.88 | 0.63 |

| 7602 | (m)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 0.61 |

| 3301 | (m)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.43 | 0.51 | 0.96 | 0.63 |

| 3302 | (m)rodOKSM | OKSM | iPSC | 0.33 | 0.60 | 0.86 | 0.60 |

| SCN150 | rodNrl-GFP | SCNT | ESC | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.44 |

| SCN194 | rodNrl-GFP | SCNT | ESC | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.41 |

| SCN212 | rodNrl-GFP | SCNT | ESC | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.19 | 0.37 |

Each line is listed along with the type of stem cell, cell source and method of reprogramming (viral, OKSM, SCNT). The integrated scores for eye field formation (EF), optic cup formation (OC) and retinal differentiation (RD) are shown along with the total combined score for each line. Some of the lines were produced from Nrl−/− MEFs as indicated. Abbreviations: OKSM: Oct3/4, Klf4, Sox2, c-Myc reprogrammable mouse; SCNT: somatic cell nuclear transfer perfomed on P6-P8 rods; (i)rod: immature rods at P2-P4; (m)rod: mature rods >P21.

Generation and Characterization of Stem Cell Lines

To determine if the source of stem cells can influence retinogenesis, we developed iPSC lines from embryonic fibroblasts (f-iPSCs) and rod photoreceptors (r-iPSCs) (Table 1). The f-iPSCs were produced with a mixture of retroviruses expressing Oct3/4, Klf4, and Sox2 or using a reprogrammable mouse strain (Col1a1-OKSM;Rosa26-M2rtTA)(Stadtfeld et al., 2010). We also generated f-iPSCs from Nrl−/− embryonic fibroblasts (Table 1). The Nrl gene encodes the neural retina-specific leucine zipper protein that is required for rod photoreceptor cell fate specification and differentiation (Mears et al., 2001). We produced Nrl−/− f-iPSCs to determine if the defects in photoreceptor development could be recapitulated in culture using STEM-RET (see below).

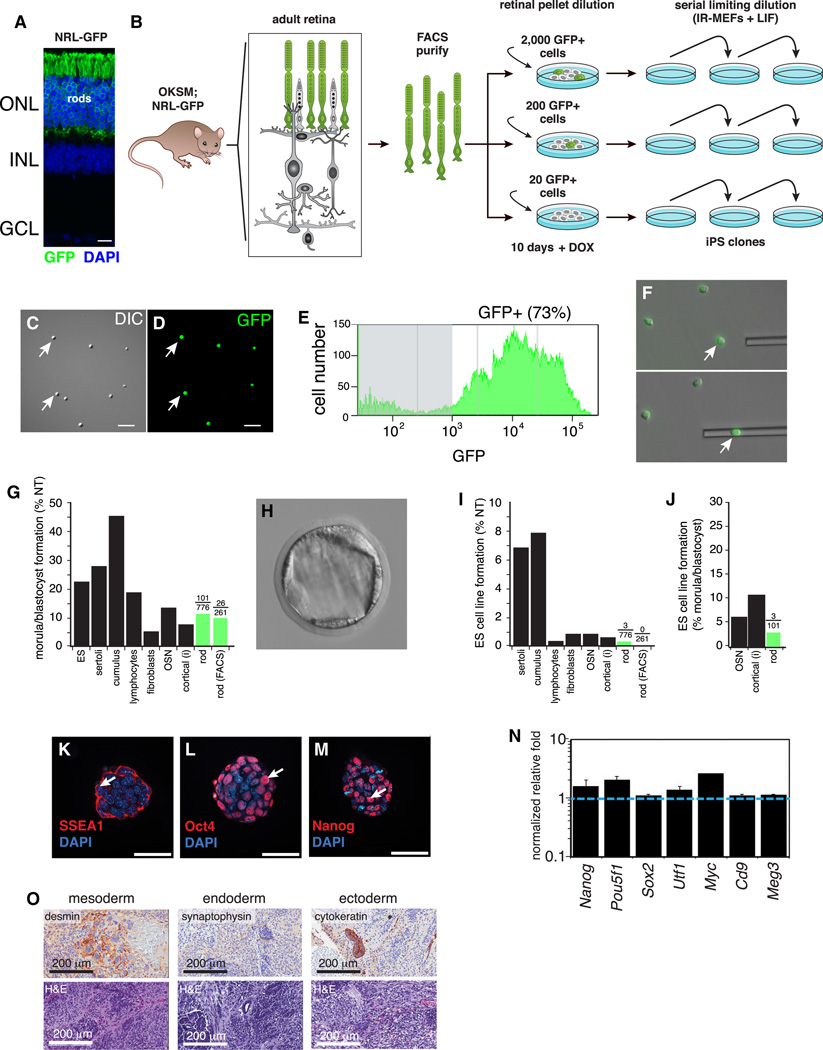

The r-iPSCs we generated from Nrl-GFP;Col1a1-OKSM;Rosa26-M2rtTA mice with GFP-labeled rod photoreceptors (Figure 2A). Mature GFP+ rod photoreceptors were purified by fluorescence activated cell sorting and mixed in limiting dilution with 1.5 × 106 C57Bl/6 P0–P5 retinal cells in retinal pellets cultured on polycarbonate filters (Figure 2B and Supplemental Information). This procedure was essential because purified rod photoreceptors do not survive when cultured as single cells (data not shown). Doxycycline (2 µg/mL) was added to the pellet cultures to induce expression of OKSM in the rod photoreceptors for 10 days. Then, individual pellets were dissociated into single-cell suspensions and plated in limiting dilution on irradiated MEFs in the presence of LIF to support the growth of r-iPSC colonies. To directly compare the efficiencies of reprogramming and retinal differentiation of immature and mature rod photoreceptors, the same experiment was performed with P2–P4 Nrl-GFP;Col1a1-OKSM;Rosa26-M2rtTA retinae (Table 1).

Figure 2. Generation and Characterization of Stem Cell Lines.

A) Micrograph of adult retina with expression of Nrl-GFP transgene (green fluorescence) in rod photoreceptors. B) Scheme for the production of r-iPSCs from rod photoreceptors. C,D) Micrographs of dissociated P12 Nrl-GFP retinae showing individual rod photoreceptors (arrows). E) Plot of the FACS distribution of GFP+ cells from P12 Nrl-GFP retinae. The gray shaded box represents the GFP– cells that were discarded. F) Serial micrographs showing the isolation of individual rod photoreceptor nuclei for somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). G) Histogram of the efficiency of morula/blastocyst formation for different cell populations. For the rod photoreceptors (green bars), SCNT was performed with flow sorted cells (FACS) and acute dissociation cultures. The numbers above the green bars represent the number of morula/blastocysts formed per nuclear transfer. H) Micrograph of a blastocyst derived from a rod photoreceptor by SCNT. I) Histogram of the percentage of NT that led to the production of embryonic stem cell (ESC) lines for the cell populations shown in (E). J) Histogram of the proportion of blastocysts/morula that produced ESC lines. Mitral neuron (MT) and shown for comparison. K-M) Immunofluorescence staining of individual colonies of FNR07 for SSEA1, Oct4, and Nanog (red fluorescence, arrows) with DAPI-stained nuclei (blue fluorescence). N) Histogram of qPCR for stem cell genes. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments, and all data are normalized to Gapdh and plotted relative to the EB5:Rx-GFP line (blue dashed line). O) Micrographs of immunostaining and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of teratomas derived from the FNR07 line. Representative regions with mesodermal-, endodermal-, and ectodermal-derived lineages are shown. Scale bars: C,D: 25 µm; K-M, 10 µm; Abbreviations: DIC, differential interference contrast microscopy; SSEA1, stem cell expressed antigen 1. See also Table S1.

We also performed somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) with rod photoreceptors isolated from postnatal day 6–14 Nrl-GFP mice (Fig. 2C–F) because SCNT can rapidly erase the epigenetic marks of differentiated cells (Hanna et al., 2010). As controls, we used nuclei isolated from embryonic stem cells (ES), Sertoli cells, cumulus cells, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and other types of immature and mature neurons. The development to late-stage preimplantation embryos (morula/blastocysts) from rod photoreceptors was comparable to that for other neuronal types (Figure 2G,H). However, ESCs were produced from those embryos at a much lower efficiency than other cell types (Figure 6I,J).

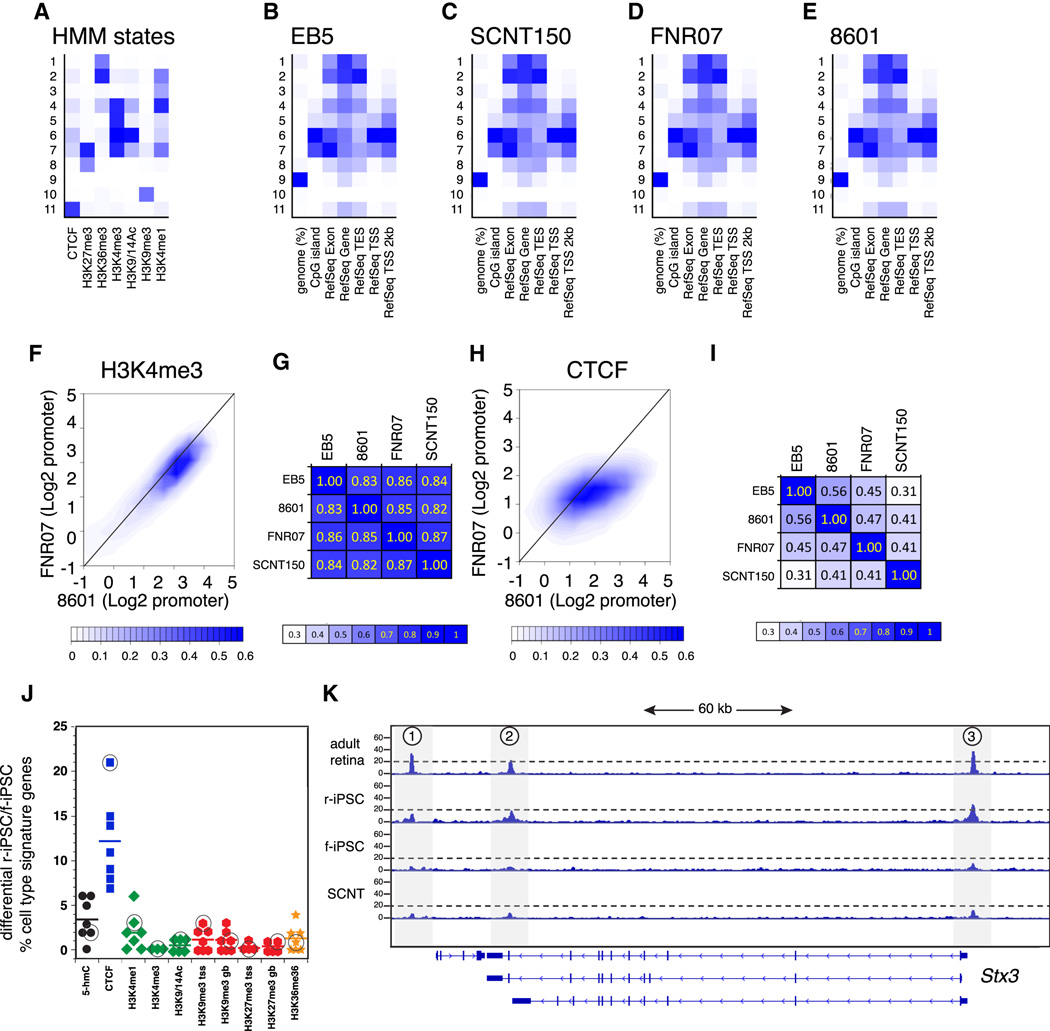

Figure 6. Epigenetic profiling of stem cell populations.

A) Hidden markov model (HMM) states used in this study. B-E) Profile of distribution of HMM states across genomic regions for the control line (EB5), the ESC line derived by somatic cell nuclear transfer of a rod nucleus (SCNT150), a representative f-iPSC (FNR07) and a representative r-iPSC (8601). F) Scatterplot of ChIP-Seq peaks (H3K4me3) for a representative r-iPSC line (8601) and a representative f-iPSC (FNR07) for the promoter regions of genes across the genome. G) Correlation matrix for H3K4me3 ChIP-Seq peaks across stem cell lines analyzed in this study. H) Scatterplot of ChIP-Seq for CTCF for a representative r-iPSC (8601) and f-iPSC (FNR07) for promoter regions. I) Correlation matrix for CTCF ChIP-Seq peaks across stem cell lines analyzed in this study. J) Plot of the differences between r-iPSC and f-iPSC for cell type specific signatures for each histone or epigenetic mark analyzed in this study. The bar represents the median for each mark. The circled marks represent the rod photoreceptor gene signature for each mark. K) Representative CTCF ChIP-Seq peaks for a rod photoreceptor gene (Stx3) with peaks flanking the transcriptional start (3) and termination (2). Peak 1 is at the 5’ end of an adjacent gene, Mrpl16. See also Figure S4 and Table S3.

Immunofluorescence studies confirmed the expression of Oct, Nanog, and SSEA-1 in individual iPSC colonies (Figures 2K–M). We also compared the expression of 7 genes that are markers of pluripotency to EB5:Rx-GFP ESCs by qPCR (Figures 2N). To directly test their pluripotency, we injected the individual iPSC lines into the flank of immunocompromised mice. Immunohistochemical staining of the resulting teratomas showed that they can form mesodermal-, endodermal-, and ectodermal-derived lineages (Figures 2O). In total, we selected 12 f-iPSC lines, 8 r-iPSC lines and 3 SCNT lines that had stable karyotypes and were fully reprogrammed for testing by STEM-RET (Table 1).

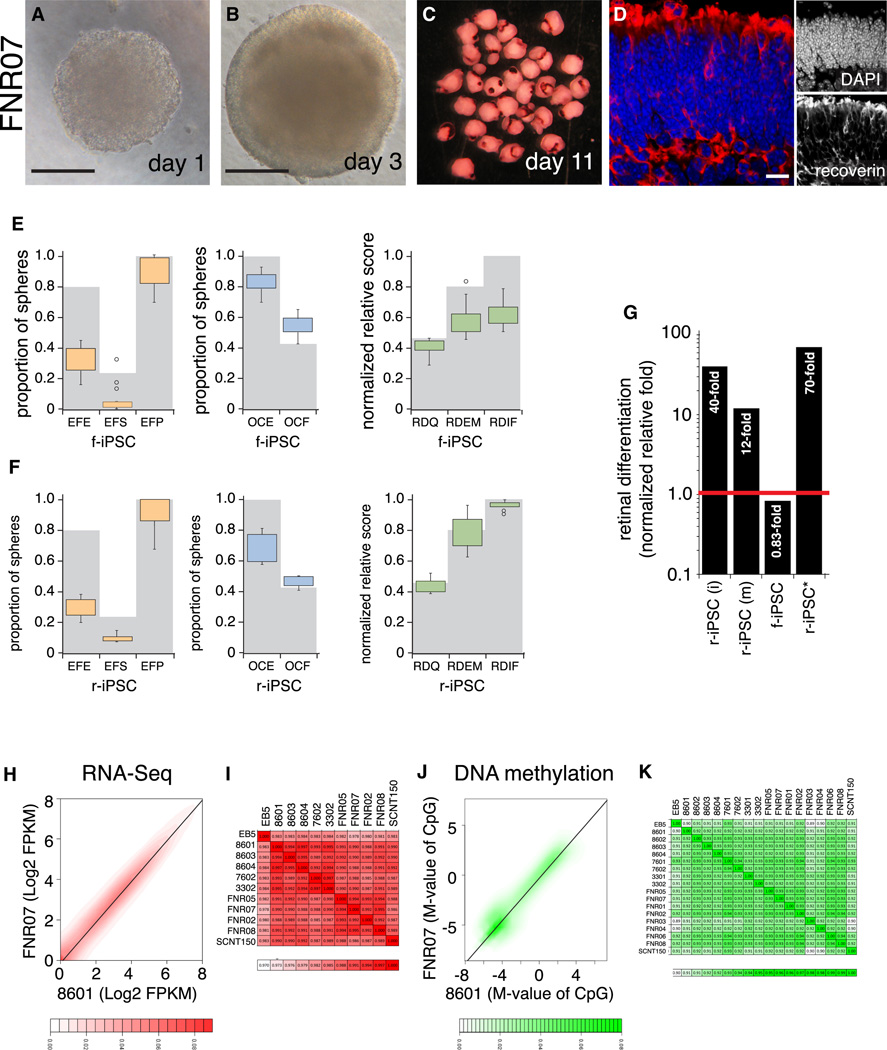

Retinogenesis from Murine iPSCs

We performed STEM-RET differentiation on the 23 stem cell lines described above. All experiments included the EB5:Rx-GFP ESC line as an internal control and over 10,000 individual cultures were scored (Tables 1 and S1). Except for iPS11, all iPSC lines underwent eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation (Fig. 3A–D, Tables 1 and S1). However, the EFE, EFS and OCE scores were lower than that for the EB5:Rx-GFP ESC line (Figure 3E,F and Supplemental Information). Early passage r-iPSCs (passages 7–10) were less efficient than late-passage r-iPSCs (passages 23–27) at producing eye field, optic cup, and retinae (Table S1). Late-passage r-iPSCs from immature rod photoreceptors were 40-fold more efficient than EB5:Rx-GFP ESCs in producing differentiated retinae, and late-passage r-iPSCs from mature rods were 12-fold more efficient than EB5:Rx-GFP ESCs in producing retinae (Figure 3G). The efficient retinal differentiation of immature and mature rod-derived iPSCs was maintained to at least passage 50 (data not shown). Lines 7601, 3301, 3302, and 8604, were up to 70-fold more efficient than EB5:Rx-GFP and 84-fold more efficient than f-iPSCs at producing differentiated retinae (Figure 3G and Supplemental Information).

Figure 3. Differentiation of Stem Cell Lines.

A) Micrograph of FNR07 cell aggregate 24 h after plating at the time of adding Matrigel. B) Micrograph of FDN02 cell aggregate day 3 in culture showing growth and formation of the neuroepithelium. C) Photograph of day 11 retinal pinches with extensive pigmentation. D) Section through the day 28 retina with recoverin immunofluorescence (red fluorescence) to label photoreceptors and nuclei stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence). E) Boxplot of scoring for eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation for 8 fibroblast-derived lines, with EB5:Rx-GFP values represented by gray bars. F) Boxplot of scoring for eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation for 8 rod-derived lines, with EB5:Rx-GFP values represented by gray bars. G) Histogram of retinal differentiation as measured by combined qPCR for 15 genes of retinal differentiation relative to EB5:Rx-GFP for immature r-iPSCs derived from immature rods (i), mature rods (m), and f-iPSCs. The combined data (r-iPSC*) are plotted for samples that scored 15/15 by qPCR for the retinal-derived iPSCs. H) Scatterplot of gene expression for a representative r-iPSC line (8601) and f-iPSC (FNR07). I) Correlation matrix for gene expression across stem cell lines based on RNA-Seq analysis. J) Scatterplot for DNA methylation for a representative r-iPSC (8601) and f-iPSC (FNR07). K) Correlation matrix for DNA methylation across stem cell lines. Scale bars: B,C: 200 µm; D: 25 µm. See also Fig. S2 and Table S2.

To determine whether improved retinal development came at the expense of other lineages, we performed cortical and osteogenic differentiation (Supplemental Information). Analysis of Foxg1, Pax6, Tbr1, Tbr2(Eomes), and Reelin expression by qPCR showed a subtle reduction in Pax6 expression and a more pronounced reduction in Tbr1, Tbr2, and Foxg1 gene expression in r-iPSCs relative to f-iPSCs (Figure S2). There was slightly higher expression of Spry2 in r-iPSCs in osteogenic differentiation experiments but none of the other osteoblast (Mef2c, Spry2, Sp7, and Runx2) or bone differentiation genes (Bglap and Ibsp) were significantly different between the r-iPSCs and the f-iPSCs (Figure S2).

Gene expression and DNA methylation analysis of the iPSC and ESC lines showed that they are very similar with correlation coefficients between 0.98 and 0.99 for gene expression and 0.90 to 0.94 for DNA methylation (Fig. 3H–K and Table S2). Integrated analysis of gene expression and DNA methylation identified only 22 genes with statistically significant differences across the f-iPSC and r-iPSC lines (Table S2 and data available upon request). 7 of the 22 genes were expressed at significantly higher levels in f-iPSCs and had corresponding changes in DNA methylation including genes implicated in skin development, homeostasis or disease (Prss8, Grhl2, Krt8 and Raet1e/Ulbp4). There were two major classes of genes expressed at higher levels in r-iPSCs. Genes implicated in retinal/CNS development, homeostasis and disease were identified (Snord116, Prkca, Rian). In addition, there were genes that are implicated in pathways involved in ocular immune privilege (Ifi27l1, Irgm1, Eif2ak2, Zbp1, Stat1) (Table S2).

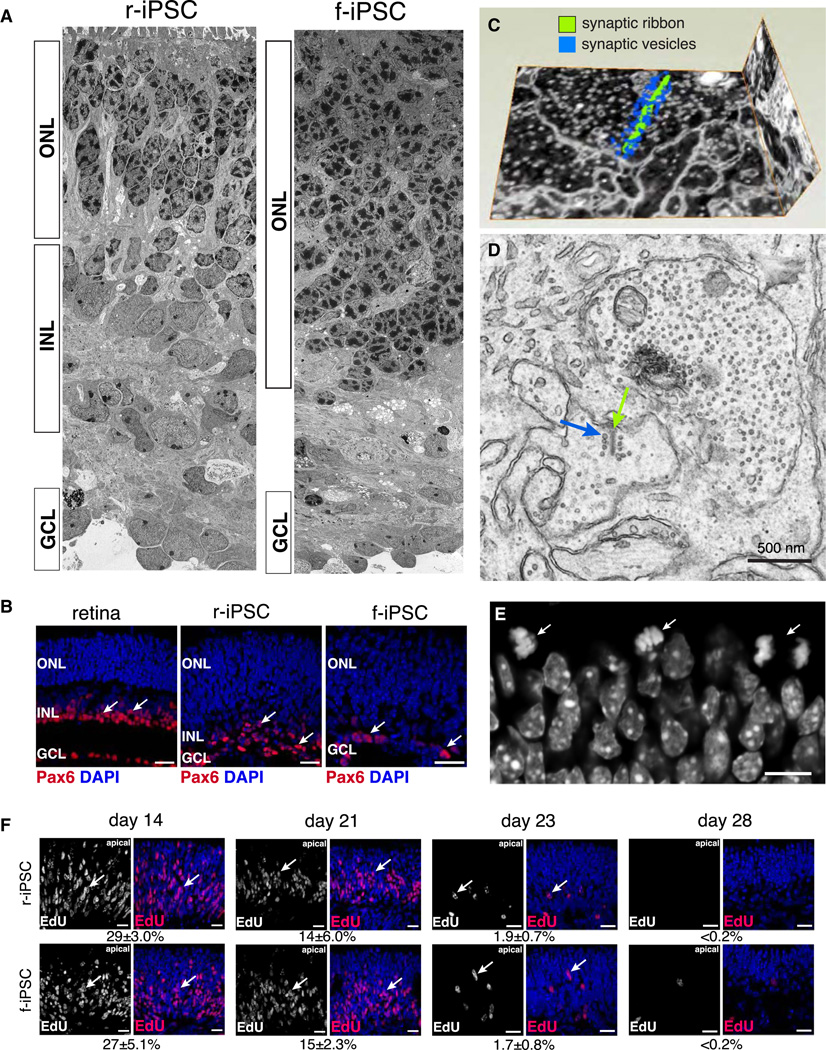

f-iPSCs Produce Fewer Inner Nuclear Layer Cells

The most pronounced differences among r-iPSCs, f-iPSCs, and EB5:Rx-GFP were associated with retinal differentiation. There were significant differences in retinal differentiation measured by qPCR (RDQ; P = 0.04), TEM (RDEM; P = 0.003), and immunofluorescence (RDIF; P < 0.0001) for r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs (Figure 3E,F). Notably, amacrine cells and other INL cells were reduced in f-iPSCs as compared to r-iPSCs or EB5:Rx-GFP stem cells (Table S1). The difference in retinal differentiation was most striking in electron microscopy studies (Figure 4A) and was independently validated by immunofluorescence and qPCR (Figure 4B and Table S1). We performed 3-dimensional electron microscopy on retinae derived from r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs and there were well-formed synaptic ribbons in the photoreceptor terminals (Figure 4C,D, Movie 1 and data not shown).

Figure 4. f-iPSCs have Defects in Retinal Differentiation.

A) Electron micrograph montage of day 28 r-iPSC– and f-iPSC–derived retinal tissue. B) Immunofluorescence of adult retinae and day 28 r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs for Pax6 (red fluorescence, arrows) and nuclei (blue fluorescence). C) 3-D reconstruction of synaptic ribbon in retina from r-iPSCs using a Helios dual beam electron microscope. D) Representative electron micrograph of retina derived from r-iPSCs showing synaptic ribbon (green arrow) and associated synaptic vesicles (blue arrow). E) Micrograph of nuclei stained with DAPI on the apical surface of a day 21 r-iPSC–derived retina differentiated using STEM-RET. Arrows indicate mitotic figures along the apical edge of the retinae. F) Representative micrographs showing EdU staining (red fluorescence, arrows) with DAPI nuclear stain (blue fluorescence) on days 14, 21, 23, and 28 in culture for r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs. The relative proportion of EdU-immunopositive cells for each sample is shown under each pair of micrographs. Scale bars: B,F: 25 µm; E: 10 µm. Abbreviations: ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. See also Movie S1.

To determine if the differences in retinal differentiation between r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs was the result of changes in retinal progenitor cell proliferation, we performed an EdU pulse labeling experiment on days 14, 21, 23, and 28 for side-by-side cultures of f-iPSC (FNR05 and FNR07) and r-iPSC (8601, 8604, and 7602) lines. The retinal progenitor cells underwent interkinetic nuclear migration with the S-phase at the basal surface of the retina and mitosis at the apical surface in these cultures (Figure 4F). The proportion of S-phase cells on days 14, 21, 23, and 28 was indistinguishable for f-iPSCs and r-iPSCs (Figure 4F). These data were similar to those obtained for EB5:Rx-GFP at the same time points (data not shown).

For the ESC lines derived by SCNT of rod photoreceptor nuclei (Table 1), the eye field score was 0.43±0.02, the optic cup score was 0.44±.07 and the retinal differentiation score was 0.35±0.17. In the cryosections and electron micrographs, retinal cell types were present but lacked clear laminar organization. It is not known if EB5:Rx-GFP is typical of ESC lines or if the inefficient retinal differentiation of SCN194, SCN212 and SCN150 is more representative of murine ESC lines. To begin to distinguish between these possibilities, we obtained the original EB5 ESC line that was used to make the EB5:Rx-GFP knock-in line (Fig. S3). We performed STEM-RET differentiation with EB5 and EB5:Rx-GFP and found that the EB5 parent line was very similar to SCN194, SCN212 and SCN150 and was inefficient at retinal differentiation (Tables 1 and S1 and Figure S3). We performed whole genome sequencing of the EB5 and EB5:Rx-GFP lines and identified single nucleotide variations (SNVs) that have been acquired in the EB5:Rx-GFP line (Figure S3). However, none of those SNVs were in genes known to be important for neurogenesis (data not shown). DNA methylation analysis on the EB5 and EB5:Rx-GFP lines identified phosphoprotein and alternative splicing as the most significantly different pathways (Figure S3 and data not shown).

Genetic and Pharmacologic Manipulation of Retinal Development Using STEM-RET

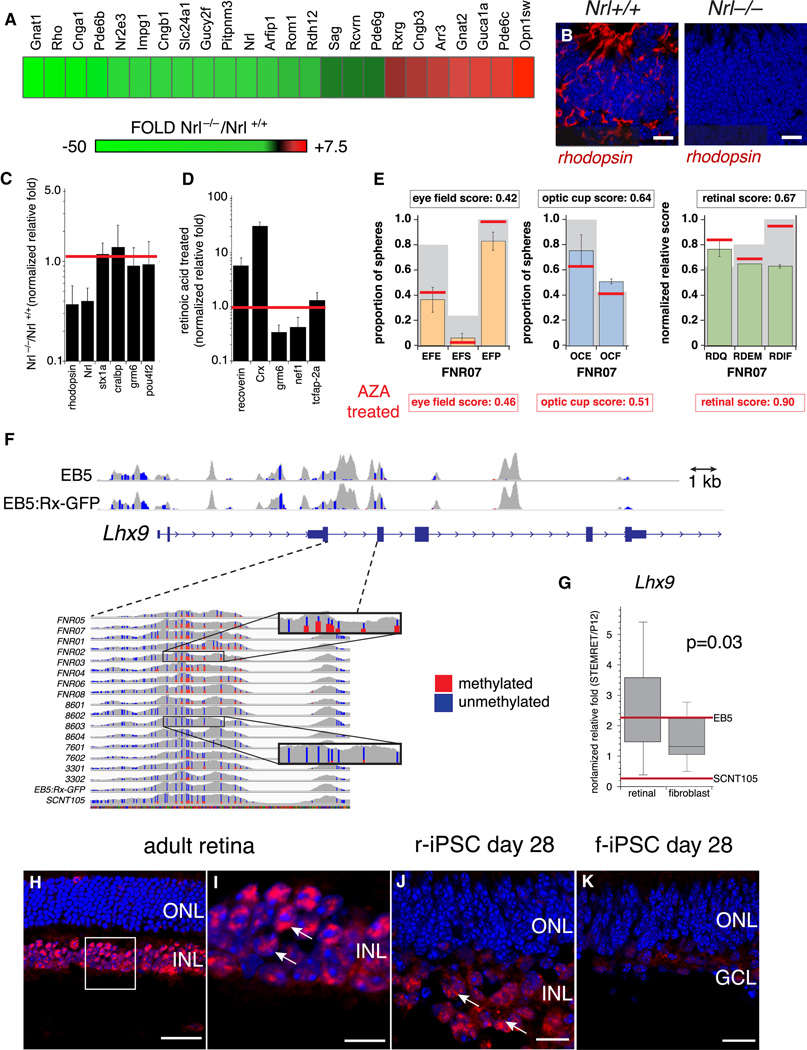

To determine whether Nrl−/− f-iPSCs recapitulated the defect in rod differentiation found in Nrl−/− mice (Mears et al., 2001), we performed a gene expression array analysis of Nrl−/− and Nrl+/+ f-iPSC–derived retinae (day 28). As expected, rod photoreceptor genes were downregulated and S-cone genes were upregulated in Nrl−/− f-iPSC-derived retinae (Figure 5A). The downregulation of rhodopsin was verified by immunofluorescence and qPCR (Figure 5B,C).

Figure 5. Retinal differentiation of r-iPSCs.

A) Heat map of the most significant up-(red) and downregulated (green) genes in retinae derived from Nrl−/− and Nrl+/+ f-iPSCs by using STEM-RET. B) Representative immunofluorescence for rhodopsin (red) in cryosection of retinae derived from Nrl−/− and Nrl+/+ f-iPSCs by using STEM-RET. Blue fluorescence shows DAPI staining of nuclei. C) Histogram of qPCR using TaqMan® probes for retinal genes from STEM-RET–differentiated Nrl+/+ and Nrl−/− iPSCs. Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of duplicate PCR reactions, and each experiment was performed in triplicate. Data are plotted relative to Gapdh expression. D) Histogram of qPCR using TaqMan® probes for retinal genes from STEM-RET–differentiated r-iPSCs in the presence of retinoic acid, using the EB5:Rx-GFP ESC line as a reference (red line). Each bar represents the mean and standard deviation of duplicate qPCR reactions, and each experiment was performed in triplicate. Data are normalized to Gapdh expression and plotted relative to normal P12 retinal expression. E) Histograms of scoring of eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation for the FDN02 iPSC line, with the EB5:Rx-GFP values represented by gray bars. The red lines indicate the scores for FNR07 treated with 5-azacytidine. F) Diagram of the mouse Lhx9 gene total coverage (gray) and unmethylated CpGs (blue) and methylated CpGs (red) for the EB5 and EB5:Rx-GFP ESC lines. DNA methylation pattern of the indicated intron/exon region of Lhx9 showing unmethylated CpGs (blue) and hypermethylated CpGs (red) across the indicated stem cell lines. G) Boxplot of qPCR using TaqMan® probes for Lhx9 in the r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs relative to EB5 and SCNT105 (red lines). The data for replicate qPCR reactions is plotted for all 8 f-iPSCs and all 8 r-iPSCs. H-K) Immunofluorescence for Lhx9 in normal adult mouse retina (red fluorescence in D,E) and r-iPSC and f-iPSC derived retinae. Arrows indicate nuclei in the inner nuclear layer (INL) that are immunopositive for Lhx9. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars: B,: 25 µm; I-K: 10 µm. Abbreviations: ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. See also Figure S3.

Exogenous factors such as retinoic acid (RA) can promote photoreceptor differentiation(Hyatt et al., 1996), and RA is included for 4 days in STEM-RET. To determine whether r-iPSCs were responsive to additional RA treatment, 0.5 µM RA was added to the differentiation medium for the entire differentiation period (days 10–28) in STEM-RET and gene expression was analyzed by qPCR. There was an increase in the expression of photoreceptor genes such as recoverin and Crx at the expense of other retinal cell-type specific genes (Figure 5D).

In previous studies on epigenetic memory of iPSCs derived from neural progenitor cells, treatment with 5-azacytidine and trichostatin A (AZA/TSA) improved their ability to form blood lineages (Kim et al., 2010). We treated a f-iPSC line (FNR07), a r-iPSC line (8601) and EB5:Rx-GFP cells with AZA/TSA as done previously (Kim et al., 2010) (Table S1). The AZA/TSA treated EB5:Rx-GFP cells were very similar to the untreated EB5:Rx-GFP cells (Table S1). For the r-iPSCs, there was an improvement in the optic cup score but the eye field and retinal scores were similar for untreated and AZA/TSA treated 8601 r-iPSCs (Table S1). The f-iPSCs had an improved retinal score from 0.67 to 0.90 following AZA/TSA treatment and there was a partial rescue of the INL defect (Figure 5E and Table S1).

Rod Photoreceptor Epigenetic Memory

Next, we analyzed the correlation between DNA methylation in the different stem cell populations with gene expression in differentiated retinae derived from these lines. While no annotated genes achieved statistical significance there were several trends that were consistent with the loss of INL cells in the f-iPSC derived retinae. For example, we found that Lhx9 was hypermethylated in all 8 of the f-iPSC lines relative to the r-iPSC lines or the EB5 line (Figure 5F). The hypomethylation of Lhx9 in r-iPSCs correlated with higher expression in retinae derived from those lines (Figure 5G). Lhx9 is expressed in the INL of the developing retina and has been implicated in eye morphogenesis (Alunni et al., 2007; Balasubramanian et al., 2014; Pottin et al., 2011). The differential methylation correlated with changes in protein expression in retinae derived from r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs (Figure 5H). In addition to CpG DNA methylation, we also identified several genes involved in retinal development, stress response and degeneration (Lrrk2, Rbbp7, Ebf1, Cxcl2, Dlx5, Nfasc, Btrc) to have elevated promoter 5-hmC levels in r-iPSCs and several genes involved in epithelial cell transport had elevated 5-hmC levels in f-iPSCs (Slc19a1, Clca5, Yipf4, Shisa2, Stip1) (Table S3).

To further refine the differential epigenetic landscape we performed ChIP-Seq analysis on EB5:Rx-GFP, SCN150, FNR07 and 8601 using antibodies to CTCF, H3K27me3, H3K36me3, H3K4me3, H3K9/14Ac, H3K9me3 and H3K4me1. We performed Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM) and defined 11 chromatin states in these stem cell populations (Fig. 6A). States 1 and 2 have a strong signature for H3K36me3 often found in gene bodies. State 3 has only H3K4me1 that is associated with latent enhancers while states 4–6 have profiles consistent with actively transcribed genes. States 7 and 8 have strong signals for H3K27me3 indicative of polycomb repressed or bivalent genes. State 9 has none of the marks tested in this study, state 10 is H3K9me3 repressed chromatin and state 11 is associated with CTCF and H3K4me1 marks. As expected, the distribution of the 11 chromatin states was very similar across the ESC and iPSC lines at a genome-wide level (Fig. 6B–E). The histone marks that are associated with active promoters (H3K4me3 and H3K9/14Ac) were similar across the lines with a 0.98 correlation coefficient for peak occupancy for H3K4me3 between r-iPSC and f-iPSC and 0.95 for peak occupancy for H3K9/14Ac (Table S3 and Fig. 6F,G). In contrast, the CTCF insulator mark had a correlation coefficient of 0.66 for peak occupancy between the r-iPSC and the f-iPSC lines (Table S3 and Fig. 6H,I). To determine if any of the genes with differential CTCF binding in r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs were involved in retinal development, we analyzed a series of cell type specific genes previously identified and validated by single cell gene expression analysis (Cherry et al., 2009; Trimarchi et al., 2008; Trimarchi et al., 2007). This included 59 amacrine cell genes, 111 cone genes, 179 rod genes, 75 ganglion cell genes, 345 progenitor cell genes, 54 genes involved in proliferation and as a control, 23 housekeeping genes. All of the cell type specific epigenetic data are available upon request. Among all of these 846 genes, the mark that was most differential across r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs was CTCF and the cell type that had the highest proportion of differential CTCF peaks was rod photoreceptors (Fig. 6J). Rod specific genes with enriched CTCF peaks included Aipl1, Rhod, Prom1, Gnat1, Stx3 and Unc13b (Fig. 6J,K and Fig. S5).

To determine if the differences in CTCF binding in the r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs had any functional significance relevant to chromatin domains (Dowen et al., 2014; Hou et al., 2010; Phillips and Corces, 2009; Wang et al., 2012), we performed a pairwise comparison of the boundaries between each of the 11 chromatin states defined by HMM in each of the stem cell lines. The genomewide occurrences of flanking HMM state pairs at the transitions between different HMM states were counted in each stem cell line. After removal of pairs to/from State 9 (the empty state), a flanking state enrichment score for each flanking pair was calculated as the ratio between observed occurrence and expected occurrence. A value of 1.0 indicates that the state junction occurrence is exactly as predicted by chance. A value greater than 1 indicates enrichment of that state junction and a value less than 1 indicates a depletion of the state junction (Table S3). Our data show that for State 11 (strong CTCF binding only), the transition to/from State 8 (polycomb repressed with strong H3K27me3 only) is the most enriched transition. For State 8, the most enriched transition is to/from State 7 (CTCF with broad H3K27me3 peaks overlapping with sharp H3K4me3 peaks at poised promoters).

DISCUSSION

We developed STEM-RET, a quantitative protocol to measure eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation from stem cell populations. We tested the efficiency of f-iPSCs from retroviral transduction and reprogrammable mice and showed that f-iPSCs developed by either method produce retinae in culture. However, compared with retinae produced from murine ESCs or rod-derived iPSCs, these retinae had defects in the generation of amacrine cells and other INL cells. The r-iPSCs were more efficient than other stem cell populations at producing differentiated retinae, and this efficiency was maintained for at least 50 passages in culture. Our results support that iPSCs can be used to model genetic defects associated with retinopathies and can be pharmacologically manipulated to modulate retinal differentiation. Lhx9 was hypermethylated in f-iPSCs, which correlates with a reduction in Lhx9 expression in retinae derived from f-iPSCs. Our findings suggest that epigenetic memory mediated in part by CTCF can affect retinal development and that retinal neuron-derived iPSCs can be a useful renewable source of cells to produce photoreceptor precursors.

Quantitative Assessment of Retinal Differentiation by STEM-RET

The development of a method to produce retinae in 3D cultures from human and mouse ESCs was an important advance in retinal biology, because these organ cultures recapitulate several molecular, cellular, and morphologic features of normal retinal development (Eiraku et al., 2011). Our quantitative and standardized method to compare retinal differentiation across stem cell lines (STEM-RET) focuses on the key steps in retinal development, including eye field specification, optic cup formation, and retinal differentiation, and incorporates complementary independent assays to analyze retinal differentiation. This quantitative procedure was essential for our studies on r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs, because it allowed us to pinpoint the defect in retinogenesis in f-iPSCs. It also allowed us to directly compare the parental EB5 ESC line to the EB5:Rx-GFP line. It is not known if the genetic or epigenetic differences account for the difference between these lines in their efficiency of retinal differentiation. It is possible that in the process of selecting an individual EB5:Rx-GFP clone when the line was made, the investigators selected the line that was particularly efficient at neuronal/retinal differentiation. This may explain why the EB5 parent line and the 3 SCNT ESC lines that we developed in this study are not efficient at retinal differentiation. As the field expands, STEM-RET can become an important tool to compare and contrast various human and murine stem cell populations tested in different laboratories. It is also very useful for quantitating differences in retinal differentiation using pharmacological and genetic manipulation.

Retinal Differentiation from Diverse Stem Cell Populations

There was no significant difference in retinal differentiation from f-iPSCs derived from the reprogrammable mouse or by viral transduction, except that f-iPSCs derived by viral transduction had low expression of Meg3, a marker of reprogramming (Buganim et al., 2013; Carey et al., 2011). In our study, Meg3 expression was not predictive of the ability of a line to produce retina by using STEM-RET, but additional lines need to be characterized to confirm whether this generally holds true for iPSCs. We also tested several lines with abnormal karyotypes to determine whether the karyotypic changes that can occur during the cloning of iPSCs can affect retinal differentiation. In general, there was no correlation between karyotype and retinal differentiation. Some lines with significant aneuploidy produced retinae as efficiently as those with normal karyotypes (data not shown).

Studies have found that human f-iPSCs produce retinae with properly laminated INL cell populations (Zhong et al., 2014) using a modification of the protocol from the Gamm lab (Meyer et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2012), but we did not observe this in our studies on mouse f-iPSCs. Although the source of fibroblasts were different (embryonic versus adult), important species differences may exist and caution needs to be exercised in directly extrapolating data from mouse models to humans.

Reprogramming Retinal Neurons

In attempts to reprogram cortical neurons, Kim et al. found that the expression of Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc was not sufficient to produce iPSCs (Kim et al., 2011), and p53 needed to be inactivated for efficient reprogramming. Our data on retinal neurons are consistent with the Kim et al. study. Our initial attempts to produce iPSCs from retinal neurons by using the reprogrammable mouse failed because retinal neurons do not survive in culture long enough to support reprogramming when plated as dissociated cells. An advantage of the retina is that it can be cultured as an explant on polycarbonate filters, and chimeric retinal pellets have been extensively used to study retinal development and cell–cell signaling (Belliveau and Cepko, 1999; Belliveau et al., 2000; Morrow et al., 1998). Therefore, we reasoned that retinal neuron reprogramming could be achieved by using mosaic retinal pellet cultures produced by mixing reprogrammable retinal neurons with normal retinal cells in retinal explant mosaic pellets. By using this system, we efficiently reprogrammed rod photoreceptors at 2 developmental stages without the need to inactivate p53. It is not known whether this is a unique feature of retinal neurons or whether more efficient reprogramming could be achieved by using similar mosaic culture approaches for cortex, cerebellum, or other regions of the CNS.

Epigenetic Memory of r-iPSCs

To establish an association between the defect in amacrine/INL cell production from f-iPSCs and changes in the epigenetic landscape, we analyzed the DNA methylation of 60 genes that have been found to be enriched in amacrine cells by single-cell array analysis (Cherry et al., 2009). Of them, Lhx9 showed an increase in DNA methylation and reduced expression in retinae derived from the 8 independent f-iPSC lines. Lhx9 is expressed in the developing ganglion cell layer and in postmitotic cells of the INL during development. In the adult mouse retina, Lhx9 is expressed in a subset of mature amacrine cells (Balasubramanian et al., 2014). Lhx9 expression is altered in blind cavefish (Astyanax mexicanus) compared with surface fish (Alunni et al., 2007), and rescue of eye morphogenesis by altering fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling restores Lhx9 expression (Pottin et al., 2011). Interestingly, Lhx9-deficient mice have defects in male and female gonad formation but are otherwise normal despite broad expression in the developing CNS and other tissues (Birk et al., 2000). Although our results suggest that Lhx9 hypermethylation is not sufficient to cause defects in retinal development in f-iPSC–derived retinae, they provide a valuable proof-of-principle for the importance of quantitative and comprehensive analysis of retinal differentiation by using different stem cell lines and of defining the optimal epigenetic landscape for retinal differentiation in culture.

In addition to DNA methylation, our analysis of 5hmC, H3K27me3, H3K4me1, CTCF, H3K9/14Ac, H3K9me3 and H3K36me3 provide important insights into the epigenetic landscape of the r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs relative to their cellular origins. Specifically, the gene expression, global DNA methylation, promoter and enhancer marks (H3K4me3, H3K4me1 and H3K9/14Ac) were remarkably similar across the r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs. This provides confirmation at the epigenetic level that these iPSC lines are fully reprogrammed and multipotent. There were some differences in the pattern of repressive marks (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) between f-iPSCs and r-iPSCs but they were not enriched in retinal genes. Also, pathways involved in neuron differentiation, synapse formation and axon guidance were differentially methylated but additional ESC lines will need to be analyzed to strengthen the correlation between methylation differences at particular loci and the STEM-RET score.

In contrast, differential binding of CTCF between r-iPSCs and f-iPSCs was enriched in retinal genes and there was significantly more in rod-specific genes than the other cell types. While it is possible that the efficiency of CTCF chromatin immunoprecipitation was reduced in the f-iPSC and SCNT lines we do not believe this technical artifact accounts for these differences. In particular, genes with super-enhancer CTCF binding sites had similar peaks across lines and there were some regions of the genome that had enrichment of CTCF in f-iPSCs relative to r-iPSCs. Moreover, if the enrichment in r-iPSC lines was non-specific, we would predict that all cell type signatures would have similar enrichment of CTCF binding. Our data show that rod photoreceptor genes were significantly more likely to retain CTCF binding sites in the r-iPSCs relative to f-iPSCs versus other retinal cell type signatures or for housekeeping genes.

CTCF is an insulator protein that separates active and repressed domains of the genome in a cell type specific manner. For example, in a comparison of CTCF binding sites across ESCs, liver and brain, approximately one third of sites were shared across all 3 cell types, one third were unique to liver and one third unique to brain. Moreover, only 5% were unique to ESCs suggesting that their CTCF distribution is a ground state that is modified as cells commit to particular lineages and differentiate (Prickett et al., 2013). If this is true, then cellular reprogramming may erase some of the CTCF sites to restore the active and repressed domains in the genome to the multipotent stem cell state. Our data suggest that some of those CTCF peaks associated with rod photoreceptor differentiation are retained in r-iPSCs and this may contribute to the efficient differentiation of r-iPSCs into retina. In particular, the HMM state transition analysis suggested that boundaries defined by CTCF relative to polycomb repressed (H3K27me3) or bivalent regions (H3K27me3+H3K4me3) appear to be particularly relevant to the functional differences between f-iPSCs and r-iPSCs in retinal differentiation. It is also possible that the perturbations in CTCF domains contributes to the defects in retinal cell fate specification of f-iPSCs. Alternatively, changes in histone modifications may impact the persistence of CTCF binding sites during reprogramming. In either case, these data suggest that in addition to DNA methylation, higher order chromatin looping may contribute to epigenetic memory in iPSCs derived from different cell sources.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

All animal procedures and protocols were approved by the St. Jude Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee. Col1a1-OKSM; Rosa26-M2rtTA mice were obtained from Konrad Hochedlinger and crossed with either Nrlwt; Nrl-GFP+ or Nrl−/−; Nrl-GFP+ mice provided by Anand Swaroop.

Cell Culture

Cell culture and differentiation was carried out as described previously(Eiraku and Sasai, 2012b; Eiraku et al., 2011). A detailed protocol is provided in Supplemental Information.

Differentiation of ESCs and iPSCs using the STEM-RET protocol

ESCs, r-iPSC, and f-IPSC lines underwent retinal morphogenesis using the protocol as previously published by Sasai et al ((Eiraku et al., 2011) as described except for a few notable exceptions. These changes did not appear to impact the differentiation of the cell lines into retinal tissue. We cultured our stem cell lines on gelatin-coated tissue culture plates with an irradiated MEF feeder layer. To separate the stem cells from this feeder layer, cells were dissociated with ESC-digest buffer (0.25% trypsin, 1mg/mL collagenase, 20% KSR, 1 µM CaCl2 in PBS) and pre-plated for 30 minutes at 37°C on gelatin-coated tissue culture plates. The amount of MEFs remaining in the cell suspension after this pre-plating was negligible and did not appear to impact the ability of a cell line to differentiate into retinal tissue. We also extensively tested several matrigel lots ranging from 6.0 mg/mL to 11.0 mg/ml of laminin and enactin protein and used a lot containing 9.2 mg/mL of protein. This lot was used for all STEM-RET experiments and was chosen based on availability at the time of ordering. Several preliminary studies with the Eb5:Rx-GFP line indicated this concentration of laminin and enactin was sufficient to induce retinal morphogenesis.

EdU Labeling Experiments

Retinal spheres were incubated with 10 µM 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) for two hours at 37°C. Spheres were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C before cryosectioning and immunofluorescence labeling as described above. EdU labeling was visualized with an alexa flour 555 or 647 Click-it plus EdU kit (Life Technologies).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Konrad Hochedlinger for the reprogrammable mice, Anand Swaroop for Nrl-GFP and Nrl−/− mice, Samantha Cicero for assistance with viral reprogramming, Vani Shanker for editing the manuscript and David Finkelstein for assistance with bioinformatics analysis. FEI assisted with image acquisition for the 3D TEM (5350 NE Dawson Creek Drive Hillsboro Oregon 97124 USA). This work was supported, in part, by Cancer Center Support (CA21765) from the NCI, grants to M.A.D from the NIH (EY014867 and EY018599 and CA168875), and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). M.A.D. was also supported by a grant from Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer. R.N.E. was supported by grant # RO1CA20525 from the NCI. P.A.C. was supported by an NCI training grant (T32 CA009657).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alunni A, Menuet A, Candal E, Penigault JB, Jeffery WR, Retaux S. Developmental mechanisms for retinal degeneration in the blind cavefish Astyanax mexicanus. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505:221–233. doi: 10.1002/cne.21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assawachananont J, Mandai M, Okamoto S, Yamada C, Eiraku M, Yonemura S, Sasai Y, Takahashi M. Transplantation of embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived 3D retinal sheets into retinal degenerative mice. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian R, Bui A, Ding Q, Gan L. Expression of LIM-homeodomain transcription factors in the developing and mature mouse retina. Gene Expr Patterns. 2014;14:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belliveau MJ, Cepko CL. Extrinsic and intrinsic factors control the genesis of amacrine and cone cells in the rat retina. Development. 1999;126:555–566. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belliveau MJ, Young TL, Cepko CL. Late retinal progenitor cells show intrinsic limitations in the production of cell types and the kinetics of opsin synthesis. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2247–2254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02247.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birk OS, Casiano DE, Wassif CA, Cogliati T, Zhao L, Zhao Y, Grinberg A, Huang S, Kreidberg JA, Parker KL, et al. The LIM homeobox gene Lhx9 is essential for mouse gonad formation. Nature. 2000;403:909–913. doi: 10.1038/35002622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz DE, Hikita ST, Rowland TJ, Friedrich AM, Hinman CR, Johnson LV, Clegg DO. Derivation of functional retinal pigmented epithelium from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:2427–2434. doi: 10.1002/stem.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buganim Y, Faddah DA, Jaenisch R. Mechanisms and models of somatic cell reprogramming. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:427–439. doi: 10.1038/nrg3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey BW, Markoulaki S, Hanna JH, Faddah DA, Buganim Y, Kim J, Ganz K, Steine EJ, Cassady JP, Creyghton MP, et al. Reprogramming factor stoichiometry influences the epigenetic state and biological properties of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry TJ, Trimarchi JM, Stadler MB, Cepko CL. Development and diversification of retinal amacrine interneurons at single cell resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9495–9500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903264106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer AO, MacLaren RE. Translating induced pluripotent stem cells from bench to bedside: application to retinal diseases. Curr Gene Ther. 2013;13:139–151. doi: 10.2174/1566523211313020008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowen JM, Fan ZP, Hnisz D, Ren G, Abraham BJ, Zhang LN, Weintraub AS, Schuijers J, Lee TI, Zhao K, Young RA. Control of cell identity genes occurs in insulated neighborhoods in Mammalian chromosomes. Cell. 2014;159:374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraku M, Sasai Y. Mouse embryonic stem cell culture for generation of three-dimensional retinal and cortical tissues. Nature Protocols. 2012a;7:69–79. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraku M, Sasai Y. Self-formation of layered neural structures in three-dimensional culture of ES cells. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2012b doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiraku M, Takata N, Ishibashi H, Kawada M, Sakakura E, Okuda S, Sekiguchi K, Adachi T, Sasai Y. Self-organizing optic-cup morphogenesis in three-dimensional culture. Nature. 2011;472:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nature09941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Cordero A, West EL, Pearson RA, Duran Y, Carvalho LS, Chu CJ, Naeem A, Blackford SJ, Georgiadis A, Lakowski J, et al. Photoreceptor precursors derived from three-dimensional embryonic stem cell cultures integrate and mature within adult degenerate retina. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:741–747. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna JH, Saha K, Jaenisch R. Pluripotency and cellular reprogramming: facts, hypotheses, unresolved issues. Cell. 2010;143:508–525. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargus G, Ehrlich M, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Hemmer K, Hallmann AL, Reinhardt P, Kim KP, Adachi K, Santourlidis S, Ghanjati F, et al. Origin-dependent neural cell identities in differentiated human iPSCs in vitro and after transplantation into the mouse brain. Cell Rep. 2014;8:1697–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C, Dale R, Dean A. Cell type specificity of chromatin organization mediated by CTCF and cohesin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3651–3656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Friedrich AM, Johnson LV, Clegg DO. Memory in induced pluripotent stem cells: reprogrammed human retinal-pigmented epithelial cells show tendency for spontaneous redifferentiation. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1981–1991. doi: 10.1002/stem.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyatt GA, Schmitt EA, Fadool JM, Dowling JE. Retinoic acid alters photoreceptor development in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13298–13303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Lengner CJ, Kirak O, Hanna J, Cassady JP, Lodato MA, Wu S, Faddah DA, Steine EJ, Gao Q, et al. Reprogramming of postnatal neurons into induced pluripotent stem cells by defined factors. Stem Cells. 2011;29:992–1000. doi: 10.1002/stem.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, Ng K, Zhao R, Cahan P, Kim J, Aryee MJ, Ji H, Ehrlich LI, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren RE, Pearson RA, MacNeil A, Douglas RH, Salt TE, Akimoto M, Swaroop A, Sowden JC, Ali RR. Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors. Nature. 2006;444:203–207. doi: 10.1038/nature05161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mears AJ, Kondo M, Swain PK, Takada Y, Bush RA, Saunders TL, Sieving PA, Swaroop A. Nrl is required for rod photoreceptor development. Nat Genet. 2001;29:447–452. doi: 10.1038/ng774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JS, Howden SE, Wallace KA, Verhoeven AD, Wright LS, Capowski EE, Pinilla I, Martin JM, Tian S, Stewart R, et al. Optic vesicle-like structures derived from human pluripotent stem cells facilitate a customized approach to retinal disease treatment. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1206–1218. doi: 10.1002/stem.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JS, Shearer RL, Capowski EE, Wright LS, Wallace KA, McMillan EL, Zhang SC, Gamm DM. Modeling early retinal development with human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16698–16703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905245106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow EM, Belliveau MJ, Cepko CL. Two phases of rod photoreceptor differentiation during rat retinal development. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3738–3748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03738.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano T, Ando S, Takata N, Kawada M, Muguruma K, Sekiguchi K, Saito K, Yonemura S, Eiraku M, Sasai Y. Self-Formation of Optic Cups and Storable Stratified Neural Retina from Human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:771–785. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendra V, Rocha PP, An D, Raviram R, Skok JA, Mazzoni EO, Reinberg D. Transcription. CTCF establishes discrete functional chromatin domains at the Hox clusters during differentiation. Science. 2015;347:1017–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.1262088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RA, Barber AC, Rizzi M, Hippert C, Xue T, West EL, Duran Y, Smith AJ, Chuang JZ, Azam SA, et al. Restoration of vision after transplantation of photoreceptors. Nature. 2012;485:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, Corces VG. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell. 2009;137:1194–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MJ, Wallace KA, Dickerson SJ, Miller MJ, Verhoeven AD, Martin JM, Wright LS, Shen W, Capowski EE, Percin EF, et al. Blood-derived human iPS cells generate optic vesicle-like structures with the capacity to form retinal laminae and develop synapses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2007–2019. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottin K, Hinaux H, Retaux S. Restoring eye size in Astyanax mexicanus blind cavefish embryos through modulation of the Shh and Fgf8 forebrain organising centres. Development. 2011;138:2467–2476. doi: 10.1242/dev.054106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prickett AR, Barkas N, McCole RB, Hughes S, Amante SM, Schulz R, Oakey RJ. Genome-wide and parental allele-specific analysis of CTCF and cohesin DNA binding in mouse brain reveals a tissue-specific binding pattern and an association with imprinted differentially methylated regions. Genome Res. 2013;23:1624–1635. doi: 10.1101/gr.150136.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden CM, Powner MB, Carr AJ, Smart MJ, da Cruz L, Coffey PJ. Stem cells in retinal regeneration: past, present and future. Development. 2013;140:2576–2585. doi: 10.1242/dev.092270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Borkent M, Hochedlinger K. A reprogrammable mouse strain from gene-targeted embryonic stem cells. Nature methods. 2010;7:53–55. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JM, Stadler MB, Cepko CL. Individual retinal progenitor cells display extensive heterogeneity of gene expression. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JM, Stadler MB, Roska B, Billings N, Sun B, Bartch B, Cepko CL. Molecular heterogeneity of developing retinal ganglion and amacrine cells revealed through single cell gene expression profiling. J Comp Neurol. 2007;502:1047–1065. doi: 10.1002/cne.21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Maurano MT, Qu H, Varley KE, Gertz J, Pauli F, Lee K, Canfield T, Weaver M, Sandstrom R, et al. Widespread plasticity in CTCF occupancy linked to DNA methylation. Genome Res. 2012;22:1680–1688. doi: 10.1101/gr.136101.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X, Gutierrez C, Xue T, Hampton C, Vergara MN, Cao LH, Peters A, Park TS, Zambidis ET, Meyer JS, et al. Generation of three-dimensional retinal tissue with functional photoreceptors from human iPSCs. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4047. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.