Abstract

South Africa was the largest recipient of funding from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) for antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs from 2004–2012. Funding decreases have led to transfers from hospital and non-governmental organization-based care to government-funded, community-based clinics. We conducted semi-structured interviews with 36 participants to assess patient experiences related to transfer of care from a PEPFAR-funded, hospital-based clinic in Durban to either primary care clinics or hospital based clinics. Participant narratives revealed the importance of connectedness between patients and the PEPFAR-funded clinic program staff, who were described as respectful and conscientious. Participants reported that transfer clinics were largely focused on dispensing medication and on throughput, rather than holistic care. Although participants appreciated the free treatment at transfer sites, they expressed frustration with long waiting times and low perceived quality of patient-provider communication, and felt that they were treated disrespectfully. These factors eroded confidence in the quality of the care. The transfer was described by participants as hurried with an apparent lack of preparation at transfer clinics for new patient influx. Formal (e.g., counseling) and informal (e.g., family) social supports, both within and beyond the PEPFAR-funded clinic, provided a buffer to challenges faced during and after the transition in care. These data support the importance of social support, adequate preparation for transfer, and improving the quality of care in receiving clinics, in order to optimize retention in care and long-term adherence to treatment.

Keywords: South Africa, HIV, ART, Decentralization, PEPFAR, Transitions in care

INTRODUCTION

South Africa is the country with both the most HIV-infected citizens globally (6 million individuals) (Shisana et al., 2014), and the greatest number of people on antiretroviral therapy (ART) - nearly 2.6 million (“UNAIDS Gap Report,” 2014). As the Government continues to expand its national program, funding from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has decreased (Collins & Beyrer, 2013; Institute of Medicine, 2013; Katz, Bassett, & Wright, 2013; “SAG-USG Partnership. Partnership framework in support of South Africa’s national HIV & AIDS and TB response, 2012–2017,” UNAIDS, 2012).

As part of this transition, treatment programs across South Africa are transferring patients from non-governmental organizations, many of which were in hospital based facilities, to government-sponsored, nurse-led primary health clinics (“The South African Antiretroviral Treatment guidelines,” 2013). Few studies have examined what happens to HIV-infected individuals who transfer care as part of PEPFAR’s cost reductions (Freeman et al., 2014). Data are critical to provide information about the barriers that patients face as they move into new forms of care, especially if the South African government hopes to maintain the long-term benefits of expanding ART coverage for universal access (Bendavid, Holmes, Bhattacharya, & Miller, 2012; Martinson et al., 2009; Ventelou et al., 2012) and to optimize treatment of HIV-infected individuals as a form of prevention to uninfected partners (Cohen et al., 2011).

We conducted a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the rapid transfer of patients from a large PEPFAR-funded, hospital-based clinic in Durban, to government-funded, community-based clinics in 2012. Our prior quantitative study estimated that nearly 20% of patients may not have linked to care and may have experienced a treatment interruption (Cloete et al., 2014). The qualitative study presented here was performed to assess potential reasons for these findings, including patient perceptions of the transfer process and factors impacting continued care engagement.

METHODS

Study Site and Transfer Process

We performed a qualitative study in November 2013, using semi-structured interviews with 36 patients who had been transferred to community-based clinics from Sinikithemba, which was considered a Centre of Excellence in HIV care, at McCord Hospital. A PEPFAR-funded site since 2004, it was one of the largest providers of ART in Durban, initiating over 10,000 patients on ART in 13 years.

Sinikithemba was required to transfer all patients between March and the end of June 2012, during which patients visiting the clinic underwent a group counseling session explaining the clinic closure and transfer procedures (Cloete et al., 2014). Patients were transferred to primary healthcare clinics, community health centers, or were referred to hospital-based clinics based on their ART regimen or co-morbid conditions.

Sampling and Recruitment

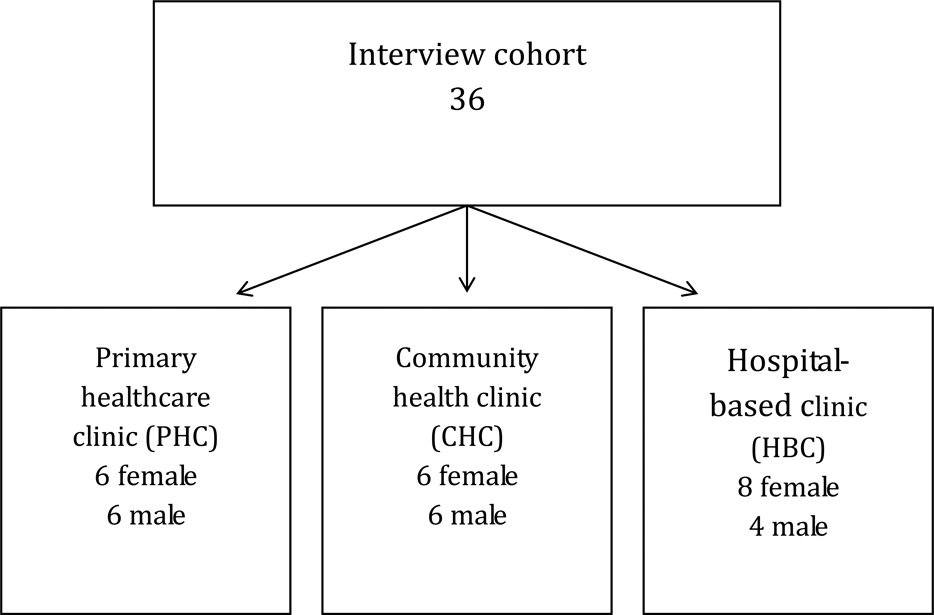

We randomly selected participants, stratified by gender, within each type of transfer facility to (primary health care clinic, community health centers, hospital-based clinic – Figure 1) (Creswell, 1997). Our goal was to explore if site of referral affected patients’ experiences with the transition and willingness to continue to engage in care.

Figure 1.

Interview Cohort

Eligibility Criteria

Patients were eligible if they were: (1) ≥18 years-old (2) transferred from Sinikithemba ART clinic; (3) gave informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the McCord Hospital Research Ethics Committee (Durban, South Africa) and the Partners Human Research Committee (2012-P-001122/1, Boston, MA). All participants provided oral informed consent.

Data Collection and Preparation

Data were collected via semi-structured, 30–60 minute telephone interviews. Participants were reimbursed 100 ZAR (~$10 U.S.). Qualitative protocol topics are listed in Table 1. Interviews were conducted in English or Zulu, based on participant preference. All interviews were audio-recorded with permission, and were transcribed and translated to English. All transcripts were reviewed for quality by I.T.K., L.M.B., M.R.G., and I.V.B.

Table 1.

Qualitative protocol for understanding patients’ experiences with PEPFAR-associated transitions in care in South Africa

| Question topic | Question example |

|---|---|

| Experiences and perceptions related to preparation for the transfer |

|

| Perceptions of care at the new clinic |

|

| Comparison of Sinkithemba care to the current clinic experience |

|

| Psychosocial Challenges |

|

Data Analysis

Three team members began an inductive analysis with a detailed review of all transcripts. We used a 3-stage analytic strategy with open and axial coding, followed by selective coding, to reflect relationships between codes (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In the deductive phase of coding, we developed a codebook, organized according to the hierarchy developed through axial coding and guided by our research question. We used QSR International’s NVivo 9 software to aid in organizing categories. We assigned labels to each category, and identified illustrative quotes from transcripts. We ensured trustworthiness of the data by having two authors independently code the same 20% of transcripts (MRG, DL), overseen by the first author. Inter-rater consistency was very good across major themes (≥0.70; Mean=0.77, range=0.71–0.90) (J. Cohen, 1960).

RESULTS

Themes were organized by tangible or structural, healthcare-associated, interpersonal, and transfer-related factors. Overall, participants described Sinikithemba’s structure as caring and cohesive. In contrast, patients recounted challenges to continuing care at the transfer clinic, including long wait times, lack of services, and poor relationships with clinic staff and providers. Experiences were generally consistent across transfer facility type.

Tangible or structural factors

Most participants did not cite structural barriers to care at their new clinic, appreciating the proximity and lack of medication-related fees. However, participants also reported that they would be willing to travel further and pay a fee if it meant that they could return to their prior clinic, where they perceived a higher standard of care:

“I was paying at Sinikithemba, but at the end of the day money was not a big deal compared to your life… I don’t pay here, [but] I‘d rather be in a place where I will pay…and still get the right service.” - Female, Referred to Hospital-Based Clinic

Ultimately, paying for care at Sinikthemba was seen as a part of enhanced care, and receiving free care did not outweigh the benefits that came from a semi-private facility.

Healthcare-associated systems factors

Patients described a system of comprehensive care at Sinikithemba and positive long-term relationships with providers. In contrast, they felt ignored by government clinic staff and frustrated with long wait-times, often missing work while waiting to be seen. Many perceived new clinic staff infantilized them and treated them poorly:

“Where I am, they just don't care. The attitude they have is that we are sick, even our minds don't work well… They undermine us. They talk to you as if you are stupid or you are a small child… They should learn how to talk and respect other people." – Male, Referred to Hospital Based Clinic

Many participants accepted this as the new standard, while others described feeling nostalgic for Sinikithemba.

Interpersonal/psychosocial factors

Participants described feelings of loss, missing their community of peers and advocates in the move, while experiencing discrimination at their new facilities. Participants voiced fears about being identified by community members at local clinics, who might then ostracize them. Familial and peer social support provided a buffer against these forces and enabled participants to overcome internalized stigma as well as challenges at new facilities:

“There are times where you can find yourself being discouraged, but it is important to disclose your status to your family so that they will support you…When my alarm rings, my children alert me and they bring me water to take my medication and that makes me feel good.”- Male, Referred to a Community-Health Clinic

Transfer process

The transfer process itself was challenging. Most felt it was chaotic and faster than they would have liked, which left them feeling alone without the support they previously had experienced. Participants who felt least prepared were often those who were concerned that the new clinic would not provide the same level of support to which they had grown accustomed:

“We did not anticipate that the clinic would come to that situation. We were not aware that the good care that we were receiving was because of the support they were getting from the funders. So if the funders stopped giving help, there was nothing they could do as well.” - Male, referred to Primary Health Clinic

DISCUSSION

Participant narratives revealed the importance of relationships between patients and clinic staff at Sinikithemba, which were described as respectful and conscientious. Participants reported that transfer clinics were focused on dispensing medication and throughput, rather than holistic care. These factors eroded confidence in the quality of the care. Formal counseling on transitioning and ongoing social support provided a buffer to challenges faced during and after the transition.

South Africa is at a critical juncture as multinational funding priorities shift, and the Government takes full control of caring for people living with HIV. Given antiretroviral coverage rates were at 55% in 2010 and incidence rates were approximately 2% per annum (Mayosi et al., 2012), this will ensure a growing demand for effective treatment for the foreseeable future (“WHO | Progress report 2011,” 2011), compounded by the 2015 adoption of the WHO guidelines recommending ART initiation at CD4+ count ≤500 cells/mm3 (“Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection,” 2013).

Research related to the decentralization process is critical to understanding factors driving engagement in care in South Africa. We believe our study is the first to qualitatively analyze patient perceptions of the decentralization process in its immediate aftermath. Prior research on this topic has been focused on understanding patient perceptions of potential challenges they could face if and when they transferred (Gilbert & Walker, 2010). Our prior research found that HIV-related stigma undermines ART adherence by compromising adaptive coping and social support (Katz, Ryu, et al., 2013). Therefore, concerns about stigma and disclosure in decentralized clinics may have implications for care retention.

Our quantitative work identified early losses in the transfer process. This qualitative study helps to clarify why these losses may be occurring. Transfer clinics, while providing free care within the community, were often seen as overcrowded and unable to provide adequate support. This finding is consistent with our recent research focused on understanding why ART-eligible patients may choose not to engage in care, and the need for psychosocial support for individuals who may perceive too many barriers to accessing treatment (Katz et al., 2014).

Despite these challenges, prior research has shown that patients have successfully transitioned to a decentralized system of care in South Africa, with particular success at primary health centers (compared to district and regional hospitals) (Bedelu, Ford, Hilderbrand, & Reuter, 2007; Fatti, Grimwood, & Bock, 2010; Fredlund & Nash, 2007). Given shortages of health care workers and the decreasing funding, there is a need to broaden HIV care, so that it can reach all those in need. This will require integration of services, health system strengthening, improving the general quality of care provided at primary care clinics and support for individuals who transfer care.

There are several study limitations. Patients paid a monthly fee for care at the Sinikithemba and therefore may not be representative of patients seeking care in the public sector. In addition, only patients who linked to care were interviewed. Therefore, we do not have data on patients who were lost to care after the transfer process. Despite this, we were able to elicit concerns about the transfer process and provide a detailed understanding of factors that may be driving decision-making among people living with HIV in South Africa. Finally, an inherent limitation of qualitative research is a relatively small sample size, given the focus on the in-depth exploration of themes.

In conclusion, transitions in care are a necessary component of shifting PEPFAR funds in South Africa. These data support the importance of social support, adequate preparation for transfer, and improving the quality of care in receiving clinics, in order to optimize retention in care and long-term adherence to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support Information: This work was supported by: R01 MH090326-04S1; K23 MH097667; P30 AI060354

Footnotes

These data were presented at The 9th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence in Miami, Florida, June 8–10, 2014.

No authors on this manuscript have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abdool Karim SS, Churchyard GJ, Karim QA, Lawn SD. HIV infection and tuberculosis in South Africa: an urgent need to escalate the public health response. Lancet. 2009;374(9693):921–933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60916-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedelu M, Ford N, Hilderbrand K, Reuter H. Implementing antiretroviral therapy in rural communities: the Lusikisiki model of decentralized HIV/AIDS care. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S464–S468. doi: 10.1086/521114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendavid E, Holmes CB, Bhattacharya J, Miller G. HIV development assistance and adult mortality in Africa. JAMA. 2012;307(19):2060–2067. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloete C, Regan S, Giddy J, Govender T, Erlwanger A, Gaynes MR, Bassett IV. The Linkage Outcomes of a Large-scale, Rapid Transfer of HIV-infected Patients From Hospital-based to Community-based Clinics in South Africa. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2014;1(2):ofu058. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, HPTN 052 Study Team Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Beyrer C. Country ownership and the turning point for HIV/AIDS. The Lancet. Global Health. 2013;1(6):e319–e320. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. 2013 Jun; Retrieved November 3, 2014, from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/en/ [PubMed]

- Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. 1st edition. Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fatti G, Grimwood A, Bock P. Better antiretroviral therapy outcomes at primary healthcare facilities: an evaluation of three tiers of ART services in four South African provinces. PloS One. 2010;5(9):e12888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredlund VG, Nash J. How far should they walk? Increasing antiretroviral therapy access in a rural community in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S469–S473. doi: 10.1086/521115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman A, Kiumbu M, Mwamba B, Atibu J, Mukumbi H, Mwila L, Newman JE. Patient Outcomes in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo After a Disruption in HIV Care Due to Decreased Global Fund Appropriations. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(11):2135–2143. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0761-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L, Walker L. “My biggest fear was that people would reject me once they knew my status..”: stigma as experienced by patients in an HIV/AIDS clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2010;18(2):139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Evaluation of PEPFAR - Brief Report. 2013 Feb; Retrieved November 3, 2014, from http://www.iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/PEPFAR/PEPFAR_RB.pdf.

- Katz IT, Bassett IV, Wright AA. PEPFAR in transition--implications for HIV care in South Africa. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2013;369(15):1385–1387. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz IT, Dietrich J, Tshabalala G, Essien T, Rough K, Wright AA, Ware NC. Understanding Treatment Refusal Among Adults Presenting for HIV-Testing in Soweto, South Africa: A Qualitative Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0920-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Tsai AC. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(3) Suppl 2 doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson N, Mohapi L, Bakos D, Gray GE, McIntyre JA, Holmes CB. Costs of providing care for HIV-infected adults in an urban HIV clinic in Soweto, South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2009;50(3):327–330. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181958546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayosi BM, Benatar SR. Health and health care in South Africa--20 years after Mandela. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(14):1344–1353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1405012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayosi BM, Lawn JE, van Niekerk A, Bradshaw D, Abdool Karim SS, Coovadia HM, Lancet South Africa team Health in South Africa: changes and challenges since, 2009. Lancet. 2012;380(9858):2029–2043. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAG-USG Partnership. Partnership framework in support of South Africa’s national HIV & AIDS and TB response. 2012–2017 (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2014, from http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/153124.pdf.

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, Onoya D. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey. Human Sciences Research Council Press. 2014 doi: 10.2989/16085906.2016.1153491. Retrieved from http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/4565/SABSSM%20IV%20LEO%20final.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- South Africa Department of Heath. Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list for South Africa. 2012 Retrieved October 30, 2014, from www.kznhealth.gov.za/pharmacy/edladult_2012.pdf.

- Strauss AC, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Second Edition: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The South African antiretroviral treatment guidelines. 2013 Mar; Retrieved November 3, 2014, from http://www.sahivsoc.org/upload/documents/2013%20ART%20Guidelines-Short%20Combined%20FINAL%20draft%20guidelines%2014%20March%202013.pdf.

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS. Country ownership for a sustainable AIDS response: from principles to practice. 2012 Jul; Retrieved November 3, 2014, from http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2012/20120717_JC2134_UNAIDS_Country_Ownership_Discussion_Paper.pdf.

- UNAIDS Gap Report. 2014 Jul; Retrieved November 2, 2014, from http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

- Ventelou B, Arrighi Y, Greener R, Lamontagne E, Carrieri P, Moatti J-P. The macroeconomic consequences of renouncing to universal access to antiretroviral treatment for HIV in Africa: a micro-simulation model. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e34101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside A. South Africa’s Key Health Challenges. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2014;652(1):166–185. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Progress report 2011: Global HIV/AIDS response. 2011 Nov 30; Retrieved November 3, 2014, from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/en/