Abstract

Adsorption of fibrinogen on the luminal surface of biomaterials is a critical early event during the interaction of blood with implanted vascular graft prostheses which determines their thrombogenicity. We have recently identified a nanoscale process by which fibrinogen modifies the adhesive properties of various surfaces for platelets and leukocytes. In particular, adsorption of fibrinogen at low density promotes cell adhesion while its adsorption at high density results in the formation of an extensible multilayer matrix, which dramatically reduces cell adhesion. It remains unknown whether deposition of fibrinogen on the surface of vascular graft materials produces this anti-adhesive effect. Using atomic force spectroscopy, single cell force spectroscopy, and standard adhesion assays with platelets and leukocytes, we have characterized the adhesive and physical properties of the contemporary biomaterials, before and after coating with fibrinogen. We found that uncoated PET, PTFE and ePTFE exhibited high adhesion forces developed between the AFM tip or cells and the surfaces. Adsorption of fibrinogen at the increasing concentrations progressively reduced adhesion forces, and at ≥2 µg/ml all surfaces were virtually nonadhesive. Standard adhesion assays performed with platelets and leukocytes confirmed this dependence. These results provide a better understanding of the molecular events underlying thrombogenicity of vascular grafts.

Keywords: Adsorption, Fibrinogen, Thrombogenicity, Vascular graft, Platelet Adhesion, Hemocompatibility

1. Introduction

It is widely recognized that after implantation, prosthetic vascular grafts spontaneously acquire a layer of adsorbed plasma proteins. Among them, fibrinogen has received the most attention because of its high concentration in the circulation (2–3 mg/ml), quick adsorption on various surfaces, and ability to support integrin-mediated adhesion of platelets and leukocytes. Since one of the primary graft failures is adhesion-dependent platelet activation and thrombus formation, fibrinogen is generally viewed as a culprit. Consequently, considerable research effort has been made to create nonfouling materials that resist protein adsorption and platelet adhesion (Reviewed in (1–3)). In addition, innumerable in vitro studies have focused on the mechanisms of fibrinogen adsorption in an attempt to understand its thrombogenic potential [(4–10) and references therein]. Paradoxically, other studies have focused on the design of anti-thrombogenic vascular grafts utilizing fibrin(ogen)-coated surfaces with apparently beneficial results in animal studies and in humans (11–14).

Intact fibrinogen deposited on various surfaces is indeed adhesive for platelets and leukocytes, but only when adsorbed at certain concentrations and, especially, when cell adhesion is tested in buffers without fibrinogen (15–19). Furthermore, fibrin, a clotting product of fibrinogen, mediates strong adhesion of blood cells suspended in protein-free buffers (17,19–22). From these in vitro observations, it is expected that fibrinogen, which is deposited early after vascular graft implantation, should support rapid accumulation of platelets. Likewise, fibrin, which is eventually formed and remains on the surface of grafts implanted in humans over the years, should promote platelet deposition and activation. This, in turn, would be expected to result in the continuous thrombus propagation and vascular occlusion. However, the flow surface of vascular grafts is highly thrombogenic only during the early postoperative period (23–25). Subsequently, graft maturation results in a nonthrombogenic surface (25–27), which sustains its characteristic acellular appearance over the decades in spite of the presence of the stable fibrin lining (28–31). These observations suggest the existence of natural anti-adhesive mechanisms operating on the flow surface of mature vascular graft prostheses that prevent the accumulation of blood cells. The crucial question as to why platelets adhere to fibrinogen deposited on the surface of vascular grafts early after implantation but not attach to the, likewise, highly adhesive fibrin present on mature grafts remains open.

In recent reports we described a new nanoscale phenomenon whereby adsorption of fibrinogen on various surfaces, including fibrin clots, dramatically reduces cell adhesion. In particular, we showed that the ability of fibrinogen to support cell adhesion strikingly depends on its coating concentration. Counter-intuitively, while low-density fibrinogen is highly adhesive for platelets and leukocytes, its adsorption at the increasing concentrations reduces cell adhesion under both static and flow conditions (19,22). This effect is specific for fibrinogen since no other plasma proteins exhibit this unusual behavior (19). The underlying mechanism by which fibrinogen renders surfaces nonadhesive is its surface-induced unfolding and self-assembly leading to the formation of a nanoscale (~10 nm) multilayer matrix (22,32). The fibrinogen matrix is extensible and characterized by weak adhesion forces, which makes it incapable of transducing strong mechanical forces via cellular integrins, resulting in weak intracellular signaling and infirm cell adhesion (22,32,33). In contrast, fibrinogen deposited at low concentrations produces a single molecular layer in which molecules are directly attached to the surface. The monolayer is characterized by high adhesion forces that transduce strong outside-in signaling in platelets leading to firm adhesion (22). It remains unknown whether this behavior is observed when fibrinogen is adsorbed on the surface of vascular graft materials.

In this study, employing atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based force spectroscopy, single cell force spectroscopy (SCFS) and standard adhesion assays with platelets and leukocytes, we examined the adhesive and physical properties of two materials, PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) and PET (polyethylene terephthalate) used for the production of contemporary vascular grafts, before and after adsorption of fibrinogen. We show that in spite of the high adhesion forces exhibited by uncoated biomaterials and when coated with low fibrinogen concentrations, adsorption of fibrinogen at higher concentrations renders the surfaces virtually nonadhesive for platelets and leukocytes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Human fibrinogen depleted of fibronectin and plasminogen was obtained from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Fibrinogen was treated with iodoacetamide to inactivate the residual Factor XIII and then dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Fibrinogen was labeled with 125-Iodine using IODO-GEN (Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, IL), dialyzed against PBS and stored at −20 °C. The concentration of fibrinogen was determined by spectrophotometry at 280 nm using the extinction coefficient 1.51 at 1 mg/ml. Polyclonal antibodies against human fibrinopepetide A was obtained from Assypro (St. Charles, MO). Calcein AM was purchased from Molecular Probes (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The following biomaterials were used in this study: (1) Mylar™, a non-crystalline form of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) purchased as films (type A, 0.127-mm thick) from Cadillac Plastic and Chemical (Birmingham, MI); (2) polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) was obtained as a 0.0508-mm sheet from Professional Plastics (Fullerton, CA); and (3) Impra® ePTFE (expanded PTFE; intermodal distance 30 µm) vascular graft was obtained from Bard Peripheral Vascular Inc. (Tempe, AZ) in the form of vascular graft tubing with a diameter of 7 mm.

2.2. Cells

Human embryonic kidney 293 cells stably expressing leukocyte integrin Mac-1 (HEK-Mac-1) have been described previously (34,35). The cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Before each experiment, cells were detached from the flasks using the cell dissociation buffer (Cellgro, Mediatech Inc., Manassas, Virginia), washed twice in Hank’s Balanced Salt solution (HBSS) containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ and resuspended in HBSS + 0.1% BSA. U937 monocytic cells were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Human platelets were isolated as described previously (36). Briefly, platelets were collected from fresh aspirin-free human blood in the presence of 2.8 µM prostaglandin E1, and isolated by differential centrifugation followed by gel filtration on Sepharose 2B in divalent cation-free Tyrode’s buffer (pH 7.2) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% glucose. The present work was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Arizona State University.

2.3. Surface Preparation for AFM and SCFS

The PET and PTFE sheets were cut into small squares and rinsed with methanol, ethanol, and deionized water. The ePTFE samples were prepared from the vascular graft tubing by cutting squares of the same size. The samples for AFM and SCFS were cut into 6×6 mm squares and prepared by adsorption of different concentrations of fibrinogen (0.05–20 µg/ml) in PBS onto the biomaterial surfaces for 3 h at 37 °C.

2.4. Atomic Force Microscopy-based Force Spectroscopy

Force-distance measurements on fibrinogen coated substrates of biomaterials were performed in PBS at 37 °C using an MFP-3D atomic force microscope (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) as described (32,33). Silicon nitride probes (MLCT, Veeco Probes, Camarillo, CA) with nominal spring constants in the range of 10–15 pN/nm were used. Cantilevers were plasma-cleaned in oxygen plasma for 40 sec before use. The surfaces coated with different concentrations of fibrinogen were probed using a force trigger of 600 pN and an approach and retract speed of 2 µm/s. Force-distance curves were acquired in 64×64 arrays of 5×5 µm2 areas. For each concentration of fibrinogen three arrays at different areas on the surface were probed (12288 force-distances per coating concentration). Spring constants for each cantilever were determined using built-in Thermal method. Each curve was analyzed by a custom program written in IGOR Pro 6 (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR), which calculates adhesion forces. To obtain mean values of these parameters, the data were fitted using log-normal distributions.

2.5. Single Cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS)

Cantilevers for SCFS measurements were prepared as previously described (32). Briefly, tipless cantilevers with nominal spring constants of 0.035 N/m (HYDRA6R-200NG-TL, AppNano, Santa Clara, CA) were functionalized with (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES). After washing, the cantilevers were incubated in 1.25 mM Bis (ssulfosucccinimidil) suberate (BS3; Sigma) solution for 30 min at 22 °C and then placed into 0.5 mg/ml concanavalin A (Sigma) solution for 30 min at 22 °C. Cantilevers were then rinsed with PBS and stored in 1 M NaCl at 4 °C. SCFS measurements were performed in HBSS with 0.1% BSA at 37 °C. Integrin Mac-1-expressing HEK293 cells were pipetted into the custom-made AFM chamber and a single cell was instantly picked up from the glass surface by pressing on a cell with a cantilever using a contact force of 500–2000 pN for 5–30 sec. After that, the cell was lifted from the surface, allowed to attach firmly to the cantilever for 5–10 min and then lowered onto the fibrinogen coated biomaterial. The biomaterials coated with different concentrations of fibrinogen were probed using a 1 nN force trigger, an approach and retract speed of 2 µm/s, and a 120 s dwell time on the surface. After the trigger force was reached, the z position was kept constant. After each force measurement, a cell was allowed to recover for at least 5 min before the next cycle. As monitored optically, the cells always detached from the fibrinogen substrate but not from the cantilever during pulling. Cell detachment was indicated by the superposition of trace and retrace baselines over the pulling range (25–35 µm).

2.6. Confocal microscopy

ePTFE was coated with fibrinogen (20 µg/ml) and incubated with calcein-labeled platelets for 30 min at 37 °C. The samples were stained with anti-fibrinogen mAb FPA followed by Alexa 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Confocal images were taken using a confocal microscope (Leica TSC SP5, Buffalo Grove, IL) at excitation wavelengths of 488 (green: platelets) and 647 (red: fibrinogen).

2.7. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

PET, PTFE, and ePTFE samples were precoated by a standard sputtering technique with Au-Pd alloy. Samples were observed using a JEOL JSM6300 (Tokyo, Japan) scanning electron microscope. In selected experiments, PET was coated with different concentrations of fibrinogen on which platelets (1×107/mL) were allowed to adhere. After 30 min incubation at 37°C, samples were washed, fixed with 2% gluteraldehyde, and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 h each at 22 °C. Samples were dehydrated and then dried through the critical point drying of CO2, mounted onto aluminum stubs, and sputter coated with palladium-gold (approximately 5 nm) in a sealed vacuum. The samples were observed using a JEOL JSM6300 microscope.

2.8. Standard Cell adhesion Assays

The biomaterial surfaces were freshly cut into squares (9×9 mm), cleaned with methanol, ethanol and deionized water, and placed into 24-well plates. The biomaterials were incubated with different concentrations of fibrinogen for 3 h at 37 °C. 3 mL of calcein-labeled U937 cells (1 × 106/mL) or calcein-labeled platelets (1 × 107/mL) in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) or Tyrode’s buffer, respectively, containing 0.1% BSA were added to the surfaces. After 30 min incubation at 37 °C, the non-adherent cells were removed by dipping the surfaces into PBS. Photographs of five random fields for each surface were taken with the 20× and 40× objectives of a Leica DM4000B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL), and the number of adherent cells was counted. In selected experiments, adherent U937 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min, then washed with PBS and incubated with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin to stain for the actin cytoskeleton.

2.9. Statistical analyses

Statistical significance of differences between mean values for various conditions has been assessed using a Student’s t-test, with p ≤0.05 considered as statistically significant. For SCFS, statistical significance between median values for different samples was evaluated using a Mann-Whitney U test, with p <0.05 considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Selected Biomaterials by Scanning Electron Microscopy

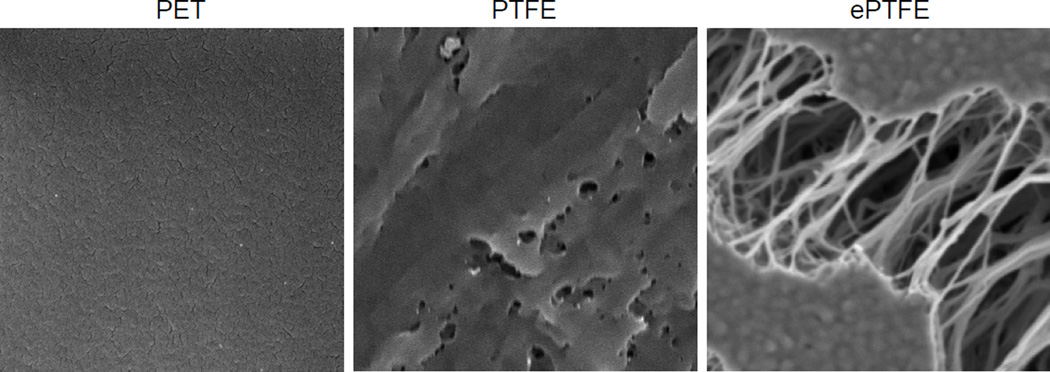

To assess how fibrinogen might modify the adhesive properties of biomaterials, we have selected two commonly used materials: polyethylene terephthalate (PET or Dacron) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE). Since an uneven surface of woven or knitted Dacron used in commercial grafts may complicate the AFM-based force spectroscopy analyses, we have used smooth flat sheets made of solid PET which mimics the chemical and mechanical properties of the vascular graft material (37). Likewise, the flat sheets made of PTFE were shown to imitate the chemical properties of ePTFE used for the production of vascular tubes having a complex three-dimensional structure (37). Scanning electron microscopy of the test materials showed the differences in the surface architecture of PET and PTFE (Fig. 1). The figure also shows the typical structure of ePTFE with irregular-shaped flat islands (known as “nodes”) and a dense meshwork of fine fibers stretching between the nodes.

Fig. 1. Scanning electron microscopy images of biomaterial surfaces.

The PET, PTFE and ePTFE surfaces were prepared for SEM as described in Materials and Methods.

3.2. Adhesion Forces Developed by Uncoated and Fibrinogen-Coated Biomaterials Determined by Force Spectroscopy

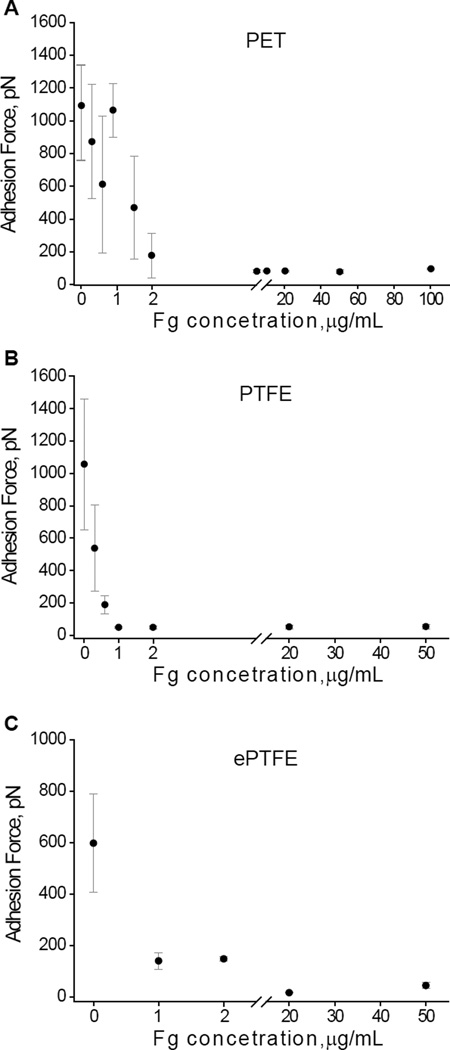

Adhesion forces of the surfaces before and after adsorption of different concentrations of fibrinogen were probed using an unmodified AFM tip. The strongest adhesion forces were observed between the AFM tip and uncoated materials (Fig. 2A–C). Among the materials, both PET and PTFE displayed higher adhesion forces (~1100 pN) compared to ePTFE (~600 pN). Because of the complex architecture, the adhesion forces on ePTFE were measured on the surface of nodes and found to be 596±191 pN. The ~1.7-fold difference in adhesion forces between naked PTFE and ePTFE is not clear since both are made of chemically identical material, but potentially may arise from the ePTFE’s modification during manufacturing. As expected, the increase in the fibrinogen coating concentrations resulted in the decrease of adhesion forces for all three materials. In agreement with previous data obtained on mica and glass (32), the steep decrease of adhesion forces occurred in a very narrow range of fibrinogen coating concentrations (0–1 µg/ml for PTFE and ePTFE) and 0–2 µg/ml for PET. At the concentrations ≥1–2 µg/ml, the adhesion forces reduced by ~6-, 40- and 3-fold for PET, PTFE, and ePTFE, respectively, compared to uncoated surfaces. The subsequent increase in the concentration of fibrinogen up to 50–100 µg/ml did not produce an additional decrease in the adhesion forces for PTFE, although it further decreased adhesion forces for PET and ePTFE. These results indicate that regardless of the initial adhesiveness of uncoated surfaces, the deposition of fibrinogen results in a dramatic drop of adhesion forces making the surface of biomaterials virtually nonadhesive.

Fig. 2. Force spectroscopy analyses of the surfaces prepared by adsorption of fibrinogen on biomaterials.

Most probable adhesion forces between an unmodified AFM tip and fibrinogen coated biomaterials plotted as a function of the fibrinogen coating concentration adsorbed on PET (A), PTFE (B) and ePTFE (C). The data shown are the means ± SD from three to four experiments with 12288–16384 force-distance curves collected from the force maps for each concentration of fibrinogen. Fg, fibrinogen.

3.3. Adhesion of U937 monocytic cells and platelets to biomaterials examined by standard adhesion assays

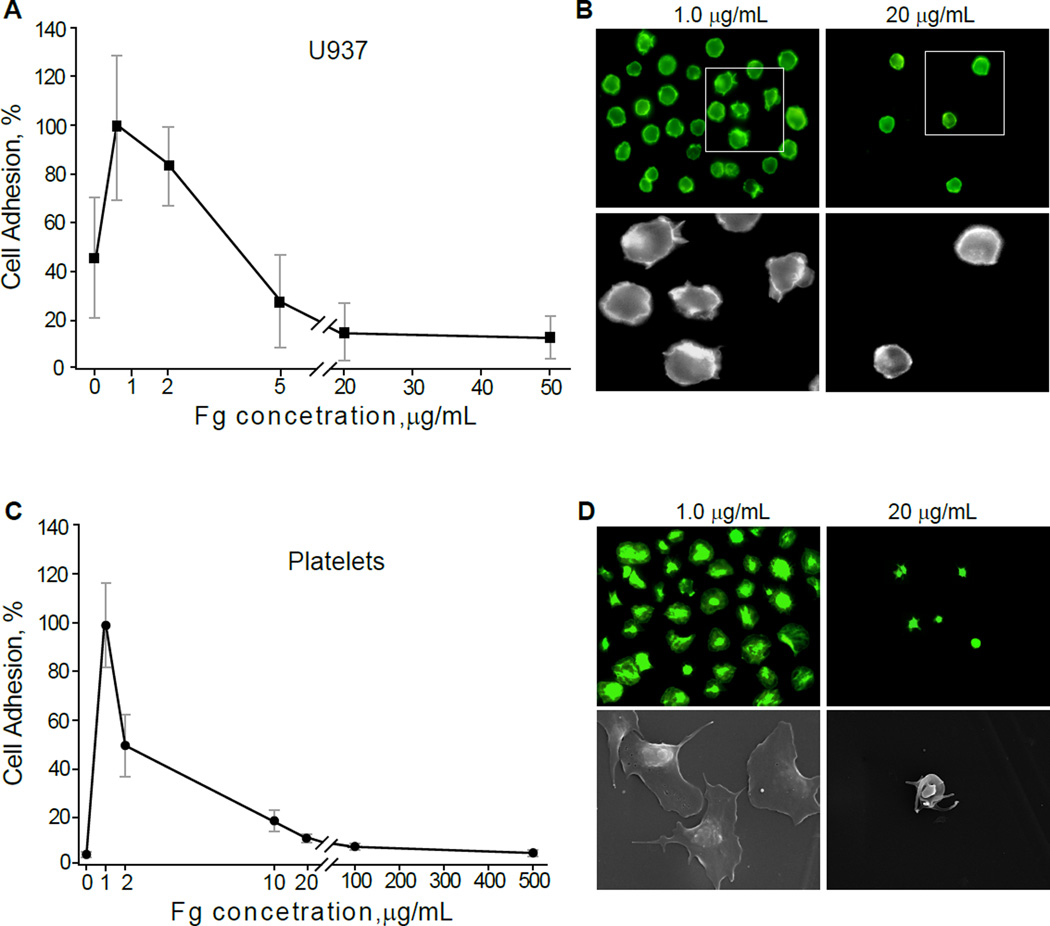

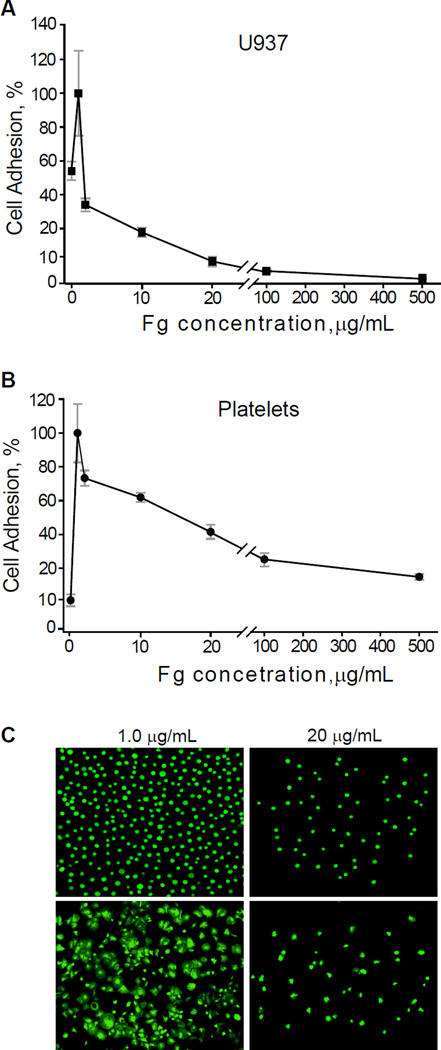

We previously showed a parallelism between the adhesion forces probed by AFM-based force spectroscopy and cell adhesion tested in standard adhesion assays (22,32,33). To examine whether adsorbed fibrinogen reduces integrin-mediated cell adhesion on biomaterials, we performed adhesion assays with platelets isolated from blood and U937 monocytic cells, a model cell line commonly used in lieu of peripheral blood monocytes. The surfaces were coated with increasing concentrations of fibrinogen and calcein-labeled platelets or U937 cells were allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37 °C. As shown in Figure 3A and 3B for U937 cells and in 3C and 3D for platelets, cell adhesion progressively declined as the coating concentration of fibrinogen adsorbed on the surface of PET increased. Furthermore, while U937 cells and platelets were spread on low-density fibrinogen (1.0 µg/ml), they remained round on surfaces coated with 20 µg/ml fibrinogen, underscoring a direct relationship between cell spreading and firm adhesion (Fig. 3B and 3D). Similar results were obtained using flat PTFE sheets (Fig. 4). The lack of correlation between the coating concentration of fibrinogen and cell adhesion was not due to the abnormal adsorptive capacity of PET and PTFE. Using 125I-labeled fibrinogen, we verified that deposition of protein on PET and PTFE followed a dose-dependent pattern (Fig. S1). Notable, however, was the lack of clear saturation of fibrinogen adsorption, which was observed on other surfaces (19) and may be attributed to a continuing assembly of the multilayer. Adhesion assays with fibrinogen-coated ePTFE were hampered by a nonuniform nature of the surface. It was found that many platelets and U937 cells were mechanically trapped within the meshwork of fibers connecting the nodes. Nevertheless, the results revealed that only few platelets adhered to the flat nodes (Fig. S2; shown for platelets). Thus, consistent with previous findings, fibrinogen adsorbed on the surface of biomaterials at low concentrations supports cell adhesion while high concentrations render the surfaces nonadhesive.

Fig. 3. Adhesion of U937 monocytic cells and platelets to fibrinogen-coated PET.

Different concentrations of fibrinogen were adsorbed on the surface of PET squares (9×9 mm) and calcein-labeled U937 cells (A) or platelets (C) were allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37 °C. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing, and adherent cells were quantified by taking pictures of five random fields with a 20× and 40× objectives. Three PET surfaces were prepared for each fibrinogen concentration. Adhesion is expressed as a percentage of maximal adhesion observed at 1 µg/ml. Data shown are means ± SD of three independent experiments with each cell type. (B) representative fluorescent images of U937 cells adherent to PET coated with 1 µg/ml (left panels) and 20 µg/ml (right panels) fibrinogen. Adherent U937 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min, and then washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin to stain for the actin cytoskeleton. (D) representative fluorescent (upper panels) or scanning electron microscopy (lower panels) images of platelets adherent to PET coated with 1 µg/ml (left panels) and 20 µg/ml (right panels) fibrinogen.

Fig. 4. Cell adhesion to fibrinogen-coated PTFE.

Calcein-labeled U937 cells (A) or platelets (B) were allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37 °C to PTFE squares (9×9 mm) coated with different concentrations of fibrinogen. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing and the number of adherent cells was quantified by taking pictures of five random fields, per each concentration of fibrinogen, with a 20× and 40× objectives. Cell adhesion is expressed as a percentage of maximal adhesion observed at 1 µg/ml. Data shown are means ± SD of three independent experiments with each cell type. (C) representative fluorescent images of U937 cells (upper panel) or platelets (lower panel) adherent to PTFE coated with 1 µg/ml (left panel) and 20 µg/ml (right panel) fibrinogen.

3.4. Single-cell Force Spectroscopy (SCFS)

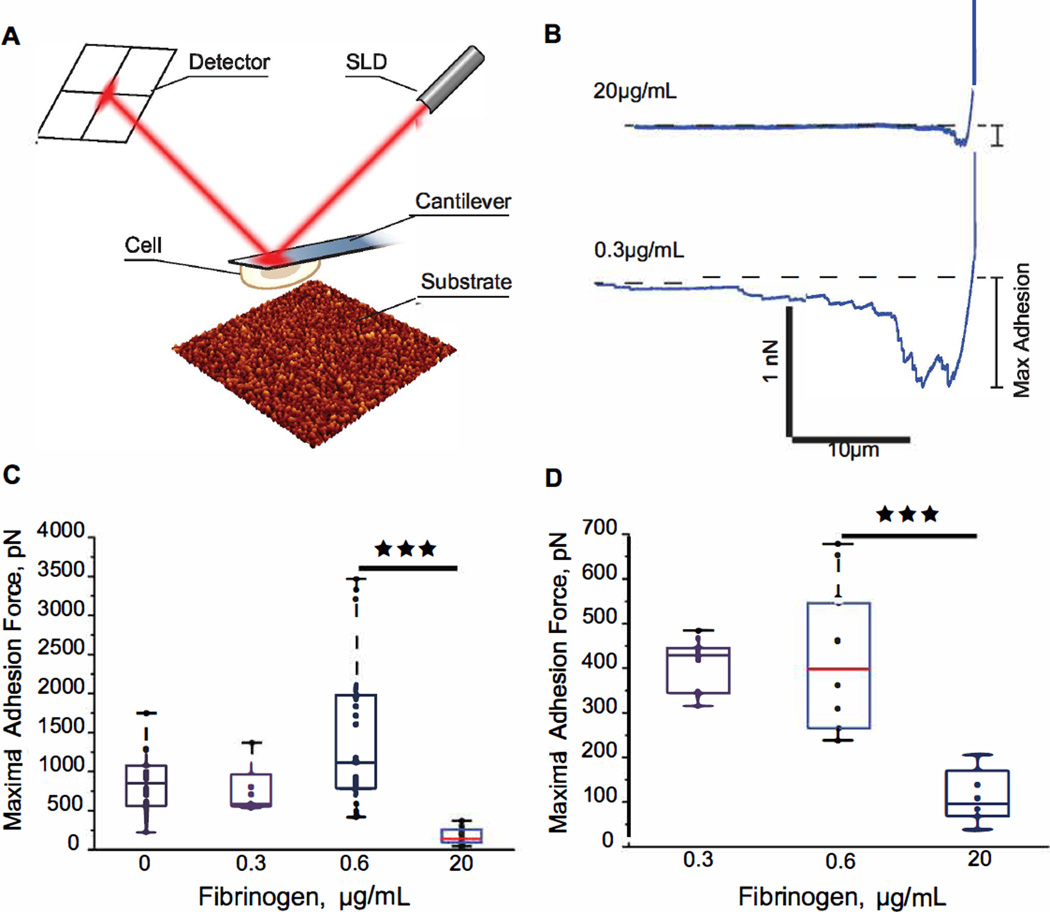

Although standard adhesion assays provide useful insights into the capacity of various substrates to support cell attachment, these analyses are largely qualitative. Therefore, we obtained quantitative data by measuring the maximal adhesion forces developed between cells and coated biomaterials using SCFS. In these analyses we used HEK293 cells stably expressing leukocyte integrin Mac-1 (αMβ2). This cell line was previously employed to characterize integrin Mac-1-dependent adhesion and to measure adhesion forces between cells and fibrinogen-coated mica (32). Single Mac-1-HEK cells were attached to a Con A-functionalized cantilever, and then each cell was brought into contact with uncoated or fibrinogen-coated PET and PTFE surfaces (Fig. 5A). Cells were pressed onto each surface with a force of 1 nN for 120 sec and then withdrawn with a constant speed of 2 µm/s. The maximal adhesion forces were determined from force-distance retraction curves (Fig. 5B). Figure 5C and 5D show box plots for the maximal forces required for cell detachment from uncoated PET and PTFE, respectively, and coated with low and high concentrations of fibrinogen. For uncoated PET, the median force was 773 pN. The 25th percentile was 487 pN, and the 75th percentile was 1001 pN (Fig. 5C). Adsorption of low concentrations of fibrinogen (0.3–0.6 µg/ml) did not alter significantly the median adhesion forces. However, when the coating concentration of fibrinogen increased to 20 µg/ml the median maximal force decreased to 138 pN with the 25th percentile at 93 pN and the 75th percentile at 262 pN, a ~6-fold decline compared to uncoated PET and PET coated with 0.3–0.6 µg/ml fibrinogen (Fig. 5C). The median adhesion force for cell adhesion to uncoated PTFE was smaller (417 pN) than those determined on uncoated PET surfaces (Fig. 5D) and did not change when PTFE was coated with 0.3 µg/ml fibrinogen. However, coating PTFE with 20 µg/ml fibrinogen resulted in a ~5-fold drop in the median adhesion force (84 pN). The direct measurement of adhesion forces between cellular integrins and fibrinogen substrates is in agreement with the data obtained using the AFM tip, thus, corroborating the idea that deposition of fibrinogen on the surface of biomaterials strongly decreases their adhesiveness for cells.

Fig. 5. Cell adhesion to fibrinogen substrates formed on the surface of PET and PTFE measured by SCFS.

(A) schematic representation of a cell attached to the cantilever during its approach to the fibrinogen matrix. (B) representative force-distance curves for the Mac-1-HEK cells brought into contact with fibrinogen adsorbed on PET at 0.3 and 20 µg/ml. Cells were pressed onto each surface with a force of 1 nN for 120 sec and then withdrawn with a constant speed of 2 µm/s. (C) maximal adhesion forces for cell adhesion to untreated PET, and PET coated with 0.3 µg/ml (2 cells, 9 curves), 0.6 µg/ml (8 cells, 30 curves) and 20 µg/ml (3 cells, 22 curves) fibrinogen solutions. (D) maximal adhesion forces for cell adhesion to untreated PTFE, and PTFE coated with 0.3 µg/ml (6 cells, 29 curves) and 20 µg/ml (4 cells, 28 curves) fibrinogen solutions. Adhesion forces are shown as the median (red lines) of each data set, and the top and bottom of the box represent the 75th and 25th percentile. ***, p<0.001.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we examined how adsorption of fibrinogen on the surface of two materials, PET and PTFE, used for the production of commercial vascular graft modifies their physical and adhesive properties. The principal finding of this work is that fibrinogen adsorbed at low concentrations (≤2 µg/ml) supports platelet and leukocyte adhesion, while adsorbed at higher concentrations fibrinogen makes the surfaces virtually nonadhesive. Furthermore, cell adhesion precipitously drops in a very narrow range of fibrinogen coating concentrations. These data are in agreement with previous observations obtained on other surfaces, including mica, glass, plastic and fibrin clots (19,22,33). Furthermore, examination of adhesive properties of fibrinogen-coated PET and PTFE using AFM force spectroscopy and SCFS is consistent with the data collected on other surfaces, i.e., adsorption of fibrinogen at increasing concentrations reduces the adhesion forces developed between the unmodified AFM tip or a cell and fibrinogen substrates. These findings indicate that adsorption of fibrinogen on biomaterials modify their physical and adhesive properties in a way similar to that observed on other surfaces, underscoring the generality of the fibrinogen-dependent anti-adhesive mechanism.

In previous studies we revealed the molecular basis for the differential cellular responses to low- and high-density fibrinogen adsorbed on various surfaces. In particular, we showed that adsorption of fibrinogen at low concentrations results in the formation of a molecular monolayer in which single molecules are directly attached to the surface (32). As the fibrinogen concentration increases, the molecules self-assemble through the interaction between their αC domains (33) which results in the formation of the multilayer matrix with a thickness of ~10 nm consisting of 7–8 molecular layers packed in the horizontal orientation (32,33). The monolayer and multilayer exhibit different adhesion forces when probed by AFM-based force spectroscopy and SCFS. The monolayer is highly adhesive for cells and develops high adhesion forces with the AFM tip. The greater cell adhesion observed on the monolayer arises as response to the resistance derived from the hard surfaces to which fibrinogen molecules are attached firmly. Thus, this substrate may not yield when cellular integrins or the AFM tip pull on it. Conversely, the multilayered fibrinogen matrix is characterized by weak adhesion forces and is incapable to support firm cell adhesion. The origin of the nonadhesive properties of the multilayer lies in its extensibility resulting from the separation of the molecular layers held by noncovalent interactions between the long flexible αC regions of fibrinogen (33). The multilayer is incapable of transducing strong mechanical forces via integrin receptors; hence, when platelet integrins pull on the multilayer matrix it yields to the pulling force resulting in weak intracellular signaling, cell spreading, and adhesion (22). The inability of platelets or leukocytes to firmly adhere and consolidate their grip on the extensible matrix leads to their detachment under flow. In spite of its nanoscale nature, the fibrinogen matrix has potent anti-adhesive properties and is capable of repelling cells, even when only 2–3 layers of the fibrinogen molecules have been assembled (32).

One additional mechanism that may contribute to the nonadhesive properties of the fibrinogen matrix is the weaker association between fibrinogen molecules in the superficial layers of the matrix compared with that in the deeper layers. Such reduced stability would allow integrins to pull fibrinogen molecules out of the matrix with forces comparable to or smaller than required for breaking integrin-fibrinogen bonds. Indeed, using a method based on a combination of total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy and atomic force microscopy-based single-cell force spectroscopy, we have recently shown that HEK293 cells expressing leukocyte integrin Mac-1 have the capability to pull fibrinogen molecules from the fibrinogen matrix (38). However, further studies are needed to determine the capacity of platelets and leukocytes to pull fibrinogen molecules from the matrix.

Analyses of adhesion forces developed between uncoated biomaterials and the AFM tip showed a range of 600–1000 pN. These adhesion forces are similar to those detected on glass but in sharp contrast to uncoated mica which displays very low forces (~25 pN) (22). However, even though the adhesion forces determined on uncoated surfaces differ, adsorption of fibrinogen at low concentrations (monolayer) on all surfaces supports high adhesion forces and then, as the concentration of fibrinogen increases, invariably initiates a sharp decline of adhesion forces. At >2 µg/ml fibrinogen, all surfaces, including biomaterials (Fig. 2), are characterized by very low forces. Thus, regardless of the type of the material, fibrinogen modifies surfaces rendering them nonadhesive. A comparable pattern was detected when adhesion forces were measured by SCFS using integrin Mac-1-expressing HEK293 cells (Fig. 5). In particular, SCFS showed high adhesion forces for uncoated biomaterials (~770 pN and 420 pN for PET and PTFE, respectively) which decreased by 6- and 5-fold respectively, when the coating concentration of fibrinogen increased. As in the force spectroscopy experiments, the difference in adhesion forces observed in SCFS appears to be due to differences in the chemical bond composition of the PET and PTFE surfaces (37). At variance with biomaterials, adhesion forces probed by SCFS on uncoated mica were low (~100 pN) and adsorption of low-density fibrinogen first increased them to ~1.7 nN. Nonetheless, adhesion forces dropped to ~200 pN when mica was coated with ≥ 2 µg/ml fibrinogen (32). While the above discussion emphasizes the diversity of adhesion forces detected on uncoated materials and after their modification by low concentrations of fibrinogen, which may tentatively be linked to the chemistry of the surfaces (37) and their ability to induce unfolding of fibrinogen, deposition of high-density fibrinogen consistently creates a nonadhesive surface.

The lack of correlation between the amount of adsorbed fibrinogen and platelet adhesion has been previously reported for a broad range of surface chemistries (9) and when fibrinogen was adsorbed from plasma on hydrophobic surfaces (5–7). The interpretation of this discordance has traditionally been linked to the alterations of fibrinogen conformation and/or availability of integrin-binding sites (4,7,9). However, even though fibrinogen is known to unfold on various surfaces exposing cryptic binding sites for platelets and leukocytes (36,39), the accessibility of these sequences for platelet integrin αIIbβ3 and leukocyte integrin Mac-1 does not depend on the coating concentration of fibrinogen (22,40). On the contrary, the contact of fibrinogen with various surfaces induces unfolding of the αC regions which then participate in the formation of the extensible multilayer (33). The formation of this nonadhesive multilayer, the existence of which has not been discovered until very recently, is a primary mechanism regulating mechanosensing by blood cells of and their adhesion to the fibrinogen-coated surfaces.

Based on the unique pattern of platelet and leukocyte adhesion to fibrinogen-coated surfaces, it is reasonable to suggest that fibrinogen deposition on the surface of vascular grafts should differently impact their adhesive properties immediately after implantation and after graft maturation. Accordingly, as soon as the first molecules of fibrinogen contact and adsorb on the surface, they will apparently create a monolayer, which mediates firm platelet adhesion. As adsorption of fibrinogen continues, the surface of grafts may potentially be coated with the fibrinogen multilayer which is not capable of supporting firm cell adhesion, and from which platelets and leukocytes would be washed away by flow. Therefore, the adhesive capacity of implanted vascular grafts after their initial contact with blood may be strongly affected by the rate of fibrinogen adsorption. It is possible that if fibrinogen is deposited quickly, and consequently the nonadhesive fibrinogen multilayer is formed rapidly, few platelets would be attracted to such surfaces. Furthermore, the surface chemistry that promotes efficient self-assembly of the fibrinogen multilayer may decrease initial thrombogenicity. Speculatively, surfaces pre-coated with the fibrinogen matrix before implantation may be even less adhesive than the naked polymers. In contrast to this idea, which seems counter-intuitive, much of the effort in biomaterials research over the past four decades has been directed toward the development of materials that do not react with platelets and fibrinogen (1). However, even though success in reducing platelet adhesion to virgin biomaterials can be achieved, it will not necessarily lead to the reduced platelet adhesion after implantation since initial contact of the fibrinogen molecules with vascular grafts will inevitably create an adhesive monolayer. In this regard, our data show that although uncoated PET is poorly adhesive for platelets and leukocytes, adsorption of very low concentrations of fibrinogen supports strong cell adhesion (Fig. 3). It is only after the fibrinogen multilayer matrix has been formed (>10 µg/ml) that platelet adhesion is strongly reduced.

Although the formation of the nonadhesive multilayer is a natural progression of fibrinogen adsorption, this process is unlikely to be realized in the circulation. Even before the multilayer is formed, the initial formation of the fibrinogen monolayer, which invariably supports rapid platelet adhesion, should lead to their activation, resulting in thrombin generation and fibrin formation. Indeed, numerous studies demonstrated that very soon after implantation, a thrombotic material consisting of fibrin, platelets and leukocytes is deposited on the inner surface of the prostheses (Reviewed in (41)). While some variability in the extent and timing of thrombus formation has been noted, the reaction itself does not depend on the type of biomaterial and was observed on both implanted PET and ePTFE grafts. During the first few days after implantation, the thrombus is stabilized and over the subsequent weeks to many years, its thickness stays constant. The outermost layer of stabilized thrombi in contact with blood has often been described as loosely packed or compacted fibrin having a smooth, glistening and transparent appearance. The presence of fibrin on the flow surface of vascular grafts has been known for five decades since De Bakey et al described the fibrin lining on Dacron grafts recovered from patients following implant periods up to 7 years (28). Numerous studies subsequently confirmed this finding (28–31,42,43). Furthermore, it has been repeatedly emphasized that the fibrin matrix, especially in the middle regions of grafts, lacks all forms of cellular coverage (41). Discussion of the acellular appearance of the inner fibrin capsule of grafts implanted in humans has traditionally focused on the conspicuous lack of endothelial cells, which signifies the inability to achieve complete healing. Perhaps even a more prominent feature of mature grafts is the almost complete absence of adherent platelets or leukocytes, i.e., the nonthrombogenic nature of the fibrin lining. The lack of endothelial cells and platelets on the surface of fibrin lining may have the same underlying mechanisms; however, the origin of this phenomenon has not been addressed. One reason for the lack of interest in this problem in the field might have been the good overall performance of large-diameter prostheses. In this regard, some studies concluded that the ultimate development of the endothelial lining, a feature of complete healing, is nonessential since vascular grafts remained patent and functional for many years (42,44).

We and other groups have shown that pure fibrin, which is a highly adhesive substrate for platelets and leukocytes, loses its capacity to support cell adhesion in the presence of soluble fibrinogen or after coating of fibrin clots with fibrinogen (19,22,45). The mechanism by which fibrinogen neutralizes the adhesion-promoting capacity of fibrin is evidently the deposition of the nonadhesive fibrinogen multilayer on its surface. Thrombus formation on the surface of vascular grafts immediately after implantation seems to closely recapitulate the events occurring on damaged areas of natural blood vessels: i.e., initial platelet adhesion followed by their activation and platelet aggregation. The formation of the platelet plug is spatially coordinated with the activation of the blood coagulation system leading to thrombin generation and the formation of fibrin which is deposited over the platelet plug. Similar to fibrin lining of vascular grafts, many studies of experimental thrombosis have found no platelets on the surface of thrombus-associated fibrin (21,46). Since thrombi in the circulation are continuously exposed to high (2–3 mg/mL) concentrations of fibrinogen, the nonadhesive fibrinogen matrix appears to assemble on the surface of fibrin developed around stabilized thrombi, thereby preventing platelet adhesion. Indeed, our recent examination of the spatial distribution of fibrin and fibrinogen on the surface of stabilized thrombi generated in flowing blood showed the presence of intact fibrinogen on the surface of the fibrin cap (manuscript submitted). These data imply that the formation of a nonadhesive fibrinogen layer on top of fibrin prevents thrombus propagation and, thus, represents a final step of hemostasis. These findings also suggest that the lining on the surface of mature vascular grafts may, in fact, not be pure fibrin, but a fibrinogen layer which acts as a natural anti-adhesive coat. This would explain the lack of platelets and other cells on the surface of mature vascular grafts. Thus, similar to normal hemostasis, implantation of vascular grafts appears to evoke the normal protective reaction of host to injury. However, in contrast to hemostatic thrombi that occasionally form on the surface of locally damaged endothelium in the circulation and eventually heal, prosthetic vascular grafts are “frozen” in the state of persistent healing for years. At present, the mechanisms that maintain the nonadhesive state of fibrin lining on the surface of vascular grafts for extended periods of time remain to be elucidated.

5. Conclusion

The results of the present study show that adsorption of fibrinogen on the surface of PET and PTFE, the synthetic materials used for manufacturing of contemporary vascular grafts, modifies their adhesive properties in a way described previously for other hard surfaces. In particular, while fibrinogen deposited at very low concentrations creates a substrate highly adhesive for platelets and leukocytes, adsorption of fibrinogen at the increasing concentrations results in the formation of the nonadhesive matrix. The nonadhesive properties of the high density fibrinogen matrix are derived from its multilayer organization and extensibility which, in turn, results in the inability to transduce strong mechanical forces through cellular integrins, a requirement for the firm cell adhesion. Thus, the findings indicate that adsorption of fibrinogen on biomaterials supports the generality of the fibrinogen-dependent anti-adhesive mechanism. The formation of the nonadhesive fibrinogen multilayer, the structure still poorly appreciated in the biomaterials field, may explain previous observations of a poor correlation between the amount of adsorbed fibrinogen and platelet adhesion (6,7,9). Further elucidation of the molecular details of this process should assist in better understanding of hemocompatibility of existing and new biomaterials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the NIH grant HL107539 to T.P.U. and R.R. The authors thank Ms. April Boone, Bard Peripheral Vascular Inc. (Tempe, AZ) for help in obtaining the ePTFE samples.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jordan SW, Caikoff EL. Novel thromboresistant materials. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007;45:104A–115A. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang W, Xue H, Li W, Zhang J, Jiang S. Pursuing "zero" protein adsorption of poly(carboxybetaine) from undiluted blood serum and plasma. Langmuir. 2009;25:11911–11916. doi: 10.1021/la9015788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillai S, Arpanaei A, Meyer R, Birkedal V, Gram L, Besenbacher F, Kingshott P. Preventing protein adsorption from a range of surfaces using an aqueous fish protein extract. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2759–2766. doi: 10.1021/bm900589r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindon JN, McManama G, Kushner L, Merril EW, Salzman EW. Does the conformation of adsorbed fibrinogen dictate platelet interactions with artificial surfaces? Blood. 1986;68:355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai W-B, Grunkemeier JM, Horbett TA. Human plasma fibrinogen adsorption and platelet adhesion to polysterene. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1999;44:130–139. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199902)44:2<130::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai W-B, Grunkemeier JM, Horbett TA. Variations in the ability of adsorbed fibrinogen to mediate platelet adhesion to polysterene-based materials: A multivariable statistical analysis of antibody binding to the platelet binding sites of fibrinogen. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2003;67A:1255–1268. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y, Simonovsky FI, Ratner BD, Horbett TA. The role of adsorbed fibrinogen in platelet adhesion to polyurethane surfaces: A comparison of surfcae hydrophobicity, protein adsorption, monoclonal antibody binding, and platelet adhesion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2005;74A:722–738. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu LC, Siedlecki CA. Atomic force microscopy studies of the initial interactions between fibrinogen and surfaces. Langmuir. 2009;25:3675–3681. doi: 10.1021/la803258h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sivaraman B, Latour RA. The relationship between platelet adhesion on surfaces and the structure versus the amount of adsorbed fibrinogen. Biomaterials. 2010;31:832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szott LM, Horbett TA. Protein interactions with surfaces: cellular responses, complement activation, and newer methods. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2011;15:677–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel M, Arnell RE, Sauvage LR, Wu HD, Shi Q, Wechezak AR, Mungin D, Walker M. Experimental evaluation of ten clinically used arterial prostheses. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1992;6:244–251. doi: 10.1007/BF02000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosselin C, Ren D, Greisler HP. In vivo platelet deposition on polytetrafluoroethylene coated with fibrin glue containing fibroblast growth factor 1 and heparin in a canine model. Amer. J. Surgery. 1995;170:126–130. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80270-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swartz DD, Russel JA, Andreadis ST. Engineering of fibrin-based functional and implantable small-diameter blood vessels. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H1451–H1460. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00479.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa T, Okada K, Takano Y, Hiraishi Y, Okita Y. Autologous fibrin-coated small-caliber vascular prostheses improve antithombogenicity by reducing immunological response. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007;135:1268–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coller BS. Interaction of normal, thrombasthenic, and Bernard-Soulier platelets with immobilized fibrinogen: Defective platelet-fibrinogen interaction in thrombasthenia. Blood. 1980;55:169–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savage B, Ruggeri ZM. Selective recognition of adhesive sites in surface-bound fibrinogen by glycoprotein IIb-IIIa on nonactivated platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:11227–11233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endenberg SC, Hantgan RR, Sixma JJ, de Groot PG, Zwaginga JJ. Platelet adhesion to fibrin(ogen) Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis. 1993;4:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Endenburg SC, Lindeboom-Blokzijl L, Zwaginga JJ, Sixma JJ, de Groot PG. Plasma fibrinogen inhibits platelet adhesion in flowing blood to immobilized fibrinogen. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996;16:633–638. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lishko VK, Burke T, Ugarova TP. Anti-adhesive effect of fibrinogen: A safeguard for thrombus stability. Blood. 2007;109:1541–1549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-022764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jen CJ, Lin JC. Direct observation of platelet adhesion to fibrinogen-and fibrin-coated surfaces. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;261(5 Pt 2):H1457–H1463. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.5.H1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Ryn J, Lorenz M, Merk H, Buchanan M, Eisert WG. Accumulation of radiolabeled platelets and fibrin on the carotid artery of rabbits after angioplasty: effects of heparin and dipyridamole. Thromb. Haemost. 2003;90:1179–1186. doi: 10.1160/TH03-05-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Podolnikova NP, Yermolenko IS, Fuhrmann A, Lishko VK, Magonov S, Bowen B, Enderlein J, Podolnikov A, Ros R, Ugarova TP. Control of integrin aIIbb3 outside-in signaling and platelet adhesion by sensing the physical properties of fibrin(ogen) substrates. Biochemistry. 2010;49:68–77. doi: 10.1021/bi9016022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamlin GW, Rajah SM, Crow MJ, Kester RC. Evaluation of the thrombogenic potential of three types of arterial graft studied in an artificial circulation. Br. J. Surgery. 1978;65:272–276. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800650416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldman M, Norcott HC, Hawker RJ, Hail C, Drolc Z, McCollum CN. Femoropopliteal bypass grafts-an isotope technique in vivo comparison of thrombogenicity. Br. J. Surgery. 1982;69:380–382. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800690708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldman M, Norcott HC, Hawker RJ, Drolc Z, McCollum CN. Platelet accumulation on mature Dacron grafts in man. Br. J. Surgery. 1982;69:S38–S40. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800691314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harker LA, Slichter SJ, Sauvage LR. Platelet consumption by arterial prostheses: The effect of endothelialization and pharmacologic inhibition of platelet function. Ann. Surgery. 1977;186:594–601. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197711000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCollum CN, Kester RC, Rajah SM, Learoyd P, Pepper M. Arterial graft maturation: the duration of thrombotic activity in Dacron aortobifemoral grafts measured by platelet and fibrinogen kinetics. Br. J. Surg. 1981;68:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Bakey ME, Jordan GL, Abbot JP, Halpert B, O'Neal RM. The fate of Dacron vascular grafts. Arch. Surg. 1964;89:757–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szilagyi DE, Smith RF, Elliot JP, Allen HM. Long-term behavior of a Dacron arterial substitute: Clinical, roentgenologic and histologic correlation. Ann. Surg. 1965;162:453–477. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196509000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger K, Sauvage LR, Rao AM, Wood SJ. Healing of arterial prostheses in man: Its incompleteness. Ann. Surg. 1972;175:118–127. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197201000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi Q, Wu M, Onuki Y, Ghali R, Hunter TG, Johansen KH, Sauvage LR. Endothelium on the flow surface of human aortic Dacron vascular grafts. J. Vasc. Surg. 1997;25:736–742. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yermolenko IS, Fuhrmann A, Magonov SN, Lishko VK, Oshkaderov SP, Ros R, Ugarova TP. Origin of nonadhesive properties of fibrinogen matrices probed by force spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2010;26:17269–17277. doi: 10.1021/la101791r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yermolenko IS, Gorkun OV, Fuhrmann A, Podolnikova NP, Lishko VK, Oshkaderov SP, Lord ST, Ros R, Ugarova TP. The assembly of nonadhesive fibrinogen matrices depends on the αC regions of the fibrinogen molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:41979–41990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.410696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yakubenko VP, Lishko VK, Lam SCT, Ugarova TP. A molecular basis for integrin αMβ2 ligand binding promiscuity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:48635–48642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lishko VK, Yakubenko VP, Ugarova TP. The interplay between Integrins αMβ2 and α5β1 during cell migration to fibronectin. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;283:116–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ugarova TP, Budzynski AZ, Shattil SJ, Ruggeri ZM, Ginsberg MH, Plow EF. Conformational changes in fibrinogen elicited by its interaction with platelet membrane glycoprotein GPIIb-IIIa. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:21080–21087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anamelechi CC, Truskey GA, Reichert WM. Mylar™ and Teflon-AF™ as cell culture substrates for studying endothelial cell adhesion. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6887–6896. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christenson W, Yermolenko IS, Plochberger B, Camacho-Alanis F, Ros A, Ugarova TP, Ros R. Combined single cell AFM manipulation and TIRFM for probing the molecular stability of multilayer fibrinogen matrices. Ultramicroscopy. 2014;136:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lishko VK, Kudryk B, Yakubenko VP, Yee VC, Ugarova TP. Regulated unmasking of the cryptic binding site for integrin αMβ2 in the γC-domain of fibrinogen. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12942–12951. doi: 10.1021/bi026324c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moskowitz KA, Kudryk B, Coller BS. Fibrinogen coating density affects the conformation of immobilized fibrinogen: implications for platelet adhesion and spreading. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;79:824–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zilla P, Bezuidenhout D, Human P. Prostethic vascular grafts: Wrong models. wrong questions and no healing. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5009–5027. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart GJ, Essa N, Chang KHY, Reichle FA. A scanning and transmission electron microscope study of the luminal coating on Dacron prostheses in the canine thoracic aorta. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1975;85:208–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guidoin R, Gosselin C, Martin L, Marois M, laroche F, King M, Gunasekera K, Domurado D, Sigot-Luizard MF, Blais P. Polyester prostheses as substitutes in the thoracic aorta of dogs. I. Evaluation of commercial prostheses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1983;17:1049–1077. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820170614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasquinelli G, Freyrie A, Preda T, Curti T, D'Addato M, Laschi R. Healing of prosthetic arterial grafts. Scanning Microscopy. 1990;4:351–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lishko VK, Yermolenko IS, Owaynat H, Ugarova TP. Fibrinogen counteracts the antiadhesive effect of fibrin-bound plasminogen by preventing its activation by adherent U937 monocytic cells. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2012;10:1081–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kinlough-Rathbone RL, Packman MA, Mustard JF. Vessel injury, platelet adherence, and platelet survival. Arteriosclerosis. 1983;3:529–546. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.3.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.